User login

Longstanding rash

The patient was given a diagnosis of widespread tinea corporis. This diagnosis may not fit with the common paradigm of tinea as thin, scaly annular patches, often known as ringworm. However, a skin scraping was performed on the red scaly patches, and the diagnosis was confirmed.

A skin scraping is a simple procedure that takes minutes to yield actionable information. A scalpel blade is used in a scraping motion and skin flakes are caught on a slide as they fall from the skin. (Another glass slide can be used in place of the scalpel, which is slightly less frightening for children.) The sample is then covered with 1 to 2 drops of potassium hydroxide (KOH), in 1 of various available formulations, and covered with a coverslip. Gently heating the slide, or simply waiting a few minutes, will allow the KOH to begin dissolving some keratinocyte membranes and stain any fungal walls light purple.

Hyphae, which may be linear (see Figure) or branched, will cross multiple cell membranes and are themselves about the thickness of a cell membrane. A high-powered view of hyphae should reveal nuclei and septa.

Skin biopsy, culture, and a skin scraping sent to an outside lab are all alternatives to the aforementioned approach but take days or weeks to yield a result. Fungal polymerase chain reaction is a novel diagnostic approach that can be both sensitive and specific, but still requires several days for results and incurs additional cost to the patient.

In this case, the diagnosis was made at the patient’s bedside and terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks was chosen as systemic therapy because of the extent of disease. At the follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient’s rash had completely cleared.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Liu D, Coloe S, Baird R, et al. Application of PCR to the identification of dermatophyte fungi. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:493-497.

The patient was given a diagnosis of widespread tinea corporis. This diagnosis may not fit with the common paradigm of tinea as thin, scaly annular patches, often known as ringworm. However, a skin scraping was performed on the red scaly patches, and the diagnosis was confirmed.

A skin scraping is a simple procedure that takes minutes to yield actionable information. A scalpel blade is used in a scraping motion and skin flakes are caught on a slide as they fall from the skin. (Another glass slide can be used in place of the scalpel, which is slightly less frightening for children.) The sample is then covered with 1 to 2 drops of potassium hydroxide (KOH), in 1 of various available formulations, and covered with a coverslip. Gently heating the slide, or simply waiting a few minutes, will allow the KOH to begin dissolving some keratinocyte membranes and stain any fungal walls light purple.

Hyphae, which may be linear (see Figure) or branched, will cross multiple cell membranes and are themselves about the thickness of a cell membrane. A high-powered view of hyphae should reveal nuclei and septa.

Skin biopsy, culture, and a skin scraping sent to an outside lab are all alternatives to the aforementioned approach but take days or weeks to yield a result. Fungal polymerase chain reaction is a novel diagnostic approach that can be both sensitive and specific, but still requires several days for results and incurs additional cost to the patient.

In this case, the diagnosis was made at the patient’s bedside and terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks was chosen as systemic therapy because of the extent of disease. At the follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient’s rash had completely cleared.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The patient was given a diagnosis of widespread tinea corporis. This diagnosis may not fit with the common paradigm of tinea as thin, scaly annular patches, often known as ringworm. However, a skin scraping was performed on the red scaly patches, and the diagnosis was confirmed.

A skin scraping is a simple procedure that takes minutes to yield actionable information. A scalpel blade is used in a scraping motion and skin flakes are caught on a slide as they fall from the skin. (Another glass slide can be used in place of the scalpel, which is slightly less frightening for children.) The sample is then covered with 1 to 2 drops of potassium hydroxide (KOH), in 1 of various available formulations, and covered with a coverslip. Gently heating the slide, or simply waiting a few minutes, will allow the KOH to begin dissolving some keratinocyte membranes and stain any fungal walls light purple.

Hyphae, which may be linear (see Figure) or branched, will cross multiple cell membranes and are themselves about the thickness of a cell membrane. A high-powered view of hyphae should reveal nuclei and septa.

Skin biopsy, culture, and a skin scraping sent to an outside lab are all alternatives to the aforementioned approach but take days or weeks to yield a result. Fungal polymerase chain reaction is a novel diagnostic approach that can be both sensitive and specific, but still requires several days for results and incurs additional cost to the patient.

In this case, the diagnosis was made at the patient’s bedside and terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks was chosen as systemic therapy because of the extent of disease. At the follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient’s rash had completely cleared.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Liu D, Coloe S, Baird R, et al. Application of PCR to the identification of dermatophyte fungi. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:493-497.

Liu D, Coloe S, Baird R, et al. Application of PCR to the identification of dermatophyte fungi. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:493-497.

Neck papules in a young man

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of early folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (FKN).

FKN, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI) and is the most common form of scarring alopecia in men of African descent. The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. Patients should lengthen their hair to at least a quarter of an inch to minimize this process. Military personnel may receive a waiver from standard grooming requirements. FKN may also occur as a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

For early disease, topical therapy with either clindamycin 1% lotion or chlorhexidine solution are acceptable options. Should these options and hair lengthening fail over 3 to 4 months, consider a 6- to 12-week course of doxycycline or minocycline 100 mg once or twice daily. Intralesional triamcinolone with 5 to 10 mg/mL injected into fixed papules every 4 to 8 weeks is another option to reduce scar formation. The most severe cases may require combination oral antibiotics, isotretinoin, or plastic surgery.

In this case, the patient grew out his hair and applied clindamycin 1% lotion twice daily for a year. As a result, he had no further disease.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of early folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (FKN).

FKN, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI) and is the most common form of scarring alopecia in men of African descent. The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. Patients should lengthen their hair to at least a quarter of an inch to minimize this process. Military personnel may receive a waiver from standard grooming requirements. FKN may also occur as a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

For early disease, topical therapy with either clindamycin 1% lotion or chlorhexidine solution are acceptable options. Should these options and hair lengthening fail over 3 to 4 months, consider a 6- to 12-week course of doxycycline or minocycline 100 mg once or twice daily. Intralesional triamcinolone with 5 to 10 mg/mL injected into fixed papules every 4 to 8 weeks is another option to reduce scar formation. The most severe cases may require combination oral antibiotics, isotretinoin, or plastic surgery.

In this case, the patient grew out his hair and applied clindamycin 1% lotion twice daily for a year. As a result, he had no further disease.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of early folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (FKN).

FKN, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI) and is the most common form of scarring alopecia in men of African descent. The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. Patients should lengthen their hair to at least a quarter of an inch to minimize this process. Military personnel may receive a waiver from standard grooming requirements. FKN may also occur as a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

For early disease, topical therapy with either clindamycin 1% lotion or chlorhexidine solution are acceptable options. Should these options and hair lengthening fail over 3 to 4 months, consider a 6- to 12-week course of doxycycline or minocycline 100 mg once or twice daily. Intralesional triamcinolone with 5 to 10 mg/mL injected into fixed papules every 4 to 8 weeks is another option to reduce scar formation. The most severe cases may require combination oral antibiotics, isotretinoin, or plastic surgery.

In this case, the patient grew out his hair and applied clindamycin 1% lotion twice daily for a year. As a result, he had no further disease.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

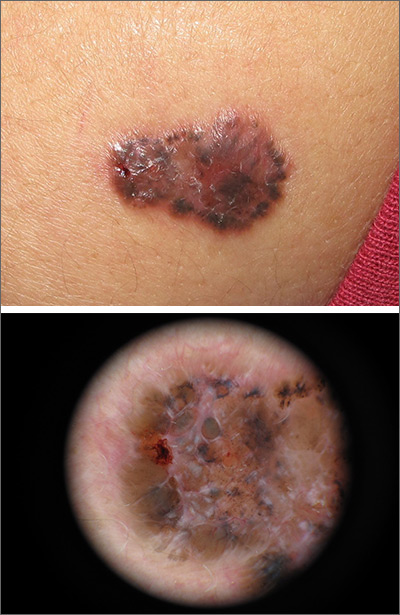

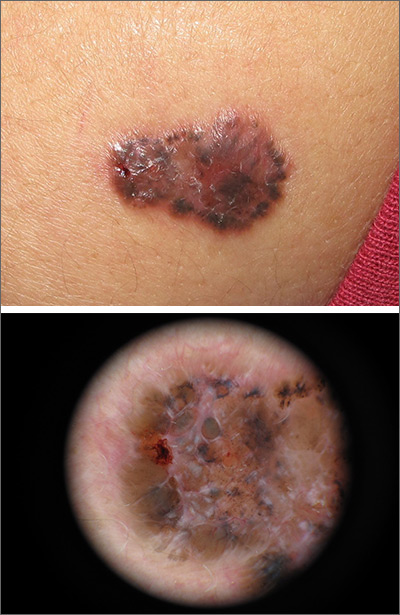

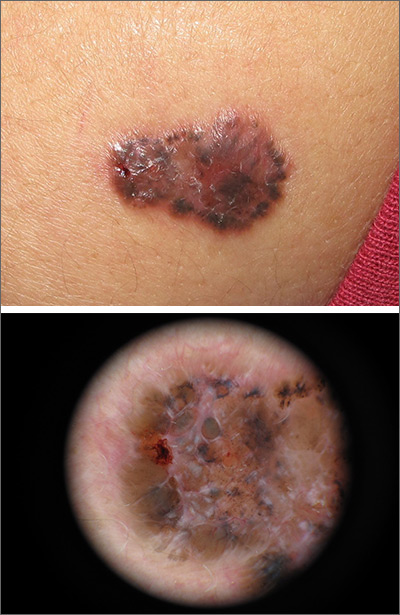

Growing brown and pink plaque

A shave biopsy of the lesion confirmed a nodular and pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC). In the United States, BCC is the most common cancer and accounts for 80% of all skin cancer diagnoses. BCC is also the most widespread cancer in White, Hispanic, and Asian patients and the second most common skin cancer in Black patients.

In all patients, BCC presents as a shiny growing macule, papule, or plaque, usually in areas of sun exposure. Much less is known about the role of UV exposure in skin of color because of the lack of high-quality studies in this population. Despite this, BCC in skin of color most often presents on the head and neck, as it does in non-Hispanic White patients. There is a correlation between lighter skin tones in Black patients and increased numbers of BCC diagnoses.

When assessing a suspicious skin lesion in skin of color, be on the lookout for the following visual cues. Pigmentation, clinically and on dermoscopy, is a more common feature of BCCs in non-White patients—occurring in more than half of all BCCs in skin of color.1 While pigmentation in a skin tumor may be mistaken for melanoma, the blue ovoid nests, brown dots in focus, and brown leaf-like areas on dermoscopy are BCC-specific clues that can alert the clinician to the diagnosis. In all patients, telangiectasias are another hallmark of BCC but may be the only feature in White patients and just one of many features in non-White patients.

In small data sets, there is no difference in tumor-related morbidity and prognosis between White and Black patients with BCC. Additionally, BCCs in White, Asian, and Hispanic patients have had no differences in preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs stages, and outcome.1

In this case, the patient underwent a complete excision with a 5-mm margin. She remained free of new or recurrent BCCs over the next 2 years, with surveillance exams twice a year.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

1. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526.

A shave biopsy of the lesion confirmed a nodular and pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC). In the United States, BCC is the most common cancer and accounts for 80% of all skin cancer diagnoses. BCC is also the most widespread cancer in White, Hispanic, and Asian patients and the second most common skin cancer in Black patients.

In all patients, BCC presents as a shiny growing macule, papule, or plaque, usually in areas of sun exposure. Much less is known about the role of UV exposure in skin of color because of the lack of high-quality studies in this population. Despite this, BCC in skin of color most often presents on the head and neck, as it does in non-Hispanic White patients. There is a correlation between lighter skin tones in Black patients and increased numbers of BCC diagnoses.

When assessing a suspicious skin lesion in skin of color, be on the lookout for the following visual cues. Pigmentation, clinically and on dermoscopy, is a more common feature of BCCs in non-White patients—occurring in more than half of all BCCs in skin of color.1 While pigmentation in a skin tumor may be mistaken for melanoma, the blue ovoid nests, brown dots in focus, and brown leaf-like areas on dermoscopy are BCC-specific clues that can alert the clinician to the diagnosis. In all patients, telangiectasias are another hallmark of BCC but may be the only feature in White patients and just one of many features in non-White patients.

In small data sets, there is no difference in tumor-related morbidity and prognosis between White and Black patients with BCC. Additionally, BCCs in White, Asian, and Hispanic patients have had no differences in preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs stages, and outcome.1

In this case, the patient underwent a complete excision with a 5-mm margin. She remained free of new or recurrent BCCs over the next 2 years, with surveillance exams twice a year.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

A shave biopsy of the lesion confirmed a nodular and pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC). In the United States, BCC is the most common cancer and accounts for 80% of all skin cancer diagnoses. BCC is also the most widespread cancer in White, Hispanic, and Asian patients and the second most common skin cancer in Black patients.

In all patients, BCC presents as a shiny growing macule, papule, or plaque, usually in areas of sun exposure. Much less is known about the role of UV exposure in skin of color because of the lack of high-quality studies in this population. Despite this, BCC in skin of color most often presents on the head and neck, as it does in non-Hispanic White patients. There is a correlation between lighter skin tones in Black patients and increased numbers of BCC diagnoses.

When assessing a suspicious skin lesion in skin of color, be on the lookout for the following visual cues. Pigmentation, clinically and on dermoscopy, is a more common feature of BCCs in non-White patients—occurring in more than half of all BCCs in skin of color.1 While pigmentation in a skin tumor may be mistaken for melanoma, the blue ovoid nests, brown dots in focus, and brown leaf-like areas on dermoscopy are BCC-specific clues that can alert the clinician to the diagnosis. In all patients, telangiectasias are another hallmark of BCC but may be the only feature in White patients and just one of many features in non-White patients.

In small data sets, there is no difference in tumor-related morbidity and prognosis between White and Black patients with BCC. Additionally, BCCs in White, Asian, and Hispanic patients have had no differences in preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs stages, and outcome.1

In this case, the patient underwent a complete excision with a 5-mm margin. She remained free of new or recurrent BCCs over the next 2 years, with surveillance exams twice a year.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

1. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526.

1. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526.

Generalized pustular eruption

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to a diagnosis of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized. The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%). Leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days. Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. (This patient was a case in point.)

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis. In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days. In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs. A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men. While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and pustular psoriasis. The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated. A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.

This patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared and only minimal residual erythema was noted. The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

This case was adapted from: Tolkachjov SN, Wetter DA, Sandefur BJ. Generalized pustular eruption. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:309-310,312.

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to a diagnosis of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized. The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%). Leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days. Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. (This patient was a case in point.)

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis. In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days. In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs. A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men. While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and pustular psoriasis. The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated. A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.

This patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared and only minimal residual erythema was noted. The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

This case was adapted from: Tolkachjov SN, Wetter DA, Sandefur BJ. Generalized pustular eruption. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:309-310,312.

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to a diagnosis of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized. The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%). Leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days. Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. (This patient was a case in point.)

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis. In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days. In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs. A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men. While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and pustular psoriasis. The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated. A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.

This patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared and only minimal residual erythema was noted. The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

This case was adapted from: Tolkachjov SN, Wetter DA, Sandefur BJ. Generalized pustular eruption. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:309-310,312.

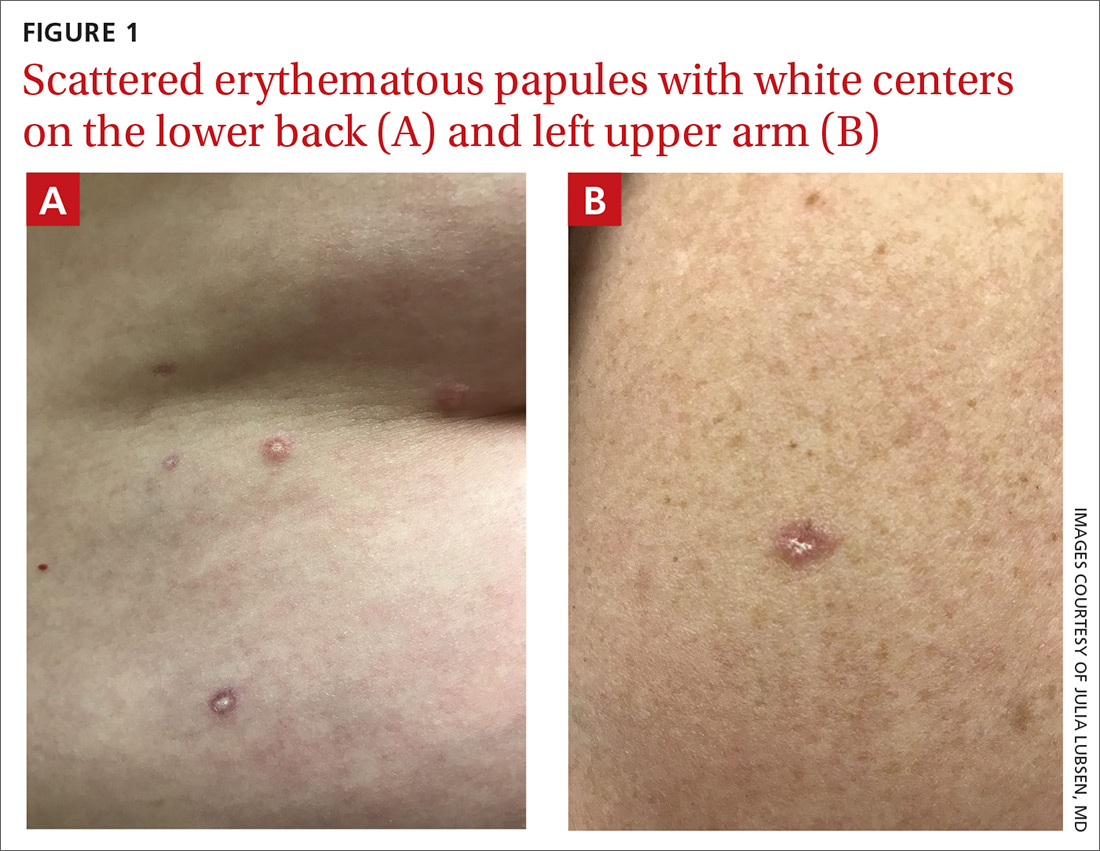

Worsening skin lesions but no diagnosis

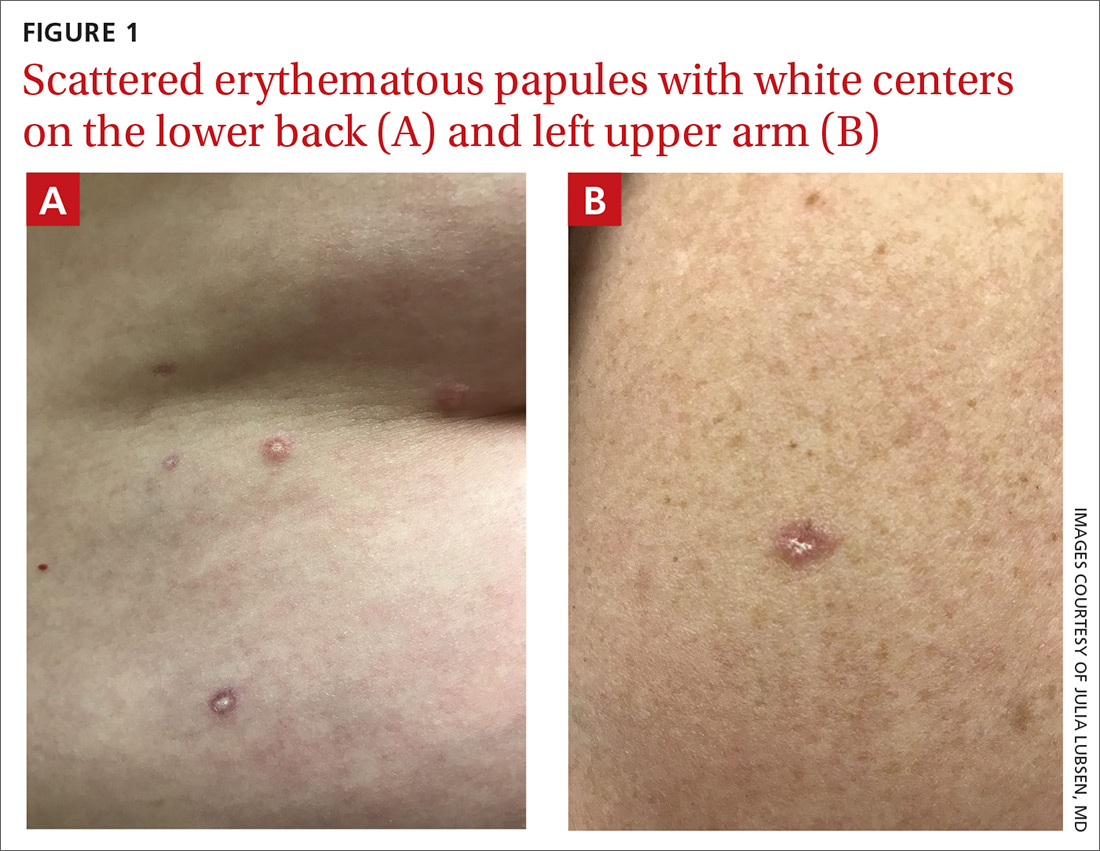

A 50-year-old woman presented to her family physician for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and an itchy rash. She said the rash had developed 2 years earlier and had gotten worse, with additional lesions emerging on her skin as time went on. She noted that other physicians had evaluated the rash but provided no clear diagnosis and had done no testing.

A physical exam revealed scattered erythematous papules with white centers on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 1). The patient’s medical history was significant for asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, urinary incontinence, and depression. Her medications included montelukast, inhaled fluticasone, albuterol, tolterodine, omeprazole, and fluoxetine.

The patient was prescribed nitrofurantoin, 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, to treat her UTI, and a punch biopsy was performed on one of the patient’s lesions to determine the cause of the rash.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophic papulosis

Pathology suggested a diagnosis of atrophic papulosis. A consultation with a dermatologist and additional biopsies confirmed the diagnosis. The biopsies showed wedge-shaped areas of superficial dermal sclerosis with thinning of the overlying epidermis. The superficial dermal vessels contained scattered, small thrombi at the periphery of the areas of sclerosis.

Atrophic papulosis (also known as Degos disease or Kölmeier-Degos disease) is a vasculopathy characterized by thrombotic occlusion of small arteries.1 Although rare—with fewer than 200 published case reports in the literature—it is likely underdiagnosed.1 Atrophic papulosis can be distinguished by hallmark skin findings, including 0.5- to 1-cm papular skin lesions with central porcelain-white atrophy and an erythematous, telangiectatic rim.1 It usually manifests between ages 20 to 50 but can occur in infants and children.1 The etiology is unknown, but case evidence suggests the condition is sometimes familial.1,2

Easy to confuse with common conditions

Clinical presentation of atrophic papulosis can vary, but evaluation should rule out systemic lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases.1 In addition, the lesions can easily be confused with other common conditions such as molluscum contagiosum or insect bites.

The hallmark finding of molluscum contagiosum is raised papules with central umbilication, whereas atrophic papulosis lesions are characterized by white centers. While insect bites typically disappear within weeks, atrophic papulosis lesions persist for years or are even lifelong.1

Is it benign or malignant?

Benign atrophic papulosis is limited to the skin.1 The probability of a patient having benign atrophic papulosis is about 70% at the onset of skin lesions and 97% after 7 years without other symptoms.2

Malignant atrophic papulosis—although less common—is systemic and life-threatening. About 30% of patients with atrophic papulosis develop lesions manifesting both on the skin and in internal organs.1,2 Systemic involvement can develop at any time, sometimes years after the appearance of skin lesions, but the risk declines over time.2 In a case series, systemic signs were shown to develop, on average, 1 year after skin lesions.2 Some evidence suggests a mortality rate of 50% within 2 to 3 years of the onset of systemic involvement, making regular follow-up necessary.1

Continue to: Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis...

Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis may have systemic involvement in multiple organ systems. Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement can cause bowel perforation. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement may put the patient at risk for stroke, intracranial bleeding, meningitis, and encephalitis.1,3 There can also be cardiopulmonary involvement that causes pleuritis and pericarditis.1 Ocular involvement can affect the eyelids, conjunctiva, retina, sclera, and choroid plexus.1 Renal involvement has been noted in a few cases.2

In a prospective, single-center cohort study of 39 patients with atrophic papulosis, systemic involvement (malignant atrophic papulosis) was reported in 29% (n = 11) of the patients.2 In these patients, involved organ systems included the GI tract (73%; n = 8), CNS (64%; n = 7), eye (18%; n = 2), heart (18%; n = 2), and lungs (9%; n = 1); 64% (n = 7) had multiorgan involvement. Mortality was reported in 73% of the patients with systemic disease.

Ongoing testing is required

For a patient presenting with atrophic papulosis, initial and follow-up visits should include evaluation for systemic manifestations through a full skin examination, fecal occult blood test, and ocular fundus examination.1,2 If the patient shows any symptoms that suggest systemic involvement, further testing is advised, including evaluation of renal function, colonoscopy, endoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, an echocardiogram, and chest computed tomography.

Because internal organ involvement in malignant atrophic papulosis can develop within years of (benign) cutaneous manifestations, regular follow-up is recommended.1 Research suggests evaluation of patients with benign atrophic papulosis every 6 months for the first 7 years after disease onset and then yearly between 7 and 10 years after onset.2

Treatment options are limited

Antiplatelet agents (aspirin, pentoxifylline, dipyridamole, and ticlodipine) and anticoagulants (heparin) have led to partial regression of skin lesions in case reports.1 Some lesions seem to disappear after treatment, but due to limited evidence, it is difficult to determine whether treatment leads to a reduction of future lesions.

When it comes to malignant atrophic papulosis, there is no uniformly effective treatment. Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants are often used as initial treatment, but efficacy has not been clearly demonstrated. In case reports, eculizumab and treprostinil have shown effectiveness in treating CNS involvement, but there are no uniform dosage recommendations.3,4

In this case, the patient had mild GI symptoms. A colonoscopy showed evidence of microscopic colitis, but there was no evidence of atrophic papulosis in the GI tract.

Additional laboratory work-up was ordered to evaluate for signs of organ involvement and to rule out any associated connective tissue disease or hypercoagulable state. Her results showed a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (29 mm/h) and a positive antinuclear antibodies assay (1:640, speckled pattern). She was referred to a rheumatologist, who found no evidence of a connective tissue disorder. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, and hypercoagulability work-up were all within normal limits. A complete eye exam was also normal.

The patient was started on aspirin 81 mg/d. Because she continued to develop new lesions, her dermatologist added pentoxifylline extended release and gradually increased the dose to 400 mg in the morning and 800 mg in the evening. About 4 years after onset of the rash, the patient showed no signs of systemic involvement, but her skin lesions were still present.

1. Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

2. Theodoridis A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, et al. Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease): systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:110-115.

3. Huang YC, Wang JD, Lee FY, et al. Pediatric malignant atrophic papulosis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(suppl 5):S481-S484.

4. Shapiro LS, Toledo-Garcia AE, Farrell JF. Effective treatment of malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) with treprostinil—early experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:52.

A 50-year-old woman presented to her family physician for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and an itchy rash. She said the rash had developed 2 years earlier and had gotten worse, with additional lesions emerging on her skin as time went on. She noted that other physicians had evaluated the rash but provided no clear diagnosis and had done no testing.

A physical exam revealed scattered erythematous papules with white centers on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 1). The patient’s medical history was significant for asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, urinary incontinence, and depression. Her medications included montelukast, inhaled fluticasone, albuterol, tolterodine, omeprazole, and fluoxetine.

The patient was prescribed nitrofurantoin, 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, to treat her UTI, and a punch biopsy was performed on one of the patient’s lesions to determine the cause of the rash.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophic papulosis

Pathology suggested a diagnosis of atrophic papulosis. A consultation with a dermatologist and additional biopsies confirmed the diagnosis. The biopsies showed wedge-shaped areas of superficial dermal sclerosis with thinning of the overlying epidermis. The superficial dermal vessels contained scattered, small thrombi at the periphery of the areas of sclerosis.

Atrophic papulosis (also known as Degos disease or Kölmeier-Degos disease) is a vasculopathy characterized by thrombotic occlusion of small arteries.1 Although rare—with fewer than 200 published case reports in the literature—it is likely underdiagnosed.1 Atrophic papulosis can be distinguished by hallmark skin findings, including 0.5- to 1-cm papular skin lesions with central porcelain-white atrophy and an erythematous, telangiectatic rim.1 It usually manifests between ages 20 to 50 but can occur in infants and children.1 The etiology is unknown, but case evidence suggests the condition is sometimes familial.1,2

Easy to confuse with common conditions

Clinical presentation of atrophic papulosis can vary, but evaluation should rule out systemic lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases.1 In addition, the lesions can easily be confused with other common conditions such as molluscum contagiosum or insect bites.

The hallmark finding of molluscum contagiosum is raised papules with central umbilication, whereas atrophic papulosis lesions are characterized by white centers. While insect bites typically disappear within weeks, atrophic papulosis lesions persist for years or are even lifelong.1

Is it benign or malignant?

Benign atrophic papulosis is limited to the skin.1 The probability of a patient having benign atrophic papulosis is about 70% at the onset of skin lesions and 97% after 7 years without other symptoms.2

Malignant atrophic papulosis—although less common—is systemic and life-threatening. About 30% of patients with atrophic papulosis develop lesions manifesting both on the skin and in internal organs.1,2 Systemic involvement can develop at any time, sometimes years after the appearance of skin lesions, but the risk declines over time.2 In a case series, systemic signs were shown to develop, on average, 1 year after skin lesions.2 Some evidence suggests a mortality rate of 50% within 2 to 3 years of the onset of systemic involvement, making regular follow-up necessary.1

Continue to: Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis...

Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis may have systemic involvement in multiple organ systems. Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement can cause bowel perforation. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement may put the patient at risk for stroke, intracranial bleeding, meningitis, and encephalitis.1,3 There can also be cardiopulmonary involvement that causes pleuritis and pericarditis.1 Ocular involvement can affect the eyelids, conjunctiva, retina, sclera, and choroid plexus.1 Renal involvement has been noted in a few cases.2

In a prospective, single-center cohort study of 39 patients with atrophic papulosis, systemic involvement (malignant atrophic papulosis) was reported in 29% (n = 11) of the patients.2 In these patients, involved organ systems included the GI tract (73%; n = 8), CNS (64%; n = 7), eye (18%; n = 2), heart (18%; n = 2), and lungs (9%; n = 1); 64% (n = 7) had multiorgan involvement. Mortality was reported in 73% of the patients with systemic disease.

Ongoing testing is required

For a patient presenting with atrophic papulosis, initial and follow-up visits should include evaluation for systemic manifestations through a full skin examination, fecal occult blood test, and ocular fundus examination.1,2 If the patient shows any symptoms that suggest systemic involvement, further testing is advised, including evaluation of renal function, colonoscopy, endoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, an echocardiogram, and chest computed tomography.

Because internal organ involvement in malignant atrophic papulosis can develop within years of (benign) cutaneous manifestations, regular follow-up is recommended.1 Research suggests evaluation of patients with benign atrophic papulosis every 6 months for the first 7 years after disease onset and then yearly between 7 and 10 years after onset.2

Treatment options are limited

Antiplatelet agents (aspirin, pentoxifylline, dipyridamole, and ticlodipine) and anticoagulants (heparin) have led to partial regression of skin lesions in case reports.1 Some lesions seem to disappear after treatment, but due to limited evidence, it is difficult to determine whether treatment leads to a reduction of future lesions.

When it comes to malignant atrophic papulosis, there is no uniformly effective treatment. Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants are often used as initial treatment, but efficacy has not been clearly demonstrated. In case reports, eculizumab and treprostinil have shown effectiveness in treating CNS involvement, but there are no uniform dosage recommendations.3,4

In this case, the patient had mild GI symptoms. A colonoscopy showed evidence of microscopic colitis, but there was no evidence of atrophic papulosis in the GI tract.

Additional laboratory work-up was ordered to evaluate for signs of organ involvement and to rule out any associated connective tissue disease or hypercoagulable state. Her results showed a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (29 mm/h) and a positive antinuclear antibodies assay (1:640, speckled pattern). She was referred to a rheumatologist, who found no evidence of a connective tissue disorder. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, and hypercoagulability work-up were all within normal limits. A complete eye exam was also normal.

The patient was started on aspirin 81 mg/d. Because she continued to develop new lesions, her dermatologist added pentoxifylline extended release and gradually increased the dose to 400 mg in the morning and 800 mg in the evening. About 4 years after onset of the rash, the patient showed no signs of systemic involvement, but her skin lesions were still present.

A 50-year-old woman presented to her family physician for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and an itchy rash. She said the rash had developed 2 years earlier and had gotten worse, with additional lesions emerging on her skin as time went on. She noted that other physicians had evaluated the rash but provided no clear diagnosis and had done no testing.

A physical exam revealed scattered erythematous papules with white centers on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 1). The patient’s medical history was significant for asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, urinary incontinence, and depression. Her medications included montelukast, inhaled fluticasone, albuterol, tolterodine, omeprazole, and fluoxetine.

The patient was prescribed nitrofurantoin, 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, to treat her UTI, and a punch biopsy was performed on one of the patient’s lesions to determine the cause of the rash.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophic papulosis

Pathology suggested a diagnosis of atrophic papulosis. A consultation with a dermatologist and additional biopsies confirmed the diagnosis. The biopsies showed wedge-shaped areas of superficial dermal sclerosis with thinning of the overlying epidermis. The superficial dermal vessels contained scattered, small thrombi at the periphery of the areas of sclerosis.

Atrophic papulosis (also known as Degos disease or Kölmeier-Degos disease) is a vasculopathy characterized by thrombotic occlusion of small arteries.1 Although rare—with fewer than 200 published case reports in the literature—it is likely underdiagnosed.1 Atrophic papulosis can be distinguished by hallmark skin findings, including 0.5- to 1-cm papular skin lesions with central porcelain-white atrophy and an erythematous, telangiectatic rim.1 It usually manifests between ages 20 to 50 but can occur in infants and children.1 The etiology is unknown, but case evidence suggests the condition is sometimes familial.1,2

Easy to confuse with common conditions

Clinical presentation of atrophic papulosis can vary, but evaluation should rule out systemic lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases.1 In addition, the lesions can easily be confused with other common conditions such as molluscum contagiosum or insect bites.

The hallmark finding of molluscum contagiosum is raised papules with central umbilication, whereas atrophic papulosis lesions are characterized by white centers. While insect bites typically disappear within weeks, atrophic papulosis lesions persist for years or are even lifelong.1

Is it benign or malignant?

Benign atrophic papulosis is limited to the skin.1 The probability of a patient having benign atrophic papulosis is about 70% at the onset of skin lesions and 97% after 7 years without other symptoms.2

Malignant atrophic papulosis—although less common—is systemic and life-threatening. About 30% of patients with atrophic papulosis develop lesions manifesting both on the skin and in internal organs.1,2 Systemic involvement can develop at any time, sometimes years after the appearance of skin lesions, but the risk declines over time.2 In a case series, systemic signs were shown to develop, on average, 1 year after skin lesions.2 Some evidence suggests a mortality rate of 50% within 2 to 3 years of the onset of systemic involvement, making regular follow-up necessary.1

Continue to: Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis...

Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis may have systemic involvement in multiple organ systems. Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement can cause bowel perforation. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement may put the patient at risk for stroke, intracranial bleeding, meningitis, and encephalitis.1,3 There can also be cardiopulmonary involvement that causes pleuritis and pericarditis.1 Ocular involvement can affect the eyelids, conjunctiva, retina, sclera, and choroid plexus.1 Renal involvement has been noted in a few cases.2

In a prospective, single-center cohort study of 39 patients with atrophic papulosis, systemic involvement (malignant atrophic papulosis) was reported in 29% (n = 11) of the patients.2 In these patients, involved organ systems included the GI tract (73%; n = 8), CNS (64%; n = 7), eye (18%; n = 2), heart (18%; n = 2), and lungs (9%; n = 1); 64% (n = 7) had multiorgan involvement. Mortality was reported in 73% of the patients with systemic disease.

Ongoing testing is required

For a patient presenting with atrophic papulosis, initial and follow-up visits should include evaluation for systemic manifestations through a full skin examination, fecal occult blood test, and ocular fundus examination.1,2 If the patient shows any symptoms that suggest systemic involvement, further testing is advised, including evaluation of renal function, colonoscopy, endoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, an echocardiogram, and chest computed tomography.

Because internal organ involvement in malignant atrophic papulosis can develop within years of (benign) cutaneous manifestations, regular follow-up is recommended.1 Research suggests evaluation of patients with benign atrophic papulosis every 6 months for the first 7 years after disease onset and then yearly between 7 and 10 years after onset.2

Treatment options are limited

Antiplatelet agents (aspirin, pentoxifylline, dipyridamole, and ticlodipine) and anticoagulants (heparin) have led to partial regression of skin lesions in case reports.1 Some lesions seem to disappear after treatment, but due to limited evidence, it is difficult to determine whether treatment leads to a reduction of future lesions.

When it comes to malignant atrophic papulosis, there is no uniformly effective treatment. Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants are often used as initial treatment, but efficacy has not been clearly demonstrated. In case reports, eculizumab and treprostinil have shown effectiveness in treating CNS involvement, but there are no uniform dosage recommendations.3,4

In this case, the patient had mild GI symptoms. A colonoscopy showed evidence of microscopic colitis, but there was no evidence of atrophic papulosis in the GI tract.

Additional laboratory work-up was ordered to evaluate for signs of organ involvement and to rule out any associated connective tissue disease or hypercoagulable state. Her results showed a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (29 mm/h) and a positive antinuclear antibodies assay (1:640, speckled pattern). She was referred to a rheumatologist, who found no evidence of a connective tissue disorder. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, and hypercoagulability work-up were all within normal limits. A complete eye exam was also normal.

The patient was started on aspirin 81 mg/d. Because she continued to develop new lesions, her dermatologist added pentoxifylline extended release and gradually increased the dose to 400 mg in the morning and 800 mg in the evening. About 4 years after onset of the rash, the patient showed no signs of systemic involvement, but her skin lesions were still present.

1. Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

2. Theodoridis A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, et al. Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease): systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:110-115.

3. Huang YC, Wang JD, Lee FY, et al. Pediatric malignant atrophic papulosis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(suppl 5):S481-S484.

4. Shapiro LS, Toledo-Garcia AE, Farrell JF. Effective treatment of malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) with treprostinil—early experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:52.

1. Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

2. Theodoridis A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, et al. Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease): systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:110-115.

3. Huang YC, Wang JD, Lee FY, et al. Pediatric malignant atrophic papulosis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(suppl 5):S481-S484.

4. Shapiro LS, Toledo-Garcia AE, Farrell JF. Effective treatment of malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) with treprostinil—early experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:52.

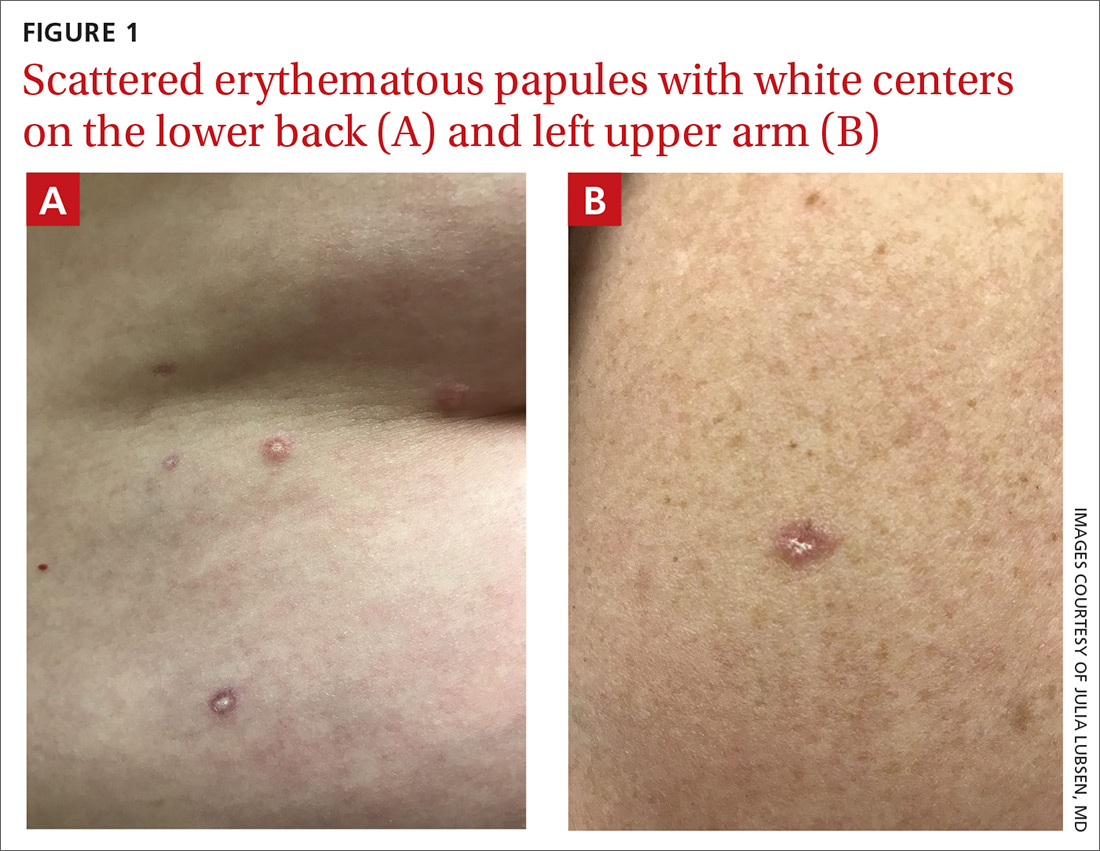

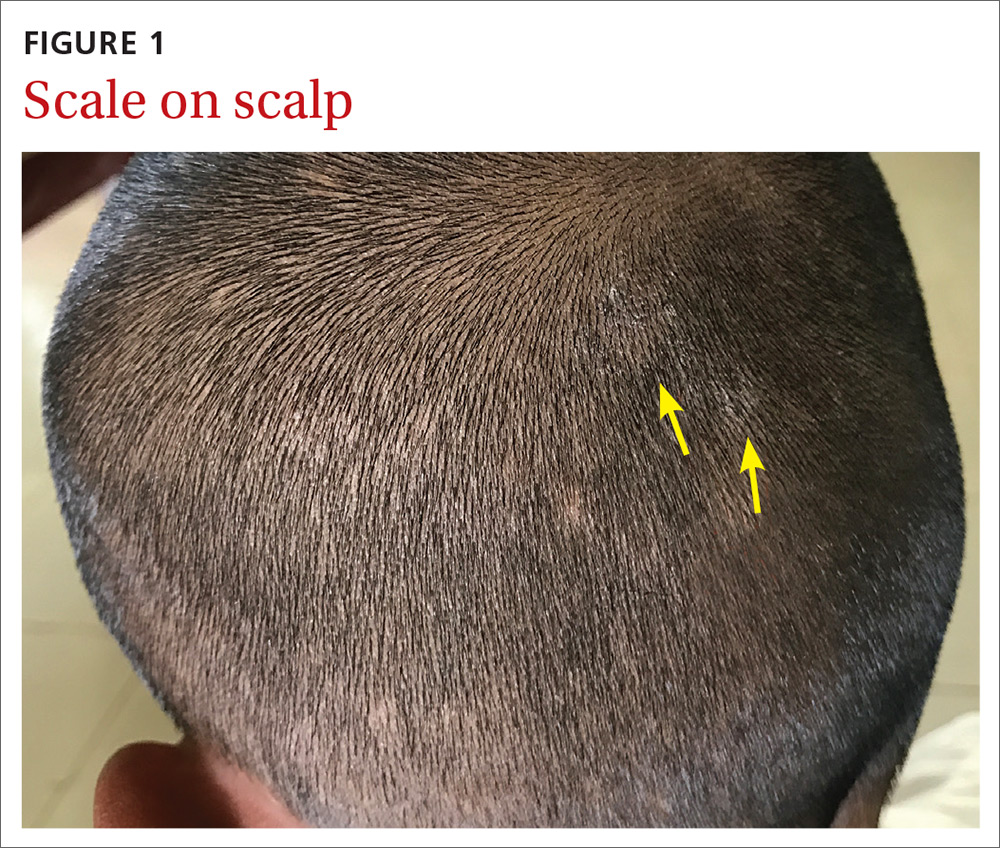

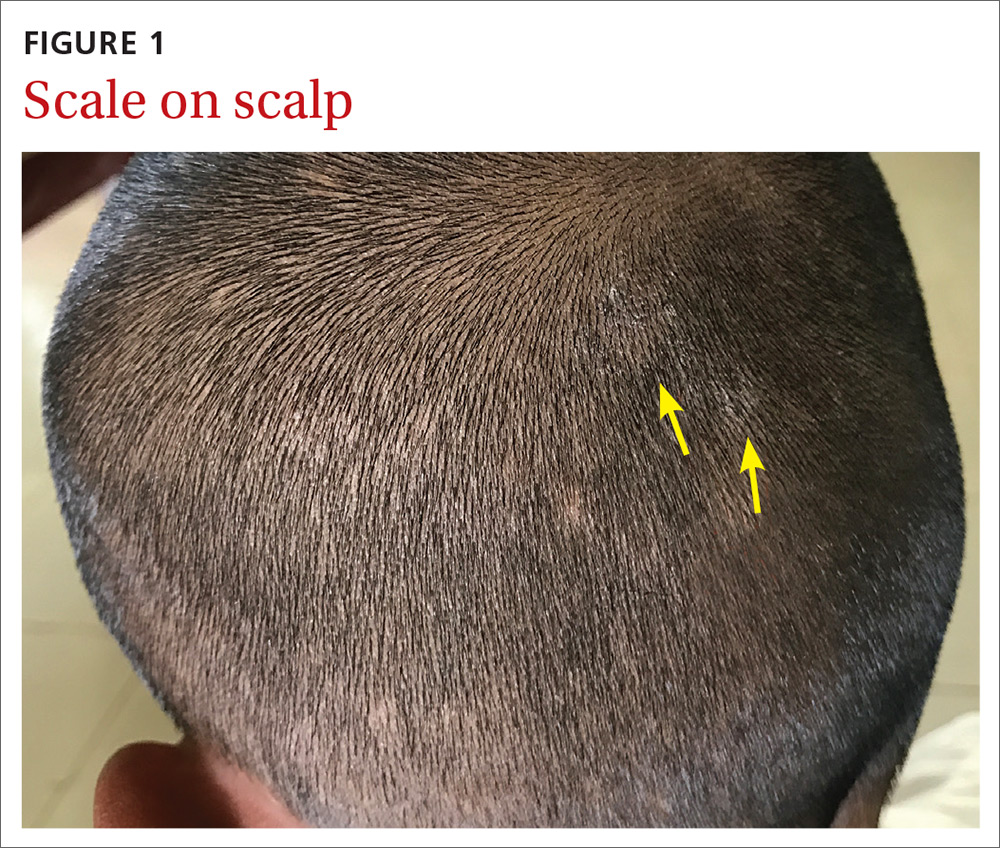

Itchy scalp with scale

An 11-year-old boy sought care at a small village’s health center in Panama for scalp itching and subtle hair loss. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a humanitarian trip. The patient denied any hair pulling. He had a history of treatment for head lice.

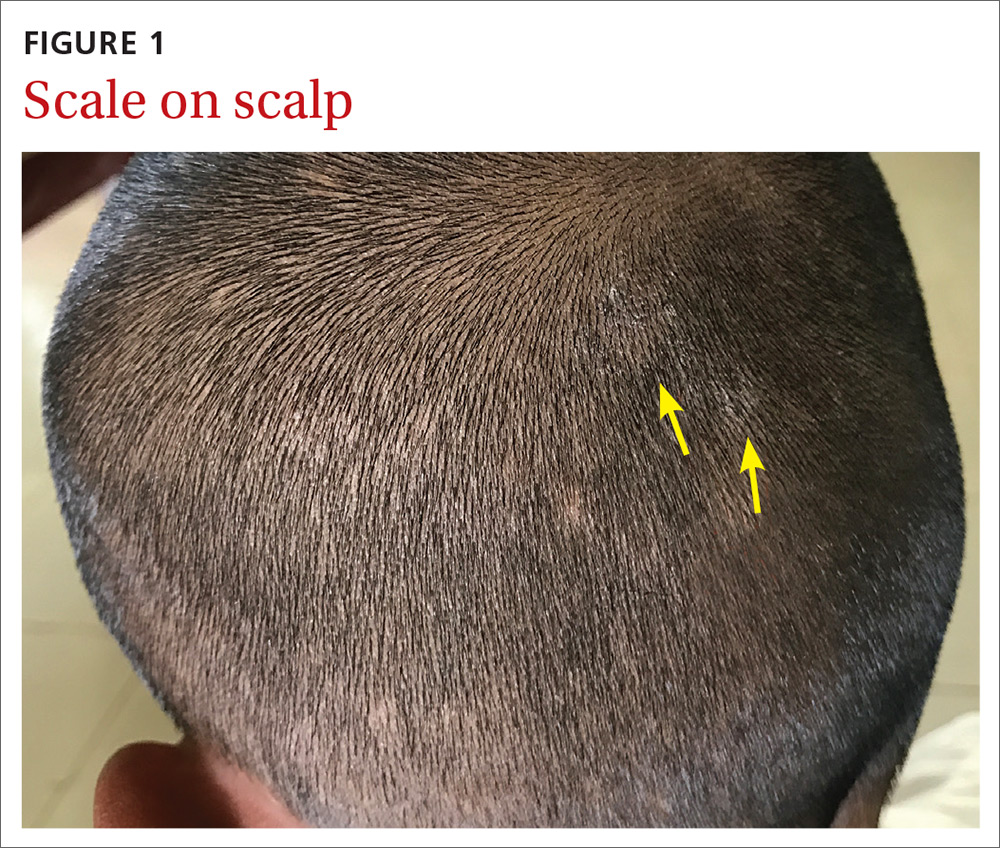

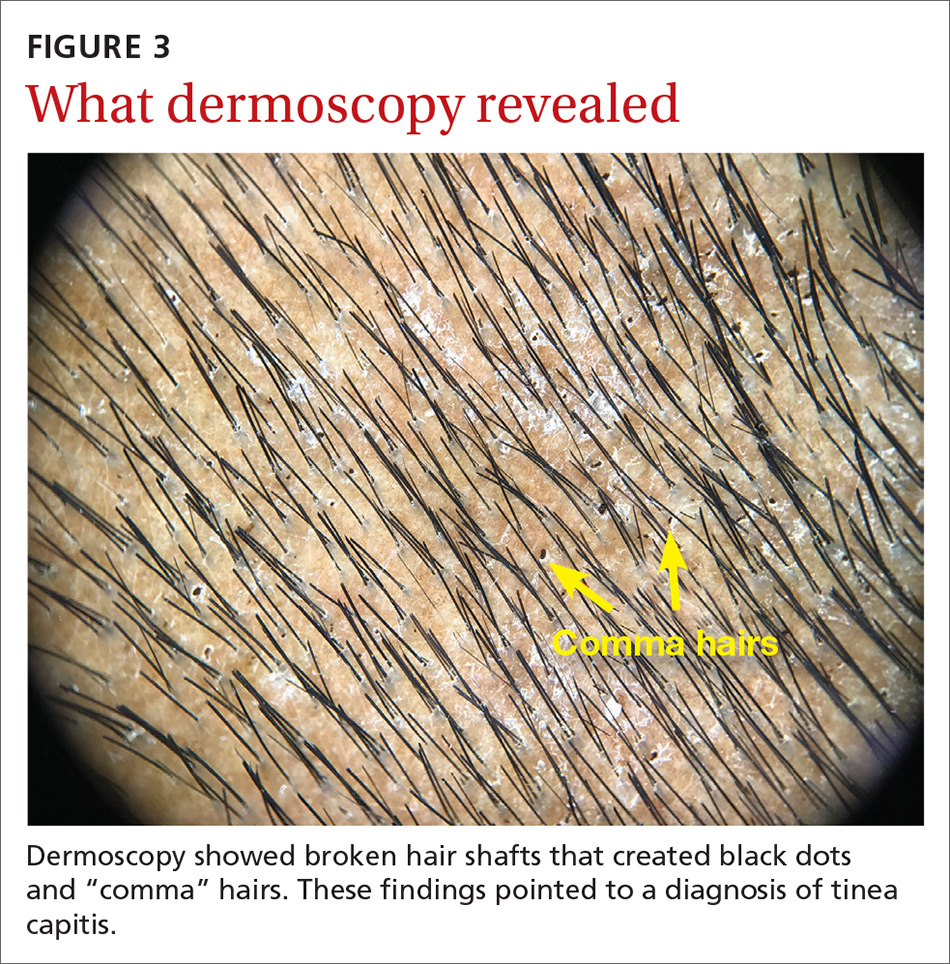

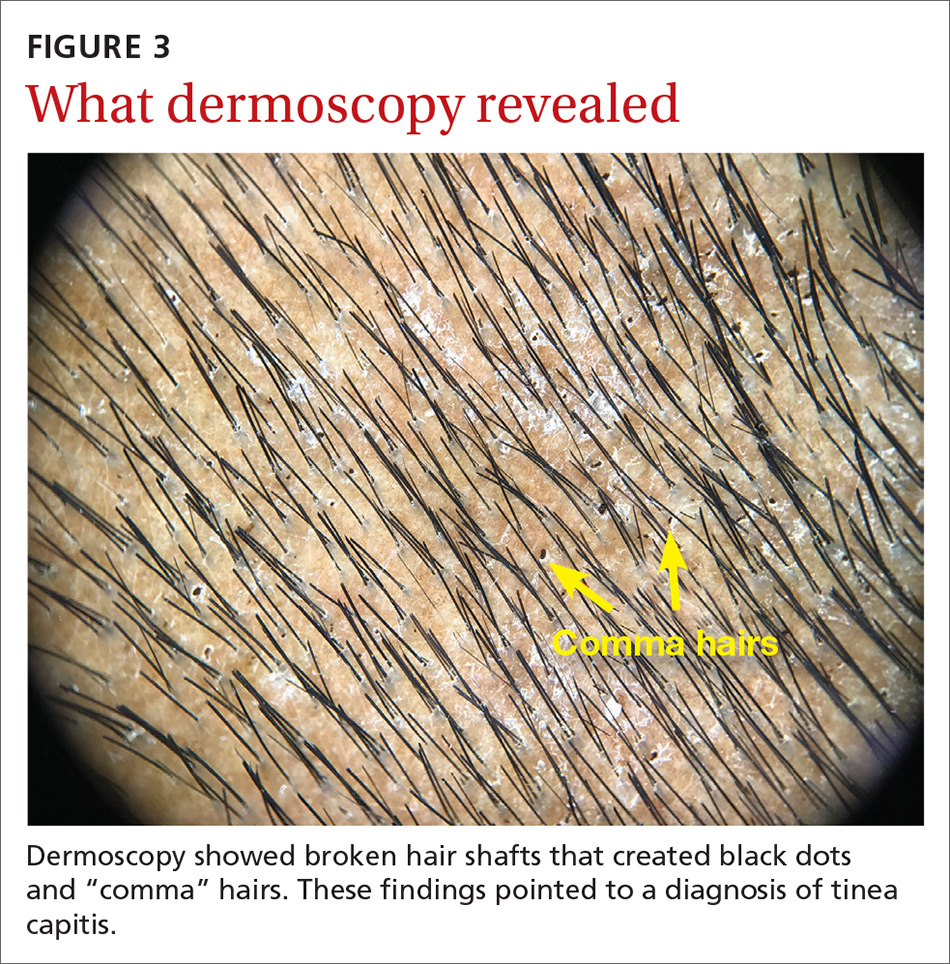

Our physical examination revealed mild alopecia and scaling on the scalp (FIGURE 1), but what we saw through the dermatoscope (FIGURE 2) made the diagnosis clear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea capitis

On dermatoscopic examination (10× magnification), there were numerous “black dots” or broken hair shafts within patches of hair loss (FIGURE 3), which is indicative of tinea capitis.1,2 This condition causes hair shafts to break, creating “comma hairs” and black dots. The hairs are uniform in thickness and color and bend distally, like a comma.3

Tinea capitis (commonly called ringworm of the scalp) is a fungal infection caused by Trichophyton and Microsporum dermatophytes. It is the most common pediatric dermatophyte infection in the world; the usual age of onset is 5 to 10 years.2 The incidence of tinea capitis in the United States is not known because cases are no longer registered by public health agencies. That said, a Northern California study that tracked occurrences in children younger than 15 years from 1998 to 2007 found that the incidence was on the decline and lower in girls compared to boys (111.9 vs 146.4, respectively, in 1998; 27.9 vs 39.9, respectively, in 2007).4 Incidence rates were calculated per 10,000 eligible children.4

Tinea capitis can spread by contact with infected individuals and contaminated objects, including combs, towels, toys, and bedding.1 Fungal spores can remain viable on these surfaces for months.

In a study of 69 patients with tinea capitis (23 females, 46 males; mean age, 12 years), the risk factors for spreading infection included participation in sports, contact with an animal, a recent haircut, and use of a swimming pool.5

4 conditions you’ll want to rule out

The following conditions should be considered as part of the differential when a patient presents with an itchy scalp and/or hair loss.

Continue to: Psoriasis of the scalp...

Psoriasis of the scalp is characterized by scaling of the scalp along with crusted plaques. It is often accompanied by similar psoriatic plaques on the elbows, knees, and other areas of the body. Examination of our patient showed no psoriatic plaques.

Seborrhea of the scalp (also known as dandruff) is a very common diagnosis. However, it is unlikely to cause hair loss. It has widespread involvement of the scalp compared to tinea capitis, which is local and patchy. Our patient’s patches of hair loss indicated that seborrhea was unlikely.

Alopecia areata. Individuals develop this condition due to an autoimmune process affecting hair follicles. However, the resulting hair loss does not cause significant scaling, inflammation, scarring, or pain in the affected area. Further, this condition can cause the loss of the entire hair shaft.

Trichotillomania is an impulse control disorder that causes patients to pull out their own hair. There is no scaling of the scalp in this condition.

A dermatoscope can beuseful in making the Dx

Although clinical appearance and patient presentation are adequate to establish the diagnosis of tinea capitis, this case demonstrates the utility of a dermatoscope in making the diagnosis of tinea capitis. Previous studies have shown that dermoscopy allows for rapid identification of the broken hair shafts, which are a key distinction from alopecia areata.3,6

Microscopic inspection. Samples from the scaling of the scalp can be examined with potassium hydroxide (KOH) on a microscope slide. Hyphae, spores, and endo/ectothrix invasion can be seen through the microsope.

Continue to: Laboratory testing is helpful, but not needed.

Laboratory testing is helpful, but not needed. Testing for tinea capitis would require that you obtain a sample from the affected area using a swab, edge of a scalpel blade, or scalp brush.7 Because treatment can require weeks of medication, diagnosis should be confirmed with a KOH or culture when possible.

Newer antifungalsprovide a Tx advantage

Oral antifungal medications are the treatment of choice for tinea capitis. Newer antifungals, such as terbinafine and fluconazole, require a 3- to 6-week course compared to the standard 6- to 8-week course of griseofulvin.1 Also, antifungal shampoos—such as those that contain selenium sulfide—may be used for topical treatment but only as adjuvant therapy.1,2

For our patient, we dispensed a 3-week course of oral fluconazole, 3 to 6 mg/kg, to be given daily by his parents. We also recommended the use of an antidandruff shampoo, if possible. The treatment outcome was not known because our team’s humanitarian global health trip had ended.

1. Usatine R, Smith MA, Mayeaux Jr EJ, Chumley HS. The Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019.

2. Handler MZ. Tinea capitis. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1091351-overview. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020.

3. Hernández-Bel P, Malvehy J, Crocker A, et al. Comma hairs: a new dermoscopic marker for tinea capitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:836-837.

4. Mirmirani P, Lue-Yen T. Epidemiologic trends in pediatric tinea capitis: a population-based study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:916-921.

5. Mikaeili A, Kavaoussi H, Hashemian AH, et al. Clinico-mycological profile of tinea capitis and its comparative response to griseofulvin versus terbinafine. Curr Med Mycol. 2019;5:15-20.

6. Slowinska M, Rudnicka L, Schwartz RA, et al. Comma hairs: a dermatoscopic marker for tinea capitis: a rapid diagnostic method. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008;59(suppl 5):S77-S79.

An 11-year-old boy sought care at a small village’s health center in Panama for scalp itching and subtle hair loss. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a humanitarian trip. The patient denied any hair pulling. He had a history of treatment for head lice.

Our physical examination revealed mild alopecia and scaling on the scalp (FIGURE 1), but what we saw through the dermatoscope (FIGURE 2) made the diagnosis clear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea capitis

On dermatoscopic examination (10× magnification), there were numerous “black dots” or broken hair shafts within patches of hair loss (FIGURE 3), which is indicative of tinea capitis.1,2 This condition causes hair shafts to break, creating “comma hairs” and black dots. The hairs are uniform in thickness and color and bend distally, like a comma.3

Tinea capitis (commonly called ringworm of the scalp) is a fungal infection caused by Trichophyton and Microsporum dermatophytes. It is the most common pediatric dermatophyte infection in the world; the usual age of onset is 5 to 10 years.2 The incidence of tinea capitis in the United States is not known because cases are no longer registered by public health agencies. That said, a Northern California study that tracked occurrences in children younger than 15 years from 1998 to 2007 found that the incidence was on the decline and lower in girls compared to boys (111.9 vs 146.4, respectively, in 1998; 27.9 vs 39.9, respectively, in 2007).4 Incidence rates were calculated per 10,000 eligible children.4

Tinea capitis can spread by contact with infected individuals and contaminated objects, including combs, towels, toys, and bedding.1 Fungal spores can remain viable on these surfaces for months.

In a study of 69 patients with tinea capitis (23 females, 46 males; mean age, 12 years), the risk factors for spreading infection included participation in sports, contact with an animal, a recent haircut, and use of a swimming pool.5

4 conditions you’ll want to rule out

The following conditions should be considered as part of the differential when a patient presents with an itchy scalp and/or hair loss.

Continue to: Psoriasis of the scalp...

Psoriasis of the scalp is characterized by scaling of the scalp along with crusted plaques. It is often accompanied by similar psoriatic plaques on the elbows, knees, and other areas of the body. Examination of our patient showed no psoriatic plaques.

Seborrhea of the scalp (also known as dandruff) is a very common diagnosis. However, it is unlikely to cause hair loss. It has widespread involvement of the scalp compared to tinea capitis, which is local and patchy. Our patient’s patches of hair loss indicated that seborrhea was unlikely.

Alopecia areata. Individuals develop this condition due to an autoimmune process affecting hair follicles. However, the resulting hair loss does not cause significant scaling, inflammation, scarring, or pain in the affected area. Further, this condition can cause the loss of the entire hair shaft.

Trichotillomania is an impulse control disorder that causes patients to pull out their own hair. There is no scaling of the scalp in this condition.

A dermatoscope can beuseful in making the Dx

Although clinical appearance and patient presentation are adequate to establish the diagnosis of tinea capitis, this case demonstrates the utility of a dermatoscope in making the diagnosis of tinea capitis. Previous studies have shown that dermoscopy allows for rapid identification of the broken hair shafts, which are a key distinction from alopecia areata.3,6

Microscopic inspection. Samples from the scaling of the scalp can be examined with potassium hydroxide (KOH) on a microscope slide. Hyphae, spores, and endo/ectothrix invasion can be seen through the microsope.

Continue to: Laboratory testing is helpful, but not needed.

Laboratory testing is helpful, but not needed. Testing for tinea capitis would require that you obtain a sample from the affected area using a swab, edge of a scalpel blade, or scalp brush.7 Because treatment can require weeks of medication, diagnosis should be confirmed with a KOH or culture when possible.

Newer antifungalsprovide a Tx advantage

Oral antifungal medications are the treatment of choice for tinea capitis. Newer antifungals, such as terbinafine and fluconazole, require a 3- to 6-week course compared to the standard 6- to 8-week course of griseofulvin.1 Also, antifungal shampoos—such as those that contain selenium sulfide—may be used for topical treatment but only as adjuvant therapy.1,2

For our patient, we dispensed a 3-week course of oral fluconazole, 3 to 6 mg/kg, to be given daily by his parents. We also recommended the use of an antidandruff shampoo, if possible. The treatment outcome was not known because our team’s humanitarian global health trip had ended.

An 11-year-old boy sought care at a small village’s health center in Panama for scalp itching and subtle hair loss. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a humanitarian trip. The patient denied any hair pulling. He had a history of treatment for head lice.

Our physical examination revealed mild alopecia and scaling on the scalp (FIGURE 1), but what we saw through the dermatoscope (FIGURE 2) made the diagnosis clear.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea capitis

On dermatoscopic examination (10× magnification), there were numerous “black dots” or broken hair shafts within patches of hair loss (FIGURE 3), which is indicative of tinea capitis.1,2 This condition causes hair shafts to break, creating “comma hairs” and black dots. The hairs are uniform in thickness and color and bend distally, like a comma.3

Tinea capitis (commonly called ringworm of the scalp) is a fungal infection caused by Trichophyton and Microsporum dermatophytes. It is the most common pediatric dermatophyte infection in the world; the usual age of onset is 5 to 10 years.2 The incidence of tinea capitis in the United States is not known because cases are no longer registered by public health agencies. That said, a Northern California study that tracked occurrences in children younger than 15 years from 1998 to 2007 found that the incidence was on the decline and lower in girls compared to boys (111.9 vs 146.4, respectively, in 1998; 27.9 vs 39.9, respectively, in 2007).4 Incidence rates were calculated per 10,000 eligible children.4

Tinea capitis can spread by contact with infected individuals and contaminated objects, including combs, towels, toys, and bedding.1 Fungal spores can remain viable on these surfaces for months.

In a study of 69 patients with tinea capitis (23 females, 46 males; mean age, 12 years), the risk factors for spreading infection included participation in sports, contact with an animal, a recent haircut, and use of a swimming pool.5

4 conditions you’ll want to rule out

The following conditions should be considered as part of the differential when a patient presents with an itchy scalp and/or hair loss.

Continue to: Psoriasis of the scalp...

Psoriasis of the scalp is characterized by scaling of the scalp along with crusted plaques. It is often accompanied by similar psoriatic plaques on the elbows, knees, and other areas of the body. Examination of our patient showed no psoriatic plaques.

Seborrhea of the scalp (also known as dandruff) is a very common diagnosis. However, it is unlikely to cause hair loss. It has widespread involvement of the scalp compared to tinea capitis, which is local and patchy. Our patient’s patches of hair loss indicated that seborrhea was unlikely.

Alopecia areata. Individuals develop this condition due to an autoimmune process affecting hair follicles. However, the resulting hair loss does not cause significant scaling, inflammation, scarring, or pain in the affected area. Further, this condition can cause the loss of the entire hair shaft.

Trichotillomania is an impulse control disorder that causes patients to pull out their own hair. There is no scaling of the scalp in this condition.

A dermatoscope can beuseful in making the Dx

Although clinical appearance and patient presentation are adequate to establish the diagnosis of tinea capitis, this case demonstrates the utility of a dermatoscope in making the diagnosis of tinea capitis. Previous studies have shown that dermoscopy allows for rapid identification of the broken hair shafts, which are a key distinction from alopecia areata.3,6

Microscopic inspection. Samples from the scaling of the scalp can be examined with potassium hydroxide (KOH) on a microscope slide. Hyphae, spores, and endo/ectothrix invasion can be seen through the microsope.

Continue to: Laboratory testing is helpful, but not needed.

Laboratory testing is helpful, but not needed. Testing for tinea capitis would require that you obtain a sample from the affected area using a swab, edge of a scalpel blade, or scalp brush.7 Because treatment can require weeks of medication, diagnosis should be confirmed with a KOH or culture when possible.

Newer antifungalsprovide a Tx advantage

Oral antifungal medications are the treatment of choice for tinea capitis. Newer antifungals, such as terbinafine and fluconazole, require a 3- to 6-week course compared to the standard 6- to 8-week course of griseofulvin.1 Also, antifungal shampoos—such as those that contain selenium sulfide—may be used for topical treatment but only as adjuvant therapy.1,2

For our patient, we dispensed a 3-week course of oral fluconazole, 3 to 6 mg/kg, to be given daily by his parents. We also recommended the use of an antidandruff shampoo, if possible. The treatment outcome was not known because our team’s humanitarian global health trip had ended.

1. Usatine R, Smith MA, Mayeaux Jr EJ, Chumley HS. The Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019.

2. Handler MZ. Tinea capitis. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1091351-overview. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020.

3. Hernández-Bel P, Malvehy J, Crocker A, et al. Comma hairs: a new dermoscopic marker for tinea capitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:836-837.

4. Mirmirani P, Lue-Yen T. Epidemiologic trends in pediatric tinea capitis: a population-based study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:916-921.

5. Mikaeili A, Kavaoussi H, Hashemian AH, et al. Clinico-mycological profile of tinea capitis and its comparative response to griseofulvin versus terbinafine. Curr Med Mycol. 2019;5:15-20.

6. Slowinska M, Rudnicka L, Schwartz RA, et al. Comma hairs: a dermatoscopic marker for tinea capitis: a rapid diagnostic method. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008;59(suppl 5):S77-S79.

1. Usatine R, Smith MA, Mayeaux Jr EJ, Chumley HS. The Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019.

2. Handler MZ. Tinea capitis. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1091351-overview. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020.

3. Hernández-Bel P, Malvehy J, Crocker A, et al. Comma hairs: a new dermoscopic marker for tinea capitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:836-837.

4. Mirmirani P, Lue-Yen T. Epidemiologic trends in pediatric tinea capitis: a population-based study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:916-921.

5. Mikaeili A, Kavaoussi H, Hashemian AH, et al. Clinico-mycological profile of tinea capitis and its comparative response to griseofulvin versus terbinafine. Curr Med Mycol. 2019;5:15-20.

6. Slowinska M, Rudnicka L, Schwartz RA, et al. Comma hairs: a dermatoscopic marker for tinea capitis: a rapid diagnostic method. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008;59(suppl 5):S77-S79.

Painful, lower extremity rash

This woman’s palpable purpura with edema in her lower extremities was consistent with cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV).

LCV is characterized by the circulation of immune complexes that promote activation of complement, leading to endothelial injury and palpable purpura. Pain, arthralgia, cutaneous ulceration, and constitutional symptoms may be observed. About 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic. Identified causes include infection (including syphilis infection), drugs, malignancy, and connective tissue disease.

Systemic involvement must be ruled out in any patient with cutaneous LCV. The work-up is based on the individual patient assessment and may include a complete blood count with differential, complete metabolic panel, inflammatory markers, urinalysis, hepatitis panel, anti-nuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, cryoglobulins, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum complement. A cutaneous punch biopsy for both hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) confirms the diagnosis of LCV.

For uncomplicated LCV cases without systemic involvement, treatment is generally supportive. Any identified underlying cause should be addressed. Analgesics may be considered for pain. Systemic therapy is indicated for patients with cutaneous ulceration, systemic vasculitis, or recurrent cases; this therapy may include colchicine, dapsone, corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate.

In this patient’s case, a punch biopsy of the left lower extremity showed findings consistent with cutaneous LCV. She denied a history of intravenous drug use or initiation of new medications. Labs were notable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, c-reactive protein, and elevated creatinine.

Incidentally, she was found to be 32-weeks pregnant, went into pre-term labor while admitted, and delivered her baby without complication.

She had a reactive treponemal antibody, with rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:128, which confirmed a diagnosis of syphilis. She was treated with 1 dose of intra-muscular penicillin G while an inpatient. Her arthralgias improved during her hospitalization without initiation of steroids or other immunomodulatory therapy. Outpatient follow-up was expected to consist of completion of 3 total doses of IM penicillin, as well as renal studies, given her elevated creatinine.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle R. Fermin, MD, and text courtesy of Cyrelle R. Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Goeser MR, Laniosz V, Wetter DA. A practical approach to the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:299-306.

This woman’s palpable purpura with edema in her lower extremities was consistent with cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV).

LCV is characterized by the circulation of immune complexes that promote activation of complement, leading to endothelial injury and palpable purpura. Pain, arthralgia, cutaneous ulceration, and constitutional symptoms may be observed. About 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic. Identified causes include infection (including syphilis infection), drugs, malignancy, and connective tissue disease.

Systemic involvement must be ruled out in any patient with cutaneous LCV. The work-up is based on the individual patient assessment and may include a complete blood count with differential, complete metabolic panel, inflammatory markers, urinalysis, hepatitis panel, anti-nuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, cryoglobulins, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum complement. A cutaneous punch biopsy for both hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) confirms the diagnosis of LCV.

For uncomplicated LCV cases without systemic involvement, treatment is generally supportive. Any identified underlying cause should be addressed. Analgesics may be considered for pain. Systemic therapy is indicated for patients with cutaneous ulceration, systemic vasculitis, or recurrent cases; this therapy may include colchicine, dapsone, corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate.

In this patient’s case, a punch biopsy of the left lower extremity showed findings consistent with cutaneous LCV. She denied a history of intravenous drug use or initiation of new medications. Labs were notable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, c-reactive protein, and elevated creatinine.

Incidentally, she was found to be 32-weeks pregnant, went into pre-term labor while admitted, and delivered her baby without complication.

She had a reactive treponemal antibody, with rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:128, which confirmed a diagnosis of syphilis. She was treated with 1 dose of intra-muscular penicillin G while an inpatient. Her arthralgias improved during her hospitalization without initiation of steroids or other immunomodulatory therapy. Outpatient follow-up was expected to consist of completion of 3 total doses of IM penicillin, as well as renal studies, given her elevated creatinine.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle R. Fermin, MD, and text courtesy of Cyrelle R. Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

This woman’s palpable purpura with edema in her lower extremities was consistent with cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV).

LCV is characterized by the circulation of immune complexes that promote activation of complement, leading to endothelial injury and palpable purpura. Pain, arthralgia, cutaneous ulceration, and constitutional symptoms may be observed. About 50% of LCV cases are idiopathic. Identified causes include infection (including syphilis infection), drugs, malignancy, and connective tissue disease.

Systemic involvement must be ruled out in any patient with cutaneous LCV. The work-up is based on the individual patient assessment and may include a complete blood count with differential, complete metabolic panel, inflammatory markers, urinalysis, hepatitis panel, anti-nuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, cryoglobulins, serum protein electrophoresis, and serum complement. A cutaneous punch biopsy for both hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) confirms the diagnosis of LCV.

For uncomplicated LCV cases without systemic involvement, treatment is generally supportive. Any identified underlying cause should be addressed. Analgesics may be considered for pain. Systemic therapy is indicated for patients with cutaneous ulceration, systemic vasculitis, or recurrent cases; this therapy may include colchicine, dapsone, corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate.

In this patient’s case, a punch biopsy of the left lower extremity showed findings consistent with cutaneous LCV. She denied a history of intravenous drug use or initiation of new medications. Labs were notable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, c-reactive protein, and elevated creatinine.

Incidentally, she was found to be 32-weeks pregnant, went into pre-term labor while admitted, and delivered her baby without complication.

She had a reactive treponemal antibody, with rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:128, which confirmed a diagnosis of syphilis. She was treated with 1 dose of intra-muscular penicillin G while an inpatient. Her arthralgias improved during her hospitalization without initiation of steroids or other immunomodulatory therapy. Outpatient follow-up was expected to consist of completion of 3 total doses of IM penicillin, as well as renal studies, given her elevated creatinine.

Photo courtesy of Cyrelle R. Fermin, MD, and text courtesy of Cyrelle R. Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Goeser MR, Laniosz V, Wetter DA. A practical approach to the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:299-306.

Goeser MR, Laniosz V, Wetter DA. A practical approach to the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:299-306.

“Polka-dotted” feet

This man has pitted keratolysis (PK), characterized by multiple small pits on the soles of the feet. PK is often associated with hyperhidrosis and significant odor. The lesions usually have a punched-out appearance and are flesh-colored. The dark color of these lesions was due to the patient’s footwear.

PK is caused by bacterial overgrowth in the stratum corneum. Corynebacterium is the most common bacterial culprit, but Kytococcus, Actinomyces, and Dermatophilus have also been implicated. The bacterial infection is thought to be secondary to hyperhidrosis or as a result of hygiene, footwear, or other conditions that retain moisture and promote maceration of the soles of the feet. Therefore, treatment includes a 2-pronged approach: Resolve the bacterial infection and reduce excess moisture. Effective antibacterials include topical clindamycin, erythromycin, fusidic acid, and benzoyl peroxide. Oral antibiotics are not often required.

Hyperhidrosis can be treated with prescription strength 20% aluminum chloride antiperspirant applied to the feet in a tapering schedule, first daily and then 2 or 3 times weekly. Aluminum chloride is frequently not covered by insurance companies, but over-the-counter (OTC) 12% formulations (Certain DRI) usually suffice. Additionally, changing socks and using moisture-wicking shoes or socks are helpful measures to keep feet dry.

One study treated PK with topical erythromycin 3% gel twice daily, without the use of aluminum chloride antiperspirants, and found that the hyperhidrosis greatly improved. The authors theorized that the gram-positive bacterial infection upregulated eccrine sweat glands causing hyperhidrosis as a secondary, rather than the primary, cause of PK.

This patient was prescribed topical erythromycin gel twice daily for the soles of his feet. For his hyperhidrosis, he was advised to purchase OTC aluminum chloride antiperspirants to apply to his feet daily for the first week and to then decrease to 2 or 3 times per week. He was counseled to take an extra pair of socks for changing midway through his workday and to return for reevaluation if his skin did not improve.

Image courtesy of Sarah Friedberg, MD, and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, and Sarah Friedberg, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.