User login

At what age should you start screening young people for anxiety?

On April 12, 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published a draft recommendation on screening for anxiety in children and adolescents. The recommendation states that clinicians should screen for anxiety in those ages 8 to 18 years. This is a “B” recommendation, which means there is moderate certainty that screening for anxiety in these individuals has a moderate net benefit. The USPSTF felt that the evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against screening at ages 7 years and younger.1

Anxiety is common among young people in America. A survey conducted in 2018-2019 found that 7.8% of children and adolescents (ages 3 to 17 years) had a current anxiety disorder.2 The isolation created by the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with increased rates of clinically significant psychiatric symptoms; one study suggested that in the first year of the pandemic, 20% of young people experienced elevated anxiety symptoms.3,4 Anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence also are associated with an increased likelihood of a future anxiety disorder, or depression, in adulthood.

Therapy may improve outcomes. There is evidence that treatment of anxiety disorders can result in improved clinical outcomes. Treatment options include psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both.5

However, studies showing benefit were conducted in young people whose anxiety was identified via signs or symptoms. The USPSTF could find no direct evidence that identifying anxiety in asymptomatic youth leads to better outcomes. The current draft recommendation is based on indirect evidence on the accuracy of the screening tools and the results of therapy in those who are symptomatic.

Speaking of screening tools ... There were 3 listed in the USPSTF evidence review: the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED), which assesses for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and any anxiety disorder6; the Patient Health Questionnaire-Adolescent, which screens for GAD and panic disorder7; and the Social Phobia Inventory.8 The SCARED and Social Phobia Inventory are the most widely used clinically.

The accuracy of the screening tests differed. For detection of GAD, sensitivity ranged from 50% to 88% and specificity from 63% to 98%; for social anxiety disorder, sensitivity ranged from 67% to 93% and specificity from 69% to 94%. False-positive results ranged from 17 to 361 per 1000 for GAD and from 104 to 254 per 1000 for social anxiety disorder.1

The USPSTF emphasized that anxiety should not be diagnosed based on a screening test alone. A positive screen should prompt further assessment and confirmation.

An unexpected rating. Given the opportunity costs to administer a screening tool, the high false-positive rates, and the lack of evidence that screening results in improved outcomes among asymptomatic youth, it is curious that this topic did not result in an “I” recommendation. Many screening interventions for children and adolescents with similar evidence profiles—including screening for suicide risk, drug abuse, eating disorders, and alcohol abuse—have previously received an “I.”9

Keep in mind that this is currently a draft recommendation that is open for public comment. The final recommendation will be published in 4 to 12 months.

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents. Draft recommendation statement. Published April 12, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

2. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed May 23, 2022. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

3. Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38:233-246. doi: 10.1002/da.23120

4. Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, et al. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1142-1150. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

5. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatr. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

6. Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, et al. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1230-1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011

7. Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:196-204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0

8. Antony MM, Coons MJ, McCabe RE, et al. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory: further evaluation. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1177-1185. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.013

9. USPSTF. Published recommendations: mental health conditions. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/topic_search_results?topic_status=P&searchterm=mental+health+conditions

On April 12, 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published a draft recommendation on screening for anxiety in children and adolescents. The recommendation states that clinicians should screen for anxiety in those ages 8 to 18 years. This is a “B” recommendation, which means there is moderate certainty that screening for anxiety in these individuals has a moderate net benefit. The USPSTF felt that the evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against screening at ages 7 years and younger.1

Anxiety is common among young people in America. A survey conducted in 2018-2019 found that 7.8% of children and adolescents (ages 3 to 17 years) had a current anxiety disorder.2 The isolation created by the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with increased rates of clinically significant psychiatric symptoms; one study suggested that in the first year of the pandemic, 20% of young people experienced elevated anxiety symptoms.3,4 Anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence also are associated with an increased likelihood of a future anxiety disorder, or depression, in adulthood.

Therapy may improve outcomes. There is evidence that treatment of anxiety disorders can result in improved clinical outcomes. Treatment options include psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both.5

However, studies showing benefit were conducted in young people whose anxiety was identified via signs or symptoms. The USPSTF could find no direct evidence that identifying anxiety in asymptomatic youth leads to better outcomes. The current draft recommendation is based on indirect evidence on the accuracy of the screening tools and the results of therapy in those who are symptomatic.

Speaking of screening tools ... There were 3 listed in the USPSTF evidence review: the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED), which assesses for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and any anxiety disorder6; the Patient Health Questionnaire-Adolescent, which screens for GAD and panic disorder7; and the Social Phobia Inventory.8 The SCARED and Social Phobia Inventory are the most widely used clinically.

The accuracy of the screening tests differed. For detection of GAD, sensitivity ranged from 50% to 88% and specificity from 63% to 98%; for social anxiety disorder, sensitivity ranged from 67% to 93% and specificity from 69% to 94%. False-positive results ranged from 17 to 361 per 1000 for GAD and from 104 to 254 per 1000 for social anxiety disorder.1

The USPSTF emphasized that anxiety should not be diagnosed based on a screening test alone. A positive screen should prompt further assessment and confirmation.

An unexpected rating. Given the opportunity costs to administer a screening tool, the high false-positive rates, and the lack of evidence that screening results in improved outcomes among asymptomatic youth, it is curious that this topic did not result in an “I” recommendation. Many screening interventions for children and adolescents with similar evidence profiles—including screening for suicide risk, drug abuse, eating disorders, and alcohol abuse—have previously received an “I.”9

Keep in mind that this is currently a draft recommendation that is open for public comment. The final recommendation will be published in 4 to 12 months.

On April 12, 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published a draft recommendation on screening for anxiety in children and adolescents. The recommendation states that clinicians should screen for anxiety in those ages 8 to 18 years. This is a “B” recommendation, which means there is moderate certainty that screening for anxiety in these individuals has a moderate net benefit. The USPSTF felt that the evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against screening at ages 7 years and younger.1

Anxiety is common among young people in America. A survey conducted in 2018-2019 found that 7.8% of children and adolescents (ages 3 to 17 years) had a current anxiety disorder.2 The isolation created by the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with increased rates of clinically significant psychiatric symptoms; one study suggested that in the first year of the pandemic, 20% of young people experienced elevated anxiety symptoms.3,4 Anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence also are associated with an increased likelihood of a future anxiety disorder, or depression, in adulthood.

Therapy may improve outcomes. There is evidence that treatment of anxiety disorders can result in improved clinical outcomes. Treatment options include psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both.5

However, studies showing benefit were conducted in young people whose anxiety was identified via signs or symptoms. The USPSTF could find no direct evidence that identifying anxiety in asymptomatic youth leads to better outcomes. The current draft recommendation is based on indirect evidence on the accuracy of the screening tools and the results of therapy in those who are symptomatic.

Speaking of screening tools ... There were 3 listed in the USPSTF evidence review: the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED), which assesses for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and any anxiety disorder6; the Patient Health Questionnaire-Adolescent, which screens for GAD and panic disorder7; and the Social Phobia Inventory.8 The SCARED and Social Phobia Inventory are the most widely used clinically.

The accuracy of the screening tests differed. For detection of GAD, sensitivity ranged from 50% to 88% and specificity from 63% to 98%; for social anxiety disorder, sensitivity ranged from 67% to 93% and specificity from 69% to 94%. False-positive results ranged from 17 to 361 per 1000 for GAD and from 104 to 254 per 1000 for social anxiety disorder.1

The USPSTF emphasized that anxiety should not be diagnosed based on a screening test alone. A positive screen should prompt further assessment and confirmation.

An unexpected rating. Given the opportunity costs to administer a screening tool, the high false-positive rates, and the lack of evidence that screening results in improved outcomes among asymptomatic youth, it is curious that this topic did not result in an “I” recommendation. Many screening interventions for children and adolescents with similar evidence profiles—including screening for suicide risk, drug abuse, eating disorders, and alcohol abuse—have previously received an “I.”9

Keep in mind that this is currently a draft recommendation that is open for public comment. The final recommendation will be published in 4 to 12 months.

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents. Draft recommendation statement. Published April 12, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

2. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed May 23, 2022. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

3. Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38:233-246. doi: 10.1002/da.23120

4. Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, et al. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1142-1150. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

5. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatr. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

6. Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, et al. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1230-1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011

7. Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:196-204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0

8. Antony MM, Coons MJ, McCabe RE, et al. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory: further evaluation. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1177-1185. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.013

9. USPSTF. Published recommendations: mental health conditions. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/topic_search_results?topic_status=P&searchterm=mental+health+conditions

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents. Draft recommendation statement. Published April 12, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

2. US Census Bureau. 2020 National Survey of Children’s Health: Topical Frequencies. Published June 2, 2021. Accessed May 23, 2022. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch/technical-documentation/codebook/NSCH_2020_Topical_Frequencies.pdf

3. Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38:233-246. doi: 10.1002/da.23120

4. Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, et al. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1142-1150. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

5. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatr. 2019;206:256-267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

6. Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, et al. Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1230-1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011

7. Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:196-204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0

8. Antony MM, Coons MJ, McCabe RE, et al. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory: further evaluation. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1177-1185. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.013

9. USPSTF. Published recommendations: mental health conditions. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/topic_search_results?topic_status=P&searchterm=mental+health+conditions

USPSTF recommendation roundup

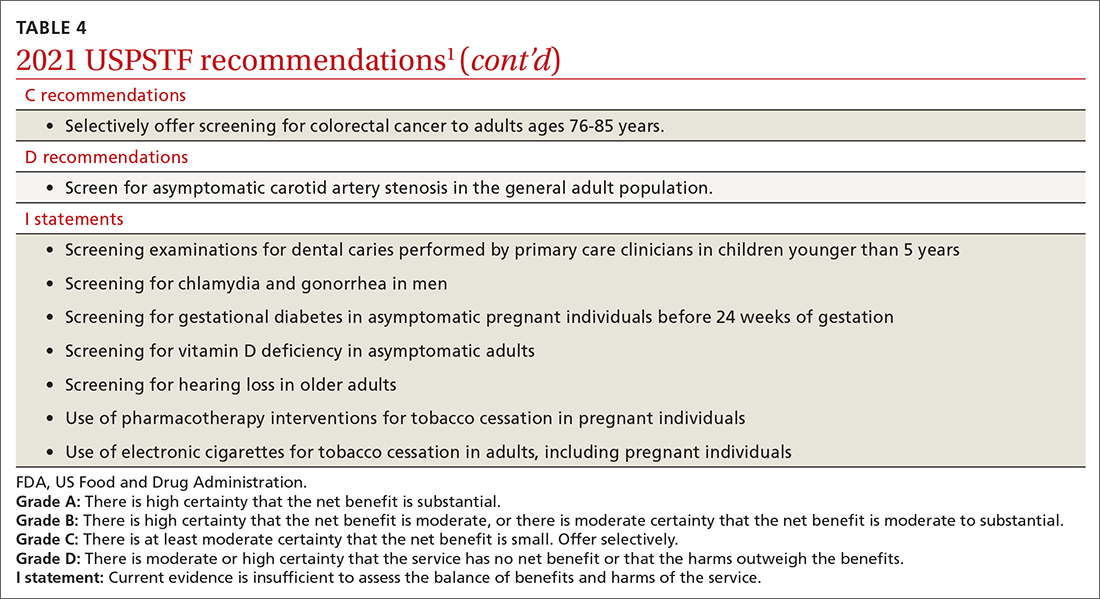

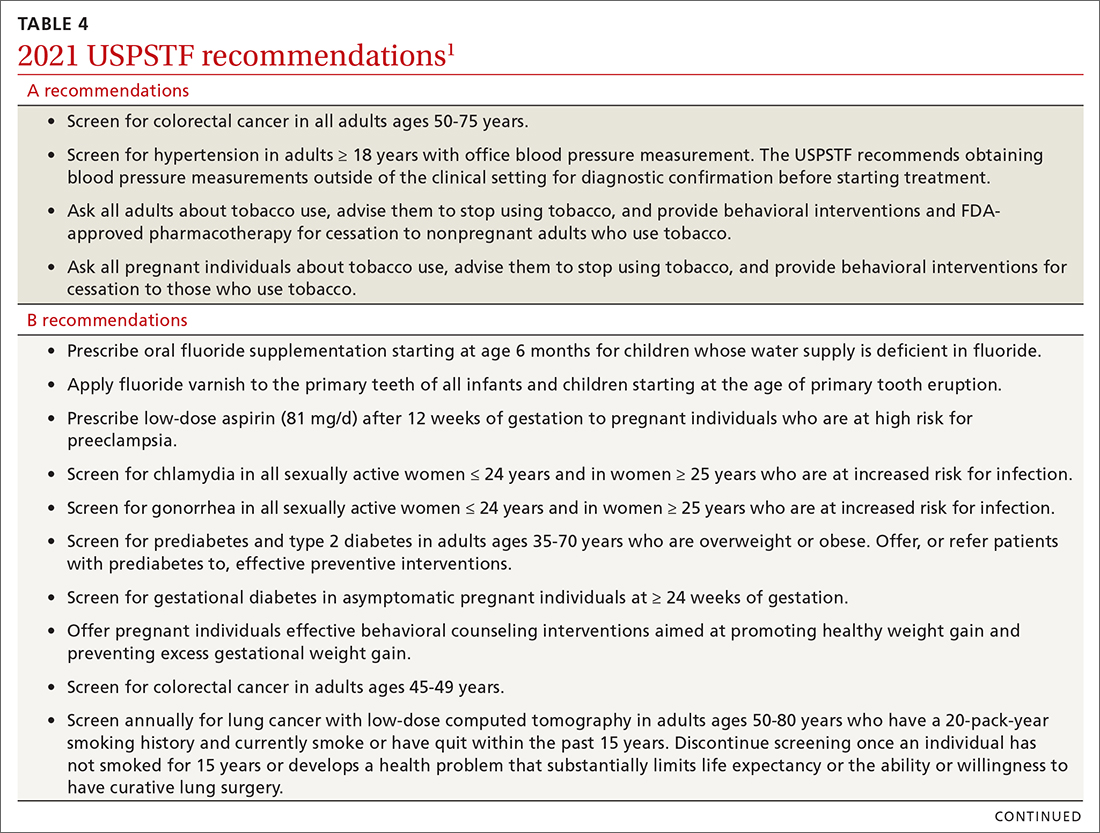

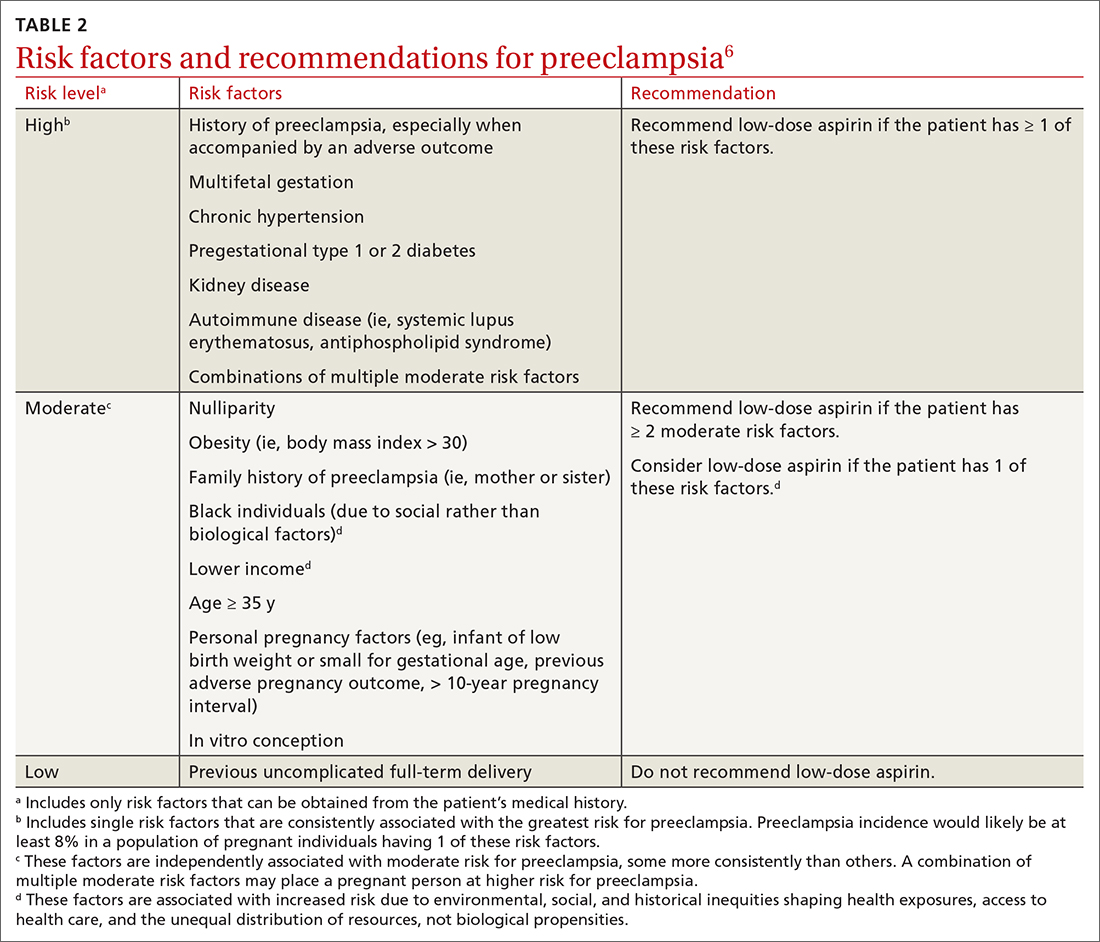

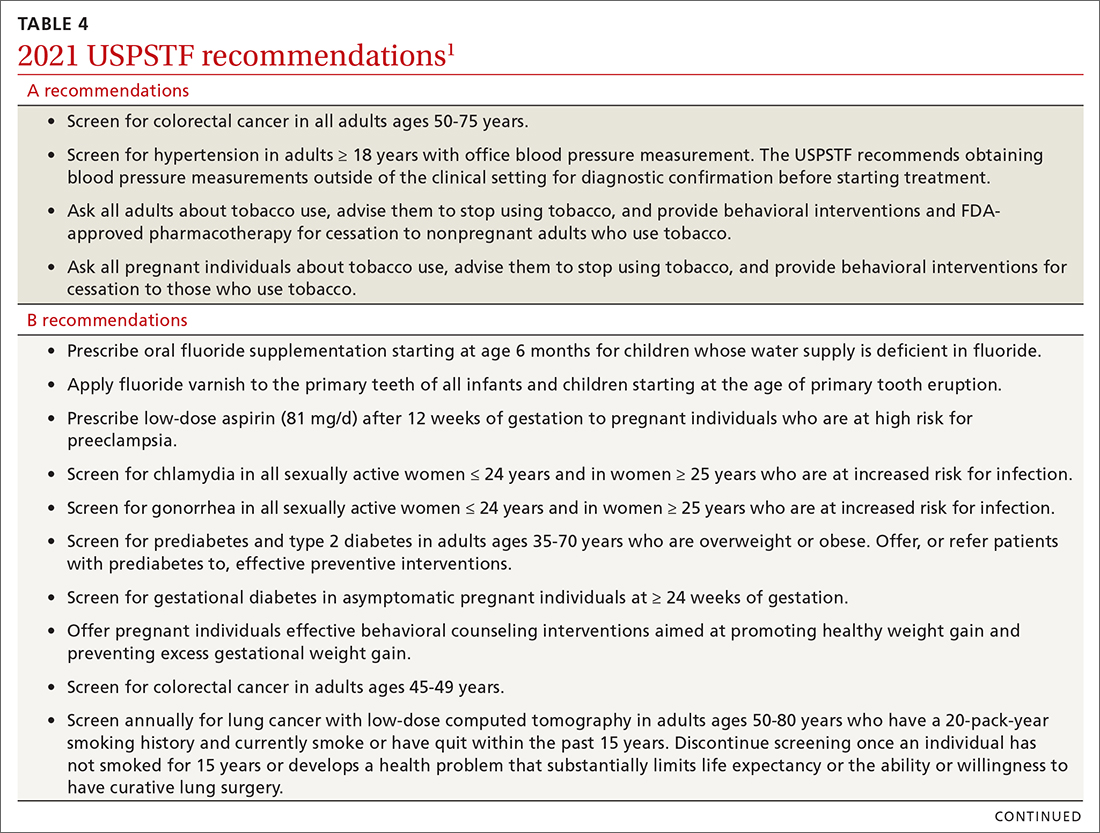

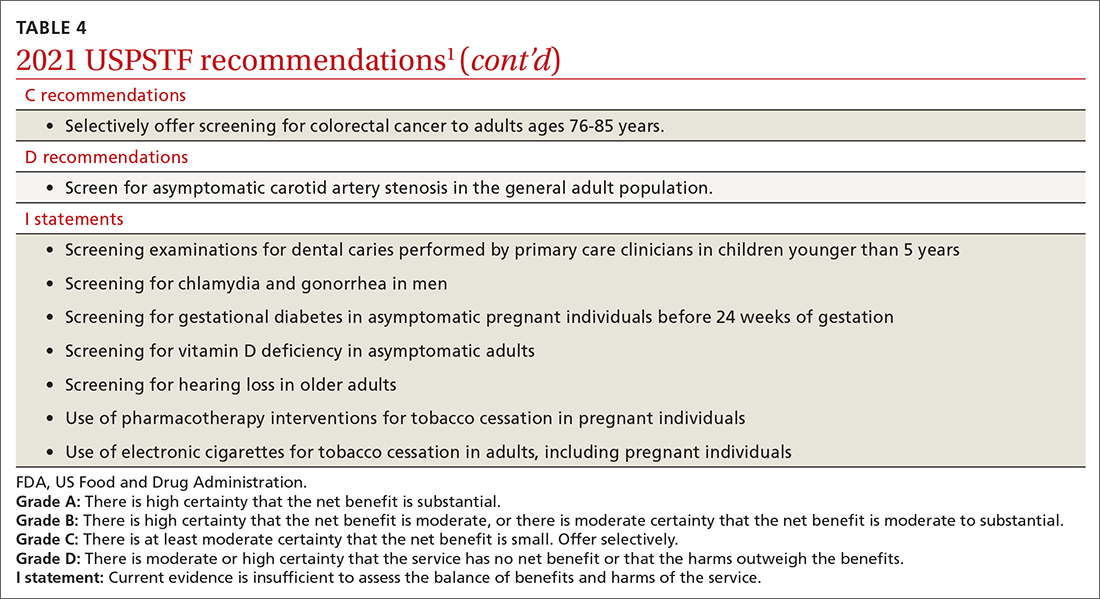

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) considered 13 topics and made a total of 23 recommendations. They reviewed only 1 new topic. The other 12 were updates of topics previously addressed; no changes were made in 9 of them. In 3, the recommended age of screening or the criteria for screening were expanded. This Practice Alert will review the recommendations made and highlight new recommendations and any changes to previous ones. All complete recommendation statements, rationales, clinical considerations, and evidence reports can be found on the USPSTF website at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/home.1

Dental caries in children

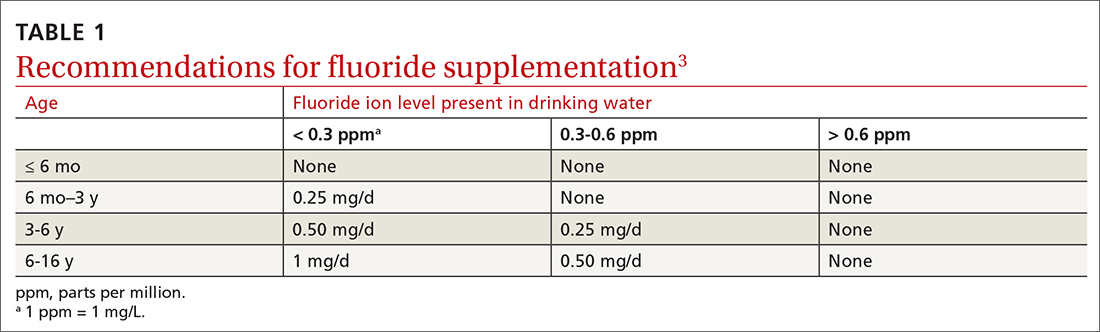

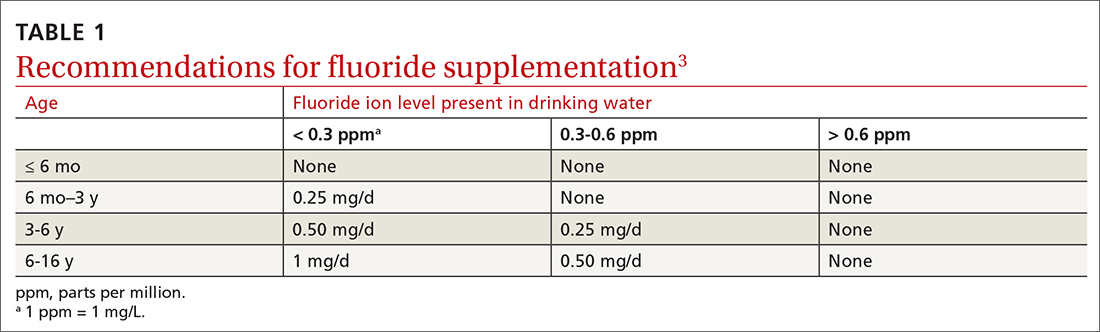

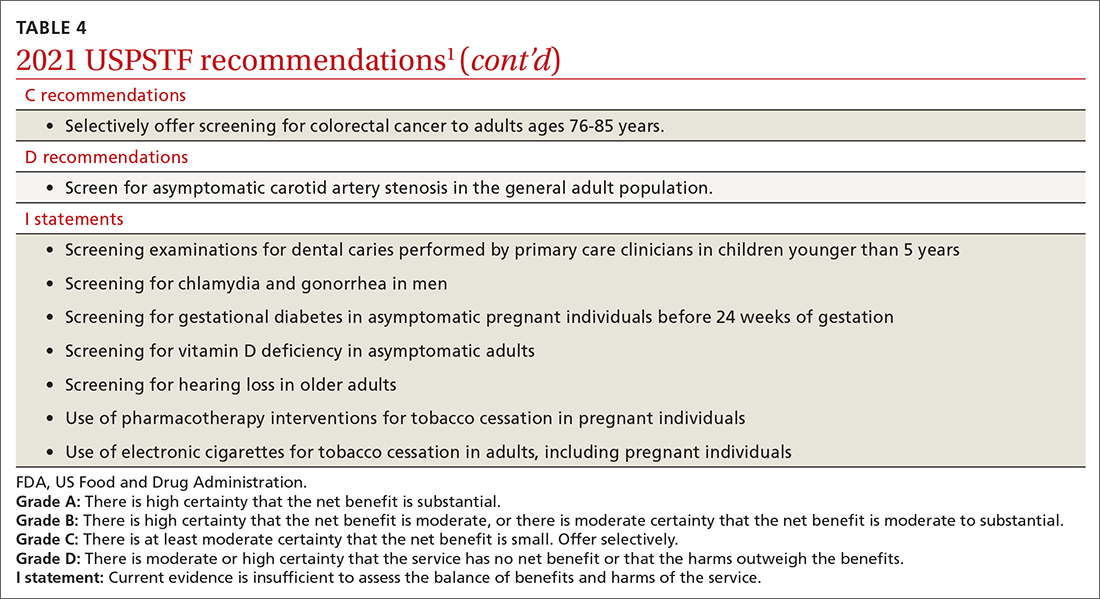

Dental caries affect about 23% of children between the ages of 2 and 5 years and are associated with multiple adverse social outcomes and medical conditions.2 The best way to prevent tooth decay, other than regular brushing with fluoride toothpaste, is to drink water with recommended amounts of fluoride (≥ 0.6 parts fluoride per million parts water).2 The USPSTF reaffirmed its recommendation from 2014 that stated when a local water supply lacks sufficient fluoride, primary care clinicians should prescribe oral supplementation for infants and children in the form of fluoride drops starting at age 6 months. The dosage of fluoride depends on patient age and fluoride concentration in the local water (TABLE 13). The USPSTF also recommends applying topical fluoride as 5% sodium fluoride varnish, every 6 months, starting when the primary teeth erupt.2

In addition to fluoride supplements and topical varnish, should clinicians perform screening examinations looking for dental caries? The USPSTF feels there is not enough evidence to assess this practice and gives it an “I” rating (insufficient evidence).

Preventive interventions in pregnancy

In 2021, the USPSTF assessed 3 topics related to pregnancy and prenatal care.

Screening for gestational diabetes. The USPSTF gave a “B” recommendation for screening at 24 weeks of pregnancy or after, but an “I” statement for screening prior to 24 weeks.4 Screening can involve a 1-step or 2-step protocol.

The 2-step protocol is most commonly used in the United States. It involves first measuring serum glucose after a nonfasting 50-g oral glucose challenge; if the resulting level is high, the second step is a 75- or 100-g oral glucose tolerance test lasting 3 hours. The 1-step protocol involves measuring a fasting glucose level, followed by a 75-g oral glucose challenge with glucose levels measured at 1 and 2 hours.

Healthy weight gain in pregnancy. This was the only new topic the USPSTF assessed last year. The resulting recommendation is to offer pregnant women behavioral counseling to promote healthy weight gain and to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnancy. The recommended weight gain depends on the mother’s prepregnancy weight status: 28 to 40 lbs if the mother is underweight; 25 to 35 lbs if she is not under- or overweight; 15 to 25 lbs if she is overweight; and 11 to 20 lbs if she is obese.5 Healthy weight gain contributes to preventing gestational diabetes, emergency cesarean sections, and infant macrosomia.

Continue to: Low-dose aspirin

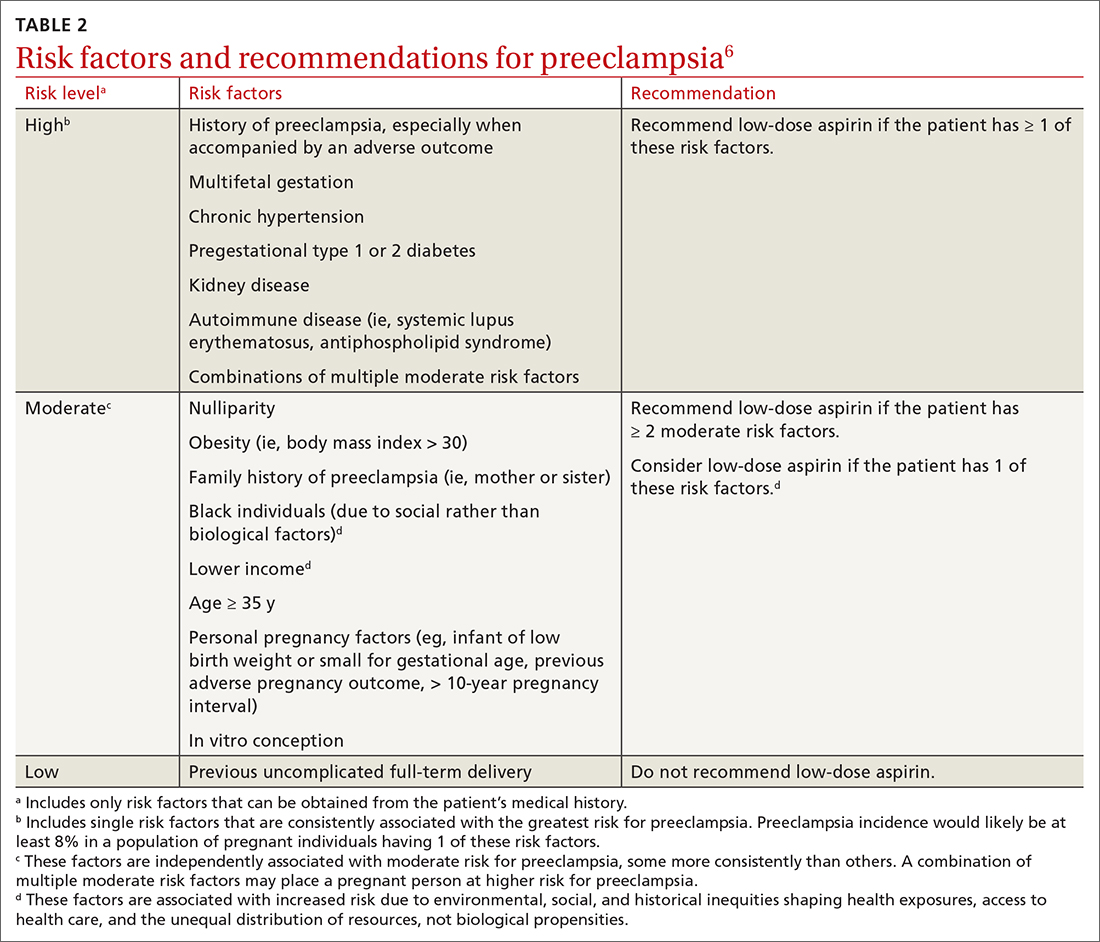

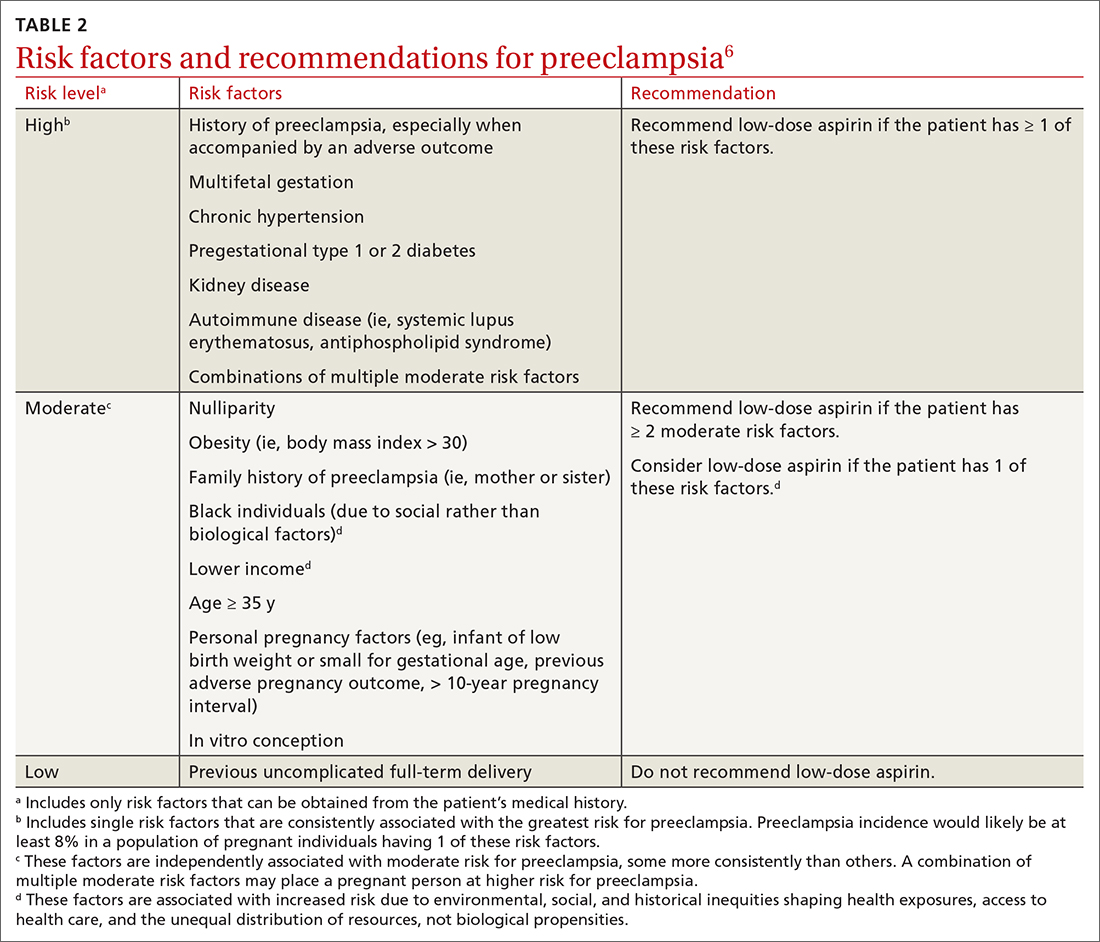

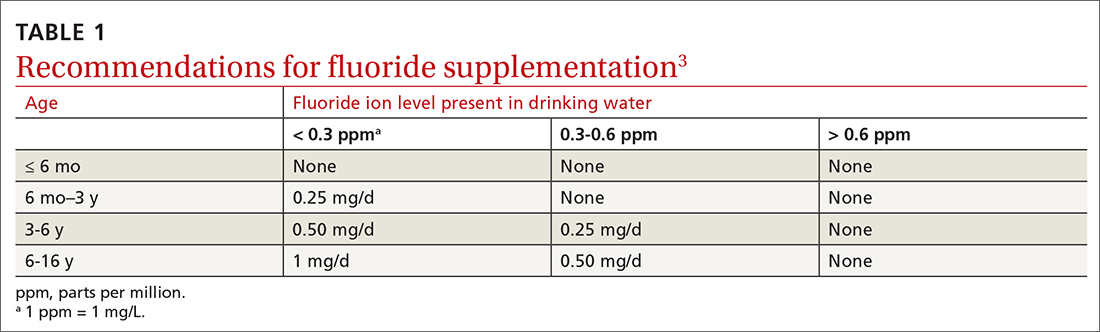

Low-dose aspirin. Reaffirming a recommendation from 2014, the USPSTF advises low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) starting after 12 weeks’ gestation for all pregnant women who are at high risk for preeclampsia. TABLE 26 lists high- and moderate-risk conditions for preeclampsia and the recommendation for the use of low-dose aspirin.

Sexually transmitted infections

Screening for both chlamydia and gonorrhea in sexually active females through age 24 years was given a “B” recommendation, reaffirming the 2014 recommendation.7 Screening for these 2 sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is also recommended for women 25 years and older who are at increased risk of STIs. Risk is defined as having a new sex partner, more than 1 sex partner, a sex partner who has other sex partners, or a sex partner who has an STI; not using condoms consistently; having a previous STI; exchanging sex for money or drugs; or having a history of incarceration.

Screen for both infections simultaneously using a nucleic acid amplification test, testing all sites of sexual exposure. Urine testing can replace cervical, vaginal, and urethral testing. Those found to be positive for either STI should be treated according to the most recent treatment guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And sexual partners should be advised to undergo testing.8,9

The USPSTF could not find evidence for the benefits and harms of screening for STIs in men. Remember that screening applies to those who are asymptomatic. Male sex partners of those found to be infected should be tested, as should those who show any signs or symptoms of an STI. A recent Practice Alert described the most current CDC guidance for diagnosing and treating STIs.9

Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

Screening for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes is now recommended for adults ages 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese.10 The age to start screening has been lowered to 35 years from the previous recommendation in 2015, which recommended starting at age 40. In addition, the recommendation states that patients with prediabetes should be referred for preventive interventions. It is important that referral is included in the statement because the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations must be covered by commercial health insurance with no copay or deductible.

Continue to: Screening can be conducted...

Screening can be conducted using a fasting plasma glucose or A1C level, or with an oral glucose tolerance test. Interventions that can prevent or delay the onset of T2D in those with prediabetes include lifestyle interventions that focus on diet and physical activity, and the use of metformin (although metformin has not been approved for this by the US Food and Drug Administration).

Changes to cancer screening recommendations

In 2021, the USPSTF reviewed and modified its recommendations on screening for 2 types of cancer: colorectal and lung.

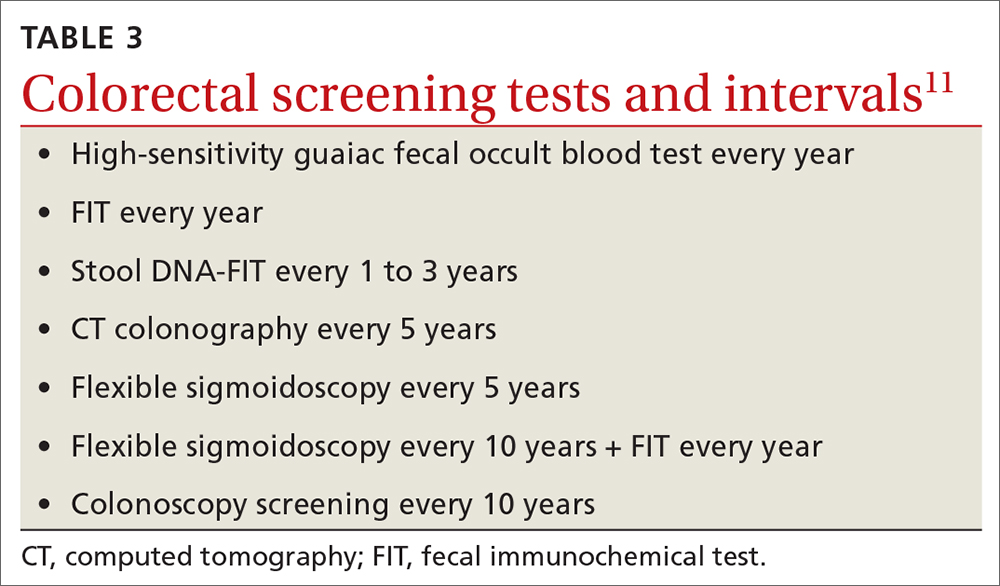

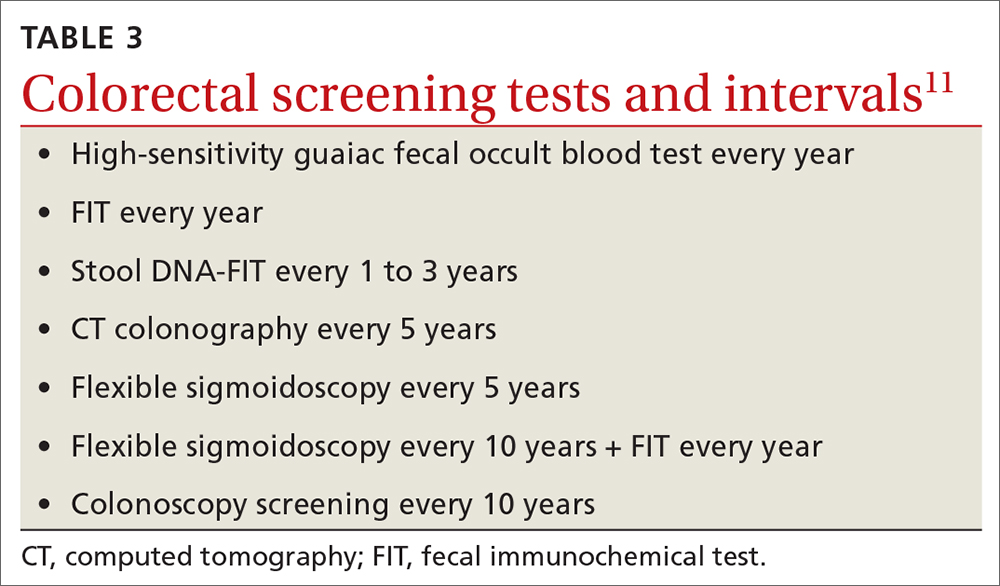

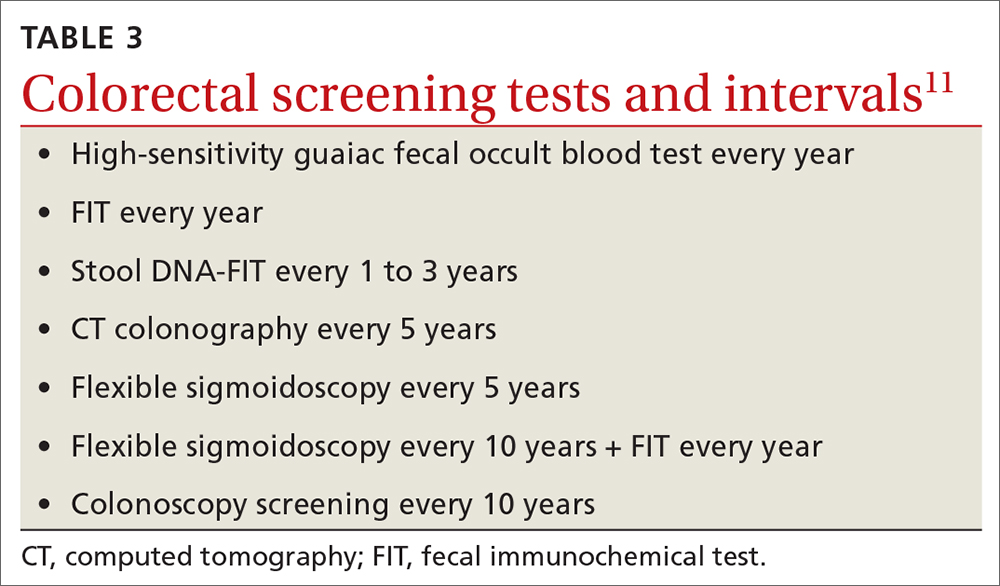

For colorectal cancer, the age at which to start screening was lowered from 50 years to 45 years.11 Screening at this earlier age is a “B” recommendation, because, while there is benefit from screening, it is less than for older age groups. Screening individuals ages 50 to 75 years remains an “A” recommendation, and for those ages 76 to 85 years it remains a “C” recommendation. A “C” recommendation means that the overall benefits are small but some individuals might benefit based on their overall health and prior screening results. In its clinical considerations, the USPSTF recommends against screening in those ages 85 and older but, curiously, does not list it as a “D” recommendation. The screening methods and recommended screening intervals for each appear in TABLE 3.11

For lung cancer, annual screening using low-dose computed tomography (CT) was first recommended by the USPSTF in 2013 for adults ages 55 to 80 years with a 30-pack-year smoking history. Screening could stop once 15 years had passed since smoking cessation. In 2021, the USPSTF lowered the age to initiate screening to 50 years, and the smoking history threshold to 20 pack-years.12 If these recommendations are followed, a current smoker who does not quit smoking could possibly receive 30 annual CT scans. The recommendation does state that screening should stop once a person develops a health condition that significantly affects life expectancy or ability to have lung surgery.

For primary prevention of lung cancer and other chronic diseases through smoking cessation, the USPSTF also reassessed its 2015 recommendations. It reaffirmed the “A” recommendation to ask adults about tobacco use and, for tobacco users, to recommend cessation and provide behavioral therapy and approved pharmacotherapy.13 The recommendation differed for pregnant adults in that the USPSTF is unsure about the potential harms of pharmacotherapy in pregnancy and gives that an “I” statement.13 An additional “I” statement was made about the use of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation; the USPSTF recommends using behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions with proven effectiveness and safety instead.

Continue to: 4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

Screening for high blood pressure in adults ages 18 years and older continues to receive an “A” recommendation.14 Importantly, the recommendation states that confirmation of high blood pressure should be made in an out-of-office setting before initiating treatment. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults and hearing loss in older adults both continue with “I” statements,15,16 and screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis continues to receive a “D” recommendation.17 The implications of the vitamin D “I” statement were discussed in a previous Practice Alert.18

Continuing value of the USPSTF

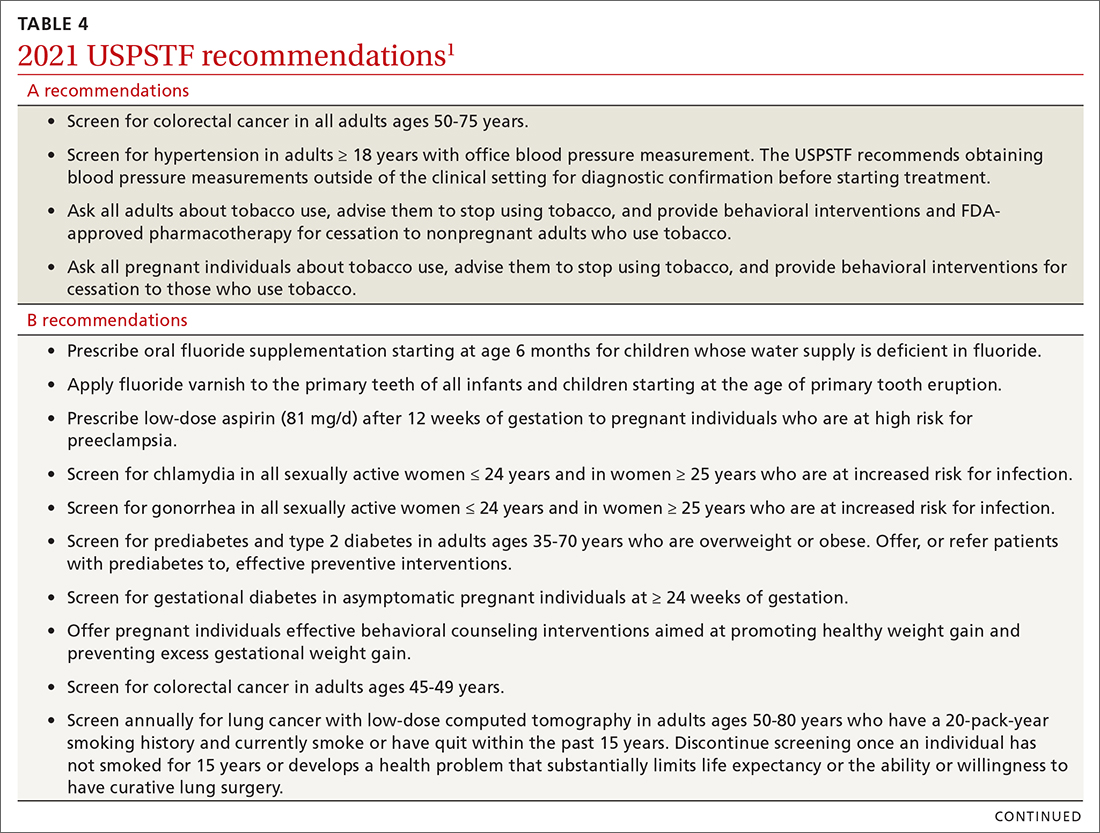

The USPSTF continues to set the gold standard for assessment of preventive interventions, and its decisions affect first-dollar coverage by commercial health insurance. The reaffirmation of past recommendations demonstrates the value of adhering to rigorous evidence-based methods (if they are done correctly, they rarely must be markedly changed). And the updating of screening criteria shows the need to constantly review the evolving evidence for current recommendations. Once again, however, funding and staffing limitations allowed the USPSTF to assess only 1 new topic. A listing of all the 2021 recommendations is in TABLE 4.1

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Prevention of dental caries in children younger than 5 years: screening and interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-dental-caries-in-children-younger-than-age-5-years-screening-and-interventions1#bootstrap-panel—4

3. ADA. Dietary fluoride supplements: evidence-based clinical recommendations. Accessed April 14, 2022. www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/ada_evidence-based_fluoride_supplement_chairside_guide.pdf?rev=60850dca0dcc41038efda83d42b1c2e0&hash=FEC2BBEA0C892FB12C098E33344E48B4

4. USPSTF. Gestational diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/gestational-diabetes-screening

5. USPSTF. Healthy weight and weight gain in pregnancy: behavioral counseling interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-weight-and-weight-gain-during-pregnancy-behavioral-counseling-interventions

6. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: preventive medication. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication

7. USPSTF. Chlamydia and gonorrhea: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening

8. Workowski KA, Bauchman LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC guidelines on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:506-509.

10. USPSTF. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-for-prediabetes-and-type-2-diabetes

11. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

12. USPSTF. Lung cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

13. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

14. USPSTF. Hypertension in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hypertension-in-adults-screening

15. USPSTF. Vitamin D deficiency in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-deficiency-screening

16. USPSTF. Hearing loss in older adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hearing-loss-in-older-adults-screening

17. USPSTF. Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: screening. Access April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

18. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292.

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) considered 13 topics and made a total of 23 recommendations. They reviewed only 1 new topic. The other 12 were updates of topics previously addressed; no changes were made in 9 of them. In 3, the recommended age of screening or the criteria for screening were expanded. This Practice Alert will review the recommendations made and highlight new recommendations and any changes to previous ones. All complete recommendation statements, rationales, clinical considerations, and evidence reports can be found on the USPSTF website at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/home.1

Dental caries in children

Dental caries affect about 23% of children between the ages of 2 and 5 years and are associated with multiple adverse social outcomes and medical conditions.2 The best way to prevent tooth decay, other than regular brushing with fluoride toothpaste, is to drink water with recommended amounts of fluoride (≥ 0.6 parts fluoride per million parts water).2 The USPSTF reaffirmed its recommendation from 2014 that stated when a local water supply lacks sufficient fluoride, primary care clinicians should prescribe oral supplementation for infants and children in the form of fluoride drops starting at age 6 months. The dosage of fluoride depends on patient age and fluoride concentration in the local water (TABLE 13). The USPSTF also recommends applying topical fluoride as 5% sodium fluoride varnish, every 6 months, starting when the primary teeth erupt.2

In addition to fluoride supplements and topical varnish, should clinicians perform screening examinations looking for dental caries? The USPSTF feels there is not enough evidence to assess this practice and gives it an “I” rating (insufficient evidence).

Preventive interventions in pregnancy

In 2021, the USPSTF assessed 3 topics related to pregnancy and prenatal care.

Screening for gestational diabetes. The USPSTF gave a “B” recommendation for screening at 24 weeks of pregnancy or after, but an “I” statement for screening prior to 24 weeks.4 Screening can involve a 1-step or 2-step protocol.

The 2-step protocol is most commonly used in the United States. It involves first measuring serum glucose after a nonfasting 50-g oral glucose challenge; if the resulting level is high, the second step is a 75- or 100-g oral glucose tolerance test lasting 3 hours. The 1-step protocol involves measuring a fasting glucose level, followed by a 75-g oral glucose challenge with glucose levels measured at 1 and 2 hours.

Healthy weight gain in pregnancy. This was the only new topic the USPSTF assessed last year. The resulting recommendation is to offer pregnant women behavioral counseling to promote healthy weight gain and to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnancy. The recommended weight gain depends on the mother’s prepregnancy weight status: 28 to 40 lbs if the mother is underweight; 25 to 35 lbs if she is not under- or overweight; 15 to 25 lbs if she is overweight; and 11 to 20 lbs if she is obese.5 Healthy weight gain contributes to preventing gestational diabetes, emergency cesarean sections, and infant macrosomia.

Continue to: Low-dose aspirin

Low-dose aspirin. Reaffirming a recommendation from 2014, the USPSTF advises low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) starting after 12 weeks’ gestation for all pregnant women who are at high risk for preeclampsia. TABLE 26 lists high- and moderate-risk conditions for preeclampsia and the recommendation for the use of low-dose aspirin.

Sexually transmitted infections

Screening for both chlamydia and gonorrhea in sexually active females through age 24 years was given a “B” recommendation, reaffirming the 2014 recommendation.7 Screening for these 2 sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is also recommended for women 25 years and older who are at increased risk of STIs. Risk is defined as having a new sex partner, more than 1 sex partner, a sex partner who has other sex partners, or a sex partner who has an STI; not using condoms consistently; having a previous STI; exchanging sex for money or drugs; or having a history of incarceration.

Screen for both infections simultaneously using a nucleic acid amplification test, testing all sites of sexual exposure. Urine testing can replace cervical, vaginal, and urethral testing. Those found to be positive for either STI should be treated according to the most recent treatment guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And sexual partners should be advised to undergo testing.8,9

The USPSTF could not find evidence for the benefits and harms of screening for STIs in men. Remember that screening applies to those who are asymptomatic. Male sex partners of those found to be infected should be tested, as should those who show any signs or symptoms of an STI. A recent Practice Alert described the most current CDC guidance for diagnosing and treating STIs.9

Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

Screening for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes is now recommended for adults ages 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese.10 The age to start screening has been lowered to 35 years from the previous recommendation in 2015, which recommended starting at age 40. In addition, the recommendation states that patients with prediabetes should be referred for preventive interventions. It is important that referral is included in the statement because the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations must be covered by commercial health insurance with no copay or deductible.

Continue to: Screening can be conducted...

Screening can be conducted using a fasting plasma glucose or A1C level, or with an oral glucose tolerance test. Interventions that can prevent or delay the onset of T2D in those with prediabetes include lifestyle interventions that focus on diet and physical activity, and the use of metformin (although metformin has not been approved for this by the US Food and Drug Administration).

Changes to cancer screening recommendations

In 2021, the USPSTF reviewed and modified its recommendations on screening for 2 types of cancer: colorectal and lung.

For colorectal cancer, the age at which to start screening was lowered from 50 years to 45 years.11 Screening at this earlier age is a “B” recommendation, because, while there is benefit from screening, it is less than for older age groups. Screening individuals ages 50 to 75 years remains an “A” recommendation, and for those ages 76 to 85 years it remains a “C” recommendation. A “C” recommendation means that the overall benefits are small but some individuals might benefit based on their overall health and prior screening results. In its clinical considerations, the USPSTF recommends against screening in those ages 85 and older but, curiously, does not list it as a “D” recommendation. The screening methods and recommended screening intervals for each appear in TABLE 3.11

For lung cancer, annual screening using low-dose computed tomography (CT) was first recommended by the USPSTF in 2013 for adults ages 55 to 80 years with a 30-pack-year smoking history. Screening could stop once 15 years had passed since smoking cessation. In 2021, the USPSTF lowered the age to initiate screening to 50 years, and the smoking history threshold to 20 pack-years.12 If these recommendations are followed, a current smoker who does not quit smoking could possibly receive 30 annual CT scans. The recommendation does state that screening should stop once a person develops a health condition that significantly affects life expectancy or ability to have lung surgery.

For primary prevention of lung cancer and other chronic diseases through smoking cessation, the USPSTF also reassessed its 2015 recommendations. It reaffirmed the “A” recommendation to ask adults about tobacco use and, for tobacco users, to recommend cessation and provide behavioral therapy and approved pharmacotherapy.13 The recommendation differed for pregnant adults in that the USPSTF is unsure about the potential harms of pharmacotherapy in pregnancy and gives that an “I” statement.13 An additional “I” statement was made about the use of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation; the USPSTF recommends using behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions with proven effectiveness and safety instead.

Continue to: 4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

Screening for high blood pressure in adults ages 18 years and older continues to receive an “A” recommendation.14 Importantly, the recommendation states that confirmation of high blood pressure should be made in an out-of-office setting before initiating treatment. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults and hearing loss in older adults both continue with “I” statements,15,16 and screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis continues to receive a “D” recommendation.17 The implications of the vitamin D “I” statement were discussed in a previous Practice Alert.18

Continuing value of the USPSTF

The USPSTF continues to set the gold standard for assessment of preventive interventions, and its decisions affect first-dollar coverage by commercial health insurance. The reaffirmation of past recommendations demonstrates the value of adhering to rigorous evidence-based methods (if they are done correctly, they rarely must be markedly changed). And the updating of screening criteria shows the need to constantly review the evolving evidence for current recommendations. Once again, however, funding and staffing limitations allowed the USPSTF to assess only 1 new topic. A listing of all the 2021 recommendations is in TABLE 4.1

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) considered 13 topics and made a total of 23 recommendations. They reviewed only 1 new topic. The other 12 were updates of topics previously addressed; no changes were made in 9 of them. In 3, the recommended age of screening or the criteria for screening were expanded. This Practice Alert will review the recommendations made and highlight new recommendations and any changes to previous ones. All complete recommendation statements, rationales, clinical considerations, and evidence reports can be found on the USPSTF website at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/home.1

Dental caries in children

Dental caries affect about 23% of children between the ages of 2 and 5 years and are associated with multiple adverse social outcomes and medical conditions.2 The best way to prevent tooth decay, other than regular brushing with fluoride toothpaste, is to drink water with recommended amounts of fluoride (≥ 0.6 parts fluoride per million parts water).2 The USPSTF reaffirmed its recommendation from 2014 that stated when a local water supply lacks sufficient fluoride, primary care clinicians should prescribe oral supplementation for infants and children in the form of fluoride drops starting at age 6 months. The dosage of fluoride depends on patient age and fluoride concentration in the local water (TABLE 13). The USPSTF also recommends applying topical fluoride as 5% sodium fluoride varnish, every 6 months, starting when the primary teeth erupt.2

In addition to fluoride supplements and topical varnish, should clinicians perform screening examinations looking for dental caries? The USPSTF feels there is not enough evidence to assess this practice and gives it an “I” rating (insufficient evidence).

Preventive interventions in pregnancy

In 2021, the USPSTF assessed 3 topics related to pregnancy and prenatal care.

Screening for gestational diabetes. The USPSTF gave a “B” recommendation for screening at 24 weeks of pregnancy or after, but an “I” statement for screening prior to 24 weeks.4 Screening can involve a 1-step or 2-step protocol.

The 2-step protocol is most commonly used in the United States. It involves first measuring serum glucose after a nonfasting 50-g oral glucose challenge; if the resulting level is high, the second step is a 75- or 100-g oral glucose tolerance test lasting 3 hours. The 1-step protocol involves measuring a fasting glucose level, followed by a 75-g oral glucose challenge with glucose levels measured at 1 and 2 hours.

Healthy weight gain in pregnancy. This was the only new topic the USPSTF assessed last year. The resulting recommendation is to offer pregnant women behavioral counseling to promote healthy weight gain and to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnancy. The recommended weight gain depends on the mother’s prepregnancy weight status: 28 to 40 lbs if the mother is underweight; 25 to 35 lbs if she is not under- or overweight; 15 to 25 lbs if she is overweight; and 11 to 20 lbs if she is obese.5 Healthy weight gain contributes to preventing gestational diabetes, emergency cesarean sections, and infant macrosomia.

Continue to: Low-dose aspirin

Low-dose aspirin. Reaffirming a recommendation from 2014, the USPSTF advises low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) starting after 12 weeks’ gestation for all pregnant women who are at high risk for preeclampsia. TABLE 26 lists high- and moderate-risk conditions for preeclampsia and the recommendation for the use of low-dose aspirin.

Sexually transmitted infections

Screening for both chlamydia and gonorrhea in sexually active females through age 24 years was given a “B” recommendation, reaffirming the 2014 recommendation.7 Screening for these 2 sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is also recommended for women 25 years and older who are at increased risk of STIs. Risk is defined as having a new sex partner, more than 1 sex partner, a sex partner who has other sex partners, or a sex partner who has an STI; not using condoms consistently; having a previous STI; exchanging sex for money or drugs; or having a history of incarceration.

Screen for both infections simultaneously using a nucleic acid amplification test, testing all sites of sexual exposure. Urine testing can replace cervical, vaginal, and urethral testing. Those found to be positive for either STI should be treated according to the most recent treatment guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And sexual partners should be advised to undergo testing.8,9

The USPSTF could not find evidence for the benefits and harms of screening for STIs in men. Remember that screening applies to those who are asymptomatic. Male sex partners of those found to be infected should be tested, as should those who show any signs or symptoms of an STI. A recent Practice Alert described the most current CDC guidance for diagnosing and treating STIs.9

Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

Screening for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes is now recommended for adults ages 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese.10 The age to start screening has been lowered to 35 years from the previous recommendation in 2015, which recommended starting at age 40. In addition, the recommendation states that patients with prediabetes should be referred for preventive interventions. It is important that referral is included in the statement because the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations must be covered by commercial health insurance with no copay or deductible.

Continue to: Screening can be conducted...

Screening can be conducted using a fasting plasma glucose or A1C level, or with an oral glucose tolerance test. Interventions that can prevent or delay the onset of T2D in those with prediabetes include lifestyle interventions that focus on diet and physical activity, and the use of metformin (although metformin has not been approved for this by the US Food and Drug Administration).

Changes to cancer screening recommendations

In 2021, the USPSTF reviewed and modified its recommendations on screening for 2 types of cancer: colorectal and lung.

For colorectal cancer, the age at which to start screening was lowered from 50 years to 45 years.11 Screening at this earlier age is a “B” recommendation, because, while there is benefit from screening, it is less than for older age groups. Screening individuals ages 50 to 75 years remains an “A” recommendation, and for those ages 76 to 85 years it remains a “C” recommendation. A “C” recommendation means that the overall benefits are small but some individuals might benefit based on their overall health and prior screening results. In its clinical considerations, the USPSTF recommends against screening in those ages 85 and older but, curiously, does not list it as a “D” recommendation. The screening methods and recommended screening intervals for each appear in TABLE 3.11

For lung cancer, annual screening using low-dose computed tomography (CT) was first recommended by the USPSTF in 2013 for adults ages 55 to 80 years with a 30-pack-year smoking history. Screening could stop once 15 years had passed since smoking cessation. In 2021, the USPSTF lowered the age to initiate screening to 50 years, and the smoking history threshold to 20 pack-years.12 If these recommendations are followed, a current smoker who does not quit smoking could possibly receive 30 annual CT scans. The recommendation does state that screening should stop once a person develops a health condition that significantly affects life expectancy or ability to have lung surgery.

For primary prevention of lung cancer and other chronic diseases through smoking cessation, the USPSTF also reassessed its 2015 recommendations. It reaffirmed the “A” recommendation to ask adults about tobacco use and, for tobacco users, to recommend cessation and provide behavioral therapy and approved pharmacotherapy.13 The recommendation differed for pregnant adults in that the USPSTF is unsure about the potential harms of pharmacotherapy in pregnancy and gives that an “I” statement.13 An additional “I” statement was made about the use of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation; the USPSTF recommends using behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions with proven effectiveness and safety instead.

Continue to: 4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

Screening for high blood pressure in adults ages 18 years and older continues to receive an “A” recommendation.14 Importantly, the recommendation states that confirmation of high blood pressure should be made in an out-of-office setting before initiating treatment. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults and hearing loss in older adults both continue with “I” statements,15,16 and screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis continues to receive a “D” recommendation.17 The implications of the vitamin D “I” statement were discussed in a previous Practice Alert.18

Continuing value of the USPSTF

The USPSTF continues to set the gold standard for assessment of preventive interventions, and its decisions affect first-dollar coverage by commercial health insurance. The reaffirmation of past recommendations demonstrates the value of adhering to rigorous evidence-based methods (if they are done correctly, they rarely must be markedly changed). And the updating of screening criteria shows the need to constantly review the evolving evidence for current recommendations. Once again, however, funding and staffing limitations allowed the USPSTF to assess only 1 new topic. A listing of all the 2021 recommendations is in TABLE 4.1

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Prevention of dental caries in children younger than 5 years: screening and interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-dental-caries-in-children-younger-than-age-5-years-screening-and-interventions1#bootstrap-panel—4

3. ADA. Dietary fluoride supplements: evidence-based clinical recommendations. Accessed April 14, 2022. www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/ada_evidence-based_fluoride_supplement_chairside_guide.pdf?rev=60850dca0dcc41038efda83d42b1c2e0&hash=FEC2BBEA0C892FB12C098E33344E48B4

4. USPSTF. Gestational diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/gestational-diabetes-screening

5. USPSTF. Healthy weight and weight gain in pregnancy: behavioral counseling interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-weight-and-weight-gain-during-pregnancy-behavioral-counseling-interventions

6. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: preventive medication. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication

7. USPSTF. Chlamydia and gonorrhea: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening

8. Workowski KA, Bauchman LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC guidelines on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:506-509.

10. USPSTF. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-for-prediabetes-and-type-2-diabetes

11. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

12. USPSTF. Lung cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

13. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

14. USPSTF. Hypertension in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hypertension-in-adults-screening

15. USPSTF. Vitamin D deficiency in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-deficiency-screening

16. USPSTF. Hearing loss in older adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hearing-loss-in-older-adults-screening

17. USPSTF. Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: screening. Access April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

18. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292.

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Prevention of dental caries in children younger than 5 years: screening and interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-dental-caries-in-children-younger-than-age-5-years-screening-and-interventions1#bootstrap-panel—4

3. ADA. Dietary fluoride supplements: evidence-based clinical recommendations. Accessed April 14, 2022. www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/ada_evidence-based_fluoride_supplement_chairside_guide.pdf?rev=60850dca0dcc41038efda83d42b1c2e0&hash=FEC2BBEA0C892FB12C098E33344E48B4

4. USPSTF. Gestational diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/gestational-diabetes-screening

5. USPSTF. Healthy weight and weight gain in pregnancy: behavioral counseling interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-weight-and-weight-gain-during-pregnancy-behavioral-counseling-interventions

6. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: preventive medication. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication

7. USPSTF. Chlamydia and gonorrhea: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening

8. Workowski KA, Bauchman LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC guidelines on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:506-509.

10. USPSTF. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-for-prediabetes-and-type-2-diabetes

11. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

12. USPSTF. Lung cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

13. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

14. USPSTF. Hypertension in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hypertension-in-adults-screening

15. USPSTF. Vitamin D deficiency in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-deficiency-screening

16. USPSTF. Hearing loss in older adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hearing-loss-in-older-adults-screening

17. USPSTF. Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: screening. Access April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

18. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292.

Should you be screening for eating disorders?

The US Preventive Services Task Force recently released its findings on screening for eating disorders—including binge eating, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa—in adolescents and adults.1 This is the first time the Task Force has addressed this topic.

For those who have no signs or symptoms of an eating disorder, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening. Signs and symptoms of an eating disorder include rapid changes in weight (gain or loss), delayed puberty, bradycardia, oligomenorrhea, or amenorrhea.1

Screening vs diagnostic work-up. The term screening means looking for the presence of a condition in an asymptomatic person. Those who have signs or symptoms that could be due to an eating disorder should be assessed for these conditions, but this would be classified as diagnostic testing rather than preventive screening.

Relatively uncommon but serious. The estimated lifetime prevalence of anorexia is 1.42% in women and 0.12% in men; for bulimia, 0.46% in women and 0.08% in men; and for binge eating, 1.25% in women and 0.42% in men.1 Those suspected of having an eating disorder need psychological, behavioral, medical, and nutritional care provided by those with expertise in diagnosing and treating these disorders. (A systematic review of treatment options was recently published in American Family Physician.2)

If you suspect an eating disorder … Several tools for the assessment of eating disorders have been described in the literature, including the Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (EDS-PC) tool, but the Task Force identified enough evidence to comment on the accuracy of only one: the SCOFF questionnaire. There is adequate evidence on its accuracy for use in adult women but not in adolescents or males.1

The SCOFF tool, which originated in the United Kingdom, consists of 5 questions3:

- Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry that you have lost Control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than One stone (14 lb) in a 3-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that Food dominates your life?

A threshold of 2 or more “Yes” answers on the SCOFF questionnaire has a pooled sensitivity of 84% for all 3 disorders combined and a pooled specificity of 80%.4

What should you do routinely? For adolescents and adults who have no indication of an eating disorder, there is no proven value to screening. Measuring height and weight, calculating body mass index, and continuing to track these measurements for all patients over time is considered standard practice. For those patients who have signs or symptoms that could be due to an eating disorder, administer the SCOFF tool; further assess those with 2 or more positive responses, and refer for diagnosis and treatment those suspected of having an eating disorder.

1. USPSTF. Screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults. JAMA. 2022;327:1061-1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1806

2. Klein DA, Sylvester JE, Schvey NA. Eating disorders in primary care: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103:22-32.

3. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacy JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: a new screening tool for eating disorders. West J Med. 2000;172:164-165. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.3.164

4. Feltner C, Peat C, Reddy S, et al. Evidence Synthesis No 212: Screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults: an evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Published March 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-review/screening-eating-disorders-adolescents-adults

The US Preventive Services Task Force recently released its findings on screening for eating disorders—including binge eating, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa—in adolescents and adults.1 This is the first time the Task Force has addressed this topic.

For those who have no signs or symptoms of an eating disorder, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening. Signs and symptoms of an eating disorder include rapid changes in weight (gain or loss), delayed puberty, bradycardia, oligomenorrhea, or amenorrhea.1

Screening vs diagnostic work-up. The term screening means looking for the presence of a condition in an asymptomatic person. Those who have signs or symptoms that could be due to an eating disorder should be assessed for these conditions, but this would be classified as diagnostic testing rather than preventive screening.

Relatively uncommon but serious. The estimated lifetime prevalence of anorexia is 1.42% in women and 0.12% in men; for bulimia, 0.46% in women and 0.08% in men; and for binge eating, 1.25% in women and 0.42% in men.1 Those suspected of having an eating disorder need psychological, behavioral, medical, and nutritional care provided by those with expertise in diagnosing and treating these disorders. (A systematic review of treatment options was recently published in American Family Physician.2)

If you suspect an eating disorder … Several tools for the assessment of eating disorders have been described in the literature, including the Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (EDS-PC) tool, but the Task Force identified enough evidence to comment on the accuracy of only one: the SCOFF questionnaire. There is adequate evidence on its accuracy for use in adult women but not in adolescents or males.1

The SCOFF tool, which originated in the United Kingdom, consists of 5 questions3:

- Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry that you have lost Control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than One stone (14 lb) in a 3-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that Food dominates your life?

A threshold of 2 or more “Yes” answers on the SCOFF questionnaire has a pooled sensitivity of 84% for all 3 disorders combined and a pooled specificity of 80%.4

What should you do routinely? For adolescents and adults who have no indication of an eating disorder, there is no proven value to screening. Measuring height and weight, calculating body mass index, and continuing to track these measurements for all patients over time is considered standard practice. For those patients who have signs or symptoms that could be due to an eating disorder, administer the SCOFF tool; further assess those with 2 or more positive responses, and refer for diagnosis and treatment those suspected of having an eating disorder.

The US Preventive Services Task Force recently released its findings on screening for eating disorders—including binge eating, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa—in adolescents and adults.1 This is the first time the Task Force has addressed this topic.

For those who have no signs or symptoms of an eating disorder, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening. Signs and symptoms of an eating disorder include rapid changes in weight (gain or loss), delayed puberty, bradycardia, oligomenorrhea, or amenorrhea.1

Screening vs diagnostic work-up. The term screening means looking for the presence of a condition in an asymptomatic person. Those who have signs or symptoms that could be due to an eating disorder should be assessed for these conditions, but this would be classified as diagnostic testing rather than preventive screening.

Relatively uncommon but serious. The estimated lifetime prevalence of anorexia is 1.42% in women and 0.12% in men; for bulimia, 0.46% in women and 0.08% in men; and for binge eating, 1.25% in women and 0.42% in men.1 Those suspected of having an eating disorder need psychological, behavioral, medical, and nutritional care provided by those with expertise in diagnosing and treating these disorders. (A systematic review of treatment options was recently published in American Family Physician.2)

If you suspect an eating disorder … Several tools for the assessment of eating disorders have been described in the literature, including the Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (EDS-PC) tool, but the Task Force identified enough evidence to comment on the accuracy of only one: the SCOFF questionnaire. There is adequate evidence on its accuracy for use in adult women but not in adolescents or males.1

The SCOFF tool, which originated in the United Kingdom, consists of 5 questions3:

- Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry that you have lost Control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than One stone (14 lb) in a 3-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that Food dominates your life?

A threshold of 2 or more “Yes” answers on the SCOFF questionnaire has a pooled sensitivity of 84% for all 3 disorders combined and a pooled specificity of 80%.4

What should you do routinely? For adolescents and adults who have no indication of an eating disorder, there is no proven value to screening. Measuring height and weight, calculating body mass index, and continuing to track these measurements for all patients over time is considered standard practice. For those patients who have signs or symptoms that could be due to an eating disorder, administer the SCOFF tool; further assess those with 2 or more positive responses, and refer for diagnosis and treatment those suspected of having an eating disorder.

1. USPSTF. Screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults. JAMA. 2022;327:1061-1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1806

2. Klein DA, Sylvester JE, Schvey NA. Eating disorders in primary care: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103:22-32.

3. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacy JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: a new screening tool for eating disorders. West J Med. 2000;172:164-165. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.3.164

4. Feltner C, Peat C, Reddy S, et al. Evidence Synthesis No 212: Screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults: an evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Published March 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-review/screening-eating-disorders-adolescents-adults

1. USPSTF. Screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults. JAMA. 2022;327:1061-1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1806

2. Klein DA, Sylvester JE, Schvey NA. Eating disorders in primary care: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103:22-32.

3. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacy JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: a new screening tool for eating disorders. West J Med. 2000;172:164-165. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.3.164

4. Feltner C, Peat C, Reddy S, et al. Evidence Synthesis No 212: Screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults: an evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Published March 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-review/screening-eating-disorders-adolescents-adults

USPSTF issues draft guidance on statins for primary CVD prevention

On February 22, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) posted draft recommendations on the use of statins as a method of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 This is an update to their 2016 recommendations and reaffirms the guidance published at that time.

What’s recommended. The recommendations have 3 parts and are intended for adults with no evidence or previous diagnosis of CVD.

- Statins should be prescribed for those who meet 3 criteria: (1) are ages 40 through 75 years; (2) have 1 or more CVD risk factors (high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, tobacco use); and (3) have a calculated 10-year risk of a CVD event of 10% or greater. (The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD Risk Calculator, recommended by the USPSTF, can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com/.) This is a “B” recommendation.1

- Selectively offer a statin, based on a discussion of benefits and risks and patient preferences, to those who meet criteria 1 and 2 above but who have a calculated CVD risk of 7.5% to 10%. This is a “C” recommendation.1

- For those ages 76 years and older, there is insufficient evidence to assess benefits and harms of statin use. The USPSTF therefore issued an “I” statement for this group.1

What to prescribe. The USPSTF feels that moderate-intensity statin therapy is a reasonable approach for most people who use statins for primary CVD prevention. This would equate to atorvastatin 10 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, or simvastatin 20 to 40 mg daily.1

A few notes on the evidence. Data from 22 studies were included in the evidence review upon which the recommendations are based. The mean duration of follow-up was 3 years. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 stroke was about 256; to prevent 1 myocardial infarction, 112; and to prevent all CVD events, 78.2

What others recommend. These recommendations are mostly consistent with those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, except that those organizations recommend initiating statins in all those with a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 7.5%.1

1. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Published February 22, 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

2. Chou R, Cantor A, Dana T, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 219. AHRQ Publication No. 22-05291-EF-1. Published February 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

On February 22, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) posted draft recommendations on the use of statins as a method of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 This is an update to their 2016 recommendations and reaffirms the guidance published at that time.

What’s recommended. The recommendations have 3 parts and are intended for adults with no evidence or previous diagnosis of CVD.

- Statins should be prescribed for those who meet 3 criteria: (1) are ages 40 through 75 years; (2) have 1 or more CVD risk factors (high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, tobacco use); and (3) have a calculated 10-year risk of a CVD event of 10% or greater. (The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD Risk Calculator, recommended by the USPSTF, can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com/.) This is a “B” recommendation.1

- Selectively offer a statin, based on a discussion of benefits and risks and patient preferences, to those who meet criteria 1 and 2 above but who have a calculated CVD risk of 7.5% to 10%. This is a “C” recommendation.1

- For those ages 76 years and older, there is insufficient evidence to assess benefits and harms of statin use. The USPSTF therefore issued an “I” statement for this group.1

What to prescribe. The USPSTF feels that moderate-intensity statin therapy is a reasonable approach for most people who use statins for primary CVD prevention. This would equate to atorvastatin 10 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, or simvastatin 20 to 40 mg daily.1

A few notes on the evidence. Data from 22 studies were included in the evidence review upon which the recommendations are based. The mean duration of follow-up was 3 years. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 stroke was about 256; to prevent 1 myocardial infarction, 112; and to prevent all CVD events, 78.2

What others recommend. These recommendations are mostly consistent with those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, except that those organizations recommend initiating statins in all those with a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 7.5%.1

On February 22, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) posted draft recommendations on the use of statins as a method of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 This is an update to their 2016 recommendations and reaffirms the guidance published at that time.

What’s recommended. The recommendations have 3 parts and are intended for adults with no evidence or previous diagnosis of CVD.

- Statins should be prescribed for those who meet 3 criteria: (1) are ages 40 through 75 years; (2) have 1 or more CVD risk factors (high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, tobacco use); and (3) have a calculated 10-year risk of a CVD event of 10% or greater. (The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD Risk Calculator, recommended by the USPSTF, can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com/.) This is a “B” recommendation.1

- Selectively offer a statin, based on a discussion of benefits and risks and patient preferences, to those who meet criteria 1 and 2 above but who have a calculated CVD risk of 7.5% to 10%. This is a “C” recommendation.1

- For those ages 76 years and older, there is insufficient evidence to assess benefits and harms of statin use. The USPSTF therefore issued an “I” statement for this group.1

What to prescribe. The USPSTF feels that moderate-intensity statin therapy is a reasonable approach for most people who use statins for primary CVD prevention. This would equate to atorvastatin 10 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, or simvastatin 20 to 40 mg daily.1

A few notes on the evidence. Data from 22 studies were included in the evidence review upon which the recommendations are based. The mean duration of follow-up was 3 years. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 stroke was about 256; to prevent 1 myocardial infarction, 112; and to prevent all CVD events, 78.2

What others recommend. These recommendations are mostly consistent with those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, except that those organizations recommend initiating statins in all those with a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 7.5%.1

1. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Published February 22, 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

2. Chou R, Cantor A, Dana T, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 219. AHRQ Publication No. 22-05291-EF-1. Published February 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

1. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Published February 22, 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

2. Chou R, Cantor A, Dana T, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 219. AHRQ Publication No. 22-05291-EF-1. Published February 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

Vaccine update: The latest recommendations from ACIP

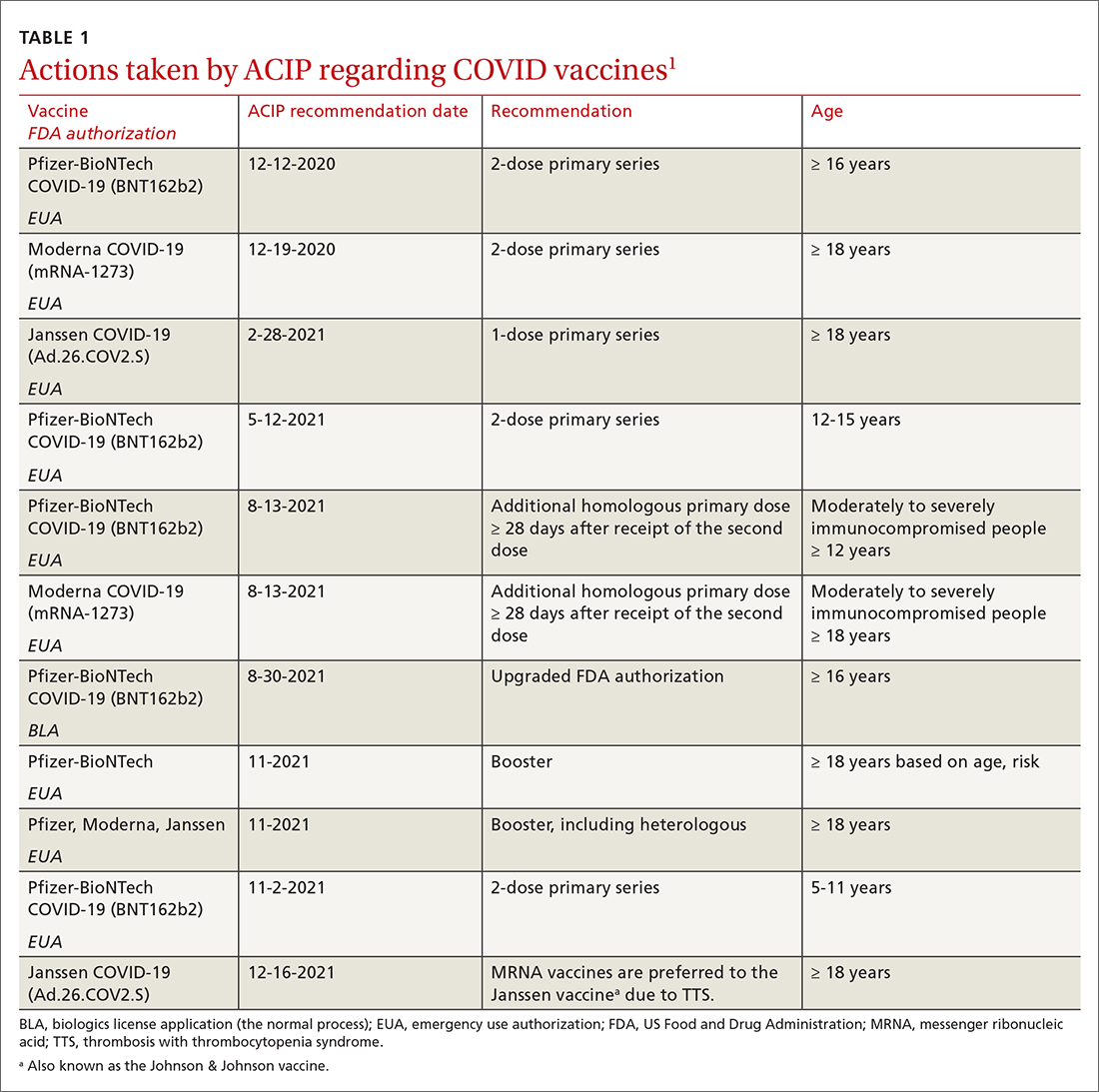

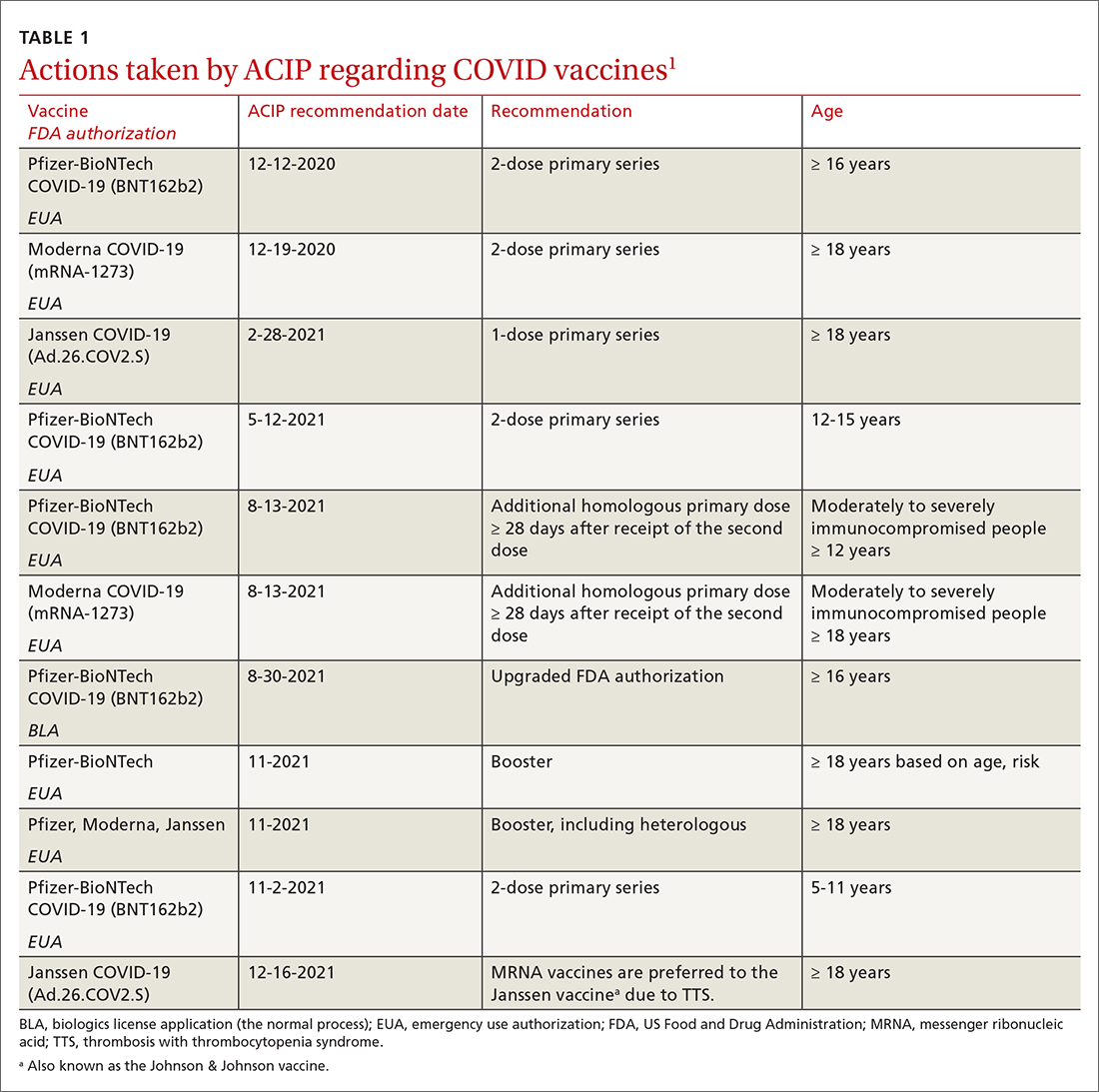

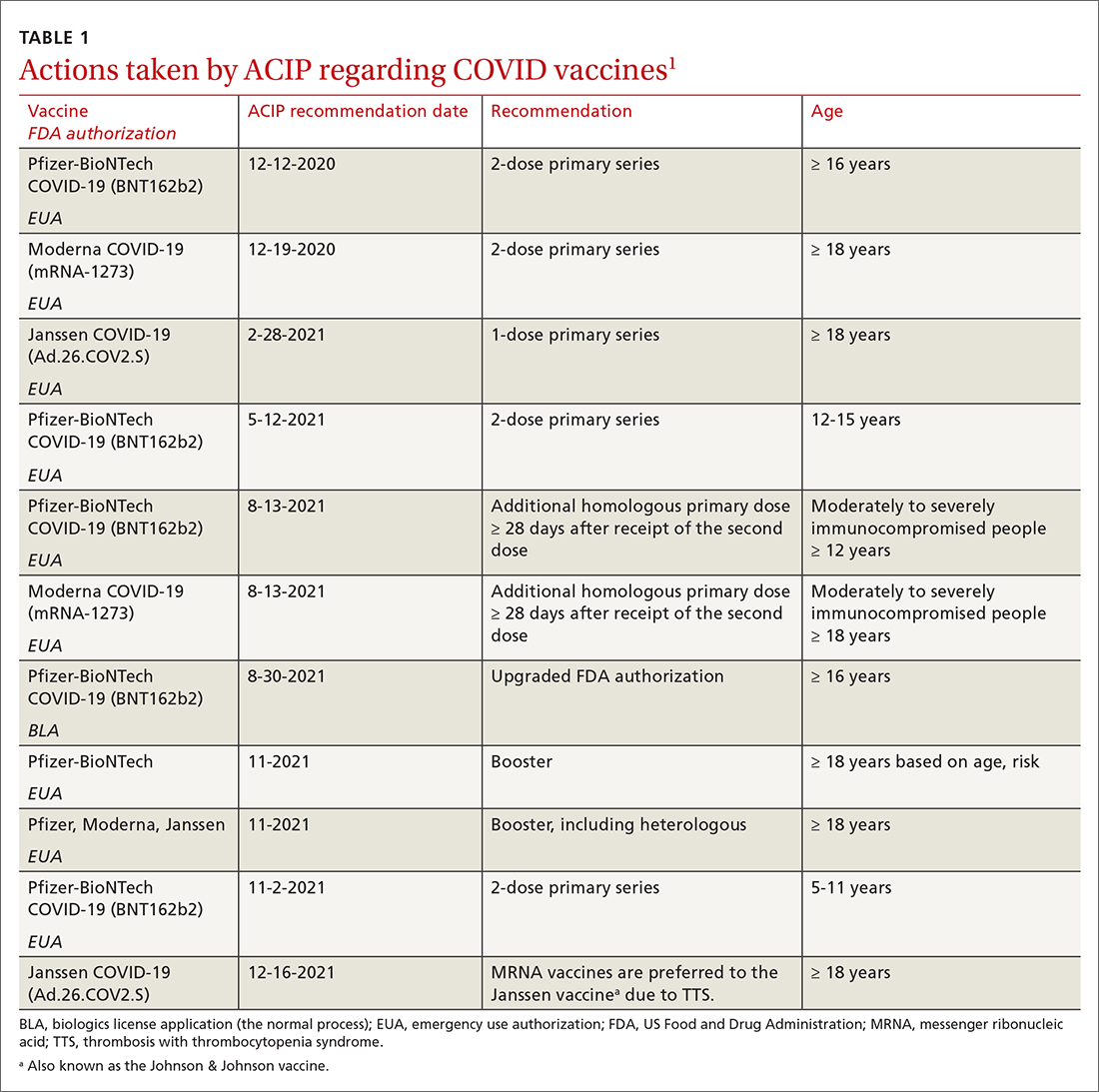

In a typical year, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has three 1.5- to 2-day meetings to make recommendations for the use of new and existing vaccines in the US population. However, 2021 was not a typical year. Last year, ACIP held 17 meetings for a total of 127 hours. Most of these were related to vaccines to prevent COVID-19. There are now 3 COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use in the United States: the 2-dose mRNA-based Pfizer-BioNTech/Comirnaty and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines and the single-dose adenovirus, vector-based Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 vaccine.

TABLE 11 includes the actions taken by the ACIP from late 2020 through 2021 related to COVID-19 vaccines. All of these recommendations except 1 occurred after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the product using an emergency use authorization (EUA). The exception is the recommendation for use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) for those ages 16 years and older, which was approved under the normal process 8 months after widespread use under an EUA.

Hepatitis B vaccine now for all nonimmune adults up through 59 years

Since the introduction of hepatitis B (HepB) vaccines in 1980, the incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections in the United States has been reduced dramatically; there were an estimated 287,000 cases in 19852 and 19,200 in 2014.3 However, the incidence among adults has not declined in recent years and among someage groups has actually increased. Among those ages 40 to 49 years, the rate went from 1.9 per 100,000 in 20114 to 2.7 per 100,000 population in 2019.5 In those ages 50 to 59, there was an increase from 1.1 to 1.6 per 100,000 population over the same period of time.4,5

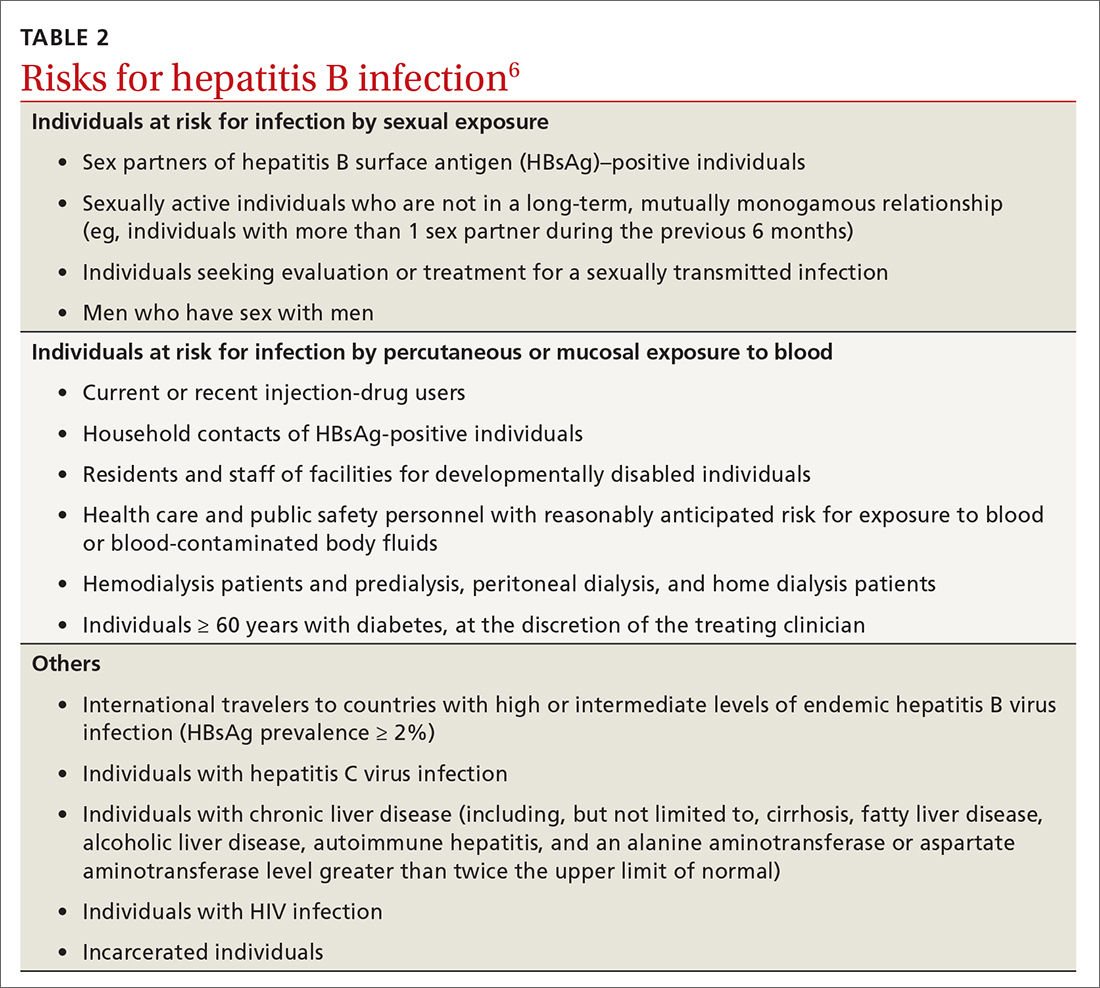

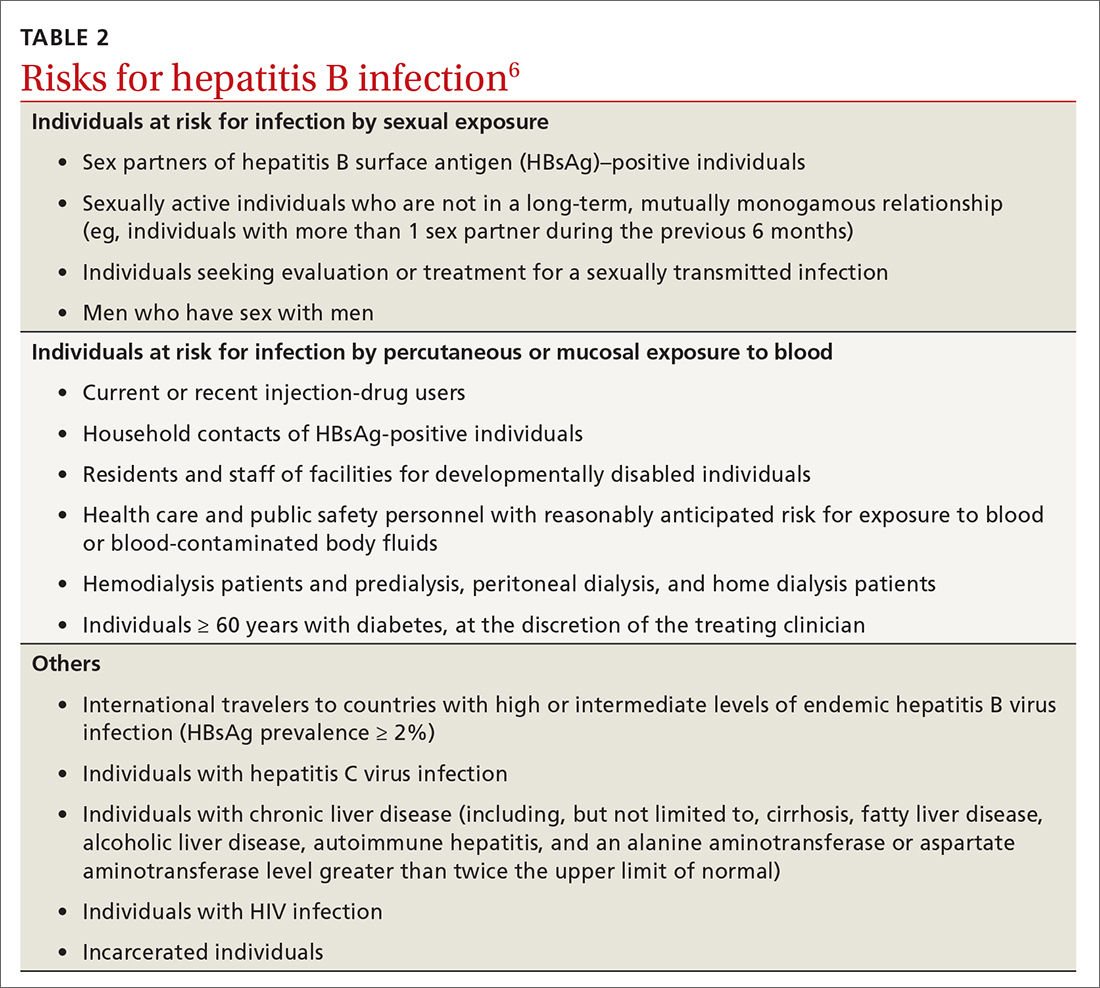

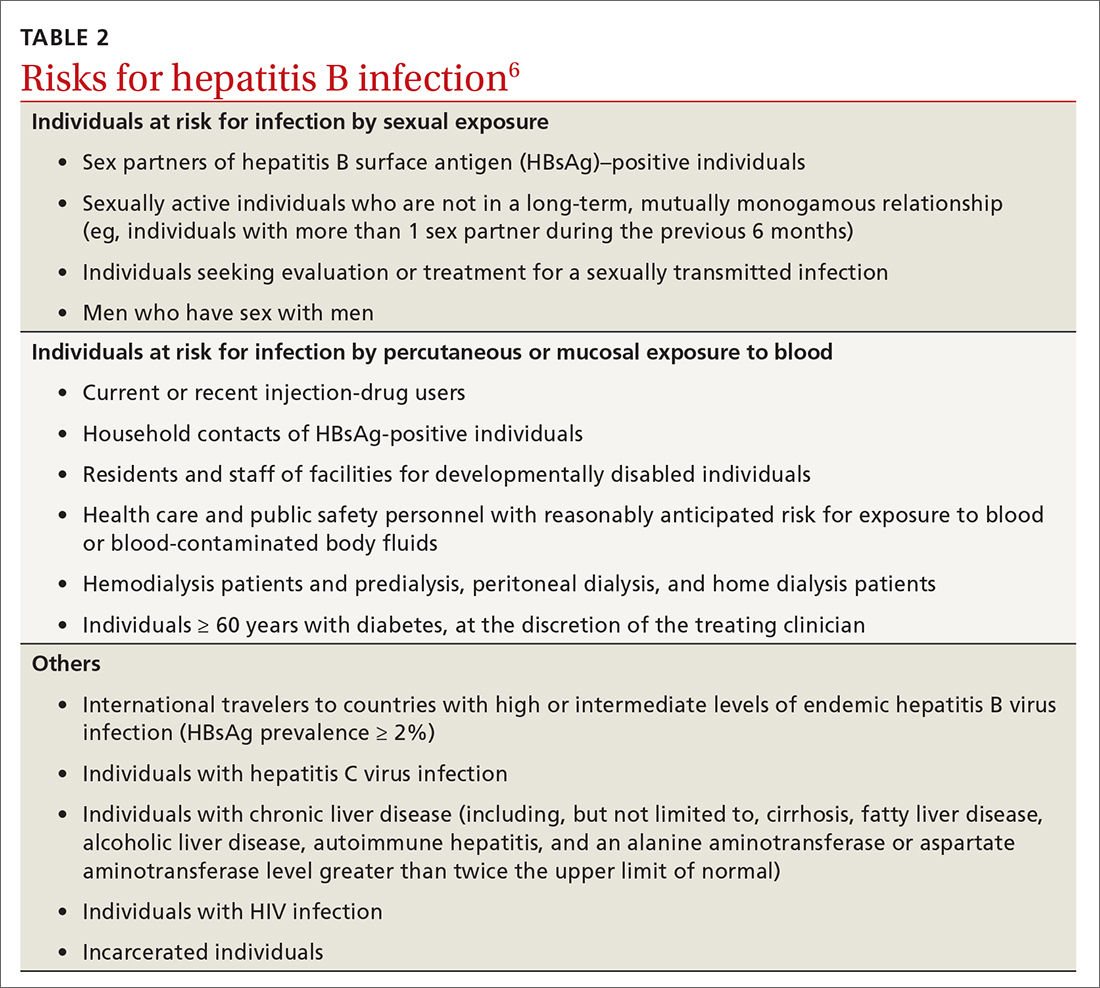

Recommendations for using HepB vaccine in adults have been based on risk that involves individual behavior, occupation, and medical conditions (TABLE 26). The presence of these risk factors is often unknown to medical professionals, who rarely ask about or document them. And patients can be reluctant to disclose them for fear of being stigmatized. The consequence has been a low rate of vaccination in at-risk adults.

At its November 2021 meeting, ACIP accepted the advice of the Hepatitis Work Group to move to a universal adult recommendation through age 59.7 ACIP believed that the incidence of acute infection in those ages 60 and older was too low to merit a universal recommendation. The new recommendation states that

Multiple HepB vaccine products are available for adults. Two are recombinant-based and require 3 doses: Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck). One is recombinant based and requires only 2 doses: Heplisav-B (Dynavax Technologies). A new product recently approved by the FDA, PREHEVBRIO (VBI Vaccines), is another recombinant 3-dose option that the ACIP will consider early in 2022. HepB and HepA vaccines can also be co-administered with Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline).

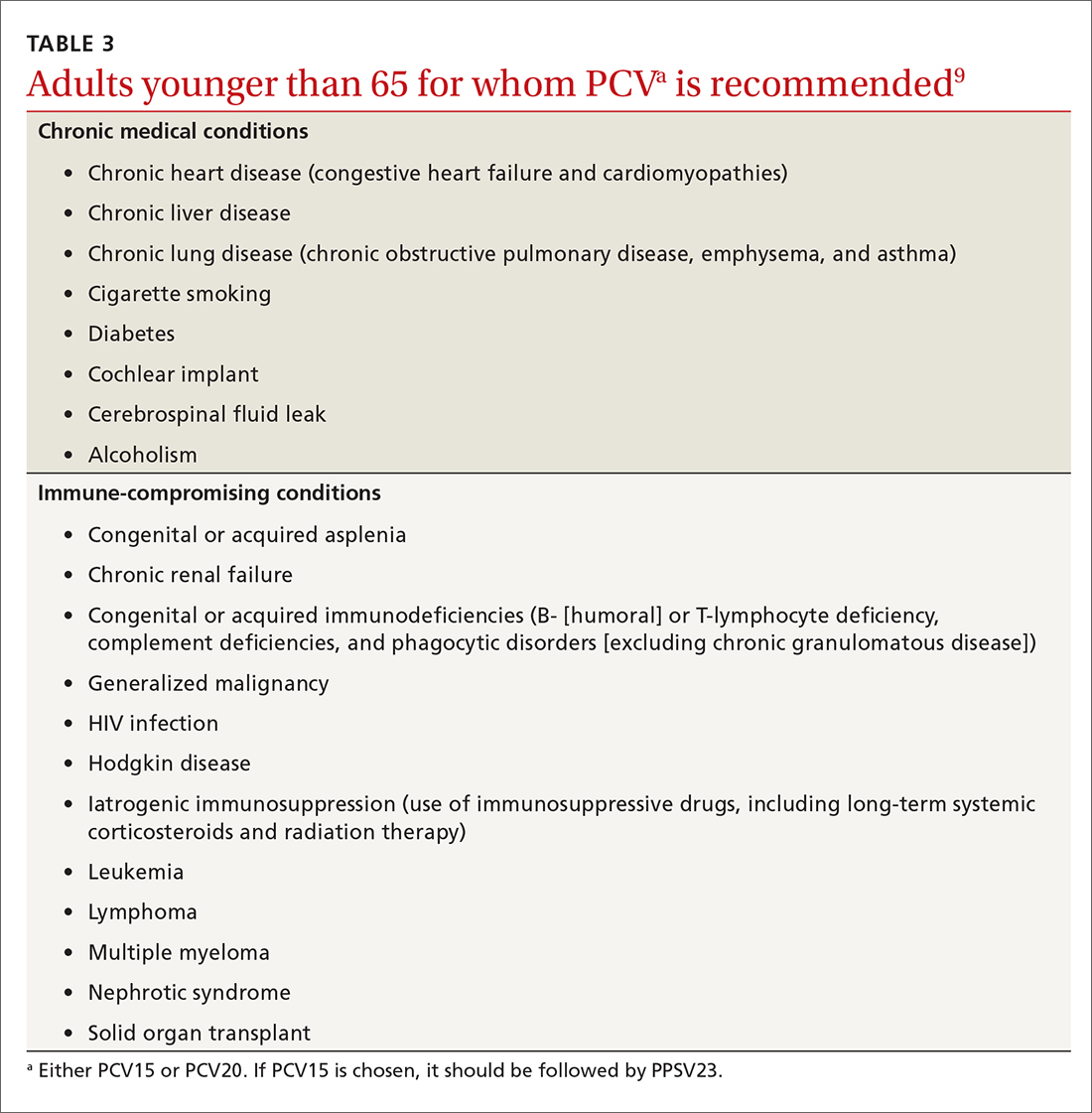

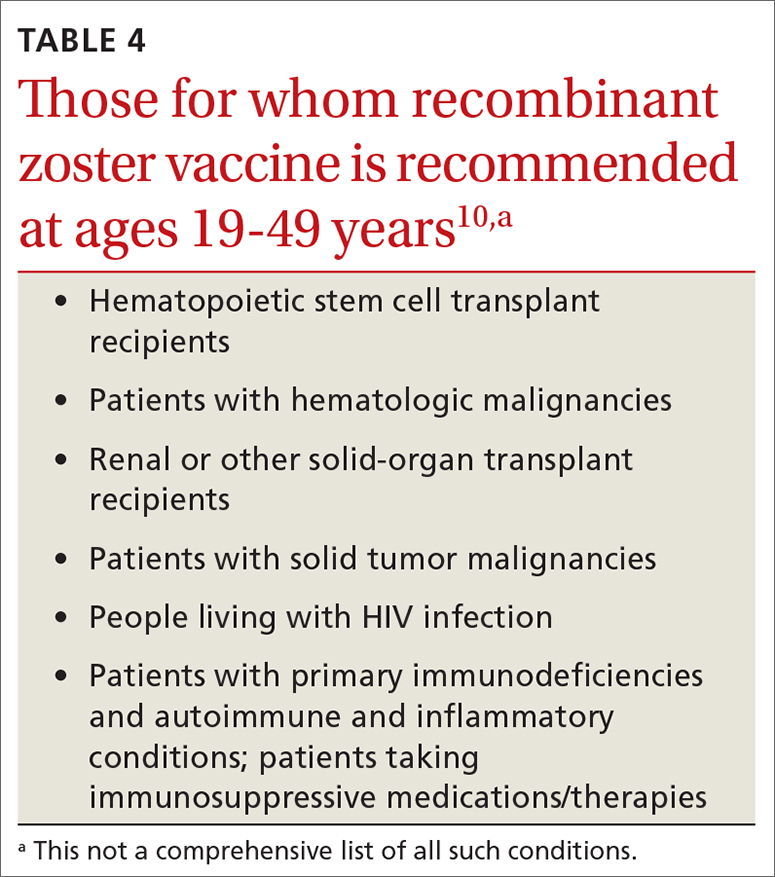

Pneumococcal vaccines: New PCV vaccines alter prescribing choices