User login

Potential dapagliflozin benefit post MI is not a ‘mandate’

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

PHILADELPHIA – Giving the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) to patients with acute myocardial infarction and impaired left ventricular systolic function but no diabetes or chronic heart failure significantly improved a composite of cardiovascular outcomes, a European registry-based randomized trial suggests.

In presenting these results from the DAPA-MI trial, Stefan James, MD, of Uppsala University (Sweden), noted that which the trial described as the hierarchical “win ratio” composite outcomes, compared with patients randomized to placebo plus standard of care.

“The ‘win ratio’ tells us that there’s a 34% higher likelihood of patients having a better cardiometabolic outcome with dapagliflozin vs placebo in terms of the seven components,” James said in an interview. The win ratio was achieved in 32.9% of dapagliflozin patients versus 24.6% of placebo (P < .001).

Dr. James presented the results at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and they were published online simultaneously in NEJM Evidence.

Lower-risk patients

DAPA-MI enrolled 4,017 patients from the SWEDEHEART and Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries in Sweden and the United Kingdom, randomly assigning patients to dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo along with guideline-directed therapy for both groups.

Eligible patients were hemodynamically stable, had an acute MI within 10 days of enrollment, and impaired left ventricular systolic function or a Q-wave MI. Exclusion criteria included history of either type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic heart failure, poor kidney function, or current treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between trial arms.

- The hierarchical seven primary endpoints were:

- Death, with cardiovascular death ranked first followed by noncardiovascular death

- Hospitalization because of heart failure, with adjudicated first followed by investigator-reported HF

- Nonfatal MI

- Atrial fibrillation/flutter event

- New diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- New York Heart Association functional class at the last visit

- Drop in body weight of at least 5% at the last visit

The key secondary endpoint, Dr. James said, was the primary outcome minus the body weight component, with time to first occurrence of hospitalization for HF or cardiovascular death.

When the seventh factor, body weight decrease, was removed, the differential narrowed: 20.3% versus 16.9% (P = .015). When two or more variables were removed from the composite, the differences were not statistically significant.

For 11 secondary and exploratory outcomes, ranging from CV death or hospitalization for HF to all-cause hospitalization, the outcomes were similar in both the dapagliflozin and placebo groups across the board.

However, the dapagliflozin patients had about half the rate of developing diabetes, compared with the placebo group: 2.1 % versus 3.9%.

The trial initially used the composite of CV death and hospitalization for HF as the primary endpoint, but switched to the seven-item composite endpoint in February because the number of primary composite outcomes was substantially lower than anticipated, Dr. James said.

He acknowledged the study was underpowered for the low-risk population it enrolled. “But if you extended the trial to a larger population and enriched it with a higher-risk population you would probably see an effect,” he said.

“The cardiometabolic benefit was consistent across all prespecified subgroups and there were no new safety concerns,” Dr. James told the attendees. “Clinical event rates were low with no significant difference between randomized groups.”

Not a ringing endorsement

But for invited discussant Stephen D. Wiviott, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, the DAPA-MI trial result isn’t quite a ringing endorsement of SGLT2 inhibition in these patients.

“From my perspective, DAPA-MI does not suggest a new mandate to expand SGLT2 inhibition to an isolated MI population without other SGLT2 inhibitor indications,” Dr. Wiviott told attendees. “But it does support the safety of its use among patients with acute coronary syndromes.”

However, “these results do not indicate a lack of clinical benefit in patients with prior MI and any of those previously identified conditions – a history of diabetes, coronary heart failure or chronic kidney disease – where SGLT2 inhibition remains a pillar of guideline-directed medical therapy,” Dr. Wiviott said.

In an interview, Dr. Wiviott described the trial design as a “hybrid” in that it used a registry but then added, in his words, “some of the bells and whistles that we have with normal cardiovascular clinical trials.” He further explained: “This is a nice combination of those two things, where they use that as part of the endpoint for the trial but they’re able to add in some of the pieces that you would in a regular registration pathway trial.”

The trial design could serve as a model for future pragmatic therapeutic trials in acute MI, he said, but he acknowledged that DAPA-MI was underpowered to discern many key outcomes.

“They anticipated they were going to have a rate of around 11% of events so they needed to enroll about 6,000 people, but somewhere in the middle of the trial they saw the rate was 2.5%, not 11%, so they had to completely change the trial,” he said of the DAPA-MI investigators.

But an appropriately powered study of SGLT2 inhibition in this population would need about 28,000 patients. “This would be an enormous trial to actually clinically power, so in my sense it’s not going to happen,” Dr. Wiviott said.

The DAPA-MI trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. James disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Amgen. Dr. Wiviott disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Icon Clinical, Novo Nordisk, and Varian.

AT AHA 2023

In MI with anemia, results may favor liberal transfusion: MINT

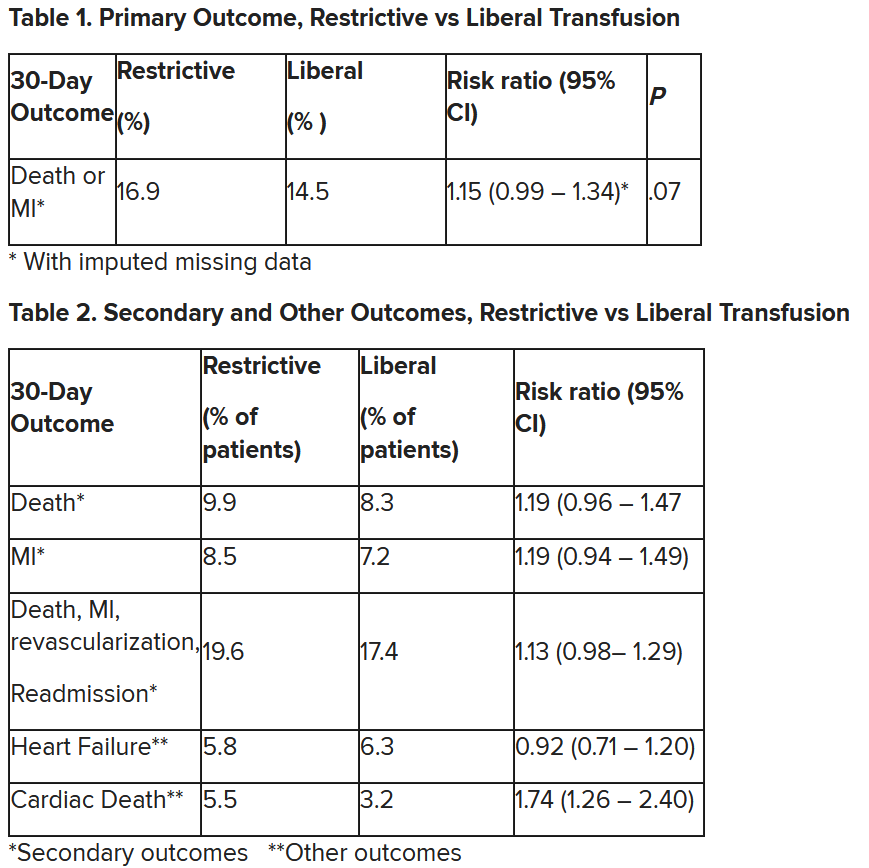

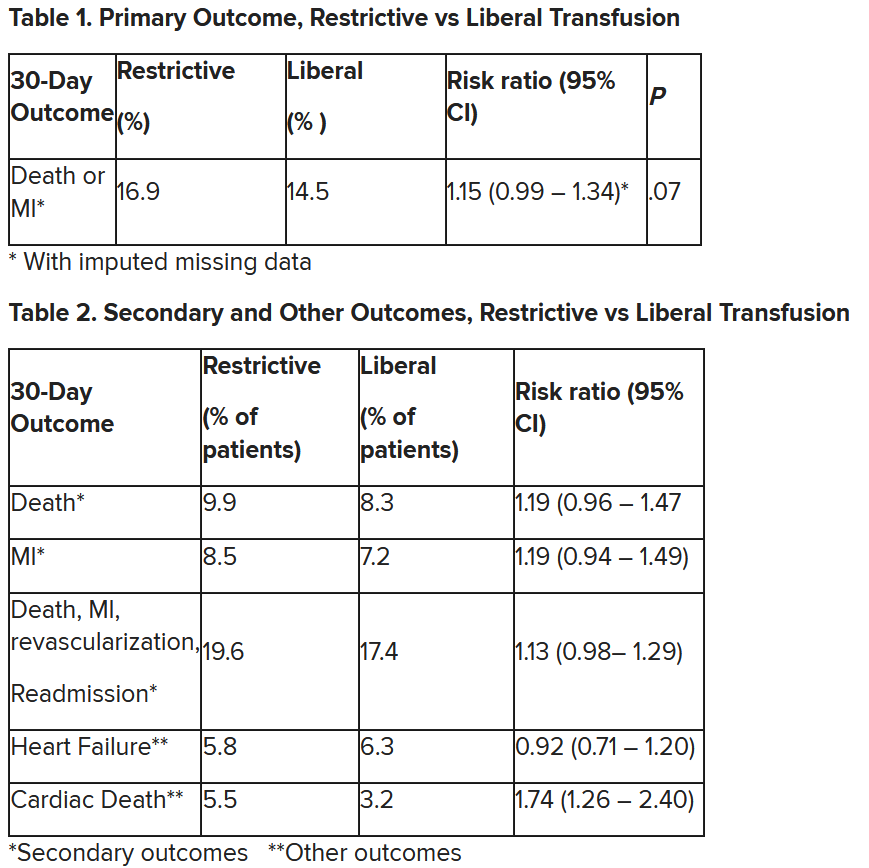

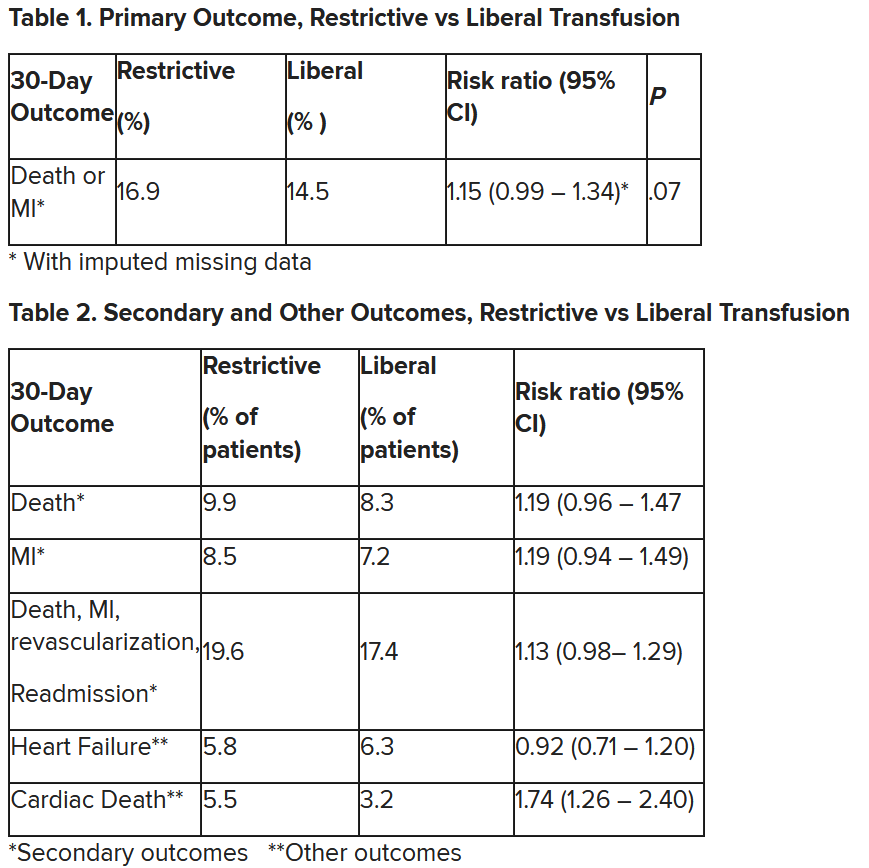

In patients with myocardial infarction and anemia, a “liberal” red blood cell transfusion strategy did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent MI or death within 30 days, compared with a “restrictive” transfusion strategy, in the 3,500-patient MINT trial.

Jeffrey L. Carson, MD, from Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in a press briefing.

He presented the study in a late-breaking trial session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and it was simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Whether to transfuse is an everyday decision faced by clinicians caring for patients with acute MI,” Dr. Carson said.

“We cannot claim that a liberal transfusion strategy is definitively superior based on our primary outcome,” he said, but “the 95% confidence interval is consistent with treatment effects corresponding to no difference between the two transfusion strategies and to a clinically relevant benefit with the liberal strategy.”

“In contrast to other trials in other settings,” such as anemia and cardiac surgery, Dr. Carson said, “the results suggest that a liberal transfusion strategy has the potential for clinical benefit with an acceptable risk of harm.”

“A liberal transfusion strategy may be the most prudent approach to transfusion in anemic patients with MI,” he added.

Not a home run

Others agreed with this interpretation. Martin B. Leon, MD, from Columbia University, New York, the study discussant in the press briefing, said the study “addresses a question that is common” in clinical practice. It was well conducted, and international (although most patients were in the United States and Canada), in a very broad group of patients, designed to make the results more generalizable. The 98% follow-up was extremely good, Dr. Leon added, and the trialists achieved their goal in that they did show a difference between the two transfusion strategies.

The number needed to treat was 40 to see a benefit in the combined outcome of death or recurrent MI at 30 days, Dr. Leon said. The P value for this was .07, “right on the edge” of statistical significance.

This study is “not a home run,” for the primary outcome, he noted; however, many of the outcomes tended to be in favor of a liberal transfusion strategy. Notably, cardiovascular death, which was not a specified outcome, was significantly lower in the group who received a liberal transfusion strategy.

Although a liberal transfusion strategy was “not definitely superior” in these patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Carson said, he thinks the trial will be interpreted as favoring a liberal transfusion strategy.

C. Michael Gibson, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard’s Baim and PERFUSE institutes for clinical research, voiced similar views.

“Given the lack of acute harm associated with liberal transfusion and the preponderance of evidence favoring liberal transfusion in the largest trial to date,” concluded Dr. Gibson, the assigned discussant at the session, “liberal transfusion appears to be a viable management strategy, particularly among patients with non-STEMI type 1 MI and as clinical judgment dictates.”

Only three small randomized controlled trials have compared transfusion thresholds in a total of 820 patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Gibson said, a point that the trial investigators also made. The results were inconsistent between trials: the CRIT trial (n = 45) favored a restrictive strategy, the MINT pilot study (n = 110) favored a liberal one, and the REALITY trial (n = 668) showed noninferiority of a restrictive strategy, compared with a liberal strategy in 30-day MACE.

The MINT trial was four times larger than all prior studies combined. However, most outcomes were negative or of borderline significance for benefit.

Cardiac death was more common in the restrictive group at 5.5% than the liberal group at 3.2% (risk ratio, 1.74, 95% CI, 1.26-2.40), but this was nonadjudicated, and not designated as a primary, secondary, or tertiary outcome – which the researchers also noted. Fewer than half of the deaths were classified as cardiac, which was “odd,” Dr. Gibson observed.

A restrictive transfusion strategy was associated with increased events among participants with type 1 MI (RR, 1.32, 95% CI, 1.04-1.67), he noted.

Study strengths included that 45.5% of participants were women, Dr. Gibson said. Limitations included that the trial was “somewhat underpowered.” Also, even in the restrictive group, participants received a mean of 0.7 units of packed red blood cells.

Adherence to the 10 g/dL threshold in the liberal transfusion group was moderate (86.3% at hospital discharge), which the researchers acknowledged. They noted that this was frequently caused by clinical discretion, such as concern about fluid overload, and to the timing of hospital discharge. In addition, long-term potential for harm (microchimerism) is not known.

“There was a consistent nonsignificant acute benefit for liberal transfusion and a nominal reduction in CV mortality and improved outcomes in patients with type 1 MI in exploratory analyses, in a trial that ended up underpowered,” Dr. Gibson summarized. “Long-term follow up would be helpful to evaluate chronic outcomes.”

This is a very well-conducted, high-quality, important study that will be considered a landmark trial, C. David Mazer, MD, University of Toronto and St. Michael’s Hospital, also in Toronto, said in an interview.

Unfortunately, “it was not as definitive as hoped for,” Dr. Mazer lamented. Nevertheless, “I think people may interpret it as providing support for a liberal transfusion strategy” in patients with anemia and MI, he said.

Dr. Mazer, who was not involved with this research, was a principal investigator on the TRICS-3 trial, which disputed a liberal RBC transfusion strategy in patients with anemia undergoing cardiac surgery, as previously reported.

The “Red Blood Cell Transfusion: 2023 AABB International Guidelines,” led by Dr. Carson and published in JAMA, recommend a restrictive strategy in stable patients, although these guidelines did not include the current study, Dr. Mazer observed.

In the REALITY trial, there were fewer major adverse cardiac events (MACE) events in the restrictive strategy, he noted.

MINT can be viewed as comparing a high versus low hemoglobin threshold. “It is possible that the best is in between,” he said.

Dr. Mazer also noted that MINT may have achieved significance if it was designed with a larger enrollment and a higher power (for example, 90% instead of 80%) to detect between-group difference for the primary outcome.

Study rationale, design, and findings

Anemia, or low RBC count, is common in patients with MI, Dr. Carson noted. A normal hemoglobin is 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in women. Administering a packed RBC transfusion only when a patient’s hemoglobin falls below 7 or 8 g/dL has been widely adopted, but it is unclear if patients with acute MI may benefit from a higher hemoglobin level.

“Blood transfusion may decrease ischemic injury by improving oxygen delivery to myocardial tissues and reduce the risk of reinfarction or death,” the researchers wrote. “Alternatively, administering more blood could result in more frequent heart failure from fluid overload, infection from immunosuppression, thrombosis from higher viscosity, and inflammation.”

From 2017 to 2023, investigators enrolled 3,504 adults aged 18 and older at 144 sites in the United States (2,157 patients), Canada (885), France (323), Brazil (105), New Zealand (25), and Australia (9).

The participants had ST-elevation or non–ST-elevation MI and hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL within 24 hours. Patients with type 1 (atherosclerotic plaque disruption), type 2 (supply-demand mismatch without atherothrombotic plaque disruption), type 4b, or type 4c MI were eligible.

They were randomly assigned to receive:

- A ‘restrictive’ transfusion strategy (1,749 patients): Transfusion was permitted but not required when a patient’s hemoglobin was less than 8 g/dL and was strongly recommended when it was less than 7 g/dL or when anginal symptoms were not controlled with medications.

- A ‘liberal’ transfusion strategy (1,755 patients): One unit of RBCs was administered after randomization, and RBCs were transfused to maintain hemoglobin 10 g/dL or higher until hospital discharge or 30 days.

The patients had a mean age of 72 years and 46% were women. More than three-quarters (78%) were White and 14% were Black. They had frequent coexisting illnesses, about a third had a history of MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, or heart failure; 14% were on a ventilator and 12% had renal dialysis. The median duration of hospitalization was 5 days in the two groups.

At baseline, the mean hemoglobin was 8.6 g/dL in both groups. At days 1, 2, and 3, the mean hemoglobin was 8.8, 8.9, and 8.9 g/dL, respectively, in the restrictive transfusion group, and 10.1, 10.4, and 10.5 g/dL, respectively, in the liberal transfusion group.

The mean number of transfused blood units was 0.7 units in the restrictive strategy group and 2.5 units in the liberal strategy group, roughly a 3.5-fold difference.

After adjustment for site and incomplete follow-up in 57 patients (20 with the restrictive strategy and 37 with the liberal strategy), the estimated RR for the primary outcome in the restrictive group versus the liberal group was 1.15 (P = .07).

“We observed that the 95% confidence interval contains values that suggest a clinical benefit for the liberal transfusion strategy and does not include values that suggest a benefit for the more restrictive transfusion strategy,” the researchers wrote. Heart failure and other safety outcomes were comparable in the two groups.

The trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the Canadian Blood Services and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health. Dr. Carson, Dr. Leon, Dr. Gibson, and Dr. Mazer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with myocardial infarction and anemia, a “liberal” red blood cell transfusion strategy did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent MI or death within 30 days, compared with a “restrictive” transfusion strategy, in the 3,500-patient MINT trial.

Jeffrey L. Carson, MD, from Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in a press briefing.

He presented the study in a late-breaking trial session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and it was simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Whether to transfuse is an everyday decision faced by clinicians caring for patients with acute MI,” Dr. Carson said.

“We cannot claim that a liberal transfusion strategy is definitively superior based on our primary outcome,” he said, but “the 95% confidence interval is consistent with treatment effects corresponding to no difference between the two transfusion strategies and to a clinically relevant benefit with the liberal strategy.”

“In contrast to other trials in other settings,” such as anemia and cardiac surgery, Dr. Carson said, “the results suggest that a liberal transfusion strategy has the potential for clinical benefit with an acceptable risk of harm.”

“A liberal transfusion strategy may be the most prudent approach to transfusion in anemic patients with MI,” he added.

Not a home run

Others agreed with this interpretation. Martin B. Leon, MD, from Columbia University, New York, the study discussant in the press briefing, said the study “addresses a question that is common” in clinical practice. It was well conducted, and international (although most patients were in the United States and Canada), in a very broad group of patients, designed to make the results more generalizable. The 98% follow-up was extremely good, Dr. Leon added, and the trialists achieved their goal in that they did show a difference between the two transfusion strategies.

The number needed to treat was 40 to see a benefit in the combined outcome of death or recurrent MI at 30 days, Dr. Leon said. The P value for this was .07, “right on the edge” of statistical significance.

This study is “not a home run,” for the primary outcome, he noted; however, many of the outcomes tended to be in favor of a liberal transfusion strategy. Notably, cardiovascular death, which was not a specified outcome, was significantly lower in the group who received a liberal transfusion strategy.

Although a liberal transfusion strategy was “not definitely superior” in these patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Carson said, he thinks the trial will be interpreted as favoring a liberal transfusion strategy.

C. Michael Gibson, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard’s Baim and PERFUSE institutes for clinical research, voiced similar views.

“Given the lack of acute harm associated with liberal transfusion and the preponderance of evidence favoring liberal transfusion in the largest trial to date,” concluded Dr. Gibson, the assigned discussant at the session, “liberal transfusion appears to be a viable management strategy, particularly among patients with non-STEMI type 1 MI and as clinical judgment dictates.”

Only three small randomized controlled trials have compared transfusion thresholds in a total of 820 patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Gibson said, a point that the trial investigators also made. The results were inconsistent between trials: the CRIT trial (n = 45) favored a restrictive strategy, the MINT pilot study (n = 110) favored a liberal one, and the REALITY trial (n = 668) showed noninferiority of a restrictive strategy, compared with a liberal strategy in 30-day MACE.

The MINT trial was four times larger than all prior studies combined. However, most outcomes were negative or of borderline significance for benefit.

Cardiac death was more common in the restrictive group at 5.5% than the liberal group at 3.2% (risk ratio, 1.74, 95% CI, 1.26-2.40), but this was nonadjudicated, and not designated as a primary, secondary, or tertiary outcome – which the researchers also noted. Fewer than half of the deaths were classified as cardiac, which was “odd,” Dr. Gibson observed.

A restrictive transfusion strategy was associated with increased events among participants with type 1 MI (RR, 1.32, 95% CI, 1.04-1.67), he noted.

Study strengths included that 45.5% of participants were women, Dr. Gibson said. Limitations included that the trial was “somewhat underpowered.” Also, even in the restrictive group, participants received a mean of 0.7 units of packed red blood cells.

Adherence to the 10 g/dL threshold in the liberal transfusion group was moderate (86.3% at hospital discharge), which the researchers acknowledged. They noted that this was frequently caused by clinical discretion, such as concern about fluid overload, and to the timing of hospital discharge. In addition, long-term potential for harm (microchimerism) is not known.

“There was a consistent nonsignificant acute benefit for liberal transfusion and a nominal reduction in CV mortality and improved outcomes in patients with type 1 MI in exploratory analyses, in a trial that ended up underpowered,” Dr. Gibson summarized. “Long-term follow up would be helpful to evaluate chronic outcomes.”

This is a very well-conducted, high-quality, important study that will be considered a landmark trial, C. David Mazer, MD, University of Toronto and St. Michael’s Hospital, also in Toronto, said in an interview.

Unfortunately, “it was not as definitive as hoped for,” Dr. Mazer lamented. Nevertheless, “I think people may interpret it as providing support for a liberal transfusion strategy” in patients with anemia and MI, he said.

Dr. Mazer, who was not involved with this research, was a principal investigator on the TRICS-3 trial, which disputed a liberal RBC transfusion strategy in patients with anemia undergoing cardiac surgery, as previously reported.

The “Red Blood Cell Transfusion: 2023 AABB International Guidelines,” led by Dr. Carson and published in JAMA, recommend a restrictive strategy in stable patients, although these guidelines did not include the current study, Dr. Mazer observed.

In the REALITY trial, there were fewer major adverse cardiac events (MACE) events in the restrictive strategy, he noted.

MINT can be viewed as comparing a high versus low hemoglobin threshold. “It is possible that the best is in between,” he said.

Dr. Mazer also noted that MINT may have achieved significance if it was designed with a larger enrollment and a higher power (for example, 90% instead of 80%) to detect between-group difference for the primary outcome.

Study rationale, design, and findings

Anemia, or low RBC count, is common in patients with MI, Dr. Carson noted. A normal hemoglobin is 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in women. Administering a packed RBC transfusion only when a patient’s hemoglobin falls below 7 or 8 g/dL has been widely adopted, but it is unclear if patients with acute MI may benefit from a higher hemoglobin level.

“Blood transfusion may decrease ischemic injury by improving oxygen delivery to myocardial tissues and reduce the risk of reinfarction or death,” the researchers wrote. “Alternatively, administering more blood could result in more frequent heart failure from fluid overload, infection from immunosuppression, thrombosis from higher viscosity, and inflammation.”

From 2017 to 2023, investigators enrolled 3,504 adults aged 18 and older at 144 sites in the United States (2,157 patients), Canada (885), France (323), Brazil (105), New Zealand (25), and Australia (9).

The participants had ST-elevation or non–ST-elevation MI and hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL within 24 hours. Patients with type 1 (atherosclerotic plaque disruption), type 2 (supply-demand mismatch without atherothrombotic plaque disruption), type 4b, or type 4c MI were eligible.

They were randomly assigned to receive:

- A ‘restrictive’ transfusion strategy (1,749 patients): Transfusion was permitted but not required when a patient’s hemoglobin was less than 8 g/dL and was strongly recommended when it was less than 7 g/dL or when anginal symptoms were not controlled with medications.

- A ‘liberal’ transfusion strategy (1,755 patients): One unit of RBCs was administered after randomization, and RBCs were transfused to maintain hemoglobin 10 g/dL or higher until hospital discharge or 30 days.

The patients had a mean age of 72 years and 46% were women. More than three-quarters (78%) were White and 14% were Black. They had frequent coexisting illnesses, about a third had a history of MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, or heart failure; 14% were on a ventilator and 12% had renal dialysis. The median duration of hospitalization was 5 days in the two groups.

At baseline, the mean hemoglobin was 8.6 g/dL in both groups. At days 1, 2, and 3, the mean hemoglobin was 8.8, 8.9, and 8.9 g/dL, respectively, in the restrictive transfusion group, and 10.1, 10.4, and 10.5 g/dL, respectively, in the liberal transfusion group.

The mean number of transfused blood units was 0.7 units in the restrictive strategy group and 2.5 units in the liberal strategy group, roughly a 3.5-fold difference.

After adjustment for site and incomplete follow-up in 57 patients (20 with the restrictive strategy and 37 with the liberal strategy), the estimated RR for the primary outcome in the restrictive group versus the liberal group was 1.15 (P = .07).

“We observed that the 95% confidence interval contains values that suggest a clinical benefit for the liberal transfusion strategy and does not include values that suggest a benefit for the more restrictive transfusion strategy,” the researchers wrote. Heart failure and other safety outcomes were comparable in the two groups.

The trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the Canadian Blood Services and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health. Dr. Carson, Dr. Leon, Dr. Gibson, and Dr. Mazer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with myocardial infarction and anemia, a “liberal” red blood cell transfusion strategy did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent MI or death within 30 days, compared with a “restrictive” transfusion strategy, in the 3,500-patient MINT trial.

Jeffrey L. Carson, MD, from Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in a press briefing.

He presented the study in a late-breaking trial session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, and it was simultaneously published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Whether to transfuse is an everyday decision faced by clinicians caring for patients with acute MI,” Dr. Carson said.

“We cannot claim that a liberal transfusion strategy is definitively superior based on our primary outcome,” he said, but “the 95% confidence interval is consistent with treatment effects corresponding to no difference between the two transfusion strategies and to a clinically relevant benefit with the liberal strategy.”

“In contrast to other trials in other settings,” such as anemia and cardiac surgery, Dr. Carson said, “the results suggest that a liberal transfusion strategy has the potential for clinical benefit with an acceptable risk of harm.”

“A liberal transfusion strategy may be the most prudent approach to transfusion in anemic patients with MI,” he added.

Not a home run

Others agreed with this interpretation. Martin B. Leon, MD, from Columbia University, New York, the study discussant in the press briefing, said the study “addresses a question that is common” in clinical practice. It was well conducted, and international (although most patients were in the United States and Canada), in a very broad group of patients, designed to make the results more generalizable. The 98% follow-up was extremely good, Dr. Leon added, and the trialists achieved their goal in that they did show a difference between the two transfusion strategies.

The number needed to treat was 40 to see a benefit in the combined outcome of death or recurrent MI at 30 days, Dr. Leon said. The P value for this was .07, “right on the edge” of statistical significance.

This study is “not a home run,” for the primary outcome, he noted; however, many of the outcomes tended to be in favor of a liberal transfusion strategy. Notably, cardiovascular death, which was not a specified outcome, was significantly lower in the group who received a liberal transfusion strategy.

Although a liberal transfusion strategy was “not definitely superior” in these patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Carson said, he thinks the trial will be interpreted as favoring a liberal transfusion strategy.

C. Michael Gibson, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and CEO of Harvard’s Baim and PERFUSE institutes for clinical research, voiced similar views.

“Given the lack of acute harm associated with liberal transfusion and the preponderance of evidence favoring liberal transfusion in the largest trial to date,” concluded Dr. Gibson, the assigned discussant at the session, “liberal transfusion appears to be a viable management strategy, particularly among patients with non-STEMI type 1 MI and as clinical judgment dictates.”

Only three small randomized controlled trials have compared transfusion thresholds in a total of 820 patients with MI and anemia, Dr. Gibson said, a point that the trial investigators also made. The results were inconsistent between trials: the CRIT trial (n = 45) favored a restrictive strategy, the MINT pilot study (n = 110) favored a liberal one, and the REALITY trial (n = 668) showed noninferiority of a restrictive strategy, compared with a liberal strategy in 30-day MACE.

The MINT trial was four times larger than all prior studies combined. However, most outcomes were negative or of borderline significance for benefit.

Cardiac death was more common in the restrictive group at 5.5% than the liberal group at 3.2% (risk ratio, 1.74, 95% CI, 1.26-2.40), but this was nonadjudicated, and not designated as a primary, secondary, or tertiary outcome – which the researchers also noted. Fewer than half of the deaths were classified as cardiac, which was “odd,” Dr. Gibson observed.

A restrictive transfusion strategy was associated with increased events among participants with type 1 MI (RR, 1.32, 95% CI, 1.04-1.67), he noted.

Study strengths included that 45.5% of participants were women, Dr. Gibson said. Limitations included that the trial was “somewhat underpowered.” Also, even in the restrictive group, participants received a mean of 0.7 units of packed red blood cells.

Adherence to the 10 g/dL threshold in the liberal transfusion group was moderate (86.3% at hospital discharge), which the researchers acknowledged. They noted that this was frequently caused by clinical discretion, such as concern about fluid overload, and to the timing of hospital discharge. In addition, long-term potential for harm (microchimerism) is not known.

“There was a consistent nonsignificant acute benefit for liberal transfusion and a nominal reduction in CV mortality and improved outcomes in patients with type 1 MI in exploratory analyses, in a trial that ended up underpowered,” Dr. Gibson summarized. “Long-term follow up would be helpful to evaluate chronic outcomes.”

This is a very well-conducted, high-quality, important study that will be considered a landmark trial, C. David Mazer, MD, University of Toronto and St. Michael’s Hospital, also in Toronto, said in an interview.

Unfortunately, “it was not as definitive as hoped for,” Dr. Mazer lamented. Nevertheless, “I think people may interpret it as providing support for a liberal transfusion strategy” in patients with anemia and MI, he said.

Dr. Mazer, who was not involved with this research, was a principal investigator on the TRICS-3 trial, which disputed a liberal RBC transfusion strategy in patients with anemia undergoing cardiac surgery, as previously reported.

The “Red Blood Cell Transfusion: 2023 AABB International Guidelines,” led by Dr. Carson and published in JAMA, recommend a restrictive strategy in stable patients, although these guidelines did not include the current study, Dr. Mazer observed.

In the REALITY trial, there were fewer major adverse cardiac events (MACE) events in the restrictive strategy, he noted.

MINT can be viewed as comparing a high versus low hemoglobin threshold. “It is possible that the best is in between,” he said.

Dr. Mazer also noted that MINT may have achieved significance if it was designed with a larger enrollment and a higher power (for example, 90% instead of 80%) to detect between-group difference for the primary outcome.

Study rationale, design, and findings

Anemia, or low RBC count, is common in patients with MI, Dr. Carson noted. A normal hemoglobin is 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in women. Administering a packed RBC transfusion only when a patient’s hemoglobin falls below 7 or 8 g/dL has been widely adopted, but it is unclear if patients with acute MI may benefit from a higher hemoglobin level.

“Blood transfusion may decrease ischemic injury by improving oxygen delivery to myocardial tissues and reduce the risk of reinfarction or death,” the researchers wrote. “Alternatively, administering more blood could result in more frequent heart failure from fluid overload, infection from immunosuppression, thrombosis from higher viscosity, and inflammation.”

From 2017 to 2023, investigators enrolled 3,504 adults aged 18 and older at 144 sites in the United States (2,157 patients), Canada (885), France (323), Brazil (105), New Zealand (25), and Australia (9).

The participants had ST-elevation or non–ST-elevation MI and hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL within 24 hours. Patients with type 1 (atherosclerotic plaque disruption), type 2 (supply-demand mismatch without atherothrombotic plaque disruption), type 4b, or type 4c MI were eligible.

They were randomly assigned to receive:

- A ‘restrictive’ transfusion strategy (1,749 patients): Transfusion was permitted but not required when a patient’s hemoglobin was less than 8 g/dL and was strongly recommended when it was less than 7 g/dL or when anginal symptoms were not controlled with medications.

- A ‘liberal’ transfusion strategy (1,755 patients): One unit of RBCs was administered after randomization, and RBCs were transfused to maintain hemoglobin 10 g/dL or higher until hospital discharge or 30 days.

The patients had a mean age of 72 years and 46% were women. More than three-quarters (78%) were White and 14% were Black. They had frequent coexisting illnesses, about a third had a history of MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, or heart failure; 14% were on a ventilator and 12% had renal dialysis. The median duration of hospitalization was 5 days in the two groups.

At baseline, the mean hemoglobin was 8.6 g/dL in both groups. At days 1, 2, and 3, the mean hemoglobin was 8.8, 8.9, and 8.9 g/dL, respectively, in the restrictive transfusion group, and 10.1, 10.4, and 10.5 g/dL, respectively, in the liberal transfusion group.

The mean number of transfused blood units was 0.7 units in the restrictive strategy group and 2.5 units in the liberal strategy group, roughly a 3.5-fold difference.

After adjustment for site and incomplete follow-up in 57 patients (20 with the restrictive strategy and 37 with the liberal strategy), the estimated RR for the primary outcome in the restrictive group versus the liberal group was 1.15 (P = .07).

“We observed that the 95% confidence interval contains values that suggest a clinical benefit for the liberal transfusion strategy and does not include values that suggest a benefit for the more restrictive transfusion strategy,” the researchers wrote. Heart failure and other safety outcomes were comparable in the two groups.

The trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the Canadian Blood Services and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health. Dr. Carson, Dr. Leon, Dr. Gibson, and Dr. Mazer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA 2023

Short aspirin therapy noninferior to DAPT for 1 year after PCI for ACS

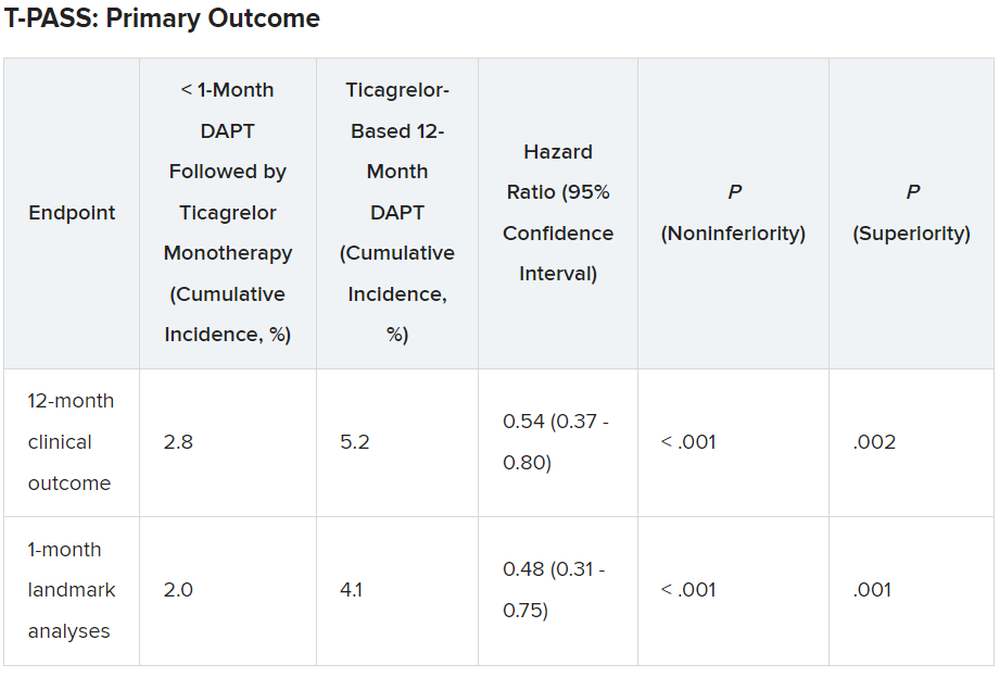

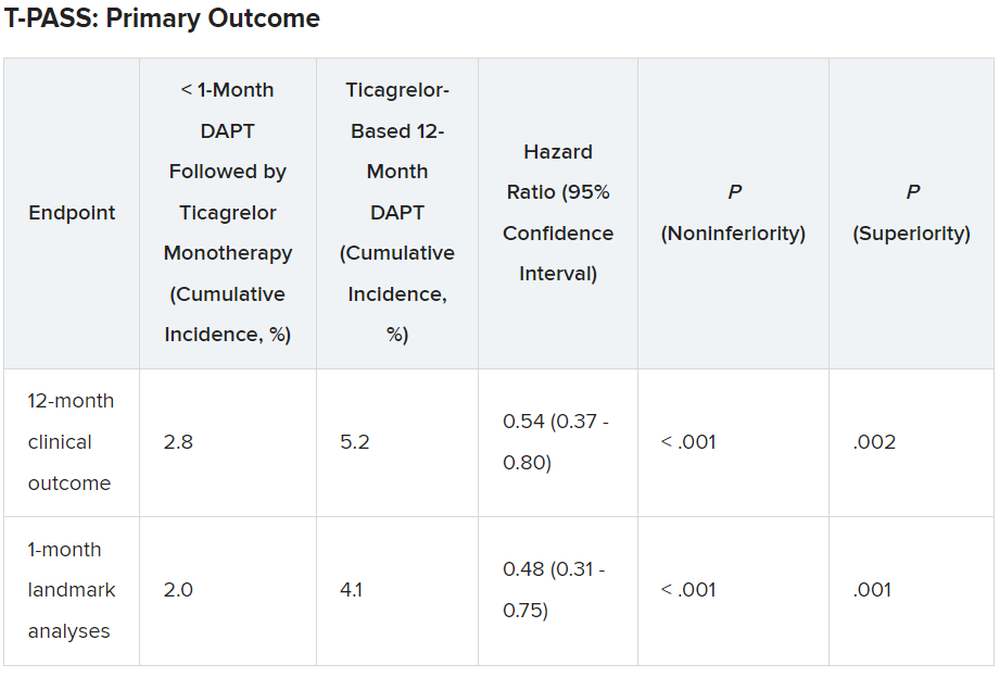

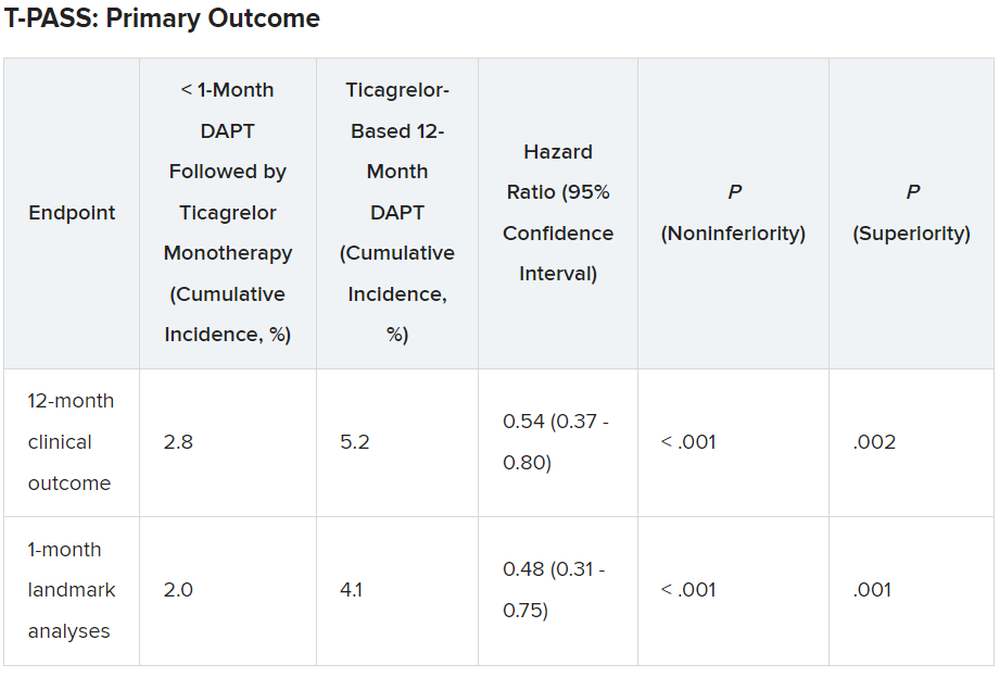

SAN FRANCISCO – Stopping aspirin within 1 month of implanting a drug-eluting stent (DES) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) followed by ticagrelor monotherapy was shown to be noninferior to 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in net adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in the T-PASS trial.

of death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and major bleeding, primarily due to a significant reduction in bleeding events,” senior author Myeong-Ki Hong, MD, PhD, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, told attendees at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“This study provides evidence that stopping aspirin within 1 month after implantation of drug-eluting stents for ticagrelor monotherapy is a reasonable alternative to 12-month DAPT as for adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events,” Dr. Hong concluded.

The study was published in Circulation ahead of print to coincide with the presentation.

Three months to 1 month

Previous trials (TICO and TWILIGHT) have shown that ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT can be safe and effectively prevent ischemic events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in ACS or high-risk PCI patients.

The current study aimed to investigate whether ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 12 months of ticagrelor-based DAPT for preventing adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients with ACS undergoing PCI with a DES implant.

T-PASS, carried out at 24 centers in Korea, enrolled ACS patients aged 19 years or older who received an ultrathin, bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (Orsiro, Biotronik). They were randomized 1:1 to ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT (n = 1,426) or to ticagrelor-based DAPT for 12 months (n = 1,424).

The primary outcome measure was net adverse clinical events (NACE) at 12 months, consisting of major bleeding plus major adverse cardiovascular events. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

The study could enroll patients aged 19-80 years. It excluded anyone with active bleeding, at increased risk for bleeding, with anemia (hemoglobin ≤ 8 g/dL), platelets less than 100,000/mcL, need for oral anticoagulation therapy, current or potential pregnancy, or a life expectancy less than 1 year.

Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced. The extended monotherapy and DAPT arms had an average age of 61 ± 10 years, were 84% and 83% male and had diabetes mellitus in 30% and 29%, respectively, with 74% of each group admitted via the emergency room. ST-elevation myocardial infarction occurred in 40% and 41% of patients in each group, respectively.

Results showed that stopping aspirin early was noninferior and possibly superior to 12 months of DAPT.

For the 12-month clinical outcome, fewer patients in the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm reached the primary clinical endpoint of NACE versus the ticagrelor-based 12-month DAPT arm, both in terms of noninferiority (P < .001) and superiority (P = .002). Similar results were found for the 1-month landmark analyses.

For both the 12-month clinical outcome and the 1-month landmark analyses, the curves for the two arms began to diverge at about 150 days, with the one for ticagrelor monotherapy essentially flattening out just after that and the one for the 12-month DAPT therapy continuing to rise out to the 1-year point.

In the less than 1 month DAPT arm, aspirin was stopped at a median of 16 days. Panelist Adnan Kastrati, MD, Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany, asked Dr. Hong about the criteria for the point at which aspirin was stopped in the less than 1 month arm.

Dr. Hong replied: “Actually, we recommend less than 1 month, so therefore in some patients, it was the operator’s decision,” depending on risk factors for stopping or continuing aspirin. He said that in some patients it may be reasonable to stop aspirin even in 7-10 days. Fewer than 10% of patients in the less than 1 month arm continued on aspirin past 30 days, but a few continued on it to the 1-year point.

There was no difference between the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm and the 12-month DAPT arm in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 1 year (1.8% vs. 2.2%, respectively; hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-1.41; log-rank, P = .51).

However, the 12-month DAPT arm showed a significantly greater incidence of major bleeding at 1 year: 3.4% versus 1.2% for less than 1 month aspirin arm (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20-0.61; log-rank, P < .001).

Dr. Hong said that a limitation of the study was that it was open label and not placebo controlled. However, an independent clinical event adjudication committee assessed all clinical outcomes.

Lead discussant Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, Cardiocentro Ticino Foundation, Lugano, Switzerland, noted that T-PASS is the fifth study to investigate ticagrelor monotherapy versus a DAPT, giving randomized data on almost 22,000 patients.

“T-PASS showed very consistently with the prior four studies that by dropping aspirin and continuation with ticagrelor therapy, compared with the standard DAPT regimen, is associated with no penalty ... and in fact leading to a very significant and clinically very convincing risk reduction, and I would like to underline major bleeding risk reduction,” he said, pointing out that this study comes from the same research group that carried out the TICO trial.

Dr. Hong has received institutional research grants from Samjin Pharmaceutical and Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical, and speaker’s fees from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kastrati has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Valgimigli has received grant support/research contracts from Terumo Medical and AstraZeneca; consultant fees/honoraria/speaker’s bureau for Terumo Medical Corporation, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Amgen, Alvimedica, AstraZenca, Idorsia, Coreflow, Vifor, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and iVascular. The study was funded by Biotronik.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – Stopping aspirin within 1 month of implanting a drug-eluting stent (DES) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) followed by ticagrelor monotherapy was shown to be noninferior to 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in net adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in the T-PASS trial.

of death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and major bleeding, primarily due to a significant reduction in bleeding events,” senior author Myeong-Ki Hong, MD, PhD, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, told attendees at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“This study provides evidence that stopping aspirin within 1 month after implantation of drug-eluting stents for ticagrelor monotherapy is a reasonable alternative to 12-month DAPT as for adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events,” Dr. Hong concluded.

The study was published in Circulation ahead of print to coincide with the presentation.

Three months to 1 month

Previous trials (TICO and TWILIGHT) have shown that ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT can be safe and effectively prevent ischemic events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in ACS or high-risk PCI patients.

The current study aimed to investigate whether ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 12 months of ticagrelor-based DAPT for preventing adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients with ACS undergoing PCI with a DES implant.

T-PASS, carried out at 24 centers in Korea, enrolled ACS patients aged 19 years or older who received an ultrathin, bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (Orsiro, Biotronik). They were randomized 1:1 to ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT (n = 1,426) or to ticagrelor-based DAPT for 12 months (n = 1,424).

The primary outcome measure was net adverse clinical events (NACE) at 12 months, consisting of major bleeding plus major adverse cardiovascular events. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

The study could enroll patients aged 19-80 years. It excluded anyone with active bleeding, at increased risk for bleeding, with anemia (hemoglobin ≤ 8 g/dL), platelets less than 100,000/mcL, need for oral anticoagulation therapy, current or potential pregnancy, or a life expectancy less than 1 year.

Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced. The extended monotherapy and DAPT arms had an average age of 61 ± 10 years, were 84% and 83% male and had diabetes mellitus in 30% and 29%, respectively, with 74% of each group admitted via the emergency room. ST-elevation myocardial infarction occurred in 40% and 41% of patients in each group, respectively.

Results showed that stopping aspirin early was noninferior and possibly superior to 12 months of DAPT.

For the 12-month clinical outcome, fewer patients in the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm reached the primary clinical endpoint of NACE versus the ticagrelor-based 12-month DAPT arm, both in terms of noninferiority (P < .001) and superiority (P = .002). Similar results were found for the 1-month landmark analyses.

For both the 12-month clinical outcome and the 1-month landmark analyses, the curves for the two arms began to diverge at about 150 days, with the one for ticagrelor monotherapy essentially flattening out just after that and the one for the 12-month DAPT therapy continuing to rise out to the 1-year point.

In the less than 1 month DAPT arm, aspirin was stopped at a median of 16 days. Panelist Adnan Kastrati, MD, Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany, asked Dr. Hong about the criteria for the point at which aspirin was stopped in the less than 1 month arm.

Dr. Hong replied: “Actually, we recommend less than 1 month, so therefore in some patients, it was the operator’s decision,” depending on risk factors for stopping or continuing aspirin. He said that in some patients it may be reasonable to stop aspirin even in 7-10 days. Fewer than 10% of patients in the less than 1 month arm continued on aspirin past 30 days, but a few continued on it to the 1-year point.

There was no difference between the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm and the 12-month DAPT arm in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 1 year (1.8% vs. 2.2%, respectively; hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-1.41; log-rank, P = .51).

However, the 12-month DAPT arm showed a significantly greater incidence of major bleeding at 1 year: 3.4% versus 1.2% for less than 1 month aspirin arm (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20-0.61; log-rank, P < .001).

Dr. Hong said that a limitation of the study was that it was open label and not placebo controlled. However, an independent clinical event adjudication committee assessed all clinical outcomes.

Lead discussant Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, Cardiocentro Ticino Foundation, Lugano, Switzerland, noted that T-PASS is the fifth study to investigate ticagrelor monotherapy versus a DAPT, giving randomized data on almost 22,000 patients.

“T-PASS showed very consistently with the prior four studies that by dropping aspirin and continuation with ticagrelor therapy, compared with the standard DAPT regimen, is associated with no penalty ... and in fact leading to a very significant and clinically very convincing risk reduction, and I would like to underline major bleeding risk reduction,” he said, pointing out that this study comes from the same research group that carried out the TICO trial.

Dr. Hong has received institutional research grants from Samjin Pharmaceutical and Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical, and speaker’s fees from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kastrati has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Valgimigli has received grant support/research contracts from Terumo Medical and AstraZeneca; consultant fees/honoraria/speaker’s bureau for Terumo Medical Corporation, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Amgen, Alvimedica, AstraZenca, Idorsia, Coreflow, Vifor, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and iVascular. The study was funded by Biotronik.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – Stopping aspirin within 1 month of implanting a drug-eluting stent (DES) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) followed by ticagrelor monotherapy was shown to be noninferior to 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in net adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in the T-PASS trial.

of death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and major bleeding, primarily due to a significant reduction in bleeding events,” senior author Myeong-Ki Hong, MD, PhD, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, told attendees at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“This study provides evidence that stopping aspirin within 1 month after implantation of drug-eluting stents for ticagrelor monotherapy is a reasonable alternative to 12-month DAPT as for adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events,” Dr. Hong concluded.

The study was published in Circulation ahead of print to coincide with the presentation.

Three months to 1 month

Previous trials (TICO and TWILIGHT) have shown that ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT can be safe and effectively prevent ischemic events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in ACS or high-risk PCI patients.

The current study aimed to investigate whether ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 12 months of ticagrelor-based DAPT for preventing adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients with ACS undergoing PCI with a DES implant.

T-PASS, carried out at 24 centers in Korea, enrolled ACS patients aged 19 years or older who received an ultrathin, bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (Orsiro, Biotronik). They were randomized 1:1 to ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT (n = 1,426) or to ticagrelor-based DAPT for 12 months (n = 1,424).

The primary outcome measure was net adverse clinical events (NACE) at 12 months, consisting of major bleeding plus major adverse cardiovascular events. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

The study could enroll patients aged 19-80 years. It excluded anyone with active bleeding, at increased risk for bleeding, with anemia (hemoglobin ≤ 8 g/dL), platelets less than 100,000/mcL, need for oral anticoagulation therapy, current or potential pregnancy, or a life expectancy less than 1 year.

Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced. The extended monotherapy and DAPT arms had an average age of 61 ± 10 years, were 84% and 83% male and had diabetes mellitus in 30% and 29%, respectively, with 74% of each group admitted via the emergency room. ST-elevation myocardial infarction occurred in 40% and 41% of patients in each group, respectively.

Results showed that stopping aspirin early was noninferior and possibly superior to 12 months of DAPT.

For the 12-month clinical outcome, fewer patients in the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm reached the primary clinical endpoint of NACE versus the ticagrelor-based 12-month DAPT arm, both in terms of noninferiority (P < .001) and superiority (P = .002). Similar results were found for the 1-month landmark analyses.

For both the 12-month clinical outcome and the 1-month landmark analyses, the curves for the two arms began to diverge at about 150 days, with the one for ticagrelor monotherapy essentially flattening out just after that and the one for the 12-month DAPT therapy continuing to rise out to the 1-year point.

In the less than 1 month DAPT arm, aspirin was stopped at a median of 16 days. Panelist Adnan Kastrati, MD, Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany, asked Dr. Hong about the criteria for the point at which aspirin was stopped in the less than 1 month arm.

Dr. Hong replied: “Actually, we recommend less than 1 month, so therefore in some patients, it was the operator’s decision,” depending on risk factors for stopping or continuing aspirin. He said that in some patients it may be reasonable to stop aspirin even in 7-10 days. Fewer than 10% of patients in the less than 1 month arm continued on aspirin past 30 days, but a few continued on it to the 1-year point.

There was no difference between the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm and the 12-month DAPT arm in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 1 year (1.8% vs. 2.2%, respectively; hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-1.41; log-rank, P = .51).

However, the 12-month DAPT arm showed a significantly greater incidence of major bleeding at 1 year: 3.4% versus 1.2% for less than 1 month aspirin arm (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20-0.61; log-rank, P < .001).

Dr. Hong said that a limitation of the study was that it was open label and not placebo controlled. However, an independent clinical event adjudication committee assessed all clinical outcomes.

Lead discussant Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, Cardiocentro Ticino Foundation, Lugano, Switzerland, noted that T-PASS is the fifth study to investigate ticagrelor monotherapy versus a DAPT, giving randomized data on almost 22,000 patients.

“T-PASS showed very consistently with the prior four studies that by dropping aspirin and continuation with ticagrelor therapy, compared with the standard DAPT regimen, is associated with no penalty ... and in fact leading to a very significant and clinically very convincing risk reduction, and I would like to underline major bleeding risk reduction,” he said, pointing out that this study comes from the same research group that carried out the TICO trial.

Dr. Hong has received institutional research grants from Samjin Pharmaceutical and Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical, and speaker’s fees from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kastrati has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Valgimigli has received grant support/research contracts from Terumo Medical and AstraZeneca; consultant fees/honoraria/speaker’s bureau for Terumo Medical Corporation, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Amgen, Alvimedica, AstraZenca, Idorsia, Coreflow, Vifor, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and iVascular. The study was funded by Biotronik.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT TCT 2023

Marijuana use dramatically increases risk of heart problems, stroke

Regularly using marijuana can significantly increase a person’s risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke, according to a pair of new studies that will be presented at a major upcoming medical conference.

People who use marijuana daily have a 34% increased risk of heart failure, compared with people who don’t use the drug, according to one of the new studies.

The new findings leverage health data from 157,000 people in the National Institutes of Health “All of Us” research program. Researchers analyzed whether marijuana users were more likely to experience heart failure than nonusers over the course of nearly 4 years. The results indicated that coronary artery disease was behind marijuana users’ increased risk. (Coronary artery disease is the buildup of plaque on the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart.)

The research was conducted by a team at Medstar Health, a large Maryland health care system that operates 10 hospitals plus hundreds of clinics. The findings will be presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023 in Philadelphia.

“Our results should encourage more researchers to study the use of marijuana to better understand its health implications, especially on cardiovascular risk,” said researcher Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, MD, MPH, a doctor at Medstar Health in Baltimore. “We want to provide the population with high-quality information on marijuana use and to help inform policy decisions at the state level, to educate patients, and to guide health care professionals.”

About one in five people in the United States use marijuana, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The majority of U.S. states allow marijuana to be used legally for medical purposes, and more than 20 states have legalized recreational marijuana, a tracker from the National Conference of State Legislatures shows.

A second study that will be presented at the conference shows that older people with any combination of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol who use marijuana have an increased risk for a major heart or brain event, compared with people who never used the drug.

The researchers analyzed data for more than 28,000 people age 65 and older who had health conditions that put them at risk for heart problems and whose medical records showed they were marijuana users but not tobacco users. The results showed at least a 20% increased risk of heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrest, or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

The findings are significant because medical professionals have long said that research on the long-term health effects of using marijuana are limited.

“The latest research about cannabis use indicates that smoking and inhaling cannabis increases concentrations of blood carboxyhemoglobin (carbon monoxide, a poisonous gas), tar (partly burned combustible matter) similar to the effects of inhaling a tobacco cigarette, both of which have been linked to heart muscle disease, chest pain, heart rhythm disturbances, heart attacks and other serious conditions,” said Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, chair of the volunteer writing group for the 2020 American Heart Association Scientific Statement: Medical Marijuana, Recreational Cannabis, and Cardiovascular Health, in a statement. “Together with the results of these two research studies, the cardiovascular risks of cannabis use are becoming clearer and should be carefully considered and monitored by health care professionals and the public.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Regularly using marijuana can significantly increase a person’s risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke, according to a pair of new studies that will be presented at a major upcoming medical conference.

People who use marijuana daily have a 34% increased risk of heart failure, compared with people who don’t use the drug, according to one of the new studies.

The new findings leverage health data from 157,000 people in the National Institutes of Health “All of Us” research program. Researchers analyzed whether marijuana users were more likely to experience heart failure than nonusers over the course of nearly 4 years. The results indicated that coronary artery disease was behind marijuana users’ increased risk. (Coronary artery disease is the buildup of plaque on the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart.)

The research was conducted by a team at Medstar Health, a large Maryland health care system that operates 10 hospitals plus hundreds of clinics. The findings will be presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023 in Philadelphia.

“Our results should encourage more researchers to study the use of marijuana to better understand its health implications, especially on cardiovascular risk,” said researcher Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, MD, MPH, a doctor at Medstar Health in Baltimore. “We want to provide the population with high-quality information on marijuana use and to help inform policy decisions at the state level, to educate patients, and to guide health care professionals.”

About one in five people in the United States use marijuana, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The majority of U.S. states allow marijuana to be used legally for medical purposes, and more than 20 states have legalized recreational marijuana, a tracker from the National Conference of State Legislatures shows.

A second study that will be presented at the conference shows that older people with any combination of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol who use marijuana have an increased risk for a major heart or brain event, compared with people who never used the drug.

The researchers analyzed data for more than 28,000 people age 65 and older who had health conditions that put them at risk for heart problems and whose medical records showed they were marijuana users but not tobacco users. The results showed at least a 20% increased risk of heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrest, or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

The findings are significant because medical professionals have long said that research on the long-term health effects of using marijuana are limited.

“The latest research about cannabis use indicates that smoking and inhaling cannabis increases concentrations of blood carboxyhemoglobin (carbon monoxide, a poisonous gas), tar (partly burned combustible matter) similar to the effects of inhaling a tobacco cigarette, both of which have been linked to heart muscle disease, chest pain, heart rhythm disturbances, heart attacks and other serious conditions,” said Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, chair of the volunteer writing group for the 2020 American Heart Association Scientific Statement: Medical Marijuana, Recreational Cannabis, and Cardiovascular Health, in a statement. “Together with the results of these two research studies, the cardiovascular risks of cannabis use are becoming clearer and should be carefully considered and monitored by health care professionals and the public.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Regularly using marijuana can significantly increase a person’s risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke, according to a pair of new studies that will be presented at a major upcoming medical conference.

People who use marijuana daily have a 34% increased risk of heart failure, compared with people who don’t use the drug, according to one of the new studies.

The new findings leverage health data from 157,000 people in the National Institutes of Health “All of Us” research program. Researchers analyzed whether marijuana users were more likely to experience heart failure than nonusers over the course of nearly 4 years. The results indicated that coronary artery disease was behind marijuana users’ increased risk. (Coronary artery disease is the buildup of plaque on the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart.)

The research was conducted by a team at Medstar Health, a large Maryland health care system that operates 10 hospitals plus hundreds of clinics. The findings will be presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023 in Philadelphia.

“Our results should encourage more researchers to study the use of marijuana to better understand its health implications, especially on cardiovascular risk,” said researcher Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, MD, MPH, a doctor at Medstar Health in Baltimore. “We want to provide the population with high-quality information on marijuana use and to help inform policy decisions at the state level, to educate patients, and to guide health care professionals.”

About one in five people in the United States use marijuana, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The majority of U.S. states allow marijuana to be used legally for medical purposes, and more than 20 states have legalized recreational marijuana, a tracker from the National Conference of State Legislatures shows.

A second study that will be presented at the conference shows that older people with any combination of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol who use marijuana have an increased risk for a major heart or brain event, compared with people who never used the drug.

The researchers analyzed data for more than 28,000 people age 65 and older who had health conditions that put them at risk for heart problems and whose medical records showed they were marijuana users but not tobacco users. The results showed at least a 20% increased risk of heart attack, stroke, cardiac arrest, or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

The findings are significant because medical professionals have long said that research on the long-term health effects of using marijuana are limited.

“The latest research about cannabis use indicates that smoking and inhaling cannabis increases concentrations of blood carboxyhemoglobin (carbon monoxide, a poisonous gas), tar (partly burned combustible matter) similar to the effects of inhaling a tobacco cigarette, both of which have been linked to heart muscle disease, chest pain, heart rhythm disturbances, heart attacks and other serious conditions,” said Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, chair of the volunteer writing group for the 2020 American Heart Association Scientific Statement: Medical Marijuana, Recreational Cannabis, and Cardiovascular Health, in a statement. “Together with the results of these two research studies, the cardiovascular risks of cannabis use are becoming clearer and should be carefully considered and monitored by health care professionals and the public.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM AHA 2023

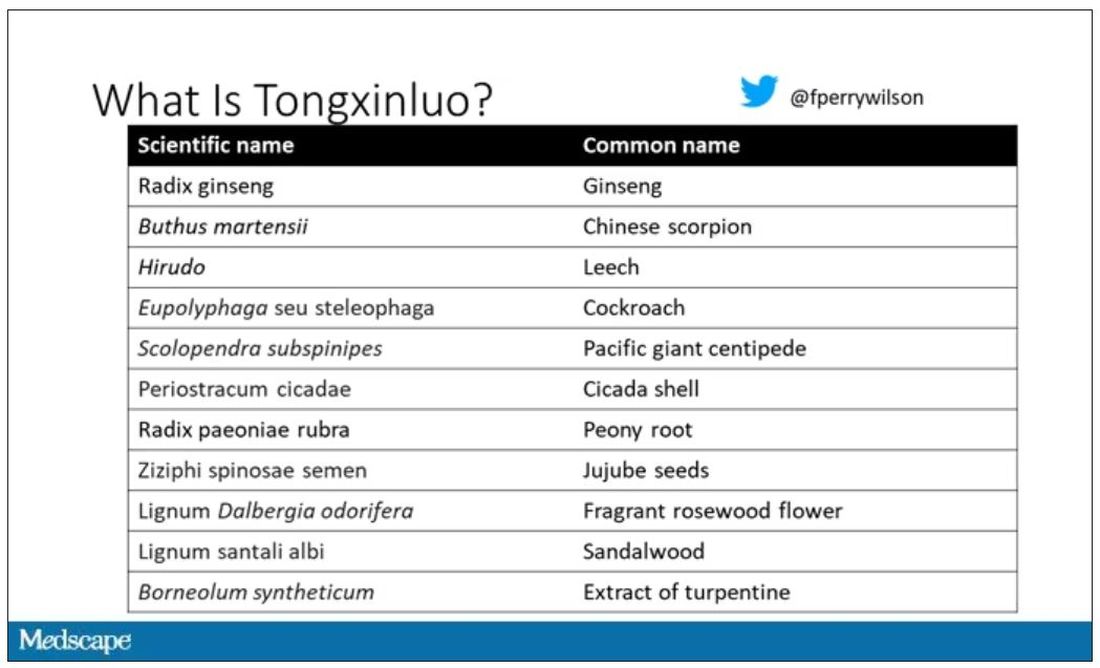

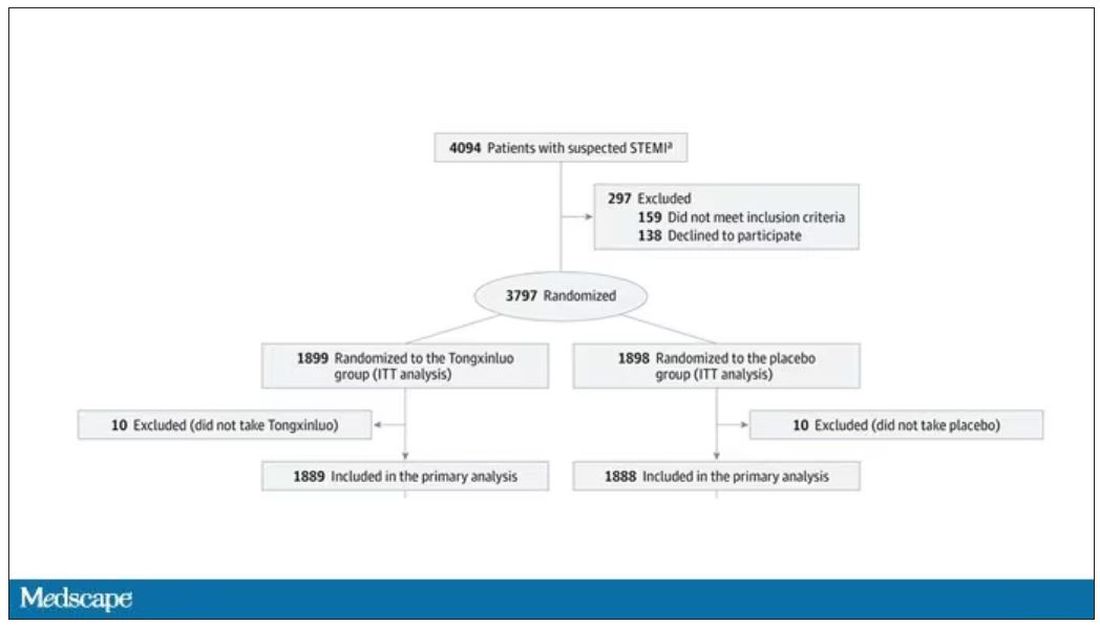

Chinese medicine improves outcomes in STEMI patients

TOPLINE: