User login

Swelling on lip

The FP recognized this as a venous lake—a benign, dilated vascular channel that is most commonly found on the lip.

Venous lakes are dark blue to pink, slightly raised, and less than a centimeter in size. The lesions empty with firm compression. They may bleed with trauma but have no malignant potential. Venous lakes may start spontaneously or after trauma to the lip.

In this case, the patient was given the choice of doing nothing, or having cryotherapy. She chose cryotherapy and the physician used a closed probe on a Cryogun to get some compression while the freeze was applied. The venous lake disappeared over the following 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Acquired vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:861-864.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP recognized this as a venous lake—a benign, dilated vascular channel that is most commonly found on the lip.

Venous lakes are dark blue to pink, slightly raised, and less than a centimeter in size. The lesions empty with firm compression. They may bleed with trauma but have no malignant potential. Venous lakes may start spontaneously or after trauma to the lip.

In this case, the patient was given the choice of doing nothing, or having cryotherapy. She chose cryotherapy and the physician used a closed probe on a Cryogun to get some compression while the freeze was applied. The venous lake disappeared over the following 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Acquired vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:861-864.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP recognized this as a venous lake—a benign, dilated vascular channel that is most commonly found on the lip.

Venous lakes are dark blue to pink, slightly raised, and less than a centimeter in size. The lesions empty with firm compression. They may bleed with trauma but have no malignant potential. Venous lakes may start spontaneously or after trauma to the lip.

In this case, the patient was given the choice of doing nothing, or having cryotherapy. She chose cryotherapy and the physician used a closed probe on a Cryogun to get some compression while the freeze was applied. The venous lake disappeared over the following 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Acquired vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:861-864.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Lesions on legs

|

|

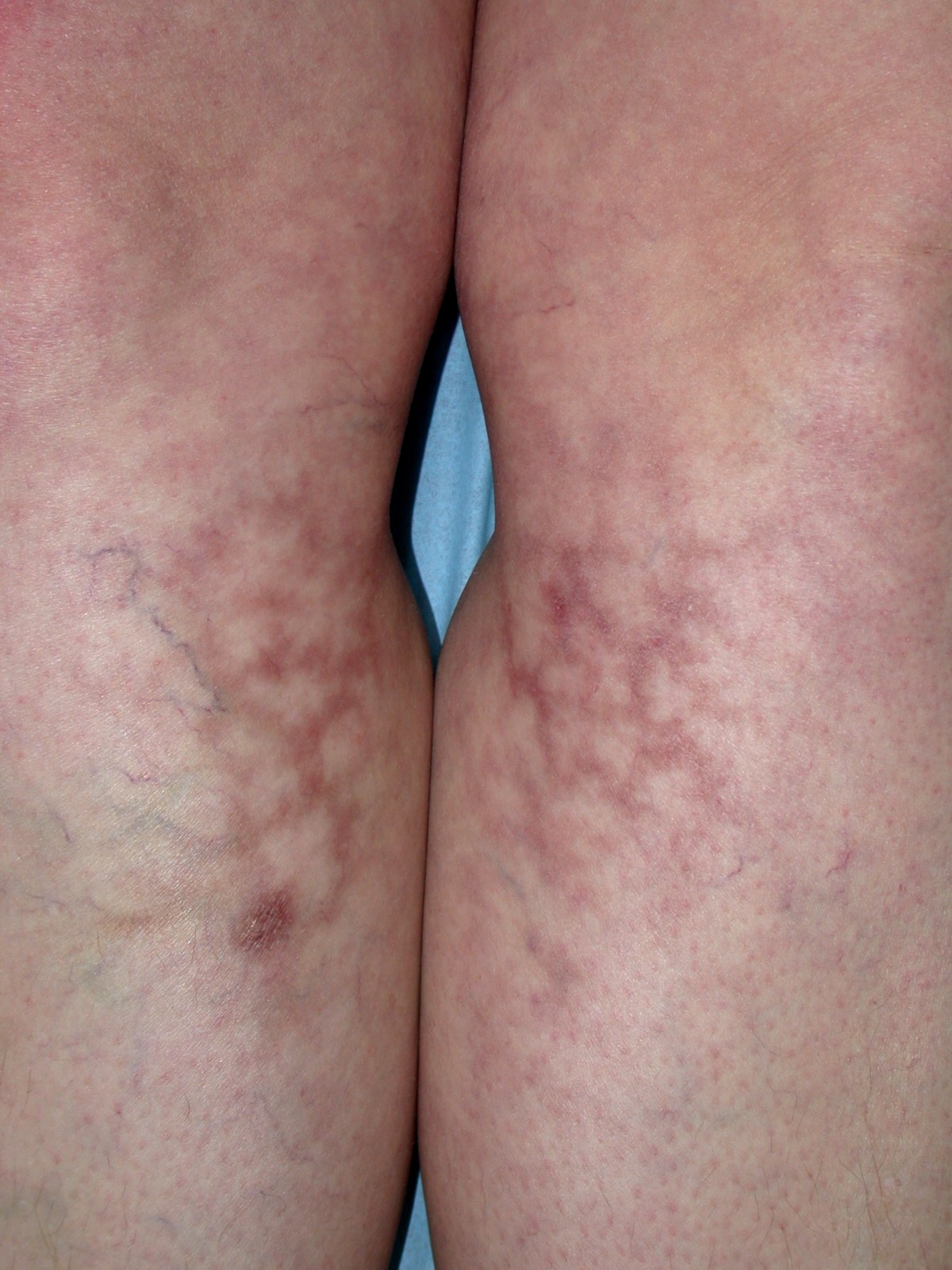

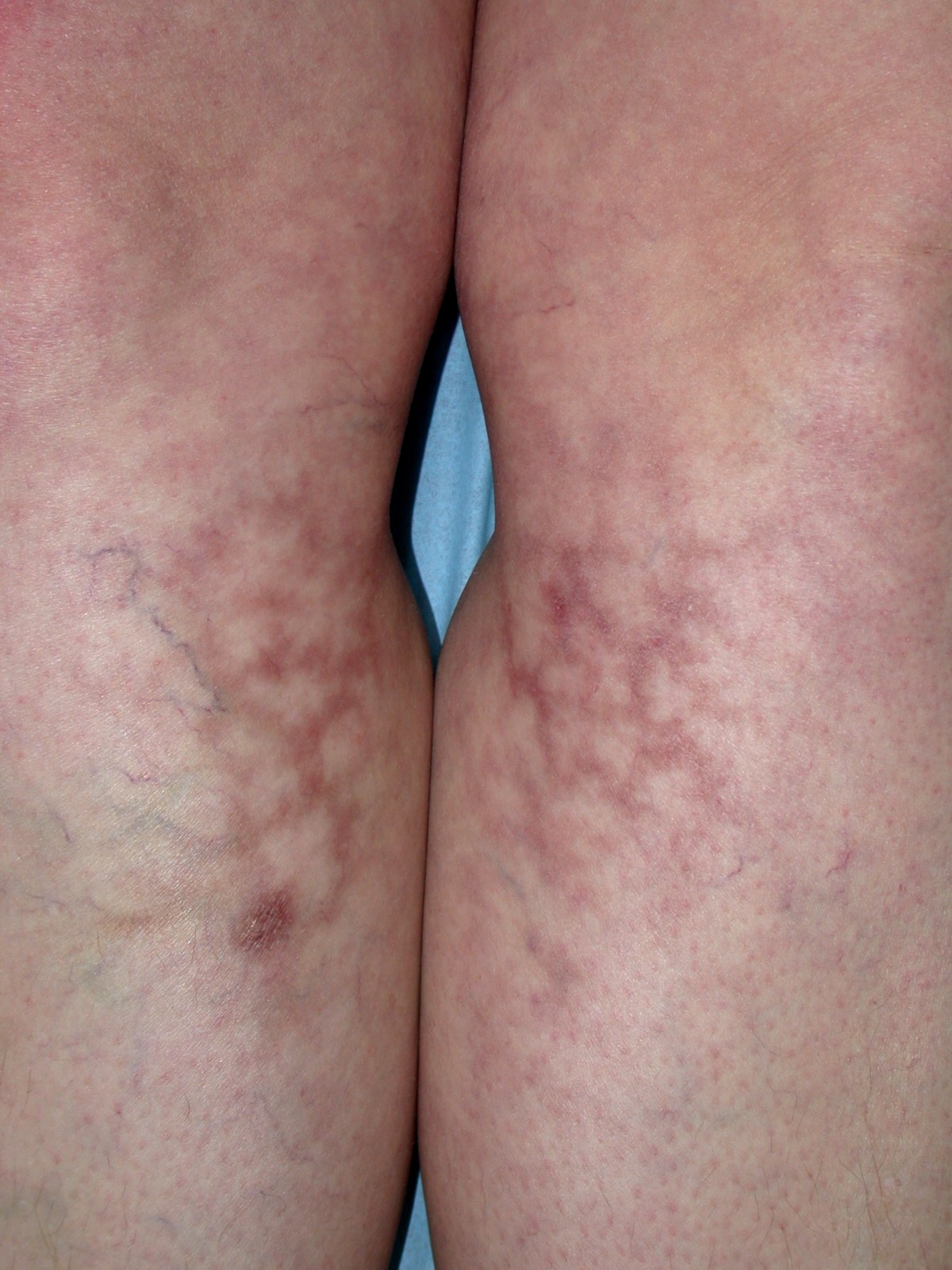

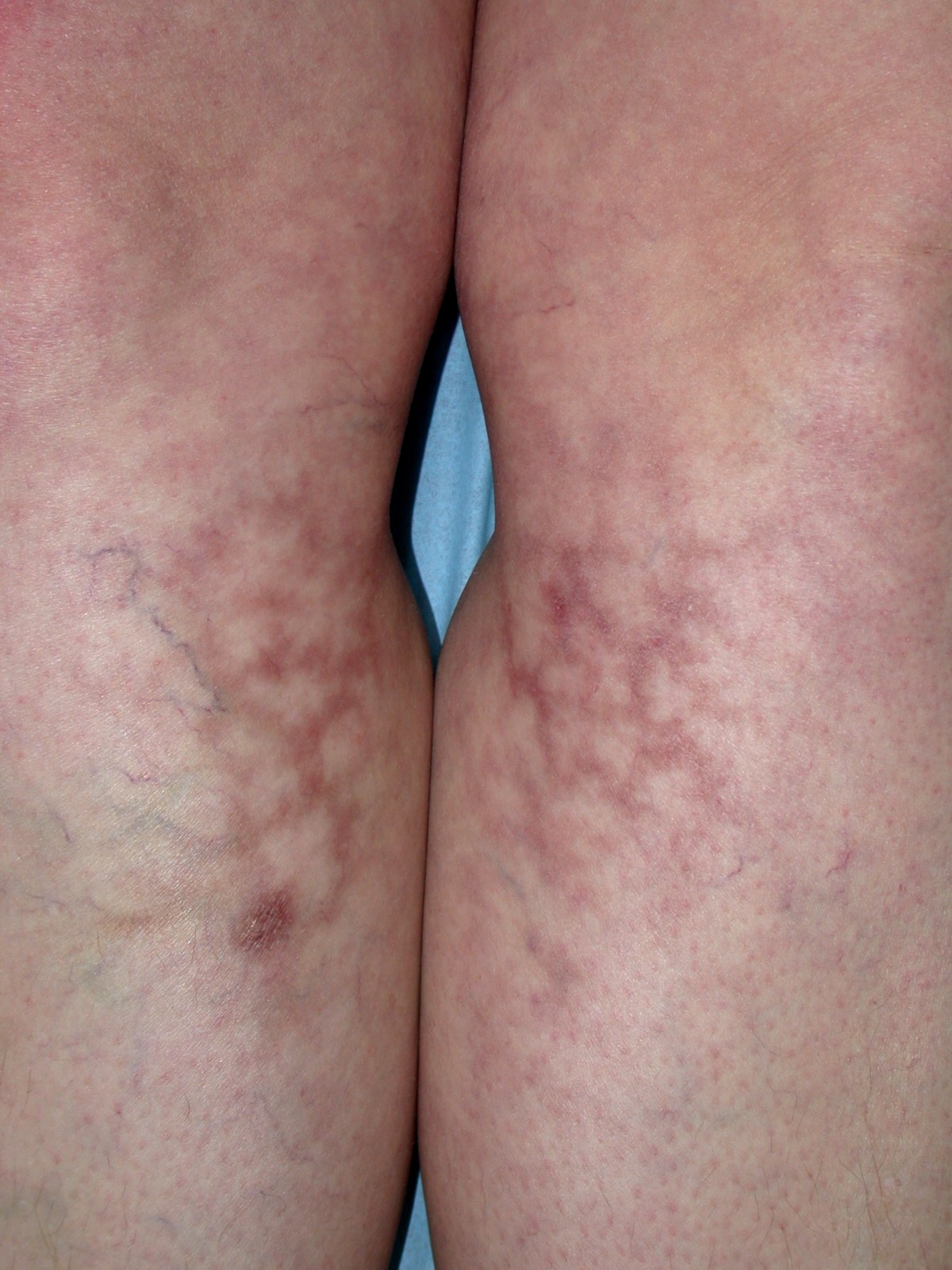

The physician recognized the diagnosis as erythema ab igne (redness from fire) and deemed a biopsy unnecessary. Erythema ab igne is a relatively rare condition seen more commonly in women. The skin findings (FIGURES 1 and 2) form as a result of multiple exposures to an intense source of heat.

Development of the lesions has been linked to the use of hot water bottles, exposure to car heaters and furniture with internal heaters, the use of laptop computers for long periods of time, and extensive exposure to ovens while working as a cook or chef. Ultrasound physiotherapy has also been reported as a cause of erythema ab igne.

Some patients have mild pruritus or a burning sensation, but the majority of patients are asymptomatic. Skin lesions—which may take as long as a month after exposure to show up—start as a reddish brown mottled rash and are followed by skin atrophy. Telangiectasias with diffuse hyperpigmentation and subepidermal bullae may also develop.

The first goal of treatment is to identify the source of heat radiation, so as to avoid further exposure. For mild lesions, no intervention is needed after the heat source is removed; the probability of full resolution is good. Topical retinoids or hydroquinone can be used to treat the abnormal skin pigmentation.

In this case, the patient chose to stop using the hot water bottle and let her skin heal over time. Over the course of 4 months, her skin lesions started to clear with no further intervention.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Amor Khachemoune, MD. This case was adapted from: Khachemoune A, Sarabi K. Erythema ab igne. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:858-860.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

The physician recognized the diagnosis as erythema ab igne (redness from fire) and deemed a biopsy unnecessary. Erythema ab igne is a relatively rare condition seen more commonly in women. The skin findings (FIGURES 1 and 2) form as a result of multiple exposures to an intense source of heat.

Development of the lesions has been linked to the use of hot water bottles, exposure to car heaters and furniture with internal heaters, the use of laptop computers for long periods of time, and extensive exposure to ovens while working as a cook or chef. Ultrasound physiotherapy has also been reported as a cause of erythema ab igne.

Some patients have mild pruritus or a burning sensation, but the majority of patients are asymptomatic. Skin lesions—which may take as long as a month after exposure to show up—start as a reddish brown mottled rash and are followed by skin atrophy. Telangiectasias with diffuse hyperpigmentation and subepidermal bullae may also develop.

The first goal of treatment is to identify the source of heat radiation, so as to avoid further exposure. For mild lesions, no intervention is needed after the heat source is removed; the probability of full resolution is good. Topical retinoids or hydroquinone can be used to treat the abnormal skin pigmentation.

In this case, the patient chose to stop using the hot water bottle and let her skin heal over time. Over the course of 4 months, her skin lesions started to clear with no further intervention.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Amor Khachemoune, MD. This case was adapted from: Khachemoune A, Sarabi K. Erythema ab igne. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:858-860.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

The physician recognized the diagnosis as erythema ab igne (redness from fire) and deemed a biopsy unnecessary. Erythema ab igne is a relatively rare condition seen more commonly in women. The skin findings (FIGURES 1 and 2) form as a result of multiple exposures to an intense source of heat.

Development of the lesions has been linked to the use of hot water bottles, exposure to car heaters and furniture with internal heaters, the use of laptop computers for long periods of time, and extensive exposure to ovens while working as a cook or chef. Ultrasound physiotherapy has also been reported as a cause of erythema ab igne.

Some patients have mild pruritus or a burning sensation, but the majority of patients are asymptomatic. Skin lesions—which may take as long as a month after exposure to show up—start as a reddish brown mottled rash and are followed by skin atrophy. Telangiectasias with diffuse hyperpigmentation and subepidermal bullae may also develop.

The first goal of treatment is to identify the source of heat radiation, so as to avoid further exposure. For mild lesions, no intervention is needed after the heat source is removed; the probability of full resolution is good. Topical retinoids or hydroquinone can be used to treat the abnormal skin pigmentation.

In this case, the patient chose to stop using the hot water bottle and let her skin heal over time. Over the course of 4 months, her skin lesions started to clear with no further intervention.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Amor Khachemoune, MD. This case was adapted from: Khachemoune A, Sarabi K. Erythema ab igne. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:858-860.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Erythematous patches on the hands

A 49-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for erythematous patches on the dorsal surface of his hands. The patient indicated that these lesions had appeared approximately 2 to 3 years earlier and that they had become increasingly painful when exposed to sunlight. The patient’s mother also recalled multiple sunburns that he’d suffered in the past.

The patient had a mild mental impairment and struggled with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He admitted to washing his hands 10 to 15 times a day, and was previously given a diagnosis of dyshidrosis secondary to excessive hand washing. The patient was treated with moisturizing creams, but his symptoms did not improve.

Examination of the dorsal surface of his hands revealed multiple erythematous patches, blisters, and calluses, as well as ulcerations on the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (FIGURE 1). There were also scarred and linear plaques on the bilateral proximal and distal interphalangeal joints. The patient had no other lesions on his body.

FIGURE 1

Erythematous patches, blisters, calluses, and ulcerations

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythropoietic protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is a metabolic disease that is caused by a deficiency in ferrochelatase enzyme activity.1,2 Ferrochelatase is the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway, which is responsible for the incorporation of iron onto protoporphyrin IX.1 Ferrochelatase activity in patients with EPP is typically 10% to 25% of normal, resulting in an accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in the skin, erythrocytes, liver, and plasma.1,3 There are both autosomal dominant and recessive forms of EPP, and it is the most common porphyria found in children.1,3

A characteristic that distinguishes EPP from other porphyrias is the rapid onset of photosensitivity associated with pruritus and a stinging or burning sensation on the sun-exposed areas of the body—typically, the cheeks, nose, and dorsal surface of the hands.4 These symptoms are commonly followed by edema, erythema, and in more severe cases, petechiae.3,4 With repeated sun exposure, the affected skin may develop a waxy thickening with shallow linear or elliptical scars, making the patient’s skin appear much older than it actually is.3,4 Although blisters, erosions, and crusting are not always present, they can manifest with prolonged sun exposure.1

What you may also see

Hepatobiliary disease is present in about 25% of patients, and may be the only manifestation of the disease.1 The deleterious effects of protoporphyrin are concentration dependent, so a wide variation in the severity of hepatobiliary disease exists. Cholelithiasis and micro-cytic hypochromic anemia are common on the mild end of the spectrum, but life-threatening complications such as hepatic failure have been reported in about 2% to 5% of cases.1,5

When it’s diagnosed. EPP usually manifests by 2 to 5 years of age, but it may not be diagnosed until adulthood.3 Such a delay may occur because of a lack of cutaneous lesions, mild symptoms, or a late onset of symptoms.1

Consider these conditions in the differential

Contact dermatitis. This inflammatory skin condition can occur when a foreign substance irritates the skin (irritant contact dermatitis) or result from a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that’s evoked by reexposure to a substance (allergic contact dermatitis). Acute lesions are typically well defined and confined to the site of exposure. They are characterized by erythema, vesicles or bullae, erosions, and crusts. In chronic cases, the lesions are ill-defined and involve plaques, fissures, scaling, and/or crusts.4,6

Porphyria cutanea tarda. This most common form of porphyria is characterized by increased sensitivity and fragility of the skin.3 (For more information, see “Genetic blood disorders: Questions you need to ask,” J Fam Pract. 2012;61:30-37.) Vesicles and bullae will form after minimal trauma, typically on the dorsal surface of the hands, extensor surfaces of the forearms, and the face. These lesions will eventually form erosions and heal slowly to form atrophic scars. Excessive hair growth on the face, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, scarring alopecia, and scleroderma-like changes with yellowish-white plaques have also been described in porphyria cutanea tarda. Wood’s lamp examination of urine will reveal a coral-red fluorescence.4,7

Dyshidrotic eczema. This disease is characterized by the sudden onset of pruritic, clear vesicles on the fingers, palms, and soles. The vesicles are deep-seated and are typically devoid of surrounding erythema. Each episode will spontaneously regress in 2 to 3 weeks, but this disease can be disabling due to the recurring nature of the outbreaks.4,8

Solar urticaria. Within minutes of sun exposure, erythematous patches with or without wheals will appear. The lesions typically last less than 24 hours, and are most commonly found on the chest and upper arms. Pruritus and a burning sensation frequently accompany flares of solar urticaria, and pain may be present but is not a common symptom. In severe cases, an anaphylactoid reaction can occur, with light-headedness, nausea, bronchospasm, and syncope.4,9

Hydroa vacciniforme. Within hours of sun exposure, erythematous macules will appear. They will progress to papules and vesicles, and may become hemorrhagic. These lesions are typically found on the face, ears, and dorsa of the hands in a symmetric, clustered pattern. Pruritus and a stinging sensation may accompany the lesions, as well as general malaise or fever. Over the course of a few days, the lesions will become necrotic, form a hemorrhagic crust, and heal with ”pox-like” vacciniform scars.4,9

Confirm your suspicions with testing

There should be a high degree of suspicion for EPP when any child or adult presents with photosensitivity.10,11 The absence or delayed onset of visible lesions can make the diagnosis difficult and cause the patient considerable suffering.12

If EPP is suspected, order lab work for confirmation. The most diagnostically useful test is the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level, which will be increased in patients with EPP. These levels can range from several hundred to several thousand μg/100 mL of packed red blood cells (normal= <35 μg/100 mL).3 In addition, elevated levels of protoporphyrin are found in the feces. However, unlike other porphyrias, the level of urine porphyrins is normal (because protoporphyrin IX is water-soluble).1,3

Due to the incidence of hepatobiliary disease in EPP, liver enzymes should be drawn and the proper imaging performed if abnormal values are obtained. Biopsy of the involved skin, with histologic review, will also aid in the diagnosis if other testing is inconclusive.1,4

Treatment: Protection from sun is key

While complete sun exposure avoidance would prevent most sequelae in EPP, this is not always a feasible option. Covering the skin with sun-protective clothing and using sunscreen that contains titanium oxide or zinc oxide are acceptable alternatives to overt avoidance1,3,10,13 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Beta-carotene at doses of 60 to 180 mg/d for adults or 30 to 90 mg/d for children to achieve a serum level of 600 mcg/dL has also been shown to be effective in reducing photosensitivity in some cases 1,2,5 (SOR: B). Cysteine, antihistamines, phototherapy, pyroxidine, and vitamin C have also been used to treat EPP, but have demonstrated limited efficacy1,3,10 (SOR: B).

Hepatobiliary complications. Treating hepatobiliary complications is dependent upon the degree of dysfunction. Cholestyramine can be used to increase the fecal excretion of protoporphyrins in liver dysfunction1,3,10 (SOR: A). In severe liver dysfunction, blood transfusions can be utilized until a liver transplant can be performed1,3,10 (SOR: A). Liver transplantation, however, does not correct the metabolic error, and damage to the transplanted liver can occur.1

Sun block and supplements for our patient

After discussing the risks and benefits of treatment, our patient elected to use an over-the-counter zinc oxide sun block, as well as begin beta-carotene supplementation at 60 mg/d. We slowly increased the beta-carotene to therapeutic levels, and reevaluated for efficacy. To treat the lesions on his hands, we started the patient on tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.1% ointment once daily (to avoid using a topical steroid due to his skin fragility) and a skin protectant/moisturizer (Theraseal) 2 to 3 times daily to reduce irritation.

After treatment and minimal sun exposure for several months, our patient saw a dramatic improvement in his disease, with no blistering or ulcerations noted (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

A dramatic improvement

After minimizing his exposure to the sun, using tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and a skin moisturizer, and taking a beta-carotene supplement, the appearance of our patient’s hands improved. His hands were less erythematous and there were no ulcerations. Callus formation persisted.

CORRESPONDENCE David A. Kasper, DO, MBA, Skin Cancer Institute, 1003 South Broad Street, Lansdale, PA 19006; [email protected]

1. Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

2. Wahlin S, Floderus Y, Stål P, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in Sweden: demographic, clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics. J Intern Med. 2011;269:278-288.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Errors in metabolism. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:511–515.

4. Murphy GM. Porphyria. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2003:679–686.

5. Herrero C, To-Figueras J, Badenas C, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic study of 11 patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria including one with homozygous disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1125-1129.

6. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

7. Yeh SW, Ahmed B, Sami N, et al. Blistering disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:214-223.

8. Kedrowski DA, Warshaw EM. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:17-25.

9. Gambichler T, Al-Muhammadi R, Boms S. Immunologically mediated photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:169-180.

10. Murphy GM. Diagnosis and management of the erythropoietic porphyrias. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:57-64.

11. Lecluse AL, Kuck-Koot VC, van Weelden H, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria without skin symptoms–you do not always see what they feel. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:703-706.

12. Holme SA, Anstey AV, Finlay AY, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in the U.K.: clinical features and effect on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:574-581.

13. Sies C, Florkowski C, George P, et al. Clinical indications for the investigation of porphyria: case examples and evolving laboratory approaches to its diagnosis in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2005;118:U1658.-

A 49-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for erythematous patches on the dorsal surface of his hands. The patient indicated that these lesions had appeared approximately 2 to 3 years earlier and that they had become increasingly painful when exposed to sunlight. The patient’s mother also recalled multiple sunburns that he’d suffered in the past.

The patient had a mild mental impairment and struggled with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He admitted to washing his hands 10 to 15 times a day, and was previously given a diagnosis of dyshidrosis secondary to excessive hand washing. The patient was treated with moisturizing creams, but his symptoms did not improve.

Examination of the dorsal surface of his hands revealed multiple erythematous patches, blisters, and calluses, as well as ulcerations on the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (FIGURE 1). There were also scarred and linear plaques on the bilateral proximal and distal interphalangeal joints. The patient had no other lesions on his body.

FIGURE 1

Erythematous patches, blisters, calluses, and ulcerations

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythropoietic protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is a metabolic disease that is caused by a deficiency in ferrochelatase enzyme activity.1,2 Ferrochelatase is the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway, which is responsible for the incorporation of iron onto protoporphyrin IX.1 Ferrochelatase activity in patients with EPP is typically 10% to 25% of normal, resulting in an accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in the skin, erythrocytes, liver, and plasma.1,3 There are both autosomal dominant and recessive forms of EPP, and it is the most common porphyria found in children.1,3

A characteristic that distinguishes EPP from other porphyrias is the rapid onset of photosensitivity associated with pruritus and a stinging or burning sensation on the sun-exposed areas of the body—typically, the cheeks, nose, and dorsal surface of the hands.4 These symptoms are commonly followed by edema, erythema, and in more severe cases, petechiae.3,4 With repeated sun exposure, the affected skin may develop a waxy thickening with shallow linear or elliptical scars, making the patient’s skin appear much older than it actually is.3,4 Although blisters, erosions, and crusting are not always present, they can manifest with prolonged sun exposure.1

What you may also see

Hepatobiliary disease is present in about 25% of patients, and may be the only manifestation of the disease.1 The deleterious effects of protoporphyrin are concentration dependent, so a wide variation in the severity of hepatobiliary disease exists. Cholelithiasis and micro-cytic hypochromic anemia are common on the mild end of the spectrum, but life-threatening complications such as hepatic failure have been reported in about 2% to 5% of cases.1,5

When it’s diagnosed. EPP usually manifests by 2 to 5 years of age, but it may not be diagnosed until adulthood.3 Such a delay may occur because of a lack of cutaneous lesions, mild symptoms, or a late onset of symptoms.1

Consider these conditions in the differential

Contact dermatitis. This inflammatory skin condition can occur when a foreign substance irritates the skin (irritant contact dermatitis) or result from a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that’s evoked by reexposure to a substance (allergic contact dermatitis). Acute lesions are typically well defined and confined to the site of exposure. They are characterized by erythema, vesicles or bullae, erosions, and crusts. In chronic cases, the lesions are ill-defined and involve plaques, fissures, scaling, and/or crusts.4,6

Porphyria cutanea tarda. This most common form of porphyria is characterized by increased sensitivity and fragility of the skin.3 (For more information, see “Genetic blood disorders: Questions you need to ask,” J Fam Pract. 2012;61:30-37.) Vesicles and bullae will form after minimal trauma, typically on the dorsal surface of the hands, extensor surfaces of the forearms, and the face. These lesions will eventually form erosions and heal slowly to form atrophic scars. Excessive hair growth on the face, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, scarring alopecia, and scleroderma-like changes with yellowish-white plaques have also been described in porphyria cutanea tarda. Wood’s lamp examination of urine will reveal a coral-red fluorescence.4,7

Dyshidrotic eczema. This disease is characterized by the sudden onset of pruritic, clear vesicles on the fingers, palms, and soles. The vesicles are deep-seated and are typically devoid of surrounding erythema. Each episode will spontaneously regress in 2 to 3 weeks, but this disease can be disabling due to the recurring nature of the outbreaks.4,8

Solar urticaria. Within minutes of sun exposure, erythematous patches with or without wheals will appear. The lesions typically last less than 24 hours, and are most commonly found on the chest and upper arms. Pruritus and a burning sensation frequently accompany flares of solar urticaria, and pain may be present but is not a common symptom. In severe cases, an anaphylactoid reaction can occur, with light-headedness, nausea, bronchospasm, and syncope.4,9

Hydroa vacciniforme. Within hours of sun exposure, erythematous macules will appear. They will progress to papules and vesicles, and may become hemorrhagic. These lesions are typically found on the face, ears, and dorsa of the hands in a symmetric, clustered pattern. Pruritus and a stinging sensation may accompany the lesions, as well as general malaise or fever. Over the course of a few days, the lesions will become necrotic, form a hemorrhagic crust, and heal with ”pox-like” vacciniform scars.4,9

Confirm your suspicions with testing

There should be a high degree of suspicion for EPP when any child or adult presents with photosensitivity.10,11 The absence or delayed onset of visible lesions can make the diagnosis difficult and cause the patient considerable suffering.12

If EPP is suspected, order lab work for confirmation. The most diagnostically useful test is the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level, which will be increased in patients with EPP. These levels can range from several hundred to several thousand μg/100 mL of packed red blood cells (normal= <35 μg/100 mL).3 In addition, elevated levels of protoporphyrin are found in the feces. However, unlike other porphyrias, the level of urine porphyrins is normal (because protoporphyrin IX is water-soluble).1,3

Due to the incidence of hepatobiliary disease in EPP, liver enzymes should be drawn and the proper imaging performed if abnormal values are obtained. Biopsy of the involved skin, with histologic review, will also aid in the diagnosis if other testing is inconclusive.1,4

Treatment: Protection from sun is key

While complete sun exposure avoidance would prevent most sequelae in EPP, this is not always a feasible option. Covering the skin with sun-protective clothing and using sunscreen that contains titanium oxide or zinc oxide are acceptable alternatives to overt avoidance1,3,10,13 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Beta-carotene at doses of 60 to 180 mg/d for adults or 30 to 90 mg/d for children to achieve a serum level of 600 mcg/dL has also been shown to be effective in reducing photosensitivity in some cases 1,2,5 (SOR: B). Cysteine, antihistamines, phototherapy, pyroxidine, and vitamin C have also been used to treat EPP, but have demonstrated limited efficacy1,3,10 (SOR: B).

Hepatobiliary complications. Treating hepatobiliary complications is dependent upon the degree of dysfunction. Cholestyramine can be used to increase the fecal excretion of protoporphyrins in liver dysfunction1,3,10 (SOR: A). In severe liver dysfunction, blood transfusions can be utilized until a liver transplant can be performed1,3,10 (SOR: A). Liver transplantation, however, does not correct the metabolic error, and damage to the transplanted liver can occur.1

Sun block and supplements for our patient

After discussing the risks and benefits of treatment, our patient elected to use an over-the-counter zinc oxide sun block, as well as begin beta-carotene supplementation at 60 mg/d. We slowly increased the beta-carotene to therapeutic levels, and reevaluated for efficacy. To treat the lesions on his hands, we started the patient on tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.1% ointment once daily (to avoid using a topical steroid due to his skin fragility) and a skin protectant/moisturizer (Theraseal) 2 to 3 times daily to reduce irritation.

After treatment and minimal sun exposure for several months, our patient saw a dramatic improvement in his disease, with no blistering or ulcerations noted (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

A dramatic improvement

After minimizing his exposure to the sun, using tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and a skin moisturizer, and taking a beta-carotene supplement, the appearance of our patient’s hands improved. His hands were less erythematous and there were no ulcerations. Callus formation persisted.

CORRESPONDENCE David A. Kasper, DO, MBA, Skin Cancer Institute, 1003 South Broad Street, Lansdale, PA 19006; [email protected]

A 49-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for erythematous patches on the dorsal surface of his hands. The patient indicated that these lesions had appeared approximately 2 to 3 years earlier and that they had become increasingly painful when exposed to sunlight. The patient’s mother also recalled multiple sunburns that he’d suffered in the past.

The patient had a mild mental impairment and struggled with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He admitted to washing his hands 10 to 15 times a day, and was previously given a diagnosis of dyshidrosis secondary to excessive hand washing. The patient was treated with moisturizing creams, but his symptoms did not improve.

Examination of the dorsal surface of his hands revealed multiple erythematous patches, blisters, and calluses, as well as ulcerations on the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (FIGURE 1). There were also scarred and linear plaques on the bilateral proximal and distal interphalangeal joints. The patient had no other lesions on his body.

FIGURE 1

Erythematous patches, blisters, calluses, and ulcerations

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythropoietic protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is a metabolic disease that is caused by a deficiency in ferrochelatase enzyme activity.1,2 Ferrochelatase is the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway, which is responsible for the incorporation of iron onto protoporphyrin IX.1 Ferrochelatase activity in patients with EPP is typically 10% to 25% of normal, resulting in an accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in the skin, erythrocytes, liver, and plasma.1,3 There are both autosomal dominant and recessive forms of EPP, and it is the most common porphyria found in children.1,3

A characteristic that distinguishes EPP from other porphyrias is the rapid onset of photosensitivity associated with pruritus and a stinging or burning sensation on the sun-exposed areas of the body—typically, the cheeks, nose, and dorsal surface of the hands.4 These symptoms are commonly followed by edema, erythema, and in more severe cases, petechiae.3,4 With repeated sun exposure, the affected skin may develop a waxy thickening with shallow linear or elliptical scars, making the patient’s skin appear much older than it actually is.3,4 Although blisters, erosions, and crusting are not always present, they can manifest with prolonged sun exposure.1

What you may also see

Hepatobiliary disease is present in about 25% of patients, and may be the only manifestation of the disease.1 The deleterious effects of protoporphyrin are concentration dependent, so a wide variation in the severity of hepatobiliary disease exists. Cholelithiasis and micro-cytic hypochromic anemia are common on the mild end of the spectrum, but life-threatening complications such as hepatic failure have been reported in about 2% to 5% of cases.1,5

When it’s diagnosed. EPP usually manifests by 2 to 5 years of age, but it may not be diagnosed until adulthood.3 Such a delay may occur because of a lack of cutaneous lesions, mild symptoms, or a late onset of symptoms.1

Consider these conditions in the differential

Contact dermatitis. This inflammatory skin condition can occur when a foreign substance irritates the skin (irritant contact dermatitis) or result from a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that’s evoked by reexposure to a substance (allergic contact dermatitis). Acute lesions are typically well defined and confined to the site of exposure. They are characterized by erythema, vesicles or bullae, erosions, and crusts. In chronic cases, the lesions are ill-defined and involve plaques, fissures, scaling, and/or crusts.4,6

Porphyria cutanea tarda. This most common form of porphyria is characterized by increased sensitivity and fragility of the skin.3 (For more information, see “Genetic blood disorders: Questions you need to ask,” J Fam Pract. 2012;61:30-37.) Vesicles and bullae will form after minimal trauma, typically on the dorsal surface of the hands, extensor surfaces of the forearms, and the face. These lesions will eventually form erosions and heal slowly to form atrophic scars. Excessive hair growth on the face, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, scarring alopecia, and scleroderma-like changes with yellowish-white plaques have also been described in porphyria cutanea tarda. Wood’s lamp examination of urine will reveal a coral-red fluorescence.4,7

Dyshidrotic eczema. This disease is characterized by the sudden onset of pruritic, clear vesicles on the fingers, palms, and soles. The vesicles are deep-seated and are typically devoid of surrounding erythema. Each episode will spontaneously regress in 2 to 3 weeks, but this disease can be disabling due to the recurring nature of the outbreaks.4,8

Solar urticaria. Within minutes of sun exposure, erythematous patches with or without wheals will appear. The lesions typically last less than 24 hours, and are most commonly found on the chest and upper arms. Pruritus and a burning sensation frequently accompany flares of solar urticaria, and pain may be present but is not a common symptom. In severe cases, an anaphylactoid reaction can occur, with light-headedness, nausea, bronchospasm, and syncope.4,9

Hydroa vacciniforme. Within hours of sun exposure, erythematous macules will appear. They will progress to papules and vesicles, and may become hemorrhagic. These lesions are typically found on the face, ears, and dorsa of the hands in a symmetric, clustered pattern. Pruritus and a stinging sensation may accompany the lesions, as well as general malaise or fever. Over the course of a few days, the lesions will become necrotic, form a hemorrhagic crust, and heal with ”pox-like” vacciniform scars.4,9

Confirm your suspicions with testing

There should be a high degree of suspicion for EPP when any child or adult presents with photosensitivity.10,11 The absence or delayed onset of visible lesions can make the diagnosis difficult and cause the patient considerable suffering.12

If EPP is suspected, order lab work for confirmation. The most diagnostically useful test is the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level, which will be increased in patients with EPP. These levels can range from several hundred to several thousand μg/100 mL of packed red blood cells (normal= <35 μg/100 mL).3 In addition, elevated levels of protoporphyrin are found in the feces. However, unlike other porphyrias, the level of urine porphyrins is normal (because protoporphyrin IX is water-soluble).1,3

Due to the incidence of hepatobiliary disease in EPP, liver enzymes should be drawn and the proper imaging performed if abnormal values are obtained. Biopsy of the involved skin, with histologic review, will also aid in the diagnosis if other testing is inconclusive.1,4

Treatment: Protection from sun is key

While complete sun exposure avoidance would prevent most sequelae in EPP, this is not always a feasible option. Covering the skin with sun-protective clothing and using sunscreen that contains titanium oxide or zinc oxide are acceptable alternatives to overt avoidance1,3,10,13 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Beta-carotene at doses of 60 to 180 mg/d for adults or 30 to 90 mg/d for children to achieve a serum level of 600 mcg/dL has also been shown to be effective in reducing photosensitivity in some cases 1,2,5 (SOR: B). Cysteine, antihistamines, phototherapy, pyroxidine, and vitamin C have also been used to treat EPP, but have demonstrated limited efficacy1,3,10 (SOR: B).

Hepatobiliary complications. Treating hepatobiliary complications is dependent upon the degree of dysfunction. Cholestyramine can be used to increase the fecal excretion of protoporphyrins in liver dysfunction1,3,10 (SOR: A). In severe liver dysfunction, blood transfusions can be utilized until a liver transplant can be performed1,3,10 (SOR: A). Liver transplantation, however, does not correct the metabolic error, and damage to the transplanted liver can occur.1

Sun block and supplements for our patient

After discussing the risks and benefits of treatment, our patient elected to use an over-the-counter zinc oxide sun block, as well as begin beta-carotene supplementation at 60 mg/d. We slowly increased the beta-carotene to therapeutic levels, and reevaluated for efficacy. To treat the lesions on his hands, we started the patient on tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.1% ointment once daily (to avoid using a topical steroid due to his skin fragility) and a skin protectant/moisturizer (Theraseal) 2 to 3 times daily to reduce irritation.

After treatment and minimal sun exposure for several months, our patient saw a dramatic improvement in his disease, with no blistering or ulcerations noted (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

A dramatic improvement

After minimizing his exposure to the sun, using tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and a skin moisturizer, and taking a beta-carotene supplement, the appearance of our patient’s hands improved. His hands were less erythematous and there were no ulcerations. Callus formation persisted.

CORRESPONDENCE David A. Kasper, DO, MBA, Skin Cancer Institute, 1003 South Broad Street, Lansdale, PA 19006; [email protected]

1. Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

2. Wahlin S, Floderus Y, Stål P, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in Sweden: demographic, clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics. J Intern Med. 2011;269:278-288.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Errors in metabolism. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:511–515.

4. Murphy GM. Porphyria. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2003:679–686.

5. Herrero C, To-Figueras J, Badenas C, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic study of 11 patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria including one with homozygous disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1125-1129.

6. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

7. Yeh SW, Ahmed B, Sami N, et al. Blistering disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:214-223.

8. Kedrowski DA, Warshaw EM. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:17-25.

9. Gambichler T, Al-Muhammadi R, Boms S. Immunologically mediated photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:169-180.

10. Murphy GM. Diagnosis and management of the erythropoietic porphyrias. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:57-64.

11. Lecluse AL, Kuck-Koot VC, van Weelden H, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria without skin symptoms–you do not always see what they feel. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:703-706.

12. Holme SA, Anstey AV, Finlay AY, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in the U.K.: clinical features and effect on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:574-581.

13. Sies C, Florkowski C, George P, et al. Clinical indications for the investigation of porphyria: case examples and evolving laboratory approaches to its diagnosis in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2005;118:U1658.-

1. Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

2. Wahlin S, Floderus Y, Stål P, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in Sweden: demographic, clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics. J Intern Med. 2011;269:278-288.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Errors in metabolism. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:511–515.

4. Murphy GM. Porphyria. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2003:679–686.

5. Herrero C, To-Figueras J, Badenas C, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic study of 11 patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria including one with homozygous disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1125-1129.

6. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

7. Yeh SW, Ahmed B, Sami N, et al. Blistering disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:214-223.

8. Kedrowski DA, Warshaw EM. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:17-25.

9. Gambichler T, Al-Muhammadi R, Boms S. Immunologically mediated photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:169-180.

10. Murphy GM. Diagnosis and management of the erythropoietic porphyrias. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:57-64.

11. Lecluse AL, Kuck-Koot VC, van Weelden H, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria without skin symptoms–you do not always see what they feel. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:703-706.

12. Holme SA, Anstey AV, Finlay AY, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in the U.K.: clinical features and effect on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:574-581.

13. Sies C, Florkowski C, George P, et al. Clinical indications for the investigation of porphyria: case examples and evolving laboratory approaches to its diagnosis in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2005;118:U1658.-

Raised, pruritic lesion

The family physician (FP) diagnosed phytophotodermatitis caused by lime juice and sun exposure on the beach. Note the handprint of her fiance who had been squeezing limes into their tropical drinks. This contact occurred when they posed for a photograph. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is present along with the erythema

Phytophotodermatitis is a phototoxic reaction to psoralens, which are plant compounds found in limes, celery, figs, and certain drugs. They can cause dramatic inflammation and bullae where the psoralen comes into contact with the skin. Accompanying hyperpigmentation is a good clue to a phytophotodermatitis reaction.

It helps to ask the patient if she, or he, has had any contact with limes, celery, or figs. Squeezing lime juice into drinks is a particularly common cause of this reaction.

Acute episodes of photodermatitis respond rapidly to topical and/or oral corticosteroids. Topical steroids should provide symptomatic relief and decrease the inflammation. For more severe reactions, a course of prednisone daily for 5 to 7 days may be used.

In this case, the FP prescribed triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied to the affected areas twice a day. The patient was advised to use sunscreen to prevent further hyperpigmentation. Although most lesions fade with time, a topical bleaching agent such as hydroquinone may be prescribed to reduce hyperpigmentation

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Andrea Darby-Stewart, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Wenner C. Photodermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:853-857.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician (FP) diagnosed phytophotodermatitis caused by lime juice and sun exposure on the beach. Note the handprint of her fiance who had been squeezing limes into their tropical drinks. This contact occurred when they posed for a photograph. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is present along with the erythema

Phytophotodermatitis is a phototoxic reaction to psoralens, which are plant compounds found in limes, celery, figs, and certain drugs. They can cause dramatic inflammation and bullae where the psoralen comes into contact with the skin. Accompanying hyperpigmentation is a good clue to a phytophotodermatitis reaction.

It helps to ask the patient if she, or he, has had any contact with limes, celery, or figs. Squeezing lime juice into drinks is a particularly common cause of this reaction.

Acute episodes of photodermatitis respond rapidly to topical and/or oral corticosteroids. Topical steroids should provide symptomatic relief and decrease the inflammation. For more severe reactions, a course of prednisone daily for 5 to 7 days may be used.

In this case, the FP prescribed triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied to the affected areas twice a day. The patient was advised to use sunscreen to prevent further hyperpigmentation. Although most lesions fade with time, a topical bleaching agent such as hydroquinone may be prescribed to reduce hyperpigmentation

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Andrea Darby-Stewart, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Wenner C. Photodermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:853-857.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician (FP) diagnosed phytophotodermatitis caused by lime juice and sun exposure on the beach. Note the handprint of her fiance who had been squeezing limes into their tropical drinks. This contact occurred when they posed for a photograph. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is present along with the erythema

Phytophotodermatitis is a phototoxic reaction to psoralens, which are plant compounds found in limes, celery, figs, and certain drugs. They can cause dramatic inflammation and bullae where the psoralen comes into contact with the skin. Accompanying hyperpigmentation is a good clue to a phytophotodermatitis reaction.

It helps to ask the patient if she, or he, has had any contact with limes, celery, or figs. Squeezing lime juice into drinks is a particularly common cause of this reaction.

Acute episodes of photodermatitis respond rapidly to topical and/or oral corticosteroids. Topical steroids should provide symptomatic relief and decrease the inflammation. For more severe reactions, a course of prednisone daily for 5 to 7 days may be used.

In this case, the FP prescribed triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied to the affected areas twice a day. The patient was advised to use sunscreen to prevent further hyperpigmentation. Although most lesions fade with time, a topical bleaching agent such as hydroquinone may be prescribed to reduce hyperpigmentation

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Andrea Darby-Stewart, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Wenner C. Photodermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:853-857.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Pruritic rash

The family physician (FP) made the clinical diagnosis of polymorphous light eruption (PMLE). The sparing of the patient’s watch area made it clear that the plaques were photodistributed. PMLE may affect up to 10% of the population with a predilection for females. There are 3 common types of photodermatitis: PMLE, phototoxic eruption, and photoallergic eruption.

PMLE is an idiopathic, delayed type hypersensitivity reaction to ultraviolet A light and, to a lesser extent, ultraviolet B light. PMLE is the most common photo eruption encountered in clinical practice. The rash develops within hours to days of exposure to sunlight and lasts for several days to a week.

There is a broad range of photosensitivity with PMLE. Extremely sensitive individuals can tolerate only minutes of exposure, whereas others require prolonged exposure to sunlight before developing a reaction. PMLE is a recurrent condition that persists for many years in most patients.

The appearance of PMLE varies from person to person. Erythematous pruritic papules, sometimes with vesicles, are most common. Lesions may coalesce to form plaques. The rash typically involves the V of the neck and the arms, the legs, or both. The face tends to be spared. It tends to present in spring/summer, with the first significant UV exposure of the year.

The management of PMLE is aimed at prevention. Patients who have mild disease should avoid sun exposure, wear tightly woven clothing and hats, and use broad-spectrum sunscreens with a sun-protection factor of 50 or higher. Patients with severe PMLE can be desensitized in the spring with the use of phototherapy, and maintained in the nonreactive state with weekly one hour unprotected exposure to sunlight.

In this case, the FP told the patient to avoid sun exposure and started her on oral antihistamines and topical steroids to treat her symptoms.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Chris Wenner, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Wenner C. Photodermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:853-857.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician (FP) made the clinical diagnosis of polymorphous light eruption (PMLE). The sparing of the patient’s watch area made it clear that the plaques were photodistributed. PMLE may affect up to 10% of the population with a predilection for females. There are 3 common types of photodermatitis: PMLE, phototoxic eruption, and photoallergic eruption.

PMLE is an idiopathic, delayed type hypersensitivity reaction to ultraviolet A light and, to a lesser extent, ultraviolet B light. PMLE is the most common photo eruption encountered in clinical practice. The rash develops within hours to days of exposure to sunlight and lasts for several days to a week.

There is a broad range of photosensitivity with PMLE. Extremely sensitive individuals can tolerate only minutes of exposure, whereas others require prolonged exposure to sunlight before developing a reaction. PMLE is a recurrent condition that persists for many years in most patients.

The appearance of PMLE varies from person to person. Erythematous pruritic papules, sometimes with vesicles, are most common. Lesions may coalesce to form plaques. The rash typically involves the V of the neck and the arms, the legs, or both. The face tends to be spared. It tends to present in spring/summer, with the first significant UV exposure of the year.

The management of PMLE is aimed at prevention. Patients who have mild disease should avoid sun exposure, wear tightly woven clothing and hats, and use broad-spectrum sunscreens with a sun-protection factor of 50 or higher. Patients with severe PMLE can be desensitized in the spring with the use of phototherapy, and maintained in the nonreactive state with weekly one hour unprotected exposure to sunlight.

In this case, the FP told the patient to avoid sun exposure and started her on oral antihistamines and topical steroids to treat her symptoms.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Chris Wenner, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Wenner C. Photodermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:853-857.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician (FP) made the clinical diagnosis of polymorphous light eruption (PMLE). The sparing of the patient’s watch area made it clear that the plaques were photodistributed. PMLE may affect up to 10% of the population with a predilection for females. There are 3 common types of photodermatitis: PMLE, phototoxic eruption, and photoallergic eruption.

PMLE is an idiopathic, delayed type hypersensitivity reaction to ultraviolet A light and, to a lesser extent, ultraviolet B light. PMLE is the most common photo eruption encountered in clinical practice. The rash develops within hours to days of exposure to sunlight and lasts for several days to a week.

There is a broad range of photosensitivity with PMLE. Extremely sensitive individuals can tolerate only minutes of exposure, whereas others require prolonged exposure to sunlight before developing a reaction. PMLE is a recurrent condition that persists for many years in most patients.

The appearance of PMLE varies from person to person. Erythematous pruritic papules, sometimes with vesicles, are most common. Lesions may coalesce to form plaques. The rash typically involves the V of the neck and the arms, the legs, or both. The face tends to be spared. It tends to present in spring/summer, with the first significant UV exposure of the year.

The management of PMLE is aimed at prevention. Patients who have mild disease should avoid sun exposure, wear tightly woven clothing and hats, and use broad-spectrum sunscreens with a sun-protection factor of 50 or higher. Patients with severe PMLE can be desensitized in the spring with the use of phototherapy, and maintained in the nonreactive state with weekly one hour unprotected exposure to sunlight.

In this case, the FP told the patient to avoid sun exposure and started her on oral antihistamines and topical steroids to treat her symptoms.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Chris Wenner, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Wenner C. Photodermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:853-857.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

White spots

The FP recognized these areas of hypopigmentation as idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. The FP told the patient that she did not have cancer and described the condition as benign and neither contagious nor dangerous. Next, she explained that the word “idiopathic” was misleading, since ultraviolet damage to melanocytes from the sun was the likely cause.

The patient was happy with the explanation but wanted to know if she would continue to get new white spots. The FP told her that more white spots were a possibility, given that she’d spent a lot of time in the sun. The FP suggested that the patient be diligent about using sunscreen to prevent further sun damage.

A variety of treatments have been used with limited success to treat this condition, including topical steroids, topical retinoids, dermabrasion, and cryotherapy.

In this case, the patient decided not to pursue any treatment options.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hughes K, Usatine R. Vitiligo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:849-852.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP recognized these areas of hypopigmentation as idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. The FP told the patient that she did not have cancer and described the condition as benign and neither contagious nor dangerous. Next, she explained that the word “idiopathic” was misleading, since ultraviolet damage to melanocytes from the sun was the likely cause.

The patient was happy with the explanation but wanted to know if she would continue to get new white spots. The FP told her that more white spots were a possibility, given that she’d spent a lot of time in the sun. The FP suggested that the patient be diligent about using sunscreen to prevent further sun damage.

A variety of treatments have been used with limited success to treat this condition, including topical steroids, topical retinoids, dermabrasion, and cryotherapy.

In this case, the patient decided not to pursue any treatment options.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hughes K, Usatine R. Vitiligo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:849-852.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP recognized these areas of hypopigmentation as idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. The FP told the patient that she did not have cancer and described the condition as benign and neither contagious nor dangerous. Next, she explained that the word “idiopathic” was misleading, since ultraviolet damage to melanocytes from the sun was the likely cause.

The patient was happy with the explanation but wanted to know if she would continue to get new white spots. The FP told her that more white spots were a possibility, given that she’d spent a lot of time in the sun. The FP suggested that the patient be diligent about using sunscreen to prevent further sun damage.

A variety of treatments have been used with limited success to treat this condition, including topical steroids, topical retinoids, dermabrasion, and cryotherapy.

In this case, the patient decided not to pursue any treatment options.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hughes K, Usatine R. Vitiligo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:849-852.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Pigment loss

The FP made the diagnosis of vitiligo. The complete depigmentation and the distribution around the eyes is classic for vitiligo.

Vitiligo is an acquired, progressive loss of pigmentation of the epidermis. It can occur at any age, but typically develops between the ages of 10 and 30 years. Vitiligo occurs in all populations around the world, but is more prominent in those with darker skin. Vitiligo is an autoimmune disease with destruction of melanocytes. The typical distribution involves the face, hands, arms, and genitalia. Depigmentation around body openings such as the eyes, mouth, umbilicus, and anus is common.

Addressing the psychological distress that this disfiguring skin disorder causes should be a primary focus, since little can be done to modify the condition itself. When the area involved is limited and the patient requests treatment, some physicians will use topical high-potency steroids. Success rates are low, however.

Psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) irradiation are somewhat effective treatments for vitiligo (approximately a 30%-60% response rate) when used alone and in combination with topical agents. However, the repigmentation is often spotty and incomplete. Sunscreen is recommended to prevent burns to the depigmented areas.

In this case, the patient’s mother wanted him to be treated. So the child was started on a moderate potency topical steroid to the involved area of the neck. When his mom saw no benefit in one month, she stopped the treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hughes K, Usatine R. Vitiligo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:849-852.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP made the diagnosis of vitiligo. The complete depigmentation and the distribution around the eyes is classic for vitiligo.

Vitiligo is an acquired, progressive loss of pigmentation of the epidermis. It can occur at any age, but typically develops between the ages of 10 and 30 years. Vitiligo occurs in all populations around the world, but is more prominent in those with darker skin. Vitiligo is an autoimmune disease with destruction of melanocytes. The typical distribution involves the face, hands, arms, and genitalia. Depigmentation around body openings such as the eyes, mouth, umbilicus, and anus is common.

Addressing the psychological distress that this disfiguring skin disorder causes should be a primary focus, since little can be done to modify the condition itself. When the area involved is limited and the patient requests treatment, some physicians will use topical high-potency steroids. Success rates are low, however.

Psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) irradiation are somewhat effective treatments for vitiligo (approximately a 30%-60% response rate) when used alone and in combination with topical agents. However, the repigmentation is often spotty and incomplete. Sunscreen is recommended to prevent burns to the depigmented areas.

In this case, the patient’s mother wanted him to be treated. So the child was started on a moderate potency topical steroid to the involved area of the neck. When his mom saw no benefit in one month, she stopped the treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hughes K, Usatine R. Vitiligo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:849-852.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP made the diagnosis of vitiligo. The complete depigmentation and the distribution around the eyes is classic for vitiligo.

Vitiligo is an acquired, progressive loss of pigmentation of the epidermis. It can occur at any age, but typically develops between the ages of 10 and 30 years. Vitiligo occurs in all populations around the world, but is more prominent in those with darker skin. Vitiligo is an autoimmune disease with destruction of melanocytes. The typical distribution involves the face, hands, arms, and genitalia. Depigmentation around body openings such as the eyes, mouth, umbilicus, and anus is common.

Addressing the psychological distress that this disfiguring skin disorder causes should be a primary focus, since little can be done to modify the condition itself. When the area involved is limited and the patient requests treatment, some physicians will use topical high-potency steroids. Success rates are low, however.

Psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) and narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) irradiation are somewhat effective treatments for vitiligo (approximately a 30%-60% response rate) when used alone and in combination with topical agents. However, the repigmentation is often spotty and incomplete. Sunscreen is recommended to prevent burns to the depigmented areas.

In this case, the patient’s mother wanted him to be treated. So the child was started on a moderate potency topical steroid to the involved area of the neck. When his mom saw no benefit in one month, she stopped the treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hughes K, Usatine R. Vitiligo. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:849-852.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Asymptomatic crusted lesions on the palms

AN 86-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a high-grade fever for several days was brought in to our emergency department (ED) for evaluation. The patient lived in a nursing home and was in a persistent vegetative state. She had been bedridden for several years and had a history of stroke and dementia.

While examining the patient, we noticed multiple scattered erythematous keratotic papules and plaques on her face, trunk, and limbs. There were also yellow to brownish compact, thick, scaly, crusted plaques on both of the patient’s hands (FIGURE). We gathered skin scrapings from her palms and sent them to the lab. We also ordered lab work including a complete blood count, urine biochemistry, and a urine culture.

FIGURE

Thick, brownish hyperkeratotic plaques on the palm

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Norwegian scabies

Based on our physical findings and the lab work, we diagnosed Norwegian scabies and urosepsis in this patient.

Norwegian scabies, also known as crusted scabies, is an uncommon form of scabies infestation that was first described in Norway.1 The causative organism is the burrowing mite Sarcoptes scabie, which is the same organism that is involved in ordinary scabies. The difference, though, is that the level of infestation with Norwegian scabies is more severe.

Definitive diagnosis depends on microscopic identification of the mites, their eggs, eggshell fragments, or mite pellets. Patients who have Norwegian scabies also have extremely elevated total serum immunoglobulin E and G levels.2 In addition, these patients are predisposed to secondary infections.

Clinically, multiple yellow to brown hyperkeratotic plaques with significant xerosis are seen on the acral areas, including the scalp, face, and palmoplantar region. The toenails and fingernails may also show dystrophic changes with variable thickening.

Who’s at risk?

In general, patients with dementia or mental retardation and those who are immunocompromised are most susceptible to Norwegian scabies.3 In ordinary scabies, the number of mites is usually less than 20 per individual.3 However, in cases involving an impaired immune response, it is difficult to control the numbers of mites in the infected skin, and a Norwegian scabies host may harbor more than 1 million mites.3

Despite the high mite load, most patients suffer only mild discomfort and tend to ignore the condition.3 This leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment.

A disease that spreads quickly. This disease is transmitted by close skin to skin contact and contact with infested clothing, bedding, or furniture. In nursing homes, patients with unrecognized Norwegian scabies are often the source of transmission to other residents and staff members.4

A diverse collection of diseases in the differential

The differential diagnosis for a rash such as the one our patient had includes tinea manuum, contact dermatitis, syphilis, and palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK).

Tinea manuum is caused by a dermatophyte infection that involves the hands. Its characteristic features are dry hyperkeratotic plaques with thin or coarse scaling on the palms. It often affects the palmar surface and, occasionally, the dorsal aspect of the hands. In most patients, it is associated with tinea pedis, a condition called “two feet-one hand syndrome.” The most common causative organism is Trichophyton rubrum.5

Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of fungal hyphae in skin scrapings dissolved in 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) and examined by light microscopy. It can be treated with a topical antifungal agent. However, in the case of hyperkeratotic or intractable disease, an oral antifungal medication may be needed.

Contact dermatitis is a common inflammatory dermatosis involving the hands, and many cases can be linked to the person’s job. It is often seen in individuals who need to wash their hands frequently (eg, health care workers) and those who are exposed to detergents (eg, restaurant workers).6

Clinical manifestation varies depending on the stage of eczematous progression. In the acute stage, the lesions are moist erythematous papuloplaques. In the subsequent subacute stage, a rash showing mild xerotic erythematous to brownish lesions is seen. Finally, in the chronic stage, the lesions show lichenification, which is thickening of the skin due to inflammation and scratching.3 The mainstay treatment involves simultaneously avoiding contact allergens and applying the proper topical steroid.

Syphilis may involve multiple organs, including the skin, and is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. Although it has different clinical stages, the cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis occurs 4 to 10 weeks after primary infection. The cutaneous features of secondary syphilis are diverse and, thus, the disease is known as the “great imitator.”3

Most rashes are characterized by scaly erythematous maculopapules on the trunk, extremities, palms, and soles. However, microscopic examination of the scales after KOH treatment usually does not reveal any visible organisms. The diagnosis should be correlated with clinical information, including a thorough medical history and serologic data for syphilis. Because syphilis is a bacterial infection, treatment with appropriate systemic antibiotics such as penicillin, doxycycline, or azithromycin is generally effective. (For more on secondary syphilis, see “Photo Rounds: Pruritic rash on trunk” [J Fam Pract. 2011;60:539-542.])

PPK comprises a group of inherited or acquired disorders characterized by abnormal thickening of the palms and soles. The inherited form results from defects in genes encoding the structural components of keratinocytes, which result in abnormal epidermal thickening.3 The acquired form is associated with various inflammatory or infectious skin conditions, including psoriasis and chronic eczema.

Depending on their pattern of appearance on the palms and soles, clinical lesions of PPK can be categorized into 3 forms: diffuse, focal, and punctate.3 Areas including nonvolar skin, teeth, nails, and sweat glands might also be affected. Treatment includes topical keratolytic agents and topical and oral retinoids.

Treatment and decontamination are needed for Norwegian scabies

Because of the large number of mites in the hyperkeratotic lesions in Norwegian scabies, this disease is difficult to manage.7 The mainstay of therapy is daily application of topical scabicidal agents such as 5% permethrin cream, 1% lindane cream, 6% to 10% sulfur-based topical agents, or 12.5% benzyl benzoate lotion. Although treatment plans are individualized, most of these preparations need to be applied for at least one week.

Application of a mixture of keratolytic agents on the hyperkeratotic areas might help the topical medication gain access to the target areas. Prescribing a single oral dose of ivermectin 200 mcg/kg with a topical preparation is also considered an effective approach to treating Norwegian scabies.4

In light of the highly contagious nature of Norwegian scabies, environmental decontamination is required. Clothes, bedding, and towels should be decontaminated by machine washing them in hot water and drying them in the hot cycle.3 Prophylactic treatment with a topical scabicidal agent may be recommended for an entire institution or visitors and family members in order to prevent endemic outbreaks.

Our patient’s recovery

Our patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and her skin lesions were treated with topical mesulphen once daily for 10 days. The cutaneous lesions improved gradually and the patient returned to the nursing home a month later.

CORRESPONDENCE Wei-Ming Wang, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan, R.O.C.; [email protected]

1. Danielsen DG, Boeck W. Treatment of Leprosy or Greek Elephantiasis. Paris, France: JB Balliere; 1848.

2. Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect 2005;50:375-381.

3. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2008.

4. Chosidow O. Clinical practices. Scabies. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1718-1727.

5. Zhan P, Ge YP, Lu XL, et al. A case-control analysis and laboratory study of the two feet-one hand syndrome in two dermatology hospitals in China. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:468-472.

6. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, et al. Hand dermatitis/eczema: current management strategy. J Dermatol. 2010;37:593-610.

7. Chan CC, Lin SJ, Chan YC, et al. Clinical images: infestation by Norwegian scabies. CMAJ. 2009;181:289.-

AN 86-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a high-grade fever for several days was brought in to our emergency department (ED) for evaluation. The patient lived in a nursing home and was in a persistent vegetative state. She had been bedridden for several years and had a history of stroke and dementia.

While examining the patient, we noticed multiple scattered erythematous keratotic papules and plaques on her face, trunk, and limbs. There were also yellow to brownish compact, thick, scaly, crusted plaques on both of the patient’s hands (FIGURE). We gathered skin scrapings from her palms and sent them to the lab. We also ordered lab work including a complete blood count, urine biochemistry, and a urine culture.

FIGURE

Thick, brownish hyperkeratotic plaques on the palm

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Norwegian scabies

Based on our physical findings and the lab work, we diagnosed Norwegian scabies and urosepsis in this patient.

Norwegian scabies, also known as crusted scabies, is an uncommon form of scabies infestation that was first described in Norway.1 The causative organism is the burrowing mite Sarcoptes scabie, which is the same organism that is involved in ordinary scabies. The difference, though, is that the level of infestation with Norwegian scabies is more severe.

Definitive diagnosis depends on microscopic identification of the mites, their eggs, eggshell fragments, or mite pellets. Patients who have Norwegian scabies also have extremely elevated total serum immunoglobulin E and G levels.2 In addition, these patients are predisposed to secondary infections.

Clinically, multiple yellow to brown hyperkeratotic plaques with significant xerosis are seen on the acral areas, including the scalp, face, and palmoplantar region. The toenails and fingernails may also show dystrophic changes with variable thickening.

Who’s at risk?