User login

February 2020

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Persistent Pruritic Papules on the Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), also known as Duhring disease, is a rare autoimmune disease. It is the cutaneous manifestation of gluten sensitivity with antibodies targeting epidermal transglutaminase.1 Symptoms of DH generally arise in the fourth decade of life, and children are less commonly affected,2 though the diagnosis should be considered at any age, as our patient was aged 19 years at the time of presentation. Dermatitis herpetiformis predominantly affects white individuals of Northern European heritage, and males more often are affected than females.2 There is a strong association with HLA-B8, HLA-DR3, and HLA-DQw2.3 It also is associated with other autoimmune disorders, including autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia.2

Clinically, DH is characterized by groups of intensely pruritic papulovesicles that are symmetrically located on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, scalp, nuchal area, back, and buttocks (quiz image). Less often, the groin also may be involved, as it was in our patient (Figure 1).4 Lesions can be papulovesicular or bullous, though they often are excoriated, and primary lesions may be difficult to identify.2 The disease may have spontaneous remissions with frequent relapses. Most patients with DH have an asymptomatic gluten-sensitive enteropathy.3

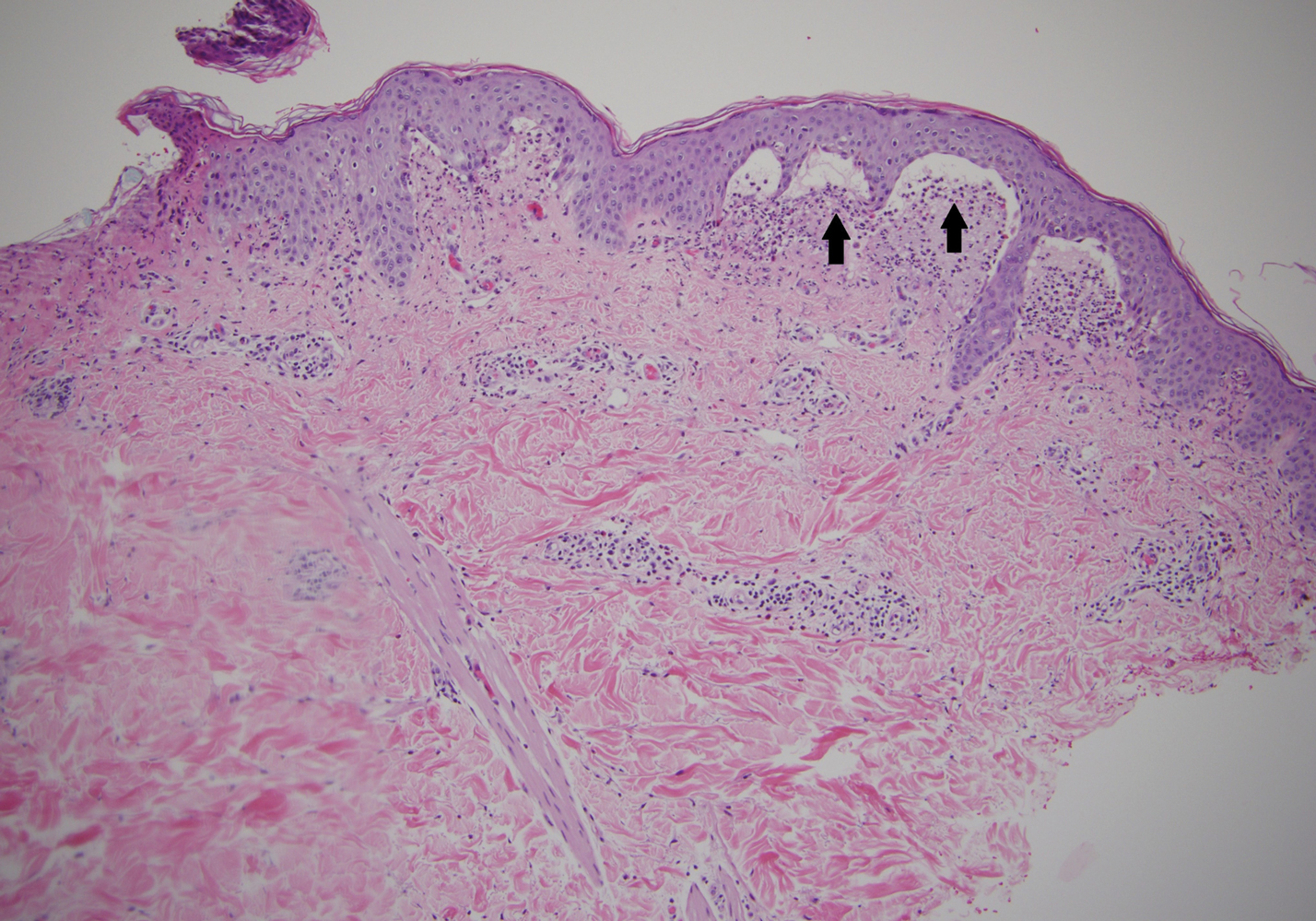

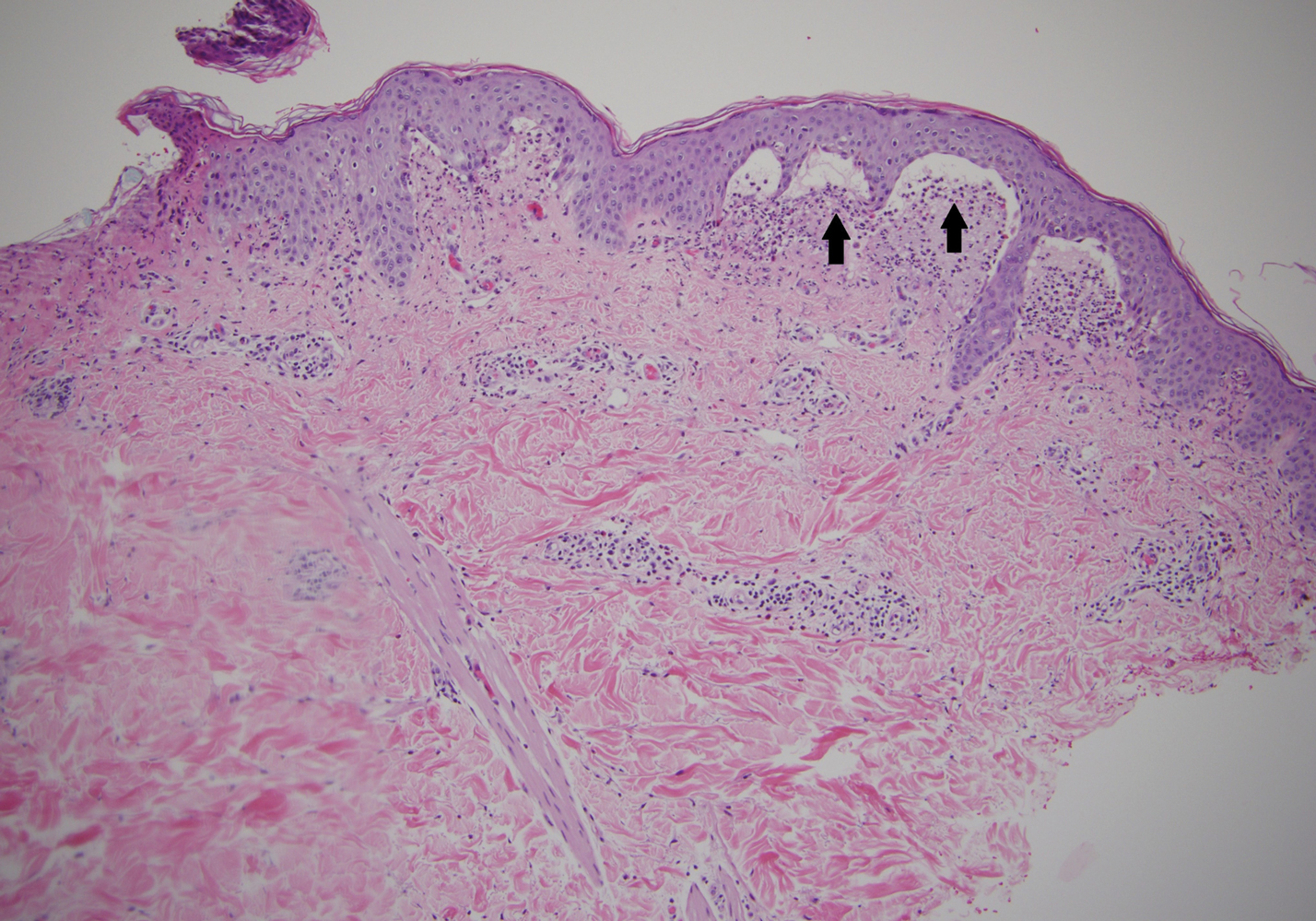

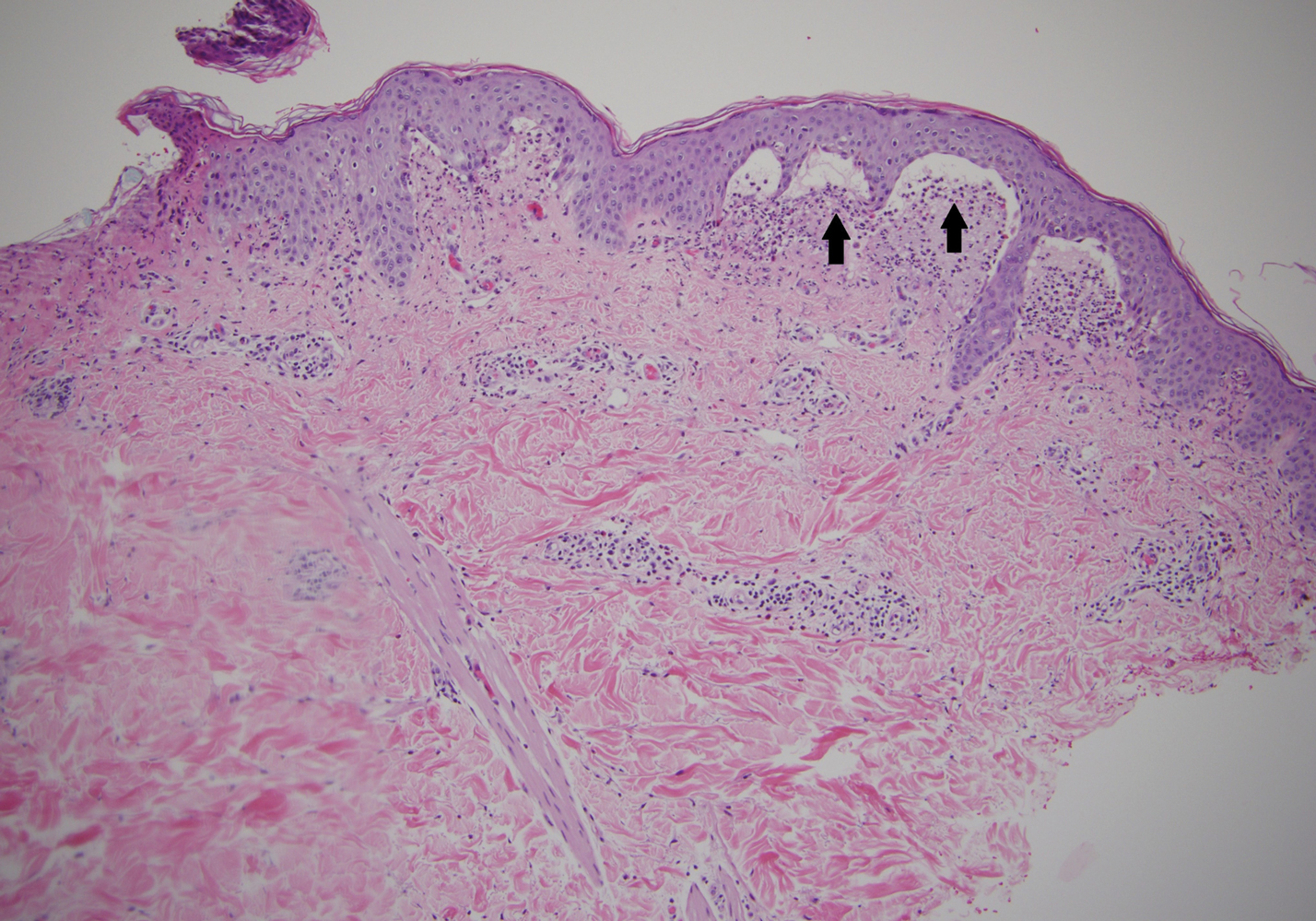

A punch biopsy of a representative nonexcoriated lesion from our patient showed the characteristic collections of neutrophils and fibrin at the tips of dermal papillae on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2). These findings are suggestive of DH.1 However, other bullous diseases, such as linear IgA dermatosis and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, may have similar appearance on histology.1 Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of perilesional skin is the gold standard for diagnosing DH, with a sensitivity and specificity close to 100%.1 Deposits of IgA generally are concentrated in previously involved skin or noninflamed perilesional skin; DIF of erythematous or lesional skin may be false negative.5 In our patient, DIF of perilesional uninvolved skin showed granular deposits of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction with accentuation in the dermal papillae (Figure 3), further suggestive of the diagnosis of DH.6

Patients with DH frequently will have specific IgA antibodies including anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG), anti-epidermal transglutaminase, antiendomysial antibodies, and anti-synthetic deamidated gliadin peptides.1 Only some of these tests are widely available, and the anti-tTG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is the least expensive and easiest to perform. A positive anti-tTG antibody test has a sensitivity ranging from 47% to 95% and a specificity greater than 90%.1 Our patient tested positive for anti-tTG and anti-deamidated synthetic gliadin-derived peptides. A diagnostic algorithm based on current evidence suggests that in patients with clinical evidence of DH, typical DIF findings combined with positive anti-tTG antibodies confirms the diagnosis of DH, as was seen in our patient.1,7 In situations where histopathology and/or antibody testing are inconclusive, additional testing to include HLA antigen typing, duodenal biopsy, and supplemental skin biopsies may be performed to help confirm or exclude a diagnosis of DH. It is unnecessary to perform a duodenal biopsy in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of DH, as DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease, and the diagnosis of DH is a diagnosis of celiac disease.1

Although pruritic papules may be found in several conditions, clinical, histopathologic, and DIF findings can help to confirm the diagnosis. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction causing eruptions of varying morphology, generally manifesting as pruritic scaly plaques that can occur anywhere on the body exposed to the offending allergen. Key histopathologic features of allergic contact dermatitis are eosinophilic spongiosis and exocytosis of eosinophils and lymphocytes.8 Papular urticaria is a hypersensitivity disorder to insect bites that consists of pruritic papules on exposed areas of skin, typically in children younger than 10 years. Genital and axillary areas usually are spared. The diagnosis is clinical.9 Recurrent herpes simplex virus infection is a short-lived outbreak that generally improves within 10 days. Herpes simplex virus infections usually are comprised of small vesicular or ulcerative lesions. Tzanck smear, skin biopsy, direct fluorescent antibody, viral culture, and polymerase chain reaction are diagnostic methods for herpes simplex virus.10 Scabies lesions typically are pruritic, erythematous, often excoriated papules and burrows located most commonly in the webs of fingers, wrists, axillae, areolae, waist, and genitalia. Diagnosis can be confirmed with scabies preparation (skin scraping showing mites, eggs, or feces), dermoscopy showing mites and burrows in vivo, or biopsy.11

First-line treatment in patients with DH and celiac disease is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD).1 A GFD will resolve the cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations and is the only thing that will reduce the risk for lymphoma and other diseases associated with gluten-induced enteropathy.1,2 A GFD alone will provide symptomatic relief over several months; dapsone and sulfapyridine can provide rapid relief of the pruritus and skin manifestations and usually can be weaned or discontinued after several months of following a strict GFD.12 Patients on sulfone therapy require regular follow-up and monitoring due to the risk for hemolytic anemia and other adverse effects as well as to determine the appropriate time to discontinue the medication.12 Although some patients are able to tolerate reintroduction of gluten into their diets after a period of remission, most will experience recurrent dermatologic manifestations if they continue to consume gluten.3

Because of our patient's impending move out of the area, no oral medications were started, and he was instructed to follow a GFD and seek medical care at his new location. The patient was contacted 6 months later and reported resolution of all skin lesions with just a GFD. The patient continued to follow-up with a dermatologist and gastroenterologist at his new location.

- Antiga E, Caproni M. The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:257-265.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatitis herpetiformis and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Vol 1. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Chronic blistering dermatoses. In: James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:453-474.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 1. epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1017-1024.

- Zone JJ, Meyer LJ, Petersen MJ. Deposition of granular IgA relative to clinical lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:912-918.

- Lever WF, Elder DE. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott; 2009.

- Hull C. Dermatitis herpetiformis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatitis-herpetiformis. Published October 14, 2016. Updated September 25, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

Yiannias J. Clinical features and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-allergic-contact-dermatitissearch=allergic%20contact%20dermatitis&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150

&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#H27385290. Updated May 17, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Goddard J, Stewart PH. Insect and other arthropod bites. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insect-and-other-arthropod-bites?search=papular%2urticaria§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H4&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~24&display_rank=1#

H4. Updated October 31, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Christine J, Wald A. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection?search=herpes%20simplex&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated July 23, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Goldstein B, Goldstein A. Scabies: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/scabies-epidemiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis?search=scabies&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~92&usagetype=default&display_rank=1. Updated August 2, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 2. diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1027-1033.

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), also known as Duhring disease, is a rare autoimmune disease. It is the cutaneous manifestation of gluten sensitivity with antibodies targeting epidermal transglutaminase.1 Symptoms of DH generally arise in the fourth decade of life, and children are less commonly affected,2 though the diagnosis should be considered at any age, as our patient was aged 19 years at the time of presentation. Dermatitis herpetiformis predominantly affects white individuals of Northern European heritage, and males more often are affected than females.2 There is a strong association with HLA-B8, HLA-DR3, and HLA-DQw2.3 It also is associated with other autoimmune disorders, including autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia.2

Clinically, DH is characterized by groups of intensely pruritic papulovesicles that are symmetrically located on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, scalp, nuchal area, back, and buttocks (quiz image). Less often, the groin also may be involved, as it was in our patient (Figure 1).4 Lesions can be papulovesicular or bullous, though they often are excoriated, and primary lesions may be difficult to identify.2 The disease may have spontaneous remissions with frequent relapses. Most patients with DH have an asymptomatic gluten-sensitive enteropathy.3

A punch biopsy of a representative nonexcoriated lesion from our patient showed the characteristic collections of neutrophils and fibrin at the tips of dermal papillae on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2). These findings are suggestive of DH.1 However, other bullous diseases, such as linear IgA dermatosis and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, may have similar appearance on histology.1 Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of perilesional skin is the gold standard for diagnosing DH, with a sensitivity and specificity close to 100%.1 Deposits of IgA generally are concentrated in previously involved skin or noninflamed perilesional skin; DIF of erythematous or lesional skin may be false negative.5 In our patient, DIF of perilesional uninvolved skin showed granular deposits of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction with accentuation in the dermal papillae (Figure 3), further suggestive of the diagnosis of DH.6

Patients with DH frequently will have specific IgA antibodies including anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG), anti-epidermal transglutaminase, antiendomysial antibodies, and anti-synthetic deamidated gliadin peptides.1 Only some of these tests are widely available, and the anti-tTG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is the least expensive and easiest to perform. A positive anti-tTG antibody test has a sensitivity ranging from 47% to 95% and a specificity greater than 90%.1 Our patient tested positive for anti-tTG and anti-deamidated synthetic gliadin-derived peptides. A diagnostic algorithm based on current evidence suggests that in patients with clinical evidence of DH, typical DIF findings combined with positive anti-tTG antibodies confirms the diagnosis of DH, as was seen in our patient.1,7 In situations where histopathology and/or antibody testing are inconclusive, additional testing to include HLA antigen typing, duodenal biopsy, and supplemental skin biopsies may be performed to help confirm or exclude a diagnosis of DH. It is unnecessary to perform a duodenal biopsy in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of DH, as DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease, and the diagnosis of DH is a diagnosis of celiac disease.1

Although pruritic papules may be found in several conditions, clinical, histopathologic, and DIF findings can help to confirm the diagnosis. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction causing eruptions of varying morphology, generally manifesting as pruritic scaly plaques that can occur anywhere on the body exposed to the offending allergen. Key histopathologic features of allergic contact dermatitis are eosinophilic spongiosis and exocytosis of eosinophils and lymphocytes.8 Papular urticaria is a hypersensitivity disorder to insect bites that consists of pruritic papules on exposed areas of skin, typically in children younger than 10 years. Genital and axillary areas usually are spared. The diagnosis is clinical.9 Recurrent herpes simplex virus infection is a short-lived outbreak that generally improves within 10 days. Herpes simplex virus infections usually are comprised of small vesicular or ulcerative lesions. Tzanck smear, skin biopsy, direct fluorescent antibody, viral culture, and polymerase chain reaction are diagnostic methods for herpes simplex virus.10 Scabies lesions typically are pruritic, erythematous, often excoriated papules and burrows located most commonly in the webs of fingers, wrists, axillae, areolae, waist, and genitalia. Diagnosis can be confirmed with scabies preparation (skin scraping showing mites, eggs, or feces), dermoscopy showing mites and burrows in vivo, or biopsy.11

First-line treatment in patients with DH and celiac disease is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD).1 A GFD will resolve the cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations and is the only thing that will reduce the risk for lymphoma and other diseases associated with gluten-induced enteropathy.1,2 A GFD alone will provide symptomatic relief over several months; dapsone and sulfapyridine can provide rapid relief of the pruritus and skin manifestations and usually can be weaned or discontinued after several months of following a strict GFD.12 Patients on sulfone therapy require regular follow-up and monitoring due to the risk for hemolytic anemia and other adverse effects as well as to determine the appropriate time to discontinue the medication.12 Although some patients are able to tolerate reintroduction of gluten into their diets after a period of remission, most will experience recurrent dermatologic manifestations if they continue to consume gluten.3

Because of our patient's impending move out of the area, no oral medications were started, and he was instructed to follow a GFD and seek medical care at his new location. The patient was contacted 6 months later and reported resolution of all skin lesions with just a GFD. The patient continued to follow-up with a dermatologist and gastroenterologist at his new location.

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), also known as Duhring disease, is a rare autoimmune disease. It is the cutaneous manifestation of gluten sensitivity with antibodies targeting epidermal transglutaminase.1 Symptoms of DH generally arise in the fourth decade of life, and children are less commonly affected,2 though the diagnosis should be considered at any age, as our patient was aged 19 years at the time of presentation. Dermatitis herpetiformis predominantly affects white individuals of Northern European heritage, and males more often are affected than females.2 There is a strong association with HLA-B8, HLA-DR3, and HLA-DQw2.3 It also is associated with other autoimmune disorders, including autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia.2

Clinically, DH is characterized by groups of intensely pruritic papulovesicles that are symmetrically located on the extensor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities, scalp, nuchal area, back, and buttocks (quiz image). Less often, the groin also may be involved, as it was in our patient (Figure 1).4 Lesions can be papulovesicular or bullous, though they often are excoriated, and primary lesions may be difficult to identify.2 The disease may have spontaneous remissions with frequent relapses. Most patients with DH have an asymptomatic gluten-sensitive enteropathy.3

A punch biopsy of a representative nonexcoriated lesion from our patient showed the characteristic collections of neutrophils and fibrin at the tips of dermal papillae on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2). These findings are suggestive of DH.1 However, other bullous diseases, such as linear IgA dermatosis and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, may have similar appearance on histology.1 Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of perilesional skin is the gold standard for diagnosing DH, with a sensitivity and specificity close to 100%.1 Deposits of IgA generally are concentrated in previously involved skin or noninflamed perilesional skin; DIF of erythematous or lesional skin may be false negative.5 In our patient, DIF of perilesional uninvolved skin showed granular deposits of IgA at the dermoepidermal junction with accentuation in the dermal papillae (Figure 3), further suggestive of the diagnosis of DH.6

Patients with DH frequently will have specific IgA antibodies including anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG), anti-epidermal transglutaminase, antiendomysial antibodies, and anti-synthetic deamidated gliadin peptides.1 Only some of these tests are widely available, and the anti-tTG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is the least expensive and easiest to perform. A positive anti-tTG antibody test has a sensitivity ranging from 47% to 95% and a specificity greater than 90%.1 Our patient tested positive for anti-tTG and anti-deamidated synthetic gliadin-derived peptides. A diagnostic algorithm based on current evidence suggests that in patients with clinical evidence of DH, typical DIF findings combined with positive anti-tTG antibodies confirms the diagnosis of DH, as was seen in our patient.1,7 In situations where histopathology and/or antibody testing are inconclusive, additional testing to include HLA antigen typing, duodenal biopsy, and supplemental skin biopsies may be performed to help confirm or exclude a diagnosis of DH. It is unnecessary to perform a duodenal biopsy in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of DH, as DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease, and the diagnosis of DH is a diagnosis of celiac disease.1

Although pruritic papules may be found in several conditions, clinical, histopathologic, and DIF findings can help to confirm the diagnosis. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction causing eruptions of varying morphology, generally manifesting as pruritic scaly plaques that can occur anywhere on the body exposed to the offending allergen. Key histopathologic features of allergic contact dermatitis are eosinophilic spongiosis and exocytosis of eosinophils and lymphocytes.8 Papular urticaria is a hypersensitivity disorder to insect bites that consists of pruritic papules on exposed areas of skin, typically in children younger than 10 years. Genital and axillary areas usually are spared. The diagnosis is clinical.9 Recurrent herpes simplex virus infection is a short-lived outbreak that generally improves within 10 days. Herpes simplex virus infections usually are comprised of small vesicular or ulcerative lesions. Tzanck smear, skin biopsy, direct fluorescent antibody, viral culture, and polymerase chain reaction are diagnostic methods for herpes simplex virus.10 Scabies lesions typically are pruritic, erythematous, often excoriated papules and burrows located most commonly in the webs of fingers, wrists, axillae, areolae, waist, and genitalia. Diagnosis can be confirmed with scabies preparation (skin scraping showing mites, eggs, or feces), dermoscopy showing mites and burrows in vivo, or biopsy.11

First-line treatment in patients with DH and celiac disease is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD).1 A GFD will resolve the cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations and is the only thing that will reduce the risk for lymphoma and other diseases associated with gluten-induced enteropathy.1,2 A GFD alone will provide symptomatic relief over several months; dapsone and sulfapyridine can provide rapid relief of the pruritus and skin manifestations and usually can be weaned or discontinued after several months of following a strict GFD.12 Patients on sulfone therapy require regular follow-up and monitoring due to the risk for hemolytic anemia and other adverse effects as well as to determine the appropriate time to discontinue the medication.12 Although some patients are able to tolerate reintroduction of gluten into their diets after a period of remission, most will experience recurrent dermatologic manifestations if they continue to consume gluten.3

Because of our patient's impending move out of the area, no oral medications were started, and he was instructed to follow a GFD and seek medical care at his new location. The patient was contacted 6 months later and reported resolution of all skin lesions with just a GFD. The patient continued to follow-up with a dermatologist and gastroenterologist at his new location.

- Antiga E, Caproni M. The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:257-265.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatitis herpetiformis and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Vol 1. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Chronic blistering dermatoses. In: James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:453-474.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 1. epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1017-1024.

- Zone JJ, Meyer LJ, Petersen MJ. Deposition of granular IgA relative to clinical lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:912-918.

- Lever WF, Elder DE. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott; 2009.

- Hull C. Dermatitis herpetiformis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatitis-herpetiformis. Published October 14, 2016. Updated September 25, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

Yiannias J. Clinical features and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-allergic-contact-dermatitissearch=allergic%20contact%20dermatitis&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150

&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#H27385290. Updated May 17, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Goddard J, Stewart PH. Insect and other arthropod bites. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insect-and-other-arthropod-bites?search=papular%2urticaria§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H4&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~24&display_rank=1#

H4. Updated October 31, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Christine J, Wald A. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection?search=herpes%20simplex&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated July 23, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Goldstein B, Goldstein A. Scabies: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/scabies-epidemiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis?search=scabies&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~92&usagetype=default&display_rank=1. Updated August 2, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 2. diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1027-1033.

- Antiga E, Caproni M. The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:257-265.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatitis herpetiformis and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Vol 1. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al. Chronic blistering dermatoses. In: James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:453-474.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 1. epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1017-1024.

- Zone JJ, Meyer LJ, Petersen MJ. Deposition of granular IgA relative to clinical lesions in dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:912-918.

- Lever WF, Elder DE. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott; 2009.

- Hull C. Dermatitis herpetiformis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatitis-herpetiformis. Published October 14, 2016. Updated September 25, 2019. Accessed December 10, 2019.

Yiannias J. Clinical features and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-allergic-contact-dermatitissearch=allergic%20contact%20dermatitis&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150

&usage_type=default&display_rank=2#H27385290. Updated May 17, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Goddard J, Stewart PH. Insect and other arthropod bites. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insect-and-other-arthropod-bites?search=papular%2urticaria§ionRank=1&usage_type=default&anchor=H4&source=machineLearning&selectedTitle=1~24&display_rank=1#

H4. Updated October 31, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.Christine J, Wald A. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-herpes-simplex-virus-type-1-infection?search=herpes%20simplex&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Updated July 23, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Goldstein B, Goldstein A. Scabies: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/scabies-epidemiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis?search=scabies&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~92&usagetype=default&display_rank=1. Updated August 2, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Bolotin D, Petronic-Rosic V. Dermatitis herpetiformis. part 2. diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1027-1033.

A 19-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with intermittent pruritic lesions that began on the bilateral buttocks when he was living in Reserve Officers' Training Corps dormitories several months prior. The eruption then spread to involve the penis, suprapubic area, periumbilical area, and flanks. The patient attempted to treat the lesions with topical antifungals prior to evaluation in the emergency department where he was treated with permethrin 5% on 2 separate occasions without any improvement. A medical history was normal, and he denied recent travel, animal contacts, or new medications. Physical examination revealed several 2- to 4-mm erythematous papules and superficial erosions with an ill-defined erythematous background most notable on the penis, suprapubic area, periumbilical area, flanks, and buttocks.

VEDOSS study describes predictors of progression to systemic sclerosis

ATLANTA – , according to recent results from the Very Early Diagnosis Of Systemic Sclerosis (VEDOSS) study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Our data show that thanks [to a] combination of the signs that characterize the various phases of the disease, patients can be diagnosed [with systemic sclerosis] in the very early stages,” first author Silvia Bellando-Randone, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the division of rheumatology at the University of Florence (Italy), said in her presentation.

Dr. Bellando-Randone and colleagues performed a longitudinal, observational study of 742 patients (mean 45.7 years old) at 42 centers in a cohort of mostly women (90%), nearly all of whom had had Raynaud’s phenomenon for longer than 36 months (97.5%). Patients were excluded if they had systemic sclerosis based on ACR 1980 classification criteria and/or ACR–European League Against Rheumatism 2013 criteria, had systemic sclerosis together with other connective-tissue diseases, or were unlikely to be present for three consecutive annual exams. Data collection began in March 2012 with follow-up of 5 years.

The researchers determined the positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) of clinical features, systemic sclerosis–specific antibodies, and nailfold video capillaroscopy (NVC) abnormalities on progression from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis. Laboratory data collected at baseline included presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anticentromere antibodies (ACA), anti-DNA topoisomerase I antibodies (anti-Scl-70), anti-U1RNP antibodies, anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies (ARA), N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptides (NT-proBNP), and C-reactive protein/erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Dr. Bellando-Randone and colleagues also collected clinical, pulmonary function, lung high-resolution CT, echocardiographic, and ECG data at baseline.

Predictions were based on these factors alone and in combination. Overall, 65% of patients had positive ANA. Other baseline characteristics present in patients that predicted systemic sclerosis included positive ACA/anti-Scl-70/ARA (32%), NVC abnormalities such as giant capillaries (25%), and puffy fingers (17%).

Using Kaplan-Meier analysis, the researchers found 7.4% of 401 patients who were ANA positive progressed to meet ACR-EULAR 2013 criteria, and the percentage of these patients increased to 29.3% at 3 years and 44.1% at 5 years. When the researchers considered disease-specific antibodies alone, 10.6% of 90 patients progressed from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis within 1 year, 39.6% within 3 years, and 50.3% within 5 years. When the researchers analyzed disease-specific antibodies and NVC abnormalities together, 16% of 72 patients progressed to systemic sclerosis within 1 year, 61.7% within 3 years, and 77.4% within 5 years.

Puffy fingers also were a predictor of progression, and 14.4% of 69 patients with puffy fingers alone progressed from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis at 1 year, 47.7% at 3 years, and 67.9% at 5 years. Considering puffy fingers and disease-specific antibodies together, 20% of 27 patients progressed at 1 year, 56.3% at 3 years, and 91.3% at 5 years. No patients with puffy fingers together and NVC abnormalities progressed to systemic sclerosis at 1 year, but 60.4% of 22 patients progressed at 3 years before plateauing at 5 years. For patients with NVC abnormalities alone, 7.1% progressed to systemic sclerosis from Raynaud’s phenomenon at 1 year, 39.4% at 3 years, and 52.7% at 5 years.

“Regarding capillaroscopy, we have to say that not all centers that participated were equally screened in capillaroscopy, and so we cannot assume the accuracy of this data,” she said.

Dr. Bellando-Randone noted that, apart from puffy fingers, disease-specific antibodies, and NVC abnormalities, patients were more likely to have a history of esophageal symptoms if they progressed to systemic sclerosis (37.3%), compared with patients who did not progress (23.6%; P = .003).

Puffy fingers alone were an independent predictor of systemic sclerosis (PPV, 78.9%; NPV, 45.1%) as well as in combination with disease-specific antibodies (PPV, 94.1%; NPV, 43.9%). The combination of disease-specific antibodies plus NVC abnormalities also independently predicted progression to systemic sclerosis (PPV, 82.2%; NPV, 50.4%). In a Cox multivariate analysis, disease-specific antibodies (relative risk, 5.4; 95% confidence interval, 3.7-7.9) and puffy fingers (RR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.0-4.4) together were strongly predictive of progression from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis (RR, 4.3; 95% CI, 2.6-7.3).

“This is really important for the risk stratification of patients [in] the very early stages of the disease, even if these data should be corroborated by larger data in larger studies in the future,” said Dr. Bellando-Randone.

The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bellando-Randone S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 2914.

ATLANTA – , according to recent results from the Very Early Diagnosis Of Systemic Sclerosis (VEDOSS) study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Our data show that thanks [to a] combination of the signs that characterize the various phases of the disease, patients can be diagnosed [with systemic sclerosis] in the very early stages,” first author Silvia Bellando-Randone, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the division of rheumatology at the University of Florence (Italy), said in her presentation.

Dr. Bellando-Randone and colleagues performed a longitudinal, observational study of 742 patients (mean 45.7 years old) at 42 centers in a cohort of mostly women (90%), nearly all of whom had had Raynaud’s phenomenon for longer than 36 months (97.5%). Patients were excluded if they had systemic sclerosis based on ACR 1980 classification criteria and/or ACR–European League Against Rheumatism 2013 criteria, had systemic sclerosis together with other connective-tissue diseases, or were unlikely to be present for three consecutive annual exams. Data collection began in March 2012 with follow-up of 5 years.

The researchers determined the positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) of clinical features, systemic sclerosis–specific antibodies, and nailfold video capillaroscopy (NVC) abnormalities on progression from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis. Laboratory data collected at baseline included presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anticentromere antibodies (ACA), anti-DNA topoisomerase I antibodies (anti-Scl-70), anti-U1RNP antibodies, anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies (ARA), N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptides (NT-proBNP), and C-reactive protein/erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Dr. Bellando-Randone and colleagues also collected clinical, pulmonary function, lung high-resolution CT, echocardiographic, and ECG data at baseline.

Predictions were based on these factors alone and in combination. Overall, 65% of patients had positive ANA. Other baseline characteristics present in patients that predicted systemic sclerosis included positive ACA/anti-Scl-70/ARA (32%), NVC abnormalities such as giant capillaries (25%), and puffy fingers (17%).

Using Kaplan-Meier analysis, the researchers found 7.4% of 401 patients who were ANA positive progressed to meet ACR-EULAR 2013 criteria, and the percentage of these patients increased to 29.3% at 3 years and 44.1% at 5 years. When the researchers considered disease-specific antibodies alone, 10.6% of 90 patients progressed from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis within 1 year, 39.6% within 3 years, and 50.3% within 5 years. When the researchers analyzed disease-specific antibodies and NVC abnormalities together, 16% of 72 patients progressed to systemic sclerosis within 1 year, 61.7% within 3 years, and 77.4% within 5 years.

Puffy fingers also were a predictor of progression, and 14.4% of 69 patients with puffy fingers alone progressed from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis at 1 year, 47.7% at 3 years, and 67.9% at 5 years. Considering puffy fingers and disease-specific antibodies together, 20% of 27 patients progressed at 1 year, 56.3% at 3 years, and 91.3% at 5 years. No patients with puffy fingers together and NVC abnormalities progressed to systemic sclerosis at 1 year, but 60.4% of 22 patients progressed at 3 years before plateauing at 5 years. For patients with NVC abnormalities alone, 7.1% progressed to systemic sclerosis from Raynaud’s phenomenon at 1 year, 39.4% at 3 years, and 52.7% at 5 years.

“Regarding capillaroscopy, we have to say that not all centers that participated were equally screened in capillaroscopy, and so we cannot assume the accuracy of this data,” she said.

Dr. Bellando-Randone noted that, apart from puffy fingers, disease-specific antibodies, and NVC abnormalities, patients were more likely to have a history of esophageal symptoms if they progressed to systemic sclerosis (37.3%), compared with patients who did not progress (23.6%; P = .003).

Puffy fingers alone were an independent predictor of systemic sclerosis (PPV, 78.9%; NPV, 45.1%) as well as in combination with disease-specific antibodies (PPV, 94.1%; NPV, 43.9%). The combination of disease-specific antibodies plus NVC abnormalities also independently predicted progression to systemic sclerosis (PPV, 82.2%; NPV, 50.4%). In a Cox multivariate analysis, disease-specific antibodies (relative risk, 5.4; 95% confidence interval, 3.7-7.9) and puffy fingers (RR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.0-4.4) together were strongly predictive of progression from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis (RR, 4.3; 95% CI, 2.6-7.3).

“This is really important for the risk stratification of patients [in] the very early stages of the disease, even if these data should be corroborated by larger data in larger studies in the future,” said Dr. Bellando-Randone.

The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bellando-Randone S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 2914.

ATLANTA – , according to recent results from the Very Early Diagnosis Of Systemic Sclerosis (VEDOSS) study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Our data show that thanks [to a] combination of the signs that characterize the various phases of the disease, patients can be diagnosed [with systemic sclerosis] in the very early stages,” first author Silvia Bellando-Randone, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the division of rheumatology at the University of Florence (Italy), said in her presentation.

Dr. Bellando-Randone and colleagues performed a longitudinal, observational study of 742 patients (mean 45.7 years old) at 42 centers in a cohort of mostly women (90%), nearly all of whom had had Raynaud’s phenomenon for longer than 36 months (97.5%). Patients were excluded if they had systemic sclerosis based on ACR 1980 classification criteria and/or ACR–European League Against Rheumatism 2013 criteria, had systemic sclerosis together with other connective-tissue diseases, or were unlikely to be present for three consecutive annual exams. Data collection began in March 2012 with follow-up of 5 years.

The researchers determined the positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) of clinical features, systemic sclerosis–specific antibodies, and nailfold video capillaroscopy (NVC) abnormalities on progression from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis. Laboratory data collected at baseline included presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anticentromere antibodies (ACA), anti-DNA topoisomerase I antibodies (anti-Scl-70), anti-U1RNP antibodies, anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies (ARA), N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptides (NT-proBNP), and C-reactive protein/erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Dr. Bellando-Randone and colleagues also collected clinical, pulmonary function, lung high-resolution CT, echocardiographic, and ECG data at baseline.

Predictions were based on these factors alone and in combination. Overall, 65% of patients had positive ANA. Other baseline characteristics present in patients that predicted systemic sclerosis included positive ACA/anti-Scl-70/ARA (32%), NVC abnormalities such as giant capillaries (25%), and puffy fingers (17%).

Using Kaplan-Meier analysis, the researchers found 7.4% of 401 patients who were ANA positive progressed to meet ACR-EULAR 2013 criteria, and the percentage of these patients increased to 29.3% at 3 years and 44.1% at 5 years. When the researchers considered disease-specific antibodies alone, 10.6% of 90 patients progressed from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis within 1 year, 39.6% within 3 years, and 50.3% within 5 years. When the researchers analyzed disease-specific antibodies and NVC abnormalities together, 16% of 72 patients progressed to systemic sclerosis within 1 year, 61.7% within 3 years, and 77.4% within 5 years.

Puffy fingers also were a predictor of progression, and 14.4% of 69 patients with puffy fingers alone progressed from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis at 1 year, 47.7% at 3 years, and 67.9% at 5 years. Considering puffy fingers and disease-specific antibodies together, 20% of 27 patients progressed at 1 year, 56.3% at 3 years, and 91.3% at 5 years. No patients with puffy fingers together and NVC abnormalities progressed to systemic sclerosis at 1 year, but 60.4% of 22 patients progressed at 3 years before plateauing at 5 years. For patients with NVC abnormalities alone, 7.1% progressed to systemic sclerosis from Raynaud’s phenomenon at 1 year, 39.4% at 3 years, and 52.7% at 5 years.

“Regarding capillaroscopy, we have to say that not all centers that participated were equally screened in capillaroscopy, and so we cannot assume the accuracy of this data,” she said.

Dr. Bellando-Randone noted that, apart from puffy fingers, disease-specific antibodies, and NVC abnormalities, patients were more likely to have a history of esophageal symptoms if they progressed to systemic sclerosis (37.3%), compared with patients who did not progress (23.6%; P = .003).

Puffy fingers alone were an independent predictor of systemic sclerosis (PPV, 78.9%; NPV, 45.1%) as well as in combination with disease-specific antibodies (PPV, 94.1%; NPV, 43.9%). The combination of disease-specific antibodies plus NVC abnormalities also independently predicted progression to systemic sclerosis (PPV, 82.2%; NPV, 50.4%). In a Cox multivariate analysis, disease-specific antibodies (relative risk, 5.4; 95% confidence interval, 3.7-7.9) and puffy fingers (RR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.0-4.4) together were strongly predictive of progression from Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis (RR, 4.3; 95% CI, 2.6-7.3).

“This is really important for the risk stratification of patients [in] the very early stages of the disease, even if these data should be corroborated by larger data in larger studies in the future,” said Dr. Bellando-Randone.

The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bellando-Randone S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 2914.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

TULIP trials show clinical benefit of anifrolumab for SLE

ATLANTA –

In TULIP-1, which compared intravenous anifrolumab at doses of 300 or 150 mg and placebo given every 4 weeks for 48 weeks, the primary endpoint of SLE Responder Index (SRI) in the 300 mg versus the placebo group was not met, but in post hoc analyses, numeric improvements at thresholds associated with clinical benefit were observed for several secondary outcomes, Richard A. Furie, MD, a professor of medicine at the Hofstra University/Northwell, Hempstead, N.Y., reported during a plenary session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The findings were published online Nov. 11 in Lancet Rheumatology.

TULIP-2 compared IV anifrolumab at a dose of 300 mg versus placebo every 4 weeks for 48 weeks and demonstrated the superiority of anifrolumab for multiple efficacy endpoints, including the primary study endpoint of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG)-based Composite Lupus Assessment (BICLA), Eric F. Morand, MD, PhD, reported during a late-breaking abstract session at the meeting.

The double-blind, phase 3 TULIP trials each enrolled seropositive SLE patients with moderate to severe active disease despite standard-of-care therapy (SOC). All patients met ACR criteria, had a SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI)-2K of 6 or greater, and BILAG index scoring showing one or more organ systems with grade A involvement or two or more with grade B. Both trials required stable SOC therapy throughout the study except for mandatory attempts at oral corticosteroid (OCS) tapering for patients who were receiving 10 mg/day or more of prednisone or its equivalent at study entry.

The trials followed a phase 2 trial, reported by Dr. Furie at the 2015 ACR meeting and published in Arthritis & Rheumatology in 2017, which showed “very robust” efficacy of anifrolumab in this setting.

“The burning question for the last 20 years has been, ‘Can type 1 interferon inhibitors actually reduce lupus clinical activity?’ ” Dr. Furie said. “The problem here [is that] you can inhibit interferon-alpha, but there are four other subtypes capable of binding to the interferon receptor.”

Anifrolumab, which was first studied in scleroderma, inhibits the interferon (IFN) receptor, thereby providing broader inhibition than strategies that specifically target interferon-alpha, he explained.

In the phase 2 trial, the primary composite endpoint of SRI response at day 169 and sustained reduction of OCS dose between days 85 and 169 was met by 51.5% of patients receiving 300 mg of anifrolumab versus 26.6% of those receiving placebo.

TULIP-1

The TULIP-1 trial, however, failed to show a significant difference in the primary endpoint of week 52 SRI, although initial analyses showed some numeric benefit with respect to BICLA, OCS dose reductions, and other organ-specific endpoints.

The percentage of SRI responders at week 52 in the double-blind trial was 36.2% in 180 patients who received 300 mg anifrolumab vs. 40.4% in 184 who received placebo (nominal P value = .41), and in a subgroup of patients who had high IFN gene signature (IFNGS) test results, the rates were 35.9% and 39.3% (nominal P value = 0.55), respectively.

Sustained OCS reduction to 7.5 mg/day or less occurred in 41% of anifrolumab and 32.1% of placebo group patients, and a 50% or greater reduction in Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Severity Index (CLASI) activity from baseline to week 12 occurred in 41.9% and 24.9%, respectively. The annualized flare rate to week 52 was 0.72 for anifrolumab and 0.60 for placebo.

BICLA response at week 52 was 37.1% with anifrolumab versus 27% with placebo, and a 50% or greater reduction in active joints from baseline to week 52 occurred in 47% versus 32.5% of patients in the groups, respectively.

The 150-mg dose, which was included to provide dose-response data, did not show efficacy in secondary outcomes.

“We see a delta of about 10 percentage points [for BICLA], and about a 15-percentage point change [in swollen and tender joint count] in favor of anifrolumab,” Dr. Furie said. “So why the big difference between phase 2 results and phase 3 results? Well, that led to a year-long interrogation of all the data ... [which revealed that] about 8% of patients were misclassified as nonresponders for [NSAID] use.”

The medication rules in the study automatically required any patient who used a restricted drug, including NSAIDs, to be classified as a nonresponder. That means a patient who took an NSAID for a headache at the beginning of the study, for example, would have been considered a nonresponder regardless of their outcome, he explained.

“This led to a review of all the restricted medication classification rules, and after unblinding, a meeting was convened with SLE experts and the sponsors to actually revise the medication rules just to make them clinically more appropriate. The key analyses were repeated post hoc,” he said.

The difference between the treatment and placebo groups in terms of the week 52 SRI didn’t change much in the post hoc analysis (46.9% vs. 43% of treatment and placebo patients, respectively, met the endpoint). Similarly, SRI rates in the IFNGS test–high subgroup were 48.2% and 41.8%, respectively.

However, more pronounced “shifts to the right,” indicating larger differences favoring anifrolumab over placebo, were seen for OCS dose reduction (48.8% vs. 32.1%), CLASI response (43.6% vs. 24.9%), and BICLA response (48.1% vs. 29.8%).

“For BICLA response, we see a fairly significant change ... with what appears to be a clinically significant delta (about 16 percentage points), and as far as the change in active joints, also very significant in my eyes,” he said.

Also of note, the time to BICLA response sustained to week 52 was improved with anifrolumab (hazard ratio, 1.93), and CLASI response differences emerged early, at about 12 weeks, he said.

The type 1 IFNGS was reduced by a median of 88% to 90% in the anifrolumab groups vs. with placebo, and modest changes in serologies were also noted.

Serious adverse events occurred in 13.9% and 10.8% of patients in the anifrolumab 300- and 150-mg arms, compared with 16.3% in the placebo arm. Herpes zoster was more common in the anifrolumab groups (5.6% for 300 mg and 5.4% for 150 mg vs. 1.6% for placebo).

“But other than that, no major standouts as far as the safety profile,” Dr. Furie said.

The findings, particularly after the medication rules were amended, suggest efficacy of anifrolumab for corticosteroid reductions, skin activity, BICLA, and joint scores, he said, noting that corticosteroid dose reductions are very important for patients, and that BICLA is “actually a very rigorous composite.”

Importantly, the findings also underscore the importance and impact of medication rules, and the critical role that endpoint selection plays in SLE trials.

“We’ve been seeing discordance lately between the SRI and BICLA ... so [there is] still a lot to learn,” he said. “And I think it’s important in evaluating the drug effect to look at the totality of the data.”

TULIP-2

BICLA response, the primary endpoint of TULIP-2, was achieved by 47.8% of 180 patients who received anifrolumab, compared with 31.5% of 182 who received placebo, said Dr. Morand, professor and head of the School of Clinical Sciences at Monash University, Melbourne.

“The effect size was 16.3 percentage points with an adjusted p value of 0.001. Therefore, the primary outcome of this trial was attained,” said Dr. Morand, who also is head of the Monash Health Rheumatology Unit. “Separation between the treatment arms occurred early and was maintained across the progression of the trial.”

Anifrolumab was also superior to placebo for key secondary endpoints, including OCS dose reduction to 7.5 mg/day or less (51.5% vs. 30.2%) and CLASI response (49.0% vs. 25.0%).

“Joint responses did not show a significant difference between the anifrolumab and placebo arms,” he said, adding that the annualized flare rate also did not differ significantly between the groups, but was numerically lower in anifrolumab-treated patients (0.43 vs. 0.64; rate ratio, 0.67; P = .081).

Numeric differences also favored anifrolumab for multiple secondary endpoints, including SRI responses, time to onset of BICLA-sustained response, and time to first flare, he noted.

Further, in patients with high baseline IFNGS, anifrolumab induced neutralization of IFNGS by week 12, with a median suppression of 88.0%, which persisted for the duration of the study; no such effect was seen in the placebo arm.

Serum anti–double stranded DNA also trended toward normalization with anifrolumab.

The safety profile of anifrolumab was similar to that seen in previous trials, including TULIP-1, with herpes zoster occurring more often in those receiving anifrolumab (7.2% vs. 1.1% in the placebo group), Dr. Morand said, noting that “all herpes zoster episodes were cutaneous, all responded to antiviral therapy, and none required [treatment] discontinuation.”

Serious adverse events, including pneumonia and SLE worsening, occurred less frequently in the anifrolumab arm (8.3% vs. 17.0%, respectively), as did adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation (2.8% and 7.1%). One death occurred in the anifrolumab group from community-acquired pneumonia, and few patients (0.6%) developed antidrug antibodies.

No new safety signals were identified, he said, noting that “the findings add to cumulative evidence identifying anifrolumab as a potential new treatment option for SLE.”

“In conclusion, TULIP-2 was a positive phase 3 trial in lupus, and there aren’t many times that that sentence has been spoken,” he said.

The TULIP-1 and -2 trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Furie And Dr. Morand both reported grant/research support and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, as well as speaker’s bureau participation for AstraZeneca.

SOURCES: Furie RA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1763; Morand EF et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract L17.

ATLANTA –

In TULIP-1, which compared intravenous anifrolumab at doses of 300 or 150 mg and placebo given every 4 weeks for 48 weeks, the primary endpoint of SLE Responder Index (SRI) in the 300 mg versus the placebo group was not met, but in post hoc analyses, numeric improvements at thresholds associated with clinical benefit were observed for several secondary outcomes, Richard A. Furie, MD, a professor of medicine at the Hofstra University/Northwell, Hempstead, N.Y., reported during a plenary session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The findings were published online Nov. 11 in Lancet Rheumatology.

TULIP-2 compared IV anifrolumab at a dose of 300 mg versus placebo every 4 weeks for 48 weeks and demonstrated the superiority of anifrolumab for multiple efficacy endpoints, including the primary study endpoint of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG)-based Composite Lupus Assessment (BICLA), Eric F. Morand, MD, PhD, reported during a late-breaking abstract session at the meeting.

The double-blind, phase 3 TULIP trials each enrolled seropositive SLE patients with moderate to severe active disease despite standard-of-care therapy (SOC). All patients met ACR criteria, had a SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI)-2K of 6 or greater, and BILAG index scoring showing one or more organ systems with grade A involvement or two or more with grade B. Both trials required stable SOC therapy throughout the study except for mandatory attempts at oral corticosteroid (OCS) tapering for patients who were receiving 10 mg/day or more of prednisone or its equivalent at study entry.

The trials followed a phase 2 trial, reported by Dr. Furie at the 2015 ACR meeting and published in Arthritis & Rheumatology in 2017, which showed “very robust” efficacy of anifrolumab in this setting.

“The burning question for the last 20 years has been, ‘Can type 1 interferon inhibitors actually reduce lupus clinical activity?’ ” Dr. Furie said. “The problem here [is that] you can inhibit interferon-alpha, but there are four other subtypes capable of binding to the interferon receptor.”

Anifrolumab, which was first studied in scleroderma, inhibits the interferon (IFN) receptor, thereby providing broader inhibition than strategies that specifically target interferon-alpha, he explained.

In the phase 2 trial, the primary composite endpoint of SRI response at day 169 and sustained reduction of OCS dose between days 85 and 169 was met by 51.5% of patients receiving 300 mg of anifrolumab versus 26.6% of those receiving placebo.

TULIP-1

The TULIP-1 trial, however, failed to show a significant difference in the primary endpoint of week 52 SRI, although initial analyses showed some numeric benefit with respect to BICLA, OCS dose reductions, and other organ-specific endpoints.

The percentage of SRI responders at week 52 in the double-blind trial was 36.2% in 180 patients who received 300 mg anifrolumab vs. 40.4% in 184 who received placebo (nominal P value = .41), and in a subgroup of patients who had high IFN gene signature (IFNGS) test results, the rates were 35.9% and 39.3% (nominal P value = 0.55), respectively.

Sustained OCS reduction to 7.5 mg/day or less occurred in 41% of anifrolumab and 32.1% of placebo group patients, and a 50% or greater reduction in Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Severity Index (CLASI) activity from baseline to week 12 occurred in 41.9% and 24.9%, respectively. The annualized flare rate to week 52 was 0.72 for anifrolumab and 0.60 for placebo.

BICLA response at week 52 was 37.1% with anifrolumab versus 27% with placebo, and a 50% or greater reduction in active joints from baseline to week 52 occurred in 47% versus 32.5% of patients in the groups, respectively.

The 150-mg dose, which was included to provide dose-response data, did not show efficacy in secondary outcomes.

“We see a delta of about 10 percentage points [for BICLA], and about a 15-percentage point change [in swollen and tender joint count] in favor of anifrolumab,” Dr. Furie said. “So why the big difference between phase 2 results and phase 3 results? Well, that led to a year-long interrogation of all the data ... [which revealed that] about 8% of patients were misclassified as nonresponders for [NSAID] use.”

The medication rules in the study automatically required any patient who used a restricted drug, including NSAIDs, to be classified as a nonresponder. That means a patient who took an NSAID for a headache at the beginning of the study, for example, would have been considered a nonresponder regardless of their outcome, he explained.

“This led to a review of all the restricted medication classification rules, and after unblinding, a meeting was convened with SLE experts and the sponsors to actually revise the medication rules just to make them clinically more appropriate. The key analyses were repeated post hoc,” he said.

The difference between the treatment and placebo groups in terms of the week 52 SRI didn’t change much in the post hoc analysis (46.9% vs. 43% of treatment and placebo patients, respectively, met the endpoint). Similarly, SRI rates in the IFNGS test–high subgroup were 48.2% and 41.8%, respectively.

However, more pronounced “shifts to the right,” indicating larger differences favoring anifrolumab over placebo, were seen for OCS dose reduction (48.8% vs. 32.1%), CLASI response (43.6% vs. 24.9%), and BICLA response (48.1% vs. 29.8%).

“For BICLA response, we see a fairly significant change ... with what appears to be a clinically significant delta (about 16 percentage points), and as far as the change in active joints, also very significant in my eyes,” he said.

Also of note, the time to BICLA response sustained to week 52 was improved with anifrolumab (hazard ratio, 1.93), and CLASI response differences emerged early, at about 12 weeks, he said.

The type 1 IFNGS was reduced by a median of 88% to 90% in the anifrolumab groups vs. with placebo, and modest changes in serologies were also noted.

Serious adverse events occurred in 13.9% and 10.8% of patients in the anifrolumab 300- and 150-mg arms, compared with 16.3% in the placebo arm. Herpes zoster was more common in the anifrolumab groups (5.6% for 300 mg and 5.4% for 150 mg vs. 1.6% for placebo).

“But other than that, no major standouts as far as the safety profile,” Dr. Furie said.

The findings, particularly after the medication rules were amended, suggest efficacy of anifrolumab for corticosteroid reductions, skin activity, BICLA, and joint scores, he said, noting that corticosteroid dose reductions are very important for patients, and that BICLA is “actually a very rigorous composite.”

Importantly, the findings also underscore the importance and impact of medication rules, and the critical role that endpoint selection plays in SLE trials.

“We’ve been seeing discordance lately between the SRI and BICLA ... so [there is] still a lot to learn,” he said. “And I think it’s important in evaluating the drug effect to look at the totality of the data.”

TULIP-2

BICLA response, the primary endpoint of TULIP-2, was achieved by 47.8% of 180 patients who received anifrolumab, compared with 31.5% of 182 who received placebo, said Dr. Morand, professor and head of the School of Clinical Sciences at Monash University, Melbourne.

“The effect size was 16.3 percentage points with an adjusted p value of 0.001. Therefore, the primary outcome of this trial was attained,” said Dr. Morand, who also is head of the Monash Health Rheumatology Unit. “Separation between the treatment arms occurred early and was maintained across the progression of the trial.”

Anifrolumab was also superior to placebo for key secondary endpoints, including OCS dose reduction to 7.5 mg/day or less (51.5% vs. 30.2%) and CLASI response (49.0% vs. 25.0%).

“Joint responses did not show a significant difference between the anifrolumab and placebo arms,” he said, adding that the annualized flare rate also did not differ significantly between the groups, but was numerically lower in anifrolumab-treated patients (0.43 vs. 0.64; rate ratio, 0.67; P = .081).

Numeric differences also favored anifrolumab for multiple secondary endpoints, including SRI responses, time to onset of BICLA-sustained response, and time to first flare, he noted.

Further, in patients with high baseline IFNGS, anifrolumab induced neutralization of IFNGS by week 12, with a median suppression of 88.0%, which persisted for the duration of the study; no such effect was seen in the placebo arm.

Serum anti–double stranded DNA also trended toward normalization with anifrolumab.

The safety profile of anifrolumab was similar to that seen in previous trials, including TULIP-1, with herpes zoster occurring more often in those receiving anifrolumab (7.2% vs. 1.1% in the placebo group), Dr. Morand said, noting that “all herpes zoster episodes were cutaneous, all responded to antiviral therapy, and none required [treatment] discontinuation.”

Serious adverse events, including pneumonia and SLE worsening, occurred less frequently in the anifrolumab arm (8.3% vs. 17.0%, respectively), as did adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation (2.8% and 7.1%). One death occurred in the anifrolumab group from community-acquired pneumonia, and few patients (0.6%) developed antidrug antibodies.

No new safety signals were identified, he said, noting that “the findings add to cumulative evidence identifying anifrolumab as a potential new treatment option for SLE.”

“In conclusion, TULIP-2 was a positive phase 3 trial in lupus, and there aren’t many times that that sentence has been spoken,” he said.

The TULIP-1 and -2 trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Furie And Dr. Morand both reported grant/research support and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, as well as speaker’s bureau participation for AstraZeneca.

SOURCES: Furie RA et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 1763; Morand EF et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract L17.

ATLANTA –

In TULIP-1, which compared intravenous anifrolumab at doses of 300 or 150 mg and placebo given every 4 weeks for 48 weeks, the primary endpoint of SLE Responder Index (SRI) in the 300 mg versus the placebo group was not met, but in post hoc analyses, numeric improvements at thresholds associated with clinical benefit were observed for several secondary outcomes, Richard A. Furie, MD, a professor of medicine at the Hofstra University/Northwell, Hempstead, N.Y., reported during a plenary session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The findings were published online Nov. 11 in Lancet Rheumatology.

TULIP-2 compared IV anifrolumab at a dose of 300 mg versus placebo every 4 weeks for 48 weeks and demonstrated the superiority of anifrolumab for multiple efficacy endpoints, including the primary study endpoint of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG)-based Composite Lupus Assessment (BICLA), Eric F. Morand, MD, PhD, reported during a late-breaking abstract session at the meeting.

The double-blind, phase 3 TULIP trials each enrolled seropositive SLE patients with moderate to severe active disease despite standard-of-care therapy (SOC). All patients met ACR criteria, had a SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI)-2K of 6 or greater, and BILAG index scoring showing one or more organ systems with grade A involvement or two or more with grade B. Both trials required stable SOC therapy throughout the study except for mandatory attempts at oral corticosteroid (OCS) tapering for patients who were receiving 10 mg/day or more of prednisone or its equivalent at study entry.

The trials followed a phase 2 trial, reported by Dr. Furie at the 2015 ACR meeting and published in Arthritis & Rheumatology in 2017, which showed “very robust” efficacy of anifrolumab in this setting.

“The burning question for the last 20 years has been, ‘Can type 1 interferon inhibitors actually reduce lupus clinical activity?’ ” Dr. Furie said. “The problem here [is that] you can inhibit interferon-alpha, but there are four other subtypes capable of binding to the interferon receptor.”

Anifrolumab, which was first studied in scleroderma, inhibits the interferon (IFN) receptor, thereby providing broader inhibition than strategies that specifically target interferon-alpha, he explained.

In the phase 2 trial, the primary composite endpoint of SRI response at day 169 and sustained reduction of OCS dose between days 85 and 169 was met by 51.5% of patients receiving 300 mg of anifrolumab versus 26.6% of those receiving placebo.

TULIP-1

The TULIP-1 trial, however, failed to show a significant difference in the primary endpoint of week 52 SRI, although initial analyses showed some numeric benefit with respect to BICLA, OCS dose reductions, and other organ-specific endpoints.

The percentage of SRI responders at week 52 in the double-blind trial was 36.2% in 180 patients who received 300 mg anifrolumab vs. 40.4% in 184 who received placebo (nominal P value = .41), and in a subgroup of patients who had high IFN gene signature (IFNGS) test results, the rates were 35.9% and 39.3% (nominal P value = 0.55), respectively.

Sustained OCS reduction to 7.5 mg/day or less occurred in 41% of anifrolumab and 32.1% of placebo group patients, and a 50% or greater reduction in Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Severity Index (CLASI) activity from baseline to week 12 occurred in 41.9% and 24.9%, respectively. The annualized flare rate to week 52 was 0.72 for anifrolumab and 0.60 for placebo.

BICLA response at week 52 was 37.1% with anifrolumab versus 27% with placebo, and a 50% or greater reduction in active joints from baseline to week 52 occurred in 47% versus 32.5% of patients in the groups, respectively.

The 150-mg dose, which was included to provide dose-response data, did not show efficacy in secondary outcomes.

“We see a delta of about 10 percentage points [for BICLA], and about a 15-percentage point change [in swollen and tender joint count] in favor of anifrolumab,” Dr. Furie said. “So why the big difference between phase 2 results and phase 3 results? Well, that led to a year-long interrogation of all the data ... [which revealed that] about 8% of patients were misclassified as nonresponders for [NSAID] use.”

The medication rules in the study automatically required any patient who used a restricted drug, including NSAIDs, to be classified as a nonresponder. That means a patient who took an NSAID for a headache at the beginning of the study, for example, would have been considered a nonresponder regardless of their outcome, he explained.

“This led to a review of all the restricted medication classification rules, and after unblinding, a meeting was convened with SLE experts and the sponsors to actually revise the medication rules just to make them clinically more appropriate. The key analyses were repeated post hoc,” he said.

The difference between the treatment and placebo groups in terms of the week 52 SRI didn’t change much in the post hoc analysis (46.9% vs. 43% of treatment and placebo patients, respectively, met the endpoint). Similarly, SRI rates in the IFNGS test–high subgroup were 48.2% and 41.8%, respectively.

However, more pronounced “shifts to the right,” indicating larger differences favoring anifrolumab over placebo, were seen for OCS dose reduction (48.8% vs. 32.1%), CLASI response (43.6% vs. 24.9%), and BICLA response (48.1% vs. 29.8%).

“For BICLA response, we see a fairly significant change ... with what appears to be a clinically significant delta (about 16 percentage points), and as far as the change in active joints, also very significant in my eyes,” he said.

Also of note, the time to BICLA response sustained to week 52 was improved with anifrolumab (hazard ratio, 1.93), and CLASI response differences emerged early, at about 12 weeks, he said.

The type 1 IFNGS was reduced by a median of 88% to 90% in the anifrolumab groups vs. with placebo, and modest changes in serologies were also noted.

Serious adverse events occurred in 13.9% and 10.8% of patients in the anifrolumab 300- and 150-mg arms, compared with 16.3% in the placebo arm. Herpes zoster was more common in the anifrolumab groups (5.6% for 300 mg and 5.4% for 150 mg vs. 1.6% for placebo).

“But other than that, no major standouts as far as the safety profile,” Dr. Furie said.

The findings, particularly after the medication rules were amended, suggest efficacy of anifrolumab for corticosteroid reductions, skin activity, BICLA, and joint scores, he said, noting that corticosteroid dose reductions are very important for patients, and that BICLA is “actually a very rigorous composite.”

Importantly, the findings also underscore the importance and impact of medication rules, and the critical role that endpoint selection plays in SLE trials.

“We’ve been seeing discordance lately between the SRI and BICLA ... so [there is] still a lot to learn,” he said. “And I think it’s important in evaluating the drug effect to look at the totality of the data.”

TULIP-2

BICLA response, the primary endpoint of TULIP-2, was achieved by 47.8% of 180 patients who received anifrolumab, compared with 31.5% of 182 who received placebo, said Dr. Morand, professor and head of the School of Clinical Sciences at Monash University, Melbourne.