User login

Tips, Tools to Control Diabetes, Hyperglycemia in Hospitalized Patients

Controlling diabetes in the hospital is one of the most predominant challenges hospitalists face. In addition to the condition’s increased prevalence among the general population, patients with diabetes are commonly admitted to the hospital multiple times. And the treatment of diabetes can make the treatment of other conditions more difficult.

In fact, a 2014 study conducted in California by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and the California Center for Public Health Advocacy revealed that one-third of hospitalized patients older than 34 in California have diabetes.

For hospitalists ready to tackle a condition like diabetes—increasingly common and challenging to treat—SHM now has more resources than ever. And hospitalists can start to take advantage of them today.

Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit

SHM’s Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit gives hospitalists the first advantages in treating hyperglycemia in the hospital. Using SHM’s proven approach to quality improvement, including personal experience and evidence-based medicine, the toolkit enables hospitalists to implement effective regimens and protocols that optimize glycemic control and minimize hypoglycemia.

The toolkit (www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi) is easy to use and includes step-by-step instructions, from first steps to performance tracking to continuing improvement.

Hospital Medicine 2015

Ready to learn directly from the experts in inpatient glycemic control and share experiences with thousands of other hospitalists? HM15 will feature the most current information and research from the leading authorities on glycemic control.

For more information and to register online, visit www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation

SHM’s signature mentored implementation model helps hospitals create and implement programs that make a difference. The Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation (GCMI) Program links hospitals with national leaders in the field for a mentored relationship, critical data benchmarking, and collaboration with peers.

GCMI has now moved to a rolling acceptance model, so hospitals can now apply any time to start preventing hypoglycemia and better managing their inpatients with hyperglycemia and diabetes. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Controlling diabetes in the hospital is one of the most predominant challenges hospitalists face. In addition to the condition’s increased prevalence among the general population, patients with diabetes are commonly admitted to the hospital multiple times. And the treatment of diabetes can make the treatment of other conditions more difficult.

In fact, a 2014 study conducted in California by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and the California Center for Public Health Advocacy revealed that one-third of hospitalized patients older than 34 in California have diabetes.

For hospitalists ready to tackle a condition like diabetes—increasingly common and challenging to treat—SHM now has more resources than ever. And hospitalists can start to take advantage of them today.

Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit

SHM’s Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit gives hospitalists the first advantages in treating hyperglycemia in the hospital. Using SHM’s proven approach to quality improvement, including personal experience and evidence-based medicine, the toolkit enables hospitalists to implement effective regimens and protocols that optimize glycemic control and minimize hypoglycemia.

The toolkit (www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi) is easy to use and includes step-by-step instructions, from first steps to performance tracking to continuing improvement.

Hospital Medicine 2015

Ready to learn directly from the experts in inpatient glycemic control and share experiences with thousands of other hospitalists? HM15 will feature the most current information and research from the leading authorities on glycemic control.

For more information and to register online, visit www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation

SHM’s signature mentored implementation model helps hospitals create and implement programs that make a difference. The Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation (GCMI) Program links hospitals with national leaders in the field for a mentored relationship, critical data benchmarking, and collaboration with peers.

GCMI has now moved to a rolling acceptance model, so hospitals can now apply any time to start preventing hypoglycemia and better managing their inpatients with hyperglycemia and diabetes. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Controlling diabetes in the hospital is one of the most predominant challenges hospitalists face. In addition to the condition’s increased prevalence among the general population, patients with diabetes are commonly admitted to the hospital multiple times. And the treatment of diabetes can make the treatment of other conditions more difficult.

In fact, a 2014 study conducted in California by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and the California Center for Public Health Advocacy revealed that one-third of hospitalized patients older than 34 in California have diabetes.

For hospitalists ready to tackle a condition like diabetes—increasingly common and challenging to treat—SHM now has more resources than ever. And hospitalists can start to take advantage of them today.

Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit

SHM’s Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit gives hospitalists the first advantages in treating hyperglycemia in the hospital. Using SHM’s proven approach to quality improvement, including personal experience and evidence-based medicine, the toolkit enables hospitalists to implement effective regimens and protocols that optimize glycemic control and minimize hypoglycemia.

The toolkit (www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi) is easy to use and includes step-by-step instructions, from first steps to performance tracking to continuing improvement.

Hospital Medicine 2015

Ready to learn directly from the experts in inpatient glycemic control and share experiences with thousands of other hospitalists? HM15 will feature the most current information and research from the leading authorities on glycemic control.

For more information and to register online, visit www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation

SHM’s signature mentored implementation model helps hospitals create and implement programs that make a difference. The Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation (GCMI) Program links hospitals with national leaders in the field for a mentored relationship, critical data benchmarking, and collaboration with peers.

GCMI has now moved to a rolling acceptance model, so hospitals can now apply any time to start preventing hypoglycemia and better managing their inpatients with hyperglycemia and diabetes. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

10 Things Obstetricians Want Hospitalists to Know

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

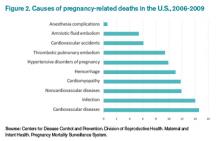

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Adding Basal Insulin to Oral Agents in Type 2 Diabetes Might Offer Best Glycemic Control

Clinical question: When added to oral diabetic agents, which insulin regimen (biphasic, prandial or basal) best achieves glycemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes?

Background: Most patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) require insulin when oral agents provide suboptimal glycemic control. Little is known about which insulin regimen is most effective.

Study design: Three-year, open-label, multicenter trial.

Setting: Fifty-eight clinical centers in the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Synopsis: The authors randomized 708 insulin-naïve DM2 patients (median age 62 years) with HgbA1c 7% to 10% on maximum-dose metformin or sulfonylurea to one of three regimens: biphasic insulin twice daily; prandial insulin three times daily; or basal insulin once daily. Outcomes were HgbA1c, hypoglycemia rates, and weight gain. Sulfonylureas were replaced by another insulin if glycemic control was unacceptable.

The patients were mostly Caucasian and overweight. At three years of followup, median HgbA1c was similar in all groups (7.1% biphasic, 6.8% prandial, 6.9% basal); however, more patients who received prandial or basal insulin achieved HgbA1c less than 6.5% (45% and 43%, respectively) than in the biphasic group (32%).

Hypoglycemia was significantly less frequent in the basal insulin group (1.7 per patient per year versus 3.0 and 5.5 with biphasic and prandial, respectively). Patients gained weight in all groups; the greatest gain was with prandial insulin. At three years, there were no significant between-group differences in blood pressure, cholesterol, albuminuria, or quality of life.

Bottom line: Adding insulin to oral diabetic regimens improves glycemic control. Basal or prandial insulin regimens achieve glycemic targets more frequently than biphasic dosing.

Citation: Holman RR, Farmer AJ, Davies MJ, et al. Three-year efficacy of complex insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(18):1736-1747.

Clinical question: When added to oral diabetic agents, which insulin regimen (biphasic, prandial or basal) best achieves glycemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes?

Background: Most patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) require insulin when oral agents provide suboptimal glycemic control. Little is known about which insulin regimen is most effective.

Study design: Three-year, open-label, multicenter trial.

Setting: Fifty-eight clinical centers in the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Synopsis: The authors randomized 708 insulin-naïve DM2 patients (median age 62 years) with HgbA1c 7% to 10% on maximum-dose metformin or sulfonylurea to one of three regimens: biphasic insulin twice daily; prandial insulin three times daily; or basal insulin once daily. Outcomes were HgbA1c, hypoglycemia rates, and weight gain. Sulfonylureas were replaced by another insulin if glycemic control was unacceptable.

The patients were mostly Caucasian and overweight. At three years of followup, median HgbA1c was similar in all groups (7.1% biphasic, 6.8% prandial, 6.9% basal); however, more patients who received prandial or basal insulin achieved HgbA1c less than 6.5% (45% and 43%, respectively) than in the biphasic group (32%).

Hypoglycemia was significantly less frequent in the basal insulin group (1.7 per patient per year versus 3.0 and 5.5 with biphasic and prandial, respectively). Patients gained weight in all groups; the greatest gain was with prandial insulin. At three years, there were no significant between-group differences in blood pressure, cholesterol, albuminuria, or quality of life.

Bottom line: Adding insulin to oral diabetic regimens improves glycemic control. Basal or prandial insulin regimens achieve glycemic targets more frequently than biphasic dosing.

Citation: Holman RR, Farmer AJ, Davies MJ, et al. Three-year efficacy of complex insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(18):1736-1747.

Clinical question: When added to oral diabetic agents, which insulin regimen (biphasic, prandial or basal) best achieves glycemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes?

Background: Most patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) require insulin when oral agents provide suboptimal glycemic control. Little is known about which insulin regimen is most effective.

Study design: Three-year, open-label, multicenter trial.

Setting: Fifty-eight clinical centers in the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Synopsis: The authors randomized 708 insulin-naïve DM2 patients (median age 62 years) with HgbA1c 7% to 10% on maximum-dose metformin or sulfonylurea to one of three regimens: biphasic insulin twice daily; prandial insulin three times daily; or basal insulin once daily. Outcomes were HgbA1c, hypoglycemia rates, and weight gain. Sulfonylureas were replaced by another insulin if glycemic control was unacceptable.

The patients were mostly Caucasian and overweight. At three years of followup, median HgbA1c was similar in all groups (7.1% biphasic, 6.8% prandial, 6.9% basal); however, more patients who received prandial or basal insulin achieved HgbA1c less than 6.5% (45% and 43%, respectively) than in the biphasic group (32%).

Hypoglycemia was significantly less frequent in the basal insulin group (1.7 per patient per year versus 3.0 and 5.5 with biphasic and prandial, respectively). Patients gained weight in all groups; the greatest gain was with prandial insulin. At three years, there were no significant between-group differences in blood pressure, cholesterol, albuminuria, or quality of life.

Bottom line: Adding insulin to oral diabetic regimens improves glycemic control. Basal or prandial insulin regimens achieve glycemic targets more frequently than biphasic dosing.

Citation: Holman RR, Farmer AJ, Davies MJ, et al. Three-year efficacy of complex insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(18):1736-1747.

Patient Participation in Medication Reconciliation at Discharge Helps Detect Prescribing Discrepancies

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Patient Signout Is Not Uniformly Comprehensive and Often Lacks Critical Information

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.

The median signout duration was 35 seconds (IQR 19-62) per patient. Key clinical information was present in just 62% of combined written or oral signouts. Most signouts included no questions from the recipient. Factors associated with higher rate of content inclusion included: familiarity with the patient, sense of responsibility (primary team vs. covering team), only one signout per day (as compared to sequential signout), presence of a senior resident, and comprehensive, written signouts.

Study limitations include the Hawthorne effect, as several participants mentioned that the presence of audiotape led to more comprehensive signouts than are typical. Also, the signout quality assessment in this study has not been validated with patient-safety outcomes.

Bottom line: Signouts among internal-medicine residents at this one hospital showed variability in terms of quantitative and qualitative information and often missed crucial information about patient care.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248-255.

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.

The median signout duration was 35 seconds (IQR 19-62) per patient. Key clinical information was present in just 62% of combined written or oral signouts. Most signouts included no questions from the recipient. Factors associated with higher rate of content inclusion included: familiarity with the patient, sense of responsibility (primary team vs. covering team), only one signout per day (as compared to sequential signout), presence of a senior resident, and comprehensive, written signouts.

Study limitations include the Hawthorne effect, as several participants mentioned that the presence of audiotape led to more comprehensive signouts than are typical. Also, the signout quality assessment in this study has not been validated with patient-safety outcomes.

Bottom line: Signouts among internal-medicine residents at this one hospital showed variability in terms of quantitative and qualitative information and often missed crucial information about patient care.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248-255.

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.

The median signout duration was 35 seconds (IQR 19-62) per patient. Key clinical information was present in just 62% of combined written or oral signouts. Most signouts included no questions from the recipient. Factors associated with higher rate of content inclusion included: familiarity with the patient, sense of responsibility (primary team vs. covering team), only one signout per day (as compared to sequential signout), presence of a senior resident, and comprehensive, written signouts.

Study limitations include the Hawthorne effect, as several participants mentioned that the presence of audiotape led to more comprehensive signouts than are typical. Also, the signout quality assessment in this study has not been validated with patient-safety outcomes.

Bottom line: Signouts among internal-medicine residents at this one hospital showed variability in terms of quantitative and qualitative information and often missed crucial information about patient care.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248-255.

Emergency Department Signout via Voicemail Yields Mixed Reviews

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Baystate Medical Center's Unit-Based, Multidisciplinary Rounding Enhances Inpatient Care

The hospitalist-led Broder Service empowers all care-team members to focus on patient quality, satisfaction. Get an up-close look at the service with our 6-minute feature video:

The hospitalist-led Broder Service empowers all care-team members to focus on patient quality, satisfaction. Get an up-close look at the service with our 6-minute feature video:

The hospitalist-led Broder Service empowers all care-team members to focus on patient quality, satisfaction. Get an up-close look at the service with our 6-minute feature video:

HealthKit Wellness App Could Prove Helpful to Hospitalists

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) released its Triple Aim Initiative in 2008, challenging the healthcare industry to undergo extensive systematic change, with the following goals:1

- Reduce the per capita cost of healthcare;

- Improve the patient experience of care, including quality and satisfaction; and

- Improve the health of populations.

The first two aims are difficult enough, but the third involves engaging and empowering patients and their families to take ownership of their own health and wellness. This is much more than just understanding what your diagnoses are and which medications to take; it is about getting and staying well. Keeping patients and their families well is a goal that has eluded the healthcare industry since before Hippocrates and is an extremely challenging one for hospitalists, whose time with patients is usually limited to an acute care hospital stay.

Naturally, when one industry cannot figure out how to do something well, another industry will develop a breakthrough innovation. Enter Apple Inc., which has officially moved into the health and wellness business. Apple Health is a new app that will share multiple inputs of patient information in a cloud platform called “HealthKit.” HealthKit will allow a user to view a personalized dashboard of health and fitness metrics, which conglomerates information from a myriad of different health and wellness apps, helping them “communicate” with one another.2

The breadth and choice of health and wellness apps available to users is astounding. In a five-minute browse through the app store on my iPhone, I found the following free options to help patients track and understand their health and wellness:

- MyPlate Calorie Tracker, Calorie Counter, and Fooducate help educate and monitor caloric intake.

- iTriage, WebMD, and Mango Health Medication Manager, which can answer questions about symptoms you may be experiencing, will save a list of medications, conditions, procedures, physicians, appointments, and more, and can help you manage your medications.

- Nexercise, MapMyRun, MapMyRide, MapMyFitness, Pacer, and Health Mate track physical activity.

- Fitness Buddy and Daily Workout allow users to view daily workout options and target muscle groups for appropriate exercises.

- ShopWell allows you to scan food labels and evaluate ingredients, calories, gluten, and so on in most store-bought food products.

What Apple proposes to do with its new HealthKit is coordinate the input of these types of apps to synthesize a patient’s health and wellness onto a single platform, which can be shared with caretakers and healthcare providers as needed. The company, as only Apple can, actually declared that its app might be “the beginning of a health revolution.”

A New Day

What HealthKit offers is truly unique from a data security standpoint, which will appeal to Orwellian paranoids. Traditionally, when customers use services such as Google or Yahoo, these services use your personal identity—gathered in pieces of data such as your location and your browsing histories—and then use that data to collect, store, or sell such information on their terms. But Apple promises to help manage health and wellness data on the users’ terms. The purpose is to enable easy but secure sharing of complex health information, which can be updated by users or by other devices. Apple has coordinated with other developers to import information to HealthKit from multiple platforms and devices (such as Nike+, Withings Scale, and Fitbit Flex), acting as a central repository of personalized information.

With this technology, it’s easy to envision hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, laboratories, and even insurers integrating bilaterally with any patient information housed on HealthKit, at the discretion of the user. Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Kaiser Permanente, Stanford, UCLA, and Mount Sinai Hospital are all rumored to be working with Apple to figure out how to exchange relevant patient information to enhance the continuity of a patient’s care. In addition to these potential collaborators, electronic health record providers Epic Systems and Allscripts are rumored to be working with Apple in some sort of partnership.3,4

Not only will HealthKit be a secure repository of information, but it will constantly monitor all the metrics and can be programmed to send alerts to key stakeholders, such as family members or healthcare providers, when any of the metrics veer outside predetermined boundaries.4

This “new revolution” in healthcare and wellness should prove extremely helpful to hospitalists, who are often caught in the crosshairs of disjointed patient care delivery systems, and patients who need someone (or something) to track their health and wellness. Imagine a late afternoon admission of a patient who knows exactly what medications she is taking, who can outline several months’ history of caloric intake, physical activity, and basic vital signs, who has an accurate and updated inventory of laboratory exams from other medical centers, and who has a list of all recent physicians and appointments. Although this may seem too good to be true, such an admission may not be too far in the future.

What would be even better is if a patient’s health and wellness tracking keeps him out of the hospital altogether. After all, an Apple a day keeps the doctors away.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. IHI Triple Aim Initiative. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- Apple Inc. Healthkit information page. Available at: https://developer.apple.com/healthkit/. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- The Advisory Board Company. Daily Briefing: Apple in talks with top hospitals to become ‘hub of health data.’ Available at: http://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2014/08/12/apple-in-talks-with-top-hospitals-to-become-hub-of-health-data. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- Sullivan M. VentureBeat News. Apple announces HealthKit platform and new health app. Available at: http://venturebeat.com/2014/06/02/apple-announces-heath-kit-platform-and-health-app/. Accessed August 31, 2014.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) released its Triple Aim Initiative in 2008, challenging the healthcare industry to undergo extensive systematic change, with the following goals:1

- Reduce the per capita cost of healthcare;

- Improve the patient experience of care, including quality and satisfaction; and

- Improve the health of populations.

The first two aims are difficult enough, but the third involves engaging and empowering patients and their families to take ownership of their own health and wellness. This is much more than just understanding what your diagnoses are and which medications to take; it is about getting and staying well. Keeping patients and their families well is a goal that has eluded the healthcare industry since before Hippocrates and is an extremely challenging one for hospitalists, whose time with patients is usually limited to an acute care hospital stay.

Naturally, when one industry cannot figure out how to do something well, another industry will develop a breakthrough innovation. Enter Apple Inc., which has officially moved into the health and wellness business. Apple Health is a new app that will share multiple inputs of patient information in a cloud platform called “HealthKit.” HealthKit will allow a user to view a personalized dashboard of health and fitness metrics, which conglomerates information from a myriad of different health and wellness apps, helping them “communicate” with one another.2

The breadth and choice of health and wellness apps available to users is astounding. In a five-minute browse through the app store on my iPhone, I found the following free options to help patients track and understand their health and wellness:

- MyPlate Calorie Tracker, Calorie Counter, and Fooducate help educate and monitor caloric intake.

- iTriage, WebMD, and Mango Health Medication Manager, which can answer questions about symptoms you may be experiencing, will save a list of medications, conditions, procedures, physicians, appointments, and more, and can help you manage your medications.