User login

How to talk to patients and their family after a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional clinical stage between normal aging and dementia. Together with aging, it is considered the most significant risk factor for developing dementia, often the Alzheimer’s type.1

MCI is a challenging neuropsychiatric diagnosis to discuss with patients and their family because it is characterized by overlapping features of normal aging and because of its heterogeneity of etiology, clinical presentation, and outcome.2,3 The evolution to dementia and the lack of effective treatments for preventing or forestalling this outcome can be difficult to address—particularly when the patient is in good health and has been leading a productive life.

Successful communication is key

You can take steps to communicate in a helpful way, build a strong treatment alliance, and reduce the potential for the iatrogenic effects of disclosing this diagnosis and its prognostic implications.

Clarify that your findings are consistent with the patient’s or family’s report of sustained and concerning change in cognition and, depending on the patient, concurrent alterations in affect, behavior, or both. Emphasize that these changes are disproportionately severe relative to expectations for the patient’s age and are not caused by psychiatric or clear-cut medical factors.

Highlight contexts in which the patient’s symptoms are likely to become more disruptive and impaired, and situations in which the patient can be expected to function more effectively.

Provide evidence-based support for the rate of progression of symptoms and functional impairment.3

Emphasize that major lifestyle adjustments usually are unnecessary in the absence of progression, especially for patients who are retired or not involved in endeavors that involve significant cognitive and executive functioning demands.

Discuss the role that cognition-enhancing medications might play in managing symptoms.4

Address indications for additional services, including formal psychiatric care for patients who have concomitant affective or behavioral symptoms and who are highly distressed by the diagnosis. Pair these services with longitudinal monitoring for possible exacerbation of symptoms.

Identify psychiatric, medical, and lifestyle factors that can increase the risk of dementia. Depending on the patient’s history, this might include diabetes, hypertension, elevated lipid levels, obesity, smoking, head trauma, depression, physical inactivity, and lack of intellectual stimulation.

Review compensatory strategies. In MCI predominantly amnestic type, for example, having the patient make systematic lists for shopping and other activities of daily living, as well as establishing routines for organizaton, can bolster successful coping.

If psychometric testing was not utilized to establish the diagnosis, discussion can include the value of performing such an assessment for a more finely tuned profile of preserved and impaired neurobehavioral functions. Such a profile can include test patterns that 1) have prognostic value with regard to the likelihood of progression to dementia and 2) establish a baseline against which you can assess stability or progression over time.5

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging- Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

2. Ellison JM, Harper DG, Berlow Y, et al. Beyond the “C” in MCI: noncognitive symptoms in amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(1):66-72.

3. Goveas JS, Dixon-Holbrook M, Kerwin D, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: how can you be sure? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(4):36-40, 46-50.

4. Doody RS, Ferris SH, Salloway S, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with MCI: a 48-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2009;72(18):1555-1561.

5. Summers MJ, Saunders NL. Neuropsychological measures predict decline to Alzheimer’s dementia from mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2012;26(4):498-508.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional clinical stage between normal aging and dementia. Together with aging, it is considered the most significant risk factor for developing dementia, often the Alzheimer’s type.1

MCI is a challenging neuropsychiatric diagnosis to discuss with patients and their family because it is characterized by overlapping features of normal aging and because of its heterogeneity of etiology, clinical presentation, and outcome.2,3 The evolution to dementia and the lack of effective treatments for preventing or forestalling this outcome can be difficult to address—particularly when the patient is in good health and has been leading a productive life.

Successful communication is key

You can take steps to communicate in a helpful way, build a strong treatment alliance, and reduce the potential for the iatrogenic effects of disclosing this diagnosis and its prognostic implications.

Clarify that your findings are consistent with the patient’s or family’s report of sustained and concerning change in cognition and, depending on the patient, concurrent alterations in affect, behavior, or both. Emphasize that these changes are disproportionately severe relative to expectations for the patient’s age and are not caused by psychiatric or clear-cut medical factors.

Highlight contexts in which the patient’s symptoms are likely to become more disruptive and impaired, and situations in which the patient can be expected to function more effectively.

Provide evidence-based support for the rate of progression of symptoms and functional impairment.3

Emphasize that major lifestyle adjustments usually are unnecessary in the absence of progression, especially for patients who are retired or not involved in endeavors that involve significant cognitive and executive functioning demands.

Discuss the role that cognition-enhancing medications might play in managing symptoms.4

Address indications for additional services, including formal psychiatric care for patients who have concomitant affective or behavioral symptoms and who are highly distressed by the diagnosis. Pair these services with longitudinal monitoring for possible exacerbation of symptoms.

Identify psychiatric, medical, and lifestyle factors that can increase the risk of dementia. Depending on the patient’s history, this might include diabetes, hypertension, elevated lipid levels, obesity, smoking, head trauma, depression, physical inactivity, and lack of intellectual stimulation.

Review compensatory strategies. In MCI predominantly amnestic type, for example, having the patient make systematic lists for shopping and other activities of daily living, as well as establishing routines for organizaton, can bolster successful coping.

If psychometric testing was not utilized to establish the diagnosis, discussion can include the value of performing such an assessment for a more finely tuned profile of preserved and impaired neurobehavioral functions. Such a profile can include test patterns that 1) have prognostic value with regard to the likelihood of progression to dementia and 2) establish a baseline against which you can assess stability or progression over time.5

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional clinical stage between normal aging and dementia. Together with aging, it is considered the most significant risk factor for developing dementia, often the Alzheimer’s type.1

MCI is a challenging neuropsychiatric diagnosis to discuss with patients and their family because it is characterized by overlapping features of normal aging and because of its heterogeneity of etiology, clinical presentation, and outcome.2,3 The evolution to dementia and the lack of effective treatments for preventing or forestalling this outcome can be difficult to address—particularly when the patient is in good health and has been leading a productive life.

Successful communication is key

You can take steps to communicate in a helpful way, build a strong treatment alliance, and reduce the potential for the iatrogenic effects of disclosing this diagnosis and its prognostic implications.

Clarify that your findings are consistent with the patient’s or family’s report of sustained and concerning change in cognition and, depending on the patient, concurrent alterations in affect, behavior, or both. Emphasize that these changes are disproportionately severe relative to expectations for the patient’s age and are not caused by psychiatric or clear-cut medical factors.

Highlight contexts in which the patient’s symptoms are likely to become more disruptive and impaired, and situations in which the patient can be expected to function more effectively.

Provide evidence-based support for the rate of progression of symptoms and functional impairment.3

Emphasize that major lifestyle adjustments usually are unnecessary in the absence of progression, especially for patients who are retired or not involved in endeavors that involve significant cognitive and executive functioning demands.

Discuss the role that cognition-enhancing medications might play in managing symptoms.4

Address indications for additional services, including formal psychiatric care for patients who have concomitant affective or behavioral symptoms and who are highly distressed by the diagnosis. Pair these services with longitudinal monitoring for possible exacerbation of symptoms.

Identify psychiatric, medical, and lifestyle factors that can increase the risk of dementia. Depending on the patient’s history, this might include diabetes, hypertension, elevated lipid levels, obesity, smoking, head trauma, depression, physical inactivity, and lack of intellectual stimulation.

Review compensatory strategies. In MCI predominantly amnestic type, for example, having the patient make systematic lists for shopping and other activities of daily living, as well as establishing routines for organizaton, can bolster successful coping.

If psychometric testing was not utilized to establish the diagnosis, discussion can include the value of performing such an assessment for a more finely tuned profile of preserved and impaired neurobehavioral functions. Such a profile can include test patterns that 1) have prognostic value with regard to the likelihood of progression to dementia and 2) establish a baseline against which you can assess stability or progression over time.5

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging- Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

2. Ellison JM, Harper DG, Berlow Y, et al. Beyond the “C” in MCI: noncognitive symptoms in amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(1):66-72.

3. Goveas JS, Dixon-Holbrook M, Kerwin D, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: how can you be sure? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(4):36-40, 46-50.

4. Doody RS, Ferris SH, Salloway S, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with MCI: a 48-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2009;72(18):1555-1561.

5. Summers MJ, Saunders NL. Neuropsychological measures predict decline to Alzheimer’s dementia from mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2012;26(4):498-508.

1. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging- Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

2. Ellison JM, Harper DG, Berlow Y, et al. Beyond the “C” in MCI: noncognitive symptoms in amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(1):66-72.

3. Goveas JS, Dixon-Holbrook M, Kerwin D, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: how can you be sure? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(4):36-40, 46-50.

4. Doody RS, Ferris SH, Salloway S, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with MCI: a 48-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2009;72(18):1555-1561.

5. Summers MJ, Saunders NL. Neuropsychological measures predict decline to Alzheimer’s dementia from mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2012;26(4):498-508.

Avoid hospitalization for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa by personalizing your care

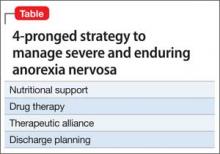

Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN) is persistent anorexia nervosa (AN) lasting for ≥7 years with or without a history of treatment. Evidence points to the effectiveness of a patient-tailored plan for treating SE-AN over any universal fix. Proper medication, therapeutic alliance, and strategic discharge planning are the ingredients for treating SE-AN that avoids re-hospitalization (Table).

Nutritional support and pharmacotherapy required

Comprehensive metabolic analysis and initiating nutrition should be the first priority for the medical team. Starved-state patients can have electrolyte and metabolic derangements that place them at risk of fatal arrhythmias or multi-system organ failure. Do not hesitate to initiate nasogastric tube feeding under the observation of a certified nutritionist when necessary for survival. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of olanzapine compared with placebo to increase body mass index (BMI) of hospitalized AN patients. Olanzapine was titrated from 2.5 to 10 mg/d over a 13-week period, and was associated with higher patient achievement of a BMI > 18.5 kg/m2.1

Although the patient is receiving nutritional support in conjunction with psychotropic medication, the road to BMI recovery can be long. Don’t forget that SE-AN can be incapacitating. In SE-AN, the fear of gaining weight is so severe that the idea of starvation-induced death initially might seem more palatable. Although counterintuitive, as the patient recovers metabolically, self-image deteriorates. Statements praising any new weight gain can derail any therapeutic relationship.

Therapeutic alliance is key

Establishing high-quality therapeutic alliance, as measured by the Helping Relationships Questionnaire, has been shown to have a positive outcome on eating disorder symptoms and comorbid depressed mood in later phases of SE-AN treatment.2,3 Although therapeutic alliance is individualized, maintaining open communication and reiterating how it is the patient’s decision to consume whole food at a level at which the feeding tube can be discontinued are good places to start treatment.

Proper discharge timing and transition to outpatient care for SE-AN patients is paramount. In multicenter studies, treatment ends too early in 57.8% of patients; discharge at sub-ideal BMI is linked to rehospitalization.3 Slower weight gain and delayed establishment of therapeutic alliance are predictors of patients who exit treatment programs too early.3 Clinicians who remain vigilant for the above metrics are less likely to feed into the unacceptably high rate of treatment failure for SE-AN.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bissada H, Tasca GA, Barber AM, et al. Olanzapine in the treatment of low body weight and obsessive thinking in women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(10):1281-1288.

2. Stiles-Shields C, Touyz S, Hay P, et al. Therapeutic alliance in two treatments for adults with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(8):783-789.

3. Sly R, Morgan JF, Mountford VA, et al. Predicting premature termination of hospitalised treatment for anorexia nervosa: the roles of therapeutic alliance, motivation, and behaviour change. Eat Behav. 2013;14(2):119-123.

Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN) is persistent anorexia nervosa (AN) lasting for ≥7 years with or without a history of treatment. Evidence points to the effectiveness of a patient-tailored plan for treating SE-AN over any universal fix. Proper medication, therapeutic alliance, and strategic discharge planning are the ingredients for treating SE-AN that avoids re-hospitalization (Table).

Nutritional support and pharmacotherapy required

Comprehensive metabolic analysis and initiating nutrition should be the first priority for the medical team. Starved-state patients can have electrolyte and metabolic derangements that place them at risk of fatal arrhythmias or multi-system organ failure. Do not hesitate to initiate nasogastric tube feeding under the observation of a certified nutritionist when necessary for survival. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of olanzapine compared with placebo to increase body mass index (BMI) of hospitalized AN patients. Olanzapine was titrated from 2.5 to 10 mg/d over a 13-week period, and was associated with higher patient achievement of a BMI > 18.5 kg/m2.1

Although the patient is receiving nutritional support in conjunction with psychotropic medication, the road to BMI recovery can be long. Don’t forget that SE-AN can be incapacitating. In SE-AN, the fear of gaining weight is so severe that the idea of starvation-induced death initially might seem more palatable. Although counterintuitive, as the patient recovers metabolically, self-image deteriorates. Statements praising any new weight gain can derail any therapeutic relationship.

Therapeutic alliance is key

Establishing high-quality therapeutic alliance, as measured by the Helping Relationships Questionnaire, has been shown to have a positive outcome on eating disorder symptoms and comorbid depressed mood in later phases of SE-AN treatment.2,3 Although therapeutic alliance is individualized, maintaining open communication and reiterating how it is the patient’s decision to consume whole food at a level at which the feeding tube can be discontinued are good places to start treatment.

Proper discharge timing and transition to outpatient care for SE-AN patients is paramount. In multicenter studies, treatment ends too early in 57.8% of patients; discharge at sub-ideal BMI is linked to rehospitalization.3 Slower weight gain and delayed establishment of therapeutic alliance are predictors of patients who exit treatment programs too early.3 Clinicians who remain vigilant for the above metrics are less likely to feed into the unacceptably high rate of treatment failure for SE-AN.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN) is persistent anorexia nervosa (AN) lasting for ≥7 years with or without a history of treatment. Evidence points to the effectiveness of a patient-tailored plan for treating SE-AN over any universal fix. Proper medication, therapeutic alliance, and strategic discharge planning are the ingredients for treating SE-AN that avoids re-hospitalization (Table).

Nutritional support and pharmacotherapy required

Comprehensive metabolic analysis and initiating nutrition should be the first priority for the medical team. Starved-state patients can have electrolyte and metabolic derangements that place them at risk of fatal arrhythmias or multi-system organ failure. Do not hesitate to initiate nasogastric tube feeding under the observation of a certified nutritionist when necessary for survival. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of olanzapine compared with placebo to increase body mass index (BMI) of hospitalized AN patients. Olanzapine was titrated from 2.5 to 10 mg/d over a 13-week period, and was associated with higher patient achievement of a BMI > 18.5 kg/m2.1

Although the patient is receiving nutritional support in conjunction with psychotropic medication, the road to BMI recovery can be long. Don’t forget that SE-AN can be incapacitating. In SE-AN, the fear of gaining weight is so severe that the idea of starvation-induced death initially might seem more palatable. Although counterintuitive, as the patient recovers metabolically, self-image deteriorates. Statements praising any new weight gain can derail any therapeutic relationship.

Therapeutic alliance is key

Establishing high-quality therapeutic alliance, as measured by the Helping Relationships Questionnaire, has been shown to have a positive outcome on eating disorder symptoms and comorbid depressed mood in later phases of SE-AN treatment.2,3 Although therapeutic alliance is individualized, maintaining open communication and reiterating how it is the patient’s decision to consume whole food at a level at which the feeding tube can be discontinued are good places to start treatment.

Proper discharge timing and transition to outpatient care for SE-AN patients is paramount. In multicenter studies, treatment ends too early in 57.8% of patients; discharge at sub-ideal BMI is linked to rehospitalization.3 Slower weight gain and delayed establishment of therapeutic alliance are predictors of patients who exit treatment programs too early.3 Clinicians who remain vigilant for the above metrics are less likely to feed into the unacceptably high rate of treatment failure for SE-AN.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bissada H, Tasca GA, Barber AM, et al. Olanzapine in the treatment of low body weight and obsessive thinking in women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(10):1281-1288.

2. Stiles-Shields C, Touyz S, Hay P, et al. Therapeutic alliance in two treatments for adults with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(8):783-789.

3. Sly R, Morgan JF, Mountford VA, et al. Predicting premature termination of hospitalised treatment for anorexia nervosa: the roles of therapeutic alliance, motivation, and behaviour change. Eat Behav. 2013;14(2):119-123.

1. Bissada H, Tasca GA, Barber AM, et al. Olanzapine in the treatment of low body weight and obsessive thinking in women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(10):1281-1288.

2. Stiles-Shields C, Touyz S, Hay P, et al. Therapeutic alliance in two treatments for adults with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(8):783-789.

3. Sly R, Morgan JF, Mountford VA, et al. Predicting premature termination of hospitalised treatment for anorexia nervosa: the roles of therapeutic alliance, motivation, and behaviour change. Eat Behav. 2013;14(2):119-123.

Take caution: Look for DISTURBED behaviors when you assess violence risk

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

Take caution: Look for DISTURBED behaviors when you assess violence risk

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impulsivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single (known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings— 2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

Take caution: Look for DISTURBED behaviors when you assess violence risk

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impusivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be aware of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings—2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impusivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be aware of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings—2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

A common misconception is that persons who are mentally ill are inherently dangerous. However, there is, at most, a weak overall relationship between mental illness and violence. Increased violence is more likely to occur during periods of acute psychiatric symptoms.1 Because few patients evaluated in most clinical settings will commit a violent act, it is important to assess for specific risk factors for violence to guide clinical decision making.

The acronym DISTURBED can be a reminder about important patient-specific features that correlate with violence. There are several variables to consider when identifying persons who are more likely to commit acts of violence.2

Demographics. Young age, male sex, cognitive deficits, less formal education, unemployment, financial hardship, and homelessness are associated with an increased risk of violence. A person’s living environment and ongoing social circumstances are important considerations when assessing violence risk.

Impusivity. Persons who display impulsive behaviors generally are more likely to behave violently. This is particularly true in persons who have been given a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or borderline personality disorder. Impulsivity often can be treated with medication, behavioral therapy, and other psychotherapeutic modalities.

Substance use is associated with an increased risk of violence in people with and without other mental health issues. Alcohol can increase the likelihood of violence through intoxication, withdrawal, or brain changes related to chronic drinking. Some illicit drugs are associated with violence, including phencyclidine, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, anabolic steroids, and so-called bath salts. Be cautious when treating a patient who is intoxicated with one or more of these substances.

Threats. Persons who express a threat are more likely to behave violently3; those who voice threats against an identified target should be taken seriously. The more specific the threat, the more consideration it should be given. In a clinical setting, the potential target should be informed as soon as possible about the threat. If a patient is voicing a threat against a person outside the clinical setting, you may have a duty to protect by reporting that threat to law enforcement.

Untreated psychosis. Be aware of patients who have untreated or undertreated symptoms, including psychosis and substance intoxication. Patients in a triage setting or who are newly admitted to an inpatient unit often present the greatest risk because their symptoms have not been treated. People with paranoid delusions are at a higher risk of assaulting their perceived persecutors. Those who are highly disorganized also are more prone to lash out and commit a violent act.4,5

Repeat violence. The best predictor of violence is a history of violence. The severity of the violent acts is an important consideration. Even a person who has only a single known) past violent act can pose a high risk if the act was murder, rape, or another highly violent assault. Learning details about past assaults, through reviewing available records or gathering collateral information, is important when assessing violence risk.

Behaviors. There are physical warning signs that often are observed immediately before a person commits a violent act. Potential warning signs include: punching a wall or breaking objects; tightening of facial muscles; clenching of fists; and pacing. These behaviors suggest a risk of imminent violence and should be closely monitored when assessing a patient who might be prone to violence. If a patient does not respond to redirection, he (she) may require staff intervention.

Eagerness. Much like when assessing the risk of suicide, intent is an important consideration in assessing the risk of violence. A person who is eager to commit an act of violence presents significant risk. Basic inquiries about homicidal ideation are insufficient; instead, explore potential responses to situations that might have a direct impact on the individual patient. For example, if the patient has had frequent disagreements with a family member, inquiring about hypothetical violent scenarios involving that family member would be valuable.

Distress. Persons who are concerned about safety often are inclined to lash out in perceived self-defense. For example, fear often is reported by psychiatric inpatients immediately before they commit an act of violence. In inpatient psychiatric units, providing a quiet room, or a similar amenity, can help prevent an assault by a patient who feels cornered or afraid. The staff can ease patients’ concerns by taking a calm and caring approach to addressing their needs.

Valuable tool for maintaining a safe environment

We recommend that clinicians—especially those who have little clinical experience (medical students, residents)—refer to this mnemonic before starting work in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings—2 settings in which assessment of violence risk is common. The mnemonic will help when gathering information to assess important risk factors for violence.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.

2. Tardiff K. Clinical risk assessment of violence. In: Simon RI, Tardiff K, eds. Textbook of violence assessment and management. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008:3-16.

3. Maier GJ. Managing threatening behavior. The role of talk down and talk up. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996;34(6):25-30.

4. McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(2): 133-137.

5. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC. Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):505-517.

1. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393-401.