User login

Body rash

The family physician diagnosed Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) showing mucosal involvement of the eyes and mouth.

Drugs most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN are sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been identified as the most common infectious cause of SJS. Other agents or triggers include radiation therapy, sunlight, pregnancy, connective tissue disease, and menstruation.

SJS is diagnosed when <10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when 10%-30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. The pathogenesis of SJS and TEN remains unknown, however recent studies have shown that it may be due to a host-specific, cell-mediated immune response to an antigenic stimulus that activates cytotoxic T-cells and results in damage to keratinocytes.

In both SJS and TEN, patients may have blisters that develop on dusky or purpuric macules. The epidermal detachment (skin peeling) seen in SJS and TEN appears to result from epidermal necrosis in the absence of substantial dermal inflammation. Lesions may progress to form areas of central necrosis, bullae, and areas of denudation.

Fever of >39° C is often present, as was seen with this boy. In addition to skin involvement, there is involvement of at least 2 mucosal surfaces such as the eyes, oral cavity, upper airway, esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, or the anogenital mucosa.

Large areas of epidermal detachment occur. Severe pain can occur from mucosal ulcerations, but skin tenderness is minimal. Skin erosions lead to increased insensible blood and fluid losses, as well as an increased risk of bacterial superinfection and sepsis.

Early diagnosis is imperative so that triggering agents can be discontinued and supportive therapy can be started. Treatment is mainly supportive and if there is a large amount of desquamation, the patient may require intensive care or placement in a burn unit.

This boy was immediately hospitalized and given IV fluids. The penicillin was stopped and an infectious disease consult was called. His oral lesions were managed with mouthwashes and glycerin swabs. His skin lesions were cleansed with saline and he was examined daily for secondary infections. An ophthalmologist was consulted due to the high risk of ocular sequelae.

Photo courtesy of Dan Stulberg, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana, C. Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician diagnosed Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) showing mucosal involvement of the eyes and mouth.

Drugs most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN are sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been identified as the most common infectious cause of SJS. Other agents or triggers include radiation therapy, sunlight, pregnancy, connective tissue disease, and menstruation.

SJS is diagnosed when <10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when 10%-30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. The pathogenesis of SJS and TEN remains unknown, however recent studies have shown that it may be due to a host-specific, cell-mediated immune response to an antigenic stimulus that activates cytotoxic T-cells and results in damage to keratinocytes.

In both SJS and TEN, patients may have blisters that develop on dusky or purpuric macules. The epidermal detachment (skin peeling) seen in SJS and TEN appears to result from epidermal necrosis in the absence of substantial dermal inflammation. Lesions may progress to form areas of central necrosis, bullae, and areas of denudation.

Fever of >39° C is often present, as was seen with this boy. In addition to skin involvement, there is involvement of at least 2 mucosal surfaces such as the eyes, oral cavity, upper airway, esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, or the anogenital mucosa.

Large areas of epidermal detachment occur. Severe pain can occur from mucosal ulcerations, but skin tenderness is minimal. Skin erosions lead to increased insensible blood and fluid losses, as well as an increased risk of bacterial superinfection and sepsis.

Early diagnosis is imperative so that triggering agents can be discontinued and supportive therapy can be started. Treatment is mainly supportive and if there is a large amount of desquamation, the patient may require intensive care or placement in a burn unit.

This boy was immediately hospitalized and given IV fluids. The penicillin was stopped and an infectious disease consult was called. His oral lesions were managed with mouthwashes and glycerin swabs. His skin lesions were cleansed with saline and he was examined daily for secondary infections. An ophthalmologist was consulted due to the high risk of ocular sequelae.

Photo courtesy of Dan Stulberg, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana, C. Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician diagnosed Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) showing mucosal involvement of the eyes and mouth.

Drugs most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN are sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been identified as the most common infectious cause of SJS. Other agents or triggers include radiation therapy, sunlight, pregnancy, connective tissue disease, and menstruation.

SJS is diagnosed when <10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when 10%-30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. The pathogenesis of SJS and TEN remains unknown, however recent studies have shown that it may be due to a host-specific, cell-mediated immune response to an antigenic stimulus that activates cytotoxic T-cells and results in damage to keratinocytes.

In both SJS and TEN, patients may have blisters that develop on dusky or purpuric macules. The epidermal detachment (skin peeling) seen in SJS and TEN appears to result from epidermal necrosis in the absence of substantial dermal inflammation. Lesions may progress to form areas of central necrosis, bullae, and areas of denudation.

Fever of >39° C is often present, as was seen with this boy. In addition to skin involvement, there is involvement of at least 2 mucosal surfaces such as the eyes, oral cavity, upper airway, esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, or the anogenital mucosa.

Large areas of epidermal detachment occur. Severe pain can occur from mucosal ulcerations, but skin tenderness is minimal. Skin erosions lead to increased insensible blood and fluid losses, as well as an increased risk of bacterial superinfection and sepsis.

Early diagnosis is imperative so that triggering agents can be discontinued and supportive therapy can be started. Treatment is mainly supportive and if there is a large amount of desquamation, the patient may require intensive care or placement in a burn unit.

This boy was immediately hospitalized and given IV fluids. The penicillin was stopped and an infectious disease consult was called. His oral lesions were managed with mouthwashes and glycerin swabs. His skin lesions were cleansed with saline and he was examined daily for secondary infections. An ophthalmologist was consulted due to the high risk of ocular sequelae.

Photo courtesy of Dan Stulberg, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana, C. Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Rash on hands

The family physician diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) on the hands, secondary to an outbreak of oral herpes, in this patient. The EM on the dorsum of the hand had target lesions with small, eroded centers. (Sometimes urticaria will have target-like lesions, but there will be no epidermal erosions.)

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction and is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases. EM most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 30 years.

There are no consistent laboratory findings with EM. The diagnosis is usually made based on clinical findings. The treatment is mainly supportive. Symptomatic relief may be provided with topical emollients, systemic antihistamines, and acetaminophen. These do not, however, alter the course of the illness. Recurrent outbreaks have been reported, and are thought to be associated with HSV infection.

If this patient were to get EM again with her HSV1, it would be reasonable to offer prophylactic acyclovir to prevent the HSV1 and the EM. Acyclovir has been used to control recurrent HSV-associated EM with some success.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Milana, C. Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) on the hands, secondary to an outbreak of oral herpes, in this patient. The EM on the dorsum of the hand had target lesions with small, eroded centers. (Sometimes urticaria will have target-like lesions, but there will be no epidermal erosions.)

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction and is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases. EM most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 30 years.

There are no consistent laboratory findings with EM. The diagnosis is usually made based on clinical findings. The treatment is mainly supportive. Symptomatic relief may be provided with topical emollients, systemic antihistamines, and acetaminophen. These do not, however, alter the course of the illness. Recurrent outbreaks have been reported, and are thought to be associated with HSV infection.

If this patient were to get EM again with her HSV1, it would be reasonable to offer prophylactic acyclovir to prevent the HSV1 and the EM. Acyclovir has been used to control recurrent HSV-associated EM with some success.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Milana, C. Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician diagnosed erythema multiforme (EM) on the hands, secondary to an outbreak of oral herpes, in this patient. The EM on the dorsum of the hand had target lesions with small, eroded centers. (Sometimes urticaria will have target-like lesions, but there will be no epidermal erosions.)

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction and is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases. EM most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 30 years.

There are no consistent laboratory findings with EM. The diagnosis is usually made based on clinical findings. The treatment is mainly supportive. Symptomatic relief may be provided with topical emollients, systemic antihistamines, and acetaminophen. These do not, however, alter the course of the illness. Recurrent outbreaks have been reported, and are thought to be associated with HSV infection.

If this patient were to get EM again with her HSV1, it would be reasonable to offer prophylactic acyclovir to prevent the HSV1 and the EM. Acyclovir has been used to control recurrent HSV-associated EM with some success.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Milana, C. Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Lesion on baby's arm

The target lesions on the arm and face led the physician to diagnose erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient. Each target lesion had a small vesicle in the center. The family physician told the parents to stop the antibiotic and recorded an allergy to sulfa in the child's electronic medical record.

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction and is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases. EM most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 30 years, with 20% of cases occurring in children and adolescents.

Classic lesions begin as red macules and expand centrifugally to become target-like papules or plaques with an erythematous outer border and central clearing (iris or bull’s eye lesions). Target lesions, though characteristic, are not necessary to make the diagnosis. The center of the lesion may have vesicles or erosions. Lesions can coalesce and form larger lesions up to 2 cm in diameter with centers that can become dusky purple to necrotic.

Unlike urticarial lesions, the lesions of EM will not fade; once they appear they will remain fixed in place. The lesions may be asymptomatic, although there may be a burning sensation or pruritus. The lesions typically resolve without any permanent sequelae within 2 weeks.

While this patient had no mucosal involvement, it is common for there to be mild involvement limited to one mucosal surface. Oral lesions are the most common, with the lips, gingiva, and palate most often affected.

In this case, once the patient discontinued the antibiotic, the EM cleared spontaneously in a week’s time with no scarring.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The target lesions on the arm and face led the physician to diagnose erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient. Each target lesion had a small vesicle in the center. The family physician told the parents to stop the antibiotic and recorded an allergy to sulfa in the child's electronic medical record.

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction and is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases. EM most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 30 years, with 20% of cases occurring in children and adolescents.

Classic lesions begin as red macules and expand centrifugally to become target-like papules or plaques with an erythematous outer border and central clearing (iris or bull’s eye lesions). Target lesions, though characteristic, are not necessary to make the diagnosis. The center of the lesion may have vesicles or erosions. Lesions can coalesce and form larger lesions up to 2 cm in diameter with centers that can become dusky purple to necrotic.

Unlike urticarial lesions, the lesions of EM will not fade; once they appear they will remain fixed in place. The lesions may be asymptomatic, although there may be a burning sensation or pruritus. The lesions typically resolve without any permanent sequelae within 2 weeks.

While this patient had no mucosal involvement, it is common for there to be mild involvement limited to one mucosal surface. Oral lesions are the most common, with the lips, gingiva, and palate most often affected.

In this case, once the patient discontinued the antibiotic, the EM cleared spontaneously in a week’s time with no scarring.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The target lesions on the arm and face led the physician to diagnose erythema multiforme (EM) in this patient. Each target lesion had a small vesicle in the center. The family physician told the parents to stop the antibiotic and recorded an allergy to sulfa in the child's electronic medical record.

EM is considered a hypersensitivity reaction and is often secondary to infections or medications. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVI and HSV2) are the most common causative agents and have been implicated in at least 60% of cases. EM most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 30 years, with 20% of cases occurring in children and adolescents.

Classic lesions begin as red macules and expand centrifugally to become target-like papules or plaques with an erythematous outer border and central clearing (iris or bull’s eye lesions). Target lesions, though characteristic, are not necessary to make the diagnosis. The center of the lesion may have vesicles or erosions. Lesions can coalesce and form larger lesions up to 2 cm in diameter with centers that can become dusky purple to necrotic.

Unlike urticarial lesions, the lesions of EM will not fade; once they appear they will remain fixed in place. The lesions may be asymptomatic, although there may be a burning sensation or pruritus. The lesions typically resolve without any permanent sequelae within 2 weeks.

While this patient had no mucosal involvement, it is common for there to be mild involvement limited to one mucosal surface. Oral lesions are the most common, with the lips, gingiva, and palate most often affected.

In this case, once the patient discontinued the antibiotic, the EM cleared spontaneously in a week’s time with no scarring.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Milana C, Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

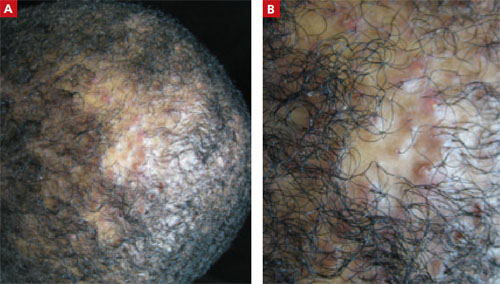

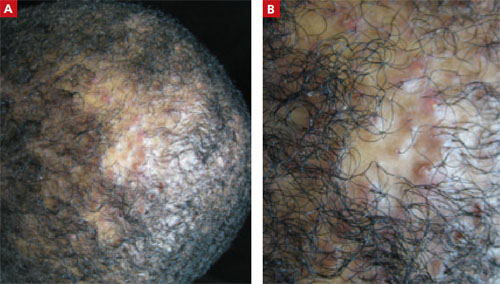

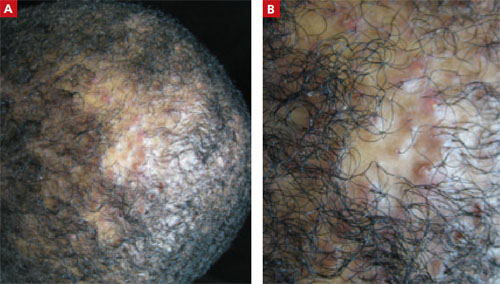

Alopecia with perifollicular papules and pustules

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 23-Year-Old African American Man sought care at our medical center because he had been losing hair over the vertex of his scalp for the past several years. He indicated that his father had early-onset male patterned alopecia. As a result, he considered his hair loss “genetic.” However, he described waxing and waning flares of painful pustules associated with occasional spontaneous bleeding and discharge of purulent material that occurred in the same area as the hair loss.

Physical examination revealed multiple perifollicular papules and pustules on the vertex of his scalp with interspersed patches of alopecia (FIGURE 1). There were no lesions elsewhere on his body and his past medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Alopecia with a painful twist

This 23-year-old patient said that he had spontaneous bleeding and discharge of purulent material in the area of his hair loss.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Folliculitis decalvans

Folliculitis decalvans (FD) is a highly inflammatory form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. The term scarring alopecia refers to the fact that the follicular epithelium has been replaced by connective tissue, ultimately resulting in permanent hair loss. This manifests clinically as patches of skin without terminal or vellus hairs, whereas a nonscarring alopecia would demonstrate preservation of the vellus hairs. Left untreated, advancing permanent hair loss ensues and may result in an end-stage pattern of tufted folliculitis or polytrichia, where interspersed dilated follicular openings house multiple hairs.

Affected areas commonly include the vertex and occipital scalp. Common symptoms include pain, itching, burning, and occasionally spontaneous bleeding or discharge of purulent material.1

FD generally occurs in young and middle-aged African Americans with a slight predominance in males. It accounts for 11% of all primary scarring alopecias.2,3 The etiology of this inflammatory process is not fully understood; however, scalp colonization with Staphylococcus aureus has been implicated as a contributing factor.4 Other reports suggest patients may have an altered host immune response and/or genetic predisposition for this condition.2,3

The differential includes various scarring, nonscarring alopecias

Since clinical findings of FD can range from relatively nonspecific mild disease at its onset to the end stage described above, a detailed patient history is needed. The following scarring and nonscarring alopecias should be considered in the diff erential diagnosis: dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), acne keloidalis nuchae, erosive pustular dermatosis, lichen planopilaris (LPP), inflammatory tinea capitis, and secondary syphilis.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is a distinctive, often debilitating disease commonly seen in young adult African American men. It is considered part of the follicular occlusion tetrad that also includes hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and pilonidal cysts. It presents as a scarring alopecia with firm scalp nodules that rapidly develop into boggy, fluctuant, oval to linear sinuses that may eventually discharge purulent material.

In contrast to FD, dissecting scalp cellulitis lesions interconnect via sinus tract formation so that pressure on one fluctuant area may result in purulent discharge from perfo-rations several centimeters away.5 Although both dissecting cellulitis and FD are considered primary neutrophilic scarring alopecias, the presence of true sinus tract formation can be a distinguishing finding.

CCCA is the most common form of scarring alopecia among African Americans and is particularly seen among African American women.5 It generally presents on the scalp vertex like FD, but it is much less inflamma-tory and typically causes only mild pruritus or tenderness of the involved areas.

Although numerous theories have been suggested, the etiology is unknown. The pathogenesis is thought to be associated with premature desquamation of the inner root sheath, which can be demonstrated on biopsy. Also seen histologically is lymphocytic perifollicular inflammation and polytrichia.6

Acne keloidalis nuchae is also a scarring alopecia. It is seen most commonly in African American men and presents as keloid-like papules and plaques with occasional pustules characteristically on the occipital scalp and posterior neck. In contrast to FD, acne keloidalis nuchae papules coalesce and may form firm, hairless, protuberant keloid-like plaques that may be painful and cosmetically disfiguring. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae is unknown.

Shaving or cutting tight curly hair too short and subsequently having the new hair curve back and penetrate the skin may be the precipitating event. Thus, a history of close shaving should make one suspect this diagnosis. Histologic analysis reveals a chronic, predominantly lymphocytic folliculitis with eventual follicular destruction.

Erosive pustular dermatosis is a rare disorder that primarily aff ects the elderly. It is characterized by a chronic amicrobial pustular dermatosis with extensive boggy, crusted, erosive plaques on the scalp resulting in scarring alopecia. Most cases have an onset after the age of 40. Therefore, age of onset may help diff erentiate between erosive pustular dermatosis and FD.

The cause of erosive pustular dermatosis is unknown. It is thought to be related to local trauma, such as chronic sun exposure, occurring months to years prior to the onset of lesions or as an autoimmune process.6 Histologic specimens show nonspecific changes including parakeratosis or hyperkeratotic scale with atrophy or erosion of the epidermis, while an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells is found in the dermis.

LPP is seen more commonly in women than men, and Caucasians are more often aff ected than African Americans. It presents with erythema, perifollicular scale, and scattered patches of scarring alopecia. Half of involved cases develop concomitant clinical features of lichen planus. When present, these characteristics may help distinguish it from FD and other scarring alopecias.6

The etiology of LPP is unknown, but is thought to be similar to the presumed cause of lichen planus: a T-cell?mediated autoimmune response that damages basal keratinocytes.5 Histologic findings include a band-like mononuclear cell infiltrate obscuring the interface between follicular epithelium and dermis at the superficial part of the follicle with occasional interfollicular epidermal changes consistent with lichen planus.

Inflammatory tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp that aff ects children and adults alike. Typically, it is easily distinguished from FD. However, severe cases may result in a highly inflammatory pustular eruption with alopecia—with or without a kerion—which can make diff erentiation difficult.

In contrast to FD, the alopecia associated with tinea capitis is usually nonscarring, although this depends on the extent and depth of infection. Also, tinea capitis may present with either discrete patches or involve the entire scalp, whereas FD is usually localized to the vertex or occiput (as noted earlier). Correct diagnosis can be accomplished by means of light microscopy and fungal culture.

Secondary syphilis is usually a sexually transmitted disease, but it can also be acquired perinatally. It often presents with a “moth-eaten” alopecia and should be considered when examining patients with patchy alopecia such as that seen in FD. These lesions manifest 3 to 10 weeks after the onset of primary syphilis. Early in its course, the condition is reversible, but if it becomes chronic, the condition will cause a scarring alopecia.

The presence of other stigmata, including a generalized pruritic papulosquamous eruption with involvement of the palms and soles, mucosal lesions ranging from superficial ulcers to large gray plaques, and condylomata lata, should help to diff erentiate syphilis from FD.

Serologic tests such as rapid plasma reagin and venereal disease research laboratory assays are often preferred for routine screening. If the index of suspicion is high, confirmatory testing with direct antibody as-says such as a microhemagglutination assay or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test is indicated.

Biopsy is needed for the diagnosis

Two scalp biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. Recommended guidelines for sampling the scalp include performance of 4-mm punch biopsies extending into the fat at 2 diff erent clinically active sites.7 One biopsy should be processed for standard horizontal sectioning, but the second biopsy should be bisected vertically, with half sent for histologic examination and the other half for tissue culture (fungal and bacterial). An additional subsequent biopsy for direct immunofluorescence may also be considered if the initial biopsies are nondiagnostic.

Bacterial and fungal cultures collected from an intact pustule on the scalp with a standard culture swab should also be undertaken with pustular disease. If scale is present, a potassium hydroxide examination can help establish the diagnosis of a fungal etiology.

Doxycycline, intralesional corticosteroids are the first line of Tx

Management of FD can be difficult, and long-term treatment is often necessary. You’ll need to explain to patients that their current hair loss is permanent and that the goal of treatment is to decrease inflammation and prevent further balding.

After initial bacterial cultures and sensitivities are obtained, primary treatment is aimed at eliminating S aureus colonization. Often, this requires oral antibiotic therapy, most commonly doxycycline 100 mg twice daily5(strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Topical antibiotics, however, may be used in mild cases; options include 2% mupirocin, 1% clindamycin, 1.5% fusidic acid, or 2% erythromycin applied twice daily1(SOR: C). In recalcitrant cases, a common treatment regimen includes oral rifampin 300 mg and clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 10 weeks4(SOR: C).

Adjunctive topical and intralesional corticosteroids may help reduce inflammation and provide symptomatic relief from itching, burning, and pain. Topical class I or II corticosteroids can be used twice daily, whereas intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (combined with topical and/or oral antibiotics) may be administered every 4 to 6 weeks, starting at a concentration of 10 mg/mL1(SOR: C). Oral corticosteroids should only be considered for highly active and rapidly progressive symptoms.

Dapsone may also be considered as a treatment option for FD due to its antimicrobial activity and anti-inflammatory action directed toward neutrophil metabolism. Relapse, however, is frequent after treatment withdrawal1(SOR: C).

Improvement, but anticipated chronicity

We prescribed oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for our patient, as well as clobetasol 0.05% topical solution, to be applied to the affected area in the morning and evening.

We told our patient that FD is a chronic relapsing disorder and that while we could not make the condition go away completely, we could control it. We advised the patient to follow up every 2 months for the next 6 months, then every 6 months to ensure there was no progression or need to change the treatment regimen.

The patient’s symptoms improved after the first 2 months. After weaning the patient off doxycycline over a 6-month period, we planned to transition the patient to topical clindamycin solution twice daily.

In some cases, the patient can be weaned off oral antibiotics once the condition is controlled, but for most patients, continuous systemic therapy is needed.

CORRESPONDENCE Oliver J. Wisco, Maj, USAF, MC, FS, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/ SG05D/Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244.

2. Douwes KE, Landthaler M, Szeimies RM. Simultaneous occur-rence of folliculitis decalvans capillitii in identical twins. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:195-197.

3. Chandrawansa PH, Giam YC. Folliculitis decalvans-a retrospective study in a tertiary referred center, over five years. Singapore Med J. 2003;44:84-87.

4. Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

5. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

6. Somani N, Bergfeld WF. Cicatricial alopecia: classification and histopathology. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:221-237.

7. Olsen EA, Bergfeld WF, Cotsarelis G, et al. Summary of North American Hair Research Society (NAHRS)-sponsored workshop on cicatricial alopecia, Duke University Medical Center, February 10 and 11, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:103-110.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 23-Year-Old African American Man sought care at our medical center because he had been losing hair over the vertex of his scalp for the past several years. He indicated that his father had early-onset male patterned alopecia. As a result, he considered his hair loss “genetic.” However, he described waxing and waning flares of painful pustules associated with occasional spontaneous bleeding and discharge of purulent material that occurred in the same area as the hair loss.

Physical examination revealed multiple perifollicular papules and pustules on the vertex of his scalp with interspersed patches of alopecia (FIGURE 1). There were no lesions elsewhere on his body and his past medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Alopecia with a painful twist

This 23-year-old patient said that he had spontaneous bleeding and discharge of purulent material in the area of his hair loss.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Folliculitis decalvans

Folliculitis decalvans (FD) is a highly inflammatory form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. The term scarring alopecia refers to the fact that the follicular epithelium has been replaced by connective tissue, ultimately resulting in permanent hair loss. This manifests clinically as patches of skin without terminal or vellus hairs, whereas a nonscarring alopecia would demonstrate preservation of the vellus hairs. Left untreated, advancing permanent hair loss ensues and may result in an end-stage pattern of tufted folliculitis or polytrichia, where interspersed dilated follicular openings house multiple hairs.

Affected areas commonly include the vertex and occipital scalp. Common symptoms include pain, itching, burning, and occasionally spontaneous bleeding or discharge of purulent material.1

FD generally occurs in young and middle-aged African Americans with a slight predominance in males. It accounts for 11% of all primary scarring alopecias.2,3 The etiology of this inflammatory process is not fully understood; however, scalp colonization with Staphylococcus aureus has been implicated as a contributing factor.4 Other reports suggest patients may have an altered host immune response and/or genetic predisposition for this condition.2,3

The differential includes various scarring, nonscarring alopecias

Since clinical findings of FD can range from relatively nonspecific mild disease at its onset to the end stage described above, a detailed patient history is needed. The following scarring and nonscarring alopecias should be considered in the diff erential diagnosis: dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), acne keloidalis nuchae, erosive pustular dermatosis, lichen planopilaris (LPP), inflammatory tinea capitis, and secondary syphilis.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is a distinctive, often debilitating disease commonly seen in young adult African American men. It is considered part of the follicular occlusion tetrad that also includes hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and pilonidal cysts. It presents as a scarring alopecia with firm scalp nodules that rapidly develop into boggy, fluctuant, oval to linear sinuses that may eventually discharge purulent material.

In contrast to FD, dissecting scalp cellulitis lesions interconnect via sinus tract formation so that pressure on one fluctuant area may result in purulent discharge from perfo-rations several centimeters away.5 Although both dissecting cellulitis and FD are considered primary neutrophilic scarring alopecias, the presence of true sinus tract formation can be a distinguishing finding.

CCCA is the most common form of scarring alopecia among African Americans and is particularly seen among African American women.5 It generally presents on the scalp vertex like FD, but it is much less inflamma-tory and typically causes only mild pruritus or tenderness of the involved areas.

Although numerous theories have been suggested, the etiology is unknown. The pathogenesis is thought to be associated with premature desquamation of the inner root sheath, which can be demonstrated on biopsy. Also seen histologically is lymphocytic perifollicular inflammation and polytrichia.6

Acne keloidalis nuchae is also a scarring alopecia. It is seen most commonly in African American men and presents as keloid-like papules and plaques with occasional pustules characteristically on the occipital scalp and posterior neck. In contrast to FD, acne keloidalis nuchae papules coalesce and may form firm, hairless, protuberant keloid-like plaques that may be painful and cosmetically disfiguring. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae is unknown.

Shaving or cutting tight curly hair too short and subsequently having the new hair curve back and penetrate the skin may be the precipitating event. Thus, a history of close shaving should make one suspect this diagnosis. Histologic analysis reveals a chronic, predominantly lymphocytic folliculitis with eventual follicular destruction.

Erosive pustular dermatosis is a rare disorder that primarily aff ects the elderly. It is characterized by a chronic amicrobial pustular dermatosis with extensive boggy, crusted, erosive plaques on the scalp resulting in scarring alopecia. Most cases have an onset after the age of 40. Therefore, age of onset may help diff erentiate between erosive pustular dermatosis and FD.

The cause of erosive pustular dermatosis is unknown. It is thought to be related to local trauma, such as chronic sun exposure, occurring months to years prior to the onset of lesions or as an autoimmune process.6 Histologic specimens show nonspecific changes including parakeratosis or hyperkeratotic scale with atrophy or erosion of the epidermis, while an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells is found in the dermis.

LPP is seen more commonly in women than men, and Caucasians are more often aff ected than African Americans. It presents with erythema, perifollicular scale, and scattered patches of scarring alopecia. Half of involved cases develop concomitant clinical features of lichen planus. When present, these characteristics may help distinguish it from FD and other scarring alopecias.6

The etiology of LPP is unknown, but is thought to be similar to the presumed cause of lichen planus: a T-cell?mediated autoimmune response that damages basal keratinocytes.5 Histologic findings include a band-like mononuclear cell infiltrate obscuring the interface between follicular epithelium and dermis at the superficial part of the follicle with occasional interfollicular epidermal changes consistent with lichen planus.

Inflammatory tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp that aff ects children and adults alike. Typically, it is easily distinguished from FD. However, severe cases may result in a highly inflammatory pustular eruption with alopecia—with or without a kerion—which can make diff erentiation difficult.

In contrast to FD, the alopecia associated with tinea capitis is usually nonscarring, although this depends on the extent and depth of infection. Also, tinea capitis may present with either discrete patches or involve the entire scalp, whereas FD is usually localized to the vertex or occiput (as noted earlier). Correct diagnosis can be accomplished by means of light microscopy and fungal culture.

Secondary syphilis is usually a sexually transmitted disease, but it can also be acquired perinatally. It often presents with a “moth-eaten” alopecia and should be considered when examining patients with patchy alopecia such as that seen in FD. These lesions manifest 3 to 10 weeks after the onset of primary syphilis. Early in its course, the condition is reversible, but if it becomes chronic, the condition will cause a scarring alopecia.

The presence of other stigmata, including a generalized pruritic papulosquamous eruption with involvement of the palms and soles, mucosal lesions ranging from superficial ulcers to large gray plaques, and condylomata lata, should help to diff erentiate syphilis from FD.

Serologic tests such as rapid plasma reagin and venereal disease research laboratory assays are often preferred for routine screening. If the index of suspicion is high, confirmatory testing with direct antibody as-says such as a microhemagglutination assay or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test is indicated.

Biopsy is needed for the diagnosis

Two scalp biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. Recommended guidelines for sampling the scalp include performance of 4-mm punch biopsies extending into the fat at 2 diff erent clinically active sites.7 One biopsy should be processed for standard horizontal sectioning, but the second biopsy should be bisected vertically, with half sent for histologic examination and the other half for tissue culture (fungal and bacterial). An additional subsequent biopsy for direct immunofluorescence may also be considered if the initial biopsies are nondiagnostic.

Bacterial and fungal cultures collected from an intact pustule on the scalp with a standard culture swab should also be undertaken with pustular disease. If scale is present, a potassium hydroxide examination can help establish the diagnosis of a fungal etiology.

Doxycycline, intralesional corticosteroids are the first line of Tx

Management of FD can be difficult, and long-term treatment is often necessary. You’ll need to explain to patients that their current hair loss is permanent and that the goal of treatment is to decrease inflammation and prevent further balding.

After initial bacterial cultures and sensitivities are obtained, primary treatment is aimed at eliminating S aureus colonization. Often, this requires oral antibiotic therapy, most commonly doxycycline 100 mg twice daily5(strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Topical antibiotics, however, may be used in mild cases; options include 2% mupirocin, 1% clindamycin, 1.5% fusidic acid, or 2% erythromycin applied twice daily1(SOR: C). In recalcitrant cases, a common treatment regimen includes oral rifampin 300 mg and clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 10 weeks4(SOR: C).

Adjunctive topical and intralesional corticosteroids may help reduce inflammation and provide symptomatic relief from itching, burning, and pain. Topical class I or II corticosteroids can be used twice daily, whereas intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (combined with topical and/or oral antibiotics) may be administered every 4 to 6 weeks, starting at a concentration of 10 mg/mL1(SOR: C). Oral corticosteroids should only be considered for highly active and rapidly progressive symptoms.

Dapsone may also be considered as a treatment option for FD due to its antimicrobial activity and anti-inflammatory action directed toward neutrophil metabolism. Relapse, however, is frequent after treatment withdrawal1(SOR: C).

Improvement, but anticipated chronicity

We prescribed oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for our patient, as well as clobetasol 0.05% topical solution, to be applied to the affected area in the morning and evening.

We told our patient that FD is a chronic relapsing disorder and that while we could not make the condition go away completely, we could control it. We advised the patient to follow up every 2 months for the next 6 months, then every 6 months to ensure there was no progression or need to change the treatment regimen.

The patient’s symptoms improved after the first 2 months. After weaning the patient off doxycycline over a 6-month period, we planned to transition the patient to topical clindamycin solution twice daily.

In some cases, the patient can be weaned off oral antibiotics once the condition is controlled, but for most patients, continuous systemic therapy is needed.

CORRESPONDENCE Oliver J. Wisco, Maj, USAF, MC, FS, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/ SG05D/Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 23-Year-Old African American Man sought care at our medical center because he had been losing hair over the vertex of his scalp for the past several years. He indicated that his father had early-onset male patterned alopecia. As a result, he considered his hair loss “genetic.” However, he described waxing and waning flares of painful pustules associated with occasional spontaneous bleeding and discharge of purulent material that occurred in the same area as the hair loss.

Physical examination revealed multiple perifollicular papules and pustules on the vertex of his scalp with interspersed patches of alopecia (FIGURE 1). There were no lesions elsewhere on his body and his past medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Alopecia with a painful twist

This 23-year-old patient said that he had spontaneous bleeding and discharge of purulent material in the area of his hair loss.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Folliculitis decalvans

Folliculitis decalvans (FD) is a highly inflammatory form of scarring alopecia characterized by inflammatory perifollicular papules and pustules. The term scarring alopecia refers to the fact that the follicular epithelium has been replaced by connective tissue, ultimately resulting in permanent hair loss. This manifests clinically as patches of skin without terminal or vellus hairs, whereas a nonscarring alopecia would demonstrate preservation of the vellus hairs. Left untreated, advancing permanent hair loss ensues and may result in an end-stage pattern of tufted folliculitis or polytrichia, where interspersed dilated follicular openings house multiple hairs.

Affected areas commonly include the vertex and occipital scalp. Common symptoms include pain, itching, burning, and occasionally spontaneous bleeding or discharge of purulent material.1

FD generally occurs in young and middle-aged African Americans with a slight predominance in males. It accounts for 11% of all primary scarring alopecias.2,3 The etiology of this inflammatory process is not fully understood; however, scalp colonization with Staphylococcus aureus has been implicated as a contributing factor.4 Other reports suggest patients may have an altered host immune response and/or genetic predisposition for this condition.2,3

The differential includes various scarring, nonscarring alopecias

Since clinical findings of FD can range from relatively nonspecific mild disease at its onset to the end stage described above, a detailed patient history is needed. The following scarring and nonscarring alopecias should be considered in the diff erential diagnosis: dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), acne keloidalis nuchae, erosive pustular dermatosis, lichen planopilaris (LPP), inflammatory tinea capitis, and secondary syphilis.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is a distinctive, often debilitating disease commonly seen in young adult African American men. It is considered part of the follicular occlusion tetrad that also includes hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and pilonidal cysts. It presents as a scarring alopecia with firm scalp nodules that rapidly develop into boggy, fluctuant, oval to linear sinuses that may eventually discharge purulent material.

In contrast to FD, dissecting scalp cellulitis lesions interconnect via sinus tract formation so that pressure on one fluctuant area may result in purulent discharge from perfo-rations several centimeters away.5 Although both dissecting cellulitis and FD are considered primary neutrophilic scarring alopecias, the presence of true sinus tract formation can be a distinguishing finding.

CCCA is the most common form of scarring alopecia among African Americans and is particularly seen among African American women.5 It generally presents on the scalp vertex like FD, but it is much less inflamma-tory and typically causes only mild pruritus or tenderness of the involved areas.

Although numerous theories have been suggested, the etiology is unknown. The pathogenesis is thought to be associated with premature desquamation of the inner root sheath, which can be demonstrated on biopsy. Also seen histologically is lymphocytic perifollicular inflammation and polytrichia.6

Acne keloidalis nuchae is also a scarring alopecia. It is seen most commonly in African American men and presents as keloid-like papules and plaques with occasional pustules characteristically on the occipital scalp and posterior neck. In contrast to FD, acne keloidalis nuchae papules coalesce and may form firm, hairless, protuberant keloid-like plaques that may be painful and cosmetically disfiguring. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae is unknown.

Shaving or cutting tight curly hair too short and subsequently having the new hair curve back and penetrate the skin may be the precipitating event. Thus, a history of close shaving should make one suspect this diagnosis. Histologic analysis reveals a chronic, predominantly lymphocytic folliculitis with eventual follicular destruction.

Erosive pustular dermatosis is a rare disorder that primarily aff ects the elderly. It is characterized by a chronic amicrobial pustular dermatosis with extensive boggy, crusted, erosive plaques on the scalp resulting in scarring alopecia. Most cases have an onset after the age of 40. Therefore, age of onset may help diff erentiate between erosive pustular dermatosis and FD.

The cause of erosive pustular dermatosis is unknown. It is thought to be related to local trauma, such as chronic sun exposure, occurring months to years prior to the onset of lesions or as an autoimmune process.6 Histologic specimens show nonspecific changes including parakeratosis or hyperkeratotic scale with atrophy or erosion of the epidermis, while an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells is found in the dermis.

LPP is seen more commonly in women than men, and Caucasians are more often aff ected than African Americans. It presents with erythema, perifollicular scale, and scattered patches of scarring alopecia. Half of involved cases develop concomitant clinical features of lichen planus. When present, these characteristics may help distinguish it from FD and other scarring alopecias.6

The etiology of LPP is unknown, but is thought to be similar to the presumed cause of lichen planus: a T-cell?mediated autoimmune response that damages basal keratinocytes.5 Histologic findings include a band-like mononuclear cell infiltrate obscuring the interface between follicular epithelium and dermis at the superficial part of the follicle with occasional interfollicular epidermal changes consistent with lichen planus.

Inflammatory tinea capitis is a common dermatophyte infection of the scalp that aff ects children and adults alike. Typically, it is easily distinguished from FD. However, severe cases may result in a highly inflammatory pustular eruption with alopecia—with or without a kerion—which can make diff erentiation difficult.

In contrast to FD, the alopecia associated with tinea capitis is usually nonscarring, although this depends on the extent and depth of infection. Also, tinea capitis may present with either discrete patches or involve the entire scalp, whereas FD is usually localized to the vertex or occiput (as noted earlier). Correct diagnosis can be accomplished by means of light microscopy and fungal culture.

Secondary syphilis is usually a sexually transmitted disease, but it can also be acquired perinatally. It often presents with a “moth-eaten” alopecia and should be considered when examining patients with patchy alopecia such as that seen in FD. These lesions manifest 3 to 10 weeks after the onset of primary syphilis. Early in its course, the condition is reversible, but if it becomes chronic, the condition will cause a scarring alopecia.

The presence of other stigmata, including a generalized pruritic papulosquamous eruption with involvement of the palms and soles, mucosal lesions ranging from superficial ulcers to large gray plaques, and condylomata lata, should help to diff erentiate syphilis from FD.

Serologic tests such as rapid plasma reagin and venereal disease research laboratory assays are often preferred for routine screening. If the index of suspicion is high, confirmatory testing with direct antibody as-says such as a microhemagglutination assay or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test is indicated.

Biopsy is needed for the diagnosis

Two scalp biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. Recommended guidelines for sampling the scalp include performance of 4-mm punch biopsies extending into the fat at 2 diff erent clinically active sites.7 One biopsy should be processed for standard horizontal sectioning, but the second biopsy should be bisected vertically, with half sent for histologic examination and the other half for tissue culture (fungal and bacterial). An additional subsequent biopsy for direct immunofluorescence may also be considered if the initial biopsies are nondiagnostic.

Bacterial and fungal cultures collected from an intact pustule on the scalp with a standard culture swab should also be undertaken with pustular disease. If scale is present, a potassium hydroxide examination can help establish the diagnosis of a fungal etiology.

Doxycycline, intralesional corticosteroids are the first line of Tx

Management of FD can be difficult, and long-term treatment is often necessary. You’ll need to explain to patients that their current hair loss is permanent and that the goal of treatment is to decrease inflammation and prevent further balding.

After initial bacterial cultures and sensitivities are obtained, primary treatment is aimed at eliminating S aureus colonization. Often, this requires oral antibiotic therapy, most commonly doxycycline 100 mg twice daily5(strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). Topical antibiotics, however, may be used in mild cases; options include 2% mupirocin, 1% clindamycin, 1.5% fusidic acid, or 2% erythromycin applied twice daily1(SOR: C). In recalcitrant cases, a common treatment regimen includes oral rifampin 300 mg and clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 10 weeks4(SOR: C).

Adjunctive topical and intralesional corticosteroids may help reduce inflammation and provide symptomatic relief from itching, burning, and pain. Topical class I or II corticosteroids can be used twice daily, whereas intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (combined with topical and/or oral antibiotics) may be administered every 4 to 6 weeks, starting at a concentration of 10 mg/mL1(SOR: C). Oral corticosteroids should only be considered for highly active and rapidly progressive symptoms.

Dapsone may also be considered as a treatment option for FD due to its antimicrobial activity and anti-inflammatory action directed toward neutrophil metabolism. Relapse, however, is frequent after treatment withdrawal1(SOR: C).

Improvement, but anticipated chronicity

We prescribed oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for our patient, as well as clobetasol 0.05% topical solution, to be applied to the affected area in the morning and evening.

We told our patient that FD is a chronic relapsing disorder and that while we could not make the condition go away completely, we could control it. We advised the patient to follow up every 2 months for the next 6 months, then every 6 months to ensure there was no progression or need to change the treatment regimen.

The patient’s symptoms improved after the first 2 months. After weaning the patient off doxycycline over a 6-month period, we planned to transition the patient to topical clindamycin solution twice daily.

In some cases, the patient can be weaned off oral antibiotics once the condition is controlled, but for most patients, continuous systemic therapy is needed.

CORRESPONDENCE Oliver J. Wisco, Maj, USAF, MC, FS, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/ SG05D/Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244.

2. Douwes KE, Landthaler M, Szeimies RM. Simultaneous occur-rence of folliculitis decalvans capillitii in identical twins. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:195-197.

3. Chandrawansa PH, Giam YC. Folliculitis decalvans-a retrospective study in a tertiary referred center, over five years. Singapore Med J. 2003;44:84-87.

4. Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

5. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

6. Somani N, Bergfeld WF. Cicatricial alopecia: classification and histopathology. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:221-237.

7. Olsen EA, Bergfeld WF, Cotsarelis G, et al. Summary of North American Hair Research Society (NAHRS)-sponsored workshop on cicatricial alopecia, Duke University Medical Center, February 10 and 11, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:103-110.

1. Otberg N, Kang H, Alzolibani AA, et al. Folliculitis decalvans. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:238-244.

2. Douwes KE, Landthaler M, Szeimies RM. Simultaneous occur-rence of folliculitis decalvans capillitii in identical twins. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:195-197.

3. Chandrawansa PH, Giam YC. Folliculitis decalvans-a retrospective study in a tertiary referred center, over five years. Singapore Med J. 2003;44:84-87.

4. Powell JJ, Dawber RP, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:328-333.

5. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

6. Somani N, Bergfeld WF. Cicatricial alopecia: classification and histopathology. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:221-237.

7. Olsen EA, Bergfeld WF, Cotsarelis G, et al. Summary of North American Hair Research Society (NAHRS)-sponsored workshop on cicatricial alopecia, Duke University Medical Center, February 10 and 11, 2001. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:103-110.

Skin thickening on shoulder

The pathology from a 4-mm punch biopsy of the involved area revealed mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). CTCL is a malignant lymphoma of helper T-cells that usually remains confined to skin and lymph nodes. The most common initial presentation involves scaly patches or plaques with a persistent rash that is often pruritic and usually erythematous. Patches may evolve to generalized, infiltrated plaques or to ulcerated, exophytic tumors. Lesions typically develop on non-sun-exposed areas.

Treatment of CTCL should be provided by a dermatologist and/or hematologist/oncologist experienced with this condition. For disease localized to the skin, treatment may begin with emollients, antipruritics, and topical high-potency steroids. Topical retinoids and topical chemotherapy are treatment alternatives for localized disease and effective adjuvants in generalized disease. Psoralen-enhanced ultraviolet light type A (PUVA) and narrowband ultraviolet B light have proven effective in early MF. More advanced disease with erythroderma or lymph node involvement should be treated with systemic chemotherapy or photophoresis. This patient was sent to a dermatologist and oncologist for further evaluation and treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Nayar A, Usatine R. Mycosis fungoides. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:745-749.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The pathology from a 4-mm punch biopsy of the involved area revealed mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). CTCL is a malignant lymphoma of helper T-cells that usually remains confined to skin and lymph nodes. The most common initial presentation involves scaly patches or plaques with a persistent rash that is often pruritic and usually erythematous. Patches may evolve to generalized, infiltrated plaques or to ulcerated, exophytic tumors. Lesions typically develop on non-sun-exposed areas.

Treatment of CTCL should be provided by a dermatologist and/or hematologist/oncologist experienced with this condition. For disease localized to the skin, treatment may begin with emollients, antipruritics, and topical high-potency steroids. Topical retinoids and topical chemotherapy are treatment alternatives for localized disease and effective adjuvants in generalized disease. Psoralen-enhanced ultraviolet light type A (PUVA) and narrowband ultraviolet B light have proven effective in early MF. More advanced disease with erythroderma or lymph node involvement should be treated with systemic chemotherapy or photophoresis. This patient was sent to a dermatologist and oncologist for further evaluation and treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Nayar A, Usatine R. Mycosis fungoides. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:745-749.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The pathology from a 4-mm punch biopsy of the involved area revealed mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). CTCL is a malignant lymphoma of helper T-cells that usually remains confined to skin and lymph nodes. The most common initial presentation involves scaly patches or plaques with a persistent rash that is often pruritic and usually erythematous. Patches may evolve to generalized, infiltrated plaques or to ulcerated, exophytic tumors. Lesions typically develop on non-sun-exposed areas.

Treatment of CTCL should be provided by a dermatologist and/or hematologist/oncologist experienced with this condition. For disease localized to the skin, treatment may begin with emollients, antipruritics, and topical high-potency steroids. Topical retinoids and topical chemotherapy are treatment alternatives for localized disease and effective adjuvants in generalized disease. Psoralen-enhanced ultraviolet light type A (PUVA) and narrowband ultraviolet B light have proven effective in early MF. More advanced disease with erythroderma or lymph node involvement should be treated with systemic chemotherapy or photophoresis. This patient was sent to a dermatologist and oncologist for further evaluation and treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Nayar A, Usatine R. Mycosis fungoides. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:745-749.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Hypopigmented rash

|

|

The pathology from a 4-mm punch biopsy of a hypopigmented macule on the patient’s thigh revealed “cerebriform” lymphocytes at the dermal-epidermal junction characteristic of mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

CTCL is a rare disease with 1000 new cases per year in the United States, comprising about 0.5% of all nonHodgkin’s lymphoma cases. MF is the most common form of CTCL. It is more common in African Americans than white individuals with an incidence ratio of 6:1. It is more common in men than women at a ratio of 2:1.

CTCL is a malignant lymphoma of helper T-cells that usually remains confined to skin and lymph nodes. MF is named for the mushroom-like skin tumors seen in severe cases. Metastasis to the liver, spleen, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, bone marrow, and central nervous system may occur.

The most common initial presentation involves scaly patches or plaques with a persistent rash that is often pruritic and usually erythematous. Patches may evolve to generalized, infiltrated plaques or to ulcerated, exophytic tumors.

Hypo- or hyperpigmented lesions, petechiae, poikiloderma (skin atrophy with telangiectasia), and alopecia (with or without mucinosis) are other findings. Lesions typically develop on non-sun-exposed areas initially, such as the trunk below the waistline, flanks, breasts, inner thighs and arms (FIGURES 1 and 2), and the periaxillary areas.

The patient was referred to a hematologist/oncologist. She was started on narrowband ultraviolet B treatment.

Adapted from:

Mahan RD, Usatine RP. Hurricane Katrina evacuee develops a persistent rash. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:454-457.

|

|

The pathology from a 4-mm punch biopsy of a hypopigmented macule on the patient’s thigh revealed “cerebriform” lymphocytes at the dermal-epidermal junction characteristic of mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

CTCL is a rare disease with 1000 new cases per year in the United States, comprising about 0.5% of all nonHodgkin’s lymphoma cases. MF is the most common form of CTCL. It is more common in African Americans than white individuals with an incidence ratio of 6:1. It is more common in men than women at a ratio of 2:1.

CTCL is a malignant lymphoma of helper T-cells that usually remains confined to skin and lymph nodes. MF is named for the mushroom-like skin tumors seen in severe cases. Metastasis to the liver, spleen, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, bone marrow, and central nervous system may occur.

The most common initial presentation involves scaly patches or plaques with a persistent rash that is often pruritic and usually erythematous. Patches may evolve to generalized, infiltrated plaques or to ulcerated, exophytic tumors.

Hypo- or hyperpigmented lesions, petechiae, poikiloderma (skin atrophy with telangiectasia), and alopecia (with or without mucinosis) are other findings. Lesions typically develop on non-sun-exposed areas initially, such as the trunk below the waistline, flanks, breasts, inner thighs and arms (FIGURES 1 and 2), and the periaxillary areas.

The patient was referred to a hematologist/oncologist. She was started on narrowband ultraviolet B treatment.

Adapted from:

Mahan RD, Usatine RP. Hurricane Katrina evacuee develops a persistent rash. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:454-457.

|

|

The pathology from a 4-mm punch biopsy of a hypopigmented macule on the patient’s thigh revealed “cerebriform” lymphocytes at the dermal-epidermal junction characteristic of mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

CTCL is a rare disease with 1000 new cases per year in the United States, comprising about 0.5% of all nonHodgkin’s lymphoma cases. MF is the most common form of CTCL. It is more common in African Americans than white individuals with an incidence ratio of 6:1. It is more common in men than women at a ratio of 2:1.

CTCL is a malignant lymphoma of helper T-cells that usually remains confined to skin and lymph nodes. MF is named for the mushroom-like skin tumors seen in severe cases. Metastasis to the liver, spleen, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, bone marrow, and central nervous system may occur.

The most common initial presentation involves scaly patches or plaques with a persistent rash that is often pruritic and usually erythematous. Patches may evolve to generalized, infiltrated plaques or to ulcerated, exophytic tumors.

Hypo- or hyperpigmented lesions, petechiae, poikiloderma (skin atrophy with telangiectasia), and alopecia (with or without mucinosis) are other findings. Lesions typically develop on non-sun-exposed areas initially, such as the trunk below the waistline, flanks, breasts, inner thighs and arms (FIGURES 1 and 2), and the periaxillary areas.

The patient was referred to a hematologist/oncologist. She was started on narrowband ultraviolet B treatment.

Adapted from:

Mahan RD, Usatine RP. Hurricane Katrina evacuee develops a persistent rash. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:454-457.

Plaques on back

The diagnosis

The family physician performed a 4-mm punch biopsy and the pathology showed cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that involves multiple organ systems; the etiology is unknown. Cutaneous manifestations occur in about 25% of systemic sarcoidosis patients.

This patient had a less common presentation of sarcoidosis than last week’s case of sarcoidosis on the face (lupus pernio). Other less common types of cutaneous sarcoidosis can be maculopapular, nodular, or infiltrative within existing scars or tattoos. Erythema nodosum is a common nonspecific finding in sarcoidosis. Other less common nonspecific lesions reported in sarcoidosis include erythema multiforme, calcinosis cutis, and lymphedema. Nail changes can include clubbing, onycholysis, subungual keratosis, and dystrophy.

Chest radiographic involvement is seen in almost 90% of patients and is used to stage the disease. Stage I disease shows bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL). Stage II disease shows BHL plus pulmonary infiltrates. Stage III disease shows pulmonary infiltrates without BHL. Stage IV disease shows pulmonary fibrosis.

This patient had stage II disease and the physician referred him for pulmonary function testing and to a pulmonologist. The physician prescribed high-potency topical steroids for the cutaneous lesions. If the pulmonary evaluation revealed significant pulmonary involvement, treatment options would include oral prednisone and weekly methotrexate.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:740-744.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The diagnosis

The family physician performed a 4-mm punch biopsy and the pathology showed cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that involves multiple organ systems; the etiology is unknown. Cutaneous manifestations occur in about 25% of systemic sarcoidosis patients.

This patient had a less common presentation of sarcoidosis than last week’s case of sarcoidosis on the face (lupus pernio). Other less common types of cutaneous sarcoidosis can be maculopapular, nodular, or infiltrative within existing scars or tattoos. Erythema nodosum is a common nonspecific finding in sarcoidosis. Other less common nonspecific lesions reported in sarcoidosis include erythema multiforme, calcinosis cutis, and lymphedema. Nail changes can include clubbing, onycholysis, subungual keratosis, and dystrophy.

Chest radiographic involvement is seen in almost 90% of patients and is used to stage the disease. Stage I disease shows bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL). Stage II disease shows BHL plus pulmonary infiltrates. Stage III disease shows pulmonary infiltrates without BHL. Stage IV disease shows pulmonary fibrosis.

This patient had stage II disease and the physician referred him for pulmonary function testing and to a pulmonologist. The physician prescribed high-potency topical steroids for the cutaneous lesions. If the pulmonary evaluation revealed significant pulmonary involvement, treatment options would include oral prednisone and weekly methotrexate.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:740-744.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The diagnosis

The family physician performed a 4-mm punch biopsy and the pathology showed cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that involves multiple organ systems; the etiology is unknown. Cutaneous manifestations occur in about 25% of systemic sarcoidosis patients.

This patient had a less common presentation of sarcoidosis than last week’s case of sarcoidosis on the face (lupus pernio). Other less common types of cutaneous sarcoidosis can be maculopapular, nodular, or infiltrative within existing scars or tattoos. Erythema nodosum is a common nonspecific finding in sarcoidosis. Other less common nonspecific lesions reported in sarcoidosis include erythema multiforme, calcinosis cutis, and lymphedema. Nail changes can include clubbing, onycholysis, subungual keratosis, and dystrophy.

Chest radiographic involvement is seen in almost 90% of patients and is used to stage the disease. Stage I disease shows bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL). Stage II disease shows BHL plus pulmonary infiltrates. Stage III disease shows pulmonary infiltrates without BHL. Stage IV disease shows pulmonary fibrosis.

This patient had stage II disease and the physician referred him for pulmonary function testing and to a pulmonologist. The physician prescribed high-potency topical steroids for the cutaneous lesions. If the pulmonary evaluation revealed significant pulmonary involvement, treatment options would include oral prednisone and weekly methotrexate.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:740-744.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Swelling on nose

The physician made the presumptive diagnosis of sarcoidosis. The involvement of the rim of the nasal ala is especially common in cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that involves multiple organ systems; the etiology is unknown. Cutaneous manifestations occur in about 25% of systemic sarcoidosis patients.

This patient had lupus pernio in which the sarcoid granulomas involve the face (as one might see in lupus erythematosus). Other less common types of cutaneous sarcoidosis can be maculopapular, nodular, or infiltrative within existing scars or tattoos. Erythema nodosum is a common nonspecific finding in sarcoidosis. Other less common nonspecific lesions reported in sarcoidosis include erythema multiforme, calcinosis cutis, and lymphedema. Nail changes can include clubbing, onycholysis, subungual keratosis, and dystrophy.

In this case, the diagnosis was confirmed with a punch biopsy of a lesion on the upper lip (above the vermillion border), as a biopsy of the nasal ala is more likely to leave undesirable scarring. Chest radiographic involvement is seen in almost 90% of patients and is used to stage the disease.

Stage I disease shows bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL). Stage II disease shows BHL plus pulmonary infiltrates. Stage III disease shows pulmonary infiltrates without BHL. Stage IV disease shows pulmonary fibrosis. This patient had stage I disease.

Cutaneous involvement of sarcoidosis is typically not life threatening; treatment is aimed at minimizing disfigurement. In this case, the lesions were painful and treatment involved a mid-potency topical steroid.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sarabi K, Khachemoune A. Sarcoidosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:740-744.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The physician made the presumptive diagnosis of sarcoidosis. The involvement of the rim of the nasal ala is especially common in cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that involves multiple organ systems; the etiology is unknown. Cutaneous manifestations occur in about 25% of systemic sarcoidosis patients.

This patient had lupus pernio in which the sarcoid granulomas involve the face (as one might see in lupus erythematosus). Other less common types of cutaneous sarcoidosis can be maculopapular, nodular, or infiltrative within existing scars or tattoos. Erythema nodosum is a common nonspecific finding in sarcoidosis. Other less common nonspecific lesions reported in sarcoidosis include erythema multiforme, calcinosis cutis, and lymphedema. Nail changes can include clubbing, onycholysis, subungual keratosis, and dystrophy.

In this case, the diagnosis was confirmed with a punch biopsy of a lesion on the upper lip (above the vermillion border), as a biopsy of the nasal ala is more likely to leave undesirable scarring. Chest radiographic involvement is seen in almost 90% of patients and is used to stage the disease.