User login

Painful blisters on fingertips and toes

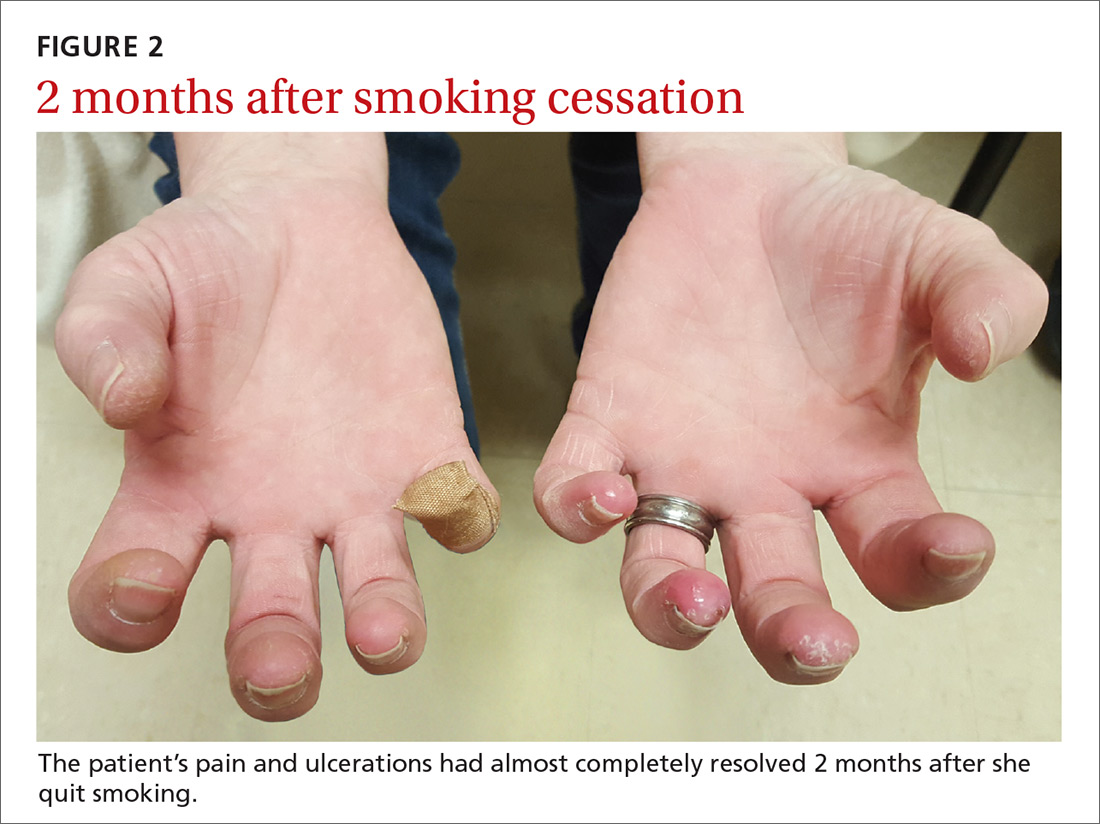

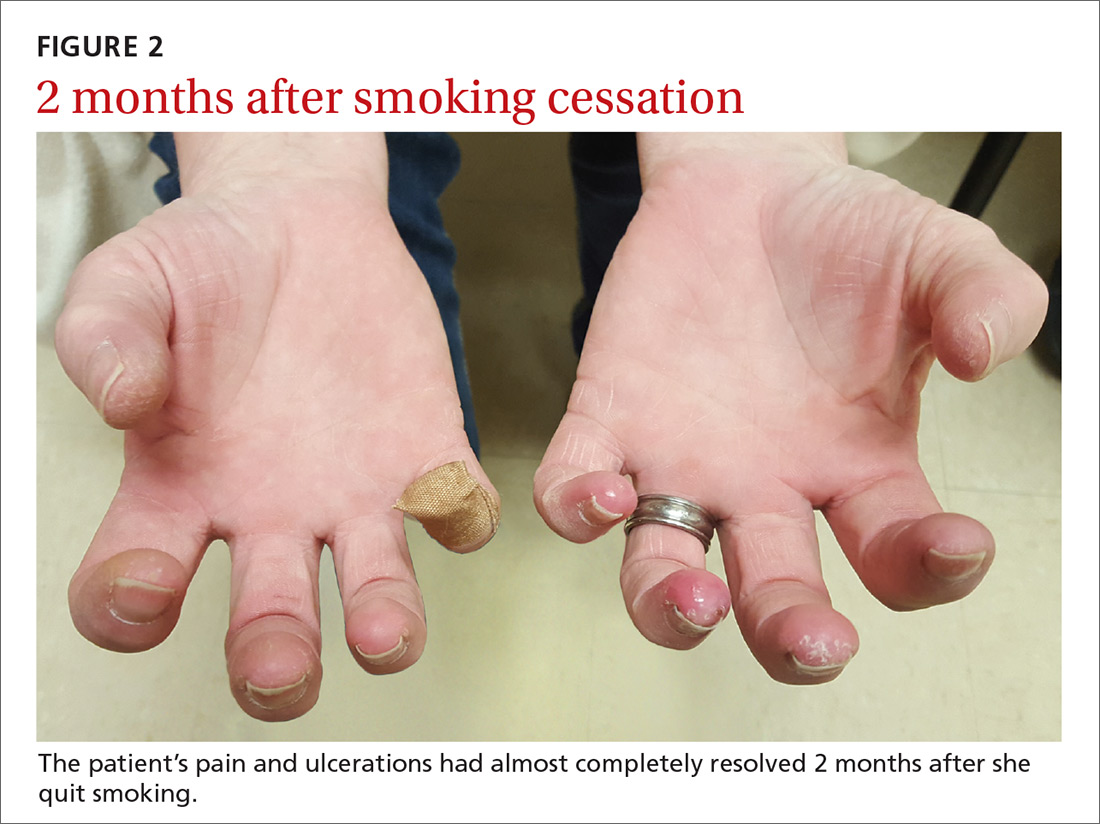

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 4-month history of recurrent painful blisters on her fingertips and the tips of her toes (FIGURE 1), arthralgias, painful discoloration of her distal toes and fingers when exposed to cold, and painful nodules on her forearms. She was started on prednisone and was sent to our clinic for follow-up.

At her initial visit to our office, she was continued on prednisone and referred to Rheumatology and Interventional Cardiology, where a work-up for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other vasculitides was negative. The patient had normal arterial pressures and a normal echocardiogram. An angiogram revealed segmental occlusions of the distal vessels in her arms and legs. The patient denied chest pain, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, or fever. She reported a >30 pack-year history of cigarette smoking.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Thromboangiitis obliterans

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), or Buerger’s disease, is a rare nonatherosclerotic disease that affects the medium and small arteries. The disease has a male predominance, primarily occurs in those younger than 45 years of age, and is most common in people from the Middle and Far East.1 Its distinctive features include ulcerations of the distal extremities and symptoms of claudication and pain at rest. More than 40% of affected patients develop Raynaud’s phenomenon.1 Superficial thrombophlebitis in the form of painful nodules has also been described.2

The etiology of TAO is likely due to disordered inflammation of endothelial cells, which has a strong association with smoking.3 The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but genetics and autoimmunity are suspected contributing factors.

The diagnosis is based on exclusion of other causes

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic angiopathy, embolic disease, atherosclerosis, hypercoagulability/thrombophilia, vasculitis or connective tissue diseases, and drug-associated (eg, cocaine) vasculitis.4

The diagnosis of TAO is based on the exclusion of other causes, although several diagnostic criteria have been proposed, including:

- age <45 years

- current or recent history of tobacco use

- distal extremity involvement (ulcers, claudication, or pain at rest)

- exclusion of diabetes, peripheral artery disease, thrombophilia, or embolic disease

- typical arteriographic findings on imaging, including distal small to medium vessel involvement, segmental occlusions, and “corkscrew-shaped” collaterals.1,2,5,6

Continue to: Lab tests

Lab tests. There are no specific laboratory markers for TAO. The initial evaluation should include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complete metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA). Tests to exclude other autoimmune diseases include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticentromere antibody and Scl-70 to exclude CREST syndrome and scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibodies to exclude disorders of hypercoagulability, and drug testing and history-taking to evaluate for drug-related (eg, cocaine) etiologies. Further studies should be performed based on clinical suspicion.

Imaging. Patients with suspected TAO should undergo an arteriogram of the affected extremities and large arteries. Other imaging modalities include computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography. Biopsy is rarely indicated, unless there are atypical findings, such as large artery involvement or arterial nodules. Interestingly, a positive Allen test in a young smoker can be highly suggestive of TAO.1 (For a demonstration of the Allen test, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tJO0RW9UM.)

Our patient tested negative for rheumatoid arthritis, CREST, and scleroderma and had a normal UA and CMP. She did have a slightly elevated anticardiolipin antibody test, but a negative lupus anticoagulant test, the significance of which is uncertain. Her CRP and ESR were elevated.

Complete smoking cessation is essential for treatment

Several treatments have been proposed, including prostanoids and surgery (surgical revascularization or endovascular therapy).1,4 In severe cases, amputation may be required to remove the affected extremity. However, the most important and most effective treatment for TAO is smoking cessation.1 Of note, several case reports have found that replacing smoking with other nicotine-containing products (eg, chewing tobacco) may not prevent limb loss.7-9

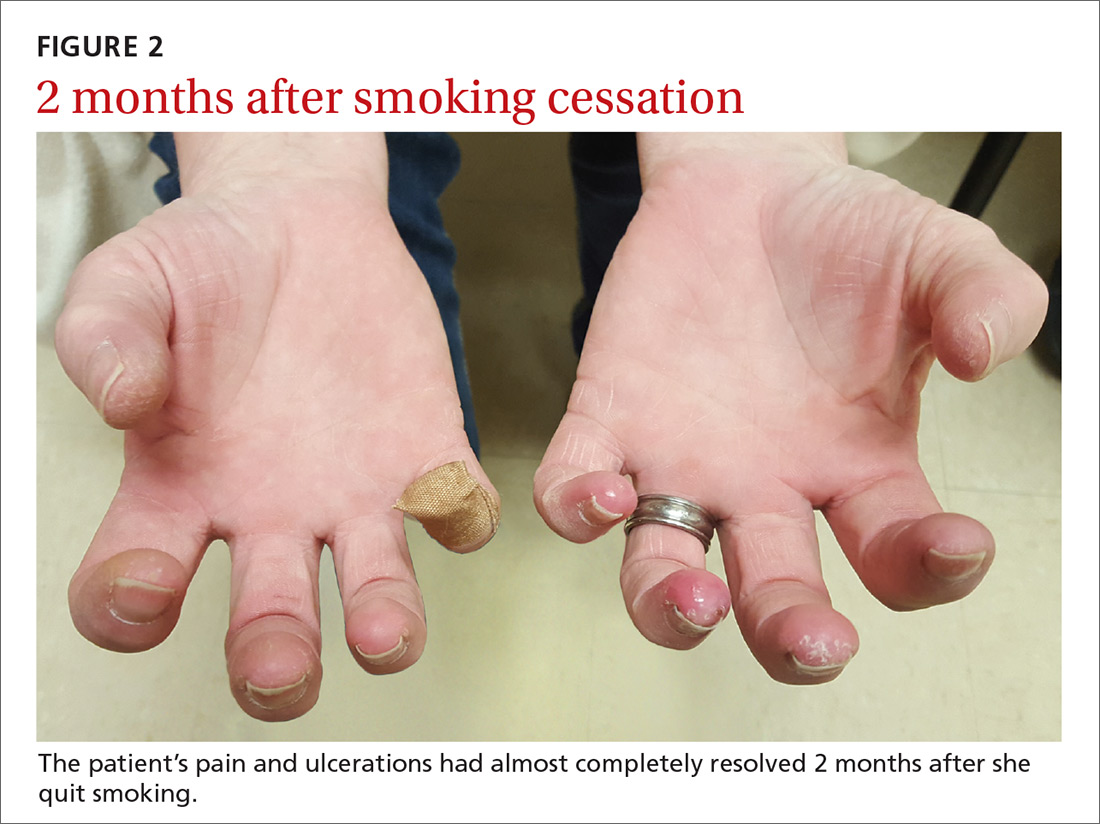

Our patient was tapered off prednisone and was continued on amlodipine 5 mg/d for vasospasm. She was started on varenicline 0.5 mg/d, which was increased to twice daily by Day 4 to aid with smoking cessation. Two months later, the patient’s pain and ulcerations had almost completely resolved (FIGURE 2). She experienced occasional relapses with smoking, during which her ulcerations and Raynaud’s would return. This case reinforces the age-old aphorism of “no tobacco, no Buerger’s disease.”4

CORRESPONDENCE

Seth Mathern, MD, 14300 Orchard Parkway, Westminster, CO 80023; [email protected].

1. Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med. 2000;343:864-869.

2. Piazza G, Creager MA. Thromboangiitis obliterans. Circulation. 2010;121:1858-1861.

3. Azizi M, Boutouyrie P, Bura-Rivière A, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans and endothelial function. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:518-526.

4. Klein-Weigel PF, Richter JG. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Vasa. 2014;43:337-346.

5. Papa MZ, Rabi I, Adar R. A point scoring system for the clinical diagnosis of Buerger’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:335-339.

6. Mills JL, Porter JM. Buerger’s disease: a review and update. Semin Vasc Surg. 1993;6:14-23.

7. Lie JT. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:812-813.

8. O’Dell JR, Linder J, Markin RS, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1054-1056.

9. Lawrence PF, Lund OI, Jimenez JC, et al. Substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes in Buerger’s disease does not prevent limb loss. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:210-212.

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 4-month history of recurrent painful blisters on her fingertips and the tips of her toes (FIGURE 1), arthralgias, painful discoloration of her distal toes and fingers when exposed to cold, and painful nodules on her forearms. She was started on prednisone and was sent to our clinic for follow-up.

At her initial visit to our office, she was continued on prednisone and referred to Rheumatology and Interventional Cardiology, where a work-up for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other vasculitides was negative. The patient had normal arterial pressures and a normal echocardiogram. An angiogram revealed segmental occlusions of the distal vessels in her arms and legs. The patient denied chest pain, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, or fever. She reported a >30 pack-year history of cigarette smoking.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Thromboangiitis obliterans

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), or Buerger’s disease, is a rare nonatherosclerotic disease that affects the medium and small arteries. The disease has a male predominance, primarily occurs in those younger than 45 years of age, and is most common in people from the Middle and Far East.1 Its distinctive features include ulcerations of the distal extremities and symptoms of claudication and pain at rest. More than 40% of affected patients develop Raynaud’s phenomenon.1 Superficial thrombophlebitis in the form of painful nodules has also been described.2

The etiology of TAO is likely due to disordered inflammation of endothelial cells, which has a strong association with smoking.3 The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but genetics and autoimmunity are suspected contributing factors.

The diagnosis is based on exclusion of other causes

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic angiopathy, embolic disease, atherosclerosis, hypercoagulability/thrombophilia, vasculitis or connective tissue diseases, and drug-associated (eg, cocaine) vasculitis.4

The diagnosis of TAO is based on the exclusion of other causes, although several diagnostic criteria have been proposed, including:

- age <45 years

- current or recent history of tobacco use

- distal extremity involvement (ulcers, claudication, or pain at rest)

- exclusion of diabetes, peripheral artery disease, thrombophilia, or embolic disease

- typical arteriographic findings on imaging, including distal small to medium vessel involvement, segmental occlusions, and “corkscrew-shaped” collaterals.1,2,5,6

Continue to: Lab tests

Lab tests. There are no specific laboratory markers for TAO. The initial evaluation should include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complete metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA). Tests to exclude other autoimmune diseases include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticentromere antibody and Scl-70 to exclude CREST syndrome and scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibodies to exclude disorders of hypercoagulability, and drug testing and history-taking to evaluate for drug-related (eg, cocaine) etiologies. Further studies should be performed based on clinical suspicion.

Imaging. Patients with suspected TAO should undergo an arteriogram of the affected extremities and large arteries. Other imaging modalities include computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography. Biopsy is rarely indicated, unless there are atypical findings, such as large artery involvement or arterial nodules. Interestingly, a positive Allen test in a young smoker can be highly suggestive of TAO.1 (For a demonstration of the Allen test, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tJO0RW9UM.)

Our patient tested negative for rheumatoid arthritis, CREST, and scleroderma and had a normal UA and CMP. She did have a slightly elevated anticardiolipin antibody test, but a negative lupus anticoagulant test, the significance of which is uncertain. Her CRP and ESR were elevated.

Complete smoking cessation is essential for treatment

Several treatments have been proposed, including prostanoids and surgery (surgical revascularization or endovascular therapy).1,4 In severe cases, amputation may be required to remove the affected extremity. However, the most important and most effective treatment for TAO is smoking cessation.1 Of note, several case reports have found that replacing smoking with other nicotine-containing products (eg, chewing tobacco) may not prevent limb loss.7-9

Our patient was tapered off prednisone and was continued on amlodipine 5 mg/d for vasospasm. She was started on varenicline 0.5 mg/d, which was increased to twice daily by Day 4 to aid with smoking cessation. Two months later, the patient’s pain and ulcerations had almost completely resolved (FIGURE 2). She experienced occasional relapses with smoking, during which her ulcerations and Raynaud’s would return. This case reinforces the age-old aphorism of “no tobacco, no Buerger’s disease.”4

CORRESPONDENCE

Seth Mathern, MD, 14300 Orchard Parkway, Westminster, CO 80023; [email protected].

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 4-month history of recurrent painful blisters on her fingertips and the tips of her toes (FIGURE 1), arthralgias, painful discoloration of her distal toes and fingers when exposed to cold, and painful nodules on her forearms. She was started on prednisone and was sent to our clinic for follow-up.

At her initial visit to our office, she was continued on prednisone and referred to Rheumatology and Interventional Cardiology, where a work-up for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other vasculitides was negative. The patient had normal arterial pressures and a normal echocardiogram. An angiogram revealed segmental occlusions of the distal vessels in her arms and legs. The patient denied chest pain, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, or fever. She reported a >30 pack-year history of cigarette smoking.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Thromboangiitis obliterans

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), or Buerger’s disease, is a rare nonatherosclerotic disease that affects the medium and small arteries. The disease has a male predominance, primarily occurs in those younger than 45 years of age, and is most common in people from the Middle and Far East.1 Its distinctive features include ulcerations of the distal extremities and symptoms of claudication and pain at rest. More than 40% of affected patients develop Raynaud’s phenomenon.1 Superficial thrombophlebitis in the form of painful nodules has also been described.2

The etiology of TAO is likely due to disordered inflammation of endothelial cells, which has a strong association with smoking.3 The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but genetics and autoimmunity are suspected contributing factors.

The diagnosis is based on exclusion of other causes

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic angiopathy, embolic disease, atherosclerosis, hypercoagulability/thrombophilia, vasculitis or connective tissue diseases, and drug-associated (eg, cocaine) vasculitis.4

The diagnosis of TAO is based on the exclusion of other causes, although several diagnostic criteria have been proposed, including:

- age <45 years

- current or recent history of tobacco use

- distal extremity involvement (ulcers, claudication, or pain at rest)

- exclusion of diabetes, peripheral artery disease, thrombophilia, or embolic disease

- typical arteriographic findings on imaging, including distal small to medium vessel involvement, segmental occlusions, and “corkscrew-shaped” collaterals.1,2,5,6

Continue to: Lab tests

Lab tests. There are no specific laboratory markers for TAO. The initial evaluation should include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complete metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA). Tests to exclude other autoimmune diseases include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticentromere antibody and Scl-70 to exclude CREST syndrome and scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibodies to exclude disorders of hypercoagulability, and drug testing and history-taking to evaluate for drug-related (eg, cocaine) etiologies. Further studies should be performed based on clinical suspicion.

Imaging. Patients with suspected TAO should undergo an arteriogram of the affected extremities and large arteries. Other imaging modalities include computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography. Biopsy is rarely indicated, unless there are atypical findings, such as large artery involvement or arterial nodules. Interestingly, a positive Allen test in a young smoker can be highly suggestive of TAO.1 (For a demonstration of the Allen test, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tJO0RW9UM.)

Our patient tested negative for rheumatoid arthritis, CREST, and scleroderma and had a normal UA and CMP. She did have a slightly elevated anticardiolipin antibody test, but a negative lupus anticoagulant test, the significance of which is uncertain. Her CRP and ESR were elevated.

Complete smoking cessation is essential for treatment

Several treatments have been proposed, including prostanoids and surgery (surgical revascularization or endovascular therapy).1,4 In severe cases, amputation may be required to remove the affected extremity. However, the most important and most effective treatment for TAO is smoking cessation.1 Of note, several case reports have found that replacing smoking with other nicotine-containing products (eg, chewing tobacco) may not prevent limb loss.7-9

Our patient was tapered off prednisone and was continued on amlodipine 5 mg/d for vasospasm. She was started on varenicline 0.5 mg/d, which was increased to twice daily by Day 4 to aid with smoking cessation. Two months later, the patient’s pain and ulcerations had almost completely resolved (FIGURE 2). She experienced occasional relapses with smoking, during which her ulcerations and Raynaud’s would return. This case reinforces the age-old aphorism of “no tobacco, no Buerger’s disease.”4

CORRESPONDENCE

Seth Mathern, MD, 14300 Orchard Parkway, Westminster, CO 80023; [email protected].

1. Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med. 2000;343:864-869.

2. Piazza G, Creager MA. Thromboangiitis obliterans. Circulation. 2010;121:1858-1861.

3. Azizi M, Boutouyrie P, Bura-Rivière A, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans and endothelial function. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:518-526.

4. Klein-Weigel PF, Richter JG. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Vasa. 2014;43:337-346.

5. Papa MZ, Rabi I, Adar R. A point scoring system for the clinical diagnosis of Buerger’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:335-339.

6. Mills JL, Porter JM. Buerger’s disease: a review and update. Semin Vasc Surg. 1993;6:14-23.

7. Lie JT. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:812-813.

8. O’Dell JR, Linder J, Markin RS, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1054-1056.

9. Lawrence PF, Lund OI, Jimenez JC, et al. Substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes in Buerger’s disease does not prevent limb loss. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:210-212.

1. Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med. 2000;343:864-869.

2. Piazza G, Creager MA. Thromboangiitis obliterans. Circulation. 2010;121:1858-1861.

3. Azizi M, Boutouyrie P, Bura-Rivière A, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans and endothelial function. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:518-526.

4. Klein-Weigel PF, Richter JG. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Vasa. 2014;43:337-346.

5. Papa MZ, Rabi I, Adar R. A point scoring system for the clinical diagnosis of Buerger’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:335-339.

6. Mills JL, Porter JM. Buerger’s disease: a review and update. Semin Vasc Surg. 1993;6:14-23.

7. Lie JT. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:812-813.

8. O’Dell JR, Linder J, Markin RS, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1054-1056.

9. Lawrence PF, Lund OI, Jimenez JC, et al. Substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes in Buerger’s disease does not prevent limb loss. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:210-212.

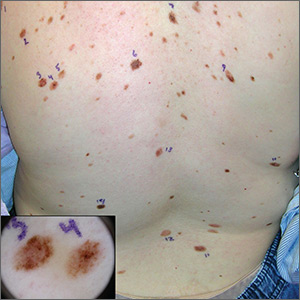

Atypical pigmented lesions on back

The FP recognized that this patient had multiple dysplastic nevi (DN) and was concerned about a possible melanoma.

Although this patient did not have the familial atypical mole and melanoma (FAMM) syndrome, she was at higher risk of developing a melanoma based on the numerous DN that were so visibly apparent on her trunk. (A diagnosis of FAMM requires the occurrence of melanoma in one or more first- or second-degree relatives.)

Total body photography is the current state-of-the-art technology for monitoring patients with multiple atypical moles at higher risk for skin cancer. Small changes in DN and new nevi can be seen best with this technology. Individual flat lesions also can be monitored with dermoscopy over 3 to 4 months.

It is not recommended, however, to follow a suspicious raised lesion over time with dermoscopy and/or photography because a raised lesion might be a nodular melanoma and a delay of diagnosis of over 3 months may worsen the prognosis.

In this case, the patient was happy to be referred to a dermatologist with total body photography. Fortunately, the patient reported back to her FP that the dermatologist did not detect any melanomas, and 2 biopsies that were performed came back as DN only.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that this patient had multiple dysplastic nevi (DN) and was concerned about a possible melanoma.

Although this patient did not have the familial atypical mole and melanoma (FAMM) syndrome, she was at higher risk of developing a melanoma based on the numerous DN that were so visibly apparent on her trunk. (A diagnosis of FAMM requires the occurrence of melanoma in one or more first- or second-degree relatives.)

Total body photography is the current state-of-the-art technology for monitoring patients with multiple atypical moles at higher risk for skin cancer. Small changes in DN and new nevi can be seen best with this technology. Individual flat lesions also can be monitored with dermoscopy over 3 to 4 months.

It is not recommended, however, to follow a suspicious raised lesion over time with dermoscopy and/or photography because a raised lesion might be a nodular melanoma and a delay of diagnosis of over 3 months may worsen the prognosis.

In this case, the patient was happy to be referred to a dermatologist with total body photography. Fortunately, the patient reported back to her FP that the dermatologist did not detect any melanomas, and 2 biopsies that were performed came back as DN only.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that this patient had multiple dysplastic nevi (DN) and was concerned about a possible melanoma.

Although this patient did not have the familial atypical mole and melanoma (FAMM) syndrome, she was at higher risk of developing a melanoma based on the numerous DN that were so visibly apparent on her trunk. (A diagnosis of FAMM requires the occurrence of melanoma in one or more first- or second-degree relatives.)

Total body photography is the current state-of-the-art technology for monitoring patients with multiple atypical moles at higher risk for skin cancer. Small changes in DN and new nevi can be seen best with this technology. Individual flat lesions also can be monitored with dermoscopy over 3 to 4 months.

It is not recommended, however, to follow a suspicious raised lesion over time with dermoscopy and/or photography because a raised lesion might be a nodular melanoma and a delay of diagnosis of over 3 months may worsen the prognosis.

In this case, the patient was happy to be referred to a dermatologist with total body photography. Fortunately, the patient reported back to her FP that the dermatologist did not detect any melanomas, and 2 biopsies that were performed came back as DN only.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Dark spot on back

A biopsy revealed a compound dysplastic nevus (DN) with no signs of malignancy. There was only mild atypia (if severe atypia is reported, then the lesion often is treated as a melanoma in-situ).

The FP was initially concerned about melanoma, given the size, growth, and other characteristics of the lesion. He performed dermoscopy and noted an irregular network with multiple asymmetrically placed dots off the network. His differential diagnosis included melanoma, melanoma in-situ, and dysplastic nevus. After informed consent, he performed a saucerization (deep shave) with a DermaBlade, taking 2-mm margins of clinically normal skin, which revealed the DN. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

Dysplastic nevi (with mild to moderate atypia) are benign acquired melanocytic lesions of the skin. Most are compound nevi possessing a junctional and intradermal component. While dysplastic nevi are not premalignant lesions, they do have some (small) potential for malignant transformation and patients with multiple DN have an increased risk for melanoma. Cutting out all the DN does not change that risk of melanoma.

The FP explained that no further treatment was needed and offered yearly skin exams to monitor for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

A biopsy revealed a compound dysplastic nevus (DN) with no signs of malignancy. There was only mild atypia (if severe atypia is reported, then the lesion often is treated as a melanoma in-situ).

The FP was initially concerned about melanoma, given the size, growth, and other characteristics of the lesion. He performed dermoscopy and noted an irregular network with multiple asymmetrically placed dots off the network. His differential diagnosis included melanoma, melanoma in-situ, and dysplastic nevus. After informed consent, he performed a saucerization (deep shave) with a DermaBlade, taking 2-mm margins of clinically normal skin, which revealed the DN. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

Dysplastic nevi (with mild to moderate atypia) are benign acquired melanocytic lesions of the skin. Most are compound nevi possessing a junctional and intradermal component. While dysplastic nevi are not premalignant lesions, they do have some (small) potential for malignant transformation and patients with multiple DN have an increased risk for melanoma. Cutting out all the DN does not change that risk of melanoma.

The FP explained that no further treatment was needed and offered yearly skin exams to monitor for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

A biopsy revealed a compound dysplastic nevus (DN) with no signs of malignancy. There was only mild atypia (if severe atypia is reported, then the lesion often is treated as a melanoma in-situ).

The FP was initially concerned about melanoma, given the size, growth, and other characteristics of the lesion. He performed dermoscopy and noted an irregular network with multiple asymmetrically placed dots off the network. His differential diagnosis included melanoma, melanoma in-situ, and dysplastic nevus. After informed consent, he performed a saucerization (deep shave) with a DermaBlade, taking 2-mm margins of clinically normal skin, which revealed the DN. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

Dysplastic nevi (with mild to moderate atypia) are benign acquired melanocytic lesions of the skin. Most are compound nevi possessing a junctional and intradermal component. While dysplastic nevi are not premalignant lesions, they do have some (small) potential for malignant transformation and patients with multiple DN have an increased risk for melanoma. Cutting out all the DN does not change that risk of melanoma.

The FP explained that no further treatment was needed and offered yearly skin exams to monitor for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Rash on forearm

The FP did not recognize the rash, so she decided to do a Google search. She typed the following terms into the search box: linear hypopigmented papules on the arm of a child. Almost every result described lichen striatus.

The photographs were very similar, and the description was a great fit for the patient’s condition. Clearly, this was not poison ivy and was unrelated to the camping trip. The physician learned that lichen striatus is a benign idiopathic condition that often affects children on a single extremity. The flat-topped papules tend to run parallel to the long axis of the extremity following Blaschko lines (lines related to embryogenesis). In darker-skinned patients, the papules are often hypopigmented. The papules are usually asymptomatic and resolve on their own, over time.

The mother was reassured and happy to hear that this would go away without any treatment. The physician was delighted to have been able to make a diagnosis by using her ability to describe the rash and the “intelligence” of the search engine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP did not recognize the rash, so she decided to do a Google search. She typed the following terms into the search box: linear hypopigmented papules on the arm of a child. Almost every result described lichen striatus.

The photographs were very similar, and the description was a great fit for the patient’s condition. Clearly, this was not poison ivy and was unrelated to the camping trip. The physician learned that lichen striatus is a benign idiopathic condition that often affects children on a single extremity. The flat-topped papules tend to run parallel to the long axis of the extremity following Blaschko lines (lines related to embryogenesis). In darker-skinned patients, the papules are often hypopigmented. The papules are usually asymptomatic and resolve on their own, over time.

The mother was reassured and happy to hear that this would go away without any treatment. The physician was delighted to have been able to make a diagnosis by using her ability to describe the rash and the “intelligence” of the search engine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP did not recognize the rash, so she decided to do a Google search. She typed the following terms into the search box: linear hypopigmented papules on the arm of a child. Almost every result described lichen striatus.

The photographs were very similar, and the description was a great fit for the patient’s condition. Clearly, this was not poison ivy and was unrelated to the camping trip. The physician learned that lichen striatus is a benign idiopathic condition that often affects children on a single extremity. The flat-topped papules tend to run parallel to the long axis of the extremity following Blaschko lines (lines related to embryogenesis). In darker-skinned patients, the papules are often hypopigmented. The papules are usually asymptomatic and resolve on their own, over time.

The mother was reassured and happy to hear that this would go away without any treatment. The physician was delighted to have been able to make a diagnosis by using her ability to describe the rash and the “intelligence” of the search engine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Bumps under eyes

The FP diagnosed syringomas in this patient.

He explained that the bumps are benign tumors that occur frequently on the lower eyelids and upper cheeks. They are completely unrelated to the birth control pill and can develop in men, and run in families, too. While syringomas appear to occur more often in women than men, there are no known causative agents. These are benign growths of the eccrine sweat glands.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, electrosurgery, or chemical destruction with trichloroacetic acid. All of these approaches need to be performed carefully, as the syringomas are so close to the eye. Also, these treatments are only modestly effective; new syringomas can form. And there are no preventive treatments.

In this case, the patient had light brown skin, so there was a risk of causing permanent hypopigmentation with any of these destructive methods. The patient was reassured about the benign nature of the condition; she decided not to seek therapy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP diagnosed syringomas in this patient.

He explained that the bumps are benign tumors that occur frequently on the lower eyelids and upper cheeks. They are completely unrelated to the birth control pill and can develop in men, and run in families, too. While syringomas appear to occur more often in women than men, there are no known causative agents. These are benign growths of the eccrine sweat glands.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, electrosurgery, or chemical destruction with trichloroacetic acid. All of these approaches need to be performed carefully, as the syringomas are so close to the eye. Also, these treatments are only modestly effective; new syringomas can form. And there are no preventive treatments.

In this case, the patient had light brown skin, so there was a risk of causing permanent hypopigmentation with any of these destructive methods. The patient was reassured about the benign nature of the condition; she decided not to seek therapy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP diagnosed syringomas in this patient.

He explained that the bumps are benign tumors that occur frequently on the lower eyelids and upper cheeks. They are completely unrelated to the birth control pill and can develop in men, and run in families, too. While syringomas appear to occur more often in women than men, there are no known causative agents. These are benign growths of the eccrine sweat glands.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, electrosurgery, or chemical destruction with trichloroacetic acid. All of these approaches need to be performed carefully, as the syringomas are so close to the eye. Also, these treatments are only modestly effective; new syringomas can form. And there are no preventive treatments.

In this case, the patient had light brown skin, so there was a risk of causing permanent hypopigmentation with any of these destructive methods. The patient was reassured about the benign nature of the condition; she decided not to seek therapy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

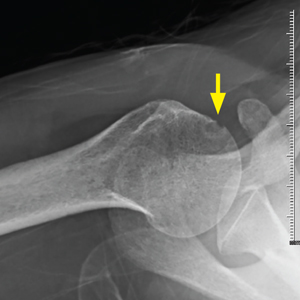

Pain in right shoulder

A 44-year-old African-American woman with sickle cell trait presented to the clinic to establish care. She complained of polyarthralgias that she’d had since adolescence; the pain was worst in her right shoulder. She reported morning stiffness that lasted up to 8 hours, an intermittent facial rash, oral ulcers, joint edema (of which she had pictures on her phone), and photosensitivity. She took ibuprofen and acetaminophen as needed for pain. She once worked as a medical assistant but hadn’t been able to work since 2014 due to pain. She reported having been told as a teenager that she might have juvenile arthritis, but she didn’t recall ever having diagnostic tests performed or receiving treatment other than anti-inflammatories.

A couple of weeks after an initial visit with a rheumatologist, the patient returned to the family medicine clinic. She said she was upset that the specialist had x-rayed her hands, but had not checked her shoulder, which was the primary source of her pain. She also had pain in her hands, hips, feet, and knees.

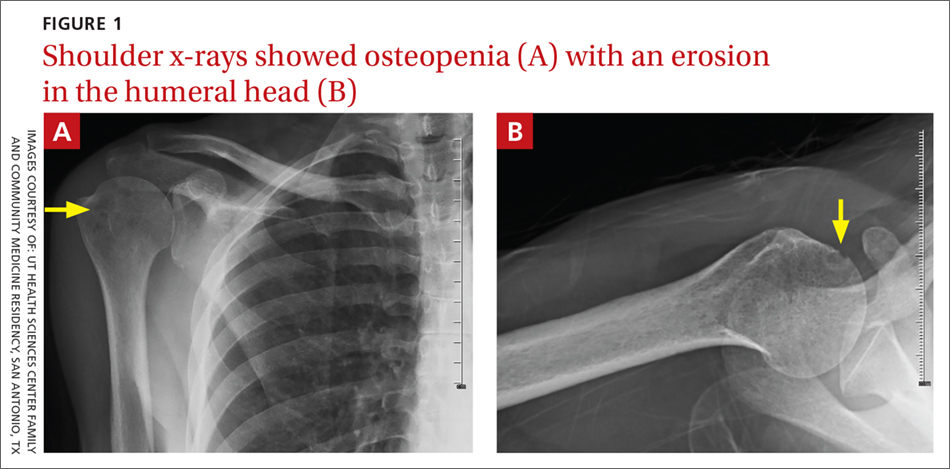

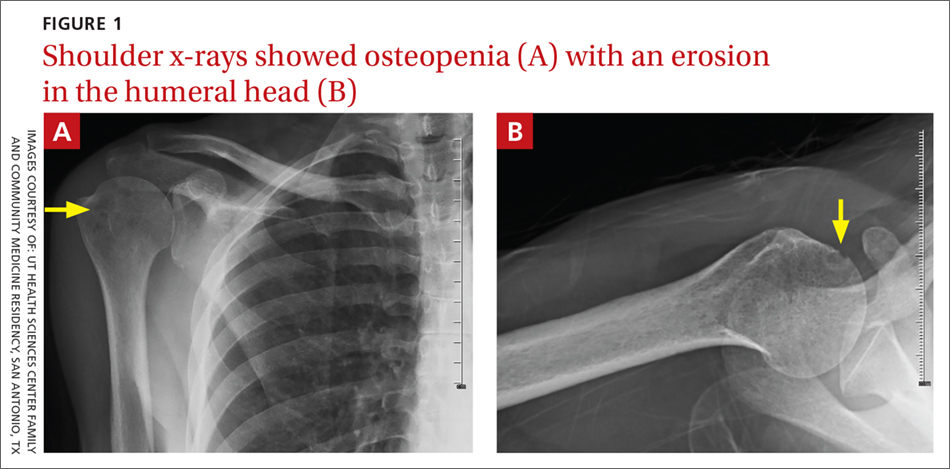

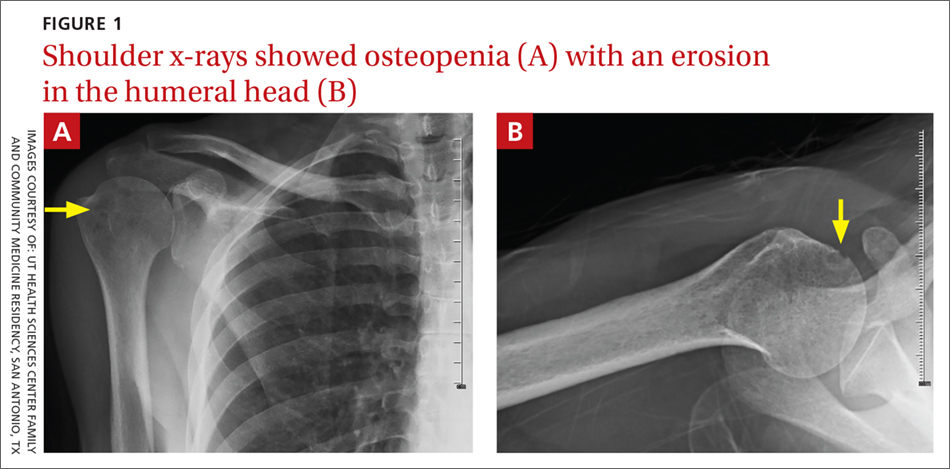

On physical exam, the patient looked fatigued. A musculoskeletal exam revealed no joint effusions or edema, but was significant for right shoulder pain with reduced abduction to 90°. Gross motor strength was 5/5 in all 4 extremities. Laboratory testing revealed an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:160 and was negative for double-stranded DNA. Bilateral hand and foot x-rays showed no joint erosions. An x-ray of the right shoulder was obtained, which showed evidence of osteopenia and an erosion in the humeral head (FIGURES 1A and 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rheumatoid arthritis

The patient’s history of morning stiffness and the joint erosion observed on x-ray were highly suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

RA is a symmetric, inflammatory, peripheral polyarthritis of unknown etiology. It is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis, affecting 1% of the population worldwide.1 It causes cartilage and bone to erode, leading to the deformation and destruction of joints. If RA is left untreated or is unresponsive to therapy, it can eventually lead to loss of physical function.

Making the diagnosis

The distinctive signs of RA are joint erosions and rheumatoid nodules, which are often absent on initial presentation.

Classification criteria. The 2010 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) classification criteria for RA2 are based on the presence of synovitis in at least one joint, the absence of an alternative diagnosis that better explains the synovitis, and a cumulative score of at least 6/10 from the following 4 domains:

- Number and site of involved joints

- 2 to 10 large joints (shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, ankles)=1 point

- 1 to 3 small joints (metacarpophalangeal [MCP] joints, proximal interphalangeal [PIP] joints, 2nd-5th metatarsophalangeal joints, thumb interphalangeal joints, wrists)=2 points

- 4 to 10 small joints=3 points

- More than 10 joints (including at least 1 small joint)=5 points

- Serologic abnormality (rheumatoid factor [RF] and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide)

- Low positive=2 points

- High positive=3 points

- Elevated acute phase response (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] or C-reactive protein [CRP])=1 point

- Symptom duration of at least 6 weeks=1 point.

These criteria are best suited for early disease. For patients with longstanding symptoms, diagnosis is based on an erosive disease with a history of criteria fulfillment, or a currently inactive longstanding disease, with or without treatment, that has previously fulfilled the criteria.3

Continue to: The differential Dx is extensive

The differential Dx is extensive

The differential includes polyarthralgias such as viral polyarthritis, systemic rheumatic diseases, and osteoarthritis.

Viral polyarthritis is caused by rubella, parvovirus B194, alphaviruses, and hepatitis B. Symptoms can last from 3 days to several weeks, but rarely persist beyond 6 weeks; alphaviruses, however, can last 3 to 6 months.5 The common symptom triad includes fever, arthritis, and rash. Chikungunya is an example of an alphavirus that has become a global disease. Alphavirus arthritis can mimic seronegative RA and even satisfy the classification criteria for RA if the initial symptoms of fever and rash and history of travel to endemic regions are not appreciated.5

Systemic rheumatic diseases. Early RA may mimic the arthritis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome, dermatomyositis, or mixed connective tissue disease.6 In contrast to RA, these disorders generally have systemic features, such as rashes, dry mouth and eyes, myositis, or nephritis, and generate autobodies, which are not seen with RA. The CRP is often normal in patients with active SLE, even when the ESR is elevated.

Osteoarthritis (OA) can be confused with RA, particularly when small joints are involved. A thorough history helps elucidate the diagnosis. For example, OA of the fingers affects distal interphalangeal joints and is associated with Heberden’s nodes, while RA more commonly affects MCP and PIP joints. Swelling from OA is typically firm, while swelling due to RA is warm, boggy, and tender. Joint stiffness due to OA is worse with activity and generally lasts only a few minutes, while joint stiffness due to RA is worse at rest and lasts 30 minutes or more. X-rays show joint-space narrowing with OA, but no erosions or cysts. RF may be present at low levels in older patients with OA, while it is usually associated with high levels in patients with seropositive RA.

Continue to: Treat with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Treat with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Immediate treatment of RA with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is important to achieve control of the disease and prevent disability.

Our patient. We ordered a purified protein derivative skin test in preparation for the patient to start therapy with a DMARD. Our patient followed up with Rheumatology and was started on indomethacin, with an initial dose of 25 mg bid. (DMARDs are first-line therapy; indomethacin is a second-line choice. In this case, the patient declined DMARDs after hearing they lowered the body’s ability to fight infection.) An RF level measured 6.74 IU/ml, which is within normal limits. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Barbara Kiersz, DO, 6835 Austin Center Blvd., Austin, TX 78731; [email protected].

1. Rothschild BM, Turner KR, DeLuca MA. Symmetrical erosive peripheral polyarthritis in the Late Archaic Period of Alabama. Science. 1988;241:1498-1501.

2. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1580-1588.

3. Pincus T, Callahan LF. How many types of patients meet classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis? J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1385-1389.

4. Smith CA, Woolf AD, Lenci M. Parvoviruses: infections and arthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1987;13:249-263.

5. Miner JJ, Aw-Yeang HX, Fox JM, et al. Chikungunya viral arthritis in the United States: a mimic of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1214-1220.

6. Cronin ME. Musculoskeletal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1988;14:99-116.

A 44-year-old African-American woman with sickle cell trait presented to the clinic to establish care. She complained of polyarthralgias that she’d had since adolescence; the pain was worst in her right shoulder. She reported morning stiffness that lasted up to 8 hours, an intermittent facial rash, oral ulcers, joint edema (of which she had pictures on her phone), and photosensitivity. She took ibuprofen and acetaminophen as needed for pain. She once worked as a medical assistant but hadn’t been able to work since 2014 due to pain. She reported having been told as a teenager that she might have juvenile arthritis, but she didn’t recall ever having diagnostic tests performed or receiving treatment other than anti-inflammatories.

A couple of weeks after an initial visit with a rheumatologist, the patient returned to the family medicine clinic. She said she was upset that the specialist had x-rayed her hands, but had not checked her shoulder, which was the primary source of her pain. She also had pain in her hands, hips, feet, and knees.

On physical exam, the patient looked fatigued. A musculoskeletal exam revealed no joint effusions or edema, but was significant for right shoulder pain with reduced abduction to 90°. Gross motor strength was 5/5 in all 4 extremities. Laboratory testing revealed an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:160 and was negative for double-stranded DNA. Bilateral hand and foot x-rays showed no joint erosions. An x-ray of the right shoulder was obtained, which showed evidence of osteopenia and an erosion in the humeral head (FIGURES 1A and 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rheumatoid arthritis

The patient’s history of morning stiffness and the joint erosion observed on x-ray were highly suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

RA is a symmetric, inflammatory, peripheral polyarthritis of unknown etiology. It is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis, affecting 1% of the population worldwide.1 It causes cartilage and bone to erode, leading to the deformation and destruction of joints. If RA is left untreated or is unresponsive to therapy, it can eventually lead to loss of physical function.

Making the diagnosis

The distinctive signs of RA are joint erosions and rheumatoid nodules, which are often absent on initial presentation.

Classification criteria. The 2010 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) classification criteria for RA2 are based on the presence of synovitis in at least one joint, the absence of an alternative diagnosis that better explains the synovitis, and a cumulative score of at least 6/10 from the following 4 domains:

- Number and site of involved joints

- 2 to 10 large joints (shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, ankles)=1 point

- 1 to 3 small joints (metacarpophalangeal [MCP] joints, proximal interphalangeal [PIP] joints, 2nd-5th metatarsophalangeal joints, thumb interphalangeal joints, wrists)=2 points

- 4 to 10 small joints=3 points

- More than 10 joints (including at least 1 small joint)=5 points

- Serologic abnormality (rheumatoid factor [RF] and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide)

- Low positive=2 points

- High positive=3 points

- Elevated acute phase response (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] or C-reactive protein [CRP])=1 point

- Symptom duration of at least 6 weeks=1 point.

These criteria are best suited for early disease. For patients with longstanding symptoms, diagnosis is based on an erosive disease with a history of criteria fulfillment, or a currently inactive longstanding disease, with or without treatment, that has previously fulfilled the criteria.3

Continue to: The differential Dx is extensive

The differential Dx is extensive

The differential includes polyarthralgias such as viral polyarthritis, systemic rheumatic diseases, and osteoarthritis.

Viral polyarthritis is caused by rubella, parvovirus B194, alphaviruses, and hepatitis B. Symptoms can last from 3 days to several weeks, but rarely persist beyond 6 weeks; alphaviruses, however, can last 3 to 6 months.5 The common symptom triad includes fever, arthritis, and rash. Chikungunya is an example of an alphavirus that has become a global disease. Alphavirus arthritis can mimic seronegative RA and even satisfy the classification criteria for RA if the initial symptoms of fever and rash and history of travel to endemic regions are not appreciated.5

Systemic rheumatic diseases. Early RA may mimic the arthritis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome, dermatomyositis, or mixed connective tissue disease.6 In contrast to RA, these disorders generally have systemic features, such as rashes, dry mouth and eyes, myositis, or nephritis, and generate autobodies, which are not seen with RA. The CRP is often normal in patients with active SLE, even when the ESR is elevated.

Osteoarthritis (OA) can be confused with RA, particularly when small joints are involved. A thorough history helps elucidate the diagnosis. For example, OA of the fingers affects distal interphalangeal joints and is associated with Heberden’s nodes, while RA more commonly affects MCP and PIP joints. Swelling from OA is typically firm, while swelling due to RA is warm, boggy, and tender. Joint stiffness due to OA is worse with activity and generally lasts only a few minutes, while joint stiffness due to RA is worse at rest and lasts 30 minutes or more. X-rays show joint-space narrowing with OA, but no erosions or cysts. RF may be present at low levels in older patients with OA, while it is usually associated with high levels in patients with seropositive RA.

Continue to: Treat with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Treat with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Immediate treatment of RA with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is important to achieve control of the disease and prevent disability.

Our patient. We ordered a purified protein derivative skin test in preparation for the patient to start therapy with a DMARD. Our patient followed up with Rheumatology and was started on indomethacin, with an initial dose of 25 mg bid. (DMARDs are first-line therapy; indomethacin is a second-line choice. In this case, the patient declined DMARDs after hearing they lowered the body’s ability to fight infection.) An RF level measured 6.74 IU/ml, which is within normal limits. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Barbara Kiersz, DO, 6835 Austin Center Blvd., Austin, TX 78731; [email protected].

A 44-year-old African-American woman with sickle cell trait presented to the clinic to establish care. She complained of polyarthralgias that she’d had since adolescence; the pain was worst in her right shoulder. She reported morning stiffness that lasted up to 8 hours, an intermittent facial rash, oral ulcers, joint edema (of which she had pictures on her phone), and photosensitivity. She took ibuprofen and acetaminophen as needed for pain. She once worked as a medical assistant but hadn’t been able to work since 2014 due to pain. She reported having been told as a teenager that she might have juvenile arthritis, but she didn’t recall ever having diagnostic tests performed or receiving treatment other than anti-inflammatories.

A couple of weeks after an initial visit with a rheumatologist, the patient returned to the family medicine clinic. She said she was upset that the specialist had x-rayed her hands, but had not checked her shoulder, which was the primary source of her pain. She also had pain in her hands, hips, feet, and knees.

On physical exam, the patient looked fatigued. A musculoskeletal exam revealed no joint effusions or edema, but was significant for right shoulder pain with reduced abduction to 90°. Gross motor strength was 5/5 in all 4 extremities. Laboratory testing revealed an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:160 and was negative for double-stranded DNA. Bilateral hand and foot x-rays showed no joint erosions. An x-ray of the right shoulder was obtained, which showed evidence of osteopenia and an erosion in the humeral head (FIGURES 1A and 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rheumatoid arthritis

The patient’s history of morning stiffness and the joint erosion observed on x-ray were highly suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

RA is a symmetric, inflammatory, peripheral polyarthritis of unknown etiology. It is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis, affecting 1% of the population worldwide.1 It causes cartilage and bone to erode, leading to the deformation and destruction of joints. If RA is left untreated or is unresponsive to therapy, it can eventually lead to loss of physical function.

Making the diagnosis

The distinctive signs of RA are joint erosions and rheumatoid nodules, which are often absent on initial presentation.

Classification criteria. The 2010 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) classification criteria for RA2 are based on the presence of synovitis in at least one joint, the absence of an alternative diagnosis that better explains the synovitis, and a cumulative score of at least 6/10 from the following 4 domains:

- Number and site of involved joints

- 2 to 10 large joints (shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, ankles)=1 point

- 1 to 3 small joints (metacarpophalangeal [MCP] joints, proximal interphalangeal [PIP] joints, 2nd-5th metatarsophalangeal joints, thumb interphalangeal joints, wrists)=2 points

- 4 to 10 small joints=3 points

- More than 10 joints (including at least 1 small joint)=5 points

- Serologic abnormality (rheumatoid factor [RF] and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide)

- Low positive=2 points

- High positive=3 points

- Elevated acute phase response (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] or C-reactive protein [CRP])=1 point

- Symptom duration of at least 6 weeks=1 point.

These criteria are best suited for early disease. For patients with longstanding symptoms, diagnosis is based on an erosive disease with a history of criteria fulfillment, or a currently inactive longstanding disease, with or without treatment, that has previously fulfilled the criteria.3

Continue to: The differential Dx is extensive

The differential Dx is extensive

The differential includes polyarthralgias such as viral polyarthritis, systemic rheumatic diseases, and osteoarthritis.

Viral polyarthritis is caused by rubella, parvovirus B194, alphaviruses, and hepatitis B. Symptoms can last from 3 days to several weeks, but rarely persist beyond 6 weeks; alphaviruses, however, can last 3 to 6 months.5 The common symptom triad includes fever, arthritis, and rash. Chikungunya is an example of an alphavirus that has become a global disease. Alphavirus arthritis can mimic seronegative RA and even satisfy the classification criteria for RA if the initial symptoms of fever and rash and history of travel to endemic regions are not appreciated.5

Systemic rheumatic diseases. Early RA may mimic the arthritis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome, dermatomyositis, or mixed connective tissue disease.6 In contrast to RA, these disorders generally have systemic features, such as rashes, dry mouth and eyes, myositis, or nephritis, and generate autobodies, which are not seen with RA. The CRP is often normal in patients with active SLE, even when the ESR is elevated.

Osteoarthritis (OA) can be confused with RA, particularly when small joints are involved. A thorough history helps elucidate the diagnosis. For example, OA of the fingers affects distal interphalangeal joints and is associated with Heberden’s nodes, while RA more commonly affects MCP and PIP joints. Swelling from OA is typically firm, while swelling due to RA is warm, boggy, and tender. Joint stiffness due to OA is worse with activity and generally lasts only a few minutes, while joint stiffness due to RA is worse at rest and lasts 30 minutes or more. X-rays show joint-space narrowing with OA, but no erosions or cysts. RF may be present at low levels in older patients with OA, while it is usually associated with high levels in patients with seropositive RA.

Continue to: Treat with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Treat with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Immediate treatment of RA with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is important to achieve control of the disease and prevent disability.

Our patient. We ordered a purified protein derivative skin test in preparation for the patient to start therapy with a DMARD. Our patient followed up with Rheumatology and was started on indomethacin, with an initial dose of 25 mg bid. (DMARDs are first-line therapy; indomethacin is a second-line choice. In this case, the patient declined DMARDs after hearing they lowered the body’s ability to fight infection.) An RF level measured 6.74 IU/ml, which is within normal limits. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Barbara Kiersz, DO, 6835 Austin Center Blvd., Austin, TX 78731; [email protected].

1. Rothschild BM, Turner KR, DeLuca MA. Symmetrical erosive peripheral polyarthritis in the Late Archaic Period of Alabama. Science. 1988;241:1498-1501.

2. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1580-1588.

3. Pincus T, Callahan LF. How many types of patients meet classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis? J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1385-1389.

4. Smith CA, Woolf AD, Lenci M. Parvoviruses: infections and arthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1987;13:249-263.

5. Miner JJ, Aw-Yeang HX, Fox JM, et al. Chikungunya viral arthritis in the United States: a mimic of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1214-1220.

6. Cronin ME. Musculoskeletal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1988;14:99-116.

1. Rothschild BM, Turner KR, DeLuca MA. Symmetrical erosive peripheral polyarthritis in the Late Archaic Period of Alabama. Science. 1988;241:1498-1501.

2. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1580-1588.

3. Pincus T, Callahan LF. How many types of patients meet classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis? J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1385-1389.

4. Smith CA, Woolf AD, Lenci M. Parvoviruses: infections and arthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1987;13:249-263.

5. Miner JJ, Aw-Yeang HX, Fox JM, et al. Chikungunya viral arthritis in the United States: a mimic of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1214-1220.

6. Cronin ME. Musculoskeletal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1988;14:99-116.

Changing growth on scalp

The FP thought the flat lesion (arrow) might be a nevus sebaceous (NS) and that the new area could be a malignant transformation.

The FP explained that a biopsy would be needed to learn more about the lesion. He explained that he would remove the area that was friable and bleeding along with part of the original flat lesion. After injecting the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, a shave biopsy was performed using a DermaBlade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The bleeding was stopped using aluminum chloride in water and some electrosurgery. The pathology results revealed syringocystadenoma papilliferum growing within an NS. This benign tumor is rare, but may develop within an NS.

The FP reassured the family that there was no skin cancer. The FP also referred the patient for full removal of the NS and any remnant of the syringocystadenoma papilliferum to avoid future growth and prevent additional bleeding.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP thought the flat lesion (arrow) might be a nevus sebaceous (NS) and that the new area could be a malignant transformation.

The FP explained that a biopsy would be needed to learn more about the lesion. He explained that he would remove the area that was friable and bleeding along with part of the original flat lesion. After injecting the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, a shave biopsy was performed using a DermaBlade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The bleeding was stopped using aluminum chloride in water and some electrosurgery. The pathology results revealed syringocystadenoma papilliferum growing within an NS. This benign tumor is rare, but may develop within an NS.

The FP reassured the family that there was no skin cancer. The FP also referred the patient for full removal of the NS and any remnant of the syringocystadenoma papilliferum to avoid future growth and prevent additional bleeding.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP thought the flat lesion (arrow) might be a nevus sebaceous (NS) and that the new area could be a malignant transformation.

The FP explained that a biopsy would be needed to learn more about the lesion. He explained that he would remove the area that was friable and bleeding along with part of the original flat lesion. After injecting the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, a shave biopsy was performed using a DermaBlade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The bleeding was stopped using aluminum chloride in water and some electrosurgery. The pathology results revealed syringocystadenoma papilliferum growing within an NS. This benign tumor is rare, but may develop within an NS.

The FP reassured the family that there was no skin cancer. The FP also referred the patient for full removal of the NS and any remnant of the syringocystadenoma papilliferum to avoid future growth and prevent additional bleeding.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growth on scalp

The family physician diagnosed a nevus sebaceous (NS) in this patient.

There are 3 stages of evolution paralleling the histologic differentiation of normal sebaceous glands:

- Infancy and young children. The lesion is smooth to slightly papillated, waxy, and hairless. (See Photo Rounds Friday, 6/15/18.)

- Puberty. Epidermal hyperplasia results in verrucous irregularity of the surface and coverage with numerous closely aggregated yellow-to-brown papules (this case).

- Development of secondary appendageal tumors. This occurs in 20% to 30% of patients. Most lesions are benign, but single (most commonly basal cell carcinoma) or multiple malignant tumors of both epidermal and adnexal origins may be seen. These malignancies are rarely seen in childhood.

In this case, a biopsy was not needed because the clinical picture was clear and no operative intervention was planned. When needed, a shave biopsy should provide adequate tissue for diagnosis because the pathology is epidermal and in the upper dermis. The NS need not be removed to prevent malignant transformation.

The FP explained that hair usually doesn’t grow where an NS is, and it was okay to proceed with observation only. He advised the patient’s father that if any changes were to occur, he would be happy to refer the child for surgical removal. The boy was not worried about the appearance of the NS and did not want to have surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The family physician diagnosed a nevus sebaceous (NS) in this patient.

There are 3 stages of evolution paralleling the histologic differentiation of normal sebaceous glands:

- Infancy and young children. The lesion is smooth to slightly papillated, waxy, and hairless. (See Photo Rounds Friday, 6/15/18.)

- Puberty. Epidermal hyperplasia results in verrucous irregularity of the surface and coverage with numerous closely aggregated yellow-to-brown papules (this case).

- Development of secondary appendageal tumors. This occurs in 20% to 30% of patients. Most lesions are benign, but single (most commonly basal cell carcinoma) or multiple malignant tumors of both epidermal and adnexal origins may be seen. These malignancies are rarely seen in childhood.

In this case, a biopsy was not needed because the clinical picture was clear and no operative intervention was planned. When needed, a shave biopsy should provide adequate tissue for diagnosis because the pathology is epidermal and in the upper dermis. The NS need not be removed to prevent malignant transformation.

The FP explained that hair usually doesn’t grow where an NS is, and it was okay to proceed with observation only. He advised the patient’s father that if any changes were to occur, he would be happy to refer the child for surgical removal. The boy was not worried about the appearance of the NS and did not want to have surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The family physician diagnosed a nevus sebaceous (NS) in this patient.

There are 3 stages of evolution paralleling the histologic differentiation of normal sebaceous glands:

- Infancy and young children. The lesion is smooth to slightly papillated, waxy, and hairless. (See Photo Rounds Friday, 6/15/18.)

- Puberty. Epidermal hyperplasia results in verrucous irregularity of the surface and coverage with numerous closely aggregated yellow-to-brown papules (this case).

- Development of secondary appendageal tumors. This occurs in 20% to 30% of patients. Most lesions are benign, but single (most commonly basal cell carcinoma) or multiple malignant tumors of both epidermal and adnexal origins may be seen. These malignancies are rarely seen in childhood.

In this case, a biopsy was not needed because the clinical picture was clear and no operative intervention was planned. When needed, a shave biopsy should provide adequate tissue for diagnosis because the pathology is epidermal and in the upper dermis. The NS need not be removed to prevent malignant transformation.

The FP explained that hair usually doesn’t grow where an NS is, and it was okay to proceed with observation only. He advised the patient’s father that if any changes were to occur, he would be happy to refer the child for surgical removal. The boy was not worried about the appearance of the NS and did not want to have surgery.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.