User login

Disaster Preparedness in Dermatology Residency Programs

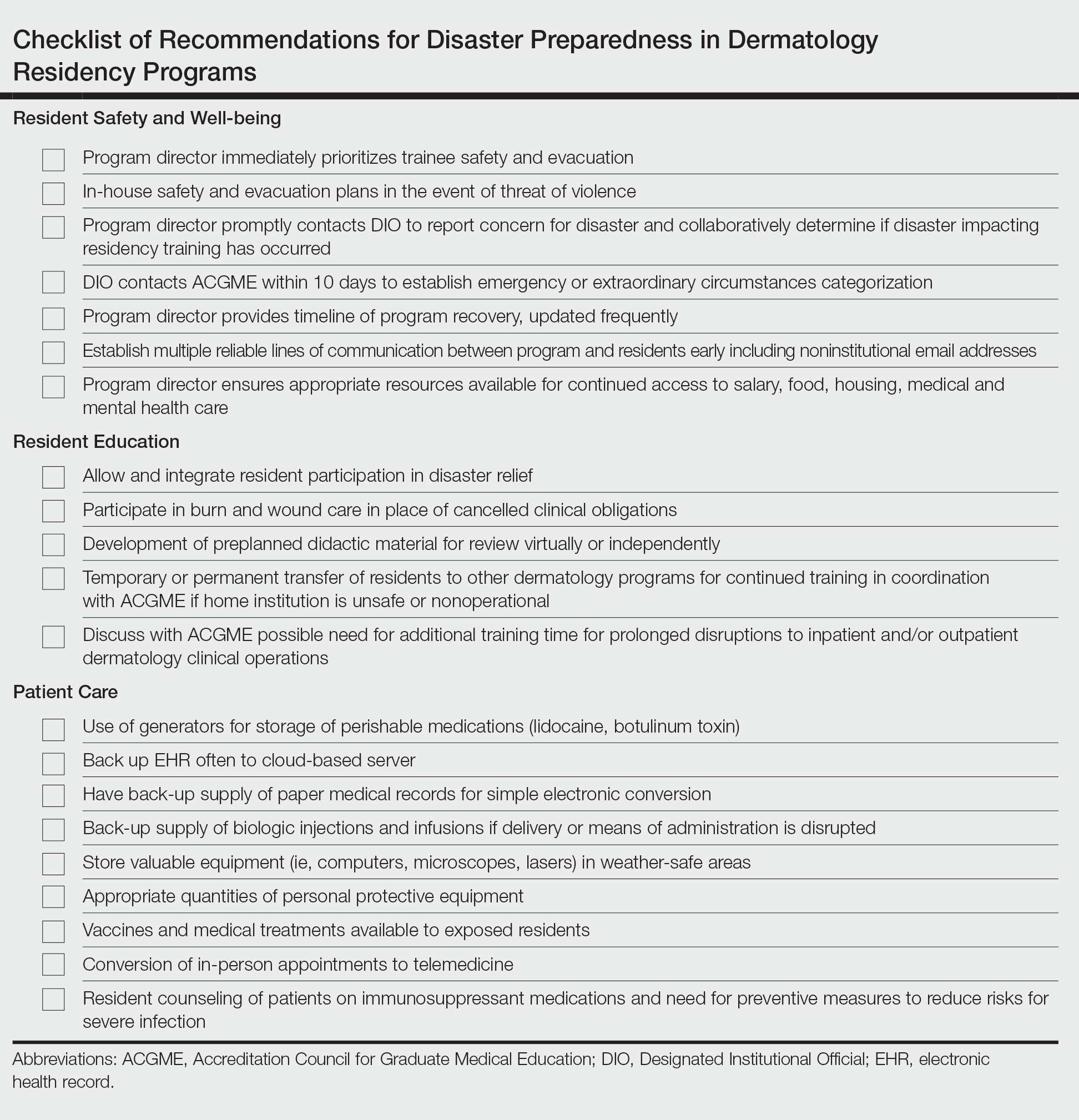

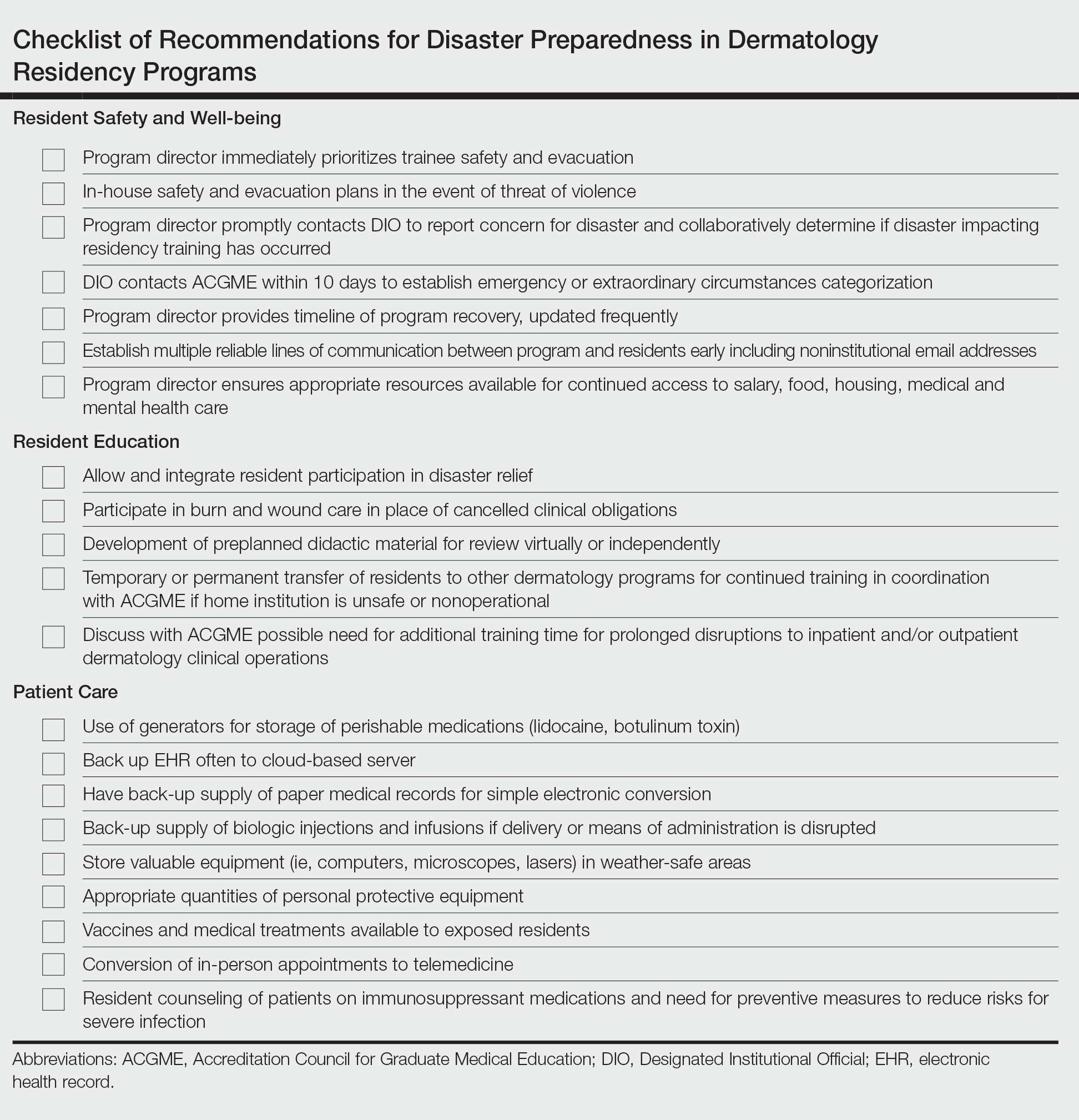

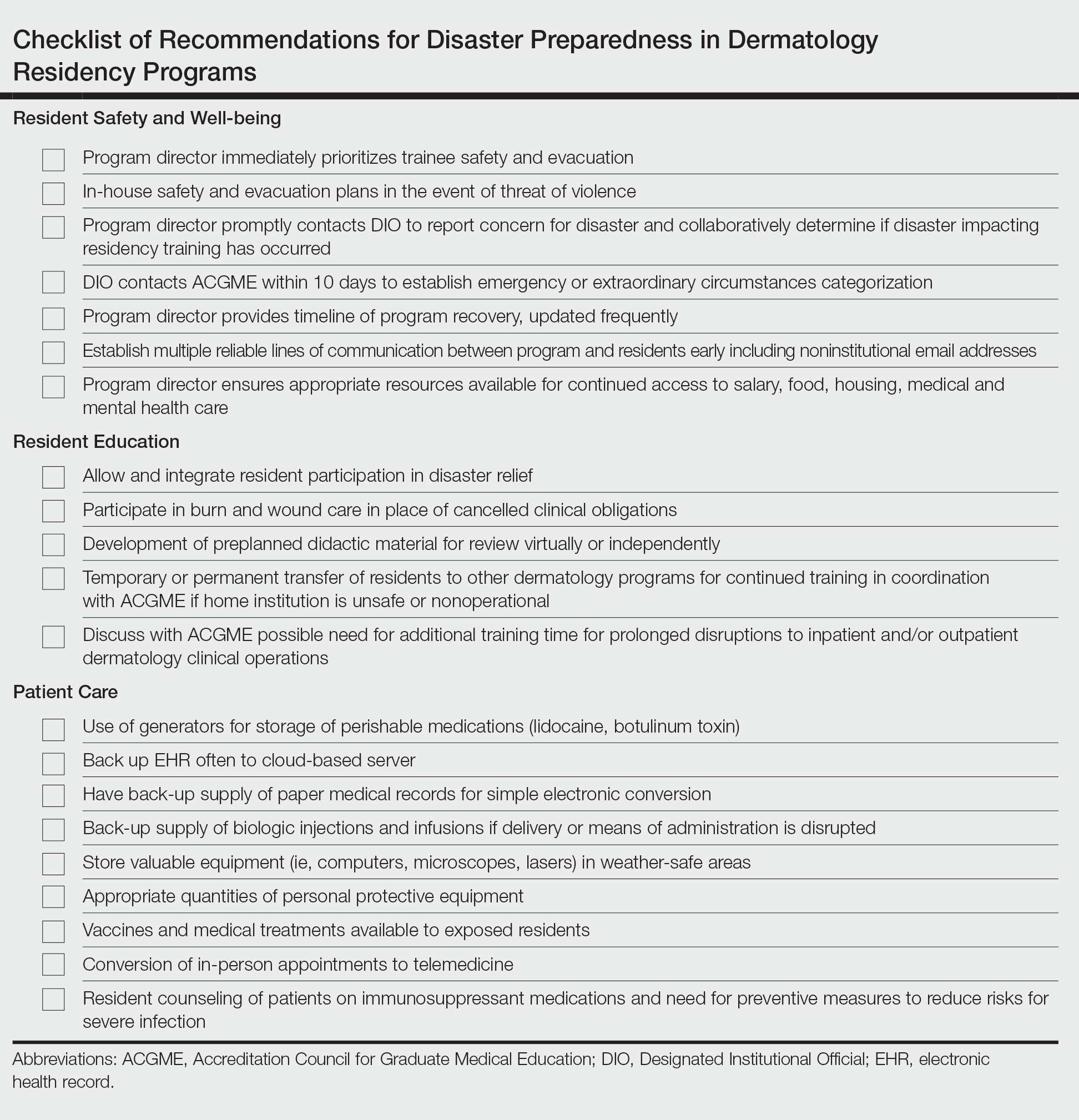

In an age of changing climate and emerging global pandemics, the ability of residency programs to prepare for and adapt to potential disasters may be paramount in preserving the training of physicians. The current literature regarding residency program disaster preparedness, which focuses predominantly on hurricanes and COVID-19,1-8 is lacking in recommendations specific to dermatology residency programs. Likewise, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines9 do not address dermatology-specific concerns in disaster preparedness or response. Herein, we propose recommendations to mitigate the impact of various types of disasters on dermatology residency programs and their trainees with regard to resident safety and wellness, resident education, and patient care (Table).

Resident Safety and Wellness

Role of the Program Director—The role of the program director is critical, serving as a figure of structure and reassurance.4,7,10 Once concern of disaster arises, the program director should contact the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) to express concerns about possible disruptions to resident training. The DIO should then contact the ACGME within 10 days to report the disaster and submit a request for emergency (eg, pandemic) or extraordinary circumstances (eg, natural disaster) categorization.4,9 Program directors should promptly prepare plans for program reconfiguration and resident transfers in alignment with ACGME requirements to maintain evaluation and completion of core competencies of training during disasters.9 Program directors should prioritize the safety of trainees during the immediate threat with clear guidelines on sheltering, evacuations, or quarantines; a timeline of program recovery based on communication with residents, faculty, and administration should then be established.10,11

Communication—Establishing a strong line of communication between program directors and residents is paramount. Collection of emergency noninstitutional contact information, establishment of a centralized website for information dissemination, use of noninstitutional email and proxy servers outside of the location of impact, social media updates, on-site use of 2-way radios, and program-wide conference calls when possible should be strongly considered as part of the disaster response.2-4,12,13

Resident Accommodations and Mental Health—If training is disrupted, residents should be reassured of continued access to salary, housing, food, or other resources as necessary.3,4,11 There should be clear contingency plans if residents need to leave the program for extended periods of time due to injury, illness, or personal circumstances. Although relevant in all types of disasters, resident mental health and response to trauma also must be addressed. Access to counseling, morale-building opportunities (eg, resident social events), and screening for depression or posttraumatic stress disorder may help promote well-being among residents following traumatic events.14

Resident Education

Participation in Disaster Relief—Residents may seek to aid in the disaster response, which may prove challenging in the setting of programs with high patient volume.4 In coordination with the ACGME and graduate medical education governing bodies, program directors should consider how residents may fulfill dermatology training requirements in conjunction with disaster relief efforts, such as working in an inpatient setting or providing wound care.10

Continued Didactic Education—The use of online learning and conference calls for continuing the dermatology curriculum is an efficient means to maintaining resident education when meeting in person poses risks to residents.15 Projections of microscopy images, clinical photographs, or other instructional materials allow for continued instruction on resident examination, histopathology, and diagnostic skills.

Continued Clinical Training—If the home institution cannot support the operation of dermatology clinics, residents should be guaranteed continued training at other institutions. Agreements with other dermatology programs, community hospitals, or private dermatology practices should be established in advance, with consideration given to the number of residents a program can support, funding transfers, and credentialing requirements.2,4,5

Prolonged Disruptions—Nonessential departments of medical institutions may cease to function during war or mass casualty disasters, and it may be unsafe to send dermatology residents to other institutions or clinical areas. If the threat is prolonged, programs may need to consider allowing current residents a longer duration of training despite potential overlap with incoming dermatology residents.7

Patient Care

Disruptions to Clinic Operations—Regarding threats of violence, dangerous exposures, or natural disasters, there should be clear guidelines on sheltering in the clinical setting or stabilizing patients during a procedure.11 Equipment used by residents such as laptops, microscopes, and treatment devices (eg, lasers) should be stored in weather-safe locations that would not be notably impacted by moisture or structural damage to the clinic building. If electricity or internet access are compromised, paper medical records should be available to residents to continue clinical operations. Electronic health records used by residents should regularly be backed up on remote servers or cloud storage to allow continued access to patient health information if on-site servers are not functional.12 If disruptions are prolonged, residency program administration should coordinate with the institution to ensure there is adequate supply and storage of medications (eg, lidocaine, botulinum toxin) as well as a continued means of delivering biologic medications to patients and an ability to obtain laboratory or dermatopathology services.

In-Person Appointments vs Telemedicine—There are benefits to both residency training and patient care when physicians are able to perform in-person examinations, biopsies, and in-office treatments.16 Programs should ensure an adequate supply of personal protective equipment to continue in-office appointments, vaccinations, and medical care if a resident or other members of the team are exposed to an infectious disease.7 If in-person appointments are limited or impossible, telemedicine capabilities may still allow residents to meet program requirements.7,10,15 However, reduced patient volume due to decreased elective visits or procedures may complicate the fulfillment of clinical requirements, which may need to be adjusted in the wake of a disaster.7

Use of Immunosuppressive Therapies—Residency programs should address the risks of prescribing immunosuppressive therapies (eg, biologics) during an infectious threat with their residents and encourage trainees to counsel patients on the importance of preventative measures to reduce risks for severe infection.17

Final Thoughts

- Davis W. Hurricane Katrina: the challenge to graduate medical education. Ochsner J. 2006;6:39.

- Cefalu CA, Schwartz RS. Salvaging a geriatric medicine academic program in disaster mode—the LSU training program post-Katrina.J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:590-596.

- Ayyala R. Lessons from Katrina: a program director’s perspective. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1425-1426.

- Wiese JG. Leadership in graduate medical education: eleven steps instrumental in recovering residency programs after a disaster. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:168-173.

- Griffies WS. Post-Katrina stabilization of the LSU/Ochsner Psychiatry Residency Program: caveats for disaster preparedness. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:418-422.

- Kearns DG, Chat VS, Uppal S, et al. Applying to dermatology residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1214-1215.

- Matthews JB, Blair PG, Ellison EC, et al. Checklist framework for surgical education disaster plans. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:557-563.

- Litchman GH, Marson JW, Rigel DS. The continuing impact of COVID-19 on dermatology practice: office workflow, economics, and future implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:576-579.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Sponsoring institution emergency categorization. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/covid-19/sponsoring-institution-emergency-categorization/

- Li YM, Galimberti F, Abrouk M, et al. US dermatology resident responses about the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a nationwide survey. South Med J. 2020;113:462-465.

- Newman B, Gallion C. Hurricane Harvey: firsthand perspectives for disaster preparedness in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1267-1269.

- Pero CD, Pou AM, Arriaga MA, et al. Post-Katrina: study in crisis-related program adaptability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:394-397.

- Hattaway R, Singh N, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. Adaptations of dermatology residency programs to changes in medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: virtual opportunities and social media. SKIN. 2021;5:94-100.

- Hillier K, Paskaradevan J, Wilkes JK, et al. Disaster plans: resident involvement and well-being during Hurricane Harvey. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:129-131.

- Samimi S, Choi J, Rosman IS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:609-618.

- Bastola M, Locatis C, Fontelo P. Diagnostic reliability of in-person versus remote dermatology: a meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:247-250.

- Bashyam AM, Feldman SR. Should patients stop their biologic treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:317-318.

In an age of changing climate and emerging global pandemics, the ability of residency programs to prepare for and adapt to potential disasters may be paramount in preserving the training of physicians. The current literature regarding residency program disaster preparedness, which focuses predominantly on hurricanes and COVID-19,1-8 is lacking in recommendations specific to dermatology residency programs. Likewise, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines9 do not address dermatology-specific concerns in disaster preparedness or response. Herein, we propose recommendations to mitigate the impact of various types of disasters on dermatology residency programs and their trainees with regard to resident safety and wellness, resident education, and patient care (Table).

Resident Safety and Wellness

Role of the Program Director—The role of the program director is critical, serving as a figure of structure and reassurance.4,7,10 Once concern of disaster arises, the program director should contact the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) to express concerns about possible disruptions to resident training. The DIO should then contact the ACGME within 10 days to report the disaster and submit a request for emergency (eg, pandemic) or extraordinary circumstances (eg, natural disaster) categorization.4,9 Program directors should promptly prepare plans for program reconfiguration and resident transfers in alignment with ACGME requirements to maintain evaluation and completion of core competencies of training during disasters.9 Program directors should prioritize the safety of trainees during the immediate threat with clear guidelines on sheltering, evacuations, or quarantines; a timeline of program recovery based on communication with residents, faculty, and administration should then be established.10,11

Communication—Establishing a strong line of communication between program directors and residents is paramount. Collection of emergency noninstitutional contact information, establishment of a centralized website for information dissemination, use of noninstitutional email and proxy servers outside of the location of impact, social media updates, on-site use of 2-way radios, and program-wide conference calls when possible should be strongly considered as part of the disaster response.2-4,12,13

Resident Accommodations and Mental Health—If training is disrupted, residents should be reassured of continued access to salary, housing, food, or other resources as necessary.3,4,11 There should be clear contingency plans if residents need to leave the program for extended periods of time due to injury, illness, or personal circumstances. Although relevant in all types of disasters, resident mental health and response to trauma also must be addressed. Access to counseling, morale-building opportunities (eg, resident social events), and screening for depression or posttraumatic stress disorder may help promote well-being among residents following traumatic events.14

Resident Education

Participation in Disaster Relief—Residents may seek to aid in the disaster response, which may prove challenging in the setting of programs with high patient volume.4 In coordination with the ACGME and graduate medical education governing bodies, program directors should consider how residents may fulfill dermatology training requirements in conjunction with disaster relief efforts, such as working in an inpatient setting or providing wound care.10

Continued Didactic Education—The use of online learning and conference calls for continuing the dermatology curriculum is an efficient means to maintaining resident education when meeting in person poses risks to residents.15 Projections of microscopy images, clinical photographs, or other instructional materials allow for continued instruction on resident examination, histopathology, and diagnostic skills.

Continued Clinical Training—If the home institution cannot support the operation of dermatology clinics, residents should be guaranteed continued training at other institutions. Agreements with other dermatology programs, community hospitals, or private dermatology practices should be established in advance, with consideration given to the number of residents a program can support, funding transfers, and credentialing requirements.2,4,5

Prolonged Disruptions—Nonessential departments of medical institutions may cease to function during war or mass casualty disasters, and it may be unsafe to send dermatology residents to other institutions or clinical areas. If the threat is prolonged, programs may need to consider allowing current residents a longer duration of training despite potential overlap with incoming dermatology residents.7

Patient Care

Disruptions to Clinic Operations—Regarding threats of violence, dangerous exposures, or natural disasters, there should be clear guidelines on sheltering in the clinical setting or stabilizing patients during a procedure.11 Equipment used by residents such as laptops, microscopes, and treatment devices (eg, lasers) should be stored in weather-safe locations that would not be notably impacted by moisture or structural damage to the clinic building. If electricity or internet access are compromised, paper medical records should be available to residents to continue clinical operations. Electronic health records used by residents should regularly be backed up on remote servers or cloud storage to allow continued access to patient health information if on-site servers are not functional.12 If disruptions are prolonged, residency program administration should coordinate with the institution to ensure there is adequate supply and storage of medications (eg, lidocaine, botulinum toxin) as well as a continued means of delivering biologic medications to patients and an ability to obtain laboratory or dermatopathology services.

In-Person Appointments vs Telemedicine—There are benefits to both residency training and patient care when physicians are able to perform in-person examinations, biopsies, and in-office treatments.16 Programs should ensure an adequate supply of personal protective equipment to continue in-office appointments, vaccinations, and medical care if a resident or other members of the team are exposed to an infectious disease.7 If in-person appointments are limited or impossible, telemedicine capabilities may still allow residents to meet program requirements.7,10,15 However, reduced patient volume due to decreased elective visits or procedures may complicate the fulfillment of clinical requirements, which may need to be adjusted in the wake of a disaster.7

Use of Immunosuppressive Therapies—Residency programs should address the risks of prescribing immunosuppressive therapies (eg, biologics) during an infectious threat with their residents and encourage trainees to counsel patients on the importance of preventative measures to reduce risks for severe infection.17

Final Thoughts

In an age of changing climate and emerging global pandemics, the ability of residency programs to prepare for and adapt to potential disasters may be paramount in preserving the training of physicians. The current literature regarding residency program disaster preparedness, which focuses predominantly on hurricanes and COVID-19,1-8 is lacking in recommendations specific to dermatology residency programs. Likewise, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines9 do not address dermatology-specific concerns in disaster preparedness or response. Herein, we propose recommendations to mitigate the impact of various types of disasters on dermatology residency programs and their trainees with regard to resident safety and wellness, resident education, and patient care (Table).

Resident Safety and Wellness

Role of the Program Director—The role of the program director is critical, serving as a figure of structure and reassurance.4,7,10 Once concern of disaster arises, the program director should contact the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) to express concerns about possible disruptions to resident training. The DIO should then contact the ACGME within 10 days to report the disaster and submit a request for emergency (eg, pandemic) or extraordinary circumstances (eg, natural disaster) categorization.4,9 Program directors should promptly prepare plans for program reconfiguration and resident transfers in alignment with ACGME requirements to maintain evaluation and completion of core competencies of training during disasters.9 Program directors should prioritize the safety of trainees during the immediate threat with clear guidelines on sheltering, evacuations, or quarantines; a timeline of program recovery based on communication with residents, faculty, and administration should then be established.10,11

Communication—Establishing a strong line of communication between program directors and residents is paramount. Collection of emergency noninstitutional contact information, establishment of a centralized website for information dissemination, use of noninstitutional email and proxy servers outside of the location of impact, social media updates, on-site use of 2-way radios, and program-wide conference calls when possible should be strongly considered as part of the disaster response.2-4,12,13

Resident Accommodations and Mental Health—If training is disrupted, residents should be reassured of continued access to salary, housing, food, or other resources as necessary.3,4,11 There should be clear contingency plans if residents need to leave the program for extended periods of time due to injury, illness, or personal circumstances. Although relevant in all types of disasters, resident mental health and response to trauma also must be addressed. Access to counseling, morale-building opportunities (eg, resident social events), and screening for depression or posttraumatic stress disorder may help promote well-being among residents following traumatic events.14

Resident Education

Participation in Disaster Relief—Residents may seek to aid in the disaster response, which may prove challenging in the setting of programs with high patient volume.4 In coordination with the ACGME and graduate medical education governing bodies, program directors should consider how residents may fulfill dermatology training requirements in conjunction with disaster relief efforts, such as working in an inpatient setting or providing wound care.10

Continued Didactic Education—The use of online learning and conference calls for continuing the dermatology curriculum is an efficient means to maintaining resident education when meeting in person poses risks to residents.15 Projections of microscopy images, clinical photographs, or other instructional materials allow for continued instruction on resident examination, histopathology, and diagnostic skills.

Continued Clinical Training—If the home institution cannot support the operation of dermatology clinics, residents should be guaranteed continued training at other institutions. Agreements with other dermatology programs, community hospitals, or private dermatology practices should be established in advance, with consideration given to the number of residents a program can support, funding transfers, and credentialing requirements.2,4,5

Prolonged Disruptions—Nonessential departments of medical institutions may cease to function during war or mass casualty disasters, and it may be unsafe to send dermatology residents to other institutions or clinical areas. If the threat is prolonged, programs may need to consider allowing current residents a longer duration of training despite potential overlap with incoming dermatology residents.7

Patient Care

Disruptions to Clinic Operations—Regarding threats of violence, dangerous exposures, or natural disasters, there should be clear guidelines on sheltering in the clinical setting or stabilizing patients during a procedure.11 Equipment used by residents such as laptops, microscopes, and treatment devices (eg, lasers) should be stored in weather-safe locations that would not be notably impacted by moisture or structural damage to the clinic building. If electricity or internet access are compromised, paper medical records should be available to residents to continue clinical operations. Electronic health records used by residents should regularly be backed up on remote servers or cloud storage to allow continued access to patient health information if on-site servers are not functional.12 If disruptions are prolonged, residency program administration should coordinate with the institution to ensure there is adequate supply and storage of medications (eg, lidocaine, botulinum toxin) as well as a continued means of delivering biologic medications to patients and an ability to obtain laboratory or dermatopathology services.

In-Person Appointments vs Telemedicine—There are benefits to both residency training and patient care when physicians are able to perform in-person examinations, biopsies, and in-office treatments.16 Programs should ensure an adequate supply of personal protective equipment to continue in-office appointments, vaccinations, and medical care if a resident or other members of the team are exposed to an infectious disease.7 If in-person appointments are limited or impossible, telemedicine capabilities may still allow residents to meet program requirements.7,10,15 However, reduced patient volume due to decreased elective visits or procedures may complicate the fulfillment of clinical requirements, which may need to be adjusted in the wake of a disaster.7

Use of Immunosuppressive Therapies—Residency programs should address the risks of prescribing immunosuppressive therapies (eg, biologics) during an infectious threat with their residents and encourage trainees to counsel patients on the importance of preventative measures to reduce risks for severe infection.17

Final Thoughts

- Davis W. Hurricane Katrina: the challenge to graduate medical education. Ochsner J. 2006;6:39.

- Cefalu CA, Schwartz RS. Salvaging a geriatric medicine academic program in disaster mode—the LSU training program post-Katrina.J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:590-596.

- Ayyala R. Lessons from Katrina: a program director’s perspective. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1425-1426.

- Wiese JG. Leadership in graduate medical education: eleven steps instrumental in recovering residency programs after a disaster. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:168-173.

- Griffies WS. Post-Katrina stabilization of the LSU/Ochsner Psychiatry Residency Program: caveats for disaster preparedness. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:418-422.

- Kearns DG, Chat VS, Uppal S, et al. Applying to dermatology residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1214-1215.

- Matthews JB, Blair PG, Ellison EC, et al. Checklist framework for surgical education disaster plans. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:557-563.

- Litchman GH, Marson JW, Rigel DS. The continuing impact of COVID-19 on dermatology practice: office workflow, economics, and future implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:576-579.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Sponsoring institution emergency categorization. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/covid-19/sponsoring-institution-emergency-categorization/

- Li YM, Galimberti F, Abrouk M, et al. US dermatology resident responses about the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a nationwide survey. South Med J. 2020;113:462-465.

- Newman B, Gallion C. Hurricane Harvey: firsthand perspectives for disaster preparedness in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1267-1269.

- Pero CD, Pou AM, Arriaga MA, et al. Post-Katrina: study in crisis-related program adaptability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:394-397.

- Hattaway R, Singh N, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. Adaptations of dermatology residency programs to changes in medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: virtual opportunities and social media. SKIN. 2021;5:94-100.

- Hillier K, Paskaradevan J, Wilkes JK, et al. Disaster plans: resident involvement and well-being during Hurricane Harvey. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:129-131.

- Samimi S, Choi J, Rosman IS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:609-618.

- Bastola M, Locatis C, Fontelo P. Diagnostic reliability of in-person versus remote dermatology: a meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:247-250.

- Bashyam AM, Feldman SR. Should patients stop their biologic treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:317-318.

- Davis W. Hurricane Katrina: the challenge to graduate medical education. Ochsner J. 2006;6:39.

- Cefalu CA, Schwartz RS. Salvaging a geriatric medicine academic program in disaster mode—the LSU training program post-Katrina.J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:590-596.

- Ayyala R. Lessons from Katrina: a program director’s perspective. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1425-1426.

- Wiese JG. Leadership in graduate medical education: eleven steps instrumental in recovering residency programs after a disaster. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336:168-173.

- Griffies WS. Post-Katrina stabilization of the LSU/Ochsner Psychiatry Residency Program: caveats for disaster preparedness. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:418-422.

- Kearns DG, Chat VS, Uppal S, et al. Applying to dermatology residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1214-1215.

- Matthews JB, Blair PG, Ellison EC, et al. Checklist framework for surgical education disaster plans. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:557-563.

- Litchman GH, Marson JW, Rigel DS. The continuing impact of COVID-19 on dermatology practice: office workflow, economics, and future implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:576-579.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Sponsoring institution emergency categorization. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/covid-19/sponsoring-institution-emergency-categorization/

- Li YM, Galimberti F, Abrouk M, et al. US dermatology resident responses about the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a nationwide survey. South Med J. 2020;113:462-465.

- Newman B, Gallion C. Hurricane Harvey: firsthand perspectives for disaster preparedness in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1267-1269.

- Pero CD, Pou AM, Arriaga MA, et al. Post-Katrina: study in crisis-related program adaptability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:394-397.

- Hattaway R, Singh N, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. Adaptations of dermatology residency programs to changes in medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: virtual opportunities and social media. SKIN. 2021;5:94-100.

- Hillier K, Paskaradevan J, Wilkes JK, et al. Disaster plans: resident involvement and well-being during Hurricane Harvey. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:129-131.

- Samimi S, Choi J, Rosman IS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:609-618.

- Bastola M, Locatis C, Fontelo P. Diagnostic reliability of in-person versus remote dermatology: a meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:247-250.

- Bashyam AM, Feldman SR. Should patients stop their biologic treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:317-318.

Practice Points

- Dermatology residency programs should prioritize the development of disaster preparedness plans prior to the onset of disasters.

- Comprehensive disaster preparedness addresses many possible disruptions to dermatology resident training and clinic operations, including natural and manmade disasters and threats of widespread infectious disease.

- Safety being paramount, dermatology residency programs may be tasked with maintaining resident wellness, continuing resident education—potentially in unconventional ways—and adapting clinical operations to continue patient care.

Differences in Underrepresented in Medicine Applicant Backgrounds and Outcomes in the 2020-2021 Dermatology Residency Match

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

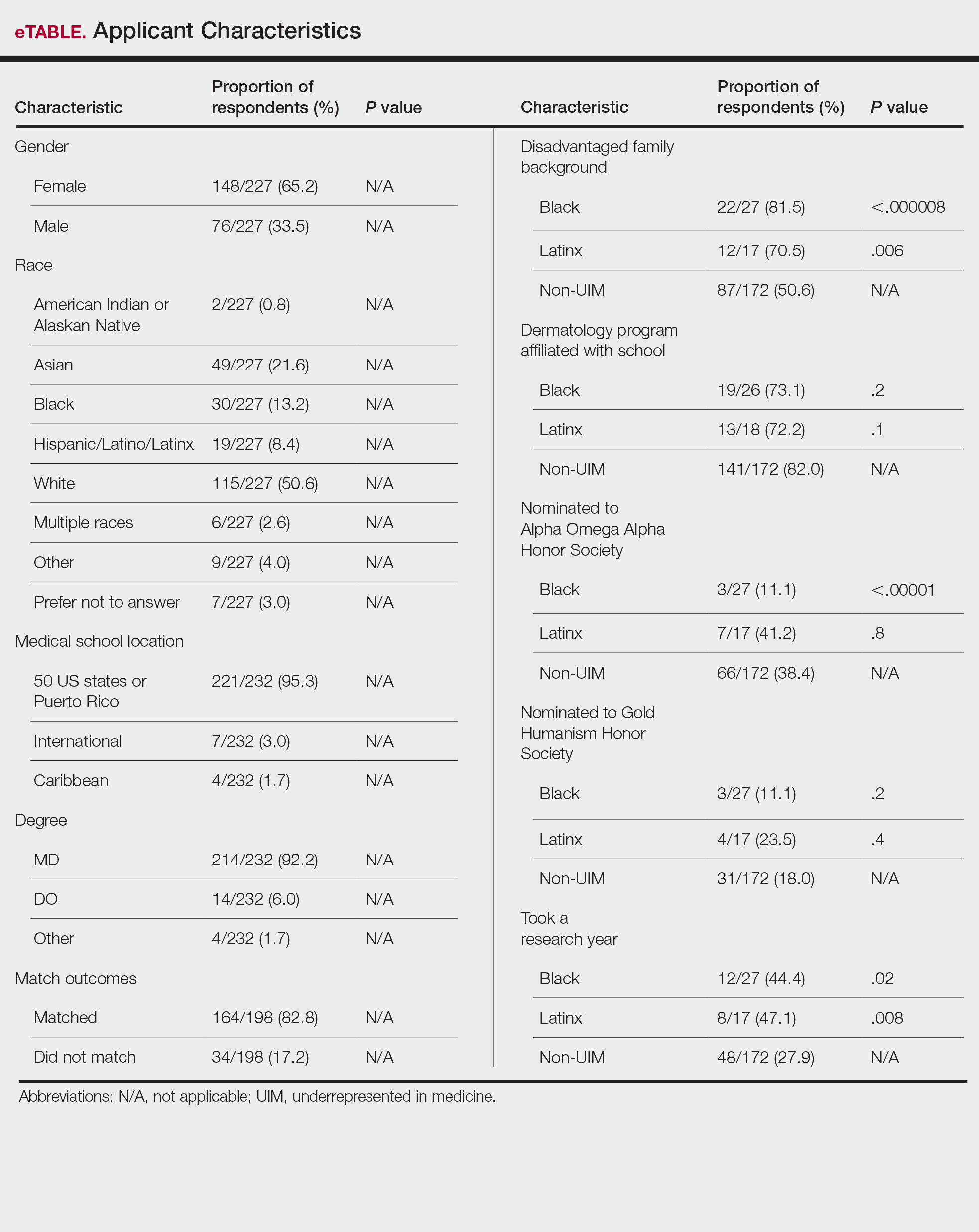

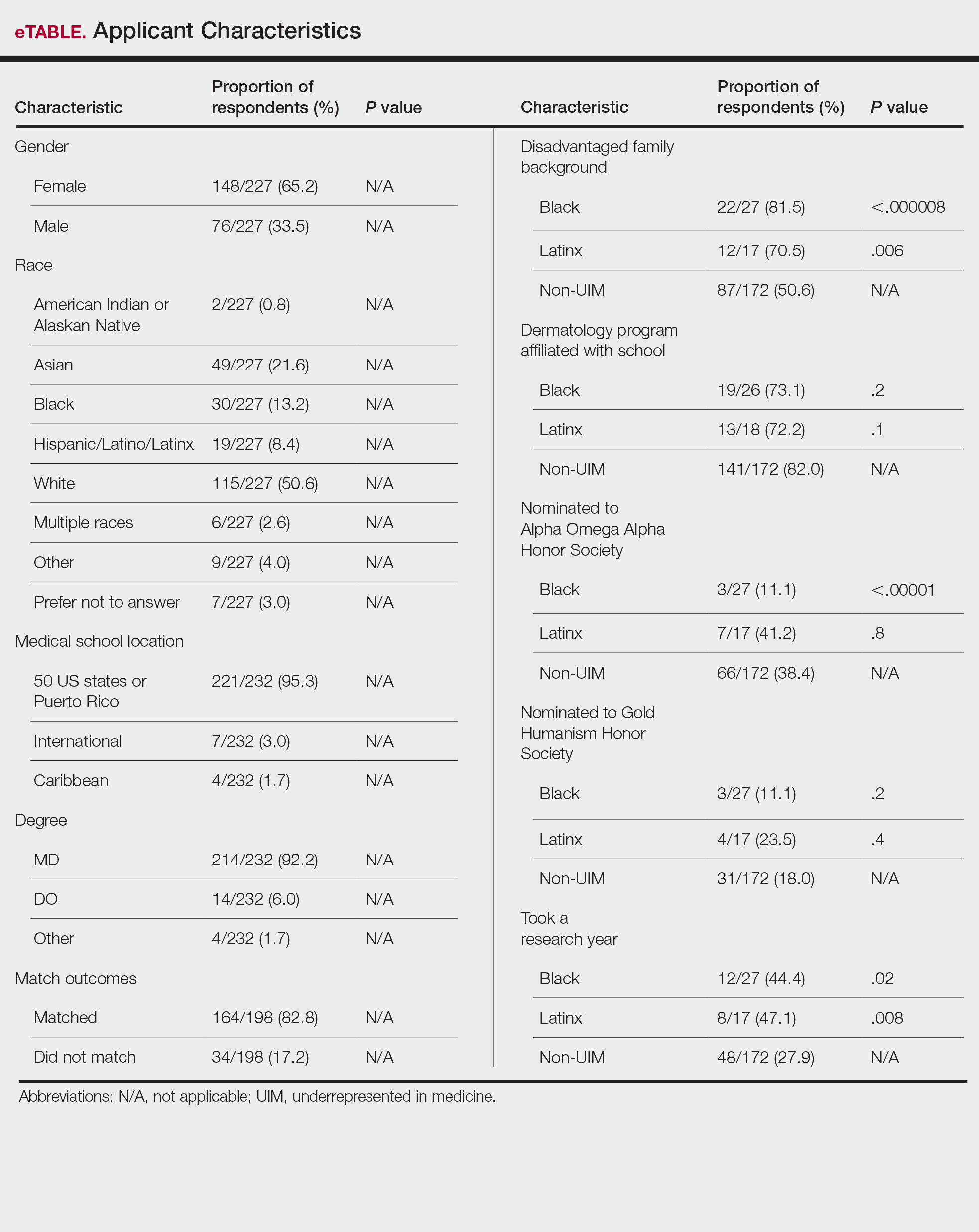

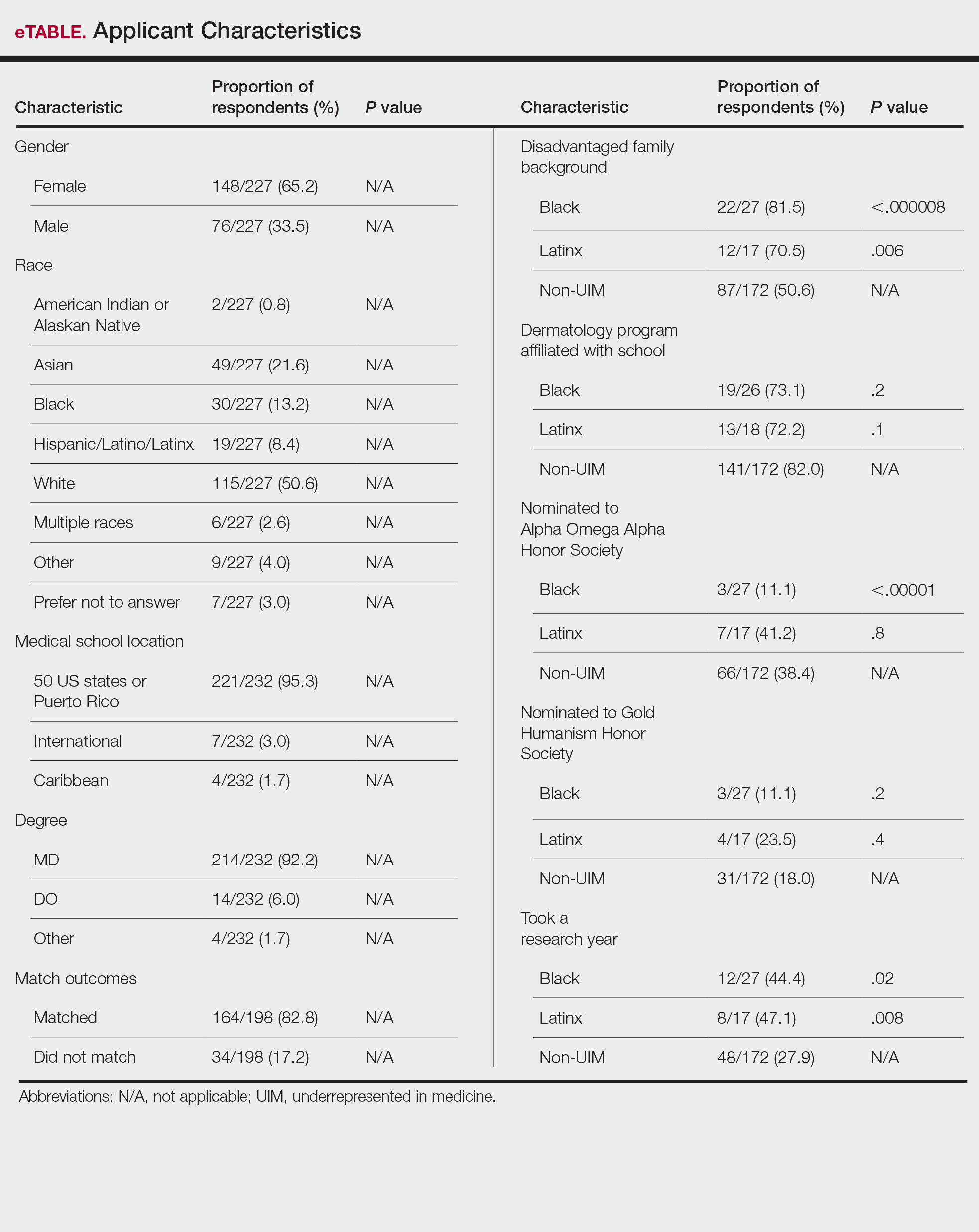

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

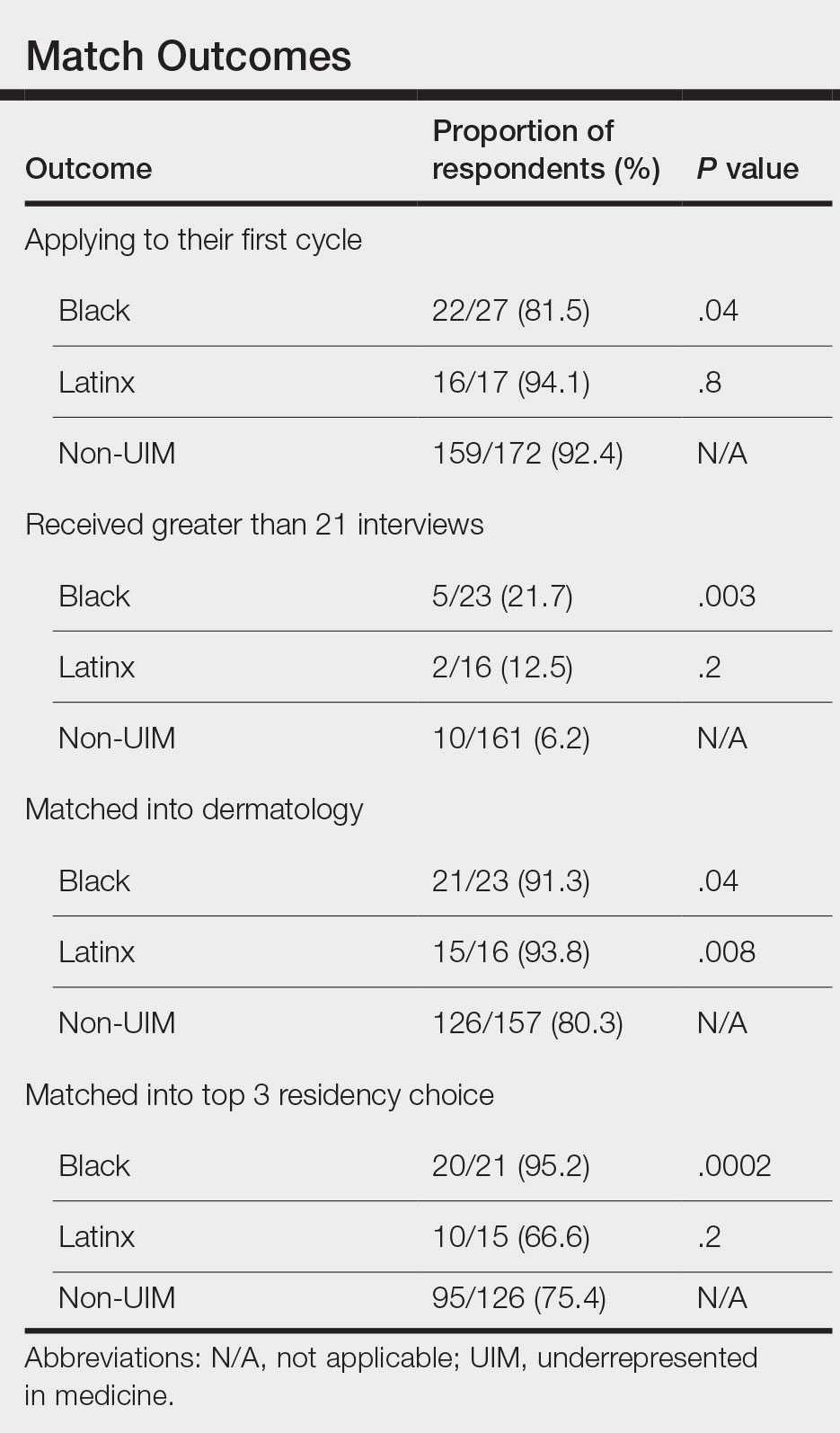

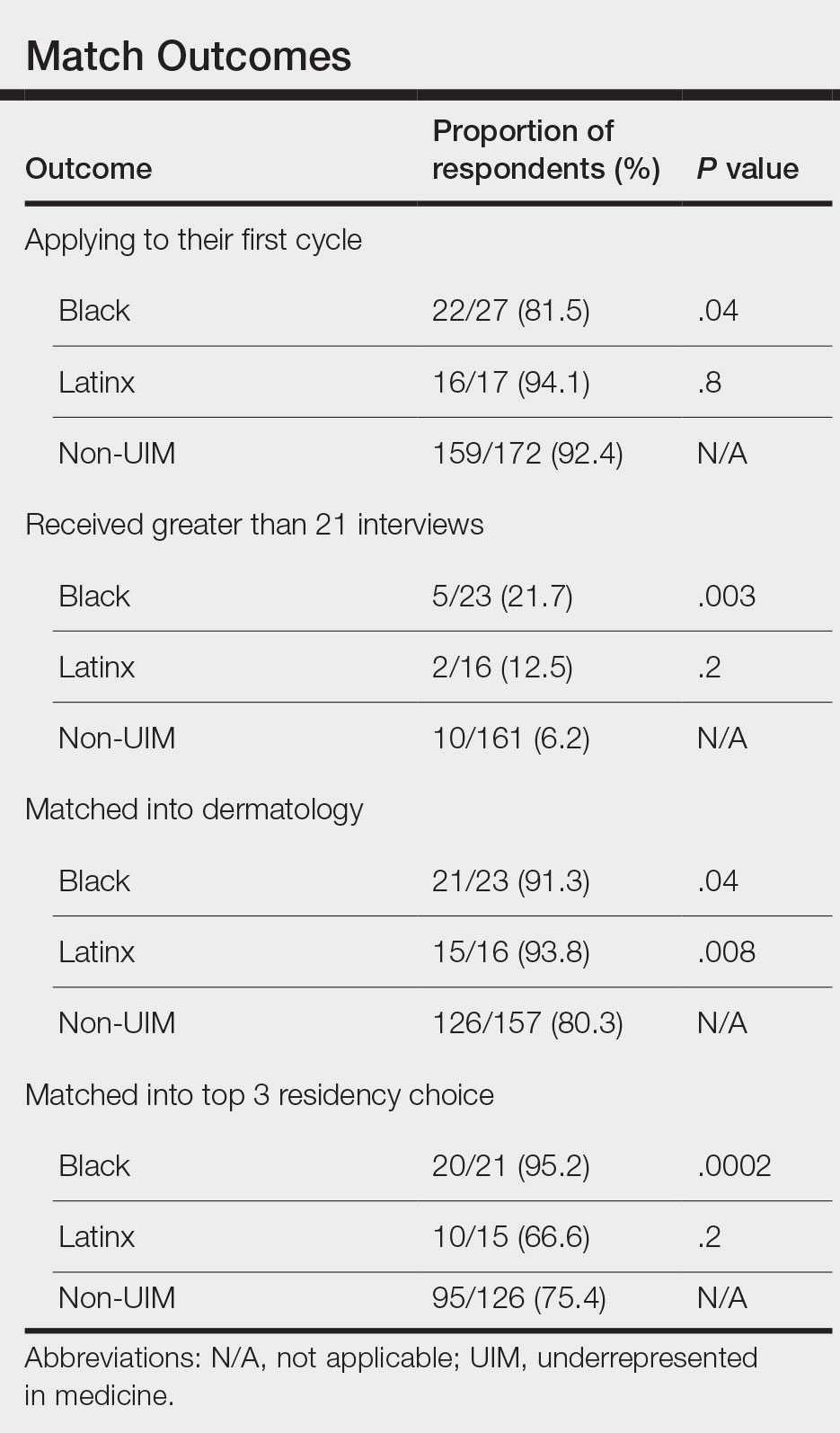

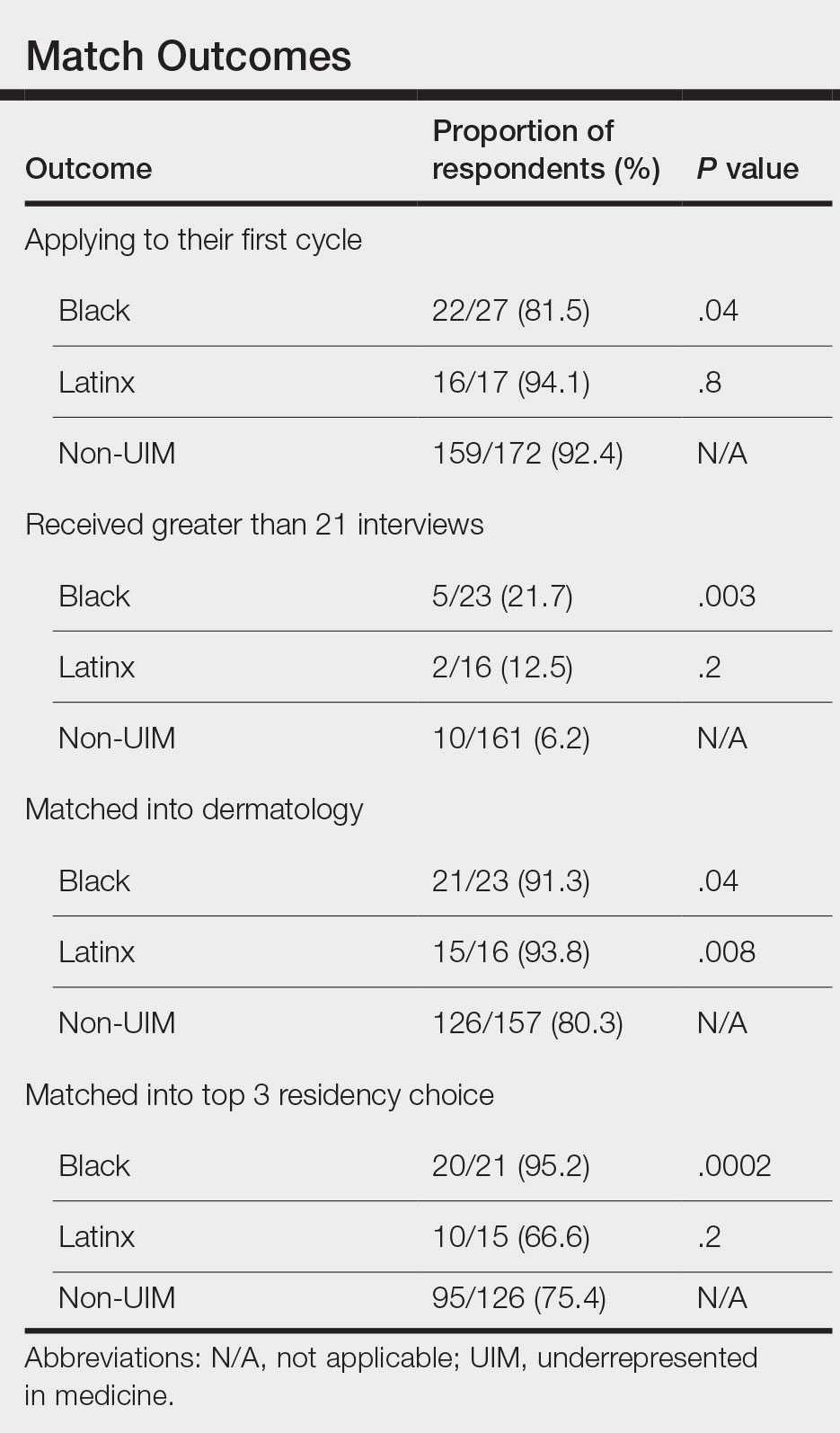

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

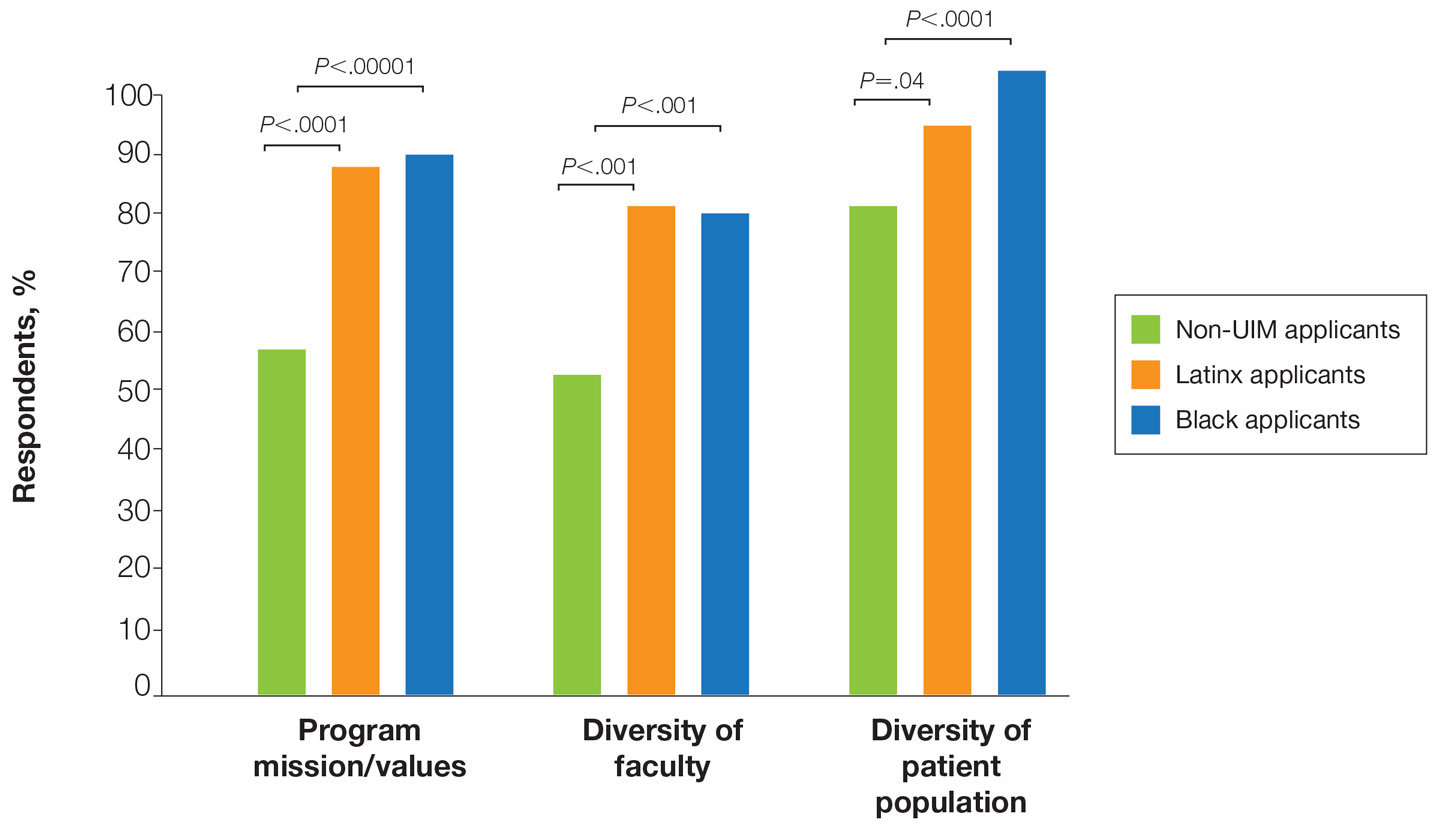

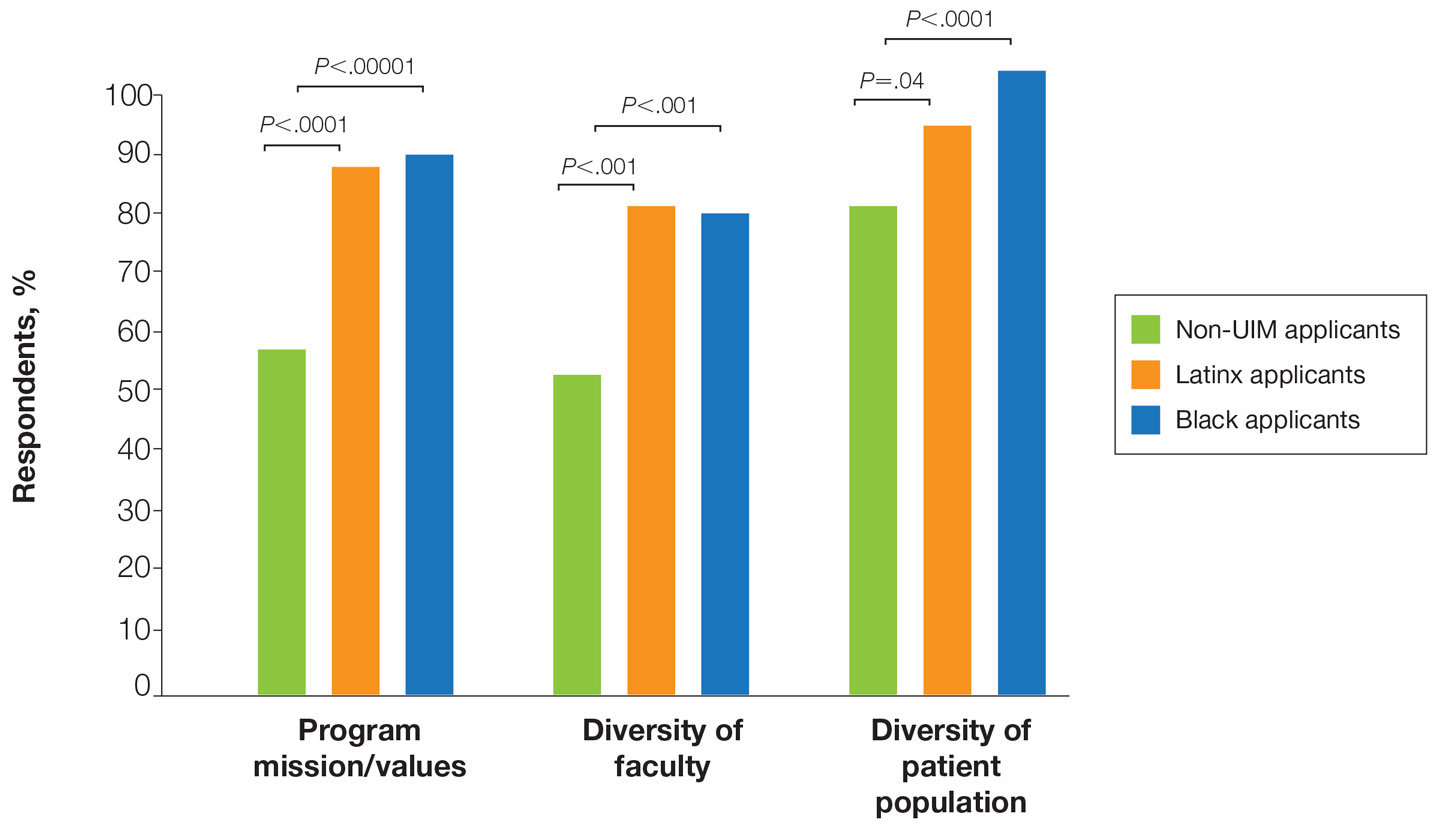

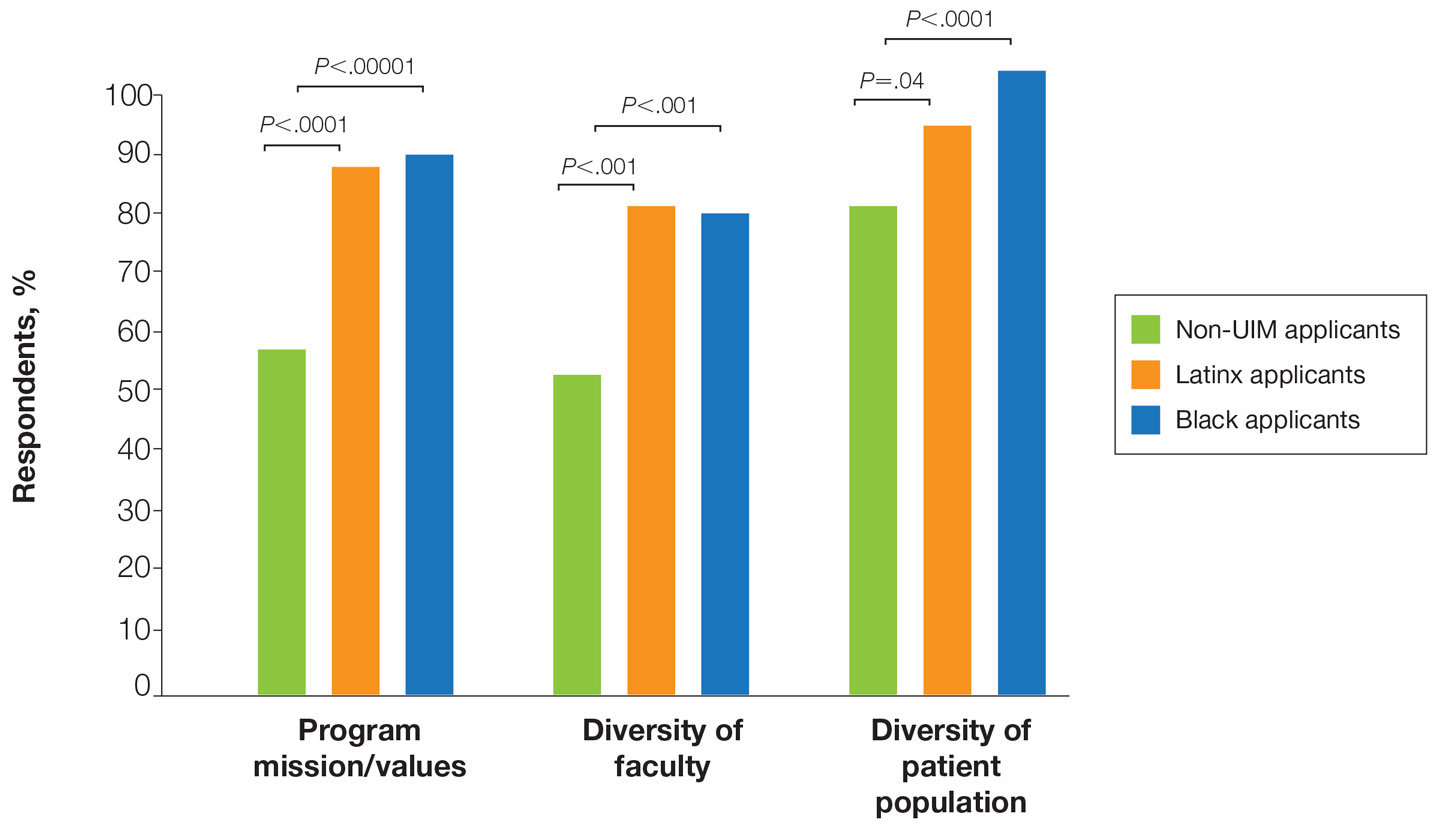

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Practice Points

- Underrepresented in medicine (UIM) dermatology residency applicants (Black and Latinx) are more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds and to have financial concerns about the residency application process.

- When choosing a dermatology residency program, diversity of patients and faculty are more important to UIM dermatology residency applicants than to their non-UIM counterparts.

- Increased awareness of and focus on a holistic review process by dermatology residency programs may contribute to higher rates of matching among Black applicants in our study.

The ERAS Supplemental Application: Current Status and Recommendations for Dermatology Applicants and Programs

In the 2021-2022 residency application cycle, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) piloted a supplemental application to accompany the standard residency application submitted via the AAMC’s Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS).1 Dermatology was 1 of 3 specialties to participate in the pilot alongside internal medicine and general surgery. The goal was to develop a tool that could align applicants with programs that best matched their career goals as well as program and geographic preferences. The Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section was an early advocate for the supplemental application, and members of our leadership were involved in the design, implementation, and evaluation of the pilot supplemental application.

Participating in the supplemental application was optional for both applicants and programs. The supplemental application included a Past Experiences section, which allowed applicants to highlight their 5 most meaningful research, work, and/or volunteer experiences and to describe a challenging life event that might not otherwise be included with their application. The geographic preferences section permitted applicants to select up to 3 regions of interest as well as to indicate an urban vs rural preference. Lastly, a preference-signaling section allowed dermatology applicants to send signals to up to 3 programs of particular interest.

With the close of another application cycle, applicants and programs will begin preparing for the 2022-2023 recruitment season. In this column, we present dermatology-specific data regarding the supplemental application, highlight tentative changes for the upcoming application cycle, and offer tips for applicants and programs as we approach year 2 of the supplemental application.

Results of Supplemental Application Evaluation Surveys

During the 2021-2022 recruitment season, 93% (950/1019) of dermatology applicants submitted the supplemental application, and 87% (117/135) of dermatology residency programs participated in the pilot.2 Surveys conducted by the AAMC between October 2021 and January 2022 showed that a large majority of dermatology programs used supplemental application data during initial application review when deciding who to interview. Eighty-three percent (40/48) of program directors felt that preference signals in particular helped them identify applicants they would have otherwise overlooked. Fifty-seven percent (4288/7516) of applicants across all specialties that participated in the pilot felt that preference signals would help them be noticed by their preferred programs.2 Preference signals were not evenly distributed among dermatology programs. Programs received an average of 23 signals, with a range of 2 to 87 (AAMC, unpublished data, February 2022).

Additional questions remain to be answered: How does the number of signals received affect application review? How often do geographic and program signals convert to interview offers and matches? Regardless, enthusiasm among dermatology programs for the supplemental application remains. In a recent survey of Association of Professors of Dermatology program directors, all 43 respondents planned to participate in the supplemental application again in the upcoming year (Ilana Rosman, MD; unpublished data; February 2022). The pilot will be expanded to include at least 12 other specialties.1As many who reviewed residency applications in 2021-2022 will attest, there was difficulty accessing the supplemental application data because it was not integrated into the Program Directors’ Work Station, the ERAS platform for programs to access applications, which will be remedied for the 2022-2023 iteration. Other tentative changes include modifications to the past experiences sections and timeline of the application.2

Utilizing the Supplemental Application: Recommendations to Applicants

Format of the Application—Applicants should familiarize themselves with the format of the supplemental application in advance and give themselves sufficient time to complete the application. In general, 3 to 4 hours of focused work should be enough time. Applicants should proofread for grammar and spelling before submitting.

Past Experiences—The past experiences section is intended to provide a focused snapshot of an applicant’s most meaningful activities and unique path to residency. Applicants should answer honestly based on their interests. If a student’s focus has been on volunteerism, the bulk of their 5 experiences listed may be related to service. Similarly, a student who has focused on research may preferentially highlight those experiences. In place of the long list of research, volunteer, and work experiences in the traditional ERAS application, applicants can highlight those activities in which they have been most invested. Applicants are encouraged to reflect on all genres of activities at any stage of their careers, even those not medical in nature, including work experience, military service, college athletics, or sustained musical or artistic achievement. Applicants should explain why each experience is meaningful rather than simply describing the activity.

Applicants also have the option to share a notable challenge they have overcome. It is not expected that each applicant will complete this question; in general, applicants who have not faced notable personal or professional obstacles should avoid answering. Additionally, if these challenges have been discussed in other areas of the application—for example, in the personal statement or medical student performance evaluation—it is not necessary to restate them here, though applicants can choose to do so. Examples of topics a student might discuss include being a first-generation college or medical student, growing up in poverty, facing notable personal or family health challenges, or having limited educational opportunities. It is important to share how this experience impacted an applicant’s journey to dermatology residency.

Geographic Preferences—The geographic preferences section can be difficult for applicants to navigate, as it may involve balancing a desire to attend a residency program in a particular region vs a greater desire to simply match in dermatology. In the past, programs may have made assumptions about geographic preferences based on an applicant’s birthplace, hometown, or medical school. In the supplemental application, applicants have the opportunity to directly reveal their preferences. We encourage applicants to be candid. Selecting a geographic region will not necessarily exclude applicants from consideration at other programs. For some applicants, program qualities may be more important than geography, or there may be no regional preferences. Those applicants can choose “no geographic preference.” There is considerable variability in how programs use geographic preferences. For this reason, it is in the best interest of applicants to simply respond honestly.

Preference Signaling—Preference signaling allows applicants to signal up to 3 preferred programs. Dermatology program directors agree that applicants should not signal their home program or programs at which they did in-person away rotations, as those programs would already be aware of the applicant’s interest. Although a signal increases the chances that the application will be reviewed holistically, it does not guarantee an interview offer. Programs may differentially utilize signals depending on multiple factors, including the number of signals received. We encourage applicants to discuss preference signaling strategies with advisors and focus on signaling programs in which they have genuine interest.

Recommendations to Selection Committees and Program Directors