User login

Early emollient bathing is tied to the development of atopic dermatitis by 2 years of age

Key clinical point: Emollient bathing at 2 months is significantly associated with the development of atopic dermatitis (AD) by 2 years of age.

Major finding: The odds of developing AD were significantly higher among infants who had emollient baths and frequent (> 1 time weekly) emollient application at 2 months of age compared with infants who had neither at 6 months (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.74; P = .038), 12 months (aOR 2.59; P < .001), and 24 months (aOR 1.87; P = .009) of age.

Study details: Findings are from a secondary analysis of the observational Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study and included 1505 healthy firstborn term infants who did or did not receive emollient baths and did or did not have emollients applied frequently at 2 months of age.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Science Foundation Ireland and Johnson & Johnson Santé Beauté France. J O’B Hourihane declared receiving research funding, speaker fees, and consulting fees from various sources.

Source: O'Connor C et al. Early emollient bathing is associated with subsequent atopic dermatitis in an unselected birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2023;34(7):e13998 (Jul 18). doi: 10.1111/pai.13998

Key clinical point: Emollient bathing at 2 months is significantly associated with the development of atopic dermatitis (AD) by 2 years of age.

Major finding: The odds of developing AD were significantly higher among infants who had emollient baths and frequent (> 1 time weekly) emollient application at 2 months of age compared with infants who had neither at 6 months (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.74; P = .038), 12 months (aOR 2.59; P < .001), and 24 months (aOR 1.87; P = .009) of age.

Study details: Findings are from a secondary analysis of the observational Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study and included 1505 healthy firstborn term infants who did or did not receive emollient baths and did or did not have emollients applied frequently at 2 months of age.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Science Foundation Ireland and Johnson & Johnson Santé Beauté France. J O’B Hourihane declared receiving research funding, speaker fees, and consulting fees from various sources.

Source: O'Connor C et al. Early emollient bathing is associated with subsequent atopic dermatitis in an unselected birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2023;34(7):e13998 (Jul 18). doi: 10.1111/pai.13998

Key clinical point: Emollient bathing at 2 months is significantly associated with the development of atopic dermatitis (AD) by 2 years of age.

Major finding: The odds of developing AD were significantly higher among infants who had emollient baths and frequent (> 1 time weekly) emollient application at 2 months of age compared with infants who had neither at 6 months (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.74; P = .038), 12 months (aOR 2.59; P < .001), and 24 months (aOR 1.87; P = .009) of age.

Study details: Findings are from a secondary analysis of the observational Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study and included 1505 healthy firstborn term infants who did or did not receive emollient baths and did or did not have emollients applied frequently at 2 months of age.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Science Foundation Ireland and Johnson & Johnson Santé Beauté France. J O’B Hourihane declared receiving research funding, speaker fees, and consulting fees from various sources.

Source: O'Connor C et al. Early emollient bathing is associated with subsequent atopic dermatitis in an unselected birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2023;34(7):e13998 (Jul 18). doi: 10.1111/pai.13998

Cannabis use is more prevalent in patients with atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: The likelihood of using cannabis was significantly higher, whereas that of using e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes was significantly lower, in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs control individuals without AD were significantly more likely to use cannabis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.49; P < .01) but less likely to use e-cigarettes (aOR 0.71; P < .01) and regular cigarettes (aOR 0.65; P < .01). No significant association was observed between AD and hallucinogen (P = .60), opioid (P = .07), and stimulant (P = .20) use.

Study details: This nested case-control study included 13,756 patients with AD and 55,024 age-, race/ethnicity-, and sex-matched control individuals without AD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Joshi TP et al. Association of atopic dermatitis with substance use disorders: A case-control study in the All of Us Research Program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 13). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.051

Key clinical point: The likelihood of using cannabis was significantly higher, whereas that of using e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes was significantly lower, in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs control individuals without AD were significantly more likely to use cannabis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.49; P < .01) but less likely to use e-cigarettes (aOR 0.71; P < .01) and regular cigarettes (aOR 0.65; P < .01). No significant association was observed between AD and hallucinogen (P = .60), opioid (P = .07), and stimulant (P = .20) use.

Study details: This nested case-control study included 13,756 patients with AD and 55,024 age-, race/ethnicity-, and sex-matched control individuals without AD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Joshi TP et al. Association of atopic dermatitis with substance use disorders: A case-control study in the All of Us Research Program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 13). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.051

Key clinical point: The likelihood of using cannabis was significantly higher, whereas that of using e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes was significantly lower, in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs control individuals without AD were significantly more likely to use cannabis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.49; P < .01) but less likely to use e-cigarettes (aOR 0.71; P < .01) and regular cigarettes (aOR 0.65; P < .01). No significant association was observed between AD and hallucinogen (P = .60), opioid (P = .07), and stimulant (P = .20) use.

Study details: This nested case-control study included 13,756 patients with AD and 55,024 age-, race/ethnicity-, and sex-matched control individuals without AD.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Joshi TP et al. Association of atopic dermatitis with substance use disorders: A case-control study in the All of Us Research Program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 13). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.06.051

Abrocitinib is safe and effective against difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis in daily practice

Key clinical point: Switching to abrocitinib after failing to respond to other Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKs) or biologics improved clinical outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD), without compromising safety.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 28 weeks, abrocitinib led to a significant decrease in median Eczema Area and Severity Index and Investigator’s Global Assessment scores (both P < .0001). At least one adverse event, generally mild, occurred in 60.9% of patients.

Study details: This prospective observational study included 41 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD previously treated with conventional immunosuppressants, targeted therapies, or both, with most having failed to respond with biologics or other JAKi; the patients received 100 mg or 200 mg abrocitinib once daily.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. D Hijnen declared serving as an investigator and consultant for various organizations. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Olydam JI et al. Real-world effectiveness of abrocitinib treatment in patients with difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19378

Key clinical point: Switching to abrocitinib after failing to respond to other Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKs) or biologics improved clinical outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD), without compromising safety.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 28 weeks, abrocitinib led to a significant decrease in median Eczema Area and Severity Index and Investigator’s Global Assessment scores (both P < .0001). At least one adverse event, generally mild, occurred in 60.9% of patients.

Study details: This prospective observational study included 41 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD previously treated with conventional immunosuppressants, targeted therapies, or both, with most having failed to respond with biologics or other JAKi; the patients received 100 mg or 200 mg abrocitinib once daily.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. D Hijnen declared serving as an investigator and consultant for various organizations. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Olydam JI et al. Real-world effectiveness of abrocitinib treatment in patients with difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19378

Key clinical point: Switching to abrocitinib after failing to respond to other Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKs) or biologics improved clinical outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD), without compromising safety.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 28 weeks, abrocitinib led to a significant decrease in median Eczema Area and Severity Index and Investigator’s Global Assessment scores (both P < .0001). At least one adverse event, generally mild, occurred in 60.9% of patients.

Study details: This prospective observational study included 41 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD previously treated with conventional immunosuppressants, targeted therapies, or both, with most having failed to respond with biologics or other JAKi; the patients received 100 mg or 200 mg abrocitinib once daily.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. D Hijnen declared serving as an investigator and consultant for various organizations. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Olydam JI et al. Real-world effectiveness of abrocitinib treatment in patients with difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Jul 21). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19378

Continuous upadacitinib treatment required to maintain skin clearance in atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Interruption of upadacitinib treatment caused rapid loss of skin clearance response and upadacitinib retreatment led to rapid recovery or improvement in the response in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: A dose of 30 mg upadacitinib vs placebo led to a 72.9% least-squares mean percentage improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score by week 16, which decreased to 24.6% within 4 weeks of upadacitinib withdrawal; however, an 8-week rescue therapy (30 mg upadacitinib) improved the mean percentage EASI score (pre- vs post-therapy: 2.8% vs 84.7%).

Study details: This post hoc analysis of a phase 2b study included 167 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive upadacitinib (7.5, 15, or 30 mg) or placebo; at week 16, each group was reassigned to receive upadacitinib (same dose) or placebo, with rescue therapy (30 mg upadacitinib) initiated in those with < 50% EASI response at week 20.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by AbbVie, Inc. Six authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in AbbVie. Several authors reported ties with AbbVie and others.

Source: Guttman-Yassky E et al. Upadacitinib treatment withdrawal and retreatment in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results from a phase 2b, randomized, controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Aug 1). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19391

Key clinical point: Interruption of upadacitinib treatment caused rapid loss of skin clearance response and upadacitinib retreatment led to rapid recovery or improvement in the response in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: A dose of 30 mg upadacitinib vs placebo led to a 72.9% least-squares mean percentage improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score by week 16, which decreased to 24.6% within 4 weeks of upadacitinib withdrawal; however, an 8-week rescue therapy (30 mg upadacitinib) improved the mean percentage EASI score (pre- vs post-therapy: 2.8% vs 84.7%).

Study details: This post hoc analysis of a phase 2b study included 167 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive upadacitinib (7.5, 15, or 30 mg) or placebo; at week 16, each group was reassigned to receive upadacitinib (same dose) or placebo, with rescue therapy (30 mg upadacitinib) initiated in those with < 50% EASI response at week 20.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by AbbVie, Inc. Six authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in AbbVie. Several authors reported ties with AbbVie and others.

Source: Guttman-Yassky E et al. Upadacitinib treatment withdrawal and retreatment in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results from a phase 2b, randomized, controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Aug 1). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19391

Key clinical point: Interruption of upadacitinib treatment caused rapid loss of skin clearance response and upadacitinib retreatment led to rapid recovery or improvement in the response in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: A dose of 30 mg upadacitinib vs placebo led to a 72.9% least-squares mean percentage improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score by week 16, which decreased to 24.6% within 4 weeks of upadacitinib withdrawal; however, an 8-week rescue therapy (30 mg upadacitinib) improved the mean percentage EASI score (pre- vs post-therapy: 2.8% vs 84.7%).

Study details: This post hoc analysis of a phase 2b study included 167 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive upadacitinib (7.5, 15, or 30 mg) or placebo; at week 16, each group was reassigned to receive upadacitinib (same dose) or placebo, with rescue therapy (30 mg upadacitinib) initiated in those with < 50% EASI response at week 20.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by AbbVie, Inc. Six authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in AbbVie. Several authors reported ties with AbbVie and others.

Source: Guttman-Yassky E et al. Upadacitinib treatment withdrawal and retreatment in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results from a phase 2b, randomized, controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 (Aug 1). doi: 10.1111/jdv.19391

Amlitelimab is effective and well-tolerated in atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical therapies

Key clinical point: Amlitelimab is well-tolerated and improves disease signs and symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that is inadequately controlled by topical therapies.

Major finding: At week 16, the least-squares mean percentage change in Eczema Area and Severity Index score was significantly higher in low-dose (−80.12%; P = .009) and high-dose (−69.97%; P = .072) amlitelimab groups vs the placebo group (−49.37%). Overall, 62%, 47%, and 69% of patients reported ≥1 treatment-emergent adverse events with low- and high-dose amlitelimab and placebo groups, respectively.

Study details: This phase 2a study included 88 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD and inadequate response to or inadvisability of topical treatments who were randomly assigned to receive low-dose (200 mg) or high-dose (500 mg) amlitelimab or placebo, followed by maintenance doses every 4 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Kymab Ltd., a Sanofi company. Some authors declared receiving research grants or consultancy fees or other ties with various sources, including Kymab and Sanofi. Six authors declared being employees or stockholders of Kymab or Sanofi.

Source: Weidinger S et al. Safety and efficacy of amlitelimab, a fully human, non-depleting, non-cytotoxic anti-OX40Ligand monoclonal antibody, in atopic dermatitis: Results of a phase IIa randomised placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 18). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad240

Key clinical point: Amlitelimab is well-tolerated and improves disease signs and symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that is inadequately controlled by topical therapies.

Major finding: At week 16, the least-squares mean percentage change in Eczema Area and Severity Index score was significantly higher in low-dose (−80.12%; P = .009) and high-dose (−69.97%; P = .072) amlitelimab groups vs the placebo group (−49.37%). Overall, 62%, 47%, and 69% of patients reported ≥1 treatment-emergent adverse events with low- and high-dose amlitelimab and placebo groups, respectively.

Study details: This phase 2a study included 88 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD and inadequate response to or inadvisability of topical treatments who were randomly assigned to receive low-dose (200 mg) or high-dose (500 mg) amlitelimab or placebo, followed by maintenance doses every 4 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Kymab Ltd., a Sanofi company. Some authors declared receiving research grants or consultancy fees or other ties with various sources, including Kymab and Sanofi. Six authors declared being employees or stockholders of Kymab or Sanofi.

Source: Weidinger S et al. Safety and efficacy of amlitelimab, a fully human, non-depleting, non-cytotoxic anti-OX40Ligand monoclonal antibody, in atopic dermatitis: Results of a phase IIa randomised placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 18). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad240

Key clinical point: Amlitelimab is well-tolerated and improves disease signs and symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that is inadequately controlled by topical therapies.

Major finding: At week 16, the least-squares mean percentage change in Eczema Area and Severity Index score was significantly higher in low-dose (−80.12%; P = .009) and high-dose (−69.97%; P = .072) amlitelimab groups vs the placebo group (−49.37%). Overall, 62%, 47%, and 69% of patients reported ≥1 treatment-emergent adverse events with low- and high-dose amlitelimab and placebo groups, respectively.

Study details: This phase 2a study included 88 adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD and inadequate response to or inadvisability of topical treatments who were randomly assigned to receive low-dose (200 mg) or high-dose (500 mg) amlitelimab or placebo, followed by maintenance doses every 4 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Kymab Ltd., a Sanofi company. Some authors declared receiving research grants or consultancy fees or other ties with various sources, including Kymab and Sanofi. Six authors declared being employees or stockholders of Kymab or Sanofi.

Source: Weidinger S et al. Safety and efficacy of amlitelimab, a fully human, non-depleting, non-cytotoxic anti-OX40Ligand monoclonal antibody, in atopic dermatitis: Results of a phase IIa randomised placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 18). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad240

Nemolizumab shows promise in pediatric atopic dermatitis with inadequately controlled pruritus

Key clinical point: Nemolizumab is safe and effectively reduces pruritus in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) whose pruritus has not been sufficiently improved with topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors or antihistamines.

Major finding: At week 16, the nemolizumab vs placebo group had a significantly greater improvement in the weekly mean 5-level itch score (−1.3 vs −0.5; P < .0001), with a significantly higher proportion of patients achieving a weekly mean 5-level itch score ≤ 1 (24.4% vs 2.3%; P = .0035). Most adverse events were mild in severity and none led to treatment discontinuation or death.

Study details: Findings are a from multicenter phase 3 study including patients age 6-12 years with AD and inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe pruritus who were randomly assigned to receive nemolizumab (n = 45) or placebo (n = 44) with concomitant topical agents.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Maruho Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan. Two authors declared receiving grants and honoraria from various sources, including Maruho, and other two authors declared being employees of Maruho.

Source: Igarashi A et al. Efficacy and safety of nemolizumab in paediatric patients aged 6-12 years with atopic dermatitis with moderate-to-severe pruritus: Results from a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 31). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad268

Key clinical point: Nemolizumab is safe and effectively reduces pruritus in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) whose pruritus has not been sufficiently improved with topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors or antihistamines.

Major finding: At week 16, the nemolizumab vs placebo group had a significantly greater improvement in the weekly mean 5-level itch score (−1.3 vs −0.5; P < .0001), with a significantly higher proportion of patients achieving a weekly mean 5-level itch score ≤ 1 (24.4% vs 2.3%; P = .0035). Most adverse events were mild in severity and none led to treatment discontinuation or death.

Study details: Findings are a from multicenter phase 3 study including patients age 6-12 years with AD and inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe pruritus who were randomly assigned to receive nemolizumab (n = 45) or placebo (n = 44) with concomitant topical agents.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Maruho Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan. Two authors declared receiving grants and honoraria from various sources, including Maruho, and other two authors declared being employees of Maruho.

Source: Igarashi A et al. Efficacy and safety of nemolizumab in paediatric patients aged 6-12 years with atopic dermatitis with moderate-to-severe pruritus: Results from a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 31). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad268

Key clinical point: Nemolizumab is safe and effectively reduces pruritus in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) whose pruritus has not been sufficiently improved with topical corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors or antihistamines.

Major finding: At week 16, the nemolizumab vs placebo group had a significantly greater improvement in the weekly mean 5-level itch score (−1.3 vs −0.5; P < .0001), with a significantly higher proportion of patients achieving a weekly mean 5-level itch score ≤ 1 (24.4% vs 2.3%; P = .0035). Most adverse events were mild in severity and none led to treatment discontinuation or death.

Study details: Findings are a from multicenter phase 3 study including patients age 6-12 years with AD and inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe pruritus who were randomly assigned to receive nemolizumab (n = 45) or placebo (n = 44) with concomitant topical agents.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Maruho Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan. Two authors declared receiving grants and honoraria from various sources, including Maruho, and other two authors declared being employees of Maruho.

Source: Igarashi A et al. Efficacy and safety of nemolizumab in paediatric patients aged 6-12 years with atopic dermatitis with moderate-to-severe pruritus: Results from a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2023 (Jul 31). doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad268

Atopic Dermatitis: Differential Diagnosis

Economic Burden and Quality of Life of Patients With Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Helsinki, Finland: A Survey-Based Study

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disease that may severely decrease quality of life (QOL) and lead to psychiatric comorbidities.1-3 Prior studies have indicated that AD causes a substantial economic burden, and disease severity has been proportionally linked to medical costs.4,5 Results of a multicenter cost-of-illness study from Germany estimated that a relapse of AD costs approximately €123 (US $136). The authors calculated the average annual cost of AD per patient to be €1425 (US $1580), whereas it is €956 (US $1060) in moderate disease and €2068 (US $2293) in severe disease (direct and indirect medical costs included).6 An observational cohort study from the Netherlands found that total direct cost per patient-year (PPY) was €4401 (US $4879) for patients with controlled AD vs €6993 (US $7756) for patients with uncontrolled AD.7

In a retrospective survey-based study, it was estimated that the annual cost of AD in Canada was approximately CAD $1.4 billion. The cost per patient varied from CAD $282 to CAD $1242 depending on disease severity.8 In another retrospective cohort study from the Netherlands, the average direct medical cost per patient with AD seeing a general practitioner was US $71 during follow-up in primary care. If the patient needed specialist consultation, the cost increased to an average of US $186.9

We aimed to assess the direct and indirect medical costs in adult patients with moderate to severe AD who attended a tertiary health care center in Finland. In addition, we evaluated the impact of AD on QOL in this patient cohort.

Methods

Study Design—Patients with AD who were treated at the Department of Dermatology and Allergology, Helsinki University Hospital, Finland, between February 2018 and December 2019 were randomly selected to participate in our survey study. All participants provided written informed consent. In Finland, patients with mild AD generally are treated in primary health care centers, and only patients with moderate to severe AD are referred to specialists and tertiary care centers. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, had AD confined to the hands, or reported the presence of other concomitant skin diseases that were being treated with topical or systemic therapies. The protocol for the study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Helsinki.

Questionnaire and Analysis of Disease Severity—The survey included the medical history, signs of atopy, former treatment(s) for AD, skin infections, visits to dermatologists or general practitioners, questions on mental health and hospitalization, and absence from work due to AD in the last 12 months. Disease severity was evaluated using the patient-oriented Rajka & Langeland eczema severity score and Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM).10,11 The impact on QOL was evaluated by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).12

Medication Costs—The cost of prescription drugs was based on data from the Finnish national electronic prescription center. In Finland, all prescriptions are made electronically in the database. We analyzed all topical medications (eg, topical corticosteroids [TCSs], topical calcineurin inhibitors [TCIs], and emollients) and systemic medicaments (eg, antibiotics, antihistamines, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and corticosteroids) prescribed for the treatment of AD. In Finland, dupilumab was introduced for the treatment of severe AD in early 2019, and patients receiving dupilumab were excluded from the study. Over-the-counter medications were not included. The costs for laboratory testing were estimations based on the standard monitoring protocols of the Helsinki University Hospital. All costs were based on the Finnish price level standard for the year 2019.

Inpatient/Outpatient Visits and Sick Leave Due to AD—The number of inpatient and outpatient visits due to AD in the last 12 months was evaluated. Outpatient specialist consultations or nurse appointments at Helsinki University Hospital were verified from electronic patient records. In addition, inpatient treatment and phototherapy sessions were calculated from the database.

We assessed the number of sick leave days from work or educational activities during the last year. All costs of transportation for doctors’ appointments, laboratory monitoring, and phototherapy treatments were summed together to estimate the total transportation cost. Visits to nurse and inpatient visits were not included in the total transportation cost because patients often were hospitalized directly after consultation visits, and nurse appointments often were combined with inpatient and outpatient visits. To calculate the total transportation cost, we used a rate of €0.43 per kilometer measured from the patients’ home addresses, which was the official compensation rate of the Finnish Tax Administration for 2019.13

Statistical Analysis—Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM). Descriptive analyses were used to describe baseline characteristics and to evaluate the mean costs of AD. The patients were divided into 2 groups according to POEM: (1) controlled AD (patients with clear skin or only mild AD; POEM score 0–7) and (2) uncontrolled AD (patients with moderate to very severe AD; POEM score 8–28). The Mann-Whitney U statistic was used to evaluate differences between the study groups.

Results

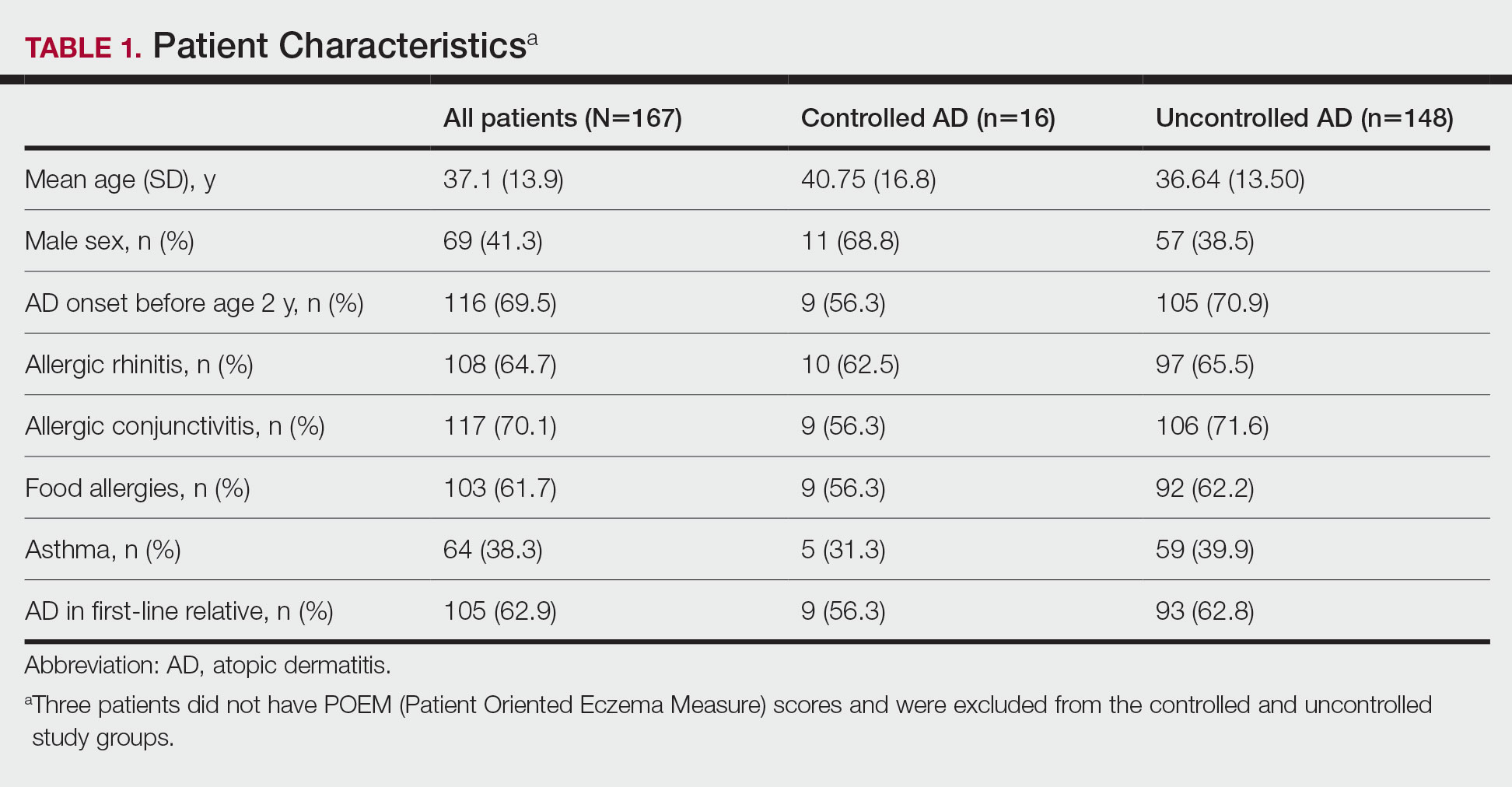

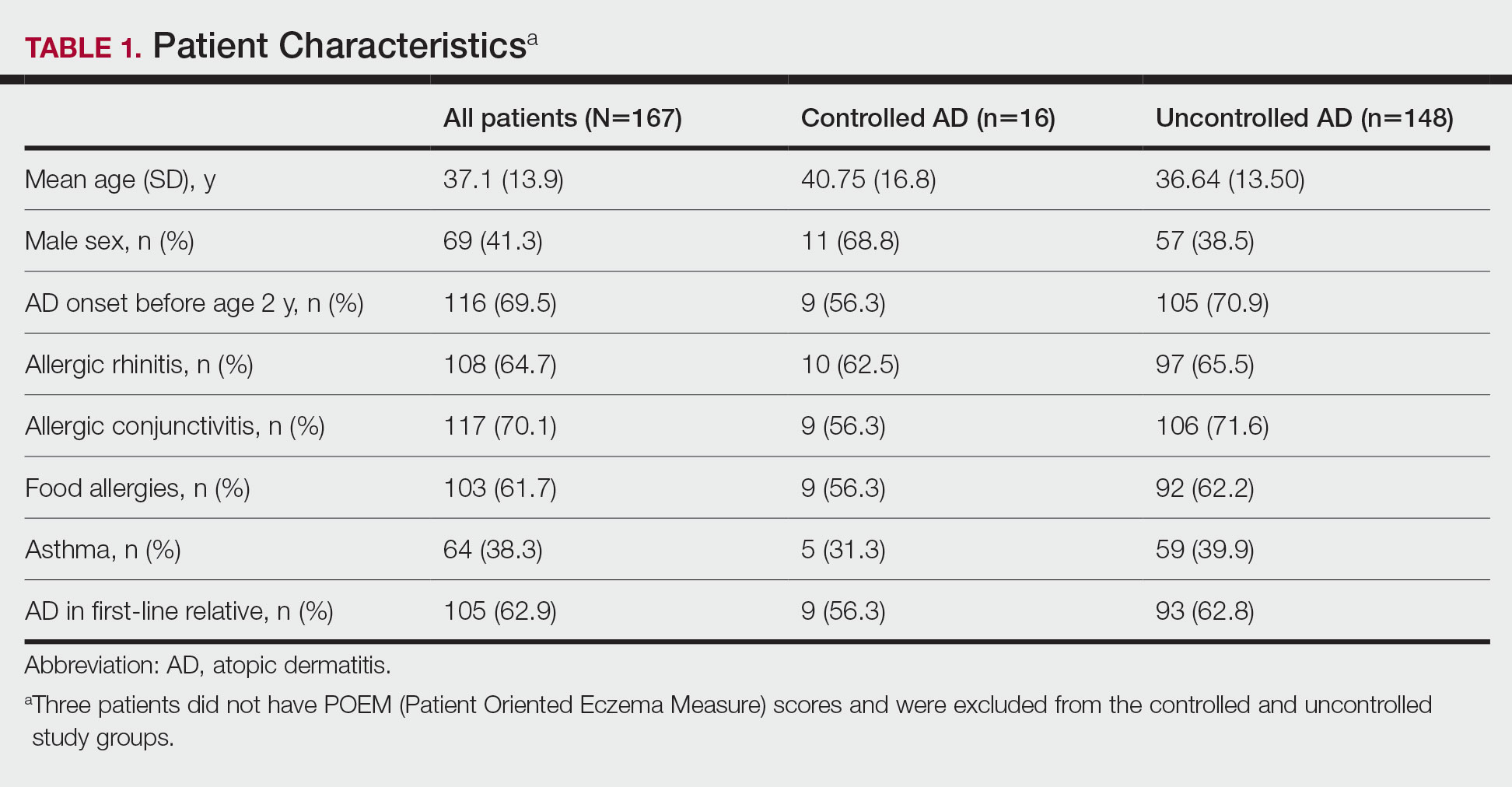

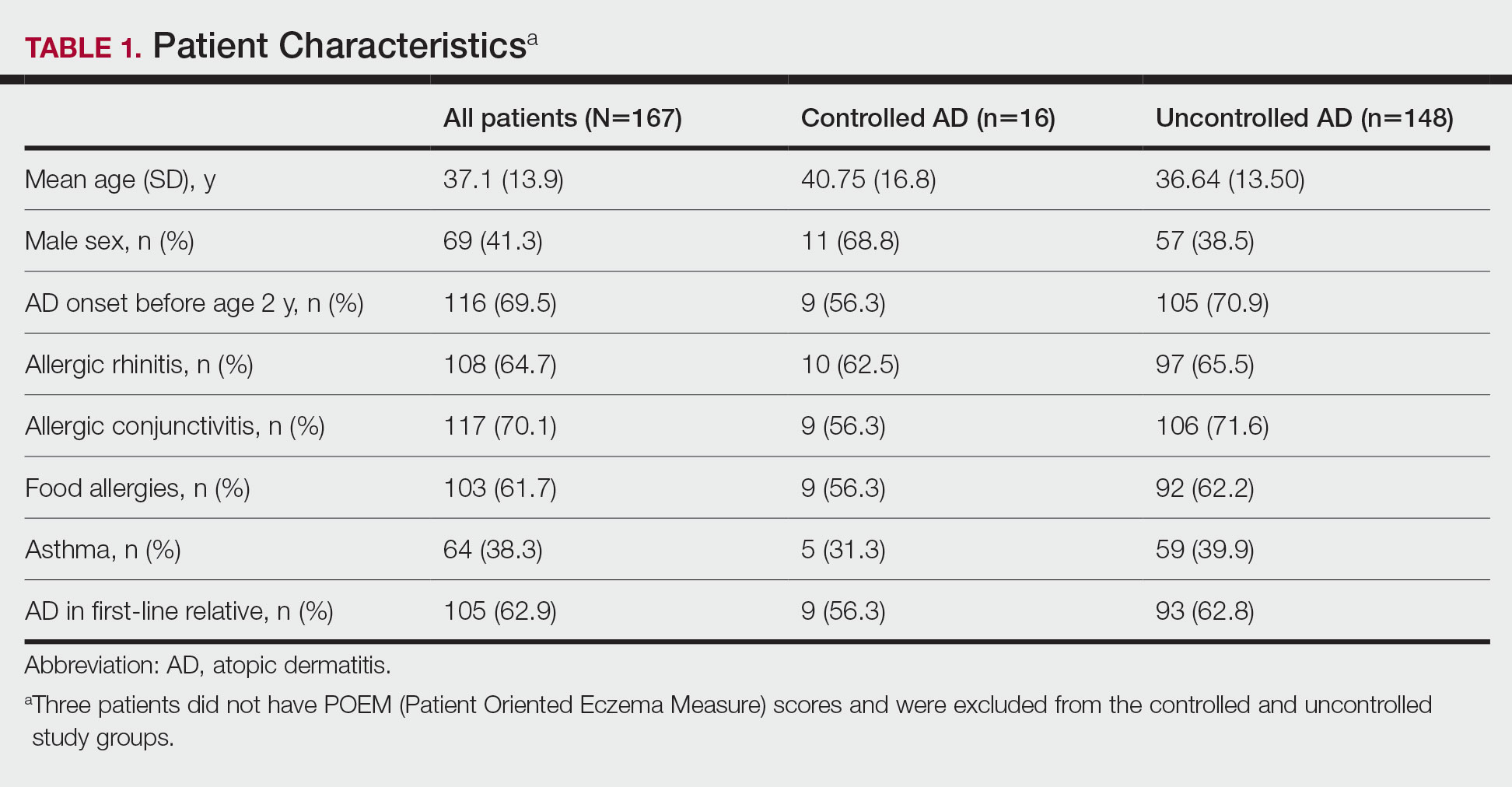

Patient Characteristics—One hundred sixty-seven patients answered the survey, of which 69 (41.3%) were males and 98 (58.7%) were females. There were 16 patients with controlled AD and 148 patients with uncontrolled AD. Three patients did not answer to POEM and were excluded. The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 and include self-reported symptoms related to atopy.

The most-used topical treatments were TCSs (n=155; 92.8%) and emollients (n=166; 99.4%). One hundred sixteen (69.5%) patients had used TCIs. The median amount of TCSs used was 300 g/y vs 30 g/y for TCIs (range, 0-5160 g/y) and 1200 g/y for emollients.

Fifteen (9.0%) patients had been hospitalized for AD in the last year. The mean (SD) length of hospitalization was 6.5 (2.8) days. Thirty-four (20.4%) patients received UVB phototherapy. Thirty-four (20.4%) patients were treated with at least 1 antibiotic course for secondary AD infection. Thirty-six (21.6%) patients needed at least 1 oral corticosteroid course for the treatment of an AD flare.

Fifteen (9.0%) patients reported a diagnosed psychiatric illness, and 17 (10.2%) patients were using prescription drugs for psychiatric illness. Forty-nine (29.3%) patients reported anxiety or depression often or very often, 54 (32.3%) patients reported sometimes, 33 (19.8%) patients reported rarely, and only 30 (18.0%) patients reported none.

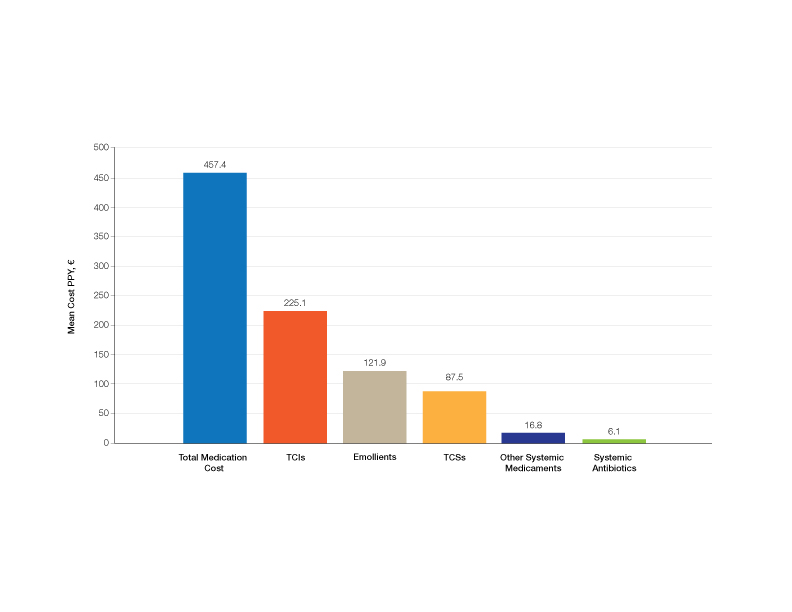

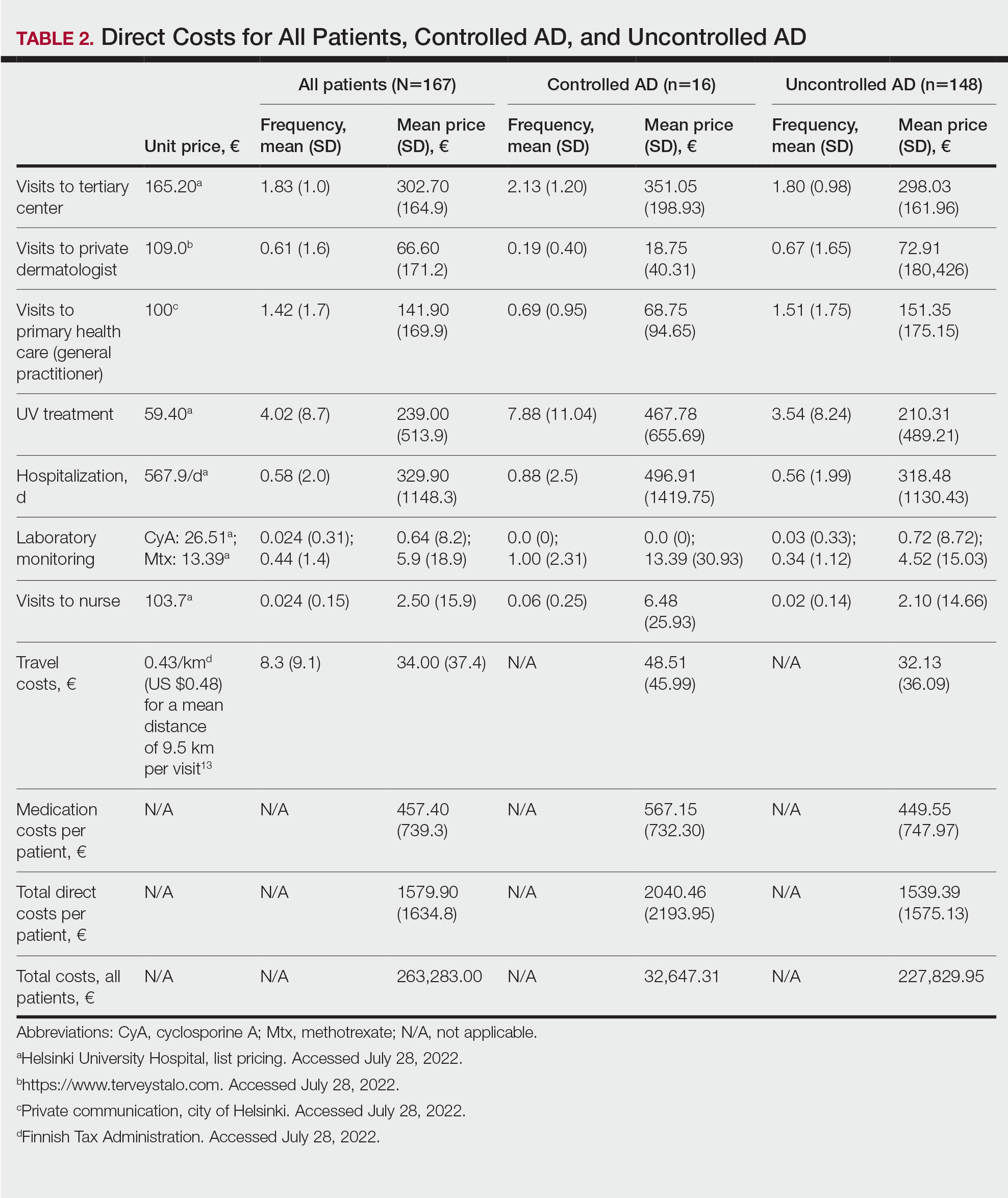

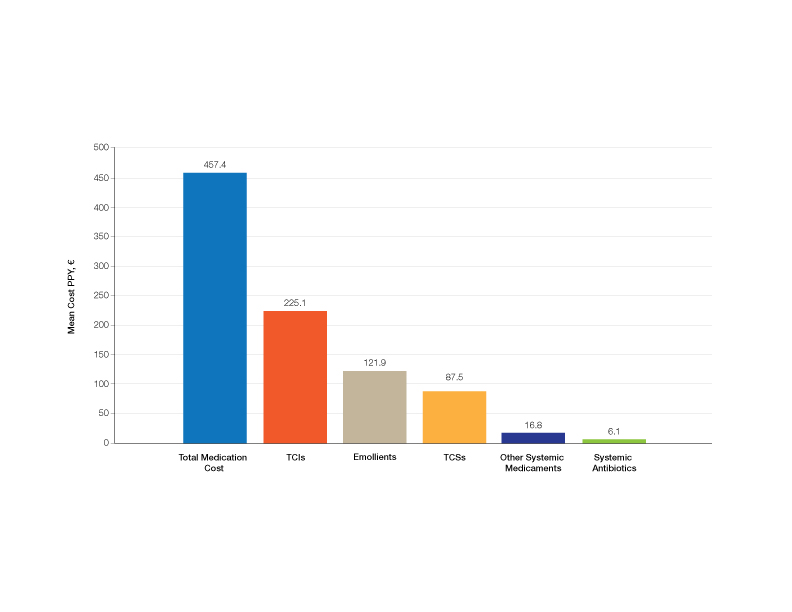

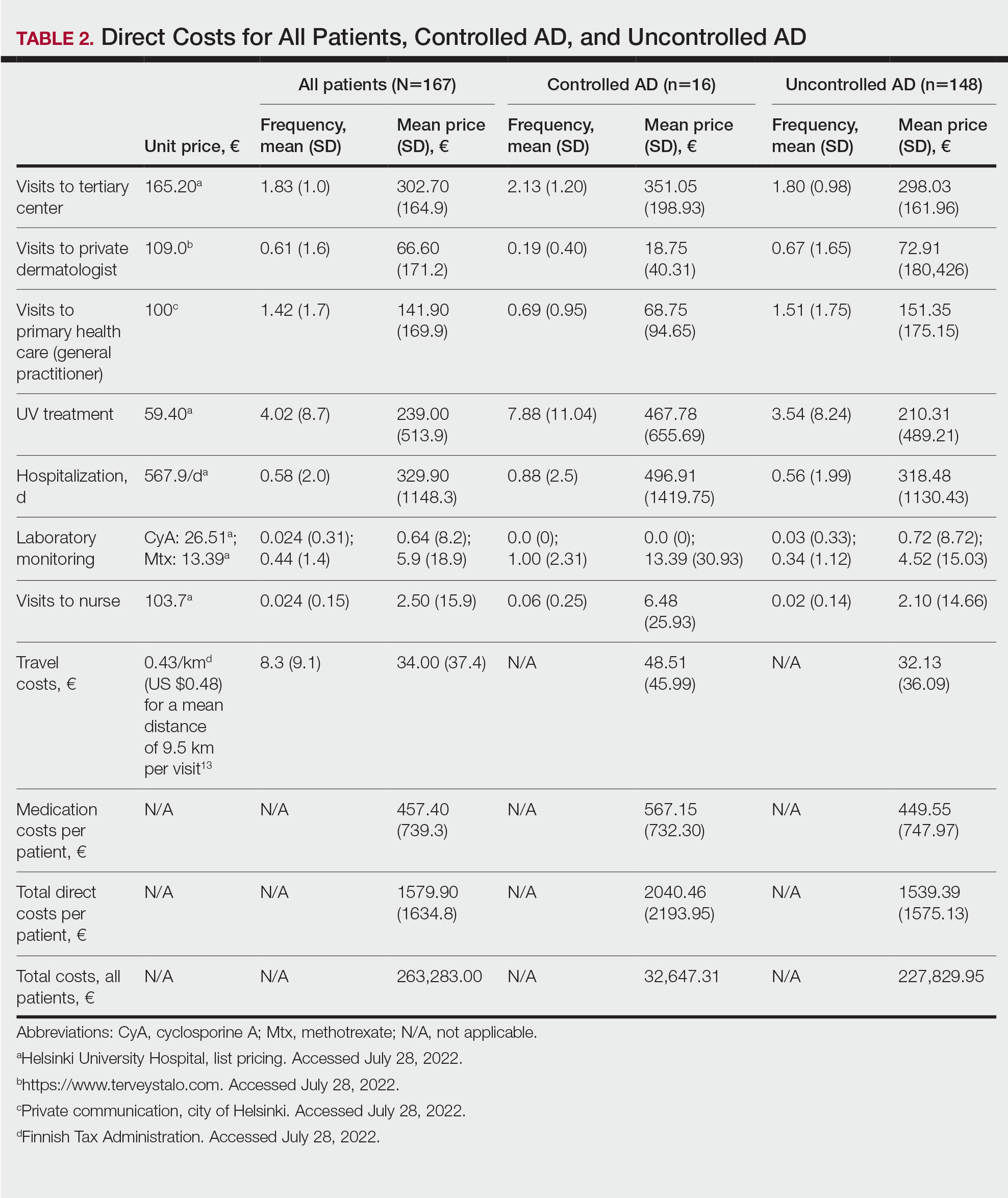

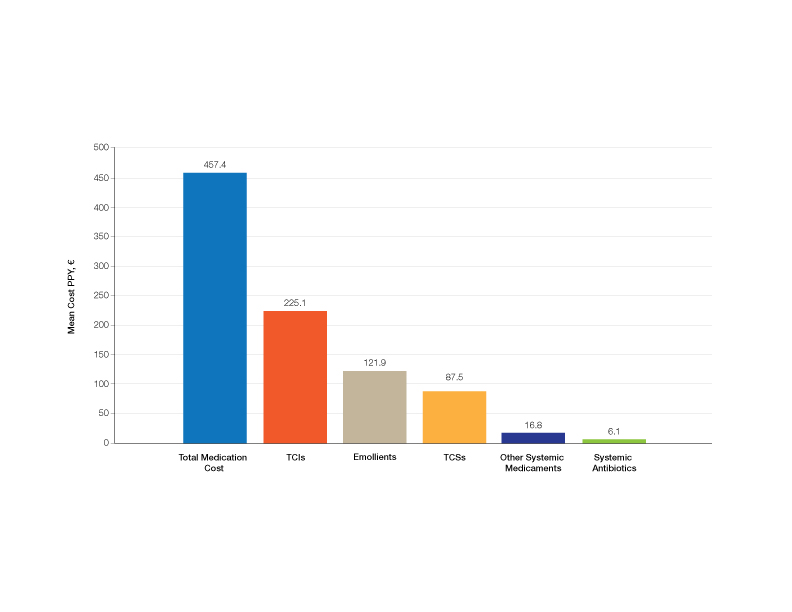

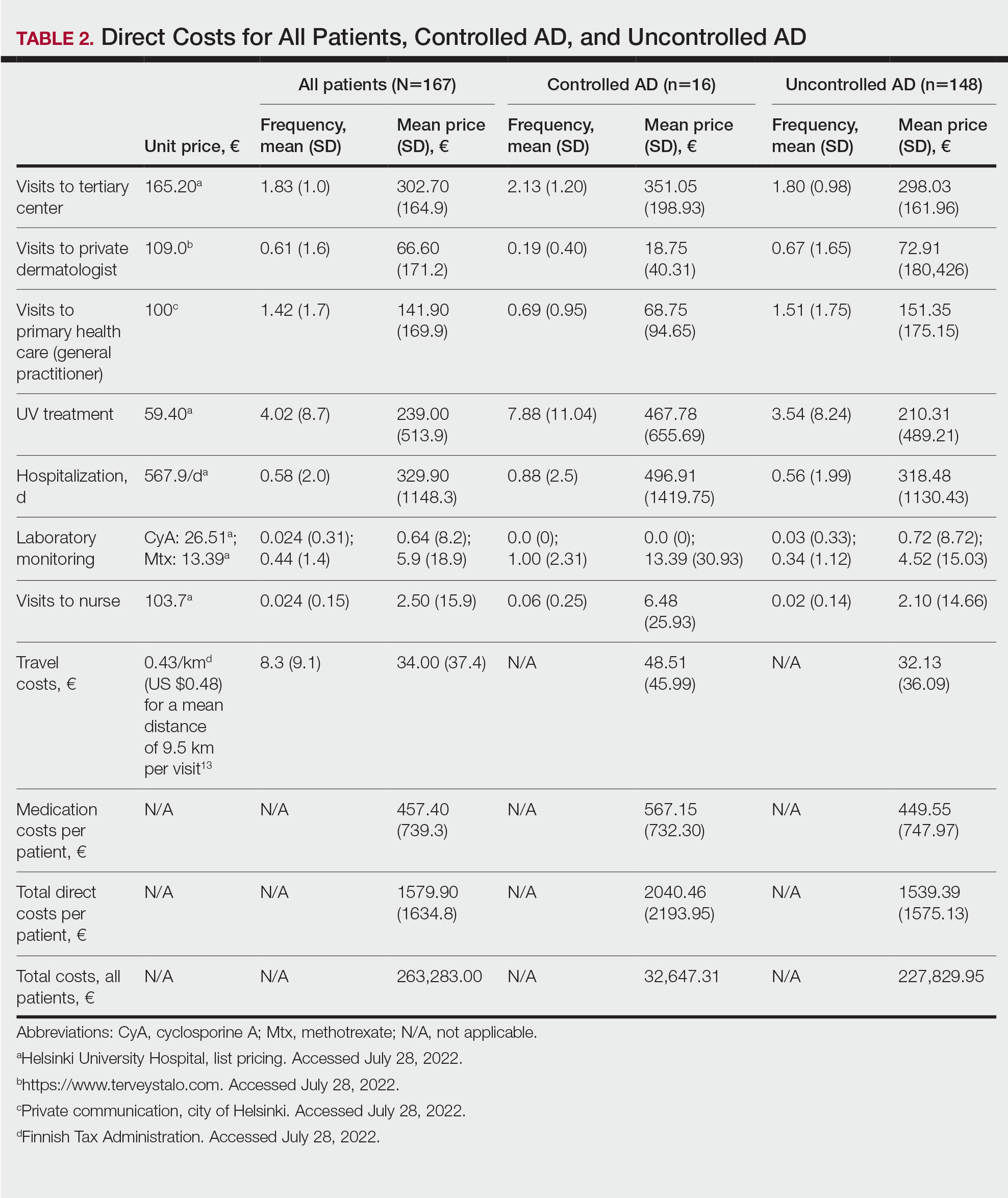

Medication Costs—Mean medication cost PPY was €457.40 (US $507.34)(Figure 1 and Table 2). On average, one patient spent €87.50 (US $97.05) for TCSs, €121.90 (US $135.21) for emollients, and €225.10 (US $249.68) for TCIs. The average cost PPY for antibiotics was €6.10 (US $6.77). Other systemic treatments, including (US $18.65). Seventeen patients (10.2%) were on methotrexate therapy for AD in the last year, and 1 patient also used cyclosporine. The costs for laboratory monitoring in these patients were included in the direct cost calculations. The mean cost PPY of laboratory monitoring in the whole study cohort was €6.60 (US $7.32). In patients with systemic immunosuppressive therapy, the mean cost PPY for laboratory monitoring was €65.00 (US $72.09). Five patients had been tested for contact dermatitis; the costs of patch tests or other diagnostic tests were not included.

Visits to Health Care Providers—In the last year, patients had an average of 1.83 dermatologist consultations in the tertiary center (Table 2). In addition, the mean number of visits to private dermatologists was 0.61 and 1.42 visits to general practitioners. The mean cost of physician visits was €302.70 (US $335.75) in the tertiary center, €66.60 (US $73.87) in the private sector, and €141.90 (US $157.39) in primary health care. In total, the average cost of doctors’ appointments PPY was €506.30 (US $561.57). The mean estimated distance traveled per visit was 9.5 km.

The mean cost PPY of inpatient treatments was €329.90 (US $365.92) and €239.00 (US $265.09) for UV phototherapy. Only 4 patients had visited a nurse in the last year, with an average cost PPY of €2.50 (US $2.78).

In total, the cost PPY for health care provider visits was €1084.20, which included specialist consultations in a tertiary center and private sector, visits in primary health care, inpatient treatments, UV phototherapy sessions, nurse appointments in a tertiary center, and laboratory monitoring. The average transportation cost PPY was €34.00 (US $37.71). The mean number of visits to health care providers was 8.3 per year. Altogether, the direct cost PPY in the study cohort was €1580.60 (US $1752.39)(Table 2 and Figure 2).

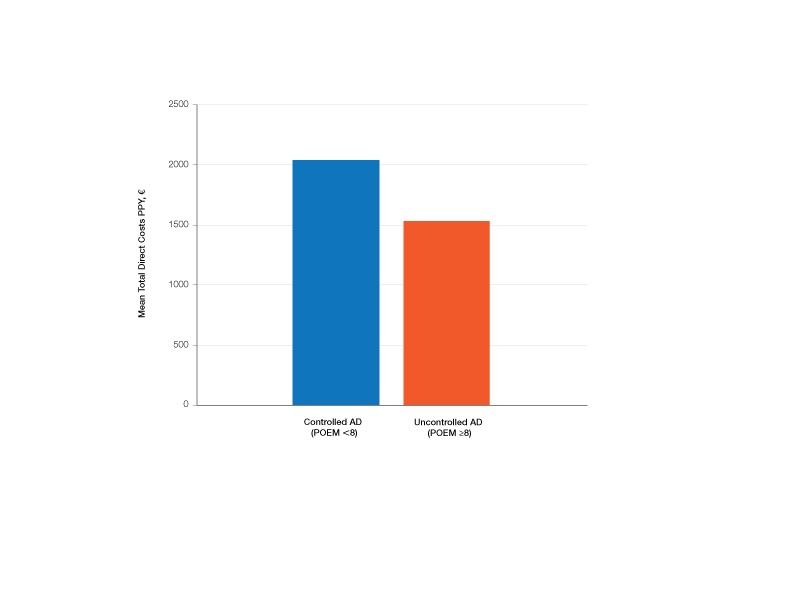

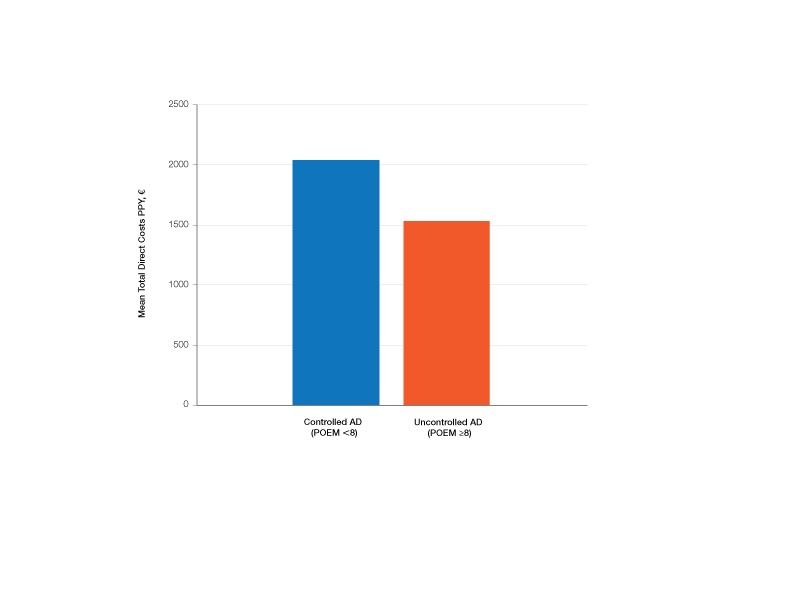

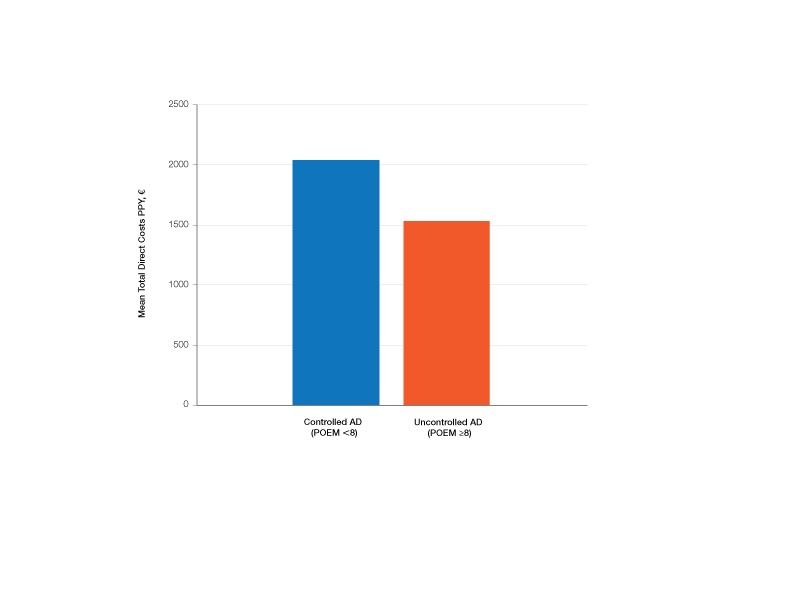

Comparison of Medical Costs in Controlled vs Uncontrolled AD—In the controlled AD group (POEM score <8), the mean medication cost PPY was €567.15 (US $629.13), and the mean total direct cost PPY was €2040.46 (US $2263.24). In the uncontrolled AD group (POEM score ≥8), the mean medication cost PPY was €449.55 (US $498.63), and the mean total direct cost PPY was €1539.39 (US $1707.36)(Table 2). The comparisons of the study groups—controlled vs uncontrolled AD—showed no significant differences regarding medication costs PPY (P=.305, Mann-Whitney U statistic) and total direct costs PPY (P=.361, Mann-Whitney U statistic)(Figure 3). Thus, the distribution of medical costs was similar across all categories of the POEM score.

AD Severity and QOL—The mean (SD) POEM score in the study cohort was 17.9 (6.9). Sixteen (9.6%) patients had clear to almost clear skin or mild AD (POEM score 0–7). Forty-two (25.1%) patients had moderate AD (POEM score 8–16). Most of the patients (106; 63.5%) had severe or very severe AD (POEM score 17–28). According to the Rajka & Langeland score, 5 (3.0%) patients had mild disease (score 34), 81 (48.5%) patients had moderate disease (score 5–7), and 81 (48.5%) patients had severe disease (score 8–9). Eighty-one (48.5%) patients answered that AD affects their lives greatly, and 58 (34.7%) patients answered that it affects their lives extremely. Twenty-five (15.0%) patients answered that AD affects their everyday life to some extent, and only 2 (1.2%) patients answered that AD had little or no effect.

The mean (SD) DLQI was 13 (7.2). Based on the DLQI, 31 (18.6%) patients answered that AD had no effect or only a small effect on QOL (DLQI 0–5). In 36 (21.6%) patients, AD had a moderate effect on QOL (DLQI 6–10). The QOL impact was large (DLQI 11–20) and very large (DLQI 21–30) in 67 (40.1%) and 33 (19.8%) patients, respectively.

There was no significant difference in the impact of disease severity (POEM score) on the decrease of QOL (severe or very severe disease; P=.305, Mann-Whitney U statistic).

Absence From Work or Studies—At the study inclusion, 12 (7.2%) patients were not working or studying. Of the remaining 155 patients, 73 (47.1%) reported absence from work or educational activities due to AD in the last 12 months. The mean (SD) length of absence was 11.6 (10.2) days.

Comment

In this survey-based study of Finnish patients with moderate to severe AD, we observed that AD creates a substantial economic burden14 and negative impact on everyday life and QOL. According to DLQI, AD had a large or very large effect on most of the patients’ (59.9%) lives, and 90.2% of the included patients had self-reported moderate to very severe symptoms (POEM score 8–28). Our observations can partly be explained by characteristics of the Finnish health care system, in which patients with moderate to severe AD mainly are referred to specialist consultation. In the investigated cohort, many patients had used antibiotics (20.4%) and/or oral corticosteroids (21.6%) in the last year for the treatment of AD, which might indicate inadequate treatment of AD in the Finnish health care system.

Motivating patients to remain compliant is one of the main challenges in AD therapy.15 Fear of adverse effects from TCSs is common among patients and may cause poor treatment adherence.16 In a prospective study from the United Kingdom, the use of emollients in moderate to severe AD was considerably lower than AD guidelines recommend—approximately 10 g/d on average in adult patients. The median use of TCSs was between 35 and 38 g/mo.17 In our Finnish patient cohort, the amount of topical treatments was even lower, with a median use of emollients of 3.3 g/d and median use of TCSs of 25 g/mo. In another study from Denmark (N=322), 31% of patients with AD did not redeem their topical prescription medicaments, indicating poor adherence to topical treatment.18

It has been demonstrated that most of the patients’ habituation (tachyphylaxis) to TCSs is due to poor adherence instead of physiologic changes in tissue corticosteroid receptors.19,20 Treatment adherence may be increased by scheduling early follow-up visits and providing adequate therapeutic patient education,21 which requires major efforts by the health care system and a financial investment.

Inadequate treatment will lead to more frequent disease flares and subsequently increase the medical costs for the patients and the health care system.22 In our Finnish patient cohort, a large part of direct treatment costs was due to inpatient treatment (Figure 2) even though only a small proportion of patients had been hospitalized. The patients were frequently young and otherwise in good general health, and they did not necessarily need continuous inpatient treatment and monitoring. In Finland, it will be necessary to develop more cost-effective treatment regimens for patients with AD with severe and frequent flares. Many patients would benefit from subsequent and regular sessions of topical treatment in an outpatient setting. In addition, the prevention of flares in moderate to severe AD will decrease medical costs.23

The mean medication cost PPY was €457.40 (US $507.34), and mean total direct cost PPY was €1579.90 (US $1752.40), which indicates that AD causes a major economic burden to Finnish patients and to the Finnish health care system (Figures 1 and 2).24 We did not observe significant differences between controlled and uncontrolled AD medical costs in our patient cohort (Figure 3), which may have been due to the relatively small sample size of only 16 patients in the controlled AD group. All patients attending the tertiary care hospital had moderate to severe AD, so it is likely that the patients with lower POEM scores had better-controlled disease. The POEM score estimates the grade of AD in the last 7 days, but based on the relapsing course of the disease, the grading score may differ substantially during the year in the same patient depending on the timing.25,26

Topical calcineurin inhibitors comprised almost half of the medication costs (Figure 1), which may be caused by their higher prices compared with TCSs in Finland. In the beginning of 2019, a 50% less expensive biosimilar of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% was introduced to the Finnish market, which might decrease future treatment costs of TCIs. However, availability problems in both topical tacrolimus products were seen throughout 2019, which also may have affected the results in our study cohort. The median use of TCIs was unexpectedly low (only 30 g/y), which may be explained by different application habits. The use of large TCI amounts in some patients may have elevated mean costs.27

In the Finnish public health care system, 40% of the cost for prescription medication and emollients is reimbursed after an initial deductible of €50. Emollients are reimbursed up to an amount of 1500 g/mo. Therefore, patients mostly acquired emollients as prescription medicine and not over-the-counter. Nonprescription medicaments were not included in our study, so the actual costs of topical treatment may have been higher.28

In our cohort, 61.7% of the patients reported food allergies, and 70.1% reported allergic conjunctivitis. However, the study included only questionnaire-based data, and many of these patients probably had symptoms not associated with IgE-mediated allergies. The high prevalence indicates a substantial concomitant burden of more than skin symptoms in patients with AD.29 Nine percent of patients reported a diagnosed psychiatric disorder, and 29.3% had self-reported anxiety or depression often or very often in the last year. Based on these findings, there may be high percentages of undiagnosed psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety disorders in patients with moderate to severe AD in Finland.30 An important limitation of our study was that the patient data were based on a voluntary and anonymous survey and that depression and anxiety were addressed solely by a single question. In addition, the response rate cannot be analyzed correctly, and the demographics of the survey responders likely will differ substantially from all patients with AD at the university hospital.

Atopic dermatitis had a substantial effect on QOL in our patient cohort. Inadequate treatment of AD is known to negatively affect patient QOL and may lead to hospitalization or frequent oral corticosteroid courses.31,32 In most cases, structured patient education and early follow-up visits may improve patient adherence to treatment and should be considered as an integral part of AD treatment.33 In the investigated Finnish tertiary care hospital, a structured patient education system unfortunately was still lacking, though it has been proven effective elsewhere.34 In addition, patient-centred educational programs are recommended in European guidelines for the treatment of AD.35

Medical costs of AD may increase in the future as new treatments with higher direct costs, such as dupilumab, are introduced. Eichenfeld et al36 analyzed electronic health plan claims in patients with AD with newly introduced systemic therapies and phototherapies after the availability of dupilumab in the United States (March 2017). Mean annualized total cost in all patients was $20,722; the highest in the dupilumab group with $36,505. Compared to our data, the total costs are much higher, but these are likely to rise in Finland in the future if a substantial amount (eg, 1%–5%) of patients will be on advanced therapies, including dupilumab. If advanced therapies will be introduced more broadly in Finland (eg, in the treatment of moderate AD [10%–20% of patients]), they will represent a major direct cost to the health care system. Zimmermann et al37 showed in a cost-utility analysis that dupilumab improves health outcomes but with additional direct costs, and it is likely more cost-effective in patients with severe AD. Conversely, more efficient treatments may improve severe AD, reduce the need for hospitalization and recurrent doctors’ appointments as well as absence from work, and improve patient QOL,38 consequently decreasing indirect medical costs and disease burden. Ariëns et al39 showed in a recent registry-based study that dupilumab treatment induces a notable rise in work productivity and reduction of associated costs in patients with difficult-to-treat AD.

Conclusion

We aimed to analyze the economic burden of AD in Finland before the introduction of dupilumab. It will be interesting to see what the introduction of dupilumab and other novel systemic therapies have on total economic burden and medical costs. Most patients with AD in Finland can achieve disease control with topical treatments, but it is important to efficiently manage the patients who require additional supportive measures and specialist consultations, which may be challenging in the primary health care system because of the relapsing and remitting nature of the disease.

- Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(suppl 1):8-16.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351.

- Yang EJ, Beck KM, Sekhon S, et al. The impact of pediatric atopic dermatitis on families: a review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:66-71.

- Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the United States: an analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:274-279.

- Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:26-30.

- Ehlken B, Möhrenschlager M, Kugland B, et al. Cost-of-illness study in patients suffering from atopic eczema in Germany. Der Hautarzt. 2006;56:1144-1151.

- Ariëns LFM, van Nimwegen KJM, Shams M, et al. Economic burden of adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis indicated for systemic treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:762-768.

- Barbeau M, Bpharm HL. Burden of atopic dermatitis in Canada. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:31-36.

- Verboom P, Hakkaart‐Van Roijen L, Sturkenboom M, et al. The cost of atopic dermatitis in the Netherlands: an international comparison. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:716-724.

- Gånemo A, Svensson Å, Svedman C, et al. Usefulness of Rajka & Langeland eczema severity score in clinical practice. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:521-524.

- Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1513-1519.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Rehunen A, Reissell E, Honkatukia J, et al. Social and health services: regional changes in need, use and production and future options. Accessed July 20, 2023. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-287-294-4

- Reed B, Blaiss MS. The burden of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39:406-410.

- Koszorú K, Borza J, Gulácsi L, et al. Quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2019;104:174-177.

- Li AW, Yin ES, Antaya RJ. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1036-1042.

- Choi J, Dawe R, Ibbotson S, et al. Quantitative analysis of topical treatments in atopic dermatitis: unexpectedly low use of emollients and strong correlation of topical corticosteroid use both with depression and concurrent asthma. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1017-1025.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Okwundu N, Cardwell LA, Cline A, et al. Topical corticosteroids for treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;102:205-209.

- Eicher L, Knop M, Aszodi N, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing treatment adherence in chronic inflammatory skin disease—strategies for optimizing treatment outcome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:2253-2263.

- Heratizadeh A, Werfel T, Wollenberg A, et al; Arbeitsgemeinschaft Neurodermitisschulung für Erwachsene (ARNE) Study Group. Effects of structured patient education in adults with atopic dermatitis: multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:845-853.

- Dierick BJH, van der Molen T, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, et al. Burden and socioeconomics of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and food allergy. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;20:437-453.

- Olsson M, Bajpai R, Yew YW, et al. Associations between health-related quality of life and health care costs among children with atopic dermatitis and their caregivers: a cross-sectional study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:284-293.

- Bruin-Weller M, Pink AE, Patrizi A, et al. Disease burden and treatment history among adults with atopic dermatitis receiving systemic therapy: baseline characteristics of participants on the EUROSTAD prospective observational study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:164-173.

- Silverberg JI, Lei D, Yousaf M, et al. Comparison of Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure and Patient-Oriented Scoring Atopic Dermatitis vs Eczema Area and Severity Index and other measures of atopic dermatitis: a validation study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125:78-83.

- Kido-Nakahara M, Nakahara T, Yasukochi Y, et al. Patient-oriented eczema measure score: a useful tool for web-based surveys in patients with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;47:924-925.

- Komura Y, Kogure T, Kawahara K, et al. Economic assessment of actual prescription of drugs for treatment of atopic dermatitis: differences between dermatology and pediatrics in large-scale receipt data. J Dermatol. 2018;45:165-174.

- Thompson AM, Chan A, Torabi M, et al. Eczema moisturizers: allergenic potential, marketing claims, and costs. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14228.

- Egeberg A, Andersen YM, Gislason GH, et al. Prevalence of comorbidity and associated risk factors in adults with atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2017;72:783-791.

- Kauppi S, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, et al. Adult patients with atopic eczema have a high burden of psychiatric disease: a Finnish nationwide registry study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:647-651.

- Ali F, Vyas J, Finlay AY. Counting the burden: atopic dermatitis and health-related quality of life. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00161.

- Birdi G, Cooke R, Knibb RC. Impact of atopic dermatitis on quality of life in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:E75-E91.

- Gabes M, Tischer C, Apfelbacher C; quality of life working group of the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative. Measurement properties of quality-of-life outcome measures for children and adults with eczema: an updated systematic review. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31:66-77.

- Staab D, Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, et al. Age related, structured educational programmes for the management of atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332:933-938.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al; European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD), European Federation of Allergy and Airways Diseases Patients’ Associations (EFA), the European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry (ESDaP), the European Society of Pediatric Dermatology (ESPD), Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) and the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS). Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850-878.

- Eichenfield LF, DiBonaventura M, Xenakis J, et al. Costs and treatment patterns among patients with atopic dermatitis using advanced therapies in the United States: analysis of a retrospective claims database. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:791-806.

- Zimmermann M, Rind D, Chapman R, et al. Economic evaluation of dupilumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a cost-utility analysis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:750-756.

- Mata E, Loh TY, Ludwig C, et al. Pharmacy costs of systemic and topical medications for atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;12:1-3.

- Ariëns LFM, Bakker DS, Spekhorst LS, et al. Rapid and sustained effect of dupilumab on work productivity in patients with difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis: results from the Dutch BioDay Registry. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;19;101:adv00573.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disease that may severely decrease quality of life (QOL) and lead to psychiatric comorbidities.1-3 Prior studies have indicated that AD causes a substantial economic burden, and disease severity has been proportionally linked to medical costs.4,5 Results of a multicenter cost-of-illness study from Germany estimated that a relapse of AD costs approximately €123 (US $136). The authors calculated the average annual cost of AD per patient to be €1425 (US $1580), whereas it is €956 (US $1060) in moderate disease and €2068 (US $2293) in severe disease (direct and indirect medical costs included).6 An observational cohort study from the Netherlands found that total direct cost per patient-year (PPY) was €4401 (US $4879) for patients with controlled AD vs €6993 (US $7756) for patients with uncontrolled AD.7

In a retrospective survey-based study, it was estimated that the annual cost of AD in Canada was approximately CAD $1.4 billion. The cost per patient varied from CAD $282 to CAD $1242 depending on disease severity.8 In another retrospective cohort study from the Netherlands, the average direct medical cost per patient with AD seeing a general practitioner was US $71 during follow-up in primary care. If the patient needed specialist consultation, the cost increased to an average of US $186.9

We aimed to assess the direct and indirect medical costs in adult patients with moderate to severe AD who attended a tertiary health care center in Finland. In addition, we evaluated the impact of AD on QOL in this patient cohort.

Methods

Study Design—Patients with AD who were treated at the Department of Dermatology and Allergology, Helsinki University Hospital, Finland, between February 2018 and December 2019 were randomly selected to participate in our survey study. All participants provided written informed consent. In Finland, patients with mild AD generally are treated in primary health care centers, and only patients with moderate to severe AD are referred to specialists and tertiary care centers. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, had AD confined to the hands, or reported the presence of other concomitant skin diseases that were being treated with topical or systemic therapies. The protocol for the study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Helsinki.

Questionnaire and Analysis of Disease Severity—The survey included the medical history, signs of atopy, former treatment(s) for AD, skin infections, visits to dermatologists or general practitioners, questions on mental health and hospitalization, and absence from work due to AD in the last 12 months. Disease severity was evaluated using the patient-oriented Rajka & Langeland eczema severity score and Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM).10,11 The impact on QOL was evaluated by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).12

Medication Costs—The cost of prescription drugs was based on data from the Finnish national electronic prescription center. In Finland, all prescriptions are made electronically in the database. We analyzed all topical medications (eg, topical corticosteroids [TCSs], topical calcineurin inhibitors [TCIs], and emollients) and systemic medicaments (eg, antibiotics, antihistamines, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and corticosteroids) prescribed for the treatment of AD. In Finland, dupilumab was introduced for the treatment of severe AD in early 2019, and patients receiving dupilumab were excluded from the study. Over-the-counter medications were not included. The costs for laboratory testing were estimations based on the standard monitoring protocols of the Helsinki University Hospital. All costs were based on the Finnish price level standard for the year 2019.

Inpatient/Outpatient Visits and Sick Leave Due to AD—The number of inpatient and outpatient visits due to AD in the last 12 months was evaluated. Outpatient specialist consultations or nurse appointments at Helsinki University Hospital were verified from electronic patient records. In addition, inpatient treatment and phototherapy sessions were calculated from the database.

We assessed the number of sick leave days from work or educational activities during the last year. All costs of transportation for doctors’ appointments, laboratory monitoring, and phototherapy treatments were summed together to estimate the total transportation cost. Visits to nurse and inpatient visits were not included in the total transportation cost because patients often were hospitalized directly after consultation visits, and nurse appointments often were combined with inpatient and outpatient visits. To calculate the total transportation cost, we used a rate of €0.43 per kilometer measured from the patients’ home addresses, which was the official compensation rate of the Finnish Tax Administration for 2019.13

Statistical Analysis—Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM). Descriptive analyses were used to describe baseline characteristics and to evaluate the mean costs of AD. The patients were divided into 2 groups according to POEM: (1) controlled AD (patients with clear skin or only mild AD; POEM score 0–7) and (2) uncontrolled AD (patients with moderate to very severe AD; POEM score 8–28). The Mann-Whitney U statistic was used to evaluate differences between the study groups.

Results

Patient Characteristics—One hundred sixty-seven patients answered the survey, of which 69 (41.3%) were males and 98 (58.7%) were females. There were 16 patients with controlled AD and 148 patients with uncontrolled AD. Three patients did not answer to POEM and were excluded. The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 and include self-reported symptoms related to atopy.

The most-used topical treatments were TCSs (n=155; 92.8%) and emollients (n=166; 99.4%). One hundred sixteen (69.5%) patients had used TCIs. The median amount of TCSs used was 300 g/y vs 30 g/y for TCIs (range, 0-5160 g/y) and 1200 g/y for emollients.

Fifteen (9.0%) patients had been hospitalized for AD in the last year. The mean (SD) length of hospitalization was 6.5 (2.8) days. Thirty-four (20.4%) patients received UVB phototherapy. Thirty-four (20.4%) patients were treated with at least 1 antibiotic course for secondary AD infection. Thirty-six (21.6%) patients needed at least 1 oral corticosteroid course for the treatment of an AD flare.

Fifteen (9.0%) patients reported a diagnosed psychiatric illness, and 17 (10.2%) patients were using prescription drugs for psychiatric illness. Forty-nine (29.3%) patients reported anxiety or depression often or very often, 54 (32.3%) patients reported sometimes, 33 (19.8%) patients reported rarely, and only 30 (18.0%) patients reported none.

Medication Costs—Mean medication cost PPY was €457.40 (US $507.34)(Figure 1 and Table 2). On average, one patient spent €87.50 (US $97.05) for TCSs, €121.90 (US $135.21) for emollients, and €225.10 (US $249.68) for TCIs. The average cost PPY for antibiotics was €6.10 (US $6.77). Other systemic treatments, including (US $18.65). Seventeen patients (10.2%) were on methotrexate therapy for AD in the last year, and 1 patient also used cyclosporine. The costs for laboratory monitoring in these patients were included in the direct cost calculations. The mean cost PPY of laboratory monitoring in the whole study cohort was €6.60 (US $7.32). In patients with systemic immunosuppressive therapy, the mean cost PPY for laboratory monitoring was €65.00 (US $72.09). Five patients had been tested for contact dermatitis; the costs of patch tests or other diagnostic tests were not included.

Visits to Health Care Providers—In the last year, patients had an average of 1.83 dermatologist consultations in the tertiary center (Table 2). In addition, the mean number of visits to private dermatologists was 0.61 and 1.42 visits to general practitioners. The mean cost of physician visits was €302.70 (US $335.75) in the tertiary center, €66.60 (US $73.87) in the private sector, and €141.90 (US $157.39) in primary health care. In total, the average cost of doctors’ appointments PPY was €506.30 (US $561.57). The mean estimated distance traveled per visit was 9.5 km.

The mean cost PPY of inpatient treatments was €329.90 (US $365.92) and €239.00 (US $265.09) for UV phototherapy. Only 4 patients had visited a nurse in the last year, with an average cost PPY of €2.50 (US $2.78).

In total, the cost PPY for health care provider visits was €1084.20, which included specialist consultations in a tertiary center and private sector, visits in primary health care, inpatient treatments, UV phototherapy sessions, nurse appointments in a tertiary center, and laboratory monitoring. The average transportation cost PPY was €34.00 (US $37.71). The mean number of visits to health care providers was 8.3 per year. Altogether, the direct cost PPY in the study cohort was €1580.60 (US $1752.39)(Table 2 and Figure 2).

Comparison of Medical Costs in Controlled vs Uncontrolled AD—In the controlled AD group (POEM score <8), the mean medication cost PPY was €567.15 (US $629.13), and the mean total direct cost PPY was €2040.46 (US $2263.24). In the uncontrolled AD group (POEM score ≥8), the mean medication cost PPY was €449.55 (US $498.63), and the mean total direct cost PPY was €1539.39 (US $1707.36)(Table 2). The comparisons of the study groups—controlled vs uncontrolled AD—showed no significant differences regarding medication costs PPY (P=.305, Mann-Whitney U statistic) and total direct costs PPY (P=.361, Mann-Whitney U statistic)(Figure 3). Thus, the distribution of medical costs was similar across all categories of the POEM score.

AD Severity and QOL—The mean (SD) POEM score in the study cohort was 17.9 (6.9). Sixteen (9.6%) patients had clear to almost clear skin or mild AD (POEM score 0–7). Forty-two (25.1%) patients had moderate AD (POEM score 8–16). Most of the patients (106; 63.5%) had severe or very severe AD (POEM score 17–28). According to the Rajka & Langeland score, 5 (3.0%) patients had mild disease (score 34), 81 (48.5%) patients had moderate disease (score 5–7), and 81 (48.5%) patients had severe disease (score 8–9). Eighty-one (48.5%) patients answered that AD affects their lives greatly, and 58 (34.7%) patients answered that it affects their lives extremely. Twenty-five (15.0%) patients answered that AD affects their everyday life to some extent, and only 2 (1.2%) patients answered that AD had little or no effect.

The mean (SD) DLQI was 13 (7.2). Based on the DLQI, 31 (18.6%) patients answered that AD had no effect or only a small effect on QOL (DLQI 0–5). In 36 (21.6%) patients, AD had a moderate effect on QOL (DLQI 6–10). The QOL impact was large (DLQI 11–20) and very large (DLQI 21–30) in 67 (40.1%) and 33 (19.8%) patients, respectively.

There was no significant difference in the impact of disease severity (POEM score) on the decrease of QOL (severe or very severe disease; P=.305, Mann-Whitney U statistic).

Absence From Work or Studies—At the study inclusion, 12 (7.2%) patients were not working or studying. Of the remaining 155 patients, 73 (47.1%) reported absence from work or educational activities due to AD in the last 12 months. The mean (SD) length of absence was 11.6 (10.2) days.

Comment

In this survey-based study of Finnish patients with moderate to severe AD, we observed that AD creates a substantial economic burden14 and negative impact on everyday life and QOL. According to DLQI, AD had a large or very large effect on most of the patients’ (59.9%) lives, and 90.2% of the included patients had self-reported moderate to very severe symptoms (POEM score 8–28). Our observations can partly be explained by characteristics of the Finnish health care system, in which patients with moderate to severe AD mainly are referred to specialist consultation. In the investigated cohort, many patients had used antibiotics (20.4%) and/or oral corticosteroids (21.6%) in the last year for the treatment of AD, which might indicate inadequate treatment of AD in the Finnish health care system.

Motivating patients to remain compliant is one of the main challenges in AD therapy.15 Fear of adverse effects from TCSs is common among patients and may cause poor treatment adherence.16 In a prospective study from the United Kingdom, the use of emollients in moderate to severe AD was considerably lower than AD guidelines recommend—approximately 10 g/d on average in adult patients. The median use of TCSs was between 35 and 38 g/mo.17 In our Finnish patient cohort, the amount of topical treatments was even lower, with a median use of emollients of 3.3 g/d and median use of TCSs of 25 g/mo. In another study from Denmark (N=322), 31% of patients with AD did not redeem their topical prescription medicaments, indicating poor adherence to topical treatment.18

It has been demonstrated that most of the patients’ habituation (tachyphylaxis) to TCSs is due to poor adherence instead of physiologic changes in tissue corticosteroid receptors.19,20 Treatment adherence may be increased by scheduling early follow-up visits and providing adequate therapeutic patient education,21 which requires major efforts by the health care system and a financial investment.

Inadequate treatment will lead to more frequent disease flares and subsequently increase the medical costs for the patients and the health care system.22 In our Finnish patient cohort, a large part of direct treatment costs was due to inpatient treatment (Figure 2) even though only a small proportion of patients had been hospitalized. The patients were frequently young and otherwise in good general health, and they did not necessarily need continuous inpatient treatment and monitoring. In Finland, it will be necessary to develop more cost-effective treatment regimens for patients with AD with severe and frequent flares. Many patients would benefit from subsequent and regular sessions of topical treatment in an outpatient setting. In addition, the prevention of flares in moderate to severe AD will decrease medical costs.23

The mean medication cost PPY was €457.40 (US $507.34), and mean total direct cost PPY was €1579.90 (US $1752.40), which indicates that AD causes a major economic burden to Finnish patients and to the Finnish health care system (Figures 1 and 2).24 We did not observe significant differences between controlled and uncontrolled AD medical costs in our patient cohort (Figure 3), which may have been due to the relatively small sample size of only 16 patients in the controlled AD group. All patients attending the tertiary care hospital had moderate to severe AD, so it is likely that the patients with lower POEM scores had better-controlled disease. The POEM score estimates the grade of AD in the last 7 days, but based on the relapsing course of the disease, the grading score may differ substantially during the year in the same patient depending on the timing.25,26

Topical calcineurin inhibitors comprised almost half of the medication costs (Figure 1), which may be caused by their higher prices compared with TCSs in Finland. In the beginning of 2019, a 50% less expensive biosimilar of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% was introduced to the Finnish market, which might decrease future treatment costs of TCIs. However, availability problems in both topical tacrolimus products were seen throughout 2019, which also may have affected the results in our study cohort. The median use of TCIs was unexpectedly low (only 30 g/y), which may be explained by different application habits. The use of large TCI amounts in some patients may have elevated mean costs.27

In the Finnish public health care system, 40% of the cost for prescription medication and emollients is reimbursed after an initial deductible of €50. Emollients are reimbursed up to an amount of 1500 g/mo. Therefore, patients mostly acquired emollients as prescription medicine and not over-the-counter. Nonprescription medicaments were not included in our study, so the actual costs of topical treatment may have been higher.28

In our cohort, 61.7% of the patients reported food allergies, and 70.1% reported allergic conjunctivitis. However, the study included only questionnaire-based data, and many of these patients probably had symptoms not associated with IgE-mediated allergies. The high prevalence indicates a substantial concomitant burden of more than skin symptoms in patients with AD.29 Nine percent of patients reported a diagnosed psychiatric disorder, and 29.3% had self-reported anxiety or depression often or very often in the last year. Based on these findings, there may be high percentages of undiagnosed psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety disorders in patients with moderate to severe AD in Finland.30 An important limitation of our study was that the patient data were based on a voluntary and anonymous survey and that depression and anxiety were addressed solely by a single question. In addition, the response rate cannot be analyzed correctly, and the demographics of the survey responders likely will differ substantially from all patients with AD at the university hospital.

Atopic dermatitis had a substantial effect on QOL in our patient cohort. Inadequate treatment of AD is known to negatively affect patient QOL and may lead to hospitalization or frequent oral corticosteroid courses.31,32 In most cases, structured patient education and early follow-up visits may improve patient adherence to treatment and should be considered as an integral part of AD treatment.33 In the investigated Finnish tertiary care hospital, a structured patient education system unfortunately was still lacking, though it has been proven effective elsewhere.34 In addition, patient-centred educational programs are recommended in European guidelines for the treatment of AD.35

Medical costs of AD may increase in the future as new treatments with higher direct costs, such as dupilumab, are introduced. Eichenfeld et al36 analyzed electronic health plan claims in patients with AD with newly introduced systemic therapies and phototherapies after the availability of dupilumab in the United States (March 2017). Mean annualized total cost in all patients was $20,722; the highest in the dupilumab group with $36,505. Compared to our data, the total costs are much higher, but these are likely to rise in Finland in the future if a substantial amount (eg, 1%–5%) of patients will be on advanced therapies, including dupilumab. If advanced therapies will be introduced more broadly in Finland (eg, in the treatment of moderate AD [10%–20% of patients]), they will represent a major direct cost to the health care system. Zimmermann et al37 showed in a cost-utility analysis that dupilumab improves health outcomes but with additional direct costs, and it is likely more cost-effective in patients with severe AD. Conversely, more efficient treatments may improve severe AD, reduce the need for hospitalization and recurrent doctors’ appointments as well as absence from work, and improve patient QOL,38 consequently decreasing indirect medical costs and disease burden. Ariëns et al39 showed in a recent registry-based study that dupilumab treatment induces a notable rise in work productivity and reduction of associated costs in patients with difficult-to-treat AD.

Conclusion

We aimed to analyze the economic burden of AD in Finland before the introduction of dupilumab. It will be interesting to see what the introduction of dupilumab and other novel systemic therapies have on total economic burden and medical costs. Most patients with AD in Finland can achieve disease control with topical treatments, but it is important to efficiently manage the patients who require additional supportive measures and specialist consultations, which may be challenging in the primary health care system because of the relapsing and remitting nature of the disease.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disease that may severely decrease quality of life (QOL) and lead to psychiatric comorbidities.1-3 Prior studies have indicated that AD causes a substantial economic burden, and disease severity has been proportionally linked to medical costs.4,5 Results of a multicenter cost-of-illness study from Germany estimated that a relapse of AD costs approximately €123 (US $136). The authors calculated the average annual cost of AD per patient to be €1425 (US $1580), whereas it is €956 (US $1060) in moderate disease and €2068 (US $2293) in severe disease (direct and indirect medical costs included).6 An observational cohort study from the Netherlands found that total direct cost per patient-year (PPY) was €4401 (US $4879) for patients with controlled AD vs €6993 (US $7756) for patients with uncontrolled AD.7

In a retrospective survey-based study, it was estimated that the annual cost of AD in Canada was approximately CAD $1.4 billion. The cost per patient varied from CAD $282 to CAD $1242 depending on disease severity.8 In another retrospective cohort study from the Netherlands, the average direct medical cost per patient with AD seeing a general practitioner was US $71 during follow-up in primary care. If the patient needed specialist consultation, the cost increased to an average of US $186.9

We aimed to assess the direct and indirect medical costs in adult patients with moderate to severe AD who attended a tertiary health care center in Finland. In addition, we evaluated the impact of AD on QOL in this patient cohort.

Methods

Study Design—Patients with AD who were treated at the Department of Dermatology and Allergology, Helsinki University Hospital, Finland, between February 2018 and December 2019 were randomly selected to participate in our survey study. All participants provided written informed consent. In Finland, patients with mild AD generally are treated in primary health care centers, and only patients with moderate to severe AD are referred to specialists and tertiary care centers. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, had AD confined to the hands, or reported the presence of other concomitant skin diseases that were being treated with topical or systemic therapies. The protocol for the study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Helsinki.

Questionnaire and Analysis of Disease Severity—The survey included the medical history, signs of atopy, former treatment(s) for AD, skin infections, visits to dermatologists or general practitioners, questions on mental health and hospitalization, and absence from work due to AD in the last 12 months. Disease severity was evaluated using the patient-oriented Rajka & Langeland eczema severity score and Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM).10,11 The impact on QOL was evaluated by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).12

Medication Costs—The cost of prescription drugs was based on data from the Finnish national electronic prescription center. In Finland, all prescriptions are made electronically in the database. We analyzed all topical medications (eg, topical corticosteroids [TCSs], topical calcineurin inhibitors [TCIs], and emollients) and systemic medicaments (eg, antibiotics, antihistamines, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and corticosteroids) prescribed for the treatment of AD. In Finland, dupilumab was introduced for the treatment of severe AD in early 2019, and patients receiving dupilumab were excluded from the study. Over-the-counter medications were not included. The costs for laboratory testing were estimations based on the standard monitoring protocols of the Helsinki University Hospital. All costs were based on the Finnish price level standard for the year 2019.

Inpatient/Outpatient Visits and Sick Leave Due to AD—The number of inpatient and outpatient visits due to AD in the last 12 months was evaluated. Outpatient specialist consultations or nurse appointments at Helsinki University Hospital were verified from electronic patient records. In addition, inpatient treatment and phototherapy sessions were calculated from the database.

We assessed the number of sick leave days from work or educational activities during the last year. All costs of transportation for doctors’ appointments, laboratory monitoring, and phototherapy treatments were summed together to estimate the total transportation cost. Visits to nurse and inpatient visits were not included in the total transportation cost because patients often were hospitalized directly after consultation visits, and nurse appointments often were combined with inpatient and outpatient visits. To calculate the total transportation cost, we used a rate of €0.43 per kilometer measured from the patients’ home addresses, which was the official compensation rate of the Finnish Tax Administration for 2019.13

Statistical Analysis—Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM). Descriptive analyses were used to describe baseline characteristics and to evaluate the mean costs of AD. The patients were divided into 2 groups according to POEM: (1) controlled AD (patients with clear skin or only mild AD; POEM score 0–7) and (2) uncontrolled AD (patients with moderate to very severe AD; POEM score 8–28). The Mann-Whitney U statistic was used to evaluate differences between the study groups.

Results

Patient Characteristics—One hundred sixty-seven patients answered the survey, of which 69 (41.3%) were males and 98 (58.7%) were females. There were 16 patients with controlled AD and 148 patients with uncontrolled AD. Three patients did not answer to POEM and were excluded. The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 and include self-reported symptoms related to atopy.

The most-used topical treatments were TCSs (n=155; 92.8%) and emollients (n=166; 99.4%). One hundred sixteen (69.5%) patients had used TCIs. The median amount of TCSs used was 300 g/y vs 30 g/y for TCIs (range, 0-5160 g/y) and 1200 g/y for emollients.

Fifteen (9.0%) patients had been hospitalized for AD in the last year. The mean (SD) length of hospitalization was 6.5 (2.8) days. Thirty-four (20.4%) patients received UVB phototherapy. Thirty-four (20.4%) patients were treated with at least 1 antibiotic course for secondary AD infection. Thirty-six (21.6%) patients needed at least 1 oral corticosteroid course for the treatment of an AD flare.