User login

Are you up to date with new immunization recommendations?

Vaccines are one of the most important and effective tools for protecting the health of the public and family physicians are instrumental in insuring that vaccine recommendations are implemented. With the development of new vaccines come increasingly complex recommendations. Staying current is challenging.

This column describes the most recent changes to the immunization schedules made by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Hepatitis A

Universal vaccination with hepatitis A virus (HAV) vaccine is now recommended for all children between their first and second birthdays, with 2 doses of vaccine given 6 months apart.

Previously, universal vaccination was recommended only for states and population groups known to have a high prevalence of infection. The recommended age for vaccination varied depending on local circumstances, but the vaccine was not approved for use before the second birthday. Because of the marked success in reducing hepatitis A infection rates in high-prevalence areas, most HAV cases now occur in states without routine vaccination recommendations.

Each year, 5000 to 7000 cases of hepatitis A are reported, and it is estimated that 4 times that number of symptomatic cases occur. The ACIP’s new recommendation is based on recent approval of HAV vaccine for use starting at age 1 year, and on the expected doubling of disease reduction from routine, universal vaccination of children. Moreover, universal vaccination of children is expected to reduce hepatitis A incidence among adults because children often are the source of infection transmission to older family members.

Keep in mind that HAV vaccination for children age 2 to 18 years may still be recommended in your area depending on local circumstances and disease epidemiology.

Hepatitis B

The ACIP recommends that the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) routinely be given to newborns before hospital discharge. This first dose in the 3-dose series should be monovalent HepB and should be delayed only if a physician so orders and if the mother is documented to be hepatitis surface antigen negative. This recommendation is the latest addition to the national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B virus transmission in the United States.1

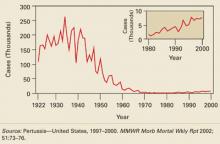

Pertussis

A Practice Alert column last year described the re-emergence of pertussis and the licensure of tetanus and diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) products for use in adolescents and adults.2 There are now 5 new recommendations regarding the use of Tdap.

- A single dose of Tdap should replace the next dose of Td for adults aged 19 to 64 years as part of the every-10-year Td boosting schedule.

- A single dose of Tdap should be administered to adults who have close contact with infants less than 6 months of age. The optimal interval between Tdap and the last Td is 2 years or greater, but shorter intervals are acceptable.

- Women of childbearing age should receive Tdap before conception or postpartum, if they have not previously received Tdap. Tdap is not approved for use during pregnancy.

- All adolescents aged 11 to 12 should receive a single dose of Tdap.

- Adolescents aged 13 to 18 should receive Tdap if they received the last Td more than 5 years previously, or in less than 2 years for special circumstances such as close contact with an infant or in an outbreak.

There are only 2 contraindications to the use of Tdap: a history of anaphylactic reaction to a Tdap vaccine component, or a history of encephalopathy within 7 days of receiving a pertussis vaccine that cannot be attributed to another cause. Precautions include Guillain-Barré syndrome less than 6 weeks after a previous dose of tetanus toxoid, moderate or severe acute illness (with or without fever), unstable neurologic condition, or a history of an Arthus hypersensitivity reaction after a dose of tetanus or diphtheria toxoid.

With the new recommendation for Tdap at age 11 to 12 years, 2 vaccines are now indicated for this age group—the other being quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine.3 The ACIP recommends a wellness visit at this age to facilitate these immunizations.

Varicella

Varicella immune globulin is no longer produced. Post-varicella-exposure prophylaxis is recommended for those who do not have varicella immunity and who are likely to get severe varicella disease. These include immunocompromised persons, neonates, premature infants, and pregnant women. The ACIP now recommends intravenous immune globulin for these situations.

ACIP also recommends that pregnant women with no proof of varicella immunity be screened with a blood test during pregnancy, and those found to be nonimmune should receive varicella vaccine postpartum with the second dose 4 to 8 weeks later. Proof of immunity consists of a history of documented varicella infection or herpes zoster, age-appropriate vaccination, being born before 1966, or a positive serology result for varicella antibody.

A measles-mumps-rubella-varicella combination vaccine (MMRV) is now available and can cut down on the number of injections needed to complete child vaccination recommendations. It will also stimulate more discussion about the potential advantages of a second varicella dose for children under age 13 years, which is currently not recommended.

The TABLE summarizes these new vaccine recommendations by age group. The complete immunization schedule for children and adults can be located on the CDC Web site.4,5 These schedules can be printed and placed in clinic setting to assist physicians and staff to competently fulfill one their most important public health functions, insuring the full immunization of their patient populations.

TABLE

Recent immunization recommendations by age group

| INFANTS AND CHILDREN |

| Hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) as monovalent HepB before discharge from the hospital unless order otherwise by a physicians and the mother is documented to be hepatitis B surface antigen negative. |

| Universal, routine vaccination with hepatitis A vaccine between age 1 to 2 years with 2 doses 6 months apart. |

| ADOLESCENTS |

| Tdap at age 11 to 12 years. |

| Tdap at age 13 to 18 years if the last Td was administered >5 years previously and no previous Tdap administered. In special circumstances the interval from the last Td can be less than 5 years. |

| Wellness visit at age 11 to 12 years to administer both Tdap and meningococcal vaccines. |

| ADULTS |

| Tdap to replace the next scheduled Td booster, one time only. |

| Tdap as single dose for adults caring for children less than age 6 months. |

| PREGNANT WOMEN |

| Screen for varicella immunity in those without proof of immunity. Immunize postpartum those nonimmune. |

| Tdap either during preconception period or immediately postpartum, if no Tdap previously received. |

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected]

1. A Comprehensive Immunization Strategy to Eliminate Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005; 54(RR-16):1–23. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5416a1.htm?s_cid=rr5416a1_e. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Pertussis: A disease re-emerges. J Fam Pract 2005;54:699-703.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Meningococcal vaccine: new product, new recommendations. J Fam Pract 2005;54:324-326.

4. CDC. Recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedule. United States, 2006. Available at: www.immunize.org/cdc/child-schedule.pdf. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

5. CDC. Recommended adult immunization schedule, by vaccine and age group. United States, October 2005—September 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nip/recs/adult-schedule.pdf. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

Vaccines are one of the most important and effective tools for protecting the health of the public and family physicians are instrumental in insuring that vaccine recommendations are implemented. With the development of new vaccines come increasingly complex recommendations. Staying current is challenging.

This column describes the most recent changes to the immunization schedules made by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Hepatitis A

Universal vaccination with hepatitis A virus (HAV) vaccine is now recommended for all children between their first and second birthdays, with 2 doses of vaccine given 6 months apart.

Previously, universal vaccination was recommended only for states and population groups known to have a high prevalence of infection. The recommended age for vaccination varied depending on local circumstances, but the vaccine was not approved for use before the second birthday. Because of the marked success in reducing hepatitis A infection rates in high-prevalence areas, most HAV cases now occur in states without routine vaccination recommendations.

Each year, 5000 to 7000 cases of hepatitis A are reported, and it is estimated that 4 times that number of symptomatic cases occur. The ACIP’s new recommendation is based on recent approval of HAV vaccine for use starting at age 1 year, and on the expected doubling of disease reduction from routine, universal vaccination of children. Moreover, universal vaccination of children is expected to reduce hepatitis A incidence among adults because children often are the source of infection transmission to older family members.

Keep in mind that HAV vaccination for children age 2 to 18 years may still be recommended in your area depending on local circumstances and disease epidemiology.

Hepatitis B

The ACIP recommends that the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) routinely be given to newborns before hospital discharge. This first dose in the 3-dose series should be monovalent HepB and should be delayed only if a physician so orders and if the mother is documented to be hepatitis surface antigen negative. This recommendation is the latest addition to the national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B virus transmission in the United States.1

Pertussis

A Practice Alert column last year described the re-emergence of pertussis and the licensure of tetanus and diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) products for use in adolescents and adults.2 There are now 5 new recommendations regarding the use of Tdap.

- A single dose of Tdap should replace the next dose of Td for adults aged 19 to 64 years as part of the every-10-year Td boosting schedule.

- A single dose of Tdap should be administered to adults who have close contact with infants less than 6 months of age. The optimal interval between Tdap and the last Td is 2 years or greater, but shorter intervals are acceptable.

- Women of childbearing age should receive Tdap before conception or postpartum, if they have not previously received Tdap. Tdap is not approved for use during pregnancy.

- All adolescents aged 11 to 12 should receive a single dose of Tdap.

- Adolescents aged 13 to 18 should receive Tdap if they received the last Td more than 5 years previously, or in less than 2 years for special circumstances such as close contact with an infant or in an outbreak.

There are only 2 contraindications to the use of Tdap: a history of anaphylactic reaction to a Tdap vaccine component, or a history of encephalopathy within 7 days of receiving a pertussis vaccine that cannot be attributed to another cause. Precautions include Guillain-Barré syndrome less than 6 weeks after a previous dose of tetanus toxoid, moderate or severe acute illness (with or without fever), unstable neurologic condition, or a history of an Arthus hypersensitivity reaction after a dose of tetanus or diphtheria toxoid.

With the new recommendation for Tdap at age 11 to 12 years, 2 vaccines are now indicated for this age group—the other being quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine.3 The ACIP recommends a wellness visit at this age to facilitate these immunizations.

Varicella

Varicella immune globulin is no longer produced. Post-varicella-exposure prophylaxis is recommended for those who do not have varicella immunity and who are likely to get severe varicella disease. These include immunocompromised persons, neonates, premature infants, and pregnant women. The ACIP now recommends intravenous immune globulin for these situations.

ACIP also recommends that pregnant women with no proof of varicella immunity be screened with a blood test during pregnancy, and those found to be nonimmune should receive varicella vaccine postpartum with the second dose 4 to 8 weeks later. Proof of immunity consists of a history of documented varicella infection or herpes zoster, age-appropriate vaccination, being born before 1966, or a positive serology result for varicella antibody.

A measles-mumps-rubella-varicella combination vaccine (MMRV) is now available and can cut down on the number of injections needed to complete child vaccination recommendations. It will also stimulate more discussion about the potential advantages of a second varicella dose for children under age 13 years, which is currently not recommended.

The TABLE summarizes these new vaccine recommendations by age group. The complete immunization schedule for children and adults can be located on the CDC Web site.4,5 These schedules can be printed and placed in clinic setting to assist physicians and staff to competently fulfill one their most important public health functions, insuring the full immunization of their patient populations.

TABLE

Recent immunization recommendations by age group

| INFANTS AND CHILDREN |

| Hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) as monovalent HepB before discharge from the hospital unless order otherwise by a physicians and the mother is documented to be hepatitis B surface antigen negative. |

| Universal, routine vaccination with hepatitis A vaccine between age 1 to 2 years with 2 doses 6 months apart. |

| ADOLESCENTS |

| Tdap at age 11 to 12 years. |

| Tdap at age 13 to 18 years if the last Td was administered >5 years previously and no previous Tdap administered. In special circumstances the interval from the last Td can be less than 5 years. |

| Wellness visit at age 11 to 12 years to administer both Tdap and meningococcal vaccines. |

| ADULTS |

| Tdap to replace the next scheduled Td booster, one time only. |

| Tdap as single dose for adults caring for children less than age 6 months. |

| PREGNANT WOMEN |

| Screen for varicella immunity in those without proof of immunity. Immunize postpartum those nonimmune. |

| Tdap either during preconception period or immediately postpartum, if no Tdap previously received. |

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected]

Vaccines are one of the most important and effective tools for protecting the health of the public and family physicians are instrumental in insuring that vaccine recommendations are implemented. With the development of new vaccines come increasingly complex recommendations. Staying current is challenging.

This column describes the most recent changes to the immunization schedules made by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Hepatitis A

Universal vaccination with hepatitis A virus (HAV) vaccine is now recommended for all children between their first and second birthdays, with 2 doses of vaccine given 6 months apart.

Previously, universal vaccination was recommended only for states and population groups known to have a high prevalence of infection. The recommended age for vaccination varied depending on local circumstances, but the vaccine was not approved for use before the second birthday. Because of the marked success in reducing hepatitis A infection rates in high-prevalence areas, most HAV cases now occur in states without routine vaccination recommendations.

Each year, 5000 to 7000 cases of hepatitis A are reported, and it is estimated that 4 times that number of symptomatic cases occur. The ACIP’s new recommendation is based on recent approval of HAV vaccine for use starting at age 1 year, and on the expected doubling of disease reduction from routine, universal vaccination of children. Moreover, universal vaccination of children is expected to reduce hepatitis A incidence among adults because children often are the source of infection transmission to older family members.

Keep in mind that HAV vaccination for children age 2 to 18 years may still be recommended in your area depending on local circumstances and disease epidemiology.

Hepatitis B

The ACIP recommends that the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) routinely be given to newborns before hospital discharge. This first dose in the 3-dose series should be monovalent HepB and should be delayed only if a physician so orders and if the mother is documented to be hepatitis surface antigen negative. This recommendation is the latest addition to the national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B virus transmission in the United States.1

Pertussis

A Practice Alert column last year described the re-emergence of pertussis and the licensure of tetanus and diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) products for use in adolescents and adults.2 There are now 5 new recommendations regarding the use of Tdap.

- A single dose of Tdap should replace the next dose of Td for adults aged 19 to 64 years as part of the every-10-year Td boosting schedule.

- A single dose of Tdap should be administered to adults who have close contact with infants less than 6 months of age. The optimal interval between Tdap and the last Td is 2 years or greater, but shorter intervals are acceptable.

- Women of childbearing age should receive Tdap before conception or postpartum, if they have not previously received Tdap. Tdap is not approved for use during pregnancy.

- All adolescents aged 11 to 12 should receive a single dose of Tdap.

- Adolescents aged 13 to 18 should receive Tdap if they received the last Td more than 5 years previously, or in less than 2 years for special circumstances such as close contact with an infant or in an outbreak.

There are only 2 contraindications to the use of Tdap: a history of anaphylactic reaction to a Tdap vaccine component, or a history of encephalopathy within 7 days of receiving a pertussis vaccine that cannot be attributed to another cause. Precautions include Guillain-Barré syndrome less than 6 weeks after a previous dose of tetanus toxoid, moderate or severe acute illness (with or without fever), unstable neurologic condition, or a history of an Arthus hypersensitivity reaction after a dose of tetanus or diphtheria toxoid.

With the new recommendation for Tdap at age 11 to 12 years, 2 vaccines are now indicated for this age group—the other being quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine.3 The ACIP recommends a wellness visit at this age to facilitate these immunizations.

Varicella

Varicella immune globulin is no longer produced. Post-varicella-exposure prophylaxis is recommended for those who do not have varicella immunity and who are likely to get severe varicella disease. These include immunocompromised persons, neonates, premature infants, and pregnant women. The ACIP now recommends intravenous immune globulin for these situations.

ACIP also recommends that pregnant women with no proof of varicella immunity be screened with a blood test during pregnancy, and those found to be nonimmune should receive varicella vaccine postpartum with the second dose 4 to 8 weeks later. Proof of immunity consists of a history of documented varicella infection or herpes zoster, age-appropriate vaccination, being born before 1966, or a positive serology result for varicella antibody.

A measles-mumps-rubella-varicella combination vaccine (MMRV) is now available and can cut down on the number of injections needed to complete child vaccination recommendations. It will also stimulate more discussion about the potential advantages of a second varicella dose for children under age 13 years, which is currently not recommended.

The TABLE summarizes these new vaccine recommendations by age group. The complete immunization schedule for children and adults can be located on the CDC Web site.4,5 These schedules can be printed and placed in clinic setting to assist physicians and staff to competently fulfill one their most important public health functions, insuring the full immunization of their patient populations.

TABLE

Recent immunization recommendations by age group

| INFANTS AND CHILDREN |

| Hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) as monovalent HepB before discharge from the hospital unless order otherwise by a physicians and the mother is documented to be hepatitis B surface antigen negative. |

| Universal, routine vaccination with hepatitis A vaccine between age 1 to 2 years with 2 doses 6 months apart. |

| ADOLESCENTS |

| Tdap at age 11 to 12 years. |

| Tdap at age 13 to 18 years if the last Td was administered >5 years previously and no previous Tdap administered. In special circumstances the interval from the last Td can be less than 5 years. |

| Wellness visit at age 11 to 12 years to administer both Tdap and meningococcal vaccines. |

| ADULTS |

| Tdap to replace the next scheduled Td booster, one time only. |

| Tdap as single dose for adults caring for children less than age 6 months. |

| PREGNANT WOMEN |

| Screen for varicella immunity in those without proof of immunity. Immunize postpartum those nonimmune. |

| Tdap either during preconception period or immediately postpartum, if no Tdap previously received. |

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected]

1. A Comprehensive Immunization Strategy to Eliminate Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005; 54(RR-16):1–23. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5416a1.htm?s_cid=rr5416a1_e. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Pertussis: A disease re-emerges. J Fam Pract 2005;54:699-703.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Meningococcal vaccine: new product, new recommendations. J Fam Pract 2005;54:324-326.

4. CDC. Recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedule. United States, 2006. Available at: www.immunize.org/cdc/child-schedule.pdf. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

5. CDC. Recommended adult immunization schedule, by vaccine and age group. United States, October 2005—September 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nip/recs/adult-schedule.pdf. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

1. A Comprehensive Immunization Strategy to Eliminate Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005; 54(RR-16):1–23. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5416a1.htm?s_cid=rr5416a1_e. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Pertussis: A disease re-emerges. J Fam Pract 2005;54:699-703.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Meningococcal vaccine: new product, new recommendations. J Fam Pract 2005;54:324-326.

4. CDC. Recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedule. United States, 2006. Available at: www.immunize.org/cdc/child-schedule.pdf. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

5. CDC. Recommended adult immunization schedule, by vaccine and age group. United States, October 2005—September 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nip/recs/adult-schedule.pdf. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

Disaster medical response: Maximizing your effectiveness

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, physicians and other health professionals volunteered for deployment to the affected area to provide medical services. The frustrating reality most of them encountered was the incapacity of those in charge to use the number of professional volunteers expressing interest.

Lesson: Build the infrastructure to support professional volunteerism

Untrained volunteers, though well intentioned, are often not that helpful. The immediate needs of a disaster area relate to public health and other safety issues. Until a proper infrastructure is re-established, general medical services cannot be provided. Physician services are most effectively provided in collaboration with, or as part of, an organized local response agency.

First things first

In addition to immediate loss of life and injuries caused by a disaster—natural or man-made (eg, war, terrorism)—mass disruption of the local infrastructure and relocation of a large segment of the population pose ongoing threats to health. The most crucial services to re-establish include adequate clean water, sanitation, food supplies, vector control (eg, insects and rodents), shelter, and immunizations. Also essential is establishing surveillance systems to rapidly assess needs and to detect disease trends.

Tasks that can wait

Contrary to what is commonly believed and stated in the press, rapid burial or cremation of cadavers is not an immediate need. Bodies almost never pose a serious public health threat. Moreover, rapid disposal of bodies can deprive families of knowing what happened to their relatives and cause psychological harm as well as legal and economic hardships.

Epidemics can occur but they usually result from respiratory or gastrointestinal pathogens caused by poor sanitation, inadequate water supplies, and overcrowding in inadequate shelters. Public health surveillance systems are important for detecting, tracking, and controlling such outbreaks.

Physicians as volunteers

Volunteer physicians are most effective following a disaster if they understand the importance of re-establishing the needed infrastructure, and if they arrive on scene as part of an organized response, having been trained in disaster medicine and public health. Disaster Medicine is becoming a recognized field of medicine with its own set of skills and an evolving literature base and training materials and courses.

After the immediate post-disaster period, it often takes a prolonged period of time to re-establish basic medical services. During this phase, volunteers continue to be needed but are harder to recruit. Mental health professionals are especially useful to assist with the posttraumatic stress and grief issues common after disasters.

If you would like to become part of organized disaster response team, you have several options.

If volunteering for deployment to other regions is not something you’re likely to do, but you live in an area vulnerable to, say, tornadoes or earthquakes, there is plenty you can do to prepare for disaster.

The AMA offers 3 courses in basic disaster response: Core Disaster Life Support (CDLS); Basic Disaster Life Support (BDLS); and Advanced Disaster Life Support (ADLS). Details are available at the AMA website: www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/12606.html.

The CDC offers web-based training materials in the medical and public health response to an array of natural and man-made disasters (available on the Web at www.phppo.cdc.gov/phtn/default.asp).

You can also assist your local health department in planning for the most likely disasters in your area.

The Medical Reserve Corps

The Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) is a program started by the federal government after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. It is part of the Citizen Corps, which is one component of the USA Freedom Corps (www.usafreedomcorps.gov). The purpose of the MRC is to organize local groups of medical and public health professionals to prepare for and respond to local and national emergency needs.

The Office of the Surgeon General coordinates the MRC program. This coordinating function includes recognizing and listing MRCs, offering technical assistance, serving as a clearinghouse of information for local MRCs, and offering training. Physicians interested in joining a local MRC can check on the MRC home page (www.medicalreservecorps.gov) to see if one has been organized their area. If no MRC exists in your area, you can help start one with the approval of the local Citizen Corps Council (www.citizencorps.gov/councils).

Since the MRC is a federal program—albeit relying on local organization and initiative—it is not clear how well local MRC units are fitting into the local, state, and national disaster relief infrastructure. Reportedly at least 20 MRC units assisted with relief efforts in Louisiana after Katrina. The MRC is intended to serve as a local resource and to augment the public health workforce should mass immunization or antibiotic distribution be needed.

Disaster Medical Assistance Teams

Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs) are part of the National Disaster Medical System, under the auspices of the Department of Homeland Security. The role of these teams is to provide medical care in a disaster area.

As stated in DMAT promotional material, “DMATs deploy to disaster sites with sufficient supplies and equipment to sustain themselves for a period of 72 hours while providing medical care at a fixed or temporary medical care site.” In incidents with large numbers of casualties, DMATs responsibilities include “triaging patients, providing high-quality medical care despite the adverse and austere environment often found at a disaster site, and preparing patients for evacuation.” DMATs may also provide primary medical care or may augment overloaded local health care staffs.

Under those unusual circumstances when victims of a disaster are evacuated to another location for their medical care, “DMATs may be activated to support patient reception and disposition of patients to hospitals. DMATs are designed to be a rapid-response element to supplement local medical care until other Federal or contract resources can be mobilized, or the situation is resolved.”

DMATs are organized by a local sponsor—a medical center, local public health agency, or a nonprofit organization. The responsibilities of the sponsor include recruiting DMAT team members, training, and organizing the dispatch of team members if called upon. Members of DMATs become temporary federal employees when deployed; this provides them liability protection through the Federal Tort Claims Act. In addition, professional licenses of federal employees are recognized by states, freeing DMAT team members from state licensing concerns.

To become a member of a DMAT, you must fill out a Federal Job Application form, be interviewed, and accepted as a team member. The NDMS has 10 regional offices (detailed at www.oep-ndms.dhhs.gov/region_1.html) where information can be found about existing DMAT teams and how to form a team. The DMAT home page is www.oep-ndms.dhhs.gov/dmat.html.

Search-and-rescue teams

Local fire departments and law enforcement departments frequently have search-and-rescue teams that can be called on to respond to disasters throughout the country. When these teams are deployed, they should take along medical personnel to attend to the needs of the responders. The medical professional should be prepared to screen responders and provide medical clearance before they deploy, provide urgent care medical services to responders, and ensure that measures are taken to prevent illness among team members.

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected]

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, physicians and other health professionals volunteered for deployment to the affected area to provide medical services. The frustrating reality most of them encountered was the incapacity of those in charge to use the number of professional volunteers expressing interest.

Lesson: Build the infrastructure to support professional volunteerism

Untrained volunteers, though well intentioned, are often not that helpful. The immediate needs of a disaster area relate to public health and other safety issues. Until a proper infrastructure is re-established, general medical services cannot be provided. Physician services are most effectively provided in collaboration with, or as part of, an organized local response agency.

First things first

In addition to immediate loss of life and injuries caused by a disaster—natural or man-made (eg, war, terrorism)—mass disruption of the local infrastructure and relocation of a large segment of the population pose ongoing threats to health. The most crucial services to re-establish include adequate clean water, sanitation, food supplies, vector control (eg, insects and rodents), shelter, and immunizations. Also essential is establishing surveillance systems to rapidly assess needs and to detect disease trends.

Tasks that can wait

Contrary to what is commonly believed and stated in the press, rapid burial or cremation of cadavers is not an immediate need. Bodies almost never pose a serious public health threat. Moreover, rapid disposal of bodies can deprive families of knowing what happened to their relatives and cause psychological harm as well as legal and economic hardships.

Epidemics can occur but they usually result from respiratory or gastrointestinal pathogens caused by poor sanitation, inadequate water supplies, and overcrowding in inadequate shelters. Public health surveillance systems are important for detecting, tracking, and controlling such outbreaks.

Physicians as volunteers

Volunteer physicians are most effective following a disaster if they understand the importance of re-establishing the needed infrastructure, and if they arrive on scene as part of an organized response, having been trained in disaster medicine and public health. Disaster Medicine is becoming a recognized field of medicine with its own set of skills and an evolving literature base and training materials and courses.

After the immediate post-disaster period, it often takes a prolonged period of time to re-establish basic medical services. During this phase, volunteers continue to be needed but are harder to recruit. Mental health professionals are especially useful to assist with the posttraumatic stress and grief issues common after disasters.

If you would like to become part of organized disaster response team, you have several options.

If volunteering for deployment to other regions is not something you’re likely to do, but you live in an area vulnerable to, say, tornadoes or earthquakes, there is plenty you can do to prepare for disaster.

The AMA offers 3 courses in basic disaster response: Core Disaster Life Support (CDLS); Basic Disaster Life Support (BDLS); and Advanced Disaster Life Support (ADLS). Details are available at the AMA website: www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/12606.html.

The CDC offers web-based training materials in the medical and public health response to an array of natural and man-made disasters (available on the Web at www.phppo.cdc.gov/phtn/default.asp).

You can also assist your local health department in planning for the most likely disasters in your area.

The Medical Reserve Corps

The Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) is a program started by the federal government after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. It is part of the Citizen Corps, which is one component of the USA Freedom Corps (www.usafreedomcorps.gov). The purpose of the MRC is to organize local groups of medical and public health professionals to prepare for and respond to local and national emergency needs.

The Office of the Surgeon General coordinates the MRC program. This coordinating function includes recognizing and listing MRCs, offering technical assistance, serving as a clearinghouse of information for local MRCs, and offering training. Physicians interested in joining a local MRC can check on the MRC home page (www.medicalreservecorps.gov) to see if one has been organized their area. If no MRC exists in your area, you can help start one with the approval of the local Citizen Corps Council (www.citizencorps.gov/councils).

Since the MRC is a federal program—albeit relying on local organization and initiative—it is not clear how well local MRC units are fitting into the local, state, and national disaster relief infrastructure. Reportedly at least 20 MRC units assisted with relief efforts in Louisiana after Katrina. The MRC is intended to serve as a local resource and to augment the public health workforce should mass immunization or antibiotic distribution be needed.

Disaster Medical Assistance Teams

Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs) are part of the National Disaster Medical System, under the auspices of the Department of Homeland Security. The role of these teams is to provide medical care in a disaster area.

As stated in DMAT promotional material, “DMATs deploy to disaster sites with sufficient supplies and equipment to sustain themselves for a period of 72 hours while providing medical care at a fixed or temporary medical care site.” In incidents with large numbers of casualties, DMATs responsibilities include “triaging patients, providing high-quality medical care despite the adverse and austere environment often found at a disaster site, and preparing patients for evacuation.” DMATs may also provide primary medical care or may augment overloaded local health care staffs.

Under those unusual circumstances when victims of a disaster are evacuated to another location for their medical care, “DMATs may be activated to support patient reception and disposition of patients to hospitals. DMATs are designed to be a rapid-response element to supplement local medical care until other Federal or contract resources can be mobilized, or the situation is resolved.”

DMATs are organized by a local sponsor—a medical center, local public health agency, or a nonprofit organization. The responsibilities of the sponsor include recruiting DMAT team members, training, and organizing the dispatch of team members if called upon. Members of DMATs become temporary federal employees when deployed; this provides them liability protection through the Federal Tort Claims Act. In addition, professional licenses of federal employees are recognized by states, freeing DMAT team members from state licensing concerns.

To become a member of a DMAT, you must fill out a Federal Job Application form, be interviewed, and accepted as a team member. The NDMS has 10 regional offices (detailed at www.oep-ndms.dhhs.gov/region_1.html) where information can be found about existing DMAT teams and how to form a team. The DMAT home page is www.oep-ndms.dhhs.gov/dmat.html.

Search-and-rescue teams

Local fire departments and law enforcement departments frequently have search-and-rescue teams that can be called on to respond to disasters throughout the country. When these teams are deployed, they should take along medical personnel to attend to the needs of the responders. The medical professional should be prepared to screen responders and provide medical clearance before they deploy, provide urgent care medical services to responders, and ensure that measures are taken to prevent illness among team members.

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected]

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, physicians and other health professionals volunteered for deployment to the affected area to provide medical services. The frustrating reality most of them encountered was the incapacity of those in charge to use the number of professional volunteers expressing interest.

Lesson: Build the infrastructure to support professional volunteerism

Untrained volunteers, though well intentioned, are often not that helpful. The immediate needs of a disaster area relate to public health and other safety issues. Until a proper infrastructure is re-established, general medical services cannot be provided. Physician services are most effectively provided in collaboration with, or as part of, an organized local response agency.

First things first

In addition to immediate loss of life and injuries caused by a disaster—natural or man-made (eg, war, terrorism)—mass disruption of the local infrastructure and relocation of a large segment of the population pose ongoing threats to health. The most crucial services to re-establish include adequate clean water, sanitation, food supplies, vector control (eg, insects and rodents), shelter, and immunizations. Also essential is establishing surveillance systems to rapidly assess needs and to detect disease trends.

Tasks that can wait

Contrary to what is commonly believed and stated in the press, rapid burial or cremation of cadavers is not an immediate need. Bodies almost never pose a serious public health threat. Moreover, rapid disposal of bodies can deprive families of knowing what happened to their relatives and cause psychological harm as well as legal and economic hardships.

Epidemics can occur but they usually result from respiratory or gastrointestinal pathogens caused by poor sanitation, inadequate water supplies, and overcrowding in inadequate shelters. Public health surveillance systems are important for detecting, tracking, and controlling such outbreaks.

Physicians as volunteers

Volunteer physicians are most effective following a disaster if they understand the importance of re-establishing the needed infrastructure, and if they arrive on scene as part of an organized response, having been trained in disaster medicine and public health. Disaster Medicine is becoming a recognized field of medicine with its own set of skills and an evolving literature base and training materials and courses.

After the immediate post-disaster period, it often takes a prolonged period of time to re-establish basic medical services. During this phase, volunteers continue to be needed but are harder to recruit. Mental health professionals are especially useful to assist with the posttraumatic stress and grief issues common after disasters.

If you would like to become part of organized disaster response team, you have several options.

If volunteering for deployment to other regions is not something you’re likely to do, but you live in an area vulnerable to, say, tornadoes or earthquakes, there is plenty you can do to prepare for disaster.

The AMA offers 3 courses in basic disaster response: Core Disaster Life Support (CDLS); Basic Disaster Life Support (BDLS); and Advanced Disaster Life Support (ADLS). Details are available at the AMA website: www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/12606.html.

The CDC offers web-based training materials in the medical and public health response to an array of natural and man-made disasters (available on the Web at www.phppo.cdc.gov/phtn/default.asp).

You can also assist your local health department in planning for the most likely disasters in your area.

The Medical Reserve Corps

The Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) is a program started by the federal government after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. It is part of the Citizen Corps, which is one component of the USA Freedom Corps (www.usafreedomcorps.gov). The purpose of the MRC is to organize local groups of medical and public health professionals to prepare for and respond to local and national emergency needs.

The Office of the Surgeon General coordinates the MRC program. This coordinating function includes recognizing and listing MRCs, offering technical assistance, serving as a clearinghouse of information for local MRCs, and offering training. Physicians interested in joining a local MRC can check on the MRC home page (www.medicalreservecorps.gov) to see if one has been organized their area. If no MRC exists in your area, you can help start one with the approval of the local Citizen Corps Council (www.citizencorps.gov/councils).

Since the MRC is a federal program—albeit relying on local organization and initiative—it is not clear how well local MRC units are fitting into the local, state, and national disaster relief infrastructure. Reportedly at least 20 MRC units assisted with relief efforts in Louisiana after Katrina. The MRC is intended to serve as a local resource and to augment the public health workforce should mass immunization or antibiotic distribution be needed.

Disaster Medical Assistance Teams

Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs) are part of the National Disaster Medical System, under the auspices of the Department of Homeland Security. The role of these teams is to provide medical care in a disaster area.

As stated in DMAT promotional material, “DMATs deploy to disaster sites with sufficient supplies and equipment to sustain themselves for a period of 72 hours while providing medical care at a fixed or temporary medical care site.” In incidents with large numbers of casualties, DMATs responsibilities include “triaging patients, providing high-quality medical care despite the adverse and austere environment often found at a disaster site, and preparing patients for evacuation.” DMATs may also provide primary medical care or may augment overloaded local health care staffs.

Under those unusual circumstances when victims of a disaster are evacuated to another location for their medical care, “DMATs may be activated to support patient reception and disposition of patients to hospitals. DMATs are designed to be a rapid-response element to supplement local medical care until other Federal or contract resources can be mobilized, or the situation is resolved.”

DMATs are organized by a local sponsor—a medical center, local public health agency, or a nonprofit organization. The responsibilities of the sponsor include recruiting DMAT team members, training, and organizing the dispatch of team members if called upon. Members of DMATs become temporary federal employees when deployed; this provides them liability protection through the Federal Tort Claims Act. In addition, professional licenses of federal employees are recognized by states, freeing DMAT team members from state licensing concerns.

To become a member of a DMAT, you must fill out a Federal Job Application form, be interviewed, and accepted as a team member. The NDMS has 10 regional offices (detailed at www.oep-ndms.dhhs.gov/region_1.html) where information can be found about existing DMAT teams and how to form a team. The DMAT home page is www.oep-ndms.dhhs.gov/dmat.html.

Search-and-rescue teams

Local fire departments and law enforcement departments frequently have search-and-rescue teams that can be called on to respond to disasters throughout the country. When these teams are deployed, they should take along medical personnel to attend to the needs of the responders. The medical professional should be prepared to screen responders and provide medical clearance before they deploy, provide urgent care medical services to responders, and ensure that measures are taken to prevent illness among team members.

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected]

Medicare prescription drug bill: Resources to inform and equip your patients

On November 15, 2005, enrollment opened for Medicare’s new prescription drug program. You have most likely been asked by patients for help in understanding the complexity of the options. No small task. Though there is a lot to disagree with in the way the Medicare drug benefit has been crafted, it’s what we now have and many beneficiaries can benefit from it. In addition to knowing which agencies in your communities serve seniors, you can better equip your elderly patients to make decisions by becoming familiar with web sites and other resources listed in this article.

Confusion reigns

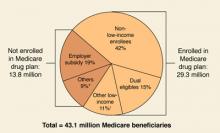

By May 15, 2006, when the initial enrollment period ends, the government predicts that over 29 million of 43 million eligible beneficiaries will have signed up for the new benefit, with another 9 to 10 million beneficiaries maintaining their drug coverage through an employer-sponsored plan (FIGURE 1).

Whether these predictions come to pass is an open question. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey from late October 2005 found that 60% of senior citizens did not understand the benefit and 50% thought it would not help them. Of those surveyed, 43% did not know whether they would enroll, 37% said they would not enroll, and only 20% said they would definitely enroll.

One problem for seniors is that unlike the traditional Medicare program in which there are only 2 choices—whether to sign up for the traditional fee-for-service plan or a managed care plan—the new drug plan is administered by a large number of private plans that cover different medications and charge different prices for them. Seniors who said they understood the drug benefit (a minority) were more likely to view the program favorably. Perhaps most relevant for physicians is that seniors said they would likely turn to the Medicare program (33%), their personal doctor (32%), or their pharmacist (25%) for assistance.1

A quick review

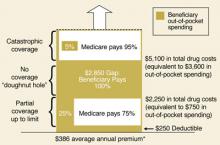

Readers may recall that the prescription drug benefit portion of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 includes a premium (current national average of $32/month), an annual deductible, copays, and the infamous “donut hole” (FIGURE 2).2

With the program beginning in January 2006, however, there is more to keep in mind than the costs to beneficiaries: for example, who will be offering the benefit, what medications will be covered (formularies), and the effect on dual-eligibles (beneficiaries covered by both Medicare and Medicaid), so-called “Medigap” policyholders, and low-income beneficiaries.

FIGURE 1

Estimated Medicare prescription drug benefit participation, 2006

* “Others” not enrolled includes federal retirees with drug coverage through FEHBP or TRICARE, and those who lack drug coverage.

† “Other low-income” includes non-dual-eligibles with incomes <150% FPL.

Source: HHS OACT, MMA final rule, January 2005.

FIGURE 2

Standard Medicare prescription drug benefit, 2006

* Annual amount based on $32.20 national average beneficiary premium (CMS, August 2005)

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation illustration of standard Medicare drug benefit described in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003

Who offers the plans

Medicare beneficiaries can obtain the drug benefit in either of 2 ways: through a stand-alone prescription drug plan (PDP) that covers only drugs (with the usual medical benefits obtained through the traditional Medicare program), or through a Medicare Advantage plan (MA) that is essentially a managed care plan, providing drug coverage and medical benefits in place of the traditional Medicare program.

The Bush administration has long promoted MA plans as a way to better control Medicare costs, even though the federal government currently spends more per MA beneficiary than for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. MA plans can offer additional benefits and adjust premiums to attract customers—drug benefits for a lower premium, vision benefits, and dental benefits. However, there may be limits on using providers outside the MA plan’s network of physicians and hospitals.3

Drug plans must cover at least 2 drugs in each therapeutic class approved by Medicare, but they may use tiered cost-sharing (eg, generics and brand-name drugs in different tiers) and other management tools as long as they meet the minimum requirements of the overall bill. The decision by the White House and Congress to approve the privatization of the drug benefit has led to the current situation in which multiple private plans are competing for enrollment in each geographic region and offering different drugs for different prices. For instance, in my county, there are 7 MA plans and 43 PDP plans being offered. This makes the system overly complex and confusing. In addition, the Medicare Modernization Act allows plans to increase the copays or even end coverage of specific drugs with 60 days notice.

Dual eligibles and low-income beneficiaries

The Medicare Modernization Act provided additional assistance to persons of limited means—those currently covered by Medicare and Medicaid plans who receive their medications through Medicaid (the dual-eligibles) and those who have limited income and resources but are only covered by Medicare. The former group will automatically be enrolled into PDPs if they do not sign up on their own, and they will pay reduced fees for their medications. The states, in turn, will reimburse the federal government for the drug cost savings gained by their Medicaid programs.

Other low-income individuals may also be eligible for drug benefit subsidies based on their income and assets (TABLE). Clearly, the Medicare Modernization Act offers significant drug benefits to beneficiaries of limited means. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projects that 10.9 million beneficiaries will receive low-income subsidies out of 14.5 million eligible.

TABLE

Medicare prescription drug benefit subsidies for low-income beneficiaries, 2006

| LOW-INCOME SUBSIDY LEVEL | PREMIUM | MONTHLY DEDUCTIBLE | ANNUAL COPAYMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-benefit dual eligibles Income <100% of poverty ($9750 individual; $12,830/couple) | $0 | $0 | $1/generic, $3/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Full-benefit dual eligibles Income ≥100% of poverty | $0 | $0 | $2/generic, $5/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Institutionalized full-benefit dual eligibles | $0 | $0 | No copays |

| Individuals with income <135% of poverty ($12,920 individuals, $17,321/couple) and assets <$6000/individual; $9000/couple | $0 | $0 | $2/generic, $5/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Individuals with income 135%–150% of poverty ($12,920–$14,355 individuals, $17,321–$19,245/couple) and assets <$10,000/individual, $20,000/couple | Sliding scale up to $32.20* | $50 | 15% of total costs up to $5100; $2/generic, $5/brand-name thereafter |

| Note: Poverty-level dollar amounts are for 2005. Additional assests of up to $1500/individual and $3000/couple for funeral or burial expenses are permitted. *$32.20 is the national monthly Part D base beneficiary premium for 2006. | |||

| Source: Kaiser Family Foundation summary of Medicare prescription drug benefit low-income subsidies in 2006. | |||

Medigap and employer-sponsored plans

Many current beneficiaries have Medigap insurance policies, which cover part or all of the financial holes in the traditional Medicare plan—eg, deductibles, copays, and other benefits such as drug coverage. Beginning in January 2006, new policies that include drug coverage can no longer be issued. Policyholders can keep their current Medigap policies that cover medications; however, these are generally not considered equivalent to the new coverage. In addition, Medicare will provide subsidies to employers to encourage them to continue any current retiree plans that provide drug coverage comparable to the new plans.4

Enrollment

While the new drug plans start on January 1, 2006, the initial enrollment period runs until May 15, 2006. Beneficiaries who enroll after that time and do not currently have drug coverage as good as the new Medicare drug benefit will pay a higher premium equal to 1% of the average monthly premium for each month they delay enrollment. Those who enroll may change plans one time between December 31, 2005 and May 15, 2006. After May 15, the next enrollment period will be from November 15 to December 31, 2006. Any enrollee can change plans during that time.

In order to assist beneficiaries in making a decision about whether to enroll in a Medicare drug plan and which to choose, the federal government, assisted by a number of medical organizations (such as the AAFP) and nonprofits like the local Area Agencies on Aging, is providing seniors with information in a variety of formats. Beneficiaries should all have received a booklet, “Medicare and You,” in October 2005. There is a 24-hour telephone help line, 1-800-MEDICARE, that has automated answers and can provide access to a real person.

Finally, there is the Internet: www.medicare.gov. While 3 of 4 seniors have never been online, this is the best method to locate available plans in your area, find out which specific medications are included in each plan, and try to compare costs.5 For many seniors, it will be worth asking family members, friends, or community agencies for help in navigating the web site and the information it contains.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Kaiser Family Foundation news release. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/med111005nr.cfm. Accessed on November 21, 2005.

2. Henley E. What the new Medicare prescription drug bill may mean for providers and patients. J Fam Pract 2004;53:389-392.

3. Fuhrmans V, Lueck S. Insurers sweeten health plans for seniors. Wall Street Journal, November 8, 2005.

4. The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/7044-02.cfm. Accessed on December 4, 2005.

5. Glendinning D. Patients look to doctors for help on Medicare drug plans. AMA News, December 5, 2005.

On November 15, 2005, enrollment opened for Medicare’s new prescription drug program. You have most likely been asked by patients for help in understanding the complexity of the options. No small task. Though there is a lot to disagree with in the way the Medicare drug benefit has been crafted, it’s what we now have and many beneficiaries can benefit from it. In addition to knowing which agencies in your communities serve seniors, you can better equip your elderly patients to make decisions by becoming familiar with web sites and other resources listed in this article.

Confusion reigns

By May 15, 2006, when the initial enrollment period ends, the government predicts that over 29 million of 43 million eligible beneficiaries will have signed up for the new benefit, with another 9 to 10 million beneficiaries maintaining their drug coverage through an employer-sponsored plan (FIGURE 1).

Whether these predictions come to pass is an open question. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey from late October 2005 found that 60% of senior citizens did not understand the benefit and 50% thought it would not help them. Of those surveyed, 43% did not know whether they would enroll, 37% said they would not enroll, and only 20% said they would definitely enroll.

One problem for seniors is that unlike the traditional Medicare program in which there are only 2 choices—whether to sign up for the traditional fee-for-service plan or a managed care plan—the new drug plan is administered by a large number of private plans that cover different medications and charge different prices for them. Seniors who said they understood the drug benefit (a minority) were more likely to view the program favorably. Perhaps most relevant for physicians is that seniors said they would likely turn to the Medicare program (33%), their personal doctor (32%), or their pharmacist (25%) for assistance.1

A quick review

Readers may recall that the prescription drug benefit portion of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 includes a premium (current national average of $32/month), an annual deductible, copays, and the infamous “donut hole” (FIGURE 2).2

With the program beginning in January 2006, however, there is more to keep in mind than the costs to beneficiaries: for example, who will be offering the benefit, what medications will be covered (formularies), and the effect on dual-eligibles (beneficiaries covered by both Medicare and Medicaid), so-called “Medigap” policyholders, and low-income beneficiaries.

FIGURE 1

Estimated Medicare prescription drug benefit participation, 2006

* “Others” not enrolled includes federal retirees with drug coverage through FEHBP or TRICARE, and those who lack drug coverage.

† “Other low-income” includes non-dual-eligibles with incomes <150% FPL.

Source: HHS OACT, MMA final rule, January 2005.

FIGURE 2

Standard Medicare prescription drug benefit, 2006

* Annual amount based on $32.20 national average beneficiary premium (CMS, August 2005)

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation illustration of standard Medicare drug benefit described in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003

Who offers the plans

Medicare beneficiaries can obtain the drug benefit in either of 2 ways: through a stand-alone prescription drug plan (PDP) that covers only drugs (with the usual medical benefits obtained through the traditional Medicare program), or through a Medicare Advantage plan (MA) that is essentially a managed care plan, providing drug coverage and medical benefits in place of the traditional Medicare program.

The Bush administration has long promoted MA plans as a way to better control Medicare costs, even though the federal government currently spends more per MA beneficiary than for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. MA plans can offer additional benefits and adjust premiums to attract customers—drug benefits for a lower premium, vision benefits, and dental benefits. However, there may be limits on using providers outside the MA plan’s network of physicians and hospitals.3

Drug plans must cover at least 2 drugs in each therapeutic class approved by Medicare, but they may use tiered cost-sharing (eg, generics and brand-name drugs in different tiers) and other management tools as long as they meet the minimum requirements of the overall bill. The decision by the White House and Congress to approve the privatization of the drug benefit has led to the current situation in which multiple private plans are competing for enrollment in each geographic region and offering different drugs for different prices. For instance, in my county, there are 7 MA plans and 43 PDP plans being offered. This makes the system overly complex and confusing. In addition, the Medicare Modernization Act allows plans to increase the copays or even end coverage of specific drugs with 60 days notice.

Dual eligibles and low-income beneficiaries

The Medicare Modernization Act provided additional assistance to persons of limited means—those currently covered by Medicare and Medicaid plans who receive their medications through Medicaid (the dual-eligibles) and those who have limited income and resources but are only covered by Medicare. The former group will automatically be enrolled into PDPs if they do not sign up on their own, and they will pay reduced fees for their medications. The states, in turn, will reimburse the federal government for the drug cost savings gained by their Medicaid programs.

Other low-income individuals may also be eligible for drug benefit subsidies based on their income and assets (TABLE). Clearly, the Medicare Modernization Act offers significant drug benefits to beneficiaries of limited means. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projects that 10.9 million beneficiaries will receive low-income subsidies out of 14.5 million eligible.

TABLE

Medicare prescription drug benefit subsidies for low-income beneficiaries, 2006

| LOW-INCOME SUBSIDY LEVEL | PREMIUM | MONTHLY DEDUCTIBLE | ANNUAL COPAYMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-benefit dual eligibles Income <100% of poverty ($9750 individual; $12,830/couple) | $0 | $0 | $1/generic, $3/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Full-benefit dual eligibles Income ≥100% of poverty | $0 | $0 | $2/generic, $5/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Institutionalized full-benefit dual eligibles | $0 | $0 | No copays |

| Individuals with income <135% of poverty ($12,920 individuals, $17,321/couple) and assets <$6000/individual; $9000/couple | $0 | $0 | $2/generic, $5/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Individuals with income 135%–150% of poverty ($12,920–$14,355 individuals, $17,321–$19,245/couple) and assets <$10,000/individual, $20,000/couple | Sliding scale up to $32.20* | $50 | 15% of total costs up to $5100; $2/generic, $5/brand-name thereafter |

| Note: Poverty-level dollar amounts are for 2005. Additional assests of up to $1500/individual and $3000/couple for funeral or burial expenses are permitted. *$32.20 is the national monthly Part D base beneficiary premium for 2006. | |||

| Source: Kaiser Family Foundation summary of Medicare prescription drug benefit low-income subsidies in 2006. | |||

Medigap and employer-sponsored plans

Many current beneficiaries have Medigap insurance policies, which cover part or all of the financial holes in the traditional Medicare plan—eg, deductibles, copays, and other benefits such as drug coverage. Beginning in January 2006, new policies that include drug coverage can no longer be issued. Policyholders can keep their current Medigap policies that cover medications; however, these are generally not considered equivalent to the new coverage. In addition, Medicare will provide subsidies to employers to encourage them to continue any current retiree plans that provide drug coverage comparable to the new plans.4

Enrollment

While the new drug plans start on January 1, 2006, the initial enrollment period runs until May 15, 2006. Beneficiaries who enroll after that time and do not currently have drug coverage as good as the new Medicare drug benefit will pay a higher premium equal to 1% of the average monthly premium for each month they delay enrollment. Those who enroll may change plans one time between December 31, 2005 and May 15, 2006. After May 15, the next enrollment period will be from November 15 to December 31, 2006. Any enrollee can change plans during that time.

In order to assist beneficiaries in making a decision about whether to enroll in a Medicare drug plan and which to choose, the federal government, assisted by a number of medical organizations (such as the AAFP) and nonprofits like the local Area Agencies on Aging, is providing seniors with information in a variety of formats. Beneficiaries should all have received a booklet, “Medicare and You,” in October 2005. There is a 24-hour telephone help line, 1-800-MEDICARE, that has automated answers and can provide access to a real person.

Finally, there is the Internet: www.medicare.gov. While 3 of 4 seniors have never been online, this is the best method to locate available plans in your area, find out which specific medications are included in each plan, and try to compare costs.5 For many seniors, it will be worth asking family members, friends, or community agencies for help in navigating the web site and the information it contains.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

On November 15, 2005, enrollment opened for Medicare’s new prescription drug program. You have most likely been asked by patients for help in understanding the complexity of the options. No small task. Though there is a lot to disagree with in the way the Medicare drug benefit has been crafted, it’s what we now have and many beneficiaries can benefit from it. In addition to knowing which agencies in your communities serve seniors, you can better equip your elderly patients to make decisions by becoming familiar with web sites and other resources listed in this article.

Confusion reigns

By May 15, 2006, when the initial enrollment period ends, the government predicts that over 29 million of 43 million eligible beneficiaries will have signed up for the new benefit, with another 9 to 10 million beneficiaries maintaining their drug coverage through an employer-sponsored plan (FIGURE 1).

Whether these predictions come to pass is an open question. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey from late October 2005 found that 60% of senior citizens did not understand the benefit and 50% thought it would not help them. Of those surveyed, 43% did not know whether they would enroll, 37% said they would not enroll, and only 20% said they would definitely enroll.

One problem for seniors is that unlike the traditional Medicare program in which there are only 2 choices—whether to sign up for the traditional fee-for-service plan or a managed care plan—the new drug plan is administered by a large number of private plans that cover different medications and charge different prices for them. Seniors who said they understood the drug benefit (a minority) were more likely to view the program favorably. Perhaps most relevant for physicians is that seniors said they would likely turn to the Medicare program (33%), their personal doctor (32%), or their pharmacist (25%) for assistance.1

A quick review

Readers may recall that the prescription drug benefit portion of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 includes a premium (current national average of $32/month), an annual deductible, copays, and the infamous “donut hole” (FIGURE 2).2

With the program beginning in January 2006, however, there is more to keep in mind than the costs to beneficiaries: for example, who will be offering the benefit, what medications will be covered (formularies), and the effect on dual-eligibles (beneficiaries covered by both Medicare and Medicaid), so-called “Medigap” policyholders, and low-income beneficiaries.

FIGURE 1

Estimated Medicare prescription drug benefit participation, 2006

* “Others” not enrolled includes federal retirees with drug coverage through FEHBP or TRICARE, and those who lack drug coverage.

† “Other low-income” includes non-dual-eligibles with incomes <150% FPL.

Source: HHS OACT, MMA final rule, January 2005.

FIGURE 2

Standard Medicare prescription drug benefit, 2006

* Annual amount based on $32.20 national average beneficiary premium (CMS, August 2005)

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation illustration of standard Medicare drug benefit described in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003

Who offers the plans

Medicare beneficiaries can obtain the drug benefit in either of 2 ways: through a stand-alone prescription drug plan (PDP) that covers only drugs (with the usual medical benefits obtained through the traditional Medicare program), or through a Medicare Advantage plan (MA) that is essentially a managed care plan, providing drug coverage and medical benefits in place of the traditional Medicare program.

The Bush administration has long promoted MA plans as a way to better control Medicare costs, even though the federal government currently spends more per MA beneficiary than for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. MA plans can offer additional benefits and adjust premiums to attract customers—drug benefits for a lower premium, vision benefits, and dental benefits. However, there may be limits on using providers outside the MA plan’s network of physicians and hospitals.3

Drug plans must cover at least 2 drugs in each therapeutic class approved by Medicare, but they may use tiered cost-sharing (eg, generics and brand-name drugs in different tiers) and other management tools as long as they meet the minimum requirements of the overall bill. The decision by the White House and Congress to approve the privatization of the drug benefit has led to the current situation in which multiple private plans are competing for enrollment in each geographic region and offering different drugs for different prices. For instance, in my county, there are 7 MA plans and 43 PDP plans being offered. This makes the system overly complex and confusing. In addition, the Medicare Modernization Act allows plans to increase the copays or even end coverage of specific drugs with 60 days notice.

Dual eligibles and low-income beneficiaries

The Medicare Modernization Act provided additional assistance to persons of limited means—those currently covered by Medicare and Medicaid plans who receive their medications through Medicaid (the dual-eligibles) and those who have limited income and resources but are only covered by Medicare. The former group will automatically be enrolled into PDPs if they do not sign up on their own, and they will pay reduced fees for their medications. The states, in turn, will reimburse the federal government for the drug cost savings gained by their Medicaid programs.

Other low-income individuals may also be eligible for drug benefit subsidies based on their income and assets (TABLE). Clearly, the Medicare Modernization Act offers significant drug benefits to beneficiaries of limited means. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projects that 10.9 million beneficiaries will receive low-income subsidies out of 14.5 million eligible.

TABLE

Medicare prescription drug benefit subsidies for low-income beneficiaries, 2006

| LOW-INCOME SUBSIDY LEVEL | PREMIUM | MONTHLY DEDUCTIBLE | ANNUAL COPAYMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-benefit dual eligibles Income <100% of poverty ($9750 individual; $12,830/couple) | $0 | $0 | $1/generic, $3/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Full-benefit dual eligibles Income ≥100% of poverty | $0 | $0 | $2/generic, $5/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Institutionalized full-benefit dual eligibles | $0 | $0 | No copays |

| Individuals with income <135% of poverty ($12,920 individuals, $17,321/couple) and assets <$6000/individual; $9000/couple | $0 | $0 | $2/generic, $5/brand-name; no copays after total drug spending reaches $5100 |

| Individuals with income 135%–150% of poverty ($12,920–$14,355 individuals, $17,321–$19,245/couple) and assets <$10,000/individual, $20,000/couple | Sliding scale up to $32.20* | $50 | 15% of total costs up to $5100; $2/generic, $5/brand-name thereafter |

| Note: Poverty-level dollar amounts are for 2005. Additional assests of up to $1500/individual and $3000/couple for funeral or burial expenses are permitted. *$32.20 is the national monthly Part D base beneficiary premium for 2006. | |||

| Source: Kaiser Family Foundation summary of Medicare prescription drug benefit low-income subsidies in 2006. | |||

Medigap and employer-sponsored plans

Many current beneficiaries have Medigap insurance policies, which cover part or all of the financial holes in the traditional Medicare plan—eg, deductibles, copays, and other benefits such as drug coverage. Beginning in January 2006, new policies that include drug coverage can no longer be issued. Policyholders can keep their current Medigap policies that cover medications; however, these are generally not considered equivalent to the new coverage. In addition, Medicare will provide subsidies to employers to encourage them to continue any current retiree plans that provide drug coverage comparable to the new plans.4

Enrollment

While the new drug plans start on January 1, 2006, the initial enrollment period runs until May 15, 2006. Beneficiaries who enroll after that time and do not currently have drug coverage as good as the new Medicare drug benefit will pay a higher premium equal to 1% of the average monthly premium for each month they delay enrollment. Those who enroll may change plans one time between December 31, 2005 and May 15, 2006. After May 15, the next enrollment period will be from November 15 to December 31, 2006. Any enrollee can change plans during that time.

In order to assist beneficiaries in making a decision about whether to enroll in a Medicare drug plan and which to choose, the federal government, assisted by a number of medical organizations (such as the AAFP) and nonprofits like the local Area Agencies on Aging, is providing seniors with information in a variety of formats. Beneficiaries should all have received a booklet, “Medicare and You,” in October 2005. There is a 24-hour telephone help line, 1-800-MEDICARE, that has automated answers and can provide access to a real person.

Finally, there is the Internet: www.medicare.gov. While 3 of 4 seniors have never been online, this is the best method to locate available plans in your area, find out which specific medications are included in each plan, and try to compare costs.5 For many seniors, it will be worth asking family members, friends, or community agencies for help in navigating the web site and the information it contains.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eric A. Henley, MD, MPH, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107-1897. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Kaiser Family Foundation news release. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/med111005nr.cfm. Accessed on November 21, 2005.

2. Henley E. What the new Medicare prescription drug bill may mean for providers and patients. J Fam Pract 2004;53:389-392.

3. Fuhrmans V, Lueck S. Insurers sweeten health plans for seniors. Wall Street Journal, November 8, 2005.

4. The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/7044-02.cfm. Accessed on December 4, 2005.

5. Glendinning D. Patients look to doctors for help on Medicare drug plans. AMA News, December 5, 2005.

1. Kaiser Family Foundation news release. Available at: www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/med111005nr.cfm. Accessed on November 21, 2005.

2. Henley E. What the new Medicare prescription drug bill may mean for providers and patients. J Fam Pract 2004;53:389-392.

3. Fuhrmans V, Lueck S. Insurers sweeten health plans for seniors. Wall Street Journal, November 8, 2005.

4. The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/7044-02.cfm. Accessed on December 4, 2005.

5. Glendinning D. Patients look to doctors for help on Medicare drug plans. AMA News, December 5, 2005.

Pandemic influenza: How it would progress and what it would require of you