User login

Meningococcal vaccine: New product, new recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends that all adolescents aged 11 to 12 years receive a quadrivalent, conjugate meningococcal vaccine (MCV-4). With time, universal administration of meningococcal vaccine for this age group will make moot the question of whether entering college freshmen should receive meningococcal vaccine. It should lead to a marked reduction in a potentially catastrophic disease and contribute to the continued decline in morbidity and mortality from bacterial meningitis in the United States, which has largely been due to advances in vaccine technology.

Some 1400 to 2800 cases of meningococcal infection occur in the US each year.1 The infection has a 10% to 14% fatality rate,1 and 11% to 19% of survivors are left with serious sequelae such as hearing loss, neurological problems, and mental deficits.

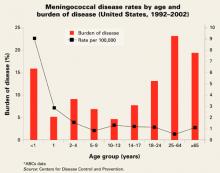

Risk of infection varies by age (FIGURE). At highest risk are those under 1 year, with rates of between 5–15/100,000.

Five serogroups of the bacteria are important causes of disease: A, B, C, Y, and W-135. In the US, most disease is caused by groups B, C, and Y; about a third by each.

FIGURE

Meningococcal disease rates by age and burden of disease (United States, 1992–2002)

New vaccine lasts longer

Fortunately, some meningococcal infections are vaccine-preventable. The new quadrivalent conjugate vaccine (Menactra) has been approved for persons aged 11–55 years. It offers protection against the same serogroups (A, C, Y, and W-135) as the older polysaccharide vaccine (Menomune). However, whereas immunity from the polysaccharide vaccine wanes after about 3 to 5 years, the newer vaccine is expected to provide much longer immunity (though experience with the conjugate product has not accumulated).

Who should receive the vaccine?

Until the cohort of current 11- to 12-year-olds being vaccinated reaches high school and college, the CDC recommends universal administration of the vaccine to those entering high school and to college freshmen living in dormitories. Those for whom the vaccine is recommended who have received the polysaccharide vaccine more than 3 years previously should be revaccinated with conjugate vaccine.

Meningococcal vaccine has also been recommended for those in high-risk groups: those with anatomical or functional asplenia, those with terminal complement component deficiency, laboratory and research personnel with potential exposure to meningococci, and travelers to areas with endemic meningococcal disease.2

Meningococcal vaccine is also used in the military and to control outbreaks, defined as 3 or more cases resulting in a case rate of 10/100,000 in a 3-month period. College freshmen who live in dormitories are at higher risk for meningococcal infection and the recommendation has been to discuss the risks and benefits of vaccine with those in this category.

Caveats

The new vaccine is contraindicated for those with allergy to latex since that substance is used in the vial stopper. Adverse reactions have been mild; redness, pain and swelling at the injection site, headache, and malaise. As with all new products, physicians should be alert for previously unreported adverse reactions and report suspected reactions to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (www.vaers.org/).

Unresolved issues

These new meningococcal vaccine recommendations leave several issues to be resolved with time.

Will there be enough vaccine? Since new vaccine recommendations for vaccination take time to become universal in actual practice, it is expected that the supply of the vaccine will keep up with demand.

What will be the fate of the old polysaccharide vaccine? The manufacturer intends for the new conjugate vaccine to replace the polysaccharide vaccine, especially if the license can be expanded to include other age groups. Until that occurs, the polysaccharide vaccine is the only product available for those at risk who are aged 2 to 10 years or aged more than 55 years.

Will a booster dose be needed? The full duration of protection from the new vaccine is not currently known but is expected to be at least 10 years. This will protect adolescents and young adults through the highest-risk periods. Whether a booster will eventually be recommended will depend on information gathered in the next several years.

Will the license for the new vaccine be extended to a larger age group? It is anticipated that with time the license for the conjugate vaccine will be expanded to include other age groups, particularly children under age 11.

What about children under age 2? There is currently no meningococcal vaccine proven effective for children in this age group. More than 50% of invasive meningococcal disease in this age group is caused by serogroup B. Neither meningococcal vaccine offers protection against this serogroup.

Chemoprophylaxis of contacts

The universal use of conjugate meningococcal vaccine should lead to a marked decrease in the number of meningococcal infections. However, physicians should keep in mind that close contacts of patients with meningococcal infections should be given one of the antibiotic regimens described in the TABLE within 24 hours of confirming the disease. Close contacts include household members, daycare center cohorts, and those directly exposed to the patients’ oral secretions through kissing, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and intubations.

Patients treated for meningococcemia with other than a third-generation cephalosporin should also be treated with one of the regimens in the TABLE since other antibiotics have not been shown to eradicate nasopharyngeal carriage.

An expected result of conjugate vaccine is to decrease the nasopharyngeal carriage of Neisseria meningitidis. It is unknown if close contacts who have been vaccinated will benefit from chemoprophylaxis.

TABLE

Schedule for administering chemoprophylaxis against meningococcal disease

| DRUG | AGE GROUP | DOSAGE | DURATION/ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampin† | Children <1 mo | 5 mg/kg every 12 h | 2 days |

| Children ≥1 mo | 10 mg/kg every 12 h | 2 days | |

| Adults | 600 mg every 12 h | 2 days | |

| Ciprofloxacin§ | Adults | 500 mg | Single dose |

| Ceftriaxone | Children <15 yrs | 125 mg | Single intramuscular dose |

| Ceftriaxone | Adults | 250 mg | Single intramuscular dose |

| *Oral administration unless indicated otherwise. †Rifampin is not recommended for pregnant women because the drug is teratogenic in laboratory animals. Because the reliability of oral contraceptives may be affected by rifampin therapy, consideration should be given to using alternative contraceptive measures while rifampin is being administered. §Ciprofloxacin is not generally recommended for persons aged <18 years or for pregnant and lactating women because the drug causes cartilage damage for immature laboratory animals. However, ciprofloxacin can be used for chemoprophylaxis of children when no acceptable alternative therapy is available. | |||

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of meningococcal disease. MMWR 2005; in press.

2. CDC. National Center for Infectious Diseases. Traveler’s Health web site. Health information for international travel: meningococcal disease. Available at: www.cdc.gov/travel/diseases/menin.htm. Map of African meningitis belt available at: www.cdc.gov/ travel/diseases/maps/menin_map.htm. Accessed on February 23, 2005.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends that all adolescents aged 11 to 12 years receive a quadrivalent, conjugate meningococcal vaccine (MCV-4). With time, universal administration of meningococcal vaccine for this age group will make moot the question of whether entering college freshmen should receive meningococcal vaccine. It should lead to a marked reduction in a potentially catastrophic disease and contribute to the continued decline in morbidity and mortality from bacterial meningitis in the United States, which has largely been due to advances in vaccine technology.

Some 1400 to 2800 cases of meningococcal infection occur in the US each year.1 The infection has a 10% to 14% fatality rate,1 and 11% to 19% of survivors are left with serious sequelae such as hearing loss, neurological problems, and mental deficits.

Risk of infection varies by age (FIGURE). At highest risk are those under 1 year, with rates of between 5–15/100,000.

Five serogroups of the bacteria are important causes of disease: A, B, C, Y, and W-135. In the US, most disease is caused by groups B, C, and Y; about a third by each.

FIGURE

Meningococcal disease rates by age and burden of disease (United States, 1992–2002)

New vaccine lasts longer

Fortunately, some meningococcal infections are vaccine-preventable. The new quadrivalent conjugate vaccine (Menactra) has been approved for persons aged 11–55 years. It offers protection against the same serogroups (A, C, Y, and W-135) as the older polysaccharide vaccine (Menomune). However, whereas immunity from the polysaccharide vaccine wanes after about 3 to 5 years, the newer vaccine is expected to provide much longer immunity (though experience with the conjugate product has not accumulated).

Who should receive the vaccine?

Until the cohort of current 11- to 12-year-olds being vaccinated reaches high school and college, the CDC recommends universal administration of the vaccine to those entering high school and to college freshmen living in dormitories. Those for whom the vaccine is recommended who have received the polysaccharide vaccine more than 3 years previously should be revaccinated with conjugate vaccine.

Meningococcal vaccine has also been recommended for those in high-risk groups: those with anatomical or functional asplenia, those with terminal complement component deficiency, laboratory and research personnel with potential exposure to meningococci, and travelers to areas with endemic meningococcal disease.2

Meningococcal vaccine is also used in the military and to control outbreaks, defined as 3 or more cases resulting in a case rate of 10/100,000 in a 3-month period. College freshmen who live in dormitories are at higher risk for meningococcal infection and the recommendation has been to discuss the risks and benefits of vaccine with those in this category.

Caveats

The new vaccine is contraindicated for those with allergy to latex since that substance is used in the vial stopper. Adverse reactions have been mild; redness, pain and swelling at the injection site, headache, and malaise. As with all new products, physicians should be alert for previously unreported adverse reactions and report suspected reactions to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (www.vaers.org/).

Unresolved issues

These new meningococcal vaccine recommendations leave several issues to be resolved with time.

Will there be enough vaccine? Since new vaccine recommendations for vaccination take time to become universal in actual practice, it is expected that the supply of the vaccine will keep up with demand.

What will be the fate of the old polysaccharide vaccine? The manufacturer intends for the new conjugate vaccine to replace the polysaccharide vaccine, especially if the license can be expanded to include other age groups. Until that occurs, the polysaccharide vaccine is the only product available for those at risk who are aged 2 to 10 years or aged more than 55 years.

Will a booster dose be needed? The full duration of protection from the new vaccine is not currently known but is expected to be at least 10 years. This will protect adolescents and young adults through the highest-risk periods. Whether a booster will eventually be recommended will depend on information gathered in the next several years.

Will the license for the new vaccine be extended to a larger age group? It is anticipated that with time the license for the conjugate vaccine will be expanded to include other age groups, particularly children under age 11.

What about children under age 2? There is currently no meningococcal vaccine proven effective for children in this age group. More than 50% of invasive meningococcal disease in this age group is caused by serogroup B. Neither meningococcal vaccine offers protection against this serogroup.

Chemoprophylaxis of contacts

The universal use of conjugate meningococcal vaccine should lead to a marked decrease in the number of meningococcal infections. However, physicians should keep in mind that close contacts of patients with meningococcal infections should be given one of the antibiotic regimens described in the TABLE within 24 hours of confirming the disease. Close contacts include household members, daycare center cohorts, and those directly exposed to the patients’ oral secretions through kissing, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and intubations.

Patients treated for meningococcemia with other than a third-generation cephalosporin should also be treated with one of the regimens in the TABLE since other antibiotics have not been shown to eradicate nasopharyngeal carriage.

An expected result of conjugate vaccine is to decrease the nasopharyngeal carriage of Neisseria meningitidis. It is unknown if close contacts who have been vaccinated will benefit from chemoprophylaxis.

TABLE

Schedule for administering chemoprophylaxis against meningococcal disease

| DRUG | AGE GROUP | DOSAGE | DURATION/ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampin† | Children <1 mo | 5 mg/kg every 12 h | 2 days |

| Children ≥1 mo | 10 mg/kg every 12 h | 2 days | |

| Adults | 600 mg every 12 h | 2 days | |

| Ciprofloxacin§ | Adults | 500 mg | Single dose |

| Ceftriaxone | Children <15 yrs | 125 mg | Single intramuscular dose |

| Ceftriaxone | Adults | 250 mg | Single intramuscular dose |

| *Oral administration unless indicated otherwise. †Rifampin is not recommended for pregnant women because the drug is teratogenic in laboratory animals. Because the reliability of oral contraceptives may be affected by rifampin therapy, consideration should be given to using alternative contraceptive measures while rifampin is being administered. §Ciprofloxacin is not generally recommended for persons aged <18 years or for pregnant and lactating women because the drug causes cartilage damage for immature laboratory animals. However, ciprofloxacin can be used for chemoprophylaxis of children when no acceptable alternative therapy is available. | |||

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends that all adolescents aged 11 to 12 years receive a quadrivalent, conjugate meningococcal vaccine (MCV-4). With time, universal administration of meningococcal vaccine for this age group will make moot the question of whether entering college freshmen should receive meningococcal vaccine. It should lead to a marked reduction in a potentially catastrophic disease and contribute to the continued decline in morbidity and mortality from bacterial meningitis in the United States, which has largely been due to advances in vaccine technology.

Some 1400 to 2800 cases of meningococcal infection occur in the US each year.1 The infection has a 10% to 14% fatality rate,1 and 11% to 19% of survivors are left with serious sequelae such as hearing loss, neurological problems, and mental deficits.

Risk of infection varies by age (FIGURE). At highest risk are those under 1 year, with rates of between 5–15/100,000.

Five serogroups of the bacteria are important causes of disease: A, B, C, Y, and W-135. In the US, most disease is caused by groups B, C, and Y; about a third by each.

FIGURE

Meningococcal disease rates by age and burden of disease (United States, 1992–2002)

New vaccine lasts longer

Fortunately, some meningococcal infections are vaccine-preventable. The new quadrivalent conjugate vaccine (Menactra) has been approved for persons aged 11–55 years. It offers protection against the same serogroups (A, C, Y, and W-135) as the older polysaccharide vaccine (Menomune). However, whereas immunity from the polysaccharide vaccine wanes after about 3 to 5 years, the newer vaccine is expected to provide much longer immunity (though experience with the conjugate product has not accumulated).

Who should receive the vaccine?

Until the cohort of current 11- to 12-year-olds being vaccinated reaches high school and college, the CDC recommends universal administration of the vaccine to those entering high school and to college freshmen living in dormitories. Those for whom the vaccine is recommended who have received the polysaccharide vaccine more than 3 years previously should be revaccinated with conjugate vaccine.

Meningococcal vaccine has also been recommended for those in high-risk groups: those with anatomical or functional asplenia, those with terminal complement component deficiency, laboratory and research personnel with potential exposure to meningococci, and travelers to areas with endemic meningococcal disease.2

Meningococcal vaccine is also used in the military and to control outbreaks, defined as 3 or more cases resulting in a case rate of 10/100,000 in a 3-month period. College freshmen who live in dormitories are at higher risk for meningococcal infection and the recommendation has been to discuss the risks and benefits of vaccine with those in this category.

Caveats

The new vaccine is contraindicated for those with allergy to latex since that substance is used in the vial stopper. Adverse reactions have been mild; redness, pain and swelling at the injection site, headache, and malaise. As with all new products, physicians should be alert for previously unreported adverse reactions and report suspected reactions to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (www.vaers.org/).

Unresolved issues

These new meningococcal vaccine recommendations leave several issues to be resolved with time.

Will there be enough vaccine? Since new vaccine recommendations for vaccination take time to become universal in actual practice, it is expected that the supply of the vaccine will keep up with demand.

What will be the fate of the old polysaccharide vaccine? The manufacturer intends for the new conjugate vaccine to replace the polysaccharide vaccine, especially if the license can be expanded to include other age groups. Until that occurs, the polysaccharide vaccine is the only product available for those at risk who are aged 2 to 10 years or aged more than 55 years.

Will a booster dose be needed? The full duration of protection from the new vaccine is not currently known but is expected to be at least 10 years. This will protect adolescents and young adults through the highest-risk periods. Whether a booster will eventually be recommended will depend on information gathered in the next several years.

Will the license for the new vaccine be extended to a larger age group? It is anticipated that with time the license for the conjugate vaccine will be expanded to include other age groups, particularly children under age 11.

What about children under age 2? There is currently no meningococcal vaccine proven effective for children in this age group. More than 50% of invasive meningococcal disease in this age group is caused by serogroup B. Neither meningococcal vaccine offers protection against this serogroup.

Chemoprophylaxis of contacts

The universal use of conjugate meningococcal vaccine should lead to a marked decrease in the number of meningococcal infections. However, physicians should keep in mind that close contacts of patients with meningococcal infections should be given one of the antibiotic regimens described in the TABLE within 24 hours of confirming the disease. Close contacts include household members, daycare center cohorts, and those directly exposed to the patients’ oral secretions through kissing, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and intubations.

Patients treated for meningococcemia with other than a third-generation cephalosporin should also be treated with one of the regimens in the TABLE since other antibiotics have not been shown to eradicate nasopharyngeal carriage.

An expected result of conjugate vaccine is to decrease the nasopharyngeal carriage of Neisseria meningitidis. It is unknown if close contacts who have been vaccinated will benefit from chemoprophylaxis.

TABLE

Schedule for administering chemoprophylaxis against meningococcal disease

| DRUG | AGE GROUP | DOSAGE | DURATION/ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampin† | Children <1 mo | 5 mg/kg every 12 h | 2 days |

| Children ≥1 mo | 10 mg/kg every 12 h | 2 days | |

| Adults | 600 mg every 12 h | 2 days | |

| Ciprofloxacin§ | Adults | 500 mg | Single dose |

| Ceftriaxone | Children <15 yrs | 125 mg | Single intramuscular dose |

| Ceftriaxone | Adults | 250 mg | Single intramuscular dose |

| *Oral administration unless indicated otherwise. †Rifampin is not recommended for pregnant women because the drug is teratogenic in laboratory animals. Because the reliability of oral contraceptives may be affected by rifampin therapy, consideration should be given to using alternative contraceptive measures while rifampin is being administered. §Ciprofloxacin is not generally recommended for persons aged <18 years or for pregnant and lactating women because the drug causes cartilage damage for immature laboratory animals. However, ciprofloxacin can be used for chemoprophylaxis of children when no acceptable alternative therapy is available. | |||

CORRESPONDENCE

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 4001 North Third Street #415, Phoenix, AZ 85012. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of meningococcal disease. MMWR 2005; in press.

2. CDC. National Center for Infectious Diseases. Traveler’s Health web site. Health information for international travel: meningococcal disease. Available at: www.cdc.gov/travel/diseases/menin.htm. Map of African meningitis belt available at: www.cdc.gov/ travel/diseases/maps/menin_map.htm. Accessed on February 23, 2005.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention and control of meningococcal disease. MMWR 2005; in press.

2. CDC. National Center for Infectious Diseases. Traveler’s Health web site. Health information for international travel: meningococcal disease. Available at: www.cdc.gov/travel/diseases/menin.htm. Map of African meningitis belt available at: www.cdc.gov/ travel/diseases/maps/menin_map.htm. Accessed on February 23, 2005.

Consumer-directed health care: One step forward, two steps back?

The way to manage rising health care costs—espoused by some analysts and the current administration—is to give consumers greater control over health care decisions through a concept termed consumer-directed health care (CDHC). Sounds good. But how would the likely implications really play out?

CDHC in a nutshell

Herzlinger, a CDHC proponent from the Harvard Business School, describes the concept’s key principles:

- Insurers and providers freely design and price their services to offer good value for the money.

- Consumers receive excellent information about the costs, quality, and scope of services, so they can make better health care purchasing decisions.

- Consumers buy health insurance plans, sometimes with employer funds, knowing their full costs so they can obtain good value for the money.1

In the US, CDHC combines a high-deductible health plan (HDHP) with a health savings account (HSA). In 2004, the consulting firm Mercer estimated that just 1% of all covered employees were in consumer-directed health plans, but 26% of all employers were likely to offer a CDHP within the next 2 years.

Recently, Humana introduced a health plan that could be combined with an HSA. UnitedHealth Group bought Definity Health, which specializes in HSAs. Blue Cross/Blue Shield announced it would offer HSA-compatible health plans nationwide by 2006, and Kaiser said it would do the same by 2005.2 The American Medical Association has made the provision of HSAs a key part of its health policy agenda.3

High-deductible health plans

An HDHP is a health insurance policy with a minimum deductible of $1050 for self or $2100 for family coverage. The minimum deductible amount will likely increase yearly. The policy’s annual out-of-pocket expenses, including deductibles and co-pays, cannot exceed $5000 for self or $10,000 for family coverage (Table 1).

The program may offer medical services through the variety of managed care options such as health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), or point of service plans with in-network and out-of-network providers. Persons using in-net-work options save money by receiving price discounts on services.

Companies may offer HDHPs with no deductible for preventive services (eg, physicals, immunizations, screening tests, prenatal and well child care) and higher deductibles and co-pays for using out-of-network providers.4

TABLE 1

Allowable limits on HDHP and HSA accounts

| High-deductible health plan (HDHP) | |

| Minimum deductible: | |

| Individual | $1050 |

| Family | $2100 |

| Maximum out-of-pocket spending | |

| Individual | $5000 |

| Family | $10,000 |

| Health savings account (HSA) | |

| Maximum annual contribution | |

| Whichever is lesser: the HDHP deductible, or | |

| Individual | $2600 |

| Family | $5150 |

Health savings account: how it works

An HSA is a tax-exempt personal savings account used to pay for qualified medical expenses. Think of it as an IRA for health. Legislation to establish HSAs was included in the Medicare Prescription Drug Bill of 2003.

To set up an HSA, a consumer must have an HDHP, have no other health insurance, and be ineligible for Medicare. Individuals can sign up on their own through insurance companies (including the American Medical Association insurance company) or banks, or may be offered an HSA option through their employer. Contributions to the account can be made by individuals, by an employer, or both. If made by the individual, contributions are tax exempt; if by the employer, they are not taxable as income to the employee.

The maximum deposit that can be made in 2005 is the lesser of either the HDHP deductible or $2650 for the individual or $5250 for family coverage. These amounts will be indexed to inflation yearly. Individuals aged 55 to 65 can make catch-up contributions. Once eligible for Medicare, you can no longer contribute to an HSA.4,5

Funds in an HSA are usually controlled by the individual who sets up the account. Withdrawals are tax-exempt if used for qualified medical expenses. If used for other expenses, withdrawals are taxed and subject to a tax penalty. Monies in an HSA can accrue tax-exempt savings from investments (stocks, bonds, etc) and be rolled over each year with no maximum cap. Since the individual owns the account, it is portable. If a person moves, the account moves too. However, contributions to an HSA must stop if the person is no longer enrolled in an HDHP.

After age 65, a person may continue to use an HSA for medical expenses or to pay insurance premiums like Medicare Part B and Medicare HMOs, or the funds can be taxed and used for non-medical expenses. In addition to the usual services covered in a traditional health plan, the list of qualified medical expenses is quite extensive (Table 2). Cosmetic surgery is generally not a qualified expense. The general goal is to have enough funds in the HSA to cover all medical expenses before the deductible in the health insurance plan is met.4,5

TABLE 2

Qualified CDHC medical coverage beyond traditional services

| Certain alternative medicine therapies |

| Substance abuse therapy |

| Ambulance service |

| Medical equipment and home remodeling related to medical requirements |

| Reproductive health services |

| Vision, hearing aides, and dental care |

| Certain health insurance premium costs |

| Long-term care |

| Medications and home oxygen |

| Mental health services |

| Source: Internal Revenue Service Publication 502. Available at: http://www.irs.gov/publications/p502/ar02.html#d0e516. Accessed on February 1, 2005. |

Public opinion generally unfavorable

A recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 73% of respondents with employer-sponsored insurance had an unfavorable view of a health plan that combined an HDHP with an HSA, and 78% said they would feel vulnerable to high medical bills with this type of coverage.6

Iimplications of cdhc

Advocates of CDHC believe the financial disincentives of co-pays and high deductibles will encourage consumers to reduce their use of marginal services and to seek lower-cost, higher quality providers. They cite early studies showing CDHC participants decreased their use of certain medical services while increasing their use of preventive services and maintaining a balance in their HSA from one year to the next.1

Opponents of CDHC emphasize research that shows patients who pay more of their health care bills consume less care, including essential care. The RAND study of the 1970s confirmed that greater cost-sharing by patients reduced the chance they would receive effective medical care. This was particularly so for low-income patients. A recent study showed that increased medication cost-sharing led patients to stop using important drugs like statins and ACE inhibitors.7

How accessible/usable are health data?

Herzlinger cites informed consumer choices as a strength of the CDHC concept. However, the amount of information on cost and quality of health care is limited, albeit growing. More worrisome perhaps, there is little evidence that most patients can use this kind of information to make good health care decisions.

Who would benefit, who would not?

Another concern is that HDHPs and HSAs will more likely appeal to healthier, well-off people who can take full advantage of the tax incentives and more readily fund their accounts. If a significant number of consumers in this group moves toward CDHC plans, it would leave more unhealthy people in the traditional insurance system. This, in turn, would lead insurers to increase premiums for those less healthy consumers, thus making their insurance more expensive and, ironically, increasing the numbers of uninsured. CDHC plans may also appeal to the uninsured and those who have difficulty paying the usual health insurance premiums. This group is likely to have more difficulty fully funding their HSAs and, consequently, they will need to pay more of their deductible costs out-of-pocket, which can create a disincentive to seek needed care.

In an alternative analysis of CDHC, Robinson sees HSA products representing an evolution from collective insurance in which those in good health help finance the care of unhealthy enrollees with high expenditures (traditional health insurance with its “use it or lose it” design) to one in which unspent balances are retained by healthy enrollees rather than diverted to pay for the care of others (an HSA account with its “use it or save it” design).

In this scenario, healthy (and often well-off) consumers are favored by low-premium, high-deductible products. The savings are also financially protected from chronically ill users who would pay more in deductibles and coinsurance. The negative consequence is further diminishment of the already fragile social pooling effect of the current health insurance system and the potential for increasing the plight of the uninsured and underinsured.8

While it is likely that CDHC will attract more participants, it remains to be seen whether the public will support the concept if reports start appearing of significant numbers of patients refusing recommended services when faced with high deductibles and large out-of-pocket costs. CDHC will likely look attractive to healthy and well-off consumers, but its ability to control costs and improve quality in our already stressed health care system is suspect.

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Herzlinger R, Parsa-Parsi R. Consumer-driven health care. JAMA 2004;292:1213-1220.

2. Vogt K. Doctors looking at details as interest in HSAs grows. American Medical News, December 20, 2004.

3. Health savings accounts at a glance American Medical Association web site. November 2004. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/363/hsabrochure.pdf. Accessed on February 1, 2005.

4. High deductible health plans with health savings accounts Office of Personnel Management web site. Available at: www.opm.gov/hsa/faq.asp. Accessed February 1, 2005.

5. US Department of the Treasury Health savings accounts. Available at: http://www.ustreas.gov/offices/public-affairs/hsa/. Accessed on February 1, 2005.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser health poll report, September/October 2004. Available at www.kff.org/healthpollreport/Oct_2004/13.cfm. Accessed February 1, 2005.

7. Davis K. Consumer-directed health care: Will it improve health system performance? Health Services Research 2004;39:1219-1233.

8. Robinson J. Reinvention of health insurance in the consumer era. JAMA 2004;291:1880-1886.

The way to manage rising health care costs—espoused by some analysts and the current administration—is to give consumers greater control over health care decisions through a concept termed consumer-directed health care (CDHC). Sounds good. But how would the likely implications really play out?

CDHC in a nutshell

Herzlinger, a CDHC proponent from the Harvard Business School, describes the concept’s key principles:

- Insurers and providers freely design and price their services to offer good value for the money.

- Consumers receive excellent information about the costs, quality, and scope of services, so they can make better health care purchasing decisions.

- Consumers buy health insurance plans, sometimes with employer funds, knowing their full costs so they can obtain good value for the money.1

In the US, CDHC combines a high-deductible health plan (HDHP) with a health savings account (HSA). In 2004, the consulting firm Mercer estimated that just 1% of all covered employees were in consumer-directed health plans, but 26% of all employers were likely to offer a CDHP within the next 2 years.

Recently, Humana introduced a health plan that could be combined with an HSA. UnitedHealth Group bought Definity Health, which specializes in HSAs. Blue Cross/Blue Shield announced it would offer HSA-compatible health plans nationwide by 2006, and Kaiser said it would do the same by 2005.2 The American Medical Association has made the provision of HSAs a key part of its health policy agenda.3

High-deductible health plans

An HDHP is a health insurance policy with a minimum deductible of $1050 for self or $2100 for family coverage. The minimum deductible amount will likely increase yearly. The policy’s annual out-of-pocket expenses, including deductibles and co-pays, cannot exceed $5000 for self or $10,000 for family coverage (Table 1).

The program may offer medical services through the variety of managed care options such as health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), or point of service plans with in-network and out-of-network providers. Persons using in-net-work options save money by receiving price discounts on services.

Companies may offer HDHPs with no deductible for preventive services (eg, physicals, immunizations, screening tests, prenatal and well child care) and higher deductibles and co-pays for using out-of-network providers.4

TABLE 1

Allowable limits on HDHP and HSA accounts

| High-deductible health plan (HDHP) | |

| Minimum deductible: | |

| Individual | $1050 |

| Family | $2100 |

| Maximum out-of-pocket spending | |

| Individual | $5000 |

| Family | $10,000 |

| Health savings account (HSA) | |

| Maximum annual contribution | |

| Whichever is lesser: the HDHP deductible, or | |

| Individual | $2600 |

| Family | $5150 |

Health savings account: how it works

An HSA is a tax-exempt personal savings account used to pay for qualified medical expenses. Think of it as an IRA for health. Legislation to establish HSAs was included in the Medicare Prescription Drug Bill of 2003.

To set up an HSA, a consumer must have an HDHP, have no other health insurance, and be ineligible for Medicare. Individuals can sign up on their own through insurance companies (including the American Medical Association insurance company) or banks, or may be offered an HSA option through their employer. Contributions to the account can be made by individuals, by an employer, or both. If made by the individual, contributions are tax exempt; if by the employer, they are not taxable as income to the employee.

The maximum deposit that can be made in 2005 is the lesser of either the HDHP deductible or $2650 for the individual or $5250 for family coverage. These amounts will be indexed to inflation yearly. Individuals aged 55 to 65 can make catch-up contributions. Once eligible for Medicare, you can no longer contribute to an HSA.4,5

Funds in an HSA are usually controlled by the individual who sets up the account. Withdrawals are tax-exempt if used for qualified medical expenses. If used for other expenses, withdrawals are taxed and subject to a tax penalty. Monies in an HSA can accrue tax-exempt savings from investments (stocks, bonds, etc) and be rolled over each year with no maximum cap. Since the individual owns the account, it is portable. If a person moves, the account moves too. However, contributions to an HSA must stop if the person is no longer enrolled in an HDHP.

After age 65, a person may continue to use an HSA for medical expenses or to pay insurance premiums like Medicare Part B and Medicare HMOs, or the funds can be taxed and used for non-medical expenses. In addition to the usual services covered in a traditional health plan, the list of qualified medical expenses is quite extensive (Table 2). Cosmetic surgery is generally not a qualified expense. The general goal is to have enough funds in the HSA to cover all medical expenses before the deductible in the health insurance plan is met.4,5

TABLE 2

Qualified CDHC medical coverage beyond traditional services

| Certain alternative medicine therapies |

| Substance abuse therapy |

| Ambulance service |

| Medical equipment and home remodeling related to medical requirements |

| Reproductive health services |

| Vision, hearing aides, and dental care |

| Certain health insurance premium costs |

| Long-term care |

| Medications and home oxygen |

| Mental health services |

| Source: Internal Revenue Service Publication 502. Available at: http://www.irs.gov/publications/p502/ar02.html#d0e516. Accessed on February 1, 2005. |

Public opinion generally unfavorable

A recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 73% of respondents with employer-sponsored insurance had an unfavorable view of a health plan that combined an HDHP with an HSA, and 78% said they would feel vulnerable to high medical bills with this type of coverage.6

Iimplications of cdhc

Advocates of CDHC believe the financial disincentives of co-pays and high deductibles will encourage consumers to reduce their use of marginal services and to seek lower-cost, higher quality providers. They cite early studies showing CDHC participants decreased their use of certain medical services while increasing their use of preventive services and maintaining a balance in their HSA from one year to the next.1

Opponents of CDHC emphasize research that shows patients who pay more of their health care bills consume less care, including essential care. The RAND study of the 1970s confirmed that greater cost-sharing by patients reduced the chance they would receive effective medical care. This was particularly so for low-income patients. A recent study showed that increased medication cost-sharing led patients to stop using important drugs like statins and ACE inhibitors.7

How accessible/usable are health data?

Herzlinger cites informed consumer choices as a strength of the CDHC concept. However, the amount of information on cost and quality of health care is limited, albeit growing. More worrisome perhaps, there is little evidence that most patients can use this kind of information to make good health care decisions.

Who would benefit, who would not?

Another concern is that HDHPs and HSAs will more likely appeal to healthier, well-off people who can take full advantage of the tax incentives and more readily fund their accounts. If a significant number of consumers in this group moves toward CDHC plans, it would leave more unhealthy people in the traditional insurance system. This, in turn, would lead insurers to increase premiums for those less healthy consumers, thus making their insurance more expensive and, ironically, increasing the numbers of uninsured. CDHC plans may also appeal to the uninsured and those who have difficulty paying the usual health insurance premiums. This group is likely to have more difficulty fully funding their HSAs and, consequently, they will need to pay more of their deductible costs out-of-pocket, which can create a disincentive to seek needed care.

In an alternative analysis of CDHC, Robinson sees HSA products representing an evolution from collective insurance in which those in good health help finance the care of unhealthy enrollees with high expenditures (traditional health insurance with its “use it or lose it” design) to one in which unspent balances are retained by healthy enrollees rather than diverted to pay for the care of others (an HSA account with its “use it or save it” design).

In this scenario, healthy (and often well-off) consumers are favored by low-premium, high-deductible products. The savings are also financially protected from chronically ill users who would pay more in deductibles and coinsurance. The negative consequence is further diminishment of the already fragile social pooling effect of the current health insurance system and the potential for increasing the plight of the uninsured and underinsured.8

While it is likely that CDHC will attract more participants, it remains to be seen whether the public will support the concept if reports start appearing of significant numbers of patients refusing recommended services when faced with high deductibles and large out-of-pocket costs. CDHC will likely look attractive to healthy and well-off consumers, but its ability to control costs and improve quality in our already stressed health care system is suspect.

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

The way to manage rising health care costs—espoused by some analysts and the current administration—is to give consumers greater control over health care decisions through a concept termed consumer-directed health care (CDHC). Sounds good. But how would the likely implications really play out?

CDHC in a nutshell

Herzlinger, a CDHC proponent from the Harvard Business School, describes the concept’s key principles:

- Insurers and providers freely design and price their services to offer good value for the money.

- Consumers receive excellent information about the costs, quality, and scope of services, so they can make better health care purchasing decisions.

- Consumers buy health insurance plans, sometimes with employer funds, knowing their full costs so they can obtain good value for the money.1

In the US, CDHC combines a high-deductible health plan (HDHP) with a health savings account (HSA). In 2004, the consulting firm Mercer estimated that just 1% of all covered employees were in consumer-directed health plans, but 26% of all employers were likely to offer a CDHP within the next 2 years.

Recently, Humana introduced a health plan that could be combined with an HSA. UnitedHealth Group bought Definity Health, which specializes in HSAs. Blue Cross/Blue Shield announced it would offer HSA-compatible health plans nationwide by 2006, and Kaiser said it would do the same by 2005.2 The American Medical Association has made the provision of HSAs a key part of its health policy agenda.3

High-deductible health plans

An HDHP is a health insurance policy with a minimum deductible of $1050 for self or $2100 for family coverage. The minimum deductible amount will likely increase yearly. The policy’s annual out-of-pocket expenses, including deductibles and co-pays, cannot exceed $5000 for self or $10,000 for family coverage (Table 1).

The program may offer medical services through the variety of managed care options such as health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), or point of service plans with in-network and out-of-network providers. Persons using in-net-work options save money by receiving price discounts on services.

Companies may offer HDHPs with no deductible for preventive services (eg, physicals, immunizations, screening tests, prenatal and well child care) and higher deductibles and co-pays for using out-of-network providers.4

TABLE 1

Allowable limits on HDHP and HSA accounts

| High-deductible health plan (HDHP) | |

| Minimum deductible: | |

| Individual | $1050 |

| Family | $2100 |

| Maximum out-of-pocket spending | |

| Individual | $5000 |

| Family | $10,000 |

| Health savings account (HSA) | |

| Maximum annual contribution | |

| Whichever is lesser: the HDHP deductible, or | |

| Individual | $2600 |

| Family | $5150 |

Health savings account: how it works

An HSA is a tax-exempt personal savings account used to pay for qualified medical expenses. Think of it as an IRA for health. Legislation to establish HSAs was included in the Medicare Prescription Drug Bill of 2003.

To set up an HSA, a consumer must have an HDHP, have no other health insurance, and be ineligible for Medicare. Individuals can sign up on their own through insurance companies (including the American Medical Association insurance company) or banks, or may be offered an HSA option through their employer. Contributions to the account can be made by individuals, by an employer, or both. If made by the individual, contributions are tax exempt; if by the employer, they are not taxable as income to the employee.

The maximum deposit that can be made in 2005 is the lesser of either the HDHP deductible or $2650 for the individual or $5250 for family coverage. These amounts will be indexed to inflation yearly. Individuals aged 55 to 65 can make catch-up contributions. Once eligible for Medicare, you can no longer contribute to an HSA.4,5

Funds in an HSA are usually controlled by the individual who sets up the account. Withdrawals are tax-exempt if used for qualified medical expenses. If used for other expenses, withdrawals are taxed and subject to a tax penalty. Monies in an HSA can accrue tax-exempt savings from investments (stocks, bonds, etc) and be rolled over each year with no maximum cap. Since the individual owns the account, it is portable. If a person moves, the account moves too. However, contributions to an HSA must stop if the person is no longer enrolled in an HDHP.

After age 65, a person may continue to use an HSA for medical expenses or to pay insurance premiums like Medicare Part B and Medicare HMOs, or the funds can be taxed and used for non-medical expenses. In addition to the usual services covered in a traditional health plan, the list of qualified medical expenses is quite extensive (Table 2). Cosmetic surgery is generally not a qualified expense. The general goal is to have enough funds in the HSA to cover all medical expenses before the deductible in the health insurance plan is met.4,5

TABLE 2

Qualified CDHC medical coverage beyond traditional services

| Certain alternative medicine therapies |

| Substance abuse therapy |

| Ambulance service |

| Medical equipment and home remodeling related to medical requirements |

| Reproductive health services |

| Vision, hearing aides, and dental care |

| Certain health insurance premium costs |

| Long-term care |

| Medications and home oxygen |

| Mental health services |

| Source: Internal Revenue Service Publication 502. Available at: http://www.irs.gov/publications/p502/ar02.html#d0e516. Accessed on February 1, 2005. |

Public opinion generally unfavorable

A recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 73% of respondents with employer-sponsored insurance had an unfavorable view of a health plan that combined an HDHP with an HSA, and 78% said they would feel vulnerable to high medical bills with this type of coverage.6

Iimplications of cdhc

Advocates of CDHC believe the financial disincentives of co-pays and high deductibles will encourage consumers to reduce their use of marginal services and to seek lower-cost, higher quality providers. They cite early studies showing CDHC participants decreased their use of certain medical services while increasing their use of preventive services and maintaining a balance in their HSA from one year to the next.1

Opponents of CDHC emphasize research that shows patients who pay more of their health care bills consume less care, including essential care. The RAND study of the 1970s confirmed that greater cost-sharing by patients reduced the chance they would receive effective medical care. This was particularly so for low-income patients. A recent study showed that increased medication cost-sharing led patients to stop using important drugs like statins and ACE inhibitors.7

How accessible/usable are health data?

Herzlinger cites informed consumer choices as a strength of the CDHC concept. However, the amount of information on cost and quality of health care is limited, albeit growing. More worrisome perhaps, there is little evidence that most patients can use this kind of information to make good health care decisions.

Who would benefit, who would not?

Another concern is that HDHPs and HSAs will more likely appeal to healthier, well-off people who can take full advantage of the tax incentives and more readily fund their accounts. If a significant number of consumers in this group moves toward CDHC plans, it would leave more unhealthy people in the traditional insurance system. This, in turn, would lead insurers to increase premiums for those less healthy consumers, thus making their insurance more expensive and, ironically, increasing the numbers of uninsured. CDHC plans may also appeal to the uninsured and those who have difficulty paying the usual health insurance premiums. This group is likely to have more difficulty fully funding their HSAs and, consequently, they will need to pay more of their deductible costs out-of-pocket, which can create a disincentive to seek needed care.

In an alternative analysis of CDHC, Robinson sees HSA products representing an evolution from collective insurance in which those in good health help finance the care of unhealthy enrollees with high expenditures (traditional health insurance with its “use it or lose it” design) to one in which unspent balances are retained by healthy enrollees rather than diverted to pay for the care of others (an HSA account with its “use it or save it” design).

In this scenario, healthy (and often well-off) consumers are favored by low-premium, high-deductible products. The savings are also financially protected from chronically ill users who would pay more in deductibles and coinsurance. The negative consequence is further diminishment of the already fragile social pooling effect of the current health insurance system and the potential for increasing the plight of the uninsured and underinsured.8

While it is likely that CDHC will attract more participants, it remains to be seen whether the public will support the concept if reports start appearing of significant numbers of patients refusing recommended services when faced with high deductibles and large out-of-pocket costs. CDHC will likely look attractive to healthy and well-off consumers, but its ability to control costs and improve quality in our already stressed health care system is suspect.

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Herzlinger R, Parsa-Parsi R. Consumer-driven health care. JAMA 2004;292:1213-1220.

2. Vogt K. Doctors looking at details as interest in HSAs grows. American Medical News, December 20, 2004.

3. Health savings accounts at a glance American Medical Association web site. November 2004. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/363/hsabrochure.pdf. Accessed on February 1, 2005.

4. High deductible health plans with health savings accounts Office of Personnel Management web site. Available at: www.opm.gov/hsa/faq.asp. Accessed February 1, 2005.

5. US Department of the Treasury Health savings accounts. Available at: http://www.ustreas.gov/offices/public-affairs/hsa/. Accessed on February 1, 2005.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser health poll report, September/October 2004. Available at www.kff.org/healthpollreport/Oct_2004/13.cfm. Accessed February 1, 2005.

7. Davis K. Consumer-directed health care: Will it improve health system performance? Health Services Research 2004;39:1219-1233.

8. Robinson J. Reinvention of health insurance in the consumer era. JAMA 2004;291:1880-1886.

1. Herzlinger R, Parsa-Parsi R. Consumer-driven health care. JAMA 2004;292:1213-1220.

2. Vogt K. Doctors looking at details as interest in HSAs grows. American Medical News, December 20, 2004.

3. Health savings accounts at a glance American Medical Association web site. November 2004. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/363/hsabrochure.pdf. Accessed on February 1, 2005.

4. High deductible health plans with health savings accounts Office of Personnel Management web site. Available at: www.opm.gov/hsa/faq.asp. Accessed February 1, 2005.

5. US Department of the Treasury Health savings accounts. Available at: http://www.ustreas.gov/offices/public-affairs/hsa/. Accessed on February 1, 2005.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser health poll report, September/October 2004. Available at www.kff.org/healthpollreport/Oct_2004/13.cfm. Accessed February 1, 2005.

7. Davis K. Consumer-directed health care: Will it improve health system performance? Health Services Research 2004;39:1219-1233.

8. Robinson J. Reinvention of health insurance in the consumer era. JAMA 2004;291:1880-1886.

Cause-of-death certification: Not as easy as it seems

Think you know how to fill out a death certificate? It’s often not as easy as it seems. Try the following cases.

Case 1

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the ICU because of acute chest pain. She has a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and angina. Over the next 24 hours an acute myocardial infarction is confirmed. Heart failure develops but improves with medical management. The patient then experiences a pulmonary embolus, confirmed by ventilation-perfusion lung scan and blood gases; over the next 2 hours she becomes unresponsive and dies.

Question: What should be written on the death certificate as the immediate and underlying cause of death? Answer: pulmonary embolus due to acute myocardial infarction due to atherosclerotic heart disease.

Question: What should be listed as conditions contributing to death but not directly causing death? Answer: type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and congestive heart failure.

Case 2

A 78-year-old woman has left hemiparesis from a stroke 2 years earlier. She has been unable to care for herself and has lived in a nursing home. She has had an indwelling urinary catheter for the past 6 months. Because of fever, increased leukocyte count, and pyuria, she is admitted to the hospital and started on 2 antibiotics. Two days later, the blood culture result is positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to the antibiotics being administered. Despite a change of antibiotics, hypotension ensues and the patient dies on hospital day 4.

Question: What should be written on the death certificate as the immediate and underlying cause of death? Answer: P aeruginosa sepsis, due to a urinary tract infection due to an indwelling catheter, due to left hemiparesis, due to an old cerebral infarction.

Question: What should be listed as conditions that contributed to the death but that did not directly cause the death? Answer: nothing.

If you were correct on both cases, congratulations. If you were not, this article offers basic advice that will help you provide accurate medical information on death certificates.

Death certificates are important official records used for personal, legal, and public health purposes, yet they are frequently filled out inaccurately. Physicians are responsible for determining the cause and manner of death, yet they are seldom formally trained for this responsibility in medical school or residency. The result is frequent and avoidable errors.

Who is responsible for what?

Registration of deaths is a state responsibility. The National Center for Health Statistics compiles data from all states to produce national vital statistics, and most states use death certificate forms that conform to a recommended national standard. Though funeral directors are responsible for filing the certificate with the state, physicians are responsible for completing the medical portion of the certificate.

With the medical information provided, trained coders classify the cause of death using standardized methodology.

Medical examiners or coroners are responsible for investigating and certifying the cause of any death that is unexpected, unexplained, or resulting from injury, poisoning, or a public health threat.

Physicians are additionally responsible for answering inquiries from the registrar (these inquiries can be reduced by accurately and completely filling in the medical information) and submitting a supplemental report when autopsy findings or other information indicates a cause of death different from that originally reported.

How to complete the medical portion of the death certificate

The Figure is a standard certificate of death. It may vary slightly state to state. Physicians are responsible for items 24 through 49. If the state requires a pronouncing physician (Table 1), the pronouncing and certifying physicians may be different, in which case the pronouncing physician completes items 24 through 31 and the certifying physician items 32 through 49. If the pronouncing physician is also the certifying physician, items 26 through 28 need not be completed. If the death is referred to the coroner or medical examiner, they complete items 24, 25, 29, 30, and 32 through 49.

FIGURE

US standard death certificate

TABLE 1

Definitions

| Immediate cause of death:The final disease or injury causing the death. |

| Intermediate cause of death: A disease or condition that preceded and caused the immediate cause of death. |

| Underlying cause of death: A disease or condition present before, and leading to, the intermediate or immediate cause of death. It can be present for years before the death. |

| Manner of death: The circumstances leading to death—accident, homicide, suicide, unknown or undetermined, and natural causes. |

| Medical examiner: A physician, acting in an official capacity within a particular jurisdiction, charged with the investigation and examination of persons dying suddenly, unexpectedly, or violently, or whose death resulted from, or presents, a potential public health hazard. The medical examiner is not always required to be a specialist in death investigation or pathology. Most systems employing physicians as part time medical examiners encourage them to obtain training for medical examiners such as that offered by the National Association of Medical Examiners. |

| Coroner: A coroner is a public official, appointed or elected, in a particular geographic jurisdiction, whose official duty is to make inquiry into deaths in certain categories. In some jurisdictions, the coroner is a physician, but in many localities, the coroner is not required to be a physician nor be trained in medicine. |

| Pronouncing physician: The one who determines the decedent is legally dead. Not all states require a death to be pronounced by a physician. |

| Certifying physician: The one who certifies the cause of death. |

The most challenging part

Item 32, the Cause of Death, is the most difficult item to complete accurately. It consists of two parts. Part I is a sequential list of conditions leading to the immediate cause of death and the time interval between their onset and the death. Part II is a list of other conditions contributing to the death but not directly causing death. Thinking about the death as a sequence of events and reconstructing this sequence helps classify correctly the various illnesses and conditions the decedent might have had.

Immediate cause of death. Part I, line a, is for the immediate cause of death (see Table 1). This should be a disease, complication, or injury that directly caused the death. A common error is to list a mechanism of death (for example, cardiac arrest) rather than a disease (myocardial infarction).

Specific terms are better than vague ones. For instance,“cerebral infarction” is better than “stroke.” “Escherichia coli sepsis” is better than just “sepsis.”

When cancer is the cause of death, list the primary site, cell type, cancer grade, and specific organ or lobe affected.

Avoid terms without medical meaning, such as old age or senescence.

If additional information is expected from an autopsy, it is acceptable to list the cause of death as pending. But an update to certificate will be required once the additional information is obtained. It is also acceptable to list a cause as unknown. This will not automatically forward the case to the medical examiner.

Intermediate/underlying causes. Lines b, c, and d are for intermediate and underlying causes. Each condition listed should cause the one above it. You should be able to proceed logically from the underlying cause through each intermediate cause by saying the phrase “due to” or “as a consequence of,” moving from the lower line up through line b. There may be several intermediate causes. For example, a death may be due to a pulmonary embolus, as a consequence of hip surgery, resulting from a injury from a fall, resulting from a cerebral infarction. The underlying cause is the cerebral infarction.

Marking time intervals. To the right of lines a through d is space to write the time interval between the condition listed (immediate, intermediate, or underlying cause of death) and the time of death. The more precise the time the better. But it is understood that times must occasionally be estimated, and terms such as “approximately” are acceptable. If the time cannot be estimated, insert the phrase “unknown duration.” Something should be listed on this line next to the immediate, intermediate, and underlying conditions listed. No lines should be left blank.

Other illnesses. Part II is where to list other significant illnesses or conditions that may have contributed to the death but were not the direct causes of it. More than one condition may be listed. Many patients have multiple conditions and there may be uncertainty as to direct and contributing causes of the death. The physician is only expected to make the best judgment possible as to the most likely causes and sequences. Coders referring to international standards and rules will use the information to make a final classification of the underlying cause.

Specific errors to avoid

Table 2 includes some points to remember to avoid making errors when filling out the death certificate medical information. By following these rules, studying the cases provided in the Physicians’ Handbook on Medical Certification and Death, and systematically thinking about the sequence of events that caused the death, physicians can improve on their accuracy when performing the important and under appreciated role of accurately certifying the medical cause of death.

TABLE 2

Important points to remember when completing medical information on a death certificate

| Do not use abbreviations. |

| Do not use numbers for months; spell out the month. |

| Use a 24-hour clock (1600, not 4 P.M.). |

| Do not alter the document or erase any part of it. |

| Print legibly using black ink. |

| Complete all required items, do not leave them blank. If necessary, write “unknown.” |

| Do not delay completing the certification. The burial or other disposition of the remains depends on the correct completion of the certificate and its acceptance by the state or local registrar. |

| Do not complete the medical information if another physician has more knowledge of the circumstances, unless they are unavailable. |

Useful resources

The Physicians’ Handbook on Medical Certification of Death, published by the Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, is available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/hb_cod.pdf. It contains instructions on how to complete a death certificate and a series of useful examples that take about a half hour to review.

Correspondence

12229 S. Chinook, Phoenix, AZ 85044. E-mail: [email protected].

Think you know how to fill out a death certificate? It’s often not as easy as it seems. Try the following cases.

Case 1

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the ICU because of acute chest pain. She has a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and angina. Over the next 24 hours an acute myocardial infarction is confirmed. Heart failure develops but improves with medical management. The patient then experiences a pulmonary embolus, confirmed by ventilation-perfusion lung scan and blood gases; over the next 2 hours she becomes unresponsive and dies.

Question: What should be written on the death certificate as the immediate and underlying cause of death? Answer: pulmonary embolus due to acute myocardial infarction due to atherosclerotic heart disease.

Question: What should be listed as conditions contributing to death but not directly causing death? Answer: type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and congestive heart failure.

Case 2

A 78-year-old woman has left hemiparesis from a stroke 2 years earlier. She has been unable to care for herself and has lived in a nursing home. She has had an indwelling urinary catheter for the past 6 months. Because of fever, increased leukocyte count, and pyuria, she is admitted to the hospital and started on 2 antibiotics. Two days later, the blood culture result is positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to the antibiotics being administered. Despite a change of antibiotics, hypotension ensues and the patient dies on hospital day 4.

Question: What should be written on the death certificate as the immediate and underlying cause of death? Answer: P aeruginosa sepsis, due to a urinary tract infection due to an indwelling catheter, due to left hemiparesis, due to an old cerebral infarction.

Question: What should be listed as conditions that contributed to the death but that did not directly cause the death? Answer: nothing.

If you were correct on both cases, congratulations. If you were not, this article offers basic advice that will help you provide accurate medical information on death certificates.

Death certificates are important official records used for personal, legal, and public health purposes, yet they are frequently filled out inaccurately. Physicians are responsible for determining the cause and manner of death, yet they are seldom formally trained for this responsibility in medical school or residency. The result is frequent and avoidable errors.

Who is responsible for what?

Registration of deaths is a state responsibility. The National Center for Health Statistics compiles data from all states to produce national vital statistics, and most states use death certificate forms that conform to a recommended national standard. Though funeral directors are responsible for filing the certificate with the state, physicians are responsible for completing the medical portion of the certificate.

With the medical information provided, trained coders classify the cause of death using standardized methodology.

Medical examiners or coroners are responsible for investigating and certifying the cause of any death that is unexpected, unexplained, or resulting from injury, poisoning, or a public health threat.

Physicians are additionally responsible for answering inquiries from the registrar (these inquiries can be reduced by accurately and completely filling in the medical information) and submitting a supplemental report when autopsy findings or other information indicates a cause of death different from that originally reported.

How to complete the medical portion of the death certificate

The Figure is a standard certificate of death. It may vary slightly state to state. Physicians are responsible for items 24 through 49. If the state requires a pronouncing physician (Table 1), the pronouncing and certifying physicians may be different, in which case the pronouncing physician completes items 24 through 31 and the certifying physician items 32 through 49. If the pronouncing physician is also the certifying physician, items 26 through 28 need not be completed. If the death is referred to the coroner or medical examiner, they complete items 24, 25, 29, 30, and 32 through 49.

FIGURE

US standard death certificate

TABLE 1

Definitions

| Immediate cause of death:The final disease or injury causing the death. |

| Intermediate cause of death: A disease or condition that preceded and caused the immediate cause of death. |

| Underlying cause of death: A disease or condition present before, and leading to, the intermediate or immediate cause of death. It can be present for years before the death. |

| Manner of death: The circumstances leading to death—accident, homicide, suicide, unknown or undetermined, and natural causes. |

| Medical examiner: A physician, acting in an official capacity within a particular jurisdiction, charged with the investigation and examination of persons dying suddenly, unexpectedly, or violently, or whose death resulted from, or presents, a potential public health hazard. The medical examiner is not always required to be a specialist in death investigation or pathology. Most systems employing physicians as part time medical examiners encourage them to obtain training for medical examiners such as that offered by the National Association of Medical Examiners. |

| Coroner: A coroner is a public official, appointed or elected, in a particular geographic jurisdiction, whose official duty is to make inquiry into deaths in certain categories. In some jurisdictions, the coroner is a physician, but in many localities, the coroner is not required to be a physician nor be trained in medicine. |

| Pronouncing physician: The one who determines the decedent is legally dead. Not all states require a death to be pronounced by a physician. |

| Certifying physician: The one who certifies the cause of death. |

The most challenging part

Item 32, the Cause of Death, is the most difficult item to complete accurately. It consists of two parts. Part I is a sequential list of conditions leading to the immediate cause of death and the time interval between their onset and the death. Part II is a list of other conditions contributing to the death but not directly causing death. Thinking about the death as a sequence of events and reconstructing this sequence helps classify correctly the various illnesses and conditions the decedent might have had.

Immediate cause of death. Part I, line a, is for the immediate cause of death (see Table 1). This should be a disease, complication, or injury that directly caused the death. A common error is to list a mechanism of death (for example, cardiac arrest) rather than a disease (myocardial infarction).

Specific terms are better than vague ones. For instance,“cerebral infarction” is better than “stroke.” “Escherichia coli sepsis” is better than just “sepsis.”

When cancer is the cause of death, list the primary site, cell type, cancer grade, and specific organ or lobe affected.

Avoid terms without medical meaning, such as old age or senescence.

If additional information is expected from an autopsy, it is acceptable to list the cause of death as pending. But an update to certificate will be required once the additional information is obtained. It is also acceptable to list a cause as unknown. This will not automatically forward the case to the medical examiner.

Intermediate/underlying causes. Lines b, c, and d are for intermediate and underlying causes. Each condition listed should cause the one above it. You should be able to proceed logically from the underlying cause through each intermediate cause by saying the phrase “due to” or “as a consequence of,” moving from the lower line up through line b. There may be several intermediate causes. For example, a death may be due to a pulmonary embolus, as a consequence of hip surgery, resulting from a injury from a fall, resulting from a cerebral infarction. The underlying cause is the cerebral infarction.

Marking time intervals. To the right of lines a through d is space to write the time interval between the condition listed (immediate, intermediate, or underlying cause of death) and the time of death. The more precise the time the better. But it is understood that times must occasionally be estimated, and terms such as “approximately” are acceptable. If the time cannot be estimated, insert the phrase “unknown duration.” Something should be listed on this line next to the immediate, intermediate, and underlying conditions listed. No lines should be left blank.

Other illnesses. Part II is where to list other significant illnesses or conditions that may have contributed to the death but were not the direct causes of it. More than one condition may be listed. Many patients have multiple conditions and there may be uncertainty as to direct and contributing causes of the death. The physician is only expected to make the best judgment possible as to the most likely causes and sequences. Coders referring to international standards and rules will use the information to make a final classification of the underlying cause.

Specific errors to avoid

Table 2 includes some points to remember to avoid making errors when filling out the death certificate medical information. By following these rules, studying the cases provided in the Physicians’ Handbook on Medical Certification and Death, and systematically thinking about the sequence of events that caused the death, physicians can improve on their accuracy when performing the important and under appreciated role of accurately certifying the medical cause of death.

TABLE 2

Important points to remember when completing medical information on a death certificate

| Do not use abbreviations. |

| Do not use numbers for months; spell out the month. |

| Use a 24-hour clock (1600, not 4 P.M.). |

| Do not alter the document or erase any part of it. |

| Print legibly using black ink. |

| Complete all required items, do not leave them blank. If necessary, write “unknown.” |

| Do not delay completing the certification. The burial or other disposition of the remains depends on the correct completion of the certificate and its acceptance by the state or local registrar. |

| Do not complete the medical information if another physician has more knowledge of the circumstances, unless they are unavailable. |

Useful resources

The Physicians’ Handbook on Medical Certification of Death, published by the Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, is available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/hb_cod.pdf. It contains instructions on how to complete a death certificate and a series of useful examples that take about a half hour to review.

Correspondence

12229 S. Chinook, Phoenix, AZ 85044. E-mail: [email protected].

Think you know how to fill out a death certificate? It’s often not as easy as it seems. Try the following cases.

Case 1

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the ICU because of acute chest pain. She has a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and angina. Over the next 24 hours an acute myocardial infarction is confirmed. Heart failure develops but improves with medical management. The patient then experiences a pulmonary embolus, confirmed by ventilation-perfusion lung scan and blood gases; over the next 2 hours she becomes unresponsive and dies.

Question: What should be written on the death certificate as the immediate and underlying cause of death? Answer: pulmonary embolus due to acute myocardial infarction due to atherosclerotic heart disease.

Question: What should be listed as conditions contributing to death but not directly causing death? Answer: type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and congestive heart failure.

Case 2