User login

Can Vitamin D Supplements Help With Hypertension?

Q) One of my patients came in and said he had read that vitamin D supplementation will help with hypertension. Now he wants to quit his blood pressure meds and use vitamin D instead. Do you have any background on this?

Vitamin D is critical for utilization of calcium, a vital nutrient for multiple metabolic and cellular processes; deficiency is associated with worsening of autoimmune disorders, osteoporosis, and certain cardiovascular conditions, among others.7 An association between vitamin D level and blood pressure has been recognized for some time, but the pathophysiology is not well understood.

A literature review of studies from 1988 to 2013 found contradictory results regarding vitamin D deficiency and concurrent elevated blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic), as well as the impact on blood pressure with restoration of vitamin D levels. The findings were limited by several factors, including differences in study design, variables evaluated, and type of vitamin D compound used. The results suggested a link between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, fibroblast growth factor 23/klotho axis, and vitamin D level.8

A study of 158 subjects (98 with newly diagnosed essential hypertension, 60 with normal blood pressure) found significantly lower 25(OH)D3 serum levels in hypertensive patients. Furthermore, the 25(OH)D3 level was significantly correlated with both systolic (r = –0.33) and diastolic blood pressure (r = –0.26). Using multiple regression analysis, after adjustment for age, smoking status, and BMI, the impact of 25(OH)D3 level accounted for 10% of the variation in systolic blood pressure.9

In a mendelian randomization study of 108,173 subjects from 35 studies, an inverse association between vitamin D level and systolic blood pressure (P = .0003) was found. A reduced risk for essential hypertension with increased vitamin D level (P = .0003) was also noted. However, no association was found between increasing vitamin D level and a reduction in diastolic blood pressure

(P = .37).10

With the ever-increasing access to health information from sources such as “Doctor Google,” it can be difficult for a non–health care professional to separate hype from evidence-based recommendations. While current evidence suggests optimal vitamin D levels may be beneficial for improving blood pressure control and may be a useful adjunctive therapy, there is no evidence to support discontinuing antihypertensive therapy and replacing it with vitamin D therapy.

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, South Charleston, West Virginia

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Q) One of my patients came in and said he had read that vitamin D supplementation will help with hypertension. Now he wants to quit his blood pressure meds and use vitamin D instead. Do you have any background on this?

Vitamin D is critical for utilization of calcium, a vital nutrient for multiple metabolic and cellular processes; deficiency is associated with worsening of autoimmune disorders, osteoporosis, and certain cardiovascular conditions, among others.7 An association between vitamin D level and blood pressure has been recognized for some time, but the pathophysiology is not well understood.

A literature review of studies from 1988 to 2013 found contradictory results regarding vitamin D deficiency and concurrent elevated blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic), as well as the impact on blood pressure with restoration of vitamin D levels. The findings were limited by several factors, including differences in study design, variables evaluated, and type of vitamin D compound used. The results suggested a link between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, fibroblast growth factor 23/klotho axis, and vitamin D level.8

A study of 158 subjects (98 with newly diagnosed essential hypertension, 60 with normal blood pressure) found significantly lower 25(OH)D3 serum levels in hypertensive patients. Furthermore, the 25(OH)D3 level was significantly correlated with both systolic (r = –0.33) and diastolic blood pressure (r = –0.26). Using multiple regression analysis, after adjustment for age, smoking status, and BMI, the impact of 25(OH)D3 level accounted for 10% of the variation in systolic blood pressure.9

In a mendelian randomization study of 108,173 subjects from 35 studies, an inverse association between vitamin D level and systolic blood pressure (P = .0003) was found. A reduced risk for essential hypertension with increased vitamin D level (P = .0003) was also noted. However, no association was found between increasing vitamin D level and a reduction in diastolic blood pressure

(P = .37).10

With the ever-increasing access to health information from sources such as “Doctor Google,” it can be difficult for a non–health care professional to separate hype from evidence-based recommendations. While current evidence suggests optimal vitamin D levels may be beneficial for improving blood pressure control and may be a useful adjunctive therapy, there is no evidence to support discontinuing antihypertensive therapy and replacing it with vitamin D therapy.

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, South Charleston, West Virginia

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Q) One of my patients came in and said he had read that vitamin D supplementation will help with hypertension. Now he wants to quit his blood pressure meds and use vitamin D instead. Do you have any background on this?

Vitamin D is critical for utilization of calcium, a vital nutrient for multiple metabolic and cellular processes; deficiency is associated with worsening of autoimmune disorders, osteoporosis, and certain cardiovascular conditions, among others.7 An association between vitamin D level and blood pressure has been recognized for some time, but the pathophysiology is not well understood.

A literature review of studies from 1988 to 2013 found contradictory results regarding vitamin D deficiency and concurrent elevated blood pressure (systolic and/or diastolic), as well as the impact on blood pressure with restoration of vitamin D levels. The findings were limited by several factors, including differences in study design, variables evaluated, and type of vitamin D compound used. The results suggested a link between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, fibroblast growth factor 23/klotho axis, and vitamin D level.8

A study of 158 subjects (98 with newly diagnosed essential hypertension, 60 with normal blood pressure) found significantly lower 25(OH)D3 serum levels in hypertensive patients. Furthermore, the 25(OH)D3 level was significantly correlated with both systolic (r = –0.33) and diastolic blood pressure (r = –0.26). Using multiple regression analysis, after adjustment for age, smoking status, and BMI, the impact of 25(OH)D3 level accounted for 10% of the variation in systolic blood pressure.9

In a mendelian randomization study of 108,173 subjects from 35 studies, an inverse association between vitamin D level and systolic blood pressure (P = .0003) was found. A reduced risk for essential hypertension with increased vitamin D level (P = .0003) was also noted. However, no association was found between increasing vitamin D level and a reduction in diastolic blood pressure

(P = .37).10

With the ever-increasing access to health information from sources such as “Doctor Google,” it can be difficult for a non–health care professional to separate hype from evidence-based recommendations. While current evidence suggests optimal vitamin D levels may be beneficial for improving blood pressure control and may be a useful adjunctive therapy, there is no evidence to support discontinuing antihypertensive therapy and replacing it with vitamin D therapy.

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, South Charleston, West Virginia

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Megestrol Acetate for CKD and Dialysis Patients

Q) Some of my CKD patients are malnourished; in fact, some of those on dialysis do not eat well and have low albumin levels. Previously in this column, it was stated that higher albumin levels (> 4 g/dL) confer survival benefits to dialysis patients. Should I consider prescribing megestrol acetate to improve appetite? If I do prescribe it, what dose is safe for CKD and dialysis patients?

Malnutrition affects one-third of dialysis patients,1 and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) is common in those with stage 5 CKD. Albumin is used as an indicator of MICS in dialysis patients; however, since other factors (stress, infection, inflammation, comorbidities) affect nutritional status,2 serum albumin alone may not be sufficient to assess it.

In fact, a recent consensus statement on malnutrition from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition excluded serum albumin as a diagnostic characteristic; the criteria included percentage of energy requirement, percentage of weight loss and time frame, loss of body fat and muscle mass, presence of edema, and reduced grip strength.3 These may be better measures of malnutrition in dialysis patients and could be used as criteria for determining when to prescribe an appetite stimulant, such as megestrol acetate.

In recent years, megestrol acetate (an antineoplastic drug) has been used to improve appetite, weight, albumin levels, and MICS in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.1,4-6 Rammohan et al found significant increases in weight, BMI, body fat, triceps skinfold thickness, protein/energy intake, and serum albumin in 10 dialysis patients who took megestrol acetate (400 mg/d) for 16 weeks.4

Continue for megestrol acetate's effects >>

In a 20-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Yeh et al found significant increases in weight, body fat, and fat-free mass in elderly hemodialysis patients receiving megestrol acetate (800 mg/d). The treatment group also demonstrated greater improvement in ability to exercise.5

Monfared and colleagues looked specifically at megestrol acetate’s effect on serum albumin levels in dialysis patients.1 Using a much lower dose (40 mg bid for two months), they found a significant increase in serum albumin in the treatment group. Although an increase in appetite was noted, the researchers did not observe any significant change in total weight following treatment.1

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of Renal Nutrition, Golebiewska et al reported their use of megestrol acetate in maintenance hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients.6 Hypoalbuminemic patients were given megestrol acetate (160 mg/d). Significant increases in weight, BMI, subjective global assessment scores (a measure of nutritional status based on clinical indices such as weight, appetite, muscle, and fat mass), and serum albumin levels were seen. Only 12 of the 32 patients completed the study; the others dropped out due to adverse effects, including high intradialytic weight gain (the amount of fluid gained between dialysis sessions), dyspnea, diarrhea, and nausea.6

Currently, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the most effective dosage of megestrol acetate. Furthermore, evidence is lacking as to whether megestrol acetate–induced increases in appetite, oral intake, weight, and serum albumin level bestow any survival benefit or affect outcomes in dialysis patients.4 However, the increased sense of well-being a patient experiences when appetite returns and weight is restored may be worth the effort.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Q) Some of my CKD patients are malnourished; in fact, some of those on dialysis do not eat well and have low albumin levels. Previously in this column, it was stated that higher albumin levels (> 4 g/dL) confer survival benefits to dialysis patients. Should I consider prescribing megestrol acetate to improve appetite? If I do prescribe it, what dose is safe for CKD and dialysis patients?

Malnutrition affects one-third of dialysis patients,1 and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) is common in those with stage 5 CKD. Albumin is used as an indicator of MICS in dialysis patients; however, since other factors (stress, infection, inflammation, comorbidities) affect nutritional status,2 serum albumin alone may not be sufficient to assess it.

In fact, a recent consensus statement on malnutrition from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition excluded serum albumin as a diagnostic characteristic; the criteria included percentage of energy requirement, percentage of weight loss and time frame, loss of body fat and muscle mass, presence of edema, and reduced grip strength.3 These may be better measures of malnutrition in dialysis patients and could be used as criteria for determining when to prescribe an appetite stimulant, such as megestrol acetate.

In recent years, megestrol acetate (an antineoplastic drug) has been used to improve appetite, weight, albumin levels, and MICS in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.1,4-6 Rammohan et al found significant increases in weight, BMI, body fat, triceps skinfold thickness, protein/energy intake, and serum albumin in 10 dialysis patients who took megestrol acetate (400 mg/d) for 16 weeks.4

Continue for megestrol acetate's effects >>

In a 20-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Yeh et al found significant increases in weight, body fat, and fat-free mass in elderly hemodialysis patients receiving megestrol acetate (800 mg/d). The treatment group also demonstrated greater improvement in ability to exercise.5

Monfared and colleagues looked specifically at megestrol acetate’s effect on serum albumin levels in dialysis patients.1 Using a much lower dose (40 mg bid for two months), they found a significant increase in serum albumin in the treatment group. Although an increase in appetite was noted, the researchers did not observe any significant change in total weight following treatment.1

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of Renal Nutrition, Golebiewska et al reported their use of megestrol acetate in maintenance hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients.6 Hypoalbuminemic patients were given megestrol acetate (160 mg/d). Significant increases in weight, BMI, subjective global assessment scores (a measure of nutritional status based on clinical indices such as weight, appetite, muscle, and fat mass), and serum albumin levels were seen. Only 12 of the 32 patients completed the study; the others dropped out due to adverse effects, including high intradialytic weight gain (the amount of fluid gained between dialysis sessions), dyspnea, diarrhea, and nausea.6

Currently, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the most effective dosage of megestrol acetate. Furthermore, evidence is lacking as to whether megestrol acetate–induced increases in appetite, oral intake, weight, and serum albumin level bestow any survival benefit or affect outcomes in dialysis patients.4 However, the increased sense of well-being a patient experiences when appetite returns and weight is restored may be worth the effort.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

Q) Some of my CKD patients are malnourished; in fact, some of those on dialysis do not eat well and have low albumin levels. Previously in this column, it was stated that higher albumin levels (> 4 g/dL) confer survival benefits to dialysis patients. Should I consider prescribing megestrol acetate to improve appetite? If I do prescribe it, what dose is safe for CKD and dialysis patients?

Malnutrition affects one-third of dialysis patients,1 and malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) is common in those with stage 5 CKD. Albumin is used as an indicator of MICS in dialysis patients; however, since other factors (stress, infection, inflammation, comorbidities) affect nutritional status,2 serum albumin alone may not be sufficient to assess it.

In fact, a recent consensus statement on malnutrition from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition excluded serum albumin as a diagnostic characteristic; the criteria included percentage of energy requirement, percentage of weight loss and time frame, loss of body fat and muscle mass, presence of edema, and reduced grip strength.3 These may be better measures of malnutrition in dialysis patients and could be used as criteria for determining when to prescribe an appetite stimulant, such as megestrol acetate.

In recent years, megestrol acetate (an antineoplastic drug) has been used to improve appetite, weight, albumin levels, and MICS in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.1,4-6 Rammohan et al found significant increases in weight, BMI, body fat, triceps skinfold thickness, protein/energy intake, and serum albumin in 10 dialysis patients who took megestrol acetate (400 mg/d) for 16 weeks.4

Continue for megestrol acetate's effects >>

In a 20-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Yeh et al found significant increases in weight, body fat, and fat-free mass in elderly hemodialysis patients receiving megestrol acetate (800 mg/d). The treatment group also demonstrated greater improvement in ability to exercise.5

Monfared and colleagues looked specifically at megestrol acetate’s effect on serum albumin levels in dialysis patients.1 Using a much lower dose (40 mg bid for two months), they found a significant increase in serum albumin in the treatment group. Although an increase in appetite was noted, the researchers did not observe any significant change in total weight following treatment.1

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of Renal Nutrition, Golebiewska et al reported their use of megestrol acetate in maintenance hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients.6 Hypoalbuminemic patients were given megestrol acetate (160 mg/d). Significant increases in weight, BMI, subjective global assessment scores (a measure of nutritional status based on clinical indices such as weight, appetite, muscle, and fat mass), and serum albumin levels were seen. Only 12 of the 32 patients completed the study; the others dropped out due to adverse effects, including high intradialytic weight gain (the amount of fluid gained between dialysis sessions), dyspnea, diarrhea, and nausea.6

Currently, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the most effective dosage of megestrol acetate. Furthermore, evidence is lacking as to whether megestrol acetate–induced increases in appetite, oral intake, weight, and serum albumin level bestow any survival benefit or affect outcomes in dialysis patients.4 However, the increased sense of well-being a patient experiences when appetite returns and weight is restored may be worth the effort.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. Monfared A, Heidarzadeh A, Ghaffari M, Akbarpour M. Effect of megestrol acetate on serum albumin level in malnourished dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2009;19(2):167-171.

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A clinical guide to nutrition care in kidney disease. Acad Nutr Diet. 2013.

3. White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Malnutrition Work Group; ASPEN Malnutrition Task Force; ASPEN Board of Directors. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition) [erratum appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1899].

J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-738.

4. Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zedeh K, Liang A, Ghossein C. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15(3):345-355.

5. Yeh S, Marandi M, Thode H Jr, et al. Report of a pilot, double blind, placebo-controlled study of megestrol acetate in elderly dialysis patients with cachexia. J Ren Nutr. 2010; 20(1):52-62.

6. Golebiewska JE, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Aleksandrowicz-Wrona E, et al. Megestrol acetate use in hypoalbuminemic dialysis patients [comment]. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(2): 200-202.

7. Bendik I, Friedel A, Roos FF, et al. Vitamin D: a critical and necessary micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248.

8. Cabone F, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Potential pathophysiological role for the vitamin D deficiency in essential hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(5):260-276.

9. Sypniewska G, Pollak J, Strozecki P, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D, biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and subclinical organ damage in adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):114-121.

10. Vimaleswaran KS, Cavadino A, Berry DJ, et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):719-729.

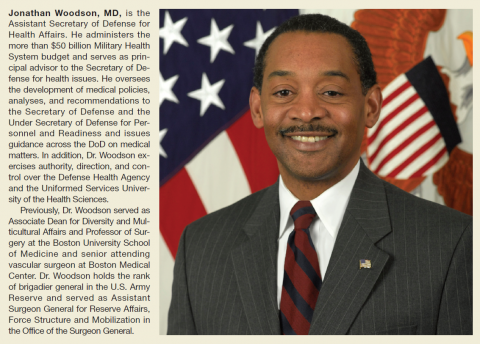

Committed to Showing Results at the VA

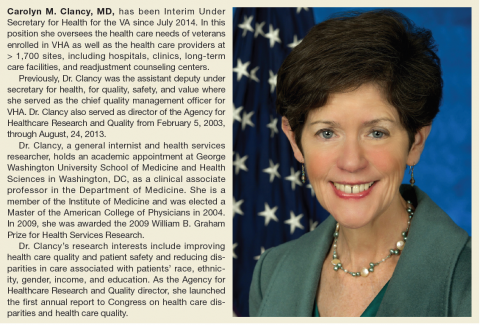

Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, was named Interim Under Secretary for Health for the VA on July 2, 2014, just as the wait time crisis seemed to be spinning out of control. Her appointment and the confirmation of Secretary Robert A. McDonald less than a month later proved essential to calming the furor but were admittedly just the first steps in a long-term process to increase veterans’ access to care and develop better systems and procedures across the agency.

Six months after her appointment, Federal Practitioner talked with Dr. Clancy about the pace of change and the role of health care providers in improving care for veterans. In the interview, Dr. Clancy clearly noted that many VA facilities already represent the best of U.S. health care and that the path forward requires sharing of best practices. Many other facilities, of course, will have to change, but Dr. Clancy insisted it is “an incredible opportunity” for the VA to learn as a system. Perhaps most heartening to VA practitioners, Dr. Clancy also recognized that “you can’t provide veteran-centered care without employees who are inspired to do their very, very best.”

To be sure, any successful change in VA procedures and culture will require buy-in not only from across the agency, but also from veterans and Congress. Dr. Clancy has already received 2 votes of confidence: The Paralyzed Veterans of America and the Vietnam Veterans of America jointly called on President Obama to make Dr. Clancy’s appointment permanent. The White House and congressional leaders, however, have yet to schedule hearings or comment publicly.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the interview. To hear the complete interview, including an in-depth discussion of the Blueprint for Excellence, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

Taking Measure of VA Strengths

Interim Under Secretary for Health Carolyn M. Clancy, MD. I came to this system in August of 2013 after more than 20 years at HHS, all working for an agency that had the lead charge for funding research to improve quality and safety in health care; and I had spent the last 10 years prior to coming here as the director of that agency. I came to VHA because I thought this system was unique among all systems, public and private, in this country and had the strongest foundation in place to deliver 21st century health care. And at least as important—probably more so—was the sense of mission among all of the employees I met. These were people I’ve known in academia, people I met on the interviews, people I’ve intersected with for a number of years in the research community. You can’t replicate it, and you can’t buy it; and I figured the combination of a strong foundation and mission meant that this was one of the best systems to work for.

I still think that. Some of our best facilities could compete head to head with any facilities in the private sector. There is no question about that. We have some systems, facilities, and clinics that are struggling as well, which is also very typical of the private sector.

What we have is an incredible opportunity, first, because we have a fabulous mission. We have highly committed and dedicated employees. We have an incredible opportunity to actually learn as a system. There has been a lot of discussion at a number of levels about how health care in the new century needs to be a learning health care system. We actually have the capability of delivering on that promise. So I’m very, very excited.

VA Clinical Staff and Recruitment

Dr. Clancy. I have often observed that change can be scary, but it’s also incredibly liberating. Some of our most dedicated employees, I know, can be frustrated, because they feel like they’re doing their part; but they aren’t always sure that the members of the team are as dedicated as they are or are going to catch the ball. And there’s no question that you don’t get to high-quality care without a good team. In other words, superb health care and exceptional veteran experience is a team sport by definition.

So I think it will actually help the vast majority of our frontline clinicians. It’ll be much, much easier for them to deliver the kind of care they want to deliver every single day but sometimes feel like they get stuck in workarounds.

As you have probably read and have heard me say, one of the biggest challenges of our crisis—now quite open to everyone—is how we had limited availability and limited capacity to meet the needs of the veterans we had the privilege of serving. So we are on a very, very big recruitment drive for all kinds of clinicians. And in addition to the incredible mission, we have taken some steps to make salaries a bit more competitive with the private sector. I want to underline a bit. You wouldn’t be coming to VA because you wanted to become wealthy, but we recognize that people have to pay student loans and so forth. And speaking of student loans, we have a variety of programs to help people pay down their educational debt.

And all of these things actually help, but the opportunity to deliver care that is really focused squarely on the needs of the individual veteran. That, I think, is what people will ultimately find far more exciting than any anxiety about change. …

The answer to the question about who are we recruiting is: yes. We’re recruiting all of those people [physicians and midlevel providers]. We often speak about the health care market in this country as if there were one health care market. And actually, U.S. health care, of which VA is very much a part, particularly now with the new law, is very much a series of local and regional markets. So to some extent, the ratios and the types of people that we’re going to need will depend on the specific community; but we’re looking for people in all of those areas.

Changing VA Culture

Dr. Clancy. There are a number of things that impact culture. Some of it is about stories. And I have to say that every day I get to be inspired by real-life stories of veterans and... their caregivers. Some of those caregivers are their family members or close friends: people who love them. And many of them are people who work for us in the Veterans Health Administration, people who just go the extra mile because it’s the right thing to do. Nobody said they had to do it. We don’t have a policy or a directive for it. To them, it’s as natural as gravity. …

Secretary McDonald often uses this diagram, an inverted pyramid that I love, where he starts off by having a regular pyramid; and he said, “This is how we think of a lot of organizations with the Secretary sitting right up here at the pinnacle, and veterans and everybody else are kind of down on the lowest tier.” And he said, “It’s exactly wrong. How I think about it is—” So, he flips it. We have people who provide direct care to veterans. We have people who help those people, and then we have people who help the people who are helping the people provide the care to veterans. And so that means that customer service is everybody’s job. It means that helping people on the front lines who are our colleagues—and we’re all in this together—make sure that they can deliver the care that veterans need. That is everybody’s job.

And I actually think it’s going to be a very, very easy sell. Reinforcing all of this is being transparent about data and how we’re doing. So we’re now starting to look internally at how our facilities compare with local counterparts in their particular community, and I think you will be seeing that become more public in the near future. We just have to make it a little more visually compelling.

This is how we learn. It isn’t to say, “Gee, look, you didn’t do as well as other facilities.” It’s to say, “Huh, you know, this facility actually has improved dramatically. Why don’t we go learn what they did?” which I think is consistent with [Federal Practitioner’s] focus on best practices. This is the big, big challenge and the opportunity for health care in general.

Blueprint for Excellence

In the wake of the wait time crisis, Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, has been tasked with implementing the Blueprint for Excellence. Its intent, according to the VA, is to “frame a set of activities that simultaneously address improving the performance of VHA health care now, developing a positive service culture, transitioning from ‘sick care’ to ‘health care’ in the broadest sense, and developing agile business systems and management processes that are efficient, transparent and accountable.”

All the changes at the VA will align with 10 strategies for sustained excellence, which focus on improving performance, promoting a positive culture of service, advancing health care innovation, and increasing operational effectiveness and accountability. The strategies include:

- Operate a health care network that anticipates and meets the unique needs of enrolled veterans, in general, and the service-disabled and most vulnerable veterans, in particular.

- Deliver high-quality, veteran-centered care that compares favorably to the best of the private sector in measured outcomes, value, efficiency, and patient experience.

- Leverage information technologies, analytics, and models of health care delivery to optimize individual and population health outcomes.

- Grow an organizational culture, rooted in VA’s core values and mission, that prioritizes the veteran first; engaging and inspiring employees to their highest possible level of performance and conduct.

- Foster an environment of continuous learning, responsible risk taking, and personal accountability.

- Advance health care that is personalized, proactive, and patient-driven and engages and inspires veterans to their highest possible level of health and well-being.

- Lead the nation in research and treatment of military service-related conditions.

- Become a model integrated health services network through innovative academic, intergovernmental, and community relationships, information exchange, and public-private partnerships.

- Operate and communicate with integrity, transparency, and accountability that earns and maintains the trust of veterans, stewards of the system (Congress, Veterans Service Organizations), and the public.

- Modernize management processes in human resources, procurement, payment, capital infrastructure, and information technology to operate with benchmark agility and efficiency.

To listen to Dr. Clancy’s in-depth discussion of the Blueprint for Excellence, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library/article/carolyn-clancy-on-implementing-the-blueprint-for-excellence-at-the-va/f7313e00ff18fcbcf4fcaead862c285a/ocregister.html.

Measuring Success or Failure

Dr. Clancy. We will be measuring this in a lot of different ways. First is that VA is, I believe, unique among federal departments in having a very deep all-employee survey. We also participate in the broad Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. ... In addition to that, we field our own survey internally and take that very, very seriously.

So literally, as the electrons are rolling in, we have a National Center for Organization and Development, which is sharing their results with me and looking at [the data] across the entire system by network, by facility. How are we doing? Where are there challenges? Where are there opportunities? Who’s doing incredibly well that we might learn something about how they’re doing that in order to help those facilities that are having more challenges? That is a very, very current source of information.

And the reason it’s so important is you can’t provide veteran-centered care without employees who are inspired to do their very, very best. And people who are inspired to do their very best, by definition, are not terribly unhappy. So that’s a very, very important source.

And I’ll also say that in health care, in general, as well as here, we’re seeing very important correlations between responses to employee surveys and such indicators as avoidable patient harms, rates of hospital-associated infections or health care-associated infections, and so forth. So we know that the two are very highly correlated.

The other reason that the survey is incredibly important is that most service industries have known for a long time that the best source of innovation are the people who are providing the service and care every single day. So again, that gets back to people feeling motivated and empowered and inspired. …

Time Frame for Change

Dr. Clancy. I think that people are seeing changes already. Now I’m just judging from my own e-mails and other things that we get; and we touch base regularly with veterans service organizations, with many, many stakeholders and take that input very, very seriously, because they are incredible partners in helping us identify and solve problems, because what I really worry about are veterans who are encountering difficulties, who may be fearful or hesitant in some fashion to bring that to our attention.

So I think, in a qualitative sense, we are seeing some positive signals but also recognizing that the scale of changes we’re talking about will take some time. But we will continue to see qualitative differences and, I think, real, tangible differences in the care that veterans get as the months proceed from here. I remain very optimistic about the future of this system and the size of the opportunity that we have.

Our laserlike focus for this coming year is access and exceptional veteran experience. You know, navigating health care can be pretty challenging. I know this because I’m from a very, very large extended family; and nobody else is in health or medicine, so I get regular reports. And whether you’re enrolled in our system or get your care elsewhere, it is not always easy.

But we have the incredible privilege of serving people who essentially wrote a blank check on our behalf when they agreed to serve the country. And so access is not something that, for the most part, is monitored closely in the private sector. It is certainly not publicly reported. We are making a very, very strong commitment, not just to improving, but to being able to show people the results.

Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, was named Interim Under Secretary for Health for the VA on July 2, 2014, just as the wait time crisis seemed to be spinning out of control. Her appointment and the confirmation of Secretary Robert A. McDonald less than a month later proved essential to calming the furor but were admittedly just the first steps in a long-term process to increase veterans’ access to care and develop better systems and procedures across the agency.

Six months after her appointment, Federal Practitioner talked with Dr. Clancy about the pace of change and the role of health care providers in improving care for veterans. In the interview, Dr. Clancy clearly noted that many VA facilities already represent the best of U.S. health care and that the path forward requires sharing of best practices. Many other facilities, of course, will have to change, but Dr. Clancy insisted it is “an incredible opportunity” for the VA to learn as a system. Perhaps most heartening to VA practitioners, Dr. Clancy also recognized that “you can’t provide veteran-centered care without employees who are inspired to do their very, very best.”

To be sure, any successful change in VA procedures and culture will require buy-in not only from across the agency, but also from veterans and Congress. Dr. Clancy has already received 2 votes of confidence: The Paralyzed Veterans of America and the Vietnam Veterans of America jointly called on President Obama to make Dr. Clancy’s appointment permanent. The White House and congressional leaders, however, have yet to schedule hearings or comment publicly.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the interview. To hear the complete interview, including an in-depth discussion of the Blueprint for Excellence, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

Taking Measure of VA Strengths

Interim Under Secretary for Health Carolyn M. Clancy, MD. I came to this system in August of 2013 after more than 20 years at HHS, all working for an agency that had the lead charge for funding research to improve quality and safety in health care; and I had spent the last 10 years prior to coming here as the director of that agency. I came to VHA because I thought this system was unique among all systems, public and private, in this country and had the strongest foundation in place to deliver 21st century health care. And at least as important—probably more so—was the sense of mission among all of the employees I met. These were people I’ve known in academia, people I met on the interviews, people I’ve intersected with for a number of years in the research community. You can’t replicate it, and you can’t buy it; and I figured the combination of a strong foundation and mission meant that this was one of the best systems to work for.

I still think that. Some of our best facilities could compete head to head with any facilities in the private sector. There is no question about that. We have some systems, facilities, and clinics that are struggling as well, which is also very typical of the private sector.

What we have is an incredible opportunity, first, because we have a fabulous mission. We have highly committed and dedicated employees. We have an incredible opportunity to actually learn as a system. There has been a lot of discussion at a number of levels about how health care in the new century needs to be a learning health care system. We actually have the capability of delivering on that promise. So I’m very, very excited.

VA Clinical Staff and Recruitment

Dr. Clancy. I have often observed that change can be scary, but it’s also incredibly liberating. Some of our most dedicated employees, I know, can be frustrated, because they feel like they’re doing their part; but they aren’t always sure that the members of the team are as dedicated as they are or are going to catch the ball. And there’s no question that you don’t get to high-quality care without a good team. In other words, superb health care and exceptional veteran experience is a team sport by definition.

So I think it will actually help the vast majority of our frontline clinicians. It’ll be much, much easier for them to deliver the kind of care they want to deliver every single day but sometimes feel like they get stuck in workarounds.

As you have probably read and have heard me say, one of the biggest challenges of our crisis—now quite open to everyone—is how we had limited availability and limited capacity to meet the needs of the veterans we had the privilege of serving. So we are on a very, very big recruitment drive for all kinds of clinicians. And in addition to the incredible mission, we have taken some steps to make salaries a bit more competitive with the private sector. I want to underline a bit. You wouldn’t be coming to VA because you wanted to become wealthy, but we recognize that people have to pay student loans and so forth. And speaking of student loans, we have a variety of programs to help people pay down their educational debt.

And all of these things actually help, but the opportunity to deliver care that is really focused squarely on the needs of the individual veteran. That, I think, is what people will ultimately find far more exciting than any anxiety about change. …

The answer to the question about who are we recruiting is: yes. We’re recruiting all of those people [physicians and midlevel providers]. We often speak about the health care market in this country as if there were one health care market. And actually, U.S. health care, of which VA is very much a part, particularly now with the new law, is very much a series of local and regional markets. So to some extent, the ratios and the types of people that we’re going to need will depend on the specific community; but we’re looking for people in all of those areas.

Changing VA Culture

Dr. Clancy. There are a number of things that impact culture. Some of it is about stories. And I have to say that every day I get to be inspired by real-life stories of veterans and... their caregivers. Some of those caregivers are their family members or close friends: people who love them. And many of them are people who work for us in the Veterans Health Administration, people who just go the extra mile because it’s the right thing to do. Nobody said they had to do it. We don’t have a policy or a directive for it. To them, it’s as natural as gravity. …

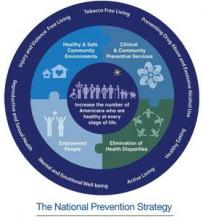

Secretary McDonald often uses this diagram, an inverted pyramid that I love, where he starts off by having a regular pyramid; and he said, “This is how we think of a lot of organizations with the Secretary sitting right up here at the pinnacle, and veterans and everybody else are kind of down on the lowest tier.” And he said, “It’s exactly wrong. How I think about it is—” So, he flips it. We have people who provide direct care to veterans. We have people who help those people, and then we have people who help the people who are helping the people provide the care to veterans. And so that means that customer service is everybody’s job. It means that helping people on the front lines who are our colleagues—and we’re all in this together—make sure that they can deliver the care that veterans need. That is everybody’s job.

And I actually think it’s going to be a very, very easy sell. Reinforcing all of this is being transparent about data and how we’re doing. So we’re now starting to look internally at how our facilities compare with local counterparts in their particular community, and I think you will be seeing that become more public in the near future. We just have to make it a little more visually compelling.

This is how we learn. It isn’t to say, “Gee, look, you didn’t do as well as other facilities.” It’s to say, “Huh, you know, this facility actually has improved dramatically. Why don’t we go learn what they did?” which I think is consistent with [Federal Practitioner’s] focus on best practices. This is the big, big challenge and the opportunity for health care in general.

Blueprint for Excellence

In the wake of the wait time crisis, Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, has been tasked with implementing the Blueprint for Excellence. Its intent, according to the VA, is to “frame a set of activities that simultaneously address improving the performance of VHA health care now, developing a positive service culture, transitioning from ‘sick care’ to ‘health care’ in the broadest sense, and developing agile business systems and management processes that are efficient, transparent and accountable.”

All the changes at the VA will align with 10 strategies for sustained excellence, which focus on improving performance, promoting a positive culture of service, advancing health care innovation, and increasing operational effectiveness and accountability. The strategies include:

- Operate a health care network that anticipates and meets the unique needs of enrolled veterans, in general, and the service-disabled and most vulnerable veterans, in particular.

- Deliver high-quality, veteran-centered care that compares favorably to the best of the private sector in measured outcomes, value, efficiency, and patient experience.

- Leverage information technologies, analytics, and models of health care delivery to optimize individual and population health outcomes.

- Grow an organizational culture, rooted in VA’s core values and mission, that prioritizes the veteran first; engaging and inspiring employees to their highest possible level of performance and conduct.

- Foster an environment of continuous learning, responsible risk taking, and personal accountability.

- Advance health care that is personalized, proactive, and patient-driven and engages and inspires veterans to their highest possible level of health and well-being.

- Lead the nation in research and treatment of military service-related conditions.

- Become a model integrated health services network through innovative academic, intergovernmental, and community relationships, information exchange, and public-private partnerships.

- Operate and communicate with integrity, transparency, and accountability that earns and maintains the trust of veterans, stewards of the system (Congress, Veterans Service Organizations), and the public.

- Modernize management processes in human resources, procurement, payment, capital infrastructure, and information technology to operate with benchmark agility and efficiency.

To listen to Dr. Clancy’s in-depth discussion of the Blueprint for Excellence, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library/article/carolyn-clancy-on-implementing-the-blueprint-for-excellence-at-the-va/f7313e00ff18fcbcf4fcaead862c285a/ocregister.html.

Measuring Success or Failure

Dr. Clancy. We will be measuring this in a lot of different ways. First is that VA is, I believe, unique among federal departments in having a very deep all-employee survey. We also participate in the broad Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. ... In addition to that, we field our own survey internally and take that very, very seriously.

So literally, as the electrons are rolling in, we have a National Center for Organization and Development, which is sharing their results with me and looking at [the data] across the entire system by network, by facility. How are we doing? Where are there challenges? Where are there opportunities? Who’s doing incredibly well that we might learn something about how they’re doing that in order to help those facilities that are having more challenges? That is a very, very current source of information.

And the reason it’s so important is you can’t provide veteran-centered care without employees who are inspired to do their very, very best. And people who are inspired to do their very best, by definition, are not terribly unhappy. So that’s a very, very important source.

And I’ll also say that in health care, in general, as well as here, we’re seeing very important correlations between responses to employee surveys and such indicators as avoidable patient harms, rates of hospital-associated infections or health care-associated infections, and so forth. So we know that the two are very highly correlated.

The other reason that the survey is incredibly important is that most service industries have known for a long time that the best source of innovation are the people who are providing the service and care every single day. So again, that gets back to people feeling motivated and empowered and inspired. …

Time Frame for Change

Dr. Clancy. I think that people are seeing changes already. Now I’m just judging from my own e-mails and other things that we get; and we touch base regularly with veterans service organizations, with many, many stakeholders and take that input very, very seriously, because they are incredible partners in helping us identify and solve problems, because what I really worry about are veterans who are encountering difficulties, who may be fearful or hesitant in some fashion to bring that to our attention.

So I think, in a qualitative sense, we are seeing some positive signals but also recognizing that the scale of changes we’re talking about will take some time. But we will continue to see qualitative differences and, I think, real, tangible differences in the care that veterans get as the months proceed from here. I remain very optimistic about the future of this system and the size of the opportunity that we have.

Our laserlike focus for this coming year is access and exceptional veteran experience. You know, navigating health care can be pretty challenging. I know this because I’m from a very, very large extended family; and nobody else is in health or medicine, so I get regular reports. And whether you’re enrolled in our system or get your care elsewhere, it is not always easy.

But we have the incredible privilege of serving people who essentially wrote a blank check on our behalf when they agreed to serve the country. And so access is not something that, for the most part, is monitored closely in the private sector. It is certainly not publicly reported. We are making a very, very strong commitment, not just to improving, but to being able to show people the results.

Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, was named Interim Under Secretary for Health for the VA on July 2, 2014, just as the wait time crisis seemed to be spinning out of control. Her appointment and the confirmation of Secretary Robert A. McDonald less than a month later proved essential to calming the furor but were admittedly just the first steps in a long-term process to increase veterans’ access to care and develop better systems and procedures across the agency.

Six months after her appointment, Federal Practitioner talked with Dr. Clancy about the pace of change and the role of health care providers in improving care for veterans. In the interview, Dr. Clancy clearly noted that many VA facilities already represent the best of U.S. health care and that the path forward requires sharing of best practices. Many other facilities, of course, will have to change, but Dr. Clancy insisted it is “an incredible opportunity” for the VA to learn as a system. Perhaps most heartening to VA practitioners, Dr. Clancy also recognized that “you can’t provide veteran-centered care without employees who are inspired to do their very, very best.”

To be sure, any successful change in VA procedures and culture will require buy-in not only from across the agency, but also from veterans and Congress. Dr. Clancy has already received 2 votes of confidence: The Paralyzed Veterans of America and the Vietnam Veterans of America jointly called on President Obama to make Dr. Clancy’s appointment permanent. The White House and congressional leaders, however, have yet to schedule hearings or comment publicly.

Below is an edited and condensed version of the interview. To hear the complete interview, including an in-depth discussion of the Blueprint for Excellence, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library.html.

Taking Measure of VA Strengths

Interim Under Secretary for Health Carolyn M. Clancy, MD. I came to this system in August of 2013 after more than 20 years at HHS, all working for an agency that had the lead charge for funding research to improve quality and safety in health care; and I had spent the last 10 years prior to coming here as the director of that agency. I came to VHA because I thought this system was unique among all systems, public and private, in this country and had the strongest foundation in place to deliver 21st century health care. And at least as important—probably more so—was the sense of mission among all of the employees I met. These were people I’ve known in academia, people I met on the interviews, people I’ve intersected with for a number of years in the research community. You can’t replicate it, and you can’t buy it; and I figured the combination of a strong foundation and mission meant that this was one of the best systems to work for.

I still think that. Some of our best facilities could compete head to head with any facilities in the private sector. There is no question about that. We have some systems, facilities, and clinics that are struggling as well, which is also very typical of the private sector.

What we have is an incredible opportunity, first, because we have a fabulous mission. We have highly committed and dedicated employees. We have an incredible opportunity to actually learn as a system. There has been a lot of discussion at a number of levels about how health care in the new century needs to be a learning health care system. We actually have the capability of delivering on that promise. So I’m very, very excited.

VA Clinical Staff and Recruitment

Dr. Clancy. I have often observed that change can be scary, but it’s also incredibly liberating. Some of our most dedicated employees, I know, can be frustrated, because they feel like they’re doing their part; but they aren’t always sure that the members of the team are as dedicated as they are or are going to catch the ball. And there’s no question that you don’t get to high-quality care without a good team. In other words, superb health care and exceptional veteran experience is a team sport by definition.

So I think it will actually help the vast majority of our frontline clinicians. It’ll be much, much easier for them to deliver the kind of care they want to deliver every single day but sometimes feel like they get stuck in workarounds.

As you have probably read and have heard me say, one of the biggest challenges of our crisis—now quite open to everyone—is how we had limited availability and limited capacity to meet the needs of the veterans we had the privilege of serving. So we are on a very, very big recruitment drive for all kinds of clinicians. And in addition to the incredible mission, we have taken some steps to make salaries a bit more competitive with the private sector. I want to underline a bit. You wouldn’t be coming to VA because you wanted to become wealthy, but we recognize that people have to pay student loans and so forth. And speaking of student loans, we have a variety of programs to help people pay down their educational debt.

And all of these things actually help, but the opportunity to deliver care that is really focused squarely on the needs of the individual veteran. That, I think, is what people will ultimately find far more exciting than any anxiety about change. …

The answer to the question about who are we recruiting is: yes. We’re recruiting all of those people [physicians and midlevel providers]. We often speak about the health care market in this country as if there were one health care market. And actually, U.S. health care, of which VA is very much a part, particularly now with the new law, is very much a series of local and regional markets. So to some extent, the ratios and the types of people that we’re going to need will depend on the specific community; but we’re looking for people in all of those areas.

Changing VA Culture

Dr. Clancy. There are a number of things that impact culture. Some of it is about stories. And I have to say that every day I get to be inspired by real-life stories of veterans and... their caregivers. Some of those caregivers are their family members or close friends: people who love them. And many of them are people who work for us in the Veterans Health Administration, people who just go the extra mile because it’s the right thing to do. Nobody said they had to do it. We don’t have a policy or a directive for it. To them, it’s as natural as gravity. …

Secretary McDonald often uses this diagram, an inverted pyramid that I love, where he starts off by having a regular pyramid; and he said, “This is how we think of a lot of organizations with the Secretary sitting right up here at the pinnacle, and veterans and everybody else are kind of down on the lowest tier.” And he said, “It’s exactly wrong. How I think about it is—” So, he flips it. We have people who provide direct care to veterans. We have people who help those people, and then we have people who help the people who are helping the people provide the care to veterans. And so that means that customer service is everybody’s job. It means that helping people on the front lines who are our colleagues—and we’re all in this together—make sure that they can deliver the care that veterans need. That is everybody’s job.

And I actually think it’s going to be a very, very easy sell. Reinforcing all of this is being transparent about data and how we’re doing. So we’re now starting to look internally at how our facilities compare with local counterparts in their particular community, and I think you will be seeing that become more public in the near future. We just have to make it a little more visually compelling.

This is how we learn. It isn’t to say, “Gee, look, you didn’t do as well as other facilities.” It’s to say, “Huh, you know, this facility actually has improved dramatically. Why don’t we go learn what they did?” which I think is consistent with [Federal Practitioner’s] focus on best practices. This is the big, big challenge and the opportunity for health care in general.

Blueprint for Excellence

In the wake of the wait time crisis, Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, has been tasked with implementing the Blueprint for Excellence. Its intent, according to the VA, is to “frame a set of activities that simultaneously address improving the performance of VHA health care now, developing a positive service culture, transitioning from ‘sick care’ to ‘health care’ in the broadest sense, and developing agile business systems and management processes that are efficient, transparent and accountable.”

All the changes at the VA will align with 10 strategies for sustained excellence, which focus on improving performance, promoting a positive culture of service, advancing health care innovation, and increasing operational effectiveness and accountability. The strategies include:

- Operate a health care network that anticipates and meets the unique needs of enrolled veterans, in general, and the service-disabled and most vulnerable veterans, in particular.

- Deliver high-quality, veteran-centered care that compares favorably to the best of the private sector in measured outcomes, value, efficiency, and patient experience.

- Leverage information technologies, analytics, and models of health care delivery to optimize individual and population health outcomes.

- Grow an organizational culture, rooted in VA’s core values and mission, that prioritizes the veteran first; engaging and inspiring employees to their highest possible level of performance and conduct.

- Foster an environment of continuous learning, responsible risk taking, and personal accountability.

- Advance health care that is personalized, proactive, and patient-driven and engages and inspires veterans to their highest possible level of health and well-being.

- Lead the nation in research and treatment of military service-related conditions.

- Become a model integrated health services network through innovative academic, intergovernmental, and community relationships, information exchange, and public-private partnerships.

- Operate and communicate with integrity, transparency, and accountability that earns and maintains the trust of veterans, stewards of the system (Congress, Veterans Service Organizations), and the public.

- Modernize management processes in human resources, procurement, payment, capital infrastructure, and information technology to operate with benchmark agility and efficiency.

To listen to Dr. Clancy’s in-depth discussion of the Blueprint for Excellence, visit http://www.fedprac.com/multimedia/multimedia-library/article/carolyn-clancy-on-implementing-the-blueprint-for-excellence-at-the-va/f7313e00ff18fcbcf4fcaead862c285a/ocregister.html.

Measuring Success or Failure

Dr. Clancy. We will be measuring this in a lot of different ways. First is that VA is, I believe, unique among federal departments in having a very deep all-employee survey. We also participate in the broad Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. ... In addition to that, we field our own survey internally and take that very, very seriously.

So literally, as the electrons are rolling in, we have a National Center for Organization and Development, which is sharing their results with me and looking at [the data] across the entire system by network, by facility. How are we doing? Where are there challenges? Where are there opportunities? Who’s doing incredibly well that we might learn something about how they’re doing that in order to help those facilities that are having more challenges? That is a very, very current source of information.

And the reason it’s so important is you can’t provide veteran-centered care without employees who are inspired to do their very, very best. And people who are inspired to do their very best, by definition, are not terribly unhappy. So that’s a very, very important source.

And I’ll also say that in health care, in general, as well as here, we’re seeing very important correlations between responses to employee surveys and such indicators as avoidable patient harms, rates of hospital-associated infections or health care-associated infections, and so forth. So we know that the two are very highly correlated.

The other reason that the survey is incredibly important is that most service industries have known for a long time that the best source of innovation are the people who are providing the service and care every single day. So again, that gets back to people feeling motivated and empowered and inspired. …

Time Frame for Change

Dr. Clancy. I think that people are seeing changes already. Now I’m just judging from my own e-mails and other things that we get; and we touch base regularly with veterans service organizations, with many, many stakeholders and take that input very, very seriously, because they are incredible partners in helping us identify and solve problems, because what I really worry about are veterans who are encountering difficulties, who may be fearful or hesitant in some fashion to bring that to our attention.

So I think, in a qualitative sense, we are seeing some positive signals but also recognizing that the scale of changes we’re talking about will take some time. But we will continue to see qualitative differences and, I think, real, tangible differences in the care that veterans get as the months proceed from here. I remain very optimistic about the future of this system and the size of the opportunity that we have.

Our laserlike focus for this coming year is access and exceptional veteran experience. You know, navigating health care can be pretty challenging. I know this because I’m from a very, very large extended family; and nobody else is in health or medicine, so I get regular reports. And whether you’re enrolled in our system or get your care elsewhere, it is not always easy.

But we have the incredible privilege of serving people who essentially wrote a blank check on our behalf when they agreed to serve the country. And so access is not something that, for the most part, is monitored closely in the private sector. It is certainly not publicly reported. We are making a very, very strong commitment, not just to improving, but to being able to show people the results.

Pituitary Incidentaloma

Brian, 46, is referred to endocrinology for evaluation of a pituitary “mass.” The mass was an incidental finding of head and neck CT performed three months ago, when Brian went to an emergency department following a motor vehicle accident. He has fully recovered from the accident and feels well. He describes himself as a “completely healthy” person who has no chronic medical conditions and takes neither prescription nor OTC medications.

Brian denies significant headache, visual disturbance, change in appetite, unexplained weight change, skin rash (wide purple striae) or color changes (hyperpigmentation), polyuria or polydipsia, dizziness, syncopal episodes, low libido, erectile dysfunction, joint pain, and changes in ring or shoe size. He does not wear a hat or cap and is unaware of head size changes. He has not experienced changes in his facial features or trouble with chewing.

He is a happily married engineer with two healthy children and reports that he feels well except for this “brain tumor” finding that has been a shock to him and his family. There is no family history of pituitary adenoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome.

His vital signs, all within normal ranges, include a blood pressure of 103/65 mm Hg. His height is 6 ft and his weight, 180 lb. His BMI is 24.4.

HOW COMMON IS PITUITARY INCIDENTALOMA?

A pituitary incidentaloma is a lesion in the pituitary gland that was not previously suspected and was found through an imaging study ordered for other reasons. Pituitary incidentaloma is surprisingly common, with an average prevalence of 10.6% (as estimated from combined autopsy data), although it has been found in up to 20% of patients undergoing CT and 38% undergoing MRI.1,2 Most are microadenomas (< 1 cm in size).1

Continue for recommendations from the Endocrine Society >>

SHOULD AN ASYMPTOMATIC PATIENT BE EVALUATED FURTHER?

Endocrine Society guidelines2 recommend that all patients with pituitary incidentaloma, with or without symptoms, should undergo a complete history and physical examination and laboratory evaluation to exclude hypersecretion and hyposecretion of pituitary hormones.

The “classic” presentation of pituitary hormone hypersecretion—in the form of prolactinoma, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) excess (Cushing disease), growth hormone (GH) excess (gigantism/acromegaly), and TSH excess (secondary hyperthyroidism)—may be readily detectable on history and physical examination. Subtle cases, so-called subclinical disease, however, may exhibit little or no signs and symptoms initially but can be detrimental to the patient’s health if left untreated. For example, the estimated time from onset to diagnosis of acromegaly is approximately seven to 10 years—a delay that can significantly impact the patient’s morbidity and mortality.3

Prolactinoma can be more clinically apparent in premenopausal females due to irregular menstrual cycles (oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea). However, galactorrhea, or “milky” nipple discharge, occurs in only about 50% of women with prolactinoma and is extremely rare in men. Furthermore, the clinical presentation of prolactinoma in men is vague and related to hypogonadism, resulting from increased prolactin levels. Since men are essentially asymptomatic, these tumors can grow extensively (macroadenoma) and cause “mass effect,” such as headaches and visual impairment.

Therefore, without laboratory testing, abnormal pituitary function may go unrecognized.

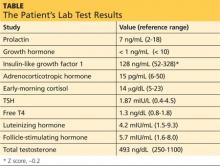

WHAT LABS SHOULD I ORDER FOR THIS PATIENT?

Guidelines suggest an initial screening panel of prolactin, GH, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), ACTH, early-morning cortisol, TSH, free T4, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and testosterone.2

Note the use of “suggest” rather than “recommend.” Even among guideline task force members, there were differences in opinion as to whether certain tests (eg, TSH, LH, and FSH) should be included in initial screening. Those tests can be ordered at the clinician’s discretion, according to the level of suspicion, or can be added later if necessary.