User login

New-AFib risk may not rise with light drinking, may fall with wine

Alcoholic drinks are in the news again, served with a twist. A large cohort study saw a familiar J-shaped curve detailing risk for new atrial fibrillation (AFib) in which the risk rose steadily with greater number of drinks per week, except at the lowest levels of alcohol intake.

There, the curve turned the other way. Light drinkers overall showed no higher AFib risk than nondrinkers, and the risk was lowest at any degree of alcohol intake up to 56 g per week.

On closer analysis of risk patterns, the type of alcoholic beverage mattered.

Alcohol content per drink was defined by standards in the United Kingdom, where the cohort was based.

The risk of AFib also didn’t climb at low intake levels of white wine or with “very low” use of liquor or spirits. But it went up consistently at any level of beer or cider consumption, and to be sure, “high intake of any beverage was associated with greater AF[ib] risk,” notes a report on the study published July 27, 2021, in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The results, based on more than 400,000 adults in the community, “raise the possibility that, for current consumers, drinking red or white wine could potentially be a safer alternative to other types of alcoholic beverages with respect to AF[ib] risk,” the report proposes.

The J-shaped risk curve for new AFib by degree of alcohol consumption follows the pattern sometimes seen for cardiovascular risk in general. But the intake level at which AFib risk is flat or reduced “is at a far lower dose of alcohol than what we’ve seen for cardiovascular disease,” lead author Samuel J. Tu, BHlthMedSc, said in an interview.

“That being said, even with the threshold sitting quite low, it still tells us that cutting down on alcohol is a good thing and perhaps one of the best things for our heart,” said Mr. Tu, University of Adelaide and Royal Adelaide Hospital, who also presented the findings at the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held in Boston and virtually.

How much alcohol is in a drink?

In a caution for anyone looking to beer, wine, or liquor to protect against AFib, or at least not cause it, the weekly number of drinks associated with the lowest AFib risk may be fewer than expected. That bottom of 56 g per week works out to one drink a day or less for British and only four or fewer per week for Americans, according to the study’s internationally varying definitions for the alcohol content of one drink.

For example, a drink was considered to have 8 g of alcohol in the United Kingdom, 14 g in the United States and some other countries, and up to 20 g in Austria. Those numbers came from definitions used by the respective national health agencies, such as the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, Mr. Tu explained.

“They all defined standard drinks slightly differently. But wherever we looked, the threshold we found was far lower than what our governments recommend” based on what is known about alcohol and overall cardiovascular risk, he said.

First to show a hint of protection

The current study “is especially noteworthy because it’s the really the first to demonstrate any hint that there could be a protective effect from any particular amount of alcohol in regard to atrial fibrillation,” Gregory M. Marcus, MD, MAS, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “The J-shaped association fits with what’s been observed with myocardial infarction and overall mortality, and hasn’t previously been seen in the setting of atrial fibrillation.”

Quite interestingly, “it appeared to be the wine drinkers, rather than those who consumed other types of alcohol, that enjoyed this benefit,” said Dr. Marcus, who was not involved in the research but co-authored an accompanying editorial with UCSF colleague Thomas A. Dewland, MD.

“It’s important to recognize the overwhelming evidence that alcohol in general increases the risk for atrial fibrillation,” he said. But “perhaps there’s something in wine that is anti-inflammatory that has some beneficial effect that maybe overwhelms the proarrhythmic aspect.”

The current study “opens the door to the question as to whether there is a small amount of alcohol, perhaps in the form of wine, where there are some benefits that outweigh the risks of atrial fibrillation.”

Still, the findings are observational and “clearly prone to confounding,” Dr. Marcus said. “We need to be very cautious in inferring causality.”

For example, it’s possible that “there is something about individuals that are able to drink alcohol on a regular basis and in small amounts that is the actual causal factor in reducing atrial fibrillation episodes.”

The analysis was based on 403,281 participants in the UK Biobank registry, a prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom, who were aged 40-69 when recruited from 2006 to 2010; it excluded anyone with a history of AFib or who was a former drinker. About 52% were women, the report noted.

Their median alcohol consumption was eight U.K. drinks per week, with 5.5% reporting they had never consumed alcohol. About 21,300 incident cases of AFib or atrial flutter were documented over almost 4.5 million person-years, or a median follow-up of 11.4 years.

The hazard ratio for incident AFib among those with a weekly alcohol consumption corresponding to 1-7 U.K. drinks, compared with intake of less than 1 U.K. drink per week, was 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-1.00). Within that range of 1-7 drinks, the absolute lowest AFib risk on the J curve was at 5 per week.

No increased risk of new AFib was seen in association with weekly U.K. drink levels of 10 for red wine, 8 for white wine, and 3 for spirits.

Compared with weekly intake of less than 1 U.K. drink per week, red wine intake at 1-7 per week showed an HR for AFib of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.91-0.97). Indeed, at no observed consumption level was red wine associated with a significant increase in AFib risk. White wine until the highest observed level of intake, above 28 U.K. drinks per week, at which point the HR for AFib was 1.48 (98% CI 1.19-1.86). The curve for spirit intake followed a similar but steeper curve, its HR risk reaching 1.61 (95% CI, 1.34-1.93) at intake levels beyond 28 U.K. drinks per week.

Consumption of beer or cider showed a linear association with AFib risk, which was elevated at all recorded intake levels, including 8-14 U.K. drinks per week (HR, 1.11; 95% CI 1.06-1.17) and up to 28 or more per week (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.26-1.45).

The analysis is hypothesis generating at best, Dr. Marcus emphasized. “Ultimately, a randomized trial would be the only way to be fairly certain if there is indeed a causal protective relationship between red wine, in low amounts, and atrial fib.”

The message for patients, proposed Dr. Dewland and Dr. Marcus, is that alcohol abstinence is best for secondary AFib prevention, “especially if alcohol is a personal trigger for acute AF[ib] episodes,” and that for primary AFib prevention, “continued consumption of some alcohol may be reasonable, but the exact threshold is unclear and is likely a very low amount.”

Mr. Tu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Marcus disclosed receiving research funding from Baylis Medical; consulting for Johnson & Johnson and InCarda; and holding equity interest in InCarda. Dr. Dewland reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alcoholic drinks are in the news again, served with a twist. A large cohort study saw a familiar J-shaped curve detailing risk for new atrial fibrillation (AFib) in which the risk rose steadily with greater number of drinks per week, except at the lowest levels of alcohol intake.

There, the curve turned the other way. Light drinkers overall showed no higher AFib risk than nondrinkers, and the risk was lowest at any degree of alcohol intake up to 56 g per week.

On closer analysis of risk patterns, the type of alcoholic beverage mattered.

Alcohol content per drink was defined by standards in the United Kingdom, where the cohort was based.

The risk of AFib also didn’t climb at low intake levels of white wine or with “very low” use of liquor or spirits. But it went up consistently at any level of beer or cider consumption, and to be sure, “high intake of any beverage was associated with greater AF[ib] risk,” notes a report on the study published July 27, 2021, in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The results, based on more than 400,000 adults in the community, “raise the possibility that, for current consumers, drinking red or white wine could potentially be a safer alternative to other types of alcoholic beverages with respect to AF[ib] risk,” the report proposes.

The J-shaped risk curve for new AFib by degree of alcohol consumption follows the pattern sometimes seen for cardiovascular risk in general. But the intake level at which AFib risk is flat or reduced “is at a far lower dose of alcohol than what we’ve seen for cardiovascular disease,” lead author Samuel J. Tu, BHlthMedSc, said in an interview.

“That being said, even with the threshold sitting quite low, it still tells us that cutting down on alcohol is a good thing and perhaps one of the best things for our heart,” said Mr. Tu, University of Adelaide and Royal Adelaide Hospital, who also presented the findings at the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held in Boston and virtually.

How much alcohol is in a drink?

In a caution for anyone looking to beer, wine, or liquor to protect against AFib, or at least not cause it, the weekly number of drinks associated with the lowest AFib risk may be fewer than expected. That bottom of 56 g per week works out to one drink a day or less for British and only four or fewer per week for Americans, according to the study’s internationally varying definitions for the alcohol content of one drink.

For example, a drink was considered to have 8 g of alcohol in the United Kingdom, 14 g in the United States and some other countries, and up to 20 g in Austria. Those numbers came from definitions used by the respective national health agencies, such as the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, Mr. Tu explained.

“They all defined standard drinks slightly differently. But wherever we looked, the threshold we found was far lower than what our governments recommend” based on what is known about alcohol and overall cardiovascular risk, he said.

First to show a hint of protection

The current study “is especially noteworthy because it’s the really the first to demonstrate any hint that there could be a protective effect from any particular amount of alcohol in regard to atrial fibrillation,” Gregory M. Marcus, MD, MAS, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “The J-shaped association fits with what’s been observed with myocardial infarction and overall mortality, and hasn’t previously been seen in the setting of atrial fibrillation.”

Quite interestingly, “it appeared to be the wine drinkers, rather than those who consumed other types of alcohol, that enjoyed this benefit,” said Dr. Marcus, who was not involved in the research but co-authored an accompanying editorial with UCSF colleague Thomas A. Dewland, MD.

“It’s important to recognize the overwhelming evidence that alcohol in general increases the risk for atrial fibrillation,” he said. But “perhaps there’s something in wine that is anti-inflammatory that has some beneficial effect that maybe overwhelms the proarrhythmic aspect.”

The current study “opens the door to the question as to whether there is a small amount of alcohol, perhaps in the form of wine, where there are some benefits that outweigh the risks of atrial fibrillation.”

Still, the findings are observational and “clearly prone to confounding,” Dr. Marcus said. “We need to be very cautious in inferring causality.”

For example, it’s possible that “there is something about individuals that are able to drink alcohol on a regular basis and in small amounts that is the actual causal factor in reducing atrial fibrillation episodes.”

The analysis was based on 403,281 participants in the UK Biobank registry, a prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom, who were aged 40-69 when recruited from 2006 to 2010; it excluded anyone with a history of AFib or who was a former drinker. About 52% were women, the report noted.

Their median alcohol consumption was eight U.K. drinks per week, with 5.5% reporting they had never consumed alcohol. About 21,300 incident cases of AFib or atrial flutter were documented over almost 4.5 million person-years, or a median follow-up of 11.4 years.

The hazard ratio for incident AFib among those with a weekly alcohol consumption corresponding to 1-7 U.K. drinks, compared with intake of less than 1 U.K. drink per week, was 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-1.00). Within that range of 1-7 drinks, the absolute lowest AFib risk on the J curve was at 5 per week.

No increased risk of new AFib was seen in association with weekly U.K. drink levels of 10 for red wine, 8 for white wine, and 3 for spirits.

Compared with weekly intake of less than 1 U.K. drink per week, red wine intake at 1-7 per week showed an HR for AFib of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.91-0.97). Indeed, at no observed consumption level was red wine associated with a significant increase in AFib risk. White wine until the highest observed level of intake, above 28 U.K. drinks per week, at which point the HR for AFib was 1.48 (98% CI 1.19-1.86). The curve for spirit intake followed a similar but steeper curve, its HR risk reaching 1.61 (95% CI, 1.34-1.93) at intake levels beyond 28 U.K. drinks per week.

Consumption of beer or cider showed a linear association with AFib risk, which was elevated at all recorded intake levels, including 8-14 U.K. drinks per week (HR, 1.11; 95% CI 1.06-1.17) and up to 28 or more per week (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.26-1.45).

The analysis is hypothesis generating at best, Dr. Marcus emphasized. “Ultimately, a randomized trial would be the only way to be fairly certain if there is indeed a causal protective relationship between red wine, in low amounts, and atrial fib.”

The message for patients, proposed Dr. Dewland and Dr. Marcus, is that alcohol abstinence is best for secondary AFib prevention, “especially if alcohol is a personal trigger for acute AF[ib] episodes,” and that for primary AFib prevention, “continued consumption of some alcohol may be reasonable, but the exact threshold is unclear and is likely a very low amount.”

Mr. Tu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Marcus disclosed receiving research funding from Baylis Medical; consulting for Johnson & Johnson and InCarda; and holding equity interest in InCarda. Dr. Dewland reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alcoholic drinks are in the news again, served with a twist. A large cohort study saw a familiar J-shaped curve detailing risk for new atrial fibrillation (AFib) in which the risk rose steadily with greater number of drinks per week, except at the lowest levels of alcohol intake.

There, the curve turned the other way. Light drinkers overall showed no higher AFib risk than nondrinkers, and the risk was lowest at any degree of alcohol intake up to 56 g per week.

On closer analysis of risk patterns, the type of alcoholic beverage mattered.

Alcohol content per drink was defined by standards in the United Kingdom, where the cohort was based.

The risk of AFib also didn’t climb at low intake levels of white wine or with “very low” use of liquor or spirits. But it went up consistently at any level of beer or cider consumption, and to be sure, “high intake of any beverage was associated with greater AF[ib] risk,” notes a report on the study published July 27, 2021, in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The results, based on more than 400,000 adults in the community, “raise the possibility that, for current consumers, drinking red or white wine could potentially be a safer alternative to other types of alcoholic beverages with respect to AF[ib] risk,” the report proposes.

The J-shaped risk curve for new AFib by degree of alcohol consumption follows the pattern sometimes seen for cardiovascular risk in general. But the intake level at which AFib risk is flat or reduced “is at a far lower dose of alcohol than what we’ve seen for cardiovascular disease,” lead author Samuel J. Tu, BHlthMedSc, said in an interview.

“That being said, even with the threshold sitting quite low, it still tells us that cutting down on alcohol is a good thing and perhaps one of the best things for our heart,” said Mr. Tu, University of Adelaide and Royal Adelaide Hospital, who also presented the findings at the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held in Boston and virtually.

How much alcohol is in a drink?

In a caution for anyone looking to beer, wine, or liquor to protect against AFib, or at least not cause it, the weekly number of drinks associated with the lowest AFib risk may be fewer than expected. That bottom of 56 g per week works out to one drink a day or less for British and only four or fewer per week for Americans, according to the study’s internationally varying definitions for the alcohol content of one drink.

For example, a drink was considered to have 8 g of alcohol in the United Kingdom, 14 g in the United States and some other countries, and up to 20 g in Austria. Those numbers came from definitions used by the respective national health agencies, such as the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, Mr. Tu explained.

“They all defined standard drinks slightly differently. But wherever we looked, the threshold we found was far lower than what our governments recommend” based on what is known about alcohol and overall cardiovascular risk, he said.

First to show a hint of protection

The current study “is especially noteworthy because it’s the really the first to demonstrate any hint that there could be a protective effect from any particular amount of alcohol in regard to atrial fibrillation,” Gregory M. Marcus, MD, MAS, University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “The J-shaped association fits with what’s been observed with myocardial infarction and overall mortality, and hasn’t previously been seen in the setting of atrial fibrillation.”

Quite interestingly, “it appeared to be the wine drinkers, rather than those who consumed other types of alcohol, that enjoyed this benefit,” said Dr. Marcus, who was not involved in the research but co-authored an accompanying editorial with UCSF colleague Thomas A. Dewland, MD.

“It’s important to recognize the overwhelming evidence that alcohol in general increases the risk for atrial fibrillation,” he said. But “perhaps there’s something in wine that is anti-inflammatory that has some beneficial effect that maybe overwhelms the proarrhythmic aspect.”

The current study “opens the door to the question as to whether there is a small amount of alcohol, perhaps in the form of wine, where there are some benefits that outweigh the risks of atrial fibrillation.”

Still, the findings are observational and “clearly prone to confounding,” Dr. Marcus said. “We need to be very cautious in inferring causality.”

For example, it’s possible that “there is something about individuals that are able to drink alcohol on a regular basis and in small amounts that is the actual causal factor in reducing atrial fibrillation episodes.”

The analysis was based on 403,281 participants in the UK Biobank registry, a prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom, who were aged 40-69 when recruited from 2006 to 2010; it excluded anyone with a history of AFib or who was a former drinker. About 52% were women, the report noted.

Their median alcohol consumption was eight U.K. drinks per week, with 5.5% reporting they had never consumed alcohol. About 21,300 incident cases of AFib or atrial flutter were documented over almost 4.5 million person-years, or a median follow-up of 11.4 years.

The hazard ratio for incident AFib among those with a weekly alcohol consumption corresponding to 1-7 U.K. drinks, compared with intake of less than 1 U.K. drink per week, was 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-1.00). Within that range of 1-7 drinks, the absolute lowest AFib risk on the J curve was at 5 per week.

No increased risk of new AFib was seen in association with weekly U.K. drink levels of 10 for red wine, 8 for white wine, and 3 for spirits.

Compared with weekly intake of less than 1 U.K. drink per week, red wine intake at 1-7 per week showed an HR for AFib of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.91-0.97). Indeed, at no observed consumption level was red wine associated with a significant increase in AFib risk. White wine until the highest observed level of intake, above 28 U.K. drinks per week, at which point the HR for AFib was 1.48 (98% CI 1.19-1.86). The curve for spirit intake followed a similar but steeper curve, its HR risk reaching 1.61 (95% CI, 1.34-1.93) at intake levels beyond 28 U.K. drinks per week.

Consumption of beer or cider showed a linear association with AFib risk, which was elevated at all recorded intake levels, including 8-14 U.K. drinks per week (HR, 1.11; 95% CI 1.06-1.17) and up to 28 or more per week (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.26-1.45).

The analysis is hypothesis generating at best, Dr. Marcus emphasized. “Ultimately, a randomized trial would be the only way to be fairly certain if there is indeed a causal protective relationship between red wine, in low amounts, and atrial fib.”

The message for patients, proposed Dr. Dewland and Dr. Marcus, is that alcohol abstinence is best for secondary AFib prevention, “especially if alcohol is a personal trigger for acute AF[ib] episodes,” and that for primary AFib prevention, “continued consumption of some alcohol may be reasonable, but the exact threshold is unclear and is likely a very low amount.”

Mr. Tu has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Marcus disclosed receiving research funding from Baylis Medical; consulting for Johnson & Johnson and InCarda; and holding equity interest in InCarda. Dr. Dewland reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DOACs best aspirin after ventricular ablation: STROKE-VT

Catheter ablation has been around a lot longer for ventricular arrhythmia than for atrial fibrillation, but far less is settled about what antithrombotic therapy should follow ventricular ablations, as there have been no big, randomized trials for guidance.

But the evidence base grew stronger this week, and it favors postprocedure treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over antiplatelet therapy with aspirin for patients undergoing radiofrequency (RF) ablation to treat left ventricular (LV) arrhythmias.

The 30-day risk for ischemic stroke or transient ischemia attack (TIA) was sharply higher for patients who took daily aspirin after RF ablation for ventricular tachycardia (VT) or premature ventricular contractions (PVC) in a multicenter randomized trial.

Those of its 246 patients who received aspirin were also far more likely to show asymptomatic lesions on cerebral MRI scans performed both 24 hours and 30 days after the procedure.

The findings show the importance of DOAC therapy after ventricular ablation procedures, a setting for which there are no evidence-based guidelines, “to mitigate the risk of systemic thromboembolic events,” said Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park. He spoke at a media presentation on the trial, called STROKE-VT, during the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held virtually and on-site in Boston.

The risk for stroke and TIA went up in association with several procedural issues, including some that operators might be able to change in order to reach for better outcomes, Dr. Lakkireddy observed.

“Prolonged radiofrequency ablation times, especially in those with low left ventricle ejection fractions, are definitely higher risk,” as are procedures that involved the retrograde transaortic approach for advancing the ablation catheter, rather than a trans-septal approach.

The retrograde transaortic approach should be avoided in such procedures, “whenever it can be avoided,” said Dr. Lakkireddy, who formally presented STROKE-VT at the HRS sessions and is lead author on its report published about the same time in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The trial has limitations, but “it’s a very important study, and I think that this could become our standard of care for managing anticoagulation after VT and PVC left-sided ablations,” Mina K. Chung, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

How patients are treated with antithrombotics after ventricular ablations can vary widely, sometimes based on the operator’s “subjective feeling of how extensive the ablation is,” Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, not involved in the study, said during the STROKE-VT media briefing.

That’s consistent with the guidelines, which propose oral anticoagulation therapy after more extensive ventricular ablations and antiplatelets when the ablation is more limited – based more on consensus than firm evidence – as described by Jeffrey R. Winterfield, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and Usha Tedrow, MD, MSc, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in an accompanying editorial.

“This is really the first randomized trial data, that I know of, that we have on this. So I do think it will be guideline-influencing,” Dr. Albert said.

“This should change practice,” agreed Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, Duke University, Durham, N.C., also not part of STROKE-VT. “A lot of evidence in the trial is consistent and provides a compelling story, not to mention that, in my opinion, the study probably underestimates the value of DOACs,” he told this news organization.

That’s because patients assigned to DOACs had far longer ablation times, “so their risk was even greater than in the aspirin arm,” Dr. Piccini said. Ablation times averaged 2,095 seconds in the DOAC group, compared with only 1,708 seconds in the aspirin group, probably because the preponderance of VT over PVC ablations for those getting a DOAC was even greater in the aspirin group.

Of the 246 patients assigned to either aspirin or a DOAC, usually a factor Xa inhibitor, 75% had undergone VT ablation and the remainder ablation for PVCs. Their mean age was 60 years and only 18% were women. None had experienced a cerebrovascular event in the previous 3 months.

The 30-day odds ratio for TIA or ischemic stroke in patients who received aspirin, compared with a DOAC, was 12.6 (95% confidence interval, 4.10-39.11; P < .001).

The corresponding OR for asymptomatic cerebral lesions by MRI at 24 hours was 2.15 (95% CI, 1.02-4.54; P = .04) and at 30 days was 3.48 (95% CI, 1.38-8.80; P = .008).

The rate of stroke or TIA was similar in patients who underwent ablation for VT and for PVCs (14% vs. 16%, respectively; P = .70). There were fewer asymptomatic cerebrovascular events by MRI at 24 hours for those undergoing VT ablations (14.7% and 25.8%, respectively; P = .046); but difference between rates attenuated by 30 days (11.4% and 14.5%, respectively; P = .52).

The OR for TIA or stroke associated with the retrograde transaortic approach, performed in about 40% of the patients, compared with the trans-septal approach in the remainder was 2.60 (95% CI, 1.06-6.37; P = .04).

“The study tells us it’s safe and indeed preferable to anticoagulate after an ablation procedure. But the more important finding, perhaps, wasn’t the one related to the core hypothesis. And that was the effect of retrograde access,” Paul A. Friedman, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s formal presentation of the trial.

Whether a ventricular ablation is performed using the retrograde transaortic or trans-septal approach often depends on the location of the ablation targets in the left ventricle. But in some cases it’s a matter of operator preference, Dr. Piccini observed.

“There are some situations where, really, it is better to do retrograde aortic, and there are some cases that are better to do trans-septal. But now there’s going to be a higher burden of proof,” he said. Given the findings of STROKE-VT, operators may need to consider that a ventricular ablation procedure that can be done by the trans-septal route perhaps ought to be consistently done that way.

Dr. Lakkireddy discloses financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and more. Dr. Chung had “nothing relevant to disclose.” Dr. Piccini discloses receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Sanofi, Abbott, ARCA Biopharma, Medtronic, Philips, Biotronik, Allergan, LivaNova, and Myokardia; and research in conjunction with Bayer Healthcare, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Philips. Dr. Friedman discloses conducting research in conjunction with Medtronic and Abbott; holding intellectual property rights with AliveCor, Inference, Medicool, Eko, and Anumana; and receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Boston Scientific. Dr. Winterfield and Dr. Tedrow had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catheter ablation has been around a lot longer for ventricular arrhythmia than for atrial fibrillation, but far less is settled about what antithrombotic therapy should follow ventricular ablations, as there have been no big, randomized trials for guidance.

But the evidence base grew stronger this week, and it favors postprocedure treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over antiplatelet therapy with aspirin for patients undergoing radiofrequency (RF) ablation to treat left ventricular (LV) arrhythmias.

The 30-day risk for ischemic stroke or transient ischemia attack (TIA) was sharply higher for patients who took daily aspirin after RF ablation for ventricular tachycardia (VT) or premature ventricular contractions (PVC) in a multicenter randomized trial.

Those of its 246 patients who received aspirin were also far more likely to show asymptomatic lesions on cerebral MRI scans performed both 24 hours and 30 days after the procedure.

The findings show the importance of DOAC therapy after ventricular ablation procedures, a setting for which there are no evidence-based guidelines, “to mitigate the risk of systemic thromboembolic events,” said Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park. He spoke at a media presentation on the trial, called STROKE-VT, during the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held virtually and on-site in Boston.

The risk for stroke and TIA went up in association with several procedural issues, including some that operators might be able to change in order to reach for better outcomes, Dr. Lakkireddy observed.

“Prolonged radiofrequency ablation times, especially in those with low left ventricle ejection fractions, are definitely higher risk,” as are procedures that involved the retrograde transaortic approach for advancing the ablation catheter, rather than a trans-septal approach.

The retrograde transaortic approach should be avoided in such procedures, “whenever it can be avoided,” said Dr. Lakkireddy, who formally presented STROKE-VT at the HRS sessions and is lead author on its report published about the same time in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The trial has limitations, but “it’s a very important study, and I think that this could become our standard of care for managing anticoagulation after VT and PVC left-sided ablations,” Mina K. Chung, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

How patients are treated with antithrombotics after ventricular ablations can vary widely, sometimes based on the operator’s “subjective feeling of how extensive the ablation is,” Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, not involved in the study, said during the STROKE-VT media briefing.

That’s consistent with the guidelines, which propose oral anticoagulation therapy after more extensive ventricular ablations and antiplatelets when the ablation is more limited – based more on consensus than firm evidence – as described by Jeffrey R. Winterfield, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and Usha Tedrow, MD, MSc, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in an accompanying editorial.

“This is really the first randomized trial data, that I know of, that we have on this. So I do think it will be guideline-influencing,” Dr. Albert said.

“This should change practice,” agreed Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, Duke University, Durham, N.C., also not part of STROKE-VT. “A lot of evidence in the trial is consistent and provides a compelling story, not to mention that, in my opinion, the study probably underestimates the value of DOACs,” he told this news organization.

That’s because patients assigned to DOACs had far longer ablation times, “so their risk was even greater than in the aspirin arm,” Dr. Piccini said. Ablation times averaged 2,095 seconds in the DOAC group, compared with only 1,708 seconds in the aspirin group, probably because the preponderance of VT over PVC ablations for those getting a DOAC was even greater in the aspirin group.

Of the 246 patients assigned to either aspirin or a DOAC, usually a factor Xa inhibitor, 75% had undergone VT ablation and the remainder ablation for PVCs. Their mean age was 60 years and only 18% were women. None had experienced a cerebrovascular event in the previous 3 months.

The 30-day odds ratio for TIA or ischemic stroke in patients who received aspirin, compared with a DOAC, was 12.6 (95% confidence interval, 4.10-39.11; P < .001).

The corresponding OR for asymptomatic cerebral lesions by MRI at 24 hours was 2.15 (95% CI, 1.02-4.54; P = .04) and at 30 days was 3.48 (95% CI, 1.38-8.80; P = .008).

The rate of stroke or TIA was similar in patients who underwent ablation for VT and for PVCs (14% vs. 16%, respectively; P = .70). There were fewer asymptomatic cerebrovascular events by MRI at 24 hours for those undergoing VT ablations (14.7% and 25.8%, respectively; P = .046); but difference between rates attenuated by 30 days (11.4% and 14.5%, respectively; P = .52).

The OR for TIA or stroke associated with the retrograde transaortic approach, performed in about 40% of the patients, compared with the trans-septal approach in the remainder was 2.60 (95% CI, 1.06-6.37; P = .04).

“The study tells us it’s safe and indeed preferable to anticoagulate after an ablation procedure. But the more important finding, perhaps, wasn’t the one related to the core hypothesis. And that was the effect of retrograde access,” Paul A. Friedman, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s formal presentation of the trial.

Whether a ventricular ablation is performed using the retrograde transaortic or trans-septal approach often depends on the location of the ablation targets in the left ventricle. But in some cases it’s a matter of operator preference, Dr. Piccini observed.

“There are some situations where, really, it is better to do retrograde aortic, and there are some cases that are better to do trans-septal. But now there’s going to be a higher burden of proof,” he said. Given the findings of STROKE-VT, operators may need to consider that a ventricular ablation procedure that can be done by the trans-septal route perhaps ought to be consistently done that way.

Dr. Lakkireddy discloses financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and more. Dr. Chung had “nothing relevant to disclose.” Dr. Piccini discloses receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Sanofi, Abbott, ARCA Biopharma, Medtronic, Philips, Biotronik, Allergan, LivaNova, and Myokardia; and research in conjunction with Bayer Healthcare, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Philips. Dr. Friedman discloses conducting research in conjunction with Medtronic and Abbott; holding intellectual property rights with AliveCor, Inference, Medicool, Eko, and Anumana; and receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Boston Scientific. Dr. Winterfield and Dr. Tedrow had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catheter ablation has been around a lot longer for ventricular arrhythmia than for atrial fibrillation, but far less is settled about what antithrombotic therapy should follow ventricular ablations, as there have been no big, randomized trials for guidance.

But the evidence base grew stronger this week, and it favors postprocedure treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over antiplatelet therapy with aspirin for patients undergoing radiofrequency (RF) ablation to treat left ventricular (LV) arrhythmias.

The 30-day risk for ischemic stroke or transient ischemia attack (TIA) was sharply higher for patients who took daily aspirin after RF ablation for ventricular tachycardia (VT) or premature ventricular contractions (PVC) in a multicenter randomized trial.

Those of its 246 patients who received aspirin were also far more likely to show asymptomatic lesions on cerebral MRI scans performed both 24 hours and 30 days after the procedure.

The findings show the importance of DOAC therapy after ventricular ablation procedures, a setting for which there are no evidence-based guidelines, “to mitigate the risk of systemic thromboembolic events,” said Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park. He spoke at a media presentation on the trial, called STROKE-VT, during the Heart Rhythm Society 2021 Scientific Sessions, held virtually and on-site in Boston.

The risk for stroke and TIA went up in association with several procedural issues, including some that operators might be able to change in order to reach for better outcomes, Dr. Lakkireddy observed.

“Prolonged radiofrequency ablation times, especially in those with low left ventricle ejection fractions, are definitely higher risk,” as are procedures that involved the retrograde transaortic approach for advancing the ablation catheter, rather than a trans-septal approach.

The retrograde transaortic approach should be avoided in such procedures, “whenever it can be avoided,” said Dr. Lakkireddy, who formally presented STROKE-VT at the HRS sessions and is lead author on its report published about the same time in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

The trial has limitations, but “it’s a very important study, and I think that this could become our standard of care for managing anticoagulation after VT and PVC left-sided ablations,” Mina K. Chung, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

How patients are treated with antithrombotics after ventricular ablations can vary widely, sometimes based on the operator’s “subjective feeling of how extensive the ablation is,” Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, not involved in the study, said during the STROKE-VT media briefing.

That’s consistent with the guidelines, which propose oral anticoagulation therapy after more extensive ventricular ablations and antiplatelets when the ablation is more limited – based more on consensus than firm evidence – as described by Jeffrey R. Winterfield, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and Usha Tedrow, MD, MSc, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in an accompanying editorial.

“This is really the first randomized trial data, that I know of, that we have on this. So I do think it will be guideline-influencing,” Dr. Albert said.

“This should change practice,” agreed Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, MHS, Duke University, Durham, N.C., also not part of STROKE-VT. “A lot of evidence in the trial is consistent and provides a compelling story, not to mention that, in my opinion, the study probably underestimates the value of DOACs,” he told this news organization.

That’s because patients assigned to DOACs had far longer ablation times, “so their risk was even greater than in the aspirin arm,” Dr. Piccini said. Ablation times averaged 2,095 seconds in the DOAC group, compared with only 1,708 seconds in the aspirin group, probably because the preponderance of VT over PVC ablations for those getting a DOAC was even greater in the aspirin group.

Of the 246 patients assigned to either aspirin or a DOAC, usually a factor Xa inhibitor, 75% had undergone VT ablation and the remainder ablation for PVCs. Their mean age was 60 years and only 18% were women. None had experienced a cerebrovascular event in the previous 3 months.

The 30-day odds ratio for TIA or ischemic stroke in patients who received aspirin, compared with a DOAC, was 12.6 (95% confidence interval, 4.10-39.11; P < .001).

The corresponding OR for asymptomatic cerebral lesions by MRI at 24 hours was 2.15 (95% CI, 1.02-4.54; P = .04) and at 30 days was 3.48 (95% CI, 1.38-8.80; P = .008).

The rate of stroke or TIA was similar in patients who underwent ablation for VT and for PVCs (14% vs. 16%, respectively; P = .70). There were fewer asymptomatic cerebrovascular events by MRI at 24 hours for those undergoing VT ablations (14.7% and 25.8%, respectively; P = .046); but difference between rates attenuated by 30 days (11.4% and 14.5%, respectively; P = .52).

The OR for TIA or stroke associated with the retrograde transaortic approach, performed in about 40% of the patients, compared with the trans-septal approach in the remainder was 2.60 (95% CI, 1.06-6.37; P = .04).

“The study tells us it’s safe and indeed preferable to anticoagulate after an ablation procedure. But the more important finding, perhaps, wasn’t the one related to the core hypothesis. And that was the effect of retrograde access,” Paul A. Friedman, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said as an invited discussant after Dr. Lakkireddy’s formal presentation of the trial.

Whether a ventricular ablation is performed using the retrograde transaortic or trans-septal approach often depends on the location of the ablation targets in the left ventricle. But in some cases it’s a matter of operator preference, Dr. Piccini observed.

“There are some situations where, really, it is better to do retrograde aortic, and there are some cases that are better to do trans-septal. But now there’s going to be a higher burden of proof,” he said. Given the findings of STROKE-VT, operators may need to consider that a ventricular ablation procedure that can be done by the trans-septal route perhaps ought to be consistently done that way.

Dr. Lakkireddy discloses financial relationships with Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and more. Dr. Chung had “nothing relevant to disclose.” Dr. Piccini discloses receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Sanofi, Abbott, ARCA Biopharma, Medtronic, Philips, Biotronik, Allergan, LivaNova, and Myokardia; and research in conjunction with Bayer Healthcare, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Philips. Dr. Friedman discloses conducting research in conjunction with Medtronic and Abbott; holding intellectual property rights with AliveCor, Inference, Medicool, Eko, and Anumana; and receiving honoraria or speaking or consulting fees from Boston Scientific. Dr. Winterfield and Dr. Tedrow had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Even 10 minutes of daily exercise beneficial after ICD implantation

Small increases in daily physical activity are associated with a boost in 1-year survival in patients with heart failure and coronary disease who received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), new research suggests.

“Our study looked at how much exercise was necessary for a better outcome in patients with prior ICD implantation and, for every 10 minutes of exercise, we saw a 1% reduction in the likelihood of death or hospitalization, which is a pretty profound impact on outcome for just a small amount of additional physical activity per day,” lead author Brett Atwater, MD, told this news organization.

“These improvements were achieved outside of a formal cardiac rehabilitation program, suggesting that the benefits of increased physical activity obtained in cardiac rehabilitation programs may also be achievable at home,” he said.

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs have been shown to improve short- and long-term outcomes in patients with heart failure (HF) but continue to be underutilized, especially by women, the elderly, and minorities. Home-based CR could help overcome this limitation but the science behind it is relatively new, noted Dr. Atwater, director of electrophysiology and electrophysiology research, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Fairfax, Va.

As reported in Circulation Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, the study involved 41,731 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 73.5 years) who received an ICD from 2014 to 2016.

ICD heart rate and activity sensor measurements were used to establish a personalized physical activity (PA) threshold for each patient in the first 3 weeks after ICD implantation. Thereafter, the ICD logged PA when the personalized PA threshold was exceeded. The mean baseline PA level was 128.9 minutes/day.

At 3 years’ follow-up, one-quarter of the patients had died and half had been hospitalized for HF. Of the total population, only 3.2% participated in CR.

Compared with nonparticipants, CR participants were more likely to be White (91.0% versus 87.3%), male (75.5% versus 72.2%), and to have diabetes (48.8% versus 44.1%), ischemic heart disease (91.4% versus 82.1%), or congestive heart failure (90.4% versus 83.4%).

CR participants attended a median of 24 sessions, during which time daily PA increased by a mean of 9.7 minutes per day. During the same time, PA decreased by a mean of 1.0 minute per day in non-CR participants (P < .001).

PA levels remained “relatively constant” for the first 36 months of follow-up among CR participants before showing a steep decline, whereas levels gradually declined throughout follow-up among nonparticipants, with a median annual change of –4.5 min/day.

In adjusted analysis, every 10 minutes of increased daily PA was associated with a 1.1% reduced risk for death (hazard ratio, 0.989; 95% confidence interval, 0.979-0.996) and a 1% reduced risk for HF hospitalization (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.986-0.995) at 1-year follow-up (P < .001).

After propensity score was used to match CR participants with nonparticipants by demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and baseline PA level, CR participants had a significantly lower risk for death at 1 year (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.69-0.85). This difference in risk remained at 2- and 3-year follow-ups.

However, when the researchers further adjusted for change in PA during CR or the same time period after device implantation, no differences in mortality were found between CR participants and nonparticipants at 1 year (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.82-1.21) or at 2 or 3 years.

The risk for HF hospitalization did not differ between the two groups in either propensity score model.

Unlike wearable devices, implanted devices “don’t give that type of feedback to patients regarding PA levels – only to providers – and it will be interesting to discover whether providing feedback to patients can motivate them to do more physical activity,” Dr. Atwater commented.

The team is currently enrolling patients in a follow-up trial, in which patients will be given feedback from their ICD “to move these data from an interesting observation to something that can drive outcomes,” he said.

Commenting for this news organization, Melissa Tracy, MD, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said the study reiterates the “profound” underutilization of CR.

“Only about 3% of patients who should have qualified for cardiac rehabilitation actually attended, which is startling considering that it has class 1A level of evidence supporting its use,” she said.

Dr. Tracy, who is also a member of the American College of Cardiology’s Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Section Leadership Council, described the study as “another notch in the belt of positive outcomes supporting the need for cardiac rehabilitation” and emphasizing the importance of a home-based alternative.

“One of the reasons women, minorities, and older patients don’t go to cardiac rehabilitation is they have to get there, rely on someone to drive them, or they have other responsibilities – especially women, who are often primary caretakers of others,” she said. “For women and men, the pressure to get back to work and support their families means they don’t have the luxury to go to cardiac rehabilitation.”

Dr. Tracy noted that home-based CR is covered by CMS until the end of 2021. “An important take-home is for providers and patients to understand that they do have a home-based option,” she stated.

Limitations of the study are that only 24% of patients were women, only 6% were Black, and the results might not be generalizable to patients younger than 65 years, note Dr. Atwater and colleagues. Also, previous implantation might have protected the cohort from experiencing arrhythmic death, and it remains unclear if similar results would be obtained in patients without a previous ICD.

This research was funded through the unrestricted Abbott Medical-Duke Health Strategic Alliance Research Grant. Dr. Atwater receives significant research support from Boston Scientific and Abbott Medical, and modest honoraria from Abbott Medical, Medtronic, and Biotronik. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the paper. Dr. Tracy has created cardiac prevention programs with Virtual Health Partners (VHP) and owns the intellectual property and consults with VHP but receives no monetary compensation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Small increases in daily physical activity are associated with a boost in 1-year survival in patients with heart failure and coronary disease who received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), new research suggests.

“Our study looked at how much exercise was necessary for a better outcome in patients with prior ICD implantation and, for every 10 minutes of exercise, we saw a 1% reduction in the likelihood of death or hospitalization, which is a pretty profound impact on outcome for just a small amount of additional physical activity per day,” lead author Brett Atwater, MD, told this news organization.

“These improvements were achieved outside of a formal cardiac rehabilitation program, suggesting that the benefits of increased physical activity obtained in cardiac rehabilitation programs may also be achievable at home,” he said.

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs have been shown to improve short- and long-term outcomes in patients with heart failure (HF) but continue to be underutilized, especially by women, the elderly, and minorities. Home-based CR could help overcome this limitation but the science behind it is relatively new, noted Dr. Atwater, director of electrophysiology and electrophysiology research, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Fairfax, Va.

As reported in Circulation Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, the study involved 41,731 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 73.5 years) who received an ICD from 2014 to 2016.

ICD heart rate and activity sensor measurements were used to establish a personalized physical activity (PA) threshold for each patient in the first 3 weeks after ICD implantation. Thereafter, the ICD logged PA when the personalized PA threshold was exceeded. The mean baseline PA level was 128.9 minutes/day.

At 3 years’ follow-up, one-quarter of the patients had died and half had been hospitalized for HF. Of the total population, only 3.2% participated in CR.

Compared with nonparticipants, CR participants were more likely to be White (91.0% versus 87.3%), male (75.5% versus 72.2%), and to have diabetes (48.8% versus 44.1%), ischemic heart disease (91.4% versus 82.1%), or congestive heart failure (90.4% versus 83.4%).

CR participants attended a median of 24 sessions, during which time daily PA increased by a mean of 9.7 minutes per day. During the same time, PA decreased by a mean of 1.0 minute per day in non-CR participants (P < .001).

PA levels remained “relatively constant” for the first 36 months of follow-up among CR participants before showing a steep decline, whereas levels gradually declined throughout follow-up among nonparticipants, with a median annual change of –4.5 min/day.

In adjusted analysis, every 10 minutes of increased daily PA was associated with a 1.1% reduced risk for death (hazard ratio, 0.989; 95% confidence interval, 0.979-0.996) and a 1% reduced risk for HF hospitalization (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.986-0.995) at 1-year follow-up (P < .001).

After propensity score was used to match CR participants with nonparticipants by demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and baseline PA level, CR participants had a significantly lower risk for death at 1 year (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.69-0.85). This difference in risk remained at 2- and 3-year follow-ups.

However, when the researchers further adjusted for change in PA during CR or the same time period after device implantation, no differences in mortality were found between CR participants and nonparticipants at 1 year (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.82-1.21) or at 2 or 3 years.

The risk for HF hospitalization did not differ between the two groups in either propensity score model.

Unlike wearable devices, implanted devices “don’t give that type of feedback to patients regarding PA levels – only to providers – and it will be interesting to discover whether providing feedback to patients can motivate them to do more physical activity,” Dr. Atwater commented.

The team is currently enrolling patients in a follow-up trial, in which patients will be given feedback from their ICD “to move these data from an interesting observation to something that can drive outcomes,” he said.

Commenting for this news organization, Melissa Tracy, MD, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said the study reiterates the “profound” underutilization of CR.

“Only about 3% of patients who should have qualified for cardiac rehabilitation actually attended, which is startling considering that it has class 1A level of evidence supporting its use,” she said.

Dr. Tracy, who is also a member of the American College of Cardiology’s Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Section Leadership Council, described the study as “another notch in the belt of positive outcomes supporting the need for cardiac rehabilitation” and emphasizing the importance of a home-based alternative.

“One of the reasons women, minorities, and older patients don’t go to cardiac rehabilitation is they have to get there, rely on someone to drive them, or they have other responsibilities – especially women, who are often primary caretakers of others,” she said. “For women and men, the pressure to get back to work and support their families means they don’t have the luxury to go to cardiac rehabilitation.”

Dr. Tracy noted that home-based CR is covered by CMS until the end of 2021. “An important take-home is for providers and patients to understand that they do have a home-based option,” she stated.

Limitations of the study are that only 24% of patients were women, only 6% were Black, and the results might not be generalizable to patients younger than 65 years, note Dr. Atwater and colleagues. Also, previous implantation might have protected the cohort from experiencing arrhythmic death, and it remains unclear if similar results would be obtained in patients without a previous ICD.

This research was funded through the unrestricted Abbott Medical-Duke Health Strategic Alliance Research Grant. Dr. Atwater receives significant research support from Boston Scientific and Abbott Medical, and modest honoraria from Abbott Medical, Medtronic, and Biotronik. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the paper. Dr. Tracy has created cardiac prevention programs with Virtual Health Partners (VHP) and owns the intellectual property and consults with VHP but receives no monetary compensation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Small increases in daily physical activity are associated with a boost in 1-year survival in patients with heart failure and coronary disease who received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), new research suggests.

“Our study looked at how much exercise was necessary for a better outcome in patients with prior ICD implantation and, for every 10 minutes of exercise, we saw a 1% reduction in the likelihood of death or hospitalization, which is a pretty profound impact on outcome for just a small amount of additional physical activity per day,” lead author Brett Atwater, MD, told this news organization.

“These improvements were achieved outside of a formal cardiac rehabilitation program, suggesting that the benefits of increased physical activity obtained in cardiac rehabilitation programs may also be achievable at home,” he said.

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs have been shown to improve short- and long-term outcomes in patients with heart failure (HF) but continue to be underutilized, especially by women, the elderly, and minorities. Home-based CR could help overcome this limitation but the science behind it is relatively new, noted Dr. Atwater, director of electrophysiology and electrophysiology research, Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Fairfax, Va.

As reported in Circulation Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, the study involved 41,731 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 73.5 years) who received an ICD from 2014 to 2016.

ICD heart rate and activity sensor measurements were used to establish a personalized physical activity (PA) threshold for each patient in the first 3 weeks after ICD implantation. Thereafter, the ICD logged PA when the personalized PA threshold was exceeded. The mean baseline PA level was 128.9 minutes/day.

At 3 years’ follow-up, one-quarter of the patients had died and half had been hospitalized for HF. Of the total population, only 3.2% participated in CR.

Compared with nonparticipants, CR participants were more likely to be White (91.0% versus 87.3%), male (75.5% versus 72.2%), and to have diabetes (48.8% versus 44.1%), ischemic heart disease (91.4% versus 82.1%), or congestive heart failure (90.4% versus 83.4%).

CR participants attended a median of 24 sessions, during which time daily PA increased by a mean of 9.7 minutes per day. During the same time, PA decreased by a mean of 1.0 minute per day in non-CR participants (P < .001).

PA levels remained “relatively constant” for the first 36 months of follow-up among CR participants before showing a steep decline, whereas levels gradually declined throughout follow-up among nonparticipants, with a median annual change of –4.5 min/day.

In adjusted analysis, every 10 minutes of increased daily PA was associated with a 1.1% reduced risk for death (hazard ratio, 0.989; 95% confidence interval, 0.979-0.996) and a 1% reduced risk for HF hospitalization (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.986-0.995) at 1-year follow-up (P < .001).

After propensity score was used to match CR participants with nonparticipants by demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and baseline PA level, CR participants had a significantly lower risk for death at 1 year (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.69-0.85). This difference in risk remained at 2- and 3-year follow-ups.

However, when the researchers further adjusted for change in PA during CR or the same time period after device implantation, no differences in mortality were found between CR participants and nonparticipants at 1 year (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.82-1.21) or at 2 or 3 years.

The risk for HF hospitalization did not differ between the two groups in either propensity score model.

Unlike wearable devices, implanted devices “don’t give that type of feedback to patients regarding PA levels – only to providers – and it will be interesting to discover whether providing feedback to patients can motivate them to do more physical activity,” Dr. Atwater commented.

The team is currently enrolling patients in a follow-up trial, in which patients will be given feedback from their ICD “to move these data from an interesting observation to something that can drive outcomes,” he said.

Commenting for this news organization, Melissa Tracy, MD, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said the study reiterates the “profound” underutilization of CR.

“Only about 3% of patients who should have qualified for cardiac rehabilitation actually attended, which is startling considering that it has class 1A level of evidence supporting its use,” she said.

Dr. Tracy, who is also a member of the American College of Cardiology’s Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Section Leadership Council, described the study as “another notch in the belt of positive outcomes supporting the need for cardiac rehabilitation” and emphasizing the importance of a home-based alternative.

“One of the reasons women, minorities, and older patients don’t go to cardiac rehabilitation is they have to get there, rely on someone to drive them, or they have other responsibilities – especially women, who are often primary caretakers of others,” she said. “For women and men, the pressure to get back to work and support their families means they don’t have the luxury to go to cardiac rehabilitation.”

Dr. Tracy noted that home-based CR is covered by CMS until the end of 2021. “An important take-home is for providers and patients to understand that they do have a home-based option,” she stated.

Limitations of the study are that only 24% of patients were women, only 6% were Black, and the results might not be generalizable to patients younger than 65 years, note Dr. Atwater and colleagues. Also, previous implantation might have protected the cohort from experiencing arrhythmic death, and it remains unclear if similar results would be obtained in patients without a previous ICD.

This research was funded through the unrestricted Abbott Medical-Duke Health Strategic Alliance Research Grant. Dr. Atwater receives significant research support from Boston Scientific and Abbott Medical, and modest honoraria from Abbott Medical, Medtronic, and Biotronik. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the paper. Dr. Tracy has created cardiac prevention programs with Virtual Health Partners (VHP) and owns the intellectual property and consults with VHP but receives no monetary compensation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Direct oral anticoagulants: Competition brought no cost relief

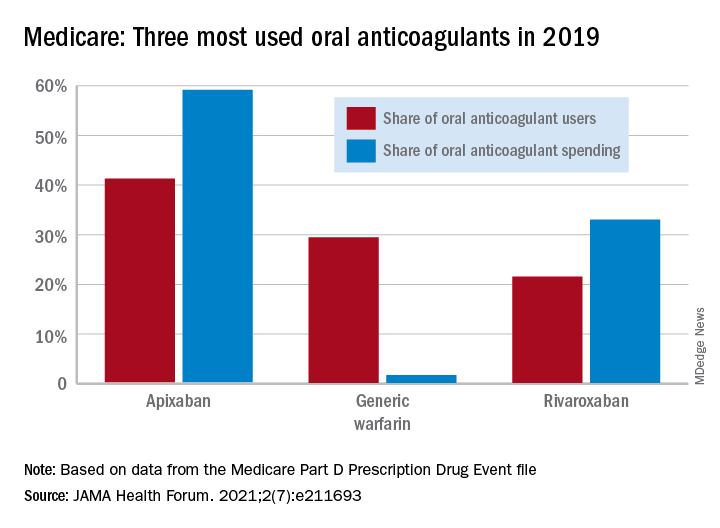

Medicare Part D spending for oral anticoagulants has risen by almost 1,600% since 2011, while the number of users has increased by just 95%, according to a new study.

In 2011, the year after the first direct oral anticoagulant (DOACs) was approved, Medicare Part D spent $0.44 billion on all oral anticoagulants. By 2019, when there a total of four DOACs on the market, spending was $7.38 billion, an increase of 1,577%, Aaron Troy, MD, MPH, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, MAS, said in JAMA Health Forum.

Over that same time, the number of beneficiaries using oral anticoagulants went from 2.68 million to 5.24 million, they said, based on data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event file.

“While higher prices for novel therapeutics like DOACs, which offer clear benefits, such as decreased drug-drug interactions and improved persistence, may partly reflect value and help drive innovation, the patterns and effects of spending on novel medications still merit attention,” they noted.

One pattern of use looked like this: 0.2 million Medicare beneficiaries took DOACs in 2011,compared with 3.5 million in 2019, while the number of warfarin users dropped from 2.48 million to 1.74 million, the investigators reported.

As for spending over the study period, the cost to treat one beneficiary with atrial fibrillation increased by 9.3% each year for apixaban (a DOAC that was the most popular oral anticoagulant in 2019), decreased 27.6% per year for generic warfarin, and increased 9.5% per year for rivaroxaban, said Dr. Troy and Dr. Anderson of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Rising Part D enrollment had an effect on spending growth, as did increased use of oral anticoagulants in general. The introduction of competing DOACs, however, “did not substantially curb annual spending increases, suggesting a lack of price competition, which is consistent with trends observed in other therapeutic categories,” they wrote.

Dr. Anderson has received research grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American College of Cardiology outside of this study and honoraria from Alosa Health. No other disclosures were reported.

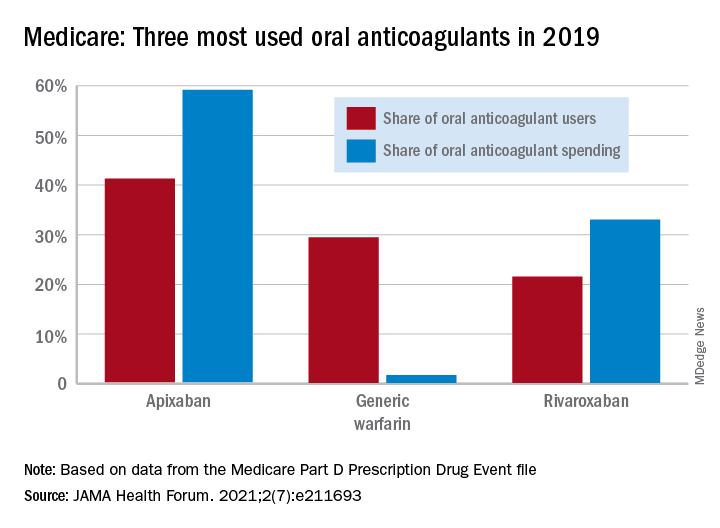

Medicare Part D spending for oral anticoagulants has risen by almost 1,600% since 2011, while the number of users has increased by just 95%, according to a new study.

In 2011, the year after the first direct oral anticoagulant (DOACs) was approved, Medicare Part D spent $0.44 billion on all oral anticoagulants. By 2019, when there a total of four DOACs on the market, spending was $7.38 billion, an increase of 1,577%, Aaron Troy, MD, MPH, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, MAS, said in JAMA Health Forum.

Over that same time, the number of beneficiaries using oral anticoagulants went from 2.68 million to 5.24 million, they said, based on data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event file.

“While higher prices for novel therapeutics like DOACs, which offer clear benefits, such as decreased drug-drug interactions and improved persistence, may partly reflect value and help drive innovation, the patterns and effects of spending on novel medications still merit attention,” they noted.

One pattern of use looked like this: 0.2 million Medicare beneficiaries took DOACs in 2011,compared with 3.5 million in 2019, while the number of warfarin users dropped from 2.48 million to 1.74 million, the investigators reported.

As for spending over the study period, the cost to treat one beneficiary with atrial fibrillation increased by 9.3% each year for apixaban (a DOAC that was the most popular oral anticoagulant in 2019), decreased 27.6% per year for generic warfarin, and increased 9.5% per year for rivaroxaban, said Dr. Troy and Dr. Anderson of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Rising Part D enrollment had an effect on spending growth, as did increased use of oral anticoagulants in general. The introduction of competing DOACs, however, “did not substantially curb annual spending increases, suggesting a lack of price competition, which is consistent with trends observed in other therapeutic categories,” they wrote.

Dr. Anderson has received research grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American College of Cardiology outside of this study and honoraria from Alosa Health. No other disclosures were reported.

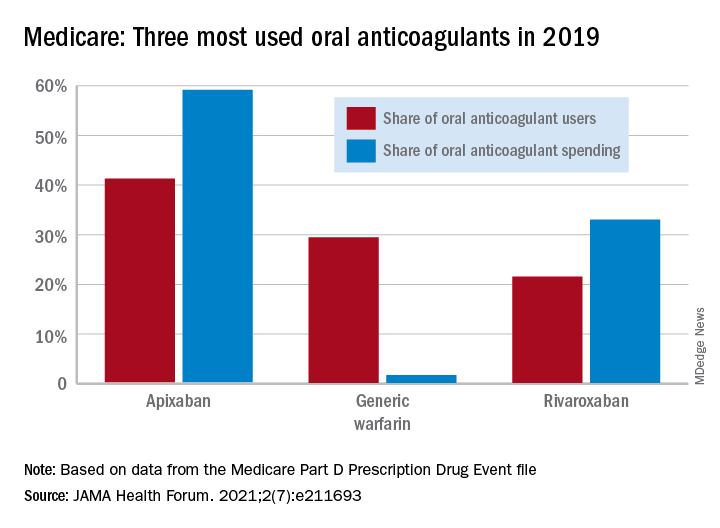

Medicare Part D spending for oral anticoagulants has risen by almost 1,600% since 2011, while the number of users has increased by just 95%, according to a new study.

In 2011, the year after the first direct oral anticoagulant (DOACs) was approved, Medicare Part D spent $0.44 billion on all oral anticoagulants. By 2019, when there a total of four DOACs on the market, spending was $7.38 billion, an increase of 1,577%, Aaron Troy, MD, MPH, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, MAS, said in JAMA Health Forum.

Over that same time, the number of beneficiaries using oral anticoagulants went from 2.68 million to 5.24 million, they said, based on data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event file.

“While higher prices for novel therapeutics like DOACs, which offer clear benefits, such as decreased drug-drug interactions and improved persistence, may partly reflect value and help drive innovation, the patterns and effects of spending on novel medications still merit attention,” they noted.

One pattern of use looked like this: 0.2 million Medicare beneficiaries took DOACs in 2011,compared with 3.5 million in 2019, while the number of warfarin users dropped from 2.48 million to 1.74 million, the investigators reported.

As for spending over the study period, the cost to treat one beneficiary with atrial fibrillation increased by 9.3% each year for apixaban (a DOAC that was the most popular oral anticoagulant in 2019), decreased 27.6% per year for generic warfarin, and increased 9.5% per year for rivaroxaban, said Dr. Troy and Dr. Anderson of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Rising Part D enrollment had an effect on spending growth, as did increased use of oral anticoagulants in general. The introduction of competing DOACs, however, “did not substantially curb annual spending increases, suggesting a lack of price competition, which is consistent with trends observed in other therapeutic categories,” they wrote.

Dr. Anderson has received research grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American College of Cardiology outside of this study and honoraria from Alosa Health. No other disclosures were reported.

FROM JAMA HEALTH FORUM

Dissolving pacemaker impressive in early research

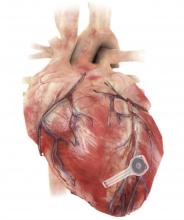

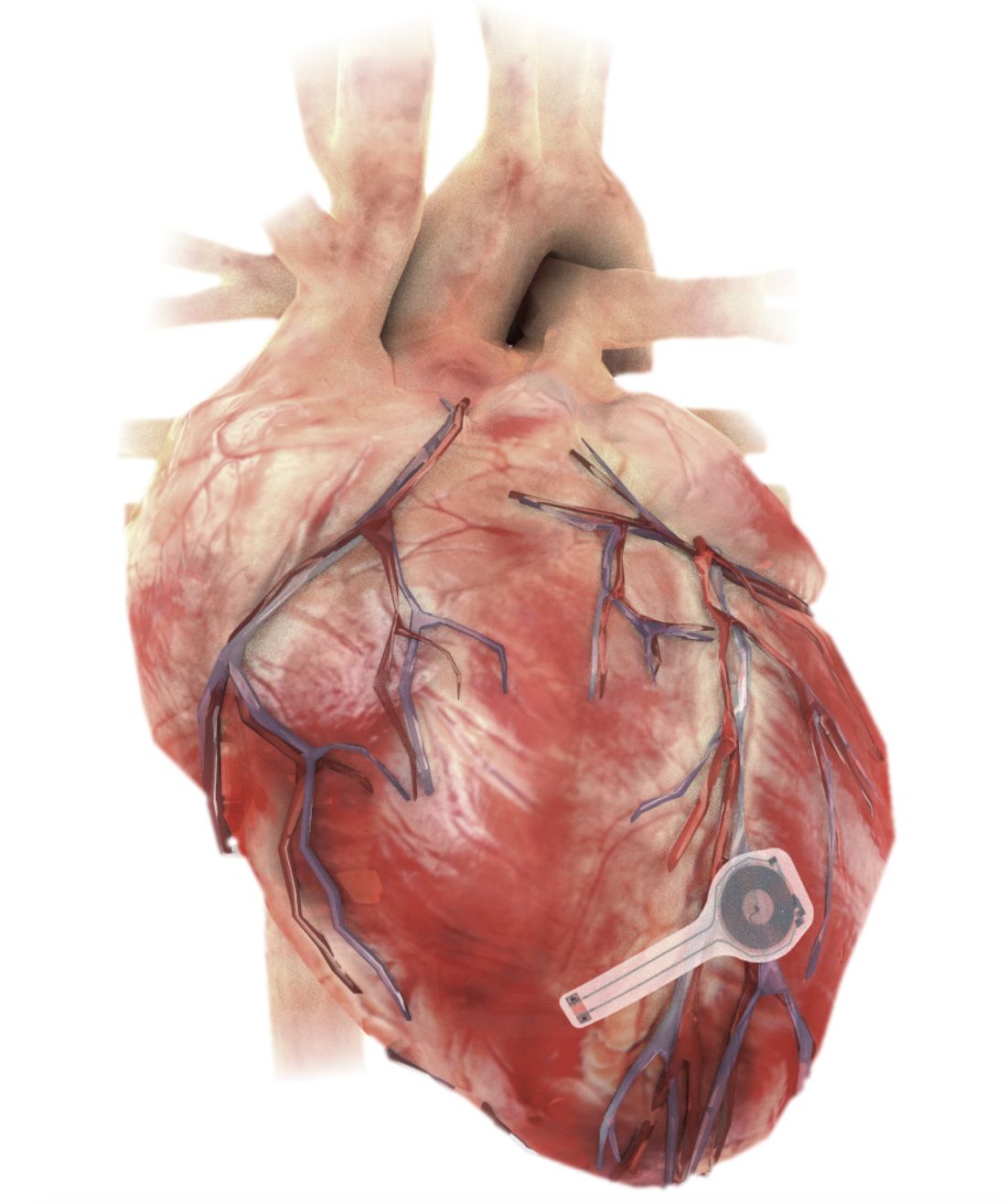

A fully implantable, bioresorbable pacemaker has been developed that’s capable of sustaining heart rhythms in animal and human donor hearts before disappearing over 5-7 weeks.

Temporary pacing devices are frequently used after cardiac surgery but rely on bulky external generators and transcutaneous pacing leads that run the risk of becoming infected or dislodged and can damage the heart when removed if they’re enveloped in fibrotic tissue.

The experimental device is thin, powered without leads or batteries, and made of water-soluble, biocompatible materials, thereby bypassing many of the disadvantages of conventional temporary pacing devices, according to John A. Rogers, PhD, who led the device’s development and directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“The total material load on the body is very minimal,” he said in an interview. “The amount of silicon and magnesium in a multivitamin tablet is about 3,000 times more than the amount of those materials in our electronics. So you can think of them as a very tiny vitamin pill, in a sense, but configured with electronic functionality.”

Dr. Rogers and his team have a reputation for innovation in bioelectronic medicine, having recently constructed transient wireless devices to accelerate neuroregeneration associated with damaged peripheral nerves, to monitor critically ill neonates, and to detect early signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Shortly after Dr. Rogers joined Northwestern, Rishi Arora, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern, reached out to discuss how they could leverage wireless electronics for patients needing temporary pacing.

“It was a natural marriage,” Dr. Arora said in an interview. “Part of the reason to go into the heart was because the cardiology group here at Northwestern, especially on the electrophysiology side, has been very involved in translational research, and John also had a very strong collaboration before he came here with Igor Efimov, [PhD, of George Washington University, Washington], a giant in the field in terms of heart rhythm research.”

Dr. Arora noted that the incidence of temporary pacing after cardiac surgery is at least 10% but can reach 20%. Current devices work well in most patients, but temporary pacing with epicardial wires can cause complications and, typically, work well only for a few days after cardiac surgery. Clinically, though, several patients need postoperative pacing support for 1-2 weeks.

“So if something like this were available where you could tack it onto the surface and forget it for a week or 10 days or 2 weeks, you’d be doing those 20% of patients a huge service,” he said.

Bioresorbable scaffold déjà vu?

The philosophy of “leave nothing behind” is nothing new in cardiology, with bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) gaining initial support as a potential solution to neoatherosclerosis and late-stent thrombosis in permanent metal stents. Failure to show advantages, and safety concerns such as in-scaffold thrombosis, however, led Abbott to stop global sales of the first approved BVS and Boston Scientific to halt its BVS program in 2017.

The wireless pacemaker, however, is an electrical device, not a mechanical one, observed Dr. Rogers. “The fact that it’s not in the bloodstream greatly lowers risks and, as I mentioned before, everything is super thin, low-mass quantities of materials. So, I guess there’s a relationship there, but it’s different in a couple of very important ways.”

As Dr. Rogers, Dr. Arora, Dr. Efimov, and colleagues recently reported in Nature Biotechnology, the electronic part of the pacemaker contains three layers: A loop antenna with a bilayer tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil, a radiofrequency PIN diode based on a monocrystalline silicon nanomembrane, and a poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) dielectric interlayer.

The electronic components rest between two encapsulation layers of PLGA to isolate the active materials from the surrounding biofluids during implantation, and connect to a pair of flexible extension electrodes that deliver the electrical stimuli to a contact pad sutured onto the heart. The entire system is about 16 mm in width and 15 mm in length, and weighs in at about 0.3 g.

The pacemaker receives power and control commands through a wireless inductive power transfer – the same technology used in implanted medical devices, smartphones, and radio-frequency identification tags – between the receiver coil in the device and a wand-shaped, external transmission coil placed on top of or within a few inches of the heart.

“Right now we’re almost at 15 inches, which I think is a very respectable distance for this particular piece of hardware, and clinically very doable,” observed Dr. Arora.

Competing considerations

Testing thus far shows effective ventricular capture across a range of frequencies in mouse and rabbit hearts and successful pacing and activation of human cardiac tissue.

In vivo tests in dogs also suggest that the system can “achieve the power necessary for operation of bioresorbable pacemakers in adult human patients,” the authors say.

Electrodes placed on the dogs’ legs showed a change in ECG signals from a narrow QRS complex (consistent with a normal rate sinus rhythm of 350-400 bpm) to a widened QRS complex with a shortened R-R interval (consistent with a paced rhythm of 400-450 bpm) – indicating successful ventricular capture.

The device successfully paced the dogs through postoperative day 4 but couldn’t provide enough energy to capture the ventricular myocardium on day 5 and failed to pace the heart on day 6, even when transmitting voltages were increased from 1 Vpp to more than 10 Vpp.

Dr. Rogers pointed out that a transient device of theirs that uses very thin films of silica provides stable intracranial pressure monitoring for traumatic brain injury recovery for 3 weeks before dissolving. The problem with the polymers used as encapsulating layers in the pacemaker is that even if they haven’t completely dissolved, there’s a finite rate of water permeation through the film.

“It turns out that’s what’s become the limiting factor, rather than the chemistry of bioresorption,” he said. “So, what we’re seeing with these devices beginning to degrade electrically in terms of performance around 5-6 days is due to that water permeation.”

Although it is not part of the current study, there’s no reason thin silica layers couldn’t be incorporated into the pacemaker to make it less water permeable, Dr. Rogers said. Still, this will have to be weighed against the competing consideration of stable operating life.

The researchers specifically chose materials that would naturally bioresorb via hydrolysis and metabolic action in the body. PLGA degrades into glycolic and lactic acid, the tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil into Wox and Mg(OH)2, and the silicon nanomembrane radiofrequency PIN diode into Si(OH)4.

CT imaging in rat models shows the device is enveloped in fibrotic tissue and completely decouples from the heart at 4 weeks, while images of explanted devices suggest the pacemaker largely dissolves within 3 weeks and the remaining residues disappear after 12 weeks.

The researchers have started an investigational device exemption process to allow the device to be used in clinical trials, and they plan to dig deeper into the potential for fragments to form at various stages of resorption, which some imaging suggests may occur.

“Because these devices are made out of pure materials and they’re in a heterogeneous environment, both mechanically and biomechanically, the devices don’t resorb in a perfectly uniform way and, as a result, at the tail end of the process you can end up with small fragments that eventually bioresorb, but before they’re gone, they are potentially mobile within the body cavity,” Dr. Rogers said.

“We feel that because the devices aren’t in the bloodstream, the risk associated with those fragments is probably manageable but at the same time, these are the sorts of details that must be thoroughly addressed before trials in humans,” he said, adding that one solution, if needed, would be to encapsulate the entire device in a thin bioresorbable hydrogel as a containment vehicle.

Dr. Arora said they hope the pacemaker “will make patients’ lives a lot easier in the postoperative setting but, even there, I think one must remember current pacing technology in this setting is actually very good. So there’s a word of caution not to get ahead of ourselves.”