User login

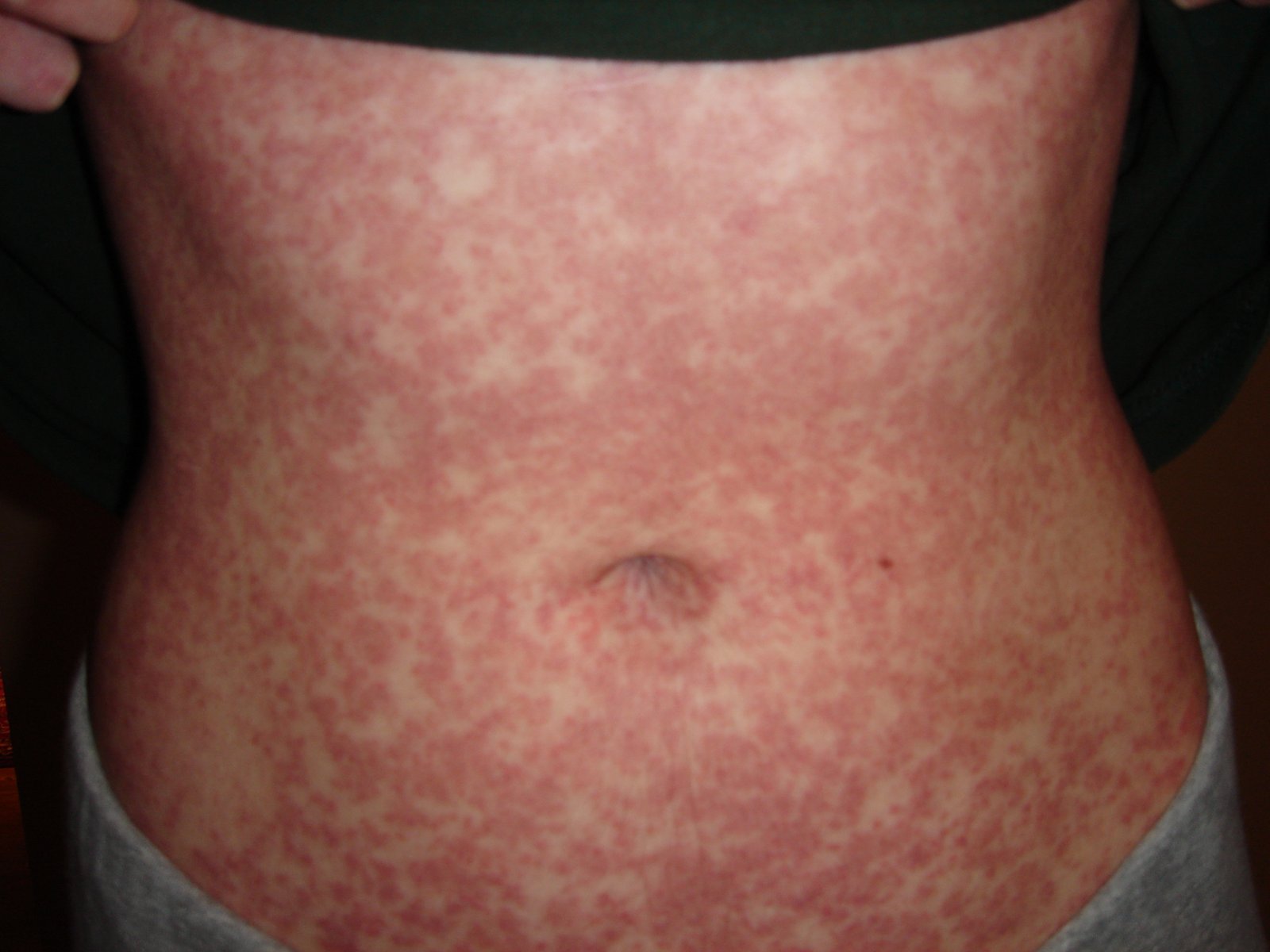

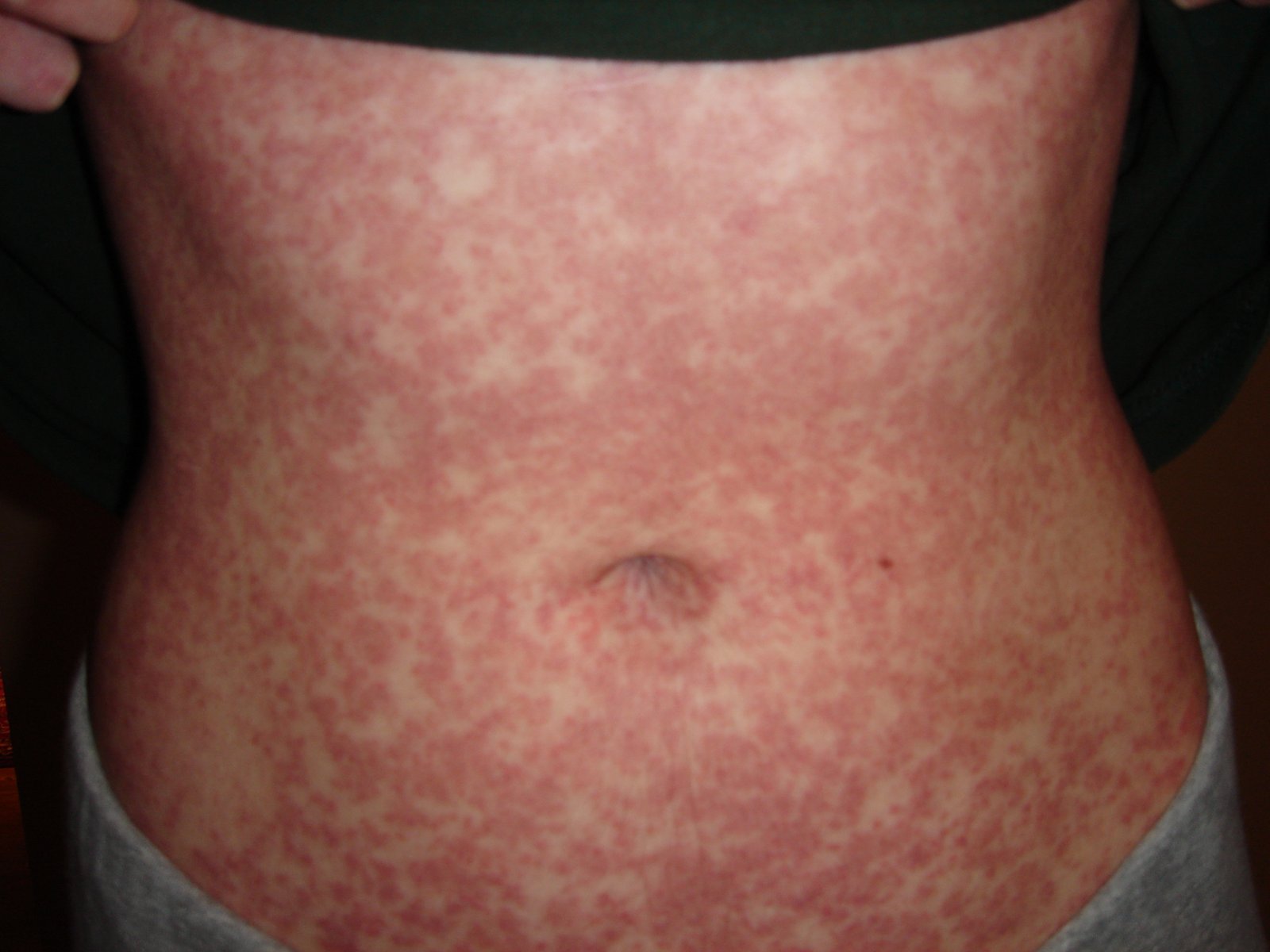

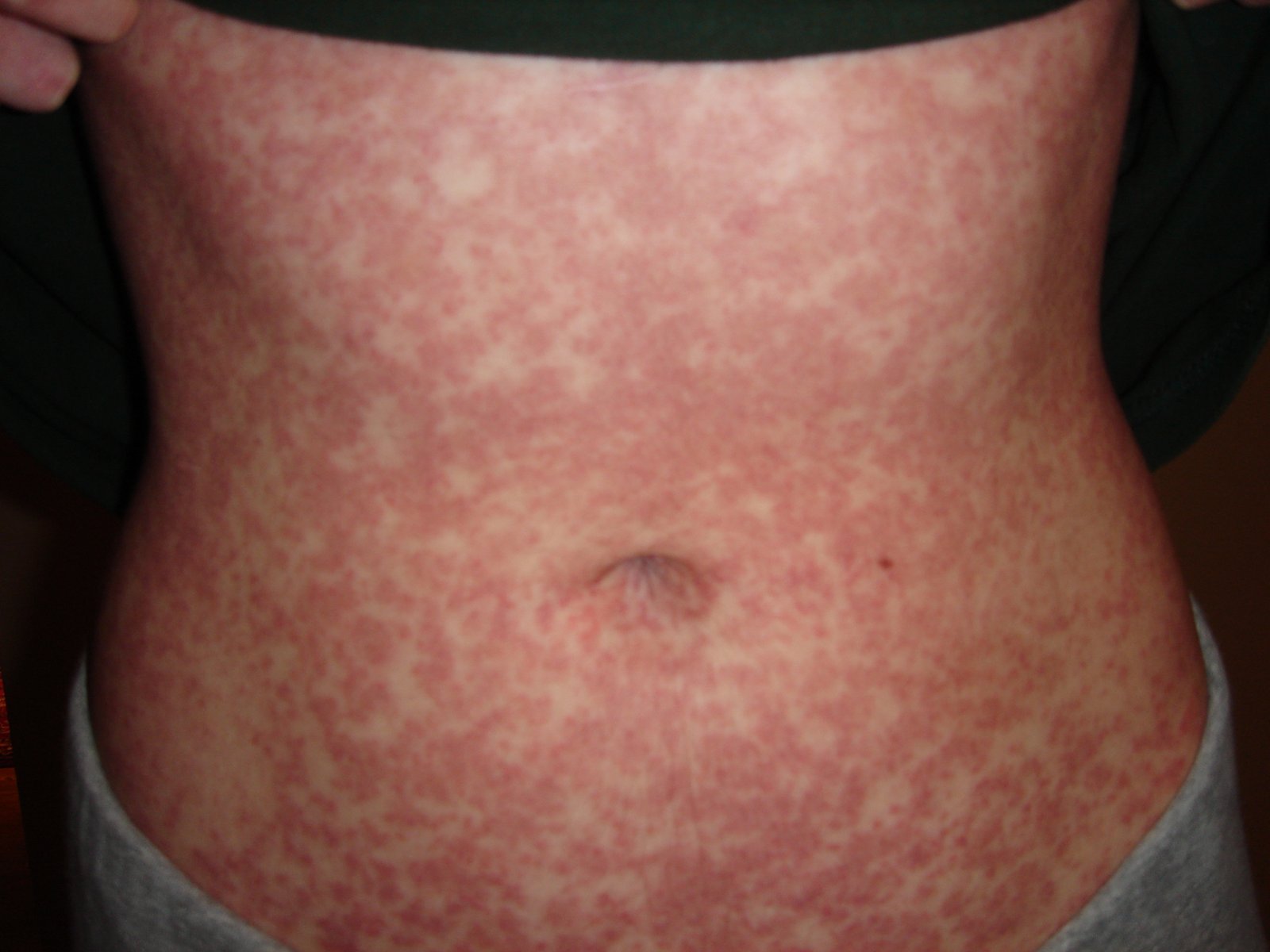

Body rash

The FP suspected mononucleosis and sent the patient for a monospot test, which was positive. This morbilliform rash (like measles) is typical of an amoxicillin drug eruption in a patient with mononucleosis. The amoxicillin was stopped, and diphenhydramine was used for the itching. This is a typical maculopapular drug eruption. Mild desquamation is normal as the eruption resolves. This patient’s exanthem cleared within 5 days of stopping the amoxicillin; there was some slight desquamation on the hands.

It remains unclear if this reaction was a transient immunostimulation or a true drug allergy. For safety purposes, it would be best to avoid giving this patient amoxicillin or ampicillin in the future. It’s possible that the patient may be able to take penicillin or a cephalosporin safely in the future. A referral to an allergist might help to sort out this issue.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Cutaneous drug reactions. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:869-877.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP suspected mononucleosis and sent the patient for a monospot test, which was positive. This morbilliform rash (like measles) is typical of an amoxicillin drug eruption in a patient with mononucleosis. The amoxicillin was stopped, and diphenhydramine was used for the itching. This is a typical maculopapular drug eruption. Mild desquamation is normal as the eruption resolves. This patient’s exanthem cleared within 5 days of stopping the amoxicillin; there was some slight desquamation on the hands.

It remains unclear if this reaction was a transient immunostimulation or a true drug allergy. For safety purposes, it would be best to avoid giving this patient amoxicillin or ampicillin in the future. It’s possible that the patient may be able to take penicillin or a cephalosporin safely in the future. A referral to an allergist might help to sort out this issue.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Cutaneous drug reactions. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:869-877.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP suspected mononucleosis and sent the patient for a monospot test, which was positive. This morbilliform rash (like measles) is typical of an amoxicillin drug eruption in a patient with mononucleosis. The amoxicillin was stopped, and diphenhydramine was used for the itching. This is a typical maculopapular drug eruption. Mild desquamation is normal as the eruption resolves. This patient’s exanthem cleared within 5 days of stopping the amoxicillin; there was some slight desquamation on the hands.

It remains unclear if this reaction was a transient immunostimulation or a true drug allergy. For safety purposes, it would be best to avoid giving this patient amoxicillin or ampicillin in the future. It’s possible that the patient may be able to take penicillin or a cephalosporin safely in the future. A referral to an allergist might help to sort out this issue.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Cutaneous drug reactions. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:869-877.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Unsightly rash on shin

A 60-YEAR-OLD WOMAN came into our primary care clinic and asked that we look at a rash on her left shin. The rash started as a few small red spots 8 months earlier that gradually merged and turned into one shiny irregular area with brownish discoloration. The rash was neither itchy nor painful, and remained unchanged during exposure to sunlight.

The patient indicated that she had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when she was 24 years old and was using a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion device. She said that over the years she’d developed diabetic retinopathy, polyneuropathy, and end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis.

Clinical exam revealed an 8 × 6 cm well-demarcated red-brown irregular plaque on her left shin. The lesion had a yellow atrophic center and extensive telangiectasias (FIGURE). There were no similar lesions anywhere else on her body.

FIGURE

Red-brown plaque over left shin with yellow atrophic center and extensive telangiectasias

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a disorder involving subcutaneous collagen degeneration that results in thickening of blood vessel walls, fat deposition, and the formation of granulomas. It affects up to 1.2% of all patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and occurs in patients without diabetes, although it is less common.1 NLD mostly affects females, with a ratio of 3:1.2 It’s also been described in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, in whom lesions are mostly ulcerated.3

The lesions typically start as multiple shiny, painless, red-brown patches that tend to appear in the lower extremities and slowly coalesce and enlarge over months to years, forming yellow atrophic plaques. The thin overlying epidermis contains many telangiectatic vessels.4 In rare cases, chronic lesions have developed into squamous cell carcinomas.5

A diagnosis is established based on the appearance of the rash and a suggestive history—as was the case with our patient. Lab tests generally aren’t required, but should be performed to check for diabetes (if a diagnosis has not been established) and to explore relevant differential diagnoses.

The differential Dx includes granuloma annulare

In its early stages, the superficial annular lesions of NLD closely resemble granuloma annulare, which is characterized by violaceous or skin-colored annular rings with firm papules or nodules. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis may also resemble the condition, but associated systemic manifestations help distinguish the two. Rarely, paraproteinemias can develop similar lesions (known as necrobiotic xanthogranuloma) that are associated with elevated blood levels of paraproteins.

The cause

The exact etiology of NLD is not known but a number of factors have been implicated, including microangiopathy, local trauma, metabolic changes (eg, glycoprotein deposition in the vascular endothelium, increased platelet aggregation), and immune-mediated deposition of immunoglobulins and fibrinogen in the vascular walls.6

The histologic picture reveals layers of subcutaneous and intradermal interstitial and palisade granulomas. These granulomas are made up of histiocytes and sometimes eosinophils. Surrounding areas show significant degeneration of collagen and nerve endings. Hence, the lesions are generally painless. Surface trauma to the lesions creates ulcerations that occasionally lead to pain. Vasculitic involvement of the traumatic plaque may demonstrate Koebner phenomenon.7

No correlation. NLD does not correlate with glycemic control or with the presence or progression of vascular (or other) complications of diabetes.8 It can, however, be a clue to the presence of diabetes.

Management: Support stockings, steroids

A lack of a clear etiology for NLD makes the treatment challenging. Leg rest may retard progression by alleviating lower extremity edema, and elastic support stockings may be used to protect against trauma (and thus, ulceration).4 Topical and intralesional steroids are helpful for inflammation, but be cautious when using them in atrophic lesions, as they may worsen atrophy. (Steroids should be avoided in lesions with advanced atrophy.) Topical steroids should be started with a low potency formulation (hydrocortisone 2.5% cream) and gradually advanced to a higher potency formulation (clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream).9

Various other therapeutic interventions have been shown to be effective, including tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily for one month to prevent T-cell activation10 and antiplatelet aggregation therapy with aspirin and dipyridamole for 8 weeks.11 A multicenter prospective study showed an improvement of lesions in about two-thirds of patients when topical 0.005% psoralen was applied, followed by twice weekly ultraviolet-A irradiation for a mean of 22 exposures.12 Perilesional heparin injections of 5000 IU have also been shown to improve lesions by preventing micro-occlusion.13 Surgical therapies such as excision and grafting14 and pulse dye laser15 have shown promise in selected cases.

The prognosis

The prognosis of NLD is poor from a cosmetic point of view. Therefore, early treatment should be offered to retard its progression.

We advised our patient to wear elastic support stockings to protect the affected area from trauma. We also told her to apply moisturizing lotion 4 times a day, as well as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment 2 times a day for 8 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE Satyajeet Roy, MD, FACP, Cooper University Hospital,1103 North Kings Highway, Suite 203, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034; [email protected]

1. Jelinek JE. The skin in diabetes. Diabet Med. 1993;10:201-213.

2. Souza AD, El-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Does pancreas transplant in diabetic patients affect the evolution of necrobiosis lipoidica? Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:964-970.

3. Rollins TG, Winkelmann RK. Necrobiosis lipoidica granulomatosis. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum in the nondiabetic. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:537-543.

4. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

5. Lim C, Tschuchnigg M, Lim J. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an area of long-standing necrobiosis lipoidica. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:581-583.

6. Nguyen K, Washenik K, Shupack J. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum treated with chloroquine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl case reports):S34-S36.

7. Miller RA. The Koebner phenomenon. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:192-197.

8. Cohen O, Yaniv R, Karasik A, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica and diabetic control revisited. Med Hypotheses. 1996;46:348-350.

9. Newman BA, Feldman FF. The topical and systemic use of cortisone in dermatology. Calif Med. 1951;75:324-331.

10. Clayton TH, Harrison PV. Successful treatment of chronic ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica with 0.1% topical tacrolimus ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:581-582.

11. Eldor A, Diaz EG, Naparstek E. Treatment of diabetic necrobiosis with aspirin and dipyridamole. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1033.-

12. De Rie MA, Sommer A, Hoekzema R, et al. Treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica with topical psoralen plus ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:743-747.

13. Jetton RL, Lazarus GS. Minidose heparin therapy for vasculitis of atrophie blanche. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:23-26.

14. Marr TJ, Traisman HS, Griffith BH, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum in a juvenile diabetic: treatment by excision and skin grafting. Cutis. 1977;19:348-350.

15. Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum treated with the pulsed dye laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2001;3:143-146.

A 60-YEAR-OLD WOMAN came into our primary care clinic and asked that we look at a rash on her left shin. The rash started as a few small red spots 8 months earlier that gradually merged and turned into one shiny irregular area with brownish discoloration. The rash was neither itchy nor painful, and remained unchanged during exposure to sunlight.

The patient indicated that she had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when she was 24 years old and was using a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion device. She said that over the years she’d developed diabetic retinopathy, polyneuropathy, and end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis.

Clinical exam revealed an 8 × 6 cm well-demarcated red-brown irregular plaque on her left shin. The lesion had a yellow atrophic center and extensive telangiectasias (FIGURE). There were no similar lesions anywhere else on her body.

FIGURE

Red-brown plaque over left shin with yellow atrophic center and extensive telangiectasias

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a disorder involving subcutaneous collagen degeneration that results in thickening of blood vessel walls, fat deposition, and the formation of granulomas. It affects up to 1.2% of all patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and occurs in patients without diabetes, although it is less common.1 NLD mostly affects females, with a ratio of 3:1.2 It’s also been described in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, in whom lesions are mostly ulcerated.3

The lesions typically start as multiple shiny, painless, red-brown patches that tend to appear in the lower extremities and slowly coalesce and enlarge over months to years, forming yellow atrophic plaques. The thin overlying epidermis contains many telangiectatic vessels.4 In rare cases, chronic lesions have developed into squamous cell carcinomas.5

A diagnosis is established based on the appearance of the rash and a suggestive history—as was the case with our patient. Lab tests generally aren’t required, but should be performed to check for diabetes (if a diagnosis has not been established) and to explore relevant differential diagnoses.

The differential Dx includes granuloma annulare

In its early stages, the superficial annular lesions of NLD closely resemble granuloma annulare, which is characterized by violaceous or skin-colored annular rings with firm papules or nodules. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis may also resemble the condition, but associated systemic manifestations help distinguish the two. Rarely, paraproteinemias can develop similar lesions (known as necrobiotic xanthogranuloma) that are associated with elevated blood levels of paraproteins.

The cause

The exact etiology of NLD is not known but a number of factors have been implicated, including microangiopathy, local trauma, metabolic changes (eg, glycoprotein deposition in the vascular endothelium, increased platelet aggregation), and immune-mediated deposition of immunoglobulins and fibrinogen in the vascular walls.6

The histologic picture reveals layers of subcutaneous and intradermal interstitial and palisade granulomas. These granulomas are made up of histiocytes and sometimes eosinophils. Surrounding areas show significant degeneration of collagen and nerve endings. Hence, the lesions are generally painless. Surface trauma to the lesions creates ulcerations that occasionally lead to pain. Vasculitic involvement of the traumatic plaque may demonstrate Koebner phenomenon.7

No correlation. NLD does not correlate with glycemic control or with the presence or progression of vascular (or other) complications of diabetes.8 It can, however, be a clue to the presence of diabetes.

Management: Support stockings, steroids

A lack of a clear etiology for NLD makes the treatment challenging. Leg rest may retard progression by alleviating lower extremity edema, and elastic support stockings may be used to protect against trauma (and thus, ulceration).4 Topical and intralesional steroids are helpful for inflammation, but be cautious when using them in atrophic lesions, as they may worsen atrophy. (Steroids should be avoided in lesions with advanced atrophy.) Topical steroids should be started with a low potency formulation (hydrocortisone 2.5% cream) and gradually advanced to a higher potency formulation (clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream).9

Various other therapeutic interventions have been shown to be effective, including tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily for one month to prevent T-cell activation10 and antiplatelet aggregation therapy with aspirin and dipyridamole for 8 weeks.11 A multicenter prospective study showed an improvement of lesions in about two-thirds of patients when topical 0.005% psoralen was applied, followed by twice weekly ultraviolet-A irradiation for a mean of 22 exposures.12 Perilesional heparin injections of 5000 IU have also been shown to improve lesions by preventing micro-occlusion.13 Surgical therapies such as excision and grafting14 and pulse dye laser15 have shown promise in selected cases.

The prognosis

The prognosis of NLD is poor from a cosmetic point of view. Therefore, early treatment should be offered to retard its progression.

We advised our patient to wear elastic support stockings to protect the affected area from trauma. We also told her to apply moisturizing lotion 4 times a day, as well as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment 2 times a day for 8 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE Satyajeet Roy, MD, FACP, Cooper University Hospital,1103 North Kings Highway, Suite 203, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034; [email protected]

A 60-YEAR-OLD WOMAN came into our primary care clinic and asked that we look at a rash on her left shin. The rash started as a few small red spots 8 months earlier that gradually merged and turned into one shiny irregular area with brownish discoloration. The rash was neither itchy nor painful, and remained unchanged during exposure to sunlight.

The patient indicated that she had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when she was 24 years old and was using a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion device. She said that over the years she’d developed diabetic retinopathy, polyneuropathy, and end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis.

Clinical exam revealed an 8 × 6 cm well-demarcated red-brown irregular plaque on her left shin. The lesion had a yellow atrophic center and extensive telangiectasias (FIGURE). There were no similar lesions anywhere else on her body.

FIGURE

Red-brown plaque over left shin with yellow atrophic center and extensive telangiectasias

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a disorder involving subcutaneous collagen degeneration that results in thickening of blood vessel walls, fat deposition, and the formation of granulomas. It affects up to 1.2% of all patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and occurs in patients without diabetes, although it is less common.1 NLD mostly affects females, with a ratio of 3:1.2 It’s also been described in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, in whom lesions are mostly ulcerated.3

The lesions typically start as multiple shiny, painless, red-brown patches that tend to appear in the lower extremities and slowly coalesce and enlarge over months to years, forming yellow atrophic plaques. The thin overlying epidermis contains many telangiectatic vessels.4 In rare cases, chronic lesions have developed into squamous cell carcinomas.5

A diagnosis is established based on the appearance of the rash and a suggestive history—as was the case with our patient. Lab tests generally aren’t required, but should be performed to check for diabetes (if a diagnosis has not been established) and to explore relevant differential diagnoses.

The differential Dx includes granuloma annulare

In its early stages, the superficial annular lesions of NLD closely resemble granuloma annulare, which is characterized by violaceous or skin-colored annular rings with firm papules or nodules. Skin manifestations of sarcoidosis may also resemble the condition, but associated systemic manifestations help distinguish the two. Rarely, paraproteinemias can develop similar lesions (known as necrobiotic xanthogranuloma) that are associated with elevated blood levels of paraproteins.

The cause

The exact etiology of NLD is not known but a number of factors have been implicated, including microangiopathy, local trauma, metabolic changes (eg, glycoprotein deposition in the vascular endothelium, increased platelet aggregation), and immune-mediated deposition of immunoglobulins and fibrinogen in the vascular walls.6

The histologic picture reveals layers of subcutaneous and intradermal interstitial and palisade granulomas. These granulomas are made up of histiocytes and sometimes eosinophils. Surrounding areas show significant degeneration of collagen and nerve endings. Hence, the lesions are generally painless. Surface trauma to the lesions creates ulcerations that occasionally lead to pain. Vasculitic involvement of the traumatic plaque may demonstrate Koebner phenomenon.7

No correlation. NLD does not correlate with glycemic control or with the presence or progression of vascular (or other) complications of diabetes.8 It can, however, be a clue to the presence of diabetes.

Management: Support stockings, steroids

A lack of a clear etiology for NLD makes the treatment challenging. Leg rest may retard progression by alleviating lower extremity edema, and elastic support stockings may be used to protect against trauma (and thus, ulceration).4 Topical and intralesional steroids are helpful for inflammation, but be cautious when using them in atrophic lesions, as they may worsen atrophy. (Steroids should be avoided in lesions with advanced atrophy.) Topical steroids should be started with a low potency formulation (hydrocortisone 2.5% cream) and gradually advanced to a higher potency formulation (clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream).9

Various other therapeutic interventions have been shown to be effective, including tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily for one month to prevent T-cell activation10 and antiplatelet aggregation therapy with aspirin and dipyridamole for 8 weeks.11 A multicenter prospective study showed an improvement of lesions in about two-thirds of patients when topical 0.005% psoralen was applied, followed by twice weekly ultraviolet-A irradiation for a mean of 22 exposures.12 Perilesional heparin injections of 5000 IU have also been shown to improve lesions by preventing micro-occlusion.13 Surgical therapies such as excision and grafting14 and pulse dye laser15 have shown promise in selected cases.

The prognosis

The prognosis of NLD is poor from a cosmetic point of view. Therefore, early treatment should be offered to retard its progression.

We advised our patient to wear elastic support stockings to protect the affected area from trauma. We also told her to apply moisturizing lotion 4 times a day, as well as topical hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment 2 times a day for 8 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE Satyajeet Roy, MD, FACP, Cooper University Hospital,1103 North Kings Highway, Suite 203, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034; [email protected]

1. Jelinek JE. The skin in diabetes. Diabet Med. 1993;10:201-213.

2. Souza AD, El-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Does pancreas transplant in diabetic patients affect the evolution of necrobiosis lipoidica? Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:964-970.

3. Rollins TG, Winkelmann RK. Necrobiosis lipoidica granulomatosis. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum in the nondiabetic. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:537-543.

4. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

5. Lim C, Tschuchnigg M, Lim J. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an area of long-standing necrobiosis lipoidica. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:581-583.

6. Nguyen K, Washenik K, Shupack J. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum treated with chloroquine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl case reports):S34-S36.

7. Miller RA. The Koebner phenomenon. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:192-197.

8. Cohen O, Yaniv R, Karasik A, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica and diabetic control revisited. Med Hypotheses. 1996;46:348-350.

9. Newman BA, Feldman FF. The topical and systemic use of cortisone in dermatology. Calif Med. 1951;75:324-331.

10. Clayton TH, Harrison PV. Successful treatment of chronic ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica with 0.1% topical tacrolimus ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:581-582.

11. Eldor A, Diaz EG, Naparstek E. Treatment of diabetic necrobiosis with aspirin and dipyridamole. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1033.-

12. De Rie MA, Sommer A, Hoekzema R, et al. Treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica with topical psoralen plus ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:743-747.

13. Jetton RL, Lazarus GS. Minidose heparin therapy for vasculitis of atrophie blanche. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:23-26.

14. Marr TJ, Traisman HS, Griffith BH, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum in a juvenile diabetic: treatment by excision and skin grafting. Cutis. 1977;19:348-350.

15. Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum treated with the pulsed dye laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2001;3:143-146.

1. Jelinek JE. The skin in diabetes. Diabet Med. 1993;10:201-213.

2. Souza AD, El-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Does pancreas transplant in diabetic patients affect the evolution of necrobiosis lipoidica? Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:964-970.

3. Rollins TG, Winkelmann RK. Necrobiosis lipoidica granulomatosis. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum in the nondiabetic. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:537-543.

4. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

5. Lim C, Tschuchnigg M, Lim J. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an area of long-standing necrobiosis lipoidica. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:581-583.

6. Nguyen K, Washenik K, Shupack J. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum treated with chloroquine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl case reports):S34-S36.

7. Miller RA. The Koebner phenomenon. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:192-197.

8. Cohen O, Yaniv R, Karasik A, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica and diabetic control revisited. Med Hypotheses. 1996;46:348-350.

9. Newman BA, Feldman FF. The topical and systemic use of cortisone in dermatology. Calif Med. 1951;75:324-331.

10. Clayton TH, Harrison PV. Successful treatment of chronic ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica with 0.1% topical tacrolimus ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:581-582.

11. Eldor A, Diaz EG, Naparstek E. Treatment of diabetic necrobiosis with aspirin and dipyridamole. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1033.-

12. De Rie MA, Sommer A, Hoekzema R, et al. Treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica with topical psoralen plus ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:743-747.

13. Jetton RL, Lazarus GS. Minidose heparin therapy for vasculitis of atrophie blanche. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:23-26.

14. Marr TJ, Traisman HS, Griffith BH, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum in a juvenile diabetic: treatment by excision and skin grafting. Cutis. 1977;19:348-350.

15. Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum treated with the pulsed dye laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2001;3:143-146.

Abdominal mass

An abdominal ultrasound revealed subcutaneous, peristalsing bowel loops consistent with a ventral hernia. A small amount of ascites was also found.

Four years earlier, this patient had had a prolonged hospitalization for severe cor pulmonale, during which he suffered a perforated cecum. He had multiple abdominal surgeries, including a right hemicolectomy. His postop course was complicated by multisystem organ failure and several nosocomial infections.

Treatment of a ventral hernia involves either an open or laparoscopic surgical correction, often with the placement of a supportive mesh. Repair of epigastric hernias is crucial even in asymptomatic patients due to the high rate of bowel incarceration.

This patient was referred to a hernia specialty clinic at a nationally recognized medical center.

Adapted from: Murdoch W, Morris PA. Photo Rounds: Irregularly shaped abdominal mass. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:227-228.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

An abdominal ultrasound revealed subcutaneous, peristalsing bowel loops consistent with a ventral hernia. A small amount of ascites was also found.

Four years earlier, this patient had had a prolonged hospitalization for severe cor pulmonale, during which he suffered a perforated cecum. He had multiple abdominal surgeries, including a right hemicolectomy. His postop course was complicated by multisystem organ failure and several nosocomial infections.

Treatment of a ventral hernia involves either an open or laparoscopic surgical correction, often with the placement of a supportive mesh. Repair of epigastric hernias is crucial even in asymptomatic patients due to the high rate of bowel incarceration.

This patient was referred to a hernia specialty clinic at a nationally recognized medical center.

Adapted from: Murdoch W, Morris PA. Photo Rounds: Irregularly shaped abdominal mass. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:227-228.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

An abdominal ultrasound revealed subcutaneous, peristalsing bowel loops consistent with a ventral hernia. A small amount of ascites was also found.

Four years earlier, this patient had had a prolonged hospitalization for severe cor pulmonale, during which he suffered a perforated cecum. He had multiple abdominal surgeries, including a right hemicolectomy. His postop course was complicated by multisystem organ failure and several nosocomial infections.

Treatment of a ventral hernia involves either an open or laparoscopic surgical correction, often with the placement of a supportive mesh. Repair of epigastric hernias is crucial even in asymptomatic patients due to the high rate of bowel incarceration.

This patient was referred to a hernia specialty clinic at a nationally recognized medical center.

Adapted from: Murdoch W, Morris PA. Photo Rounds: Irregularly shaped abdominal mass. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:227-228.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Deformity of foot

The patient explained that years earlier, she’d been given a diagnosis of hereditary hemangiomatosis (Maffucci’s syndrome)—a rare genetic disorder characterized by hemangiomas and enchondromas involving the hands, feet, and long bones. The bone and vascular lesions of Maffucci’s syndrome exist at birth or develop during childhood. While the disorder is genetic, there is no familial pattern of inheritance.

Maffucci’s syndrome is associated with various benign and malignant tumors of the bone and cartilage. Patients with Maffucci’s syndrome often require multiple orthopedic surgeries for their enchondromatous deformities and for cosmetic purposes.

Patients with Maffucci’s syndrome should be monitored closely for both skeletal and nonskeletal tumors, particularly of the brain and abdomen. Fortunately this patient was free of internal tumors.

The FP completed the preventive care exam, including her Pap smear. She also suggested that the patient return if she had any signs or symptoms of new growths on her body.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Tran Shellenberger, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds.The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The patient explained that years earlier, she’d been given a diagnosis of hereditary hemangiomatosis (Maffucci’s syndrome)—a rare genetic disorder characterized by hemangiomas and enchondromas involving the hands, feet, and long bones. The bone and vascular lesions of Maffucci’s syndrome exist at birth or develop during childhood. While the disorder is genetic, there is no familial pattern of inheritance.

Maffucci’s syndrome is associated with various benign and malignant tumors of the bone and cartilage. Patients with Maffucci’s syndrome often require multiple orthopedic surgeries for their enchondromatous deformities and for cosmetic purposes.

Patients with Maffucci’s syndrome should be monitored closely for both skeletal and nonskeletal tumors, particularly of the brain and abdomen. Fortunately this patient was free of internal tumors.

The FP completed the preventive care exam, including her Pap smear. She also suggested that the patient return if she had any signs or symptoms of new growths on her body.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Tran Shellenberger, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds.The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The patient explained that years earlier, she’d been given a diagnosis of hereditary hemangiomatosis (Maffucci’s syndrome)—a rare genetic disorder characterized by hemangiomas and enchondromas involving the hands, feet, and long bones. The bone and vascular lesions of Maffucci’s syndrome exist at birth or develop during childhood. While the disorder is genetic, there is no familial pattern of inheritance.

Maffucci’s syndrome is associated with various benign and malignant tumors of the bone and cartilage. Patients with Maffucci’s syndrome often require multiple orthopedic surgeries for their enchondromatous deformities and for cosmetic purposes.

Patients with Maffucci’s syndrome should be monitored closely for both skeletal and nonskeletal tumors, particularly of the brain and abdomen. Fortunately this patient was free of internal tumors.

The FP completed the preventive care exam, including her Pap smear. She also suggested that the patient return if she had any signs or symptoms of new growths on her body.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Tran Shellenberger, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds.The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Red patches on face

The family physician diagnosed a port-wine stain on the face.

Nevus flammeus, or port-wine stains, are congenital vascular malformations that occur in 0.1 to 0.3% of infants as developmental anomalies. They may be associated with rare syndromes such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and Sturge-Weber syndrome. Port-wine stains are vascular ectasias or dilatations thought to arise from a deficiency of sympathetic nervous innervation to the blood vessels. Dilated capillaries are present throughout the dermis layer of the skin.

Port-wine stains are irregular red-to-purple patches that start out smooth in infancy but may develop hypertrophy and a cobblestone texture with age. Nuchal port-wine stains are associated with alopecia areata. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome is characterized by vascular malformations, venous varicosities, and soft tissue hyperplasia. Patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome often have mental retardation, epilepsy, and eye problems.

Port-wine stains tend to affect the face and neck, although lesions may affect any body surface, including mucous membranes. Lesions of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome tend to affect the lower extremities. A diagnosis of Sturge-Weber syndrome requires that a port-wine stain be present in the V1 trigeminal nerve distribution.

Patients with port-wine stains of the eyelids, bilateral trigeminal lesions, and unilateral lesions involving all 3 divisions of the trigeminal nerve are particularly at risk for Sturge-Weber syndrome. The FP noted that this patient had V1 and V2 involvement along with the eyelid.

If Sturge-Weber syndrome is suspected, perform neuroimaging and glaucoma testing. Neuroimaging may reveal leptomeningeal malformations ipsilateral to the port-wine stain. An electroencephalogram may reveal epilepsy. Elevated ocular pressures or visual field deficits may indicate glaucoma. The patient described here denied epilepsy and eye problems and showed no signs of mental retardation. The physician suggested a screening eye exam just to be sure.

Port-wine stains may be treated with make-up. Pulsed-dye laser treatment is another option, albeit an expensive one. Laser treatments blanch most port-wine lesions to some degree, but complete resolution is difficult to achieve and the recurrence rate is high. Patients with port-wine stains should have periodic skin checks as other lesions may develop within the port-wine stains.

After discussing the port-wine stain with the patient, the physician went on to diagnose and treat his cough.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician diagnosed a port-wine stain on the face.

Nevus flammeus, or port-wine stains, are congenital vascular malformations that occur in 0.1 to 0.3% of infants as developmental anomalies. They may be associated with rare syndromes such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and Sturge-Weber syndrome. Port-wine stains are vascular ectasias or dilatations thought to arise from a deficiency of sympathetic nervous innervation to the blood vessels. Dilated capillaries are present throughout the dermis layer of the skin.

Port-wine stains are irregular red-to-purple patches that start out smooth in infancy but may develop hypertrophy and a cobblestone texture with age. Nuchal port-wine stains are associated with alopecia areata. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome is characterized by vascular malformations, venous varicosities, and soft tissue hyperplasia. Patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome often have mental retardation, epilepsy, and eye problems.

Port-wine stains tend to affect the face and neck, although lesions may affect any body surface, including mucous membranes. Lesions of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome tend to affect the lower extremities. A diagnosis of Sturge-Weber syndrome requires that a port-wine stain be present in the V1 trigeminal nerve distribution.

Patients with port-wine stains of the eyelids, bilateral trigeminal lesions, and unilateral lesions involving all 3 divisions of the trigeminal nerve are particularly at risk for Sturge-Weber syndrome. The FP noted that this patient had V1 and V2 involvement along with the eyelid.

If Sturge-Weber syndrome is suspected, perform neuroimaging and glaucoma testing. Neuroimaging may reveal leptomeningeal malformations ipsilateral to the port-wine stain. An electroencephalogram may reveal epilepsy. Elevated ocular pressures or visual field deficits may indicate glaucoma. The patient described here denied epilepsy and eye problems and showed no signs of mental retardation. The physician suggested a screening eye exam just to be sure.

Port-wine stains may be treated with make-up. Pulsed-dye laser treatment is another option, albeit an expensive one. Laser treatments blanch most port-wine lesions to some degree, but complete resolution is difficult to achieve and the recurrence rate is high. Patients with port-wine stains should have periodic skin checks as other lesions may develop within the port-wine stains.

After discussing the port-wine stain with the patient, the physician went on to diagnose and treat his cough.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician diagnosed a port-wine stain on the face.

Nevus flammeus, or port-wine stains, are congenital vascular malformations that occur in 0.1 to 0.3% of infants as developmental anomalies. They may be associated with rare syndromes such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and Sturge-Weber syndrome. Port-wine stains are vascular ectasias or dilatations thought to arise from a deficiency of sympathetic nervous innervation to the blood vessels. Dilated capillaries are present throughout the dermis layer of the skin.

Port-wine stains are irregular red-to-purple patches that start out smooth in infancy but may develop hypertrophy and a cobblestone texture with age. Nuchal port-wine stains are associated with alopecia areata. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome is characterized by vascular malformations, venous varicosities, and soft tissue hyperplasia. Patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome often have mental retardation, epilepsy, and eye problems.

Port-wine stains tend to affect the face and neck, although lesions may affect any body surface, including mucous membranes. Lesions of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome tend to affect the lower extremities. A diagnosis of Sturge-Weber syndrome requires that a port-wine stain be present in the V1 trigeminal nerve distribution.

Patients with port-wine stains of the eyelids, bilateral trigeminal lesions, and unilateral lesions involving all 3 divisions of the trigeminal nerve are particularly at risk for Sturge-Weber syndrome. The FP noted that this patient had V1 and V2 involvement along with the eyelid.

If Sturge-Weber syndrome is suspected, perform neuroimaging and glaucoma testing. Neuroimaging may reveal leptomeningeal malformations ipsilateral to the port-wine stain. An electroencephalogram may reveal epilepsy. Elevated ocular pressures or visual field deficits may indicate glaucoma. The patient described here denied epilepsy and eye problems and showed no signs of mental retardation. The physician suggested a screening eye exam just to be sure.

Port-wine stains may be treated with make-up. Pulsed-dye laser treatment is another option, albeit an expensive one. Laser treatments blanch most port-wine lesions to some degree, but complete resolution is difficult to achieve and the recurrence rate is high. Patients with port-wine stains should have periodic skin checks as other lesions may develop within the port-wine stains.

After discussing the port-wine stain with the patient, the physician went on to diagnose and treat his cough.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Spots on tongue

The family physician suspected that this was a case of undiagnosed hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. HHT is an autosomal dominant vascular disease with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 10,000.

HHT is associated with mutations in genes that regulate transforming growth factor beta in endothelial cells. Arterioles become dilated and connect directly with venules without a capillary in between. Although manifestations are not present at birth, telangiectasias later develop on the skin, mucus membranes, and gastrointestinal tract. In addition, arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) often develop in the hepatic, pulmonary, and cerebral circulations. Any of these lesions may become fragile and prone to bleeding. These AVMs may require surgical resection if they bleed profusely.

HHT is diagnosed if 3 of the following 4 criteria are met: 1) recurrent spontaneous nosebleeds (the presenting sign in more than 90% of patients, often during childhood), 2) mucocutaneous telangiectasia (typically develops in the third decade of life), 3) visceral involvement (lungs, brain, liver, colon), and 4) an affected first-degree relative.

Patients with HHT have lesions on the tongue, lips, nasal mucosa, hands, and feet, though the number—and location—of lesions varies. If a patient has HHT, obtain a complete blood count and iron studies. Patients are at higher risk for iron-deficiency anemia due to recurrent nosebleeds and/or gastrointestinal bleeding.

HHT has no cure. Oral iron supplementation and transfusions are sometimes needed due to bleeding. Few randomized controlled trials exist regarding treatment of bleeding. Case reports and uncontrolled studies regarding epistaxis treatment show some benefit from laser treatment, surgery, embolization, and topical therapy. Cauterization is not recommended due to complications from local tissue damage. Embolization procedures have been described for AVMs in the liver, lungs, and brain. Surgical resection of AVMs is sometimes done as a last resort when other measures fail.

In short, it is often best to do as little intervention as possible with HHT, and if so, with input from specialists experienced with this disease, as complications and recurrence are frequently encountered.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician suspected that this was a case of undiagnosed hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. HHT is an autosomal dominant vascular disease with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 10,000.

HHT is associated with mutations in genes that regulate transforming growth factor beta in endothelial cells. Arterioles become dilated and connect directly with venules without a capillary in between. Although manifestations are not present at birth, telangiectasias later develop on the skin, mucus membranes, and gastrointestinal tract. In addition, arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) often develop in the hepatic, pulmonary, and cerebral circulations. Any of these lesions may become fragile and prone to bleeding. These AVMs may require surgical resection if they bleed profusely.

HHT is diagnosed if 3 of the following 4 criteria are met: 1) recurrent spontaneous nosebleeds (the presenting sign in more than 90% of patients, often during childhood), 2) mucocutaneous telangiectasia (typically develops in the third decade of life), 3) visceral involvement (lungs, brain, liver, colon), and 4) an affected first-degree relative.

Patients with HHT have lesions on the tongue, lips, nasal mucosa, hands, and feet, though the number—and location—of lesions varies. If a patient has HHT, obtain a complete blood count and iron studies. Patients are at higher risk for iron-deficiency anemia due to recurrent nosebleeds and/or gastrointestinal bleeding.

HHT has no cure. Oral iron supplementation and transfusions are sometimes needed due to bleeding. Few randomized controlled trials exist regarding treatment of bleeding. Case reports and uncontrolled studies regarding epistaxis treatment show some benefit from laser treatment, surgery, embolization, and topical therapy. Cauterization is not recommended due to complications from local tissue damage. Embolization procedures have been described for AVMs in the liver, lungs, and brain. Surgical resection of AVMs is sometimes done as a last resort when other measures fail.

In short, it is often best to do as little intervention as possible with HHT, and if so, with input from specialists experienced with this disease, as complications and recurrence are frequently encountered.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician suspected that this was a case of undiagnosed hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. HHT is an autosomal dominant vascular disease with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 10,000.

HHT is associated with mutations in genes that regulate transforming growth factor beta in endothelial cells. Arterioles become dilated and connect directly with venules without a capillary in between. Although manifestations are not present at birth, telangiectasias later develop on the skin, mucus membranes, and gastrointestinal tract. In addition, arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) often develop in the hepatic, pulmonary, and cerebral circulations. Any of these lesions may become fragile and prone to bleeding. These AVMs may require surgical resection if they bleed profusely.

HHT is diagnosed if 3 of the following 4 criteria are met: 1) recurrent spontaneous nosebleeds (the presenting sign in more than 90% of patients, often during childhood), 2) mucocutaneous telangiectasia (typically develops in the third decade of life), 3) visceral involvement (lungs, brain, liver, colon), and 4) an affected first-degree relative.

Patients with HHT have lesions on the tongue, lips, nasal mucosa, hands, and feet, though the number—and location—of lesions varies. If a patient has HHT, obtain a complete blood count and iron studies. Patients are at higher risk for iron-deficiency anemia due to recurrent nosebleeds and/or gastrointestinal bleeding.

HHT has no cure. Oral iron supplementation and transfusions are sometimes needed due to bleeding. Few randomized controlled trials exist regarding treatment of bleeding. Case reports and uncontrolled studies regarding epistaxis treatment show some benefit from laser treatment, surgery, embolization, and topical therapy. Cauterization is not recommended due to complications from local tissue damage. Embolization procedures have been described for AVMs in the liver, lungs, and brain. Surgical resection of AVMs is sometimes done as a last resort when other measures fail.

In short, it is often best to do as little intervention as possible with HHT, and if so, with input from specialists experienced with this disease, as complications and recurrence are frequently encountered.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Hereditary vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:865-868.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Purple growths on arm

A punch biopsy on one of the small purple spots on the patient’s arm revealed that the growths were glomangiomas, also known as glomuvenous malformations and glomus tumors. Glomangiomas are rare and are caused by abnormal synthesis of the protein glomulin. About two-thirds of patients with glomangiomas have a family history of similar lesions.

Glomangiomas are blue-purple, partially compressible nodules with a cobblestone appearance. Lesions are tender to the touch and tend to occur on the extremities. Solitary glomangiomas often occur in the nail bed.

Skin biopsy of glomangiomas reveals distinct rows of glomus cells that surround distorted vascular channels. Isolated glomangiomas may be surgically excised. Sclerotherapy may be useful for multiple lesions or large segmental lesions. This patient was referred to a vascular surgeon to discuss treatment options.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck, Sr., MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Acquired vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:861-864.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

A punch biopsy on one of the small purple spots on the patient’s arm revealed that the growths were glomangiomas, also known as glomuvenous malformations and glomus tumors. Glomangiomas are rare and are caused by abnormal synthesis of the protein glomulin. About two-thirds of patients with glomangiomas have a family history of similar lesions.

Glomangiomas are blue-purple, partially compressible nodules with a cobblestone appearance. Lesions are tender to the touch and tend to occur on the extremities. Solitary glomangiomas often occur in the nail bed.

Skin biopsy of glomangiomas reveals distinct rows of glomus cells that surround distorted vascular channels. Isolated glomangiomas may be surgically excised. Sclerotherapy may be useful for multiple lesions or large segmental lesions. This patient was referred to a vascular surgeon to discuss treatment options.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck, Sr., MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Acquired vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:861-864.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

A punch biopsy on one of the small purple spots on the patient’s arm revealed that the growths were glomangiomas, also known as glomuvenous malformations and glomus tumors. Glomangiomas are rare and are caused by abnormal synthesis of the protein glomulin. About two-thirds of patients with glomangiomas have a family history of similar lesions.

Glomangiomas are blue-purple, partially compressible nodules with a cobblestone appearance. Lesions are tender to the touch and tend to occur on the extremities. Solitary glomangiomas often occur in the nail bed.

Skin biopsy of glomangiomas reveals distinct rows of glomus cells that surround distorted vascular channels. Isolated glomangiomas may be surgically excised. Sclerotherapy may be useful for multiple lesions or large segmental lesions. This patient was referred to a vascular surgeon to discuss treatment options.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck, Sr., MD. This case was adapted from: Hitzeman N. Acquired vascular lesions in adults. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:861-864.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Acral papular rash in a 2-year-old boy

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY was referred to our outpatient department in the spring with a mild pruritic rash that had appeared on his face, arms, and legs over the previous 2 weeks. His family said that the boy had developed an enteroviral infection the month before. Furthermore, he had a 6-month history of acute myeloid leukemia.

On examination, the child was afebrile, with numerous monomorphous flesh-colored to erythematous papules on his face and on the extensor sites of his limbs ( FIGURE ). However, his trunk, palms, and soles were spared.

FIGURE

Flesh-colored to erythematous papules with a monomorphous appearance

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS) is a pediatric disease whose incidence and prevalence are unknown. Children who have GCS may be given a diagnosis of “nonspecific viral exanthem” or “viral rash” and, as a result, the condition may be underdiagnosed.1

GCS—also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood—affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years.2 The pathogenesis of GCS is unclear, but is believed to involve a cutaneous reaction pattern related to viral and bacterial infections or to vaccination.3 It is associated with the hepatitis B virus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and other viral infections. The eruption has also occurred following vaccination (hepatitis A, others).4

GCS is usually diagnosed clinically. Physical examination typically shows discrete, monomorphous, flesh-colored or erythematous flat-topped papulovesicles distributed symmetrically on the cheeks and on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks. The trunk, palms, and soles are usually spared. This distribution pattern is responsible for the name “papular acrodermatitis of childhood.” The lesions are usually asymptomatic, but may be accompanied by a low-grade fever, diarrhea, or malaise.5

Avoid confusing GCS with these 4 conditions

The differential diagnosis for GCS includes miliaria rubra, papular urticaria, lichen nitidus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Miliaria rubra (“prickly heat”) is caused when keratinous plugs occlude the sweat glands. Retrograde pressure may cause rupture of the sweat duct and leakage of sweat into the surrounding tissue, thereby inducing inflammation. Most cases of miliaria rubra occur in hot and humid conditions. However, infants may develop such eruptions in winter if they are dressed too warmly indoors.4

Miliaria rubra manifests as superficial, erythematous, minute papulovesicles with nonfollicular distribution. The lesions, which cause a prickly sensation, are typically localized in flexural regions such as the neck, groin, and axilla, and may be confused with candidiasis or folliculitis.

Cooling by regulation of environmental temperatures and removing excessive clothing can dramatically reduce miliaria rubra. Antipyretics can relieve the symptoms in febrile patients. Topical agents are not recommended because they may exacerbate the skin eruptions.4

Papular urticaria predominantly affects children and is caused by allergic hypersensitivity to insect bites.6 The skin lesions are intensely pruritic and are initially characterized by multiple small erythematous wheals and later progress to pruritic brownish papules.3 Some lesions may have a central punctum. The patient’s age and a history of symmetrically distributed lesions, hypersensitivity, and exposure to animals or insects can help diagnose papular urticaria.6 Lesions are typically observed on exposed areas, can persist for days or weeks, and usually occur in the summer.7

Management of papular urticaria includes the 3 Ps:

- Protection. Children should wear protective clothing for outdoor play and use insect repellent.

- Pruritus control. Topical high-potency steroids and antihistamines may help with individual lesions, but may be ineffective when the inflammatory process extends to the dermis and the fat.

- Patience. Although there is a chance that papular urticaria will be persistent and recurrent, it typically improves with time.6

Lichen nitidus is rare and when it does occur, it typically develops in children.8 Some lesions subside spontaneously, but others may persist for as long as several years.8

Lichen nitidus is clinically manifested as asymptomatic, discrete, flesh-colored, shiny, pinpoint-to-pinhead-sized papules; these papules are sharply demarcated and have fine scales. The most commonly affected sites are the genitalia, chest, abdomen, and upper extremities.8-10 The isomorphic condition called Koebner phenomenon is observed in most cases.3

Lichen nitidus is diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation. Biopsy is indicated only when atypical morphology and distribution are observed. Histologically, the pathognomonic features of lichen nitidus include focal granulomas containing lymphohistiocytic cells in the papillary dermis.

Lichen nitidus usually regresses spontaneously and most patients do not require intervention; treatment is required only when the patient complains of pruritus or cosmetically undesirable effects.5 Topical glucocorticoid treatment may provide good results in such cases.8

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by poxvirus infection and generally affects young children. It is asymptomatic and presents with small pearly white or pink round/oval papules that may have umbilication. The papules are often 2 to 5 mm in diameter, but can be as large as 3 cm (a giant molluscum). Most papules appear in intertriginous sites such as the groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa.

Transmission occurs by direct mucous membrane or skin contact, leading to autoinoculation.11 Patients should not share towels or bath water and must avoid swimming in public pools to reduce the risk of spreading the infection.12

The individual lesions usually persist for 6 to 9 months but may last for years. Most lesions resolve spontaneously and heal without scarring. Active treatment is used for cosmetic and epidemiologic reasons and includes curettage, cryotherapy, cantharidin, and topical imiquimod.11 There is no consensus about the dosage and duration in current therapy modalities, but some experts suggest liquid cantharidin (0.7%-0.9%).3

Management of GCS? Let it run its course

Most patients with GCS do not need treatment because it is a self-limited benign disease. Although the course is variable and the skin lesions may persist for up to 60 days, the lesions will heal without scarring.2

Postinflammation hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is rarely seen. In patients who have severe pruritus, topical antipruritic lotions or oral histamines can provide relief.5 Medium-potency topical steroids may have some benefits, but patients should be closely monitored because there have been reports of exacerbations of lesions with steroid use.2

A good outcome. In the case of our patient, the lesions resolved one week after applying 0.1% mometasone furoate cream once a day.

CORRESPONDENCE Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan R.O.C.; [email protected]

1. Jindal T, Arora VK. Gianotti-crosti syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:683-684.

2. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-145.

3. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2008.

4. Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2007.

5. Wu CY, Huang WH. Question: can you identify this condition? Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:712-716.

6. Hernandez RG, Cohen BA. Insect bite-induced hypersensitivity and the SCRATCH principles: a new approach to papular urticaria. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e189-e196.

7. Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Urticarial lesions: if not urticaria, what else? The differential diagnosis of urticaria: part I. Cutaneous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:541-555.

8. Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

9. Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

10. Kim YC, Shim SD. Two cases of generalized lichen nitidus treated successfully with narrow-band UV-B phototherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:615-617.

11. Jones S, Kress D. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum and herpes simplex virus cutaneous infections. Cutis. 2007;79(4 suppl):11-17.

12. Silverberg NB. Warts and molluscum in children. Adv Dermatol. 2004;20:23-73.

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY was referred to our outpatient department in the spring with a mild pruritic rash that had appeared on his face, arms, and legs over the previous 2 weeks. His family said that the boy had developed an enteroviral infection the month before. Furthermore, he had a 6-month history of acute myeloid leukemia.

On examination, the child was afebrile, with numerous monomorphous flesh-colored to erythematous papules on his face and on the extensor sites of his limbs ( FIGURE ). However, his trunk, palms, and soles were spared.

FIGURE

Flesh-colored to erythematous papules with a monomorphous appearance

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS) is a pediatric disease whose incidence and prevalence are unknown. Children who have GCS may be given a diagnosis of “nonspecific viral exanthem” or “viral rash” and, as a result, the condition may be underdiagnosed.1

GCS—also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood—affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years.2 The pathogenesis of GCS is unclear, but is believed to involve a cutaneous reaction pattern related to viral and bacterial infections or to vaccination.3 It is associated with the hepatitis B virus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and other viral infections. The eruption has also occurred following vaccination (hepatitis A, others).4

GCS is usually diagnosed clinically. Physical examination typically shows discrete, monomorphous, flesh-colored or erythematous flat-topped papulovesicles distributed symmetrically on the cheeks and on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks. The trunk, palms, and soles are usually spared. This distribution pattern is responsible for the name “papular acrodermatitis of childhood.” The lesions are usually asymptomatic, but may be accompanied by a low-grade fever, diarrhea, or malaise.5

Avoid confusing GCS with these 4 conditions

The differential diagnosis for GCS includes miliaria rubra, papular urticaria, lichen nitidus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Miliaria rubra (“prickly heat”) is caused when keratinous plugs occlude the sweat glands. Retrograde pressure may cause rupture of the sweat duct and leakage of sweat into the surrounding tissue, thereby inducing inflammation. Most cases of miliaria rubra occur in hot and humid conditions. However, infants may develop such eruptions in winter if they are dressed too warmly indoors.4

Miliaria rubra manifests as superficial, erythematous, minute papulovesicles with nonfollicular distribution. The lesions, which cause a prickly sensation, are typically localized in flexural regions such as the neck, groin, and axilla, and may be confused with candidiasis or folliculitis.

Cooling by regulation of environmental temperatures and removing excessive clothing can dramatically reduce miliaria rubra. Antipyretics can relieve the symptoms in febrile patients. Topical agents are not recommended because they may exacerbate the skin eruptions.4

Papular urticaria predominantly affects children and is caused by allergic hypersensitivity to insect bites.6 The skin lesions are intensely pruritic and are initially characterized by multiple small erythematous wheals and later progress to pruritic brownish papules.3 Some lesions may have a central punctum. The patient’s age and a history of symmetrically distributed lesions, hypersensitivity, and exposure to animals or insects can help diagnose papular urticaria.6 Lesions are typically observed on exposed areas, can persist for days or weeks, and usually occur in the summer.7

Management of papular urticaria includes the 3 Ps:

- Protection. Children should wear protective clothing for outdoor play and use insect repellent.

- Pruritus control. Topical high-potency steroids and antihistamines may help with individual lesions, but may be ineffective when the inflammatory process extends to the dermis and the fat.

- Patience. Although there is a chance that papular urticaria will be persistent and recurrent, it typically improves with time.6

Lichen nitidus is rare and when it does occur, it typically develops in children.8 Some lesions subside spontaneously, but others may persist for as long as several years.8

Lichen nitidus is clinically manifested as asymptomatic, discrete, flesh-colored, shiny, pinpoint-to-pinhead-sized papules; these papules are sharply demarcated and have fine scales. The most commonly affected sites are the genitalia, chest, abdomen, and upper extremities.8-10 The isomorphic condition called Koebner phenomenon is observed in most cases.3

Lichen nitidus is diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation. Biopsy is indicated only when atypical morphology and distribution are observed. Histologically, the pathognomonic features of lichen nitidus include focal granulomas containing lymphohistiocytic cells in the papillary dermis.

Lichen nitidus usually regresses spontaneously and most patients do not require intervention; treatment is required only when the patient complains of pruritus or cosmetically undesirable effects.5 Topical glucocorticoid treatment may provide good results in such cases.8

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by poxvirus infection and generally affects young children. It is asymptomatic and presents with small pearly white or pink round/oval papules that may have umbilication. The papules are often 2 to 5 mm in diameter, but can be as large as 3 cm (a giant molluscum). Most papules appear in intertriginous sites such as the groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa.

Transmission occurs by direct mucous membrane or skin contact, leading to autoinoculation.11 Patients should not share towels or bath water and must avoid swimming in public pools to reduce the risk of spreading the infection.12

The individual lesions usually persist for 6 to 9 months but may last for years. Most lesions resolve spontaneously and heal without scarring. Active treatment is used for cosmetic and epidemiologic reasons and includes curettage, cryotherapy, cantharidin, and topical imiquimod.11 There is no consensus about the dosage and duration in current therapy modalities, but some experts suggest liquid cantharidin (0.7%-0.9%).3

Management of GCS? Let it run its course

Most patients with GCS do not need treatment because it is a self-limited benign disease. Although the course is variable and the skin lesions may persist for up to 60 days, the lesions will heal without scarring.2

Postinflammation hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is rarely seen. In patients who have severe pruritus, topical antipruritic lotions or oral histamines can provide relief.5 Medium-potency topical steroids may have some benefits, but patients should be closely monitored because there have been reports of exacerbations of lesions with steroid use.2

A good outcome. In the case of our patient, the lesions resolved one week after applying 0.1% mometasone furoate cream once a day.

CORRESPONDENCE Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan R.O.C.; [email protected]

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY was referred to our outpatient department in the spring with a mild pruritic rash that had appeared on his face, arms, and legs over the previous 2 weeks. His family said that the boy had developed an enteroviral infection the month before. Furthermore, he had a 6-month history of acute myeloid leukemia.

On examination, the child was afebrile, with numerous monomorphous flesh-colored to erythematous papules on his face and on the extensor sites of his limbs ( FIGURE ). However, his trunk, palms, and soles were spared.

FIGURE

Flesh-colored to erythematous papules with a monomorphous appearance

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS) is a pediatric disease whose incidence and prevalence are unknown. Children who have GCS may be given a diagnosis of “nonspecific viral exanthem” or “viral rash” and, as a result, the condition may be underdiagnosed.1

GCS—also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood—affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years.2 The pathogenesis of GCS is unclear, but is believed to involve a cutaneous reaction pattern related to viral and bacterial infections or to vaccination.3 It is associated with the hepatitis B virus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and other viral infections. The eruption has also occurred following vaccination (hepatitis A, others).4

GCS is usually diagnosed clinically. Physical examination typically shows discrete, monomorphous, flesh-colored or erythematous flat-topped papulovesicles distributed symmetrically on the cheeks and on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks. The trunk, palms, and soles are usually spared. This distribution pattern is responsible for the name “papular acrodermatitis of childhood.” The lesions are usually asymptomatic, but may be accompanied by a low-grade fever, diarrhea, or malaise.5

Avoid confusing GCS with these 4 conditions

The differential diagnosis for GCS includes miliaria rubra, papular urticaria, lichen nitidus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Miliaria rubra (“prickly heat”) is caused when keratinous plugs occlude the sweat glands. Retrograde pressure may cause rupture of the sweat duct and leakage of sweat into the surrounding tissue, thereby inducing inflammation. Most cases of miliaria rubra occur in hot and humid conditions. However, infants may develop such eruptions in winter if they are dressed too warmly indoors.4

Miliaria rubra manifests as superficial, erythematous, minute papulovesicles with nonfollicular distribution. The lesions, which cause a prickly sensation, are typically localized in flexural regions such as the neck, groin, and axilla, and may be confused with candidiasis or folliculitis.

Cooling by regulation of environmental temperatures and removing excessive clothing can dramatically reduce miliaria rubra. Antipyretics can relieve the symptoms in febrile patients. Topical agents are not recommended because they may exacerbate the skin eruptions.4

Papular urticaria predominantly affects children and is caused by allergic hypersensitivity to insect bites.6 The skin lesions are intensely pruritic and are initially characterized by multiple small erythematous wheals and later progress to pruritic brownish papules.3 Some lesions may have a central punctum. The patient’s age and a history of symmetrically distributed lesions, hypersensitivity, and exposure to animals or insects can help diagnose papular urticaria.6 Lesions are typically observed on exposed areas, can persist for days or weeks, and usually occur in the summer.7

Management of papular urticaria includes the 3 Ps:

- Protection. Children should wear protective clothing for outdoor play and use insect repellent.

- Pruritus control. Topical high-potency steroids and antihistamines may help with individual lesions, but may be ineffective when the inflammatory process extends to the dermis and the fat.

- Patience. Although there is a chance that papular urticaria will be persistent and recurrent, it typically improves with time.6

Lichen nitidus is rare and when it does occur, it typically develops in children.8 Some lesions subside spontaneously, but others may persist for as long as several years.8