User login

Sequential bilateral hip deformities

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 10-YEAR-OLD AFRICAN AMERICAN GIRL was brought to our clinic for right anterior thigh pain that she’d had for 3 weeks. She had been playing normally prior to the onset of pain and said she hadn’t experienced any trauma or injury. She was unable to run due to the pain, but continued to walk with a limp. She denied any other joint pain, fevers, rash, or other constitutional symptoms.

The patient, who was overweight and not in any distress, held her right leg in a slight external rotation. There was no asymmetry, deformity, or swelling in her right hip. She was slightly tender to palpation in the area of the right proximal anterior femur. The remainder of the right lower extremity was nontender.

The patient’s active flexion was limited to approximately 90 degrees, secondary to pain. She had marked pain with internal rotation, but none with external rotation. Her neurological exam was normal, with normal sensation throughout her right lower extremity. She had normal dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses.

Plain radiographs of the right hip showed a deformity best noted on the frog leg lateral view (FIGURE 1A). The patient underwent successful in situ pinning of the right hip (FIGURE 1B), had an uncomplicated postoperative course, and returned to her prior level of activity without limitations.

Seven months later, though, the patient came back to the clinic with the same complaints—this time in her left hip—with similar x-ray findings (FIGURE 2A).

FIGURE 1

X-rays before, after pinning

A frog leg lateral view of the patient’s right hip deformity before surgery (A). The patient underwent successful in situ pinning of the hip (B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis

This patient’s radiographic findings (FIGURES 1A and 2A) confirmed that she had experienced sequential bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. SCFE occurs when the femoral head is displaced through the weakened physis, usually medially. Most common in the adolescent years, it is likely caused by the alteration in the plane of the physis during the adolescent growth spurt, in addition to the increased forces of weight gain. Obesity has been shown to be a significant risk factor.1 A small percentage of patients have an underlying endocrine disorder.2,3

FIGURE 2

One hip fixed, trouble in the other

Seven months after surgery on her right hip, the patient sought treatment for her left hip (A) and underwent a second pinning procedure (B).

Differential Dx includes tumors, traumatic injuries

In adolescents who present with hip pain, the differential includes infectious etiologies (eg, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis), tumors, and traumatic injuries (eg, contusions, fractures, epiphyseal injuries). This patient’s characteristic presentation and physical exam raised my suspicion of SCFE. The classic radiographic findings confirmed my suspicion.

Treatment can’t wait

Untreated or delayed treatment of SCFE is associated with significant morbidity, including osteonecrosis, chondrolysis, and chronic pain and deformity. Among patients who experience an initial SCFE, an estimated 30% to 60% will experience a future contralateral slip.4,5

The management of the contralateral hip is controversial. Several studies have explored which patient factors are most predictive of future contralateral slips, and which patients would benefit from prophylactic contralateral pinning. Younger age at presentation—<12 years for girls and <14 years for boys—has been shown to be the most predictive factor of future contralateral slips.6 Other factors, such as race, sex, and skeletal maturity, have not been statistically significant predictors of future slips.6 Older age, in contrast, has been associated with increased slip severity.7

Two studies compared outcomes of observation vs prophylactic in situ pinning after an initial SCFE.8,9 The first showed benefit in the pinning of the contralateral hip,8 while the second study showed optimal benefit in the observation group, except among higher risk patients or patients in whom follow-up was problematic.9

Because of the heightened likelihood of future contralateral SCFE and the significant morbidity associated with delayed treatment, prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip should be considered in patients after an initial SCFE—especially in certain high-risk groups8,9(strength of recommendation: B). Future large, randomized trials with patient-oriented outcomes would be useful.

Clearly, final treatment decisions will involve patient preferences and patient-specific factors including age and comorbidities.

Back on track after 2 surgeries

My patient did well after recovering from her second surgery (FIGURE 2B). I encouraged her to lose weight by eating well and exercising regularly.

The patient followed standard postoperative instructions of nonweight bearing for 6 weeks after each surgery. She returned to her prior functional status and continues to do well.

CORRESPONDENCE: Mark A. McElhannon, MD, Atlanta Medical Center Family Practice Residency, 1000 Corporate Center Drive, Suite 200, Morrow, GA 30260; [email protected]

1. Loder RT. The demographics of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. An international multicenter study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:8-27.

2. Wells D, King JD, Roe TF. Review of slipped capital femoral epiphysis associated with endocrine disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:610-614.

3. Burrow SR, Alman B, Wright JG. Short stature as a screening test for endocrinopathy in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:263-268.

4. Loder RT, Aronson DD, Greenfield ML. The epidemiology of bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A study of children in Michigan. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1141-1147.

5. Hagglund G, Hansson LI, Ordeberg G, et al. Bilaterality in slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:179-181.

6. Riad J, Bajelidze G, Gabos PG. Bilateral slipped capital epiphysis: predictive factors for contralateral slip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:411-414.

7. Loder RT, Starnes T, Dikos G, et al. Demographic predictors of severity of stable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:97-105

8. Schultz WR, Weinstein JN, Weinstein SL, et al. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis; evaluation of long term outcome for the contralateral hip with use of decision analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1305-1314.

9. Kocher MS, Bishop JA, Hresko MT, et al. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip after unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:2658-2665.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 10-YEAR-OLD AFRICAN AMERICAN GIRL was brought to our clinic for right anterior thigh pain that she’d had for 3 weeks. She had been playing normally prior to the onset of pain and said she hadn’t experienced any trauma or injury. She was unable to run due to the pain, but continued to walk with a limp. She denied any other joint pain, fevers, rash, or other constitutional symptoms.

The patient, who was overweight and not in any distress, held her right leg in a slight external rotation. There was no asymmetry, deformity, or swelling in her right hip. She was slightly tender to palpation in the area of the right proximal anterior femur. The remainder of the right lower extremity was nontender.

The patient’s active flexion was limited to approximately 90 degrees, secondary to pain. She had marked pain with internal rotation, but none with external rotation. Her neurological exam was normal, with normal sensation throughout her right lower extremity. She had normal dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses.

Plain radiographs of the right hip showed a deformity best noted on the frog leg lateral view (FIGURE 1A). The patient underwent successful in situ pinning of the right hip (FIGURE 1B), had an uncomplicated postoperative course, and returned to her prior level of activity without limitations.

Seven months later, though, the patient came back to the clinic with the same complaints—this time in her left hip—with similar x-ray findings (FIGURE 2A).

FIGURE 1

X-rays before, after pinning

A frog leg lateral view of the patient’s right hip deformity before surgery (A). The patient underwent successful in situ pinning of the hip (B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis

This patient’s radiographic findings (FIGURES 1A and 2A) confirmed that she had experienced sequential bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. SCFE occurs when the femoral head is displaced through the weakened physis, usually medially. Most common in the adolescent years, it is likely caused by the alteration in the plane of the physis during the adolescent growth spurt, in addition to the increased forces of weight gain. Obesity has been shown to be a significant risk factor.1 A small percentage of patients have an underlying endocrine disorder.2,3

FIGURE 2

One hip fixed, trouble in the other

Seven months after surgery on her right hip, the patient sought treatment for her left hip (A) and underwent a second pinning procedure (B).

Differential Dx includes tumors, traumatic injuries

In adolescents who present with hip pain, the differential includes infectious etiologies (eg, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis), tumors, and traumatic injuries (eg, contusions, fractures, epiphyseal injuries). This patient’s characteristic presentation and physical exam raised my suspicion of SCFE. The classic radiographic findings confirmed my suspicion.

Treatment can’t wait

Untreated or delayed treatment of SCFE is associated with significant morbidity, including osteonecrosis, chondrolysis, and chronic pain and deformity. Among patients who experience an initial SCFE, an estimated 30% to 60% will experience a future contralateral slip.4,5

The management of the contralateral hip is controversial. Several studies have explored which patient factors are most predictive of future contralateral slips, and which patients would benefit from prophylactic contralateral pinning. Younger age at presentation—<12 years for girls and <14 years for boys—has been shown to be the most predictive factor of future contralateral slips.6 Other factors, such as race, sex, and skeletal maturity, have not been statistically significant predictors of future slips.6 Older age, in contrast, has been associated with increased slip severity.7

Two studies compared outcomes of observation vs prophylactic in situ pinning after an initial SCFE.8,9 The first showed benefit in the pinning of the contralateral hip,8 while the second study showed optimal benefit in the observation group, except among higher risk patients or patients in whom follow-up was problematic.9

Because of the heightened likelihood of future contralateral SCFE and the significant morbidity associated with delayed treatment, prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip should be considered in patients after an initial SCFE—especially in certain high-risk groups8,9(strength of recommendation: B). Future large, randomized trials with patient-oriented outcomes would be useful.

Clearly, final treatment decisions will involve patient preferences and patient-specific factors including age and comorbidities.

Back on track after 2 surgeries

My patient did well after recovering from her second surgery (FIGURE 2B). I encouraged her to lose weight by eating well and exercising regularly.

The patient followed standard postoperative instructions of nonweight bearing for 6 weeks after each surgery. She returned to her prior functional status and continues to do well.

CORRESPONDENCE: Mark A. McElhannon, MD, Atlanta Medical Center Family Practice Residency, 1000 Corporate Center Drive, Suite 200, Morrow, GA 30260; [email protected]

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 10-YEAR-OLD AFRICAN AMERICAN GIRL was brought to our clinic for right anterior thigh pain that she’d had for 3 weeks. She had been playing normally prior to the onset of pain and said she hadn’t experienced any trauma or injury. She was unable to run due to the pain, but continued to walk with a limp. She denied any other joint pain, fevers, rash, or other constitutional symptoms.

The patient, who was overweight and not in any distress, held her right leg in a slight external rotation. There was no asymmetry, deformity, or swelling in her right hip. She was slightly tender to palpation in the area of the right proximal anterior femur. The remainder of the right lower extremity was nontender.

The patient’s active flexion was limited to approximately 90 degrees, secondary to pain. She had marked pain with internal rotation, but none with external rotation. Her neurological exam was normal, with normal sensation throughout her right lower extremity. She had normal dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses.

Plain radiographs of the right hip showed a deformity best noted on the frog leg lateral view (FIGURE 1A). The patient underwent successful in situ pinning of the right hip (FIGURE 1B), had an uncomplicated postoperative course, and returned to her prior level of activity without limitations.

Seven months later, though, the patient came back to the clinic with the same complaints—this time in her left hip—with similar x-ray findings (FIGURE 2A).

FIGURE 1

X-rays before, after pinning

A frog leg lateral view of the patient’s right hip deformity before surgery (A). The patient underwent successful in situ pinning of the hip (B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis

This patient’s radiographic findings (FIGURES 1A and 2A) confirmed that she had experienced sequential bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. SCFE occurs when the femoral head is displaced through the weakened physis, usually medially. Most common in the adolescent years, it is likely caused by the alteration in the plane of the physis during the adolescent growth spurt, in addition to the increased forces of weight gain. Obesity has been shown to be a significant risk factor.1 A small percentage of patients have an underlying endocrine disorder.2,3

FIGURE 2

One hip fixed, trouble in the other

Seven months after surgery on her right hip, the patient sought treatment for her left hip (A) and underwent a second pinning procedure (B).

Differential Dx includes tumors, traumatic injuries

In adolescents who present with hip pain, the differential includes infectious etiologies (eg, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis), tumors, and traumatic injuries (eg, contusions, fractures, epiphyseal injuries). This patient’s characteristic presentation and physical exam raised my suspicion of SCFE. The classic radiographic findings confirmed my suspicion.

Treatment can’t wait

Untreated or delayed treatment of SCFE is associated with significant morbidity, including osteonecrosis, chondrolysis, and chronic pain and deformity. Among patients who experience an initial SCFE, an estimated 30% to 60% will experience a future contralateral slip.4,5

The management of the contralateral hip is controversial. Several studies have explored which patient factors are most predictive of future contralateral slips, and which patients would benefit from prophylactic contralateral pinning. Younger age at presentation—<12 years for girls and <14 years for boys—has been shown to be the most predictive factor of future contralateral slips.6 Other factors, such as race, sex, and skeletal maturity, have not been statistically significant predictors of future slips.6 Older age, in contrast, has been associated with increased slip severity.7

Two studies compared outcomes of observation vs prophylactic in situ pinning after an initial SCFE.8,9 The first showed benefit in the pinning of the contralateral hip,8 while the second study showed optimal benefit in the observation group, except among higher risk patients or patients in whom follow-up was problematic.9

Because of the heightened likelihood of future contralateral SCFE and the significant morbidity associated with delayed treatment, prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip should be considered in patients after an initial SCFE—especially in certain high-risk groups8,9(strength of recommendation: B). Future large, randomized trials with patient-oriented outcomes would be useful.

Clearly, final treatment decisions will involve patient preferences and patient-specific factors including age and comorbidities.

Back on track after 2 surgeries

My patient did well after recovering from her second surgery (FIGURE 2B). I encouraged her to lose weight by eating well and exercising regularly.

The patient followed standard postoperative instructions of nonweight bearing for 6 weeks after each surgery. She returned to her prior functional status and continues to do well.

CORRESPONDENCE: Mark A. McElhannon, MD, Atlanta Medical Center Family Practice Residency, 1000 Corporate Center Drive, Suite 200, Morrow, GA 30260; [email protected]

1. Loder RT. The demographics of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. An international multicenter study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:8-27.

2. Wells D, King JD, Roe TF. Review of slipped capital femoral epiphysis associated with endocrine disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:610-614.

3. Burrow SR, Alman B, Wright JG. Short stature as a screening test for endocrinopathy in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:263-268.

4. Loder RT, Aronson DD, Greenfield ML. The epidemiology of bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A study of children in Michigan. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1141-1147.

5. Hagglund G, Hansson LI, Ordeberg G, et al. Bilaterality in slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:179-181.

6. Riad J, Bajelidze G, Gabos PG. Bilateral slipped capital epiphysis: predictive factors for contralateral slip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:411-414.

7. Loder RT, Starnes T, Dikos G, et al. Demographic predictors of severity of stable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:97-105

8. Schultz WR, Weinstein JN, Weinstein SL, et al. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis; evaluation of long term outcome for the contralateral hip with use of decision analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1305-1314.

9. Kocher MS, Bishop JA, Hresko MT, et al. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip after unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:2658-2665.

1. Loder RT. The demographics of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. An international multicenter study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:8-27.

2. Wells D, King JD, Roe TF. Review of slipped capital femoral epiphysis associated with endocrine disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:610-614.

3. Burrow SR, Alman B, Wright JG. Short stature as a screening test for endocrinopathy in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:263-268.

4. Loder RT, Aronson DD, Greenfield ML. The epidemiology of bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A study of children in Michigan. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1141-1147.

5. Hagglund G, Hansson LI, Ordeberg G, et al. Bilaterality in slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:179-181.

6. Riad J, Bajelidze G, Gabos PG. Bilateral slipped capital epiphysis: predictive factors for contralateral slip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:411-414.

7. Loder RT, Starnes T, Dikos G, et al. Demographic predictors of severity of stable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:97-105

8. Schultz WR, Weinstein JN, Weinstein SL, et al. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis; evaluation of long term outcome for the contralateral hip with use of decision analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1305-1314.

9. Kocher MS, Bishop JA, Hresko MT, et al. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip after unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:2658-2665.

Surprising finding on colonoscopy

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD MAN went to his primary care physician for his annual physical. He told his physician that for the past few years, he had intermittent, painless rectal bleeding consisting of small amounts of blood on the toilet paper after defecation. He also mentioned that he often spontaneously awoke, very early in the morning. His past medical history was unremarkable.

The patient was born in Cuba but had lived in the United States for more than 30 years. He was divorced, lived alone, and had no children. He had traveled to Latin America—including Mexico, Brazil, and Cuba—off and on over the past 10 years. His last trip was approximately 2 years ago.

His physical exam was unremarkable. Rectal examination revealed no masses or external hemorrhoids; stool was brown and Hemoccult negative. Labs were remarkable for eosinophilia ranging from 10% to 24% over the past several years (the white blood cell count ranged from 5200 to 5900/mcL).

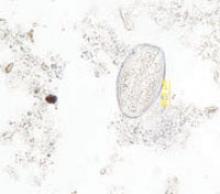

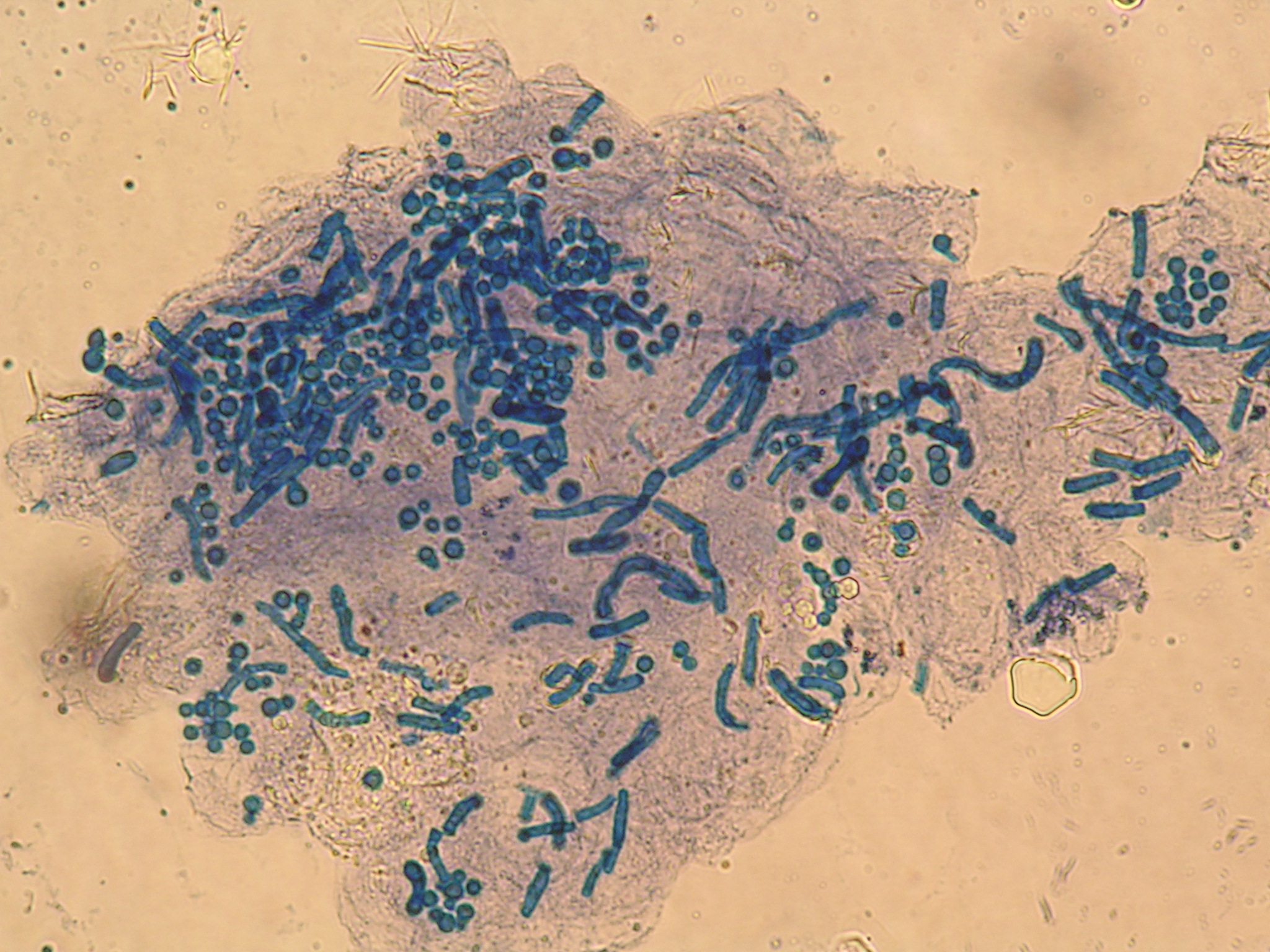

A subsequent colonoscopy revealed many white, thin, motile organisms dispersed throughout the colon (FIGURE 1). The organisms were most densely populated in the cecum. Of note, the patient also had nonbleeding internal hemorrhoids. An aspiration of the organisms was obtained and sent to the microbiology lab for further evaluation. Wet preparation microscopy is shown below (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Motile worms

Multiple motile worms were found on colonoscopy, dispersed throughout the colon. The worms were concentrated in the right colon.

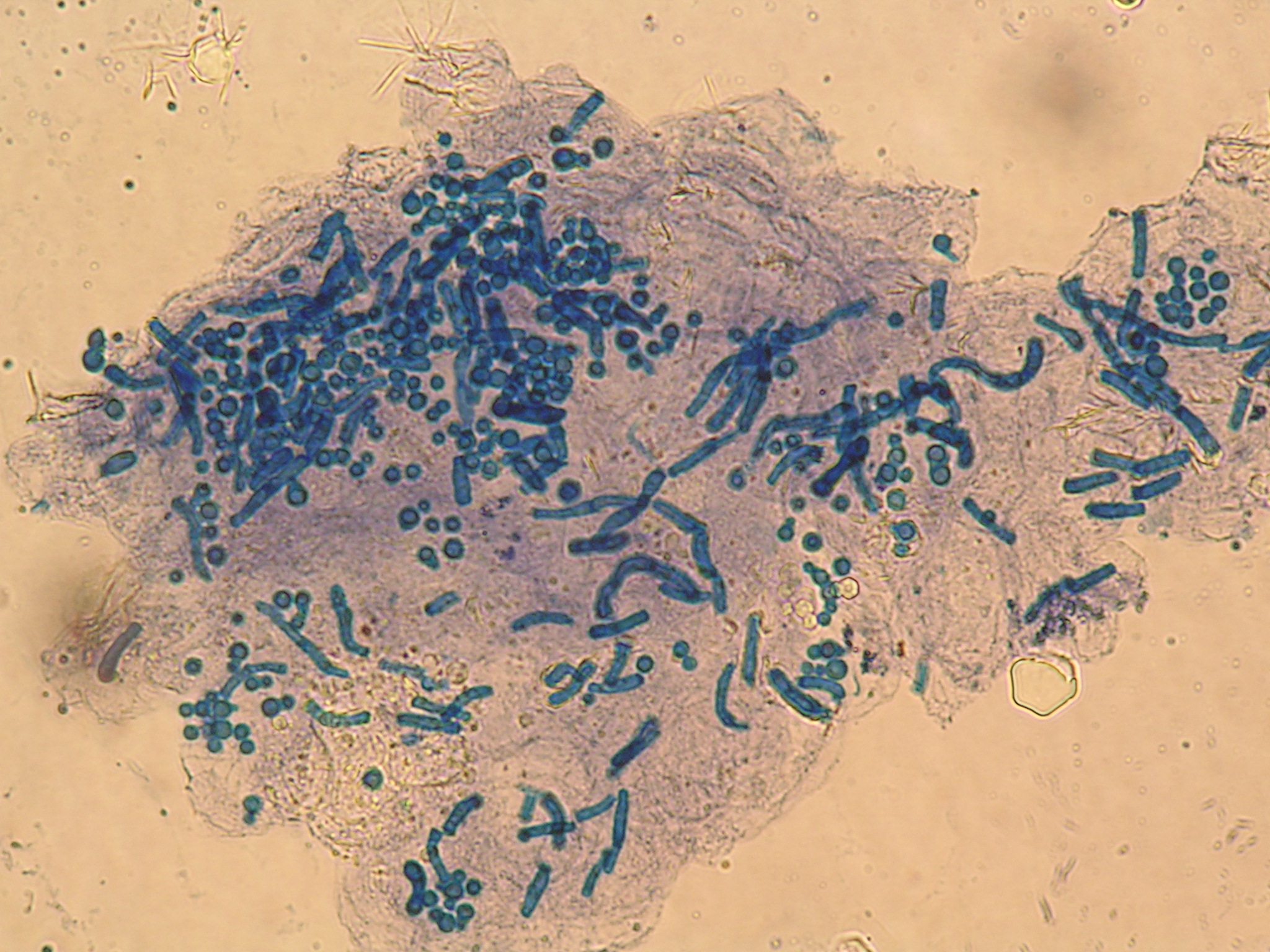

FIGURE 2

Ova

Aspiration on colonoscopy revealed football-shaped eggs that were flat on one side.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Enterobiasis

The colonoscopy and aspiration results revealed Enterobius vermicularis, or pinworm infection. E vermicularis is the most common intestinal parasite seen by primary care physicians in North America and has a wide geographic distribution.1 In the United States, more than 40 million people are estimated to be infected with pinworm, and up to 30% are children.2 Adult worms are not commonly found on colonoscopy, in part because endoscopists are not anticipating them.3

Upon further questioning after the colonoscopy, our patient reported having “worms” as a child and being treated for them. He denied recent symptoms of perianal itching. He also denied a recent history of contact with children.

Infection is via the fecal-oral route

The life cycle of E vermicularis consists of egg, larvae, and adult worm stages. Infection occurs by the fecal-oral route, with hosts including humans and cockroaches.4

The adult pinworm is very small (females average 10 mm in length; males are 4 mm in length) with a lifespan of 1 to 2 months. Infection begins with ingestion of ova, which hatch in the duodenum. The larvae mature into adult worms as they migrate through the small intestine. The adult worms then reside in the cecum, and occasionally the appendix.

The gravid female worms migrate to the perianal region at night to deposit their eggs, laying about 15,000 eggs at once. This leads to perianal itching. Reinfection occurs by hand-to-mouth transmission of the eggs from perianal scratching.1-3

Differential Dx: Roundworms, whipworms, and threadworms

Other common parasitic helminthes in the United States include Ascaris lumbricoides (roundworm) and Trichuris trichiura (whipworm). Strongyloides stercoralis (thread worm) and Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale (hookworms) are less common here but should be considered in immigrants, such as our patient. Tapeworms are another parasitic helminth, but tend to be flat in appearance, unlike the worms in this case.

Roundworms are the largest of the parasitic helminthes listed here, and are common in the southeastern states’ rural population. Larvae penetrate the intestine, enter the lymphatics, and travel to the lungs. Here they may cause Loffler’s pneumonia, which is usually self-limited (lasting 1-2 weeks) and often goes undiagnosed. Juvenile worms are coughed up and swallowed, returning to the small intestine, where they mature and survive for 12 to 18 months.1

The whipworm is found in the southeastern states, but is more common in immigrants and migrant workers. A portion of the helminth burrows into the intestinal wall and may cause mild anemia, diarrhea, symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease, or rectal prolapse.1

Threadworms are prevalent throughout the tropical eastern hemisphere and are most commonly found in immigrants. Larvae penetrate the skin, migrate through the bloodstream to the lungs, and are coughed up and swallowed. The filariform stage penetrates the anal skin or intestinal mucosa, perpetuating infection, which may persist for 40 years—long after the patient has immigrated. Clinical presentation includes pruritus ani, pneumonia, abdominal cramping, and colitis.1

Hookworms have a similar geographic distribution to the threadworm. Necator americanus is the most prevalent hookworm in the United States, found in the southeast. Like the threadworm, larvae penetrate the skin, usually the feet, causing a rash. They migrate to the lungs, where they are coughed up and swallowed. In the intestines, they consume blood and cause iron deficiency anemia. Other symptoms include fatigue, failure to thrive, and depression. These worms may persist for 15 years.1

Some patients have itching, others are asymptomatic

The classic presentation of pinworm infection includes perianal itching that is worse at night and is associated with sleep disturbances, which our patient experienced. However, the vast majority of patients are asymptomatic, leading to underdiagnosis of the infection.2 This patient’s only complaint was intermittent rectal bleeding, which was likely due to his hemorrhoids.

More common presentations include abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, and diarrhea. However, case reports have described a variety of presentations, some with significant morbidity and mortality, often related to migration of the worms into the genitourinary tract and pelvic cavity.3 These include vulvovaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic abscesses and granulomas, urinary tract infections, prostatitis, epididymitis, appendicitis, enterocolitis, and bowel obstruction.3,5-7Physical exam findings may include perianal excoriation, with or without bacterial superinfection.

The Scotch tape test clinches the diagnosis

The “Scotch tape test” is the most commonly used diagnostic test for pinworm infection. A clinician applies a piece of clear cellulose acetate tape to the unwashed perianal skin in the morning on 3 separate occasions. He or she then applies the tape to glass slides and sends them to the lab.1

The characteristic findings are long, oval, colorless eggs, 50 to 60 micrometers in length, which are flat on one side (FIGURE 2).

The patient’s perianal area may also be examined with a flashlight late at night or early in the morning; occasionally glistening adult worms are found. Stool samples are often negative for worms and eggs; thus, stool examination is rarely helpful.

Tx: Antiparasitics for patients and others in household

Patients with pinworm infection are initially treated with 1 dose of oral mebendazole (100 mg), albendazole (400 mg), or pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg, maximum dose 1 g) (strength of recommendation [SOR] B).8-10 Some sources suggest pregnant patients be treated with pyrantel pamoate (a Category C drug in pregnancy), whereas others recommend deferring treatment until after delivery, as harm to the fetus by pinworm infection has not been reported in the literature (SOR C).1,3,11

Regardless of which antiparasitic is used, treatment should be repeated after 10 to 14 days, given the high relapse rate. Repeat treatment is especially important with mebendazole, which is active only against worms—not eggs.

Household members should also be treated, as the infection is readily transmitted and others may have asymptomatic infection (SOR B).1,3,12 In order to prevent reinoculation or spread of the infection, patients should practice good hand hygiene, including trimming their fingernails. The patient and family members should wash all sheets, clothes, and towels. Pets need not be treated, as they cannot serve as reservoirs.1,3

A good outcome. We treated the patient with mebendazole 100 mg once and repeated treatment 10 days later. We taught the patient how to prevent reinfection, and we asked him to follow-up at the clinic, as needed.

1. Juckett G. Common intestinal helminths. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52:2039-2041.

2. Weller PF, Nutman TB. Intestinal nematodes. In: Kasper Dl, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:1259.

3. Petro M, Iavu K, Minocha A. Unusual endoscopic and microscopic view of Enterobius vermicularis: a case report with a review of the literature. South Med J. 2005;98:927-929.

4. Chan OT, Lee EK, Hardman JM, et al. The cockroach as a host for Trichinella and Enterobius vermicularis: implications for public health. Hawaii Med J. 2004;63:74-77.

5. Jardine M, Kokai GK, Dalzell AM. Enterobius vermicularis and colitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:610-612.

6. da Silva DF, da Silva RJ, da Silva MG, et al. Parasitic infection of the appendix as a cause of acute appendicitis. Parasitol Res. 2007;102:99-102.

7. Zahariou A, Karamouti M, Papaioannou P. Enterobius vermicularis in the male urinary tract: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:137-Available at: www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/1/1/137. Accessed July 9, 2008.

8. Horton J. Albendazole: a review of antihelmintic efficacy and safety in humans. Parasitology. 2000;121(suppl):S113-S132.

9. St Georgiev V. Chemotherapy of enterobiasis (oxyuriasis). Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:267-275.

10. Jagota SC. Albendazole, a broad-spectrum anthelmintic, in the treatment of intestinal nematode and cestode infection: a multicenter study in 480 patients. Clin Ther. 1986;8:226-231.

11. Hamblin J, Connor PD. Pinworms in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8:321-324.

12. Yang YS, Kim SW, Jung SH, et al. Chemotherapeutic trial to control enterobiasis in schoolchildren. Korean J Parasitol. 1997;35:265-269.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD MAN went to his primary care physician for his annual physical. He told his physician that for the past few years, he had intermittent, painless rectal bleeding consisting of small amounts of blood on the toilet paper after defecation. He also mentioned that he often spontaneously awoke, very early in the morning. His past medical history was unremarkable.

The patient was born in Cuba but had lived in the United States for more than 30 years. He was divorced, lived alone, and had no children. He had traveled to Latin America—including Mexico, Brazil, and Cuba—off and on over the past 10 years. His last trip was approximately 2 years ago.

His physical exam was unremarkable. Rectal examination revealed no masses or external hemorrhoids; stool was brown and Hemoccult negative. Labs were remarkable for eosinophilia ranging from 10% to 24% over the past several years (the white blood cell count ranged from 5200 to 5900/mcL).

A subsequent colonoscopy revealed many white, thin, motile organisms dispersed throughout the colon (FIGURE 1). The organisms were most densely populated in the cecum. Of note, the patient also had nonbleeding internal hemorrhoids. An aspiration of the organisms was obtained and sent to the microbiology lab for further evaluation. Wet preparation microscopy is shown below (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Motile worms

Multiple motile worms were found on colonoscopy, dispersed throughout the colon. The worms were concentrated in the right colon.

FIGURE 2

Ova

Aspiration on colonoscopy revealed football-shaped eggs that were flat on one side.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Enterobiasis

The colonoscopy and aspiration results revealed Enterobius vermicularis, or pinworm infection. E vermicularis is the most common intestinal parasite seen by primary care physicians in North America and has a wide geographic distribution.1 In the United States, more than 40 million people are estimated to be infected with pinworm, and up to 30% are children.2 Adult worms are not commonly found on colonoscopy, in part because endoscopists are not anticipating them.3

Upon further questioning after the colonoscopy, our patient reported having “worms” as a child and being treated for them. He denied recent symptoms of perianal itching. He also denied a recent history of contact with children.

Infection is via the fecal-oral route

The life cycle of E vermicularis consists of egg, larvae, and adult worm stages. Infection occurs by the fecal-oral route, with hosts including humans and cockroaches.4

The adult pinworm is very small (females average 10 mm in length; males are 4 mm in length) with a lifespan of 1 to 2 months. Infection begins with ingestion of ova, which hatch in the duodenum. The larvae mature into adult worms as they migrate through the small intestine. The adult worms then reside in the cecum, and occasionally the appendix.

The gravid female worms migrate to the perianal region at night to deposit their eggs, laying about 15,000 eggs at once. This leads to perianal itching. Reinfection occurs by hand-to-mouth transmission of the eggs from perianal scratching.1-3

Differential Dx: Roundworms, whipworms, and threadworms

Other common parasitic helminthes in the United States include Ascaris lumbricoides (roundworm) and Trichuris trichiura (whipworm). Strongyloides stercoralis (thread worm) and Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale (hookworms) are less common here but should be considered in immigrants, such as our patient. Tapeworms are another parasitic helminth, but tend to be flat in appearance, unlike the worms in this case.

Roundworms are the largest of the parasitic helminthes listed here, and are common in the southeastern states’ rural population. Larvae penetrate the intestine, enter the lymphatics, and travel to the lungs. Here they may cause Loffler’s pneumonia, which is usually self-limited (lasting 1-2 weeks) and often goes undiagnosed. Juvenile worms are coughed up and swallowed, returning to the small intestine, where they mature and survive for 12 to 18 months.1

The whipworm is found in the southeastern states, but is more common in immigrants and migrant workers. A portion of the helminth burrows into the intestinal wall and may cause mild anemia, diarrhea, symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease, or rectal prolapse.1

Threadworms are prevalent throughout the tropical eastern hemisphere and are most commonly found in immigrants. Larvae penetrate the skin, migrate through the bloodstream to the lungs, and are coughed up and swallowed. The filariform stage penetrates the anal skin or intestinal mucosa, perpetuating infection, which may persist for 40 years—long after the patient has immigrated. Clinical presentation includes pruritus ani, pneumonia, abdominal cramping, and colitis.1

Hookworms have a similar geographic distribution to the threadworm. Necator americanus is the most prevalent hookworm in the United States, found in the southeast. Like the threadworm, larvae penetrate the skin, usually the feet, causing a rash. They migrate to the lungs, where they are coughed up and swallowed. In the intestines, they consume blood and cause iron deficiency anemia. Other symptoms include fatigue, failure to thrive, and depression. These worms may persist for 15 years.1

Some patients have itching, others are asymptomatic

The classic presentation of pinworm infection includes perianal itching that is worse at night and is associated with sleep disturbances, which our patient experienced. However, the vast majority of patients are asymptomatic, leading to underdiagnosis of the infection.2 This patient’s only complaint was intermittent rectal bleeding, which was likely due to his hemorrhoids.

More common presentations include abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, and diarrhea. However, case reports have described a variety of presentations, some with significant morbidity and mortality, often related to migration of the worms into the genitourinary tract and pelvic cavity.3 These include vulvovaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic abscesses and granulomas, urinary tract infections, prostatitis, epididymitis, appendicitis, enterocolitis, and bowel obstruction.3,5-7Physical exam findings may include perianal excoriation, with or without bacterial superinfection.

The Scotch tape test clinches the diagnosis

The “Scotch tape test” is the most commonly used diagnostic test for pinworm infection. A clinician applies a piece of clear cellulose acetate tape to the unwashed perianal skin in the morning on 3 separate occasions. He or she then applies the tape to glass slides and sends them to the lab.1

The characteristic findings are long, oval, colorless eggs, 50 to 60 micrometers in length, which are flat on one side (FIGURE 2).

The patient’s perianal area may also be examined with a flashlight late at night or early in the morning; occasionally glistening adult worms are found. Stool samples are often negative for worms and eggs; thus, stool examination is rarely helpful.

Tx: Antiparasitics for patients and others in household

Patients with pinworm infection are initially treated with 1 dose of oral mebendazole (100 mg), albendazole (400 mg), or pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg, maximum dose 1 g) (strength of recommendation [SOR] B).8-10 Some sources suggest pregnant patients be treated with pyrantel pamoate (a Category C drug in pregnancy), whereas others recommend deferring treatment until after delivery, as harm to the fetus by pinworm infection has not been reported in the literature (SOR C).1,3,11

Regardless of which antiparasitic is used, treatment should be repeated after 10 to 14 days, given the high relapse rate. Repeat treatment is especially important with mebendazole, which is active only against worms—not eggs.

Household members should also be treated, as the infection is readily transmitted and others may have asymptomatic infection (SOR B).1,3,12 In order to prevent reinoculation or spread of the infection, patients should practice good hand hygiene, including trimming their fingernails. The patient and family members should wash all sheets, clothes, and towels. Pets need not be treated, as they cannot serve as reservoirs.1,3

A good outcome. We treated the patient with mebendazole 100 mg once and repeated treatment 10 days later. We taught the patient how to prevent reinfection, and we asked him to follow-up at the clinic, as needed.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 48-YEAR-OLD MAN went to his primary care physician for his annual physical. He told his physician that for the past few years, he had intermittent, painless rectal bleeding consisting of small amounts of blood on the toilet paper after defecation. He also mentioned that he often spontaneously awoke, very early in the morning. His past medical history was unremarkable.

The patient was born in Cuba but had lived in the United States for more than 30 years. He was divorced, lived alone, and had no children. He had traveled to Latin America—including Mexico, Brazil, and Cuba—off and on over the past 10 years. His last trip was approximately 2 years ago.

His physical exam was unremarkable. Rectal examination revealed no masses or external hemorrhoids; stool was brown and Hemoccult negative. Labs were remarkable for eosinophilia ranging from 10% to 24% over the past several years (the white blood cell count ranged from 5200 to 5900/mcL).

A subsequent colonoscopy revealed many white, thin, motile organisms dispersed throughout the colon (FIGURE 1). The organisms were most densely populated in the cecum. Of note, the patient also had nonbleeding internal hemorrhoids. An aspiration of the organisms was obtained and sent to the microbiology lab for further evaluation. Wet preparation microscopy is shown below (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 1

Motile worms

Multiple motile worms were found on colonoscopy, dispersed throughout the colon. The worms were concentrated in the right colon.

FIGURE 2

Ova

Aspiration on colonoscopy revealed football-shaped eggs that were flat on one side.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Enterobiasis

The colonoscopy and aspiration results revealed Enterobius vermicularis, or pinworm infection. E vermicularis is the most common intestinal parasite seen by primary care physicians in North America and has a wide geographic distribution.1 In the United States, more than 40 million people are estimated to be infected with pinworm, and up to 30% are children.2 Adult worms are not commonly found on colonoscopy, in part because endoscopists are not anticipating them.3

Upon further questioning after the colonoscopy, our patient reported having “worms” as a child and being treated for them. He denied recent symptoms of perianal itching. He also denied a recent history of contact with children.

Infection is via the fecal-oral route

The life cycle of E vermicularis consists of egg, larvae, and adult worm stages. Infection occurs by the fecal-oral route, with hosts including humans and cockroaches.4

The adult pinworm is very small (females average 10 mm in length; males are 4 mm in length) with a lifespan of 1 to 2 months. Infection begins with ingestion of ova, which hatch in the duodenum. The larvae mature into adult worms as they migrate through the small intestine. The adult worms then reside in the cecum, and occasionally the appendix.

The gravid female worms migrate to the perianal region at night to deposit their eggs, laying about 15,000 eggs at once. This leads to perianal itching. Reinfection occurs by hand-to-mouth transmission of the eggs from perianal scratching.1-3

Differential Dx: Roundworms, whipworms, and threadworms

Other common parasitic helminthes in the United States include Ascaris lumbricoides (roundworm) and Trichuris trichiura (whipworm). Strongyloides stercoralis (thread worm) and Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale (hookworms) are less common here but should be considered in immigrants, such as our patient. Tapeworms are another parasitic helminth, but tend to be flat in appearance, unlike the worms in this case.

Roundworms are the largest of the parasitic helminthes listed here, and are common in the southeastern states’ rural population. Larvae penetrate the intestine, enter the lymphatics, and travel to the lungs. Here they may cause Loffler’s pneumonia, which is usually self-limited (lasting 1-2 weeks) and often goes undiagnosed. Juvenile worms are coughed up and swallowed, returning to the small intestine, where they mature and survive for 12 to 18 months.1

The whipworm is found in the southeastern states, but is more common in immigrants and migrant workers. A portion of the helminth burrows into the intestinal wall and may cause mild anemia, diarrhea, symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease, or rectal prolapse.1

Threadworms are prevalent throughout the tropical eastern hemisphere and are most commonly found in immigrants. Larvae penetrate the skin, migrate through the bloodstream to the lungs, and are coughed up and swallowed. The filariform stage penetrates the anal skin or intestinal mucosa, perpetuating infection, which may persist for 40 years—long after the patient has immigrated. Clinical presentation includes pruritus ani, pneumonia, abdominal cramping, and colitis.1

Hookworms have a similar geographic distribution to the threadworm. Necator americanus is the most prevalent hookworm in the United States, found in the southeast. Like the threadworm, larvae penetrate the skin, usually the feet, causing a rash. They migrate to the lungs, where they are coughed up and swallowed. In the intestines, they consume blood and cause iron deficiency anemia. Other symptoms include fatigue, failure to thrive, and depression. These worms may persist for 15 years.1

Some patients have itching, others are asymptomatic

The classic presentation of pinworm infection includes perianal itching that is worse at night and is associated with sleep disturbances, which our patient experienced. However, the vast majority of patients are asymptomatic, leading to underdiagnosis of the infection.2 This patient’s only complaint was intermittent rectal bleeding, which was likely due to his hemorrhoids.

More common presentations include abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, and diarrhea. However, case reports have described a variety of presentations, some with significant morbidity and mortality, often related to migration of the worms into the genitourinary tract and pelvic cavity.3 These include vulvovaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic abscesses and granulomas, urinary tract infections, prostatitis, epididymitis, appendicitis, enterocolitis, and bowel obstruction.3,5-7Physical exam findings may include perianal excoriation, with or without bacterial superinfection.

The Scotch tape test clinches the diagnosis

The “Scotch tape test” is the most commonly used diagnostic test for pinworm infection. A clinician applies a piece of clear cellulose acetate tape to the unwashed perianal skin in the morning on 3 separate occasions. He or she then applies the tape to glass slides and sends them to the lab.1

The characteristic findings are long, oval, colorless eggs, 50 to 60 micrometers in length, which are flat on one side (FIGURE 2).

The patient’s perianal area may also be examined with a flashlight late at night or early in the morning; occasionally glistening adult worms are found. Stool samples are often negative for worms and eggs; thus, stool examination is rarely helpful.

Tx: Antiparasitics for patients and others in household

Patients with pinworm infection are initially treated with 1 dose of oral mebendazole (100 mg), albendazole (400 mg), or pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg, maximum dose 1 g) (strength of recommendation [SOR] B).8-10 Some sources suggest pregnant patients be treated with pyrantel pamoate (a Category C drug in pregnancy), whereas others recommend deferring treatment until after delivery, as harm to the fetus by pinworm infection has not been reported in the literature (SOR C).1,3,11

Regardless of which antiparasitic is used, treatment should be repeated after 10 to 14 days, given the high relapse rate. Repeat treatment is especially important with mebendazole, which is active only against worms—not eggs.

Household members should also be treated, as the infection is readily transmitted and others may have asymptomatic infection (SOR B).1,3,12 In order to prevent reinoculation or spread of the infection, patients should practice good hand hygiene, including trimming their fingernails. The patient and family members should wash all sheets, clothes, and towels. Pets need not be treated, as they cannot serve as reservoirs.1,3

A good outcome. We treated the patient with mebendazole 100 mg once and repeated treatment 10 days later. We taught the patient how to prevent reinfection, and we asked him to follow-up at the clinic, as needed.

1. Juckett G. Common intestinal helminths. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52:2039-2041.

2. Weller PF, Nutman TB. Intestinal nematodes. In: Kasper Dl, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:1259.

3. Petro M, Iavu K, Minocha A. Unusual endoscopic and microscopic view of Enterobius vermicularis: a case report with a review of the literature. South Med J. 2005;98:927-929.

4. Chan OT, Lee EK, Hardman JM, et al. The cockroach as a host for Trichinella and Enterobius vermicularis: implications for public health. Hawaii Med J. 2004;63:74-77.

5. Jardine M, Kokai GK, Dalzell AM. Enterobius vermicularis and colitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:610-612.

6. da Silva DF, da Silva RJ, da Silva MG, et al. Parasitic infection of the appendix as a cause of acute appendicitis. Parasitol Res. 2007;102:99-102.

7. Zahariou A, Karamouti M, Papaioannou P. Enterobius vermicularis in the male urinary tract: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:137-Available at: www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/1/1/137. Accessed July 9, 2008.

8. Horton J. Albendazole: a review of antihelmintic efficacy and safety in humans. Parasitology. 2000;121(suppl):S113-S132.

9. St Georgiev V. Chemotherapy of enterobiasis (oxyuriasis). Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:267-275.

10. Jagota SC. Albendazole, a broad-spectrum anthelmintic, in the treatment of intestinal nematode and cestode infection: a multicenter study in 480 patients. Clin Ther. 1986;8:226-231.

11. Hamblin J, Connor PD. Pinworms in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8:321-324.

12. Yang YS, Kim SW, Jung SH, et al. Chemotherapeutic trial to control enterobiasis in schoolchildren. Korean J Parasitol. 1997;35:265-269.

1. Juckett G. Common intestinal helminths. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52:2039-2041.

2. Weller PF, Nutman TB. Intestinal nematodes. In: Kasper Dl, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:1259.

3. Petro M, Iavu K, Minocha A. Unusual endoscopic and microscopic view of Enterobius vermicularis: a case report with a review of the literature. South Med J. 2005;98:927-929.

4. Chan OT, Lee EK, Hardman JM, et al. The cockroach as a host for Trichinella and Enterobius vermicularis: implications for public health. Hawaii Med J. 2004;63:74-77.

5. Jardine M, Kokai GK, Dalzell AM. Enterobius vermicularis and colitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:610-612.

6. da Silva DF, da Silva RJ, da Silva MG, et al. Parasitic infection of the appendix as a cause of acute appendicitis. Parasitol Res. 2007;102:99-102.

7. Zahariou A, Karamouti M, Papaioannou P. Enterobius vermicularis in the male urinary tract: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:137-Available at: www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/1/1/137. Accessed July 9, 2008.

8. Horton J. Albendazole: a review of antihelmintic efficacy and safety in humans. Parasitology. 2000;121(suppl):S113-S132.

9. St Georgiev V. Chemotherapy of enterobiasis (oxyuriasis). Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:267-275.

10. Jagota SC. Albendazole, a broad-spectrum anthelmintic, in the treatment of intestinal nematode and cestode infection: a multicenter study in 480 patients. Clin Ther. 1986;8:226-231.

11. Hamblin J, Connor PD. Pinworms in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8:321-324.

12. Yang YS, Kim SW, Jung SH, et al. Chemotherapeutic trial to control enterobiasis in schoolchildren. Korean J Parasitol. 1997;35:265-269.

Itchy rash on hand

The physician diagnosed lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). LSC is more common in females than in males, with the highest prevalence in individuals between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

The treatment for LSC is mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. If pruritus is bad at night, oral sedating antihistamines can be added in the evening. If the patient acknowledges that stress is a factor, obtain a psychosocial history and offer the patient treatment for any problems uncovered.

Patients need to minimize touching, scratching, and rubbing of the affected areas. It’s important to help patients understand that they are unintentionally hurting their own skin. Suggest that patients gently apply their medication or a moisturizer instead of scratching the pruritic areas. Also advise patients that post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation can take months to resolve and may not resolve fully.

The patient in this case was treated with topical clobetasol ointment and received patient education; her LSC healed well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Self-inflicted dermatoses. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:603-608.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The physician diagnosed lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). LSC is more common in females than in males, with the highest prevalence in individuals between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

The treatment for LSC is mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. If pruritus is bad at night, oral sedating antihistamines can be added in the evening. If the patient acknowledges that stress is a factor, obtain a psychosocial history and offer the patient treatment for any problems uncovered.

Patients need to minimize touching, scratching, and rubbing of the affected areas. It’s important to help patients understand that they are unintentionally hurting their own skin. Suggest that patients gently apply their medication or a moisturizer instead of scratching the pruritic areas. Also advise patients that post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation can take months to resolve and may not resolve fully.

The patient in this case was treated with topical clobetasol ointment and received patient education; her LSC healed well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Self-inflicted dermatoses. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:603-608.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The physician diagnosed lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). LSC is more common in females than in males, with the highest prevalence in individuals between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

The treatment for LSC is mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. If pruritus is bad at night, oral sedating antihistamines can be added in the evening. If the patient acknowledges that stress is a factor, obtain a psychosocial history and offer the patient treatment for any problems uncovered.

Patients need to minimize touching, scratching, and rubbing of the affected areas. It’s important to help patients understand that they are unintentionally hurting their own skin. Suggest that patients gently apply their medication or a moisturizer instead of scratching the pruritic areas. Also advise patients that post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation can take months to resolve and may not resolve fully.

The patient in this case was treated with topical clobetasol ointment and received patient education; her LSC healed well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Self-inflicted dermatoses. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:603-608.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Itchy tattoo

The physician diagnosed an allergic reaction to the red dye in his tattoo. While the reaction to the red dye made the Devil’s face look more “devilish,” (not a bad thing in the patient’s mind), the patient wanted relief from his symptoms. The physician prescribed topical clobetasol, a high-potency steroid, but there was no improvement.

At the next visit the physician recommended intralesional steroid injections. The physician injected triamcinolone 5 mg/cc with a 27-gauge needle. The erythema and swelling improved and the patient returned for more injections. After 3 rounds of injections, the erythema and swelling disappeared.

The patient indicated that this would be his last tattoo.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine, R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:591-596.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The physician diagnosed an allergic reaction to the red dye in his tattoo. While the reaction to the red dye made the Devil’s face look more “devilish,” (not a bad thing in the patient’s mind), the patient wanted relief from his symptoms. The physician prescribed topical clobetasol, a high-potency steroid, but there was no improvement.

At the next visit the physician recommended intralesional steroid injections. The physician injected triamcinolone 5 mg/cc with a 27-gauge needle. The erythema and swelling improved and the patient returned for more injections. After 3 rounds of injections, the erythema and swelling disappeared.

The patient indicated that this would be his last tattoo.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine, R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:591-596.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The physician diagnosed an allergic reaction to the red dye in his tattoo. While the reaction to the red dye made the Devil’s face look more “devilish,” (not a bad thing in the patient’s mind), the patient wanted relief from his symptoms. The physician prescribed topical clobetasol, a high-potency steroid, but there was no improvement.

At the next visit the physician recommended intralesional steroid injections. The physician injected triamcinolone 5 mg/cc with a 27-gauge needle. The erythema and swelling improved and the patient returned for more injections. After 3 rounds of injections, the erythema and swelling disappeared.

The patient indicated that this would be his last tattoo.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine, R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:591-596.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Elbow nodules

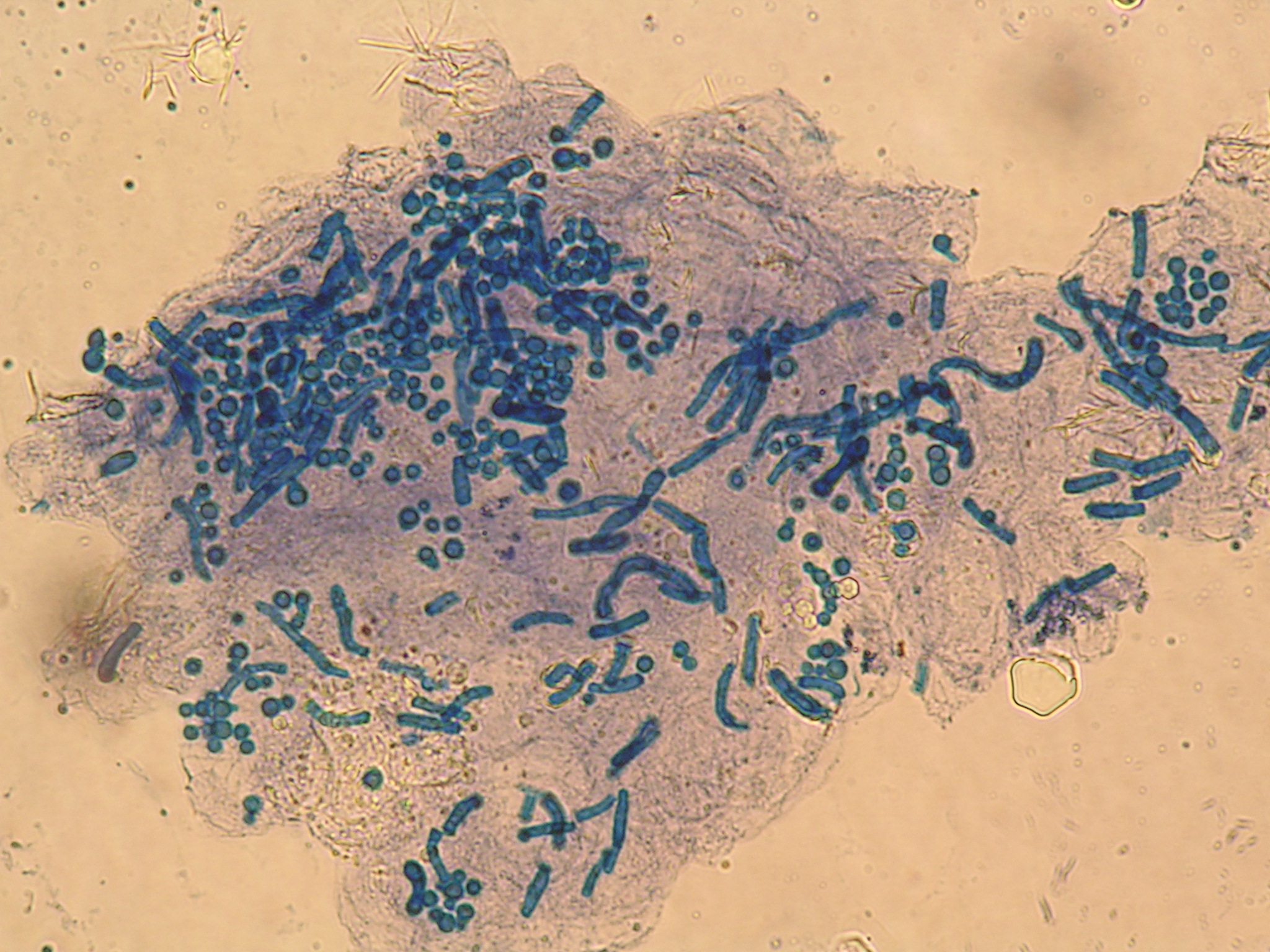

A 42-year-old woman came to our clinic to have lumps on her right elbow removed. She said the lumps did not bother her, but on further questioning, admitted that her fingers turned white when they were exposed to the cold. She had frequent heartburn, but denied fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia, diarrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, muscle weakness, or digital pain.

On physical exam, there were multiple small, firm subcutaneous nodules—some with a white surface protruding through the skin of her right elbow (FIGURE 1A). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation. On further examination we noted tight, smooth skin on her fingers (FIGURE 1B). Her right thumb was fixed in an extended position (FIGURE 2). There were also small blood vessels on her hands and pitted scars on her fingertips.

FIGURE 1

Elbow nodules and clubbing of the fingers

The 42-year-old patient sought care at the clinic to have slightly tender nodules removed from her right elbow. The patient also had tight skin and clubbing of the fingers.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 2

Thumb fixed in an extended position

The patient had tight skin on her fingers and a pitted scar on her thumb, which was fixed in an extended position.

Diagnosis: CREST syndrome

Our patient had CREST syndrome, a variant of limited systemic scleroderma. CREST syndrome is characterized by Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.

Systemic scleroderma is a chronic auto-immune disease involving sclerotic, vascular, and inflammatory changes of the skin and internal organs. There are 19 new cases per million adults per year, with an estimated annual prevalence of 276 cases per million adults in the United States.1 Scleroderma occurs in women 4.6 times more often than in men; the mean age at diagnosis is 45 years.1 Although the pathogenesis of scleroderma remains unclear, interactions among leukocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts are likely to be central in this disease.2

According to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,3 a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma can be made with either 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria present. The major criterion is symmetric thickening, tightening, and induration of the skin proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal or metacarpal-phalangeal joints. This may affect the whole extremity, trunk, neck, and face. The minor criteria include sclerodactyly, digital pitting scars or a loss of substance from the finger pads, and bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis.

Two forms of scleroderma. To improve sensitivity for milder forms of disease, the condition is often divided into diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc) or limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) (TABLE 1), with CREST syndrome being a variant of the limited form.4 Patients with dSSc usually have a rapid diffuse involvement of the trunk, hands, feet, and face with early internal organ involvement. Patients with lSSc, however, usually have slow skin involvement limited to hands, feet, and face, and delayed systemic involvement, if any.

If CREST syndrome is suspected, it is important to look for its cardinal features. Cutaneous calcinosis usually presents over the bony prominences of knees, elbows, spine, and iliac crests, and may be painful. Patients may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon with triphasic color changes, ie, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor, occurring months to years before sclerosis. Ulcerations at fingertips from Raynaud’s may be evident as pitted scars on physical exam. There is also a nonpitting edema of hands and feet that later progresses into sclerodactyly with tapering of fingers (our patient actually had clubbing). Patients may complain of stiffness of the hands and feet as the sclerosis progresses.

As a result of the edema and fibrosis of the face, patients may lose facial lines and comment that they look younger. Often, they will indicate that they have noticed the appearance of small blood vessels on their face, mouth, or hands. Patients may also complain of gastrointestinal problems such as esophageal reflux, diarrhea, or dysphagia.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of systemic scleroderma4-6

| Diffuse systemic scleroderma | Limited systemic scleroderma (Includes CREST syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fatigue and weight loss or gain | None |

| Vascular | Mild to moderate Raynaud’s phenomenon | Moderate to severe Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Cutaneous | Sclerosis to trunk, arms, and face; rapid progression | Sclerosis to hands or toes and face; slow progression; calcinosis is prominent |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias and deformities, muscle weakness, and tendon friction rubs | Arthralgias |

| Gastrointestinal | GERD, esophageal dysmotility, and malabsorption are common; all may be severe | Mild to moderate GERD and esophageal dysmotility are common; malabsorption is less common |

| Renal | Severe hypertension, and renal infarcts in renal crisis are common | Rare |

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease are common | Uncommon |

| Cardiac | Cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias are common | Uncommon |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | ||

Differential includes morphea and scleromyxedema

A thorough history, physical exam, lab work, and possibly biopsy will help differentiate systemic scleroderma from the possible diagnoses with sclerosis listed below:

- Morphea features a localized, patchy distribution of skin fibrosis. There is no systemic involvement or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

- Mixed connective tissue disease has features of other autoimmune diseases, along with those of scleroderma.

- Eosinophilic fasciitis involves the fascia and muscle on biopsy. There is sparing of the hands.

- Scleromyxedema represents the skin thickening seen in patients with a gammopathy. Raynaud’s phenomenon may also be present.

- Scleredema is associated with diabetes. Skin changes are found mostly on the neck, shoulders, and upper arms. On rare occasions, there is visceral involvement. Raynaud’s phenomenon is not present.

In addition, the differential includes chronic graft-vs-host disease; lichen sclerosis et atrophicus; amyloidosis; porphyria cutanea et tardia; primary Raynaud’s phenomenon; and polyvinyl chloride, bleomycin, or pentazocyine exposure.

Nailfold capillary abnormalities help with the diagnosis

As noted earlier, diagnosing systemic scleroderma hinges on taking a good history, doing a thorough physical exam, applying the ACR diagnostic criteria, and ordering lab work. The sensitivity of the ACR criteria increases from 67% to 99% with the addition of nailfold capillary abnormalities (telangiectasias), identified using a dermatoscope.5

The initial lab work that you should consider includes an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, complete blood count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. If the ANA is positive, anticentromere antibody (ACA) and DNA topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody tests should be ordered to see if scleroderma is likely limited or diffuse. ACA will be present in 21% of dSSc and 71% of lSSc cases, whereas Scl-70 will be present in 33% of dSSc and 18% of lSSc cases.6

If the diagnosis is still unclear, do a punch biopsy. Histology in the early phase will show mild cellular infiltrates around dermal blood vessels and at the dermal subcutaneous inter-phase, while the later phase will show thickening of dermis with broadening of collagen fibers and hyalinization of blood vessel walls.6 If lung, kidney, heart, or gastrointestinal involvement is suspected based on symptoms or physical exam, you’ll need to do an organ function work-up.

Treatment focuses on organ-specific problems

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of scleroderma, given that the exact pathogenesis remains unclear and the disease course varies from patient to patient. Pharmacologic therapy is focused on symptoms and organ-specific problems (TABLE 2). Prazosin 1 to 3 mg TID is moderately effective in treating Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to scleroderma7 (SOR: A). Losartan has been reported to reduce the frequency and severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon compared with a low dose of nifedepine,8 in a nonblinded randomized controlled trial (SOR: B). For interstitial lung disease, cyclophosphamide has been found to modestly reduce dyspnea while improving lung function, but it requires close monitoring9 (SOR: A). Bosentan is approved for symptomatic pulmonary hypertension and has been shown to decrease the occurrence of digital ulcers secondary to Raynaud’s phenomenon10 (SOR: A). (Bosentan is available in the United States under a special restricted distribution program called the Tracleer Access Program.)

Nonpharmacologic treatments should also be considered in the management of scleroderma. Advise patients that Raynaud’s phenomenon may be improved by avoiding exposure to the cold and by not smoking (SOR: C). Cutaneous ulcers can be protected with an occlusive dressing and treated with antibiotics if infected (SOR: C). To remove painful calcinotic nodules or release contractures secondary to sclerosis that may limit movement, you may want to consider surgery for your patient11 (SOR: C). If aesthetically unappealing, telangiectasias may be removed with electrosurgery or laser therapy (SOR: C).

Prognosis for scleroderma varies, depending on whether it is diffuse or limited. One large study found that patients with lSSc had a 10-year survival rate of 71%, compared with 21% for patients with dSSc (SOR: B).4 Patients with systemic sclerosis should be monitored for interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, and cardiomyopathy (SOR: C). Prognosis worsens with renal, pulmonary, or cardiac involvement; pulmonary disease is the leading cause of death in dSSc.1

TABLE 2

Medical treatment of systemic scleroderma5-9

| Organ-specific problem/symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Nifedipine, verapamil, losartan, iloprost, prazosin, bosentan* |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Bosentan,* iloprost, captopril, enalapril, sildenafil |

| Interstitial lung disease | Cyclophosphamide, prednisone |

| Cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias | Antiarrhythmics, diuretics, digoxin, pacemaker, transplant |

| Renal failure or crisis | Captopril, kidney dialysis, transplant |

| Skin fibrosis | Methotrexate, cyclosporine, D-penicillamine |

| Arthralgias | Ibuprofen, acetaminophen |

| GERD, gastroparesis, diarrhea | H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, antibiotics |

| Pruritus | Antihistamines, low-dose topical steroids |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | |

| *Restricted access in the United States. | |

Our patient has a change of heart

Our patient had all the cardinal features of CREST syndrome on history and physical exam. She had an ANA of 1:640 with speckled pattern and ACA and Scl-70 were negative, demonstrating that diagnosis must be made in clinical context and not just based on lab markers. We treated her GERD with lifestyle changes and a proton pump inhibitor. We explained the risks and benefits of cutting out her calcinosis nodules and she chose not to have surgery.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Diaz, MD, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, Mail #7816, San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected]

1. Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Deemer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246-2255.

2. Hasegawa M, Sato S. The roles of chemokines in leukocyte recruitment in systemic sclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3637-3647.

3. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590.

4. Barnett AJ, Miller MH, Littlejohn GO. A survival study of patients with scleroderma diagnosed over 30 years (1953-1983): the value of a simple cutaneous classification in the early stages of disease. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:276-283.

5. Hudson M, Taillerfer S, Steele R, et al. Improving sensitivity of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:754-757.

6. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

7. Harding SE, Tingey PC, Pope J, et al. Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(2):CD000956.-

8. Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, et al. Losartan therapy for Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2646-2655.

9. Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements P, et al. For the Scleroderma Lung Study Research Group. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655-2666.

10. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelial receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3884-3995.

11. Melone CP, Jr, McLoughlin JC, Beldner S. Surgical management of the hand in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:514-520.

A 42-year-old woman came to our clinic to have lumps on her right elbow removed. She said the lumps did not bother her, but on further questioning, admitted that her fingers turned white when they were exposed to the cold. She had frequent heartburn, but denied fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia, diarrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, muscle weakness, or digital pain.

On physical exam, there were multiple small, firm subcutaneous nodules—some with a white surface protruding through the skin of her right elbow (FIGURE 1A). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation. On further examination we noted tight, smooth skin on her fingers (FIGURE 1B). Her right thumb was fixed in an extended position (FIGURE 2). There were also small blood vessels on her hands and pitted scars on her fingertips.

FIGURE 1

Elbow nodules and clubbing of the fingers

The 42-year-old patient sought care at the clinic to have slightly tender nodules removed from her right elbow. The patient also had tight skin and clubbing of the fingers.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 2

Thumb fixed in an extended position

The patient had tight skin on her fingers and a pitted scar on her thumb, which was fixed in an extended position.

Diagnosis: CREST syndrome

Our patient had CREST syndrome, a variant of limited systemic scleroderma. CREST syndrome is characterized by Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.

Systemic scleroderma is a chronic auto-immune disease involving sclerotic, vascular, and inflammatory changes of the skin and internal organs. There are 19 new cases per million adults per year, with an estimated annual prevalence of 276 cases per million adults in the United States.1 Scleroderma occurs in women 4.6 times more often than in men; the mean age at diagnosis is 45 years.1 Although the pathogenesis of scleroderma remains unclear, interactions among leukocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts are likely to be central in this disease.2

According to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,3 a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma can be made with either 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria present. The major criterion is symmetric thickening, tightening, and induration of the skin proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal or metacarpal-phalangeal joints. This may affect the whole extremity, trunk, neck, and face. The minor criteria include sclerodactyly, digital pitting scars or a loss of substance from the finger pads, and bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis.

Two forms of scleroderma. To improve sensitivity for milder forms of disease, the condition is often divided into diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc) or limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) (TABLE 1), with CREST syndrome being a variant of the limited form.4 Patients with dSSc usually have a rapid diffuse involvement of the trunk, hands, feet, and face with early internal organ involvement. Patients with lSSc, however, usually have slow skin involvement limited to hands, feet, and face, and delayed systemic involvement, if any.

If CREST syndrome is suspected, it is important to look for its cardinal features. Cutaneous calcinosis usually presents over the bony prominences of knees, elbows, spine, and iliac crests, and may be painful. Patients may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon with triphasic color changes, ie, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor, occurring months to years before sclerosis. Ulcerations at fingertips from Raynaud’s may be evident as pitted scars on physical exam. There is also a nonpitting edema of hands and feet that later progresses into sclerodactyly with tapering of fingers (our patient actually had clubbing). Patients may complain of stiffness of the hands and feet as the sclerosis progresses.

As a result of the edema and fibrosis of the face, patients may lose facial lines and comment that they look younger. Often, they will indicate that they have noticed the appearance of small blood vessels on their face, mouth, or hands. Patients may also complain of gastrointestinal problems such as esophageal reflux, diarrhea, or dysphagia.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of systemic scleroderma4-6

| Diffuse systemic scleroderma | Limited systemic scleroderma (Includes CREST syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fatigue and weight loss or gain | None |

| Vascular | Mild to moderate Raynaud’s phenomenon | Moderate to severe Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Cutaneous | Sclerosis to trunk, arms, and face; rapid progression | Sclerosis to hands or toes and face; slow progression; calcinosis is prominent |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias and deformities, muscle weakness, and tendon friction rubs | Arthralgias |