User login

Offer these interventions to help prevent suicide by firearm

Firearms are the most common means of suicide in the United States, accounting for approximately 20,000 adult deaths annually,1 which is approximately two-thirds of the more than 32,000 gun-related fatalities each year in the United States. Of approximately 3,000 American children who are shot to death annually, one-third are suicides.1-4

Firearms are dangerous; it has been documented that even guns obtained for recreation or protection increase the risk of suicide, homicide, or injury.2,3 This problem has become a public health concern.3-8 Because most suicide attempts with firearms are fatal, psychiatrists have an interest in reducing such outcomes.1-8

Risk factors for suicide by firearm

Easy availability of a gun in the home, with ammunition present—especially a gun that is kept loaded and not locked up—is the one of the biggest risk factors for suicide by firearms.4 Unrestricted, quick access allows people who are impulsive little time to reconsider suicide. The risk presented by easy availability is magnified by dangerous concomitant intoxication (see below), distress, and lack of supervision (of children).

Alcohol consumption is associated with suicide. Approximately one-fourth of the people who commit suicide are intoxicated at the time of death.9 Alcohol use, especially binge drinking, is observed in an even larger percentage of suicide attempts than individuals using guns while sober.

Female sex. In recent years, gun use by women has increased, along with firearm-related suicide. Simply having a gun at home greatly increases the suicide rate for women.2-4

People with a history of high impulsivity, impaired judgment, violence, or psychiatric and neurologic disorders places people at greater risk of shooting themselves, especially those with depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, psychosis, or dementia.4

Older age, particularly men who live alone, increases the risk of suicide by firearms, especially in the context of chronic pain or other health problems. Gunfire is the most common means of suicide among geriatric patients of both sexes.8

Lethality. In general, suicide attempts with guns are more likely to be fatal than overdosing, poisoning, or self-mutilation.1,2 Most self-inflicted gunshot wounds result in death, usually on the day of the shooting.1,2

Evidence about these risk factors has led the American Medical Association and other health care groups to encourage physicians—in particular, psychiatric clinicians who focus on suicide prevention—to counsel patients about gun safety.

What can you do to minimize risk?

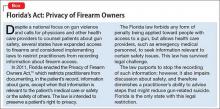

Gun-related inquiry and counsel by psychiatrists can benefit patients and their family.4 Be aware, however, of restrictions on such discussions by health care providers in some states (Box).10

Ask about the presence of firearms in the home. Our advice and our “doctor’s orders” are a means to promote health; suggestions in the context of a supportive physician-patient relationship could result in compliance.3,4 Firearm-focused discussions might be uncomfortable or unpopular but are critical for preventing suicide. Openly discussing such issues with our patients could avoid tragedies.4 Involving family or significant others in these interventions also might be helpful.

Ask about access to and storage of firearms. Simply talking about gun safety is helpful.4 Seeking information about gun usage is especially called for in psychiatric practices that treat patients with suicidal ideation, depression, substance abuse, and cognitive impairment.8 Discuss firearm availability with patients who have a history of substance use, impulsivity, anger, or violence, or who have a brain disorder or neurologic condition. Talking about firearms with patients and educating them about safety is indicated whenever you observe a risk factor for suicide.

Advise safe storage. Aim to have the entire family agree to a safety policy. Guns should be kept unloaded and not stored with ammunition (eg, keep guns in the attic and ammunition in the basement), which might diminish the risk of (1) an impulsive shooting and (2) a planned attempt by giving people time to consider options other than suicide. Firearm safety includes locking ammunition and weapons in a safe and applying trigger locks. Try to get patients and their family to plan for compliance with such recommendations whenever possible.

Guide dialogue and educate patients about handling guns safely. Be sure that patients know that most firearm deaths that happen inside a home are suicide.2-4 Advise patients, and their family, that firearms should not be handled while intoxicated.4 Encourage families to remove gun access from members who are suicidal, depressed, abusing pharmaceuticals or using illicit drugs, and those in distress or with a significant mental or neurologic illness.

In such circumstances, institute a protective plan to prevent shootings. This can be time-limited, or might include removing guns or ammunition from the home or deactivating firing mechanisms, etc. For safety reasons, some families do not keep ammunition in their home.

Additionally, firearms in the hands of children ought to include close monitoring by a responsible, sober adult. Keeping guns in locked storage is especially important for preventing suicide in children. Despite suicide being less frequent among younger people than in adults, taking steps to avoid 1,000 child suicides each year in the United States is a valuable intervention.

Conclusion

Specific inquiry, overt discussion, and face-to-face counseling about gun safety can be a life-saving aspect of psychiatric intervention. With such recommendations and education, psychiatrists can play a productive role in reducing firearm-related suicide.

1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: data and statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Updated December 8, 2015. Accessed April 1, 2016.

2. Narang P, Paladugu A, Manda SR, et al. Do guns provide safety? At what cost? South Med J. 2010;103(2):151-153.

3. Cherlopalle S, Kolikonda MK, Enja M, et al. Guns in America: defense or danger? J Trauma Treat. 2014;3(4):207.

4. Lippmann S. Doctors teaching gun safety. Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. 2015;113(4):112.

5. Cooke BK, Goddard ER, Ginory A, et al. Firearms inquiries in Florida: “medical privacy” or medical neglect? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(3):399-408.

6. Valeras AB. Patient with gun. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):584-585.

7. Butkus R, Weissman A. Internists’ attitude toward prevention of firearm injury. Ann Intern Med. 2015;160(12):821-827.

8. Kapp MB. Geriatric patients, firearms, and physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(6):421-422.

9. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):38-43.

10. Fla Stat §790.338.

Firearms are the most common means of suicide in the United States, accounting for approximately 20,000 adult deaths annually,1 which is approximately two-thirds of the more than 32,000 gun-related fatalities each year in the United States. Of approximately 3,000 American children who are shot to death annually, one-third are suicides.1-4

Firearms are dangerous; it has been documented that even guns obtained for recreation or protection increase the risk of suicide, homicide, or injury.2,3 This problem has become a public health concern.3-8 Because most suicide attempts with firearms are fatal, psychiatrists have an interest in reducing such outcomes.1-8

Risk factors for suicide by firearm

Easy availability of a gun in the home, with ammunition present—especially a gun that is kept loaded and not locked up—is the one of the biggest risk factors for suicide by firearms.4 Unrestricted, quick access allows people who are impulsive little time to reconsider suicide. The risk presented by easy availability is magnified by dangerous concomitant intoxication (see below), distress, and lack of supervision (of children).

Alcohol consumption is associated with suicide. Approximately one-fourth of the people who commit suicide are intoxicated at the time of death.9 Alcohol use, especially binge drinking, is observed in an even larger percentage of suicide attempts than individuals using guns while sober.

Female sex. In recent years, gun use by women has increased, along with firearm-related suicide. Simply having a gun at home greatly increases the suicide rate for women.2-4

People with a history of high impulsivity, impaired judgment, violence, or psychiatric and neurologic disorders places people at greater risk of shooting themselves, especially those with depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, psychosis, or dementia.4

Older age, particularly men who live alone, increases the risk of suicide by firearms, especially in the context of chronic pain or other health problems. Gunfire is the most common means of suicide among geriatric patients of both sexes.8

Lethality. In general, suicide attempts with guns are more likely to be fatal than overdosing, poisoning, or self-mutilation.1,2 Most self-inflicted gunshot wounds result in death, usually on the day of the shooting.1,2

Evidence about these risk factors has led the American Medical Association and other health care groups to encourage physicians—in particular, psychiatric clinicians who focus on suicide prevention—to counsel patients about gun safety.

What can you do to minimize risk?

Gun-related inquiry and counsel by psychiatrists can benefit patients and their family.4 Be aware, however, of restrictions on such discussions by health care providers in some states (Box).10

Ask about the presence of firearms in the home. Our advice and our “doctor’s orders” are a means to promote health; suggestions in the context of a supportive physician-patient relationship could result in compliance.3,4 Firearm-focused discussions might be uncomfortable or unpopular but are critical for preventing suicide. Openly discussing such issues with our patients could avoid tragedies.4 Involving family or significant others in these interventions also might be helpful.

Ask about access to and storage of firearms. Simply talking about gun safety is helpful.4 Seeking information about gun usage is especially called for in psychiatric practices that treat patients with suicidal ideation, depression, substance abuse, and cognitive impairment.8 Discuss firearm availability with patients who have a history of substance use, impulsivity, anger, or violence, or who have a brain disorder or neurologic condition. Talking about firearms with patients and educating them about safety is indicated whenever you observe a risk factor for suicide.

Advise safe storage. Aim to have the entire family agree to a safety policy. Guns should be kept unloaded and not stored with ammunition (eg, keep guns in the attic and ammunition in the basement), which might diminish the risk of (1) an impulsive shooting and (2) a planned attempt by giving people time to consider options other than suicide. Firearm safety includes locking ammunition and weapons in a safe and applying trigger locks. Try to get patients and their family to plan for compliance with such recommendations whenever possible.

Guide dialogue and educate patients about handling guns safely. Be sure that patients know that most firearm deaths that happen inside a home are suicide.2-4 Advise patients, and their family, that firearms should not be handled while intoxicated.4 Encourage families to remove gun access from members who are suicidal, depressed, abusing pharmaceuticals or using illicit drugs, and those in distress or with a significant mental or neurologic illness.

In such circumstances, institute a protective plan to prevent shootings. This can be time-limited, or might include removing guns or ammunition from the home or deactivating firing mechanisms, etc. For safety reasons, some families do not keep ammunition in their home.

Additionally, firearms in the hands of children ought to include close monitoring by a responsible, sober adult. Keeping guns in locked storage is especially important for preventing suicide in children. Despite suicide being less frequent among younger people than in adults, taking steps to avoid 1,000 child suicides each year in the United States is a valuable intervention.

Conclusion

Specific inquiry, overt discussion, and face-to-face counseling about gun safety can be a life-saving aspect of psychiatric intervention. With such recommendations and education, psychiatrists can play a productive role in reducing firearm-related suicide.

Firearms are the most common means of suicide in the United States, accounting for approximately 20,000 adult deaths annually,1 which is approximately two-thirds of the more than 32,000 gun-related fatalities each year in the United States. Of approximately 3,000 American children who are shot to death annually, one-third are suicides.1-4

Firearms are dangerous; it has been documented that even guns obtained for recreation or protection increase the risk of suicide, homicide, or injury.2,3 This problem has become a public health concern.3-8 Because most suicide attempts with firearms are fatal, psychiatrists have an interest in reducing such outcomes.1-8

Risk factors for suicide by firearm

Easy availability of a gun in the home, with ammunition present—especially a gun that is kept loaded and not locked up—is the one of the biggest risk factors for suicide by firearms.4 Unrestricted, quick access allows people who are impulsive little time to reconsider suicide. The risk presented by easy availability is magnified by dangerous concomitant intoxication (see below), distress, and lack of supervision (of children).

Alcohol consumption is associated with suicide. Approximately one-fourth of the people who commit suicide are intoxicated at the time of death.9 Alcohol use, especially binge drinking, is observed in an even larger percentage of suicide attempts than individuals using guns while sober.

Female sex. In recent years, gun use by women has increased, along with firearm-related suicide. Simply having a gun at home greatly increases the suicide rate for women.2-4

People with a history of high impulsivity, impaired judgment, violence, or psychiatric and neurologic disorders places people at greater risk of shooting themselves, especially those with depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, psychosis, or dementia.4

Older age, particularly men who live alone, increases the risk of suicide by firearms, especially in the context of chronic pain or other health problems. Gunfire is the most common means of suicide among geriatric patients of both sexes.8

Lethality. In general, suicide attempts with guns are more likely to be fatal than overdosing, poisoning, or self-mutilation.1,2 Most self-inflicted gunshot wounds result in death, usually on the day of the shooting.1,2

Evidence about these risk factors has led the American Medical Association and other health care groups to encourage physicians—in particular, psychiatric clinicians who focus on suicide prevention—to counsel patients about gun safety.

What can you do to minimize risk?

Gun-related inquiry and counsel by psychiatrists can benefit patients and their family.4 Be aware, however, of restrictions on such discussions by health care providers in some states (Box).10

Ask about the presence of firearms in the home. Our advice and our “doctor’s orders” are a means to promote health; suggestions in the context of a supportive physician-patient relationship could result in compliance.3,4 Firearm-focused discussions might be uncomfortable or unpopular but are critical for preventing suicide. Openly discussing such issues with our patients could avoid tragedies.4 Involving family or significant others in these interventions also might be helpful.

Ask about access to and storage of firearms. Simply talking about gun safety is helpful.4 Seeking information about gun usage is especially called for in psychiatric practices that treat patients with suicidal ideation, depression, substance abuse, and cognitive impairment.8 Discuss firearm availability with patients who have a history of substance use, impulsivity, anger, or violence, or who have a brain disorder or neurologic condition. Talking about firearms with patients and educating them about safety is indicated whenever you observe a risk factor for suicide.

Advise safe storage. Aim to have the entire family agree to a safety policy. Guns should be kept unloaded and not stored with ammunition (eg, keep guns in the attic and ammunition in the basement), which might diminish the risk of (1) an impulsive shooting and (2) a planned attempt by giving people time to consider options other than suicide. Firearm safety includes locking ammunition and weapons in a safe and applying trigger locks. Try to get patients and their family to plan for compliance with such recommendations whenever possible.

Guide dialogue and educate patients about handling guns safely. Be sure that patients know that most firearm deaths that happen inside a home are suicide.2-4 Advise patients, and their family, that firearms should not be handled while intoxicated.4 Encourage families to remove gun access from members who are suicidal, depressed, abusing pharmaceuticals or using illicit drugs, and those in distress or with a significant mental or neurologic illness.

In such circumstances, institute a protective plan to prevent shootings. This can be time-limited, or might include removing guns or ammunition from the home or deactivating firing mechanisms, etc. For safety reasons, some families do not keep ammunition in their home.

Additionally, firearms in the hands of children ought to include close monitoring by a responsible, sober adult. Keeping guns in locked storage is especially important for preventing suicide in children. Despite suicide being less frequent among younger people than in adults, taking steps to avoid 1,000 child suicides each year in the United States is a valuable intervention.

Conclusion

Specific inquiry, overt discussion, and face-to-face counseling about gun safety can be a life-saving aspect of psychiatric intervention. With such recommendations and education, psychiatrists can play a productive role in reducing firearm-related suicide.

1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: data and statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Updated December 8, 2015. Accessed April 1, 2016.

2. Narang P, Paladugu A, Manda SR, et al. Do guns provide safety? At what cost? South Med J. 2010;103(2):151-153.

3. Cherlopalle S, Kolikonda MK, Enja M, et al. Guns in America: defense or danger? J Trauma Treat. 2014;3(4):207.

4. Lippmann S. Doctors teaching gun safety. Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. 2015;113(4):112.

5. Cooke BK, Goddard ER, Ginory A, et al. Firearms inquiries in Florida: “medical privacy” or medical neglect? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(3):399-408.

6. Valeras AB. Patient with gun. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):584-585.

7. Butkus R, Weissman A. Internists’ attitude toward prevention of firearm injury. Ann Intern Med. 2015;160(12):821-827.

8. Kapp MB. Geriatric patients, firearms, and physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(6):421-422.

9. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):38-43.

10. Fla Stat §790.338.

1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: data and statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars. Updated December 8, 2015. Accessed April 1, 2016.

2. Narang P, Paladugu A, Manda SR, et al. Do guns provide safety? At what cost? South Med J. 2010;103(2):151-153.

3. Cherlopalle S, Kolikonda MK, Enja M, et al. Guns in America: defense or danger? J Trauma Treat. 2014;3(4):207.

4. Lippmann S. Doctors teaching gun safety. Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. 2015;113(4):112.

5. Cooke BK, Goddard ER, Ginory A, et al. Firearms inquiries in Florida: “medical privacy” or medical neglect? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(3):399-408.

6. Valeras AB. Patient with gun. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):584-585.

7. Butkus R, Weissman A. Internists’ attitude toward prevention of firearm injury. Ann Intern Med. 2015;160(12):821-827.

8. Kapp MB. Geriatric patients, firearms, and physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(6):421-422.

9. Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):38-43.

10. Fla Stat §790.338.

When ‘eating healthy’ becomes disordered, you can return patients to genuine health

Orthorexia nervosa, from the Greek orthos (straight, proper) and orexia (appetite), is a disorder in which a person demonstrates a pathological obsession not with weight loss but with a “pure” or healthy diet, which can contribute to significant dietary restriction and food-related obsessions. Although the disorder is not a formal diagnosis in DSM 5,1 it is increasingly reported on college campuses and in medical practices, and has been the focus of media attention.

How common is orthorexia?

The precise prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is unknown; some authors have reported estimates as high as 21% of the general population2 and 43.6% of medical students.3 The higher prevalence among medical students might be attributable to the increased focus on factors that can contribute to illnesses (eg, food and diet), and thus underscores the importance of screening for orthorexia symptoms among this population.

How do you identify the disorder?

Orthorexia nervosa was first described by Bratman,4 who observed that a subset of his eating disorder patients were overly obsessed with maintaining an extreme “healthy diet.” Although diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa have not been established, Bratman proposed the following as symptoms indicative of the disorder:

- spending >3 hours a day thinking about a healthy diet

- worrying more about the perceived nutritional quality or “purity” of one’s food than the pleasure of eating it

- feeling guilty about straying from dietary beliefs

- having eating habits that isolate the affected person from others.

Given the focus on this disorder in the media and its presence in medical practice, it is important that you become familiar with the symptoms associated with orthorexia nervosa so you can provide necessary treatment. A patient’s answers to the following questions will aid the savvy clinician in identifying symptoms that suggest orthorexia nervosa5:

- Do you turn to healthy food as a primary source of happiness and meaning, even more so than spirituality?

- Does your diet make you feel superior to other people?

- Does your diet interfere with your personal relationships (family, friends), or with your work?

- Do you use pure foods as a “sword and shield” to ward off anxiety, not just about health problems but about everything that makes you feel insecure?

- Do foods help you feel in control more than really makes sense?

- Do you have to carry your diet to further and further extremes to provide the same “kick”?

- If you stray even minimally from your chosen diet, do you feel a compulsive need to cleanse?

- Has your interest in healthy food expanded past reasonable boundaries to become a kind of brain parasite, so to speak, controlling your life rather than furthering your goals?

No single item is indicative of orthorexia nervosa; however, this list represents a potential clinical picture of how the disorder presents.

Overlap with anorexia nervosa. Although overlap in symptom presentation between these 2 disorders can be significant (eg, diet rigidity can lead to malnutrition, even death), each has important distinguishing features. A low weight status or significant weight loss, or both, is a hallmark characteristic of anorexia nervosa; however, weight loss is not the primary goal in orthorexia nervosa (although extreme dietary restriction in orthorexia could contribute to weight loss). Additionally, a person with anorexia nervosa tends to be preoccupied with weight or shape; a person with orthorexia nervosa is obsessed with food quality and purity. Finally, people with orthorexia have an obsessive preoccupation with health, whereas those with anorexia are more consumed with a fear of fat or weight gain.

Multimodal treatment is indicated

Treating orthorexia typically includes a combination of interventions common to other eating disorders. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary and nutritional counseling, and medical management of any physical sequelae that result from extreme dietary restriction and malnutrition. Refer patients in whom you suspect orthorexia nervosa to a trained therapist and a dietician who have expertise in managing eating disorders.

It is encouraging to note that, with careful diagnosis and appropriate treatment, recovery from orthorexia is possible,6 and patients can achieve an improved quality of life.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Ramacciotti CE, Perrone P, Coli E, et al. Orthorexia nervosa in the general population: a preliminary screening using a self-administered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16(2):e127-e130.

3. Fidan T, Ertekin V, Isikay S, et al. Prevalence of orthorexia among medical students in Erzurum, Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):49-54.

4. Bratman S, Knight D. Health food junkies: orthorexia nervosa: overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. New York, NY: Broadway Books; 2000.

5. Bratman S. What is orthorexia? http://www.orthorexia.com. Published January 23, 2014. Accessed March 3, 2016.

6. Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(6):691-702.

Orthorexia nervosa, from the Greek orthos (straight, proper) and orexia (appetite), is a disorder in which a person demonstrates a pathological obsession not with weight loss but with a “pure” or healthy diet, which can contribute to significant dietary restriction and food-related obsessions. Although the disorder is not a formal diagnosis in DSM 5,1 it is increasingly reported on college campuses and in medical practices, and has been the focus of media attention.

How common is orthorexia?

The precise prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is unknown; some authors have reported estimates as high as 21% of the general population2 and 43.6% of medical students.3 The higher prevalence among medical students might be attributable to the increased focus on factors that can contribute to illnesses (eg, food and diet), and thus underscores the importance of screening for orthorexia symptoms among this population.

How do you identify the disorder?

Orthorexia nervosa was first described by Bratman,4 who observed that a subset of his eating disorder patients were overly obsessed with maintaining an extreme “healthy diet.” Although diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa have not been established, Bratman proposed the following as symptoms indicative of the disorder:

- spending >3 hours a day thinking about a healthy diet

- worrying more about the perceived nutritional quality or “purity” of one’s food than the pleasure of eating it

- feeling guilty about straying from dietary beliefs

- having eating habits that isolate the affected person from others.

Given the focus on this disorder in the media and its presence in medical practice, it is important that you become familiar with the symptoms associated with orthorexia nervosa so you can provide necessary treatment. A patient’s answers to the following questions will aid the savvy clinician in identifying symptoms that suggest orthorexia nervosa5:

- Do you turn to healthy food as a primary source of happiness and meaning, even more so than spirituality?

- Does your diet make you feel superior to other people?

- Does your diet interfere with your personal relationships (family, friends), or with your work?

- Do you use pure foods as a “sword and shield” to ward off anxiety, not just about health problems but about everything that makes you feel insecure?

- Do foods help you feel in control more than really makes sense?

- Do you have to carry your diet to further and further extremes to provide the same “kick”?

- If you stray even minimally from your chosen diet, do you feel a compulsive need to cleanse?

- Has your interest in healthy food expanded past reasonable boundaries to become a kind of brain parasite, so to speak, controlling your life rather than furthering your goals?

No single item is indicative of orthorexia nervosa; however, this list represents a potential clinical picture of how the disorder presents.

Overlap with anorexia nervosa. Although overlap in symptom presentation between these 2 disorders can be significant (eg, diet rigidity can lead to malnutrition, even death), each has important distinguishing features. A low weight status or significant weight loss, or both, is a hallmark characteristic of anorexia nervosa; however, weight loss is not the primary goal in orthorexia nervosa (although extreme dietary restriction in orthorexia could contribute to weight loss). Additionally, a person with anorexia nervosa tends to be preoccupied with weight or shape; a person with orthorexia nervosa is obsessed with food quality and purity. Finally, people with orthorexia have an obsessive preoccupation with health, whereas those with anorexia are more consumed with a fear of fat or weight gain.

Multimodal treatment is indicated

Treating orthorexia typically includes a combination of interventions common to other eating disorders. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary and nutritional counseling, and medical management of any physical sequelae that result from extreme dietary restriction and malnutrition. Refer patients in whom you suspect orthorexia nervosa to a trained therapist and a dietician who have expertise in managing eating disorders.

It is encouraging to note that, with careful diagnosis and appropriate treatment, recovery from orthorexia is possible,6 and patients can achieve an improved quality of life.

Orthorexia nervosa, from the Greek orthos (straight, proper) and orexia (appetite), is a disorder in which a person demonstrates a pathological obsession not with weight loss but with a “pure” or healthy diet, which can contribute to significant dietary restriction and food-related obsessions. Although the disorder is not a formal diagnosis in DSM 5,1 it is increasingly reported on college campuses and in medical practices, and has been the focus of media attention.

How common is orthorexia?

The precise prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is unknown; some authors have reported estimates as high as 21% of the general population2 and 43.6% of medical students.3 The higher prevalence among medical students might be attributable to the increased focus on factors that can contribute to illnesses (eg, food and diet), and thus underscores the importance of screening for orthorexia symptoms among this population.

How do you identify the disorder?

Orthorexia nervosa was first described by Bratman,4 who observed that a subset of his eating disorder patients were overly obsessed with maintaining an extreme “healthy diet.” Although diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa have not been established, Bratman proposed the following as symptoms indicative of the disorder:

- spending >3 hours a day thinking about a healthy diet

- worrying more about the perceived nutritional quality or “purity” of one’s food than the pleasure of eating it

- feeling guilty about straying from dietary beliefs

- having eating habits that isolate the affected person from others.

Given the focus on this disorder in the media and its presence in medical practice, it is important that you become familiar with the symptoms associated with orthorexia nervosa so you can provide necessary treatment. A patient’s answers to the following questions will aid the savvy clinician in identifying symptoms that suggest orthorexia nervosa5:

- Do you turn to healthy food as a primary source of happiness and meaning, even more so than spirituality?

- Does your diet make you feel superior to other people?

- Does your diet interfere with your personal relationships (family, friends), or with your work?

- Do you use pure foods as a “sword and shield” to ward off anxiety, not just about health problems but about everything that makes you feel insecure?

- Do foods help you feel in control more than really makes sense?

- Do you have to carry your diet to further and further extremes to provide the same “kick”?

- If you stray even minimally from your chosen diet, do you feel a compulsive need to cleanse?

- Has your interest in healthy food expanded past reasonable boundaries to become a kind of brain parasite, so to speak, controlling your life rather than furthering your goals?

No single item is indicative of orthorexia nervosa; however, this list represents a potential clinical picture of how the disorder presents.

Overlap with anorexia nervosa. Although overlap in symptom presentation between these 2 disorders can be significant (eg, diet rigidity can lead to malnutrition, even death), each has important distinguishing features. A low weight status or significant weight loss, or both, is a hallmark characteristic of anorexia nervosa; however, weight loss is not the primary goal in orthorexia nervosa (although extreme dietary restriction in orthorexia could contribute to weight loss). Additionally, a person with anorexia nervosa tends to be preoccupied with weight or shape; a person with orthorexia nervosa is obsessed with food quality and purity. Finally, people with orthorexia have an obsessive preoccupation with health, whereas those with anorexia are more consumed with a fear of fat or weight gain.

Multimodal treatment is indicated

Treating orthorexia typically includes a combination of interventions common to other eating disorders. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, dietary and nutritional counseling, and medical management of any physical sequelae that result from extreme dietary restriction and malnutrition. Refer patients in whom you suspect orthorexia nervosa to a trained therapist and a dietician who have expertise in managing eating disorders.

It is encouraging to note that, with careful diagnosis and appropriate treatment, recovery from orthorexia is possible,6 and patients can achieve an improved quality of life.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Ramacciotti CE, Perrone P, Coli E, et al. Orthorexia nervosa in the general population: a preliminary screening using a self-administered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16(2):e127-e130.

3. Fidan T, Ertekin V, Isikay S, et al. Prevalence of orthorexia among medical students in Erzurum, Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):49-54.

4. Bratman S, Knight D. Health food junkies: orthorexia nervosa: overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. New York, NY: Broadway Books; 2000.

5. Bratman S. What is orthorexia? http://www.orthorexia.com. Published January 23, 2014. Accessed March 3, 2016.

6. Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(6):691-702.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Ramacciotti CE, Perrone P, Coli E, et al. Orthorexia nervosa in the general population: a preliminary screening using a self-administered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord. 2011;16(2):e127-e130.

3. Fidan T, Ertekin V, Isikay S, et al. Prevalence of orthorexia among medical students in Erzurum, Turkey. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):49-54.

4. Bratman S, Knight D. Health food junkies: orthorexia nervosa: overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. New York, NY: Broadway Books; 2000.

5. Bratman S. What is orthorexia? http://www.orthorexia.com. Published January 23, 2014. Accessed March 3, 2016.

6. Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(6):691-702.

Be an activist to prevent edentulism among the mentally ill

Poor dental hygiene is a serious and prevalent problem among people with mental illness or cognitive impairment: Dental caries and periodontal disease are 3.4 times more common among the mentally ill than among the general population.1 Little has been published on the causes and prevention of these diseases among the mentally ill, however. Interprofessional education provides the opportunity to reinforce the connection between oral health and systemic health.

Untreated dental disease can result in edentulism (partial or complete tooth loss). Often, this condition leads to embarrassment, poor self-image, and social isolation—all of which can exacerbate the psychotic state and its symptoms. Working with your patient to improve oral health can, in turn, lead to better mental and physical health.

CASE REPORT

Edentulism in a man with schizophrenia

A 34-year-old man, given a diagnosis of schizophrenia at age 17, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for bizarre behavior. The next day, 4 maxillary and incisor teeth fall out suddenly while he is brushing his teeth. The patient is brought to emergency dental services.

Factors contributing to his tooth loss include:

- schizophrenia

- neglected oral hygiene

- adverse effects of antipsychotic medication

- lack of advice on the importance of oral hygiene

- failure to recognize signs of a dental problem.

What else can lead to edentulism?

Breakdown of the periodontal attachment2 also can be caused by disinterest in oral hygiene practices; craving of, and preference for, carbohydrates because of reduced central serotonin activity3,4; and xerostomia.

Xerostomia, or dry mouth, caused by psychotropic agents and an altered immune response, facilitates growth of pathogenic bacteria and can lead to several dental diseases (Table). These conditions are exacerbated by consumption of chewing gum, sweets, and sugary drinks in response to constantly feeling thirsty from xerostomia. Advise patients to take frequent sips of fluid or let ice cubes melt in their mouth.

Bruxism. Patients taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or an atypical antipsychotic can develop a movement disorder (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms or tardive dyskinesia) that includes clenching, grinding of the teeth (bruxism), or both, which can worsen their periodontal condition.

Lack of skills, physical dexterity, and motivation to maintain good oral hygiene are common among people with mental illness. Most patients visit a dentist only when they experience a serious oral problem or an emergency (ie, trauma). Many dentists treat psychiatric patients by extracting the tooth that is causing the pain, instead of pursuing complex tooth preservation or restoration techniques because of (1) the extent of the disease, (2) lack of knowledge related to psychiatric illnesses, and (3) frequent and timely follow-ups.5

Providing education about oral health to patients, implementing preventive steps, and educating other medical specialities about the link between oral health and systemic health can help to reduce the burden of dental problems among mentally ill patients.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products

1. Persson K, Axtelius B, Söderfeldt B, et al. Oral health-related quality of life and dental status in an outpatient psychiatric population: a multivariate approach. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2010;19(1):62-70.

2. Lalloo R, Kisely S, Amarasinghe H, et al. Oral health of patients on psychotropic medications: a study of outpatients in Queensland. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):338-342.

3. O’Neil A, Berk M, Venugopal K, et al. The association between poor dental health and depression: findings from a large-scale, population-based study (the NHANES study). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):266-270.

4. Kisely S, Quek LH, Paris J, et al. Advanced dental disease in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(3):187-193.

5. Arnaiz A, Zumárraga M, Díez-Altuna I, et al. Oral health and the symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(1):24-28.

Poor dental hygiene is a serious and prevalent problem among people with mental illness or cognitive impairment: Dental caries and periodontal disease are 3.4 times more common among the mentally ill than among the general population.1 Little has been published on the causes and prevention of these diseases among the mentally ill, however. Interprofessional education provides the opportunity to reinforce the connection between oral health and systemic health.

Untreated dental disease can result in edentulism (partial or complete tooth loss). Often, this condition leads to embarrassment, poor self-image, and social isolation—all of which can exacerbate the psychotic state and its symptoms. Working with your patient to improve oral health can, in turn, lead to better mental and physical health.

CASE REPORT

Edentulism in a man with schizophrenia

A 34-year-old man, given a diagnosis of schizophrenia at age 17, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for bizarre behavior. The next day, 4 maxillary and incisor teeth fall out suddenly while he is brushing his teeth. The patient is brought to emergency dental services.

Factors contributing to his tooth loss include:

- schizophrenia

- neglected oral hygiene

- adverse effects of antipsychotic medication

- lack of advice on the importance of oral hygiene

- failure to recognize signs of a dental problem.

What else can lead to edentulism?

Breakdown of the periodontal attachment2 also can be caused by disinterest in oral hygiene practices; craving of, and preference for, carbohydrates because of reduced central serotonin activity3,4; and xerostomia.

Xerostomia, or dry mouth, caused by psychotropic agents and an altered immune response, facilitates growth of pathogenic bacteria and can lead to several dental diseases (Table). These conditions are exacerbated by consumption of chewing gum, sweets, and sugary drinks in response to constantly feeling thirsty from xerostomia. Advise patients to take frequent sips of fluid or let ice cubes melt in their mouth.

Bruxism. Patients taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or an atypical antipsychotic can develop a movement disorder (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms or tardive dyskinesia) that includes clenching, grinding of the teeth (bruxism), or both, which can worsen their periodontal condition.

Lack of skills, physical dexterity, and motivation to maintain good oral hygiene are common among people with mental illness. Most patients visit a dentist only when they experience a serious oral problem or an emergency (ie, trauma). Many dentists treat psychiatric patients by extracting the tooth that is causing the pain, instead of pursuing complex tooth preservation or restoration techniques because of (1) the extent of the disease, (2) lack of knowledge related to psychiatric illnesses, and (3) frequent and timely follow-ups.5

Providing education about oral health to patients, implementing preventive steps, and educating other medical specialities about the link between oral health and systemic health can help to reduce the burden of dental problems among mentally ill patients.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products

Poor dental hygiene is a serious and prevalent problem among people with mental illness or cognitive impairment: Dental caries and periodontal disease are 3.4 times more common among the mentally ill than among the general population.1 Little has been published on the causes and prevention of these diseases among the mentally ill, however. Interprofessional education provides the opportunity to reinforce the connection between oral health and systemic health.

Untreated dental disease can result in edentulism (partial or complete tooth loss). Often, this condition leads to embarrassment, poor self-image, and social isolation—all of which can exacerbate the psychotic state and its symptoms. Working with your patient to improve oral health can, in turn, lead to better mental and physical health.

CASE REPORT

Edentulism in a man with schizophrenia

A 34-year-old man, given a diagnosis of schizophrenia at age 17, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit for bizarre behavior. The next day, 4 maxillary and incisor teeth fall out suddenly while he is brushing his teeth. The patient is brought to emergency dental services.

Factors contributing to his tooth loss include:

- schizophrenia

- neglected oral hygiene

- adverse effects of antipsychotic medication

- lack of advice on the importance of oral hygiene

- failure to recognize signs of a dental problem.

What else can lead to edentulism?

Breakdown of the periodontal attachment2 also can be caused by disinterest in oral hygiene practices; craving of, and preference for, carbohydrates because of reduced central serotonin activity3,4; and xerostomia.

Xerostomia, or dry mouth, caused by psychotropic agents and an altered immune response, facilitates growth of pathogenic bacteria and can lead to several dental diseases (Table). These conditions are exacerbated by consumption of chewing gum, sweets, and sugary drinks in response to constantly feeling thirsty from xerostomia. Advise patients to take frequent sips of fluid or let ice cubes melt in their mouth.

Bruxism. Patients taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or an atypical antipsychotic can develop a movement disorder (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms or tardive dyskinesia) that includes clenching, grinding of the teeth (bruxism), or both, which can worsen their periodontal condition.

Lack of skills, physical dexterity, and motivation to maintain good oral hygiene are common among people with mental illness. Most patients visit a dentist only when they experience a serious oral problem or an emergency (ie, trauma). Many dentists treat psychiatric patients by extracting the tooth that is causing the pain, instead of pursuing complex tooth preservation or restoration techniques because of (1) the extent of the disease, (2) lack of knowledge related to psychiatric illnesses, and (3) frequent and timely follow-ups.5

Providing education about oral health to patients, implementing preventive steps, and educating other medical specialities about the link between oral health and systemic health can help to reduce the burden of dental problems among mentally ill patients.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products

1. Persson K, Axtelius B, Söderfeldt B, et al. Oral health-related quality of life and dental status in an outpatient psychiatric population: a multivariate approach. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2010;19(1):62-70.

2. Lalloo R, Kisely S, Amarasinghe H, et al. Oral health of patients on psychotropic medications: a study of outpatients in Queensland. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):338-342.

3. O’Neil A, Berk M, Venugopal K, et al. The association between poor dental health and depression: findings from a large-scale, population-based study (the NHANES study). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):266-270.

4. Kisely S, Quek LH, Paris J, et al. Advanced dental disease in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(3):187-193.

5. Arnaiz A, Zumárraga M, Díez-Altuna I, et al. Oral health and the symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(1):24-28.

1. Persson K, Axtelius B, Söderfeldt B, et al. Oral health-related quality of life and dental status in an outpatient psychiatric population: a multivariate approach. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2010;19(1):62-70.

2. Lalloo R, Kisely S, Amarasinghe H, et al. Oral health of patients on psychotropic medications: a study of outpatients in Queensland. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):338-342.

3. O’Neil A, Berk M, Venugopal K, et al. The association between poor dental health and depression: findings from a large-scale, population-based study (the NHANES study). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):266-270.

4. Kisely S, Quek LH, Paris J, et al. Advanced dental disease in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(3):187-193.

5. Arnaiz A, Zumárraga M, Díez-Altuna I, et al. Oral health and the symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(1):24-28.

How to pick the proper legal structure for your practice

Picking your practice’s legal structure is far less exciting than choosing which couch to furnish your office with, but the impact of your choice will last far longer than any office furniture. With effects on your liability, finances, and time, choosing the right arrangement is one of the most important business decisions you will make.

Choose a business structure

Solo practice? If you are in solo private practice, you should establish sole proprietorship to, at the least, reduce identity theft. Because insurance companies and government agencies will need your taxpayer identification number (TIN) for you to do business (and unless you fancy giving out your Social Security number freely), forming a sole proprietorship will grant you a business-unique TIN that you can give out. Establishing sole proprietorship is easy on the Internal Revenue Service Web site.

It also is advisable for you to open a business bank account just for your practice, for bookkeeping and auditing purposes.

Also, consider incorporating. You don’t have to have employees or partners to incorporate, and there are substantial benefits to doing so that should be considered.

Group practice? For a group practice, a fundamental rule is to not form a general partnership, because it exposes each member of the group to the liability and debts of the others. Instead, consider picking a limited liability structure or incorporating.

Incorporating. Every state recognizes corporations, although many require physicians to form “professional corporations” (PCs). There are 2 main types of corporations: “C” and “S.” A practice might elect to become an S corporation because it requires less paperwork—but it also means fewer tax benefits and profit or losses are passed through to your individual tax return. C corporations are taxed at corporate tax rates, but employees—including you, as owner—are eligible for more benefits, such as pre-tax commuter and parking reimbursement, flexible spending accounts for dependent care and health care, and pre-tax insurance premiums, to name a few.

Limited liability structure. State laws vary on which kind of limited liability structures are allowed but, typically, the options include forming a Limited Liability Company (LLC), Professional Limited Liability Company (PLLC), or Limited Liability Partnership (LLP). In general, they provide similar liability protection as corporations, and their tax treatment is similar to either a “C” or “S” corporation, depending on state law or what tax structure its members elect. However, they may offer less paperwork and compliance requirements than corporations.

To incorporate or not?

The pros. Decide if it’s worth the time and effort to become a PC:

- Being a PC will not reduce your tax rate (that went away years ago) and cannot protect you from professional malpractice (referred to as “piercing the corporate veil”), but it will protect personal assets from risk of seizure if you incur a non-professional liability, such as for a patient slipping on a banana peel in the waiting room, or an employee lawsuit.

- If you operate more than 1 type of business, a PC may be useful to protect one business from the liability of the other. Or, if you are in a group practice comprising solo practitioners—not employees of a clinic—being a PC could shield you from the liability of your group or any of its members.

- If you have full-time employees (whether they are a family member or not), then you are all eligible for group health insurance, which is typically more affordable than if you have to procure your own policy.

The cons. Consider the downsides to being a corporation:

- It takes paperwork to set up a corporation, for which you typically need to engage a lawyer to complete and file.

- Your corporation might be required to pay a minimum state fee (in California, for example, the fee is $800 annually), and additional tax if you don’t “zero out” your profit and loss by the end of the year (ie, completely distribute all profits through payroll costs or business expenses).

- A corporation must keep corporate documents, although there are templates that one can follow, such as for board resolutions or keeping minutes of meetings.

- Your accountant will charge you more annually for any additional tax paperwork.

Crunch the numbers

Choosing to establish sole proprietorship or a “deeper” legal structure must be thought through wisely. Calculate the cost and benefit to your practice, and consider your risk tolerance for liability.

Once you make a decision, go get that couch!

Picking your practice’s legal structure is far less exciting than choosing which couch to furnish your office with, but the impact of your choice will last far longer than any office furniture. With effects on your liability, finances, and time, choosing the right arrangement is one of the most important business decisions you will make.

Choose a business structure

Solo practice? If you are in solo private practice, you should establish sole proprietorship to, at the least, reduce identity theft. Because insurance companies and government agencies will need your taxpayer identification number (TIN) for you to do business (and unless you fancy giving out your Social Security number freely), forming a sole proprietorship will grant you a business-unique TIN that you can give out. Establishing sole proprietorship is easy on the Internal Revenue Service Web site.

It also is advisable for you to open a business bank account just for your practice, for bookkeeping and auditing purposes.

Also, consider incorporating. You don’t have to have employees or partners to incorporate, and there are substantial benefits to doing so that should be considered.

Group practice? For a group practice, a fundamental rule is to not form a general partnership, because it exposes each member of the group to the liability and debts of the others. Instead, consider picking a limited liability structure or incorporating.

Incorporating. Every state recognizes corporations, although many require physicians to form “professional corporations” (PCs). There are 2 main types of corporations: “C” and “S.” A practice might elect to become an S corporation because it requires less paperwork—but it also means fewer tax benefits and profit or losses are passed through to your individual tax return. C corporations are taxed at corporate tax rates, but employees—including you, as owner—are eligible for more benefits, such as pre-tax commuter and parking reimbursement, flexible spending accounts for dependent care and health care, and pre-tax insurance premiums, to name a few.

Limited liability structure. State laws vary on which kind of limited liability structures are allowed but, typically, the options include forming a Limited Liability Company (LLC), Professional Limited Liability Company (PLLC), or Limited Liability Partnership (LLP). In general, they provide similar liability protection as corporations, and their tax treatment is similar to either a “C” or “S” corporation, depending on state law or what tax structure its members elect. However, they may offer less paperwork and compliance requirements than corporations.

To incorporate or not?

The pros. Decide if it’s worth the time and effort to become a PC:

- Being a PC will not reduce your tax rate (that went away years ago) and cannot protect you from professional malpractice (referred to as “piercing the corporate veil”), but it will protect personal assets from risk of seizure if you incur a non-professional liability, such as for a patient slipping on a banana peel in the waiting room, or an employee lawsuit.

- If you operate more than 1 type of business, a PC may be useful to protect one business from the liability of the other. Or, if you are in a group practice comprising solo practitioners—not employees of a clinic—being a PC could shield you from the liability of your group or any of its members.

- If you have full-time employees (whether they are a family member or not), then you are all eligible for group health insurance, which is typically more affordable than if you have to procure your own policy.

The cons. Consider the downsides to being a corporation:

- It takes paperwork to set up a corporation, for which you typically need to engage a lawyer to complete and file.

- Your corporation might be required to pay a minimum state fee (in California, for example, the fee is $800 annually), and additional tax if you don’t “zero out” your profit and loss by the end of the year (ie, completely distribute all profits through payroll costs or business expenses).

- A corporation must keep corporate documents, although there are templates that one can follow, such as for board resolutions or keeping minutes of meetings.

- Your accountant will charge you more annually for any additional tax paperwork.

Crunch the numbers

Choosing to establish sole proprietorship or a “deeper” legal structure must be thought through wisely. Calculate the cost and benefit to your practice, and consider your risk tolerance for liability.

Once you make a decision, go get that couch!

Picking your practice’s legal structure is far less exciting than choosing which couch to furnish your office with, but the impact of your choice will last far longer than any office furniture. With effects on your liability, finances, and time, choosing the right arrangement is one of the most important business decisions you will make.

Choose a business structure

Solo practice? If you are in solo private practice, you should establish sole proprietorship to, at the least, reduce identity theft. Because insurance companies and government agencies will need your taxpayer identification number (TIN) for you to do business (and unless you fancy giving out your Social Security number freely), forming a sole proprietorship will grant you a business-unique TIN that you can give out. Establishing sole proprietorship is easy on the Internal Revenue Service Web site.

It also is advisable for you to open a business bank account just for your practice, for bookkeeping and auditing purposes.

Also, consider incorporating. You don’t have to have employees or partners to incorporate, and there are substantial benefits to doing so that should be considered.

Group practice? For a group practice, a fundamental rule is to not form a general partnership, because it exposes each member of the group to the liability and debts of the others. Instead, consider picking a limited liability structure or incorporating.

Incorporating. Every state recognizes corporations, although many require physicians to form “professional corporations” (PCs). There are 2 main types of corporations: “C” and “S.” A practice might elect to become an S corporation because it requires less paperwork—but it also means fewer tax benefits and profit or losses are passed through to your individual tax return. C corporations are taxed at corporate tax rates, but employees—including you, as owner—are eligible for more benefits, such as pre-tax commuter and parking reimbursement, flexible spending accounts for dependent care and health care, and pre-tax insurance premiums, to name a few.

Limited liability structure. State laws vary on which kind of limited liability structures are allowed but, typically, the options include forming a Limited Liability Company (LLC), Professional Limited Liability Company (PLLC), or Limited Liability Partnership (LLP). In general, they provide similar liability protection as corporations, and their tax treatment is similar to either a “C” or “S” corporation, depending on state law or what tax structure its members elect. However, they may offer less paperwork and compliance requirements than corporations.

To incorporate or not?

The pros. Decide if it’s worth the time and effort to become a PC:

- Being a PC will not reduce your tax rate (that went away years ago) and cannot protect you from professional malpractice (referred to as “piercing the corporate veil”), but it will protect personal assets from risk of seizure if you incur a non-professional liability, such as for a patient slipping on a banana peel in the waiting room, or an employee lawsuit.

- If you operate more than 1 type of business, a PC may be useful to protect one business from the liability of the other. Or, if you are in a group practice comprising solo practitioners—not employees of a clinic—being a PC could shield you from the liability of your group or any of its members.

- If you have full-time employees (whether they are a family member or not), then you are all eligible for group health insurance, which is typically more affordable than if you have to procure your own policy.

The cons. Consider the downsides to being a corporation:

- It takes paperwork to set up a corporation, for which you typically need to engage a lawyer to complete and file.

- Your corporation might be required to pay a minimum state fee (in California, for example, the fee is $800 annually), and additional tax if you don’t “zero out” your profit and loss by the end of the year (ie, completely distribute all profits through payroll costs or business expenses).

- A corporation must keep corporate documents, although there are templates that one can follow, such as for board resolutions or keeping minutes of meetings.

- Your accountant will charge you more annually for any additional tax paperwork.

Crunch the numbers

Choosing to establish sole proprietorship or a “deeper” legal structure must be thought through wisely. Calculate the cost and benefit to your practice, and consider your risk tolerance for liability.

Once you make a decision, go get that couch!

You can help victims of hazing recover from psychological and physical harm

Initiation has been a part of the tradition of many sororities, fraternities, sports teams, and other organizations to screen and evaluate potential members. Initiation activities can range from humorous, such as pulling pranks on others, to more serious, such as being able to recite the organization’s rules and creed. It is used in the hopes of increasing a new member’s commitment to the group, with the goal of creating group cohesion.

Hazing is not initiation

Hazing is the use of ritualized physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in the guise of initiation. Hazing activities do not help identify the qualities that a person needs for group membership, and can lead to severe physical and psychological harm. Many hazing rituals are done behind closed doors, some with a vow of secrecy.

Studies indicate that 47% of students have been hazed before college, and that 3 of every 5 college students have been subjected to hazing.1 Military and sports teams also have a high rate of hazing; 40% of athletes report that a coach or advisor knew about the hazing.2

Dangers of hazing

Victims of hazing might be brought to the emergency room with severe injury, including broken bones, burns, alcohol intoxication–related injury, chest trauma, multi-organ system failure, sexual trauma, and other medical emergencies, or could die from injuries sustained during hazing activities.

In the 44 states where hazing is illegal, hazing participants could be held be civilly and criminally liable for their actions. Hazing victims may be required to commit crimes, ranging from destruction of property to kidnapping. One-half of all hazing activities involve the use of alcohol,2 and 82% of hazing-related deaths involve alcohol.1

What is your role in treating hazing victims?

You might be called on to treat the psychological symptoms of hazing, including:

- depression

- anxiety

- acute stress syndrome

- alcohol- and drug-related delirium

- posttraumatic stress syndrome.

In addition, you might find yourself needing to:

Arrange for medical care immediately if the patient has a medical problem or an injury.

Contact a victim advocacy programif the victim has made allegations about, or there is evidence of, sexual assault, rape, other sexual injury, or physical or psychological violence.

Notify appropriate law enforcement personnel.

Notify the leadership of the organization (eg, team, school, club) within which the hazing occurred.

Perform a psychiatric assessment and provide treatment for the victim. Some symptoms seen in victims of hazing include sleep disturbance and insomnia, poor grades, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, feelings of low self-esteem and self-worth, trust issues, and symptoms commonly seen in patients with posttraumatic stress syndrome. Symptoms sometimes appear immediately after a hazing event; other times, they develop weeks later. Supportive counseling, stabilization, and advocacy are the immediate goals.

Provide education and treatment for the perpetrator. Unlike bullying, most hazing is not instituted to harm the victim but is seen as a tradition and ritual to increase commitment and bonding. The perpetrator might feel surprise and guilt as to the harm that was done to the victim. Observers of hazing rituals might be traumatized by viewing participants humiliated or abused, and both observers and perpetrators as participants may face legal consequences. Counseling and group debriefing provide education and help them cope with these issues.

Act as a consultant to schools, teams, and other organizations to ensure that group cohesion and team building is obtained in a way that benefits the group and does not harm a member or the organization.

Psychiatrists can provide literature and information especially to adolescent and young adult patients who are at highest risk of hazing. Handouts, informational brochures and posters and be placed in the waiting areas for patient to view. These can be found online (such as www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/safety/and-hazing.pdf) or obtained from local colleges and school systems.

1. Allan EJ, Madden M. Hazing in view: students at risk. http://www.stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/hazing_in_view_web1.pdf. Published March 11, 2008. Accessed May 18, 2015.

2. McBride HC. Parents beware: hazing poses significant danger to new college students. CRC Health. http://www.crchealth.com/treatment/treatment-for-teens/alcohol-addiction/hazing. Accessed May 18, 2015.

Initiation has been a part of the tradition of many sororities, fraternities, sports teams, and other organizations to screen and evaluate potential members. Initiation activities can range from humorous, such as pulling pranks on others, to more serious, such as being able to recite the organization’s rules and creed. It is used in the hopes of increasing a new member’s commitment to the group, with the goal of creating group cohesion.

Hazing is not initiation

Hazing is the use of ritualized physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in the guise of initiation. Hazing activities do not help identify the qualities that a person needs for group membership, and can lead to severe physical and psychological harm. Many hazing rituals are done behind closed doors, some with a vow of secrecy.

Studies indicate that 47% of students have been hazed before college, and that 3 of every 5 college students have been subjected to hazing.1 Military and sports teams also have a high rate of hazing; 40% of athletes report that a coach or advisor knew about the hazing.2

Dangers of hazing

Victims of hazing might be brought to the emergency room with severe injury, including broken bones, burns, alcohol intoxication–related injury, chest trauma, multi-organ system failure, sexual trauma, and other medical emergencies, or could die from injuries sustained during hazing activities.

In the 44 states where hazing is illegal, hazing participants could be held be civilly and criminally liable for their actions. Hazing victims may be required to commit crimes, ranging from destruction of property to kidnapping. One-half of all hazing activities involve the use of alcohol,2 and 82% of hazing-related deaths involve alcohol.1

What is your role in treating hazing victims?

You might be called on to treat the psychological symptoms of hazing, including:

- depression

- anxiety

- acute stress syndrome

- alcohol- and drug-related delirium

- posttraumatic stress syndrome.

In addition, you might find yourself needing to:

Arrange for medical care immediately if the patient has a medical problem or an injury.

Contact a victim advocacy programif the victim has made allegations about, or there is evidence of, sexual assault, rape, other sexual injury, or physical or psychological violence.

Notify appropriate law enforcement personnel.

Notify the leadership of the organization (eg, team, school, club) within which the hazing occurred.

Perform a psychiatric assessment and provide treatment for the victim. Some symptoms seen in victims of hazing include sleep disturbance and insomnia, poor grades, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, feelings of low self-esteem and self-worth, trust issues, and symptoms commonly seen in patients with posttraumatic stress syndrome. Symptoms sometimes appear immediately after a hazing event; other times, they develop weeks later. Supportive counseling, stabilization, and advocacy are the immediate goals.

Provide education and treatment for the perpetrator. Unlike bullying, most hazing is not instituted to harm the victim but is seen as a tradition and ritual to increase commitment and bonding. The perpetrator might feel surprise and guilt as to the harm that was done to the victim. Observers of hazing rituals might be traumatized by viewing participants humiliated or abused, and both observers and perpetrators as participants may face legal consequences. Counseling and group debriefing provide education and help them cope with these issues.

Act as a consultant to schools, teams, and other organizations to ensure that group cohesion and team building is obtained in a way that benefits the group and does not harm a member or the organization.

Psychiatrists can provide literature and information especially to adolescent and young adult patients who are at highest risk of hazing. Handouts, informational brochures and posters and be placed in the waiting areas for patient to view. These can be found online (such as www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/safety/and-hazing.pdf) or obtained from local colleges and school systems.

Initiation has been a part of the tradition of many sororities, fraternities, sports teams, and other organizations to screen and evaluate potential members. Initiation activities can range from humorous, such as pulling pranks on others, to more serious, such as being able to recite the organization’s rules and creed. It is used in the hopes of increasing a new member’s commitment to the group, with the goal of creating group cohesion.

Hazing is not initiation

Hazing is the use of ritualized physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in the guise of initiation. Hazing activities do not help identify the qualities that a person needs for group membership, and can lead to severe physical and psychological harm. Many hazing rituals are done behind closed doors, some with a vow of secrecy.

Studies indicate that 47% of students have been hazed before college, and that 3 of every 5 college students have been subjected to hazing.1 Military and sports teams also have a high rate of hazing; 40% of athletes report that a coach or advisor knew about the hazing.2

Dangers of hazing

Victims of hazing might be brought to the emergency room with severe injury, including broken bones, burns, alcohol intoxication–related injury, chest trauma, multi-organ system failure, sexual trauma, and other medical emergencies, or could die from injuries sustained during hazing activities.

In the 44 states where hazing is illegal, hazing participants could be held be civilly and criminally liable for their actions. Hazing victims may be required to commit crimes, ranging from destruction of property to kidnapping. One-half of all hazing activities involve the use of alcohol,2 and 82% of hazing-related deaths involve alcohol.1

What is your role in treating hazing victims?

You might be called on to treat the psychological symptoms of hazing, including:

- depression

- anxiety

- acute stress syndrome

- alcohol- and drug-related delirium

- posttraumatic stress syndrome.

In addition, you might find yourself needing to:

Arrange for medical care immediately if the patient has a medical problem or an injury.

Contact a victim advocacy programif the victim has made allegations about, or there is evidence of, sexual assault, rape, other sexual injury, or physical or psychological violence.

Notify appropriate law enforcement personnel.

Notify the leadership of the organization (eg, team, school, club) within which the hazing occurred.

Perform a psychiatric assessment and provide treatment for the victim. Some symptoms seen in victims of hazing include sleep disturbance and insomnia, poor grades, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, feelings of low self-esteem and self-worth, trust issues, and symptoms commonly seen in patients with posttraumatic stress syndrome. Symptoms sometimes appear immediately after a hazing event; other times, they develop weeks later. Supportive counseling, stabilization, and advocacy are the immediate goals.

Provide education and treatment for the perpetrator. Unlike bullying, most hazing is not instituted to harm the victim but is seen as a tradition and ritual to increase commitment and bonding. The perpetrator might feel surprise and guilt as to the harm that was done to the victim. Observers of hazing rituals might be traumatized by viewing participants humiliated or abused, and both observers and perpetrators as participants may face legal consequences. Counseling and group debriefing provide education and help them cope with these issues.

Act as a consultant to schools, teams, and other organizations to ensure that group cohesion and team building is obtained in a way that benefits the group and does not harm a member or the organization.

Psychiatrists can provide literature and information especially to adolescent and young adult patients who are at highest risk of hazing. Handouts, informational brochures and posters and be placed in the waiting areas for patient to view. These can be found online (such as www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/safety/and-hazing.pdf) or obtained from local colleges and school systems.

1. Allan EJ, Madden M. Hazing in view: students at risk. http://www.stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/hazing_in_view_web1.pdf. Published March 11, 2008. Accessed May 18, 2015.

2. McBride HC. Parents beware: hazing poses significant danger to new college students. CRC Health. http://www.crchealth.com/treatment/treatment-for-teens/alcohol-addiction/hazing. Accessed May 18, 2015.

1. Allan EJ, Madden M. Hazing in view: students at risk. http://www.stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/hazing_in_view_web1.pdf. Published March 11, 2008. Accessed May 18, 2015.

2. McBride HC. Parents beware: hazing poses significant danger to new college students. CRC Health. http://www.crchealth.com/treatment/treatment-for-teens/alcohol-addiction/hazing. Accessed May 18, 2015.

A tool to assess behavioral problems in neurocognitive disorder and guide treatment

Non-drug treatment options, such as behavioral techniques and environment adjustment, should be considered before initiating pharmacotherapy in older patients with behavioral deregulation caused by a neurocognitive disorder. Before considering any interventions, including medical therapy, an evaluation and development of a profile of behavioral symptoms is warranted.

The purpose of such a profile is to:

- guide a patient-specific treatment plan

- measure treatment response (whether medication-related or otherwise).

Developing a profile for a patient can lead to a more tailored treatment plan. Such a plan includes identification of mitigating factors for the patient’s behavior and use of specific interventions, with a preference for non-medication interventions.

Profile assessment can guide treatment

The disruptive-behavior profile that I created (Table) can be used as an initial screening device; the score (1 through 4) in each domain indicates the intensity of intervention required. The profile also can be used to evaluate treatment response.