User login

The Hospitalist only

Consent and DNR orders

Question: Paramedics brought an unconscious 70-year-old man to a Florida hospital emergency department. The patient had the words “Do Not Resuscitate” tattooed onto his chest. No one accompanied him, and he had no identifications on his person. His blood alcohol level was elevated, and a few hours after his arrival, he lapsed into severe metabolic acidosis and hypotensive shock. The treating team decided to enter a DNR order, and the patient died shortly thereafter without benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Which of the following is best?

A. An ethics consult may suggest honoring the patient’s DNR wishes, as it is reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference.

B. It has been said, but remains debatable, that tattoos might represent “permanent reminders of regretted decisions made while the person was intoxicated.”

C. An earlier case report in the literature cautioned that the tattooed expression of a DNR request did not reflect that particular patient’s current wishes.

D. If this patient’s Florida Department of Health out-of-hospital DNR order confirms his DNR preference, then it is appropriate to withhold resuscitation.

E. All are correct.

ANSWER: E. The above hypothetical situation is modified from a recent case report in the correspondence section of the New England Journal of Medicine.1 It can be read as offering a sharp and dramatic focus on the issue of consent surrounding decisions to withhold CPR.

In 1983, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine supported DNR protocols (“no code”) based on three value considerations: self-determination, well-being, and equity.2

The physician is obligated to discuss with the patient or surrogate the procedure, risks, and benefits of CPR so that an informed choice can be made. DNR means that, in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest, no CPR efforts would be undertaken. DNR orders are not exclusive to the in-hospital setting, as some states, for example, Florida and Texas, have also enacted statutes that allow such orders to be valid outside the hospital.

Critics lament that problems – many surrounding the consent issue – continue to plague DNR orders.3 Discussions are often vague, and they may not meet the threshold of informed consent requirements, because they frequently omit risks and complications. A resident, rather than the attending physician, typically performs this important task. This is compounded by ill-timed discussions and wrong assumptions about patients’ preferences, which may in fact be ignored.4

Physicians sometimes extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments. Or, they perform CPR in contraindicated situations such as terminal illnesses, where death is expected, which amounts to “a positive violation of an individual’s right to die with dignity.” In some situations, physicians are known to override a patient’s DNR request.

Take the operating-room conundrum. There, the immediate availability of drugs, heightened skills, and in-place procedures significantly improve survival following a cardiopulmonary arrest. Studies show a 50% survival rate, versus 8%-14% elsewhere in the hospital. A Swedish study showed that 65% of the patients who had a cardiac arrest perioperatively were successfully resuscitated. When anesthesia caused the arrest, for example, esophageal intubation, disconnection from mechanical ventilation, or prolonged exposure to high concentrations of anesthetics, the recovery rate jumped to 92%.

Terminally ill patients typically disavow CPR when choosing a palliative course of action. However, surgery can be a part of palliation. In 1991, approximately 15% of patients with DNR orders had a surgical procedure, with most interventions targeting comfort and/or nursing care. When a terminally ill patient with a DNR order undergoes surgery, how should physicians deal with the patient’s no-code status, especially if an iatrogenic cardiac arrest should occur?

Because overriding a patient’s DNR wish violates the right of self-determination, a reasonable rule is to require the surgeon and/or anesthesiologist to discuss preoperatively the increased risk of a cardiac arrest during surgery, as well as the markedly improved chance of a successful resuscitation. The patient will then decide whether to retain his/her original DNR intent, or to suspend its execution in the perioperative period.5

What about iatrogenesis?

In 1999, David Casarett, MD, and Lainie F. Ross, MD, PhD, assessed whether physicians were more likely to override a DNR order if a hypothetical cardiac arrest was caused iatrogenically.6 Their survey revealed that 69% of physicians were very likely to do so. The authors suggested three explanations: 1) concern for malpractice litigation, 2) feelings of guilt or responsibility, and 3) the belief that patients do not consider the possibility of an iatrogenic cardiac arrest when they consent to a DNR order. Physicians may also believe a “properly negotiated DNR order does not apply to all foreseeable circumstances.”

However, some ethicists believe that an iatrogenic mishap does not make it permissible to override a patient’s prior refusal of treatment, because errors should not alter ethical obligations to respect a patient’s wishes to forgo treatment, including CPR.

Can a DNR order exist if it is against a patient’s wishes?7 In Gilgunn v. Massachusetts General Hospital, a 71-year-old diabetic woman with heart disease, breast cancer, and a hip fracture suffered two grand mal seizures and lapsed into a coma.8 Her daughter was the surrogate decision maker, and she made it clear that her mother always said she wanted everything done. After several weeks, the physicians decided that further treatment would be futile.

The chair of the ethics committee felt that the daughter’s opinion was not relevant because CPR was not a genuine therapeutic option and would be “medically contraindicated, inhumane, and unethical.” Accordingly, the attending physician entered a DNR order despite strong protest from the daughter. The patient died shortly thereafter without receiving CPR, and the daughter filed a negligence lawsuit against the hospital.

Still, there are state and federal statutes touching on DNR orders that warrant careful attention. For example, New York Public Health Law Section 2962, paragraph 1, states: “Every person admitted to a hospital shall be presumed to consent to the administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest, unless there is consent to the issuance of an order not to resuscitate ...” This raises the question as to whether it is ever legally permissible in New York to enter a unilateral DNR order against the wishes of the patient.

And the federal “anti-dumping” law governing emergency treatment, widely known as EMTALA (Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act), requires all emergency departments to provide treatment necessary to prevent the material deterioration of the individual’s condition. This would always include the use of CPR unless specifically rejected by the patient or surrogate, as the law does not contain a “standard of care” or “futility” exception.9

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 30;377(22):2192-3.

2. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1983.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jul;26(7):791-7.

4. JAMA. 1995 Nov 22-29;274(20):1591-8.

5. Hawaii Med J. 2001 Mar;60(3):64-7.

6. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 26;336(26):1908-10.

7. Tan SY. Futility and DNR Orders. Internal Medicine News, March 21, 2014.

8. Gilgunn v. Mass. General Hosp. No. 92-4820 (Mass. Super Ct. Apr. 21, 1995).

9. In re Baby K, 16 F.3d 590 (4th Cir. 1994).

Question: Paramedics brought an unconscious 70-year-old man to a Florida hospital emergency department. The patient had the words “Do Not Resuscitate” tattooed onto his chest. No one accompanied him, and he had no identifications on his person. His blood alcohol level was elevated, and a few hours after his arrival, he lapsed into severe metabolic acidosis and hypotensive shock. The treating team decided to enter a DNR order, and the patient died shortly thereafter without benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Which of the following is best?

A. An ethics consult may suggest honoring the patient’s DNR wishes, as it is reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference.

B. It has been said, but remains debatable, that tattoos might represent “permanent reminders of regretted decisions made while the person was intoxicated.”

C. An earlier case report in the literature cautioned that the tattooed expression of a DNR request did not reflect that particular patient’s current wishes.

D. If this patient’s Florida Department of Health out-of-hospital DNR order confirms his DNR preference, then it is appropriate to withhold resuscitation.

E. All are correct.

ANSWER: E. The above hypothetical situation is modified from a recent case report in the correspondence section of the New England Journal of Medicine.1 It can be read as offering a sharp and dramatic focus on the issue of consent surrounding decisions to withhold CPR.

In 1983, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine supported DNR protocols (“no code”) based on three value considerations: self-determination, well-being, and equity.2

The physician is obligated to discuss with the patient or surrogate the procedure, risks, and benefits of CPR so that an informed choice can be made. DNR means that, in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest, no CPR efforts would be undertaken. DNR orders are not exclusive to the in-hospital setting, as some states, for example, Florida and Texas, have also enacted statutes that allow such orders to be valid outside the hospital.

Critics lament that problems – many surrounding the consent issue – continue to plague DNR orders.3 Discussions are often vague, and they may not meet the threshold of informed consent requirements, because they frequently omit risks and complications. A resident, rather than the attending physician, typically performs this important task. This is compounded by ill-timed discussions and wrong assumptions about patients’ preferences, which may in fact be ignored.4

Physicians sometimes extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments. Or, they perform CPR in contraindicated situations such as terminal illnesses, where death is expected, which amounts to “a positive violation of an individual’s right to die with dignity.” In some situations, physicians are known to override a patient’s DNR request.

Take the operating-room conundrum. There, the immediate availability of drugs, heightened skills, and in-place procedures significantly improve survival following a cardiopulmonary arrest. Studies show a 50% survival rate, versus 8%-14% elsewhere in the hospital. A Swedish study showed that 65% of the patients who had a cardiac arrest perioperatively were successfully resuscitated. When anesthesia caused the arrest, for example, esophageal intubation, disconnection from mechanical ventilation, or prolonged exposure to high concentrations of anesthetics, the recovery rate jumped to 92%.

Terminally ill patients typically disavow CPR when choosing a palliative course of action. However, surgery can be a part of palliation. In 1991, approximately 15% of patients with DNR orders had a surgical procedure, with most interventions targeting comfort and/or nursing care. When a terminally ill patient with a DNR order undergoes surgery, how should physicians deal with the patient’s no-code status, especially if an iatrogenic cardiac arrest should occur?

Because overriding a patient’s DNR wish violates the right of self-determination, a reasonable rule is to require the surgeon and/or anesthesiologist to discuss preoperatively the increased risk of a cardiac arrest during surgery, as well as the markedly improved chance of a successful resuscitation. The patient will then decide whether to retain his/her original DNR intent, or to suspend its execution in the perioperative period.5

What about iatrogenesis?

In 1999, David Casarett, MD, and Lainie F. Ross, MD, PhD, assessed whether physicians were more likely to override a DNR order if a hypothetical cardiac arrest was caused iatrogenically.6 Their survey revealed that 69% of physicians were very likely to do so. The authors suggested three explanations: 1) concern for malpractice litigation, 2) feelings of guilt or responsibility, and 3) the belief that patients do not consider the possibility of an iatrogenic cardiac arrest when they consent to a DNR order. Physicians may also believe a “properly negotiated DNR order does not apply to all foreseeable circumstances.”

However, some ethicists believe that an iatrogenic mishap does not make it permissible to override a patient’s prior refusal of treatment, because errors should not alter ethical obligations to respect a patient’s wishes to forgo treatment, including CPR.

Can a DNR order exist if it is against a patient’s wishes?7 In Gilgunn v. Massachusetts General Hospital, a 71-year-old diabetic woman with heart disease, breast cancer, and a hip fracture suffered two grand mal seizures and lapsed into a coma.8 Her daughter was the surrogate decision maker, and she made it clear that her mother always said she wanted everything done. After several weeks, the physicians decided that further treatment would be futile.

The chair of the ethics committee felt that the daughter’s opinion was not relevant because CPR was not a genuine therapeutic option and would be “medically contraindicated, inhumane, and unethical.” Accordingly, the attending physician entered a DNR order despite strong protest from the daughter. The patient died shortly thereafter without receiving CPR, and the daughter filed a negligence lawsuit against the hospital.

Still, there are state and federal statutes touching on DNR orders that warrant careful attention. For example, New York Public Health Law Section 2962, paragraph 1, states: “Every person admitted to a hospital shall be presumed to consent to the administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest, unless there is consent to the issuance of an order not to resuscitate ...” This raises the question as to whether it is ever legally permissible in New York to enter a unilateral DNR order against the wishes of the patient.

And the federal “anti-dumping” law governing emergency treatment, widely known as EMTALA (Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act), requires all emergency departments to provide treatment necessary to prevent the material deterioration of the individual’s condition. This would always include the use of CPR unless specifically rejected by the patient or surrogate, as the law does not contain a “standard of care” or “futility” exception.9

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 30;377(22):2192-3.

2. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1983.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jul;26(7):791-7.

4. JAMA. 1995 Nov 22-29;274(20):1591-8.

5. Hawaii Med J. 2001 Mar;60(3):64-7.

6. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 26;336(26):1908-10.

7. Tan SY. Futility and DNR Orders. Internal Medicine News, March 21, 2014.

8. Gilgunn v. Mass. General Hosp. No. 92-4820 (Mass. Super Ct. Apr. 21, 1995).

9. In re Baby K, 16 F.3d 590 (4th Cir. 1994).

Question: Paramedics brought an unconscious 70-year-old man to a Florida hospital emergency department. The patient had the words “Do Not Resuscitate” tattooed onto his chest. No one accompanied him, and he had no identifications on his person. His blood alcohol level was elevated, and a few hours after his arrival, he lapsed into severe metabolic acidosis and hypotensive shock. The treating team decided to enter a DNR order, and the patient died shortly thereafter without benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Which of the following is best?

A. An ethics consult may suggest honoring the patient’s DNR wishes, as it is reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference.

B. It has been said, but remains debatable, that tattoos might represent “permanent reminders of regretted decisions made while the person was intoxicated.”

C. An earlier case report in the literature cautioned that the tattooed expression of a DNR request did not reflect that particular patient’s current wishes.

D. If this patient’s Florida Department of Health out-of-hospital DNR order confirms his DNR preference, then it is appropriate to withhold resuscitation.

E. All are correct.

ANSWER: E. The above hypothetical situation is modified from a recent case report in the correspondence section of the New England Journal of Medicine.1 It can be read as offering a sharp and dramatic focus on the issue of consent surrounding decisions to withhold CPR.

In 1983, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine supported DNR protocols (“no code”) based on three value considerations: self-determination, well-being, and equity.2

The physician is obligated to discuss with the patient or surrogate the procedure, risks, and benefits of CPR so that an informed choice can be made. DNR means that, in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest, no CPR efforts would be undertaken. DNR orders are not exclusive to the in-hospital setting, as some states, for example, Florida and Texas, have also enacted statutes that allow such orders to be valid outside the hospital.

Critics lament that problems – many surrounding the consent issue – continue to plague DNR orders.3 Discussions are often vague, and they may not meet the threshold of informed consent requirements, because they frequently omit risks and complications. A resident, rather than the attending physician, typically performs this important task. This is compounded by ill-timed discussions and wrong assumptions about patients’ preferences, which may in fact be ignored.4

Physicians sometimes extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments. Or, they perform CPR in contraindicated situations such as terminal illnesses, where death is expected, which amounts to “a positive violation of an individual’s right to die with dignity.” In some situations, physicians are known to override a patient’s DNR request.

Take the operating-room conundrum. There, the immediate availability of drugs, heightened skills, and in-place procedures significantly improve survival following a cardiopulmonary arrest. Studies show a 50% survival rate, versus 8%-14% elsewhere in the hospital. A Swedish study showed that 65% of the patients who had a cardiac arrest perioperatively were successfully resuscitated. When anesthesia caused the arrest, for example, esophageal intubation, disconnection from mechanical ventilation, or prolonged exposure to high concentrations of anesthetics, the recovery rate jumped to 92%.

Terminally ill patients typically disavow CPR when choosing a palliative course of action. However, surgery can be a part of palliation. In 1991, approximately 15% of patients with DNR orders had a surgical procedure, with most interventions targeting comfort and/or nursing care. When a terminally ill patient with a DNR order undergoes surgery, how should physicians deal with the patient’s no-code status, especially if an iatrogenic cardiac arrest should occur?

Because overriding a patient’s DNR wish violates the right of self-determination, a reasonable rule is to require the surgeon and/or anesthesiologist to discuss preoperatively the increased risk of a cardiac arrest during surgery, as well as the markedly improved chance of a successful resuscitation. The patient will then decide whether to retain his/her original DNR intent, or to suspend its execution in the perioperative period.5

What about iatrogenesis?

In 1999, David Casarett, MD, and Lainie F. Ross, MD, PhD, assessed whether physicians were more likely to override a DNR order if a hypothetical cardiac arrest was caused iatrogenically.6 Their survey revealed that 69% of physicians were very likely to do so. The authors suggested three explanations: 1) concern for malpractice litigation, 2) feelings of guilt or responsibility, and 3) the belief that patients do not consider the possibility of an iatrogenic cardiac arrest when they consent to a DNR order. Physicians may also believe a “properly negotiated DNR order does not apply to all foreseeable circumstances.”

However, some ethicists believe that an iatrogenic mishap does not make it permissible to override a patient’s prior refusal of treatment, because errors should not alter ethical obligations to respect a patient’s wishes to forgo treatment, including CPR.

Can a DNR order exist if it is against a patient’s wishes?7 In Gilgunn v. Massachusetts General Hospital, a 71-year-old diabetic woman with heart disease, breast cancer, and a hip fracture suffered two grand mal seizures and lapsed into a coma.8 Her daughter was the surrogate decision maker, and she made it clear that her mother always said she wanted everything done. After several weeks, the physicians decided that further treatment would be futile.

The chair of the ethics committee felt that the daughter’s opinion was not relevant because CPR was not a genuine therapeutic option and would be “medically contraindicated, inhumane, and unethical.” Accordingly, the attending physician entered a DNR order despite strong protest from the daughter. The patient died shortly thereafter without receiving CPR, and the daughter filed a negligence lawsuit against the hospital.

Still, there are state and federal statutes touching on DNR orders that warrant careful attention. For example, New York Public Health Law Section 2962, paragraph 1, states: “Every person admitted to a hospital shall be presumed to consent to the administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of cardiac or respiratory arrest, unless there is consent to the issuance of an order not to resuscitate ...” This raises the question as to whether it is ever legally permissible in New York to enter a unilateral DNR order against the wishes of the patient.

And the federal “anti-dumping” law governing emergency treatment, widely known as EMTALA (Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act), requires all emergency departments to provide treatment necessary to prevent the material deterioration of the individual’s condition. This would always include the use of CPR unless specifically rejected by the patient or surrogate, as the law does not contain a “standard of care” or “futility” exception.9

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 30;377(22):2192-3.

2. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1983.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jul;26(7):791-7.

4. JAMA. 1995 Nov 22-29;274(20):1591-8.

5. Hawaii Med J. 2001 Mar;60(3):64-7.

6. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 26;336(26):1908-10.

7. Tan SY. Futility and DNR Orders. Internal Medicine News, March 21, 2014.

8. Gilgunn v. Mass. General Hosp. No. 92-4820 (Mass. Super Ct. Apr. 21, 1995).

9. In re Baby K, 16 F.3d 590 (4th Cir. 1994).

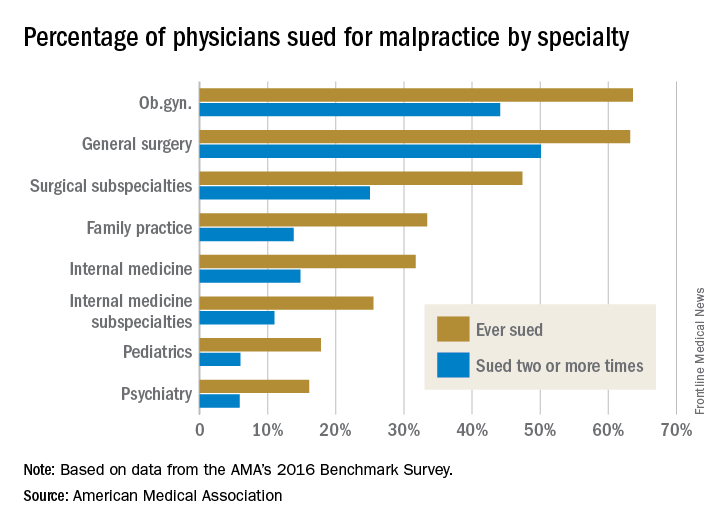

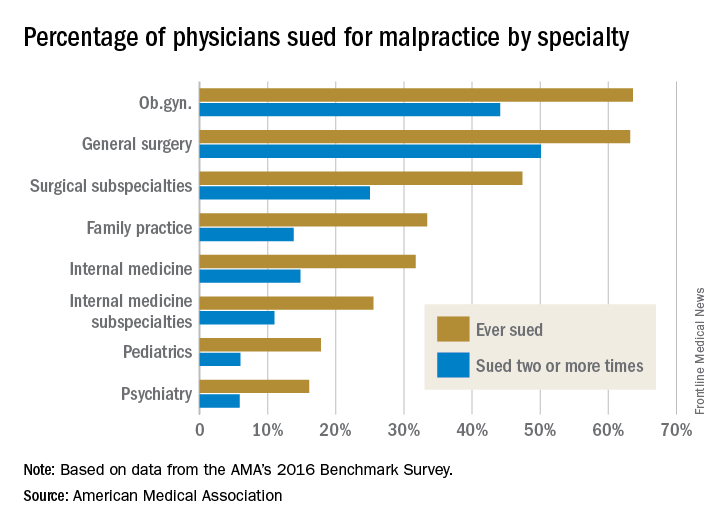

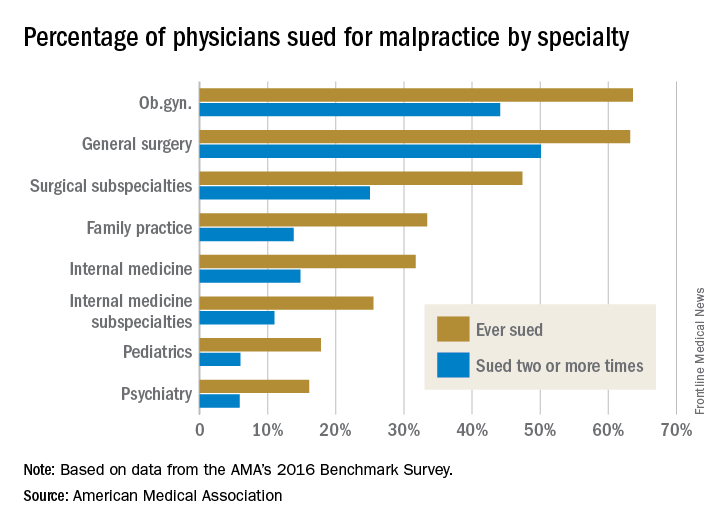

Study: Half of doctors sued by age 55

By age 55, nearly half of physicians have been sued for malpractice, with general surgeons and obstetricians-gynecologists facing the highest lawsuit risks, according to data from the America Medical Association.

Investigators with the AMA surveyed 3,500 postresidency physicians who were not employed by the federal government. Findings show that the probability of getting sued increases with age, and that male doctors are more likely to be sued than female physicians. For example, only 8% of doctors under 40 have been sued, compared to nearly half of physicians over age 54, the study found. In addition, nearly 40% of male physicians have been sued over the course of their careers, compared with 23% of female doctors.

Employed physicians were no more or less likely than were physician-owners to have been sued. In addition, while solo practitioners had more claims filed against them than did doctors in single-specialty groups, the estimate was not statistically significant.

In a second report, an analysis showed the average expense incurred during a medical liability claim is $54,165 – a 65% increase since 2006. For the study, the AMA analyzed data from PIAA, a trade association for the medical professional liability insurance industry, and evaluated payments, expenses, and claim disposition within a sample of 90,473 medical liability claims that closed between 2006 and 2015.

Only 7% of claims were decided by a trial verdict with the vast majority (88%) won by the defendant health care provider. In about 25% of claims, a payment was paid to the plaintiff. The average indemnity payment to a plaintiff was $365,503 and the median payment was $200,000.

The new research paints a bleak picture of physicians’ experiences with medical liability claims and the associated cost burdens on the health system, AMA President David O. Barbe, MD, said in a statement.

“Even though the vast majority of claims are dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn, the heavy cost associated with a litigious climate takes a significant financial toll on our health care system when the nation is working to reduce unnecessary health care costs,” Dr. Barbe said.

By age 55, nearly half of physicians have been sued for malpractice, with general surgeons and obstetricians-gynecologists facing the highest lawsuit risks, according to data from the America Medical Association.

Investigators with the AMA surveyed 3,500 postresidency physicians who were not employed by the federal government. Findings show that the probability of getting sued increases with age, and that male doctors are more likely to be sued than female physicians. For example, only 8% of doctors under 40 have been sued, compared to nearly half of physicians over age 54, the study found. In addition, nearly 40% of male physicians have been sued over the course of their careers, compared with 23% of female doctors.

Employed physicians were no more or less likely than were physician-owners to have been sued. In addition, while solo practitioners had more claims filed against them than did doctors in single-specialty groups, the estimate was not statistically significant.

In a second report, an analysis showed the average expense incurred during a medical liability claim is $54,165 – a 65% increase since 2006. For the study, the AMA analyzed data from PIAA, a trade association for the medical professional liability insurance industry, and evaluated payments, expenses, and claim disposition within a sample of 90,473 medical liability claims that closed between 2006 and 2015.

Only 7% of claims were decided by a trial verdict with the vast majority (88%) won by the defendant health care provider. In about 25% of claims, a payment was paid to the plaintiff. The average indemnity payment to a plaintiff was $365,503 and the median payment was $200,000.

The new research paints a bleak picture of physicians’ experiences with medical liability claims and the associated cost burdens on the health system, AMA President David O. Barbe, MD, said in a statement.

“Even though the vast majority of claims are dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn, the heavy cost associated with a litigious climate takes a significant financial toll on our health care system when the nation is working to reduce unnecessary health care costs,” Dr. Barbe said.

By age 55, nearly half of physicians have been sued for malpractice, with general surgeons and obstetricians-gynecologists facing the highest lawsuit risks, according to data from the America Medical Association.

Investigators with the AMA surveyed 3,500 postresidency physicians who were not employed by the federal government. Findings show that the probability of getting sued increases with age, and that male doctors are more likely to be sued than female physicians. For example, only 8% of doctors under 40 have been sued, compared to nearly half of physicians over age 54, the study found. In addition, nearly 40% of male physicians have been sued over the course of their careers, compared with 23% of female doctors.

Employed physicians were no more or less likely than were physician-owners to have been sued. In addition, while solo practitioners had more claims filed against them than did doctors in single-specialty groups, the estimate was not statistically significant.

In a second report, an analysis showed the average expense incurred during a medical liability claim is $54,165 – a 65% increase since 2006. For the study, the AMA analyzed data from PIAA, a trade association for the medical professional liability insurance industry, and evaluated payments, expenses, and claim disposition within a sample of 90,473 medical liability claims that closed between 2006 and 2015.

Only 7% of claims were decided by a trial verdict with the vast majority (88%) won by the defendant health care provider. In about 25% of claims, a payment was paid to the plaintiff. The average indemnity payment to a plaintiff was $365,503 and the median payment was $200,000.

The new research paints a bleak picture of physicians’ experiences with medical liability claims and the associated cost burdens on the health system, AMA President David O. Barbe, MD, said in a statement.

“Even though the vast majority of claims are dropped, dismissed, or withdrawn, the heavy cost associated with a litigious climate takes a significant financial toll on our health care system when the nation is working to reduce unnecessary health care costs,” Dr. Barbe said.

Reported penicillin allergies hike inpatient costs

Total inpatient costs for patients who report being allergic to penicillin are much higher than for those who don’t report an allergy, according to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

The review, which eventually included 30 articles, found that total inpatient costs ranged from an average $1,145-$4,254 higher per patient with a reported penicillin allergy compared to nonallergic patients, said T. Joseph Mattingly, PharmD, and his associates. Outpatient prescription costs were also estimated to be steeper, running $14-$93 higher per patient who reported a penicillin allergy.

Although 10%-20% of patients report a penicillin allergy, “[a] majority of patients who report PCN [penicillin] allergy are not truly allergic upon confirmatory testing,” Dr. Mattingly and his colleagues wrote.

This overreporting of penicillin allergies is a problem for the patient and the health care system because “reported antibiotic allergies have been associated with suboptimal antibiotic therapy, increased antimicrobial resistance, increased length of stay, increased antibiotic-related adverse events, increased rates of C. difficile infection, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, death, as well as increased treatment cost,” said Dr. Mattingly and his coauthors.

Health care providers often “tend to take reported allergies at face value,” said coauthor Anne Fulton, suggesting that primary care practices can help by considering skin testing for those patients who carry a label of penicillin allergy, but don’t have a documented confirmatory test. The cost for a commonly used skin test for penicillin allergy runs about $200, said Ms. Fulton, a doctoral candidate at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview.

When conducting the meta-analysis, Dr. Mattingly and his coauthors converted all figures to 2017 U.S. dollars, using Consumer Price Index figures to adjust for inflation. This yields conservative estimates for cost, as drug and health care prices have far outstripped the general rate of inflation during the period in which the studies occurred, Ms. Fulton acknowledged.

The investigators highlighted the need for ongoing study in this area. “To our knowledge, there are no evaluations of long-term outpatient outcomes related to the effects of PCN allergy and the potential impact of delabeling patients who do not have a true allergy,” they wrote.

Ms. Fulton agreed, noting that the studies covered in the meta-analysis were primarily focused on short-term outcomes, though there are many potential long-term benefits to delabeling patients who are not truly penicillin allergic.

For the patient, this includes the opportunity to receive optimal antimicrobial therapy, as well as potential savings in copays and other out-of-pocket expenses for outpatient medications, she said.

As antimicrobial resistance becomes an ever more pressing problem, there are more opportunities for targeted therapy if inappropriate allergy labeling is addressed, Ms. Fulton added.

Further study should use “cost-effectiveness analysis methods that include societal and health sector perspectives capturing immediate and future outcomes and costs to evaluate the use of skin-testing procedures in either inpatient or outpatient settings,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by ALK, the manufacturer of Pre-Pen, a commercially available penicillin allergy skin test.

SOURCE: Mattingly TJ et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018 Jan 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033.

Total inpatient costs for patients who report being allergic to penicillin are much higher than for those who don’t report an allergy, according to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

The review, which eventually included 30 articles, found that total inpatient costs ranged from an average $1,145-$4,254 higher per patient with a reported penicillin allergy compared to nonallergic patients, said T. Joseph Mattingly, PharmD, and his associates. Outpatient prescription costs were also estimated to be steeper, running $14-$93 higher per patient who reported a penicillin allergy.

Although 10%-20% of patients report a penicillin allergy, “[a] majority of patients who report PCN [penicillin] allergy are not truly allergic upon confirmatory testing,” Dr. Mattingly and his colleagues wrote.

This overreporting of penicillin allergies is a problem for the patient and the health care system because “reported antibiotic allergies have been associated with suboptimal antibiotic therapy, increased antimicrobial resistance, increased length of stay, increased antibiotic-related adverse events, increased rates of C. difficile infection, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, death, as well as increased treatment cost,” said Dr. Mattingly and his coauthors.

Health care providers often “tend to take reported allergies at face value,” said coauthor Anne Fulton, suggesting that primary care practices can help by considering skin testing for those patients who carry a label of penicillin allergy, but don’t have a documented confirmatory test. The cost for a commonly used skin test for penicillin allergy runs about $200, said Ms. Fulton, a doctoral candidate at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview.

When conducting the meta-analysis, Dr. Mattingly and his coauthors converted all figures to 2017 U.S. dollars, using Consumer Price Index figures to adjust for inflation. This yields conservative estimates for cost, as drug and health care prices have far outstripped the general rate of inflation during the period in which the studies occurred, Ms. Fulton acknowledged.

The investigators highlighted the need for ongoing study in this area. “To our knowledge, there are no evaluations of long-term outpatient outcomes related to the effects of PCN allergy and the potential impact of delabeling patients who do not have a true allergy,” they wrote.

Ms. Fulton agreed, noting that the studies covered in the meta-analysis were primarily focused on short-term outcomes, though there are many potential long-term benefits to delabeling patients who are not truly penicillin allergic.

For the patient, this includes the opportunity to receive optimal antimicrobial therapy, as well as potential savings in copays and other out-of-pocket expenses for outpatient medications, she said.

As antimicrobial resistance becomes an ever more pressing problem, there are more opportunities for targeted therapy if inappropriate allergy labeling is addressed, Ms. Fulton added.

Further study should use “cost-effectiveness analysis methods that include societal and health sector perspectives capturing immediate and future outcomes and costs to evaluate the use of skin-testing procedures in either inpatient or outpatient settings,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by ALK, the manufacturer of Pre-Pen, a commercially available penicillin allergy skin test.

SOURCE: Mattingly TJ et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018 Jan 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033.

Total inpatient costs for patients who report being allergic to penicillin are much higher than for those who don’t report an allergy, according to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.

The review, which eventually included 30 articles, found that total inpatient costs ranged from an average $1,145-$4,254 higher per patient with a reported penicillin allergy compared to nonallergic patients, said T. Joseph Mattingly, PharmD, and his associates. Outpatient prescription costs were also estimated to be steeper, running $14-$93 higher per patient who reported a penicillin allergy.

Although 10%-20% of patients report a penicillin allergy, “[a] majority of patients who report PCN [penicillin] allergy are not truly allergic upon confirmatory testing,” Dr. Mattingly and his colleagues wrote.

This overreporting of penicillin allergies is a problem for the patient and the health care system because “reported antibiotic allergies have been associated with suboptimal antibiotic therapy, increased antimicrobial resistance, increased length of stay, increased antibiotic-related adverse events, increased rates of C. difficile infection, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, death, as well as increased treatment cost,” said Dr. Mattingly and his coauthors.

Health care providers often “tend to take reported allergies at face value,” said coauthor Anne Fulton, suggesting that primary care practices can help by considering skin testing for those patients who carry a label of penicillin allergy, but don’t have a documented confirmatory test. The cost for a commonly used skin test for penicillin allergy runs about $200, said Ms. Fulton, a doctoral candidate at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview.

When conducting the meta-analysis, Dr. Mattingly and his coauthors converted all figures to 2017 U.S. dollars, using Consumer Price Index figures to adjust for inflation. This yields conservative estimates for cost, as drug and health care prices have far outstripped the general rate of inflation during the period in which the studies occurred, Ms. Fulton acknowledged.

The investigators highlighted the need for ongoing study in this area. “To our knowledge, there are no evaluations of long-term outpatient outcomes related to the effects of PCN allergy and the potential impact of delabeling patients who do not have a true allergy,” they wrote.

Ms. Fulton agreed, noting that the studies covered in the meta-analysis were primarily focused on short-term outcomes, though there are many potential long-term benefits to delabeling patients who are not truly penicillin allergic.

For the patient, this includes the opportunity to receive optimal antimicrobial therapy, as well as potential savings in copays and other out-of-pocket expenses for outpatient medications, she said.

As antimicrobial resistance becomes an ever more pressing problem, there are more opportunities for targeted therapy if inappropriate allergy labeling is addressed, Ms. Fulton added.

Further study should use “cost-effectiveness analysis methods that include societal and health sector perspectives capturing immediate and future outcomes and costs to evaluate the use of skin-testing procedures in either inpatient or outpatient settings,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by ALK, the manufacturer of Pre-Pen, a commercially available penicillin allergy skin test.

SOURCE: Mattingly TJ et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018 Jan 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033.

FROM JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY: IN PRACTICE

Key clinical point: Inpatient costs were $1,145 – $4,254 higher for those reporting penicillin allergy.

Major finding: Though most studies addressed inpatient admissions, outpatient costs were also significantly higher.

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 articles addressing reported penicillin allergy.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by ALK.

Source: Mattingly TJ et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018 Jan 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033.

MedPAC: Medicare hospital readmissions program is working

WASHINGTON – The Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program is working, according to an original analysis of Medicare claims data presented at a meeting of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

“First, readmissions declined,” MedPAC staff member Jeff Stensland, PhD, said during a congressionally mandated staff report to the commissioners. “Second, while observation stays increased, they did not fully offset the decrease in readmissions. Third, while [emergency department] visits also increased, those increases appear to largely be due to factors other than the readmission program. And fourth, in addition, all the evidence we examined suggests that the readmissions program did not result in increased mortality.”

including a reduction in readmissions and patients spending less time in the hospital with “at least equal outcomes,” Dr. Stensland said at the meeting.

Taxpayers benefited from a $2 billion reduction in spending on readmissions, which will “help extend the viability of the Medicare Trust Fund.” He noted that improvements to the program will be discussed at future MedPAC meetings.

Not all MedPAC commissioners agreed with the staff analysis.

David Nerenz, PhD, of the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, also was not convinced the program was having an impact, noting that hospital readmissions began to decline even before the program started.

In looking at a graph presented that showed this trend, “I was impressed by the fact that the trend line started coming down all the way to the left side of the graph, and what my eye was impressed with was more just the continuation rather than a change, so I guess I feel cautious saying the program had certain effects because they certainly don’t jump off the graph visually,” Dr. Nerenz said. “I’m not disputing the numbers, but to say just as a clear unqualified conclusion the program reduced readmissions, I’m not so sure.”

It is likely premature to make any firm conclusions about how effectively this program decreases unnecessary utilization of hospitals. However, it is heartening to know that it did not increase mortality. The one variable that would best control readmissions is patient education. What constitutes an emergency requiring hospital evaluation and potential admission is often not explained to the patient by you and me.

It is likely premature to make any firm conclusions about how effectively this program decreases unnecessary utilization of hospitals. However, it is heartening to know that it did not increase mortality. The one variable that would best control readmissions is patient education. What constitutes an emergency requiring hospital evaluation and potential admission is often not explained to the patient by you and me.

It is likely premature to make any firm conclusions about how effectively this program decreases unnecessary utilization of hospitals. However, it is heartening to know that it did not increase mortality. The one variable that would best control readmissions is patient education. What constitutes an emergency requiring hospital evaluation and potential admission is often not explained to the patient by you and me.

WASHINGTON – The Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program is working, according to an original analysis of Medicare claims data presented at a meeting of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

“First, readmissions declined,” MedPAC staff member Jeff Stensland, PhD, said during a congressionally mandated staff report to the commissioners. “Second, while observation stays increased, they did not fully offset the decrease in readmissions. Third, while [emergency department] visits also increased, those increases appear to largely be due to factors other than the readmission program. And fourth, in addition, all the evidence we examined suggests that the readmissions program did not result in increased mortality.”

including a reduction in readmissions and patients spending less time in the hospital with “at least equal outcomes,” Dr. Stensland said at the meeting.

Taxpayers benefited from a $2 billion reduction in spending on readmissions, which will “help extend the viability of the Medicare Trust Fund.” He noted that improvements to the program will be discussed at future MedPAC meetings.

Not all MedPAC commissioners agreed with the staff analysis.

David Nerenz, PhD, of the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, also was not convinced the program was having an impact, noting that hospital readmissions began to decline even before the program started.

In looking at a graph presented that showed this trend, “I was impressed by the fact that the trend line started coming down all the way to the left side of the graph, and what my eye was impressed with was more just the continuation rather than a change, so I guess I feel cautious saying the program had certain effects because they certainly don’t jump off the graph visually,” Dr. Nerenz said. “I’m not disputing the numbers, but to say just as a clear unqualified conclusion the program reduced readmissions, I’m not so sure.”

WASHINGTON – The Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program is working, according to an original analysis of Medicare claims data presented at a meeting of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

“First, readmissions declined,” MedPAC staff member Jeff Stensland, PhD, said during a congressionally mandated staff report to the commissioners. “Second, while observation stays increased, they did not fully offset the decrease in readmissions. Third, while [emergency department] visits also increased, those increases appear to largely be due to factors other than the readmission program. And fourth, in addition, all the evidence we examined suggests that the readmissions program did not result in increased mortality.”

including a reduction in readmissions and patients spending less time in the hospital with “at least equal outcomes,” Dr. Stensland said at the meeting.

Taxpayers benefited from a $2 billion reduction in spending on readmissions, which will “help extend the viability of the Medicare Trust Fund.” He noted that improvements to the program will be discussed at future MedPAC meetings.

Not all MedPAC commissioners agreed with the staff analysis.

David Nerenz, PhD, of the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, also was not convinced the program was having an impact, noting that hospital readmissions began to decline even before the program started.

In looking at a graph presented that showed this trend, “I was impressed by the fact that the trend line started coming down all the way to the left side of the graph, and what my eye was impressed with was more just the continuation rather than a change, so I guess I feel cautious saying the program had certain effects because they certainly don’t jump off the graph visually,” Dr. Nerenz said. “I’m not disputing the numbers, but to say just as a clear unqualified conclusion the program reduced readmissions, I’m not so sure.”

REPORTING FROM MEDPAC

Checklists to improve patient safety have mixed results

Clinical question: Do checklists improve patient safety among hospitalized patients?

Background: Systematic reviews of nonrandomized studies suggest checklists may reduce adverse events and medical errors. No study has systematically reviewed randomized trials or summarized the quality of evidence on this topic.

Study design: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with pooled estimates of 30-day mortality.

Setting: RCTs reporting inpatient safety outcomes.

Synopsis: A search among four databases from inception through 2016 yielded nine studies meeting inclusion criteria. Checklists included tools for daily rounding, discharge planning, patient transfer, surgical safety and infection control procedures, pharmaceutical prescribing, and pain control. Three studies examined 30-day mortality, three studied length of stay, and two reported checklist compliance. Five reported patient outcomes and five reported provider-level outcomes related to patient safety. Findings regarding the effectiveness of checklists across studies were mixed. A random-effects model using pooled data from the three studies assessing 30-day mortality showed lower mortality associated with checklist use (odds ratio, 0.6, 95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.89; P = .01). The methodologic quality of studies was assessed as moderate. The review included studies with substantial heterogeneity in checklists employed and outcomes assessed. Though included studies were supposed to have assessed patient outcomes and not the processes of care, several studies cited did not report such outcomes.

Bottom line: Evidence regarding the effectiveness of clinical checklists on patient safety outcomes is mixed, and there is substantial heterogeneity in the types of checklists employed and outcomes assessed.

Citation: Boyd JM et al. The impact of checklists on inpatient safety outcomes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug;12:675-82.

Dr. Simonetti is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: Do checklists improve patient safety among hospitalized patients?

Background: Systematic reviews of nonrandomized studies suggest checklists may reduce adverse events and medical errors. No study has systematically reviewed randomized trials or summarized the quality of evidence on this topic.

Study design: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with pooled estimates of 30-day mortality.

Setting: RCTs reporting inpatient safety outcomes.

Synopsis: A search among four databases from inception through 2016 yielded nine studies meeting inclusion criteria. Checklists included tools for daily rounding, discharge planning, patient transfer, surgical safety and infection control procedures, pharmaceutical prescribing, and pain control. Three studies examined 30-day mortality, three studied length of stay, and two reported checklist compliance. Five reported patient outcomes and five reported provider-level outcomes related to patient safety. Findings regarding the effectiveness of checklists across studies were mixed. A random-effects model using pooled data from the three studies assessing 30-day mortality showed lower mortality associated with checklist use (odds ratio, 0.6, 95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.89; P = .01). The methodologic quality of studies was assessed as moderate. The review included studies with substantial heterogeneity in checklists employed and outcomes assessed. Though included studies were supposed to have assessed patient outcomes and not the processes of care, several studies cited did not report such outcomes.

Bottom line: Evidence regarding the effectiveness of clinical checklists on patient safety outcomes is mixed, and there is substantial heterogeneity in the types of checklists employed and outcomes assessed.

Citation: Boyd JM et al. The impact of checklists on inpatient safety outcomes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug;12:675-82.

Dr. Simonetti is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: Do checklists improve patient safety among hospitalized patients?

Background: Systematic reviews of nonrandomized studies suggest checklists may reduce adverse events and medical errors. No study has systematically reviewed randomized trials or summarized the quality of evidence on this topic.

Study design: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with pooled estimates of 30-day mortality.

Setting: RCTs reporting inpatient safety outcomes.

Synopsis: A search among four databases from inception through 2016 yielded nine studies meeting inclusion criteria. Checklists included tools for daily rounding, discharge planning, patient transfer, surgical safety and infection control procedures, pharmaceutical prescribing, and pain control. Three studies examined 30-day mortality, three studied length of stay, and two reported checklist compliance. Five reported patient outcomes and five reported provider-level outcomes related to patient safety. Findings regarding the effectiveness of checklists across studies were mixed. A random-effects model using pooled data from the three studies assessing 30-day mortality showed lower mortality associated with checklist use (odds ratio, 0.6, 95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.89; P = .01). The methodologic quality of studies was assessed as moderate. The review included studies with substantial heterogeneity in checklists employed and outcomes assessed. Though included studies were supposed to have assessed patient outcomes and not the processes of care, several studies cited did not report such outcomes.

Bottom line: Evidence regarding the effectiveness of clinical checklists on patient safety outcomes is mixed, and there is substantial heterogeneity in the types of checklists employed and outcomes assessed.

Citation: Boyd JM et al. The impact of checklists on inpatient safety outcomes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug;12:675-82.

Dr. Simonetti is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

SHM launches 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Survey

The Society of Hospital Medicine recently opened the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Survey and is now seeking participants from hospital medicine groups to contribute to the collective understanding of the state of the specialty.

Results from the biennial survey will be analyzed and compiled into the 2018 SoHM Report to provide current data on hospitalist compensation and production, as well as cutting-edge knowledge covering practice demographics, staffing levels, turnover, staff growth, and financial support. The SoHM Survey closes on Feb. 16, 2018.

“The SoHM Survey lays the foundation for the creation of one of the most expansive tools for hospital medicine professionals,” said Beth Hawley, MBA, FACHE, chief operating officer of SHM. “With the help of participants from hospital medicine groups nationwide, it creates an up-to-date snapshot of trends in the specialty to help inform staffing and management decisions.”

The 2018 SoHM Survey includes new questions about open hospitalist physician positions during the year, including what percentage of approved staffing was unfilled and how the group filled the coverage. Other new topics ask about the number of work Relative Value Units generated by participating hospital medicine groups and who selects the billing codes for the groups.

Over the past year and a half, five distinct efforts were completed to collect user feedback for both the survey and report development processes. Efforts ranged from in-person focus groups at SHM’s Annual Conference to online user surveys. After information was collected and summarized, SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee ranked every question to trim down the Survey from 70 questions in 2016 to 52 questions in 2018.

The 2018 SoHM Report will be available this fall in print only, as a bundle of print and digital, or as digital only, with special discounts available for SHM members.

Committee members are available for one-on-one guidance as participants complete the Survey. For more information and to participate, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm.

The Society of Hospital Medicine recently opened the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Survey and is now seeking participants from hospital medicine groups to contribute to the collective understanding of the state of the specialty.

Results from the biennial survey will be analyzed and compiled into the 2018 SoHM Report to provide current data on hospitalist compensation and production, as well as cutting-edge knowledge covering practice demographics, staffing levels, turnover, staff growth, and financial support. The SoHM Survey closes on Feb. 16, 2018.

“The SoHM Survey lays the foundation for the creation of one of the most expansive tools for hospital medicine professionals,” said Beth Hawley, MBA, FACHE, chief operating officer of SHM. “With the help of participants from hospital medicine groups nationwide, it creates an up-to-date snapshot of trends in the specialty to help inform staffing and management decisions.”

The 2018 SoHM Survey includes new questions about open hospitalist physician positions during the year, including what percentage of approved staffing was unfilled and how the group filled the coverage. Other new topics ask about the number of work Relative Value Units generated by participating hospital medicine groups and who selects the billing codes for the groups.

Over the past year and a half, five distinct efforts were completed to collect user feedback for both the survey and report development processes. Efforts ranged from in-person focus groups at SHM’s Annual Conference to online user surveys. After information was collected and summarized, SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee ranked every question to trim down the Survey from 70 questions in 2016 to 52 questions in 2018.

The 2018 SoHM Report will be available this fall in print only, as a bundle of print and digital, or as digital only, with special discounts available for SHM members.

Committee members are available for one-on-one guidance as participants complete the Survey. For more information and to participate, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm.

The Society of Hospital Medicine recently opened the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Survey and is now seeking participants from hospital medicine groups to contribute to the collective understanding of the state of the specialty.

Results from the biennial survey will be analyzed and compiled into the 2018 SoHM Report to provide current data on hospitalist compensation and production, as well as cutting-edge knowledge covering practice demographics, staffing levels, turnover, staff growth, and financial support. The SoHM Survey closes on Feb. 16, 2018.

“The SoHM Survey lays the foundation for the creation of one of the most expansive tools for hospital medicine professionals,” said Beth Hawley, MBA, FACHE, chief operating officer of SHM. “With the help of participants from hospital medicine groups nationwide, it creates an up-to-date snapshot of trends in the specialty to help inform staffing and management decisions.”

The 2018 SoHM Survey includes new questions about open hospitalist physician positions during the year, including what percentage of approved staffing was unfilled and how the group filled the coverage. Other new topics ask about the number of work Relative Value Units generated by participating hospital medicine groups and who selects the billing codes for the groups.

Over the past year and a half, five distinct efforts were completed to collect user feedback for both the survey and report development processes. Efforts ranged from in-person focus groups at SHM’s Annual Conference to online user surveys. After information was collected and summarized, SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee ranked every question to trim down the Survey from 70 questions in 2016 to 52 questions in 2018.

The 2018 SoHM Report will be available this fall in print only, as a bundle of print and digital, or as digital only, with special discounts available for SHM members.

Committee members are available for one-on-one guidance as participants complete the Survey. For more information and to participate, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm.

U.S. hospitalists estimate significant resources spent on defensive medicine

Clinical question: What percent of inpatient health care spending by hospitalists can be attributed to defensive medicine?

Background: Defensive medicine contributes an estimated $45 billion to annual U.S. health care expenditures. The prevalence of defensive medicine among hospitalists is unknown.

Setting: National survey sent to 1,753 hospitalists from all 50 states identified through the Society of Hospital Medicine database of members and meeting attendees.

Synopsis: The survey contained two primary topics: an estimation of defensive spending and liability history. The hospitalists, who had an average of 11 years in practice, completed 1,020 surveys. Participants estimated that defensive medicine accounted for 37.5% of all health care costs. Decreased estimate rates were seen among VA hospitalists (5.5% less), male respondents (36.4% vs. 39.4% for female), non-Hispanic white respondents (32.5% vs. 44.7% for other) and having more years in practice (decrease of 3% for every 10 years in practice). One in four respondents reported being sued at least once, with higher risk seen in those with greater years in practice. There was no association between liability experience and perception of defensive medicine spending. Differences between academic and community settings were not addressed. Because only 30% of practicing hospitalists are members of SHM, it may be difficult to generalize these findings.

Bottom line: Hospitalists perceive that defensive medicine is a major contributor to inpatient health care expenditures.

Citation: Saint S et al. Perception of resources spent on defensive medicine and history of being sued among hospitalists: Results from a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug 23. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2800.

Dr. Lublin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: What percent of inpatient health care spending by hospitalists can be attributed to defensive medicine?

Background: Defensive medicine contributes an estimated $45 billion to annual U.S. health care expenditures. The prevalence of defensive medicine among hospitalists is unknown.

Setting: National survey sent to 1,753 hospitalists from all 50 states identified through the Society of Hospital Medicine database of members and meeting attendees.

Synopsis: The survey contained two primary topics: an estimation of defensive spending and liability history. The hospitalists, who had an average of 11 years in practice, completed 1,020 surveys. Participants estimated that defensive medicine accounted for 37.5% of all health care costs. Decreased estimate rates were seen among VA hospitalists (5.5% less), male respondents (36.4% vs. 39.4% for female), non-Hispanic white respondents (32.5% vs. 44.7% for other) and having more years in practice (decrease of 3% for every 10 years in practice). One in four respondents reported being sued at least once, with higher risk seen in those with greater years in practice. There was no association between liability experience and perception of defensive medicine spending. Differences between academic and community settings were not addressed. Because only 30% of practicing hospitalists are members of SHM, it may be difficult to generalize these findings.

Bottom line: Hospitalists perceive that defensive medicine is a major contributor to inpatient health care expenditures.

Citation: Saint S et al. Perception of resources spent on defensive medicine and history of being sued among hospitalists: Results from a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug 23. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2800.

Dr. Lublin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: What percent of inpatient health care spending by hospitalists can be attributed to defensive medicine?

Background: Defensive medicine contributes an estimated $45 billion to annual U.S. health care expenditures. The prevalence of defensive medicine among hospitalists is unknown.

Setting: National survey sent to 1,753 hospitalists from all 50 states identified through the Society of Hospital Medicine database of members and meeting attendees.

Synopsis: The survey contained two primary topics: an estimation of defensive spending and liability history. The hospitalists, who had an average of 11 years in practice, completed 1,020 surveys. Participants estimated that defensive medicine accounted for 37.5% of all health care costs. Decreased estimate rates were seen among VA hospitalists (5.5% less), male respondents (36.4% vs. 39.4% for female), non-Hispanic white respondents (32.5% vs. 44.7% for other) and having more years in practice (decrease of 3% for every 10 years in practice). One in four respondents reported being sued at least once, with higher risk seen in those with greater years in practice. There was no association between liability experience and perception of defensive medicine spending. Differences between academic and community settings were not addressed. Because only 30% of practicing hospitalists are members of SHM, it may be difficult to generalize these findings.

Bottom line: Hospitalists perceive that defensive medicine is a major contributor to inpatient health care expenditures.

Citation: Saint S et al. Perception of resources spent on defensive medicine and history of being sued among hospitalists: Results from a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug 23. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2800.

Dr. Lublin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Cost transparency fails to affect high-cost medication utilization rates

Clinical question: Does cost messaging at the time of ordering reduce prescriber use of high-cost medications?

Background: Overprescribing expensive medications contributes to inpatient health care expenditures and may be avoidable when low-cost alternatives are available.

Setting: Single center, 1,145-bed, tertiary-care academic medical center.

Synopsis: Nine medications were chosen by committee to be targeted for intervention: intravenous voriconazole, IV levetiracetam, IV levothyroxine, IV linezolid, IV eculizumab, IV pantoprazole, IV calcitonin, inhaled ribavirin, and IV mycophenolate. The costs for these nine medications plus lower-cost alternatives were displayed for providers in the order entry system after about 2 years of baseline data had been collected. There was no change in the number of orders or ordering trends for eight of the nine high-cost medications after the intervention. Only ribavirin was ordered less after cost messaging was implemented (16.3 fewer orders per 10,000 patient-days). Lower IV pantoprazole use (73% reduction), correlated with a national shortage unrelated to the study intervention, a potential confounder. Data on dosing frequency and duration were not collected.

Bottom line: Displaying medication costs and alternatives did not alter the use of these nine high-cost medications.

Citation: Conway SJ et al. Impact of displaying inpatient pharmaceutical costs at the time of order entry: Lessons from a tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug;12(8):639-45.

Dr. Lublin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: Does cost messaging at the time of ordering reduce prescriber use of high-cost medications?

Background: Overprescribing expensive medications contributes to inpatient health care expenditures and may be avoidable when low-cost alternatives are available.

Setting: Single center, 1,145-bed, tertiary-care academic medical center.

Synopsis: Nine medications were chosen by committee to be targeted for intervention: intravenous voriconazole, IV levetiracetam, IV levothyroxine, IV linezolid, IV eculizumab, IV pantoprazole, IV calcitonin, inhaled ribavirin, and IV mycophenolate. The costs for these nine medications plus lower-cost alternatives were displayed for providers in the order entry system after about 2 years of baseline data had been collected. There was no change in the number of orders or ordering trends for eight of the nine high-cost medications after the intervention. Only ribavirin was ordered less after cost messaging was implemented (16.3 fewer orders per 10,000 patient-days). Lower IV pantoprazole use (73% reduction), correlated with a national shortage unrelated to the study intervention, a potential confounder. Data on dosing frequency and duration were not collected.

Bottom line: Displaying medication costs and alternatives did not alter the use of these nine high-cost medications.

Citation: Conway SJ et al. Impact of displaying inpatient pharmaceutical costs at the time of order entry: Lessons from a tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug;12(8):639-45.

Dr. Lublin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: Does cost messaging at the time of ordering reduce prescriber use of high-cost medications?

Background: Overprescribing expensive medications contributes to inpatient health care expenditures and may be avoidable when low-cost alternatives are available.

Setting: Single center, 1,145-bed, tertiary-care academic medical center.

Synopsis: Nine medications were chosen by committee to be targeted for intervention: intravenous voriconazole, IV levetiracetam, IV levothyroxine, IV linezolid, IV eculizumab, IV pantoprazole, IV calcitonin, inhaled ribavirin, and IV mycophenolate. The costs for these nine medications plus lower-cost alternatives were displayed for providers in the order entry system after about 2 years of baseline data had been collected. There was no change in the number of orders or ordering trends for eight of the nine high-cost medications after the intervention. Only ribavirin was ordered less after cost messaging was implemented (16.3 fewer orders per 10,000 patient-days). Lower IV pantoprazole use (73% reduction), correlated with a national shortage unrelated to the study intervention, a potential confounder. Data on dosing frequency and duration were not collected.

Bottom line: Displaying medication costs and alternatives did not alter the use of these nine high-cost medications.

Citation: Conway SJ et al. Impact of displaying inpatient pharmaceutical costs at the time of order entry: Lessons from a tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2017 Aug;12(8):639-45.

Dr. Lublin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

MedPAC recommends scrapping MIPS, gets pushback from doctors

WASHINGTON – As unpopular as the new Quality Payment Program may be, repealing all or part of it at this stage will be a tough sell.

That was the message heard by members of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) during public comments at their Jan. 11 meeting. Comments followed a 14-2 vote by commissioners in favor of recommending that Congress scrap the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the QPP.

“We do agree that there are problems with MIPS,” said Sharon McIlrath, assistant director of federal affairs and coalitions at the American Medical Association. “We would like to fix it rather than kill it, and partly that’s because we don’t want to send shifting messages to physicians. Are they going to invest in building an infrastructure on shifting ground?”

She also questioned whether this proposal could gain any traction at all in Congress.

“We don’t think that it is politically viable to think that you are going to go up there and get the Hill to kill MIPS,” she said.

The Alliance of Specialty Medicine in a Jan. 9 letter to MedPAC also voiced its objections to the commission’s plan to recommend the end of MIPS.

“Our efforts to work with CMS and congressional leaders to improve MIPS and allow for more meaningful and robust engagement are ongoing. We urge you to withdraw your forthcoming recommendation, which diminishes the important role of specialty medicine in Medicare,” alliance members wrote to MedPAC Chairman Francis J. Crosson, MD. “Instead, the commission and staff, under your leadership, should work toward a new recommendation that would improve aspects of the MIPS program that remain a challenge for all clinicians.”

MedPAC had been working on its recommendations regarding MIPS since the program was launched, but ultimately came to the conclusion that it was not fixable. During a presentation on the draft recommendation, MedPAC staff listed a variety of reasons why MIPS “cannot succeed,” including how it replicates flaws of previous value-based purchasing plans and is burdensome and complex, the information reported is not meaningful, scores are not comparable across clinicians, and the payment adjustments, while minimal early on, could vary widely from year to year with even the smallest of MIPS score changes.

Instead, current draft MedPAC recommendations put forward a voluntary value program (VVP) to replace MIPS. VVP would withhold a specific percentage of Medicare pay for physicians who are not involved in a QPP advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

Physicians would be able to earn back the withheld pay, plus be eligible for potential bonuses by voluntarily participating in virtual groups. Those groups would be scored on population-based measures.

As was the case across previous meetings where this was discussed, commissioners David Nerenz, PhD, of the Henry Ford Health System of Detroit, and Alice Coombs, MD, of South Shore Hospital, Weymouth, Mass., continued to voice their objections about repealing MIPS and ultimately voted against the recommendation.

The MIPS recommendation will be included in MedPAC’s June report to Congress; it then will be up to Congress to decide whether to act on it.

WASHINGTON – As unpopular as the new Quality Payment Program may be, repealing all or part of it at this stage will be a tough sell.

That was the message heard by members of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) during public comments at their Jan. 11 meeting. Comments followed a 14-2 vote by commissioners in favor of recommending that Congress scrap the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the QPP.

“We do agree that there are problems with MIPS,” said Sharon McIlrath, assistant director of federal affairs and coalitions at the American Medical Association. “We would like to fix it rather than kill it, and partly that’s because we don’t want to send shifting messages to physicians. Are they going to invest in building an infrastructure on shifting ground?”

She also questioned whether this proposal could gain any traction at all in Congress.

“We don’t think that it is politically viable to think that you are going to go up there and get the Hill to kill MIPS,” she said.

The Alliance of Specialty Medicine in a Jan. 9 letter to MedPAC also voiced its objections to the commission’s plan to recommend the end of MIPS.

“Our efforts to work with CMS and congressional leaders to improve MIPS and allow for more meaningful and robust engagement are ongoing. We urge you to withdraw your forthcoming recommendation, which diminishes the important role of specialty medicine in Medicare,” alliance members wrote to MedPAC Chairman Francis J. Crosson, MD. “Instead, the commission and staff, under your leadership, should work toward a new recommendation that would improve aspects of the MIPS program that remain a challenge for all clinicians.”

MedPAC had been working on its recommendations regarding MIPS since the program was launched, but ultimately came to the conclusion that it was not fixable. During a presentation on the draft recommendation, MedPAC staff listed a variety of reasons why MIPS “cannot succeed,” including how it replicates flaws of previous value-based purchasing plans and is burdensome and complex, the information reported is not meaningful, scores are not comparable across clinicians, and the payment adjustments, while minimal early on, could vary widely from year to year with even the smallest of MIPS score changes.

Instead, current draft MedPAC recommendations put forward a voluntary value program (VVP) to replace MIPS. VVP would withhold a specific percentage of Medicare pay for physicians who are not involved in a QPP advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

Physicians would be able to earn back the withheld pay, plus be eligible for potential bonuses by voluntarily participating in virtual groups. Those groups would be scored on population-based measures.

As was the case across previous meetings where this was discussed, commissioners David Nerenz, PhD, of the Henry Ford Health System of Detroit, and Alice Coombs, MD, of South Shore Hospital, Weymouth, Mass., continued to voice their objections about repealing MIPS and ultimately voted against the recommendation.