User login

Methylphenidate Linked to Small Increase in CV Event Risk

TOPLINE:

Methylphenidate was associated with a small increased risk for cardiovascular events in individuals taking the drug for more than 6 months in a new cohort study.

METHODOLOGY:

- The retrospective, population-based cohort study was based on national Swedish registry data and included 26,710 patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) aged 12-60 years (median age 20) who had been prescribed methylphenidate between 2007 and 2012. They were each matched on birth date, sex, and county with up to 10 nonusers without ADHD (a total of 225,672 controls).

- Rates of cardiovascular events, including ischemic heart disease, venous thromboembolism, heart failure, or tachyarrhythmias 1 year before methylphenidate treatment and 6 months after treatment initiation were compared between individuals receiving methylphenidate and matched controls using a Bayesian within-individual design.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall incidence of cardiovascular events was 1.51 per 10,000 person-weeks for individuals receiving methylphenidate and 0.77 for the matched controls.

- Individuals taking methylphenidate had a 70% posterior probability for a greater than 10% increased risk for cardiovascular events than controls and a 49% posterior probability for an increased risk larger than 20%.

- No difference was found in this risk between individuals with and without a history of cardiovascular disease.

IN PRACTICE:

The researchers concluded that these results support a small (10%) increased risk for cardiovascular events in individuals receiving methylphenidate compared with matched controls after 6 months of treatment. The probability of finding a difference in risk between users and nonusers decreased when considering risk for 20% or larger, with no evidence of differences between those with and without a history of cardiovascular disease. They said the findings suggest the decision to initiate methylphenidate should incorporate considerations of potential adverse cardiovascular effects among the broader benefits and risks for treatment for individual patients.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Miguel Garcia-Argibay, PhD, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden, was published online in JAMA Network Open on March 6.

LIMITATIONS:

The data were observational, and thus, causality could not be inferred. Lack of information on methylphenidate dose meant that it was not possible to assess a dose effect. Compliance with the medication was also not known, and the association may therefore have been underestimated. The findings of this study were based on data collected from a Swedish population, which may not be representative of other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Methylphenidate was associated with a small increased risk for cardiovascular events in individuals taking the drug for more than 6 months in a new cohort study.

METHODOLOGY:

- The retrospective, population-based cohort study was based on national Swedish registry data and included 26,710 patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) aged 12-60 years (median age 20) who had been prescribed methylphenidate between 2007 and 2012. They were each matched on birth date, sex, and county with up to 10 nonusers without ADHD (a total of 225,672 controls).

- Rates of cardiovascular events, including ischemic heart disease, venous thromboembolism, heart failure, or tachyarrhythmias 1 year before methylphenidate treatment and 6 months after treatment initiation were compared between individuals receiving methylphenidate and matched controls using a Bayesian within-individual design.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall incidence of cardiovascular events was 1.51 per 10,000 person-weeks for individuals receiving methylphenidate and 0.77 for the matched controls.

- Individuals taking methylphenidate had a 70% posterior probability for a greater than 10% increased risk for cardiovascular events than controls and a 49% posterior probability for an increased risk larger than 20%.

- No difference was found in this risk between individuals with and without a history of cardiovascular disease.

IN PRACTICE:

The researchers concluded that these results support a small (10%) increased risk for cardiovascular events in individuals receiving methylphenidate compared with matched controls after 6 months of treatment. The probability of finding a difference in risk between users and nonusers decreased when considering risk for 20% or larger, with no evidence of differences between those with and without a history of cardiovascular disease. They said the findings suggest the decision to initiate methylphenidate should incorporate considerations of potential adverse cardiovascular effects among the broader benefits and risks for treatment for individual patients.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Miguel Garcia-Argibay, PhD, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden, was published online in JAMA Network Open on March 6.

LIMITATIONS:

The data were observational, and thus, causality could not be inferred. Lack of information on methylphenidate dose meant that it was not possible to assess a dose effect. Compliance with the medication was also not known, and the association may therefore have been underestimated. The findings of this study were based on data collected from a Swedish population, which may not be representative of other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Methylphenidate was associated with a small increased risk for cardiovascular events in individuals taking the drug for more than 6 months in a new cohort study.

METHODOLOGY:

- The retrospective, population-based cohort study was based on national Swedish registry data and included 26,710 patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) aged 12-60 years (median age 20) who had been prescribed methylphenidate between 2007 and 2012. They were each matched on birth date, sex, and county with up to 10 nonusers without ADHD (a total of 225,672 controls).

- Rates of cardiovascular events, including ischemic heart disease, venous thromboembolism, heart failure, or tachyarrhythmias 1 year before methylphenidate treatment and 6 months after treatment initiation were compared between individuals receiving methylphenidate and matched controls using a Bayesian within-individual design.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall incidence of cardiovascular events was 1.51 per 10,000 person-weeks for individuals receiving methylphenidate and 0.77 for the matched controls.

- Individuals taking methylphenidate had a 70% posterior probability for a greater than 10% increased risk for cardiovascular events than controls and a 49% posterior probability for an increased risk larger than 20%.

- No difference was found in this risk between individuals with and without a history of cardiovascular disease.

IN PRACTICE:

The researchers concluded that these results support a small (10%) increased risk for cardiovascular events in individuals receiving methylphenidate compared with matched controls after 6 months of treatment. The probability of finding a difference in risk between users and nonusers decreased when considering risk for 20% or larger, with no evidence of differences between those with and without a history of cardiovascular disease. They said the findings suggest the decision to initiate methylphenidate should incorporate considerations of potential adverse cardiovascular effects among the broader benefits and risks for treatment for individual patients.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Miguel Garcia-Argibay, PhD, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden, was published online in JAMA Network Open on March 6.

LIMITATIONS:

The data were observational, and thus, causality could not be inferred. Lack of information on methylphenidate dose meant that it was not possible to assess a dose effect. Compliance with the medication was also not known, and the association may therefore have been underestimated. The findings of this study were based on data collected from a Swedish population, which may not be representative of other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

No End in Sight for National ADHD Drug Shortage

Nearly 18 months after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first acknowledged a national shortage of Adderall, the most common drug used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

The first shortage of immediate release formulations of amphetamine mixed salts (Adderall, Adderall IR) was reported by the FDA in October 2022. Now, the list includes Focalin, Ritalin, and Vyvanse, among others.

Adding to the ongoing crisis, the FDA announced in early February that Azurity Pharmaceuticals was voluntarily withdrawing one lot of its Zenzedi (dextroamphetamine sulfate) 30 mg tablets because of contamination with the antihistamine, carbinoxamine.

For the roughly 10 million adults and 6 million children in the United States grappling with ADHD, getting a prescription filled with the exact medication ordered by a physician is dictated by geographic location, insurance formularies, and pharmacy supply chains. It’s particularly challenging for those who live in rural or underserved areas with limited access to nearby pharmacies.

“Not a day goes by when I don’t hear from a number of unfortunately struggling patients about this shortage,” said Aditya Pawar, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist with the Kennedy Krieger Institute and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

The ADHD drug shortage is now well into its second year, and clinicians and advocates alike say there is no apparent end in sight.

How Did We Get Here?

Manufacturers and federal agencies blame the shortage on rising demand and each other, while clinicians say that insurers, drug distributors, and middlemen are also playing a role in keeping medications out of patients’ hands.

In August 2023, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which sets quotas for the production of controlled substances, and the FDA publicly blamed manufacturers for the shortages, claiming they were not using up their allocations.

At the time, the DEA said manufacturers made and sold only 70% of their quota, nearly 1 billion doses short of what they were allowed to produce and ship that year.

The agencies also noted a record-high number of prescriptions for stimulants from 2012 to 2021. Driven in part by telehealth, the demand intensified during the pandemic. One recent study reported a 14% increase in ADHD stimulant prescriptions between 2020 and 2022.

Insurers also play a role in the shortage, David Goodman, MD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences also at Johns Hopkins University, told this news organization.

Stepped therapy — in which patients must try one, two, or three medications before they are authorized to receive a more expensive or newer drug — contributes to the problem, Dr. Goodman said. Demand for such medications is high and supply low. In addition, some insurers only provide coverage for in-network pharmacies, regardless of the ability of other providers outside such networks to fill prescriptions.

“If the insurance dictates where you get your pills, and that pharmacy doesn’t have the pills or that pharmacy chain in your area doesn’t have those pills, you’re out of luck,” Dr. Goodman said.

Patients as Detectives

To get prescriptions filled, patients must “turn into detectives,” Laurie Kulikosky, CEO of Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, told this news organization. “It’s a huge stressor.”

Tracking which ADHD medications are available, on back order, or discontinued requires frequent checking of the FDA’s drug shortages website.

Some manufacturers of generic versions of mixed amphetamine salts are only fulfilling orders for existing contracts, while others say new product won’t be available until at least April or as late as September. All blame the delay on the shortage of active ingredients.

Teva, which makes both the brand and generic of Adderall, reported on the FDA’s site that its manufacturing and distribution is at record-high levels, but demand continues to rise.

The branded Concerta is available, but some makers of generic methylphenidate reported supplies won’t be available until July.

Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in almost all dosages is either unavailable, available in restricted quantities, or on extended back order. However, the branded product Vyvanse is available.

Industry, Government Respond

In a November 2023 statement, the DEA reported that 17 of 18 drug manufacturers the agency contacted planned to use their full DEA quota and increase production for that year. The agency said it had made it easier for manufacturers to request changes in allocations and that periodically updating quotas was a possibility.

This news organization asked the DEA whether any manufacturers had not met their 2023 quotas, but an agency spokesperson said it would not comment.

An FDA spokesperson said it could help manufacturers ask for bigger quotas and to increase production, noting that in 2023, the DEA increased the quota for methylphenidate following an FDA request.

“The FDA is in frequent communication with the manufacturers of ADHD stimulant medications and the DEA, and we will continue to monitor supply,” the spokesperson said.

For 2024, the FDA told the DEA that it predicted a 3.1% increase in use of amphetamine, methylphenidate (including dexmethylphenidate), and lisdexamfetamine. The DEA took that into account when it issued its final quotas for 2024. Whether those amounts will be enough remains to be seen.

With many drugs — not just those for ADHD — in short supply, in February, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Federal Trade Commission opened an inquiry of sorts, seeking comments on how middlemen and others were influencing pricing and supply of generic drugs.

“When you’re prescribed an important medication by your doctor and you learn the drug is out of stock, your heart sinks,” HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra said in a statement. “This devastating reality is the case for too many Americans who need generic drugs for ADHD, cancer, and other conditions.”

On the comments site, which is open until April 15, many of the 4000-plus complaints filed to-date are from individuals with ADHD.

Dr. Pawar said clinicians can’t know what’s going on between the FDA, the DEA, and manufacturers, adding that, “they need to sit together and figure something out.”

Even Members of Congress have had trouble getting answers. In October, Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-Virginia) and a dozen colleagues wrote to the FDA and DEA seeking information on how the agencies were responding to stimulant shortages. The DEA has still not replied.

Workarounds the Only Option?

In the past, physicians would prescribe the optimal medication for individual patients based on clinical factors. Now, one of the major factors in determining drug choice is the agent that has “the highest likelihood of benefit and the lowest likelihood of administrative demand or burden,” Dr. Goodman said.

With so many medications in short supply, clinicians have figured out workarounds to get prescriptions filled, but they don’t often pan out.

If a patient needs a 60-mg daily dose of a medication and the pharmacy doesn’t have any 60-mg pills, Dr. Goodman said he might write a prescription for a 30-mg pill to be taken twice a day. However, insurers often will cover only 30 pills for a month, which can thwart this strategy.

Dr. Pawar said he sometimes prescribes Journay PM in lieu of Concerta because it is often available. But insurers may deny coverage of Journay PM because it is a newer medication, he said. When prescribing ADHD medications, he also provides his patients with a list of potential substitutes so they can ask the pharmacist if any are in stock.

With no end to the shortage in sight, clinicians must often prescribe multiple medications until their patients are able to find one that’s available. In addition, patients are burdened with making calls and visits to multiple pharmacies until they find one that can fill their prescription.

Meanwhile, the ripple effects to the ADHD drug shortage continue to spread. Extended periods without treatment can lead to declining job performance or job loss, fractured relationships, and even financial distress, Dr. Goodman said.

“If you go without your pills for a month and you’re not performing, your work declines and you lose your job as a result, that’s not on you — that’s on the fact that you can’t get your treatment,” he noted. “The shortage is no longer an inconvenience.”

Dr. Goodman, Dr. Pawar, and Ms. Kulikosky reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 18 months after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first acknowledged a national shortage of Adderall, the most common drug used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

The first shortage of immediate release formulations of amphetamine mixed salts (Adderall, Adderall IR) was reported by the FDA in October 2022. Now, the list includes Focalin, Ritalin, and Vyvanse, among others.

Adding to the ongoing crisis, the FDA announced in early February that Azurity Pharmaceuticals was voluntarily withdrawing one lot of its Zenzedi (dextroamphetamine sulfate) 30 mg tablets because of contamination with the antihistamine, carbinoxamine.

For the roughly 10 million adults and 6 million children in the United States grappling with ADHD, getting a prescription filled with the exact medication ordered by a physician is dictated by geographic location, insurance formularies, and pharmacy supply chains. It’s particularly challenging for those who live in rural or underserved areas with limited access to nearby pharmacies.

“Not a day goes by when I don’t hear from a number of unfortunately struggling patients about this shortage,” said Aditya Pawar, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist with the Kennedy Krieger Institute and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

The ADHD drug shortage is now well into its second year, and clinicians and advocates alike say there is no apparent end in sight.

How Did We Get Here?

Manufacturers and federal agencies blame the shortage on rising demand and each other, while clinicians say that insurers, drug distributors, and middlemen are also playing a role in keeping medications out of patients’ hands.

In August 2023, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which sets quotas for the production of controlled substances, and the FDA publicly blamed manufacturers for the shortages, claiming they were not using up their allocations.

At the time, the DEA said manufacturers made and sold only 70% of their quota, nearly 1 billion doses short of what they were allowed to produce and ship that year.

The agencies also noted a record-high number of prescriptions for stimulants from 2012 to 2021. Driven in part by telehealth, the demand intensified during the pandemic. One recent study reported a 14% increase in ADHD stimulant prescriptions between 2020 and 2022.

Insurers also play a role in the shortage, David Goodman, MD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences also at Johns Hopkins University, told this news organization.

Stepped therapy — in which patients must try one, two, or three medications before they are authorized to receive a more expensive or newer drug — contributes to the problem, Dr. Goodman said. Demand for such medications is high and supply low. In addition, some insurers only provide coverage for in-network pharmacies, regardless of the ability of other providers outside such networks to fill prescriptions.

“If the insurance dictates where you get your pills, and that pharmacy doesn’t have the pills or that pharmacy chain in your area doesn’t have those pills, you’re out of luck,” Dr. Goodman said.

Patients as Detectives

To get prescriptions filled, patients must “turn into detectives,” Laurie Kulikosky, CEO of Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, told this news organization. “It’s a huge stressor.”

Tracking which ADHD medications are available, on back order, or discontinued requires frequent checking of the FDA’s drug shortages website.

Some manufacturers of generic versions of mixed amphetamine salts are only fulfilling orders for existing contracts, while others say new product won’t be available until at least April or as late as September. All blame the delay on the shortage of active ingredients.

Teva, which makes both the brand and generic of Adderall, reported on the FDA’s site that its manufacturing and distribution is at record-high levels, but demand continues to rise.

The branded Concerta is available, but some makers of generic methylphenidate reported supplies won’t be available until July.

Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in almost all dosages is either unavailable, available in restricted quantities, or on extended back order. However, the branded product Vyvanse is available.

Industry, Government Respond

In a November 2023 statement, the DEA reported that 17 of 18 drug manufacturers the agency contacted planned to use their full DEA quota and increase production for that year. The agency said it had made it easier for manufacturers to request changes in allocations and that periodically updating quotas was a possibility.

This news organization asked the DEA whether any manufacturers had not met their 2023 quotas, but an agency spokesperson said it would not comment.

An FDA spokesperson said it could help manufacturers ask for bigger quotas and to increase production, noting that in 2023, the DEA increased the quota for methylphenidate following an FDA request.

“The FDA is in frequent communication with the manufacturers of ADHD stimulant medications and the DEA, and we will continue to monitor supply,” the spokesperson said.

For 2024, the FDA told the DEA that it predicted a 3.1% increase in use of amphetamine, methylphenidate (including dexmethylphenidate), and lisdexamfetamine. The DEA took that into account when it issued its final quotas for 2024. Whether those amounts will be enough remains to be seen.

With many drugs — not just those for ADHD — in short supply, in February, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Federal Trade Commission opened an inquiry of sorts, seeking comments on how middlemen and others were influencing pricing and supply of generic drugs.

“When you’re prescribed an important medication by your doctor and you learn the drug is out of stock, your heart sinks,” HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra said in a statement. “This devastating reality is the case for too many Americans who need generic drugs for ADHD, cancer, and other conditions.”

On the comments site, which is open until April 15, many of the 4000-plus complaints filed to-date are from individuals with ADHD.

Dr. Pawar said clinicians can’t know what’s going on between the FDA, the DEA, and manufacturers, adding that, “they need to sit together and figure something out.”

Even Members of Congress have had trouble getting answers. In October, Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-Virginia) and a dozen colleagues wrote to the FDA and DEA seeking information on how the agencies were responding to stimulant shortages. The DEA has still not replied.

Workarounds the Only Option?

In the past, physicians would prescribe the optimal medication for individual patients based on clinical factors. Now, one of the major factors in determining drug choice is the agent that has “the highest likelihood of benefit and the lowest likelihood of administrative demand or burden,” Dr. Goodman said.

With so many medications in short supply, clinicians have figured out workarounds to get prescriptions filled, but they don’t often pan out.

If a patient needs a 60-mg daily dose of a medication and the pharmacy doesn’t have any 60-mg pills, Dr. Goodman said he might write a prescription for a 30-mg pill to be taken twice a day. However, insurers often will cover only 30 pills for a month, which can thwart this strategy.

Dr. Pawar said he sometimes prescribes Journay PM in lieu of Concerta because it is often available. But insurers may deny coverage of Journay PM because it is a newer medication, he said. When prescribing ADHD medications, he also provides his patients with a list of potential substitutes so they can ask the pharmacist if any are in stock.

With no end to the shortage in sight, clinicians must often prescribe multiple medications until their patients are able to find one that’s available. In addition, patients are burdened with making calls and visits to multiple pharmacies until they find one that can fill their prescription.

Meanwhile, the ripple effects to the ADHD drug shortage continue to spread. Extended periods without treatment can lead to declining job performance or job loss, fractured relationships, and even financial distress, Dr. Goodman said.

“If you go without your pills for a month and you’re not performing, your work declines and you lose your job as a result, that’s not on you — that’s on the fact that you can’t get your treatment,” he noted. “The shortage is no longer an inconvenience.”

Dr. Goodman, Dr. Pawar, and Ms. Kulikosky reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 18 months after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first acknowledged a national shortage of Adderall, the most common drug used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

The first shortage of immediate release formulations of amphetamine mixed salts (Adderall, Adderall IR) was reported by the FDA in October 2022. Now, the list includes Focalin, Ritalin, and Vyvanse, among others.

Adding to the ongoing crisis, the FDA announced in early February that Azurity Pharmaceuticals was voluntarily withdrawing one lot of its Zenzedi (dextroamphetamine sulfate) 30 mg tablets because of contamination with the antihistamine, carbinoxamine.

For the roughly 10 million adults and 6 million children in the United States grappling with ADHD, getting a prescription filled with the exact medication ordered by a physician is dictated by geographic location, insurance formularies, and pharmacy supply chains. It’s particularly challenging for those who live in rural or underserved areas with limited access to nearby pharmacies.

“Not a day goes by when I don’t hear from a number of unfortunately struggling patients about this shortage,” said Aditya Pawar, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist with the Kennedy Krieger Institute and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

The ADHD drug shortage is now well into its second year, and clinicians and advocates alike say there is no apparent end in sight.

How Did We Get Here?

Manufacturers and federal agencies blame the shortage on rising demand and each other, while clinicians say that insurers, drug distributors, and middlemen are also playing a role in keeping medications out of patients’ hands.

In August 2023, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which sets quotas for the production of controlled substances, and the FDA publicly blamed manufacturers for the shortages, claiming they were not using up their allocations.

At the time, the DEA said manufacturers made and sold only 70% of their quota, nearly 1 billion doses short of what they were allowed to produce and ship that year.

The agencies also noted a record-high number of prescriptions for stimulants from 2012 to 2021. Driven in part by telehealth, the demand intensified during the pandemic. One recent study reported a 14% increase in ADHD stimulant prescriptions between 2020 and 2022.

Insurers also play a role in the shortage, David Goodman, MD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences also at Johns Hopkins University, told this news organization.

Stepped therapy — in which patients must try one, two, or three medications before they are authorized to receive a more expensive or newer drug — contributes to the problem, Dr. Goodman said. Demand for such medications is high and supply low. In addition, some insurers only provide coverage for in-network pharmacies, regardless of the ability of other providers outside such networks to fill prescriptions.

“If the insurance dictates where you get your pills, and that pharmacy doesn’t have the pills or that pharmacy chain in your area doesn’t have those pills, you’re out of luck,” Dr. Goodman said.

Patients as Detectives

To get prescriptions filled, patients must “turn into detectives,” Laurie Kulikosky, CEO of Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, told this news organization. “It’s a huge stressor.”

Tracking which ADHD medications are available, on back order, or discontinued requires frequent checking of the FDA’s drug shortages website.

Some manufacturers of generic versions of mixed amphetamine salts are only fulfilling orders for existing contracts, while others say new product won’t be available until at least April or as late as September. All blame the delay on the shortage of active ingredients.

Teva, which makes both the brand and generic of Adderall, reported on the FDA’s site that its manufacturing and distribution is at record-high levels, but demand continues to rise.

The branded Concerta is available, but some makers of generic methylphenidate reported supplies won’t be available until July.

Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in almost all dosages is either unavailable, available in restricted quantities, or on extended back order. However, the branded product Vyvanse is available.

Industry, Government Respond

In a November 2023 statement, the DEA reported that 17 of 18 drug manufacturers the agency contacted planned to use their full DEA quota and increase production for that year. The agency said it had made it easier for manufacturers to request changes in allocations and that periodically updating quotas was a possibility.

This news organization asked the DEA whether any manufacturers had not met their 2023 quotas, but an agency spokesperson said it would not comment.

An FDA spokesperson said it could help manufacturers ask for bigger quotas and to increase production, noting that in 2023, the DEA increased the quota for methylphenidate following an FDA request.

“The FDA is in frequent communication with the manufacturers of ADHD stimulant medications and the DEA, and we will continue to monitor supply,” the spokesperson said.

For 2024, the FDA told the DEA that it predicted a 3.1% increase in use of amphetamine, methylphenidate (including dexmethylphenidate), and lisdexamfetamine. The DEA took that into account when it issued its final quotas for 2024. Whether those amounts will be enough remains to be seen.

With many drugs — not just those for ADHD — in short supply, in February, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Federal Trade Commission opened an inquiry of sorts, seeking comments on how middlemen and others were influencing pricing and supply of generic drugs.

“When you’re prescribed an important medication by your doctor and you learn the drug is out of stock, your heart sinks,” HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra said in a statement. “This devastating reality is the case for too many Americans who need generic drugs for ADHD, cancer, and other conditions.”

On the comments site, which is open until April 15, many of the 4000-plus complaints filed to-date are from individuals with ADHD.

Dr. Pawar said clinicians can’t know what’s going on between the FDA, the DEA, and manufacturers, adding that, “they need to sit together and figure something out.”

Even Members of Congress have had trouble getting answers. In October, Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-Virginia) and a dozen colleagues wrote to the FDA and DEA seeking information on how the agencies were responding to stimulant shortages. The DEA has still not replied.

Workarounds the Only Option?

In the past, physicians would prescribe the optimal medication for individual patients based on clinical factors. Now, one of the major factors in determining drug choice is the agent that has “the highest likelihood of benefit and the lowest likelihood of administrative demand or burden,” Dr. Goodman said.

With so many medications in short supply, clinicians have figured out workarounds to get prescriptions filled, but they don’t often pan out.

If a patient needs a 60-mg daily dose of a medication and the pharmacy doesn’t have any 60-mg pills, Dr. Goodman said he might write a prescription for a 30-mg pill to be taken twice a day. However, insurers often will cover only 30 pills for a month, which can thwart this strategy.

Dr. Pawar said he sometimes prescribes Journay PM in lieu of Concerta because it is often available. But insurers may deny coverage of Journay PM because it is a newer medication, he said. When prescribing ADHD medications, he also provides his patients with a list of potential substitutes so they can ask the pharmacist if any are in stock.

With no end to the shortage in sight, clinicians must often prescribe multiple medications until their patients are able to find one that’s available. In addition, patients are burdened with making calls and visits to multiple pharmacies until they find one that can fill their prescription.

Meanwhile, the ripple effects to the ADHD drug shortage continue to spread. Extended periods without treatment can lead to declining job performance or job loss, fractured relationships, and even financial distress, Dr. Goodman said.

“If you go without your pills for a month and you’re not performing, your work declines and you lose your job as a result, that’s not on you — that’s on the fact that you can’t get your treatment,” he noted. “The shortage is no longer an inconvenience.”

Dr. Goodman, Dr. Pawar, and Ms. Kulikosky reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Stimulants for ADHD Not Linked to Prescription Drug Misuse

TOPLINE:

The use of stimulant therapy by adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was not associated with later prescription drug misuse (PDM), a new study showed. However, misuse of prescription stimulants during adolescence was associated with significantly higher odds of later PDM.

METHODOLOGY:

- Data came from 11,066 participants in the ongoing Monitoring the Future panel study (baseline cohort years 2005-2017), a multicohort US national longitudinal study of adolescents followed into adulthood, in which procedures and measures are kept consistent across time.

- Participants (ages 17 and 18 years, 51.7% female, 11.2% Black, 15.7% Hispanic, and 59.6% White) completed self-administered questionnaires, with biennial follow-up during young adulthood (ages 19-24 years).

- The questionnaires asked about the number of occasions (if any) in which respondents used a prescription drug (benzodiazepine, opioid, or stimulant) on their own, without a physician’s order.

- Baseline covariates included sex, race, ethnicity, grade point average during high school, parental education, past 2-week binge drinking, past-month cigarette use, and past-year marijuana use, as well as demographic factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 9.9% of participants reported lifetime stimulant therapy for ADHD, and 18.6% reported lifetime prescription stimulant misuse at baseline.

- Adolescents who received stimulant therapy for ADHD were less likely to report past-year prescription stimulant misuse as young adults compared with their same-age peers who did not receive stimulant therapy (adjusted odds ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.52-0.99).

- The researchers found no significant differences between adolescents with or without lifetime stimulants in later incidence or prevalence of past-year PDM during young adulthood.

- The most robust predictor of prescription stimulant misuse during young adulthood was prescription stimulant misuse during adolescence; similarly, the most robust predictors of prescription opioid and prescription benzodiazepine misuse during young adulthood were prescription opioid and prescription benzodiazepine misuse (respectively) during adolescence.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings amplify accumulating evidence suggesting that careful monitoring and screening during adolescence could identify individuals who are at relatively greater risk for PDM and need more comprehensive substance use assessment,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Sean Esteban McCabe, PhD, professor and director, Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, was the lead and corresponding author of the study. It was published online on February 7 in Psychiatric Sciences.

LIMITATIONS:

Some subpopulations with higher rates of substance use, including youths who left school before completion and institutionalized populations, were excluded from the study, which may have led to an underestimation of PDM. Moreover, some potential confounders (eg, comorbid psychiatric conditions) were not assessed.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by a research award from the US Food and Drug Administration and research awards from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the NIH. Dr. McCabe reported no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The use of stimulant therapy by adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was not associated with later prescription drug misuse (PDM), a new study showed. However, misuse of prescription stimulants during adolescence was associated with significantly higher odds of later PDM.

METHODOLOGY:

- Data came from 11,066 participants in the ongoing Monitoring the Future panel study (baseline cohort years 2005-2017), a multicohort US national longitudinal study of adolescents followed into adulthood, in which procedures and measures are kept consistent across time.

- Participants (ages 17 and 18 years, 51.7% female, 11.2% Black, 15.7% Hispanic, and 59.6% White) completed self-administered questionnaires, with biennial follow-up during young adulthood (ages 19-24 years).

- The questionnaires asked about the number of occasions (if any) in which respondents used a prescription drug (benzodiazepine, opioid, or stimulant) on their own, without a physician’s order.

- Baseline covariates included sex, race, ethnicity, grade point average during high school, parental education, past 2-week binge drinking, past-month cigarette use, and past-year marijuana use, as well as demographic factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 9.9% of participants reported lifetime stimulant therapy for ADHD, and 18.6% reported lifetime prescription stimulant misuse at baseline.

- Adolescents who received stimulant therapy for ADHD were less likely to report past-year prescription stimulant misuse as young adults compared with their same-age peers who did not receive stimulant therapy (adjusted odds ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.52-0.99).

- The researchers found no significant differences between adolescents with or without lifetime stimulants in later incidence or prevalence of past-year PDM during young adulthood.

- The most robust predictor of prescription stimulant misuse during young adulthood was prescription stimulant misuse during adolescence; similarly, the most robust predictors of prescription opioid and prescription benzodiazepine misuse during young adulthood were prescription opioid and prescription benzodiazepine misuse (respectively) during adolescence.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings amplify accumulating evidence suggesting that careful monitoring and screening during adolescence could identify individuals who are at relatively greater risk for PDM and need more comprehensive substance use assessment,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Sean Esteban McCabe, PhD, professor and director, Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, was the lead and corresponding author of the study. It was published online on February 7 in Psychiatric Sciences.

LIMITATIONS:

Some subpopulations with higher rates of substance use, including youths who left school before completion and institutionalized populations, were excluded from the study, which may have led to an underestimation of PDM. Moreover, some potential confounders (eg, comorbid psychiatric conditions) were not assessed.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by a research award from the US Food and Drug Administration and research awards from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the NIH. Dr. McCabe reported no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The use of stimulant therapy by adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was not associated with later prescription drug misuse (PDM), a new study showed. However, misuse of prescription stimulants during adolescence was associated with significantly higher odds of later PDM.

METHODOLOGY:

- Data came from 11,066 participants in the ongoing Monitoring the Future panel study (baseline cohort years 2005-2017), a multicohort US national longitudinal study of adolescents followed into adulthood, in which procedures and measures are kept consistent across time.

- Participants (ages 17 and 18 years, 51.7% female, 11.2% Black, 15.7% Hispanic, and 59.6% White) completed self-administered questionnaires, with biennial follow-up during young adulthood (ages 19-24 years).

- The questionnaires asked about the number of occasions (if any) in which respondents used a prescription drug (benzodiazepine, opioid, or stimulant) on their own, without a physician’s order.

- Baseline covariates included sex, race, ethnicity, grade point average during high school, parental education, past 2-week binge drinking, past-month cigarette use, and past-year marijuana use, as well as demographic factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 9.9% of participants reported lifetime stimulant therapy for ADHD, and 18.6% reported lifetime prescription stimulant misuse at baseline.

- Adolescents who received stimulant therapy for ADHD were less likely to report past-year prescription stimulant misuse as young adults compared with their same-age peers who did not receive stimulant therapy (adjusted odds ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.52-0.99).

- The researchers found no significant differences between adolescents with or without lifetime stimulants in later incidence or prevalence of past-year PDM during young adulthood.

- The most robust predictor of prescription stimulant misuse during young adulthood was prescription stimulant misuse during adolescence; similarly, the most robust predictors of prescription opioid and prescription benzodiazepine misuse during young adulthood were prescription opioid and prescription benzodiazepine misuse (respectively) during adolescence.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings amplify accumulating evidence suggesting that careful monitoring and screening during adolescence could identify individuals who are at relatively greater risk for PDM and need more comprehensive substance use assessment,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Sean Esteban McCabe, PhD, professor and director, Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking and Health, University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, was the lead and corresponding author of the study. It was published online on February 7 in Psychiatric Sciences.

LIMITATIONS:

Some subpopulations with higher rates of substance use, including youths who left school before completion and institutionalized populations, were excluded from the study, which may have led to an underestimation of PDM. Moreover, some potential confounders (eg, comorbid psychiatric conditions) were not assessed.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by a research award from the US Food and Drug Administration and research awards from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the NIH. Dr. McCabe reported no relevant financial relationships. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original paper.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Stimulant Medications for ADHD — the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

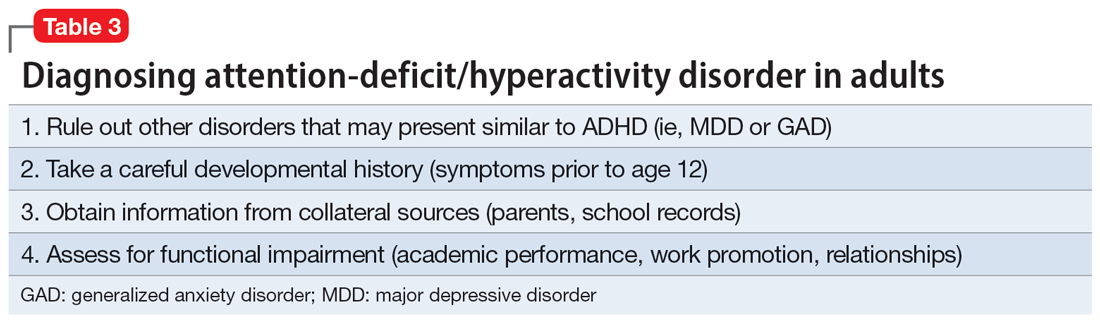

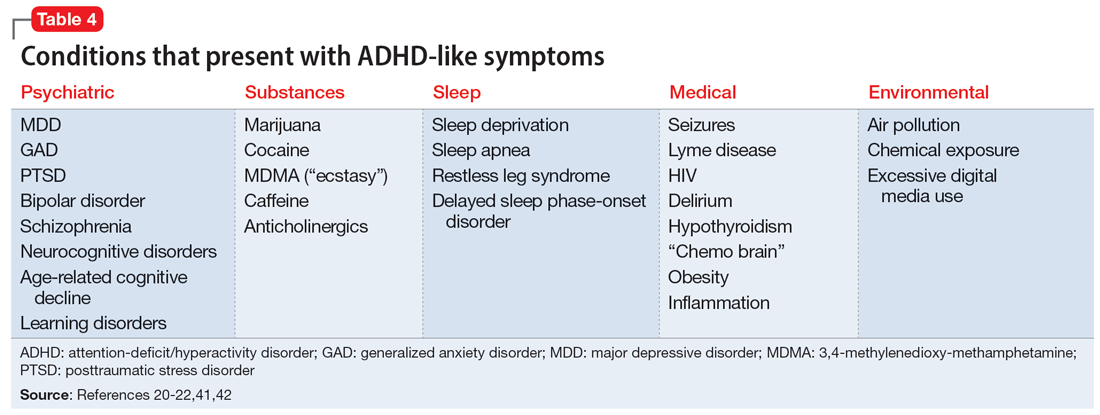

Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are mainly cared for in primary care settings by us. Management of this chronic neurodevelopmental condition that affects 5+% of children worldwide should include proper diagnosis, assessment for contributing and comorbid conditions, behavioral intervention (the primary treatment for preschoolers), ensuring good sleep and nutrition, and usually medication.

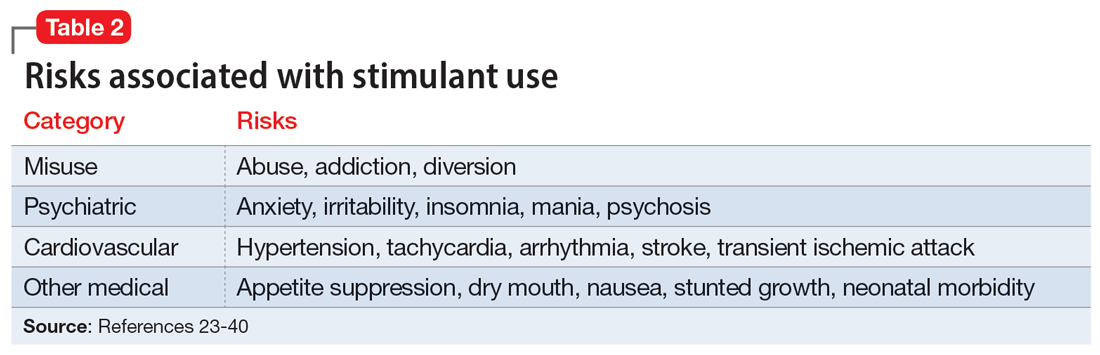

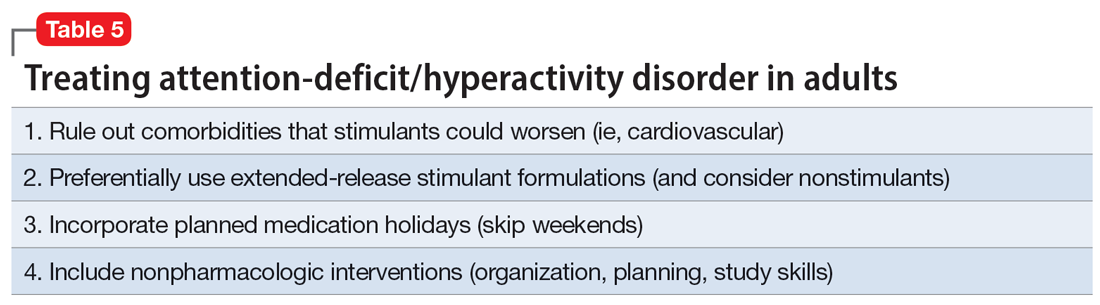

Because stimulants are very effective for reducing ADHD symptoms, we may readily begin these first-line medications even on the initial visit when the diagnosis is determined. But are we really thoughtful about knowing and explaining the potential short- and long-term side effects of these medications that may then be used for many years? Considerable discussion with the child and parents may be needed to address their concerns, balanced with benefits, and to make a plan for their access and use of stimulants (and other medications for ADHD not the topic here).

Consider the Side Effects

In children older than 6 years, some form of either a methylphenidate (MPH) or a dextroamphetamine (DA) class of stimulant have been shown to be equally effective in reducing symptoms of ADHD in about 77% of cases, but side effects are common, mostly mild, and mostly in the first months of use. These include reduced appetite, abdominal pain, headache, weight loss, tics, jitteriness, and delays in falling asleep. About half of all children treated will have one of these adverse effects over 5 years, with reduced appetite the most common. There is no difference in effectiveness or side effects by presentation type, i.e. hyperactive, inattentive, or combined, but the DA forms are associated with more side effects than MPH (10% vs. 6%). Medicated preschoolers have more and different side effects which, in addition to those above, may include listlessness, social withdrawal, and repetitive movements. Fortunately, we can reassure families that side effects can usually be readily managed by slower ramp up of dose, spacing to ensure appetite for meals, extra snacks, attention to bowel patterns and bedtime routines, or change in medication class.

Rates of tics while on stimulants are low irrespective of whether DA or MPH is used, and are usually transient, but difficult cases may occur, sometimes as part of Tourette’s, although not a contraindication. Additional side effects of concern are anxiety, irritability, sadness, and overfocusing that may require a change in class of stimulant or to a nonstimulant. Keep in mind that these symptoms may represent comorbid conditions to ADHD, warranting counseling intervention rather than being a medication side effect. Both initial assessment for ADHD and monitoring should look for comorbidities whether medication is used or not.

Measuring height, weight, pulse, and blood pressure should be part of ADHD care. How concerned should you and the family be about variations? Growth rate declines are more common in preschool children; in the PATS study height varied by 20.3%, and weight by 55.2%, more in heavier children. Growth can be protected by providing favored food for school, encouraging eating when hungry, and an evening fourth meal. You can reassure families that, even with continual use of stimulant medicines for years and initial deficits of 2 cm and 2.7 kg compared to expected, no significant differences remain in adulthood.

This longitudinal growth data was collected when short-acting stimulants were the usual, rather than the now common long-acting stimulants given 7 days per week, however. Children on transdermal MPH with 12-hour release over 3 years showed a small but significant delay in growth with the mean deficit rates 1.3 kg/year mainly in the first year, and 0.68 cm/year in height in the second year. If we see growth not recovering as it is expected to after the first year of treatment, we can advise shorter-acting forms, and medication “holidays” on weekends or vacations, that reduce but do not end the deficits. When concerned, a nonstimulant can be selected.

Blood pressure and pulse rate are predictably slightly increased on stimulants (about 2-4 mm Hg and about 3-6 bpm) but not clinically significantly. Although ECGs are not routinely recommended, careful consideration and consultation is warranted before starting stimulants for any patient with structural cardiac abnormalities, unexplained syncope, exertional chest pain, or a family history of sudden death in children or young adults. Neither current nor former users of stimulants for ADHD were found to have greater rates of cardiac events than the general population, however.

Misuse and abuse

Misuse and diversion of stimulants is common (e.g. 26% diverted MPH in the past month; 14% of 12th graders divert DA), often undetected, and potentially dangerous. And the problem is not limited to just the kids. Sixteen percent of parents reported diversion of stimulant medication to another household member, mainly to themselves. Stimulant overdose can occur, especially taken parenterally, and presents with dilated pupils, tremor, agitation, hyperreflexia, combative behavior, confusion, hallucinations, delirium, anxiety, paranoia, movement disorders, and/or seizures. Fortunately, overdose of prescribed stimulants is rarely fatal if medically managed, but recent “fake” Adderall (not from pharmacies) has been circulating. These fake drugs may contain lethal amounts of fentanyl or methamphetamine. Point out to families that a peer-provided stimulant not prescribed for them may have underlying medical or psychiatric issues that increase adverse events. Selling stimulants can have serious legal implications, with punishments ranging from fines to incarceration. A record of arrest during adolescence increases the likelihood of high school dropout, lack of 4-year college education, and later employment barriers. Besides these serious outcomes, it is useful to remind patients that if they deviate from your recommended dosing that you, and others, will not prescribe for them in the future the medication that has been supporting their successful functioning.

You can be fooled about being able to tell if your patients are misusing or diverting the stimulants you prescribe. Most (59%) physicians suspect that more than one of their patients with ADHD has diverted or feigned symptoms (66%) to get a prescription. Women were less likely to suspect their patients than are men, though, so be vigilant! Child psychiatrists had the highest suspicion with their greater proportion of patients with ADHD plus conduct or substance use disorder, who account for 83% of misusers/diverters. We can use education about misuse, pill counts, contracts on dosing, or switching to long-acting or nonstimulants to curb this.

Additional concerns

With more ADHD diagnosis and stimulants used for many years should we worry about longer-term issues? There have been reports in rodent models and a few children of chromosomal changes with stimulant exposure, but reviewers do not interpret these as an individual cancer risk. Record review of patients who received stimulants showed lower numbers of cancer than expected. Nor is there evidence of reproductive effects of stimulants, although use during pregnancy is not cleared.

Stimulants carry a boxed warning as having high potential for abuse and psychological or physical dependence, which is unsurprising given their effects on brain reward pathways. However, neither past nor present use of stimulants for ADHD has been associated with greater substance use long term.

To top off these issues, recent shortages of stimulants complicate ADHD management. Most states require electronic prescribing, US rules only allowing one transfer of such e-prescriptions. With many pharmacies refusing to tell families about availability, we must make multiple calls to locate a source. Pharmacists could help us by looking up patient names of abusers on the registry and identifying sites with adequate supplies.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are mainly cared for in primary care settings by us. Management of this chronic neurodevelopmental condition that affects 5+% of children worldwide should include proper diagnosis, assessment for contributing and comorbid conditions, behavioral intervention (the primary treatment for preschoolers), ensuring good sleep and nutrition, and usually medication.

Because stimulants are very effective for reducing ADHD symptoms, we may readily begin these first-line medications even on the initial visit when the diagnosis is determined. But are we really thoughtful about knowing and explaining the potential short- and long-term side effects of these medications that may then be used for many years? Considerable discussion with the child and parents may be needed to address their concerns, balanced with benefits, and to make a plan for their access and use of stimulants (and other medications for ADHD not the topic here).

Consider the Side Effects

In children older than 6 years, some form of either a methylphenidate (MPH) or a dextroamphetamine (DA) class of stimulant have been shown to be equally effective in reducing symptoms of ADHD in about 77% of cases, but side effects are common, mostly mild, and mostly in the first months of use. These include reduced appetite, abdominal pain, headache, weight loss, tics, jitteriness, and delays in falling asleep. About half of all children treated will have one of these adverse effects over 5 years, with reduced appetite the most common. There is no difference in effectiveness or side effects by presentation type, i.e. hyperactive, inattentive, or combined, but the DA forms are associated with more side effects than MPH (10% vs. 6%). Medicated preschoolers have more and different side effects which, in addition to those above, may include listlessness, social withdrawal, and repetitive movements. Fortunately, we can reassure families that side effects can usually be readily managed by slower ramp up of dose, spacing to ensure appetite for meals, extra snacks, attention to bowel patterns and bedtime routines, or change in medication class.

Rates of tics while on stimulants are low irrespective of whether DA or MPH is used, and are usually transient, but difficult cases may occur, sometimes as part of Tourette’s, although not a contraindication. Additional side effects of concern are anxiety, irritability, sadness, and overfocusing that may require a change in class of stimulant or to a nonstimulant. Keep in mind that these symptoms may represent comorbid conditions to ADHD, warranting counseling intervention rather than being a medication side effect. Both initial assessment for ADHD and monitoring should look for comorbidities whether medication is used or not.

Measuring height, weight, pulse, and blood pressure should be part of ADHD care. How concerned should you and the family be about variations? Growth rate declines are more common in preschool children; in the PATS study height varied by 20.3%, and weight by 55.2%, more in heavier children. Growth can be protected by providing favored food for school, encouraging eating when hungry, and an evening fourth meal. You can reassure families that, even with continual use of stimulant medicines for years and initial deficits of 2 cm and 2.7 kg compared to expected, no significant differences remain in adulthood.

This longitudinal growth data was collected when short-acting stimulants were the usual, rather than the now common long-acting stimulants given 7 days per week, however. Children on transdermal MPH with 12-hour release over 3 years showed a small but significant delay in growth with the mean deficit rates 1.3 kg/year mainly in the first year, and 0.68 cm/year in height in the second year. If we see growth not recovering as it is expected to after the first year of treatment, we can advise shorter-acting forms, and medication “holidays” on weekends or vacations, that reduce but do not end the deficits. When concerned, a nonstimulant can be selected.

Blood pressure and pulse rate are predictably slightly increased on stimulants (about 2-4 mm Hg and about 3-6 bpm) but not clinically significantly. Although ECGs are not routinely recommended, careful consideration and consultation is warranted before starting stimulants for any patient with structural cardiac abnormalities, unexplained syncope, exertional chest pain, or a family history of sudden death in children or young adults. Neither current nor former users of stimulants for ADHD were found to have greater rates of cardiac events than the general population, however.

Misuse and abuse

Misuse and diversion of stimulants is common (e.g. 26% diverted MPH in the past month; 14% of 12th graders divert DA), often undetected, and potentially dangerous. And the problem is not limited to just the kids. Sixteen percent of parents reported diversion of stimulant medication to another household member, mainly to themselves. Stimulant overdose can occur, especially taken parenterally, and presents with dilated pupils, tremor, agitation, hyperreflexia, combative behavior, confusion, hallucinations, delirium, anxiety, paranoia, movement disorders, and/or seizures. Fortunately, overdose of prescribed stimulants is rarely fatal if medically managed, but recent “fake” Adderall (not from pharmacies) has been circulating. These fake drugs may contain lethal amounts of fentanyl or methamphetamine. Point out to families that a peer-provided stimulant not prescribed for them may have underlying medical or psychiatric issues that increase adverse events. Selling stimulants can have serious legal implications, with punishments ranging from fines to incarceration. A record of arrest during adolescence increases the likelihood of high school dropout, lack of 4-year college education, and later employment barriers. Besides these serious outcomes, it is useful to remind patients that if they deviate from your recommended dosing that you, and others, will not prescribe for them in the future the medication that has been supporting their successful functioning.

You can be fooled about being able to tell if your patients are misusing or diverting the stimulants you prescribe. Most (59%) physicians suspect that more than one of their patients with ADHD has diverted or feigned symptoms (66%) to get a prescription. Women were less likely to suspect their patients than are men, though, so be vigilant! Child psychiatrists had the highest suspicion with their greater proportion of patients with ADHD plus conduct or substance use disorder, who account for 83% of misusers/diverters. We can use education about misuse, pill counts, contracts on dosing, or switching to long-acting or nonstimulants to curb this.

Additional concerns

With more ADHD diagnosis and stimulants used for many years should we worry about longer-term issues? There have been reports in rodent models and a few children of chromosomal changes with stimulant exposure, but reviewers do not interpret these as an individual cancer risk. Record review of patients who received stimulants showed lower numbers of cancer than expected. Nor is there evidence of reproductive effects of stimulants, although use during pregnancy is not cleared.

Stimulants carry a boxed warning as having high potential for abuse and psychological or physical dependence, which is unsurprising given their effects on brain reward pathways. However, neither past nor present use of stimulants for ADHD has been associated with greater substance use long term.

To top off these issues, recent shortages of stimulants complicate ADHD management. Most states require electronic prescribing, US rules only allowing one transfer of such e-prescriptions. With many pharmacies refusing to tell families about availability, we must make multiple calls to locate a source. Pharmacists could help us by looking up patient names of abusers on the registry and identifying sites with adequate supplies.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are mainly cared for in primary care settings by us. Management of this chronic neurodevelopmental condition that affects 5+% of children worldwide should include proper diagnosis, assessment for contributing and comorbid conditions, behavioral intervention (the primary treatment for preschoolers), ensuring good sleep and nutrition, and usually medication.

Because stimulants are very effective for reducing ADHD symptoms, we may readily begin these first-line medications even on the initial visit when the diagnosis is determined. But are we really thoughtful about knowing and explaining the potential short- and long-term side effects of these medications that may then be used for many years? Considerable discussion with the child and parents may be needed to address their concerns, balanced with benefits, and to make a plan for their access and use of stimulants (and other medications for ADHD not the topic here).

Consider the Side Effects

In children older than 6 years, some form of either a methylphenidate (MPH) or a dextroamphetamine (DA) class of stimulant have been shown to be equally effective in reducing symptoms of ADHD in about 77% of cases, but side effects are common, mostly mild, and mostly in the first months of use. These include reduced appetite, abdominal pain, headache, weight loss, tics, jitteriness, and delays in falling asleep. About half of all children treated will have one of these adverse effects over 5 years, with reduced appetite the most common. There is no difference in effectiveness or side effects by presentation type, i.e. hyperactive, inattentive, or combined, but the DA forms are associated with more side effects than MPH (10% vs. 6%). Medicated preschoolers have more and different side effects which, in addition to those above, may include listlessness, social withdrawal, and repetitive movements. Fortunately, we can reassure families that side effects can usually be readily managed by slower ramp up of dose, spacing to ensure appetite for meals, extra snacks, attention to bowel patterns and bedtime routines, or change in medication class.

Rates of tics while on stimulants are low irrespective of whether DA or MPH is used, and are usually transient, but difficult cases may occur, sometimes as part of Tourette’s, although not a contraindication. Additional side effects of concern are anxiety, irritability, sadness, and overfocusing that may require a change in class of stimulant or to a nonstimulant. Keep in mind that these symptoms may represent comorbid conditions to ADHD, warranting counseling intervention rather than being a medication side effect. Both initial assessment for ADHD and monitoring should look for comorbidities whether medication is used or not.

Measuring height, weight, pulse, and blood pressure should be part of ADHD care. How concerned should you and the family be about variations? Growth rate declines are more common in preschool children; in the PATS study height varied by 20.3%, and weight by 55.2%, more in heavier children. Growth can be protected by providing favored food for school, encouraging eating when hungry, and an evening fourth meal. You can reassure families that, even with continual use of stimulant medicines for years and initial deficits of 2 cm and 2.7 kg compared to expected, no significant differences remain in adulthood.

This longitudinal growth data was collected when short-acting stimulants were the usual, rather than the now common long-acting stimulants given 7 days per week, however. Children on transdermal MPH with 12-hour release over 3 years showed a small but significant delay in growth with the mean deficit rates 1.3 kg/year mainly in the first year, and 0.68 cm/year in height in the second year. If we see growth not recovering as it is expected to after the first year of treatment, we can advise shorter-acting forms, and medication “holidays” on weekends or vacations, that reduce but do not end the deficits. When concerned, a nonstimulant can be selected.

Blood pressure and pulse rate are predictably slightly increased on stimulants (about 2-4 mm Hg and about 3-6 bpm) but not clinically significantly. Although ECGs are not routinely recommended, careful consideration and consultation is warranted before starting stimulants for any patient with structural cardiac abnormalities, unexplained syncope, exertional chest pain, or a family history of sudden death in children or young adults. Neither current nor former users of stimulants for ADHD were found to have greater rates of cardiac events than the general population, however.

Misuse and abuse

Misuse and diversion of stimulants is common (e.g. 26% diverted MPH in the past month; 14% of 12th graders divert DA), often undetected, and potentially dangerous. And the problem is not limited to just the kids. Sixteen percent of parents reported diversion of stimulant medication to another household member, mainly to themselves. Stimulant overdose can occur, especially taken parenterally, and presents with dilated pupils, tremor, agitation, hyperreflexia, combative behavior, confusion, hallucinations, delirium, anxiety, paranoia, movement disorders, and/or seizures. Fortunately, overdose of prescribed stimulants is rarely fatal if medically managed, but recent “fake” Adderall (not from pharmacies) has been circulating. These fake drugs may contain lethal amounts of fentanyl or methamphetamine. Point out to families that a peer-provided stimulant not prescribed for them may have underlying medical or psychiatric issues that increase adverse events. Selling stimulants can have serious legal implications, with punishments ranging from fines to incarceration. A record of arrest during adolescence increases the likelihood of high school dropout, lack of 4-year college education, and later employment barriers. Besides these serious outcomes, it is useful to remind patients that if they deviate from your recommended dosing that you, and others, will not prescribe for them in the future the medication that has been supporting their successful functioning.

You can be fooled about being able to tell if your patients are misusing or diverting the stimulants you prescribe. Most (59%) physicians suspect that more than one of their patients with ADHD has diverted or feigned symptoms (66%) to get a prescription. Women were less likely to suspect their patients than are men, though, so be vigilant! Child psychiatrists had the highest suspicion with their greater proportion of patients with ADHD plus conduct or substance use disorder, who account for 83% of misusers/diverters. We can use education about misuse, pill counts, contracts on dosing, or switching to long-acting or nonstimulants to curb this.

Additional concerns

With more ADHD diagnosis and stimulants used for many years should we worry about longer-term issues? There have been reports in rodent models and a few children of chromosomal changes with stimulant exposure, but reviewers do not interpret these as an individual cancer risk. Record review of patients who received stimulants showed lower numbers of cancer than expected. Nor is there evidence of reproductive effects of stimulants, although use during pregnancy is not cleared.

Stimulants carry a boxed warning as having high potential for abuse and psychological or physical dependence, which is unsurprising given their effects on brain reward pathways. However, neither past nor present use of stimulants for ADHD has been associated with greater substance use long term.

To top off these issues, recent shortages of stimulants complicate ADHD management. Most states require electronic prescribing, US rules only allowing one transfer of such e-prescriptions. With many pharmacies refusing to tell families about availability, we must make multiple calls to locate a source. Pharmacists could help us by looking up patient names of abusers on the registry and identifying sites with adequate supplies.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

ADHD Symptoms Linked With Physical Comorbidities

Investigators from the French Health and Medical Research Institute (INSERM), University of Bordeaux, and Charles Perrens Hospital, alongside their Canadian, British, and Swedish counterparts, have shown that attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or attention-deficit disorder without hyperactivity is linked with physical health problems. Cédric Galéra, MD, PhD, child and adolescent psychiatrist and epidemiologist at the Bordeaux Population Health Research Center (INSERM/University of Bordeaux) and the Charles Perrens Hospital, explained these findings to this news organization.

A Bilateral Association

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition that develops in childhood and is characterized by high levels of inattention or agitation and impulsiveness. Some studies have revealed a link between ADHD and medical comorbidities, but these studies were carried out on small patient samples and were cross-sectional.

A new longitudinal study published in Lancet Child and Adolescent Health has shown a reciprocal link between ADHD and physical health problems. The researchers conducted statistical analyses to measure the links between ADHD symptoms and subsequent development of certain physical conditions and, conversely, between physical problems during childhood and subsequent development of ADHD symptoms.

Children From Quebec

The study was conducted by a team headed by Dr. Galéra in collaboration with teams from Britain, Sweden, and Canada. “We studied a Quebec-based cohort of 2000 children aged between 5 months and 17 years,” said Dr. Galéra.

“The researchers in Quebec sent interviewers to question parents at home. And once the children were able to answer for themselves, from adolescence, they were asked to answer the questions directly,” he added.

The children were assessed on the severity of their ADHD symptoms as well as their physical condition (general well-being, any conditions diagnosed, etc.).

Dental Caries, Excess Weight

“We were able to show links between ADHD in childhood and physical health problems in adolescence. There is a greater risk for dental caries, infections, injuries, wounds, sleep disorders, and excess weight.

“Accounting for socioeconomic status and mental health problems such as anxiety and depression or medical treatments, we observed that dental caries, wounds, excess weight, and restless legs syndrome were the conditions that cropped up time and time again,” said Dr. Galéra.

On the other hand, the researchers noted that certain physical health issues in childhood were linked with the onset of ADHD at a later stage. “We discovered that asthma in early childhood, injuries, sleep disturbances, epilepsy, and excess weight were associated with ADHD. Taking all above-referenced features into account, we were left with just wounds and injuries as well as restless legs syndrome as being linked to ADHD,” Dr. Galéra concluded.

For Dr. Galéra, the study illustrates the direction and timing of the links between physical problems and ADHD. “This reflects the link between physical and mental health. It’s important that all healthcare professionals be alert to this. Psychiatrists and mental health professionals must be vigilant about the physical health risks, and pediatricians and family physicians must be aware of the fact that children can present with physical conditions that will later be linked with ADHD. Each of them must be able to refer their young patients to their medical colleagues to ensure that these people receive the best care,” he emphasized.

The team will continue to study this cohort to see which problems emerge in adulthood. They also wish to study the Elfe cohort, a French longitudinal study of children.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators from the French Health and Medical Research Institute (INSERM), University of Bordeaux, and Charles Perrens Hospital, alongside their Canadian, British, and Swedish counterparts, have shown that attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or attention-deficit disorder without hyperactivity is linked with physical health problems. Cédric Galéra, MD, PhD, child and adolescent psychiatrist and epidemiologist at the Bordeaux Population Health Research Center (INSERM/University of Bordeaux) and the Charles Perrens Hospital, explained these findings to this news organization.

A Bilateral Association

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition that develops in childhood and is characterized by high levels of inattention or agitation and impulsiveness. Some studies have revealed a link between ADHD and medical comorbidities, but these studies were carried out on small patient samples and were cross-sectional.

A new longitudinal study published in Lancet Child and Adolescent Health has shown a reciprocal link between ADHD and physical health problems. The researchers conducted statistical analyses to measure the links between ADHD symptoms and subsequent development of certain physical conditions and, conversely, between physical problems during childhood and subsequent development of ADHD symptoms.

Children From Quebec

The study was conducted by a team headed by Dr. Galéra in collaboration with teams from Britain, Sweden, and Canada. “We studied a Quebec-based cohort of 2000 children aged between 5 months and 17 years,” said Dr. Galéra.

“The researchers in Quebec sent interviewers to question parents at home. And once the children were able to answer for themselves, from adolescence, they were asked to answer the questions directly,” he added.

The children were assessed on the severity of their ADHD symptoms as well as their physical condition (general well-being, any conditions diagnosed, etc.).

Dental Caries, Excess Weight

“We were able to show links between ADHD in childhood and physical health problems in adolescence. There is a greater risk for dental caries, infections, injuries, wounds, sleep disorders, and excess weight.

“Accounting for socioeconomic status and mental health problems such as anxiety and depression or medical treatments, we observed that dental caries, wounds, excess weight, and restless legs syndrome were the conditions that cropped up time and time again,” said Dr. Galéra.

On the other hand, the researchers noted that certain physical health issues in childhood were linked with the onset of ADHD at a later stage. “We discovered that asthma in early childhood, injuries, sleep disturbances, epilepsy, and excess weight were associated with ADHD. Taking all above-referenced features into account, we were left with just wounds and injuries as well as restless legs syndrome as being linked to ADHD,” Dr. Galéra concluded.

For Dr. Galéra, the study illustrates the direction and timing of the links between physical problems and ADHD. “This reflects the link between physical and mental health. It’s important that all healthcare professionals be alert to this. Psychiatrists and mental health professionals must be vigilant about the physical health risks, and pediatricians and family physicians must be aware of the fact that children can present with physical conditions that will later be linked with ADHD. Each of them must be able to refer their young patients to their medical colleagues to ensure that these people receive the best care,” he emphasized.

The team will continue to study this cohort to see which problems emerge in adulthood. They also wish to study the Elfe cohort, a French longitudinal study of children.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.