User login

Growth behind infant’s ear

The FP recognized the growth as an early nevus sebaceous (NS).

NS may be present at birth or noted in early childhood and occurs in males and females equally. In early stages of development, it appears skin-colored and waxy. Because of the potential for malignant transformation, particularly following puberty, many authors have recommended early complete plastic surgical excision. However, in a retrospective analysis of 757 cases of NS from 1996 to 2002 in children <16 years, investigators found no malignancies and questioned the need for prophylactic surgical removal.

The FP emphasized that this condition was benign and would likely get darker and more raised over time. He said that he would keep an eye on it during future visits and that the boy could choose to have it removed when he became an adult. The FP explained that reasons for removal include cosmetic issues and the prevention of malignant changes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized the growth as an early nevus sebaceous (NS).

NS may be present at birth or noted in early childhood and occurs in males and females equally. In early stages of development, it appears skin-colored and waxy. Because of the potential for malignant transformation, particularly following puberty, many authors have recommended early complete plastic surgical excision. However, in a retrospective analysis of 757 cases of NS from 1996 to 2002 in children <16 years, investigators found no malignancies and questioned the need for prophylactic surgical removal.

The FP emphasized that this condition was benign and would likely get darker and more raised over time. He said that he would keep an eye on it during future visits and that the boy could choose to have it removed when he became an adult. The FP explained that reasons for removal include cosmetic issues and the prevention of malignant changes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized the growth as an early nevus sebaceous (NS).

NS may be present at birth or noted in early childhood and occurs in males and females equally. In early stages of development, it appears skin-colored and waxy. Because of the potential for malignant transformation, particularly following puberty, many authors have recommended early complete plastic surgical excision. However, in a retrospective analysis of 757 cases of NS from 1996 to 2002 in children <16 years, investigators found no malignancies and questioned the need for prophylactic surgical removal.

The FP emphasized that this condition was benign and would likely get darker and more raised over time. He said that he would keep an eye on it during future visits and that the boy could choose to have it removed when he became an adult. The FP explained that reasons for removal include cosmetic issues and the prevention of malignant changes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growth on neck

The FP recognized the lesion as a linear epidermal nevus.

Epidermal nevi (EN) are congenital hamartomas of ectodermal origin that are uncommon (occurring in < 1% of newborns and children), sporadic, and usually present at birth, although they can appear in early childhood. EN are associated with disorders of the eye, nervous system, and musculoskeletal system in 10% to 30% of patients.

EN are linear, round or oblong, well circumscribed, elevated, and flat topped. EN are often yellow-tan to dark brown in color, with a surface that is uniformly velvety or warty. They most commonly occur on the head and neck, although they can occur on the trunk and proximal extremities.

The FP determined that the patient had no neurological, musculoskeletal, or vision problems that could be associated with a linear epidermal nevus syndrome and reassured the patient and his mother that the nevus was not dangerous and did not need to be removed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized the lesion as a linear epidermal nevus.

Epidermal nevi (EN) are congenital hamartomas of ectodermal origin that are uncommon (occurring in < 1% of newborns and children), sporadic, and usually present at birth, although they can appear in early childhood. EN are associated with disorders of the eye, nervous system, and musculoskeletal system in 10% to 30% of patients.

EN are linear, round or oblong, well circumscribed, elevated, and flat topped. EN are often yellow-tan to dark brown in color, with a surface that is uniformly velvety or warty. They most commonly occur on the head and neck, although they can occur on the trunk and proximal extremities.

The FP determined that the patient had no neurological, musculoskeletal, or vision problems that could be associated with a linear epidermal nevus syndrome and reassured the patient and his mother that the nevus was not dangerous and did not need to be removed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized the lesion as a linear epidermal nevus.

Epidermal nevi (EN) are congenital hamartomas of ectodermal origin that are uncommon (occurring in < 1% of newborns and children), sporadic, and usually present at birth, although they can appear in early childhood. EN are associated with disorders of the eye, nervous system, and musculoskeletal system in 10% to 30% of patients.

EN are linear, round or oblong, well circumscribed, elevated, and flat topped. EN are often yellow-tan to dark brown in color, with a surface that is uniformly velvety or warty. They most commonly occur on the head and neck, although they can occur on the trunk and proximal extremities.

The FP determined that the patient had no neurological, musculoskeletal, or vision problems that could be associated with a linear epidermal nevus syndrome and reassured the patient and his mother that the nevus was not dangerous and did not need to be removed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Epidermal nevus and nevus sebaceous. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:958-962.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Painless penile ulcer and tender inguinal lymphadenopathy

A 38-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a 2-day history of fever, general malaise, and a painless genital ulcer. He denied having any abdominal pain, myalgias, arthralgias, or other rashes. He had been treated about a month earlier on an outpatient basis with penicillin for a presumed diagnosis of syphilis, but his symptoms did not resolve. His medical history included well-controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, hypertension, anxiety, and fibromyalgia for which he took lisinopril, emtricitabine/tenofovir, metoprolol, and darunavir/cobicistat. He smoked a half-pack of cigarettes a day and had unprotected sex with men.

On physical examination, the patient was febrile (103.1° F) with otherwise normal vital signs. A genital examination revealed a nontender, irregularly shaped 8-mm ulcer at the base of the glans penis (FIGURE). Tender unilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted on the right side.

A chart review showed a normal CD4 count (obtained 2 months earlier). We were unable to access the results of his outpatient rapid plasma reagin test for syphilis. Due to the patient’s degree of pain from his lymphadenopathy, fever, and general malaise, he was admitted to the hospital for overnight observation.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lymphogranuloma venereum

Based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation, we suspected lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). A positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for Chlamydia trachomatis confirmed the diagnosis.

LGV is an infection caused by C trachomatis—specifically serovars L1, L2, and L3—that is transmitted through unprotected sex.1-3 During intercourse, the serovars cross the epithelial cells through breaks in the skin and enter the lymphatic system, often resulting in painful lymphadenopathy. LGV is more commonly reported in men (primarily men who have sex with men [MSM]), but can occur in either gender.4 The true incidence and prevalence of LGV are difficult to ascertain as the disease primarily occurs in tropical areas, but outbreaks in the United States occur predominantly in patients infected with HIV.

The 3 stages of infection

Following an incubation period of 3 to 30 days, LGV progresses through 3 stages. The first stage involves a small, painless lesion at the inoculation site—usually the prepuce or glans of the penis or the vulva or vaginal wall. The lesion typically heals in about one week.1,2,4

Two to 6 weeks later, LGV enters the second phase, characterized by painful unilateral inguinal or femoral lymphadenopathy or proctitis. Inguinal and femoral lymphadenopathy is more common in men.1,4 The “groove sign”—lymphadenopathy occurring above and below the inguinal ligament—is seen in 10% to 20% of men with LGV.1,3 In women, lymphatic drainage occurs in the retroperitoneal or intra-abdominal nodes and may result in abdominal or back pain.1,4 Proctitis is reported primarily in women and in MSM.1,4

Tertiary LGV (aka genitoanorectal syndrome) is also more common in women and MSM, due to the location of the involved lymphatics. In this stage, chronic inflammation causes scarring and destruction of tissue.1,4 Left untreated, LGV can lead to lymphatic obstruction, deep tissue abscesses, chronic pain, strictures, or fistulas.1,3,4

Continue to: Other genital ulcers can mimic LGV

Other genital ulcers can mimic LGV

LGV can be confused with other causes of genital ulcers (such as syphilis, chancroid, herpes simplex virus, and Behçet’s disease). Identification of the causal bacteria is often needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Syphilis, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, initially manifests as a chancre (a single, well-demarcated, painless ulcer). It is less commonly associated with inguinal lymphadenopathy and can be diagnosed via serologic testing.5,6

Chancroid is caused by Haemophilus ducreyi and manifests as a painful ulcer with a friable base covered with a necrotic exudate. It can be associated with tender unilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy.5 Due to the widespread availability of culture media to test for H ducreyi, the diagnosis of chancroid is based on the clinical exam plus a handful of clinical criteria: painful genital ulcers, no evidence of T

HSV, the most common cause of genital ulcers in the United States,5 typically manifests with multiple vesicular painful lesions, with or without lymphadenopathy. Constitutional symptoms, including fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias, occur in 66% of females and 40% of males.5,7 Identification of HSV on culture or PCR can confirm the diagnosis.5

Behçet’s disease is a noninfectious syndrome associated with intermittent arthritis, recurrent painful oral and genital ulcers, uveitis, and skin lesions. While most symptoms of Behçet’s are self-limited, recurrent uveitis can result in blindness. A biopsy may be warranted to diagnose Behçet’s disease; the results may show diffuse arteritis with venulitis.5,8

Continue to: NAAT is recommended to confirm the diagnosis

NAAT is recommended to confirm the diagnosis

In the outpatient setting, diagnosis of LGV relies on physical exam, clinical presentation, confirmation of infection, and exclusion of other causes of genital ulcer, lymphadenopathy, and proctitis.3 Diagnostic tests include culture identification of C trachomatis, visualization of inclusion bodies on immunofluorescence of bubo aspirate, and positive serology for C trachomatis.1-3 (Serology to differentiate LGV from non-LGV C trachomatis serovars is difficult and not widely available.)

Recommendations regarding lab studies have shifted away from serologic testing and toward the use of NAAT. NAAT via PCR has a sensitivity and specificity comparable to invasive testing methods: 83% and 99.5% with urine samples and 86% and 99.6% with cervical samples, respectively.9 NAAT has a sensitivity and specificity that is superior to culture for detecting chlamydia in rectal specimens10 and is preferred by patients because it doesn’t require a pelvic exam or a urethral swab.

Treat with antibiotics

Oral antibiotics are the treatment of choice for LGV. Standard treatment includes doxycycline 100 mg bid for 21 days. Women who are pregnant or lactating may alternatively be treated with macrolides (eg, erythromycin).1,2,4 Buboes may be aspirated for pain relief and to prevent the development of ulcerations or fistulas.3,4

Our patient was started on oral doxycycline, which resolved his fever and reduced the size of his ulcer. He was discharged on oral doxycycline and continued on the full 21-day course. Two weeks later, the ulcer and lymphadenopathy had completely resolved. On follow-up in our office, the resident physician who treated the patient in the hospital discussed future use of safe sexual practices.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey Walden, MD, Cone Health Family Medicine Residency, 1125 North Church Street, Greensboro, NC 27401; [email protected].

1. Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect.

2. Roett MA, Mayor MT, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of genital ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:254-262.

3. Stoner BP, Cohen SE. Lymphogranuloma venereum 2015: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:S865-S873.

4. Ceovic R, Gulin SJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Infect Drug Resist. 2015;8:39-47.

5. Roett MA, Mayor MT, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of genital ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:254-262.

6. Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, et al. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:433-440.

7. Kimberlin DW, Rouse DJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1970-1977.

8. Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, et al. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291.

9. Cook RL, Hutchison SL, Østergaard L, et al. Systematic review: noninvasive testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:914-925.

10. Geisler WM. Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis infections in adolescents and adults: summary of evidence reviewed for the 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53 suppl 3:s92-s98.

A 38-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a 2-day history of fever, general malaise, and a painless genital ulcer. He denied having any abdominal pain, myalgias, arthralgias, or other rashes. He had been treated about a month earlier on an outpatient basis with penicillin for a presumed diagnosis of syphilis, but his symptoms did not resolve. His medical history included well-controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, hypertension, anxiety, and fibromyalgia for which he took lisinopril, emtricitabine/tenofovir, metoprolol, and darunavir/cobicistat. He smoked a half-pack of cigarettes a day and had unprotected sex with men.

On physical examination, the patient was febrile (103.1° F) with otherwise normal vital signs. A genital examination revealed a nontender, irregularly shaped 8-mm ulcer at the base of the glans penis (FIGURE). Tender unilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted on the right side.

A chart review showed a normal CD4 count (obtained 2 months earlier). We were unable to access the results of his outpatient rapid plasma reagin test for syphilis. Due to the patient’s degree of pain from his lymphadenopathy, fever, and general malaise, he was admitted to the hospital for overnight observation.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lymphogranuloma venereum

Based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation, we suspected lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). A positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for Chlamydia trachomatis confirmed the diagnosis.

LGV is an infection caused by C trachomatis—specifically serovars L1, L2, and L3—that is transmitted through unprotected sex.1-3 During intercourse, the serovars cross the epithelial cells through breaks in the skin and enter the lymphatic system, often resulting in painful lymphadenopathy. LGV is more commonly reported in men (primarily men who have sex with men [MSM]), but can occur in either gender.4 The true incidence and prevalence of LGV are difficult to ascertain as the disease primarily occurs in tropical areas, but outbreaks in the United States occur predominantly in patients infected with HIV.

The 3 stages of infection

Following an incubation period of 3 to 30 days, LGV progresses through 3 stages. The first stage involves a small, painless lesion at the inoculation site—usually the prepuce or glans of the penis or the vulva or vaginal wall. The lesion typically heals in about one week.1,2,4

Two to 6 weeks later, LGV enters the second phase, characterized by painful unilateral inguinal or femoral lymphadenopathy or proctitis. Inguinal and femoral lymphadenopathy is more common in men.1,4 The “groove sign”—lymphadenopathy occurring above and below the inguinal ligament—is seen in 10% to 20% of men with LGV.1,3 In women, lymphatic drainage occurs in the retroperitoneal or intra-abdominal nodes and may result in abdominal or back pain.1,4 Proctitis is reported primarily in women and in MSM.1,4

Tertiary LGV (aka genitoanorectal syndrome) is also more common in women and MSM, due to the location of the involved lymphatics. In this stage, chronic inflammation causes scarring and destruction of tissue.1,4 Left untreated, LGV can lead to lymphatic obstruction, deep tissue abscesses, chronic pain, strictures, or fistulas.1,3,4

Continue to: Other genital ulcers can mimic LGV

Other genital ulcers can mimic LGV

LGV can be confused with other causes of genital ulcers (such as syphilis, chancroid, herpes simplex virus, and Behçet’s disease). Identification of the causal bacteria is often needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Syphilis, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, initially manifests as a chancre (a single, well-demarcated, painless ulcer). It is less commonly associated with inguinal lymphadenopathy and can be diagnosed via serologic testing.5,6

Chancroid is caused by Haemophilus ducreyi and manifests as a painful ulcer with a friable base covered with a necrotic exudate. It can be associated with tender unilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy.5 Due to the widespread availability of culture media to test for H ducreyi, the diagnosis of chancroid is based on the clinical exam plus a handful of clinical criteria: painful genital ulcers, no evidence of T

HSV, the most common cause of genital ulcers in the United States,5 typically manifests with multiple vesicular painful lesions, with or without lymphadenopathy. Constitutional symptoms, including fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias, occur in 66% of females and 40% of males.5,7 Identification of HSV on culture or PCR can confirm the diagnosis.5

Behçet’s disease is a noninfectious syndrome associated with intermittent arthritis, recurrent painful oral and genital ulcers, uveitis, and skin lesions. While most symptoms of Behçet’s are self-limited, recurrent uveitis can result in blindness. A biopsy may be warranted to diagnose Behçet’s disease; the results may show diffuse arteritis with venulitis.5,8

Continue to: NAAT is recommended to confirm the diagnosis

NAAT is recommended to confirm the diagnosis

In the outpatient setting, diagnosis of LGV relies on physical exam, clinical presentation, confirmation of infection, and exclusion of other causes of genital ulcer, lymphadenopathy, and proctitis.3 Diagnostic tests include culture identification of C trachomatis, visualization of inclusion bodies on immunofluorescence of bubo aspirate, and positive serology for C trachomatis.1-3 (Serology to differentiate LGV from non-LGV C trachomatis serovars is difficult and not widely available.)

Recommendations regarding lab studies have shifted away from serologic testing and toward the use of NAAT. NAAT via PCR has a sensitivity and specificity comparable to invasive testing methods: 83% and 99.5% with urine samples and 86% and 99.6% with cervical samples, respectively.9 NAAT has a sensitivity and specificity that is superior to culture for detecting chlamydia in rectal specimens10 and is preferred by patients because it doesn’t require a pelvic exam or a urethral swab.

Treat with antibiotics

Oral antibiotics are the treatment of choice for LGV. Standard treatment includes doxycycline 100 mg bid for 21 days. Women who are pregnant or lactating may alternatively be treated with macrolides (eg, erythromycin).1,2,4 Buboes may be aspirated for pain relief and to prevent the development of ulcerations or fistulas.3,4

Our patient was started on oral doxycycline, which resolved his fever and reduced the size of his ulcer. He was discharged on oral doxycycline and continued on the full 21-day course. Two weeks later, the ulcer and lymphadenopathy had completely resolved. On follow-up in our office, the resident physician who treated the patient in the hospital discussed future use of safe sexual practices.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey Walden, MD, Cone Health Family Medicine Residency, 1125 North Church Street, Greensboro, NC 27401; [email protected].

A 38-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a 2-day history of fever, general malaise, and a painless genital ulcer. He denied having any abdominal pain, myalgias, arthralgias, or other rashes. He had been treated about a month earlier on an outpatient basis with penicillin for a presumed diagnosis of syphilis, but his symptoms did not resolve. His medical history included well-controlled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, hypertension, anxiety, and fibromyalgia for which he took lisinopril, emtricitabine/tenofovir, metoprolol, and darunavir/cobicistat. He smoked a half-pack of cigarettes a day and had unprotected sex with men.

On physical examination, the patient was febrile (103.1° F) with otherwise normal vital signs. A genital examination revealed a nontender, irregularly shaped 8-mm ulcer at the base of the glans penis (FIGURE). Tender unilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted on the right side.

A chart review showed a normal CD4 count (obtained 2 months earlier). We were unable to access the results of his outpatient rapid plasma reagin test for syphilis. Due to the patient’s degree of pain from his lymphadenopathy, fever, and general malaise, he was admitted to the hospital for overnight observation.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lymphogranuloma venereum

Based on the patient’s history and clinical presentation, we suspected lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). A positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for Chlamydia trachomatis confirmed the diagnosis.

LGV is an infection caused by C trachomatis—specifically serovars L1, L2, and L3—that is transmitted through unprotected sex.1-3 During intercourse, the serovars cross the epithelial cells through breaks in the skin and enter the lymphatic system, often resulting in painful lymphadenopathy. LGV is more commonly reported in men (primarily men who have sex with men [MSM]), but can occur in either gender.4 The true incidence and prevalence of LGV are difficult to ascertain as the disease primarily occurs in tropical areas, but outbreaks in the United States occur predominantly in patients infected with HIV.

The 3 stages of infection

Following an incubation period of 3 to 30 days, LGV progresses through 3 stages. The first stage involves a small, painless lesion at the inoculation site—usually the prepuce or glans of the penis or the vulva or vaginal wall. The lesion typically heals in about one week.1,2,4

Two to 6 weeks later, LGV enters the second phase, characterized by painful unilateral inguinal or femoral lymphadenopathy or proctitis. Inguinal and femoral lymphadenopathy is more common in men.1,4 The “groove sign”—lymphadenopathy occurring above and below the inguinal ligament—is seen in 10% to 20% of men with LGV.1,3 In women, lymphatic drainage occurs in the retroperitoneal or intra-abdominal nodes and may result in abdominal or back pain.1,4 Proctitis is reported primarily in women and in MSM.1,4

Tertiary LGV (aka genitoanorectal syndrome) is also more common in women and MSM, due to the location of the involved lymphatics. In this stage, chronic inflammation causes scarring and destruction of tissue.1,4 Left untreated, LGV can lead to lymphatic obstruction, deep tissue abscesses, chronic pain, strictures, or fistulas.1,3,4

Continue to: Other genital ulcers can mimic LGV

Other genital ulcers can mimic LGV

LGV can be confused with other causes of genital ulcers (such as syphilis, chancroid, herpes simplex virus, and Behçet’s disease). Identification of the causal bacteria is often needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Syphilis, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, initially manifests as a chancre (a single, well-demarcated, painless ulcer). It is less commonly associated with inguinal lymphadenopathy and can be diagnosed via serologic testing.5,6

Chancroid is caused by Haemophilus ducreyi and manifests as a painful ulcer with a friable base covered with a necrotic exudate. It can be associated with tender unilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy.5 Due to the widespread availability of culture media to test for H ducreyi, the diagnosis of chancroid is based on the clinical exam plus a handful of clinical criteria: painful genital ulcers, no evidence of T

HSV, the most common cause of genital ulcers in the United States,5 typically manifests with multiple vesicular painful lesions, with or without lymphadenopathy. Constitutional symptoms, including fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias, occur in 66% of females and 40% of males.5,7 Identification of HSV on culture or PCR can confirm the diagnosis.5

Behçet’s disease is a noninfectious syndrome associated with intermittent arthritis, recurrent painful oral and genital ulcers, uveitis, and skin lesions. While most symptoms of Behçet’s are self-limited, recurrent uveitis can result in blindness. A biopsy may be warranted to diagnose Behçet’s disease; the results may show diffuse arteritis with venulitis.5,8

Continue to: NAAT is recommended to confirm the diagnosis

NAAT is recommended to confirm the diagnosis

In the outpatient setting, diagnosis of LGV relies on physical exam, clinical presentation, confirmation of infection, and exclusion of other causes of genital ulcer, lymphadenopathy, and proctitis.3 Diagnostic tests include culture identification of C trachomatis, visualization of inclusion bodies on immunofluorescence of bubo aspirate, and positive serology for C trachomatis.1-3 (Serology to differentiate LGV from non-LGV C trachomatis serovars is difficult and not widely available.)

Recommendations regarding lab studies have shifted away from serologic testing and toward the use of NAAT. NAAT via PCR has a sensitivity and specificity comparable to invasive testing methods: 83% and 99.5% with urine samples and 86% and 99.6% with cervical samples, respectively.9 NAAT has a sensitivity and specificity that is superior to culture for detecting chlamydia in rectal specimens10 and is preferred by patients because it doesn’t require a pelvic exam or a urethral swab.

Treat with antibiotics

Oral antibiotics are the treatment of choice for LGV. Standard treatment includes doxycycline 100 mg bid for 21 days. Women who are pregnant or lactating may alternatively be treated with macrolides (eg, erythromycin).1,2,4 Buboes may be aspirated for pain relief and to prevent the development of ulcerations or fistulas.3,4

Our patient was started on oral doxycycline, which resolved his fever and reduced the size of his ulcer. He was discharged on oral doxycycline and continued on the full 21-day course. Two weeks later, the ulcer and lymphadenopathy had completely resolved. On follow-up in our office, the resident physician who treated the patient in the hospital discussed future use of safe sexual practices.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeffrey Walden, MD, Cone Health Family Medicine Residency, 1125 North Church Street, Greensboro, NC 27401; [email protected].

1. Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect.

2. Roett MA, Mayor MT, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of genital ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:254-262.

3. Stoner BP, Cohen SE. Lymphogranuloma venereum 2015: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:S865-S873.

4. Ceovic R, Gulin SJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Infect Drug Resist. 2015;8:39-47.

5. Roett MA, Mayor MT, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of genital ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:254-262.

6. Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, et al. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:433-440.

7. Kimberlin DW, Rouse DJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1970-1977.

8. Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, et al. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291.

9. Cook RL, Hutchison SL, Østergaard L, et al. Systematic review: noninvasive testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:914-925.

10. Geisler WM. Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis infections in adolescents and adults: summary of evidence reviewed for the 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53 suppl 3:s92-s98.

1. Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect.

2. Roett MA, Mayor MT, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of genital ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:254-262.

3. Stoner BP, Cohen SE. Lymphogranuloma venereum 2015: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:S865-S873.

4. Ceovic R, Gulin SJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Infect Drug Resist. 2015;8:39-47.

5. Roett MA, Mayor MT, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of genital ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:254-262.

6. Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, et al. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:433-440.

7. Kimberlin DW, Rouse DJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1970-1977.

8. Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, et al. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291.

9. Cook RL, Hutchison SL, Østergaard L, et al. Systematic review: noninvasive testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:914-925.

10. Geisler WM. Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis infections in adolescents and adults: summary of evidence reviewed for the 2010 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53 suppl 3:s92-s98.

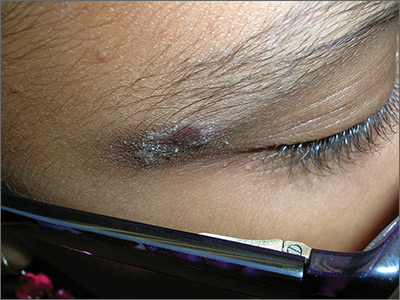

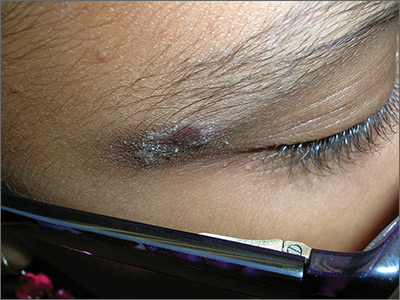

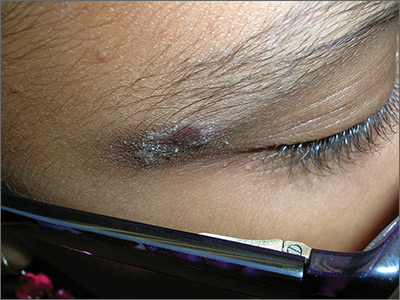

Rash on eyebrows

The FP recognized that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), based on the clinical presentation. The distribution of the erythema, scale, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was highly suggestive of an ACD to nickel. In this case, the nickel in the patient’s eyeglasses and the snaps on her pants were the culprit. The plaque near the patient’s eye was actually in the shape of the metal on the inside of her glasses.

ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction in which a foreign substance comes into contact with the skin and is linked to skin proteins; this forms an antigen complex, leading to sensitization. When the epidermis is re-exposed to the antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade, leading to the skin changes seen in ACD.

Contact dermatitis can sometimes be diagnosed clinically with a good history and physical exam. However, there are many cases in which patch testing is needed to find the offending allergens or confirm the suspicion regarding a specific allergen. The differential diagnosis includes cutaneous candidiasis, impetigo, plaque psoriasis, and seborrheic dermatitis.

Patients with ACD should avoid the allergen that is causing the reaction. In cases of nickel ACD, the patient may cover the metal tab of his or her jeans with an iron-on patch or a few coats of clear nail polish. Fortunately, some jeans manufacturers now make nickel-free metal tabs (eg, Levis’s).

Cool compresses can soothe the symptoms of acute cases of ACD. Localized acute ACD lesions respond best to mid-potency (eg, 0.1% triamcinolone) to high-potency (eg, 0.05% clobetasol) topical steroids. On areas of thinner skin, lower-potency steroids such as desonide ointment can minimize the risk of skin atrophy.

In this case, the FP recommended that the patient get glasses that were nickel free and explained how to avoid the nickel that still exists in some pants. She was also given desonide 0.05% cream to apply to the affected area for symptomatic relief.

Adapted from: Usatine RP, Jacob SE. Rash on eyebrows and periumbilical region. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:45-47.

The FP recognized that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), based on the clinical presentation. The distribution of the erythema, scale, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was highly suggestive of an ACD to nickel. In this case, the nickel in the patient’s eyeglasses and the snaps on her pants were the culprit. The plaque near the patient’s eye was actually in the shape of the metal on the inside of her glasses.

ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction in which a foreign substance comes into contact with the skin and is linked to skin proteins; this forms an antigen complex, leading to sensitization. When the epidermis is re-exposed to the antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade, leading to the skin changes seen in ACD.

Contact dermatitis can sometimes be diagnosed clinically with a good history and physical exam. However, there are many cases in which patch testing is needed to find the offending allergens or confirm the suspicion regarding a specific allergen. The differential diagnosis includes cutaneous candidiasis, impetigo, plaque psoriasis, and seborrheic dermatitis.

Patients with ACD should avoid the allergen that is causing the reaction. In cases of nickel ACD, the patient may cover the metal tab of his or her jeans with an iron-on patch or a few coats of clear nail polish. Fortunately, some jeans manufacturers now make nickel-free metal tabs (eg, Levis’s).

Cool compresses can soothe the symptoms of acute cases of ACD. Localized acute ACD lesions respond best to mid-potency (eg, 0.1% triamcinolone) to high-potency (eg, 0.05% clobetasol) topical steroids. On areas of thinner skin, lower-potency steroids such as desonide ointment can minimize the risk of skin atrophy.

In this case, the FP recommended that the patient get glasses that were nickel free and explained how to avoid the nickel that still exists in some pants. She was also given desonide 0.05% cream to apply to the affected area for symptomatic relief.

Adapted from: Usatine RP, Jacob SE. Rash on eyebrows and periumbilical region. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:45-47.

The FP recognized that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), based on the clinical presentation. The distribution of the erythema, scale, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was highly suggestive of an ACD to nickel. In this case, the nickel in the patient’s eyeglasses and the snaps on her pants were the culprit. The plaque near the patient’s eye was actually in the shape of the metal on the inside of her glasses.

ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction in which a foreign substance comes into contact with the skin and is linked to skin proteins; this forms an antigen complex, leading to sensitization. When the epidermis is re-exposed to the antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade, leading to the skin changes seen in ACD.

Contact dermatitis can sometimes be diagnosed clinically with a good history and physical exam. However, there are many cases in which patch testing is needed to find the offending allergens or confirm the suspicion regarding a specific allergen. The differential diagnosis includes cutaneous candidiasis, impetigo, plaque psoriasis, and seborrheic dermatitis.

Patients with ACD should avoid the allergen that is causing the reaction. In cases of nickel ACD, the patient may cover the metal tab of his or her jeans with an iron-on patch or a few coats of clear nail polish. Fortunately, some jeans manufacturers now make nickel-free metal tabs (eg, Levis’s).

Cool compresses can soothe the symptoms of acute cases of ACD. Localized acute ACD lesions respond best to mid-potency (eg, 0.1% triamcinolone) to high-potency (eg, 0.05% clobetasol) topical steroids. On areas of thinner skin, lower-potency steroids such as desonide ointment can minimize the risk of skin atrophy.

In this case, the FP recommended that the patient get glasses that were nickel free and explained how to avoid the nickel that still exists in some pants. She was also given desonide 0.05% cream to apply to the affected area for symptomatic relief.

Adapted from: Usatine RP, Jacob SE. Rash on eyebrows and periumbilical region. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:45-47.

Large dark discoloration on the back

The FP recognized that this child had a large bathing trunk nevus with multiple small melanocytic satellite lesions on her arms.

He explained to the worried parents that their daughter had a bathing trunk nevus and that a local expert was needed. The FP consulted a local dermatologist, who subsequently explained to the parents that there was a significant risk of cutaneous melanoma if nothing was done about this large congenital nevus. The dermatologist indicated that while removal could decrease that risk, the process would require multiple large surgeries by a plastic surgeon. She also explained that a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain would be needed at about 6 months to look for neurocutaneous melanosis, which can cause seizures, hydrocephalus, and a central nervous system melanoma.

The parents were conflicted about whether to put their child through a series of massive surgeries or to accept the higher risk of melanoma and proceed with careful monitoring by the dermatologist. (No additional details on how this case resolved are available—Editor.)

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that this child had a large bathing trunk nevus with multiple small melanocytic satellite lesions on her arms.

He explained to the worried parents that their daughter had a bathing trunk nevus and that a local expert was needed. The FP consulted a local dermatologist, who subsequently explained to the parents that there was a significant risk of cutaneous melanoma if nothing was done about this large congenital nevus. The dermatologist indicated that while removal could decrease that risk, the process would require multiple large surgeries by a plastic surgeon. She also explained that a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain would be needed at about 6 months to look for neurocutaneous melanosis, which can cause seizures, hydrocephalus, and a central nervous system melanoma.

The parents were conflicted about whether to put their child through a series of massive surgeries or to accept the higher risk of melanoma and proceed with careful monitoring by the dermatologist. (No additional details on how this case resolved are available—Editor.)

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized that this child had a large bathing trunk nevus with multiple small melanocytic satellite lesions on her arms.

He explained to the worried parents that their daughter had a bathing trunk nevus and that a local expert was needed. The FP consulted a local dermatologist, who subsequently explained to the parents that there was a significant risk of cutaneous melanoma if nothing was done about this large congenital nevus. The dermatologist indicated that while removal could decrease that risk, the process would require multiple large surgeries by a plastic surgeon. She also explained that a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain would be needed at about 6 months to look for neurocutaneous melanosis, which can cause seizures, hydrocephalus, and a central nervous system melanoma.

The parents were conflicted about whether to put their child through a series of massive surgeries or to accept the higher risk of melanoma and proceed with careful monitoring by the dermatologist. (No additional details on how this case resolved are available—Editor.)

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

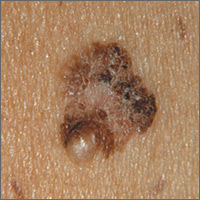

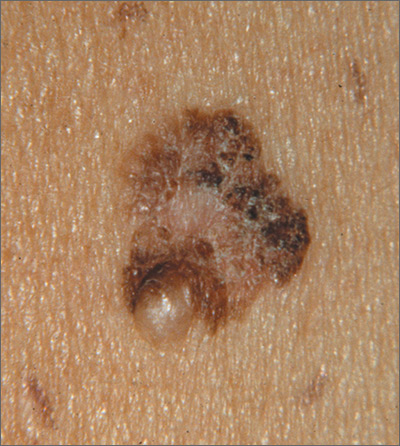

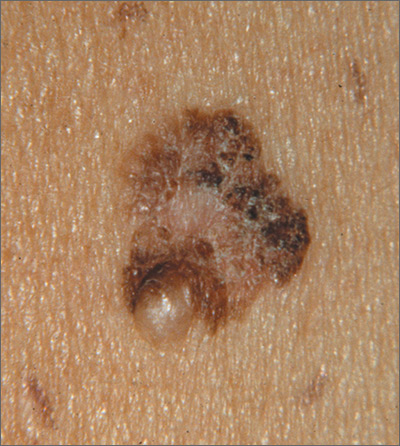

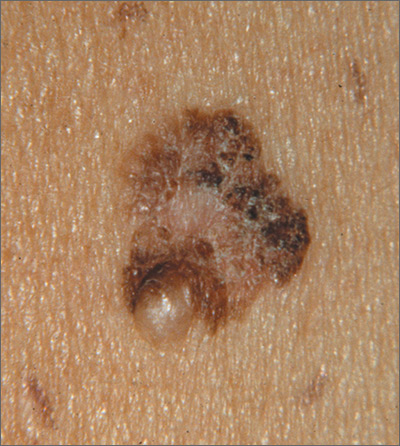

Changing mole on arm

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma.

He thought through the ABCDEs of melanoma and saw that it was Asymmetric, had an irregular Border, had varied Colors, the Diameter was larger than 6 mm, and it was Evolving. The FP also noted that one area was elevated and another area (the center) seemed to be regressing. Using his dermatoscope, he noted strong evidence of regression in the center and an “atypical network.” He told the patient that this was very suspicious for melanoma and recommended a skin biopsy without delay. The patient agreed and after local anesthesia with lidocaine with epinephrine, a saucerization biopsy was performed using a DermaBlade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP easily removed all of the visible tumor with the saucerization (deep shave). The bleeding was stopped with topical aluminum chloride, and the specimen was sent in formalin to the pathologist. The pathology report came back as a melanoma of 2.1 mm depth arising in a pre-existing nevus.

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for sentinel lymph node biopsy and excision with wide margins.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma.

He thought through the ABCDEs of melanoma and saw that it was Asymmetric, had an irregular Border, had varied Colors, the Diameter was larger than 6 mm, and it was Evolving. The FP also noted that one area was elevated and another area (the center) seemed to be regressing. Using his dermatoscope, he noted strong evidence of regression in the center and an “atypical network.” He told the patient that this was very suspicious for melanoma and recommended a skin biopsy without delay. The patient agreed and after local anesthesia with lidocaine with epinephrine, a saucerization biopsy was performed using a DermaBlade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP easily removed all of the visible tumor with the saucerization (deep shave). The bleeding was stopped with topical aluminum chloride, and the specimen was sent in formalin to the pathologist. The pathology report came back as a melanoma of 2.1 mm depth arising in a pre-existing nevus.

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for sentinel lymph node biopsy and excision with wide margins.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma.

He thought through the ABCDEs of melanoma and saw that it was Asymmetric, had an irregular Border, had varied Colors, the Diameter was larger than 6 mm, and it was Evolving. The FP also noted that one area was elevated and another area (the center) seemed to be regressing. Using his dermatoscope, he noted strong evidence of regression in the center and an “atypical network.” He told the patient that this was very suspicious for melanoma and recommended a skin biopsy without delay. The patient agreed and after local anesthesia with lidocaine with epinephrine, a saucerization biopsy was performed using a DermaBlade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The FP easily removed all of the visible tumor with the saucerization (deep shave). The bleeding was stopped with topical aluminum chloride, and the specimen was sent in formalin to the pathologist. The pathology report came back as a melanoma of 2.1 mm depth arising in a pre-existing nevus.

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for sentinel lymph node biopsy and excision with wide margins.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Growing mole on breast

The FP recognized this lesion as a congenital nevus.

He was aware that nevi might become more raised during early adulthood, though this was not necessarily a sign of malignant degeneration. He looked at the nevus carefully and saw that it was relatively symmetrical with one predominant color and a light brown coloration on the left edge. (The patient stated it had always been this way.) The surface texture, which could be described as mamillated, was not unusual for congenital nevi. The FP examined the nevus using a dermatoscope and did not see any melanoma-specific structures.

The FP encouraged the patient to monitor the nevus and return for further evaluation if there were any changes or symptoms. He also offered her the option of a biopsy, but stated that it was not medically required. The patient noted that the changes of increased height of the congenital nevus had been very slow over the past 2 years, and she was willing to keep an eye on it. The patient returned in 6 months, and there were no visible changes to the congenital nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this lesion as a congenital nevus.

He was aware that nevi might become more raised during early adulthood, though this was not necessarily a sign of malignant degeneration. He looked at the nevus carefully and saw that it was relatively symmetrical with one predominant color and a light brown coloration on the left edge. (The patient stated it had always been this way.) The surface texture, which could be described as mamillated, was not unusual for congenital nevi. The FP examined the nevus using a dermatoscope and did not see any melanoma-specific structures.

The FP encouraged the patient to monitor the nevus and return for further evaluation if there were any changes or symptoms. He also offered her the option of a biopsy, but stated that it was not medically required. The patient noted that the changes of increased height of the congenital nevus had been very slow over the past 2 years, and she was willing to keep an eye on it. The patient returned in 6 months, and there were no visible changes to the congenital nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this lesion as a congenital nevus.

He was aware that nevi might become more raised during early adulthood, though this was not necessarily a sign of malignant degeneration. He looked at the nevus carefully and saw that it was relatively symmetrical with one predominant color and a light brown coloration on the left edge. (The patient stated it had always been this way.) The surface texture, which could be described as mamillated, was not unusual for congenital nevi. The FP examined the nevus using a dermatoscope and did not see any melanoma-specific structures.

The FP encouraged the patient to monitor the nevus and return for further evaluation if there were any changes or symptoms. He also offered her the option of a biopsy, but stated that it was not medically required. The patient noted that the changes of increased height of the congenital nevus had been very slow over the past 2 years, and she was willing to keep an eye on it. The patient returned in 6 months, and there were no visible changes to the congenital nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Brown spot on right foot

The FP recognized this as a benign congenital nevus.

While most congenital nevi are visible at birth, there are some that appear in the first year of life and are known as tardive congenital nevi. The FP used a dermatoscope to look at this nevus and found that its features were benign.

The parents wondered whether this needed to be removed to prevent it from becoming skin cancer in the future. The FP reassured them that the risk of melanoma from this one nevus was too small to warrant a prophylactic surgical excision. The parents agreed to the standard 6-month immunizations.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this as a benign congenital nevus.

While most congenital nevi are visible at birth, there are some that appear in the first year of life and are known as tardive congenital nevi. The FP used a dermatoscope to look at this nevus and found that its features were benign.

The parents wondered whether this needed to be removed to prevent it from becoming skin cancer in the future. The FP reassured them that the risk of melanoma from this one nevus was too small to warrant a prophylactic surgical excision. The parents agreed to the standard 6-month immunizations.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this as a benign congenital nevus.

While most congenital nevi are visible at birth, there are some that appear in the first year of life and are known as tardive congenital nevi. The FP used a dermatoscope to look at this nevus and found that its features were benign.

The parents wondered whether this needed to be removed to prevent it from becoming skin cancer in the future. The FP reassured them that the risk of melanoma from this one nevus was too small to warrant a prophylactic surgical excision. The parents agreed to the standard 6-month immunizations.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

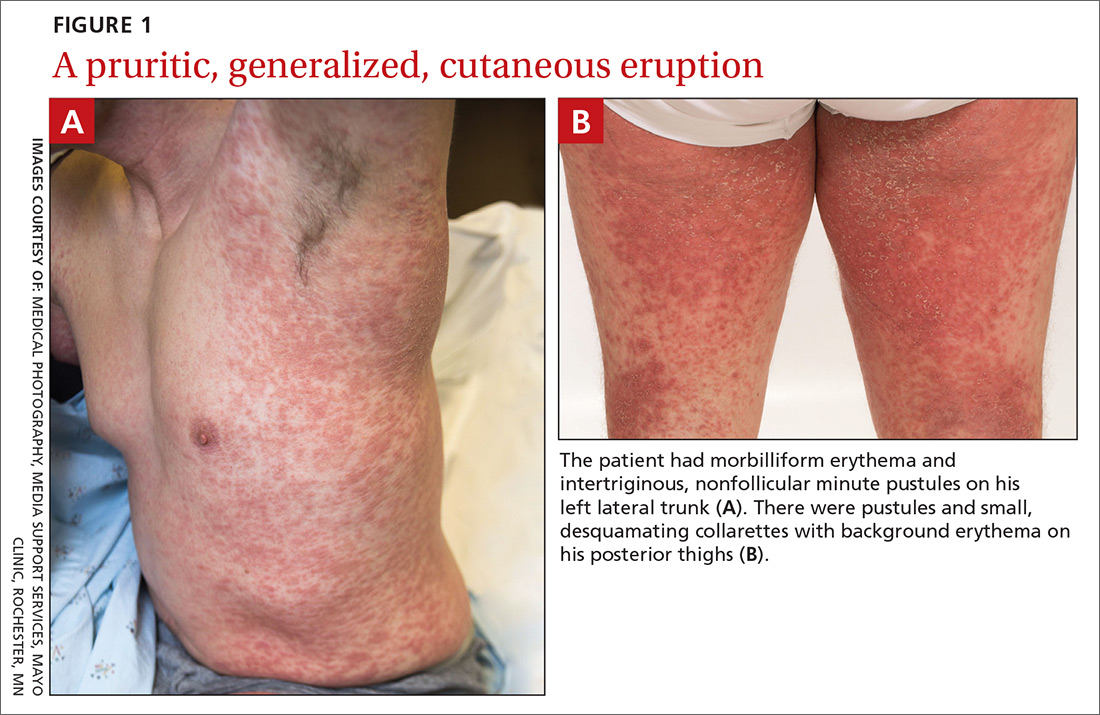

Generalized pustular eruption

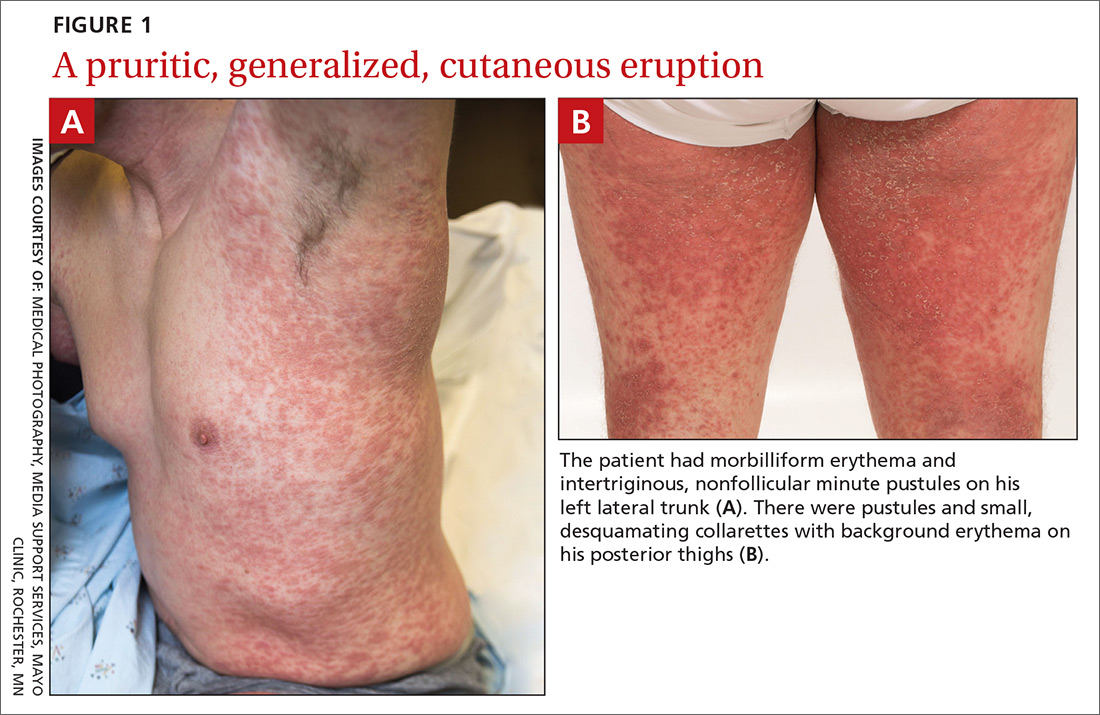

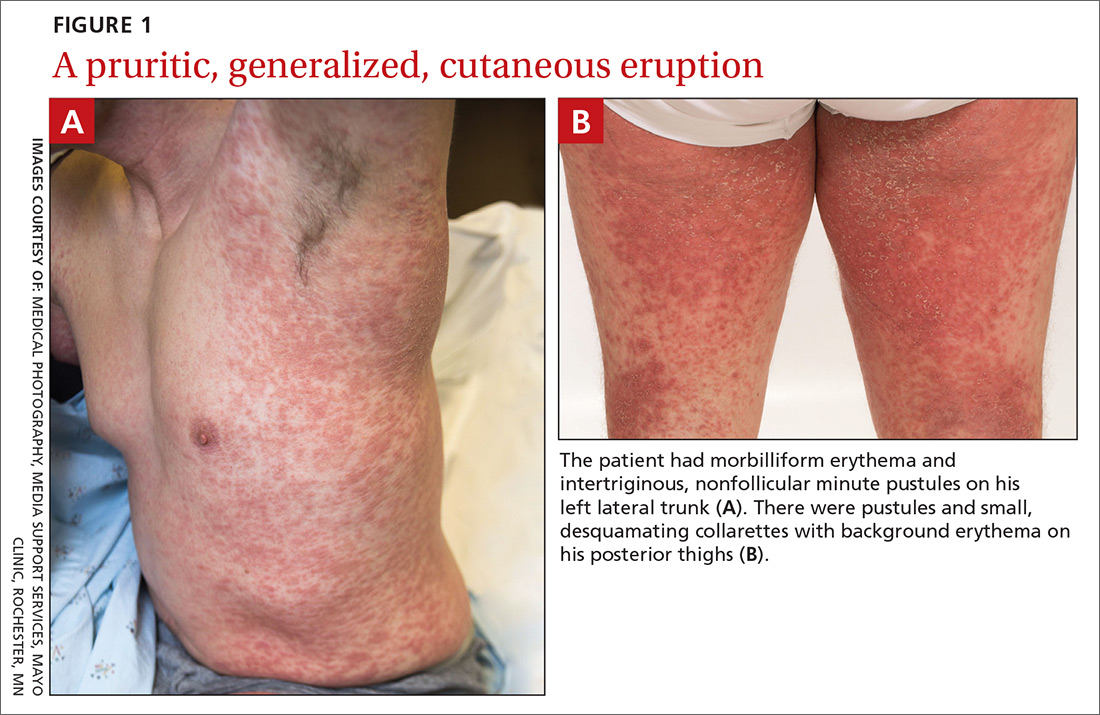

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated.6 A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.3

Our patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared, and only minimal residual erythema was noted (FIGURE 2). The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Wetter, MD, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; [email protected].

1. Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1333-1338.

2. Lee HY, Chou D, Pang SM, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of cases managed in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:507-512.

3. Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996-2013. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:405-414.

4. Bouvresse S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ortonne N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, DRESS, AGEP: do overlap cases exist? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:72.

5. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

6. Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

7. Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1214.

8. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1-e9.

9. Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-e14.

10. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-96.

11. Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S-30S.

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids

Patients who have AGEP, including those with systemic involvement, generally improve after the offending drug is discontinued and treatment with topical corticosteroids is initiated.6 A brief course of systemic corticosteroids can also be considered for patients with severe skin involvement or systemic involvement.3

Our patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid wet dressing treatments twice daily for 2 weeks. At the 2-week follow-up visit, the rash had completely cleared, and only minimal residual erythema was noted (FIGURE 2). The patient was instructed to avoid azithromycin.

CORRESPONDENCE

David A. Wetter, MD, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; [email protected].

A 38-year-old man sought care in the emergency department for an acute, pruritic, generalized cutaneous eruption that manifested in the intertriginous areas of the inner thighs, antecubital fossae, and axilla (FIGURE 1A). He reported associated chills, a 15-pound weight gain, and swelling of his inner thighs. Two weeks before presentation, he had received azithromycin for an upper respiratory tract infection. He was unsure if the rash developed prior to or after taking the medication. He was not taking any other medications and had no history of skin conditions.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and had bilateral thigh edema. Skin examination revealed background erythema with morbilliform papules, plaques, and patches on the bilateral flanks, back, buttocks, arms, legs, and central neck. Pinpoint pustules were present in the intertriginous sites and on the low back and buttocks. The laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (11.0 × 109 cells/L), increased levels of neutrophils and eosinophils, and an elevated C-reactive protein level (12.8 mg/L). The remaining laboratory results were unremarkable. The patient was referred to Dermatology.

An examination by the dermatologist 3 days later revealed small areas of annular desquamation with a few pinpoint pustules, mostly located on the inner thighs and buttocks (FIGURE 1B). Skin biopsies were taken from the anterior hip region. The histopathology revealed subacute dermatitis with mixed dermal inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and eosinophils, and discrete subcorneal spongiform pustules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

The acute rash with minute pustules and associated leukocytosis with neutrophilia and eosinophilia led to an early diagnosis of AGEP, which may have been triggered by azithromycin—the patient’s only recent medication. AGEP is a severe cutaneous eruption that may be associated with systemic involvement. Medications are usually implicated, and patients often seek urgent evaluation.

AGEP typically begins as an acute eruption in the intertriginous sites of the axilla, groin, and neck, but often becomes more generalized.1,2 The diagnosis is strongly suggested by the condition’s key features: fever (97% of cases) and leukocytosis (87%) with neutrophilia (91%) and eosinophilia (30%); leukocytosis peaks 4 days after pustulosis occurs and lasts for about 12 days.1 Although common, fever is not always documented in patients with AGEP. 3 (Our patient was a case in point.) While not a key characteristic of AGEP, our patient’s weight gain was likely explained by the severe edema secondary to his inflammatory skin eruption.

Medications are implicated, but pathophysiology is unknown

In approximately 90% of AGEP cases, medications such as antibiotics and calcium channel blockers are implicated; however, the lack of such an association does not preclude the diagnosis.1,4 In cases of drug reactions, the eruption typically develops 1 to 2 days after a medication is begun, and the pustules typically resolve in fewer than 15 days.5 In 17% of patients, systemic involvement can occur and can include the liver, kidneys, bone marrow, and lungs.6 A physical exam, review of systems, and a laboratory evaluation can help rule out systemic involvement and guide additional testing.

AGEP has an incidence of 1 to 5 cases per million people per year, affecting women slightly more frequently than men.7 While the pathophysiology is not well understood, AGEP and its differential diagnoses are categorized as T cell-related inflammatory responses.4,7

Distinguishing AGEP from some look-alikes

There are at least 4 severe cutaneous eruptions that might be confused with AGEP, all of which may be associated with fever. They include: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS); toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN); and pustular psoriasis.8-10 The clinical features that may help differentiate these conditions from AGEP include timeline, mucocutaneous features, organ system involvement, and histopathologic findings.4,8

DRESS occurs 2 to 6 weeks after drug exposure, rather than a few days, as is seen with AGEP. It often involves morbilliform erythema and facial edema with substantial eosinophilia and possible nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis.9 Unlike AGEP, DRESS does not have a predilection for intertriginous anatomic locations.

SJS and TEN occur 1 to 3 weeks after drug exposure. These conditions manifest with the development of bullae, atypical targetoid lesions, painful dusky erythema, epidermal necrosis, and mucosal involvement at multiple sites. Tubular nephritis, tracheobronchial necrosis, and multisystem organ failure can occur, with reported mortality rates of 5% to 35%.8,11

Pustular psoriasis is frequently confused with AGEP. However, AGEP usually develops fewer than 2 days after drug exposure, with pustules that begin in intertriginous sites, and there is associated neutrophilia and possible organ involvement.1,8 Patients who have AGEP typically do not have a history of psoriasis, while patients with pustular psoriasis often do.7 A history of drug reaction is uncommon with pustular psoriasis (although rapid tapering of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis can trigger the development of pustular psoriasis), whereas a previous history of drug reaction is common in AGEP.3,7

Discontinue medication, treat with corticosteroids