User login

Itchy, scaly lesions with sweating

The patient’s history of a rash that worsened with sweating and clinical findings of erythematous papulosquamous lesions was consistent with Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis. Typically, this is a short-lived condition; however, when symptoms have manifested for years, it is deemed persistent acantholytic dermatosis. The gold standard for diagnostic confirmation is a skin biopsy, although it can also be diagnosed clinically. Since the patient had previously received this diagnosis from another clinician, and his clinical presentation was consistent, a confirmatory biopsy was not performed.

The specific pathophysiology of acantholytic dermatosis is unclear. A study to assess for an autoimmune component found that all participants had autoantibodies that are reactive to proteins involved in cell development, activation, growth, death, adhesion, and motility. Another hypothesis involves occlusion of eccrine sweat glands.

Typical triggers are sweating, heat, sunlight, and mechanical irritation, although it can also be triggered by end-stage renal disease and solid organ transplantation. It has also been linked to certain drugs (eg, ribavirin, anastrozole), other skin diseases (eg, atopic dermatitis, xerosis cutis), bacterial/viral infections, and malignancies.

As heat and perspiration are common triggers, avoidance of activities that expose patients to these conditions is recommended. Otherwise, topical corticosteroids and emollients are the recommended first-line therapy, along with antihistamines to control itching. Other therapies include systemic corticosteroids, topical vitamin D analogs (eg, calcipotriene), systemic retinoids (acitretin or isotretinoin), phototherapy and photochemotherapy (PUVA), red-light 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT), and etanercept.

Although the patient could not remember the name of the previously prescribed medication, his description suggested that a systemic retinoid had already been tried, with no improvement. Treatment with emollients and oral antihistamines was also unsuccessful, as was topical antiperspirants to control perspiration on his affected skin. The patient agreed to try topical calcipotriene twice daily. He also agreed to switch to a topical emollient containing ceramides.

Image courtesy of Esther Walker, MD, and text courtesy of Esther Walker, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Phillips C, Kalantari-Dehaghi M, Marchenko S, et al. Is Grover's disease an autoimmune dermatosis? Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:781-784.

The patient’s history of a rash that worsened with sweating and clinical findings of erythematous papulosquamous lesions was consistent with Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis. Typically, this is a short-lived condition; however, when symptoms have manifested for years, it is deemed persistent acantholytic dermatosis. The gold standard for diagnostic confirmation is a skin biopsy, although it can also be diagnosed clinically. Since the patient had previously received this diagnosis from another clinician, and his clinical presentation was consistent, a confirmatory biopsy was not performed.

The specific pathophysiology of acantholytic dermatosis is unclear. A study to assess for an autoimmune component found that all participants had autoantibodies that are reactive to proteins involved in cell development, activation, growth, death, adhesion, and motility. Another hypothesis involves occlusion of eccrine sweat glands.

Typical triggers are sweating, heat, sunlight, and mechanical irritation, although it can also be triggered by end-stage renal disease and solid organ transplantation. It has also been linked to certain drugs (eg, ribavirin, anastrozole), other skin diseases (eg, atopic dermatitis, xerosis cutis), bacterial/viral infections, and malignancies.

As heat and perspiration are common triggers, avoidance of activities that expose patients to these conditions is recommended. Otherwise, topical corticosteroids and emollients are the recommended first-line therapy, along with antihistamines to control itching. Other therapies include systemic corticosteroids, topical vitamin D analogs (eg, calcipotriene), systemic retinoids (acitretin or isotretinoin), phototherapy and photochemotherapy (PUVA), red-light 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT), and etanercept.

Although the patient could not remember the name of the previously prescribed medication, his description suggested that a systemic retinoid had already been tried, with no improvement. Treatment with emollients and oral antihistamines was also unsuccessful, as was topical antiperspirants to control perspiration on his affected skin. The patient agreed to try topical calcipotriene twice daily. He also agreed to switch to a topical emollient containing ceramides.

Image courtesy of Esther Walker, MD, and text courtesy of Esther Walker, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The patient’s history of a rash that worsened with sweating and clinical findings of erythematous papulosquamous lesions was consistent with Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis. Typically, this is a short-lived condition; however, when symptoms have manifested for years, it is deemed persistent acantholytic dermatosis. The gold standard for diagnostic confirmation is a skin biopsy, although it can also be diagnosed clinically. Since the patient had previously received this diagnosis from another clinician, and his clinical presentation was consistent, a confirmatory biopsy was not performed.

The specific pathophysiology of acantholytic dermatosis is unclear. A study to assess for an autoimmune component found that all participants had autoantibodies that are reactive to proteins involved in cell development, activation, growth, death, adhesion, and motility. Another hypothesis involves occlusion of eccrine sweat glands.

Typical triggers are sweating, heat, sunlight, and mechanical irritation, although it can also be triggered by end-stage renal disease and solid organ transplantation. It has also been linked to certain drugs (eg, ribavirin, anastrozole), other skin diseases (eg, atopic dermatitis, xerosis cutis), bacterial/viral infections, and malignancies.

As heat and perspiration are common triggers, avoidance of activities that expose patients to these conditions is recommended. Otherwise, topical corticosteroids and emollients are the recommended first-line therapy, along with antihistamines to control itching. Other therapies include systemic corticosteroids, topical vitamin D analogs (eg, calcipotriene), systemic retinoids (acitretin or isotretinoin), phototherapy and photochemotherapy (PUVA), red-light 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT), and etanercept.

Although the patient could not remember the name of the previously prescribed medication, his description suggested that a systemic retinoid had already been tried, with no improvement. Treatment with emollients and oral antihistamines was also unsuccessful, as was topical antiperspirants to control perspiration on his affected skin. The patient agreed to try topical calcipotriene twice daily. He also agreed to switch to a topical emollient containing ceramides.

Image courtesy of Esther Walker, MD, and text courtesy of Esther Walker, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Phillips C, Kalantari-Dehaghi M, Marchenko S, et al. Is Grover's disease an autoimmune dermatosis? Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:781-784.

Phillips C, Kalantari-Dehaghi M, Marchenko S, et al. Is Grover's disease an autoimmune dermatosis? Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:781-784.

Painful pustules on hands

Close inspection of the plaques revealed multiple small pustules and mahogany colored macules on a broad, well-demarcated scaly red plaque. This pattern was consistent with palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Palmoplantar psoriasis is a chronic disease that may manifest at any age and in both sexes. The diagnosis may be clinical, as it was in this case. Bacterial culture of a pustule may demonstrate staphylococcus superinfection—a problem more likely to occur in smokers. More widespread disease, spiking fevers, or tachycardia could indicate a need for hospitalization for further work-up and management.

With disease localized to this patient’s hands and feet, the physician considered dyshidrotic eczema as part of the differential diagnosis. However dyshidrotic eczema, which presents with clear tapioca-like vesicles, is profoundly itchy; pustular psoriasis is often painful. Other differences: The vesicles in dyshidrotic eczema do not uniformly form pustules nor do they form brown macules upon healing, as occurs in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Treatment for very limited disease includes topical ultrapotent steroids, topical retinoids, or phototherapy—either alone or in combination. However, more extensive disease, even if limited to hands and feet, merits systemic therapy with acitretin, methotrexate, or biologic agents. (Acitretin and methotrexate are reliable teratogens and should not be used in women who are, or may become, pregnant.) Individuals with known superinfection often benefit from antibiotic therapy, as well.

In this case, the patient had already undergone a tubal ligation for contraception. Therefore, she was started on acitretin 25 mg PO daily. Patients on systemic retinoids undergo laboratory surveillance for transaminitis and hypertriglyceridemia regularly. Adverse effects are generally well tolerated, but include photosensitivity and dry skin, lips, and eyes. The patient improved significantly on 25 mg/d and the dosage was reduced to 10 mg/d after 3 months. She currently remains clear on this regimen.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L. Palmoplantar pustulosis: recent advances in etiopathogenesis and emerging treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:355-370.

Close inspection of the plaques revealed multiple small pustules and mahogany colored macules on a broad, well-demarcated scaly red plaque. This pattern was consistent with palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Palmoplantar psoriasis is a chronic disease that may manifest at any age and in both sexes. The diagnosis may be clinical, as it was in this case. Bacterial culture of a pustule may demonstrate staphylococcus superinfection—a problem more likely to occur in smokers. More widespread disease, spiking fevers, or tachycardia could indicate a need for hospitalization for further work-up and management.

With disease localized to this patient’s hands and feet, the physician considered dyshidrotic eczema as part of the differential diagnosis. However dyshidrotic eczema, which presents with clear tapioca-like vesicles, is profoundly itchy; pustular psoriasis is often painful. Other differences: The vesicles in dyshidrotic eczema do not uniformly form pustules nor do they form brown macules upon healing, as occurs in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Treatment for very limited disease includes topical ultrapotent steroids, topical retinoids, or phototherapy—either alone or in combination. However, more extensive disease, even if limited to hands and feet, merits systemic therapy with acitretin, methotrexate, or biologic agents. (Acitretin and methotrexate are reliable teratogens and should not be used in women who are, or may become, pregnant.) Individuals with known superinfection often benefit from antibiotic therapy, as well.

In this case, the patient had already undergone a tubal ligation for contraception. Therefore, she was started on acitretin 25 mg PO daily. Patients on systemic retinoids undergo laboratory surveillance for transaminitis and hypertriglyceridemia regularly. Adverse effects are generally well tolerated, but include photosensitivity and dry skin, lips, and eyes. The patient improved significantly on 25 mg/d and the dosage was reduced to 10 mg/d after 3 months. She currently remains clear on this regimen.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Close inspection of the plaques revealed multiple small pustules and mahogany colored macules on a broad, well-demarcated scaly red plaque. This pattern was consistent with palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Palmoplantar psoriasis is a chronic disease that may manifest at any age and in both sexes. The diagnosis may be clinical, as it was in this case. Bacterial culture of a pustule may demonstrate staphylococcus superinfection—a problem more likely to occur in smokers. More widespread disease, spiking fevers, or tachycardia could indicate a need for hospitalization for further work-up and management.

With disease localized to this patient’s hands and feet, the physician considered dyshidrotic eczema as part of the differential diagnosis. However dyshidrotic eczema, which presents with clear tapioca-like vesicles, is profoundly itchy; pustular psoriasis is often painful. Other differences: The vesicles in dyshidrotic eczema do not uniformly form pustules nor do they form brown macules upon healing, as occurs in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Treatment for very limited disease includes topical ultrapotent steroids, topical retinoids, or phototherapy—either alone or in combination. However, more extensive disease, even if limited to hands and feet, merits systemic therapy with acitretin, methotrexate, or biologic agents. (Acitretin and methotrexate are reliable teratogens and should not be used in women who are, or may become, pregnant.) Individuals with known superinfection often benefit from antibiotic therapy, as well.

In this case, the patient had already undergone a tubal ligation for contraception. Therefore, she was started on acitretin 25 mg PO daily. Patients on systemic retinoids undergo laboratory surveillance for transaminitis and hypertriglyceridemia regularly. Adverse effects are generally well tolerated, but include photosensitivity and dry skin, lips, and eyes. The patient improved significantly on 25 mg/d and the dosage was reduced to 10 mg/d after 3 months. She currently remains clear on this regimen.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L. Palmoplantar pustulosis: recent advances in etiopathogenesis and emerging treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:355-370.

Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L. Palmoplantar pustulosis: recent advances in etiopathogenesis and emerging treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:355-370.

Purple toe lesion

An excisional biopsy revealed that this was an eccrine poroma, a benign neoplasm of sweat gland tissue in the epidermis.

This lesion was clearly not a wart, as it lacked the common verrucous and keratotic features one would expect, and it did not respond to wart treatments. Other diagnoses that might be considered with a lesion like this include pyogenic granuloma, periungual fibroma, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Poromas are well demarcated papules that grow slowly or are stable in size. They are most commonly flesh colored and smooth, but poromas may also appear verrucous, pigmented, or ulcerated. They are usually found on acral skin—particularly the palms or soles. Due to their location, poromas bleed easily, which is what usually prompts patients to seek care. Friable lesions can mimic acral melanoma.

Poromas occur most often in patients over 40 years of age and are evenly distributed among sexes and skin types. Cases have been associated with trauma, radiation, and chemotherapy. Although exceedingly rare, malignant transformation can occur in the form of eccrine porocarcinoma—a larger tumor that can grow rapidly and that has metastatic potential.

Treatment is optional—but desirable—when lesions are painful or bleed easily. Surgical excision is curative. Shave biopsy or curettage coupled with electrocautery of the base is also curative. Recurrence rates are very low with either method of treatment.

In this case, an excisional biopsy of the lateral nail fold was both diagnostic and curative (second image). The patient remained clear 9 months after treatment.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

An excisional biopsy revealed that this was an eccrine poroma, a benign neoplasm of sweat gland tissue in the epidermis.

This lesion was clearly not a wart, as it lacked the common verrucous and keratotic features one would expect, and it did not respond to wart treatments. Other diagnoses that might be considered with a lesion like this include pyogenic granuloma, periungual fibroma, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Poromas are well demarcated papules that grow slowly or are stable in size. They are most commonly flesh colored and smooth, but poromas may also appear verrucous, pigmented, or ulcerated. They are usually found on acral skin—particularly the palms or soles. Due to their location, poromas bleed easily, which is what usually prompts patients to seek care. Friable lesions can mimic acral melanoma.

Poromas occur most often in patients over 40 years of age and are evenly distributed among sexes and skin types. Cases have been associated with trauma, radiation, and chemotherapy. Although exceedingly rare, malignant transformation can occur in the form of eccrine porocarcinoma—a larger tumor that can grow rapidly and that has metastatic potential.

Treatment is optional—but desirable—when lesions are painful or bleed easily. Surgical excision is curative. Shave biopsy or curettage coupled with electrocautery of the base is also curative. Recurrence rates are very low with either method of treatment.

In this case, an excisional biopsy of the lateral nail fold was both diagnostic and curative (second image). The patient remained clear 9 months after treatment.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

An excisional biopsy revealed that this was an eccrine poroma, a benign neoplasm of sweat gland tissue in the epidermis.

This lesion was clearly not a wart, as it lacked the common verrucous and keratotic features one would expect, and it did not respond to wart treatments. Other diagnoses that might be considered with a lesion like this include pyogenic granuloma, periungual fibroma, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Poromas are well demarcated papules that grow slowly or are stable in size. They are most commonly flesh colored and smooth, but poromas may also appear verrucous, pigmented, or ulcerated. They are usually found on acral skin—particularly the palms or soles. Due to their location, poromas bleed easily, which is what usually prompts patients to seek care. Friable lesions can mimic acral melanoma.

Poromas occur most often in patients over 40 years of age and are evenly distributed among sexes and skin types. Cases have been associated with trauma, radiation, and chemotherapy. Although exceedingly rare, malignant transformation can occur in the form of eccrine porocarcinoma—a larger tumor that can grow rapidly and that has metastatic potential.

Treatment is optional—but desirable—when lesions are painful or bleed easily. Surgical excision is curative. Shave biopsy or curettage coupled with electrocautery of the base is also curative. Recurrence rates are very low with either method of treatment.

In this case, an excisional biopsy of the lateral nail fold was both diagnostic and curative (second image). The patient remained clear 9 months after treatment.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

Tiny papules on trunk and genitals

The miniscule papules arising suddenly on the trunk and genitals with linear arrays and clusters are clinically consistent with lichen nitidus, an uncommon eruption without a clear etiology.

Presentations may be focal or widespread and range from mildly itchy to asymptomatic. Children and young adults are most often affected. Linear arrays may appear in response to the trauma of scratching, which is termed the Koebner phenomenon. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, lichen planus, and lichen spinulosis. Usually these conditions can be distinguished clinically, but a biopsy would differentiate them, if needed. It’s worth noting, too, that lichen nitidus papules are monomorphic and lack the umbilication that is seen with molluscum contagiosum.

Cases of lichen nitidus clear up spontaneously, although usually months to years after diagnosis. Lichen nitidus is not contagious. Reassurance is, however, important as many patients may have experienced misdiagnosis and have concerns about sexual transmission because of the location of the papules on their genitals.

Treatment is often unnecessary. However, if itching is problematic, topical steroids and other topical antipruritics may be used. Topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment for skin folds and genitals may be safely used, as well as topical triamcinolone 0.1% for the trunk and extremities. Pramoxine lotion (Sarna) is an over-the-counter nonsteroidal antipruritic. Oral nonsedating antihistamines can also be used as an adjunct.

This patient was reassured that the lesions were not contagious. Due to the itching, he was started on the pramoxine lotion twice daily, as needed, and the lesions cleared in about 6 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160.

The miniscule papules arising suddenly on the trunk and genitals with linear arrays and clusters are clinically consistent with lichen nitidus, an uncommon eruption without a clear etiology.

Presentations may be focal or widespread and range from mildly itchy to asymptomatic. Children and young adults are most often affected. Linear arrays may appear in response to the trauma of scratching, which is termed the Koebner phenomenon. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, lichen planus, and lichen spinulosis. Usually these conditions can be distinguished clinically, but a biopsy would differentiate them, if needed. It’s worth noting, too, that lichen nitidus papules are monomorphic and lack the umbilication that is seen with molluscum contagiosum.

Cases of lichen nitidus clear up spontaneously, although usually months to years after diagnosis. Lichen nitidus is not contagious. Reassurance is, however, important as many patients may have experienced misdiagnosis and have concerns about sexual transmission because of the location of the papules on their genitals.

Treatment is often unnecessary. However, if itching is problematic, topical steroids and other topical antipruritics may be used. Topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment for skin folds and genitals may be safely used, as well as topical triamcinolone 0.1% for the trunk and extremities. Pramoxine lotion (Sarna) is an over-the-counter nonsteroidal antipruritic. Oral nonsedating antihistamines can also be used as an adjunct.

This patient was reassured that the lesions were not contagious. Due to the itching, he was started on the pramoxine lotion twice daily, as needed, and the lesions cleared in about 6 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The miniscule papules arising suddenly on the trunk and genitals with linear arrays and clusters are clinically consistent with lichen nitidus, an uncommon eruption without a clear etiology.

Presentations may be focal or widespread and range from mildly itchy to asymptomatic. Children and young adults are most often affected. Linear arrays may appear in response to the trauma of scratching, which is termed the Koebner phenomenon. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, lichen planus, and lichen spinulosis. Usually these conditions can be distinguished clinically, but a biopsy would differentiate them, if needed. It’s worth noting, too, that lichen nitidus papules are monomorphic and lack the umbilication that is seen with molluscum contagiosum.

Cases of lichen nitidus clear up spontaneously, although usually months to years after diagnosis. Lichen nitidus is not contagious. Reassurance is, however, important as many patients may have experienced misdiagnosis and have concerns about sexual transmission because of the location of the papules on their genitals.

Treatment is often unnecessary. However, if itching is problematic, topical steroids and other topical antipruritics may be used. Topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment for skin folds and genitals may be safely used, as well as topical triamcinolone 0.1% for the trunk and extremities. Pramoxine lotion (Sarna) is an over-the-counter nonsteroidal antipruritic. Oral nonsedating antihistamines can also be used as an adjunct.

This patient was reassured that the lesions were not contagious. Due to the itching, he was started on the pramoxine lotion twice daily, as needed, and the lesions cleared in about 6 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160.

Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160.

Increasing ear pain and headache

A previously healthy 12-year-old boy with normal development presented to his primary care physician (PCP) with a 1-week history of moderate ear pain. He was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM) and prescribed a 7-day course of amoxicillin. Although the child’s history was otherwise unremarkable, the mother reported that she’d had a deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism a year earlier.

The boy continued to experience intermittent left ear pain 2 weeks after completing his antibiotic treatment, leading the PCP to refer him to an otolaryngologist. An examination by the otolaryngologist revealed a cloudy, bulging tympanic membrane. The patient was prescribed amoxicillin/clavulanate and ofloxacin ear drops.

Two days later, he was admitted to the emergency department (ED) due to worsening left ear pain and a new-onset left-sided headache. His left tympanic membrane was normal, with no tenderness or erythema of the mastoid. His vital signs were normal. He was afebrile and discharged home.

A week later, he returned to the ED with worsening ear pain and severe persistent headache, which was localized in the left occipital, left frontal, and retro-orbital regions. He denied light or sound sensitivity, nausea, vomiting, or increased lacrimation. He was tearful on examination due to the pain. He had no meningismus and normal fundi. A neurologic examination was nonlateralizing. Laboratory tests showed a normal complete blood count but increased C-reactive protein at 113 mg/dL (normal, < 0.3 mg/dL) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 88 mm/hr (normal, 0-20 mm/hr).

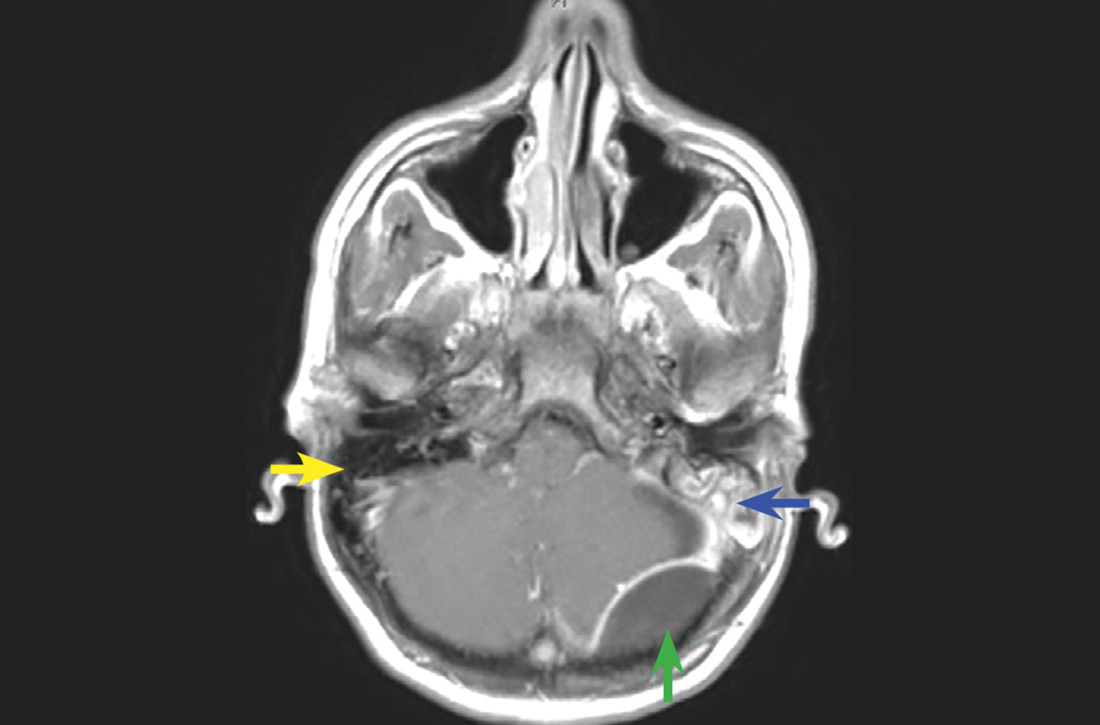

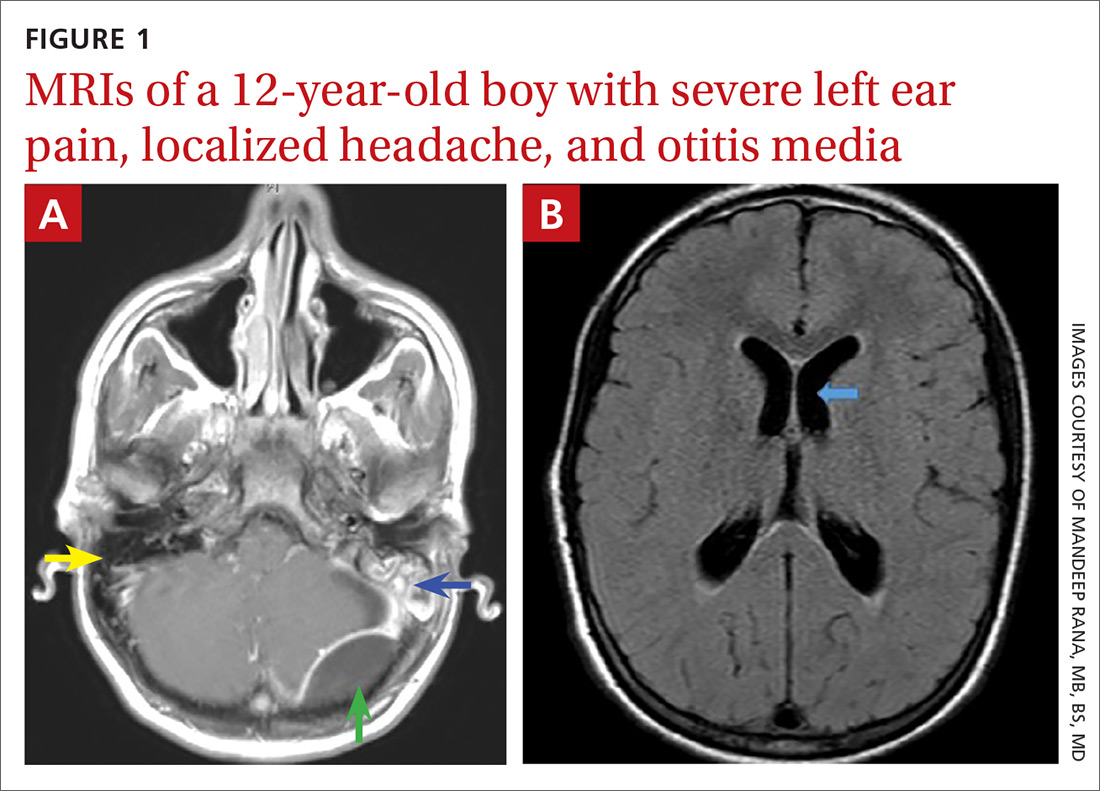

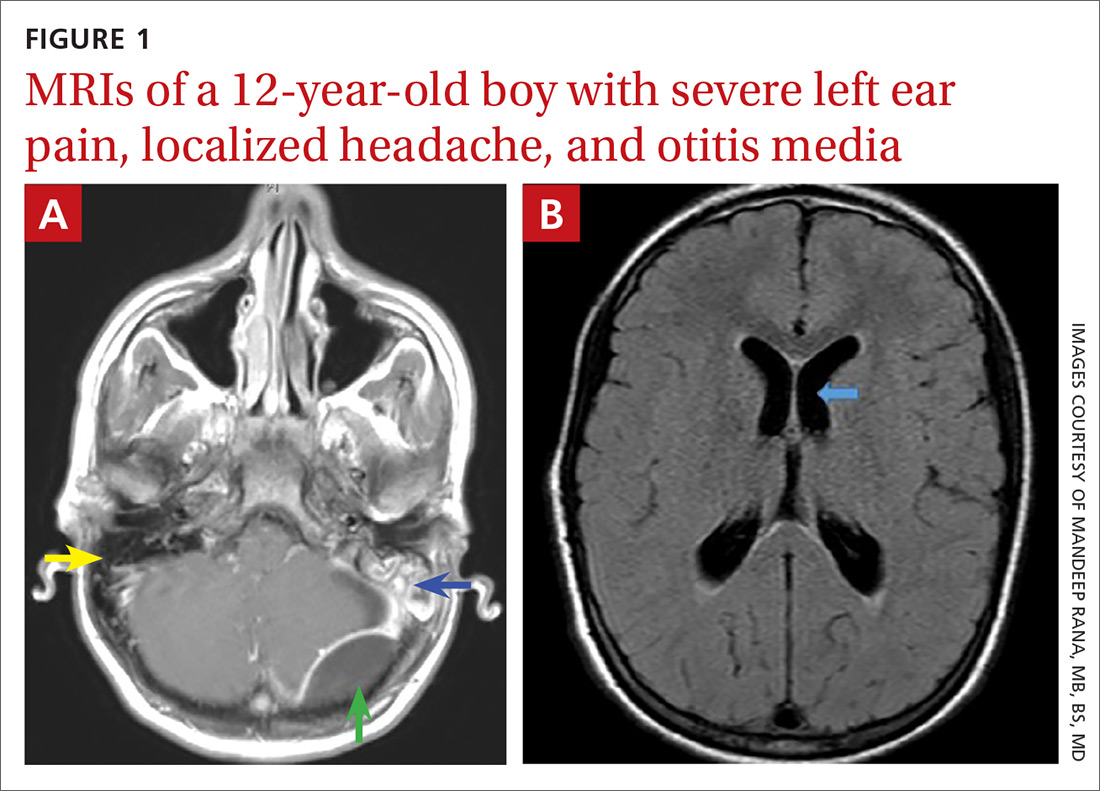

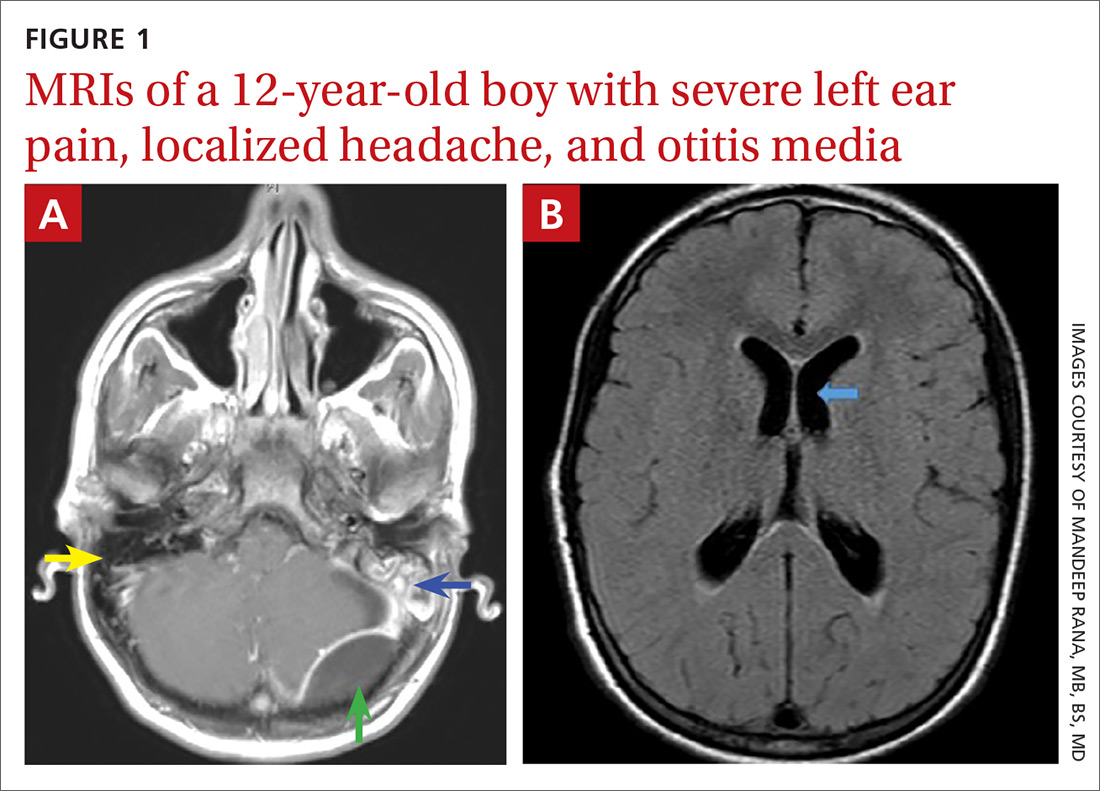

Magnetic resonance imaging was ordered (FIGURES 1A and 1B), and Neurosurgery and Otolaryngology were consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Acute mastoiditis with epidural abscess

The contrast-enhanced cranial MRI scan (FIGURE 1A) revealed a case of acute mastoiditis with fluid in the left mastoid (blue arrow) and a large epidural abscess in the left posterior fossa (green arrow). The normal right mastoid was air-filled (yellow arrow). The T2-weighted MRI scan (FIGURE 1B) showed mild dilatation of the lateral ventricles (blue arrow) secondary to compression on the fourth ventricle by mass effect from the epidural abscess.

Acute mastoiditis—a complication of AOM—is an inflammatory process of mastoid air cells, which are contiguous to the middle ear cleft. In one large study of 61,783 inpatient children admitted with AOM, acute mastoiditis was reported as the most common complication in 1505 (2.4%) of the cases.1 The 2000-2012 national estimated incidence rate of pediatric mastoiditis has ranged from a high of 2.7 per 100,000 population in 2006 to a low of 1.8 per 100,000 in 2012.2 Clinical features of mastoiditis include localized mastoid tenderness, swelling, erythema, fluctuance, protrusion of the auricle, and ear pain.3

The clinical presentation of epidural abscess can be subtle with fever, headache, neck pain, and changes in mental status developing over several days.1 Focal deficits and seizures are relatively uncommon. In a review of 308 children with acute mastoiditis (3 with an epidural abscess), high-grade fever and high absolute neutrophil count and C-reactive protein levels were associated with the development of complications of mastoiditis, including hearing loss, sinus venous thrombosis, intracranial abscess, and cranial nerve palsies.4

Venous sinus thrombosis was part of the differential

When we were caring for this patient, the differential diagnosis included a cranial extension of AOM. Venous sinus thrombosis was also considered, given the family history of a hypercoagulable state. The patient did not have any features suggesting primary headache syndromes, such as migraine, tension type, or cluster headache.

The differential for a patient complaining of ear pain also includes postauricular lymphadenopathy, mumps, periauricular cellulitis (with and without otitis externa), perichondritis of the auricle, and tumors involving the mastoid bone.4

Continue to: Imaging and treatment

Imaging and treatment

Imaging of temporal bone is not recommended to make a diagnosis of mastoiditis in children with characteristic clinical findings. When imaging is needed, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is best to help visualize changes in temporal bone. If intracranial complications are suspected, cranial MRI with contrast or cranial CT with contrast can be ordered (depending on availability).5

Conservative management with intravenous antimicrobial therapy and middle ear drainage with myringotomy is indicated for a child with uncomplicated acute or subacute mastoiditis. For patients with suppurative extracranial or intracranial complications, aggressive surgical management is needed.5

Treatment for this patient included craniotomy, evacuation of the epidural abscess, and mastoidectomy. A culture obtained from the abscess showed Streptococcus intermedius. He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, including ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and metronidazole. Within a week of surgery, he was discharged from the hospital and continued antibiotic treatment for 6 weeks via a peripherally inserted central catheter line.

1. Lavin JM, Rusher T, Shah RK. Complications of pediatric otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:366-370.

2. King LM, Bartoces M, Hersh AL, et al. National incidence of pediatric mastoiditis in the United States, 2000-2012: creating a baseline for public health surveillance. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:e14-e16.

3. Pang LH, Barakate MS, Havas TE. Mastoiditis in a paediatric population: a review of 11 years’ experience in management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1520.

4. Bilavsky E, Yarden-Bilavsky H, Samra Z, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and microbiological differences between children with simple or complicated mastoiditis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1270-1273.

5. Chesney J, Black A, Choo D. What is the best practice for acute mastoiditis in children? Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1057-1059.

A previously healthy 12-year-old boy with normal development presented to his primary care physician (PCP) with a 1-week history of moderate ear pain. He was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM) and prescribed a 7-day course of amoxicillin. Although the child’s history was otherwise unremarkable, the mother reported that she’d had a deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism a year earlier.

The boy continued to experience intermittent left ear pain 2 weeks after completing his antibiotic treatment, leading the PCP to refer him to an otolaryngologist. An examination by the otolaryngologist revealed a cloudy, bulging tympanic membrane. The patient was prescribed amoxicillin/clavulanate and ofloxacin ear drops.

Two days later, he was admitted to the emergency department (ED) due to worsening left ear pain and a new-onset left-sided headache. His left tympanic membrane was normal, with no tenderness or erythema of the mastoid. His vital signs were normal. He was afebrile and discharged home.

A week later, he returned to the ED with worsening ear pain and severe persistent headache, which was localized in the left occipital, left frontal, and retro-orbital regions. He denied light or sound sensitivity, nausea, vomiting, or increased lacrimation. He was tearful on examination due to the pain. He had no meningismus and normal fundi. A neurologic examination was nonlateralizing. Laboratory tests showed a normal complete blood count but increased C-reactive protein at 113 mg/dL (normal, < 0.3 mg/dL) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 88 mm/hr (normal, 0-20 mm/hr).

Magnetic resonance imaging was ordered (FIGURES 1A and 1B), and Neurosurgery and Otolaryngology were consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Acute mastoiditis with epidural abscess

The contrast-enhanced cranial MRI scan (FIGURE 1A) revealed a case of acute mastoiditis with fluid in the left mastoid (blue arrow) and a large epidural abscess in the left posterior fossa (green arrow). The normal right mastoid was air-filled (yellow arrow). The T2-weighted MRI scan (FIGURE 1B) showed mild dilatation of the lateral ventricles (blue arrow) secondary to compression on the fourth ventricle by mass effect from the epidural abscess.

Acute mastoiditis—a complication of AOM—is an inflammatory process of mastoid air cells, which are contiguous to the middle ear cleft. In one large study of 61,783 inpatient children admitted with AOM, acute mastoiditis was reported as the most common complication in 1505 (2.4%) of the cases.1 The 2000-2012 national estimated incidence rate of pediatric mastoiditis has ranged from a high of 2.7 per 100,000 population in 2006 to a low of 1.8 per 100,000 in 2012.2 Clinical features of mastoiditis include localized mastoid tenderness, swelling, erythema, fluctuance, protrusion of the auricle, and ear pain.3

The clinical presentation of epidural abscess can be subtle with fever, headache, neck pain, and changes in mental status developing over several days.1 Focal deficits and seizures are relatively uncommon. In a review of 308 children with acute mastoiditis (3 with an epidural abscess), high-grade fever and high absolute neutrophil count and C-reactive protein levels were associated with the development of complications of mastoiditis, including hearing loss, sinus venous thrombosis, intracranial abscess, and cranial nerve palsies.4

Venous sinus thrombosis was part of the differential

When we were caring for this patient, the differential diagnosis included a cranial extension of AOM. Venous sinus thrombosis was also considered, given the family history of a hypercoagulable state. The patient did not have any features suggesting primary headache syndromes, such as migraine, tension type, or cluster headache.

The differential for a patient complaining of ear pain also includes postauricular lymphadenopathy, mumps, periauricular cellulitis (with and without otitis externa), perichondritis of the auricle, and tumors involving the mastoid bone.4

Continue to: Imaging and treatment

Imaging and treatment

Imaging of temporal bone is not recommended to make a diagnosis of mastoiditis in children with characteristic clinical findings. When imaging is needed, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is best to help visualize changes in temporal bone. If intracranial complications are suspected, cranial MRI with contrast or cranial CT with contrast can be ordered (depending on availability).5

Conservative management with intravenous antimicrobial therapy and middle ear drainage with myringotomy is indicated for a child with uncomplicated acute or subacute mastoiditis. For patients with suppurative extracranial or intracranial complications, aggressive surgical management is needed.5

Treatment for this patient included craniotomy, evacuation of the epidural abscess, and mastoidectomy. A culture obtained from the abscess showed Streptococcus intermedius. He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, including ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and metronidazole. Within a week of surgery, he was discharged from the hospital and continued antibiotic treatment for 6 weeks via a peripherally inserted central catheter line.

A previously healthy 12-year-old boy with normal development presented to his primary care physician (PCP) with a 1-week history of moderate ear pain. He was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM) and prescribed a 7-day course of amoxicillin. Although the child’s history was otherwise unremarkable, the mother reported that she’d had a deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism a year earlier.

The boy continued to experience intermittent left ear pain 2 weeks after completing his antibiotic treatment, leading the PCP to refer him to an otolaryngologist. An examination by the otolaryngologist revealed a cloudy, bulging tympanic membrane. The patient was prescribed amoxicillin/clavulanate and ofloxacin ear drops.

Two days later, he was admitted to the emergency department (ED) due to worsening left ear pain and a new-onset left-sided headache. His left tympanic membrane was normal, with no tenderness or erythema of the mastoid. His vital signs were normal. He was afebrile and discharged home.

A week later, he returned to the ED with worsening ear pain and severe persistent headache, which was localized in the left occipital, left frontal, and retro-orbital regions. He denied light or sound sensitivity, nausea, vomiting, or increased lacrimation. He was tearful on examination due to the pain. He had no meningismus and normal fundi. A neurologic examination was nonlateralizing. Laboratory tests showed a normal complete blood count but increased C-reactive protein at 113 mg/dL (normal, < 0.3 mg/dL) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 88 mm/hr (normal, 0-20 mm/hr).

Magnetic resonance imaging was ordered (FIGURES 1A and 1B), and Neurosurgery and Otolaryngology were consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Acute mastoiditis with epidural abscess

The contrast-enhanced cranial MRI scan (FIGURE 1A) revealed a case of acute mastoiditis with fluid in the left mastoid (blue arrow) and a large epidural abscess in the left posterior fossa (green arrow). The normal right mastoid was air-filled (yellow arrow). The T2-weighted MRI scan (FIGURE 1B) showed mild dilatation of the lateral ventricles (blue arrow) secondary to compression on the fourth ventricle by mass effect from the epidural abscess.

Acute mastoiditis—a complication of AOM—is an inflammatory process of mastoid air cells, which are contiguous to the middle ear cleft. In one large study of 61,783 inpatient children admitted with AOM, acute mastoiditis was reported as the most common complication in 1505 (2.4%) of the cases.1 The 2000-2012 national estimated incidence rate of pediatric mastoiditis has ranged from a high of 2.7 per 100,000 population in 2006 to a low of 1.8 per 100,000 in 2012.2 Clinical features of mastoiditis include localized mastoid tenderness, swelling, erythema, fluctuance, protrusion of the auricle, and ear pain.3

The clinical presentation of epidural abscess can be subtle with fever, headache, neck pain, and changes in mental status developing over several days.1 Focal deficits and seizures are relatively uncommon. In a review of 308 children with acute mastoiditis (3 with an epidural abscess), high-grade fever and high absolute neutrophil count and C-reactive protein levels were associated with the development of complications of mastoiditis, including hearing loss, sinus venous thrombosis, intracranial abscess, and cranial nerve palsies.4

Venous sinus thrombosis was part of the differential

When we were caring for this patient, the differential diagnosis included a cranial extension of AOM. Venous sinus thrombosis was also considered, given the family history of a hypercoagulable state. The patient did not have any features suggesting primary headache syndromes, such as migraine, tension type, or cluster headache.

The differential for a patient complaining of ear pain also includes postauricular lymphadenopathy, mumps, periauricular cellulitis (with and without otitis externa), perichondritis of the auricle, and tumors involving the mastoid bone.4

Continue to: Imaging and treatment

Imaging and treatment

Imaging of temporal bone is not recommended to make a diagnosis of mastoiditis in children with characteristic clinical findings. When imaging is needed, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is best to help visualize changes in temporal bone. If intracranial complications are suspected, cranial MRI with contrast or cranial CT with contrast can be ordered (depending on availability).5

Conservative management with intravenous antimicrobial therapy and middle ear drainage with myringotomy is indicated for a child with uncomplicated acute or subacute mastoiditis. For patients with suppurative extracranial or intracranial complications, aggressive surgical management is needed.5

Treatment for this patient included craniotomy, evacuation of the epidural abscess, and mastoidectomy. A culture obtained from the abscess showed Streptococcus intermedius. He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, including ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and metronidazole. Within a week of surgery, he was discharged from the hospital and continued antibiotic treatment for 6 weeks via a peripherally inserted central catheter line.

1. Lavin JM, Rusher T, Shah RK. Complications of pediatric otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:366-370.

2. King LM, Bartoces M, Hersh AL, et al. National incidence of pediatric mastoiditis in the United States, 2000-2012: creating a baseline for public health surveillance. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:e14-e16.

3. Pang LH, Barakate MS, Havas TE. Mastoiditis in a paediatric population: a review of 11 years’ experience in management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1520.

4. Bilavsky E, Yarden-Bilavsky H, Samra Z, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and microbiological differences between children with simple or complicated mastoiditis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1270-1273.

5. Chesney J, Black A, Choo D. What is the best practice for acute mastoiditis in children? Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1057-1059.

1. Lavin JM, Rusher T, Shah RK. Complications of pediatric otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:366-370.

2. King LM, Bartoces M, Hersh AL, et al. National incidence of pediatric mastoiditis in the United States, 2000-2012: creating a baseline for public health surveillance. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:e14-e16.

3. Pang LH, Barakate MS, Havas TE. Mastoiditis in a paediatric population: a review of 11 years’ experience in management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1520.

4. Bilavsky E, Yarden-Bilavsky H, Samra Z, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and microbiological differences between children with simple or complicated mastoiditis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1270-1273.

5. Chesney J, Black A, Choo D. What is the best practice for acute mastoiditis in children? Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1057-1059.

Arcuate eruption on the back

A punch biopsy of the markedly erythematous lateral edge helped to confirm this as tumid lupus erythematosus (TLE), a rare subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. TLE occurs in men and women of all ages. Annular or arcuate patches and plaques most often arise on the face, trunk, extremities, and V of the neck after sun exposure. However, as in this case, plaques may appear in areas covered by clothing. Plaques generally do not itch or hurt, but their presence can be alarming.

Annular and arcuate plaques raise a complex differential diagnosis including common conditions such as urticaria and tinea corporis, as well as more uncommon disorders such as erythema annulare centrifugum and lymphoma cutis. Unlike tinea corporis and erythema annulare centrifugum, there is very little, if any, scaling of the superficial epidermis. Plaques heal without scarring or changes to skin pigmentation.

Multiple punch biopsies of affected areas are key to a proper diagnosis. Patients with confirmed TLE should undergo antinuclear antibody testing to rule out systemic lupus erythematosus, although the vast majority will have normal results.

Treatment includes potent or ultrapotent topical steroids for the trunk and extremities, and mid- to low-potency steroids for intertriginous areas or the face. Systemic immunomodulators with hydroxychloroquine are used as first-line treatment for more extensive disease.

In this case, the patient had a normal antinuclear antibody titer and was treated with topical betamethasone dipropionate augmented 0.05% cream bid for 2 weeks, which led to complete clearance. She experienced a flare-up a year later and was retreated with the same results.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033–1041.

A punch biopsy of the markedly erythematous lateral edge helped to confirm this as tumid lupus erythematosus (TLE), a rare subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. TLE occurs in men and women of all ages. Annular or arcuate patches and plaques most often arise on the face, trunk, extremities, and V of the neck after sun exposure. However, as in this case, plaques may appear in areas covered by clothing. Plaques generally do not itch or hurt, but their presence can be alarming.

Annular and arcuate plaques raise a complex differential diagnosis including common conditions such as urticaria and tinea corporis, as well as more uncommon disorders such as erythema annulare centrifugum and lymphoma cutis. Unlike tinea corporis and erythema annulare centrifugum, there is very little, if any, scaling of the superficial epidermis. Plaques heal without scarring or changes to skin pigmentation.

Multiple punch biopsies of affected areas are key to a proper diagnosis. Patients with confirmed TLE should undergo antinuclear antibody testing to rule out systemic lupus erythematosus, although the vast majority will have normal results.

Treatment includes potent or ultrapotent topical steroids for the trunk and extremities, and mid- to low-potency steroids for intertriginous areas or the face. Systemic immunomodulators with hydroxychloroquine are used as first-line treatment for more extensive disease.

In this case, the patient had a normal antinuclear antibody titer and was treated with topical betamethasone dipropionate augmented 0.05% cream bid for 2 weeks, which led to complete clearance. She experienced a flare-up a year later and was retreated with the same results.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

A punch biopsy of the markedly erythematous lateral edge helped to confirm this as tumid lupus erythematosus (TLE), a rare subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. TLE occurs in men and women of all ages. Annular or arcuate patches and plaques most often arise on the face, trunk, extremities, and V of the neck after sun exposure. However, as in this case, plaques may appear in areas covered by clothing. Plaques generally do not itch or hurt, but their presence can be alarming.

Annular and arcuate plaques raise a complex differential diagnosis including common conditions such as urticaria and tinea corporis, as well as more uncommon disorders such as erythema annulare centrifugum and lymphoma cutis. Unlike tinea corporis and erythema annulare centrifugum, there is very little, if any, scaling of the superficial epidermis. Plaques heal without scarring or changes to skin pigmentation.

Multiple punch biopsies of affected areas are key to a proper diagnosis. Patients with confirmed TLE should undergo antinuclear antibody testing to rule out systemic lupus erythematosus, although the vast majority will have normal results.

Treatment includes potent or ultrapotent topical steroids for the trunk and extremities, and mid- to low-potency steroids for intertriginous areas or the face. Systemic immunomodulators with hydroxychloroquine are used as first-line treatment for more extensive disease.

In this case, the patient had a normal antinuclear antibody titer and was treated with topical betamethasone dipropionate augmented 0.05% cream bid for 2 weeks, which led to complete clearance. She experienced a flare-up a year later and was retreated with the same results.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033–1041.

Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033–1041.

Pruritic rash on flank, back, and chest

The patient was given a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30. It more commonly is seen in people of Asian descent.

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most commonly occurs in association with diabetes, ketosis, and more recently with ketogenic diets. Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal.

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa such as urticaria, irritant contact dermatitis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, and pityriasis rosea.

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade. If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties. Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.

This patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

This case was adapted from: Croom D, Barlow T, Landers JT. Pruritic rash on chest and back. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:113-114,116

The patient was given a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30. It more commonly is seen in people of Asian descent.

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most commonly occurs in association with diabetes, ketosis, and more recently with ketogenic diets. Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal.

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa such as urticaria, irritant contact dermatitis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, and pityriasis rosea.

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade. If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties. Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.

This patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

This case was adapted from: Croom D, Barlow T, Landers JT. Pruritic rash on chest and back. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:113-114,116

The patient was given a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa based on the characteristic pruritic rash that had developed after the patient started a strict ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a benign, pruritic rash that most commonly presents with erythematous or hyperpigmented, symmetrically distributed urticarial papules and plaques on the chest and back. Females represent approximately 70% of cases with a predominant age range of 11 to 30. It more commonly is seen in people of Asian descent.

While the pathophysiology remains unknown, the rash most commonly occurs in association with diabetes, ketosis, and more recently with ketogenic diets. Despite occurring in only a fraction of patients on the ketogenic diet, the characteristic presentation has led to the alternative name of the “keto rash” in online nutritional forums and blogs.

The diagnosis is made clinically, so the appearance of a symmetric pruritic, hyperpigmented rash on the chest and back should prompt the physician to ask about any recent changes in diet. Laboratory analysis is unnecessary, as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and liver function panel are almost always normal.

Other conditions can mimic prurigo pigmentosa such as urticaria, irritant contact dermatitis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, and pityriasis rosea.

Primary treatment includes resumption of a normal diet. This often leads to rapid resolution of pruritis. Residual hyperpigmentation may take months to fade. If additional treatment is required, minocycline 100 to 200 mg/d has been reported most effective, likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties. Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines provide symptomatic relief in some patients.

This patient had resolution of the pruritis and urticarial lesions within 2 days of resuming a normal diet; however, residual asymptomatic hyperpigmentation persisted. A retrial of the ketogenic diet initiated a flare of the rash in the same distribution. It rapidly resolved with carbohydrate intake.

This case was adapted from: Croom D, Barlow T, Landers JT. Pruritic rash on chest and back. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:113-114,116

Eyebrow hair loss

Although it appeared that the hair loss was preceded by some dry skin, the patch of hair loss was smooth and nonscarring, consistent with a diagnosis of alopecia areata (AA).

AA typically is found on the scalp in solitary areas but can affect the whole body, including the eyelashes and eyebrows. Affected hair typically is narrower at the proximal end, resembling an exclamation point, as the hair fails to grow and falls out. Sometimes, patches of alopecia may coalesce into a larger area. Nail changes may be noted, as well. Nails may become brittle, with pitting and/or longitudinal ridges. Patients are usually asymptomatic but may complain of pruritus.

AA is believed to be an autoimmune disorder. It affects males and females of all ages but is more common in children and young adults. AA is believed to result from a T-cell–mediated immune response that transitions the hair follicles from the growth phase to the resting phase. This leads to sudden hair loss and inhibition of regrowth of the hair. However, the hair follicle is not permanently destroyed as in other processes of alopecia. There is also an association between AA and other autoimmune disorders such as vitiligo, thyroid disease, and lupus.

The diagnosis usually is made clinically, as in this patient, but a definitive diagnosis can be made by biopsy and pathology. Other differential diagnoses to consider are trichotillomania, tinea, traumatic alopecia, and lupus.

In almost half of cases, AA is self-resolving; therefore, in first episodes of localized disease, watchful waiting is appropriate. Treatment is tailored to the individual patient and may be difficult. Intralesional corticosteroids often are used for mild cases. Typically, 10 mg/mL of a glucocorticoid is injected into the mid-dermis every 4 to 6 weeks; however, this treatment carries a risk of transient or even permanent atrophy of the injection site. Potent topical corticosteroids often are used, especially in children who do not tolerate intralesional injections, and success can be variable. Other topical treatments to consider are photochemotherapy (psoralen plus UVA), or an irritant agent such as anthralin and a vasodilator such as minoxidil. Regrowth can be expected in a few months to a year, but recurrence is common.

Image courtesy of Stacy Nguy, MD, and text courtesy of Stacy Nguy, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Papadopoulos AJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger C. Alopecia areata: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:101-105

Although it appeared that the hair loss was preceded by some dry skin, the patch of hair loss was smooth and nonscarring, consistent with a diagnosis of alopecia areata (AA).

AA typically is found on the scalp in solitary areas but can affect the whole body, including the eyelashes and eyebrows. Affected hair typically is narrower at the proximal end, resembling an exclamation point, as the hair fails to grow and falls out. Sometimes, patches of alopecia may coalesce into a larger area. Nail changes may be noted, as well. Nails may become brittle, with pitting and/or longitudinal ridges. Patients are usually asymptomatic but may complain of pruritus.

AA is believed to be an autoimmune disorder. It affects males and females of all ages but is more common in children and young adults. AA is believed to result from a T-cell–mediated immune response that transitions the hair follicles from the growth phase to the resting phase. This leads to sudden hair loss and inhibition of regrowth of the hair. However, the hair follicle is not permanently destroyed as in other processes of alopecia. There is also an association between AA and other autoimmune disorders such as vitiligo, thyroid disease, and lupus.

The diagnosis usually is made clinically, as in this patient, but a definitive diagnosis can be made by biopsy and pathology. Other differential diagnoses to consider are trichotillomania, tinea, traumatic alopecia, and lupus.

In almost half of cases, AA is self-resolving; therefore, in first episodes of localized disease, watchful waiting is appropriate. Treatment is tailored to the individual patient and may be difficult. Intralesional corticosteroids often are used for mild cases. Typically, 10 mg/mL of a glucocorticoid is injected into the mid-dermis every 4 to 6 weeks; however, this treatment carries a risk of transient or even permanent atrophy of the injection site. Potent topical corticosteroids often are used, especially in children who do not tolerate intralesional injections, and success can be variable. Other topical treatments to consider are photochemotherapy (psoralen plus UVA), or an irritant agent such as anthralin and a vasodilator such as minoxidil. Regrowth can be expected in a few months to a year, but recurrence is common.

Image courtesy of Stacy Nguy, MD, and text courtesy of Stacy Nguy, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Although it appeared that the hair loss was preceded by some dry skin, the patch of hair loss was smooth and nonscarring, consistent with a diagnosis of alopecia areata (AA).

AA typically is found on the scalp in solitary areas but can affect the whole body, including the eyelashes and eyebrows. Affected hair typically is narrower at the proximal end, resembling an exclamation point, as the hair fails to grow and falls out. Sometimes, patches of alopecia may coalesce into a larger area. Nail changes may be noted, as well. Nails may become brittle, with pitting and/or longitudinal ridges. Patients are usually asymptomatic but may complain of pruritus.

AA is believed to be an autoimmune disorder. It affects males and females of all ages but is more common in children and young adults. AA is believed to result from a T-cell–mediated immune response that transitions the hair follicles from the growth phase to the resting phase. This leads to sudden hair loss and inhibition of regrowth of the hair. However, the hair follicle is not permanently destroyed as in other processes of alopecia. There is also an association between AA and other autoimmune disorders such as vitiligo, thyroid disease, and lupus.

The diagnosis usually is made clinically, as in this patient, but a definitive diagnosis can be made by biopsy and pathology. Other differential diagnoses to consider are trichotillomania, tinea, traumatic alopecia, and lupus.

In almost half of cases, AA is self-resolving; therefore, in first episodes of localized disease, watchful waiting is appropriate. Treatment is tailored to the individual patient and may be difficult. Intralesional corticosteroids often are used for mild cases. Typically, 10 mg/mL of a glucocorticoid is injected into the mid-dermis every 4 to 6 weeks; however, this treatment carries a risk of transient or even permanent atrophy of the injection site. Potent topical corticosteroids often are used, especially in children who do not tolerate intralesional injections, and success can be variable. Other topical treatments to consider are photochemotherapy (psoralen plus UVA), or an irritant agent such as anthralin and a vasodilator such as minoxidil. Regrowth can be expected in a few months to a year, but recurrence is common.

Image courtesy of Stacy Nguy, MD, and text courtesy of Stacy Nguy, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Papadopoulos AJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger C. Alopecia areata: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:101-105

Papadopoulos AJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger C. Alopecia areata: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:101-105

Rapidly developing vesicular eruption

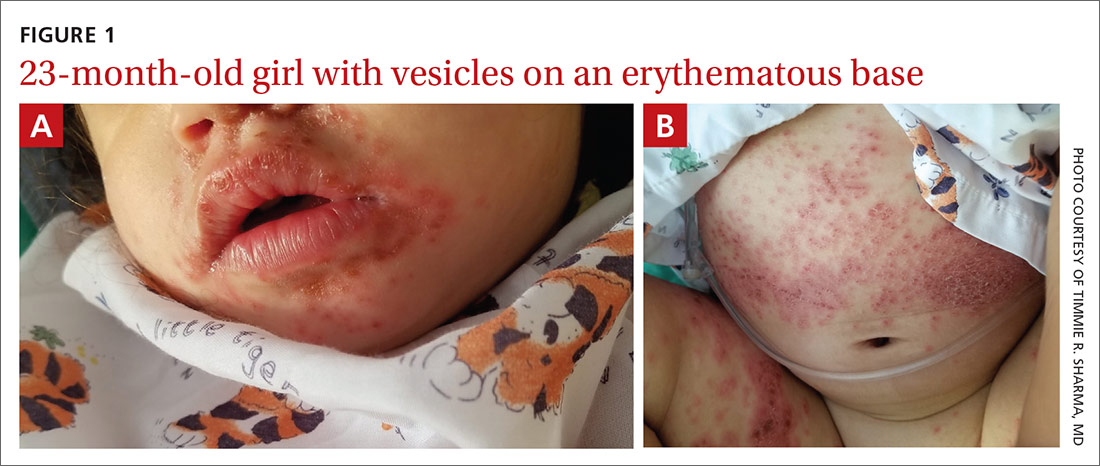

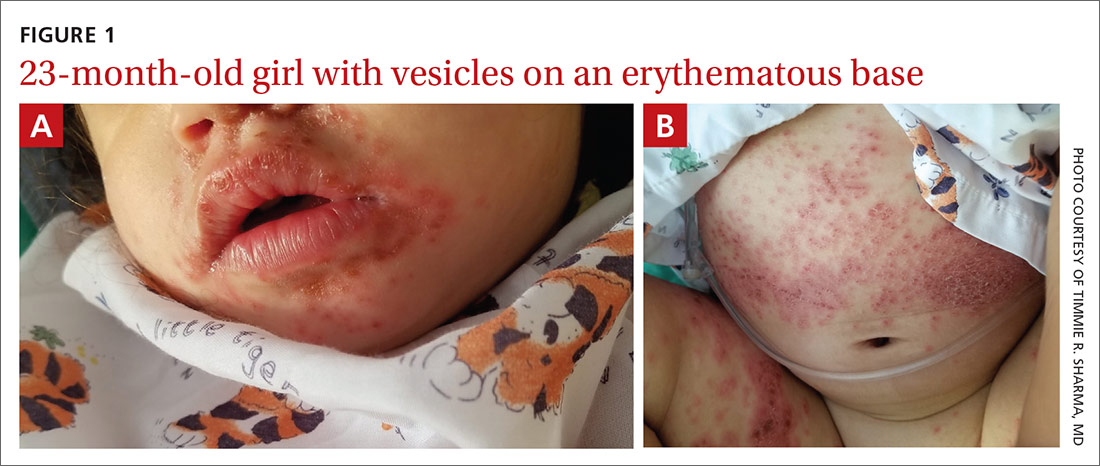

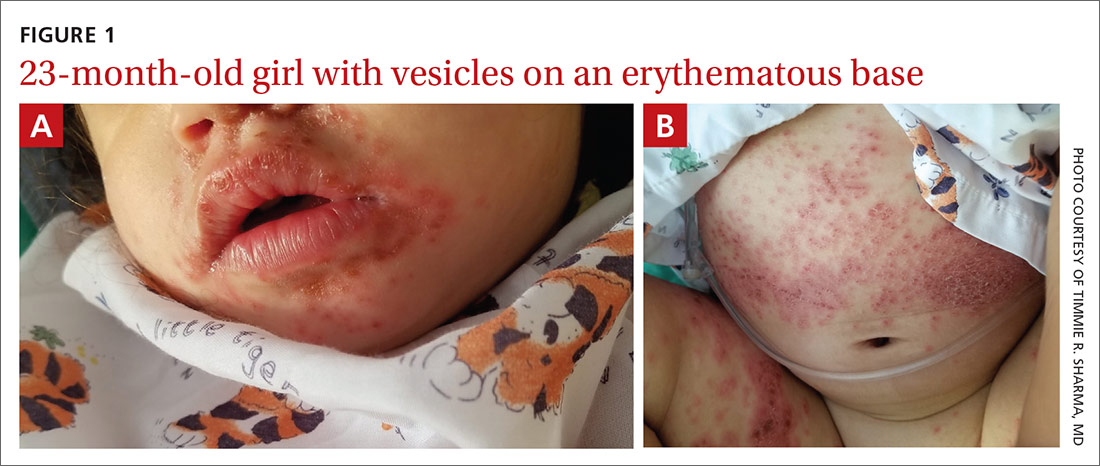

A 23-month-old girl with a history of well-controlled atopic dermatitis was admitted to the hospital with fever and a widespread vesicular eruption of 2 days’ duration. Two days prior to admission, the patient had 3 episodes of nonbloody diarrhea and redness in the diaper area. The child’s parents reported that the red areas spread to her arms and legs later that day, and that she subsequently developed a fever, cough, and rhinorrhea. She was taken to an urgent care facility where she was diagnosed with vulvovaginitis and an upper respiratory infection; amoxicillin was prescribed. Shortly thereafter, the patient developed more lesions in and around the mouth, as well as on the trunk, prompting the parents to bring her to the emergency department.

The history revealed that the patient had spent time with her aunt and cousins who had “red spots” on their palms and soles. The patient’s sister had a flare of “cold sores,” about 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. The patient had received a varicella zoster virus (VZV) vaccine several months earlier.

Physical examination was notable for an uncomfortable infant with erythematous macules on the bilateral palms and soles and an erythematous hard palate. The child also had scattered vesicles on an erythematous base with confluent crusted plaques on her lips, perioral skin (FIGURE 1A), abdomen, back, buttocks, arms, legs (FIGURE 1B), and dorsal aspects of her hands and feet.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema coxsackium

Given the history of atopic dermatitis; prodromal diarrhea/rhinorrhea; papulovesicular eruption involving areas of prior dermatitis as well as the palms, soles, and mouth; recent contacts with suspected hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD); and history of VZV vaccination, the favored diagnosis was eczema coxsackium.

Eczema coxsackium is an atypical form of HFMD that occurs in patients with a history of eczema. Classic HFMD usually is caused by coxsackievirus A16 or enterovirus 71, while atypical HFMD often is caused by coxsackievirus A6.1,2,3 Patients with HFMD present with painful oral vesicles and ulcers and a papulovesicular eruption on the palms, soles, and sometimes the buttocks and genitalia. Patients may have prodromal fever, fussiness, and diarrhea. Painful oral lesions may result in poor oral intake.1,2

Differential includes viral eruptions

Other conditions may manifest similarly to eczema coxsackium and must be ruled out before initiating proper treatment.

Eczema herpeticum (EH). In atypical HFMD, the virus can show tropism for active or previously inflamed areas of eczematous skin, leading to a widespread vesicular eruption, which can be difficult to distinguish from EH.1 Similar to EH, eczema coxsackium does not exclusively affect children with atopic dermatitis. It also has been described in adults and patients with Darier disease, incontinentia pigmenti, and epidermolytic ichthyosis.4-6

In cases of vesicular eruptions in eczema patients, it is imperative to rule out EH. One prospective study of atypical HFMD compared similarities of the conditions. Both have a predilection for mucosa during primary infection and develop vesicular eruptions on cutaneous eczematous skin.1 One key difference between eczema coxsackium and EH is that EH tends to produce intraoral vesicles beyond simple erythema; it also tends to predominate in the area of the head and neck.7

Continue to: Eczema varicellicum

Eczema varicellicum has been reported, and it has been suggested that some cases of EH may actually be caused by VZV as the 2 are clinically indistinguishable and less than half of EH cases are diagnosed with laboratory confirmation.8

Confirm Dx before you treat

To guide management, cases of suspected eczema coxsackium should be confirmed, and HSV/VZV should be ruled out.9 Testing modalities include swabbing vesicular fluid for enterovirus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis (preferred modality), oropharyngeal swab up to 2 weeks after infection, or viral isolate from stool samples up to 3 months after infection.2,3

Treatment for eczema coxsackium involves supportive care such as intravenous (IV) hydration and antipyretics. Some studies show potential benefit with IV immunoglobulin in treating severe HFMD, while other studies show the exacerbation of widespread HFMD with this treatment.7,10

Prompt diagnosis and treatment for eczema coxsackium is critical to prevent unnecessary antiviral therapy and to help guide monitoring for associated morbidities including Gianotti-Crosti syndrome–like eruptions, purpuric eruptions, and onychomadesis.

Our patient. Because EH was in the differential, our patient was started on empiric IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours while test results were pending. In addition, she received acetaminophen, IV fluids, gentle sponge baths, and diligent emollient application. Scraping from a vesicle revealed negative herpes simplex virus 1/2 PCR, negative VZV direct fluorescent antibody, and a positive enterovirus PCR—confirming the diagnosis of eczema coxsackium. Interestingly, a viral culture was negative in our patient, consistent with prior reports of enterovirus being difficult to culture.11

With confirmation of the diagnosis of eczema coxsackium, the IV acyclovir was discontinued, and symptoms resolved after 7 days.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shane M. Swink, DO, MS, Division of Dermatology, 1200 South Cedar Crest Boulevard, Allentown, PA 18103; [email protected]

1. Neri I, Dondi A, Wollenberg A, et al. Atypical forms of hand, foot, and mouth disease: a prospective study of 47 Italian children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:429-437.

2. Nassef C, Ziemer C, Morrell DS. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease: a new look at a classic viral rash. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27:486-491.

3. Horsten H, Fisker N, Bygu, A. Eczema coxsackium caused by coxsackievirus A6. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:230-231.

4. Jefferson J, Grossberg A. Incontinentia pigmenti coxsackium. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E280-E281.

5. Ganguly S, Kuruvila S. Eczema coxsackium. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:682-683.

6. Harris P, Wang AD, Yin M, et al. Atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease: eczema coxsackium can also occur in adults. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1043.

7. Wollenberg A, Zoch C, Wetzel S, et al. Predisposing factors and clinical features of eczema herpeticum: a retrospective analysis of 100 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:198-205.

8. Austin TA, Steele RW. Eczema varicella/zoster (varicellicum). Clin Pediatr. 2017;56:579-581.

9. Leung DYM. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98:153-157.

10. Cao RY, Dong DY, Liu RJ, et al. Human IgG subclasses against enterovirus type 71: neutralization versus antibody dependent enhancement of infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:E64024.

11. Mathes EF, Oza V, Frieden IJ, et al. Eczema coxsackium and unusual cutaneous findings in an enterovirus outbreak. Pediatrics. 2013;132:149-157.

A 23-month-old girl with a history of well-controlled atopic dermatitis was admitted to the hospital with fever and a widespread vesicular eruption of 2 days’ duration. Two days prior to admission, the patient had 3 episodes of nonbloody diarrhea and redness in the diaper area. The child’s parents reported that the red areas spread to her arms and legs later that day, and that she subsequently developed a fever, cough, and rhinorrhea. She was taken to an urgent care facility where she was diagnosed with vulvovaginitis and an upper respiratory infection; amoxicillin was prescribed. Shortly thereafter, the patient developed more lesions in and around the mouth, as well as on the trunk, prompting the parents to bring her to the emergency department.

The history revealed that the patient had spent time with her aunt and cousins who had “red spots” on their palms and soles. The patient’s sister had a flare of “cold sores,” about 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. The patient had received a varicella zoster virus (VZV) vaccine several months earlier.

Physical examination was notable for an uncomfortable infant with erythematous macules on the bilateral palms and soles and an erythematous hard palate. The child also had scattered vesicles on an erythematous base with confluent crusted plaques on her lips, perioral skin (FIGURE 1A), abdomen, back, buttocks, arms, legs (FIGURE 1B), and dorsal aspects of her hands and feet.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Eczema coxsackium

Given the history of atopic dermatitis; prodromal diarrhea/rhinorrhea; papulovesicular eruption involving areas of prior dermatitis as well as the palms, soles, and mouth; recent contacts with suspected hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD); and history of VZV vaccination, the favored diagnosis was eczema coxsackium.

Eczema coxsackium is an atypical form of HFMD that occurs in patients with a history of eczema. Classic HFMD usually is caused by coxsackievirus A16 or enterovirus 71, while atypical HFMD often is caused by coxsackievirus A6.1,2,3 Patients with HFMD present with painful oral vesicles and ulcers and a papulovesicular eruption on the palms, soles, and sometimes the buttocks and genitalia. Patients may have prodromal fever, fussiness, and diarrhea. Painful oral lesions may result in poor oral intake.1,2

Differential includes viral eruptions

Other conditions may manifest similarly to eczema coxsackium and must be ruled out before initiating proper treatment.

Eczema herpeticum (EH). In atypical HFMD, the virus can show tropism for active or previously inflamed areas of eczematous skin, leading to a widespread vesicular eruption, which can be difficult to distinguish from EH.1 Similar to EH, eczema coxsackium does not exclusively affect children with atopic dermatitis. It also has been described in adults and patients with Darier disease, incontinentia pigmenti, and epidermolytic ichthyosis.4-6

In cases of vesicular eruptions in eczema patients, it is imperative to rule out EH. One prospective study of atypical HFMD compared similarities of the conditions. Both have a predilection for mucosa during primary infection and develop vesicular eruptions on cutaneous eczematous skin.1 One key difference between eczema coxsackium and EH is that EH tends to produce intraoral vesicles beyond simple erythema; it also tends to predominate in the area of the head and neck.7

Continue to: Eczema varicellicum

Eczema varicellicum has been reported, and it has been suggested that some cases of EH may actually be caused by VZV as the 2 are clinically indistinguishable and less than half of EH cases are diagnosed with laboratory confirmation.8

Confirm Dx before you treat

To guide management, cases of suspected eczema coxsackium should be confirmed, and HSV/VZV should be ruled out.9 Testing modalities include swabbing vesicular fluid for enterovirus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis (preferred modality), oropharyngeal swab up to 2 weeks after infection, or viral isolate from stool samples up to 3 months after infection.2,3

Treatment for eczema coxsackium involves supportive care such as intravenous (IV) hydration and antipyretics. Some studies show potential benefit with IV immunoglobulin in treating severe HFMD, while other studies show the exacerbation of widespread HFMD with this treatment.7,10

Prompt diagnosis and treatment for eczema coxsackium is critical to prevent unnecessary antiviral therapy and to help guide monitoring for associated morbidities including Gianotti-Crosti syndrome–like eruptions, purpuric eruptions, and onychomadesis.

Our patient. Because EH was in the differential, our patient was started on empiric IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours while test results were pending. In addition, she received acetaminophen, IV fluids, gentle sponge baths, and diligent emollient application. Scraping from a vesicle revealed negative herpes simplex virus 1/2 PCR, negative VZV direct fluorescent antibody, and a positive enterovirus PCR—confirming the diagnosis of eczema coxsackium. Interestingly, a viral culture was negative in our patient, consistent with prior reports of enterovirus being difficult to culture.11

With confirmation of the diagnosis of eczema coxsackium, the IV acyclovir was discontinued, and symptoms resolved after 7 days.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shane M. Swink, DO, MS, Division of Dermatology, 1200 South Cedar Crest Boulevard, Allentown, PA 18103; [email protected]