User login

USPSTF recommendations: A 2017 roundup

Since the last Practice Alert update on the United States Preventive Services Task Force in May of 2016,1 the Task Force has released 19 recommendations on 13 topics that include: the use of aspirin and statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD); support for breastfeeding; use of folic acid during pregnancy; and screening for syphilis, latent tuberculosis (TB), herpes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), colorectal cancer (CRC), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), celiac disease, and skin cancer. The Task Force also released a draft recommendation regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (see “A change for prostate cancer screening?”) and addressed screening pelvic examinations in asymptomatic women, the subject of this month’s audiocast. (To listen, go to: http://bit.ly/2nIVoD5.)

Recommendations to implement

Recommendations from the past year that family physicians should put into practice are detailed below and in TABLE 1.2-8

CRC: Screen all individuals ages 50 to 75, but 76 to 85 selectively. The Task Force reaffirmed its 2008 finding that screening for CRC in adults ages 50 to 75 years is substantially beneficial.2 In contrast to the previous recommendation, however, the new one does not state which screening tests are preferred. The tests considered were 3 stool tests (fecal immunochemical test [FIT], FIT-tumor DNA testing [FIT-DNA], and guaiac-based fecal occult blood test [gFOBT]), as well as 3 direct visualization tests (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and CT colonoscopy). The Task Force assessed various testing frequencies of each test and some test combinations. While the Task Force does not recommend any one screening strategy, there are still significant unknowns about FIT-DNA and CT colonoscopy. The American Academy of Family Physicians does not recommend using these 2 tests for screening purposes at this time.9

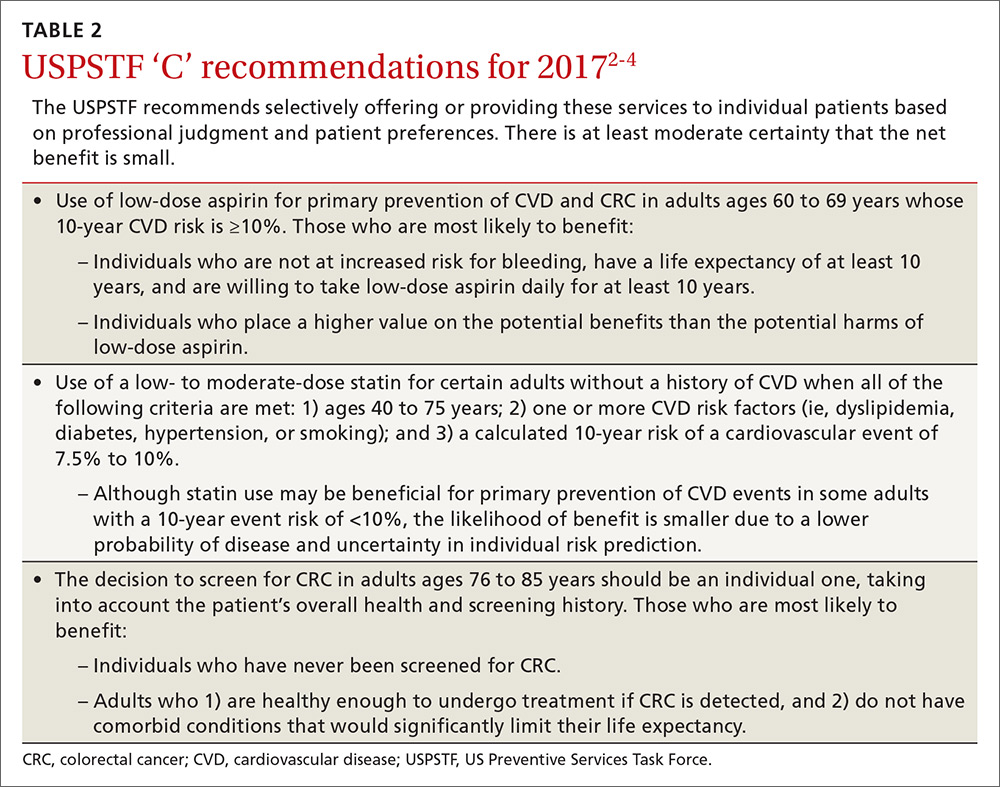

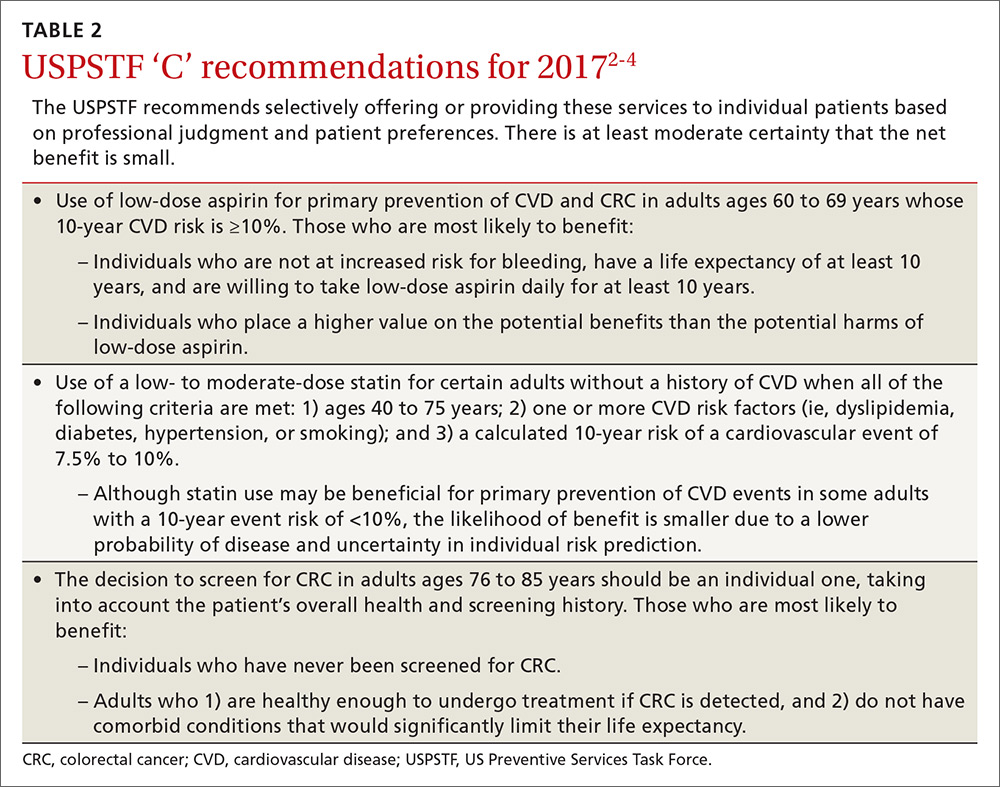

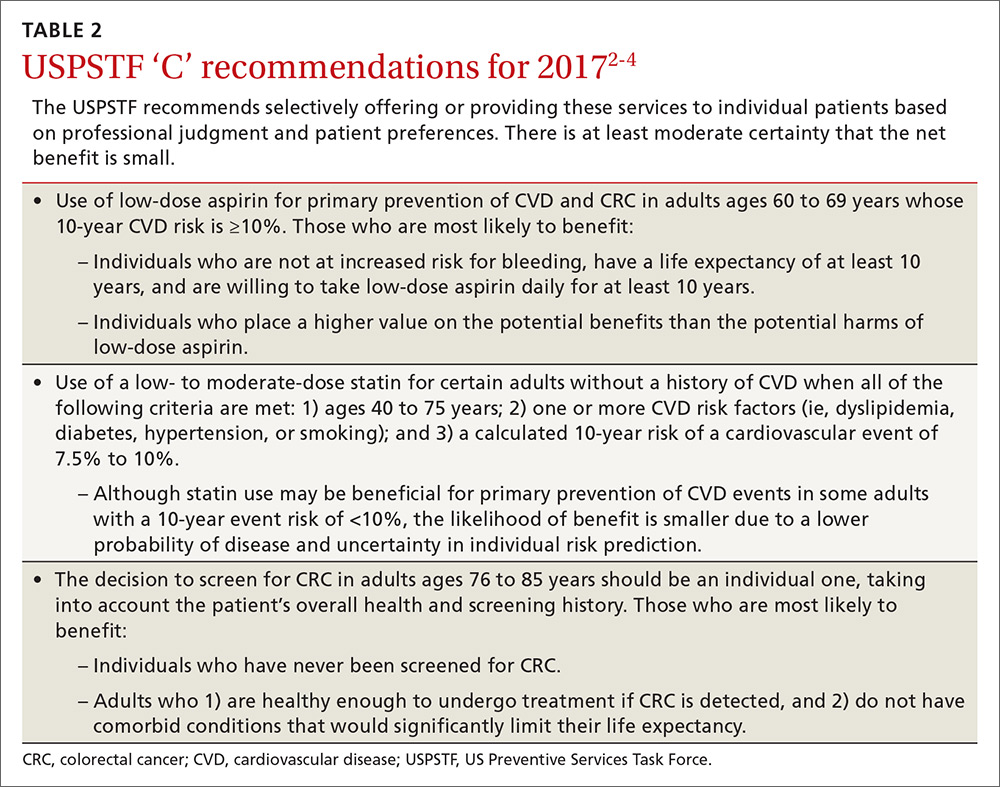

CRC screening for adults ages 76 to 85 was given a “C” recommendation, which means the value of the service to the population overall is small, but that certain individuals may benefit from it. The Task Force advises selectively offering a “C” service to individuals based on professional judgment and patient preferences. Regarding CRC screening in individuals 76 years or older, the ones most likely to benefit are those who have never been screened and those without significant comorbidities that could limit life expectancy. All “C” recommendations from the past year are listed in TABLE 2.2-4

CVD prevention: When aspirin or a statin is indicated. The Task Force released 2 recommendations for the prevention of CVD this past year. One pertained to the use of low-dose aspirin3 (which also helps to prevent CRC), and the other addressed the use of low- to moderate-dose statins.4 Each recommendation is fairly complicated and nuanced in terms of age and risk for CVD. A decision to use low-dose aspirin must also consider the risk of bleeding.

To calculate a patient’s risk for CVD, the Task Force recommends using the risk calculator developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/).

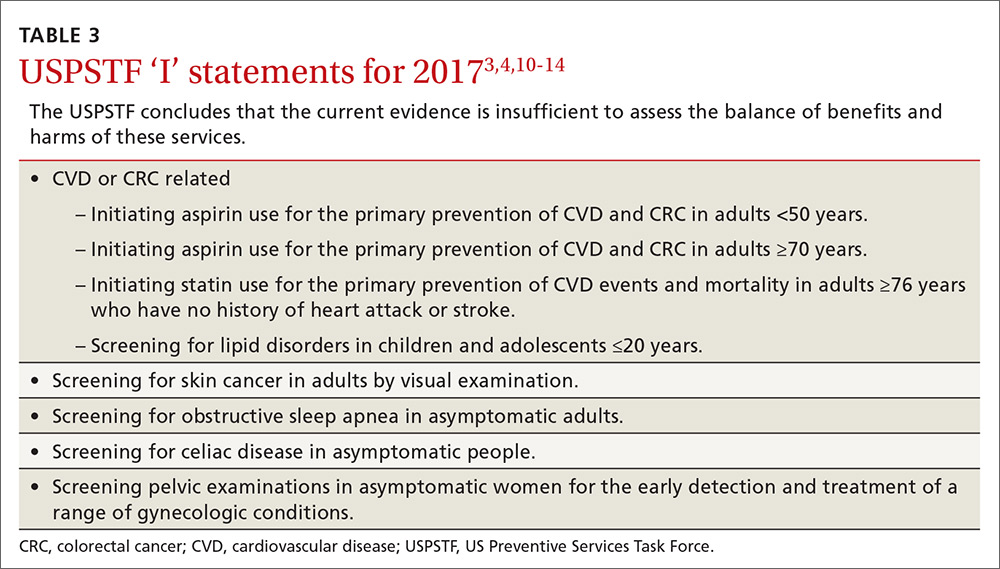

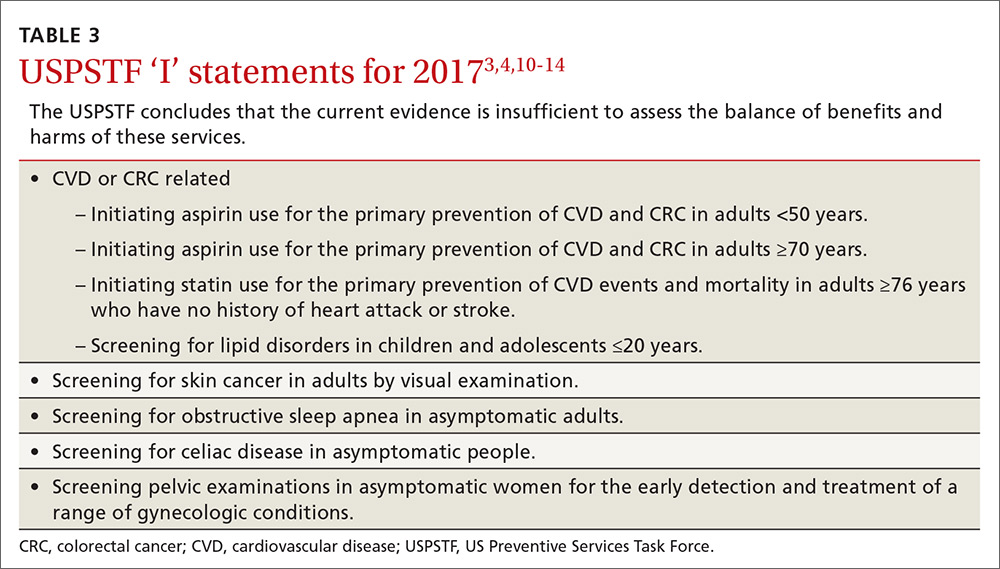

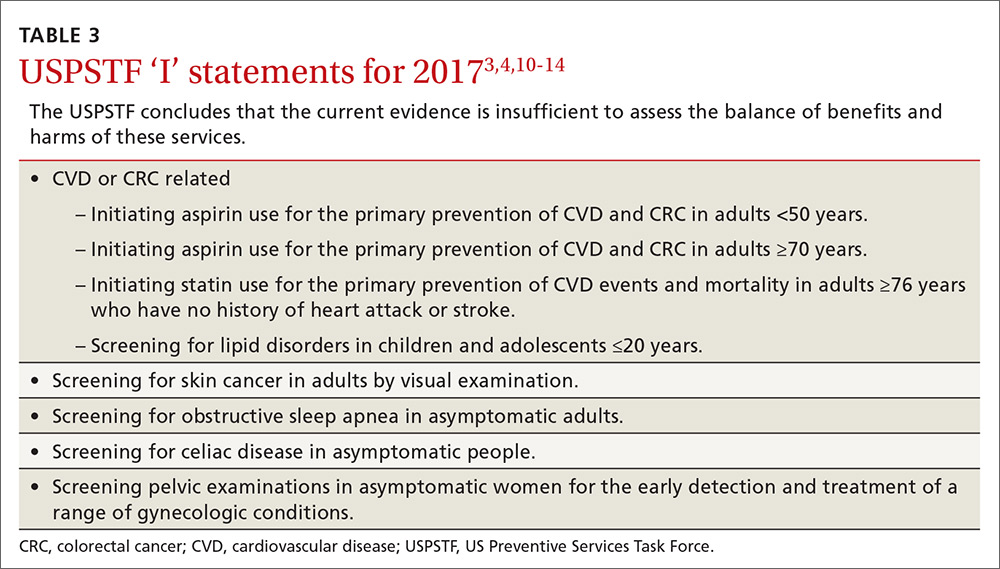

Adults for whom low-dose aspirin and low- to moderate-dose statins are recommended are described in TABLE 1.2-8 Patients for whom individual decision making is advised, rather than a generalized recommendation, are reviewed in TABLE 2.2-4 There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for the use of aspirin before age 50 or at age 70 and older,3 and for the use of statins in adults age 76 and older who do not have a history of CVD4 (TABLE 33,4,10-14). The use of low-dose aspirin and low-to-moderate dose statins have been the subject of JFP audiocasts in May 2016 and January 2017. (See http://bit.ly/2oiun8d and http://bit.ly/2oqkohR.)

2 pregnancy-related recommendations. To prevent neural tube defects in newborns, the Task Force now recommends daily folic acid, 0.4 to 0.8 mg (400 to 800 mcg), for all women who are planning on or are capable of becoming pregnant.5 This is an update of a 2009 recommendation that was worded slightly differently, recommending the supplement for all women of childbearing age.

A new recommendation on breastfeeding recognizes its benefits for both mother and baby and finds that interventions to encourage breastfeeding increase the prevalence of this practice and its duration.6 Interventions—provided to individuals or groups by professionals or peers or through formal education—include promoting the benefits of breastfeeding, giving practical advice and direct support on how to breastfeed, and offering psychological support.

Latent TB: Advantages of newer testing method. The recommendation on screening for latent tuberculosis (TB) is an update from the one made in 1996.7 At that time, screening for latent infection was performed using a tuberculin skin test (TST). Now a TST or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) can be used. Testing with IGRA may be the best option for those who have received a bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination (because it can cause a false-positive TST) or for those who are not likely to return to have their TST read.

Those at high risk for latent TB include people who were born or have resided in countries with a high TB prevalence, those who have lived in a correctional institution or homeless shelter, and anyone in a high-risk group based on local epidemiology of the disease. (Read more on TB in this month’s Case Report.) Others at high risk are those who are immune suppressed because of infection or medications, and those who work in health care or correctional facilities. Screening of these groups is usually conducted as part of occupational health or is considered part of routine health care.

Syphilis: Screen high-risk individuals in 2 steps. The recommendation on syphilis screening basically reaffirms the one from 2004.8 Those at high risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men (who now account for 90% of new cases), those who are HIV positive, and those who engage in commercial sex work. Other racial and demographic groups can be at high risk depending on the local epidemiology of the disease. In a separate recommendation, the Task Force advises screening all pregnant women for syphilis.

Screening for syphilis infection involves 2 steps: first, a nontreponemal test (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or rapid plasma reagin [RPR] test); second, a confirmatory treponemal antibody detection test (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-ABS] or Treponema pallidum particle agglutination [TPPA] test). Treatment for syphilis remains benzathine penicillin with the number of injections depending on the stage of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is the best source for current recommendations for treatment of all sexually transmitted infections.15

Screening tests to avoid

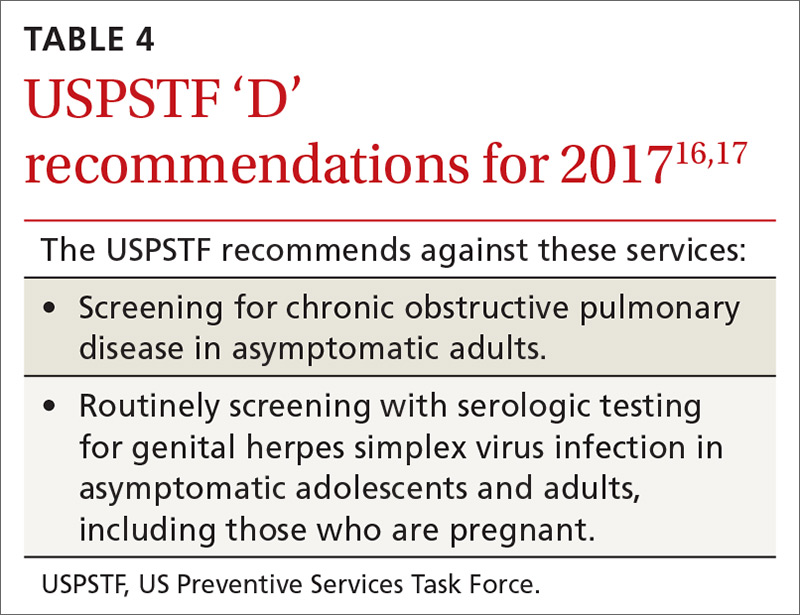

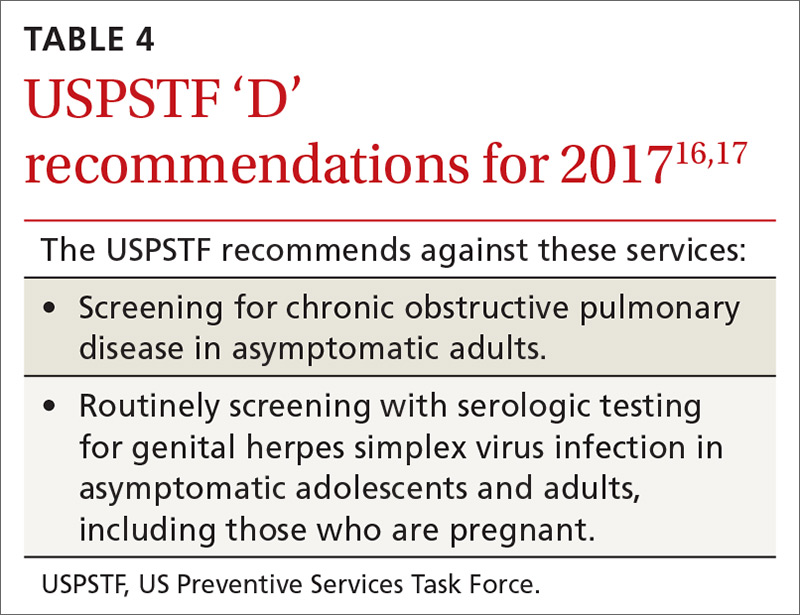

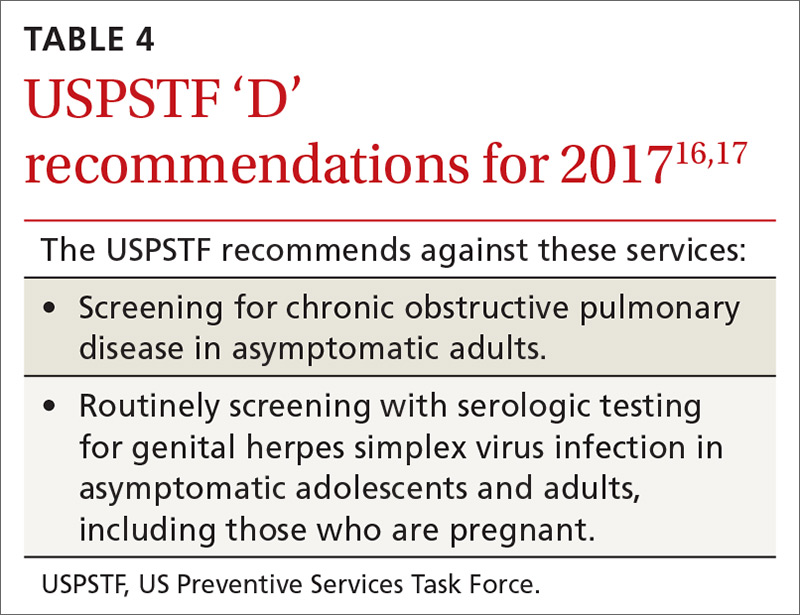

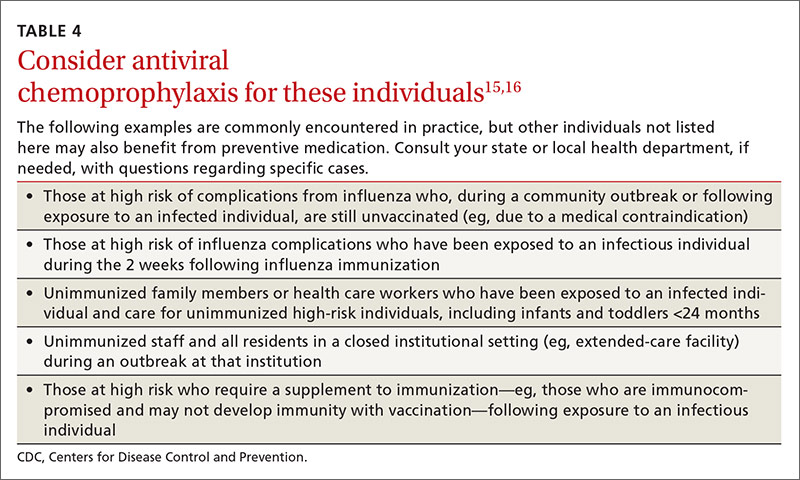

TABLE 416,17 lists screening tests the Task Force recommends against. While chronic obstructive pulmonary disease afflicts 14% of US adults ages 40 to 79 years and is the third leading cause of death in the country, the Task Force found that early detection in asymptomatic adults does not affect the course of the illness and is of no benefit.16

Genital herpes, also prevalent, infects an estimated one out of 6 individuals, ages 14 to 49. It causes little mortality, except in neonates, but those infected can have recurrent flares and suffer psychological harms from stigmatization. Most genital herpes is caused by herpes simplex virus-2, and there is a serological test to detect it. However, the Task Force recommends against using the test to screen asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including those who are pregnant. This recommendation is based on the test’s high false-positive rate, which can cause emotional harm, and on the lack of evidence that detection through screening improves outcomes.17

The evidence is lacking for these practices

The Task Force is one of only a few organizations that will not make a recommendation if evidence is lacking on benefits and harms. In addition to the ‘I’ statements regarding CVD and CRC mentioned earlier, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for lipid disorders in individuals ages 20 years or younger,10 performing a visual skin exam as a screening tool for skin cancer,11 screening for celiac disease,12 performing a periodic pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,13 and screening for obstructive sleep apnea using screening questionnaires14 (TABLE 33,4,10-14).

SIDEBAR

A change for prostate cancer screening?The USPSTF recently issued new draft recommendations regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/).

The draft now divides men into 2 age groups, stating that the decision to screen for prostate cancer using a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test should be individualized for men ages 55 to 69 years (a C recommendation, meaning that there is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small), and that men ages 70 and older (lowered from age 75 in the previous 2012 recommendation1) should not be screened (a D recommendation, meaning that there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits).

The USPSTF believes that clinicians should explain to men ages 55 to 69 years that screening offers a small potential benefit of reducing the chance of dying from prostate cancer, but also comes with potential harms, including false-positive results requiring additional testing/procedures, overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and treatment complications such as incontinence and impotence. In this way, each man has the chance to incorporate his values and preferences into the decision.

For men ages 70 and older, the potential benefits simply do not outweigh the potential harms, according to the USPSTF.

1. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening#Pod1. Accessed April 11, 2017.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Eight USPSTF recommendations FPs need to know about. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:338-341.

2. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

3. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medications. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer. Accessed March 22, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

5. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2017.

6. USPSTF. Breastfeeding: primary care interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breastfeeding-primary-care-interventions. Accessed March 22, 2017.

7. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/latent-tuberculosis-infection-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed March 22, 2017.

9. AAFP. Colorectal cancer screening, adults. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/colorectal-cancer.html. Accessed March 22, 2017.

10. USPSTF. Lipid disorders in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lipid-disorders-in-children-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

11. USPSTF. Skin cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

12. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

13. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2017.

14. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

15. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed March 22, 2017.

16. USPSTF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

17. USPSTF. Genital herpes infection: serologic screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/genital-herpes-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

Since the last Practice Alert update on the United States Preventive Services Task Force in May of 2016,1 the Task Force has released 19 recommendations on 13 topics that include: the use of aspirin and statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD); support for breastfeeding; use of folic acid during pregnancy; and screening for syphilis, latent tuberculosis (TB), herpes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), colorectal cancer (CRC), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), celiac disease, and skin cancer. The Task Force also released a draft recommendation regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (see “A change for prostate cancer screening?”) and addressed screening pelvic examinations in asymptomatic women, the subject of this month’s audiocast. (To listen, go to: http://bit.ly/2nIVoD5.)

Recommendations to implement

Recommendations from the past year that family physicians should put into practice are detailed below and in TABLE 1.2-8

CRC: Screen all individuals ages 50 to 75, but 76 to 85 selectively. The Task Force reaffirmed its 2008 finding that screening for CRC in adults ages 50 to 75 years is substantially beneficial.2 In contrast to the previous recommendation, however, the new one does not state which screening tests are preferred. The tests considered were 3 stool tests (fecal immunochemical test [FIT], FIT-tumor DNA testing [FIT-DNA], and guaiac-based fecal occult blood test [gFOBT]), as well as 3 direct visualization tests (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and CT colonoscopy). The Task Force assessed various testing frequencies of each test and some test combinations. While the Task Force does not recommend any one screening strategy, there are still significant unknowns about FIT-DNA and CT colonoscopy. The American Academy of Family Physicians does not recommend using these 2 tests for screening purposes at this time.9

CRC screening for adults ages 76 to 85 was given a “C” recommendation, which means the value of the service to the population overall is small, but that certain individuals may benefit from it. The Task Force advises selectively offering a “C” service to individuals based on professional judgment and patient preferences. Regarding CRC screening in individuals 76 years or older, the ones most likely to benefit are those who have never been screened and those without significant comorbidities that could limit life expectancy. All “C” recommendations from the past year are listed in TABLE 2.2-4

CVD prevention: When aspirin or a statin is indicated. The Task Force released 2 recommendations for the prevention of CVD this past year. One pertained to the use of low-dose aspirin3 (which also helps to prevent CRC), and the other addressed the use of low- to moderate-dose statins.4 Each recommendation is fairly complicated and nuanced in terms of age and risk for CVD. A decision to use low-dose aspirin must also consider the risk of bleeding.

To calculate a patient’s risk for CVD, the Task Force recommends using the risk calculator developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/).

Adults for whom low-dose aspirin and low- to moderate-dose statins are recommended are described in TABLE 1.2-8 Patients for whom individual decision making is advised, rather than a generalized recommendation, are reviewed in TABLE 2.2-4 There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for the use of aspirin before age 50 or at age 70 and older,3 and for the use of statins in adults age 76 and older who do not have a history of CVD4 (TABLE 33,4,10-14). The use of low-dose aspirin and low-to-moderate dose statins have been the subject of JFP audiocasts in May 2016 and January 2017. (See http://bit.ly/2oiun8d and http://bit.ly/2oqkohR.)

2 pregnancy-related recommendations. To prevent neural tube defects in newborns, the Task Force now recommends daily folic acid, 0.4 to 0.8 mg (400 to 800 mcg), for all women who are planning on or are capable of becoming pregnant.5 This is an update of a 2009 recommendation that was worded slightly differently, recommending the supplement for all women of childbearing age.

A new recommendation on breastfeeding recognizes its benefits for both mother and baby and finds that interventions to encourage breastfeeding increase the prevalence of this practice and its duration.6 Interventions—provided to individuals or groups by professionals or peers or through formal education—include promoting the benefits of breastfeeding, giving practical advice and direct support on how to breastfeed, and offering psychological support.

Latent TB: Advantages of newer testing method. The recommendation on screening for latent tuberculosis (TB) is an update from the one made in 1996.7 At that time, screening for latent infection was performed using a tuberculin skin test (TST). Now a TST or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) can be used. Testing with IGRA may be the best option for those who have received a bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination (because it can cause a false-positive TST) or for those who are not likely to return to have their TST read.

Those at high risk for latent TB include people who were born or have resided in countries with a high TB prevalence, those who have lived in a correctional institution or homeless shelter, and anyone in a high-risk group based on local epidemiology of the disease. (Read more on TB in this month’s Case Report.) Others at high risk are those who are immune suppressed because of infection or medications, and those who work in health care or correctional facilities. Screening of these groups is usually conducted as part of occupational health or is considered part of routine health care.

Syphilis: Screen high-risk individuals in 2 steps. The recommendation on syphilis screening basically reaffirms the one from 2004.8 Those at high risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men (who now account for 90% of new cases), those who are HIV positive, and those who engage in commercial sex work. Other racial and demographic groups can be at high risk depending on the local epidemiology of the disease. In a separate recommendation, the Task Force advises screening all pregnant women for syphilis.

Screening for syphilis infection involves 2 steps: first, a nontreponemal test (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or rapid plasma reagin [RPR] test); second, a confirmatory treponemal antibody detection test (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-ABS] or Treponema pallidum particle agglutination [TPPA] test). Treatment for syphilis remains benzathine penicillin with the number of injections depending on the stage of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is the best source for current recommendations for treatment of all sexually transmitted infections.15

Screening tests to avoid

TABLE 416,17 lists screening tests the Task Force recommends against. While chronic obstructive pulmonary disease afflicts 14% of US adults ages 40 to 79 years and is the third leading cause of death in the country, the Task Force found that early detection in asymptomatic adults does not affect the course of the illness and is of no benefit.16

Genital herpes, also prevalent, infects an estimated one out of 6 individuals, ages 14 to 49. It causes little mortality, except in neonates, but those infected can have recurrent flares and suffer psychological harms from stigmatization. Most genital herpes is caused by herpes simplex virus-2, and there is a serological test to detect it. However, the Task Force recommends against using the test to screen asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including those who are pregnant. This recommendation is based on the test’s high false-positive rate, which can cause emotional harm, and on the lack of evidence that detection through screening improves outcomes.17

The evidence is lacking for these practices

The Task Force is one of only a few organizations that will not make a recommendation if evidence is lacking on benefits and harms. In addition to the ‘I’ statements regarding CVD and CRC mentioned earlier, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for lipid disorders in individuals ages 20 years or younger,10 performing a visual skin exam as a screening tool for skin cancer,11 screening for celiac disease,12 performing a periodic pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,13 and screening for obstructive sleep apnea using screening questionnaires14 (TABLE 33,4,10-14).

SIDEBAR

A change for prostate cancer screening?The USPSTF recently issued new draft recommendations regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/).

The draft now divides men into 2 age groups, stating that the decision to screen for prostate cancer using a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test should be individualized for men ages 55 to 69 years (a C recommendation, meaning that there is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small), and that men ages 70 and older (lowered from age 75 in the previous 2012 recommendation1) should not be screened (a D recommendation, meaning that there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits).

The USPSTF believes that clinicians should explain to men ages 55 to 69 years that screening offers a small potential benefit of reducing the chance of dying from prostate cancer, but also comes with potential harms, including false-positive results requiring additional testing/procedures, overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and treatment complications such as incontinence and impotence. In this way, each man has the chance to incorporate his values and preferences into the decision.

For men ages 70 and older, the potential benefits simply do not outweigh the potential harms, according to the USPSTF.

1. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening#Pod1. Accessed April 11, 2017.

Since the last Practice Alert update on the United States Preventive Services Task Force in May of 2016,1 the Task Force has released 19 recommendations on 13 topics that include: the use of aspirin and statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD); support for breastfeeding; use of folic acid during pregnancy; and screening for syphilis, latent tuberculosis (TB), herpes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), colorectal cancer (CRC), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), celiac disease, and skin cancer. The Task Force also released a draft recommendation regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (see “A change for prostate cancer screening?”) and addressed screening pelvic examinations in asymptomatic women, the subject of this month’s audiocast. (To listen, go to: http://bit.ly/2nIVoD5.)

Recommendations to implement

Recommendations from the past year that family physicians should put into practice are detailed below and in TABLE 1.2-8

CRC: Screen all individuals ages 50 to 75, but 76 to 85 selectively. The Task Force reaffirmed its 2008 finding that screening for CRC in adults ages 50 to 75 years is substantially beneficial.2 In contrast to the previous recommendation, however, the new one does not state which screening tests are preferred. The tests considered were 3 stool tests (fecal immunochemical test [FIT], FIT-tumor DNA testing [FIT-DNA], and guaiac-based fecal occult blood test [gFOBT]), as well as 3 direct visualization tests (colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and CT colonoscopy). The Task Force assessed various testing frequencies of each test and some test combinations. While the Task Force does not recommend any one screening strategy, there are still significant unknowns about FIT-DNA and CT colonoscopy. The American Academy of Family Physicians does not recommend using these 2 tests for screening purposes at this time.9

CRC screening for adults ages 76 to 85 was given a “C” recommendation, which means the value of the service to the population overall is small, but that certain individuals may benefit from it. The Task Force advises selectively offering a “C” service to individuals based on professional judgment and patient preferences. Regarding CRC screening in individuals 76 years or older, the ones most likely to benefit are those who have never been screened and those without significant comorbidities that could limit life expectancy. All “C” recommendations from the past year are listed in TABLE 2.2-4

CVD prevention: When aspirin or a statin is indicated. The Task Force released 2 recommendations for the prevention of CVD this past year. One pertained to the use of low-dose aspirin3 (which also helps to prevent CRC), and the other addressed the use of low- to moderate-dose statins.4 Each recommendation is fairly complicated and nuanced in terms of age and risk for CVD. A decision to use low-dose aspirin must also consider the risk of bleeding.

To calculate a patient’s risk for CVD, the Task Force recommends using the risk calculator developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (http://www.cvriskcalculator.com/).

Adults for whom low-dose aspirin and low- to moderate-dose statins are recommended are described in TABLE 1.2-8 Patients for whom individual decision making is advised, rather than a generalized recommendation, are reviewed in TABLE 2.2-4 There is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for the use of aspirin before age 50 or at age 70 and older,3 and for the use of statins in adults age 76 and older who do not have a history of CVD4 (TABLE 33,4,10-14). The use of low-dose aspirin and low-to-moderate dose statins have been the subject of JFP audiocasts in May 2016 and January 2017. (See http://bit.ly/2oiun8d and http://bit.ly/2oqkohR.)

2 pregnancy-related recommendations. To prevent neural tube defects in newborns, the Task Force now recommends daily folic acid, 0.4 to 0.8 mg (400 to 800 mcg), for all women who are planning on or are capable of becoming pregnant.5 This is an update of a 2009 recommendation that was worded slightly differently, recommending the supplement for all women of childbearing age.

A new recommendation on breastfeeding recognizes its benefits for both mother and baby and finds that interventions to encourage breastfeeding increase the prevalence of this practice and its duration.6 Interventions—provided to individuals or groups by professionals or peers or through formal education—include promoting the benefits of breastfeeding, giving practical advice and direct support on how to breastfeed, and offering psychological support.

Latent TB: Advantages of newer testing method. The recommendation on screening for latent tuberculosis (TB) is an update from the one made in 1996.7 At that time, screening for latent infection was performed using a tuberculin skin test (TST). Now a TST or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) can be used. Testing with IGRA may be the best option for those who have received a bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination (because it can cause a false-positive TST) or for those who are not likely to return to have their TST read.

Those at high risk for latent TB include people who were born or have resided in countries with a high TB prevalence, those who have lived in a correctional institution or homeless shelter, and anyone in a high-risk group based on local epidemiology of the disease. (Read more on TB in this month’s Case Report.) Others at high risk are those who are immune suppressed because of infection or medications, and those who work in health care or correctional facilities. Screening of these groups is usually conducted as part of occupational health or is considered part of routine health care.

Syphilis: Screen high-risk individuals in 2 steps. The recommendation on syphilis screening basically reaffirms the one from 2004.8 Those at high risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men (who now account for 90% of new cases), those who are HIV positive, and those who engage in commercial sex work. Other racial and demographic groups can be at high risk depending on the local epidemiology of the disease. In a separate recommendation, the Task Force advises screening all pregnant women for syphilis.

Screening for syphilis infection involves 2 steps: first, a nontreponemal test (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or rapid plasma reagin [RPR] test); second, a confirmatory treponemal antibody detection test (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-ABS] or Treponema pallidum particle agglutination [TPPA] test). Treatment for syphilis remains benzathine penicillin with the number of injections depending on the stage of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is the best source for current recommendations for treatment of all sexually transmitted infections.15

Screening tests to avoid

TABLE 416,17 lists screening tests the Task Force recommends against. While chronic obstructive pulmonary disease afflicts 14% of US adults ages 40 to 79 years and is the third leading cause of death in the country, the Task Force found that early detection in asymptomatic adults does not affect the course of the illness and is of no benefit.16

Genital herpes, also prevalent, infects an estimated one out of 6 individuals, ages 14 to 49. It causes little mortality, except in neonates, but those infected can have recurrent flares and suffer psychological harms from stigmatization. Most genital herpes is caused by herpes simplex virus-2, and there is a serological test to detect it. However, the Task Force recommends against using the test to screen asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including those who are pregnant. This recommendation is based on the test’s high false-positive rate, which can cause emotional harm, and on the lack of evidence that detection through screening improves outcomes.17

The evidence is lacking for these practices

The Task Force is one of only a few organizations that will not make a recommendation if evidence is lacking on benefits and harms. In addition to the ‘I’ statements regarding CVD and CRC mentioned earlier, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for lipid disorders in individuals ages 20 years or younger,10 performing a visual skin exam as a screening tool for skin cancer,11 screening for celiac disease,12 performing a periodic pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,13 and screening for obstructive sleep apnea using screening questionnaires14 (TABLE 33,4,10-14).

SIDEBAR

A change for prostate cancer screening?The USPSTF recently issued new draft recommendations regarding prostate cancer screening in asymptomatic men (available at: https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/).

The draft now divides men into 2 age groups, stating that the decision to screen for prostate cancer using a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test should be individualized for men ages 55 to 69 years (a C recommendation, meaning that there is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small), and that men ages 70 and older (lowered from age 75 in the previous 2012 recommendation1) should not be screened (a D recommendation, meaning that there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits).

The USPSTF believes that clinicians should explain to men ages 55 to 69 years that screening offers a small potential benefit of reducing the chance of dying from prostate cancer, but also comes with potential harms, including false-positive results requiring additional testing/procedures, overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and treatment complications such as incontinence and impotence. In this way, each man has the chance to incorporate his values and preferences into the decision.

For men ages 70 and older, the potential benefits simply do not outweigh the potential harms, according to the USPSTF.

1. USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening#Pod1. Accessed April 11, 2017.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Eight USPSTF recommendations FPs need to know about. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:338-341.

2. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

3. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medications. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer. Accessed March 22, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

5. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2017.

6. USPSTF. Breastfeeding: primary care interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breastfeeding-primary-care-interventions. Accessed March 22, 2017.

7. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/latent-tuberculosis-infection-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed March 22, 2017.

9. AAFP. Colorectal cancer screening, adults. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/colorectal-cancer.html. Accessed March 22, 2017.

10. USPSTF. Lipid disorders in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lipid-disorders-in-children-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

11. USPSTF. Skin cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

12. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

13. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2017.

14. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

15. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed March 22, 2017.

16. USPSTF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

17. USPSTF. Genital herpes infection: serologic screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/genital-herpes-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Eight USPSTF recommendations FPs need to know about. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:338-341.

2. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

3. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medications. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer. Accessed March 22, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Statin use for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

5. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2017.

6. USPSTF. Breastfeeding: primary care interventions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breastfeeding-primary-care-interventions. Accessed March 22, 2017.

7. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/latent-tuberculosis-infection-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed March 22, 2017.

9. AAFP. Colorectal cancer screening, adults. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/colorectal-cancer.html. Accessed March 22, 2017.

10. USPSTF. Lipid disorders in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lipid-disorders-in-children-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

11. USPSTF. Skin cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/skin-cancer-screening2. Accessed March 22, 2017.

12. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

13. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2017.

14. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

15. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed March 22, 2017.

16. USPSTF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-screening. Accessed March 22, 2017.

17. USPSTF. Genital herpes infection: serologic screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/genital-herpes-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2017.

ACIP vaccine update, 2017

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met 3 times in 2016 and introduced or revised recommendations on influenza, meningococcal, human papillomavirus (HPV), cholera, and hepatitis B vaccines. This Practice Alert highlights the most important new recommendations, except those for influenza vaccines, which were described in a previous Practice Alert.1 (See the summary of how this year’s flu season compares to last year’s.)

SIDEBAR

PRACTICE ALERT UPDATE

How this year's flu season compares to last yearThe 2016-2017 influenza season has been relatively mild, with activity nationwide picking up in late January and continuing to increase in February. As of February 16, 90% of the infections typed were type A, and most of those cases (more than 90%) were H3N1. Not surprisingly, the age group most heavily affected has been the elderly.

The hospitalization rate among those ≥65 years as of early February was 113.5/100,000, which is about half the rate of the same week during the 2014-2015 flu season. The hospitalization rate among those ages 50 to 64 years was 23.5/100,000—about 40% lower than the rate during the same week last flu season. At press time, 20 pediatric deaths had occurred, which is less than one-quarter of the number that occurred during the same time last year, and resistance to oseltamivir had not yet been detected in any isolates.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation update: summary of weekly FluView report. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/summary.htm. Accessed February 16, 2017.

Meningococcal vaccine: Now recommended for HIV-positive patients

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine (serogroups A, C, W, and Y) is recommended for all adolescents ages 11 to 12 as a single dose with a booster at age 16.2 It is also recommended for adults and for children (starting at age 2 months) who have high-risk conditions such as functional or anatomic asplenia or complement deficiencies. Others at high risk include microbiologists routinely exposed to isolates of Neisseria meningitidis and those traveling to areas of high meningococcal incidence. ACIP recently added human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection to the list of high-risk conditions.3

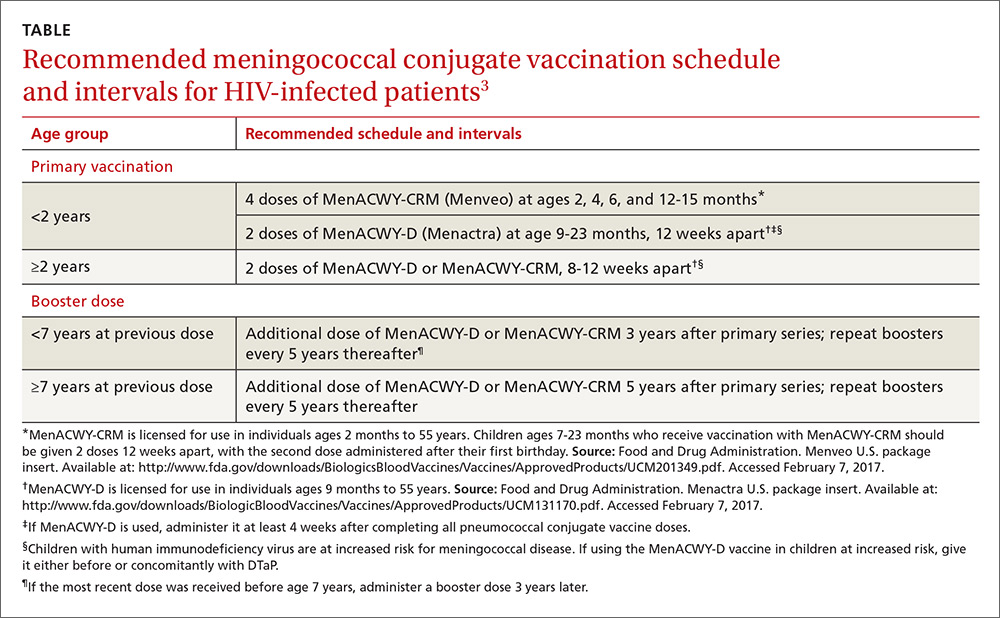

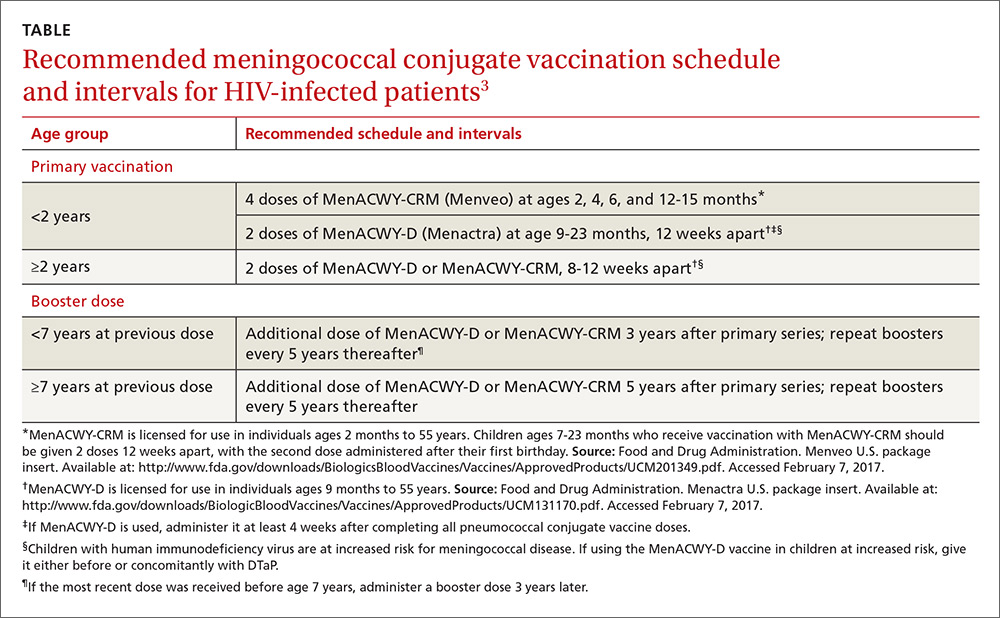

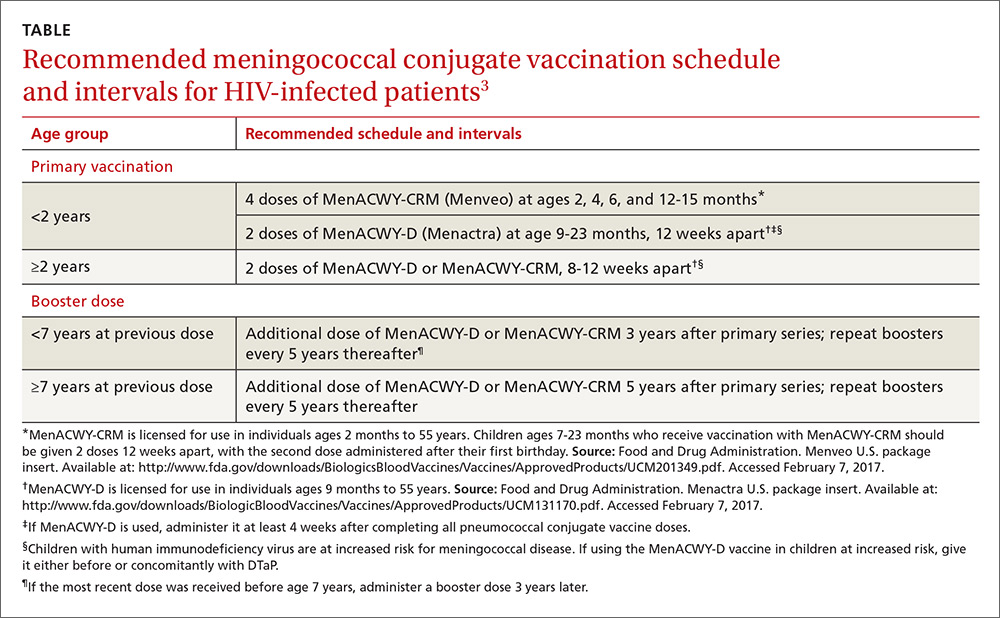

Two meningococcal conjugate vaccines are available in the United States: Menactra, (Sanofi Pasteur), licensed for use in individuals ages 9 months to 55 years; and Menveo (GlaxoSmithKline), licensed for use in individuals ages 2 months to 55 years. Menveo is the preferred vaccine for children younger than 2 years infected with HIV. However, if Menactra is used, give it at least 4 weeks after completing all pneumococcal conjugate vaccine doses and either before or concomitantly with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP). All individuals who are HIV positive should receive a multi-dose primary series and booster doses. The number of primary doses and timing of boosters depends on the product used and the ages of those vaccinated (TABLE3).

Although neither meningococcal conjugate vaccine product is licensed for use in individuals 56 years or older, ACIP recommends using one of the products for HIV-infected individuals in this age group because the only meningococcal vaccine licensed for use in adults 56 or older, meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV4, Menomune, Sanofi Pasteur), has not been studied in patients with HIV infection.

Serogroup B. Two vaccine products provide short-term protection against meningococcal serogroup B: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). In 2015, ACIP made a “B” recommendation for the use of these vaccines in individuals 16 to 23 years of age, with the preferred age range being 16 to 18.4 A “B” recommendation means that while ACIP does not advise routine use of the vaccines in this age group, the vaccines can be administered to those who desire them. ACIP has recommended routine use of these products only for individuals 10 years and older who are at high risk for meningococcal disease.5

Trumenba was approved as a 3-dose vaccine, administered at 0, 2, and 6 months. Bexsero requires 2 doses given at least one month apart. At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP approved a 2-dose Trumenba schedule, at 0 and 6 months, when administered to those not at risk for meningococcal disease.6 However, during an outbreak, and for those at high risk for meningococcal disease, adhere to the original 3-dose schedule.

HPV vaccine: Now a 2-dose schedule for younger patients

The only HPV vaccine available in the United States is the 9-valent HPV vaccine (9vHPV), Gardasil 9. It is approved for both males and females ages 9 to 26 years. ACIP recommends it for both sexes at ages 11 or 12, and advises catch-up doses for men through age 21 and women through age 26. It also recommends vaccination through age 26 for men who have sex with men and men

The HPV vaccine is approved for a 3-dose schedule at 0, 1 to 2, and 6 months. At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP approved a 2-dose schedule (0, 6-12 months) for those starting the vaccine before their 15th birthday.7 Those starting the vaccine after their 15th birthday, and individuals at any age with an immune-compromising condition, should receive 3 doses. It is hoped that a 2-dose schedule will help to increase the uptake of this safe, effective, and underused vaccine.

Cholera: A new vaccine is available

In June 2016, the FDA approved a live, attenuated, single-dose, oral vaccine (Vaxchora, PaxVax, Inc.) for the prevention of cholera in adults ages 18 to 64 years. It is the only cholera vaccine approved in the United States.

Cholera occurs at low rates among travelers to areas where the disease is endemic. The key to prevention is food and water precautions, and thus the vaccine is not recommended for most travelers—only for those who are at increased risk of exposure to cholera or who have a medical condition that predisposes them to a poor response to medical care if cholera is contracted.8 Risk increases with long-term or frequent travel to endemic areas where safe food and water is not always available. Examples of compromising medical conditions include a blood type O, low gastric acidity, and heart or kidney disease.

Duration of the vaccine’s effectiveness is unknown, given a lack of data beyond 6 months. No recommendation for revaccination has been made, and this issue will be assessed as more data are collected. Other unknowns about the vaccine include its effectiveness among immune-suppressed individuals and pregnant women, as well as for those who live in cholera endemic areas or were previously vaccinated with another cholera vaccine.

Hepatitis B: Vaccinate newborns sooner

The incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has declined by more than 90% since the introduction of a vaccine in 1982.9

Current recommendations for the prevention of HBV include:9

- Screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and use HBIG and hepatitis B vaccines within 12 hours of birth for all newborns whose mothers are HBsAg positive or have an unknown HBsAg status.

- Administer the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccine to all other infants.

- Routinely vaccinate previously unvaccinated children and adolescents.

- Routinely vaccinate adults who are non-immune and at risk for HBV infection.

At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP adopted a comprehensive update of all HBV prevention recommendations. (This will be the subject of a future Practice Alert.) Included was a revision of a previously permissive recommendation that allowed the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine for newborns to be given within 2 months of hospital discharge. The new recommendation9 states that newborns of mothers known to be HBsAg negative should be vaccinated within 24 hours (if weight is ≥2000 g) or at age one month or at hospital discharge (if weight is <2000 g).

The first dose should be given within 12 hours of birth to all newborns whose mothers are HBsAg positive or have an unknown HBsAg status.9

Immunization schedules

Every year ACIP updates the adult and child immunization schedules to incorporate the changes from the previous year. These can be found on the ACIP Web site at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. This Web site remains the most authoritative and accurate source of information on vaccines and immunizations for both professionals and the public.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Need-to-know information for the 2016-2017 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:613-617.

2. Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Clark TA, et al. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1-28.

3. MacNeil JR, Rubin LG, Patton M, et al. Recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines in HIV-infected persons— Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1189-1194.

4. MacNeil JR, Rubin LG, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1171-1176.

5. Folaranmi T, Rubin L, Martin SW, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk for serogroup B meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:608-612.

6. MacNeil J. Considerations for Use of 2- and 3-Dose Schedules of MenB-FHbp (Trumenba). Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 19, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-10/meningococcal-05-macneil.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

7. Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1405-1408.

8. Wong KW. Cholera vaccine update and proposed recommendations. Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/cholera-02-wong.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2017.

9. Schillie S. Revised ACIP Hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine recommendations. Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 19, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-10/hepatitis-02-schillie-october-2016.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2017.

10.

11. Ko SC, Fan L, Smith EA, et al. Estimated annual perinatal hepatitis B virus infections in the United States, 2000-2009. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5:114-121.

12. Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, et al. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1-25.

13. Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lee GC, et al. Prevention of perinatally transmitted hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet. 1983;2:1099-1102.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met 3 times in 2016 and introduced or revised recommendations on influenza, meningococcal, human papillomavirus (HPV), cholera, and hepatitis B vaccines. This Practice Alert highlights the most important new recommendations, except those for influenza vaccines, which were described in a previous Practice Alert.1 (See the summary of how this year’s flu season compares to last year’s.)

SIDEBAR

PRACTICE ALERT UPDATE

How this year's flu season compares to last yearThe 2016-2017 influenza season has been relatively mild, with activity nationwide picking up in late January and continuing to increase in February. As of February 16, 90% of the infections typed were type A, and most of those cases (more than 90%) were H3N1. Not surprisingly, the age group most heavily affected has been the elderly.

The hospitalization rate among those ≥65 years as of early February was 113.5/100,000, which is about half the rate of the same week during the 2014-2015 flu season. The hospitalization rate among those ages 50 to 64 years was 23.5/100,000—about 40% lower than the rate during the same week last flu season. At press time, 20 pediatric deaths had occurred, which is less than one-quarter of the number that occurred during the same time last year, and resistance to oseltamivir had not yet been detected in any isolates.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation update: summary of weekly FluView report. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/summary.htm. Accessed February 16, 2017.

Meningococcal vaccine: Now recommended for HIV-positive patients

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine (serogroups A, C, W, and Y) is recommended for all adolescents ages 11 to 12 as a single dose with a booster at age 16.2 It is also recommended for adults and for children (starting at age 2 months) who have high-risk conditions such as functional or anatomic asplenia or complement deficiencies. Others at high risk include microbiologists routinely exposed to isolates of Neisseria meningitidis and those traveling to areas of high meningococcal incidence. ACIP recently added human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection to the list of high-risk conditions.3

Two meningococcal conjugate vaccines are available in the United States: Menactra, (Sanofi Pasteur), licensed for use in individuals ages 9 months to 55 years; and Menveo (GlaxoSmithKline), licensed for use in individuals ages 2 months to 55 years. Menveo is the preferred vaccine for children younger than 2 years infected with HIV. However, if Menactra is used, give it at least 4 weeks after completing all pneumococcal conjugate vaccine doses and either before or concomitantly with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP). All individuals who are HIV positive should receive a multi-dose primary series and booster doses. The number of primary doses and timing of boosters depends on the product used and the ages of those vaccinated (TABLE3).

Although neither meningococcal conjugate vaccine product is licensed for use in individuals 56 years or older, ACIP recommends using one of the products for HIV-infected individuals in this age group because the only meningococcal vaccine licensed for use in adults 56 or older, meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV4, Menomune, Sanofi Pasteur), has not been studied in patients with HIV infection.

Serogroup B. Two vaccine products provide short-term protection against meningococcal serogroup B: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). In 2015, ACIP made a “B” recommendation for the use of these vaccines in individuals 16 to 23 years of age, with the preferred age range being 16 to 18.4 A “B” recommendation means that while ACIP does not advise routine use of the vaccines in this age group, the vaccines can be administered to those who desire them. ACIP has recommended routine use of these products only for individuals 10 years and older who are at high risk for meningococcal disease.5

Trumenba was approved as a 3-dose vaccine, administered at 0, 2, and 6 months. Bexsero requires 2 doses given at least one month apart. At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP approved a 2-dose Trumenba schedule, at 0 and 6 months, when administered to those not at risk for meningococcal disease.6 However, during an outbreak, and for those at high risk for meningococcal disease, adhere to the original 3-dose schedule.

HPV vaccine: Now a 2-dose schedule for younger patients

The only HPV vaccine available in the United States is the 9-valent HPV vaccine (9vHPV), Gardasil 9. It is approved for both males and females ages 9 to 26 years. ACIP recommends it for both sexes at ages 11 or 12, and advises catch-up doses for men through age 21 and women through age 26. It also recommends vaccination through age 26 for men who have sex with men and men

The HPV vaccine is approved for a 3-dose schedule at 0, 1 to 2, and 6 months. At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP approved a 2-dose schedule (0, 6-12 months) for those starting the vaccine before their 15th birthday.7 Those starting the vaccine after their 15th birthday, and individuals at any age with an immune-compromising condition, should receive 3 doses. It is hoped that a 2-dose schedule will help to increase the uptake of this safe, effective, and underused vaccine.

Cholera: A new vaccine is available

In June 2016, the FDA approved a live, attenuated, single-dose, oral vaccine (Vaxchora, PaxVax, Inc.) for the prevention of cholera in adults ages 18 to 64 years. It is the only cholera vaccine approved in the United States.

Cholera occurs at low rates among travelers to areas where the disease is endemic. The key to prevention is food and water precautions, and thus the vaccine is not recommended for most travelers—only for those who are at increased risk of exposure to cholera or who have a medical condition that predisposes them to a poor response to medical care if cholera is contracted.8 Risk increases with long-term or frequent travel to endemic areas where safe food and water is not always available. Examples of compromising medical conditions include a blood type O, low gastric acidity, and heart or kidney disease.

Duration of the vaccine’s effectiveness is unknown, given a lack of data beyond 6 months. No recommendation for revaccination has been made, and this issue will be assessed as more data are collected. Other unknowns about the vaccine include its effectiveness among immune-suppressed individuals and pregnant women, as well as for those who live in cholera endemic areas or were previously vaccinated with another cholera vaccine.

Hepatitis B: Vaccinate newborns sooner

The incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has declined by more than 90% since the introduction of a vaccine in 1982.9

Current recommendations for the prevention of HBV include:9

- Screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and use HBIG and hepatitis B vaccines within 12 hours of birth for all newborns whose mothers are HBsAg positive or have an unknown HBsAg status.

- Administer the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccine to all other infants.

- Routinely vaccinate previously unvaccinated children and adolescents.

- Routinely vaccinate adults who are non-immune and at risk for HBV infection.

At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP adopted a comprehensive update of all HBV prevention recommendations. (This will be the subject of a future Practice Alert.) Included was a revision of a previously permissive recommendation that allowed the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine for newborns to be given within 2 months of hospital discharge. The new recommendation9 states that newborns of mothers known to be HBsAg negative should be vaccinated within 24 hours (if weight is ≥2000 g) or at age one month or at hospital discharge (if weight is <2000 g).

The first dose should be given within 12 hours of birth to all newborns whose mothers are HBsAg positive or have an unknown HBsAg status.9

Immunization schedules

Every year ACIP updates the adult and child immunization schedules to incorporate the changes from the previous year. These can be found on the ACIP Web site at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. This Web site remains the most authoritative and accurate source of information on vaccines and immunizations for both professionals and the public.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met 3 times in 2016 and introduced or revised recommendations on influenza, meningococcal, human papillomavirus (HPV), cholera, and hepatitis B vaccines. This Practice Alert highlights the most important new recommendations, except those for influenza vaccines, which were described in a previous Practice Alert.1 (See the summary of how this year’s flu season compares to last year’s.)

SIDEBAR

PRACTICE ALERT UPDATE

How this year's flu season compares to last yearThe 2016-2017 influenza season has been relatively mild, with activity nationwide picking up in late January and continuing to increase in February. As of February 16, 90% of the infections typed were type A, and most of those cases (more than 90%) were H3N1. Not surprisingly, the age group most heavily affected has been the elderly.

The hospitalization rate among those ≥65 years as of early February was 113.5/100,000, which is about half the rate of the same week during the 2014-2015 flu season. The hospitalization rate among those ages 50 to 64 years was 23.5/100,000—about 40% lower than the rate during the same week last flu season. At press time, 20 pediatric deaths had occurred, which is less than one-quarter of the number that occurred during the same time last year, and resistance to oseltamivir had not yet been detected in any isolates.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation update: summary of weekly FluView report. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/summary.htm. Accessed February 16, 2017.

Meningococcal vaccine: Now recommended for HIV-positive patients

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine (serogroups A, C, W, and Y) is recommended for all adolescents ages 11 to 12 as a single dose with a booster at age 16.2 It is also recommended for adults and for children (starting at age 2 months) who have high-risk conditions such as functional or anatomic asplenia or complement deficiencies. Others at high risk include microbiologists routinely exposed to isolates of Neisseria meningitidis and those traveling to areas of high meningococcal incidence. ACIP recently added human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection to the list of high-risk conditions.3

Two meningococcal conjugate vaccines are available in the United States: Menactra, (Sanofi Pasteur), licensed for use in individuals ages 9 months to 55 years; and Menveo (GlaxoSmithKline), licensed for use in individuals ages 2 months to 55 years. Menveo is the preferred vaccine for children younger than 2 years infected with HIV. However, if Menactra is used, give it at least 4 weeks after completing all pneumococcal conjugate vaccine doses and either before or concomitantly with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP). All individuals who are HIV positive should receive a multi-dose primary series and booster doses. The number of primary doses and timing of boosters depends on the product used and the ages of those vaccinated (TABLE3).

Although neither meningococcal conjugate vaccine product is licensed for use in individuals 56 years or older, ACIP recommends using one of the products for HIV-infected individuals in this age group because the only meningococcal vaccine licensed for use in adults 56 or older, meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV4, Menomune, Sanofi Pasteur), has not been studied in patients with HIV infection.

Serogroup B. Two vaccine products provide short-term protection against meningococcal serogroup B: MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and MenB-4C (Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline). In 2015, ACIP made a “B” recommendation for the use of these vaccines in individuals 16 to 23 years of age, with the preferred age range being 16 to 18.4 A “B” recommendation means that while ACIP does not advise routine use of the vaccines in this age group, the vaccines can be administered to those who desire them. ACIP has recommended routine use of these products only for individuals 10 years and older who are at high risk for meningococcal disease.5

Trumenba was approved as a 3-dose vaccine, administered at 0, 2, and 6 months. Bexsero requires 2 doses given at least one month apart. At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP approved a 2-dose Trumenba schedule, at 0 and 6 months, when administered to those not at risk for meningococcal disease.6 However, during an outbreak, and for those at high risk for meningococcal disease, adhere to the original 3-dose schedule.

HPV vaccine: Now a 2-dose schedule for younger patients

The only HPV vaccine available in the United States is the 9-valent HPV vaccine (9vHPV), Gardasil 9. It is approved for both males and females ages 9 to 26 years. ACIP recommends it for both sexes at ages 11 or 12, and advises catch-up doses for men through age 21 and women through age 26. It also recommends vaccination through age 26 for men who have sex with men and men

The HPV vaccine is approved for a 3-dose schedule at 0, 1 to 2, and 6 months. At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP approved a 2-dose schedule (0, 6-12 months) for those starting the vaccine before their 15th birthday.7 Those starting the vaccine after their 15th birthday, and individuals at any age with an immune-compromising condition, should receive 3 doses. It is hoped that a 2-dose schedule will help to increase the uptake of this safe, effective, and underused vaccine.

Cholera: A new vaccine is available

In June 2016, the FDA approved a live, attenuated, single-dose, oral vaccine (Vaxchora, PaxVax, Inc.) for the prevention of cholera in adults ages 18 to 64 years. It is the only cholera vaccine approved in the United States.

Cholera occurs at low rates among travelers to areas where the disease is endemic. The key to prevention is food and water precautions, and thus the vaccine is not recommended for most travelers—only for those who are at increased risk of exposure to cholera or who have a medical condition that predisposes them to a poor response to medical care if cholera is contracted.8 Risk increases with long-term or frequent travel to endemic areas where safe food and water is not always available. Examples of compromising medical conditions include a blood type O, low gastric acidity, and heart or kidney disease.

Duration of the vaccine’s effectiveness is unknown, given a lack of data beyond 6 months. No recommendation for revaccination has been made, and this issue will be assessed as more data are collected. Other unknowns about the vaccine include its effectiveness among immune-suppressed individuals and pregnant women, as well as for those who live in cholera endemic areas or were previously vaccinated with another cholera vaccine.

Hepatitis B: Vaccinate newborns sooner

The incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has declined by more than 90% since the introduction of a vaccine in 1982.9

Current recommendations for the prevention of HBV include:9

- Screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and use HBIG and hepatitis B vaccines within 12 hours of birth for all newborns whose mothers are HBsAg positive or have an unknown HBsAg status.

- Administer the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccine to all other infants.

- Routinely vaccinate previously unvaccinated children and adolescents.

- Routinely vaccinate adults who are non-immune and at risk for HBV infection.

At its October 2016 meeting, ACIP adopted a comprehensive update of all HBV prevention recommendations. (This will be the subject of a future Practice Alert.) Included was a revision of a previously permissive recommendation that allowed the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine for newborns to be given within 2 months of hospital discharge. The new recommendation9 states that newborns of mothers known to be HBsAg negative should be vaccinated within 24 hours (if weight is ≥2000 g) or at age one month or at hospital discharge (if weight is <2000 g).

The first dose should be given within 12 hours of birth to all newborns whose mothers are HBsAg positive or have an unknown HBsAg status.9

Immunization schedules

Every year ACIP updates the adult and child immunization schedules to incorporate the changes from the previous year. These can be found on the ACIP Web site at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. This Web site remains the most authoritative and accurate source of information on vaccines and immunizations for both professionals and the public.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Need-to-know information for the 2016-2017 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:613-617.

2. Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Clark TA, et al. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1-28.

3. MacNeil JR, Rubin LG, Patton M, et al. Recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines in HIV-infected persons— Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1189-1194.

4. MacNeil JR, Rubin LG, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1171-1176.

5. Folaranmi T, Rubin L, Martin SW, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk for serogroup B meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:608-612.

6. MacNeil J. Considerations for Use of 2- and 3-Dose Schedules of MenB-FHbp (Trumenba). Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 19, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-10/meningococcal-05-macneil.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

7. Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1405-1408.

8. Wong KW. Cholera vaccine update and proposed recommendations. Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/cholera-02-wong.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2017.

9. Schillie S. Revised ACIP Hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine recommendations. Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 19, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-10/hepatitis-02-schillie-october-2016.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2017.

10.

11. Ko SC, Fan L, Smith EA, et al. Estimated annual perinatal hepatitis B virus infections in the United States, 2000-2009. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5:114-121.

12. Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, et al. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1-25.

13. Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lee GC, et al. Prevention of perinatally transmitted hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet. 1983;2:1099-1102.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Need-to-know information for the 2016-2017 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:613-617.

2. Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Clark TA, et al. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1-28.

3. MacNeil JR, Rubin LG, Patton M, et al. Recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines in HIV-infected persons— Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1189-1194.

4. MacNeil JR, Rubin LG, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1171-1176.

5. Folaranmi T, Rubin L, Martin SW, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk for serogroup B meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:608-612.

6. MacNeil J. Considerations for Use of 2- and 3-Dose Schedules of MenB-FHbp (Trumenba). Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 19, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-10/meningococcal-05-macneil.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

7. Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1405-1408.

8. Wong KW. Cholera vaccine update and proposed recommendations. Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 22, 2016; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-06/cholera-02-wong.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2017.

9. Schillie S. Revised ACIP Hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine recommendations. Presentation at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 19, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-10/hepatitis-02-schillie-october-2016.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2017.

10.

11. Ko SC, Fan L, Smith EA, et al. Estimated annual perinatal hepatitis B virus infections in the United States, 2000-2009. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5:114-121.

12. Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, et al. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1-25.

13. Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lee GC, et al. Prevention of perinatally transmitted hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet. 1983;2:1099-1102.

CPSTF: A lesser known, but valuable, resource for FPs

Family physicians have come to rely on the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for rigorous, evidence-based recommendations on the use of clinical preventive services. Still, many such services reach too few individuals who need them. And that’s where the less well known Community Preventive Services Task Force comes in. The CPSTF makes recommendations regarding public health interventions and ways to increase the use of preventive services in the clinical setting—eg, means of improving childhood immunization rates or increasing screening for cervical, breast, and colon cancer.

To better understand how the CPSTF can serve as a resource to busy family physicians, it’s helpful to first understand a bit about the inner-workings of the CPSTF itself.

How CPSTF figures out what works

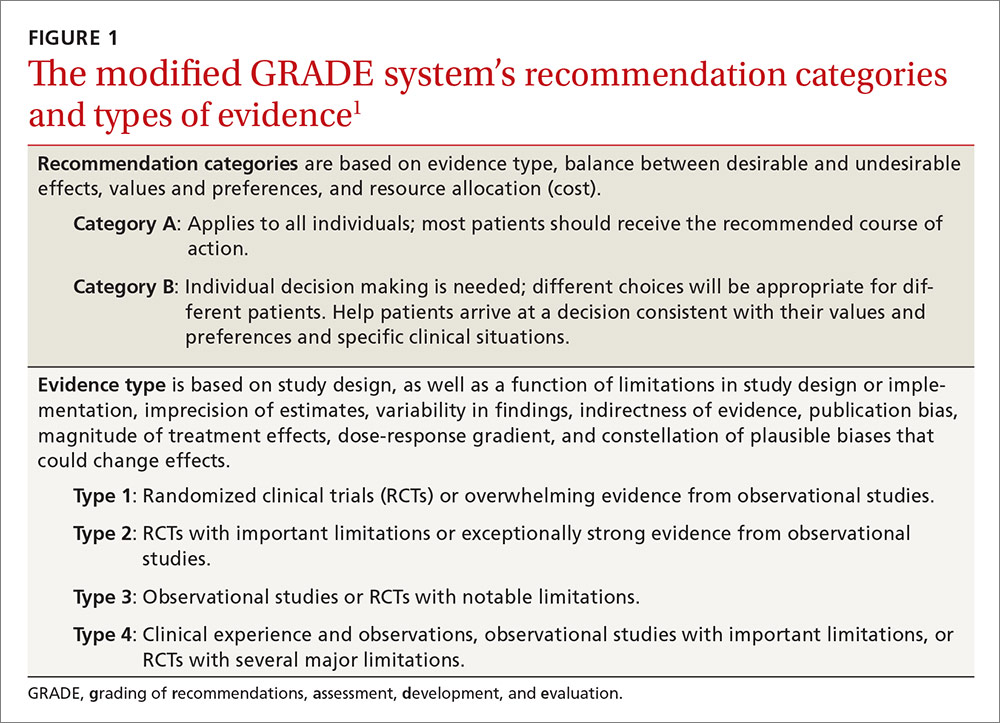

Formed in 1996, the CPSTF consists of 15 independent, nonfederal members with expertise in public health and preventive medicine, appointed by the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Task Force makes recommendations and develops guidance on which community-based health promotion and disease-prevention interventions work and which do not, based on available scientific evidence. The Task Force uses an evidence-based methodology similar to that of the USPSTF—ie, assessing systematic reviews of the evidence and tying recommendations to the strength of the evidence. However, the Task Force has only 3 levels of recommendations: recommend for, recommend against, and insufficient evidence to recommend.

Three CPSTF meetings are held each year, and a representative from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) attends as a liaison, along with liaisons from other organizations with an interest in the methods and recommendations. The CDC provides the CPSTF with technical and administrative support. However, the recommendations developed do not undergo review or approval by the CDC and are the sole responsibility of the Task Force.

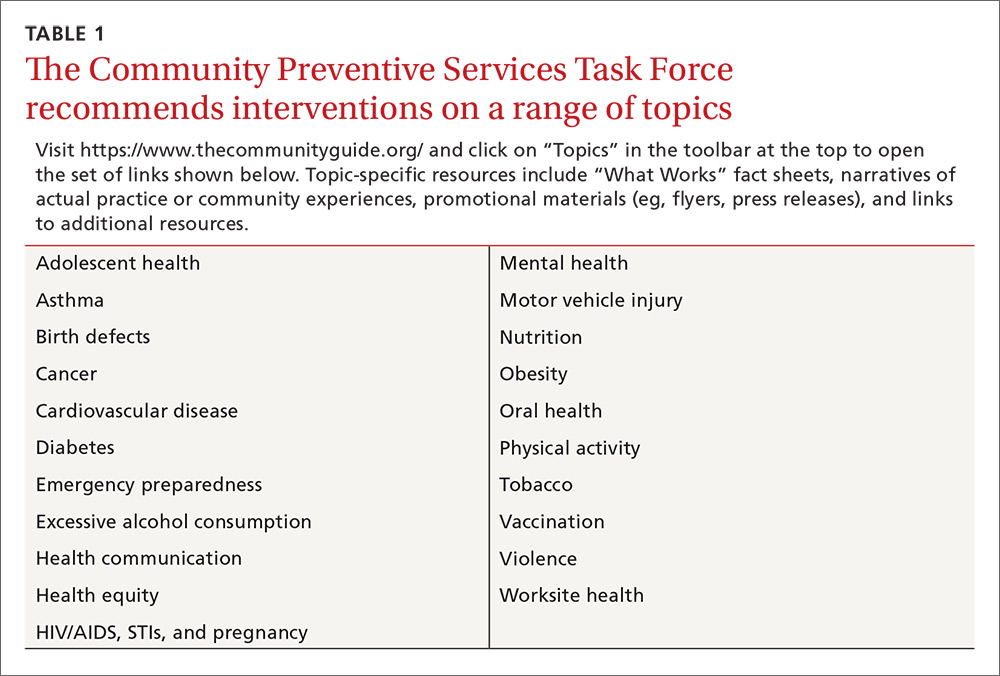

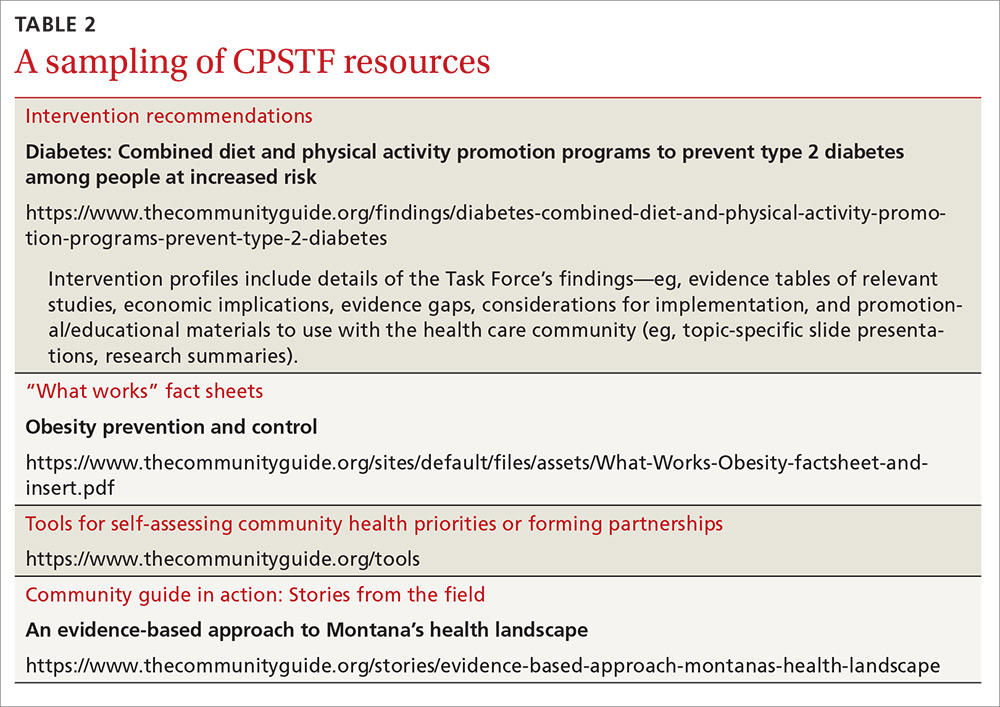

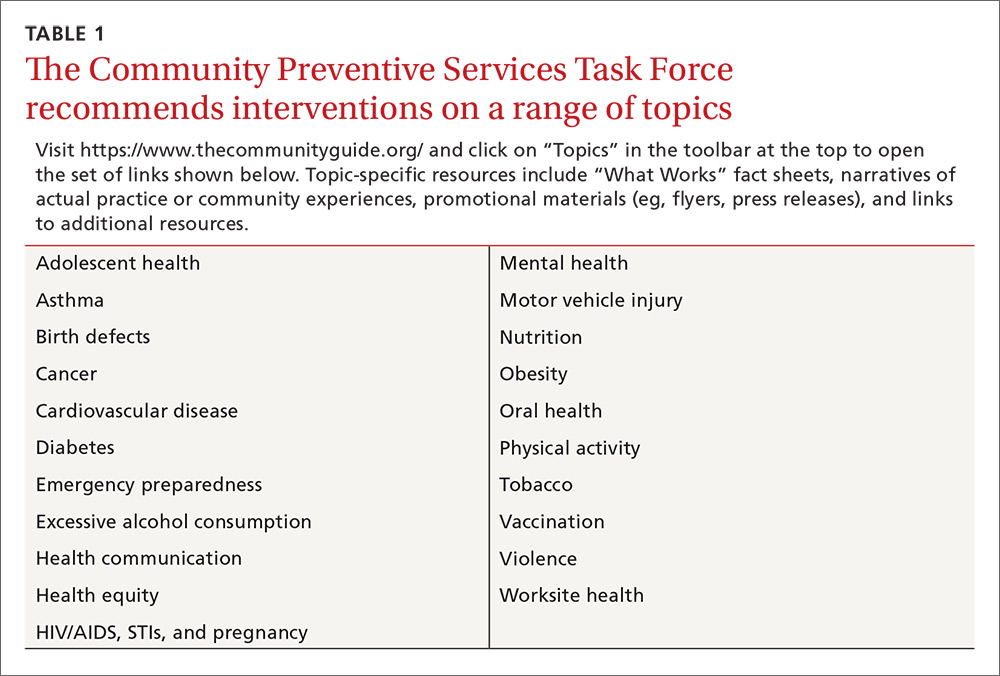

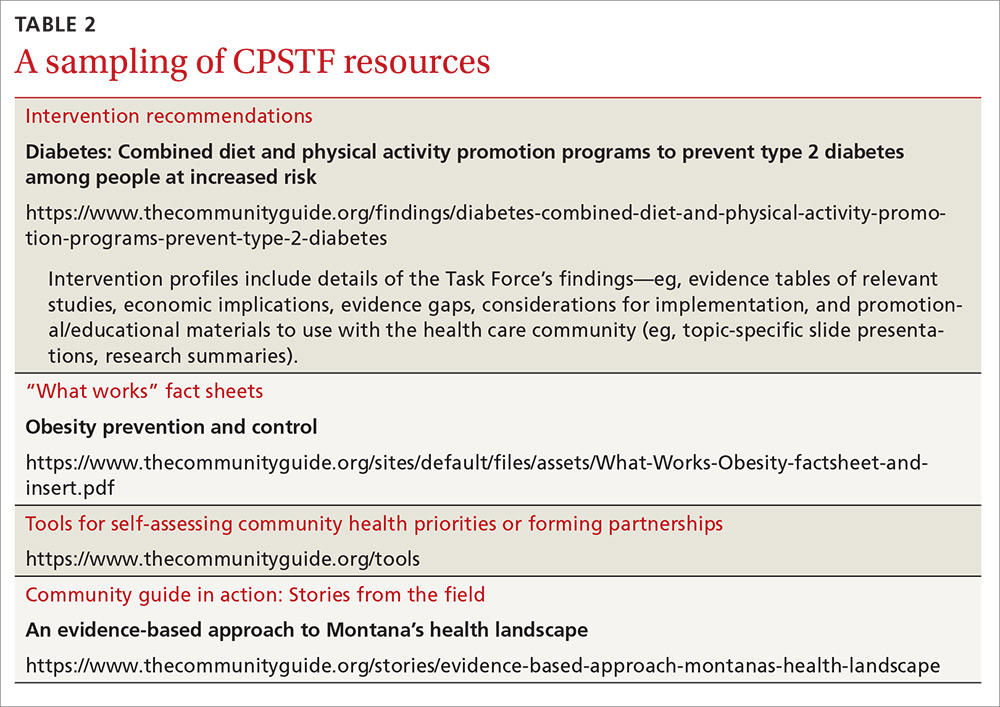

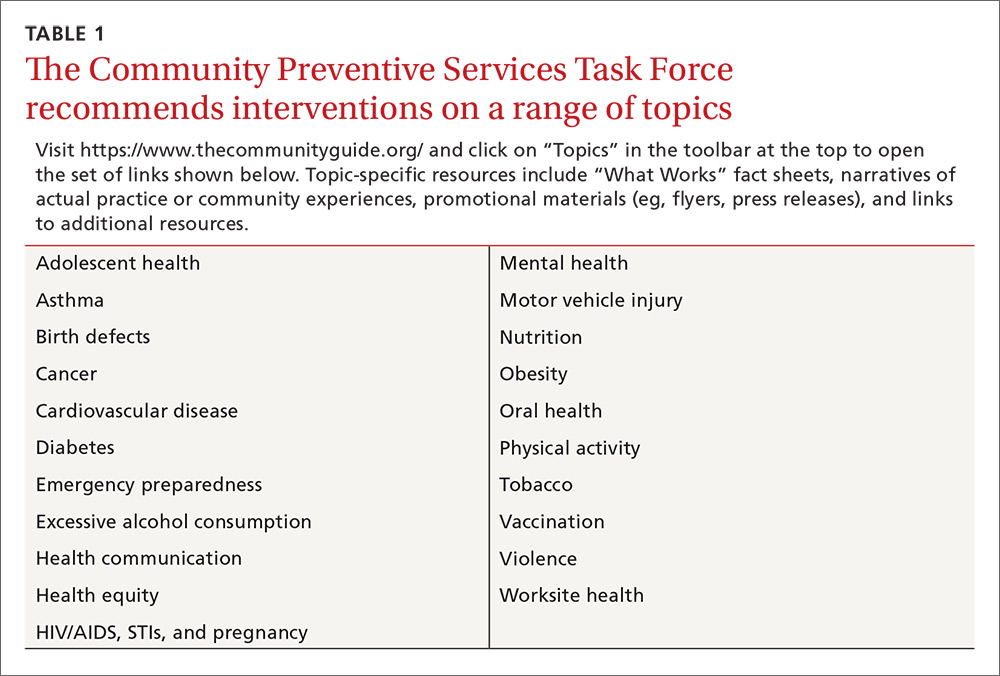

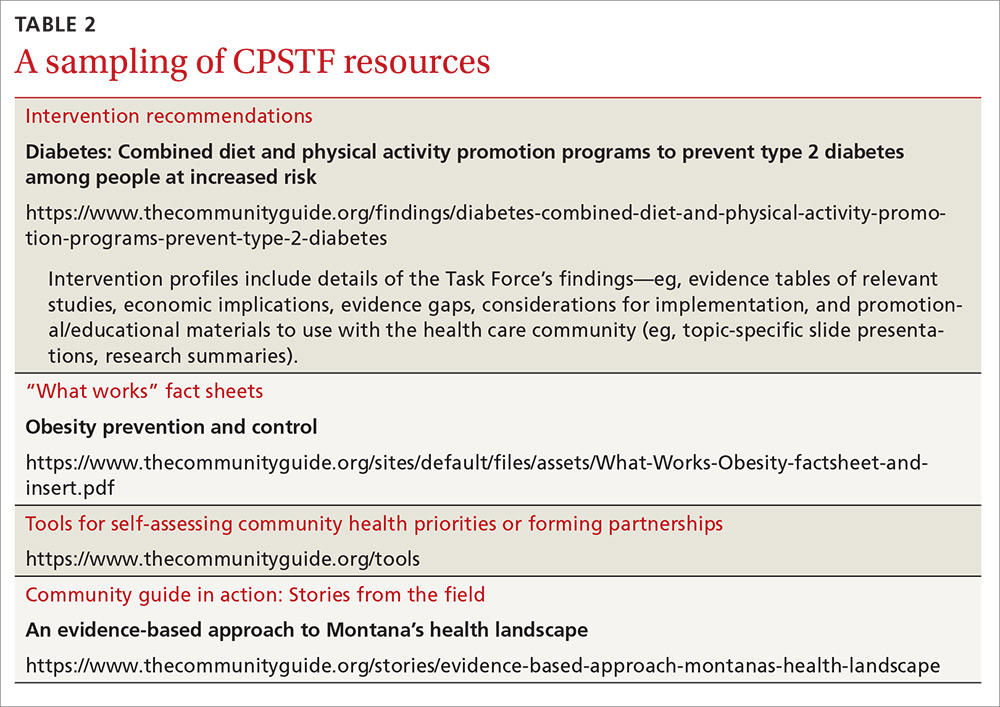

The recommendations made are contained in the Guide to Community Preventive Services, often called The Community Guide, which is available on the Task Force’s Web site at www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. The topics on which the CPSTF currently has recommendations are listed in TABLE 1. (Since community-wide recommendations are rarely subjected to controlled clinical trials, methods of assessing and ranking other forms of evidence are required. To learn more about how the CPSTF approaches this, see: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/our-methodology.)

Improving immunization rates