User login

Ulcer on leg

The family physician made the presumptive diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum. At least 50% of cases are associated with systemic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic malignancy, and arthritis. It’s estimated that 30% of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum experience pathergy (initiation at the site of trauma or injury). This patient’s history was consistent with pathergy.

Typically pyoderma gangrenosum presents with a deep, painful ulcer. The ulcer has a well-defined border, which is usually violet or blue. The ulcer edge is often undermined and the surrounding skin is erythematous and indurated. Pyoderma gangrenosum usually starts as small papules that coalesce; the central area then undergoes necrosis to form a single ulcer. The lesions are painful and the pain can be severe. Patients may have malaise, arthralgia, and myalgia. Pyoderma gangrenosum is most commonly seen on the legs, but can occur on any skin surface (including the genitalia) and around a stoma.

The physician performed a punch biopsy including the active ulcer and the border to rule out other causes of ulcerative skin lesions. The biopsy showed a neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Treatment options include:

- topical medications, such as potent steroid ointments, tacrolimus ointment, and silver sulfadiazine

- intralesional injections with corticosteroids

- systemic treatment with oral corticosteroids

- treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, oral tacrolimus, dapsone, azathioprine, or infliximab (each used successfully, according to published case reports).

Surgical debridement is contraindicated since pathergy will make the lesions worse.

In this case, the patient chose topical clobetasol ointment. She was lost to follow-up.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Flowers D, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:735-739.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

* http://www.mhprofessional.com/product.php?isbn=0071474641

The family physician made the presumptive diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum. At least 50% of cases are associated with systemic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic malignancy, and arthritis. It’s estimated that 30% of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum experience pathergy (initiation at the site of trauma or injury). This patient’s history was consistent with pathergy.

Typically pyoderma gangrenosum presents with a deep, painful ulcer. The ulcer has a well-defined border, which is usually violet or blue. The ulcer edge is often undermined and the surrounding skin is erythematous and indurated. Pyoderma gangrenosum usually starts as small papules that coalesce; the central area then undergoes necrosis to form a single ulcer. The lesions are painful and the pain can be severe. Patients may have malaise, arthralgia, and myalgia. Pyoderma gangrenosum is most commonly seen on the legs, but can occur on any skin surface (including the genitalia) and around a stoma.

The physician performed a punch biopsy including the active ulcer and the border to rule out other causes of ulcerative skin lesions. The biopsy showed a neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Treatment options include:

- topical medications, such as potent steroid ointments, tacrolimus ointment, and silver sulfadiazine

- intralesional injections with corticosteroids

- systemic treatment with oral corticosteroids

- treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, oral tacrolimus, dapsone, azathioprine, or infliximab (each used successfully, according to published case reports).

Surgical debridement is contraindicated since pathergy will make the lesions worse.

In this case, the patient chose topical clobetasol ointment. She was lost to follow-up.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Flowers D, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:735-739.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

* http://www.mhprofessional.com/product.php?isbn=0071474641

The family physician made the presumptive diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum. At least 50% of cases are associated with systemic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic malignancy, and arthritis. It’s estimated that 30% of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum experience pathergy (initiation at the site of trauma or injury). This patient’s history was consistent with pathergy.

Typically pyoderma gangrenosum presents with a deep, painful ulcer. The ulcer has a well-defined border, which is usually violet or blue. The ulcer edge is often undermined and the surrounding skin is erythematous and indurated. Pyoderma gangrenosum usually starts as small papules that coalesce; the central area then undergoes necrosis to form a single ulcer. The lesions are painful and the pain can be severe. Patients may have malaise, arthralgia, and myalgia. Pyoderma gangrenosum is most commonly seen on the legs, but can occur on any skin surface (including the genitalia) and around a stoma.

The physician performed a punch biopsy including the active ulcer and the border to rule out other causes of ulcerative skin lesions. The biopsy showed a neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Treatment options include:

- topical medications, such as potent steroid ointments, tacrolimus ointment, and silver sulfadiazine

- intralesional injections with corticosteroids

- systemic treatment with oral corticosteroids

- treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, oral tacrolimus, dapsone, azathioprine, or infliximab (each used successfully, according to published case reports).

Surgical debridement is contraindicated since pathergy will make the lesions worse.

In this case, the patient chose topical clobetasol ointment. She was lost to follow-up.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Flowers D, Usatine R. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:735-739.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

* http://www.mhprofessional.com/product.php?isbn=0071474641

Multiple facial bumps with weight loss

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 12-Year-old girl came into our hospital for treatment of multiple bumps that had developed around her eyes and other areas of her face 2 months earlier. She had difficulty opening her eyes and complained of gradual weight loss.

On examination, we noted numerous skin-colored, shiny, dome-shaped, coalescing papules and nodules with central umbilications that were distributed mostly on her periocular and perinasal areas (FIGURE). When we expressed the papules with forceps, they exuded a cheesy material. We also noticed crusting and signs of inflammation on her eyelids.

The systemic examination was unremarkable.

FIGURE

Opening her eyes was difficult

This 12-year-old patient had multiple dome-shaped, coalescing papules and nodules with central umbilications in the periocular and perinasal areas.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a relatively common, benign, viral cutaneous infection that primarily affects children, sexually active adults, and immunodeficient individuals. MC accounts for approximately 1% of all diagnosed skin disorders in the United States; internationally, however, the incidence is higher.1 The causative organism of MC is a member of the Poxviridae family2 and is thought to be transmitted by close personal contact, autoinoculation, and fomites.3

MC is clinically characterized by the presence of pearly white, dome-shaped papules or nodules with central dells. The lesions are typically located on the trunk, body folds, extremities, and genitalia (particularly when the infection is sexually acquired).2,3 Pruritus and an eczematous reaction can develop around the lesions.

MC is a recognized ocular complication of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Periocular MC can also occur after eyebrow shaping in beauty salons.4 In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, lesions are usually widespread, tend to be large, and usually occur during the advanced stage of HIV infection.2,5

The differential includes carcinoma

When considering a diagnosis of MC, you’ll need to rule out the following causes of similar-looking papules and nodules:

Nodular basal cell carcinoma presents as a slow-growing, firm, shiny, pearly nodule with fine telangiectasia. It may also present as a cystic lesion that can be mistaken for inclusion cysts of the eyelid. If left untreated, the tumor may ulcerate.

Juvenile xanthogranulomas are rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. Patients may have one or several papules or nodules in the head and neck region; these lesions may appear elsewhere, as well.

Cryptococcosis may present as painless papules or pustules, which then become nodules that may ulcerate. The lesions may show central umbilications.

Keratoacanthoma begins as a firm, roundish, skin-colored or reddish papule that rapidly progresses to a dome-shaped nodule, with a smooth, shiny surface and a central crateriform ulceration or keratin plug. Patients typically have a solitary lesion that may appear on the face, neck, or dorsum of the upper extremities.

Penicillosis often presents with MC-like skin lesions, in addition to fever, anemia, hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and productive cough.

History and lab work clinch the Dx

Diagnosis is made by the distinctive clinical appearance, but can be confirmed by skin biopsy demonstrating eosinophilic molluscum bodies packed into the cells of the spinous layer of the epidermis.3 Giemsa stain of the material obtained from a crushed papule will reveal the presence of pathognomonic “molluscum bodies” in the cells of the epidermis.2,3

Our patient’s Giemsa stain revealed molluscum bodies. And since it is always wise to rule out concomitant HIV infection in patients who have giant MC, we tested our patient. Her results were positive; she had a CD4+ count of 93 cells/mm3.

Many treatment options from which to choose

MC is usually self-limiting, although it can take several months—or even a few years—to resolve on its own6 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). However, most patients with MC should receive treatment to obtain relief from symptoms, prevent autoinoculation or transmission to close contacts, decrease occurrence of scarring, reduce secondary bacterial infections, and improve cosmesis.

Several treatment options are available, and most rely on destruction of the lesions. Manual extrusion is a simple but effective therapy6 (SOR: B). Cryotherapy and curettage are also effective treatment options5 (SOR: C). Pretreatment topical anesthesia is often helpful if these therapies are used in children.

Topical imiquimod2 (1%-5%) cream applied 3 to 7 times a week can be used to treat generalized MC infection or MC localized to the anogenital area6 (SOR: A). Some patients may improve with topical tretinoin therapy6 (SOR: C).

Chemical cauterization with 10% povidone iodine with 50% salicylic acid7 (SOR: B), 10% potassium hydroxide8 (SOR: B), cantharidin2 (SOR: C), or 25% to 50% trichloroacetic acid6 (SOR: C) is also effective. Treatment with flashlamp pulsed dye laser is a safe and efficient treatment modality9 (SOR: C). Cidofovir10 (1%-3%) cream or ointment, electron beam therapy, and photodynamic therapy have also been used with variable success rates6 (SOR: C).

MC is particularly difficult to treat in patients with poorly managed HIV and AIDS. Pairing proper antiretroviral therapy with lesion-destroying therapies is usually helpful for these patients.3

If you are caring for a patient with giant MC, you’ll need to stress the benign—but potentially contagious—nature of the disease. Tell the patient to wash his or her hands frequently, to avoid scratching the lesions, and to keep infected areas covered with clothing (when possible). In suspected sexually transmitted cases, the patient should adopt safe sexual practices or abstinence, if necessary. It is unclear whether condoms or other barrier methods provide adequate protection.1

Our patient transfers to the HIV clinic

We sequentially expressed the large lesions on our patient’s face and put her on a course of cefadroxil to control the secondary infection of MC. Her facial lesions gradually improved over 2 months.

We also referred the patient to our institution’s HIV clinic, where she was put on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). We advised her mother to get tested for HIV, and she turned out to be HIV positive, as well.

CORRESPONDENCE Sudip Kumar Ghosh, MD, DNB, Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy, R.G. Kar Medical College, 1 Khudiram Bose Sarani, Kolkata-700004, West Bengal, India; [email protected]

1. Taillac PP. Molluscum contagiosum: eMedicine, Emergency Medicine. Available at: . Accessed October 29, 2010.

2. Tom W, Friedlander SF. Poxvirus infections. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008: 1899-1913.

3. Turchin I, Barankin B. Dermacase. Molluscum contagiosum. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:1395-1407.

4. Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D. Molluscum contagiosum after eyebrow shaping: a beauty salon hazard. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e339-e340.

5. Gur I. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in HIVseropositive patients: a unique entity or insignificant finding? Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:503-506.

6. Mckenna DB, Benton EC. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 2nd ed. London: Mosby; 2002: 399-401.

7. Ohkuma M. Molluscum contagiosum treated with iodine solution and salicylic acid plaster. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:443-445.

8. Mahajan BB, Pall A, Gupta RR. Topical 20% KOH—an effective therapeutic modality for molluscum contagiosum in children. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:175-177.

9. Binder B, Weger W, Komericki P, et al. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum with a pulsed dye laser: pilot study with 19 children. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:121-125.

10. Watanabe T, Tamaki K. Cidofovir diphosphate inhibits molluscum contagiosum virus DNA polymerase activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1327-1329.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 12-Year-old girl came into our hospital for treatment of multiple bumps that had developed around her eyes and other areas of her face 2 months earlier. She had difficulty opening her eyes and complained of gradual weight loss.

On examination, we noted numerous skin-colored, shiny, dome-shaped, coalescing papules and nodules with central umbilications that were distributed mostly on her periocular and perinasal areas (FIGURE). When we expressed the papules with forceps, they exuded a cheesy material. We also noticed crusting and signs of inflammation on her eyelids.

The systemic examination was unremarkable.

FIGURE

Opening her eyes was difficult

This 12-year-old patient had multiple dome-shaped, coalescing papules and nodules with central umbilications in the periocular and perinasal areas.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a relatively common, benign, viral cutaneous infection that primarily affects children, sexually active adults, and immunodeficient individuals. MC accounts for approximately 1% of all diagnosed skin disorders in the United States; internationally, however, the incidence is higher.1 The causative organism of MC is a member of the Poxviridae family2 and is thought to be transmitted by close personal contact, autoinoculation, and fomites.3

MC is clinically characterized by the presence of pearly white, dome-shaped papules or nodules with central dells. The lesions are typically located on the trunk, body folds, extremities, and genitalia (particularly when the infection is sexually acquired).2,3 Pruritus and an eczematous reaction can develop around the lesions.

MC is a recognized ocular complication of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Periocular MC can also occur after eyebrow shaping in beauty salons.4 In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, lesions are usually widespread, tend to be large, and usually occur during the advanced stage of HIV infection.2,5

The differential includes carcinoma

When considering a diagnosis of MC, you’ll need to rule out the following causes of similar-looking papules and nodules:

Nodular basal cell carcinoma presents as a slow-growing, firm, shiny, pearly nodule with fine telangiectasia. It may also present as a cystic lesion that can be mistaken for inclusion cysts of the eyelid. If left untreated, the tumor may ulcerate.

Juvenile xanthogranulomas are rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. Patients may have one or several papules or nodules in the head and neck region; these lesions may appear elsewhere, as well.

Cryptococcosis may present as painless papules or pustules, which then become nodules that may ulcerate. The lesions may show central umbilications.

Keratoacanthoma begins as a firm, roundish, skin-colored or reddish papule that rapidly progresses to a dome-shaped nodule, with a smooth, shiny surface and a central crateriform ulceration or keratin plug. Patients typically have a solitary lesion that may appear on the face, neck, or dorsum of the upper extremities.

Penicillosis often presents with MC-like skin lesions, in addition to fever, anemia, hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and productive cough.

History and lab work clinch the Dx

Diagnosis is made by the distinctive clinical appearance, but can be confirmed by skin biopsy demonstrating eosinophilic molluscum bodies packed into the cells of the spinous layer of the epidermis.3 Giemsa stain of the material obtained from a crushed papule will reveal the presence of pathognomonic “molluscum bodies” in the cells of the epidermis.2,3

Our patient’s Giemsa stain revealed molluscum bodies. And since it is always wise to rule out concomitant HIV infection in patients who have giant MC, we tested our patient. Her results were positive; she had a CD4+ count of 93 cells/mm3.

Many treatment options from which to choose

MC is usually self-limiting, although it can take several months—or even a few years—to resolve on its own6 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). However, most patients with MC should receive treatment to obtain relief from symptoms, prevent autoinoculation or transmission to close contacts, decrease occurrence of scarring, reduce secondary bacterial infections, and improve cosmesis.

Several treatment options are available, and most rely on destruction of the lesions. Manual extrusion is a simple but effective therapy6 (SOR: B). Cryotherapy and curettage are also effective treatment options5 (SOR: C). Pretreatment topical anesthesia is often helpful if these therapies are used in children.

Topical imiquimod2 (1%-5%) cream applied 3 to 7 times a week can be used to treat generalized MC infection or MC localized to the anogenital area6 (SOR: A). Some patients may improve with topical tretinoin therapy6 (SOR: C).

Chemical cauterization with 10% povidone iodine with 50% salicylic acid7 (SOR: B), 10% potassium hydroxide8 (SOR: B), cantharidin2 (SOR: C), or 25% to 50% trichloroacetic acid6 (SOR: C) is also effective. Treatment with flashlamp pulsed dye laser is a safe and efficient treatment modality9 (SOR: C). Cidofovir10 (1%-3%) cream or ointment, electron beam therapy, and photodynamic therapy have also been used with variable success rates6 (SOR: C).

MC is particularly difficult to treat in patients with poorly managed HIV and AIDS. Pairing proper antiretroviral therapy with lesion-destroying therapies is usually helpful for these patients.3

If you are caring for a patient with giant MC, you’ll need to stress the benign—but potentially contagious—nature of the disease. Tell the patient to wash his or her hands frequently, to avoid scratching the lesions, and to keep infected areas covered with clothing (when possible). In suspected sexually transmitted cases, the patient should adopt safe sexual practices or abstinence, if necessary. It is unclear whether condoms or other barrier methods provide adequate protection.1

Our patient transfers to the HIV clinic

We sequentially expressed the large lesions on our patient’s face and put her on a course of cefadroxil to control the secondary infection of MC. Her facial lesions gradually improved over 2 months.

We also referred the patient to our institution’s HIV clinic, where she was put on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). We advised her mother to get tested for HIV, and she turned out to be HIV positive, as well.

CORRESPONDENCE Sudip Kumar Ghosh, MD, DNB, Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy, R.G. Kar Medical College, 1 Khudiram Bose Sarani, Kolkata-700004, West Bengal, India; [email protected]

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 12-Year-old girl came into our hospital for treatment of multiple bumps that had developed around her eyes and other areas of her face 2 months earlier. She had difficulty opening her eyes and complained of gradual weight loss.

On examination, we noted numerous skin-colored, shiny, dome-shaped, coalescing papules and nodules with central umbilications that were distributed mostly on her periocular and perinasal areas (FIGURE). When we expressed the papules with forceps, they exuded a cheesy material. We also noticed crusting and signs of inflammation on her eyelids.

The systemic examination was unremarkable.

FIGURE

Opening her eyes was difficult

This 12-year-old patient had multiple dome-shaped, coalescing papules and nodules with central umbilications in the periocular and perinasal areas.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a relatively common, benign, viral cutaneous infection that primarily affects children, sexually active adults, and immunodeficient individuals. MC accounts for approximately 1% of all diagnosed skin disorders in the United States; internationally, however, the incidence is higher.1 The causative organism of MC is a member of the Poxviridae family2 and is thought to be transmitted by close personal contact, autoinoculation, and fomites.3

MC is clinically characterized by the presence of pearly white, dome-shaped papules or nodules with central dells. The lesions are typically located on the trunk, body folds, extremities, and genitalia (particularly when the infection is sexually acquired).2,3 Pruritus and an eczematous reaction can develop around the lesions.

MC is a recognized ocular complication of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Periocular MC can also occur after eyebrow shaping in beauty salons.4 In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, lesions are usually widespread, tend to be large, and usually occur during the advanced stage of HIV infection.2,5

The differential includes carcinoma

When considering a diagnosis of MC, you’ll need to rule out the following causes of similar-looking papules and nodules:

Nodular basal cell carcinoma presents as a slow-growing, firm, shiny, pearly nodule with fine telangiectasia. It may also present as a cystic lesion that can be mistaken for inclusion cysts of the eyelid. If left untreated, the tumor may ulcerate.

Juvenile xanthogranulomas are rubbery, tan-orange papules or nodules. Patients may have one or several papules or nodules in the head and neck region; these lesions may appear elsewhere, as well.

Cryptococcosis may present as painless papules or pustules, which then become nodules that may ulcerate. The lesions may show central umbilications.

Keratoacanthoma begins as a firm, roundish, skin-colored or reddish papule that rapidly progresses to a dome-shaped nodule, with a smooth, shiny surface and a central crateriform ulceration or keratin plug. Patients typically have a solitary lesion that may appear on the face, neck, or dorsum of the upper extremities.

Penicillosis often presents with MC-like skin lesions, in addition to fever, anemia, hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and productive cough.

History and lab work clinch the Dx

Diagnosis is made by the distinctive clinical appearance, but can be confirmed by skin biopsy demonstrating eosinophilic molluscum bodies packed into the cells of the spinous layer of the epidermis.3 Giemsa stain of the material obtained from a crushed papule will reveal the presence of pathognomonic “molluscum bodies” in the cells of the epidermis.2,3

Our patient’s Giemsa stain revealed molluscum bodies. And since it is always wise to rule out concomitant HIV infection in patients who have giant MC, we tested our patient. Her results were positive; she had a CD4+ count of 93 cells/mm3.

Many treatment options from which to choose

MC is usually self-limiting, although it can take several months—or even a few years—to resolve on its own6 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). However, most patients with MC should receive treatment to obtain relief from symptoms, prevent autoinoculation or transmission to close contacts, decrease occurrence of scarring, reduce secondary bacterial infections, and improve cosmesis.

Several treatment options are available, and most rely on destruction of the lesions. Manual extrusion is a simple but effective therapy6 (SOR: B). Cryotherapy and curettage are also effective treatment options5 (SOR: C). Pretreatment topical anesthesia is often helpful if these therapies are used in children.

Topical imiquimod2 (1%-5%) cream applied 3 to 7 times a week can be used to treat generalized MC infection or MC localized to the anogenital area6 (SOR: A). Some patients may improve with topical tretinoin therapy6 (SOR: C).

Chemical cauterization with 10% povidone iodine with 50% salicylic acid7 (SOR: B), 10% potassium hydroxide8 (SOR: B), cantharidin2 (SOR: C), or 25% to 50% trichloroacetic acid6 (SOR: C) is also effective. Treatment with flashlamp pulsed dye laser is a safe and efficient treatment modality9 (SOR: C). Cidofovir10 (1%-3%) cream or ointment, electron beam therapy, and photodynamic therapy have also been used with variable success rates6 (SOR: C).

MC is particularly difficult to treat in patients with poorly managed HIV and AIDS. Pairing proper antiretroviral therapy with lesion-destroying therapies is usually helpful for these patients.3

If you are caring for a patient with giant MC, you’ll need to stress the benign—but potentially contagious—nature of the disease. Tell the patient to wash his or her hands frequently, to avoid scratching the lesions, and to keep infected areas covered with clothing (when possible). In suspected sexually transmitted cases, the patient should adopt safe sexual practices or abstinence, if necessary. It is unclear whether condoms or other barrier methods provide adequate protection.1

Our patient transfers to the HIV clinic

We sequentially expressed the large lesions on our patient’s face and put her on a course of cefadroxil to control the secondary infection of MC. Her facial lesions gradually improved over 2 months.

We also referred the patient to our institution’s HIV clinic, where she was put on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). We advised her mother to get tested for HIV, and she turned out to be HIV positive, as well.

CORRESPONDENCE Sudip Kumar Ghosh, MD, DNB, Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy, R.G. Kar Medical College, 1 Khudiram Bose Sarani, Kolkata-700004, West Bengal, India; [email protected]

1. Taillac PP. Molluscum contagiosum: eMedicine, Emergency Medicine. Available at: . Accessed October 29, 2010.

2. Tom W, Friedlander SF. Poxvirus infections. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008: 1899-1913.

3. Turchin I, Barankin B. Dermacase. Molluscum contagiosum. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:1395-1407.

4. Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D. Molluscum contagiosum after eyebrow shaping: a beauty salon hazard. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e339-e340.

5. Gur I. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in HIVseropositive patients: a unique entity or insignificant finding? Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:503-506.

6. Mckenna DB, Benton EC. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 2nd ed. London: Mosby; 2002: 399-401.

7. Ohkuma M. Molluscum contagiosum treated with iodine solution and salicylic acid plaster. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:443-445.

8. Mahajan BB, Pall A, Gupta RR. Topical 20% KOH—an effective therapeutic modality for molluscum contagiosum in children. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:175-177.

9. Binder B, Weger W, Komericki P, et al. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum with a pulsed dye laser: pilot study with 19 children. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:121-125.

10. Watanabe T, Tamaki K. Cidofovir diphosphate inhibits molluscum contagiosum virus DNA polymerase activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1327-1329.

1. Taillac PP. Molluscum contagiosum: eMedicine, Emergency Medicine. Available at: . Accessed October 29, 2010.

2. Tom W, Friedlander SF. Poxvirus infections. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008: 1899-1913.

3. Turchin I, Barankin B. Dermacase. Molluscum contagiosum. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:1395-1407.

4. Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D. Molluscum contagiosum after eyebrow shaping: a beauty salon hazard. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e339-e340.

5. Gur I. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in HIVseropositive patients: a unique entity or insignificant finding? Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:503-506.

6. Mckenna DB, Benton EC. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 2nd ed. London: Mosby; 2002: 399-401.

7. Ohkuma M. Molluscum contagiosum treated with iodine solution and salicylic acid plaster. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:443-445.

8. Mahajan BB, Pall A, Gupta RR. Topical 20% KOH—an effective therapeutic modality for molluscum contagiosum in children. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:175-177.

9. Binder B, Weger W, Komericki P, et al. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum with a pulsed dye laser: pilot study with 19 children. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:121-125.

10. Watanabe T, Tamaki K. Cidofovir diphosphate inhibits molluscum contagiosum virus DNA polymerase activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1327-1329.

Verrucous papule on thigh

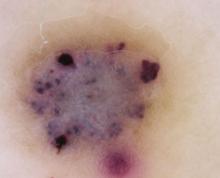

A 21-year-old man came into our medical center to have a lesion on his thigh examined. He said the lesion developed a few months earlier at the site of minimal trauma. He noted that, over the previous few months, the lesion had progressively darkened and it bled sporadically. On examination, we noted a solitary 7.5-mm firm, blue-black verrucous papule over the right medial thigh (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). There were no other lesions.

The patient indicated that he had gotten sunburned many times in the past. He also said that he had an aunt who’d had a melanoma.

FIGURE 1

A lesion that bled sporadically

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Angiokeratoma

An angiokeratoma is a benign pink-red to blue-black variably sized papule or plaque that is typically 2 to 10 mm in diameter.1 Angiokeratomas are composed of a series of subepidermal dilated capillaries that have a characteristic hyperkeratotic surface and bleed easily.2 These lesions are rare, with a prevalence estimated to be 0.16% in the general population.3

The pathogenesis of angiokeratoma formation is unclear; however, multiple theories exist. The development of these lesions may be related to repeated trauma or friction at a particular site.4 Alternatively, increased venous blood pressure or primary degeneration of vascular elastic tissue could explain their development.5 While their cause is unclear, the initial event in the development of an angiokeratoma is believed to be the development of a vascular ectasia within the papillary dermis. The epidermal reaction appears to be a secondary phenomenon due to increased proliferative capacity on the surface of the vessels.5

The most common form—as seen in this case—is the solitary or sporadic angiokeratoma. It comprises 70% to 83% of all cases of angiokeratomas3 and usually develops on the lower extremities. Angiokeratomas typically arise during the first 2 decades of life,6 and are more common in men.3 Other types of angiokeratomas include angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry’s disease).7,8

Angiokeratoma of Mibelli is characterized by pink to dark red papules or verrucoid nodules that occur most commonly in men7 and involve the bony prominences, such as the elbows.

Fordyce lesions involve the scrotum or vulva and are usually numerous and related to conditions with elevated venous pressure.

Angiokeratoma circumscriptum usually present as papules that commonly coalesce to form plaques.

Fabry’s disease, or angiokeratoma corporis diffusum, is an X-linked recessive disease related to a deficiency in alpha-galactosidase A. This leads to multiple, variably sized angiokeratomas occurring in childhood that are concentrated between the umbilicus and the knees. This disease invariably leads to involvement of other organs, which may result in renal failure, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accidents.1,7

A mimicker of melanoma

An angiokeratoma is an uncommon, though important, mimicker of melanoma. (For more on other lesions that can be confused with melanoma, see “Nonmelanocytic melanoma mimickers”.)

Melanoma is the most aggressive and potentially life-threatening neoplasm in the differential diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. Risk factors for melanoma include increasing age, fair skin and hair color, tendency for freckling, number of moles (5 large or >50 small nevi doubles the risk of melanoma), a personal or first-degree family history of melanoma, and a history of intermittent sunburns.9-12

A number of nonmelanocytic lesions can be confused with melanoma. They include the following:

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are a type of keratinocytic neoplasm that typically develops on the sun-exposed skin of the elderly. An AK is typically 3 to 10 mm in size, pink to red in color, and has scaling secondary to local hyperkeratosis. If these lesions are left untreated, they can develop into squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) at a rate of 0.24% annually.15,16 Thus, AKs are more often a concern for SCC than for melanoma. However, the pigmented variant of an AK can clinically and histologically raise concern for melanoma due to its pigmentation and microscopic evidence of melanin within keratinocytes and macrophages.15 If it is not possible to differentiate an AK from melanoma clinically or histologically, immunohistochemistry is often required to make the final diagnosis. For example, immunohistochemical staining with S-100 can be used to identify epidermal melanocytes and distinguish them from atypical keratinocytes.17

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer.18 While most BCCs are amelanocytic, 7% of BCCs are pigmented and present as irregularly pigmented nodules with irregular telangiectatic vessels on their surface. The center of a BCC may be depressed or ulcerated and may easily crust or bleed. Definitive diagnosis may be made histologically. A BCC typically consists of columns of basaloid cells with atypical nuclei, sparse cytoplasm, and peripheral cellular palisading.19 BCCs are easily differentiated from melanoma using immunohistochemistry, as they are negative for traditional melanocytic markers.17

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are among the most common skin lesions and represent a benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes. The appearance of an SK can vary from a smooth peppered appearance to a rough surface that may be irregularly pigmented, dry, and fissured. Given their range of presentation, it is common for SKs to be biopsied to evaluate for melanoma and occasionally BCC.20

Dermatofibromas (DFs) are common benign skin lesions that typically appear as pink-to brown-colored firm nodules that represent a localized response to skin injury and inflammation. DFs are typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter and are most commonly located on the anterior surface of the thigh. Histologic analysis of a DF reveals an acanthotic epidermis with a proliferation of spindle cells in the mid and lower dermis, with capillaries dispersed throughout. A common finding in DFs is the trapping of collagen within the spindle cell at the periphery of the lesion.21

How to diagnose angiokeratoma

The clinical presentation typically suffices in making the diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. If dermoscopy is performed, the characteristic findings include the presence of scale and purple lacunae13 (FIGURE 2). However, when there is suspicion of melanoma or the clinical diagnosis is in doubt, the entire lesion should be removed (with narrow margins) in order to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Histological findings consist of dilated subepidermal vessels associated with epidermal hyperkeratosis.3

FIGURE 2

A view from the dermatoscope

No need to treat, unless there are cosmetic concerns

If the diagnosis is straightforward and a biopsy is not needed, no treatment is necessary because simple angiokeratomas are benign entities. However, treatment may be considered for cosmetic purposes, or to prevent bothersome bleeding. Angiokeratomas may be removed via shave or standard excision, electrodessication and curettage, or destroyed with a laser. For Fabry’s disease, in which numerous angiokeratomas pose a cosmetic concern, laser therapy, including the use of an argon, copper, Nd:Yag, KTP 532-nm, or Candela V-beam laser, is preferred.14

In our patient’s case, we performed a 2-mm punch biopsy, which revealed that the lesion was an angiokeratoma. It was subsequently removed by shave biopsy with clear margins.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/SG05D/ Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Karen JK, Hale EK, Ma L. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2005;11:8. Available at: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/114/NYU/NYUtexts/0419054.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

2. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

3. Zaballos P, Dauft C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

4. Kim JH, Nam TS, Kim SH. Solitary angiokeratoma developed in one area of lymphangioma circumscriptum. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:169-170.

5. Sion-Vardy N, Manor E, Puterman M, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma of the tongue. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:12-14.

6. Vascular tumors and malformations In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Dinulos JG, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004:486–487.

7. Leis-Dosil VM, Alijo-Serrano F, Aviles-Izquierdo JA, et al. Angiokeratoma of the glans penis: clinical, histopathological and dermoscopic correlation. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2007;13:19. Available from: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/132/case_presentations/angiokeratoma/dosil.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

8. Erkek E, Basar MM, Bagci Y, et al. Fordyce angiokeratomas as clues to local venous hypertension. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1325-1326.

9. Rager EL, Bridgeford EP, Ollila DW. Cutaneous melanoma: update on prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:269-276.

10. Chudnovsky Y, Khavari PA, Adams AE. Melanoma genetics and the development of rational therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:813-824.

11. Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:163-172.

12. Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. JAMA. 2004;292:2771-2776.

13. Johr RH, Soyer P, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:130.

14. Enjolras O. Vascular malformations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby; 2003: 1621–1622.

15. Peris K, Micantonio T, Piccolo D, et al. Dermoscopic features of actinic keratosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:970-976.

16. McIntyre WJ, Downs MR, Bedwell SA. Treatment options for actinic keratosis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:667-671.

17. Kamil ZS, Tong LC, Habeeb AA, et al. Non-melanocytic mimics of melanoma: part 1: intraepidermal mimics. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:120-127.

18. Wong CS, Strange RC, Lear JT. Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ. 2003;327:794-798.

19. Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

20. Braun RP, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Dermoscopic diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:270-272.

21. Agero AL, Taliercio S, Dusza SW, et al. Conventional and polarized dermoscopy features of dermatofibroma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1431-1437.

A 21-year-old man came into our medical center to have a lesion on his thigh examined. He said the lesion developed a few months earlier at the site of minimal trauma. He noted that, over the previous few months, the lesion had progressively darkened and it bled sporadically. On examination, we noted a solitary 7.5-mm firm, blue-black verrucous papule over the right medial thigh (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). There were no other lesions.

The patient indicated that he had gotten sunburned many times in the past. He also said that he had an aunt who’d had a melanoma.

FIGURE 1

A lesion that bled sporadically

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Angiokeratoma

An angiokeratoma is a benign pink-red to blue-black variably sized papule or plaque that is typically 2 to 10 mm in diameter.1 Angiokeratomas are composed of a series of subepidermal dilated capillaries that have a characteristic hyperkeratotic surface and bleed easily.2 These lesions are rare, with a prevalence estimated to be 0.16% in the general population.3

The pathogenesis of angiokeratoma formation is unclear; however, multiple theories exist. The development of these lesions may be related to repeated trauma or friction at a particular site.4 Alternatively, increased venous blood pressure or primary degeneration of vascular elastic tissue could explain their development.5 While their cause is unclear, the initial event in the development of an angiokeratoma is believed to be the development of a vascular ectasia within the papillary dermis. The epidermal reaction appears to be a secondary phenomenon due to increased proliferative capacity on the surface of the vessels.5

The most common form—as seen in this case—is the solitary or sporadic angiokeratoma. It comprises 70% to 83% of all cases of angiokeratomas3 and usually develops on the lower extremities. Angiokeratomas typically arise during the first 2 decades of life,6 and are more common in men.3 Other types of angiokeratomas include angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry’s disease).7,8

Angiokeratoma of Mibelli is characterized by pink to dark red papules or verrucoid nodules that occur most commonly in men7 and involve the bony prominences, such as the elbows.

Fordyce lesions involve the scrotum or vulva and are usually numerous and related to conditions with elevated venous pressure.

Angiokeratoma circumscriptum usually present as papules that commonly coalesce to form plaques.

Fabry’s disease, or angiokeratoma corporis diffusum, is an X-linked recessive disease related to a deficiency in alpha-galactosidase A. This leads to multiple, variably sized angiokeratomas occurring in childhood that are concentrated between the umbilicus and the knees. This disease invariably leads to involvement of other organs, which may result in renal failure, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accidents.1,7

A mimicker of melanoma

An angiokeratoma is an uncommon, though important, mimicker of melanoma. (For more on other lesions that can be confused with melanoma, see “Nonmelanocytic melanoma mimickers”.)

Melanoma is the most aggressive and potentially life-threatening neoplasm in the differential diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. Risk factors for melanoma include increasing age, fair skin and hair color, tendency for freckling, number of moles (5 large or >50 small nevi doubles the risk of melanoma), a personal or first-degree family history of melanoma, and a history of intermittent sunburns.9-12

A number of nonmelanocytic lesions can be confused with melanoma. They include the following:

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are a type of keratinocytic neoplasm that typically develops on the sun-exposed skin of the elderly. An AK is typically 3 to 10 mm in size, pink to red in color, and has scaling secondary to local hyperkeratosis. If these lesions are left untreated, they can develop into squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) at a rate of 0.24% annually.15,16 Thus, AKs are more often a concern for SCC than for melanoma. However, the pigmented variant of an AK can clinically and histologically raise concern for melanoma due to its pigmentation and microscopic evidence of melanin within keratinocytes and macrophages.15 If it is not possible to differentiate an AK from melanoma clinically or histologically, immunohistochemistry is often required to make the final diagnosis. For example, immunohistochemical staining with S-100 can be used to identify epidermal melanocytes and distinguish them from atypical keratinocytes.17

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer.18 While most BCCs are amelanocytic, 7% of BCCs are pigmented and present as irregularly pigmented nodules with irregular telangiectatic vessels on their surface. The center of a BCC may be depressed or ulcerated and may easily crust or bleed. Definitive diagnosis may be made histologically. A BCC typically consists of columns of basaloid cells with atypical nuclei, sparse cytoplasm, and peripheral cellular palisading.19 BCCs are easily differentiated from melanoma using immunohistochemistry, as they are negative for traditional melanocytic markers.17

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are among the most common skin lesions and represent a benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes. The appearance of an SK can vary from a smooth peppered appearance to a rough surface that may be irregularly pigmented, dry, and fissured. Given their range of presentation, it is common for SKs to be biopsied to evaluate for melanoma and occasionally BCC.20

Dermatofibromas (DFs) are common benign skin lesions that typically appear as pink-to brown-colored firm nodules that represent a localized response to skin injury and inflammation. DFs are typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter and are most commonly located on the anterior surface of the thigh. Histologic analysis of a DF reveals an acanthotic epidermis with a proliferation of spindle cells in the mid and lower dermis, with capillaries dispersed throughout. A common finding in DFs is the trapping of collagen within the spindle cell at the periphery of the lesion.21

How to diagnose angiokeratoma

The clinical presentation typically suffices in making the diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. If dermoscopy is performed, the characteristic findings include the presence of scale and purple lacunae13 (FIGURE 2). However, when there is suspicion of melanoma or the clinical diagnosis is in doubt, the entire lesion should be removed (with narrow margins) in order to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Histological findings consist of dilated subepidermal vessels associated with epidermal hyperkeratosis.3

FIGURE 2

A view from the dermatoscope

No need to treat, unless there are cosmetic concerns

If the diagnosis is straightforward and a biopsy is not needed, no treatment is necessary because simple angiokeratomas are benign entities. However, treatment may be considered for cosmetic purposes, or to prevent bothersome bleeding. Angiokeratomas may be removed via shave or standard excision, electrodessication and curettage, or destroyed with a laser. For Fabry’s disease, in which numerous angiokeratomas pose a cosmetic concern, laser therapy, including the use of an argon, copper, Nd:Yag, KTP 532-nm, or Candela V-beam laser, is preferred.14

In our patient’s case, we performed a 2-mm punch biopsy, which revealed that the lesion was an angiokeratoma. It was subsequently removed by shave biopsy with clear margins.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/SG05D/ Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

A 21-year-old man came into our medical center to have a lesion on his thigh examined. He said the lesion developed a few months earlier at the site of minimal trauma. He noted that, over the previous few months, the lesion had progressively darkened and it bled sporadically. On examination, we noted a solitary 7.5-mm firm, blue-black verrucous papule over the right medial thigh (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). There were no other lesions.

The patient indicated that he had gotten sunburned many times in the past. He also said that he had an aunt who’d had a melanoma.

FIGURE 1

A lesion that bled sporadically

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Angiokeratoma

An angiokeratoma is a benign pink-red to blue-black variably sized papule or plaque that is typically 2 to 10 mm in diameter.1 Angiokeratomas are composed of a series of subepidermal dilated capillaries that have a characteristic hyperkeratotic surface and bleed easily.2 These lesions are rare, with a prevalence estimated to be 0.16% in the general population.3

The pathogenesis of angiokeratoma formation is unclear; however, multiple theories exist. The development of these lesions may be related to repeated trauma or friction at a particular site.4 Alternatively, increased venous blood pressure or primary degeneration of vascular elastic tissue could explain their development.5 While their cause is unclear, the initial event in the development of an angiokeratoma is believed to be the development of a vascular ectasia within the papillary dermis. The epidermal reaction appears to be a secondary phenomenon due to increased proliferative capacity on the surface of the vessels.5

The most common form—as seen in this case—is the solitary or sporadic angiokeratoma. It comprises 70% to 83% of all cases of angiokeratomas3 and usually develops on the lower extremities. Angiokeratomas typically arise during the first 2 decades of life,6 and are more common in men.3 Other types of angiokeratomas include angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry’s disease).7,8

Angiokeratoma of Mibelli is characterized by pink to dark red papules or verrucoid nodules that occur most commonly in men7 and involve the bony prominences, such as the elbows.

Fordyce lesions involve the scrotum or vulva and are usually numerous and related to conditions with elevated venous pressure.

Angiokeratoma circumscriptum usually present as papules that commonly coalesce to form plaques.

Fabry’s disease, or angiokeratoma corporis diffusum, is an X-linked recessive disease related to a deficiency in alpha-galactosidase A. This leads to multiple, variably sized angiokeratomas occurring in childhood that are concentrated between the umbilicus and the knees. This disease invariably leads to involvement of other organs, which may result in renal failure, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accidents.1,7

A mimicker of melanoma

An angiokeratoma is an uncommon, though important, mimicker of melanoma. (For more on other lesions that can be confused with melanoma, see “Nonmelanocytic melanoma mimickers”.)

Melanoma is the most aggressive and potentially life-threatening neoplasm in the differential diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. Risk factors for melanoma include increasing age, fair skin and hair color, tendency for freckling, number of moles (5 large or >50 small nevi doubles the risk of melanoma), a personal or first-degree family history of melanoma, and a history of intermittent sunburns.9-12

A number of nonmelanocytic lesions can be confused with melanoma. They include the following:

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are a type of keratinocytic neoplasm that typically develops on the sun-exposed skin of the elderly. An AK is typically 3 to 10 mm in size, pink to red in color, and has scaling secondary to local hyperkeratosis. If these lesions are left untreated, they can develop into squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) at a rate of 0.24% annually.15,16 Thus, AKs are more often a concern for SCC than for melanoma. However, the pigmented variant of an AK can clinically and histologically raise concern for melanoma due to its pigmentation and microscopic evidence of melanin within keratinocytes and macrophages.15 If it is not possible to differentiate an AK from melanoma clinically or histologically, immunohistochemistry is often required to make the final diagnosis. For example, immunohistochemical staining with S-100 can be used to identify epidermal melanocytes and distinguish them from atypical keratinocytes.17

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer.18 While most BCCs are amelanocytic, 7% of BCCs are pigmented and present as irregularly pigmented nodules with irregular telangiectatic vessels on their surface. The center of a BCC may be depressed or ulcerated and may easily crust or bleed. Definitive diagnosis may be made histologically. A BCC typically consists of columns of basaloid cells with atypical nuclei, sparse cytoplasm, and peripheral cellular palisading.19 BCCs are easily differentiated from melanoma using immunohistochemistry, as they are negative for traditional melanocytic markers.17

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are among the most common skin lesions and represent a benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes. The appearance of an SK can vary from a smooth peppered appearance to a rough surface that may be irregularly pigmented, dry, and fissured. Given their range of presentation, it is common for SKs to be biopsied to evaluate for melanoma and occasionally BCC.20

Dermatofibromas (DFs) are common benign skin lesions that typically appear as pink-to brown-colored firm nodules that represent a localized response to skin injury and inflammation. DFs are typically 3 to 10 mm in diameter and are most commonly located on the anterior surface of the thigh. Histologic analysis of a DF reveals an acanthotic epidermis with a proliferation of spindle cells in the mid and lower dermis, with capillaries dispersed throughout. A common finding in DFs is the trapping of collagen within the spindle cell at the periphery of the lesion.21

How to diagnose angiokeratoma

The clinical presentation typically suffices in making the diagnosis of an angiokeratoma. If dermoscopy is performed, the characteristic findings include the presence of scale and purple lacunae13 (FIGURE 2). However, when there is suspicion of melanoma or the clinical diagnosis is in doubt, the entire lesion should be removed (with narrow margins) in order to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Histological findings consist of dilated subepidermal vessels associated with epidermal hyperkeratosis.3

FIGURE 2

A view from the dermatoscope

No need to treat, unless there are cosmetic concerns

If the diagnosis is straightforward and a biopsy is not needed, no treatment is necessary because simple angiokeratomas are benign entities. However, treatment may be considered for cosmetic purposes, or to prevent bothersome bleeding. Angiokeratomas may be removed via shave or standard excision, electrodessication and curettage, or destroyed with a laser. For Fabry’s disease, in which numerous angiokeratomas pose a cosmetic concern, laser therapy, including the use of an argon, copper, Nd:Yag, KTP 532-nm, or Candela V-beam laser, is preferred.14

In our patient’s case, we performed a 2-mm punch biopsy, which revealed that the lesion was an angiokeratoma. It was subsequently removed by shave biopsy with clear margins.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Capt, USAF, MC, Department of the Air Force, Wilford Hall Medical Center, 59 MDW/SG05D/ Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Karen JK, Hale EK, Ma L. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2005;11:8. Available at: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/114/NYU/NYUtexts/0419054.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

2. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

3. Zaballos P, Dauft C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

4. Kim JH, Nam TS, Kim SH. Solitary angiokeratoma developed in one area of lymphangioma circumscriptum. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:169-170.

5. Sion-Vardy N, Manor E, Puterman M, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma of the tongue. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:12-14.

6. Vascular tumors and malformations In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Dinulos JG, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004:486–487.

7. Leis-Dosil VM, Alijo-Serrano F, Aviles-Izquierdo JA, et al. Angiokeratoma of the glans penis: clinical, histopathological and dermoscopic correlation. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2007;13:19. Available from: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/132/case_presentations/angiokeratoma/dosil.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

8. Erkek E, Basar MM, Bagci Y, et al. Fordyce angiokeratomas as clues to local venous hypertension. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1325-1326.

9. Rager EL, Bridgeford EP, Ollila DW. Cutaneous melanoma: update on prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:269-276.

10. Chudnovsky Y, Khavari PA, Adams AE. Melanoma genetics and the development of rational therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:813-824.

11. Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:163-172.

12. Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. JAMA. 2004;292:2771-2776.

13. Johr RH, Soyer P, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:130.

14. Enjolras O. Vascular malformations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby; 2003: 1621–1622.

15. Peris K, Micantonio T, Piccolo D, et al. Dermoscopic features of actinic keratosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:970-976.

16. McIntyre WJ, Downs MR, Bedwell SA. Treatment options for actinic keratosis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:667-671.

17. Kamil ZS, Tong LC, Habeeb AA, et al. Non-melanocytic mimics of melanoma: part 1: intraepidermal mimics. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:120-127.

18. Wong CS, Strange RC, Lear JT. Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ. 2003;327:794-798.

19. Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

20. Braun RP, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Dermoscopic diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:270-272.

21. Agero AL, Taliercio S, Dusza SW, et al. Conventional and polarized dermoscopy features of dermatofibroma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1431-1437.

1. Karen JK, Hale EK, Ma L. Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2005;11:8. Available at: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/114/NYU/NYUtexts/0419054.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

2. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

3. Zaballos P, Dauft C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

4. Kim JH, Nam TS, Kim SH. Solitary angiokeratoma developed in one area of lymphangioma circumscriptum. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:169-170.

5. Sion-Vardy N, Manor E, Puterman M, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma of the tongue. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:12-14.

6. Vascular tumors and malformations In: Habif TP, Campbell JL, Dinulos JG, et al, eds. Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: Mosby; 2004:486–487.

7. Leis-Dosil VM, Alijo-Serrano F, Aviles-Izquierdo JA, et al. Angiokeratoma of the glans penis: clinical, histopathological and dermoscopic correlation. Dermatol Online J. [Internet]. 2007;13:19. Available from: http://dermatology.cdlib.org/132/case_presentations/angiokeratoma/dosil.html. Accessed September 24, 2010.

8. Erkek E, Basar MM, Bagci Y, et al. Fordyce angiokeratomas as clues to local venous hypertension. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1325-1326.

9. Rager EL, Bridgeford EP, Ollila DW. Cutaneous melanoma: update on prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:269-276.

10. Chudnovsky Y, Khavari PA, Adams AE. Melanoma genetics and the development of rational therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:813-824.

11. Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:163-172.

12. Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, et al. Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. JAMA. 2004;292:2771-2776.

13. Johr RH, Soyer P, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York, NY: Mosby; 2007:130.

14. Enjolras O. Vascular malformations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby; 2003: 1621–1622.

15. Peris K, Micantonio T, Piccolo D, et al. Dermoscopic features of actinic keratosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:970-976.

16. McIntyre WJ, Downs MR, Bedwell SA. Treatment options for actinic keratosis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:667-671.

17. Kamil ZS, Tong LC, Habeeb AA, et al. Non-melanocytic mimics of melanoma: part 1: intraepidermal mimics. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:120-127.

18. Wong CS, Strange RC, Lear JT. Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ. 2003;327:794-798.

19. Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

20. Braun RP, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Dermoscopic diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:270-272.

21. Agero AL, Taliercio S, Dusza SW, et al. Conventional and polarized dermoscopy features of dermatofibroma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1431-1437.

Erythematous rash on face

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 27-year-old Caucasian woman came into our clinic with an erythematous, papulopustular rash on her face. The small papules and pustules formed a confluence around her mouth and on her chin; the vermilion border was spared (FIGURE). The patient said that the rash started as a dry scaly patch on the corner of her mouth, and it spread over the course of a few weeks.

The patient had a history of eczema for which she used mometasone furoate cream. Initially, she thought the rash was a flare-up of her eczema, so she used her steroid cream. After using the cream on her face for a month, the patient reported that the rash continued to worsen and spread. She said that the rash was mildly itchy and that when she opened her mouth, it was moderately painful.

FIGURE

Patient confused rash with eczema flare

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Perioral dermatitis

Perioral dermatitis occurs in men and women of all ages and races, though it is more common in women between the ages of 16 and 45.1,2 Many agents have been implicated in the etiology of perioral dermatitis, including infectious pathogens, hormonal factors, and steroids. Moisturizing creams and cosmetics, such as foundation and blush, can cause occlusion of skin follicles, leading to proliferation of skin flora and the resultant papulopustular rash seen in perioral dermatitis.3

In a similar manner, fluorinated corticosteroids enable opportunistic fusobacteria to become pathogenic, leading to the condition. Other risk factors include premenstrual hormone changes, pregnancy, and the use of oral contraceptives, fluorinated toothpaste, inhaled steroids, or glucocorticoids.4

It’s easy to distinguish from these 3 conditions

The differential diagnosis includes contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea.

- Contact dermatitis is similar to perioral dermatitis in that the patient may indicate that she started using a new skin product. In most cases, the pruritus associated with contact dermatitis will aid in differentiating the 2 diagnoses.

- Atopic dermatitis is more common in children and rarely has an adult onset. Often, there is a personal or family history of asthma or allergies. Distribution in adults is more typically on flexure surfaces, hands, and upper eyelids, and it is itchier than perioral dermatitis.

- Rosacea is often associated with flushing, and is exacerbated by the ingestion of hot food and drinks, alcohol (red wine), and exposure to sun. The distribution is typically on the forehead, cheeks, nose, and around the eyes—rather than around the mouth.

A rash that’s painful and mildly itchy

Perioral dermatitis has distinct clinical features that distinguish it from other facial dermatoses. The rash is classically described as tiny, dry, erythematous papulopustules in a pattern around the mouth, nasolabial folds, and chin, with sparing of the vermilion border.1,2 The clinical course is variable, but is often chronic, with flares. Typically, the rash is only mildly pruritic, but a burning or painful sensation is common. Intolerance to sunlight, drying agents (such as soaps), or irritants (such as cosmetics) is also common.3

Treatment: Discontinue steroids, start antibiotics

If left untreated, perioral dermatitis rarely resolves on its own and will have a fluctuating course, punctuated by flares, that will last for years. The prognosis is excellent, however, once appropriate therapy is instituted; recurrence after treatment is low.5

Cessation of topical steroids is a mainstay of treatment6,7 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). High-potency topical steroids can cause short-term improvement of the rash; removal will cause short-term worsening of symptoms. It’s best, then, to switch your patient to a less potent steroid, and then gradually discontinue the steroid3 (SOR: C). Doing so can help the patient to avoid a rebound flare and the temptation to restart the steroid for short-term relief.

It’s also a good idea to tell the patient to stop using other causative agents, such as moisturizing creams, blush, foundation, oral contraceptives, and fluorinated toothpaste6 (SOR: C).

Several antibiotic regimens are successful in the treatment of perioral dermatitis. Tetracycline 250 mg twice daily, minocycline 100 mg daily, or doxycycline 100 mg daily for 2 to 3 weeks is the initial treatment. The treatment course may last up to 6 weeks8 (SOR: B). For children, pregnant women, or patients with allergies to certain antibiotics, erythromycin 250 mg twice daily for up to 6 weeks is also an option7 (SOR: C).

Topical treatments can also be used, but often take longer and have been shown to be less effective than oral therapies. Metronidazole 0.75% gel applied twice daily for 14 weeks or 1% cream applied twice daily for 8 weeks has been shown to be useful9,10 (SOR: C). Erythromycin 2% gel applied twice daily for several months is also effective7 (SOR: C).

Discontinuing the steroid was a challenge for our patient

We told our patient to discontinue her steroid cream, and we started her on metronidazole gel. She returned with significant worsening of her rash, including swelling and erythema. We therefore prescribed a brief course of prednisone for short-term relief while she was started on oral doxycycline. After 6 weeks of oral doxycycline therapy, her rash resolved. At a 6-month follow-up, the patient had experienced no further recurrence of the rash.

CORRESPONDENCE Marc Babaoff, MD, MAHEC Family Medicine Residency Program, 118 W. T. Weaver Boulevard, Asheville, NC 28804; [email protected]

1. Fitzpatrick TB, Johnson RA, Wolff K. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology: Common and Serious Diseases. New York: McGraw Hill; 1997:16–17.

2. White G. Color Atlas of Dermatology. 3rd ed. London: Elsevier Science Ltd.; 2004:89.

3. Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

4. Wilkinson DS, Kirton V, Wilkinson JD. Perioral dermatitis: a 12-year review. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101:245-257.

5. Kalkoff KW, Buck A. Etiology of perioral dermatitis [in German]. Hautarzt. 1977;28:74-77.

6. Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Schwartz RA, et al. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1-15.

7. Weber K, Thurmayr R. Critical appraisal of reports on the treatment of perioral dermatitis. Dermatology. 2005;210:300-307.

8. Macdonald A, Feiwel M. Perioral dermatitis: aetiology and treatment with tetracycline. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:315-319.

9. Miller SR, Shalita AR. Topical metronidazole gel (0.75%) for the treatment of perioral dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:847-848.

10. Veien NK, Munkvad JM, Nielsen AO, et al. Topical metronidazole in the treatment of perioral dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:258-260.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 27-year-old Caucasian woman came into our clinic with an erythematous, papulopustular rash on her face. The small papules and pustules formed a confluence around her mouth and on her chin; the vermilion border was spared (FIGURE). The patient said that the rash started as a dry scaly patch on the corner of her mouth, and it spread over the course of a few weeks.

The patient had a history of eczema for which she used mometasone furoate cream. Initially, she thought the rash was a flare-up of her eczema, so she used her steroid cream. After using the cream on her face for a month, the patient reported that the rash continued to worsen and spread. She said that the rash was mildly itchy and that when she opened her mouth, it was moderately painful.

FIGURE

Patient confused rash with eczema flare

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Perioral dermatitis

Perioral dermatitis occurs in men and women of all ages and races, though it is more common in women between the ages of 16 and 45.1,2 Many agents have been implicated in the etiology of perioral dermatitis, including infectious pathogens, hormonal factors, and steroids. Moisturizing creams and cosmetics, such as foundation and blush, can cause occlusion of skin follicles, leading to proliferation of skin flora and the resultant papulopustular rash seen in perioral dermatitis.3

In a similar manner, fluorinated corticosteroids enable opportunistic fusobacteria to become pathogenic, leading to the condition. Other risk factors include premenstrual hormone changes, pregnancy, and the use of oral contraceptives, fluorinated toothpaste, inhaled steroids, or glucocorticoids.4

It’s easy to distinguish from these 3 conditions

The differential diagnosis includes contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea.

- Contact dermatitis is similar to perioral dermatitis in that the patient may indicate that she started using a new skin product. In most cases, the pruritus associated with contact dermatitis will aid in differentiating the 2 diagnoses.

- Atopic dermatitis is more common in children and rarely has an adult onset. Often, there is a personal or family history of asthma or allergies. Distribution in adults is more typically on flexure surfaces, hands, and upper eyelids, and it is itchier than perioral dermatitis.

- Rosacea is often associated with flushing, and is exacerbated by the ingestion of hot food and drinks, alcohol (red wine), and exposure to sun. The distribution is typically on the forehead, cheeks, nose, and around the eyes—rather than around the mouth.

A rash that’s painful and mildly itchy

Perioral dermatitis has distinct clinical features that distinguish it from other facial dermatoses. The rash is classically described as tiny, dry, erythematous papulopustules in a pattern around the mouth, nasolabial folds, and chin, with sparing of the vermilion border.1,2 The clinical course is variable, but is often chronic, with flares. Typically, the rash is only mildly pruritic, but a burning or painful sensation is common. Intolerance to sunlight, drying agents (such as soaps), or irritants (such as cosmetics) is also common.3

Treatment: Discontinue steroids, start antibiotics

If left untreated, perioral dermatitis rarely resolves on its own and will have a fluctuating course, punctuated by flares, that will last for years. The prognosis is excellent, however, once appropriate therapy is instituted; recurrence after treatment is low.5

Cessation of topical steroids is a mainstay of treatment6,7 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B). High-potency topical steroids can cause short-term improvement of the rash; removal will cause short-term worsening of symptoms. It’s best, then, to switch your patient to a less potent steroid, and then gradually discontinue the steroid3 (SOR: C). Doing so can help the patient to avoid a rebound flare and the temptation to restart the steroid for short-term relief.

It’s also a good idea to tell the patient to stop using other causative agents, such as moisturizing creams, blush, foundation, oral contraceptives, and fluorinated toothpaste6 (SOR: C).

Several antibiotic regimens are successful in the treatment of perioral dermatitis. Tetracycline 250 mg twice daily, minocycline 100 mg daily, or doxycycline 100 mg daily for 2 to 3 weeks is the initial treatment. The treatment course may last up to 6 weeks8 (SOR: B). For children, pregnant women, or patients with allergies to certain antibiotics, erythromycin 250 mg twice daily for up to 6 weeks is also an option7 (SOR: C).

Topical treatments can also be used, but often take longer and have been shown to be less effective than oral therapies. Metronidazole 0.75% gel applied twice daily for 14 weeks or 1% cream applied twice daily for 8 weeks has been shown to be useful9,10 (SOR: C). Erythromycin 2% gel applied twice daily for several months is also effective7 (SOR: C).

Discontinuing the steroid was a challenge for our patient

We told our patient to discontinue her steroid cream, and we started her on metronidazole gel. She returned with significant worsening of her rash, including swelling and erythema. We therefore prescribed a brief course of prednisone for short-term relief while she was started on oral doxycycline. After 6 weeks of oral doxycycline therapy, her rash resolved. At a 6-month follow-up, the patient had experienced no further recurrence of the rash.

CORRESPONDENCE Marc Babaoff, MD, MAHEC Family Medicine Residency Program, 118 W. T. Weaver Boulevard, Asheville, NC 28804; [email protected]

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 27-year-old Caucasian woman came into our clinic with an erythematous, papulopustular rash on her face. The small papules and pustules formed a confluence around her mouth and on her chin; the vermilion border was spared (FIGURE). The patient said that the rash started as a dry scaly patch on the corner of her mouth, and it spread over the course of a few weeks.

The patient had a history of eczema for which she used mometasone furoate cream. Initially, she thought the rash was a flare-up of her eczema, so she used her steroid cream. After using the cream on her face for a month, the patient reported that the rash continued to worsen and spread. She said that the rash was mildly itchy and that when she opened her mouth, it was moderately painful.

FIGURE

Patient confused rash with eczema flare

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Perioral dermatitis