User login

Shifting Culture Toward Age-Friendly Care: Lessons From VHA Early Adopters

Nearly 50% of living US veterans are aged ≥ 65 years compared with 18.3% of the general population.1,2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, has a vested interest in improving the quality and effectiveness of care for older veterans.3

Health care systems are often unprepared to care for the complex needs of older adults. There are roughly 7300 certified geriatricians practicing in the US, and about 250 new geriatricians are trained each year while the American Geriatrics Society expects > 12,000 geriatricians will be required by 2030.4,5 More geriatricians are needed to serve as the primary health care professionals (HCPs) for older adults.4,6 Health care systems like the VHA must find ways to increase geriatrics skills, knowledge, and practices among their entire health care workforce. A culture shift toward age-friendly care for older adults across care settings and inclusive of all HCPs may help meet this escalating workforce need.7

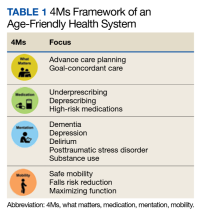

The Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) is an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.8,9 AFHS uses a what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility (4Ms) framework to ensure reliable, evidence-based care for older adults (Table 1).10,11 In an AFHS, the 4Ms are integrated into every discipline and care setting for older adults.11 The 4Ms neither replace formal training in geriatrics nor create the level of expertise needed for geriatrics teachers, researchers, and program leaders. However, the systematic approach of AFHS to assess and act on each of the 4Ms offers one solution to expand geriatrics skills and knowledge beyond geriatric care settings in all disciplines by engaging each HCP to meet the needs of older adults.12 To act on what matters, HCPs need to align the care plan with what is important to the older adult.

Hospitals and health care systems are encouraged to begin implementing the 4Ms in ≥ 1 care setting.13 Care settings may get started on a do-it-yourself track or by joining an IHI Action Community, which provides a series of webinars to help adopt the 4Ms over 7 months.14 By creating a plan for how each M will be assessed, documented, and acted on, care settings may earn level 1 recognition from the IHI.14 As of July 2023, there are at least 3100 AFHS participants and > 1900 have achieved level 2 recognition, which requires 3 months of clinical data to demonstrate the impact of the 4Ms.13,14

The main cultural shift of the AFHS movement is to focus on what matters to older adults by prioritizing each older adult’s personal health goals and care preferences across all care settings.9,11 Medication addresses age-appropropriate prescribing, making dose adjustments, if needed, and avoiding/deprescribing high-risk medications that may interfere with what matters, mentation, or mobility. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults is often used as a guide and includes lists of medications that are potentially harmful for older adults.11 Mentation focuses on preventing, identifying, treating, and managing dementia, depression, and delirium across care settings. Mobility includes assisting or encouraging older adults to move safely every day to maintain functional ability and do what matters.15,16 Each of the 4Ms has the potential to improve health outcomes for older adults, reduce waste from low-quality services, and increase the use of cost-effective services.11,17

In March 2020, the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) set the goal for the VHA to be recognized by the IHI as an AFHS.18,19 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities that joined the AFHS movement in 2020 are considered early adopters. We describe early adopter AFHS implementation at Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) hospital, geriatrics assessment clinic (GAC), and Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) and at the Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) HBPC.

Implementing 4Ms Care

The IHI identifies 6 steps in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to reliably practice the 4Ms. eAppendix 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the steps over a 9-month timeline independently taken by BVAHCS and AVAMC to achieve both levels of AFHS recognition.

Step 1: Understand the Current State

In March 2020 the BVAHCS enrolled in the IHI Action Community. Three BVAHCS care settings were identified for the Action Community: the inpatient hospital, GAC (an outpatient clinic), and HBPC. The AVAMC HBPC enrolled in the IHI Action Community in March 2021.

Before joining the AFHS movement, the BVAHCS implemented a hospital-wide delirium standard operating procedure (SOP) whereby every veteran admitted to the 313-bed hospital is screened for delirium risk, with positive screens linked to nursing-led interventions. Nursing leadership supported AFHS due to its recognized value and an exemplary process in place to assess mentation/delirium and background understanding for screening and acting on medication, mobility, and what matters most to the veteran. The BVAHCS GAC, which was led by a single geriatrician, integrated the 4Ms into all geriatrics assessment appointments.

For the BVAHCS HBPC, the 4Ms supported key performance measures, such as fall prevention, patient satisfaction, decreasing medication errors, and identification of cognition and mood disorders. For the AVAMC HBPC, joining the AFHS movement represented an opportunity to improve performance measures, interdisciplinary teamwork, and care coordination for patients. For both HBPC sites, the shift to virtual meeting modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled HBPC team members to garner support for AFHS and collectively develop a 4Ms plan.

Step 2: Describe 4Ms Care

In March 2020 as guided by the Action Community, BVAHCS created a plan for each of its 3 care settings that described assessment tools, frequency, documentation, and responsible team members. All BVAHCS care settings achieved level 1 recognition in April 2020. Of the approximately 300 veterans served by the AVAMC HBPC, 83% are aged > 65 years. They achieved level 1 recognition in August 2021.

Step 3: Design and Adapt Workflows

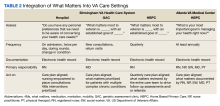

From April to August 2020, BVAHCS implemented its 4Ms plans. In the hospital, a 4Ms overview was provided with education on the delirium SOP at nursing meetings. Updates were requested to the electronic health record (EHR) templates for the GAC to streamline documentation. For the BVAHCS HBPC, 4Ms assessments were added to the EHR quarterly care plan template, which was updated by all team members (Table 2).

From April through June 2021, the AVAMC HBPC formed teams led by 4Ms champions: what matters was led by a nurse care manager, medication by a nurse practitioner and pharmacist, mentation by a social worker, and mobility by a physical therapist. The champions initially focused on a plan for each M, incorporating all 4Ms as a set for optimal effectiveness into their quarterly care plan meeting using what matters to drive the entire care plan.

Step 4: Provide Care

Each of the 4Ms was to be assessed, documented, and acted on for each veteran within a short period, such as a hospitalization or 1 or 2 outpatient visits. BVAHCS implemented 4Ms care in each care setting from August to October 2020. The AVAMC HBPC implemented 4Ms from July to September 2021.

Step 5: Study Performance

The IHI identifies 3 methods for measuring older adults who receive 4Ms care: real-time observation, chart review, or EHR report. For chart review, the IHI recommends using a random sample to calculate the number of patients who received 4Ms in 1 month, which provides evidence of progress toward reliable practice.

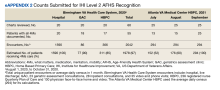

Both facilities used chart review with random sampling. Each setting estimated the number of veterans receiving 4Ms care by multiplying the percentage of sampled charts with documented 4Ms care by unique patient encounters (eAppendix 2).

From August through October 2020, BVAHCS sites reached an estimated 97% of older veterans with complete 4Ms care: hospital, 100%; GAC, 90%; and HBPC, 85%. AVAMC HBPC increased 4Ms care from 52% to 100% between July and September 2021. Both teams demonstrated the feasibility of reliably providing 4Ms care to > 85% of older veterans in these care settings and earned level 2 recognition. Through satisfaction surveys and informal feedback, notable positive changes were evident to veterans, their families, and the VA staff providing 4Ms age-friendly care.

Step 6: Improve and Sustain Care

Each site acknowledged barriers and facilitators for adopting the 4Ms. The COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing barrier for both sites, with teams transitioning to virtual modalities for telehealth visits and team meetings, and higher staff turnover. However, the greater use of technology facilitated 4Ms adoption by allowing physically distant team members to collaborate.

One of the largest barriers was the lack of 4Ms documentation in the EHR, which could not be implemented in the BVAHCS inpatient hospital due to existing standardized nursing templates. Both sites recognized that 4Ms documentation in the EHR for all care settings would facilitate achieving level 2 recognition and tracking and reporting 4Ms care in the future.

Discussion

The AFHS 4Ms approach offers a method to impart geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practice throughout an entire health care system in a short time. The AFHS framework provides a structured pathway to the often daunting challenge of care for complex, multimorbid, and highly heterogeneous older adults. The 4Ms approach promotes the provision of evidence-based care that is reliable, efficient, patient centered, and avoids unwanted care: worthy goals not only for geriatrics but for all members of a high-reliability organization.

Through the implementation of the 4Ms framework, consistent use of AFHS practices, measurement, and feedback, the staff in each VA care setting reported here reached a level of reliability in which at least 85% of patients had all 4Ms addressed. Notably, adoption was strong and improvements in reliably addressing all 4Ms were observed in both geriatrics (HBPC and outpatient clinics) and nongeriatrics (inpatient medicine) settings. Although one might expect that high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in geriatrics-focused VA settings were routinely addressing all 4Ms for most of their patients, our experience was consistent with prior teams indicating that this is often not the case. Although many of these teams were addressing some of the 4Ms in their usual practice, the 4Ms framework facilitated addressing all 4Ms as a set with input from all team members. Most importantly, it fostered a culture of asking the older adult what matters most and documenting, sharing, and aligning this with the care plan. Within 6 months, all VA care settings achieved level 1 recognition, and within 9 months, all achieved level 2 recognition.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned include the importance of identifying, preparing, and supporting a champion to lead this effort; garnering facility and system leadership support at the outset; and integration with the EHR for reliable and efficient data capture, reporting, and feedback. Preparing and supporting champions was achieved through national and individual calls and peer support. Guidance was provided on garnering leadership support, including local needs assessment and data analysis, meeting with leadership to first understand their key challenges and priorities and provide information on the AFHS movement, requesting a follow-up meeting to discuss local needs and data, and exploring how an AFHS might help address one or more of their priorities.

In September 2022, an AFHS 4Ms note template was introduced into the EHR for all VA sites for data capture and reporting, to standardize and facilitate documentation across all age-friendly VA sites, and decrease the reporting burden for staff. This effort is critically important: The ability to document, track, and analyze 4Ms measures, provide feedback, and synergize efforts across systems is vital to design studies to determine whether the AFHS 4Ms approach to care achieves substantive improvements in patient care across settings.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the small sample of care settings, which did not include a skilled nursing or long-term care facility, nor general primary care. Although the short timeframe assessed did not allow us to report on the anticipated clinical outcomes of 4Ms care, it does set up a foundation for evaluation of the 4Ms and EHR integration and dashboard development.

Conclusions

The VHA provides a comprehensive spectrum of geriatrics services and innovative models of care that often serve as exemplars to other health care systems. Implementing the AFHS framework to assess and act on the 4Ms provides a structure for confronting the HCP shortage with geriatrics expertise by infusing geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practices throughout all care settings and disciplines. Enhancing patient-centered care to older veterans through AFHS implementation exemplifies the VHA as a learning health care system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Veterans Health Administration Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care and the clinical staff from the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Healthcare System and the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System for assisting us in this work.

1. US Census Bureau. Older Americans month: May 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/stories/older-americans-month.html

2. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. July 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

3. O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):105-121. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

4. Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):219-225. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470

5. ChenMed. The physician shortage in geriatrics. March 18, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.chenmed.com/blog/physician-shortage-geriatrics

6. American Geriatrics Society. Projected future need for geriatricians. Updated May 2016. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Projected-Future-Need-for-Geriatricians.pdf 7. Carmody J, Black K, Bonner A, Wolfe M, Fulmer T. Advancing gerontological nursing at the intersection of age-friendly communities, health systems, and public health. J Gerontol Nurs. 2021;47(3):13-17. doi:10.3928/00989134-20210125-01

8. Lesser S, Zakharkin S, Louie C, Escobedo MR, Whyte J, Fulmer T. Clinician knowledge and behaviors related to the 4Ms framework of Age‐Friendly Health Systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(3):789-800. doi:10.1111/jgs.17571

9. Edelman LS, Drost J, Moone RP, et al. Applying the Age-Friendly Health System framework to long term care settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):141-145. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1558-2

10. Emery-Tiburcio EE, Mack L, Zonsius MC, Carbonell E, Newman M. The 4Ms of an Age-Friendly Health System: an evidence-based framework to ensure older adults receive the highest quality care. Home Healthc Now. 2022;40(5):252-257. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000001113

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

12. Mate KS, Berman A, Laderman M, Kabcenell A, Fulmer T. Creating age-friendly health systems – a vision for better care of older adults. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6(1):4-6. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.05.005

13. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. What is an Age-Friendly Health System? Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

14. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health systems recognized by IHI. Updated September 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/recognized-systems.aspx

15. Burke RE, Ashcraft LE, Manges K, et al. What matters when it comes to measuring Age‐Friendly Health System transformation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(10):2775-2785. doi:10.1111/jgs.18002

16. Wang J, Shen JY, Conwell Y, et al. How “age-friendly” are deprescribing interventions? A scoping review of deprescribing trials. Health Serv Res. 202;58(suppl 1):123-138. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14083

17. Pohnert AM, Schiltz NK, Pino L, et al. Achievement of age‐friendly health systems committed to care excellence designation in a convenient care health care system. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 (suppl 1):89-99. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14071

18. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2022;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

19. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age‐friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

Nearly 50% of living US veterans are aged ≥ 65 years compared with 18.3% of the general population.1,2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, has a vested interest in improving the quality and effectiveness of care for older veterans.3

Health care systems are often unprepared to care for the complex needs of older adults. There are roughly 7300 certified geriatricians practicing in the US, and about 250 new geriatricians are trained each year while the American Geriatrics Society expects > 12,000 geriatricians will be required by 2030.4,5 More geriatricians are needed to serve as the primary health care professionals (HCPs) for older adults.4,6 Health care systems like the VHA must find ways to increase geriatrics skills, knowledge, and practices among their entire health care workforce. A culture shift toward age-friendly care for older adults across care settings and inclusive of all HCPs may help meet this escalating workforce need.7

The Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) is an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.8,9 AFHS uses a what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility (4Ms) framework to ensure reliable, evidence-based care for older adults (Table 1).10,11 In an AFHS, the 4Ms are integrated into every discipline and care setting for older adults.11 The 4Ms neither replace formal training in geriatrics nor create the level of expertise needed for geriatrics teachers, researchers, and program leaders. However, the systematic approach of AFHS to assess and act on each of the 4Ms offers one solution to expand geriatrics skills and knowledge beyond geriatric care settings in all disciplines by engaging each HCP to meet the needs of older adults.12 To act on what matters, HCPs need to align the care plan with what is important to the older adult.

Hospitals and health care systems are encouraged to begin implementing the 4Ms in ≥ 1 care setting.13 Care settings may get started on a do-it-yourself track or by joining an IHI Action Community, which provides a series of webinars to help adopt the 4Ms over 7 months.14 By creating a plan for how each M will be assessed, documented, and acted on, care settings may earn level 1 recognition from the IHI.14 As of July 2023, there are at least 3100 AFHS participants and > 1900 have achieved level 2 recognition, which requires 3 months of clinical data to demonstrate the impact of the 4Ms.13,14

The main cultural shift of the AFHS movement is to focus on what matters to older adults by prioritizing each older adult’s personal health goals and care preferences across all care settings.9,11 Medication addresses age-appropropriate prescribing, making dose adjustments, if needed, and avoiding/deprescribing high-risk medications that may interfere with what matters, mentation, or mobility. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults is often used as a guide and includes lists of medications that are potentially harmful for older adults.11 Mentation focuses on preventing, identifying, treating, and managing dementia, depression, and delirium across care settings. Mobility includes assisting or encouraging older adults to move safely every day to maintain functional ability and do what matters.15,16 Each of the 4Ms has the potential to improve health outcomes for older adults, reduce waste from low-quality services, and increase the use of cost-effective services.11,17

In March 2020, the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) set the goal for the VHA to be recognized by the IHI as an AFHS.18,19 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities that joined the AFHS movement in 2020 are considered early adopters. We describe early adopter AFHS implementation at Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) hospital, geriatrics assessment clinic (GAC), and Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) and at the Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) HBPC.

Implementing 4Ms Care

The IHI identifies 6 steps in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to reliably practice the 4Ms. eAppendix 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the steps over a 9-month timeline independently taken by BVAHCS and AVAMC to achieve both levels of AFHS recognition.

Step 1: Understand the Current State

In March 2020 the BVAHCS enrolled in the IHI Action Community. Three BVAHCS care settings were identified for the Action Community: the inpatient hospital, GAC (an outpatient clinic), and HBPC. The AVAMC HBPC enrolled in the IHI Action Community in March 2021.

Before joining the AFHS movement, the BVAHCS implemented a hospital-wide delirium standard operating procedure (SOP) whereby every veteran admitted to the 313-bed hospital is screened for delirium risk, with positive screens linked to nursing-led interventions. Nursing leadership supported AFHS due to its recognized value and an exemplary process in place to assess mentation/delirium and background understanding for screening and acting on medication, mobility, and what matters most to the veteran. The BVAHCS GAC, which was led by a single geriatrician, integrated the 4Ms into all geriatrics assessment appointments.

For the BVAHCS HBPC, the 4Ms supported key performance measures, such as fall prevention, patient satisfaction, decreasing medication errors, and identification of cognition and mood disorders. For the AVAMC HBPC, joining the AFHS movement represented an opportunity to improve performance measures, interdisciplinary teamwork, and care coordination for patients. For both HBPC sites, the shift to virtual meeting modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled HBPC team members to garner support for AFHS and collectively develop a 4Ms plan.

Step 2: Describe 4Ms Care

In March 2020 as guided by the Action Community, BVAHCS created a plan for each of its 3 care settings that described assessment tools, frequency, documentation, and responsible team members. All BVAHCS care settings achieved level 1 recognition in April 2020. Of the approximately 300 veterans served by the AVAMC HBPC, 83% are aged > 65 years. They achieved level 1 recognition in August 2021.

Step 3: Design and Adapt Workflows

From April to August 2020, BVAHCS implemented its 4Ms plans. In the hospital, a 4Ms overview was provided with education on the delirium SOP at nursing meetings. Updates were requested to the electronic health record (EHR) templates for the GAC to streamline documentation. For the BVAHCS HBPC, 4Ms assessments were added to the EHR quarterly care plan template, which was updated by all team members (Table 2).

From April through June 2021, the AVAMC HBPC formed teams led by 4Ms champions: what matters was led by a nurse care manager, medication by a nurse practitioner and pharmacist, mentation by a social worker, and mobility by a physical therapist. The champions initially focused on a plan for each M, incorporating all 4Ms as a set for optimal effectiveness into their quarterly care plan meeting using what matters to drive the entire care plan.

Step 4: Provide Care

Each of the 4Ms was to be assessed, documented, and acted on for each veteran within a short period, such as a hospitalization or 1 or 2 outpatient visits. BVAHCS implemented 4Ms care in each care setting from August to October 2020. The AVAMC HBPC implemented 4Ms from July to September 2021.

Step 5: Study Performance

The IHI identifies 3 methods for measuring older adults who receive 4Ms care: real-time observation, chart review, or EHR report. For chart review, the IHI recommends using a random sample to calculate the number of patients who received 4Ms in 1 month, which provides evidence of progress toward reliable practice.

Both facilities used chart review with random sampling. Each setting estimated the number of veterans receiving 4Ms care by multiplying the percentage of sampled charts with documented 4Ms care by unique patient encounters (eAppendix 2).

From August through October 2020, BVAHCS sites reached an estimated 97% of older veterans with complete 4Ms care: hospital, 100%; GAC, 90%; and HBPC, 85%. AVAMC HBPC increased 4Ms care from 52% to 100% between July and September 2021. Both teams demonstrated the feasibility of reliably providing 4Ms care to > 85% of older veterans in these care settings and earned level 2 recognition. Through satisfaction surveys and informal feedback, notable positive changes were evident to veterans, their families, and the VA staff providing 4Ms age-friendly care.

Step 6: Improve and Sustain Care

Each site acknowledged barriers and facilitators for adopting the 4Ms. The COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing barrier for both sites, with teams transitioning to virtual modalities for telehealth visits and team meetings, and higher staff turnover. However, the greater use of technology facilitated 4Ms adoption by allowing physically distant team members to collaborate.

One of the largest barriers was the lack of 4Ms documentation in the EHR, which could not be implemented in the BVAHCS inpatient hospital due to existing standardized nursing templates. Both sites recognized that 4Ms documentation in the EHR for all care settings would facilitate achieving level 2 recognition and tracking and reporting 4Ms care in the future.

Discussion

The AFHS 4Ms approach offers a method to impart geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practice throughout an entire health care system in a short time. The AFHS framework provides a structured pathway to the often daunting challenge of care for complex, multimorbid, and highly heterogeneous older adults. The 4Ms approach promotes the provision of evidence-based care that is reliable, efficient, patient centered, and avoids unwanted care: worthy goals not only for geriatrics but for all members of a high-reliability organization.

Through the implementation of the 4Ms framework, consistent use of AFHS practices, measurement, and feedback, the staff in each VA care setting reported here reached a level of reliability in which at least 85% of patients had all 4Ms addressed. Notably, adoption was strong and improvements in reliably addressing all 4Ms were observed in both geriatrics (HBPC and outpatient clinics) and nongeriatrics (inpatient medicine) settings. Although one might expect that high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in geriatrics-focused VA settings were routinely addressing all 4Ms for most of their patients, our experience was consistent with prior teams indicating that this is often not the case. Although many of these teams were addressing some of the 4Ms in their usual practice, the 4Ms framework facilitated addressing all 4Ms as a set with input from all team members. Most importantly, it fostered a culture of asking the older adult what matters most and documenting, sharing, and aligning this with the care plan. Within 6 months, all VA care settings achieved level 1 recognition, and within 9 months, all achieved level 2 recognition.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned include the importance of identifying, preparing, and supporting a champion to lead this effort; garnering facility and system leadership support at the outset; and integration with the EHR for reliable and efficient data capture, reporting, and feedback. Preparing and supporting champions was achieved through national and individual calls and peer support. Guidance was provided on garnering leadership support, including local needs assessment and data analysis, meeting with leadership to first understand their key challenges and priorities and provide information on the AFHS movement, requesting a follow-up meeting to discuss local needs and data, and exploring how an AFHS might help address one or more of their priorities.

In September 2022, an AFHS 4Ms note template was introduced into the EHR for all VA sites for data capture and reporting, to standardize and facilitate documentation across all age-friendly VA sites, and decrease the reporting burden for staff. This effort is critically important: The ability to document, track, and analyze 4Ms measures, provide feedback, and synergize efforts across systems is vital to design studies to determine whether the AFHS 4Ms approach to care achieves substantive improvements in patient care across settings.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the small sample of care settings, which did not include a skilled nursing or long-term care facility, nor general primary care. Although the short timeframe assessed did not allow us to report on the anticipated clinical outcomes of 4Ms care, it does set up a foundation for evaluation of the 4Ms and EHR integration and dashboard development.

Conclusions

The VHA provides a comprehensive spectrum of geriatrics services and innovative models of care that often serve as exemplars to other health care systems. Implementing the AFHS framework to assess and act on the 4Ms provides a structure for confronting the HCP shortage with geriatrics expertise by infusing geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practices throughout all care settings and disciplines. Enhancing patient-centered care to older veterans through AFHS implementation exemplifies the VHA as a learning health care system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Veterans Health Administration Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care and the clinical staff from the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Healthcare System and the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System for assisting us in this work.

Nearly 50% of living US veterans are aged ≥ 65 years compared with 18.3% of the general population.1,2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, has a vested interest in improving the quality and effectiveness of care for older veterans.3

Health care systems are often unprepared to care for the complex needs of older adults. There are roughly 7300 certified geriatricians practicing in the US, and about 250 new geriatricians are trained each year while the American Geriatrics Society expects > 12,000 geriatricians will be required by 2030.4,5 More geriatricians are needed to serve as the primary health care professionals (HCPs) for older adults.4,6 Health care systems like the VHA must find ways to increase geriatrics skills, knowledge, and practices among their entire health care workforce. A culture shift toward age-friendly care for older adults across care settings and inclusive of all HCPs may help meet this escalating workforce need.7

The Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) is an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.8,9 AFHS uses a what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility (4Ms) framework to ensure reliable, evidence-based care for older adults (Table 1).10,11 In an AFHS, the 4Ms are integrated into every discipline and care setting for older adults.11 The 4Ms neither replace formal training in geriatrics nor create the level of expertise needed for geriatrics teachers, researchers, and program leaders. However, the systematic approach of AFHS to assess and act on each of the 4Ms offers one solution to expand geriatrics skills and knowledge beyond geriatric care settings in all disciplines by engaging each HCP to meet the needs of older adults.12 To act on what matters, HCPs need to align the care plan with what is important to the older adult.

Hospitals and health care systems are encouraged to begin implementing the 4Ms in ≥ 1 care setting.13 Care settings may get started on a do-it-yourself track or by joining an IHI Action Community, which provides a series of webinars to help adopt the 4Ms over 7 months.14 By creating a plan for how each M will be assessed, documented, and acted on, care settings may earn level 1 recognition from the IHI.14 As of July 2023, there are at least 3100 AFHS participants and > 1900 have achieved level 2 recognition, which requires 3 months of clinical data to demonstrate the impact of the 4Ms.13,14

The main cultural shift of the AFHS movement is to focus on what matters to older adults by prioritizing each older adult’s personal health goals and care preferences across all care settings.9,11 Medication addresses age-appropropriate prescribing, making dose adjustments, if needed, and avoiding/deprescribing high-risk medications that may interfere with what matters, mentation, or mobility. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults is often used as a guide and includes lists of medications that are potentially harmful for older adults.11 Mentation focuses on preventing, identifying, treating, and managing dementia, depression, and delirium across care settings. Mobility includes assisting or encouraging older adults to move safely every day to maintain functional ability and do what matters.15,16 Each of the 4Ms has the potential to improve health outcomes for older adults, reduce waste from low-quality services, and increase the use of cost-effective services.11,17

In March 2020, the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) set the goal for the VHA to be recognized by the IHI as an AFHS.18,19 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities that joined the AFHS movement in 2020 are considered early adopters. We describe early adopter AFHS implementation at Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) hospital, geriatrics assessment clinic (GAC), and Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) and at the Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) HBPC.

Implementing 4Ms Care

The IHI identifies 6 steps in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to reliably practice the 4Ms. eAppendix 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the steps over a 9-month timeline independently taken by BVAHCS and AVAMC to achieve both levels of AFHS recognition.

Step 1: Understand the Current State

In March 2020 the BVAHCS enrolled in the IHI Action Community. Three BVAHCS care settings were identified for the Action Community: the inpatient hospital, GAC (an outpatient clinic), and HBPC. The AVAMC HBPC enrolled in the IHI Action Community in March 2021.

Before joining the AFHS movement, the BVAHCS implemented a hospital-wide delirium standard operating procedure (SOP) whereby every veteran admitted to the 313-bed hospital is screened for delirium risk, with positive screens linked to nursing-led interventions. Nursing leadership supported AFHS due to its recognized value and an exemplary process in place to assess mentation/delirium and background understanding for screening and acting on medication, mobility, and what matters most to the veteran. The BVAHCS GAC, which was led by a single geriatrician, integrated the 4Ms into all geriatrics assessment appointments.

For the BVAHCS HBPC, the 4Ms supported key performance measures, such as fall prevention, patient satisfaction, decreasing medication errors, and identification of cognition and mood disorders. For the AVAMC HBPC, joining the AFHS movement represented an opportunity to improve performance measures, interdisciplinary teamwork, and care coordination for patients. For both HBPC sites, the shift to virtual meeting modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled HBPC team members to garner support for AFHS and collectively develop a 4Ms plan.

Step 2: Describe 4Ms Care

In March 2020 as guided by the Action Community, BVAHCS created a plan for each of its 3 care settings that described assessment tools, frequency, documentation, and responsible team members. All BVAHCS care settings achieved level 1 recognition in April 2020. Of the approximately 300 veterans served by the AVAMC HBPC, 83% are aged > 65 years. They achieved level 1 recognition in August 2021.

Step 3: Design and Adapt Workflows

From April to August 2020, BVAHCS implemented its 4Ms plans. In the hospital, a 4Ms overview was provided with education on the delirium SOP at nursing meetings. Updates were requested to the electronic health record (EHR) templates for the GAC to streamline documentation. For the BVAHCS HBPC, 4Ms assessments were added to the EHR quarterly care plan template, which was updated by all team members (Table 2).

From April through June 2021, the AVAMC HBPC formed teams led by 4Ms champions: what matters was led by a nurse care manager, medication by a nurse practitioner and pharmacist, mentation by a social worker, and mobility by a physical therapist. The champions initially focused on a plan for each M, incorporating all 4Ms as a set for optimal effectiveness into their quarterly care plan meeting using what matters to drive the entire care plan.

Step 4: Provide Care

Each of the 4Ms was to be assessed, documented, and acted on for each veteran within a short period, such as a hospitalization or 1 or 2 outpatient visits. BVAHCS implemented 4Ms care in each care setting from August to October 2020. The AVAMC HBPC implemented 4Ms from July to September 2021.

Step 5: Study Performance

The IHI identifies 3 methods for measuring older adults who receive 4Ms care: real-time observation, chart review, or EHR report. For chart review, the IHI recommends using a random sample to calculate the number of patients who received 4Ms in 1 month, which provides evidence of progress toward reliable practice.

Both facilities used chart review with random sampling. Each setting estimated the number of veterans receiving 4Ms care by multiplying the percentage of sampled charts with documented 4Ms care by unique patient encounters (eAppendix 2).

From August through October 2020, BVAHCS sites reached an estimated 97% of older veterans with complete 4Ms care: hospital, 100%; GAC, 90%; and HBPC, 85%. AVAMC HBPC increased 4Ms care from 52% to 100% between July and September 2021. Both teams demonstrated the feasibility of reliably providing 4Ms care to > 85% of older veterans in these care settings and earned level 2 recognition. Through satisfaction surveys and informal feedback, notable positive changes were evident to veterans, their families, and the VA staff providing 4Ms age-friendly care.

Step 6: Improve and Sustain Care

Each site acknowledged barriers and facilitators for adopting the 4Ms. The COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing barrier for both sites, with teams transitioning to virtual modalities for telehealth visits and team meetings, and higher staff turnover. However, the greater use of technology facilitated 4Ms adoption by allowing physically distant team members to collaborate.

One of the largest barriers was the lack of 4Ms documentation in the EHR, which could not be implemented in the BVAHCS inpatient hospital due to existing standardized nursing templates. Both sites recognized that 4Ms documentation in the EHR for all care settings would facilitate achieving level 2 recognition and tracking and reporting 4Ms care in the future.

Discussion

The AFHS 4Ms approach offers a method to impart geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practice throughout an entire health care system in a short time. The AFHS framework provides a structured pathway to the often daunting challenge of care for complex, multimorbid, and highly heterogeneous older adults. The 4Ms approach promotes the provision of evidence-based care that is reliable, efficient, patient centered, and avoids unwanted care: worthy goals not only for geriatrics but for all members of a high-reliability organization.

Through the implementation of the 4Ms framework, consistent use of AFHS practices, measurement, and feedback, the staff in each VA care setting reported here reached a level of reliability in which at least 85% of patients had all 4Ms addressed. Notably, adoption was strong and improvements in reliably addressing all 4Ms were observed in both geriatrics (HBPC and outpatient clinics) and nongeriatrics (inpatient medicine) settings. Although one might expect that high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in geriatrics-focused VA settings were routinely addressing all 4Ms for most of their patients, our experience was consistent with prior teams indicating that this is often not the case. Although many of these teams were addressing some of the 4Ms in their usual practice, the 4Ms framework facilitated addressing all 4Ms as a set with input from all team members. Most importantly, it fostered a culture of asking the older adult what matters most and documenting, sharing, and aligning this with the care plan. Within 6 months, all VA care settings achieved level 1 recognition, and within 9 months, all achieved level 2 recognition.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned include the importance of identifying, preparing, and supporting a champion to lead this effort; garnering facility and system leadership support at the outset; and integration with the EHR for reliable and efficient data capture, reporting, and feedback. Preparing and supporting champions was achieved through national and individual calls and peer support. Guidance was provided on garnering leadership support, including local needs assessment and data analysis, meeting with leadership to first understand their key challenges and priorities and provide information on the AFHS movement, requesting a follow-up meeting to discuss local needs and data, and exploring how an AFHS might help address one or more of their priorities.

In September 2022, an AFHS 4Ms note template was introduced into the EHR for all VA sites for data capture and reporting, to standardize and facilitate documentation across all age-friendly VA sites, and decrease the reporting burden for staff. This effort is critically important: The ability to document, track, and analyze 4Ms measures, provide feedback, and synergize efforts across systems is vital to design studies to determine whether the AFHS 4Ms approach to care achieves substantive improvements in patient care across settings.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the small sample of care settings, which did not include a skilled nursing or long-term care facility, nor general primary care. Although the short timeframe assessed did not allow us to report on the anticipated clinical outcomes of 4Ms care, it does set up a foundation for evaluation of the 4Ms and EHR integration and dashboard development.

Conclusions

The VHA provides a comprehensive spectrum of geriatrics services and innovative models of care that often serve as exemplars to other health care systems. Implementing the AFHS framework to assess and act on the 4Ms provides a structure for confronting the HCP shortage with geriatrics expertise by infusing geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practices throughout all care settings and disciplines. Enhancing patient-centered care to older veterans through AFHS implementation exemplifies the VHA as a learning health care system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Veterans Health Administration Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care and the clinical staff from the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Healthcare System and the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System for assisting us in this work.

1. US Census Bureau. Older Americans month: May 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/stories/older-americans-month.html

2. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. July 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

3. O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):105-121. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

4. Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):219-225. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470

5. ChenMed. The physician shortage in geriatrics. March 18, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.chenmed.com/blog/physician-shortage-geriatrics

6. American Geriatrics Society. Projected future need for geriatricians. Updated May 2016. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Projected-Future-Need-for-Geriatricians.pdf 7. Carmody J, Black K, Bonner A, Wolfe M, Fulmer T. Advancing gerontological nursing at the intersection of age-friendly communities, health systems, and public health. J Gerontol Nurs. 2021;47(3):13-17. doi:10.3928/00989134-20210125-01

8. Lesser S, Zakharkin S, Louie C, Escobedo MR, Whyte J, Fulmer T. Clinician knowledge and behaviors related to the 4Ms framework of Age‐Friendly Health Systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(3):789-800. doi:10.1111/jgs.17571

9. Edelman LS, Drost J, Moone RP, et al. Applying the Age-Friendly Health System framework to long term care settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):141-145. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1558-2

10. Emery-Tiburcio EE, Mack L, Zonsius MC, Carbonell E, Newman M. The 4Ms of an Age-Friendly Health System: an evidence-based framework to ensure older adults receive the highest quality care. Home Healthc Now. 2022;40(5):252-257. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000001113

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

12. Mate KS, Berman A, Laderman M, Kabcenell A, Fulmer T. Creating age-friendly health systems – a vision for better care of older adults. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6(1):4-6. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.05.005

13. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. What is an Age-Friendly Health System? Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

14. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health systems recognized by IHI. Updated September 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/recognized-systems.aspx

15. Burke RE, Ashcraft LE, Manges K, et al. What matters when it comes to measuring Age‐Friendly Health System transformation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(10):2775-2785. doi:10.1111/jgs.18002

16. Wang J, Shen JY, Conwell Y, et al. How “age-friendly” are deprescribing interventions? A scoping review of deprescribing trials. Health Serv Res. 202;58(suppl 1):123-138. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14083

17. Pohnert AM, Schiltz NK, Pino L, et al. Achievement of age‐friendly health systems committed to care excellence designation in a convenient care health care system. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 (suppl 1):89-99. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14071

18. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2022;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

19. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age‐friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

1. US Census Bureau. Older Americans month: May 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/stories/older-americans-month.html

2. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. July 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

3. O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):105-121. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

4. Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):219-225. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470

5. ChenMed. The physician shortage in geriatrics. March 18, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.chenmed.com/blog/physician-shortage-geriatrics

6. American Geriatrics Society. Projected future need for geriatricians. Updated May 2016. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Projected-Future-Need-for-Geriatricians.pdf 7. Carmody J, Black K, Bonner A, Wolfe M, Fulmer T. Advancing gerontological nursing at the intersection of age-friendly communities, health systems, and public health. J Gerontol Nurs. 2021;47(3):13-17. doi:10.3928/00989134-20210125-01

8. Lesser S, Zakharkin S, Louie C, Escobedo MR, Whyte J, Fulmer T. Clinician knowledge and behaviors related to the 4Ms framework of Age‐Friendly Health Systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(3):789-800. doi:10.1111/jgs.17571

9. Edelman LS, Drost J, Moone RP, et al. Applying the Age-Friendly Health System framework to long term care settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):141-145. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1558-2

10. Emery-Tiburcio EE, Mack L, Zonsius MC, Carbonell E, Newman M. The 4Ms of an Age-Friendly Health System: an evidence-based framework to ensure older adults receive the highest quality care. Home Healthc Now. 2022;40(5):252-257. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000001113

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

12. Mate KS, Berman A, Laderman M, Kabcenell A, Fulmer T. Creating age-friendly health systems – a vision for better care of older adults. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6(1):4-6. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.05.005

13. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. What is an Age-Friendly Health System? Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

14. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health systems recognized by IHI. Updated September 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/recognized-systems.aspx

15. Burke RE, Ashcraft LE, Manges K, et al. What matters when it comes to measuring Age‐Friendly Health System transformation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(10):2775-2785. doi:10.1111/jgs.18002

16. Wang J, Shen JY, Conwell Y, et al. How “age-friendly” are deprescribing interventions? A scoping review of deprescribing trials. Health Serv Res. 202;58(suppl 1):123-138. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14083

17. Pohnert AM, Schiltz NK, Pino L, et al. Achievement of age‐friendly health systems committed to care excellence designation in a convenient care health care system. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 (suppl 1):89-99. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14071

18. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2022;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

19. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age‐friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

Implementation of an Automated Phone Call Distribution System in an Inpatient Pharmacy Setting

Pharmacy call centers have been successfully implemented in outpatient and specialty pharmacy settings.1 A centralized pharmacy call center gives patients immediate access to a pharmacist who can view their health records to answer specific questions or fulfill medication renewal requests.2-4 Little literature exists to describe its use in an inpatient setting.

Inpatient pharmacies receive numerous calls from health care professionals and patients. Challenges related to phone calls in the inpatient pharmacy setting may include interruptions, distractions, low accountability, poor efficiency, lack of optimal resources, and staffing.5 An unequal distribution and lack of accountability may exist when answering phone calls for the inpatient pharmacy team, which may contribute to long hold times and call abandonment rates. Phone calls also may be directed inefficiently between clinical pharmacists (CPs) and pharmacy technicians. Team member time related to answering phone calls may not be captured or measured.

The Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital (EHJVAH) in Illinois offers primary, extended, and specialty care and is a tertiary care referral center. The facility operates 483 beds and serves 6 community-based outpatient clinics.

Implementation

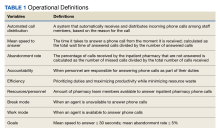

A new inpatient pharmacy service phone line extension was implemented. Data used to report quality metrics were obtained from the Global Navigator (GNAV), an information system that records calls, tracks the performance of agents, and coordinates personnel scheduling. The effectiveness of the ACD system was evaluated by quality metric goals of mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and mean abandonment rate ≤ 5%. This project was determined to be quality improvement and was not reviewed by the EHJVAH Institutional Review Board.

The ACD system was set up in December 2020. After a 1-month implementation period, metrics were reported to the inpatient pharmacy team and leadership. By January 2021, EHJVAH fully implemented an ACD phone system operated by inpatient pharmacy technicians and CPs. EHJVAH inpatient pharmacy includes CPs who practice without a scope of practice and board-certified pharmacy technicians in 3 shifts. The CPs and pharmacy technicians work in the central pharmacy (the main pharmacy and inpatient pharmacy vault) or are decentralized with responsibility for answering phone calls and making deliveries (pharmacy technicians).

The pharmacy leadership team decided to implement 1 phone line with 2 ACD splits. The first split was directed to pharmacy technicians and the second to CPs. The intention was to streamline calls to be directed to proper team members within the inpatient pharmacy. The CP line also was designed to back up the pharmacy technician line. These calls were equally distributed among staff based on a standard algorithm. The pharmacy greeting stated, “Thank you for contacting the inpatient pharmacy at Hines VA Hospital. For missing doses, unit stock requests, or to speak with a pharmacy technician, please press 1. For clinical questions, order verification, or to speak with a pharmacist, please press 2.” Each inpatient pharmacy team member had a unique system login.

Fourteen ACD phone stations were established in the main pharmacy and in decentralized locations for order verification. The stations were distributed across the pharmacy service to optimize workload, space, and resources.

Training and Communication

Before implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, the CPs and pharmacy technicians received mandatory ACD training. After the training, pharmacy team members were required to sign off on the training document to indicate that they had completed the course. The pharmacy team was trained on the importance of staffing the phones continuously. As a 24-hour pharmacy service in the acute care setting, any call may be critical for patient care.

A hospital-wide memorandum was distributed via email to all unit managers and hospital staff to educate them on the new ACD phone system, which included a new phone line extension for the inpatient pharmacy. Additionally, the inpatient pharmacy team was trained on the proper way of communicating the ACD phone system process with the hospital staff. The inpatient pharmacy team was notified that there would be an educational period to explain the queue process to hospital staff. Occasionally, hospital staff believed they were speaking to an automated system and hung up before their call was answered. The inpatient pharmacy team was instructed to notify the hospital staff to stay on the line since their call would be answered in the order it was received. Once the inpatient pharmacy team received proper training and felt comfortable with the phone system, it was set up and integrated into the workflow.

Postimplementation Evaluation

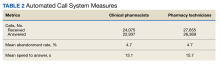

Inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system data were collected for 2021. To evaluate the effectiveness of an ACD system, the pharmacy leadership team set up the following metrics and goals for inpatient CPs and inpatient pharmacy technicians for monthly call volume/abandonment rate, mean speed to answer, mean call volume by shift, and the mean abandonment rate by shift.

Inpatient pharmacy technicians answered 27,655 calls with a mean call abandonment rate of 4.7%. and a mean 15.6 seconds to answer.

Discussion

Since implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system in January 2021, there have been successes and challenges. The implementation increased accountability and efficiency when answering pharmacy phone calls. An ACD uses an algorithm that ensures equitable distribution of phone calls between CPs and pharmacy technicians. Through this algorithm, the pharmacy team is held more accountable when answering incoming calls. Distributing phone calls equally allows for optimization and balances the workload. The ACD phone system also improved efficiency when answering incoming calls. By incorporating splits when a patient or health care professional calls, ACD routes the question to the appropriate staff member. As a result, CPs spend less time answering questions meant for pharmacy technicians and instead can answer clinical or order verification questions more efficiently.

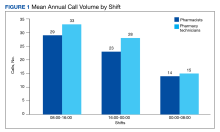

ACD data also allow pharmacy leadership to assess staffing needs, depending on the call volume. Based on ACD data, the busiest time of day was 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Based on this information, pharmacy leadership plans to staff more appropriately to have more pharmacy technicians working during the first shift to attend to phone calls.

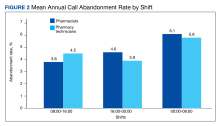

The mean call abandonment rate was 4.7% for both CPs and pharmacy technicians, which met the ≤ 5% goal. The highest call abandonment rate was from midnight to 8

Pharmacy technicians handled a higher total call volume, which may be attributed to more phone calls related to missing doses or unit stock requests compared with clinical questions or order verifications. This information may be beneficial to identify opportunities to improve pharmacy operations.

The main challenges encountered in the ACD implementation process were hardware installation and communication with hospital staff about the changes in the inpatient pharmacy phone system. To implement the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, previous telephones and hardware were removed and replaced. Initially, hardware and installation delays made it difficult for the ACD phone system to operate efficiently in the early months of its implementation. The inpatient pharmacy team depends on the telecommunications system and computers for their daily activities. Delays and issues with the hardware and ACD phone system made it more difficult to provide patient care.

Communication is a continuous challenge to ensure that hospital staff are notified of the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone number. Over time, the understanding and use of the new ACD phone system have increased dramatically, but there are still opportunities to capture any misdirected calls. Informal feedback was obtained at pharmacy huddles and 1-on-1 discussions with pharmacy staff, and the opinions were mixed. Members of the pharmacy staff expressed that the ACD phone system set up an effective way to triage phone calls. Another positive comment was that the system created a means of accountability for pharmacy phone calls. Critical feedback included challenges with triaging phone calls to appropriate pharmacists, because calls are assigned based on an algorithm, whereas clinical coverage is determined by designated unit daily assignments.

Limitations

There are potential limitations to this quality improvement project. This phone system may not apply to all inpatient hospital pharmacy settings. Potential limitations for implementation at other institutions may include but are not limited to, differing pharmacy practice models (centralized vs decentralized), implementation costs, and internal resources.

Future Goals

To improve the quality of service provided to patients and other hospital staff, the pharmacy leadership team can use the data to ensure that inpatient pharmacy technician resources are being used effectively during times of day with the greatest number of incoming ACD calls. The ACD phone system helps determine whether current resources are being used most efficiently and if they are not, can help identify areas of improvement.

The pharmacy leadership team plans on using reports for pharmacy team members to monitor performance. Reports on individual agent activity capture workload; this may be used as a performance-related metric for future performance plans.

Conclusions

The inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system at EHJVAH is a promising application of available technology. The implementation of the ACD system improved accountability, efficiency, work distribution, and the allocation of resources in the inpatient pharmacy service. The ACD phone system has yielded positive performance metrics including mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and abandonment rate ≤ 5% over 12 months after implementation. With time, users of the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system will become more comfortable with the technology, thus further improving the patient health care quality.

1. Rim MH, Thomas KC, Chandramouli J, Barrus SA, Nickman NA. Implementation and quality assessment of a pharmacy services call center for outpatient pharmacies and specialty pharmacy services in an academic health system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(10):633-641. doi:10.2146/ajhp170319

2. Patterson BJ, Doucette WR, Urmie JM, McDonough RP. Exploring relationships among pharmacy service use, patronage motives, and patient satisfaction. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013;53(4):382-389. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12100

3. Walker DM, Sieck CJ, Menser T, Huerta TR, Scheck McAlearney A. Information technology to support patient engagement: where do we stand and where can we go?. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1088-1094. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocx043

4. Menichetti J, Libreri C, Lozza E, Graffigna G. Giving patients a starring role in their own care: a bibliometric analysis of the on-going literature debate. Health Expect. 2016;19(3):516-526. doi:10.1111/hex.12299

5. Raimbault M, Guérin A, Caron É, Lebel D, Bussières J-F. Identifying and reducing distractions and interruptions in a pharmacy department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(3):186-190. doi:10.2146/ajhp120344

Pharmacy call centers have been successfully implemented in outpatient and specialty pharmacy settings.1 A centralized pharmacy call center gives patients immediate access to a pharmacist who can view their health records to answer specific questions or fulfill medication renewal requests.2-4 Little literature exists to describe its use in an inpatient setting.

Inpatient pharmacies receive numerous calls from health care professionals and patients. Challenges related to phone calls in the inpatient pharmacy setting may include interruptions, distractions, low accountability, poor efficiency, lack of optimal resources, and staffing.5 An unequal distribution and lack of accountability may exist when answering phone calls for the inpatient pharmacy team, which may contribute to long hold times and call abandonment rates. Phone calls also may be directed inefficiently between clinical pharmacists (CPs) and pharmacy technicians. Team member time related to answering phone calls may not be captured or measured.

The Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital (EHJVAH) in Illinois offers primary, extended, and specialty care and is a tertiary care referral center. The facility operates 483 beds and serves 6 community-based outpatient clinics.

Implementation

A new inpatient pharmacy service phone line extension was implemented. Data used to report quality metrics were obtained from the Global Navigator (GNAV), an information system that records calls, tracks the performance of agents, and coordinates personnel scheduling. The effectiveness of the ACD system was evaluated by quality metric goals of mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and mean abandonment rate ≤ 5%. This project was determined to be quality improvement and was not reviewed by the EHJVAH Institutional Review Board.

The ACD system was set up in December 2020. After a 1-month implementation period, metrics were reported to the inpatient pharmacy team and leadership. By January 2021, EHJVAH fully implemented an ACD phone system operated by inpatient pharmacy technicians and CPs. EHJVAH inpatient pharmacy includes CPs who practice without a scope of practice and board-certified pharmacy technicians in 3 shifts. The CPs and pharmacy technicians work in the central pharmacy (the main pharmacy and inpatient pharmacy vault) or are decentralized with responsibility for answering phone calls and making deliveries (pharmacy technicians).

The pharmacy leadership team decided to implement 1 phone line with 2 ACD splits. The first split was directed to pharmacy technicians and the second to CPs. The intention was to streamline calls to be directed to proper team members within the inpatient pharmacy. The CP line also was designed to back up the pharmacy technician line. These calls were equally distributed among staff based on a standard algorithm. The pharmacy greeting stated, “Thank you for contacting the inpatient pharmacy at Hines VA Hospital. For missing doses, unit stock requests, or to speak with a pharmacy technician, please press 1. For clinical questions, order verification, or to speak with a pharmacist, please press 2.” Each inpatient pharmacy team member had a unique system login.

Fourteen ACD phone stations were established in the main pharmacy and in decentralized locations for order verification. The stations were distributed across the pharmacy service to optimize workload, space, and resources.

Training and Communication

Before implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, the CPs and pharmacy technicians received mandatory ACD training. After the training, pharmacy team members were required to sign off on the training document to indicate that they had completed the course. The pharmacy team was trained on the importance of staffing the phones continuously. As a 24-hour pharmacy service in the acute care setting, any call may be critical for patient care.

A hospital-wide memorandum was distributed via email to all unit managers and hospital staff to educate them on the new ACD phone system, which included a new phone line extension for the inpatient pharmacy. Additionally, the inpatient pharmacy team was trained on the proper way of communicating the ACD phone system process with the hospital staff. The inpatient pharmacy team was notified that there would be an educational period to explain the queue process to hospital staff. Occasionally, hospital staff believed they were speaking to an automated system and hung up before their call was answered. The inpatient pharmacy team was instructed to notify the hospital staff to stay on the line since their call would be answered in the order it was received. Once the inpatient pharmacy team received proper training and felt comfortable with the phone system, it was set up and integrated into the workflow.

Postimplementation Evaluation

Inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system data were collected for 2021. To evaluate the effectiveness of an ACD system, the pharmacy leadership team set up the following metrics and goals for inpatient CPs and inpatient pharmacy technicians for monthly call volume/abandonment rate, mean speed to answer, mean call volume by shift, and the mean abandonment rate by shift.

Inpatient pharmacy technicians answered 27,655 calls with a mean call abandonment rate of 4.7%. and a mean 15.6 seconds to answer.

Discussion

Since implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system in January 2021, there have been successes and challenges. The implementation increased accountability and efficiency when answering pharmacy phone calls. An ACD uses an algorithm that ensures equitable distribution of phone calls between CPs and pharmacy technicians. Through this algorithm, the pharmacy team is held more accountable when answering incoming calls. Distributing phone calls equally allows for optimization and balances the workload. The ACD phone system also improved efficiency when answering incoming calls. By incorporating splits when a patient or health care professional calls, ACD routes the question to the appropriate staff member. As a result, CPs spend less time answering questions meant for pharmacy technicians and instead can answer clinical or order verification questions more efficiently.

ACD data also allow pharmacy leadership to assess staffing needs, depending on the call volume. Based on ACD data, the busiest time of day was 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Based on this information, pharmacy leadership plans to staff more appropriately to have more pharmacy technicians working during the first shift to attend to phone calls.

The mean call abandonment rate was 4.7% for both CPs and pharmacy technicians, which met the ≤ 5% goal. The highest call abandonment rate was from midnight to 8

Pharmacy technicians handled a higher total call volume, which may be attributed to more phone calls related to missing doses or unit stock requests compared with clinical questions or order verifications. This information may be beneficial to identify opportunities to improve pharmacy operations.

The main challenges encountered in the ACD implementation process were hardware installation and communication with hospital staff about the changes in the inpatient pharmacy phone system. To implement the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, previous telephones and hardware were removed and replaced. Initially, hardware and installation delays made it difficult for the ACD phone system to operate efficiently in the early months of its implementation. The inpatient pharmacy team depends on the telecommunications system and computers for their daily activities. Delays and issues with the hardware and ACD phone system made it more difficult to provide patient care.

Communication is a continuous challenge to ensure that hospital staff are notified of the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone number. Over time, the understanding and use of the new ACD phone system have increased dramatically, but there are still opportunities to capture any misdirected calls. Informal feedback was obtained at pharmacy huddles and 1-on-1 discussions with pharmacy staff, and the opinions were mixed. Members of the pharmacy staff expressed that the ACD phone system set up an effective way to triage phone calls. Another positive comment was that the system created a means of accountability for pharmacy phone calls. Critical feedback included challenges with triaging phone calls to appropriate pharmacists, because calls are assigned based on an algorithm, whereas clinical coverage is determined by designated unit daily assignments.

Limitations

There are potential limitations to this quality improvement project. This phone system may not apply to all inpatient hospital pharmacy settings. Potential limitations for implementation at other institutions may include but are not limited to, differing pharmacy practice models (centralized vs decentralized), implementation costs, and internal resources.

Future Goals

To improve the quality of service provided to patients and other hospital staff, the pharmacy leadership team can use the data to ensure that inpatient pharmacy technician resources are being used effectively during times of day with the greatest number of incoming ACD calls. The ACD phone system helps determine whether current resources are being used most efficiently and if they are not, can help identify areas of improvement.

The pharmacy leadership team plans on using reports for pharmacy team members to monitor performance. Reports on individual agent activity capture workload; this may be used as a performance-related metric for future performance plans.

Conclusions

The inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system at EHJVAH is a promising application of available technology. The implementation of the ACD system improved accountability, efficiency, work distribution, and the allocation of resources in the inpatient pharmacy service. The ACD phone system has yielded positive performance metrics including mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and abandonment rate ≤ 5% over 12 months after implementation. With time, users of the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system will become more comfortable with the technology, thus further improving the patient health care quality.

Pharmacy call centers have been successfully implemented in outpatient and specialty pharmacy settings.1 A centralized pharmacy call center gives patients immediate access to a pharmacist who can view their health records to answer specific questions or fulfill medication renewal requests.2-4 Little literature exists to describe its use in an inpatient setting.

Inpatient pharmacies receive numerous calls from health care professionals and patients. Challenges related to phone calls in the inpatient pharmacy setting may include interruptions, distractions, low accountability, poor efficiency, lack of optimal resources, and staffing.5 An unequal distribution and lack of accountability may exist when answering phone calls for the inpatient pharmacy team, which may contribute to long hold times and call abandonment rates. Phone calls also may be directed inefficiently between clinical pharmacists (CPs) and pharmacy technicians. Team member time related to answering phone calls may not be captured or measured.

The Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital (EHJVAH) in Illinois offers primary, extended, and specialty care and is a tertiary care referral center. The facility operates 483 beds and serves 6 community-based outpatient clinics.

Implementation

A new inpatient pharmacy service phone line extension was implemented. Data used to report quality metrics were obtained from the Global Navigator (GNAV), an information system that records calls, tracks the performance of agents, and coordinates personnel scheduling. The effectiveness of the ACD system was evaluated by quality metric goals of mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and mean abandonment rate ≤ 5%. This project was determined to be quality improvement and was not reviewed by the EHJVAH Institutional Review Board.

The ACD system was set up in December 2020. After a 1-month implementation period, metrics were reported to the inpatient pharmacy team and leadership. By January 2021, EHJVAH fully implemented an ACD phone system operated by inpatient pharmacy technicians and CPs. EHJVAH inpatient pharmacy includes CPs who practice without a scope of practice and board-certified pharmacy technicians in 3 shifts. The CPs and pharmacy technicians work in the central pharmacy (the main pharmacy and inpatient pharmacy vault) or are decentralized with responsibility for answering phone calls and making deliveries (pharmacy technicians).

The pharmacy leadership team decided to implement 1 phone line with 2 ACD splits. The first split was directed to pharmacy technicians and the second to CPs. The intention was to streamline calls to be directed to proper team members within the inpatient pharmacy. The CP line also was designed to back up the pharmacy technician line. These calls were equally distributed among staff based on a standard algorithm. The pharmacy greeting stated, “Thank you for contacting the inpatient pharmacy at Hines VA Hospital. For missing doses, unit stock requests, or to speak with a pharmacy technician, please press 1. For clinical questions, order verification, or to speak with a pharmacist, please press 2.” Each inpatient pharmacy team member had a unique system login.

Fourteen ACD phone stations were established in the main pharmacy and in decentralized locations for order verification. The stations were distributed across the pharmacy service to optimize workload, space, and resources.

Training and Communication

Before implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, the CPs and pharmacy technicians received mandatory ACD training. After the training, pharmacy team members were required to sign off on the training document to indicate that they had completed the course. The pharmacy team was trained on the importance of staffing the phones continuously. As a 24-hour pharmacy service in the acute care setting, any call may be critical for patient care.