User login

AUDIO: Meaningful use interoperability ‘won’t work without the Internet’

WASHINGTON – The rules for Stage 3 of the meaningful use program have been finalized by the Obama administration, despite questions about physicians’ ability to achieve “interoperability” and pleas from politicians and providers alike to delay its implementation.

Jonathan Bush, cofounder and CEO of athenahealth, said he believes interoperability will be a no-go unless data are seen as common property, and a premium is placed on the seamless transition of medical records by way of the Internet, not faxes.

Speaking about the large sums of money being spent by hospitals to comply with the government’s meaningful use requirements, Mr. Bush said, “they’re going to staff up hundreds of people who aren’t going to be able to run it. It doesn’t connect to anyone.”

In an interview at the annual Washington Ideas Forum sponsored by the Aspen Institute and The Atlantic, Mr. Bush offered his thoughts on how data could be more easily shared.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – The rules for Stage 3 of the meaningful use program have been finalized by the Obama administration, despite questions about physicians’ ability to achieve “interoperability” and pleas from politicians and providers alike to delay its implementation.

Jonathan Bush, cofounder and CEO of athenahealth, said he believes interoperability will be a no-go unless data are seen as common property, and a premium is placed on the seamless transition of medical records by way of the Internet, not faxes.

Speaking about the large sums of money being spent by hospitals to comply with the government’s meaningful use requirements, Mr. Bush said, “they’re going to staff up hundreds of people who aren’t going to be able to run it. It doesn’t connect to anyone.”

In an interview at the annual Washington Ideas Forum sponsored by the Aspen Institute and The Atlantic, Mr. Bush offered his thoughts on how data could be more easily shared.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – The rules for Stage 3 of the meaningful use program have been finalized by the Obama administration, despite questions about physicians’ ability to achieve “interoperability” and pleas from politicians and providers alike to delay its implementation.

Jonathan Bush, cofounder and CEO of athenahealth, said he believes interoperability will be a no-go unless data are seen as common property, and a premium is placed on the seamless transition of medical records by way of the Internet, not faxes.

Speaking about the large sums of money being spent by hospitals to comply with the government’s meaningful use requirements, Mr. Bush said, “they’re going to staff up hundreds of people who aren’t going to be able to run it. It doesn’t connect to anyone.”

In an interview at the annual Washington Ideas Forum sponsored by the Aspen Institute and The Atlantic, Mr. Bush offered his thoughts on how data could be more easily shared.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WASHINGTON IDEAS FORUM

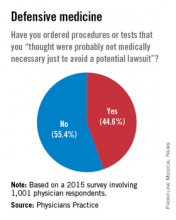

Survey: 45% order tests to avoid lawsuits

Almost 45% of physicians say that they have practiced defensive medicine, according to a survey of 1,001 physicians conducted by Physicians Practice, a practice management newspaper and website.

To be exact, 44.6% of respondents said that they had ordered tests or procedures that they “thought were probably not medically necessary just to avoid a potential lawsuit,” Physicians Practice reported in its 2015 Great American Physician Survey.

Almost 44% of the physician respondents said that they had been threatened with a malpractice lawsuit, and nearly 32% reported that they had been the defendant in such a lawsuit, the survey results showed.

Almost 45% of physicians say that they have practiced defensive medicine, according to a survey of 1,001 physicians conducted by Physicians Practice, a practice management newspaper and website.

To be exact, 44.6% of respondents said that they had ordered tests or procedures that they “thought were probably not medically necessary just to avoid a potential lawsuit,” Physicians Practice reported in its 2015 Great American Physician Survey.

Almost 44% of the physician respondents said that they had been threatened with a malpractice lawsuit, and nearly 32% reported that they had been the defendant in such a lawsuit, the survey results showed.

Almost 45% of physicians say that they have practiced defensive medicine, according to a survey of 1,001 physicians conducted by Physicians Practice, a practice management newspaper and website.

To be exact, 44.6% of respondents said that they had ordered tests or procedures that they “thought were probably not medically necessary just to avoid a potential lawsuit,” Physicians Practice reported in its 2015 Great American Physician Survey.

Almost 44% of the physician respondents said that they had been threatened with a malpractice lawsuit, and nearly 32% reported that they had been the defendant in such a lawsuit, the survey results showed.

Billing, Coding Documentation to Support Services, Minimize Risks

The electronic health record (EHR) has many benefits:

- Improved patient care;

- Improved care coordination;

- Improved diagnostics and patient outcomes;

- Increased patient participation; and

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings.1

EHRs also introduce risks, however. Heightened concern about EHR misuse and vulnerability elevates the level of scrutiny placed on provider documentation as it relates to billing and coding. Without clear guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other payers, the potential for unintentional misapplication exists. Auditor misinterpretation is also possible. Providers should utilize simple defensive documentation principles to support their services and minimize their risks.

Reason for Encounter

Under section 1862 (a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare Program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).2

A payer can determine if a service is “reasonable and necessary” based on the service indication. The reason for the patient encounter, otherwise known as the chief complaint, must be evident. This can be a symptom, problem, condition, diagnosis, physician-recommended return, or another factor that necessitates the encounter.1 It cannot be inferred and must be clearly stated in the documentation. Without it, a payer may question the medical necessity of the service, especially if it involves hospital-based services in the course of which multiple specialists will see the patient on any given date. Payers are likely to deny services that cannot be easily differentiated (e.g. “no c/o”). Furthermore, payers can deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:3

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate/overlap those of the other provider without any recognizable distinction.

Providers should be specific in identifying the encounter reason, as in the following examples: “Patient seen for shortness of breath” or “Patient with COPD, feeling improved with 3L O2 NC.”

Assessment and Plan

Accurately representing patient complexity for every visit throughout the hospitalization presents its challenges. Although the problem list may not dramatically change day to day, providers must formulate an assessment of the patient’s condition with a corresponding plan of care for each encounter. Documenting problems without a corresponding plan of care does not substantiate physician participation in the management of that problem. Providing a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) minimizes the complexity and effort put forth in the encounter and could result in auditor downgrading upon documentation review.

Developing shortcuts might falsely minimize the provider’s documentation burden. An electronic documentation system might make it possible to copy previous progress notes into the current encounter to save time; however, the previously entered information could include elements that do not require reassessment during a subsequent encounter or contain information about conditions that are being managed concurrently by another specialist (e.g. CKD being managed by the nephrologist). Leaving the copied information unmodified may not accurately reflect the patient’s current condition or the care provided by the hospitalist during the current encounter. Information that is pulled forward or copied and pasted from a previous entry should be modified to demonstrate updated content and nonoverlapping care relevant to that date.

According to the Office of Inspector General (OIG), “inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.”4

An equally problematic EHR function involves “overdocumentation,” the practice of inserting false or irrelevant documentation to create the appearance of support for billing higher level services.4 EHR technology has the ability to auto-populate fields using templates built into the system or generate extensive documentation on the basis of a single click. The OIG cautions providers to use these features carefully, because they can produce information suggesting the practitioner performed more comprehensive services than were actually rendered.4

An example is the inclusion of the same lab results more than once. Although clinicians include this information as a reference to avoid having to “find it somewhere in the chart” when it is needed—as a basis for comparison, for example—auditors mistake this as an attempt to gain credit for the daily review of the same “old” information. Including only relevant data will mitigate this concern.

Authorship

Dates and signatures are essential to each encounter. Medicare requires services provided/ordered to be authenticated by the author.5 A reviewer must be able to identify each individual who performs, documents, and bills for a service on a given date. Progress notes that fail to identify the service date or service provider will likely result in denial.

Additionally, a service is questioned when two different sets of handwriting appear on a note, yet only one signature is provided. Since the reviewer cannot confirm the credentials of the unidentified individual and cannot be sure which portion belongs to the identified individual, the entire note is disregarded.

Notes that contain an illegible signature are equally problematic. If the legibility of the signature prevents the reviewer from correctly identifying the rendering provider, the service may be denied.

CMS has instructed Medicare contractors to request a signed provider attestation before issuing a denial.5 The provider should print his/her name beside the signature or include a separate signature sheet with the requested documentation to assist the reviewer in provider identification. Stamped signatures are not acceptable under any circumstance. Medicare accepts only handwritten or electronic signatures.5

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- HealthIT.gov. Benefits of electronic health records (EHRs). Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as secondary payer. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered medical and other health services. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. Concurrent care. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. CMS and its contractors have adopted few program integrity practices to address vulnerabilities in EHRs. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Signature guidelines for medical review purposes. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Accessed August 1, 2015.

The electronic health record (EHR) has many benefits:

- Improved patient care;

- Improved care coordination;

- Improved diagnostics and patient outcomes;

- Increased patient participation; and

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings.1

EHRs also introduce risks, however. Heightened concern about EHR misuse and vulnerability elevates the level of scrutiny placed on provider documentation as it relates to billing and coding. Without clear guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other payers, the potential for unintentional misapplication exists. Auditor misinterpretation is also possible. Providers should utilize simple defensive documentation principles to support their services and minimize their risks.

Reason for Encounter

Under section 1862 (a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare Program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).2

A payer can determine if a service is “reasonable and necessary” based on the service indication. The reason for the patient encounter, otherwise known as the chief complaint, must be evident. This can be a symptom, problem, condition, diagnosis, physician-recommended return, or another factor that necessitates the encounter.1 It cannot be inferred and must be clearly stated in the documentation. Without it, a payer may question the medical necessity of the service, especially if it involves hospital-based services in the course of which multiple specialists will see the patient on any given date. Payers are likely to deny services that cannot be easily differentiated (e.g. “no c/o”). Furthermore, payers can deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:3

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate/overlap those of the other provider without any recognizable distinction.

Providers should be specific in identifying the encounter reason, as in the following examples: “Patient seen for shortness of breath” or “Patient with COPD, feeling improved with 3L O2 NC.”

Assessment and Plan

Accurately representing patient complexity for every visit throughout the hospitalization presents its challenges. Although the problem list may not dramatically change day to day, providers must formulate an assessment of the patient’s condition with a corresponding plan of care for each encounter. Documenting problems without a corresponding plan of care does not substantiate physician participation in the management of that problem. Providing a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) minimizes the complexity and effort put forth in the encounter and could result in auditor downgrading upon documentation review.

Developing shortcuts might falsely minimize the provider’s documentation burden. An electronic documentation system might make it possible to copy previous progress notes into the current encounter to save time; however, the previously entered information could include elements that do not require reassessment during a subsequent encounter or contain information about conditions that are being managed concurrently by another specialist (e.g. CKD being managed by the nephrologist). Leaving the copied information unmodified may not accurately reflect the patient’s current condition or the care provided by the hospitalist during the current encounter. Information that is pulled forward or copied and pasted from a previous entry should be modified to demonstrate updated content and nonoverlapping care relevant to that date.

According to the Office of Inspector General (OIG), “inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.”4

An equally problematic EHR function involves “overdocumentation,” the practice of inserting false or irrelevant documentation to create the appearance of support for billing higher level services.4 EHR technology has the ability to auto-populate fields using templates built into the system or generate extensive documentation on the basis of a single click. The OIG cautions providers to use these features carefully, because they can produce information suggesting the practitioner performed more comprehensive services than were actually rendered.4

An example is the inclusion of the same lab results more than once. Although clinicians include this information as a reference to avoid having to “find it somewhere in the chart” when it is needed—as a basis for comparison, for example—auditors mistake this as an attempt to gain credit for the daily review of the same “old” information. Including only relevant data will mitigate this concern.

Authorship

Dates and signatures are essential to each encounter. Medicare requires services provided/ordered to be authenticated by the author.5 A reviewer must be able to identify each individual who performs, documents, and bills for a service on a given date. Progress notes that fail to identify the service date or service provider will likely result in denial.

Additionally, a service is questioned when two different sets of handwriting appear on a note, yet only one signature is provided. Since the reviewer cannot confirm the credentials of the unidentified individual and cannot be sure which portion belongs to the identified individual, the entire note is disregarded.

Notes that contain an illegible signature are equally problematic. If the legibility of the signature prevents the reviewer from correctly identifying the rendering provider, the service may be denied.

CMS has instructed Medicare contractors to request a signed provider attestation before issuing a denial.5 The provider should print his/her name beside the signature or include a separate signature sheet with the requested documentation to assist the reviewer in provider identification. Stamped signatures are not acceptable under any circumstance. Medicare accepts only handwritten or electronic signatures.5

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- HealthIT.gov. Benefits of electronic health records (EHRs). Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as secondary payer. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered medical and other health services. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. Concurrent care. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. CMS and its contractors have adopted few program integrity practices to address vulnerabilities in EHRs. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Signature guidelines for medical review purposes. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Accessed August 1, 2015.

The electronic health record (EHR) has many benefits:

- Improved patient care;

- Improved care coordination;

- Improved diagnostics and patient outcomes;

- Increased patient participation; and

- Increased practice efficiencies and cost savings.1

EHRs also introduce risks, however. Heightened concern about EHR misuse and vulnerability elevates the level of scrutiny placed on provider documentation as it relates to billing and coding. Without clear guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or other payers, the potential for unintentional misapplication exists. Auditor misinterpretation is also possible. Providers should utilize simple defensive documentation principles to support their services and minimize their risks.

Reason for Encounter

Under section 1862 (a)(1)(A) of the Social Security Act, the Medicare Program may only pay for items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,” unless there is another statutory authorization for payment (e.g. colorectal cancer screening).2

A payer can determine if a service is “reasonable and necessary” based on the service indication. The reason for the patient encounter, otherwise known as the chief complaint, must be evident. This can be a symptom, problem, condition, diagnosis, physician-recommended return, or another factor that necessitates the encounter.1 It cannot be inferred and must be clearly stated in the documentation. Without it, a payer may question the medical necessity of the service, especially if it involves hospital-based services in the course of which multiple specialists will see the patient on any given date. Payers are likely to deny services that cannot be easily differentiated (e.g. “no c/o”). Furthermore, payers can deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:3

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate/overlap those of the other provider without any recognizable distinction.

Providers should be specific in identifying the encounter reason, as in the following examples: “Patient seen for shortness of breath” or “Patient with COPD, feeling improved with 3L O2 NC.”

Assessment and Plan

Accurately representing patient complexity for every visit throughout the hospitalization presents its challenges. Although the problem list may not dramatically change day to day, providers must formulate an assessment of the patient’s condition with a corresponding plan of care for each encounter. Documenting problems without a corresponding plan of care does not substantiate physician participation in the management of that problem. Providing a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) minimizes the complexity and effort put forth in the encounter and could result in auditor downgrading upon documentation review.

Developing shortcuts might falsely minimize the provider’s documentation burden. An electronic documentation system might make it possible to copy previous progress notes into the current encounter to save time; however, the previously entered information could include elements that do not require reassessment during a subsequent encounter or contain information about conditions that are being managed concurrently by another specialist (e.g. CKD being managed by the nephrologist). Leaving the copied information unmodified may not accurately reflect the patient’s current condition or the care provided by the hospitalist during the current encounter. Information that is pulled forward or copied and pasted from a previous entry should be modified to demonstrate updated content and nonoverlapping care relevant to that date.

According to the Office of Inspector General (OIG), “inappropriate copy-pasting could facilitate attempts to inflate claims and duplicate or create fraudulent claims.”4

An equally problematic EHR function involves “overdocumentation,” the practice of inserting false or irrelevant documentation to create the appearance of support for billing higher level services.4 EHR technology has the ability to auto-populate fields using templates built into the system or generate extensive documentation on the basis of a single click. The OIG cautions providers to use these features carefully, because they can produce information suggesting the practitioner performed more comprehensive services than were actually rendered.4

An example is the inclusion of the same lab results more than once. Although clinicians include this information as a reference to avoid having to “find it somewhere in the chart” when it is needed—as a basis for comparison, for example—auditors mistake this as an attempt to gain credit for the daily review of the same “old” information. Including only relevant data will mitigate this concern.

Authorship

Dates and signatures are essential to each encounter. Medicare requires services provided/ordered to be authenticated by the author.5 A reviewer must be able to identify each individual who performs, documents, and bills for a service on a given date. Progress notes that fail to identify the service date or service provider will likely result in denial.

Additionally, a service is questioned when two different sets of handwriting appear on a note, yet only one signature is provided. Since the reviewer cannot confirm the credentials of the unidentified individual and cannot be sure which portion belongs to the identified individual, the entire note is disregarded.

Notes that contain an illegible signature are equally problematic. If the legibility of the signature prevents the reviewer from correctly identifying the rendering provider, the service may be denied.

CMS has instructed Medicare contractors to request a signed provider attestation before issuing a denial.5 The provider should print his/her name beside the signature or include a separate signature sheet with the requested documentation to assist the reviewer in provider identification. Stamped signatures are not acceptable under any circumstance. Medicare accepts only handwritten or electronic signatures.5

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- HealthIT.gov. Benefits of electronic health records (EHRs). Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Social Security Administration. Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as secondary payer. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15—Covered medical and other health services. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. Concurrent care. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. CMS and its contractors have adopted few program integrity practices to address vulnerabilities in EHRs. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Signature guidelines for medical review purposes. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Accessed August 1, 2015.

Multistate compact could ease telemedicine licensing woes

As telemedicine hospitalists, one of the biggest challenges for Dr. Dana Giarrizzi and her staff is learning and staying updated on the many different state licensing rules.

Renewal time and dates vary, along with state requirements to become licensed and remain current, said Dr. Giarrizzi, national medical director for telehospitalist services at Eagle Hospital Physicians, based in Atlanta.

“One state renews on your birthday,” she said. Another “renews when you first activated your license. This one is every 2 years. This one requires CME. It’s hard to keep up with all the rules, and it’s costly.”

Dr. Giarrizzi believes a federal licensure process would be ideal, but she is also hopeful about state legislation in the form of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. The model legislation was developed by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and aims to make it easier for telemedicine physicians to gain licenses in multiple states.

Under the legislation, physicians designate a member state as the state of principal licensure and select the other states they wish to gain licenses within. The state of principal licensure then verifies the physician’s eligibility and provides credential information to the interstate commission, which collects applicable fees and transmits the doctor’s information to the other states. Upon receipt in the additional states, the physician would be granted a license.

As of early October 2015, 11 states had enacted the compact legislation, and at least 19 states had introduced the legislation. In July, the Health Resources and Services Administration awarded the FSMB a grant to support establishment of the commission and aid with the compact’s infrastructure.

Broad support by medical associations, patients, and state leaders have quickly propelled the compact forward, said Lisa Robin, FSMB chief advocacy officer.

“I think the boards recognize the potential for telemedicine and what that can bring as far as access to health care,” Ms. Robin said. “As technologies are here – and it’s changing every day – this is a mechanism that will allow for much more efficiency and less administrative burden on the process for licensure for physicians who want to practice in multiple states.”

There have been several misconceptions tied to the compact law, Ms. Robin noted.

The compact does not change a state’s medical practice act, she stressed, nor does it create a national licensure system. In addition, the legislation does not require a physician to participate in maintenance of certification at any stage. Under the compact, approved physicians would be under the jurisdiction of the state medical board in which the patient is located at the time of the medical interaction. State boards of medicine would retain their individual authority for discipline and oversight.

The compact hopefully will reduce physicians’ frustrations and lessen administrative hassles for doctors who wish to use telehealth technologies to bring their expertise to patients across multiple states, said Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, president of the American Telemedicine Association.

“There have been several models proposed to address both of these objectives, and it appears that the Federation of State Medical Boards’ licensure model compact has emerged as the most practical and implementable of the various approaches,” Dr. Tuckson explained. “We do hope that this compact model can function efficiently and cost effectively, so that physicians are not overburdened as well-meaning organizations attempt to ensure that the public’s interests are safeguarded.”

Dr. Giarrizzi of Eagle Hospital Physicians is also optimistic about the compact.

“I am hoping this helps streamline the information,” she said. “I know it will still take time, because it is not taking away the need to go through the process, but seems more like it is just sharing the information. It will make it easier for us to cross state lines if the states we want to work in agree with this process and participate.”

On Twitter @legal_med

As telemedicine hospitalists, one of the biggest challenges for Dr. Dana Giarrizzi and her staff is learning and staying updated on the many different state licensing rules.

Renewal time and dates vary, along with state requirements to become licensed and remain current, said Dr. Giarrizzi, national medical director for telehospitalist services at Eagle Hospital Physicians, based in Atlanta.

“One state renews on your birthday,” she said. Another “renews when you first activated your license. This one is every 2 years. This one requires CME. It’s hard to keep up with all the rules, and it’s costly.”

Dr. Giarrizzi believes a federal licensure process would be ideal, but she is also hopeful about state legislation in the form of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. The model legislation was developed by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and aims to make it easier for telemedicine physicians to gain licenses in multiple states.

Under the legislation, physicians designate a member state as the state of principal licensure and select the other states they wish to gain licenses within. The state of principal licensure then verifies the physician’s eligibility and provides credential information to the interstate commission, which collects applicable fees and transmits the doctor’s information to the other states. Upon receipt in the additional states, the physician would be granted a license.

As of early October 2015, 11 states had enacted the compact legislation, and at least 19 states had introduced the legislation. In July, the Health Resources and Services Administration awarded the FSMB a grant to support establishment of the commission and aid with the compact’s infrastructure.

Broad support by medical associations, patients, and state leaders have quickly propelled the compact forward, said Lisa Robin, FSMB chief advocacy officer.

“I think the boards recognize the potential for telemedicine and what that can bring as far as access to health care,” Ms. Robin said. “As technologies are here – and it’s changing every day – this is a mechanism that will allow for much more efficiency and less administrative burden on the process for licensure for physicians who want to practice in multiple states.”

There have been several misconceptions tied to the compact law, Ms. Robin noted.

The compact does not change a state’s medical practice act, she stressed, nor does it create a national licensure system. In addition, the legislation does not require a physician to participate in maintenance of certification at any stage. Under the compact, approved physicians would be under the jurisdiction of the state medical board in which the patient is located at the time of the medical interaction. State boards of medicine would retain their individual authority for discipline and oversight.

The compact hopefully will reduce physicians’ frustrations and lessen administrative hassles for doctors who wish to use telehealth technologies to bring their expertise to patients across multiple states, said Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, president of the American Telemedicine Association.

“There have been several models proposed to address both of these objectives, and it appears that the Federation of State Medical Boards’ licensure model compact has emerged as the most practical and implementable of the various approaches,” Dr. Tuckson explained. “We do hope that this compact model can function efficiently and cost effectively, so that physicians are not overburdened as well-meaning organizations attempt to ensure that the public’s interests are safeguarded.”

Dr. Giarrizzi of Eagle Hospital Physicians is also optimistic about the compact.

“I am hoping this helps streamline the information,” she said. “I know it will still take time, because it is not taking away the need to go through the process, but seems more like it is just sharing the information. It will make it easier for us to cross state lines if the states we want to work in agree with this process and participate.”

On Twitter @legal_med

As telemedicine hospitalists, one of the biggest challenges for Dr. Dana Giarrizzi and her staff is learning and staying updated on the many different state licensing rules.

Renewal time and dates vary, along with state requirements to become licensed and remain current, said Dr. Giarrizzi, national medical director for telehospitalist services at Eagle Hospital Physicians, based in Atlanta.

“One state renews on your birthday,” she said. Another “renews when you first activated your license. This one is every 2 years. This one requires CME. It’s hard to keep up with all the rules, and it’s costly.”

Dr. Giarrizzi believes a federal licensure process would be ideal, but she is also hopeful about state legislation in the form of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. The model legislation was developed by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and aims to make it easier for telemedicine physicians to gain licenses in multiple states.

Under the legislation, physicians designate a member state as the state of principal licensure and select the other states they wish to gain licenses within. The state of principal licensure then verifies the physician’s eligibility and provides credential information to the interstate commission, which collects applicable fees and transmits the doctor’s information to the other states. Upon receipt in the additional states, the physician would be granted a license.

As of early October 2015, 11 states had enacted the compact legislation, and at least 19 states had introduced the legislation. In July, the Health Resources and Services Administration awarded the FSMB a grant to support establishment of the commission and aid with the compact’s infrastructure.

Broad support by medical associations, patients, and state leaders have quickly propelled the compact forward, said Lisa Robin, FSMB chief advocacy officer.

“I think the boards recognize the potential for telemedicine and what that can bring as far as access to health care,” Ms. Robin said. “As technologies are here – and it’s changing every day – this is a mechanism that will allow for much more efficiency and less administrative burden on the process for licensure for physicians who want to practice in multiple states.”

There have been several misconceptions tied to the compact law, Ms. Robin noted.

The compact does not change a state’s medical practice act, she stressed, nor does it create a national licensure system. In addition, the legislation does not require a physician to participate in maintenance of certification at any stage. Under the compact, approved physicians would be under the jurisdiction of the state medical board in which the patient is located at the time of the medical interaction. State boards of medicine would retain their individual authority for discipline and oversight.

The compact hopefully will reduce physicians’ frustrations and lessen administrative hassles for doctors who wish to use telehealth technologies to bring their expertise to patients across multiple states, said Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, president of the American Telemedicine Association.

“There have been several models proposed to address both of these objectives, and it appears that the Federation of State Medical Boards’ licensure model compact has emerged as the most practical and implementable of the various approaches,” Dr. Tuckson explained. “We do hope that this compact model can function efficiently and cost effectively, so that physicians are not overburdened as well-meaning organizations attempt to ensure that the public’s interests are safeguarded.”

Dr. Giarrizzi of Eagle Hospital Physicians is also optimistic about the compact.

“I am hoping this helps streamline the information,” she said. “I know it will still take time, because it is not taking away the need to go through the process, but seems more like it is just sharing the information. It will make it easier for us to cross state lines if the states we want to work in agree with this process and participate.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Telemedicine poses novel legal risks for doctors

Physicians who practice telemedicine have a lot to consider, including state laws, payment issues, and licensing regulations. But one overlooked area may pose the greatest risk of all: medical liability.

As the practice of telemedicine continues to grow, so do the legal risks associated with virtual care, said Dr. Joseph P. McMenamin, an emergency physician and health law defense attorney based in Richmond, Va.

“With good reason, there is a concern that as this form of care expands, claims against physicians will increase,” Dr. McMenamin said. “That’s almost inevitable, given how our society looks at litigation and how willing we are to sue our doctors. If you’re a plaintiffs’ attorney, you might be attracted to cases of this kind – partly because jurors may fear the unknown, and they may view [telemedicine] with some concern and suspicion.”

Telemedicine can fuel a wide spectrum of legal dangers, including malpractice, product liability claims, data exposure, and credentialing risks. Making matters more complicated: No uniform standard of care exists for telemedicine when it comes to medical malpractice, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney who specializes in telemedicine and e-health practices.

“There are a lot of unanswered questions, including the prevailing standard of care,” Mr. Quashie explained. “Can we use the standard of care that we use for services provided in person for telehealth consults? Informed consent – does that process need to change? There are a lot of unanswered issues, which can only be resolved after a number of cases” are decided in the courts.

Physicians who practice telemedicine should consider legal risks associated with patient and staff privacy, inaccuracies in self-reporting, and symptoms that are more accurately diagnosed in person, said Richard F. Cahill, vice president and associate general counsel for the Doctors Company, a national medical liability insurer.

During 2007-2014, the Doctors Company had 11 claims that closed related to telemedicine, according to data provided by Mr. Cahill.

The majority of claims resulted from the remote reading of x-rays and other films by health providers, usually from home, and the remote reading of fetal monitor strips by physicians when outside of the hospital. Two of the cases were associated with attempts to diagnose a patient via telemedicine. Of the claims, six were diagnosis related, two alleged delay in treatment, two were related to improper performance of treatment, and one was associated with failure to order medication.

“The challenges of remote communications made it difficult to formulate the correct diagnosis due to limitations of radiology resolution, delayed readings of radiographs, or limits on fetal monitor strips,” said Darrell Ranum, vice president of patient safety and risk management for the Doctors Company. “Delays in treatment were closely related to delayed diagnosis. Radiologists did not receive a request for an interpretation, or they did not know that it was an emergency, so they did not provide a rapid turnaround report.”

While telemedicine claims have been low so far, a rise in the number of patient contacts, regardless of modality, may increase the risk of adverse consequences, Mr. Cahill cautioned.

“Because telemedicine is relatively new, and it takes 3-4 years for a claim to work its way through the system, we may see more cases in the future in which telemedicine is a factor,” he predicted.

Other lawsuits could arise from claims that physicians had access to telemedicine but failed to use the technology to properly treat a patient, Mr. Quashie said. Product liability claims also pose a threat, added Dr. McMenamin, who is part of the Legal Resource Team at the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law (CTeL). Such accusations stem from equipment that malfunctioned or failed to work as indicated.

Varying credentialing rules also can trip up doctors who work virtually. Physicians at a large academic medical center, for example, could face trouble if they aren’t credentialed at the small rural hospital where a patient is located, Dr. McMenamin said. He noted that Medicare modified its telemedicine encounter rules several years ago, making it possible for rural hospitals to accept the credentialing process of the health center where the specialist is located. However, other criteria must be met for the telehealth encounter to occur.

Differing credentialing processes are challenging for doctors who practice telehealth, agreed telemedicine hospitalist Dr. Dana Giarrizzi of Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta, which provides hospitalist services to hospitals and health systems nationwide via telehealth.

“The credentialing is certainly difficult at times,” Dr. Giarrizzi said. “It is a long process and sometimes requires fingerprints, taking exams, and other involved steps. It is very time consuming, and each state and certainly [each] facility can have different criteria, which makes it hard to know.”

To ensure its doctors are meeting the requirements of each facility, Eagle Hospital Physicians has its own credentialing department that works with hospitals to learn their processes and verify its physicians adhere to the rules, Dr. Giarrizzi said.

Preventing telemedicine lawsuits

To mitigate potential risks of telemedicine, doctors should clearly define protocols for use of webcams and Web-based portals and ensure such systems are secure, Mr. Cahill said. Take time to learn what constitutes the practice of medicine in each state in which doctors are delivering care, and carefully adhere to those rules, he added. Physicians also should have mechanisms in place to protect the privacy of individuals who do not want to be seen on camera, such as staff or family members.

It’s also critical to confer with malpractice insurance providers to confirm that telehealth services are covered, said Mr. Quashie, a member of the Legal Resource Team at CTeL. If telemedicine is not covered, physicians may want to buy a separate policy from another company that covers telehealth.

If physicians opt to work for a larger telemedicine company, they should check what controls the company has in place to protect them from lawsuits.

For example, national telemedicine company Teladoc has numerous safeguards in place to promote quality care and protect its doctors from claims, said Dr. Henry DePhillips, Teladoc’s chief medical officer. The company has National Committee for Quality Assurance certification, along with proprietary, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for its physicians, a peer-review quality assurance committee, and regular data and medical reviews, Dr. DePhillips said. Teladoc is close to surpassing its 1-millionth consult and has not had a single claim filed in its history, he added.

Dr. DePhillips stressed that telemedicine is not a separate practice of medicine, and that best practices should remain the same, no matter the location.

“The bottom line is the standard of care for the diagnosis and treatment of these medical problems is the standard of care regardless whether you’re seeing the person in person, in an urgent care center, or through a secure video,” Dr. DePhillips said. “The doctor has to be able to comply with the standard of care and make a decision [about] whether that setting and that equipment at his or her disposal are adequate to make an accurate diagnosis and a medically appropriate treatment plan.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Physicians who practice telemedicine have a lot to consider, including state laws, payment issues, and licensing regulations. But one overlooked area may pose the greatest risk of all: medical liability.

As the practice of telemedicine continues to grow, so do the legal risks associated with virtual care, said Dr. Joseph P. McMenamin, an emergency physician and health law defense attorney based in Richmond, Va.

“With good reason, there is a concern that as this form of care expands, claims against physicians will increase,” Dr. McMenamin said. “That’s almost inevitable, given how our society looks at litigation and how willing we are to sue our doctors. If you’re a plaintiffs’ attorney, you might be attracted to cases of this kind – partly because jurors may fear the unknown, and they may view [telemedicine] with some concern and suspicion.”

Telemedicine can fuel a wide spectrum of legal dangers, including malpractice, product liability claims, data exposure, and credentialing risks. Making matters more complicated: No uniform standard of care exists for telemedicine when it comes to medical malpractice, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney who specializes in telemedicine and e-health practices.

“There are a lot of unanswered questions, including the prevailing standard of care,” Mr. Quashie explained. “Can we use the standard of care that we use for services provided in person for telehealth consults? Informed consent – does that process need to change? There are a lot of unanswered issues, which can only be resolved after a number of cases” are decided in the courts.

Physicians who practice telemedicine should consider legal risks associated with patient and staff privacy, inaccuracies in self-reporting, and symptoms that are more accurately diagnosed in person, said Richard F. Cahill, vice president and associate general counsel for the Doctors Company, a national medical liability insurer.

During 2007-2014, the Doctors Company had 11 claims that closed related to telemedicine, according to data provided by Mr. Cahill.

The majority of claims resulted from the remote reading of x-rays and other films by health providers, usually from home, and the remote reading of fetal monitor strips by physicians when outside of the hospital. Two of the cases were associated with attempts to diagnose a patient via telemedicine. Of the claims, six were diagnosis related, two alleged delay in treatment, two were related to improper performance of treatment, and one was associated with failure to order medication.

“The challenges of remote communications made it difficult to formulate the correct diagnosis due to limitations of radiology resolution, delayed readings of radiographs, or limits on fetal monitor strips,” said Darrell Ranum, vice president of patient safety and risk management for the Doctors Company. “Delays in treatment were closely related to delayed diagnosis. Radiologists did not receive a request for an interpretation, or they did not know that it was an emergency, so they did not provide a rapid turnaround report.”

While telemedicine claims have been low so far, a rise in the number of patient contacts, regardless of modality, may increase the risk of adverse consequences, Mr. Cahill cautioned.

“Because telemedicine is relatively new, and it takes 3-4 years for a claim to work its way through the system, we may see more cases in the future in which telemedicine is a factor,” he predicted.

Other lawsuits could arise from claims that physicians had access to telemedicine but failed to use the technology to properly treat a patient, Mr. Quashie said. Product liability claims also pose a threat, added Dr. McMenamin, who is part of the Legal Resource Team at the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law (CTeL). Such accusations stem from equipment that malfunctioned or failed to work as indicated.

Varying credentialing rules also can trip up doctors who work virtually. Physicians at a large academic medical center, for example, could face trouble if they aren’t credentialed at the small rural hospital where a patient is located, Dr. McMenamin said. He noted that Medicare modified its telemedicine encounter rules several years ago, making it possible for rural hospitals to accept the credentialing process of the health center where the specialist is located. However, other criteria must be met for the telehealth encounter to occur.

Differing credentialing processes are challenging for doctors who practice telehealth, agreed telemedicine hospitalist Dr. Dana Giarrizzi of Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta, which provides hospitalist services to hospitals and health systems nationwide via telehealth.

“The credentialing is certainly difficult at times,” Dr. Giarrizzi said. “It is a long process and sometimes requires fingerprints, taking exams, and other involved steps. It is very time consuming, and each state and certainly [each] facility can have different criteria, which makes it hard to know.”

To ensure its doctors are meeting the requirements of each facility, Eagle Hospital Physicians has its own credentialing department that works with hospitals to learn their processes and verify its physicians adhere to the rules, Dr. Giarrizzi said.

Preventing telemedicine lawsuits

To mitigate potential risks of telemedicine, doctors should clearly define protocols for use of webcams and Web-based portals and ensure such systems are secure, Mr. Cahill said. Take time to learn what constitutes the practice of medicine in each state in which doctors are delivering care, and carefully adhere to those rules, he added. Physicians also should have mechanisms in place to protect the privacy of individuals who do not want to be seen on camera, such as staff or family members.

It’s also critical to confer with malpractice insurance providers to confirm that telehealth services are covered, said Mr. Quashie, a member of the Legal Resource Team at CTeL. If telemedicine is not covered, physicians may want to buy a separate policy from another company that covers telehealth.

If physicians opt to work for a larger telemedicine company, they should check what controls the company has in place to protect them from lawsuits.

For example, national telemedicine company Teladoc has numerous safeguards in place to promote quality care and protect its doctors from claims, said Dr. Henry DePhillips, Teladoc’s chief medical officer. The company has National Committee for Quality Assurance certification, along with proprietary, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for its physicians, a peer-review quality assurance committee, and regular data and medical reviews, Dr. DePhillips said. Teladoc is close to surpassing its 1-millionth consult and has not had a single claim filed in its history, he added.

Dr. DePhillips stressed that telemedicine is not a separate practice of medicine, and that best practices should remain the same, no matter the location.

“The bottom line is the standard of care for the diagnosis and treatment of these medical problems is the standard of care regardless whether you’re seeing the person in person, in an urgent care center, or through a secure video,” Dr. DePhillips said. “The doctor has to be able to comply with the standard of care and make a decision [about] whether that setting and that equipment at his or her disposal are adequate to make an accurate diagnosis and a medically appropriate treatment plan.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Physicians who practice telemedicine have a lot to consider, including state laws, payment issues, and licensing regulations. But one overlooked area may pose the greatest risk of all: medical liability.

As the practice of telemedicine continues to grow, so do the legal risks associated with virtual care, said Dr. Joseph P. McMenamin, an emergency physician and health law defense attorney based in Richmond, Va.

“With good reason, there is a concern that as this form of care expands, claims against physicians will increase,” Dr. McMenamin said. “That’s almost inevitable, given how our society looks at litigation and how willing we are to sue our doctors. If you’re a plaintiffs’ attorney, you might be attracted to cases of this kind – partly because jurors may fear the unknown, and they may view [telemedicine] with some concern and suspicion.”

Telemedicine can fuel a wide spectrum of legal dangers, including malpractice, product liability claims, data exposure, and credentialing risks. Making matters more complicated: No uniform standard of care exists for telemedicine when it comes to medical malpractice, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney who specializes in telemedicine and e-health practices.

“There are a lot of unanswered questions, including the prevailing standard of care,” Mr. Quashie explained. “Can we use the standard of care that we use for services provided in person for telehealth consults? Informed consent – does that process need to change? There are a lot of unanswered issues, which can only be resolved after a number of cases” are decided in the courts.

Physicians who practice telemedicine should consider legal risks associated with patient and staff privacy, inaccuracies in self-reporting, and symptoms that are more accurately diagnosed in person, said Richard F. Cahill, vice president and associate general counsel for the Doctors Company, a national medical liability insurer.

During 2007-2014, the Doctors Company had 11 claims that closed related to telemedicine, according to data provided by Mr. Cahill.

The majority of claims resulted from the remote reading of x-rays and other films by health providers, usually from home, and the remote reading of fetal monitor strips by physicians when outside of the hospital. Two of the cases were associated with attempts to diagnose a patient via telemedicine. Of the claims, six were diagnosis related, two alleged delay in treatment, two were related to improper performance of treatment, and one was associated with failure to order medication.

“The challenges of remote communications made it difficult to formulate the correct diagnosis due to limitations of radiology resolution, delayed readings of radiographs, or limits on fetal monitor strips,” said Darrell Ranum, vice president of patient safety and risk management for the Doctors Company. “Delays in treatment were closely related to delayed diagnosis. Radiologists did not receive a request for an interpretation, or they did not know that it was an emergency, so they did not provide a rapid turnaround report.”

While telemedicine claims have been low so far, a rise in the number of patient contacts, regardless of modality, may increase the risk of adverse consequences, Mr. Cahill cautioned.

“Because telemedicine is relatively new, and it takes 3-4 years for a claim to work its way through the system, we may see more cases in the future in which telemedicine is a factor,” he predicted.

Other lawsuits could arise from claims that physicians had access to telemedicine but failed to use the technology to properly treat a patient, Mr. Quashie said. Product liability claims also pose a threat, added Dr. McMenamin, who is part of the Legal Resource Team at the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law (CTeL). Such accusations stem from equipment that malfunctioned or failed to work as indicated.

Varying credentialing rules also can trip up doctors who work virtually. Physicians at a large academic medical center, for example, could face trouble if they aren’t credentialed at the small rural hospital where a patient is located, Dr. McMenamin said. He noted that Medicare modified its telemedicine encounter rules several years ago, making it possible for rural hospitals to accept the credentialing process of the health center where the specialist is located. However, other criteria must be met for the telehealth encounter to occur.

Differing credentialing processes are challenging for doctors who practice telehealth, agreed telemedicine hospitalist Dr. Dana Giarrizzi of Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta, which provides hospitalist services to hospitals and health systems nationwide via telehealth.

“The credentialing is certainly difficult at times,” Dr. Giarrizzi said. “It is a long process and sometimes requires fingerprints, taking exams, and other involved steps. It is very time consuming, and each state and certainly [each] facility can have different criteria, which makes it hard to know.”

To ensure its doctors are meeting the requirements of each facility, Eagle Hospital Physicians has its own credentialing department that works with hospitals to learn their processes and verify its physicians adhere to the rules, Dr. Giarrizzi said.

Preventing telemedicine lawsuits

To mitigate potential risks of telemedicine, doctors should clearly define protocols for use of webcams and Web-based portals and ensure such systems are secure, Mr. Cahill said. Take time to learn what constitutes the practice of medicine in each state in which doctors are delivering care, and carefully adhere to those rules, he added. Physicians also should have mechanisms in place to protect the privacy of individuals who do not want to be seen on camera, such as staff or family members.

It’s also critical to confer with malpractice insurance providers to confirm that telehealth services are covered, said Mr. Quashie, a member of the Legal Resource Team at CTeL. If telemedicine is not covered, physicians may want to buy a separate policy from another company that covers telehealth.

If physicians opt to work for a larger telemedicine company, they should check what controls the company has in place to protect them from lawsuits.

For example, national telemedicine company Teladoc has numerous safeguards in place to promote quality care and protect its doctors from claims, said Dr. Henry DePhillips, Teladoc’s chief medical officer. The company has National Committee for Quality Assurance certification, along with proprietary, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for its physicians, a peer-review quality assurance committee, and regular data and medical reviews, Dr. DePhillips said. Teladoc is close to surpassing its 1-millionth consult and has not had a single claim filed in its history, he added.

Dr. DePhillips stressed that telemedicine is not a separate practice of medicine, and that best practices should remain the same, no matter the location.

“The bottom line is the standard of care for the diagnosis and treatment of these medical problems is the standard of care regardless whether you’re seeing the person in person, in an urgent care center, or through a secure video,” Dr. DePhillips said. “The doctor has to be able to comply with the standard of care and make a decision [about] whether that setting and that equipment at his or her disposal are adequate to make an accurate diagnosis and a medically appropriate treatment plan.”

On Twitter @legal_med

GAO: Physicians, hospitals struggle to achieve EHR interoperability

Physicians and health care organizations are struggling to achieve interoperability, the exchange of data between their electronic health records systems, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report.

The report comes as more federal lawmakers press the Obama administration to slow the start of the third stage of Meaningful Use requirements for EHRs.

The GAO interviewed 18 private companies working to enhance the interoperability of electronic health records at the request of Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), chair of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions.

In its report, the GAO found five key challenges that are preventing EHR interoperability:

• Insufficiencies in standards for EHR interoperability.

• Variations in states’ privacy rules.

• Difficulties in accurately matching patients’ health records.

• The costs associated with interoperability.

• A need for governance and trust among the providers and organizations using EHRs.

Many of the organizations surveyed said that the Meaningful Use requirements, passed as part of the 2009 federal stimulus and being implemented in stages, focus more on rules than on the criteria necessary to test the various systems’ ability to interoperate.

Three of the industry representatives surveyed suggested that the Obama administration should at least amend the EHR incentives law to focus on testing systems’ interoperability, while five others called for suspending or scrapping the law altogether.

“We are glad to see the GAO shining a light on the problem,” Dan Haley, Athena Health senior vice president and general counsel, said in an interview. Athena Health was not among those surveyed for the report.

“Nobody who lives and works in the 21st century can possibly dispute the proposition that information technology has the potential to vastly improve the quality and efficiency of health care delivery,” Mr. Haley noted. “Unfortunately, the Meaningful Use program, while well intentioned, has become burdened by granular requirements that impede rather than enhance care providers’ ability to maximize that potential, and do nothing to improve the interoperability of disparate technology platforms.”

Meanwhile, 116 members of the U.S. House of Representatives have signed a letter addressed to both Office of Management and Budget Director Shaun Donovan and U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell, asking them to delay the third stage of the law’s implementation until there’s a clearer picture of what metrics will be in the recently passed Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), which have just opened up for public comment.

“It’s time that we focus on interoperability instead of rulemaking to ensure that these products work for our nation’s providers,” Rep. Renee Ellmers (R-N.C.) said in a statement. “If the administration dives into Stage 3 prematurely, we only stand to aggravate providers and vendors who have already experienced ample challenges in meeting attestation deadlines.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sent the final rule for Stage 3 of Meaningful Use to the Office of Management and Budget in September. The next stage is set to take effect in 2017.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Physicians and health care organizations are struggling to achieve interoperability, the exchange of data between their electronic health records systems, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report.

The report comes as more federal lawmakers press the Obama administration to slow the start of the third stage of Meaningful Use requirements for EHRs.

The GAO interviewed 18 private companies working to enhance the interoperability of electronic health records at the request of Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), chair of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions.

In its report, the GAO found five key challenges that are preventing EHR interoperability:

• Insufficiencies in standards for EHR interoperability.

• Variations in states’ privacy rules.

• Difficulties in accurately matching patients’ health records.

• The costs associated with interoperability.

• A need for governance and trust among the providers and organizations using EHRs.

Many of the organizations surveyed said that the Meaningful Use requirements, passed as part of the 2009 federal stimulus and being implemented in stages, focus more on rules than on the criteria necessary to test the various systems’ ability to interoperate.

Three of the industry representatives surveyed suggested that the Obama administration should at least amend the EHR incentives law to focus on testing systems’ interoperability, while five others called for suspending or scrapping the law altogether.

“We are glad to see the GAO shining a light on the problem,” Dan Haley, Athena Health senior vice president and general counsel, said in an interview. Athena Health was not among those surveyed for the report.

“Nobody who lives and works in the 21st century can possibly dispute the proposition that information technology has the potential to vastly improve the quality and efficiency of health care delivery,” Mr. Haley noted. “Unfortunately, the Meaningful Use program, while well intentioned, has become burdened by granular requirements that impede rather than enhance care providers’ ability to maximize that potential, and do nothing to improve the interoperability of disparate technology platforms.”

Meanwhile, 116 members of the U.S. House of Representatives have signed a letter addressed to both Office of Management and Budget Director Shaun Donovan and U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell, asking them to delay the third stage of the law’s implementation until there’s a clearer picture of what metrics will be in the recently passed Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), which have just opened up for public comment.

“It’s time that we focus on interoperability instead of rulemaking to ensure that these products work for our nation’s providers,” Rep. Renee Ellmers (R-N.C.) said in a statement. “If the administration dives into Stage 3 prematurely, we only stand to aggravate providers and vendors who have already experienced ample challenges in meeting attestation deadlines.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sent the final rule for Stage 3 of Meaningful Use to the Office of Management and Budget in September. The next stage is set to take effect in 2017.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Physicians and health care organizations are struggling to achieve interoperability, the exchange of data between their electronic health records systems, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report.

The report comes as more federal lawmakers press the Obama administration to slow the start of the third stage of Meaningful Use requirements for EHRs.

The GAO interviewed 18 private companies working to enhance the interoperability of electronic health records at the request of Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), chair of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions.

In its report, the GAO found five key challenges that are preventing EHR interoperability:

• Insufficiencies in standards for EHR interoperability.

• Variations in states’ privacy rules.

• Difficulties in accurately matching patients’ health records.

• The costs associated with interoperability.

• A need for governance and trust among the providers and organizations using EHRs.

Many of the organizations surveyed said that the Meaningful Use requirements, passed as part of the 2009 federal stimulus and being implemented in stages, focus more on rules than on the criteria necessary to test the various systems’ ability to interoperate.

Three of the industry representatives surveyed suggested that the Obama administration should at least amend the EHR incentives law to focus on testing systems’ interoperability, while five others called for suspending or scrapping the law altogether.

“We are glad to see the GAO shining a light on the problem,” Dan Haley, Athena Health senior vice president and general counsel, said in an interview. Athena Health was not among those surveyed for the report.

“Nobody who lives and works in the 21st century can possibly dispute the proposition that information technology has the potential to vastly improve the quality and efficiency of health care delivery,” Mr. Haley noted. “Unfortunately, the Meaningful Use program, while well intentioned, has become burdened by granular requirements that impede rather than enhance care providers’ ability to maximize that potential, and do nothing to improve the interoperability of disparate technology platforms.”

Meanwhile, 116 members of the U.S. House of Representatives have signed a letter addressed to both Office of Management and Budget Director Shaun Donovan and U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell, asking them to delay the third stage of the law’s implementation until there’s a clearer picture of what metrics will be in the recently passed Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), which have just opened up for public comment.

“It’s time that we focus on interoperability instead of rulemaking to ensure that these products work for our nation’s providers,” Rep. Renee Ellmers (R-N.C.) said in a statement. “If the administration dives into Stage 3 prematurely, we only stand to aggravate providers and vendors who have already experienced ample challenges in meeting attestation deadlines.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sent the final rule for Stage 3 of Meaningful Use to the Office of Management and Budget in September. The next stage is set to take effect in 2017.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Hospital Groups Might Do Better Without Daytime Admission Shifts, Morning Meetings

You shouldn’t maintain things that do not deliver the value you anticipated when you first put them in place. For example, I thought Netflix streaming would be terrific, but I have used it so infrequently that it probably costs me $50 per movie or show watched. I should probably dump it.

Your hospitalist group might have some operational practices that are not as valuable as they seem and could be replaced with something better. For many groups, this might include doing away with a separate daytime admitter shift and a morning meeting to distribute the overnight admissions.

Daytime Admission Shift

My experience is that hospitalist groups with more than about five daytime doctors almost always have a day-shift person dedicated to seeing new admissions. In most cases, this procedure is implemented with the idea of reducing the stress of other day-shift doctors, who don’t have to interrupt rounds to admit a new patient. Some see a dedicated admitter as a tool to improve ED throughput, because this doctor isn’t tied up with rounds and can immediately start seeing a new admission.

I think an admitter shift does deliver both of these benefits, but its costs make it suboptimal in most settings. For example, a single admitter will impede ED throughput any time more than one new admission is waiting to be seen, and for most groups that will be much of the day. In fact, improved ED throughput is best achieved by having many hospitalists available for admissions, not just a single admitter. (There are many other factors influencing ED throughput, such as whether ED doctors simply send patients to their “floor” bed prior to being seen by a hospitalist. But for this article, I’m just considering the influence of a dedicated admitter.)

I think “silo-ing” work into different roles, such as separating rounding and admitting, makes it more difficult to ensure that each is always working productively. There are likely to be times when the admitter has little or nothing to do, even though the rounders are very busy. Or perhaps the rounders aren’t very busy, but the admitter has just been asked to admit four ED patients at the same time.

While protecting rounders from the stress of admissions is valuable, it comes at the cost of a net increase in hospitalist work, because a new doctor must get to know the patient on the day following admission. And this admitter-to-rounder handoff serves as another opportunity for errors—and probably lowers patient satisfaction.

I think most groups should consider moving the admitter shift into an additional rounder position, dividing admissions across all of the doctors working during the daytime. For example, a group that has six rounders and a separate admitter would change to seven rounders, each available to admit every seventh daytime admission. Each would bear the meaningful stress of having rounds interrupted to admit a new patient, but accepting every seventh daytime admission shouldn’t be too difficult on most days.

Don’t forget that eliminating the admitter means that the list of new patients you take on each morning will be shorter. Mornings may be a little less stressful.

A.M. Distribution

The daytime doctors at many hospitalist groups meet each morning to discuss how the new admissions from the prior night (or even the last 24 hours) will be distributed. Or perhaps one person, sometimes a nurse or clerical staff, arrives very early each day to do this.

Although it might take some careful planning, I think most groups that use this sort of morning distribution should abandon it for a better system. Consider a group in which all six daytime doctors spend an average of 20 minutes distributing patients each morning. Twenty minutes (0.33 hours) times six doctors times 365 days comes to 730 hours annually.

Assuming these doctors are compensated at typical rates, the practice is spending more than $100,000 annually just so the doctors can distribute patients each morning. On top of this, nurses and others at the hospital are usually delayed in learning which daytime hospitalist is caring for each patient. These costs seem unreasonably high.

An alternative is to develop a system by which any admitter, such as a night doctor, who will not be providing subsequent care to a patient can identify by name the doctor who will be providing that care. During the admission encounter, the admitter can tell patient/family, “Dr. Boswell will be taking over your care starting tomorrow. He’s a great guy and has been named one of Portland’s best doctors.” This seems so much better than saying, “One of my partners will be taking over tomorrow. I don’t know which of my partners it will be, but they’re all good doctors.” And Dr. Boswell’s name can be entered into the attending physician field of the EHR so that all hospital staff will know without delay.

MedAptus has recently launched software they call “Assign” that may be able to replace the morning meeting and automate assigning new admissions to each hospitalist. I haven’t seen it in operation, so I can’t speak for its effectiveness, but it might be worthwhile for some groups.

Practical Considerations

The changes I’ve described above might not be optimal for every group, and they may take meaningful work to implement. But I don’t think the difficulty of these things is the biggest barrier. The biggest barrier is probably just inertia in most cases, the same reason I’m still a Netflix streaming subscriber even though I almost never watch it. I did, however, really enjoy the Nexflix original series Lilyhammer.

You shouldn’t maintain things that do not deliver the value you anticipated when you first put them in place. For example, I thought Netflix streaming would be terrific, but I have used it so infrequently that it probably costs me $50 per movie or show watched. I should probably dump it.

Your hospitalist group might have some operational practices that are not as valuable as they seem and could be replaced with something better. For many groups, this might include doing away with a separate daytime admitter shift and a morning meeting to distribute the overnight admissions.

Daytime Admission Shift