User login

Unassigned, Undocumented Patients Take a Toll on Healthcare and Hospitalists

When a patient must remain in the acute care hospital setting—despite being well enough to transition to a lower level of care, costs continue to mount as the patient receives care at the most expensive level.

“But policymakers must understand that reducing support for essential hospitals might save dollars in the short term but ultimately threatens access to care and creates greater costs in the long run,” says Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy for America’s Essential Hospitals in Washington, D.C. The group represents more than 250 essential hospitals, which fill a safety net role and provide communitywide services, such as trauma, neonatal intensive care, and disaster response.

“Our hospitals, which already operate at a loss on average, cannot continue to sustain federal and state funding cuts,” Dr. Feldpush says. “Access to care for vulnerable patients and entire communities will suffer if we continue to chip away at crucial sources of support, such as Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital funding and payment for outpatient services.”

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) makes many changes to the healthcare system that are designed to improve the quality, value of, and access to healthcare services.

“While many are good in theory, they have faced challenges in practice,” Dr. Feldpush says.

For example, the law’s authors included deep cuts to Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, which support hospitals that provide a large volume of uncompensated care. They made these cuts with the assumption that Medicare expansion and the ACA health insurance marketplace would significantly increase coverage, lessening the need for DSH payments. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to give states the option of expanding Medicaid has resulted in expansion in only about half of the states, however.

“But the DSH cuts remain, meaning our hospitals are getting significantly less support for the same or more uncompensated care,” Dr. Feldpush says.

Likewise, the ACA put into place many quality incentive programs for Medicare, including those designed to reduce preventable readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions and to encourage more value-based purchasing.

“The goals are obviously good ones, but the quality measures used to calculate incentive payments or penalties fail to account for the sociodemographic challenges our patients face—and that our hospitals can’t control,” she says. “So, these programs disproportionately penalize our hospitals, which, in turn, creates a vicious circle that reduces the funding they need to make improvements.”

Access to equitable healthcare for low-income, uninsured, and other vulnerable patients is a national problem, Dr. Feldpush continues. But the severity of the problem can vary by community and region—in states that have chosen not to expand their Medicaid programs, for example, or in economically depressed areas. TH

When a patient must remain in the acute care hospital setting—despite being well enough to transition to a lower level of care, costs continue to mount as the patient receives care at the most expensive level.

“But policymakers must understand that reducing support for essential hospitals might save dollars in the short term but ultimately threatens access to care and creates greater costs in the long run,” says Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy for America’s Essential Hospitals in Washington, D.C. The group represents more than 250 essential hospitals, which fill a safety net role and provide communitywide services, such as trauma, neonatal intensive care, and disaster response.

“Our hospitals, which already operate at a loss on average, cannot continue to sustain federal and state funding cuts,” Dr. Feldpush says. “Access to care for vulnerable patients and entire communities will suffer if we continue to chip away at crucial sources of support, such as Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital funding and payment for outpatient services.”

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) makes many changes to the healthcare system that are designed to improve the quality, value of, and access to healthcare services.

“While many are good in theory, they have faced challenges in practice,” Dr. Feldpush says.

For example, the law’s authors included deep cuts to Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, which support hospitals that provide a large volume of uncompensated care. They made these cuts with the assumption that Medicare expansion and the ACA health insurance marketplace would significantly increase coverage, lessening the need for DSH payments. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to give states the option of expanding Medicaid has resulted in expansion in only about half of the states, however.

“But the DSH cuts remain, meaning our hospitals are getting significantly less support for the same or more uncompensated care,” Dr. Feldpush says.

Likewise, the ACA put into place many quality incentive programs for Medicare, including those designed to reduce preventable readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions and to encourage more value-based purchasing.

“The goals are obviously good ones, but the quality measures used to calculate incentive payments or penalties fail to account for the sociodemographic challenges our patients face—and that our hospitals can’t control,” she says. “So, these programs disproportionately penalize our hospitals, which, in turn, creates a vicious circle that reduces the funding they need to make improvements.”

Access to equitable healthcare for low-income, uninsured, and other vulnerable patients is a national problem, Dr. Feldpush continues. But the severity of the problem can vary by community and region—in states that have chosen not to expand their Medicaid programs, for example, or in economically depressed areas. TH

When a patient must remain in the acute care hospital setting—despite being well enough to transition to a lower level of care, costs continue to mount as the patient receives care at the most expensive level.

“But policymakers must understand that reducing support for essential hospitals might save dollars in the short term but ultimately threatens access to care and creates greater costs in the long run,” says Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy for America’s Essential Hospitals in Washington, D.C. The group represents more than 250 essential hospitals, which fill a safety net role and provide communitywide services, such as trauma, neonatal intensive care, and disaster response.

“Our hospitals, which already operate at a loss on average, cannot continue to sustain federal and state funding cuts,” Dr. Feldpush says. “Access to care for vulnerable patients and entire communities will suffer if we continue to chip away at crucial sources of support, such as Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital funding and payment for outpatient services.”

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) makes many changes to the healthcare system that are designed to improve the quality, value of, and access to healthcare services.

“While many are good in theory, they have faced challenges in practice,” Dr. Feldpush says.

For example, the law’s authors included deep cuts to Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, which support hospitals that provide a large volume of uncompensated care. They made these cuts with the assumption that Medicare expansion and the ACA health insurance marketplace would significantly increase coverage, lessening the need for DSH payments. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to give states the option of expanding Medicaid has resulted in expansion in only about half of the states, however.

“But the DSH cuts remain, meaning our hospitals are getting significantly less support for the same or more uncompensated care,” Dr. Feldpush says.

Likewise, the ACA put into place many quality incentive programs for Medicare, including those designed to reduce preventable readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions and to encourage more value-based purchasing.

“The goals are obviously good ones, but the quality measures used to calculate incentive payments or penalties fail to account for the sociodemographic challenges our patients face—and that our hospitals can’t control,” she says. “So, these programs disproportionately penalize our hospitals, which, in turn, creates a vicious circle that reduces the funding they need to make improvements.”

Access to equitable healthcare for low-income, uninsured, and other vulnerable patients is a national problem, Dr. Feldpush continues. But the severity of the problem can vary by community and region—in states that have chosen not to expand their Medicaid programs, for example, or in economically depressed areas. TH

Health spending growth soars after years of low growth

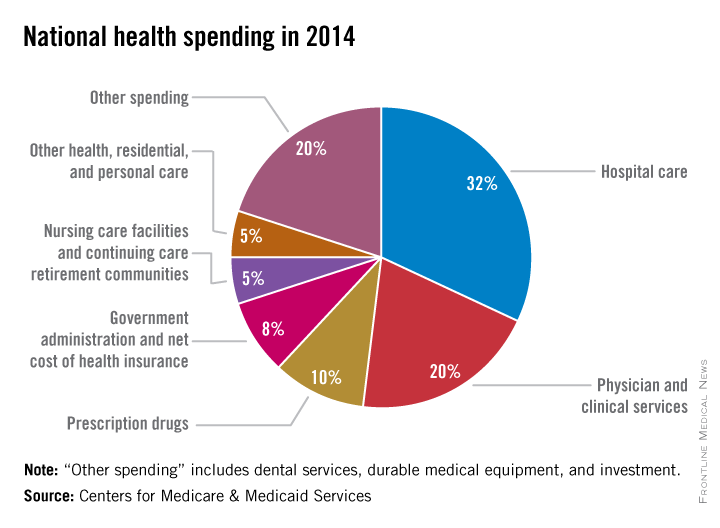

Five years of low growth in national health spending expenditures reversed substantially in 2014, driven by new Affordable Care Act coverage mandates and higher prescription drug spending, largely for new hepatitis C treatments.

U.S. health spending climbed to $3 trillion and grew by 5.3%, as compared with 2013 when growth was 2.9%. Per capita spending in 2014 was up 4.5% to $9,523 from $9,115 in 2013, according to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary (Health Affairs. 2015 Dec 2 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1194).

Anne B. Martin, an economist with actuary’s office, said the 2014 numbers reversed several years of historically low spending growth that tracked with the sluggish economy. She attributed the uptick in growth to the ACA’s access mandates as well as prescription drug purchases, namely those for HCV, which added $11.3 billion in new spending.

“We can’t necessarily say that the [low-growth] cycle has been broken, but this 2014 phenomenon is driven primarily by the ACA expansion and the one-time impact of bringing the new hepatitis C drug into the 2014 mix,” Ms. Martin said.

Between 2013 and 2014, 8.7 million additional patients were enrolled in public and private health insurance, bringing the total insured share of the population from 86% to 88.8%, the highest coverage rate since 1987, according to Ms. Martin and her colleagues.

The growth rate for private health insurance spending went from 1.6% in 2013 to 4.4% in 2014. The $991 billion spent reflected the addition of 2.2 million newly insured patients, and higher rates of spending on medications, clinical services, and inpatient care, compared with 2013.

Federal government spending grew the fastest in 2014 at 11.7%, an 8.2% faster growth rate than in 2013.

In 2014, 28% of all health care purchases were made by the federal government, up from 26% in 2013.

Medicaid-specific spending totaled $495.8 billion, an 11% growth rate in 2014, up from 5.9% in 2013, reflecting the addition of 7.7 million Medicaid enrollees, various increases in prescription drug rebates, and updated provider fees.

Medicare spending jumped to 5.5%, up from 3.0% in 2013, largely due to prescription drugs, although Micah Hartman, a statistician in the Office of the Actuary, said that the per-enrollee spending rate was 2.4% in 2014, up from –0.2% in 2013, which was due to physician and clinical services, higher administrative costs, as well as the net cost of insurance, including fees and administrative costs.

Mr. Hartman singled out Medicare Advantage as a key contributor, noting that the 9.7% increase in growth for that program was from ACA-stipulated fees.

Overall, pharmaceutical spending was $297.7 billion in 2014, according to the report, attributable to novel HCV drugs, other new treatments, fewer-than-normal patent expirations and, in some cases, a doubling of the costs for certain brand-name drugs. The overall 2014 pharmaceutical expenditure growth rate was 12.2%, compared with 2.4% in 2013, the largest differential since 2002.

Physician and clinical services in 2014 went from a growth rate of 2.5% to 4.6%, with total spending at $603.7 billion. Hospital spending last year was $971.8 billion, with a spending growth rate of 4.1%, compared with 3.5% in 2013.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

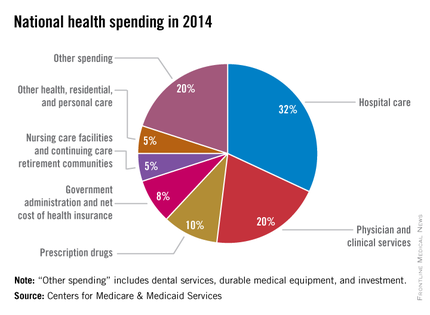

Five years of low growth in national health spending expenditures reversed substantially in 2014, driven by new Affordable Care Act coverage mandates and higher prescription drug spending, largely for new hepatitis C treatments.

U.S. health spending climbed to $3 trillion and grew by 5.3%, as compared with 2013 when growth was 2.9%. Per capita spending in 2014 was up 4.5% to $9,523 from $9,115 in 2013, according to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary (Health Affairs. 2015 Dec 2 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1194).

Anne B. Martin, an economist with actuary’s office, said the 2014 numbers reversed several years of historically low spending growth that tracked with the sluggish economy. She attributed the uptick in growth to the ACA’s access mandates as well as prescription drug purchases, namely those for HCV, which added $11.3 billion in new spending.

“We can’t necessarily say that the [low-growth] cycle has been broken, but this 2014 phenomenon is driven primarily by the ACA expansion and the one-time impact of bringing the new hepatitis C drug into the 2014 mix,” Ms. Martin said.

Between 2013 and 2014, 8.7 million additional patients were enrolled in public and private health insurance, bringing the total insured share of the population from 86% to 88.8%, the highest coverage rate since 1987, according to Ms. Martin and her colleagues.

The growth rate for private health insurance spending went from 1.6% in 2013 to 4.4% in 2014. The $991 billion spent reflected the addition of 2.2 million newly insured patients, and higher rates of spending on medications, clinical services, and inpatient care, compared with 2013.

Federal government spending grew the fastest in 2014 at 11.7%, an 8.2% faster growth rate than in 2013.

In 2014, 28% of all health care purchases were made by the federal government, up from 26% in 2013.

Medicaid-specific spending totaled $495.8 billion, an 11% growth rate in 2014, up from 5.9% in 2013, reflecting the addition of 7.7 million Medicaid enrollees, various increases in prescription drug rebates, and updated provider fees.

Medicare spending jumped to 5.5%, up from 3.0% in 2013, largely due to prescription drugs, although Micah Hartman, a statistician in the Office of the Actuary, said that the per-enrollee spending rate was 2.4% in 2014, up from –0.2% in 2013, which was due to physician and clinical services, higher administrative costs, as well as the net cost of insurance, including fees and administrative costs.

Mr. Hartman singled out Medicare Advantage as a key contributor, noting that the 9.7% increase in growth for that program was from ACA-stipulated fees.

Overall, pharmaceutical spending was $297.7 billion in 2014, according to the report, attributable to novel HCV drugs, other new treatments, fewer-than-normal patent expirations and, in some cases, a doubling of the costs for certain brand-name drugs. The overall 2014 pharmaceutical expenditure growth rate was 12.2%, compared with 2.4% in 2013, the largest differential since 2002.

Physician and clinical services in 2014 went from a growth rate of 2.5% to 4.6%, with total spending at $603.7 billion. Hospital spending last year was $971.8 billion, with a spending growth rate of 4.1%, compared with 3.5% in 2013.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

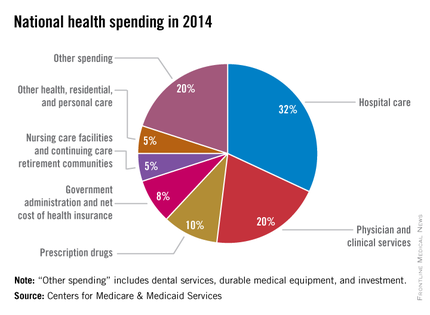

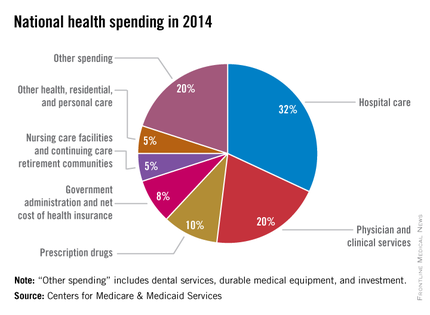

Five years of low growth in national health spending expenditures reversed substantially in 2014, driven by new Affordable Care Act coverage mandates and higher prescription drug spending, largely for new hepatitis C treatments.

U.S. health spending climbed to $3 trillion and grew by 5.3%, as compared with 2013 when growth was 2.9%. Per capita spending in 2014 was up 4.5% to $9,523 from $9,115 in 2013, according to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary (Health Affairs. 2015 Dec 2 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1194).

Anne B. Martin, an economist with actuary’s office, said the 2014 numbers reversed several years of historically low spending growth that tracked with the sluggish economy. She attributed the uptick in growth to the ACA’s access mandates as well as prescription drug purchases, namely those for HCV, which added $11.3 billion in new spending.

“We can’t necessarily say that the [low-growth] cycle has been broken, but this 2014 phenomenon is driven primarily by the ACA expansion and the one-time impact of bringing the new hepatitis C drug into the 2014 mix,” Ms. Martin said.

Between 2013 and 2014, 8.7 million additional patients were enrolled in public and private health insurance, bringing the total insured share of the population from 86% to 88.8%, the highest coverage rate since 1987, according to Ms. Martin and her colleagues.

The growth rate for private health insurance spending went from 1.6% in 2013 to 4.4% in 2014. The $991 billion spent reflected the addition of 2.2 million newly insured patients, and higher rates of spending on medications, clinical services, and inpatient care, compared with 2013.

Federal government spending grew the fastest in 2014 at 11.7%, an 8.2% faster growth rate than in 2013.

In 2014, 28% of all health care purchases were made by the federal government, up from 26% in 2013.

Medicaid-specific spending totaled $495.8 billion, an 11% growth rate in 2014, up from 5.9% in 2013, reflecting the addition of 7.7 million Medicaid enrollees, various increases in prescription drug rebates, and updated provider fees.

Medicare spending jumped to 5.5%, up from 3.0% in 2013, largely due to prescription drugs, although Micah Hartman, a statistician in the Office of the Actuary, said that the per-enrollee spending rate was 2.4% in 2014, up from –0.2% in 2013, which was due to physician and clinical services, higher administrative costs, as well as the net cost of insurance, including fees and administrative costs.

Mr. Hartman singled out Medicare Advantage as a key contributor, noting that the 9.7% increase in growth for that program was from ACA-stipulated fees.

Overall, pharmaceutical spending was $297.7 billion in 2014, according to the report, attributable to novel HCV drugs, other new treatments, fewer-than-normal patent expirations and, in some cases, a doubling of the costs for certain brand-name drugs. The overall 2014 pharmaceutical expenditure growth rate was 12.2%, compared with 2.4% in 2013, the largest differential since 2002.

Physician and clinical services in 2014 went from a growth rate of 2.5% to 4.6%, with total spending at $603.7 billion. Hospital spending last year was $971.8 billion, with a spending growth rate of 4.1%, compared with 3.5% in 2013.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM THE JOURNAL HEALTH AFFAIRS

After 3 years of decline, hospital injury rates plateau, report finds

The rate of avoidable complications affecting patients in hospitals leveled off in 2014 after 3 years of declines, according to a federal report released Dec. 1.

Hospitals have averted many types of injuries where clear preventive steps have been identified, but they still struggle to avert complications with broader causes and less clear-cut solutions, government and hospital officials said.

There were at least 4 million infections and other potentially avoidable injuries in hospitals last year, the study estimated. That translates to about 12 of every 100 hospital stays. Among the most common complications that were measured – each occurring a quarter million times or more – were bed sores, falls, bad reactions to drugs used to treat diabetes, and kidney damage that develops after contrast dyes are injected through catheters to help radiologists take images of blood vessels.

The frequency of hospital complications last year was 17% lower than in 2010 but the same as in 2013, indicating that some patient safety improvements made by hospitals and the government are sticking. But the lack of improvement raised concerns that it is becoming harder for hospitals to further reduce the chances that a patient may be harmed during a visit.

“We are still trying to understand all the factors involved, but I think the improvements we saw from 2010 to 2013 were very likely the low-hanging fruit, the easy problems to solve,” said Dr. Richard Kronick, director of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which conducted the study.

The Obama administration has been focusing on lowering the rates of medical infections and injuries as it tracks a slew of patient safety initiatives created by the Affordable Care Act. Those include Medicare penalties for poor-performing hospitals, wider use of electronic records to help track patient care and prevent mistakes, and grants to collaborations of medical providers formed to improve the quality of patient care and identify the best ways of addressing each type of problem.

The AHRQ report calculated national rates for 27 specific complications by extrapolating from 30,000 medical cases that officials examined. Decreases in infections, medicine reactions, and other complications since 2010 have resulted in 2.1 million fewer incidents of harm, 87,000 fewer deaths, and $20 billion in health care savings, the report concluded.

“Those are real people that are not dying, getting infections or other adverse events in the hospital,” said Dr. Patrick Conway, chief medical officer for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Some of the most significant progress was made in lowering the number of infections from central lines inserted into veins – down 72% from 2010. Medical researchers have proven that these infections can be virtually eliminated if doctors and nurses follow a clear set of procedures.

Infections from urinary catheters decreased by 38% and surgical site infections dropped by 18%. In all three cases, the reductions exceeded the goals set by the administration. Dr. Conway noted that hospitals had a financial motivation to cut these infections as they are used to determine whether hospitals get Medicare bonuses and penalties each year.

However, hospitals have not made headway in trimming the numbers of falls or pneumonia cases in patients breathing through mechanical ventilators, the report found. And the rates of adverse drug reactions and complications during childbirth were higher than what the administration estimated they should be for 2014.

Dr. Conway said that complications are difficult to address because they involve tradeoffs that can cause other problems. For instance, he said, hospitals have to balance efforts to reduce falls with the need to help unstable patients improve their ability to walk. “We’ve got to work with providers to figure out what’s the sweet spot that can keep mobilization occurring but decrease the rate of falls,” he said.

Even though overall complication rates were flat, the report found that some types of injuries became less common in 2014. One was the number of blood clots that form after surgery and travel to the lung; those rates dropped by 30% in a year.

Maulik Joshi, an executive at the American Hospital Association, predicted that complications will become even rarer in future years. “Hospitals are working on projects that are just not reflected in these data points,” he said.

But a few conditions became more prevalent in 2014. Infections from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus increased by 55% to an estimated 17,000 incidents last year. The number of times a catheter punctured a femoral artery during an angiography increased by 25% to 74,000, the report estimated.

“We think we addressed a lot of the areas where there was a strong evidence base on how to improve patient safety,” Dr. Conway said. “We’ll now have to tackle that next wave that has multiple causes.”

The rate of avoidable complications affecting patients in hospitals leveled off in 2014 after 3 years of declines, according to a federal report released Dec. 1.

Hospitals have averted many types of injuries where clear preventive steps have been identified, but they still struggle to avert complications with broader causes and less clear-cut solutions, government and hospital officials said.

There were at least 4 million infections and other potentially avoidable injuries in hospitals last year, the study estimated. That translates to about 12 of every 100 hospital stays. Among the most common complications that were measured – each occurring a quarter million times or more – were bed sores, falls, bad reactions to drugs used to treat diabetes, and kidney damage that develops after contrast dyes are injected through catheters to help radiologists take images of blood vessels.

The frequency of hospital complications last year was 17% lower than in 2010 but the same as in 2013, indicating that some patient safety improvements made by hospitals and the government are sticking. But the lack of improvement raised concerns that it is becoming harder for hospitals to further reduce the chances that a patient may be harmed during a visit.

“We are still trying to understand all the factors involved, but I think the improvements we saw from 2010 to 2013 were very likely the low-hanging fruit, the easy problems to solve,” said Dr. Richard Kronick, director of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which conducted the study.

The Obama administration has been focusing on lowering the rates of medical infections and injuries as it tracks a slew of patient safety initiatives created by the Affordable Care Act. Those include Medicare penalties for poor-performing hospitals, wider use of electronic records to help track patient care and prevent mistakes, and grants to collaborations of medical providers formed to improve the quality of patient care and identify the best ways of addressing each type of problem.

The AHRQ report calculated national rates for 27 specific complications by extrapolating from 30,000 medical cases that officials examined. Decreases in infections, medicine reactions, and other complications since 2010 have resulted in 2.1 million fewer incidents of harm, 87,000 fewer deaths, and $20 billion in health care savings, the report concluded.

“Those are real people that are not dying, getting infections or other adverse events in the hospital,” said Dr. Patrick Conway, chief medical officer for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Some of the most significant progress was made in lowering the number of infections from central lines inserted into veins – down 72% from 2010. Medical researchers have proven that these infections can be virtually eliminated if doctors and nurses follow a clear set of procedures.

Infections from urinary catheters decreased by 38% and surgical site infections dropped by 18%. In all three cases, the reductions exceeded the goals set by the administration. Dr. Conway noted that hospitals had a financial motivation to cut these infections as they are used to determine whether hospitals get Medicare bonuses and penalties each year.

However, hospitals have not made headway in trimming the numbers of falls or pneumonia cases in patients breathing through mechanical ventilators, the report found. And the rates of adverse drug reactions and complications during childbirth were higher than what the administration estimated they should be for 2014.

Dr. Conway said that complications are difficult to address because they involve tradeoffs that can cause other problems. For instance, he said, hospitals have to balance efforts to reduce falls with the need to help unstable patients improve their ability to walk. “We’ve got to work with providers to figure out what’s the sweet spot that can keep mobilization occurring but decrease the rate of falls,” he said.

Even though overall complication rates were flat, the report found that some types of injuries became less common in 2014. One was the number of blood clots that form after surgery and travel to the lung; those rates dropped by 30% in a year.

Maulik Joshi, an executive at the American Hospital Association, predicted that complications will become even rarer in future years. “Hospitals are working on projects that are just not reflected in these data points,” he said.

But a few conditions became more prevalent in 2014. Infections from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus increased by 55% to an estimated 17,000 incidents last year. The number of times a catheter punctured a femoral artery during an angiography increased by 25% to 74,000, the report estimated.

“We think we addressed a lot of the areas where there was a strong evidence base on how to improve patient safety,” Dr. Conway said. “We’ll now have to tackle that next wave that has multiple causes.”

The rate of avoidable complications affecting patients in hospitals leveled off in 2014 after 3 years of declines, according to a federal report released Dec. 1.

Hospitals have averted many types of injuries where clear preventive steps have been identified, but they still struggle to avert complications with broader causes and less clear-cut solutions, government and hospital officials said.

There were at least 4 million infections and other potentially avoidable injuries in hospitals last year, the study estimated. That translates to about 12 of every 100 hospital stays. Among the most common complications that were measured – each occurring a quarter million times or more – were bed sores, falls, bad reactions to drugs used to treat diabetes, and kidney damage that develops after contrast dyes are injected through catheters to help radiologists take images of blood vessels.

The frequency of hospital complications last year was 17% lower than in 2010 but the same as in 2013, indicating that some patient safety improvements made by hospitals and the government are sticking. But the lack of improvement raised concerns that it is becoming harder for hospitals to further reduce the chances that a patient may be harmed during a visit.

“We are still trying to understand all the factors involved, but I think the improvements we saw from 2010 to 2013 were very likely the low-hanging fruit, the easy problems to solve,” said Dr. Richard Kronick, director of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which conducted the study.

The Obama administration has been focusing on lowering the rates of medical infections and injuries as it tracks a slew of patient safety initiatives created by the Affordable Care Act. Those include Medicare penalties for poor-performing hospitals, wider use of electronic records to help track patient care and prevent mistakes, and grants to collaborations of medical providers formed to improve the quality of patient care and identify the best ways of addressing each type of problem.

The AHRQ report calculated national rates for 27 specific complications by extrapolating from 30,000 medical cases that officials examined. Decreases in infections, medicine reactions, and other complications since 2010 have resulted in 2.1 million fewer incidents of harm, 87,000 fewer deaths, and $20 billion in health care savings, the report concluded.

“Those are real people that are not dying, getting infections or other adverse events in the hospital,” said Dr. Patrick Conway, chief medical officer for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Some of the most significant progress was made in lowering the number of infections from central lines inserted into veins – down 72% from 2010. Medical researchers have proven that these infections can be virtually eliminated if doctors and nurses follow a clear set of procedures.

Infections from urinary catheters decreased by 38% and surgical site infections dropped by 18%. In all three cases, the reductions exceeded the goals set by the administration. Dr. Conway noted that hospitals had a financial motivation to cut these infections as they are used to determine whether hospitals get Medicare bonuses and penalties each year.

However, hospitals have not made headway in trimming the numbers of falls or pneumonia cases in patients breathing through mechanical ventilators, the report found. And the rates of adverse drug reactions and complications during childbirth were higher than what the administration estimated they should be for 2014.

Dr. Conway said that complications are difficult to address because they involve tradeoffs that can cause other problems. For instance, he said, hospitals have to balance efforts to reduce falls with the need to help unstable patients improve their ability to walk. “We’ve got to work with providers to figure out what’s the sweet spot that can keep mobilization occurring but decrease the rate of falls,” he said.

Even though overall complication rates were flat, the report found that some types of injuries became less common in 2014. One was the number of blood clots that form after surgery and travel to the lung; those rates dropped by 30% in a year.

Maulik Joshi, an executive at the American Hospital Association, predicted that complications will become even rarer in future years. “Hospitals are working on projects that are just not reflected in these data points,” he said.

But a few conditions became more prevalent in 2014. Infections from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus increased by 55% to an estimated 17,000 incidents last year. The number of times a catheter punctured a femoral artery during an angiography increased by 25% to 74,000, the report estimated.

“We think we addressed a lot of the areas where there was a strong evidence base on how to improve patient safety,” Dr. Conway said. “We’ll now have to tackle that next wave that has multiple causes.”

ICD-10 Flexibility Helps Transition to New Coding Systems, Principles, Payer Policy Requirements

Effective October 1, providers submit claims with ICD-10-CM codes. As they adapt to this new system, physicians, clinical staff, and billers should be relying on feedback from each other to achieve a successful transition. On July 6, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in conjunction with the AMA, issued a letter to the provider community offering ICD-10-CM guidance. The joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities minimizes the anxiety that often accompanies change and clarifies a few key points about claim scrutiny.1

According to the correspondence, “CMS is releasing additional guidance that will allow for flexibility in the claims auditing and quality reporting process as the medical community gains experience using the new ICD-10 code set.”1 The guidance specifies the flexibility that will be used during the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM use.

This “flexibility” is an opportunity and should not be disregarded. Physician practices can effectively use this time to become accustomed to the ICD-10-CM system, correct coding principles, and payer policy requirements. Internal audit and review processes should increase in order to correct or confirm appropriate coding and claim submission.

Valid Codes

Medicare review contractors are instructed “not to deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical review based solely on the specificity of the ICD-10 diagnosis code as long as the physician/practitioner used a valid code from the right family.”2 This “flexibility” will only occur for the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM implementation; the ultimate goal is for providers to assign the correct diagnosis code and the appropriate level of specificity after one year.

The “family code” allowance should not be confused with provision of an incomplete or truncated diagnosis code; these types of codes will always result in claim denial. The ICD-10-CM code presented on the claim form must be carried out to the highest character available for that particular code.

For example, an initial encounter involving an infected peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is reported with ICD-10-CM T80.212A (local infection due to central venous catheter). An individual unfamiliar with ICD-10-CM nomenclature may not realize that the seventh extension character of the code is required to carry the code out to its highest level of specificity. If T880.212 is mistakenly reported because the encounter detail (i.e., initial encounter [A], subsequent encounter [D], or sequela [S]) was not documented or provided to the biller, the payers’ claim edit system will identify this as a truncated or invalid diagnosis and reject the claim. Therefore, the code is required to be complete. The “flexibility” refers to reporting the code that best reflects the documented condition. As long as the reported code comes from the same family of codes and is valid, the claim cannot be denied.

Code Families

Code families are “codes within a category [that] are clinically related and provide differences in capturing specific information on the type of condition.”3 Upon review, Medicare will allow ICD-10-CM codes from the same code family to be reported on the claim without penalty if the most accurate code is not selected.

For example, a patient with COPD with acute exacerbation is admitted to the hospital. During the 12-month “flexibility” period, the claim could include J44.9 (COPD, unspecified) without being considered erroneous. The most appropriate code, however, is J44.1 (COPD with acute exacerbation). During the course of the hospitalization, if the physician determines that the COPD exacerbation was caused by an acute lower respiratory infection, J44.0 (COPD with acute lower respiratory infection) is the best option.

The provider goal for this flexibility period is to identify all of the “unspecified codes” used on their claims, review the documentation, and determine the most appropriate code. The practice staff assigned to this task would then provide feedback to the physicians to enhance their future reporting strategies. Although “unspecified” codes are often reported by default, physicians and staff should attempt to reduce usage of this code type unless the patient’s condition is unable to be further specified or categorized at a given point in time.

For example, it would not be acceptable to report R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) when a more specific diagnosis code can be easily determined by patient history or exam findings (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11).

Affected Claims

As previously stated, “Medicare review contractors will not deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical record review.”3 The review contractors included are as follows:

- Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) process claims submitted by physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare professionals and submit payment to those providers according to Medicare rules and regulations (including identifying and correcting underpayments and overpayments);

- Recovery Auditors (RACs) review claims to identify potential underpayments and overpayments in Medicare fee-for-service, as part of the Recovery Audit Program;

- Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs) perform investigations that are unique and tailored to the specific circumstances and occur only in situations where there is potential fraud and take appropriate corrective actions; and

- Supplemental Medical Review Contractor (SMRCs) conduct nationwide medical review as directed by CMS (including identifying underpayments and overpayments).4

This instruction applies to claims that are typically selected for review due to the ICD-10-CM code used on the claim but does not affect claims that are selected for review for other reasons (e.g. modifier 25 [separately identifiable visit performed on the same day as another procedure or service], unbundling, service-specific current procedural terminology code). If a claim is selected for one of these other reasons and does not meet the corresponding criterion, the service will be denied. This instruction also excludes claims for services that correspond to an existing local coverage determination (LCD) or national coverage determination (NCD).

For example, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is not considered “medically necessary” when reported with R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) and would be denied. EGD requires a more specific diagnosis (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11) per Medicare LCD.

Non-Medicare Payer Considerations

Most payers that are required to convert to ICD-10-CM have also provided some guidance about claim submission. Although most do not address the audit and review process, payers will follow some basic principles:

- Claims submitted with service dates on or after October 1 must use ICD-10-CM codes.

- Claims submitted with service dates prior to October 1 must use ICD-9-CM codes; this includes claims that are initially submitted after October 1 or require correction and resubmission after October 1.

- Physician claims will be held to medical necessity guidelines identified by specific ICD-10-CM codes represented in existing payer policies.

- General equivalence mappings (GEMs) should only be used as a starting point to convert large databases and large code lists from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Many ICD-9-CM codes do not crosswalk directly to an ICD-10-CM code. Physician and staff should continue to use the ICD-10-CM coding books and resources to determine the most accurate code selection.

- “Unspecified” codes are only for use when the information in the medical record is insufficient to assign a more specific code.5,6,7

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10. July 6, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clarifying questions and answers related to the July 6, 2015 CMS/AMA joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Learning Network: Medicare claim review programs. May 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Aetna. Preparation for ICD-10-CM: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Independence Blue Cross. Transition to ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Cigna. Ready, Set, Switch: Know Your ICD-10 Codes. Accessed November 16, 2015.

Effective October 1, providers submit claims with ICD-10-CM codes. As they adapt to this new system, physicians, clinical staff, and billers should be relying on feedback from each other to achieve a successful transition. On July 6, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in conjunction with the AMA, issued a letter to the provider community offering ICD-10-CM guidance. The joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities minimizes the anxiety that often accompanies change and clarifies a few key points about claim scrutiny.1

According to the correspondence, “CMS is releasing additional guidance that will allow for flexibility in the claims auditing and quality reporting process as the medical community gains experience using the new ICD-10 code set.”1 The guidance specifies the flexibility that will be used during the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM use.

This “flexibility” is an opportunity and should not be disregarded. Physician practices can effectively use this time to become accustomed to the ICD-10-CM system, correct coding principles, and payer policy requirements. Internal audit and review processes should increase in order to correct or confirm appropriate coding and claim submission.

Valid Codes

Medicare review contractors are instructed “not to deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical review based solely on the specificity of the ICD-10 diagnosis code as long as the physician/practitioner used a valid code from the right family.”2 This “flexibility” will only occur for the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM implementation; the ultimate goal is for providers to assign the correct diagnosis code and the appropriate level of specificity after one year.

The “family code” allowance should not be confused with provision of an incomplete or truncated diagnosis code; these types of codes will always result in claim denial. The ICD-10-CM code presented on the claim form must be carried out to the highest character available for that particular code.

For example, an initial encounter involving an infected peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is reported with ICD-10-CM T80.212A (local infection due to central venous catheter). An individual unfamiliar with ICD-10-CM nomenclature may not realize that the seventh extension character of the code is required to carry the code out to its highest level of specificity. If T880.212 is mistakenly reported because the encounter detail (i.e., initial encounter [A], subsequent encounter [D], or sequela [S]) was not documented or provided to the biller, the payers’ claim edit system will identify this as a truncated or invalid diagnosis and reject the claim. Therefore, the code is required to be complete. The “flexibility” refers to reporting the code that best reflects the documented condition. As long as the reported code comes from the same family of codes and is valid, the claim cannot be denied.

Code Families

Code families are “codes within a category [that] are clinically related and provide differences in capturing specific information on the type of condition.”3 Upon review, Medicare will allow ICD-10-CM codes from the same code family to be reported on the claim without penalty if the most accurate code is not selected.

For example, a patient with COPD with acute exacerbation is admitted to the hospital. During the 12-month “flexibility” period, the claim could include J44.9 (COPD, unspecified) without being considered erroneous. The most appropriate code, however, is J44.1 (COPD with acute exacerbation). During the course of the hospitalization, if the physician determines that the COPD exacerbation was caused by an acute lower respiratory infection, J44.0 (COPD with acute lower respiratory infection) is the best option.

The provider goal for this flexibility period is to identify all of the “unspecified codes” used on their claims, review the documentation, and determine the most appropriate code. The practice staff assigned to this task would then provide feedback to the physicians to enhance their future reporting strategies. Although “unspecified” codes are often reported by default, physicians and staff should attempt to reduce usage of this code type unless the patient’s condition is unable to be further specified or categorized at a given point in time.

For example, it would not be acceptable to report R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) when a more specific diagnosis code can be easily determined by patient history or exam findings (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11).

Affected Claims

As previously stated, “Medicare review contractors will not deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical record review.”3 The review contractors included are as follows:

- Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) process claims submitted by physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare professionals and submit payment to those providers according to Medicare rules and regulations (including identifying and correcting underpayments and overpayments);

- Recovery Auditors (RACs) review claims to identify potential underpayments and overpayments in Medicare fee-for-service, as part of the Recovery Audit Program;

- Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs) perform investigations that are unique and tailored to the specific circumstances and occur only in situations where there is potential fraud and take appropriate corrective actions; and

- Supplemental Medical Review Contractor (SMRCs) conduct nationwide medical review as directed by CMS (including identifying underpayments and overpayments).4

This instruction applies to claims that are typically selected for review due to the ICD-10-CM code used on the claim but does not affect claims that are selected for review for other reasons (e.g. modifier 25 [separately identifiable visit performed on the same day as another procedure or service], unbundling, service-specific current procedural terminology code). If a claim is selected for one of these other reasons and does not meet the corresponding criterion, the service will be denied. This instruction also excludes claims for services that correspond to an existing local coverage determination (LCD) or national coverage determination (NCD).

For example, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is not considered “medically necessary” when reported with R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) and would be denied. EGD requires a more specific diagnosis (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11) per Medicare LCD.

Non-Medicare Payer Considerations

Most payers that are required to convert to ICD-10-CM have also provided some guidance about claim submission. Although most do not address the audit and review process, payers will follow some basic principles:

- Claims submitted with service dates on or after October 1 must use ICD-10-CM codes.

- Claims submitted with service dates prior to October 1 must use ICD-9-CM codes; this includes claims that are initially submitted after October 1 or require correction and resubmission after October 1.

- Physician claims will be held to medical necessity guidelines identified by specific ICD-10-CM codes represented in existing payer policies.

- General equivalence mappings (GEMs) should only be used as a starting point to convert large databases and large code lists from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Many ICD-9-CM codes do not crosswalk directly to an ICD-10-CM code. Physician and staff should continue to use the ICD-10-CM coding books and resources to determine the most accurate code selection.

- “Unspecified” codes are only for use when the information in the medical record is insufficient to assign a more specific code.5,6,7

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10. July 6, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clarifying questions and answers related to the July 6, 2015 CMS/AMA joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Learning Network: Medicare claim review programs. May 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Aetna. Preparation for ICD-10-CM: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Independence Blue Cross. Transition to ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Cigna. Ready, Set, Switch: Know Your ICD-10 Codes. Accessed November 16, 2015.

Effective October 1, providers submit claims with ICD-10-CM codes. As they adapt to this new system, physicians, clinical staff, and billers should be relying on feedback from each other to achieve a successful transition. On July 6, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in conjunction with the AMA, issued a letter to the provider community offering ICD-10-CM guidance. The joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities minimizes the anxiety that often accompanies change and clarifies a few key points about claim scrutiny.1

According to the correspondence, “CMS is releasing additional guidance that will allow for flexibility in the claims auditing and quality reporting process as the medical community gains experience using the new ICD-10 code set.”1 The guidance specifies the flexibility that will be used during the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM use.

This “flexibility” is an opportunity and should not be disregarded. Physician practices can effectively use this time to become accustomed to the ICD-10-CM system, correct coding principles, and payer policy requirements. Internal audit and review processes should increase in order to correct or confirm appropriate coding and claim submission.

Valid Codes

Medicare review contractors are instructed “not to deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical review based solely on the specificity of the ICD-10 diagnosis code as long as the physician/practitioner used a valid code from the right family.”2 This “flexibility” will only occur for the first 12 months of ICD-10-CM implementation; the ultimate goal is for providers to assign the correct diagnosis code and the appropriate level of specificity after one year.

The “family code” allowance should not be confused with provision of an incomplete or truncated diagnosis code; these types of codes will always result in claim denial. The ICD-10-CM code presented on the claim form must be carried out to the highest character available for that particular code.

For example, an initial encounter involving an infected peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is reported with ICD-10-CM T80.212A (local infection due to central venous catheter). An individual unfamiliar with ICD-10-CM nomenclature may not realize that the seventh extension character of the code is required to carry the code out to its highest level of specificity. If T880.212 is mistakenly reported because the encounter detail (i.e., initial encounter [A], subsequent encounter [D], or sequela [S]) was not documented or provided to the biller, the payers’ claim edit system will identify this as a truncated or invalid diagnosis and reject the claim. Therefore, the code is required to be complete. The “flexibility” refers to reporting the code that best reflects the documented condition. As long as the reported code comes from the same family of codes and is valid, the claim cannot be denied.

Code Families

Code families are “codes within a category [that] are clinically related and provide differences in capturing specific information on the type of condition.”3 Upon review, Medicare will allow ICD-10-CM codes from the same code family to be reported on the claim without penalty if the most accurate code is not selected.

For example, a patient with COPD with acute exacerbation is admitted to the hospital. During the 12-month “flexibility” period, the claim could include J44.9 (COPD, unspecified) without being considered erroneous. The most appropriate code, however, is J44.1 (COPD with acute exacerbation). During the course of the hospitalization, if the physician determines that the COPD exacerbation was caused by an acute lower respiratory infection, J44.0 (COPD with acute lower respiratory infection) is the best option.

The provider goal for this flexibility period is to identify all of the “unspecified codes” used on their claims, review the documentation, and determine the most appropriate code. The practice staff assigned to this task would then provide feedback to the physicians to enhance their future reporting strategies. Although “unspecified” codes are often reported by default, physicians and staff should attempt to reduce usage of this code type unless the patient’s condition is unable to be further specified or categorized at a given point in time.

For example, it would not be acceptable to report R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) when a more specific diagnosis code can be easily determined by patient history or exam findings (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11).

Affected Claims

As previously stated, “Medicare review contractors will not deny physician or other practitioner claims billed under the Part B physician fee schedule through either automated medical review or complex medical record review.”3 The review contractors included are as follows:

- Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) process claims submitted by physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare professionals and submit payment to those providers according to Medicare rules and regulations (including identifying and correcting underpayments and overpayments);

- Recovery Auditors (RACs) review claims to identify potential underpayments and overpayments in Medicare fee-for-service, as part of the Recovery Audit Program;

- Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs) perform investigations that are unique and tailored to the specific circumstances and occur only in situations where there is potential fraud and take appropriate corrective actions; and

- Supplemental Medical Review Contractor (SMRCs) conduct nationwide medical review as directed by CMS (including identifying underpayments and overpayments).4

This instruction applies to claims that are typically selected for review due to the ICD-10-CM code used on the claim but does not affect claims that are selected for review for other reasons (e.g. modifier 25 [separately identifiable visit performed on the same day as another procedure or service], unbundling, service-specific current procedural terminology code). If a claim is selected for one of these other reasons and does not meet the corresponding criterion, the service will be denied. This instruction also excludes claims for services that correspond to an existing local coverage determination (LCD) or national coverage determination (NCD).

For example, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is not considered “medically necessary” when reported with R10.8 (unspecified abdominal pain) and would be denied. EGD requires a more specific diagnosis (e.g. right upper quadrant abdominal pain, R10.11) per Medicare LCD.

Non-Medicare Payer Considerations

Most payers that are required to convert to ICD-10-CM have also provided some guidance about claim submission. Although most do not address the audit and review process, payers will follow some basic principles:

- Claims submitted with service dates on or after October 1 must use ICD-10-CM codes.

- Claims submitted with service dates prior to October 1 must use ICD-9-CM codes; this includes claims that are initially submitted after October 1 or require correction and resubmission after October 1.

- Physician claims will be held to medical necessity guidelines identified by specific ICD-10-CM codes represented in existing payer policies.

- General equivalence mappings (GEMs) should only be used as a starting point to convert large databases and large code lists from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Many ICD-9-CM codes do not crosswalk directly to an ICD-10-CM code. Physician and staff should continue to use the ICD-10-CM coding books and resources to determine the most accurate code selection.

- “Unspecified” codes are only for use when the information in the medical record is insufficient to assign a more specific code.5,6,7

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10. July 6, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS and AMA announce efforts to help providers get ready for ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clarifying questions and answers related to the July 6, 2015 CMS/AMA joint announcement and guidance regarding ICD-10 flexibilities. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Learning Network: Medicare claim review programs. May 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Aetna. Preparation for ICD-10-CM: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Independence Blue Cross. Transition to ICD-10: frequently asked questions. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Cigna. Ready, Set, Switch: Know Your ICD-10 Codes. Accessed November 16, 2015.

Poor Continuity of Patient Care Increases Work for Hospitalist Groups

I think every hospitalist group should diligently try to maximize hospitalist-patient continuity, but many seem to adopt schedules and other operational practices that erode it. Let’s walk through the issue of continuity, starting with some history.

Inpatient Continuity in Old Healthcare System

Proudly carrying a pager nearly the size of a loaf of bread and wearing a white shirt and pants with Converse All Stars, I served as a hospital orderly in the 1970s. This position involved things like getting patients out of bed, placing Foley catheters, performing chest compressions during codes, and transporting the bodies of the deceased to the morgue. I really enjoyed the work, and the experience serves as one of my historical frames of reference for how hospital care has evolved since then.

The way I remember it, nearly everyone at the hospital worked a predictable schedule. RN staffing was the same each day; it didn’t vary based on census. Each full-time RN worked five shifts a week, eight hours each. Most or all would work alternate weekends and would have two compensatory days off during the following work week. This resulted in terrific continuity between nurse and patient, and the long length of stays meant patients and nurses got to know one another really well.

Continuity Takes a Hit

But things have changed. Nurse-patient continuity seems to have declined significantly as a result of two main forces: the hospital’s efforts to reduce staffing costs by varying nurse staffing to match daily patient volume, and nurses’ desire for a wide variety of work schedules. Asking a bedside nurse in today’s hospital whether the patient’s confusion, diarrhea, or appetite is meaningfully different today than yesterday typically yields the same reply. “This is my first day with the patient; I’ll have to look at the chart.”

I couldn’t find many research articles or editorials regarding hospital nurse-patient continuity from one day to the next. But several researchers seem to have begun studying this issue and have recently published a proposed framework for assessing it, and I found one study showing it wasn’t correlated with rates of pressure ulcers.1,2.

My anecdotal experience tells me continuity between the patient and caregivers of all stripes matters a lot. Research will be valuable in helping us to better understand its most significant costs and benefits, but I’m already convinced “Continuity is King” and should be one of the most important factors in the design of work schedules and patient allocation models for nurses and hospitalists alike.

While some might say we should wait for randomized trials of continuity to determine its importance, I’m inclined to see it like the authors of “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials.” As a ding against those who insist on research data when common sense may be sufficient, they concluded “…that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence-based medicine organised and participated in a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.3

Continuity and Hospitalists

On top of what I see as erosion in nurse-patient continuity, the arrival of hospitalists disrupted doctor-patient continuity across the inpatient and outpatient setting. While there was significant concern about this when our field first took off in the 1990s, it seems to be getting a great deal less attention over the last few years. In many hospitalist groups I work with, it is one of the last factors considered when creating a work schedule. Factors that are examined include the following:

- Solely for provider convenience, a group might regularly schedule a provider for only two or three consecutive daytime shifts, or sometimes only single days;

- Groups that use unit-based hospital (a.k.a. “geographic”) staffing might have a patient transfer to a different attending hospitalist solely as a result of moving to a room in a different nursing unit; and

- As part of morning load leveling, some groups reassign existing patients to a new hospitalist.

I think all groups should work hard to avoid doing these things. And while I seem to be a real outlier on this one, I think the benefits of a separate daytime hospitalist admitter shift are not worth the cost of having different doctors always do the admission and first follow-up visit. Most groups should consider moving the admitter into an additional rounder position and allocating daytime admissions across all hospitalists.

One study found that hospitalist discontinuity was not associated with adverse events, and another found it was associated with higher length of stay for selected diagnoses.4,5 But there is too little research to draw hard conclusions. I’m convinced poor continuity increases the possibility of handoff-related errors, likely results in lower patient satisfaction, and increases the overall work of the hospitalist group, because more providers have to take the time to get to know the patient.

Although there will always be some tension between terrific continuity and a sustainable hospitalist lifestyle—a person can work only so many consecutive days before wearing out—every group should thoughtfully consider whether they are doing everything reasonable to maximize continuity. After all, continuity is king.

References

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lopez KC, Khokhar A, Wilkie DJ, Keenan GM. Proposing a new conceptual model and an exemplar measure using health information technology to examine the impact of relational nurse continuity on hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2015;38(3):241-251.

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lodhi MK, et al. Nurse continuity and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a comparative analysis using an electronic health record “big data” set. Nurs Res. 2015;64(5):361-371.

- Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;327(7429):1459-1461.

- O’Leary KJ, Turner J, Christensen N, et al. The effect of hospitalist discontinuity on adverse events. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):147-151.

- Epstein K, Juarez E, Epstein A, Loya K, Singer A. The impact of fragmentation of hospitalist care on length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):335-338.

I think every hospitalist group should diligently try to maximize hospitalist-patient continuity, but many seem to adopt schedules and other operational practices that erode it. Let’s walk through the issue of continuity, starting with some history.

Inpatient Continuity in Old Healthcare System

Proudly carrying a pager nearly the size of a loaf of bread and wearing a white shirt and pants with Converse All Stars, I served as a hospital orderly in the 1970s. This position involved things like getting patients out of bed, placing Foley catheters, performing chest compressions during codes, and transporting the bodies of the deceased to the morgue. I really enjoyed the work, and the experience serves as one of my historical frames of reference for how hospital care has evolved since then.

The way I remember it, nearly everyone at the hospital worked a predictable schedule. RN staffing was the same each day; it didn’t vary based on census. Each full-time RN worked five shifts a week, eight hours each. Most or all would work alternate weekends and would have two compensatory days off during the following work week. This resulted in terrific continuity between nurse and patient, and the long length of stays meant patients and nurses got to know one another really well.

Continuity Takes a Hit

But things have changed. Nurse-patient continuity seems to have declined significantly as a result of two main forces: the hospital’s efforts to reduce staffing costs by varying nurse staffing to match daily patient volume, and nurses’ desire for a wide variety of work schedules. Asking a bedside nurse in today’s hospital whether the patient’s confusion, diarrhea, or appetite is meaningfully different today than yesterday typically yields the same reply. “This is my first day with the patient; I’ll have to look at the chart.”

I couldn’t find many research articles or editorials regarding hospital nurse-patient continuity from one day to the next. But several researchers seem to have begun studying this issue and have recently published a proposed framework for assessing it, and I found one study showing it wasn’t correlated with rates of pressure ulcers.1,2.

My anecdotal experience tells me continuity between the patient and caregivers of all stripes matters a lot. Research will be valuable in helping us to better understand its most significant costs and benefits, but I’m already convinced “Continuity is King” and should be one of the most important factors in the design of work schedules and patient allocation models for nurses and hospitalists alike.

While some might say we should wait for randomized trials of continuity to determine its importance, I’m inclined to see it like the authors of “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials.” As a ding against those who insist on research data when common sense may be sufficient, they concluded “…that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence-based medicine organised and participated in a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.3

Continuity and Hospitalists

On top of what I see as erosion in nurse-patient continuity, the arrival of hospitalists disrupted doctor-patient continuity across the inpatient and outpatient setting. While there was significant concern about this when our field first took off in the 1990s, it seems to be getting a great deal less attention over the last few years. In many hospitalist groups I work with, it is one of the last factors considered when creating a work schedule. Factors that are examined include the following:

- Solely for provider convenience, a group might regularly schedule a provider for only two or three consecutive daytime shifts, or sometimes only single days;

- Groups that use unit-based hospital (a.k.a. “geographic”) staffing might have a patient transfer to a different attending hospitalist solely as a result of moving to a room in a different nursing unit; and

- As part of morning load leveling, some groups reassign existing patients to a new hospitalist.

I think all groups should work hard to avoid doing these things. And while I seem to be a real outlier on this one, I think the benefits of a separate daytime hospitalist admitter shift are not worth the cost of having different doctors always do the admission and first follow-up visit. Most groups should consider moving the admitter into an additional rounder position and allocating daytime admissions across all hospitalists.

One study found that hospitalist discontinuity was not associated with adverse events, and another found it was associated with higher length of stay for selected diagnoses.4,5 But there is too little research to draw hard conclusions. I’m convinced poor continuity increases the possibility of handoff-related errors, likely results in lower patient satisfaction, and increases the overall work of the hospitalist group, because more providers have to take the time to get to know the patient.

Although there will always be some tension between terrific continuity and a sustainable hospitalist lifestyle—a person can work only so many consecutive days before wearing out—every group should thoughtfully consider whether they are doing everything reasonable to maximize continuity. After all, continuity is king.

References

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lopez KC, Khokhar A, Wilkie DJ, Keenan GM. Proposing a new conceptual model and an exemplar measure using health information technology to examine the impact of relational nurse continuity on hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2015;38(3):241-251.

- Stifter J, Yao Y, Lodhi MK, et al. Nurse continuity and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a comparative analysis using an electronic health record “big data” set. Nurs Res. 2015;64(5):361-371.

- Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;327(7429):1459-1461.

- O’Leary KJ, Turner J, Christensen N, et al. The effect of hospitalist discontinuity on adverse events. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):147-151.

- Epstein K, Juarez E, Epstein A, Loya K, Singer A. The impact of fragmentation of hospitalist care on length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):335-338.

I think every hospitalist group should diligently try to maximize hospitalist-patient continuity, but many seem to adopt schedules and other operational practices that erode it. Let’s walk through the issue of continuity, starting with some history.

Inpatient Continuity in Old Healthcare System

Proudly carrying a pager nearly the size of a loaf of bread and wearing a white shirt and pants with Converse All Stars, I served as a hospital orderly in the 1970s. This position involved things like getting patients out of bed, placing Foley catheters, performing chest compressions during codes, and transporting the bodies of the deceased to the morgue. I really enjoyed the work, and the experience serves as one of my historical frames of reference for how hospital care has evolved since then.

The way I remember it, nearly everyone at the hospital worked a predictable schedule. RN staffing was the same each day; it didn’t vary based on census. Each full-time RN worked five shifts a week, eight hours each. Most or all would work alternate weekends and would have two compensatory days off during the following work week. This resulted in terrific continuity between nurse and patient, and the long length of stays meant patients and nurses got to know one another really well.

Continuity Takes a Hit

But things have changed. Nurse-patient continuity seems to have declined significantly as a result of two main forces: the hospital’s efforts to reduce staffing costs by varying nurse staffing to match daily patient volume, and nurses’ desire for a wide variety of work schedules. Asking a bedside nurse in today’s hospital whether the patient’s confusion, diarrhea, or appetite is meaningfully different today than yesterday typically yields the same reply. “This is my first day with the patient; I’ll have to look at the chart.”

I couldn’t find many research articles or editorials regarding hospital nurse-patient continuity from one day to the next. But several researchers seem to have begun studying this issue and have recently published a proposed framework for assessing it, and I found one study showing it wasn’t correlated with rates of pressure ulcers.1,2.

My anecdotal experience tells me continuity between the patient and caregivers of all stripes matters a lot. Research will be valuable in helping us to better understand its most significant costs and benefits, but I’m already convinced “Continuity is King” and should be one of the most important factors in the design of work schedules and patient allocation models for nurses and hospitalists alike.

While some might say we should wait for randomized trials of continuity to determine its importance, I’m inclined to see it like the authors of “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials.” As a ding against those who insist on research data when common sense may be sufficient, they concluded “…that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence-based medicine organised and participated in a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.3

Continuity and Hospitalists

On top of what I see as erosion in nurse-patient continuity, the arrival of hospitalists disrupted doctor-patient continuity across the inpatient and outpatient setting. While there was significant concern about this when our field first took off in the 1990s, it seems to be getting a great deal less attention over the last few years. In many hospitalist groups I work with, it is one of the last factors considered when creating a work schedule. Factors that are examined include the following:

- Solely for provider convenience, a group might regularly schedule a provider for only two or three consecutive daytime shifts, or sometimes only single days;

- Groups that use unit-based hospital (a.k.a. “geographic”) staffing might have a patient transfer to a different attending hospitalist solely as a result of moving to a room in a different nursing unit; and

- As part of morning load leveling, some groups reassign existing patients to a new hospitalist.