User login

Brown spot on ear

The FP explained to the patient that this could be a skin cancer—specifically, a melanoma.

The FP performed a broad shave biopsy, being careful not to cut into the cartilage. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP did his best to include most of the pigmented area involved, but the convex surface made it difficult to biopsy the whole lesion. He was especially careful to include the darker area because it looked most atypical. The diagnosis came back as lentigo maligna.

The patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. (Mohs surgery is recommended to spare tissue and maximize cure.) After complete excision, the patient learned that the melanoma was not invasive, but in situ. This suggested a very good prognosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP explained to the patient that this could be a skin cancer—specifically, a melanoma.

The FP performed a broad shave biopsy, being careful not to cut into the cartilage. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP did his best to include most of the pigmented area involved, but the convex surface made it difficult to biopsy the whole lesion. He was especially careful to include the darker area because it looked most atypical. The diagnosis came back as lentigo maligna.

The patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. (Mohs surgery is recommended to spare tissue and maximize cure.) After complete excision, the patient learned that the melanoma was not invasive, but in situ. This suggested a very good prognosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP explained to the patient that this could be a skin cancer—specifically, a melanoma.

The FP performed a broad shave biopsy, being careful not to cut into the cartilage. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP did his best to include most of the pigmented area involved, but the convex surface made it difficult to biopsy the whole lesion. He was especially careful to include the darker area because it looked most atypical. The diagnosis came back as lentigo maligna.

The patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. (Mohs surgery is recommended to spare tissue and maximize cure.) After complete excision, the patient learned that the melanoma was not invasive, but in situ. This suggested a very good prognosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growing spot on face

The FP suspected melanoma and recommended immediate biopsy. The patient consented, and the physician performed a broad shave biopsy that included most of the pigmented lesion. Pathology revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.3 mm.

Lentigo maligna melanoma occurs in 4% to 15% of cutaneous melanomas. It’s similar to the superficial spreading type and appears as a flat (or mildly elevated) mottled tan, brown, or dark-brown discoloration. This type of melanoma is found most often in the elderly and arises on chronically sun-exposed, damaged skin on the face, ears, arms, and upper trunk. The average age of onset is 65 years and it grows slowly over 5 to 20 years.

When melanoma is suspected, it’s best to provide a specimen with adequate depth and breadth. Unfortunately, choosing the darkest and most raised area does not guarantee the correct diagnosis in a partial biopsy.

In cases of suspected lentigo maligna melanoma on the face, a broad shave provides a better sample than a punch biopsy. The broad shave biopsy (also known as saucerization) is best performed with a razor blade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

In this case, the relatively small size of the lesion and the high risk for melanoma would make an elliptical excisional biopsy a good alternative. The saucerization has the advantage of being quick and easy to perform so that it can be done on the day that the melanoma is suspected.

This patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was not indicated, and the prognosis for this stage Ia melanoma was relatively good.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected melanoma and recommended immediate biopsy. The patient consented, and the physician performed a broad shave biopsy that included most of the pigmented lesion. Pathology revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.3 mm.

Lentigo maligna melanoma occurs in 4% to 15% of cutaneous melanomas. It’s similar to the superficial spreading type and appears as a flat (or mildly elevated) mottled tan, brown, or dark-brown discoloration. This type of melanoma is found most often in the elderly and arises on chronically sun-exposed, damaged skin on the face, ears, arms, and upper trunk. The average age of onset is 65 years and it grows slowly over 5 to 20 years.

When melanoma is suspected, it’s best to provide a specimen with adequate depth and breadth. Unfortunately, choosing the darkest and most raised area does not guarantee the correct diagnosis in a partial biopsy.

In cases of suspected lentigo maligna melanoma on the face, a broad shave provides a better sample than a punch biopsy. The broad shave biopsy (also known as saucerization) is best performed with a razor blade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

In this case, the relatively small size of the lesion and the high risk for melanoma would make an elliptical excisional biopsy a good alternative. The saucerization has the advantage of being quick and easy to perform so that it can be done on the day that the melanoma is suspected.

This patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was not indicated, and the prognosis for this stage Ia melanoma was relatively good.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected melanoma and recommended immediate biopsy. The patient consented, and the physician performed a broad shave biopsy that included most of the pigmented lesion. Pathology revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.3 mm.

Lentigo maligna melanoma occurs in 4% to 15% of cutaneous melanomas. It’s similar to the superficial spreading type and appears as a flat (or mildly elevated) mottled tan, brown, or dark-brown discoloration. This type of melanoma is found most often in the elderly and arises on chronically sun-exposed, damaged skin on the face, ears, arms, and upper trunk. The average age of onset is 65 years and it grows slowly over 5 to 20 years.

When melanoma is suspected, it’s best to provide a specimen with adequate depth and breadth. Unfortunately, choosing the darkest and most raised area does not guarantee the correct diagnosis in a partial biopsy.

In cases of suspected lentigo maligna melanoma on the face, a broad shave provides a better sample than a punch biopsy. The broad shave biopsy (also known as saucerization) is best performed with a razor blade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

In this case, the relatively small size of the lesion and the high risk for melanoma would make an elliptical excisional biopsy a good alternative. The saucerization has the advantage of being quick and easy to perform so that it can be done on the day that the melanoma is suspected.

This patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was not indicated, and the prognosis for this stage Ia melanoma was relatively good.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Painful facial blisters, fever, and conjunctivitis

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, hypothyroidism, and peripheral neuropathy presented to our clinic with left ear pain and blisters on her lips, nose, and mouth. On exam, the patient’s left tympanic membrane was opaque, and she had multiple 3- to 5-mm irregularly shaped ulcers on her right buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. She was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media and prescribed a course of amoxicillin. The physician, who was uncertain about the cause of her gingivostomatitis, took a “shotgun approach” and prescribed a nystatin/diphenhydramine/lidocaine mouthwash.

Three weeks later, the patient returned complaining of cloudy urine, dysuria, fever, vomiting, and “pink eye.” On exam, her right eye was mildly injected with no drainage. She had normal eye movements and no ophthalmoplegia. We diagnosed viral (vs allergic) conjunctivitis and pyelonephritis in this patient and advised her to use lubricant eyedrops and an oral antihistamine for the eye. We also started her on cefpodoxime (200 mg bid for 10 days) for pyelonephritis.

Three days later, the patient called our clinic and said that her right eye was not improving. We prescribed ofloxacin ophthalmic drops, 1 to 2 drops every 6 hours, for presumed bacterial conjunctivitis.

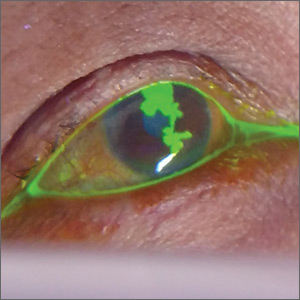

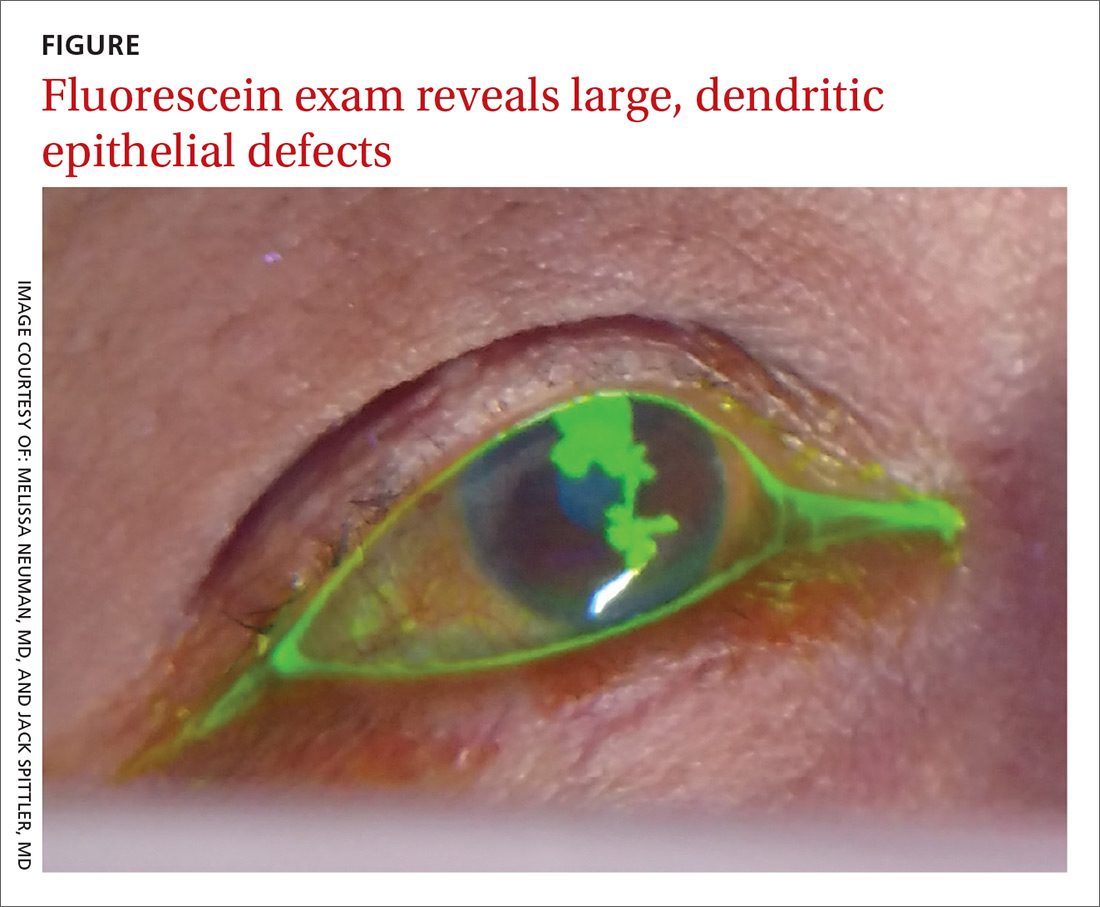

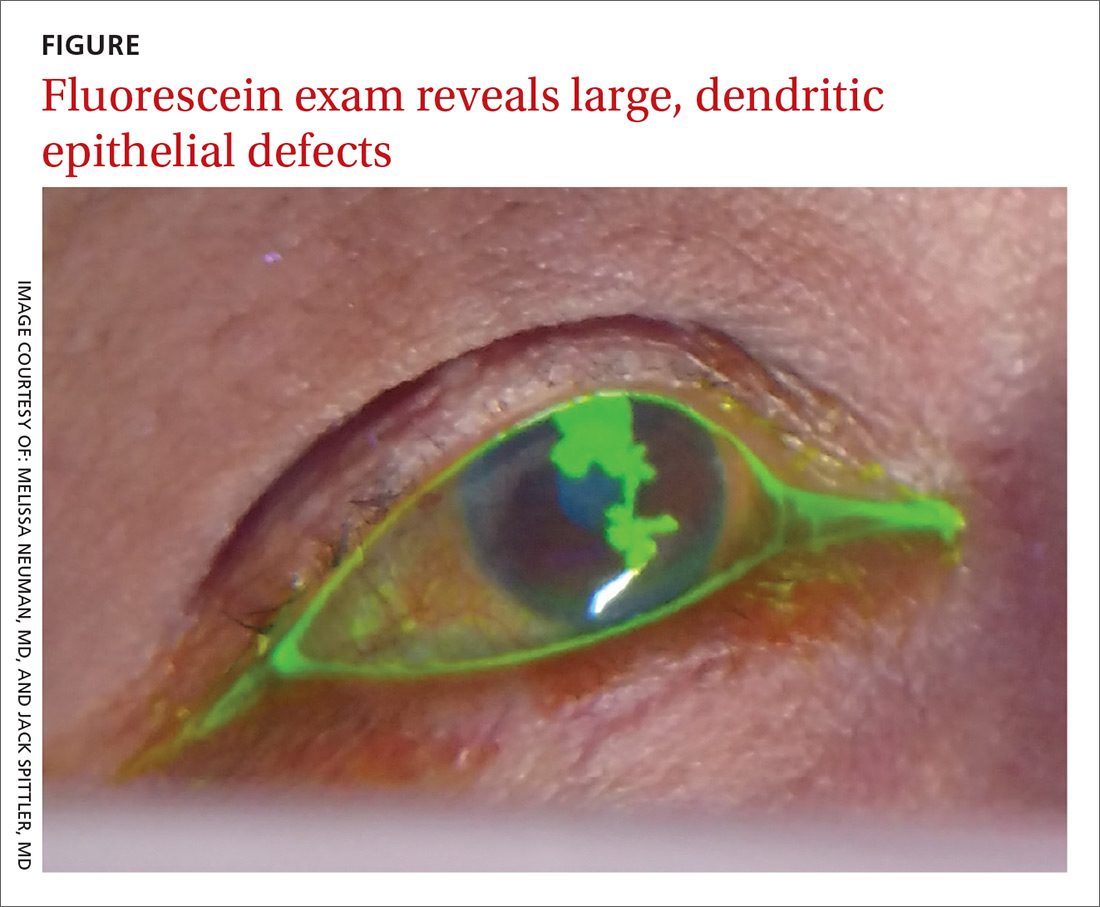

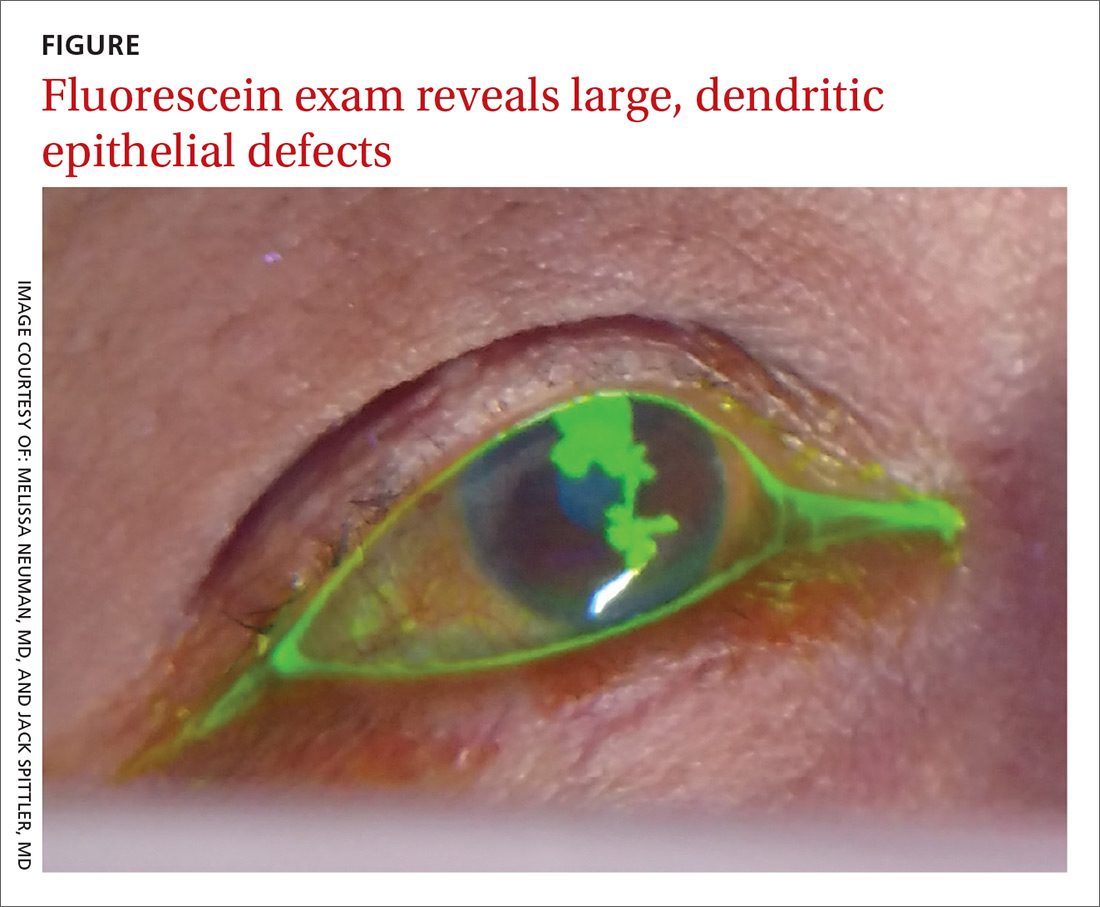

Four days later, she returned to our clinic; she had been using the ofloxacin drops and antihistamine but was experiencing worsening symptoms, including itching of her right eye, associated blurriness, and decreased vision. She had been using a warm compress on the eye and found that it was getting sticky and crusted. A gray corneal opacity was seen on physical exam, and a fluorescein exam was performed (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes simplex virus keratitis

The patient was sent to the ophthalmology clinic, where a slit-lamp examination of the right eye showed 3+ injection, large dendritic epithelial defects spanning the majority of the cornea (with 10% haze), and trace nuclear sclerosis of the lens. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, with a likely neurotrophic component (decreased sensation of the affected eye compared with that of the other eye). There was no evidence of secondary infection.

Discussion

The global incidence of HSV keratitis is approximately 1.5 million, including 40,000 new cases of monocular visual impairment or blindness each year.1 Primary infection with HSV-1 occurs following direct contact with infected mucosa or skin surfaces and inoculation. (Our patient likely transferred the infection by touching her eyes after touching her nose or mouth.) The virus remains in sensory ganglia for the lifetime of the host. Most ocular disease is thought to represent recurrent HSV (rather than a primary ocular infection).2 It has been proposed that HSV-1 latency may also occur in the cornea.

The symptoms of HSV keratitis include eye pain, redness, blurred vision, tearing, discharge, and sensitivity to light.

The 4 diagnostic categories

There are 4 categories of HSV keratitis, based on the location of the infection: epithelial, stromal, endotheliitis, and neurotrophic keratopathy.

Epithelial. The most common form, epithelial HSV manifests as dendritic or geographic lesions of the cornea.3 Geographic lesions occur when a dendrite widens and assumes an amoeboid shape.

Continue to: Stromal

Stromal. Stromal involvement accounts for 20% to 25% of presentations4 and may cause significant anterior chamber inflammation. Vision loss can result from permanent stromal scarring.5

Endotheliitis. Keratic precipitates (on top of stromal and epithelial edema) and a mild-to-moderate iritis are signs of endotheliitis.5

Neurotrophic keratopathy. This form of HSV keratitis is associated with corneal hypoesthesia or complete anesthesia secondary to damage of the corneal nerves, which can occur in any form of ocular HSV. Anesthesia may lead to nonhealing corneal epithelial defects.6 These defects, which are generally oval lesions, do not represent active viral disease and are made worse by antiviral drops. These lesions may cause stromal scarring, corneal perforation, or secondary bacterial infection.

Treatment consists of supportive care using artificial tears and prophylactic antibiotic eye drops, if appropriate; more advanced ophthalmologic treatments may be needed for advanced disease.7

Continue to: Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

The differential for redness of the eye includes conditions such as conjunctivitis, glaucoma, and keratitis.

Conjunctivitis of any form—bacterial, viral, allergic, or toxic—involves injection of both the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva.

Acute angle closure glaucoma can involve symptoms of headache, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. In addition, the pupil is fixed in mid-dilation, and the cornea becomes hazy.

Anterior uveitis/iritis causes sensitivity to light in both the affected and unaffected eyes, as well as ciliary flush (a red ring around the iris). Typically, there is no eye discharge.

Bacterial keratitis causes foreign body sensation and purulent discharge. This form of keratitis usually occurs due to improper wear of contact lenses.

Continue to: Viral keratitis...

Viral keratitis is characterized by photophobia, foreign body sensation, and watery discharge. A faint branching grey opacity may be seen on penlight exam, and dendrites may be seen with fluorescein.

Scleritis involves severe, boring pain of the eye in addition to photophobia and headache. It is usually associated with systemic inflammatory disorders.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is asymptomatic and occurs following trauma.

Cellulitis manifests following trauma with a deep violet color and marked edema.

Continue to: Standard Tx

Standard Tx: Antiviral medications

Topical antiviral therapy is the standard treatment for epithelial HSV keratitis, although oral antiviral medications are equally effective. A randomized trial found that using an oral agent in addition to a topical antiviral did not improve outcomes.8 A 2015 systematic review found that topical antivirals acyclovir, ganciclovir, brivudine, trifluridine were equally effective in treatment outcome; 90% of patients healed within 2 weeks.9

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infections are treated in the same way as the initial infection. Recurrent infection can be prevented with daily suppressive therapy. In one study, patients who took suppressive therapy (acyclovir 400 mg bid) for 1 year had 19% recurrence of ocular infection vs 32% in the placebo group.10

Prompt Tx is key. If the infection is superficial—involving only the outer layer of the cornea (epithelium)—the eye should heal without scarring with proper treatment. However, if the infection is not promptly treated or if deeper layers are involved, scarring of the cornea may occur. This can lead to vision loss or blindness.

Continue to: A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

This case highlights the importance of conducting a thorough exam to identify findings that could shift the diagnosis from a simple allergic, viral, or bacterial conjunctivitis. It is always better to consider primary oral HSV infection than resort to a “shotgun approach” of treating candida and pain with an oral mixture. In this case, the ulcers and vesicles on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips were a missed sign of primary HSV infection. Making this diagnosis might have prevented the ocular disease, as the treatment would have been an oral antiviral.

If conjunctivitis is refractory to usual management, the patient must be seen to rule out dangerous eye diagnoses such as HSV keratitis, preseptal or orbital cellulitis, or in the worst case, acute angle closure glaucoma. If there is uncertainty regarding diagnosis, a fluorescein exam is helpful. This simple in-office exam can facilitate a referral to Ophthalmology or the emergency department for a slit-lamp exam and appropriate therapy.

Our patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g bid, trifluridine eyedrops (5×/d), and erythromycin ophthalmic ointment (3×/d), with Ophthalmology follow-up in 1 week.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Spittler, MD, 3055 Roslyn St, Suite 100, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448-462.

2. Holland EJ, Mahanti RL, Belongia EA, et al. Ocular involvement in an outbreak of herpes gladiatorum. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:680-684.

3. Cook SD. Herpes simplex virus in the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:365-366.

4. Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1-13.

5. Sekar Babu M, Balammal G, Sangeetha G, et al. A review on viral keratitis caused by herpes simplex virus. J Sci. 2011;1:1-10.

6. Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1930-1936.

7. Bonini S, Rama P, Olzi D, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. Eye. 2003;17:989-995.

8. Szentmáry N, Módis L, Imre L, et al. Diagnostics and treatment of infectious keratitis. Orv Hetil. 2017;158:1203-1212.

9. Wilhelmus KR. Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD002898.

10. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:300-306.

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, hypothyroidism, and peripheral neuropathy presented to our clinic with left ear pain and blisters on her lips, nose, and mouth. On exam, the patient’s left tympanic membrane was opaque, and she had multiple 3- to 5-mm irregularly shaped ulcers on her right buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. She was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media and prescribed a course of amoxicillin. The physician, who was uncertain about the cause of her gingivostomatitis, took a “shotgun approach” and prescribed a nystatin/diphenhydramine/lidocaine mouthwash.

Three weeks later, the patient returned complaining of cloudy urine, dysuria, fever, vomiting, and “pink eye.” On exam, her right eye was mildly injected with no drainage. She had normal eye movements and no ophthalmoplegia. We diagnosed viral (vs allergic) conjunctivitis and pyelonephritis in this patient and advised her to use lubricant eyedrops and an oral antihistamine for the eye. We also started her on cefpodoxime (200 mg bid for 10 days) for pyelonephritis.

Three days later, the patient called our clinic and said that her right eye was not improving. We prescribed ofloxacin ophthalmic drops, 1 to 2 drops every 6 hours, for presumed bacterial conjunctivitis.

Four days later, she returned to our clinic; she had been using the ofloxacin drops and antihistamine but was experiencing worsening symptoms, including itching of her right eye, associated blurriness, and decreased vision. She had been using a warm compress on the eye and found that it was getting sticky and crusted. A gray corneal opacity was seen on physical exam, and a fluorescein exam was performed (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes simplex virus keratitis

The patient was sent to the ophthalmology clinic, where a slit-lamp examination of the right eye showed 3+ injection, large dendritic epithelial defects spanning the majority of the cornea (with 10% haze), and trace nuclear sclerosis of the lens. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, with a likely neurotrophic component (decreased sensation of the affected eye compared with that of the other eye). There was no evidence of secondary infection.

Discussion

The global incidence of HSV keratitis is approximately 1.5 million, including 40,000 new cases of monocular visual impairment or blindness each year.1 Primary infection with HSV-1 occurs following direct contact with infected mucosa or skin surfaces and inoculation. (Our patient likely transferred the infection by touching her eyes after touching her nose or mouth.) The virus remains in sensory ganglia for the lifetime of the host. Most ocular disease is thought to represent recurrent HSV (rather than a primary ocular infection).2 It has been proposed that HSV-1 latency may also occur in the cornea.

The symptoms of HSV keratitis include eye pain, redness, blurred vision, tearing, discharge, and sensitivity to light.

The 4 diagnostic categories

There are 4 categories of HSV keratitis, based on the location of the infection: epithelial, stromal, endotheliitis, and neurotrophic keratopathy.

Epithelial. The most common form, epithelial HSV manifests as dendritic or geographic lesions of the cornea.3 Geographic lesions occur when a dendrite widens and assumes an amoeboid shape.

Continue to: Stromal

Stromal. Stromal involvement accounts for 20% to 25% of presentations4 and may cause significant anterior chamber inflammation. Vision loss can result from permanent stromal scarring.5

Endotheliitis. Keratic precipitates (on top of stromal and epithelial edema) and a mild-to-moderate iritis are signs of endotheliitis.5

Neurotrophic keratopathy. This form of HSV keratitis is associated with corneal hypoesthesia or complete anesthesia secondary to damage of the corneal nerves, which can occur in any form of ocular HSV. Anesthesia may lead to nonhealing corneal epithelial defects.6 These defects, which are generally oval lesions, do not represent active viral disease and are made worse by antiviral drops. These lesions may cause stromal scarring, corneal perforation, or secondary bacterial infection.

Treatment consists of supportive care using artificial tears and prophylactic antibiotic eye drops, if appropriate; more advanced ophthalmologic treatments may be needed for advanced disease.7

Continue to: Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

The differential for redness of the eye includes conditions such as conjunctivitis, glaucoma, and keratitis.

Conjunctivitis of any form—bacterial, viral, allergic, or toxic—involves injection of both the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva.

Acute angle closure glaucoma can involve symptoms of headache, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. In addition, the pupil is fixed in mid-dilation, and the cornea becomes hazy.

Anterior uveitis/iritis causes sensitivity to light in both the affected and unaffected eyes, as well as ciliary flush (a red ring around the iris). Typically, there is no eye discharge.

Bacterial keratitis causes foreign body sensation and purulent discharge. This form of keratitis usually occurs due to improper wear of contact lenses.

Continue to: Viral keratitis...

Viral keratitis is characterized by photophobia, foreign body sensation, and watery discharge. A faint branching grey opacity may be seen on penlight exam, and dendrites may be seen with fluorescein.

Scleritis involves severe, boring pain of the eye in addition to photophobia and headache. It is usually associated with systemic inflammatory disorders.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is asymptomatic and occurs following trauma.

Cellulitis manifests following trauma with a deep violet color and marked edema.

Continue to: Standard Tx

Standard Tx: Antiviral medications

Topical antiviral therapy is the standard treatment for epithelial HSV keratitis, although oral antiviral medications are equally effective. A randomized trial found that using an oral agent in addition to a topical antiviral did not improve outcomes.8 A 2015 systematic review found that topical antivirals acyclovir, ganciclovir, brivudine, trifluridine were equally effective in treatment outcome; 90% of patients healed within 2 weeks.9

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infections are treated in the same way as the initial infection. Recurrent infection can be prevented with daily suppressive therapy. In one study, patients who took suppressive therapy (acyclovir 400 mg bid) for 1 year had 19% recurrence of ocular infection vs 32% in the placebo group.10

Prompt Tx is key. If the infection is superficial—involving only the outer layer of the cornea (epithelium)—the eye should heal without scarring with proper treatment. However, if the infection is not promptly treated or if deeper layers are involved, scarring of the cornea may occur. This can lead to vision loss or blindness.

Continue to: A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

This case highlights the importance of conducting a thorough exam to identify findings that could shift the diagnosis from a simple allergic, viral, or bacterial conjunctivitis. It is always better to consider primary oral HSV infection than resort to a “shotgun approach” of treating candida and pain with an oral mixture. In this case, the ulcers and vesicles on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips were a missed sign of primary HSV infection. Making this diagnosis might have prevented the ocular disease, as the treatment would have been an oral antiviral.

If conjunctivitis is refractory to usual management, the patient must be seen to rule out dangerous eye diagnoses such as HSV keratitis, preseptal or orbital cellulitis, or in the worst case, acute angle closure glaucoma. If there is uncertainty regarding diagnosis, a fluorescein exam is helpful. This simple in-office exam can facilitate a referral to Ophthalmology or the emergency department for a slit-lamp exam and appropriate therapy.

Our patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g bid, trifluridine eyedrops (5×/d), and erythromycin ophthalmic ointment (3×/d), with Ophthalmology follow-up in 1 week.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Spittler, MD, 3055 Roslyn St, Suite 100, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, hypothyroidism, and peripheral neuropathy presented to our clinic with left ear pain and blisters on her lips, nose, and mouth. On exam, the patient’s left tympanic membrane was opaque, and she had multiple 3- to 5-mm irregularly shaped ulcers on her right buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. She was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media and prescribed a course of amoxicillin. The physician, who was uncertain about the cause of her gingivostomatitis, took a “shotgun approach” and prescribed a nystatin/diphenhydramine/lidocaine mouthwash.

Three weeks later, the patient returned complaining of cloudy urine, dysuria, fever, vomiting, and “pink eye.” On exam, her right eye was mildly injected with no drainage. She had normal eye movements and no ophthalmoplegia. We diagnosed viral (vs allergic) conjunctivitis and pyelonephritis in this patient and advised her to use lubricant eyedrops and an oral antihistamine for the eye. We also started her on cefpodoxime (200 mg bid for 10 days) for pyelonephritis.

Three days later, the patient called our clinic and said that her right eye was not improving. We prescribed ofloxacin ophthalmic drops, 1 to 2 drops every 6 hours, for presumed bacterial conjunctivitis.

Four days later, she returned to our clinic; she had been using the ofloxacin drops and antihistamine but was experiencing worsening symptoms, including itching of her right eye, associated blurriness, and decreased vision. She had been using a warm compress on the eye and found that it was getting sticky and crusted. A gray corneal opacity was seen on physical exam, and a fluorescein exam was performed (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes simplex virus keratitis

The patient was sent to the ophthalmology clinic, where a slit-lamp examination of the right eye showed 3+ injection, large dendritic epithelial defects spanning the majority of the cornea (with 10% haze), and trace nuclear sclerosis of the lens. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, with a likely neurotrophic component (decreased sensation of the affected eye compared with that of the other eye). There was no evidence of secondary infection.

Discussion

The global incidence of HSV keratitis is approximately 1.5 million, including 40,000 new cases of monocular visual impairment or blindness each year.1 Primary infection with HSV-1 occurs following direct contact with infected mucosa or skin surfaces and inoculation. (Our patient likely transferred the infection by touching her eyes after touching her nose or mouth.) The virus remains in sensory ganglia for the lifetime of the host. Most ocular disease is thought to represent recurrent HSV (rather than a primary ocular infection).2 It has been proposed that HSV-1 latency may also occur in the cornea.

The symptoms of HSV keratitis include eye pain, redness, blurred vision, tearing, discharge, and sensitivity to light.

The 4 diagnostic categories

There are 4 categories of HSV keratitis, based on the location of the infection: epithelial, stromal, endotheliitis, and neurotrophic keratopathy.

Epithelial. The most common form, epithelial HSV manifests as dendritic or geographic lesions of the cornea.3 Geographic lesions occur when a dendrite widens and assumes an amoeboid shape.

Continue to: Stromal

Stromal. Stromal involvement accounts for 20% to 25% of presentations4 and may cause significant anterior chamber inflammation. Vision loss can result from permanent stromal scarring.5

Endotheliitis. Keratic precipitates (on top of stromal and epithelial edema) and a mild-to-moderate iritis are signs of endotheliitis.5

Neurotrophic keratopathy. This form of HSV keratitis is associated with corneal hypoesthesia or complete anesthesia secondary to damage of the corneal nerves, which can occur in any form of ocular HSV. Anesthesia may lead to nonhealing corneal epithelial defects.6 These defects, which are generally oval lesions, do not represent active viral disease and are made worse by antiviral drops. These lesions may cause stromal scarring, corneal perforation, or secondary bacterial infection.

Treatment consists of supportive care using artificial tears and prophylactic antibiotic eye drops, if appropriate; more advanced ophthalmologic treatments may be needed for advanced disease.7

Continue to: Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

The differential for redness of the eye includes conditions such as conjunctivitis, glaucoma, and keratitis.

Conjunctivitis of any form—bacterial, viral, allergic, or toxic—involves injection of both the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva.

Acute angle closure glaucoma can involve symptoms of headache, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. In addition, the pupil is fixed in mid-dilation, and the cornea becomes hazy.

Anterior uveitis/iritis causes sensitivity to light in both the affected and unaffected eyes, as well as ciliary flush (a red ring around the iris). Typically, there is no eye discharge.

Bacterial keratitis causes foreign body sensation and purulent discharge. This form of keratitis usually occurs due to improper wear of contact lenses.

Continue to: Viral keratitis...

Viral keratitis is characterized by photophobia, foreign body sensation, and watery discharge. A faint branching grey opacity may be seen on penlight exam, and dendrites may be seen with fluorescein.

Scleritis involves severe, boring pain of the eye in addition to photophobia and headache. It is usually associated with systemic inflammatory disorders.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is asymptomatic and occurs following trauma.

Cellulitis manifests following trauma with a deep violet color and marked edema.

Continue to: Standard Tx

Standard Tx: Antiviral medications

Topical antiviral therapy is the standard treatment for epithelial HSV keratitis, although oral antiviral medications are equally effective. A randomized trial found that using an oral agent in addition to a topical antiviral did not improve outcomes.8 A 2015 systematic review found that topical antivirals acyclovir, ganciclovir, brivudine, trifluridine were equally effective in treatment outcome; 90% of patients healed within 2 weeks.9

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infections are treated in the same way as the initial infection. Recurrent infection can be prevented with daily suppressive therapy. In one study, patients who took suppressive therapy (acyclovir 400 mg bid) for 1 year had 19% recurrence of ocular infection vs 32% in the placebo group.10

Prompt Tx is key. If the infection is superficial—involving only the outer layer of the cornea (epithelium)—the eye should heal without scarring with proper treatment. However, if the infection is not promptly treated or if deeper layers are involved, scarring of the cornea may occur. This can lead to vision loss or blindness.

Continue to: A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

This case highlights the importance of conducting a thorough exam to identify findings that could shift the diagnosis from a simple allergic, viral, or bacterial conjunctivitis. It is always better to consider primary oral HSV infection than resort to a “shotgun approach” of treating candida and pain with an oral mixture. In this case, the ulcers and vesicles on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips were a missed sign of primary HSV infection. Making this diagnosis might have prevented the ocular disease, as the treatment would have been an oral antiviral.

If conjunctivitis is refractory to usual management, the patient must be seen to rule out dangerous eye diagnoses such as HSV keratitis, preseptal or orbital cellulitis, or in the worst case, acute angle closure glaucoma. If there is uncertainty regarding diagnosis, a fluorescein exam is helpful. This simple in-office exam can facilitate a referral to Ophthalmology or the emergency department for a slit-lamp exam and appropriate therapy.

Our patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g bid, trifluridine eyedrops (5×/d), and erythromycin ophthalmic ointment (3×/d), with Ophthalmology follow-up in 1 week.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Spittler, MD, 3055 Roslyn St, Suite 100, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448-462.

2. Holland EJ, Mahanti RL, Belongia EA, et al. Ocular involvement in an outbreak of herpes gladiatorum. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:680-684.

3. Cook SD. Herpes simplex virus in the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:365-366.

4. Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1-13.

5. Sekar Babu M, Balammal G, Sangeetha G, et al. A review on viral keratitis caused by herpes simplex virus. J Sci. 2011;1:1-10.

6. Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1930-1936.

7. Bonini S, Rama P, Olzi D, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. Eye. 2003;17:989-995.

8. Szentmáry N, Módis L, Imre L, et al. Diagnostics and treatment of infectious keratitis. Orv Hetil. 2017;158:1203-1212.

9. Wilhelmus KR. Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD002898.

10. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:300-306.

1. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448-462.

2. Holland EJ, Mahanti RL, Belongia EA, et al. Ocular involvement in an outbreak of herpes gladiatorum. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:680-684.

3. Cook SD. Herpes simplex virus in the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:365-366.

4. Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1-13.

5. Sekar Babu M, Balammal G, Sangeetha G, et al. A review on viral keratitis caused by herpes simplex virus. J Sci. 2011;1:1-10.

6. Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1930-1936.

7. Bonini S, Rama P, Olzi D, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. Eye. 2003;17:989-995.

8. Szentmáry N, Módis L, Imre L, et al. Diagnostics and treatment of infectious keratitis. Orv Hetil. 2017;158:1203-1212.

9. Wilhelmus KR. Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD002898.

10. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:300-306.

Linear streaks on trunk, extremities

Based on the clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with flagellate shiitake mushroom dermatitis. (Subsequent treponemal and nontreponemal tests were negative for syphilis.)

Shiitake dermatitis is a rare disease that appears in susceptible patients after the consumption of large amounts of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms. The eruption is believed to be attributable to either a toxic or hypersensitivity reaction to lentinan, a polysaccharide component found within the mushroom cell wall.1 Shiitake dermatitis is self-limiting and treatment focuses on symptomatic management.

Early recognition and proper counseling should ensure symptomatic relief and prevent future episodes. In addition, anyone preparing shiitake mushrooms should make sure that they are fully cooked before serving or eating them.2

In the case described here, the patient was advised to avoid eating undercooked shiitake mushrooms in the future and he was prescribed topical steroids (mometasone furoate 0.1% cream). The eruption resolved 2 weeks later.

References

1. Nguyen AH, Gonzaga MI, Lim VM, et al. Clinical features of shiitake dermatitis: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:610-616.

2. Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

Based on the clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with flagellate shiitake mushroom dermatitis. (Subsequent treponemal and nontreponemal tests were negative for syphilis.)

Shiitake dermatitis is a rare disease that appears in susceptible patients after the consumption of large amounts of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms. The eruption is believed to be attributable to either a toxic or hypersensitivity reaction to lentinan, a polysaccharide component found within the mushroom cell wall.1 Shiitake dermatitis is self-limiting and treatment focuses on symptomatic management.

Early recognition and proper counseling should ensure symptomatic relief and prevent future episodes. In addition, anyone preparing shiitake mushrooms should make sure that they are fully cooked before serving or eating them.2

In the case described here, the patient was advised to avoid eating undercooked shiitake mushrooms in the future and he was prescribed topical steroids (mometasone furoate 0.1% cream). The eruption resolved 2 weeks later.

References

1. Nguyen AH, Gonzaga MI, Lim VM, et al. Clinical features of shiitake dermatitis: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:610-616.

2. Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

Based on the clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with flagellate shiitake mushroom dermatitis. (Subsequent treponemal and nontreponemal tests were negative for syphilis.)

Shiitake dermatitis is a rare disease that appears in susceptible patients after the consumption of large amounts of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms. The eruption is believed to be attributable to either a toxic or hypersensitivity reaction to lentinan, a polysaccharide component found within the mushroom cell wall.1 Shiitake dermatitis is self-limiting and treatment focuses on symptomatic management.

Early recognition and proper counseling should ensure symptomatic relief and prevent future episodes. In addition, anyone preparing shiitake mushrooms should make sure that they are fully cooked before serving or eating them.2

In the case described here, the patient was advised to avoid eating undercooked shiitake mushrooms in the future and he was prescribed topical steroids (mometasone furoate 0.1% cream). The eruption resolved 2 weeks later.

References

1. Nguyen AH, Gonzaga MI, Lim VM, et al. Clinical features of shiitake dermatitis: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:610-616.

2. Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

Rapid-onset rash in child

A 7-year-old boy was brought to his family physician for evaluation of a mildly pruritic spreading rash. Ten days earlier, the skin eruption had appeared, and he was given a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis, which was confirmed by a throat swab and a positive antistreptolysin O titer. The child had no personal or family history of skin disorders, including eczema or psoriasis. He hadn’t used any topical agents or new medications recently, nor had he been exposed to triggering plants, animals, or chemicals. There was no history of trauma, friction, or rubbing in the area.

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, scaly papules and plaques of varying size on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE). His palms and soles were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Guttate psoriasis

A diagnosis of guttate psoriasis was made based on the physical exam findings and the preceding group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection.

This condition affects approximately 2% of all patients with psoriasis; it is characterized by the acute onset of multiple erythematosquamous papules and small plaques that look like droplets (“gutta”).1 It tends to affect children and young adults and typically occurs following an acute infection (eg, streptococcal pharyngitis).2,3 In this case, a rapid strep test and throat culture positive for group A Streptococcus supported the diagnosis.

Although this particular phenotype of psoriasis is usually associated with streptococcal infection and mainly occurs in patients with the HLA-Cw6+ allele, the specific immunologic response that causes these skin lesions is poorly understood.4 Antigenic similarities between streptococcal proteins and keratinocyte antigens might explain why the condition is triggered by streptococcal infections.5

Pityriasis rosea and tinea corporis are part of the differential

The differential includes skin conditions such as pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis, varicella, and insect bites.

Pityriasis rosea can manifest as a papulosquamous eruption, but it has an inward-facing scale, called a collarette. The “Christmas tree” pattern on the back that is preceded by a solitary 2- to 10-cm oval, pink, scaly herald patch (in 17%-50% of cases) is key to the diagnosis.6 (For more information, see “Rash on trunk and upper arms.”)

Continue to: Tinea corporis...

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection that causes flat, red, scaly lesions that progress into annular lesions with central clearing or brown discoloration. The plaques can range from a few centimeters to several inches in size, but are always characterized by the slowly advancing border.6

Varicella also affects the trunk and extremities, but a key clinical finding is crops of characteristic lesions, including papules, vesicles, pustules, and crusted lesions in different stages that manifest simultaneously.6

Insect bites usually appear as urticarial papules and plaques associated with outdoor exposure. The lesions are distributed where insects are likely to bite.6

Treat the infection, control the psoriasis

The first-line treatment for streptococcal infection is amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d [maximum: 1000 mg/d] orally for 10 d) or penicillin G benzathine (for children < 60 lb, 6 × 105 units intramuscularly; children ≥ 60 lb, 1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly).7 For the psoriasis lesions, treatment options include topical glucocorticosteroids, vitamin D derivatives, or combinations of both.5 In most cases, guttate psoriasis completely resolves. However, one-third of children with guttate psoriasis go on to develop plaque psoriasis later in life.8

Our patient was treated with penicillin G benzathine (1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly) and a calcipotriol/betamethasone combination gel. The streptococcal infection and skin lesions completely resolved. No adverse events were reported, and no relapse was observed after 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rita Matos, MD, Rua Actor Mário Viegas SN Rio Tinto, Portugal; [email protected]

1. Maciejewska-Radomska A, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Rebała K, et al. Frequency of streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections and HLA-Cw*06 allele in 70 patients with guttate psoriasis from northern Poland. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:455-458.

2. Garritsen FM, Kraag DE, de Graaf M. Guttate psoriasis triggered by perianal streptococcal infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:536-538.

3. Pfingstler LF, Maroon M, Mowad C. Guttate psoriasis outcomes. Cutis. 2016;97:140-144.

4. Ruiz-Romeu E, Ferran M, Sagristà M, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-induced cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-positive T cell-dependent epidermal cell activation triggers TH17 responses in patients with guttate psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:491-499.

5. Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

6. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. Differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

7. Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Perez ED. Common questions about streptococcal pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:24-31.

8. Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132: 717-718.

A 7-year-old boy was brought to his family physician for evaluation of a mildly pruritic spreading rash. Ten days earlier, the skin eruption had appeared, and he was given a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis, which was confirmed by a throat swab and a positive antistreptolysin O titer. The child had no personal or family history of skin disorders, including eczema or psoriasis. He hadn’t used any topical agents or new medications recently, nor had he been exposed to triggering plants, animals, or chemicals. There was no history of trauma, friction, or rubbing in the area.

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, scaly papules and plaques of varying size on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE). His palms and soles were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Guttate psoriasis

A diagnosis of guttate psoriasis was made based on the physical exam findings and the preceding group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection.

This condition affects approximately 2% of all patients with psoriasis; it is characterized by the acute onset of multiple erythematosquamous papules and small plaques that look like droplets (“gutta”).1 It tends to affect children and young adults and typically occurs following an acute infection (eg, streptococcal pharyngitis).2,3 In this case, a rapid strep test and throat culture positive for group A Streptococcus supported the diagnosis.

Although this particular phenotype of psoriasis is usually associated with streptococcal infection and mainly occurs in patients with the HLA-Cw6+ allele, the specific immunologic response that causes these skin lesions is poorly understood.4 Antigenic similarities between streptococcal proteins and keratinocyte antigens might explain why the condition is triggered by streptococcal infections.5

Pityriasis rosea and tinea corporis are part of the differential

The differential includes skin conditions such as pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis, varicella, and insect bites.

Pityriasis rosea can manifest as a papulosquamous eruption, but it has an inward-facing scale, called a collarette. The “Christmas tree” pattern on the back that is preceded by a solitary 2- to 10-cm oval, pink, scaly herald patch (in 17%-50% of cases) is key to the diagnosis.6 (For more information, see “Rash on trunk and upper arms.”)

Continue to: Tinea corporis...

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection that causes flat, red, scaly lesions that progress into annular lesions with central clearing or brown discoloration. The plaques can range from a few centimeters to several inches in size, but are always characterized by the slowly advancing border.6

Varicella also affects the trunk and extremities, but a key clinical finding is crops of characteristic lesions, including papules, vesicles, pustules, and crusted lesions in different stages that manifest simultaneously.6

Insect bites usually appear as urticarial papules and plaques associated with outdoor exposure. The lesions are distributed where insects are likely to bite.6

Treat the infection, control the psoriasis

The first-line treatment for streptococcal infection is amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d [maximum: 1000 mg/d] orally for 10 d) or penicillin G benzathine (for children < 60 lb, 6 × 105 units intramuscularly; children ≥ 60 lb, 1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly).7 For the psoriasis lesions, treatment options include topical glucocorticosteroids, vitamin D derivatives, or combinations of both.5 In most cases, guttate psoriasis completely resolves. However, one-third of children with guttate psoriasis go on to develop plaque psoriasis later in life.8

Our patient was treated with penicillin G benzathine (1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly) and a calcipotriol/betamethasone combination gel. The streptococcal infection and skin lesions completely resolved. No adverse events were reported, and no relapse was observed after 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rita Matos, MD, Rua Actor Mário Viegas SN Rio Tinto, Portugal; [email protected]

A 7-year-old boy was brought to his family physician for evaluation of a mildly pruritic spreading rash. Ten days earlier, the skin eruption had appeared, and he was given a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis, which was confirmed by a throat swab and a positive antistreptolysin O titer. The child had no personal or family history of skin disorders, including eczema or psoriasis. He hadn’t used any topical agents or new medications recently, nor had he been exposed to triggering plants, animals, or chemicals. There was no history of trauma, friction, or rubbing in the area.

Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, scaly papules and plaques of varying size on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE). His palms and soles were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Guttate psoriasis

A diagnosis of guttate psoriasis was made based on the physical exam findings and the preceding group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection.

This condition affects approximately 2% of all patients with psoriasis; it is characterized by the acute onset of multiple erythematosquamous papules and small plaques that look like droplets (“gutta”).1 It tends to affect children and young adults and typically occurs following an acute infection (eg, streptococcal pharyngitis).2,3 In this case, a rapid strep test and throat culture positive for group A Streptococcus supported the diagnosis.

Although this particular phenotype of psoriasis is usually associated with streptococcal infection and mainly occurs in patients with the HLA-Cw6+ allele, the specific immunologic response that causes these skin lesions is poorly understood.4 Antigenic similarities between streptococcal proteins and keratinocyte antigens might explain why the condition is triggered by streptococcal infections.5

Pityriasis rosea and tinea corporis are part of the differential

The differential includes skin conditions such as pityriasis rosea, tinea corporis, varicella, and insect bites.

Pityriasis rosea can manifest as a papulosquamous eruption, but it has an inward-facing scale, called a collarette. The “Christmas tree” pattern on the back that is preceded by a solitary 2- to 10-cm oval, pink, scaly herald patch (in 17%-50% of cases) is key to the diagnosis.6 (For more information, see “Rash on trunk and upper arms.”)

Continue to: Tinea corporis...

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection that causes flat, red, scaly lesions that progress into annular lesions with central clearing or brown discoloration. The plaques can range from a few centimeters to several inches in size, but are always characterized by the slowly advancing border.6

Varicella also affects the trunk and extremities, but a key clinical finding is crops of characteristic lesions, including papules, vesicles, pustules, and crusted lesions in different stages that manifest simultaneously.6

Insect bites usually appear as urticarial papules and plaques associated with outdoor exposure. The lesions are distributed where insects are likely to bite.6

Treat the infection, control the psoriasis

The first-line treatment for streptococcal infection is amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/d [maximum: 1000 mg/d] orally for 10 d) or penicillin G benzathine (for children < 60 lb, 6 × 105 units intramuscularly; children ≥ 60 lb, 1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly).7 For the psoriasis lesions, treatment options include topical glucocorticosteroids, vitamin D derivatives, or combinations of both.5 In most cases, guttate psoriasis completely resolves. However, one-third of children with guttate psoriasis go on to develop plaque psoriasis later in life.8

Our patient was treated with penicillin G benzathine (1.2 × 106 units intramuscularly) and a calcipotriol/betamethasone combination gel. The streptococcal infection and skin lesions completely resolved. No adverse events were reported, and no relapse was observed after 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rita Matos, MD, Rua Actor Mário Viegas SN Rio Tinto, Portugal; [email protected]

1. Maciejewska-Radomska A, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Rebała K, et al. Frequency of streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections and HLA-Cw*06 allele in 70 patients with guttate psoriasis from northern Poland. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:455-458.

2. Garritsen FM, Kraag DE, de Graaf M. Guttate psoriasis triggered by perianal streptococcal infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:536-538.

3. Pfingstler LF, Maroon M, Mowad C. Guttate psoriasis outcomes. Cutis. 2016;97:140-144.

4. Ruiz-Romeu E, Ferran M, Sagristà M, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-induced cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-positive T cell-dependent epidermal cell activation triggers TH17 responses in patients with guttate psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:491-499.

5. Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

6. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. Differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

7. Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Perez ED. Common questions about streptococcal pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:24-31.

8. Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132: 717-718.

1. Maciejewska-Radomska A, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Rebała K, et al. Frequency of streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections and HLA-Cw*06 allele in 70 patients with guttate psoriasis from northern Poland. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:455-458.

2. Garritsen FM, Kraag DE, de Graaf M. Guttate psoriasis triggered by perianal streptococcal infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:536-538.

3. Pfingstler LF, Maroon M, Mowad C. Guttate psoriasis outcomes. Cutis. 2016;97:140-144.

4. Ruiz-Romeu E, Ferran M, Sagristà M, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-induced cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-positive T cell-dependent epidermal cell activation triggers TH17 responses in patients with guttate psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:491-499.

5. Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

6. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. Differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

7. Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Perez ED. Common questions about streptococcal pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:24-31.

8. Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132: 717-718.

Growth on ear

The FP suspected skin cancer, but was not sure if it was a basal cell carcinoma or a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

The growth was somewhat pearly with telangiectasias, but there was also a prominent area of keratin on the posterior aspect of the lesion. After injecting local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician performed a shave biopsy on one edge of the tumor. He was careful to avoid cutting the cartilage and decided that the diagnosis would be obtained without trying to remove the whole tumor. The bleeding did not stop with chemical hemostasis alone, so electrosurgery was used. The biopsy result showed an SCC of the keratoacanthoma type.

The patient was referred for Mohs surgery because it was important to get clear margins, while attempting to preserve the ear anatomy. Also, SCC of the ear has a higher risk for metastasis, so a thorough exam of the head and neck for lymphadenopathy was performed. Fortunately, this SCC was well-differentiated and no metastases were clinically detected.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Guzman A, Usatine R. Keratocanthoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:977-980.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected skin cancer, but was not sure if it was a basal cell carcinoma or a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

The growth was somewhat pearly with telangiectasias, but there was also a prominent area of keratin on the posterior aspect of the lesion. After injecting local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician performed a shave biopsy on one edge of the tumor. He was careful to avoid cutting the cartilage and decided that the diagnosis would be obtained without trying to remove the whole tumor. The bleeding did not stop with chemical hemostasis alone, so electrosurgery was used. The biopsy result showed an SCC of the keratoacanthoma type.

The patient was referred for Mohs surgery because it was important to get clear margins, while attempting to preserve the ear anatomy. Also, SCC of the ear has a higher risk for metastasis, so a thorough exam of the head and neck for lymphadenopathy was performed. Fortunately, this SCC was well-differentiated and no metastases were clinically detected.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Guzman A, Usatine R. Keratocanthoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:977-980.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected skin cancer, but was not sure if it was a basal cell carcinoma or a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

The growth was somewhat pearly with telangiectasias, but there was also a prominent area of keratin on the posterior aspect of the lesion. After injecting local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, the physician performed a shave biopsy on one edge of the tumor. He was careful to avoid cutting the cartilage and decided that the diagnosis would be obtained without trying to remove the whole tumor. The bleeding did not stop with chemical hemostasis alone, so electrosurgery was used. The biopsy result showed an SCC of the keratoacanthoma type.

The patient was referred for Mohs surgery because it was important to get clear margins, while attempting to preserve the ear anatomy. Also, SCC of the ear has a higher risk for metastasis, so a thorough exam of the head and neck for lymphadenopathy was performed. Fortunately, this SCC was well-differentiated and no metastases were clinically detected.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Guzman A, Usatine R. Keratocanthoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:977-980.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growth on chest

The FP noted that the lesion had a central keratin core (resembling a volcano) surrounded by a somewhat pearly raised border. He suspected that this was a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the keratoacanthoma type and recommended a biopsy.

A shave biopsy was performed, and the result confirmed the diagnosis of SCC of the keratoacanthoma type. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathologist added that the lesion was well-differentiated (which was to be expected with a keratoacanthoma). While some keratoacanthomas actually resolve spontaneously, the standard of care is to treat them with either excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, or cryotherapy. On the follow-up visit, these options were presented to the patient and he decided to have cryotherapy. He accepted the risk of hypopigmentation in the treated area, but said that he preferred to avoid surgery.

The area was anesthetized with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, and cryotherapy was performed with a 5 mm margin. The area was frozen with liquid nitrogen spray for 30 seconds and allowed to thaw. A second freeze for 30 seconds was then applied. Sun protection and sun avoidance were encouraged. At a 1-year follow-up, there was no recurrence and there was hypopigmentation at the treatment site.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Guzman A, Usatine R. Keratoacanthoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:977-980.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP noted that the lesion had a central keratin core (resembling a volcano) surrounded by a somewhat pearly raised border. He suspected that this was a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the keratoacanthoma type and recommended a biopsy.

A shave biopsy was performed, and the result confirmed the diagnosis of SCC of the keratoacanthoma type. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathologist added that the lesion was well-differentiated (which was to be expected with a keratoacanthoma). While some keratoacanthomas actually resolve spontaneously, the standard of care is to treat them with either excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, or cryotherapy. On the follow-up visit, these options were presented to the patient and he decided to have cryotherapy. He accepted the risk of hypopigmentation in the treated area, but said that he preferred to avoid surgery.

The area was anesthetized with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, and cryotherapy was performed with a 5 mm margin. The area was frozen with liquid nitrogen spray for 30 seconds and allowed to thaw. A second freeze for 30 seconds was then applied. Sun protection and sun avoidance were encouraged. At a 1-year follow-up, there was no recurrence and there was hypopigmentation at the treatment site.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Guzman A, Usatine R. Keratoacanthoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:977-980.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP noted that the lesion had a central keratin core (resembling a volcano) surrounded by a somewhat pearly raised border. He suspected that this was a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the keratoacanthoma type and recommended a biopsy.

A shave biopsy was performed, and the result confirmed the diagnosis of SCC of the keratoacanthoma type. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The pathologist added that the lesion was well-differentiated (which was to be expected with a keratoacanthoma). While some keratoacanthomas actually resolve spontaneously, the standard of care is to treat them with either excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, or cryotherapy. On the follow-up visit, these options were presented to the patient and he decided to have cryotherapy. He accepted the risk of hypopigmentation in the treated area, but said that he preferred to avoid surgery.

The area was anesthetized with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, and cryotherapy was performed with a 5 mm margin. The area was frozen with liquid nitrogen spray for 30 seconds and allowed to thaw. A second freeze for 30 seconds was then applied. Sun protection and sun avoidance were encouraged. At a 1-year follow-up, there was no recurrence and there was hypopigmentation at the treatment site.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Guzman A, Usatine R. Keratoacanthoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:977-980.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Scaling lesions on arm

The FP also was concerned about a possible skin cancer, especially for the larger of the 2 lesions. The FP recommended 2 shave biopsies, which the patient agreed to. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The patient was directed to apply petrolatum once or twice daily to the biopsy sites and to cover them with dressings for the next 1 to 2 weeks. On the 2-week follow-up, the physician diagnosed the larger lesion as squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen disease) and the top lesion as actinic keratosis.

The physician explained that the actinic keratosis did not need further treatment; however, the options for treating Bowen disease included cryosurgery, electrodesiccation and curettage, or elliptical excision. The patient chose an elliptical excision, which was performed without complications at the following visit.

The margins were clear and the surgery site healed without any problems. The patient said that he planned to wear long sleeves more often and use sunscreen when his arms were exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Wah Y. Actinic keratosis and Bowen disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:969-976.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP also was concerned about a possible skin cancer, especially for the larger of the 2 lesions. The FP recommended 2 shave biopsies, which the patient agreed to. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The patient was directed to apply petrolatum once or twice daily to the biopsy sites and to cover them with dressings for the next 1 to 2 weeks. On the 2-week follow-up, the physician diagnosed the larger lesion as squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen disease) and the top lesion as actinic keratosis.

The physician explained that the actinic keratosis did not need further treatment; however, the options for treating Bowen disease included cryosurgery, electrodesiccation and curettage, or elliptical excision. The patient chose an elliptical excision, which was performed without complications at the following visit.

The margins were clear and the surgery site healed without any problems. The patient said that he planned to wear long sleeves more often and use sunscreen when his arms were exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Wah Y. Actinic keratosis and Bowen disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:969-976.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP also was concerned about a possible skin cancer, especially for the larger of the 2 lesions. The FP recommended 2 shave biopsies, which the patient agreed to. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The patient was directed to apply petrolatum once or twice daily to the biopsy sites and to cover them with dressings for the next 1 to 2 weeks. On the 2-week follow-up, the physician diagnosed the larger lesion as squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen disease) and the top lesion as actinic keratosis.

The physician explained that the actinic keratosis did not need further treatment; however, the options for treating Bowen disease included cryosurgery, electrodesiccation and curettage, or elliptical excision. The patient chose an elliptical excision, which was performed without complications at the following visit.

The margins were clear and the surgery site healed without any problems. The patient said that he planned to wear long sleeves more often and use sunscreen when his arms were exposed to the sun.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Wah Y. Actinic keratosis and Bowen disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:969-976.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Rough skin on hands

The FP recognized that the lesions on the back of the hands were due to sun damage and included actinic keratosis. However, he was concerned that some of the thicker lesions could be squamous cell carcinoma or SCC in situ.

He discussed options with the patient, which included biopsy of the thickest lesions, cryotherapy, and/or field treatment with a topical agent. The decision was made to biopsy the 2 thickest and whitest lesions and do cryotherapy on some of the other lesions. Shave biopsies were performed and the patient was encouraged to wear sunscreen and minimize his sun exposure. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) On the follow-up visit 2 weeks later, the FP noted that the biopsies and frozen areas were healing. Both biopsies were hypertrophic actinic keratoses only.

The FP then prescribed 5-fluorouracil to be used for 3 to 4 weeks on the remaining lesions on the backs of his hands and forearms. The patient was directed to treat the right arm first to allow more time for the left hand to heal. He was told to stop the 5-fluorouracil if the area became too painful. The patient was also told to treat his left arm the same way after allowing the right arm to heal. Any areas of skin ulceration could be treated with plain petrolatum, but no topical steroids are needed.

Six months later, the patient’s arms and hands looked much better. The patient required regular follow-up.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Wah Y. Actinic keratosis and Bowen disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:969-976.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that the lesions on the back of the hands were due to sun damage and included actinic keratosis. However, he was concerned that some of the thicker lesions could be squamous cell carcinoma or SCC in situ.

He discussed options with the patient, which included biopsy of the thickest lesions, cryotherapy, and/or field treatment with a topical agent. The decision was made to biopsy the 2 thickest and whitest lesions and do cryotherapy on some of the other lesions. Shave biopsies were performed and the patient was encouraged to wear sunscreen and minimize his sun exposure. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) On the follow-up visit 2 weeks later, the FP noted that the biopsies and frozen areas were healing. Both biopsies were hypertrophic actinic keratoses only.

The FP then prescribed 5-fluorouracil to be used for 3 to 4 weeks on the remaining lesions on the backs of his hands and forearms. The patient was directed to treat the right arm first to allow more time for the left hand to heal. He was told to stop the 5-fluorouracil if the area became too painful. The patient was also told to treat his left arm the same way after allowing the right arm to heal. Any areas of skin ulceration could be treated with plain petrolatum, but no topical steroids are needed.

Six months later, the patient’s arms and hands looked much better. The patient required regular follow-up.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Wah Y. Actinic keratosis and Bowen disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:969-976.