User login

Hysteroscopy and COVID-19: Have recommended techniques changed due to the pandemic?

The emergence of the coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) in December 2019, has resulted in a global pandemic that has challenged the medical community and will continue to represent a public health emergency for the next several months.1 It has rapidly spread globally, infecting many individuals in an unprecedented rate of infection and worldwide reach. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID-19 as a pandemic. While the majority of infected individuals are asymptomatic or develop only mild symptoms, some have an unfortunate clinical course resulting in multi-organ failure and death.2

It is accepted that the virus mainly spreads during close contact and via respiratory droplets.3 The average time from infection to onset of symptoms ranges from 2 to 14 days, with an average of 5 days.4 Recommended measures to prevent the spread of the infection include social distancing (at least 6 feet from others), meticulous hand hygiene, and wearing a mask covering the mouth and nose when in public.5 Aiming to mitigate the risk of viral dissemination for patients and health care providers, and to preserve hospital resources, all nonessential medical interventions were initially suspended. Recently, the American College of Surgeons in a joint statement with 9 women’s health care societies have provided recommendations on how to resume clinical activities as we recover from the pandemic.6

As we reinitiate clinical activities, gynecologists have been alerted of the potential risk of viral dissemination during gynecologic minimally invasive surgical procedures due to the presence of the virus in blood, stool, and the potential risk of aerosolization of the virus, especially when using smoke-generating devices.7,8 This risk is not limited to intubation and extubation of the airway during anesthesia; the risk also presents itself during other aerosol-generating procedures, such as laparoscopy or robotic surgery.9,10

Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard procedure for the diagnosis and management of intrauterine pathologies.11 It is frequently performed in an office setting without the use of anesthesia.11,12 It is usually well tolerated, with only a few patients reporting discomfort.12 It allows for immediate treatment (using the “see and treat” approach) while avoiding not only the risk of anesthesia, as stated, but also the need for intubation—which has a high risk of droplet contamination in COVID-19–infected individuals.13

Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures?

The novel and rapidly changing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic present many challenges to the gynecologist. Significant concerns have been raised regarding potential risk of viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery due to aerosolization of viral particles and the presence of the virus in blood and the gastrointestinal tract of infected patients.7 Diagnostic, and some simple, hysteroscopic procedures are commonly performed in an outpatient setting, with the patient awake. Complex hysteroscopic interventions, however, are generally performed in the operating room, typically with the use of general anesthesia. Hysteroscopy has the theoretical risks of viral dissemination when performed in COVID-19–positive patients. Two important questions must be addressed to better understand the potential risk of COVID-19 viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures.

Continue to: 1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?...

1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?

Recent studies have confirmed the presence of viral particles in urine, feces, blood, and tears in addition to the respiratory tract in patients infected with COVID-19.3,14,15 The presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the female genital system is currently unknown. Previous studies, of other epidemic viral infections, have demonstrated the presence of the virus in the female genital tract in affected patients of Zika virus and Ebola.16,17 However, 2 recent studies have failed to demonstrate the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the vaginal fluid of pregnant14 and not pregnant18 women with severe COVID-19 infection.

2. Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopy if using electrosurgery?

There are significant concerns with possible risk of COVID-19 transmission to health care providers in direct contact with infected patients during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures due to direct contamination and aerosolization of the virus.10,19 Current data on COVID-19 transmission during surgery are limited. However, it is important to recognize that viral aerosolization has been documented with other viral diseases, such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B.20 A recent report called for awareness in the surgical community about the potential risks of COVID-19 viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery. Among other recommendations, international experts advised minimizing the use of electrosurgery to reduce the creation of surgical plume, decreasing the pneumoperitoneum pressure to minimum levels, and using suction devices in a closed system.21 Although these preventive measures apply to laparoscopic surgery, it is important to consider that hysteroscopy is performed in a unique environment.

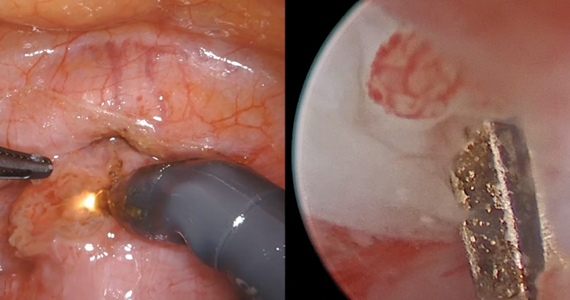

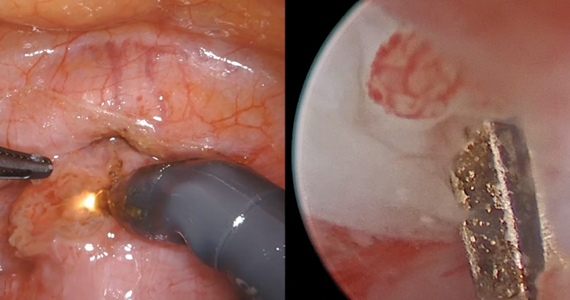

During hysteroscopy the uterine cavity is distended with a liquid medium (normal saline or electrolyte-free solutions); this is opposed to gynecologic laparoscopy, in which the peritoneal cavity is distended with carbon dioxide.22 The smoke produced with the use of hysteroscopic electrosurgical instruments generates bubbles that are immediately cooled down to the temperature of the distention media and subsequently dissolve into it. Therefore, there are no bubbles generated during hysteroscopic surgery that are subsequently released into the air. This results in a low risk for viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures. Nevertheless, the necessary precautions to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission during hysteroscopic intervention are extremely important.

Recommendations for hysteroscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic

We provide our overall recommendations for hysteroscopy, as well as those specific to the office and hospital setting.

Recommendations: General

Limit hysteroscopic procedures to COVID-19–negative patients and to those patients in whom delaying the procedure could result in adverse clinical outcomes.23

Universally screen for potential COVID-19 infection. When possible, a phone interview to triage patients based on their symptoms and infection exposure status should take place before the patient arrives to the health care center. Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection who require immediate evaluation should be directed to COVID-19–designated emergency areas.

Universally test for SARS-CoV-2 before procedures performed in the operating room (OR). Using nasopharyngeal swabs for the detection of viral RNA, employing molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), within 48 to 72 hours prior to all OR hysteroscopic procedures is strongly recommended. Adopting this testing strategy will aid to identify asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2‒infected patients, allowing to defer the procedure, if possible, among patients testing positive. If tests are limited, testing only patients scheduled for hysteroscopic procedures in which general or regional anesthesia will be required is acceptable.

Universal SARS-CoV-2 testing of patients undergoing in-office hysteroscopic diagnostic or minor operative procedures without the use of anesthesia is not required.

Limit the presence of a companion. It is understood that visitor policies may vary at the discretion of each institution’s guidelines. Children and individuals over the age of 60 years should not be granted access to the center. Companions will be subjected to the same screening criteria as patients.

Provide for social distancing and other precautionary measures. If more than one patient is scheduled to be at the facility at the same time, ensure that the facility provides adequate space to allow the appropriate social distancing recommendations between patients. Hand sanitizers and facemasks should be available for patients and companions.

Provide PPE for clinicians. All health care providers in close contact with the patient must wear personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes an apron and gown, a surgical mask, eye protection, and gloves. Health care providers should wear PPE deemed appropriate by their regulatory institutions following their local and national guidelines during clinical patient interactions.

Restrict surgical attendees to vital personnel. The participation of learners by physical presence in the office or operating room should be restricted.

Continue to: Recommendations: Office setting...

Recommendations: Office setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Advise patients to come to the office alone. If the patient requires a companion, a maximum of one adult companion under the age of 60 should be accepted.

- Limit the number of health care team members present in the procedure room.

Intraprocedural recommendations

- Choose the appropriate device(s) that will allow for an effective and fast procedure.

- Use the recommended PPE for all clinicians.

- Limit the movement of staff members in and out of the procedure room.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same procedure room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Allow for patients to recover from the procedure in the same room as the procedure took place in order to avoid potential contamination of multiple rooms.

- Expedite patient discharge.

- Follow up after the procedure by phone or telemedicine.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Continue to: Recommendations: Operating room setting...

Recommendations: Operating room setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Perform adequate patient screening for potential COVID-19 infection. (Screening should be independent of symptoms and not be limited to those with clinical symptoms.)

- Limit the number of health care team members in the operating procedure room.

- To minimize unnecessary staff exposure, have surgeons and staff not needed for intubation remain outside the OR until intubation is completed and leave the OR before extubation.

Intraprocedure recommendations

- Limit personnel in the OR to a minimum.

- Staff should not enter or leave the room during the procedure.

- When possible, use conscious sedation or regional anesthesia to avoid the risk of viral dissemination at the time of intubation/extubation.

- Choose the device that will allow an effective and fast procedure.

- Favor non–smoke-generating devices, such as hysteroscopic scissors, graspers, and tissue retrieval systems.

- Connect active suction to the outflow, especially when using smoke-generating instruments, to facilitate the extraction of surgical smoke.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Expedite postprocedure recovery and patient discharge.

- After completion of the procedure, staff should remove scrubs and change into clean clothing.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a global health emergency. Our knowledge of this devastating virus is constantly evolving as we continue to fight this overwhelming disease. Theoretical risk of “viral” dissemination is considered extremely low, or negligible, during hysterosocopy. Hysteroscopic procedures in COVID-19–positive patients with life-threatening conditions or in patients in whom delaying the procedure could worsen outcomes should be performed taking appropriate measures. Patients who test negative for COVID-19 (confirmed by PCR) and require hysteroscopic procedures, should be treated using universal precautions. ●

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25:e936-e945.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. February 24, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843-1844.

- Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:793-798.

- Prem K, Liu Y, Russell TW, et al; Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e261-e270.

- American College of Surgeons, American Society of Aesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, American Hospital Association. Joint Statement: Roadmap for resuming elective surgery after COVID-19 pandemic. April 16, 2020. https://www.aorn.org/guidelines/aorn-support/roadmap-for-resuming-elective-surgery-after-covid-19. Accessed August 27, 2020.

- Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386-389.

- Mowbray NG, Ansell J, Horwood J, et al. Safe management of surgical smoke in the age of COVID-19. Br J Surg. May 3, 2020. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11679.

- Cohen SL, Liu G, Abrao M, et al. Perspectives on surgery in the time of COVID-19: safety first. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:792-793.

- COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:703-708.

- Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568-576.

- Aslan MM, Yuvaci HU, Köse O, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not present in the vaginal fluid of pregnant women with COVID-19. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:1-3. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1793318.

- Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:833-840.

- Prisant N, Bujan L, Benichou H, et al. Zika virus in the female genital tract. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1000-1001.

- Rodriguez LL, De Roo A, Guimard Y, et al. Persistence and genetic stability of Ebola virus during the outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999;179 Suppl 1:S170-S176.

- Qiu L, Liu X, Xiao M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not detectable in the vaginal fluid of women with severe COVID-19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:813-817.

- Brat GA, Hersey S, Chhabra K, et al. Protecting surgical teams during the COVID-19 outbreak: a narrative review and clinical considerations. Ann Surg. April 17, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003926.

- Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, et al. Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:857-863.

- Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e5-e6.

- Catena U. Surgical smoke in hysteroscopic surgery: does it really matter in COVID-19 times? Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2020;12:67-68.

- Carugno J, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Alonso L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic. Impact on hysteroscopic procedures: a consensus statement from the Global Congress of Hysteroscopy Scientific Committee. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:988-992.

The emergence of the coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) in December 2019, has resulted in a global pandemic that has challenged the medical community and will continue to represent a public health emergency for the next several months.1 It has rapidly spread globally, infecting many individuals in an unprecedented rate of infection and worldwide reach. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID-19 as a pandemic. While the majority of infected individuals are asymptomatic or develop only mild symptoms, some have an unfortunate clinical course resulting in multi-organ failure and death.2

It is accepted that the virus mainly spreads during close contact and via respiratory droplets.3 The average time from infection to onset of symptoms ranges from 2 to 14 days, with an average of 5 days.4 Recommended measures to prevent the spread of the infection include social distancing (at least 6 feet from others), meticulous hand hygiene, and wearing a mask covering the mouth and nose when in public.5 Aiming to mitigate the risk of viral dissemination for patients and health care providers, and to preserve hospital resources, all nonessential medical interventions were initially suspended. Recently, the American College of Surgeons in a joint statement with 9 women’s health care societies have provided recommendations on how to resume clinical activities as we recover from the pandemic.6

As we reinitiate clinical activities, gynecologists have been alerted of the potential risk of viral dissemination during gynecologic minimally invasive surgical procedures due to the presence of the virus in blood, stool, and the potential risk of aerosolization of the virus, especially when using smoke-generating devices.7,8 This risk is not limited to intubation and extubation of the airway during anesthesia; the risk also presents itself during other aerosol-generating procedures, such as laparoscopy or robotic surgery.9,10

Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard procedure for the diagnosis and management of intrauterine pathologies.11 It is frequently performed in an office setting without the use of anesthesia.11,12 It is usually well tolerated, with only a few patients reporting discomfort.12 It allows for immediate treatment (using the “see and treat” approach) while avoiding not only the risk of anesthesia, as stated, but also the need for intubation—which has a high risk of droplet contamination in COVID-19–infected individuals.13

Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures?

The novel and rapidly changing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic present many challenges to the gynecologist. Significant concerns have been raised regarding potential risk of viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery due to aerosolization of viral particles and the presence of the virus in blood and the gastrointestinal tract of infected patients.7 Diagnostic, and some simple, hysteroscopic procedures are commonly performed in an outpatient setting, with the patient awake. Complex hysteroscopic interventions, however, are generally performed in the operating room, typically with the use of general anesthesia. Hysteroscopy has the theoretical risks of viral dissemination when performed in COVID-19–positive patients. Two important questions must be addressed to better understand the potential risk of COVID-19 viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures.

Continue to: 1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?...

1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?

Recent studies have confirmed the presence of viral particles in urine, feces, blood, and tears in addition to the respiratory tract in patients infected with COVID-19.3,14,15 The presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the female genital system is currently unknown. Previous studies, of other epidemic viral infections, have demonstrated the presence of the virus in the female genital tract in affected patients of Zika virus and Ebola.16,17 However, 2 recent studies have failed to demonstrate the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the vaginal fluid of pregnant14 and not pregnant18 women with severe COVID-19 infection.

2. Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopy if using electrosurgery?

There are significant concerns with possible risk of COVID-19 transmission to health care providers in direct contact with infected patients during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures due to direct contamination and aerosolization of the virus.10,19 Current data on COVID-19 transmission during surgery are limited. However, it is important to recognize that viral aerosolization has been documented with other viral diseases, such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B.20 A recent report called for awareness in the surgical community about the potential risks of COVID-19 viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery. Among other recommendations, international experts advised minimizing the use of electrosurgery to reduce the creation of surgical plume, decreasing the pneumoperitoneum pressure to minimum levels, and using suction devices in a closed system.21 Although these preventive measures apply to laparoscopic surgery, it is important to consider that hysteroscopy is performed in a unique environment.

During hysteroscopy the uterine cavity is distended with a liquid medium (normal saline or electrolyte-free solutions); this is opposed to gynecologic laparoscopy, in which the peritoneal cavity is distended with carbon dioxide.22 The smoke produced with the use of hysteroscopic electrosurgical instruments generates bubbles that are immediately cooled down to the temperature of the distention media and subsequently dissolve into it. Therefore, there are no bubbles generated during hysteroscopic surgery that are subsequently released into the air. This results in a low risk for viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures. Nevertheless, the necessary precautions to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission during hysteroscopic intervention are extremely important.

Recommendations for hysteroscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic

We provide our overall recommendations for hysteroscopy, as well as those specific to the office and hospital setting.

Recommendations: General

Limit hysteroscopic procedures to COVID-19–negative patients and to those patients in whom delaying the procedure could result in adverse clinical outcomes.23

Universally screen for potential COVID-19 infection. When possible, a phone interview to triage patients based on their symptoms and infection exposure status should take place before the patient arrives to the health care center. Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection who require immediate evaluation should be directed to COVID-19–designated emergency areas.

Universally test for SARS-CoV-2 before procedures performed in the operating room (OR). Using nasopharyngeal swabs for the detection of viral RNA, employing molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), within 48 to 72 hours prior to all OR hysteroscopic procedures is strongly recommended. Adopting this testing strategy will aid to identify asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2‒infected patients, allowing to defer the procedure, if possible, among patients testing positive. If tests are limited, testing only patients scheduled for hysteroscopic procedures in which general or regional anesthesia will be required is acceptable.

Universal SARS-CoV-2 testing of patients undergoing in-office hysteroscopic diagnostic or minor operative procedures without the use of anesthesia is not required.

Limit the presence of a companion. It is understood that visitor policies may vary at the discretion of each institution’s guidelines. Children and individuals over the age of 60 years should not be granted access to the center. Companions will be subjected to the same screening criteria as patients.

Provide for social distancing and other precautionary measures. If more than one patient is scheduled to be at the facility at the same time, ensure that the facility provides adequate space to allow the appropriate social distancing recommendations between patients. Hand sanitizers and facemasks should be available for patients and companions.

Provide PPE for clinicians. All health care providers in close contact with the patient must wear personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes an apron and gown, a surgical mask, eye protection, and gloves. Health care providers should wear PPE deemed appropriate by their regulatory institutions following their local and national guidelines during clinical patient interactions.

Restrict surgical attendees to vital personnel. The participation of learners by physical presence in the office or operating room should be restricted.

Continue to: Recommendations: Office setting...

Recommendations: Office setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Advise patients to come to the office alone. If the patient requires a companion, a maximum of one adult companion under the age of 60 should be accepted.

- Limit the number of health care team members present in the procedure room.

Intraprocedural recommendations

- Choose the appropriate device(s) that will allow for an effective and fast procedure.

- Use the recommended PPE for all clinicians.

- Limit the movement of staff members in and out of the procedure room.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same procedure room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Allow for patients to recover from the procedure in the same room as the procedure took place in order to avoid potential contamination of multiple rooms.

- Expedite patient discharge.

- Follow up after the procedure by phone or telemedicine.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Continue to: Recommendations: Operating room setting...

Recommendations: Operating room setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Perform adequate patient screening for potential COVID-19 infection. (Screening should be independent of symptoms and not be limited to those with clinical symptoms.)

- Limit the number of health care team members in the operating procedure room.

- To minimize unnecessary staff exposure, have surgeons and staff not needed for intubation remain outside the OR until intubation is completed and leave the OR before extubation.

Intraprocedure recommendations

- Limit personnel in the OR to a minimum.

- Staff should not enter or leave the room during the procedure.

- When possible, use conscious sedation or regional anesthesia to avoid the risk of viral dissemination at the time of intubation/extubation.

- Choose the device that will allow an effective and fast procedure.

- Favor non–smoke-generating devices, such as hysteroscopic scissors, graspers, and tissue retrieval systems.

- Connect active suction to the outflow, especially when using smoke-generating instruments, to facilitate the extraction of surgical smoke.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Expedite postprocedure recovery and patient discharge.

- After completion of the procedure, staff should remove scrubs and change into clean clothing.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a global health emergency. Our knowledge of this devastating virus is constantly evolving as we continue to fight this overwhelming disease. Theoretical risk of “viral” dissemination is considered extremely low, or negligible, during hysterosocopy. Hysteroscopic procedures in COVID-19–positive patients with life-threatening conditions or in patients in whom delaying the procedure could worsen outcomes should be performed taking appropriate measures. Patients who test negative for COVID-19 (confirmed by PCR) and require hysteroscopic procedures, should be treated using universal precautions. ●

The emergence of the coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) in December 2019, has resulted in a global pandemic that has challenged the medical community and will continue to represent a public health emergency for the next several months.1 It has rapidly spread globally, infecting many individuals in an unprecedented rate of infection and worldwide reach. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID-19 as a pandemic. While the majority of infected individuals are asymptomatic or develop only mild symptoms, some have an unfortunate clinical course resulting in multi-organ failure and death.2

It is accepted that the virus mainly spreads during close contact and via respiratory droplets.3 The average time from infection to onset of symptoms ranges from 2 to 14 days, with an average of 5 days.4 Recommended measures to prevent the spread of the infection include social distancing (at least 6 feet from others), meticulous hand hygiene, and wearing a mask covering the mouth and nose when in public.5 Aiming to mitigate the risk of viral dissemination for patients and health care providers, and to preserve hospital resources, all nonessential medical interventions were initially suspended. Recently, the American College of Surgeons in a joint statement with 9 women’s health care societies have provided recommendations on how to resume clinical activities as we recover from the pandemic.6

As we reinitiate clinical activities, gynecologists have been alerted of the potential risk of viral dissemination during gynecologic minimally invasive surgical procedures due to the presence of the virus in blood, stool, and the potential risk of aerosolization of the virus, especially when using smoke-generating devices.7,8 This risk is not limited to intubation and extubation of the airway during anesthesia; the risk also presents itself during other aerosol-generating procedures, such as laparoscopy or robotic surgery.9,10

Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard procedure for the diagnosis and management of intrauterine pathologies.11 It is frequently performed in an office setting without the use of anesthesia.11,12 It is usually well tolerated, with only a few patients reporting discomfort.12 It allows for immediate treatment (using the “see and treat” approach) while avoiding not only the risk of anesthesia, as stated, but also the need for intubation—which has a high risk of droplet contamination in COVID-19–infected individuals.13

Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures?

The novel and rapidly changing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic present many challenges to the gynecologist. Significant concerns have been raised regarding potential risk of viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery due to aerosolization of viral particles and the presence of the virus in blood and the gastrointestinal tract of infected patients.7 Diagnostic, and some simple, hysteroscopic procedures are commonly performed in an outpatient setting, with the patient awake. Complex hysteroscopic interventions, however, are generally performed in the operating room, typically with the use of general anesthesia. Hysteroscopy has the theoretical risks of viral dissemination when performed in COVID-19–positive patients. Two important questions must be addressed to better understand the potential risk of COVID-19 viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures.

Continue to: 1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?...

1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?

Recent studies have confirmed the presence of viral particles in urine, feces, blood, and tears in addition to the respiratory tract in patients infected with COVID-19.3,14,15 The presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the female genital system is currently unknown. Previous studies, of other epidemic viral infections, have demonstrated the presence of the virus in the female genital tract in affected patients of Zika virus and Ebola.16,17 However, 2 recent studies have failed to demonstrate the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the vaginal fluid of pregnant14 and not pregnant18 women with severe COVID-19 infection.

2. Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopy if using electrosurgery?

There are significant concerns with possible risk of COVID-19 transmission to health care providers in direct contact with infected patients during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures due to direct contamination and aerosolization of the virus.10,19 Current data on COVID-19 transmission during surgery are limited. However, it is important to recognize that viral aerosolization has been documented with other viral diseases, such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B.20 A recent report called for awareness in the surgical community about the potential risks of COVID-19 viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery. Among other recommendations, international experts advised minimizing the use of electrosurgery to reduce the creation of surgical plume, decreasing the pneumoperitoneum pressure to minimum levels, and using suction devices in a closed system.21 Although these preventive measures apply to laparoscopic surgery, it is important to consider that hysteroscopy is performed in a unique environment.

During hysteroscopy the uterine cavity is distended with a liquid medium (normal saline or electrolyte-free solutions); this is opposed to gynecologic laparoscopy, in which the peritoneal cavity is distended with carbon dioxide.22 The smoke produced with the use of hysteroscopic electrosurgical instruments generates bubbles that are immediately cooled down to the temperature of the distention media and subsequently dissolve into it. Therefore, there are no bubbles generated during hysteroscopic surgery that are subsequently released into the air. This results in a low risk for viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures. Nevertheless, the necessary precautions to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission during hysteroscopic intervention are extremely important.

Recommendations for hysteroscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic

We provide our overall recommendations for hysteroscopy, as well as those specific to the office and hospital setting.

Recommendations: General

Limit hysteroscopic procedures to COVID-19–negative patients and to those patients in whom delaying the procedure could result in adverse clinical outcomes.23

Universally screen for potential COVID-19 infection. When possible, a phone interview to triage patients based on their symptoms and infection exposure status should take place before the patient arrives to the health care center. Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection who require immediate evaluation should be directed to COVID-19–designated emergency areas.

Universally test for SARS-CoV-2 before procedures performed in the operating room (OR). Using nasopharyngeal swabs for the detection of viral RNA, employing molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), within 48 to 72 hours prior to all OR hysteroscopic procedures is strongly recommended. Adopting this testing strategy will aid to identify asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2‒infected patients, allowing to defer the procedure, if possible, among patients testing positive. If tests are limited, testing only patients scheduled for hysteroscopic procedures in which general or regional anesthesia will be required is acceptable.

Universal SARS-CoV-2 testing of patients undergoing in-office hysteroscopic diagnostic or minor operative procedures without the use of anesthesia is not required.

Limit the presence of a companion. It is understood that visitor policies may vary at the discretion of each institution’s guidelines. Children and individuals over the age of 60 years should not be granted access to the center. Companions will be subjected to the same screening criteria as patients.

Provide for social distancing and other precautionary measures. If more than one patient is scheduled to be at the facility at the same time, ensure that the facility provides adequate space to allow the appropriate social distancing recommendations between patients. Hand sanitizers and facemasks should be available for patients and companions.

Provide PPE for clinicians. All health care providers in close contact with the patient must wear personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes an apron and gown, a surgical mask, eye protection, and gloves. Health care providers should wear PPE deemed appropriate by their regulatory institutions following their local and national guidelines during clinical patient interactions.

Restrict surgical attendees to vital personnel. The participation of learners by physical presence in the office or operating room should be restricted.

Continue to: Recommendations: Office setting...

Recommendations: Office setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Advise patients to come to the office alone. If the patient requires a companion, a maximum of one adult companion under the age of 60 should be accepted.

- Limit the number of health care team members present in the procedure room.

Intraprocedural recommendations

- Choose the appropriate device(s) that will allow for an effective and fast procedure.

- Use the recommended PPE for all clinicians.

- Limit the movement of staff members in and out of the procedure room.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same procedure room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Allow for patients to recover from the procedure in the same room as the procedure took place in order to avoid potential contamination of multiple rooms.

- Expedite patient discharge.

- Follow up after the procedure by phone or telemedicine.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Continue to: Recommendations: Operating room setting...

Recommendations: Operating room setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Perform adequate patient screening for potential COVID-19 infection. (Screening should be independent of symptoms and not be limited to those with clinical symptoms.)

- Limit the number of health care team members in the operating procedure room.

- To minimize unnecessary staff exposure, have surgeons and staff not needed for intubation remain outside the OR until intubation is completed and leave the OR before extubation.

Intraprocedure recommendations

- Limit personnel in the OR to a minimum.

- Staff should not enter or leave the room during the procedure.

- When possible, use conscious sedation or regional anesthesia to avoid the risk of viral dissemination at the time of intubation/extubation.

- Choose the device that will allow an effective and fast procedure.

- Favor non–smoke-generating devices, such as hysteroscopic scissors, graspers, and tissue retrieval systems.

- Connect active suction to the outflow, especially when using smoke-generating instruments, to facilitate the extraction of surgical smoke.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Expedite postprocedure recovery and patient discharge.

- After completion of the procedure, staff should remove scrubs and change into clean clothing.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a global health emergency. Our knowledge of this devastating virus is constantly evolving as we continue to fight this overwhelming disease. Theoretical risk of “viral” dissemination is considered extremely low, or negligible, during hysterosocopy. Hysteroscopic procedures in COVID-19–positive patients with life-threatening conditions or in patients in whom delaying the procedure could worsen outcomes should be performed taking appropriate measures. Patients who test negative for COVID-19 (confirmed by PCR) and require hysteroscopic procedures, should be treated using universal precautions. ●

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25:e936-e945.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. February 24, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843-1844.

- Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:793-798.

- Prem K, Liu Y, Russell TW, et al; Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e261-e270.

- American College of Surgeons, American Society of Aesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, American Hospital Association. Joint Statement: Roadmap for resuming elective surgery after COVID-19 pandemic. April 16, 2020. https://www.aorn.org/guidelines/aorn-support/roadmap-for-resuming-elective-surgery-after-covid-19. Accessed August 27, 2020.

- Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386-389.

- Mowbray NG, Ansell J, Horwood J, et al. Safe management of surgical smoke in the age of COVID-19. Br J Surg. May 3, 2020. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11679.

- Cohen SL, Liu G, Abrao M, et al. Perspectives on surgery in the time of COVID-19: safety first. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:792-793.

- COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:703-708.

- Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568-576.

- Aslan MM, Yuvaci HU, Köse O, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not present in the vaginal fluid of pregnant women with COVID-19. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:1-3. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1793318.

- Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:833-840.

- Prisant N, Bujan L, Benichou H, et al. Zika virus in the female genital tract. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1000-1001.

- Rodriguez LL, De Roo A, Guimard Y, et al. Persistence and genetic stability of Ebola virus during the outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999;179 Suppl 1:S170-S176.

- Qiu L, Liu X, Xiao M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not detectable in the vaginal fluid of women with severe COVID-19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:813-817.

- Brat GA, Hersey S, Chhabra K, et al. Protecting surgical teams during the COVID-19 outbreak: a narrative review and clinical considerations. Ann Surg. April 17, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003926.

- Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, et al. Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:857-863.

- Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e5-e6.

- Catena U. Surgical smoke in hysteroscopic surgery: does it really matter in COVID-19 times? Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2020;12:67-68.

- Carugno J, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Alonso L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic. Impact on hysteroscopic procedures: a consensus statement from the Global Congress of Hysteroscopy Scientific Committee. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:988-992.

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25:e936-e945.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. February 24, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843-1844.

- Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:793-798.

- Prem K, Liu Y, Russell TW, et al; Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e261-e270.

- American College of Surgeons, American Society of Aesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, American Hospital Association. Joint Statement: Roadmap for resuming elective surgery after COVID-19 pandemic. April 16, 2020. https://www.aorn.org/guidelines/aorn-support/roadmap-for-resuming-elective-surgery-after-covid-19. Accessed August 27, 2020.

- Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386-389.

- Mowbray NG, Ansell J, Horwood J, et al. Safe management of surgical smoke in the age of COVID-19. Br J Surg. May 3, 2020. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11679.

- Cohen SL, Liu G, Abrao M, et al. Perspectives on surgery in the time of COVID-19: safety first. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:792-793.

- COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:703-708.

- Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568-576.

- Aslan MM, Yuvaci HU, Köse O, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not present in the vaginal fluid of pregnant women with COVID-19. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:1-3. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1793318.

- Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:833-840.

- Prisant N, Bujan L, Benichou H, et al. Zika virus in the female genital tract. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1000-1001.

- Rodriguez LL, De Roo A, Guimard Y, et al. Persistence and genetic stability of Ebola virus during the outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999;179 Suppl 1:S170-S176.

- Qiu L, Liu X, Xiao M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not detectable in the vaginal fluid of women with severe COVID-19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:813-817.

- Brat GA, Hersey S, Chhabra K, et al. Protecting surgical teams during the COVID-19 outbreak: a narrative review and clinical considerations. Ann Surg. April 17, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003926.

- Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, et al. Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:857-863.

- Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e5-e6.

- Catena U. Surgical smoke in hysteroscopic surgery: does it really matter in COVID-19 times? Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2020;12:67-68.

- Carugno J, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Alonso L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic. Impact on hysteroscopic procedures: a consensus statement from the Global Congress of Hysteroscopy Scientific Committee. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:988-992.

Isthmocele repair: Simultaneous hysteroscopy and robotic-assisted laparoscopy

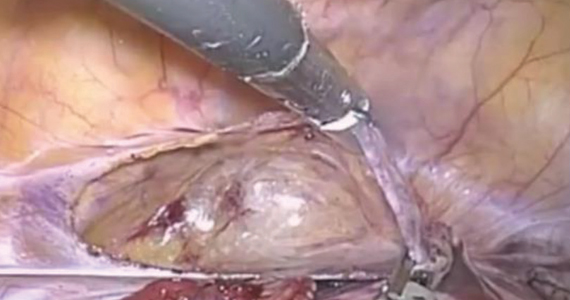

An isthmocele is a pouch-like anterior uterine wall defect at the site of a previous cesarean scar. The incidence is not well known, but it is estimated in the literature to be between 19% and 88%.1 Issues arising from an isthmocele may include abnormal uterine bleeding; abdominal pain; diminished fertility; ectopic pregnancy; or obstetric complications, such as uterine rupture. Repair of an isthmocele may be indicated for symptomatic relief and preservation of fertility. Multiple surgical approaches have been described in the literature, including laparoscopic, hysteroscopic, and vaginal approaches.

The objective of this video is to illustrate the use of robotic-assisted laparoscopy with simultaneous hysteroscopy as a feasible and safe approach for the repair of an isthmocele. Here we illustrate the key surgical steps of this approach, including:

- presurgical planning with magnetic resonance imaging

- diagnostic hysteroscopy for confirmation of isthmocele

- simultaneous laparoscopy for identification of borders

- strategic hysterotomy

- excision of scar tissue

- imbricated, tension-free closure.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

- Tower AM, Frishman GN. Cesarean scar defects: an underrecognized cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:562-572. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.03.008.

An isthmocele is a pouch-like anterior uterine wall defect at the site of a previous cesarean scar. The incidence is not well known, but it is estimated in the literature to be between 19% and 88%.1 Issues arising from an isthmocele may include abnormal uterine bleeding; abdominal pain; diminished fertility; ectopic pregnancy; or obstetric complications, such as uterine rupture. Repair of an isthmocele may be indicated for symptomatic relief and preservation of fertility. Multiple surgical approaches have been described in the literature, including laparoscopic, hysteroscopic, and vaginal approaches.

The objective of this video is to illustrate the use of robotic-assisted laparoscopy with simultaneous hysteroscopy as a feasible and safe approach for the repair of an isthmocele. Here we illustrate the key surgical steps of this approach, including:

- presurgical planning with magnetic resonance imaging

- diagnostic hysteroscopy for confirmation of isthmocele

- simultaneous laparoscopy for identification of borders

- strategic hysterotomy

- excision of scar tissue

- imbricated, tension-free closure.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

An isthmocele is a pouch-like anterior uterine wall defect at the site of a previous cesarean scar. The incidence is not well known, but it is estimated in the literature to be between 19% and 88%.1 Issues arising from an isthmocele may include abnormal uterine bleeding; abdominal pain; diminished fertility; ectopic pregnancy; or obstetric complications, such as uterine rupture. Repair of an isthmocele may be indicated for symptomatic relief and preservation of fertility. Multiple surgical approaches have been described in the literature, including laparoscopic, hysteroscopic, and vaginal approaches.

The objective of this video is to illustrate the use of robotic-assisted laparoscopy with simultaneous hysteroscopy as a feasible and safe approach for the repair of an isthmocele. Here we illustrate the key surgical steps of this approach, including:

- presurgical planning with magnetic resonance imaging

- diagnostic hysteroscopy for confirmation of isthmocele

- simultaneous laparoscopy for identification of borders

- strategic hysterotomy

- excision of scar tissue

- imbricated, tension-free closure.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

- Tower AM, Frishman GN. Cesarean scar defects: an underrecognized cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:562-572. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.03.008.

- Tower AM, Frishman GN. Cesarean scar defects: an underrecognized cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and other gynecologic complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:562-572. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.03.008.

How to perform a vulvar biopsy

Many benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions can occur on the vulva. These can be challenging to differentiate by examination alone. A vulvar biopsy often is needed to appropriately diagnose—and ultimately treat—these various conditions.

In this article, we review vulvar biopsy procedures, describe how to prepare tissue specimens for the pathologist, and provide some brief case examples in which biopsy established the diagnosis.

Ask questions first

Prior to examining a patient with a vulvar lesion, obtain a detailed history. Asking specific questions may aid in making the correct diagnosis, such as:

- How long has the lesion been present? Has it changed? What color is it?

- Was any trigger, or trauma, associated with onset of the lesion?

- Does the lesion itch, burn, or cause pain? Is there any associated bleeding or discharge?

- Are other lesions present in the vagina, anus, or mouth, or are other skin lesions present?

- Are any systemic symptoms present, such as fever, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, or joint pain?

- What is the patient’s previous treatment history, including over-the-counter medications and prescribed medications?

- Has there been any incontinence of urine or stool? Does the patient use a pad?

- Is the patient scratching? Is there any nighttime scratching? It also can be useful to ask her partner, if she has one, about nighttime scratching.

- Is there a family history of vulvar conditions?

- Has there been any change in her use of products like soap, lotions, cleansing wipes, sprays, lubricants, or laundry detergent?

- Has the patient had any new partners or significant travel history?

Preprocedure counseling points

Prior to proceeding with a vulvar biopsy, review with the patient the risks, benefits, and alternatives and obtain patient consent for the procedure. Vulvar biopsy risks include pain, bleeding, infection, injury to surrounding tissue, and the need for further surgery. Make patients aware that some biopsies are nondiagnostic. We recommend that clinicians perform a time-out verification to ensure that the patient’s identity and planned procedure are correct.

Assess the biopsy site

A wide variety of lesions may require a biopsy for diagnosis. While it can be challenging to know where to biopsy, taking the time to determine the proper biopsy site may enhance pathology results.

When considering colored lesions, depth is the important factor, and a punch biopsy often is sufficient. A tumor should be biopsied in the thickest area. Lesions that are concerning for malignancy may require multiple biopsies. An erosion or ulcer is best biopsied on the edge, including a small amount of surrounding tissue. For most patients, biopsy of normal-appearing tissue is of low diagnostic yield. Lastly, we try to avoid biopsies directly on the midline to facilitate better healing.1

A photograph of the vulva prior to biopsy may be helpful for the pathologist to see the tissue. Some electronic medical records have the capability to include photographs. Due to the sensitive nature of these photographs, we prefer that a separate written patient consent be obtained prior to taking photographs. We find also that photos are a useful reference for progression of disease at follow-up in a shared care team.

Continue to: Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit...

Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit

Some patients may benefit from the application of topical lidocaine 4% cream (L.M.X.4) prior to the injection of a local anesthetic for tissue biopsy. Ideally, topical lidocaine should be placed on the vulva and covered with a dressing such as Tegaderm or cellophane up to 30 minutes before the anticipated biopsy procedure. The anesthetic effect generally lasts for about 60 minutes. Many patients report stinging for several seconds upon application. Due to clinic time restrictions, we tend to reserve this method for a limited subset of patients. If planning a return visit for a biopsy, the patient can place the topical anesthetic herself.

For the anesthetic injection, we recommend lidocaine 1% or 2% with epinephrine in all areas of the vulva except for the glans clitoris. For a punch biopsy, we draw up 1 to 3 mL in a 3-mL syringe and inject with a 21- to 30-gauge needle, using a lower gauge for thicker tissue. We have not found buffering the anesthetic with sodium bicarbonate to be of particular use. For the glans clitoris, lidocaine without epinephrine should be utilized.

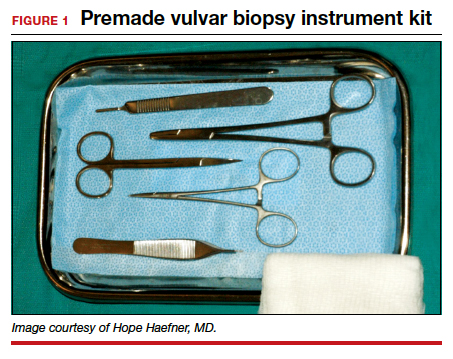

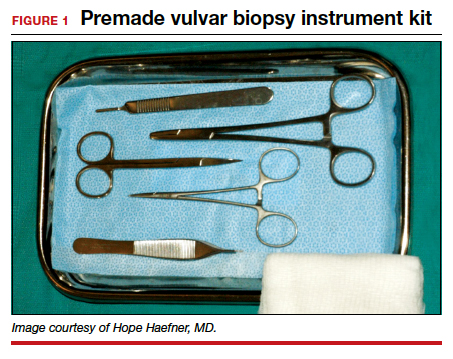

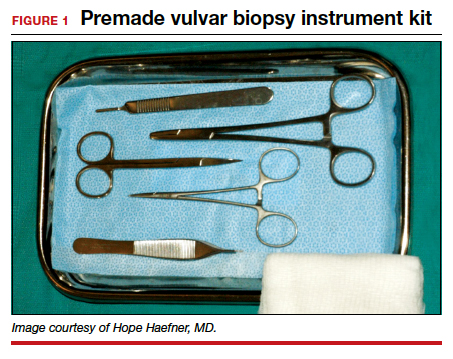

Equipment. Depending on your office setting, having a premade instrument kit may be preferred to peel-pack equipment. We prefer a premade tray that contains sterile gauze, a hemostat, iris scissors, a needle driver, a scalpel handle, and Adson forceps (FIGURE 1).

Types of biopsy procedures

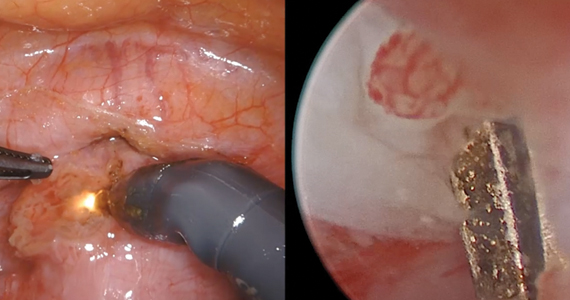

Punch biopsy. We recommend a 4-mm Keyes biopsy punch. As mentioned, we use a biopsy kit to facilitate the procedure. After the tissue is properly anesthetized and prepped, we test the area via gentle touch to the skin with the hemostat or Adson forceps. To perform the punch biopsy, gentle, consistent pressure in a clockwise-counterclockwise fashion yields the best results. The goal is to obtain a 5-mm depth for hair-bearing skin and a 3-mm depth for all other tissue.2 The tissue should then be excised at the base with scissors, taking care not to crush the specimen with forceps.

Punch biopsy permits sampling of the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Hemostasis is maintained with either silver nitrate, Monsel’s solution (ferric sulfate), or a dissolvable suture such as 4-0 Monocryl (poliglecaprone 25) or Vicryl Rapide (polyglactin 910).

Stitch biopsy. We find the stitch biopsy to be very useful given the architecture of the vulva. A modification of the shave biopsy, the stitch biopsy is depicted in FIGURE 2. A 3-0 or 4-0 dissolvable suture is placed through the intended area of biopsy. Iris scissors are used to undermine the tissue while the suture is held on tension. The goal is to remove the suture with the specimen. Separate sutures are used for hemostasis. The stitch does not cause the crushing artifacts on prepared specimens. Depending on the proceduralist’s comfort, a relatively large sample can be obtained in this fashion. If the suture held on tension is inadvertently cut, a second pass can be made with suture; alternatively, care can be used to remove remaining tissue with forceps and scissors, again avoiding crush injury to the tissue.

Excisional biopsy. Often, a larger area or margins are desired. We find that with adequate preparation, patients tolerate excisions in the office quite well. The planned area for excision can be marked with ink to ensure margins. Adequate anesthesia is instilled. A No. 15 blade scalpel is often the best size used to excise vulvar tissue in an elliptical fashion. Depending on depth of incision, the tissue may need to be approximated in layers for cosmesis and healing.

When planning an excisional biopsy, place a stitch on the excised tissue to mark orientation or pin out the entire specimen to a foam board to help your pathologist interpret tissue orientation.

The box "Vulvar biopsy established the diagnosis" at the end of this discussion provides 6 case examples of vulvar lesions and the respective diagnoses confirmed by biopsy.

Continue to: Preparing tissue for the pathologist...

Preparing tissue for the pathologist

Here are 5 tips for preparing the biopsied specimen for pathology:

- Include a question for the pathologist, such as “rule out lichen sclerosus or lichen simplex chronicus.” The majority of specimens should be sent in formalin. At times, frozen sections are done in the operating room.

- Double-check that the proper paperwork is included with every specimen and be very specific regarding the exact location of the lesion on the vulva. Include photographs whenever possible.

- Request that a dermatopathologist or a gynecologic pathologist with a special interest in vulvar dermatology, when feasible, review the tissue.

- Check your laboratory’s protocol for sending biopsies from areas around ulcerated tissue. Often, special medium is required for immunohistochemistry stains.

- Call your pathologist with questions about results; he or she often is happy to clarify, and together you may be able to arrive at a diagnosis to better serve your patient.3

Complications and how to avoid them

Bleeding. Any procedure has bleeding risks. To avoid bleeding, review the patient’s medication list and medical history prior to biopsy, as certain medications, such as blood thinners, increase risk for bleeding. Counseling a patient on applying direct pressure to the biopsy site for 2 minutes is generally sufficient for any bleeding that may occur once she is discharged from the clinic.

Infection. With aseptic technique, infection of a biopsy site is rare. We use nonsterile gloves for biopsy procedures. This does not increase the risk of infection.4 If a patient has iodine allergy, dilute chlorhexidine is a reasonable alternative for skin cleansing. Instruct the patient to keep the site clean and dry; if the biopsy proximity is close to the urethra or anus, use of a peri-bottle may be preferred after toileting. Instruct patients not to pull sutures. While instructions are specific for each patient, we generally advise that patients wait 4 to 7 days before resuming use of topical medications.

Scarring or tattooing. Avoid using dyed suture on skin surfaces and counsel the patient that silver nitrate can permanently stain tissue. Usually, small biopsies heal well but a small scar is possible.

Key points to keep in mind

- Counsel patients on biopsy risks, benefits, and alternatives. Counsel regarding possible inconclusive results.

- Take time in choosing the biopsy site and consider multiple biopsies.

- Have all anticipated equipment available; consider using premade biopsy kits.

- Consider performing a stitch biopsy to avoid crush injury.

- Take photographs of the area to be biopsied and communicate with your pathologist to facilitate diagnosis.

Case 1

Biopsies were obtained of the areas highlighted in the photo. Pathology shows dVIN.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 2

The examination is consistent with condylomata acuminata and biopsy is recommended with a 4-mm punch. Biopsy results are consistent with condylomata acuminata.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 3

The final pathology shows high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 4

This presentation is an excellent opportunity for an excisional biopsy of the vulva. A marking pen is used to draw margins. A No. 15 blade is used to outline and then undermine the lesion, removing it in its entirety.

Final pathology shows a compound nevus of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 5

A 4-mm punch biopsy result is consistent with a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 6

A 4-mm punch biopsy result reveals that the pathology is significant for squamous cell carcinoma.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

- Edwards L, Lynch PJ. Genital Dermatology Atlas and Manual. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 93: Diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1243-1253.

- Heller DS. Areas of confusion in pathologist-clinician communication as it relates to understanding the vulvar pathology report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017;21:327-328.

- Rietz A, Barzin A, Jones K, et al. Sterile or non-sterile gloves for minor skin excisions? J Fam Pract. 2015;64:723-727.

Many benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions can occur on the vulva. These can be challenging to differentiate by examination alone. A vulvar biopsy often is needed to appropriately diagnose—and ultimately treat—these various conditions.

In this article, we review vulvar biopsy procedures, describe how to prepare tissue specimens for the pathologist, and provide some brief case examples in which biopsy established the diagnosis.

Ask questions first

Prior to examining a patient with a vulvar lesion, obtain a detailed history. Asking specific questions may aid in making the correct diagnosis, such as:

- How long has the lesion been present? Has it changed? What color is it?

- Was any trigger, or trauma, associated with onset of the lesion?

- Does the lesion itch, burn, or cause pain? Is there any associated bleeding or discharge?

- Are other lesions present in the vagina, anus, or mouth, or are other skin lesions present?

- Are any systemic symptoms present, such as fever, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, or joint pain?

- What is the patient’s previous treatment history, including over-the-counter medications and prescribed medications?

- Has there been any incontinence of urine or stool? Does the patient use a pad?

- Is the patient scratching? Is there any nighttime scratching? It also can be useful to ask her partner, if she has one, about nighttime scratching.

- Is there a family history of vulvar conditions?

- Has there been any change in her use of products like soap, lotions, cleansing wipes, sprays, lubricants, or laundry detergent?

- Has the patient had any new partners or significant travel history?

Preprocedure counseling points

Prior to proceeding with a vulvar biopsy, review with the patient the risks, benefits, and alternatives and obtain patient consent for the procedure. Vulvar biopsy risks include pain, bleeding, infection, injury to surrounding tissue, and the need for further surgery. Make patients aware that some biopsies are nondiagnostic. We recommend that clinicians perform a time-out verification to ensure that the patient’s identity and planned procedure are correct.

Assess the biopsy site

A wide variety of lesions may require a biopsy for diagnosis. While it can be challenging to know where to biopsy, taking the time to determine the proper biopsy site may enhance pathology results.

When considering colored lesions, depth is the important factor, and a punch biopsy often is sufficient. A tumor should be biopsied in the thickest area. Lesions that are concerning for malignancy may require multiple biopsies. An erosion or ulcer is best biopsied on the edge, including a small amount of surrounding tissue. For most patients, biopsy of normal-appearing tissue is of low diagnostic yield. Lastly, we try to avoid biopsies directly on the midline to facilitate better healing.1

A photograph of the vulva prior to biopsy may be helpful for the pathologist to see the tissue. Some electronic medical records have the capability to include photographs. Due to the sensitive nature of these photographs, we prefer that a separate written patient consent be obtained prior to taking photographs. We find also that photos are a useful reference for progression of disease at follow-up in a shared care team.

Continue to: Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit...

Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit

Some patients may benefit from the application of topical lidocaine 4% cream (L.M.X.4) prior to the injection of a local anesthetic for tissue biopsy. Ideally, topical lidocaine should be placed on the vulva and covered with a dressing such as Tegaderm or cellophane up to 30 minutes before the anticipated biopsy procedure. The anesthetic effect generally lasts for about 60 minutes. Many patients report stinging for several seconds upon application. Due to clinic time restrictions, we tend to reserve this method for a limited subset of patients. If planning a return visit for a biopsy, the patient can place the topical anesthetic herself.

For the anesthetic injection, we recommend lidocaine 1% or 2% with epinephrine in all areas of the vulva except for the glans clitoris. For a punch biopsy, we draw up 1 to 3 mL in a 3-mL syringe and inject with a 21- to 30-gauge needle, using a lower gauge for thicker tissue. We have not found buffering the anesthetic with sodium bicarbonate to be of particular use. For the glans clitoris, lidocaine without epinephrine should be utilized.

Equipment. Depending on your office setting, having a premade instrument kit may be preferred to peel-pack equipment. We prefer a premade tray that contains sterile gauze, a hemostat, iris scissors, a needle driver, a scalpel handle, and Adson forceps (FIGURE 1).

Types of biopsy procedures

Punch biopsy. We recommend a 4-mm Keyes biopsy punch. As mentioned, we use a biopsy kit to facilitate the procedure. After the tissue is properly anesthetized and prepped, we test the area via gentle touch to the skin with the hemostat or Adson forceps. To perform the punch biopsy, gentle, consistent pressure in a clockwise-counterclockwise fashion yields the best results. The goal is to obtain a 5-mm depth for hair-bearing skin and a 3-mm depth for all other tissue.2 The tissue should then be excised at the base with scissors, taking care not to crush the specimen with forceps.

Punch biopsy permits sampling of the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Hemostasis is maintained with either silver nitrate, Monsel’s solution (ferric sulfate), or a dissolvable suture such as 4-0 Monocryl (poliglecaprone 25) or Vicryl Rapide (polyglactin 910).

Stitch biopsy. We find the stitch biopsy to be very useful given the architecture of the vulva. A modification of the shave biopsy, the stitch biopsy is depicted in FIGURE 2. A 3-0 or 4-0 dissolvable suture is placed through the intended area of biopsy. Iris scissors are used to undermine the tissue while the suture is held on tension. The goal is to remove the suture with the specimen. Separate sutures are used for hemostasis. The stitch does not cause the crushing artifacts on prepared specimens. Depending on the proceduralist’s comfort, a relatively large sample can be obtained in this fashion. If the suture held on tension is inadvertently cut, a second pass can be made with suture; alternatively, care can be used to remove remaining tissue with forceps and scissors, again avoiding crush injury to the tissue.

Excisional biopsy. Often, a larger area or margins are desired. We find that with adequate preparation, patients tolerate excisions in the office quite well. The planned area for excision can be marked with ink to ensure margins. Adequate anesthesia is instilled. A No. 15 blade scalpel is often the best size used to excise vulvar tissue in an elliptical fashion. Depending on depth of incision, the tissue may need to be approximated in layers for cosmesis and healing.

When planning an excisional biopsy, place a stitch on the excised tissue to mark orientation or pin out the entire specimen to a foam board to help your pathologist interpret tissue orientation.

The box "Vulvar biopsy established the diagnosis" at the end of this discussion provides 6 case examples of vulvar lesions and the respective diagnoses confirmed by biopsy.

Continue to: Preparing tissue for the pathologist...

Preparing tissue for the pathologist

Here are 5 tips for preparing the biopsied specimen for pathology:

- Include a question for the pathologist, such as “rule out lichen sclerosus or lichen simplex chronicus.” The majority of specimens should be sent in formalin. At times, frozen sections are done in the operating room.

- Double-check that the proper paperwork is included with every specimen and be very specific regarding the exact location of the lesion on the vulva. Include photographs whenever possible.

- Request that a dermatopathologist or a gynecologic pathologist with a special interest in vulvar dermatology, when feasible, review the tissue.

- Check your laboratory’s protocol for sending biopsies from areas around ulcerated tissue. Often, special medium is required for immunohistochemistry stains.

- Call your pathologist with questions about results; he or she often is happy to clarify, and together you may be able to arrive at a diagnosis to better serve your patient.3

Complications and how to avoid them

Bleeding. Any procedure has bleeding risks. To avoid bleeding, review the patient’s medication list and medical history prior to biopsy, as certain medications, such as blood thinners, increase risk for bleeding. Counseling a patient on applying direct pressure to the biopsy site for 2 minutes is generally sufficient for any bleeding that may occur once she is discharged from the clinic.

Infection. With aseptic technique, infection of a biopsy site is rare. We use nonsterile gloves for biopsy procedures. This does not increase the risk of infection.4 If a patient has iodine allergy, dilute chlorhexidine is a reasonable alternative for skin cleansing. Instruct the patient to keep the site clean and dry; if the biopsy proximity is close to the urethra or anus, use of a peri-bottle may be preferred after toileting. Instruct patients not to pull sutures. While instructions are specific for each patient, we generally advise that patients wait 4 to 7 days before resuming use of topical medications.

Scarring or tattooing. Avoid using dyed suture on skin surfaces and counsel the patient that silver nitrate can permanently stain tissue. Usually, small biopsies heal well but a small scar is possible.

Key points to keep in mind

- Counsel patients on biopsy risks, benefits, and alternatives. Counsel regarding possible inconclusive results.

- Take time in choosing the biopsy site and consider multiple biopsies.

- Have all anticipated equipment available; consider using premade biopsy kits.

- Consider performing a stitch biopsy to avoid crush injury.

- Take photographs of the area to be biopsied and communicate with your pathologist to facilitate diagnosis.

Case 1

Biopsies were obtained of the areas highlighted in the photo. Pathology shows dVIN.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 2

The examination is consistent with condylomata acuminata and biopsy is recommended with a 4-mm punch. Biopsy results are consistent with condylomata acuminata.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 3

The final pathology shows high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 4

This presentation is an excellent opportunity for an excisional biopsy of the vulva. A marking pen is used to draw margins. A No. 15 blade is used to outline and then undermine the lesion, removing it in its entirety.

Final pathology shows a compound nevus of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 5

A 4-mm punch biopsy result is consistent with a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 6

A 4-mm punch biopsy result reveals that the pathology is significant for squamous cell carcinoma.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Many benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions can occur on the vulva. These can be challenging to differentiate by examination alone. A vulvar biopsy often is needed to appropriately diagnose—and ultimately treat—these various conditions.

In this article, we review vulvar biopsy procedures, describe how to prepare tissue specimens for the pathologist, and provide some brief case examples in which biopsy established the diagnosis.

Ask questions first

Prior to examining a patient with a vulvar lesion, obtain a detailed history. Asking specific questions may aid in making the correct diagnosis, such as:

- How long has the lesion been present? Has it changed? What color is it?

- Was any trigger, or trauma, associated with onset of the lesion?

- Does the lesion itch, burn, or cause pain? Is there any associated bleeding or discharge?

- Are other lesions present in the vagina, anus, or mouth, or are other skin lesions present?

- Are any systemic symptoms present, such as fever, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, or joint pain?

- What is the patient’s previous treatment history, including over-the-counter medications and prescribed medications?

- Has there been any incontinence of urine or stool? Does the patient use a pad?