User login

Most Potentially Hepatotoxic Meds Revealed: Real-World Data Analysis

TOPLINE:

An analysis of real-world evidence identified 17 medications, many not previously regarded as potentially hepatotoxic, that have high incidence rates of patient hospitalization for acute liver injury (ALI), offering insights on how to better determine which drugs carry the most significant risk and warrant liver monitoring.

METHODOLOGY:

- Without a systematic approach to classifying medications’ hepatotoxic risk, researchers have used case reports published on the National Institutes of Health’s LiverTox, which doesn’t account for the number of people exposed, to categorize drugs’ likelihood of causing ALI. The objective was to identify the most potentially hepatotoxic medications using real-world incidence rates of severe ALI.

- Researchers analyzed US Department of Veterans Affairs electronic health record data for almost 7.9 million individuals (mean age, 64.4 years; 92.5% men) without preexisting liver or biliary disease who were initiated in an outpatient setting on any one of 194 medications with four or more published reports of hepatotoxicity. Drugs delivered by injection or intravenously, prescribed for alcohol use disorder or liver disease treatment, or used as an anticoagulant were not included in the study.

- The primary outcome measured was hospitalization for severe ALI, defined by alanine aminotransferase levels > 120 U/L and total bilirubin levels > 2.0 mg/dL or the international normalized ratio ≥ 1.5 and total bilirubin levels > 2.0 mg/dL within the first 2 days of admission.

- Researchers organized the medications into groups on the basis of observed rates of severe ALI per 10,000 person-years and classified drugs with 10 or more hospitalizations (group 1) and 5-9.9 hospitalizations (group 2) as the most potentially hepatotoxic. The study period was October 2000 through September 2021.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among the study population, 1739 hospitalizations for severe ALI were identified. Incidence rates of severe ALI varied widely by medication, from 0 to 86.4 events per 10,000 person-years.

- Seventeen medications were classified as the most potentially hepatotoxic (groups 1 and 2). Seven of them (stavudine, erlotinib, lenalidomide or thalidomide, chlorpromazine, metronidazole, prochlorperazine, and isoniazid) had incidence rates of ≥ 10 events per 10,000 person-years. The other 10 medications (moxifloxacin, azathioprine, levofloxacin, clarithromycin, ketoconazole, fluconazole, captopril, amoxicillin-clavulanate, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and ciprofloxacin) showed incidence rates of 5-9.9 events per 10,000 person-years.

- Of the 17 most hepatotoxic medications, 11 (64%) were not classified as highly hepatotoxic in the published case reports, suggesting a discrepancy between real-world data and case report categorizations.

- Similarly, several medications, including some statins, identified as low-risk in this study were classified as among the most hepatotoxic in the published case reports.

IN PRACTICE:

“Categorization of hepatotoxicity based on the number of published case reports did not accurately reflect observed rates of severe ALI (acute liver injury),” the researchers wrote. “This study represents a systematic, reproducible approach to using real-world data to measure rates of severe ALI following medication initiation among patients without liver or biliary disease…Patients initiating a medication with a high rate of severe ALI might require closer monitoring of liver-related laboratory tests to detect evolving hepatic dysfunction earlier, which might improve prognosis.”

The study illustrates the potential to use electronic health record data to “revolutionize how we characterize drug-related toxic effects,” not just on the liver but other organs, Grace Y. Zhang, MD, and Jessica B. Rubin, MD, MPH, of the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “If curated and disseminated effectively…such evidence will undoubtedly improve clinical decision-making and allow for more informed patient counseling regarding the true risks of starting or discontinuing medications.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Jessie Torgersen, MD, MHS, MSCE, of the Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers listed several limitations, including the possibility that reliance on laboratory tests for ascertainment of acute liver injuries could introduce surveillance bias. The study focused on a population predominantly consisting of men without preexisting liver or biliary disease, so the findings may not be generalizable to women or individuals with liver disease. Additionally, researchers did not perform a causality assessment of all outcomes, did not study medications with fewer than four published case reports, and did not evaluate the influence of dosage.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was partly funded by several grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors declared receiving grants and personal fees from some of the funding agencies and other sources outside of this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An analysis of real-world evidence identified 17 medications, many not previously regarded as potentially hepatotoxic, that have high incidence rates of patient hospitalization for acute liver injury (ALI), offering insights on how to better determine which drugs carry the most significant risk and warrant liver monitoring.

METHODOLOGY:

- Without a systematic approach to classifying medications’ hepatotoxic risk, researchers have used case reports published on the National Institutes of Health’s LiverTox, which doesn’t account for the number of people exposed, to categorize drugs’ likelihood of causing ALI. The objective was to identify the most potentially hepatotoxic medications using real-world incidence rates of severe ALI.

- Researchers analyzed US Department of Veterans Affairs electronic health record data for almost 7.9 million individuals (mean age, 64.4 years; 92.5% men) without preexisting liver or biliary disease who were initiated in an outpatient setting on any one of 194 medications with four or more published reports of hepatotoxicity. Drugs delivered by injection or intravenously, prescribed for alcohol use disorder or liver disease treatment, or used as an anticoagulant were not included in the study.

- The primary outcome measured was hospitalization for severe ALI, defined by alanine aminotransferase levels > 120 U/L and total bilirubin levels > 2.0 mg/dL or the international normalized ratio ≥ 1.5 and total bilirubin levels > 2.0 mg/dL within the first 2 days of admission.

- Researchers organized the medications into groups on the basis of observed rates of severe ALI per 10,000 person-years and classified drugs with 10 or more hospitalizations (group 1) and 5-9.9 hospitalizations (group 2) as the most potentially hepatotoxic. The study period was October 2000 through September 2021.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among the study population, 1739 hospitalizations for severe ALI were identified. Incidence rates of severe ALI varied widely by medication, from 0 to 86.4 events per 10,000 person-years.

- Seventeen medications were classified as the most potentially hepatotoxic (groups 1 and 2). Seven of them (stavudine, erlotinib, lenalidomide or thalidomide, chlorpromazine, metronidazole, prochlorperazine, and isoniazid) had incidence rates of ≥ 10 events per 10,000 person-years. The other 10 medications (moxifloxacin, azathioprine, levofloxacin, clarithromycin, ketoconazole, fluconazole, captopril, amoxicillin-clavulanate, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and ciprofloxacin) showed incidence rates of 5-9.9 events per 10,000 person-years.

- Of the 17 most hepatotoxic medications, 11 (64%) were not classified as highly hepatotoxic in the published case reports, suggesting a discrepancy between real-world data and case report categorizations.

- Similarly, several medications, including some statins, identified as low-risk in this study were classified as among the most hepatotoxic in the published case reports.

IN PRACTICE:

“Categorization of hepatotoxicity based on the number of published case reports did not accurately reflect observed rates of severe ALI (acute liver injury),” the researchers wrote. “This study represents a systematic, reproducible approach to using real-world data to measure rates of severe ALI following medication initiation among patients without liver or biliary disease…Patients initiating a medication with a high rate of severe ALI might require closer monitoring of liver-related laboratory tests to detect evolving hepatic dysfunction earlier, which might improve prognosis.”

The study illustrates the potential to use electronic health record data to “revolutionize how we characterize drug-related toxic effects,” not just on the liver but other organs, Grace Y. Zhang, MD, and Jessica B. Rubin, MD, MPH, of the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “If curated and disseminated effectively…such evidence will undoubtedly improve clinical decision-making and allow for more informed patient counseling regarding the true risks of starting or discontinuing medications.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Jessie Torgersen, MD, MHS, MSCE, of the Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers listed several limitations, including the possibility that reliance on laboratory tests for ascertainment of acute liver injuries could introduce surveillance bias. The study focused on a population predominantly consisting of men without preexisting liver or biliary disease, so the findings may not be generalizable to women or individuals with liver disease. Additionally, researchers did not perform a causality assessment of all outcomes, did not study medications with fewer than four published case reports, and did not evaluate the influence of dosage.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was partly funded by several grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors declared receiving grants and personal fees from some of the funding agencies and other sources outside of this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An analysis of real-world evidence identified 17 medications, many not previously regarded as potentially hepatotoxic, that have high incidence rates of patient hospitalization for acute liver injury (ALI), offering insights on how to better determine which drugs carry the most significant risk and warrant liver monitoring.

METHODOLOGY:

- Without a systematic approach to classifying medications’ hepatotoxic risk, researchers have used case reports published on the National Institutes of Health’s LiverTox, which doesn’t account for the number of people exposed, to categorize drugs’ likelihood of causing ALI. The objective was to identify the most potentially hepatotoxic medications using real-world incidence rates of severe ALI.

- Researchers analyzed US Department of Veterans Affairs electronic health record data for almost 7.9 million individuals (mean age, 64.4 years; 92.5% men) without preexisting liver or biliary disease who were initiated in an outpatient setting on any one of 194 medications with four or more published reports of hepatotoxicity. Drugs delivered by injection or intravenously, prescribed for alcohol use disorder or liver disease treatment, or used as an anticoagulant were not included in the study.

- The primary outcome measured was hospitalization for severe ALI, defined by alanine aminotransferase levels > 120 U/L and total bilirubin levels > 2.0 mg/dL or the international normalized ratio ≥ 1.5 and total bilirubin levels > 2.0 mg/dL within the first 2 days of admission.

- Researchers organized the medications into groups on the basis of observed rates of severe ALI per 10,000 person-years and classified drugs with 10 or more hospitalizations (group 1) and 5-9.9 hospitalizations (group 2) as the most potentially hepatotoxic. The study period was October 2000 through September 2021.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among the study population, 1739 hospitalizations for severe ALI were identified. Incidence rates of severe ALI varied widely by medication, from 0 to 86.4 events per 10,000 person-years.

- Seventeen medications were classified as the most potentially hepatotoxic (groups 1 and 2). Seven of them (stavudine, erlotinib, lenalidomide or thalidomide, chlorpromazine, metronidazole, prochlorperazine, and isoniazid) had incidence rates of ≥ 10 events per 10,000 person-years. The other 10 medications (moxifloxacin, azathioprine, levofloxacin, clarithromycin, ketoconazole, fluconazole, captopril, amoxicillin-clavulanate, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and ciprofloxacin) showed incidence rates of 5-9.9 events per 10,000 person-years.

- Of the 17 most hepatotoxic medications, 11 (64%) were not classified as highly hepatotoxic in the published case reports, suggesting a discrepancy between real-world data and case report categorizations.

- Similarly, several medications, including some statins, identified as low-risk in this study were classified as among the most hepatotoxic in the published case reports.

IN PRACTICE:

“Categorization of hepatotoxicity based on the number of published case reports did not accurately reflect observed rates of severe ALI (acute liver injury),” the researchers wrote. “This study represents a systematic, reproducible approach to using real-world data to measure rates of severe ALI following medication initiation among patients without liver or biliary disease…Patients initiating a medication with a high rate of severe ALI might require closer monitoring of liver-related laboratory tests to detect evolving hepatic dysfunction earlier, which might improve prognosis.”

The study illustrates the potential to use electronic health record data to “revolutionize how we characterize drug-related toxic effects,” not just on the liver but other organs, Grace Y. Zhang, MD, and Jessica B. Rubin, MD, MPH, of the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “If curated and disseminated effectively…such evidence will undoubtedly improve clinical decision-making and allow for more informed patient counseling regarding the true risks of starting or discontinuing medications.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Jessie Torgersen, MD, MHS, MSCE, of the Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, was published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers listed several limitations, including the possibility that reliance on laboratory tests for ascertainment of acute liver injuries could introduce surveillance bias. The study focused on a population predominantly consisting of men without preexisting liver or biliary disease, so the findings may not be generalizable to women or individuals with liver disease. Additionally, researchers did not perform a causality assessment of all outcomes, did not study medications with fewer than four published case reports, and did not evaluate the influence of dosage.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was partly funded by several grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors declared receiving grants and personal fees from some of the funding agencies and other sources outside of this work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Buprenorphine One of Many Options For Pain Relief In Oldest Adults

Some degree of pain is inevitable in older individuals, and as people pass 80 years of age, the harms of medications used to control chronic pain increase. Pain-reducing medication use in this age group may cause inflammation, gastric bleeding, kidney damage, or constipation.

These risks may lead some clinicians to avoid aggressive pain treatment in their eldest patients, resulting in unnecessary suffering.

“Pain causes harm beyond just the physical suffering associated with it,” said Diane Meier, MD, a geriatrician and palliative care specialist at Mount Sinai Medicine in New York City who treats many people in their 80s and 90s.

Downstream effects of untreated pain could include a loss of mobility and isolation, Dr. Meier said. And, as these harms are mounting, some clinicians may avoid using an analgesic that could bring great relief: buprenorphine.

“People think about buprenorphine like they think about methadone,” Dr. Meier said, as something prescribed to treat substance use disorder. In reality, it is an effective analgesic in other situations.

Buprenorphine is better at treating chronic pain than other opioids that carry a higher addiction risk and often cause constipation in elderly patients. Buprenorphine is easier on the kidneys and has a lower addiction risk than opioids like oxycodone.

The transdermal patch form of buprenorphine (Butrans, PurduePharma) is changed weekly and starts at low doses.

“There’s an adage in geriatrics: start low and go slow,” said Jessica Merlin, MD, PhD, a palliative care and addiction medicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Merlin recommends beginning elderly patients with chronic pain on a 10-microgram/hour dose of Butrans, among the lowest doses available. Physicians could monitor side effects, which will generally be mild, with the aim of never increasing the dose if pain is managed.

Nonpharmacologic Remedies, Drug Considerations

“Nonpharmacologic therapy is very underutilized,” Dr. Merlin said, even though multiple alternatives to medications can improve chronic pain symptoms at any age.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy or acceptance and commitment therapy can both help people reduce the impact of pain, Dr. Merlin said. And for people who can do so, physical therapy programs, yoga, or tai chi are all ways to strengthen the body’s defenses against pain, Dr. Merlin added.

Sometimes medication is necessary, however.

“You can’t get an older person to participate in rehab if they are in severe pain,” Dr. Meier said, adding that judicious use of medications should go hand in hand with nonpharmacologic treatment.

When medications are unavoidable, internist Douglas S. Paauw, MD, starts with topical injections at the site of the pain — a troublesome joint, for example — rather than systemic medications that affect multiple organs and the brain.

“We try not to flood their body with meds” for localized problems, Dr. Paauw said, whose goal when treating elderly patients with pain is to improve their daily functioning and quality of life.

Dr. Paauw works at the University of Washington in Seattle and treats people who are approaching 100 years old. As some of his patients have grown older, Dr. Paauw’s interest in effective pain management has grown; he thinks that all internists and family medicine physician need to know how to manage chronic pain in their eldest patients.

“Were you able to play with your grandkid? Were you able to go grocery shopping? Were you able to take a walk outside?” These are the kinds of improvements Dr. Paauw hopes to see in older patients, recognizing that the wear and tear of life — orthopedic stresses or healed fractures that cause lingering pain — make it impossible for many older people to be pain free.

Pain is often spread throughout the body rather than focusing at one point, which requires systemic medications if physical therapy and similar approaches have not reduced pain. Per American Geriatrics Society (AGS) guidelines, in this situation Dr. Paauw starts with acetaminophen (Tylenol) as the lowest-risk systemic pain treatment.

Dr. Pauuw often counsels older patients to begin with 2 grams/day of acetaminophen and then progress to 3 grams if the lower dose has manageable side effects, rather than the standard dose of 4 grams that he feels is geared toward younger patients.

When acetaminophen doesn’t reduce pain sufficiently, or aggravates inflammation, Dr. Paauw may use the nerve pain medication pregabalin, or the antidepressant duloxetine — especially if the pain appears to be neuropathic.

Tricyclic antidepressants used to be recommended for neuropathic pain in older adults, but are now on the AGS’s Beers Criteria of drugs to avoid in elderly patients due to risk of causing dizziness or cardiac stress. Dr. Paauw might still use a tricyclic, but only after a careful risk-benefit analysis.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen (Motrin) or naproxen (Aleve) could work in short bursts, Dr. Paauw said, although they may cause stomach bleeding or kidney damage in older patients.

This is why NSAIDs are not recommended by the AGS for chronic pain management. And opioids like oxycodone don’t work long at low doses, often leading to dose escalation and addiction.

“The American Geriatrics Society really puts opioids down at the bottom of the list,” Dr. Paauw said, to be used “judiciously and rarely.”

Opioids may interact with other drugs to increase risk of a fall, Dr. Meier added, making them inadvisable for older patients who live alone.

“That’s why knowing something about buprenorphine is so important,” Dr. Meier said.

Dr. Meier and Dr. Paauw are on the editorial board for Internal Medicine News. Dr. Merlin is a trainer for the Center to Advance Palliative Care, which Dr. Meier founded.

Some degree of pain is inevitable in older individuals, and as people pass 80 years of age, the harms of medications used to control chronic pain increase. Pain-reducing medication use in this age group may cause inflammation, gastric bleeding, kidney damage, or constipation.

These risks may lead some clinicians to avoid aggressive pain treatment in their eldest patients, resulting in unnecessary suffering.

“Pain causes harm beyond just the physical suffering associated with it,” said Diane Meier, MD, a geriatrician and palliative care specialist at Mount Sinai Medicine in New York City who treats many people in their 80s and 90s.

Downstream effects of untreated pain could include a loss of mobility and isolation, Dr. Meier said. And, as these harms are mounting, some clinicians may avoid using an analgesic that could bring great relief: buprenorphine.

“People think about buprenorphine like they think about methadone,” Dr. Meier said, as something prescribed to treat substance use disorder. In reality, it is an effective analgesic in other situations.

Buprenorphine is better at treating chronic pain than other opioids that carry a higher addiction risk and often cause constipation in elderly patients. Buprenorphine is easier on the kidneys and has a lower addiction risk than opioids like oxycodone.

The transdermal patch form of buprenorphine (Butrans, PurduePharma) is changed weekly and starts at low doses.

“There’s an adage in geriatrics: start low and go slow,” said Jessica Merlin, MD, PhD, a palliative care and addiction medicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Merlin recommends beginning elderly patients with chronic pain on a 10-microgram/hour dose of Butrans, among the lowest doses available. Physicians could monitor side effects, which will generally be mild, with the aim of never increasing the dose if pain is managed.

Nonpharmacologic Remedies, Drug Considerations

“Nonpharmacologic therapy is very underutilized,” Dr. Merlin said, even though multiple alternatives to medications can improve chronic pain symptoms at any age.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy or acceptance and commitment therapy can both help people reduce the impact of pain, Dr. Merlin said. And for people who can do so, physical therapy programs, yoga, or tai chi are all ways to strengthen the body’s defenses against pain, Dr. Merlin added.

Sometimes medication is necessary, however.

“You can’t get an older person to participate in rehab if they are in severe pain,” Dr. Meier said, adding that judicious use of medications should go hand in hand with nonpharmacologic treatment.

When medications are unavoidable, internist Douglas S. Paauw, MD, starts with topical injections at the site of the pain — a troublesome joint, for example — rather than systemic medications that affect multiple organs and the brain.

“We try not to flood their body with meds” for localized problems, Dr. Paauw said, whose goal when treating elderly patients with pain is to improve their daily functioning and quality of life.

Dr. Paauw works at the University of Washington in Seattle and treats people who are approaching 100 years old. As some of his patients have grown older, Dr. Paauw’s interest in effective pain management has grown; he thinks that all internists and family medicine physician need to know how to manage chronic pain in their eldest patients.

“Were you able to play with your grandkid? Were you able to go grocery shopping? Were you able to take a walk outside?” These are the kinds of improvements Dr. Paauw hopes to see in older patients, recognizing that the wear and tear of life — orthopedic stresses or healed fractures that cause lingering pain — make it impossible for many older people to be pain free.

Pain is often spread throughout the body rather than focusing at one point, which requires systemic medications if physical therapy and similar approaches have not reduced pain. Per American Geriatrics Society (AGS) guidelines, in this situation Dr. Paauw starts with acetaminophen (Tylenol) as the lowest-risk systemic pain treatment.

Dr. Pauuw often counsels older patients to begin with 2 grams/day of acetaminophen and then progress to 3 grams if the lower dose has manageable side effects, rather than the standard dose of 4 grams that he feels is geared toward younger patients.

When acetaminophen doesn’t reduce pain sufficiently, or aggravates inflammation, Dr. Paauw may use the nerve pain medication pregabalin, or the antidepressant duloxetine — especially if the pain appears to be neuropathic.

Tricyclic antidepressants used to be recommended for neuropathic pain in older adults, but are now on the AGS’s Beers Criteria of drugs to avoid in elderly patients due to risk of causing dizziness or cardiac stress. Dr. Paauw might still use a tricyclic, but only after a careful risk-benefit analysis.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen (Motrin) or naproxen (Aleve) could work in short bursts, Dr. Paauw said, although they may cause stomach bleeding or kidney damage in older patients.

This is why NSAIDs are not recommended by the AGS for chronic pain management. And opioids like oxycodone don’t work long at low doses, often leading to dose escalation and addiction.

“The American Geriatrics Society really puts opioids down at the bottom of the list,” Dr. Paauw said, to be used “judiciously and rarely.”

Opioids may interact with other drugs to increase risk of a fall, Dr. Meier added, making them inadvisable for older patients who live alone.

“That’s why knowing something about buprenorphine is so important,” Dr. Meier said.

Dr. Meier and Dr. Paauw are on the editorial board for Internal Medicine News. Dr. Merlin is a trainer for the Center to Advance Palliative Care, which Dr. Meier founded.

Some degree of pain is inevitable in older individuals, and as people pass 80 years of age, the harms of medications used to control chronic pain increase. Pain-reducing medication use in this age group may cause inflammation, gastric bleeding, kidney damage, or constipation.

These risks may lead some clinicians to avoid aggressive pain treatment in their eldest patients, resulting in unnecessary suffering.

“Pain causes harm beyond just the physical suffering associated with it,” said Diane Meier, MD, a geriatrician and palliative care specialist at Mount Sinai Medicine in New York City who treats many people in their 80s and 90s.

Downstream effects of untreated pain could include a loss of mobility and isolation, Dr. Meier said. And, as these harms are mounting, some clinicians may avoid using an analgesic that could bring great relief: buprenorphine.

“People think about buprenorphine like they think about methadone,” Dr. Meier said, as something prescribed to treat substance use disorder. In reality, it is an effective analgesic in other situations.

Buprenorphine is better at treating chronic pain than other opioids that carry a higher addiction risk and often cause constipation in elderly patients. Buprenorphine is easier on the kidneys and has a lower addiction risk than opioids like oxycodone.

The transdermal patch form of buprenorphine (Butrans, PurduePharma) is changed weekly and starts at low doses.

“There’s an adage in geriatrics: start low and go slow,” said Jessica Merlin, MD, PhD, a palliative care and addiction medicine physician at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Merlin recommends beginning elderly patients with chronic pain on a 10-microgram/hour dose of Butrans, among the lowest doses available. Physicians could monitor side effects, which will generally be mild, with the aim of never increasing the dose if pain is managed.

Nonpharmacologic Remedies, Drug Considerations

“Nonpharmacologic therapy is very underutilized,” Dr. Merlin said, even though multiple alternatives to medications can improve chronic pain symptoms at any age.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy or acceptance and commitment therapy can both help people reduce the impact of pain, Dr. Merlin said. And for people who can do so, physical therapy programs, yoga, or tai chi are all ways to strengthen the body’s defenses against pain, Dr. Merlin added.

Sometimes medication is necessary, however.

“You can’t get an older person to participate in rehab if they are in severe pain,” Dr. Meier said, adding that judicious use of medications should go hand in hand with nonpharmacologic treatment.

When medications are unavoidable, internist Douglas S. Paauw, MD, starts with topical injections at the site of the pain — a troublesome joint, for example — rather than systemic medications that affect multiple organs and the brain.

“We try not to flood their body with meds” for localized problems, Dr. Paauw said, whose goal when treating elderly patients with pain is to improve their daily functioning and quality of life.

Dr. Paauw works at the University of Washington in Seattle and treats people who are approaching 100 years old. As some of his patients have grown older, Dr. Paauw’s interest in effective pain management has grown; he thinks that all internists and family medicine physician need to know how to manage chronic pain in their eldest patients.

“Were you able to play with your grandkid? Were you able to go grocery shopping? Were you able to take a walk outside?” These are the kinds of improvements Dr. Paauw hopes to see in older patients, recognizing that the wear and tear of life — orthopedic stresses or healed fractures that cause lingering pain — make it impossible for many older people to be pain free.

Pain is often spread throughout the body rather than focusing at one point, which requires systemic medications if physical therapy and similar approaches have not reduced pain. Per American Geriatrics Society (AGS) guidelines, in this situation Dr. Paauw starts with acetaminophen (Tylenol) as the lowest-risk systemic pain treatment.

Dr. Pauuw often counsels older patients to begin with 2 grams/day of acetaminophen and then progress to 3 grams if the lower dose has manageable side effects, rather than the standard dose of 4 grams that he feels is geared toward younger patients.

When acetaminophen doesn’t reduce pain sufficiently, or aggravates inflammation, Dr. Paauw may use the nerve pain medication pregabalin, or the antidepressant duloxetine — especially if the pain appears to be neuropathic.

Tricyclic antidepressants used to be recommended for neuropathic pain in older adults, but are now on the AGS’s Beers Criteria of drugs to avoid in elderly patients due to risk of causing dizziness or cardiac stress. Dr. Paauw might still use a tricyclic, but only after a careful risk-benefit analysis.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen (Motrin) or naproxen (Aleve) could work in short bursts, Dr. Paauw said, although they may cause stomach bleeding or kidney damage in older patients.

This is why NSAIDs are not recommended by the AGS for chronic pain management. And opioids like oxycodone don’t work long at low doses, often leading to dose escalation and addiction.

“The American Geriatrics Society really puts opioids down at the bottom of the list,” Dr. Paauw said, to be used “judiciously and rarely.”

Opioids may interact with other drugs to increase risk of a fall, Dr. Meier added, making them inadvisable for older patients who live alone.

“That’s why knowing something about buprenorphine is so important,” Dr. Meier said.

Dr. Meier and Dr. Paauw are on the editorial board for Internal Medicine News. Dr. Merlin is a trainer for the Center to Advance Palliative Care, which Dr. Meier founded.

Long-Term Assessment of Weight Loss Medications in a Veteran Population

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9 as overweight and those with a BMI > 30 as obese (obesity classes: I, BMI 30 to 34.9; II, BMI 35 to 39.9; and III, BMI ≥ 40).1 In 2011, the CDC estimated that 27.4% of adults in the United States were obese; less than a decade later, that number increased to 31.9%.1 In that same period, the percentage of adults in Indiana classified as obese increased from 30.8% to 36.8%.1 About 1 in 14 individuals in the US have class III obesity and 86% of veterans are either overweight or obese.2

High medical expenses can likely be attributed to the long-term health consequences of obesity. Compared to those with a healthy weight, individuals who are overweight or obese are at an increased risk for high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, high triglyceride levels, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, cancer, mental health disorders, body pain, low quality of life, and death.3 Many of these conditions lead to increased health care needs, medication needs, hospitalizations, and overall health care system use.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of obesity have been produced by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society; the Endocrine Society; the American Diabetes Association; and the US Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Defense. Each follows a general algorithm to manage and prevent adverse effects (AEs) related to obesity. General practice is to assess a patient for elevated BMI (> 25), implement intense lifestyle modifications including calorie restriction and exercise, reassess for a maintained 5% to 10% weight loss for cardiovascular benefits, and potentially assess for pharmacological or surgical intervention to assist in weight loss.2,4-6

While some weight loss medications (eg, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and lorcaserin) tend to have unfavorable AEs or mixed efficacy, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have provided new options.7-10 Lorcaserin, for example, was removed from the market in 2020 due to its association with cancer risks.11 The GLP-1RAs liraglutide and semaglutide received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for weight loss in 2014 and 2021, respectively.12,13 GLP-1RAs have shown the greatest efficacy and benefits in reducing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c); they are the preferred agents for patients who qualify for pharmacologic intervention for weight loss, especially those with T2DM. However, these studies have not evaluated the long-term outcomes of using these medications for weight loss and may not reflect the veteran population.14,15

At Veteran Health Indiana (VHI), clinicians may use several weight loss medications for patients to achieve 5% to 10% weight loss. The medications most often used include liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone. However, more research is needed to determine which weight loss medication is the most beneficial for veterans, particularly following FDA approval of GLP-1RAs. At VHI, phentermine/topiramate is the preferred first-line agent unless patients have contraindications for use, in which case naltrexone/bupropion is recommended. These are considered first-line due to their ease of use in pill form, lower cost, and comparable weight loss to the GLP-1 medication class.2 However, for patients with prediabetes, T2DM, BMI > 40, or BMI > 35 with specific comorbid conditions, liraglutide is preferred because of its beneficial effects for both weight loss and blood glucose control.2

This study aimed to expand on the 2021 Hood and colleagues study that examined total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage of baseline weight in patients with obesity at 3, 6, 12, and > 12 months of pharmacologic therapy by extending the time frame to 48 months.16 This study excluded semaglutide because few patients were prescribed the medication for weight loss during the study.

METHODS

We conducted a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed weight loss medications at VHI. A patient list was generated based on prescription fills from June 1, 2017, to July 31, 2021. Data were obtained from the Computerized Patient Record System; patients were not contacted. This study was approved by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and VHI Research and Development Committee.

At the time of this study, liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone were available at VHI for patients who met the clinical criteria for use. All patients must have been enrolled in dietary and lifestyle management programs, including the VA MOVE! program, to be approved for these medications. After the MOVE! orientation, patients could participate in group or individual 12-week programs that included weigh-ins, goal-setting strategies, meal planning, and habit modification support. If patients could not meet in person, phone and other telehealth opportunities were available.

Patients were included in the study if they were aged ≥ 18 years, received a prescription for any of the 5 available medications for weight loss during the enrollment period, and were on the medication for ≥ 6 consecutive months. Patients were excluded if they received a prescription, were treated outside the VA system, or were pregnant. The primary indication for the included medication was not weight loss; the primary indication for the GLP-1RA was T2DM, or the weight loss was attributed to another disease. Adherence was not a measured outcome of this study; if patients were filling the medication, it was assumed they were taking it. Data were collected for each instance of medication use; as a result, a few patients were included more than once. Data collection for a failed medication ended when failure was documented. New data points began when new medication was prescribed; all data were per medication, not per patient. This allowed us to account for medication failure and provide accurate weight loss results based on medication choice within VHI.

Primary outcomes included total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage ofbaseline weight during the study period at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of therapy. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of patients who lost 5% to 10% of their body weight from baseline; the percentage of patients who maintained ≥ 5% weight loss from baseline to 12, 24, 36, and 48 months if maintained on medication for that duration; duration of medication treatment in weeks; medication discontinuation rate; reason for medication discontinuation; enrollment in the MOVE! clinic and the time enrolled; percentage of patients with a BMI of 18 to 24.9 at the end of the study; and change in HbA1c at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months.

Demographic data included race, age, sex, baseline weight, height, baseline BMI, and comorbid conditions (collected based on the most recent primary care clinical note before initiating medication). Medication data collected included medications used to manage comorbidities. Data related to weight management medication included prescribing clinic, maintenance dose of medication, duration of medication during the study period, the reason for medication discontinuation, or bariatric surgery intervention if applicable.

Basic descriptive statistics were used to characterize study participants. For continuous data, analysis of variance tests were used; if those results were not normal, then nonparametric tests were used, followed by pairwise tests between medication groups if the overall test was significant using the Fisher significant differences test. For nominal data, χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used. For comparisons of primary and secondary outcomes, if the analyses needed to include adjustment for confounding variables, analysis of covariance was used for continuous data. A 2-sided 5% significance level was used for all tests.

RESULTS

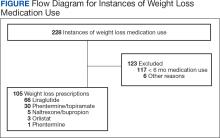

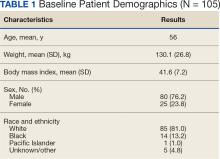

A total of 228 instances of medication use were identified based on prescription fills; 123 did not meet inclusion criteria (117 for < 6 consecutive months of medication use) (Figure). The study included 105 participants with a mean age of 56 years; 80 were male (76.2%), and 85 identified as White race (81.0%). Mean (SD) weight was 130.1 kg (26.8) and BMI was 41.6 (7.2). The most common comorbid disease states among patients included hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and T2DM (Table 1). The baseline characteristics were comparable to those of Hood and colleagues.16

Most patients at VHI started on liraglutide (63%) or phentermine/topiramate (28%). For primary and secondary outcomes, statistics were calculated to determine whether the results were statistically significant for comparing the liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate subgroups. Sample sizes were too small for statistical analysis for bupropion/naltrexone, phentermine, and orlistat.

Primary Outcomes

The mean (SD) weight of participants dropped 8.1% from 130.1 kg to 119.5 kg over the patient-specific duration of weight management medication therapy for an absolute difference of 10.6 kg (9.7). Duration of individual medication use varied from 6 to 48 months. Weight loss was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. Patient weight was not recorded after the medication was discontinued.

When classified by medication choice, the mean change in weight over the duration of the study was −23.9 kg for 2 patients using orlistat, −10.2 kg for 46 patients using liraglutide, −11.0 kg for 25 patients using phentermine/topiramate, -7.4 kg for 1 patient using phentermine, and -13.0 kg for 4 patients using naltrexone/bupropion. Patients without a weight documented at the end of their therapy or at the conclusion of the data collection period were not included in the total weight loss at the end of therapy. There were 78 documented instances of weight loss at the end of therapy (Table 2).

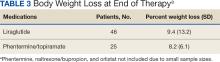

Body weight loss percentage was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. The mean (SD) body weight loss percentage over the duration of the study was 9.2% (11.2). When classified by medication choice, the mean percentage of body weight loss was 16.8% for 2 patients using orlistat, 9.4% for 46 patients using liraglutide, 8.2% for 25 patients using phentermine/topiramate, 6.0% for 1 patient using phentermine alone, and 10.6% for 4 patients using naltrexone/bupropion (Table 3).

Secondary Outcomes

While none of the secondary outcomes were statistically significant, the results of this study suggest that both medications may contribute to weight loss in many patients included in this study. Almost two-thirds of the included patients analyzed lost ≥ 5% of weight from baseline while taking weight management medication. Sixty-six patients (63%) lost ≥ 5% of body weight at any time during the data collection period. When stratified by liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate, 41 patients (63%) taking liraglutide and 20 patients (67%) taking phentermine/topiramate lost ≥ 5% of weight from baseline. Of the 66 patients who lost ≥ 5% of body weight from baseline, 36 (55%) lost ≥ 10% of body weight from baseline at any time during the data collection period.

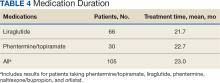

The mean (SD) duration for weight management medication use was 23 months (14.9). Phentermine/topiramate was tolerated longer than liraglutide: 22.7 months vs 21.7 months, respectively (Table 4).

The average overall documented medication discontinuation rate was 35.2%. Reasons for discontinuation included 21 patient-elected discontinuations, 8 patients no longer met criteria for use, 4 medications were no longer indicated, and 4 patients experienced AEs. It is unknown whether weight management medication was discontinued or not in 18 patients (17.2%).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the use and outcomes of weight loss medications over a longer period (up to 48 months) than what was previously studied among patients at VHI (12 months). The study aimed to better understand the long-term effect of weight loss medications, determine which medication had better long-term outcomes, and examine the reasons for medication discontinuation.

The results of this study displayed some similarities and differences compared with the Hood and colleagues study.16 Both yielded similar results for 5% of body weight loss and 10% of body weight loss. The largest difference was mean weight loss over the study period. In this study, patients lost a mean 10.6 kg over the course of weight loss medication use compared to 15.8 kg found by Hood and colleagues.16 A reason patients in the current study lost less weight overall could be the difference in time frames. The current study encompassed the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning fewer overall in-person patient appointments, which led to patients being lost to follow-up, missing weigh-ins during the time period, and gaps in care. For some patients, the pandemic possibly contributed to depression, missed medication doses, and a more sedentary lifestyle, leading to more weight gain.17 Telemedicine services at VHI expanded during the pandemic in an attempt to increase patient monitoring and counseling. It is unclear whether this expansion was enough to replace the in-person contact necessary to promote a healthy lifestyle.

VA pharmacists now care for patients through telehealth and are more involved in weight loss management. Since the conclusion of the Hood and colleagues study and start of this research, 2 pharmacists at VHI have been assigned to follow patients for obesity management to help with adherence to medication and lifestyle changes, management of AEs, dispense logistics, interventions for medications that may cause weight gain, and case management of glycemic control and weight loss with GLP-1RAs. Care management by pharmacists at VHI helps improve the logistics of titratable orders and save money by improving the use of high-cost items like GLP-1RAs. VA clinical pharmacy practitioners already monitor GLP-1RAs for patients with T2DM, so they are prepared to educate and assist patients with these medications.

It is important to continue developing a standardized process for weight loss medication management across the VA to improve the quality of patient care and optimize prescription outcomes. VA facilities differ in how weight loss management care is delivered and the level at which pharmacists are involved. Given the high rate of obesity among patients at the VA, the advent of new prescription options for weight loss, and the high cost associated with these medications, there has been increased attention to obesity care. Some Veterans Integrated Service Networks are forming a weight management community of practice groups to create standard operating procedures and algorithms to standardize care. Developing consistent processes is necessary to improve weight loss and patient care for veterans regardless where they receive treatment.

Limitations

The data used in this study were dependent on clinician documentation. Because of a lack of documentation in many instances, it was difficult to determine the full efficacy of the medications studied due to missing weight recordings. The lack of documentation made it difficult to determine whether patients were enrolled and active in the MOVE! program. It is required that patients enroll in MOVE! to obtain medications, but many did not have any follow-up MOVE! visits after initially obtaining their weight loss medication.

In this study, differences in the outcomes of patients with and without T2DM were not compared. It is the VA standard of care to prefer liraglutide over phentermine/topiramate in patients with T2DM or prediabetes.2 This makes it difficult to assess whether phentermine/topiramate or liraglutide is more effective for weight loss in patients with T2DM. Weight gain after the discontinuation of weight loss medications was not assessed. Collecting this data may help determine whether a certain weight loss medication is less likely to cause rebound weight gain when discontinued.

Other limitations to this study consisted of excluding patients who discontinued therapy within 6 months, small sample sizes on some medications, and lack of data on adherence. Adherence was based on medication refills, which means that if a patient refilled the medication, it was assumed they were taking it. This is not always the case, and while accurate data on adherence is difficult to gather, it can impact how results may be interpreted. These additional limitations make it difficult to accurately determine the efficacy of the medications in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found similar outcomes to what has been observed in larger clinical trials regarding weight loss medications. Nevertheless, there was a lack of accurate clinical documentation for most patients, which limits the conclusions. This lack of documentation potentially led to inaccurate results. It revealed that many patients at VHI did not uniformly receive consistent follow-up after starting a weight loss medication during the study period. With more standardized processes implemented at VA facilities, increased pharmacist involvement in weight loss medication management, and increased use of established telehealth services, patients could have the opportunity for closer follow-up that may lead to better weight loss outcomes. With these changes, there is more reason for additional studies to be conducted to assess follow-up, medication management, and weight loss overall.

1. Overweight & obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 21, 2023. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/index.html

2. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs. The Management of Adult Overweight and Obesity Working Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adult Overweight and Obesity. Updated July 2020. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

3. Health effects of overweight and obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 24, 2022. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/effects/index.html

4. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985-3023. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004

5. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-362. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3415

6. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 3. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes and associated comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S39-S45. doi:10.2337/dc22-S003

7. Phentermine and topiramate extended-release. Package insert. Vivus, Inc; 2012. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://qsymia.com/patient/include/media/pdf/prescribing-information.pdf

8. Naltrexone and bupropion extended-release. Package insert. Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc; 2014. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://contrave.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Contrave-label-113023.pdf

9. Orlistat. Package insert. Roche Laboratories, Inc; 2009. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020766s026lbl.pdf

10. Lorcaserin. Package insert. Arena Pharmaceuticals; 2012. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022529lbl.pdf

11. FDA requests the withdrawal of the weight-loss drug Belviq, Belviq XR (lorcaserin) from the market. News release. US Food & Drug Administration. February 13, 2020. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requests-withdrawal-weight-loss-drug-belviq-belviq-xr-lorcaserin-market

12. Saxenda Injection (Liraglutide [rDNA origin]). Novo Nordisk, Inc. October 1, 2015. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/206321Orig1s000TOC.cfm

13. FDA approves new drug treatment for chronic weight management, first since 2014. News release. US Food & Drug Administration. June 4, 2021. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-treatment-chronic-weight-management-first-2014

14. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. New Engl J Med. 2015;373:11-22. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411892

15. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New Engl J Med 2021;384:989-1002. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

16. Hood SR, Berkeley AW, Moore EA. Evaluation of pharmacologic interventions for weight management in a veteran population. Fed Pract. 2021;38(5):220-226. doi:10.12788/fp.0117

17. Melamed OC, Selby P, Taylor VH. Mental health and obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Obes Rep. 2022;11(1):23-31. doi:10.1007/s13679-021-00466-6

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9 as overweight and those with a BMI > 30 as obese (obesity classes: I, BMI 30 to 34.9; II, BMI 35 to 39.9; and III, BMI ≥ 40).1 In 2011, the CDC estimated that 27.4% of adults in the United States were obese; less than a decade later, that number increased to 31.9%.1 In that same period, the percentage of adults in Indiana classified as obese increased from 30.8% to 36.8%.1 About 1 in 14 individuals in the US have class III obesity and 86% of veterans are either overweight or obese.2

High medical expenses can likely be attributed to the long-term health consequences of obesity. Compared to those with a healthy weight, individuals who are overweight or obese are at an increased risk for high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, high triglyceride levels, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, cancer, mental health disorders, body pain, low quality of life, and death.3 Many of these conditions lead to increased health care needs, medication needs, hospitalizations, and overall health care system use.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of obesity have been produced by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society; the Endocrine Society; the American Diabetes Association; and the US Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Defense. Each follows a general algorithm to manage and prevent adverse effects (AEs) related to obesity. General practice is to assess a patient for elevated BMI (> 25), implement intense lifestyle modifications including calorie restriction and exercise, reassess for a maintained 5% to 10% weight loss for cardiovascular benefits, and potentially assess for pharmacological or surgical intervention to assist in weight loss.2,4-6

While some weight loss medications (eg, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and lorcaserin) tend to have unfavorable AEs or mixed efficacy, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have provided new options.7-10 Lorcaserin, for example, was removed from the market in 2020 due to its association with cancer risks.11 The GLP-1RAs liraglutide and semaglutide received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for weight loss in 2014 and 2021, respectively.12,13 GLP-1RAs have shown the greatest efficacy and benefits in reducing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c); they are the preferred agents for patients who qualify for pharmacologic intervention for weight loss, especially those with T2DM. However, these studies have not evaluated the long-term outcomes of using these medications for weight loss and may not reflect the veteran population.14,15

At Veteran Health Indiana (VHI), clinicians may use several weight loss medications for patients to achieve 5% to 10% weight loss. The medications most often used include liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone. However, more research is needed to determine which weight loss medication is the most beneficial for veterans, particularly following FDA approval of GLP-1RAs. At VHI, phentermine/topiramate is the preferred first-line agent unless patients have contraindications for use, in which case naltrexone/bupropion is recommended. These are considered first-line due to their ease of use in pill form, lower cost, and comparable weight loss to the GLP-1 medication class.2 However, for patients with prediabetes, T2DM, BMI > 40, or BMI > 35 with specific comorbid conditions, liraglutide is preferred because of its beneficial effects for both weight loss and blood glucose control.2

This study aimed to expand on the 2021 Hood and colleagues study that examined total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage of baseline weight in patients with obesity at 3, 6, 12, and > 12 months of pharmacologic therapy by extending the time frame to 48 months.16 This study excluded semaglutide because few patients were prescribed the medication for weight loss during the study.

METHODS

We conducted a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed weight loss medications at VHI. A patient list was generated based on prescription fills from June 1, 2017, to July 31, 2021. Data were obtained from the Computerized Patient Record System; patients were not contacted. This study was approved by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and VHI Research and Development Committee.

At the time of this study, liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone were available at VHI for patients who met the clinical criteria for use. All patients must have been enrolled in dietary and lifestyle management programs, including the VA MOVE! program, to be approved for these medications. After the MOVE! orientation, patients could participate in group or individual 12-week programs that included weigh-ins, goal-setting strategies, meal planning, and habit modification support. If patients could not meet in person, phone and other telehealth opportunities were available.

Patients were included in the study if they were aged ≥ 18 years, received a prescription for any of the 5 available medications for weight loss during the enrollment period, and were on the medication for ≥ 6 consecutive months. Patients were excluded if they received a prescription, were treated outside the VA system, or were pregnant. The primary indication for the included medication was not weight loss; the primary indication for the GLP-1RA was T2DM, or the weight loss was attributed to another disease. Adherence was not a measured outcome of this study; if patients were filling the medication, it was assumed they were taking it. Data were collected for each instance of medication use; as a result, a few patients were included more than once. Data collection for a failed medication ended when failure was documented. New data points began when new medication was prescribed; all data were per medication, not per patient. This allowed us to account for medication failure and provide accurate weight loss results based on medication choice within VHI.

Primary outcomes included total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage ofbaseline weight during the study period at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of therapy. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of patients who lost 5% to 10% of their body weight from baseline; the percentage of patients who maintained ≥ 5% weight loss from baseline to 12, 24, 36, and 48 months if maintained on medication for that duration; duration of medication treatment in weeks; medication discontinuation rate; reason for medication discontinuation; enrollment in the MOVE! clinic and the time enrolled; percentage of patients with a BMI of 18 to 24.9 at the end of the study; and change in HbA1c at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months.

Demographic data included race, age, sex, baseline weight, height, baseline BMI, and comorbid conditions (collected based on the most recent primary care clinical note before initiating medication). Medication data collected included medications used to manage comorbidities. Data related to weight management medication included prescribing clinic, maintenance dose of medication, duration of medication during the study period, the reason for medication discontinuation, or bariatric surgery intervention if applicable.

Basic descriptive statistics were used to characterize study participants. For continuous data, analysis of variance tests were used; if those results were not normal, then nonparametric tests were used, followed by pairwise tests between medication groups if the overall test was significant using the Fisher significant differences test. For nominal data, χ2 or Fisher exact tests were used. For comparisons of primary and secondary outcomes, if the analyses needed to include adjustment for confounding variables, analysis of covariance was used for continuous data. A 2-sided 5% significance level was used for all tests.

RESULTS

A total of 228 instances of medication use were identified based on prescription fills; 123 did not meet inclusion criteria (117 for < 6 consecutive months of medication use) (Figure). The study included 105 participants with a mean age of 56 years; 80 were male (76.2%), and 85 identified as White race (81.0%). Mean (SD) weight was 130.1 kg (26.8) and BMI was 41.6 (7.2). The most common comorbid disease states among patients included hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and T2DM (Table 1). The baseline characteristics were comparable to those of Hood and colleagues.16

Most patients at VHI started on liraglutide (63%) or phentermine/topiramate (28%). For primary and secondary outcomes, statistics were calculated to determine whether the results were statistically significant for comparing the liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate subgroups. Sample sizes were too small for statistical analysis for bupropion/naltrexone, phentermine, and orlistat.

Primary Outcomes

The mean (SD) weight of participants dropped 8.1% from 130.1 kg to 119.5 kg over the patient-specific duration of weight management medication therapy for an absolute difference of 10.6 kg (9.7). Duration of individual medication use varied from 6 to 48 months. Weight loss was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. Patient weight was not recorded after the medication was discontinued.

When classified by medication choice, the mean change in weight over the duration of the study was −23.9 kg for 2 patients using orlistat, −10.2 kg for 46 patients using liraglutide, −11.0 kg for 25 patients using phentermine/topiramate, -7.4 kg for 1 patient using phentermine, and -13.0 kg for 4 patients using naltrexone/bupropion. Patients without a weight documented at the end of their therapy or at the conclusion of the data collection period were not included in the total weight loss at the end of therapy. There were 78 documented instances of weight loss at the end of therapy (Table 2).

Body weight loss percentage was recorded at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 months of weight management therapy. The mean (SD) body weight loss percentage over the duration of the study was 9.2% (11.2). When classified by medication choice, the mean percentage of body weight loss was 16.8% for 2 patients using orlistat, 9.4% for 46 patients using liraglutide, 8.2% for 25 patients using phentermine/topiramate, 6.0% for 1 patient using phentermine alone, and 10.6% for 4 patients using naltrexone/bupropion (Table 3).

Secondary Outcomes

While none of the secondary outcomes were statistically significant, the results of this study suggest that both medications may contribute to weight loss in many patients included in this study. Almost two-thirds of the included patients analyzed lost ≥ 5% of weight from baseline while taking weight management medication. Sixty-six patients (63%) lost ≥ 5% of body weight at any time during the data collection period. When stratified by liraglutide and phentermine/topiramate, 41 patients (63%) taking liraglutide and 20 patients (67%) taking phentermine/topiramate lost ≥ 5% of weight from baseline. Of the 66 patients who lost ≥ 5% of body weight from baseline, 36 (55%) lost ≥ 10% of body weight from baseline at any time during the data collection period.

The mean (SD) duration for weight management medication use was 23 months (14.9). Phentermine/topiramate was tolerated longer than liraglutide: 22.7 months vs 21.7 months, respectively (Table 4).

The average overall documented medication discontinuation rate was 35.2%. Reasons for discontinuation included 21 patient-elected discontinuations, 8 patients no longer met criteria for use, 4 medications were no longer indicated, and 4 patients experienced AEs. It is unknown whether weight management medication was discontinued or not in 18 patients (17.2%).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the use and outcomes of weight loss medications over a longer period (up to 48 months) than what was previously studied among patients at VHI (12 months). The study aimed to better understand the long-term effect of weight loss medications, determine which medication had better long-term outcomes, and examine the reasons for medication discontinuation.

The results of this study displayed some similarities and differences compared with the Hood and colleagues study.16 Both yielded similar results for 5% of body weight loss and 10% of body weight loss. The largest difference was mean weight loss over the study period. In this study, patients lost a mean 10.6 kg over the course of weight loss medication use compared to 15.8 kg found by Hood and colleagues.16 A reason patients in the current study lost less weight overall could be the difference in time frames. The current study encompassed the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning fewer overall in-person patient appointments, which led to patients being lost to follow-up, missing weigh-ins during the time period, and gaps in care. For some patients, the pandemic possibly contributed to depression, missed medication doses, and a more sedentary lifestyle, leading to more weight gain.17 Telemedicine services at VHI expanded during the pandemic in an attempt to increase patient monitoring and counseling. It is unclear whether this expansion was enough to replace the in-person contact necessary to promote a healthy lifestyle.

VA pharmacists now care for patients through telehealth and are more involved in weight loss management. Since the conclusion of the Hood and colleagues study and start of this research, 2 pharmacists at VHI have been assigned to follow patients for obesity management to help with adherence to medication and lifestyle changes, management of AEs, dispense logistics, interventions for medications that may cause weight gain, and case management of glycemic control and weight loss with GLP-1RAs. Care management by pharmacists at VHI helps improve the logistics of titratable orders and save money by improving the use of high-cost items like GLP-1RAs. VA clinical pharmacy practitioners already monitor GLP-1RAs for patients with T2DM, so they are prepared to educate and assist patients with these medications.

It is important to continue developing a standardized process for weight loss medication management across the VA to improve the quality of patient care and optimize prescription outcomes. VA facilities differ in how weight loss management care is delivered and the level at which pharmacists are involved. Given the high rate of obesity among patients at the VA, the advent of new prescription options for weight loss, and the high cost associated with these medications, there has been increased attention to obesity care. Some Veterans Integrated Service Networks are forming a weight management community of practice groups to create standard operating procedures and algorithms to standardize care. Developing consistent processes is necessary to improve weight loss and patient care for veterans regardless where they receive treatment.

Limitations

The data used in this study were dependent on clinician documentation. Because of a lack of documentation in many instances, it was difficult to determine the full efficacy of the medications studied due to missing weight recordings. The lack of documentation made it difficult to determine whether patients were enrolled and active in the MOVE! program. It is required that patients enroll in MOVE! to obtain medications, but many did not have any follow-up MOVE! visits after initially obtaining their weight loss medication.

In this study, differences in the outcomes of patients with and without T2DM were not compared. It is the VA standard of care to prefer liraglutide over phentermine/topiramate in patients with T2DM or prediabetes.2 This makes it difficult to assess whether phentermine/topiramate or liraglutide is more effective for weight loss in patients with T2DM. Weight gain after the discontinuation of weight loss medications was not assessed. Collecting this data may help determine whether a certain weight loss medication is less likely to cause rebound weight gain when discontinued.

Other limitations to this study consisted of excluding patients who discontinued therapy within 6 months, small sample sizes on some medications, and lack of data on adherence. Adherence was based on medication refills, which means that if a patient refilled the medication, it was assumed they were taking it. This is not always the case, and while accurate data on adherence is difficult to gather, it can impact how results may be interpreted. These additional limitations make it difficult to accurately determine the efficacy of the medications in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found similar outcomes to what has been observed in larger clinical trials regarding weight loss medications. Nevertheless, there was a lack of accurate clinical documentation for most patients, which limits the conclusions. This lack of documentation potentially led to inaccurate results. It revealed that many patients at VHI did not uniformly receive consistent follow-up after starting a weight loss medication during the study period. With more standardized processes implemented at VA facilities, increased pharmacist involvement in weight loss medication management, and increased use of established telehealth services, patients could have the opportunity for closer follow-up that may lead to better weight loss outcomes. With these changes, there is more reason for additional studies to be conducted to assess follow-up, medication management, and weight loss overall.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9 as overweight and those with a BMI > 30 as obese (obesity classes: I, BMI 30 to 34.9; II, BMI 35 to 39.9; and III, BMI ≥ 40).1 In 2011, the CDC estimated that 27.4% of adults in the United States were obese; less than a decade later, that number increased to 31.9%.1 In that same period, the percentage of adults in Indiana classified as obese increased from 30.8% to 36.8%.1 About 1 in 14 individuals in the US have class III obesity and 86% of veterans are either overweight or obese.2

High medical expenses can likely be attributed to the long-term health consequences of obesity. Compared to those with a healthy weight, individuals who are overweight or obese are at an increased risk for high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, high triglyceride levels, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, cancer, mental health disorders, body pain, low quality of life, and death.3 Many of these conditions lead to increased health care needs, medication needs, hospitalizations, and overall health care system use.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of obesity have been produced by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society; the Endocrine Society; the American Diabetes Association; and the US Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Defense. Each follows a general algorithm to manage and prevent adverse effects (AEs) related to obesity. General practice is to assess a patient for elevated BMI (> 25), implement intense lifestyle modifications including calorie restriction and exercise, reassess for a maintained 5% to 10% weight loss for cardiovascular benefits, and potentially assess for pharmacological or surgical intervention to assist in weight loss.2,4-6

While some weight loss medications (eg, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and lorcaserin) tend to have unfavorable AEs or mixed efficacy, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have provided new options.7-10 Lorcaserin, for example, was removed from the market in 2020 due to its association with cancer risks.11 The GLP-1RAs liraglutide and semaglutide received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for weight loss in 2014 and 2021, respectively.12,13 GLP-1RAs have shown the greatest efficacy and benefits in reducing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c); they are the preferred agents for patients who qualify for pharmacologic intervention for weight loss, especially those with T2DM. However, these studies have not evaluated the long-term outcomes of using these medications for weight loss and may not reflect the veteran population.14,15

At Veteran Health Indiana (VHI), clinicians may use several weight loss medications for patients to achieve 5% to 10% weight loss. The medications most often used include liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone. However, more research is needed to determine which weight loss medication is the most beneficial for veterans, particularly following FDA approval of GLP-1RAs. At VHI, phentermine/topiramate is the preferred first-line agent unless patients have contraindications for use, in which case naltrexone/bupropion is recommended. These are considered first-line due to their ease of use in pill form, lower cost, and comparable weight loss to the GLP-1 medication class.2 However, for patients with prediabetes, T2DM, BMI > 40, or BMI > 35 with specific comorbid conditions, liraglutide is preferred because of its beneficial effects for both weight loss and blood glucose control.2

This study aimed to expand on the 2021 Hood and colleagues study that examined total weight loss and weight loss as a percentage of baseline weight in patients with obesity at 3, 6, 12, and > 12 months of pharmacologic therapy by extending the time frame to 48 months.16 This study excluded semaglutide because few patients were prescribed the medication for weight loss during the study.

METHODS

We conducted a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed weight loss medications at VHI. A patient list was generated based on prescription fills from June 1, 2017, to July 31, 2021. Data were obtained from the Computerized Patient Record System; patients were not contacted. This study was approved by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and VHI Research and Development Committee.

At the time of this study, liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine alone were available at VHI for patients who met the clinical criteria for use. All patients must have been enrolled in dietary and lifestyle management programs, including the VA MOVE! program, to be approved for these medications. After the MOVE! orientation, patients could participate in group or individual 12-week programs that included weigh-ins, goal-setting strategies, meal planning, and habit modification support. If patients could not meet in person, phone and other telehealth opportunities were available.