User login

Reproductive safety of treatments for women with bipolar disorder

Since March 2020, my colleagues and I have conducted Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital. It has been an opportunity to review the basic tenets of care for reproductive age women before, during, and after pregnancy, and also to learn of extraordinary cases being managed both in the outpatient setting and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As I’ve noted in previous columns, we have seen a heightening of symptoms of anxiety and insomnia during the pandemic in women who visit our center, and at the centers of the more than 100 clinicians who join Virtual Rounds each week. These colleagues represent people in rural areas, urban environments, and underserved communities across America that have been severely affected by the pandemic. It is clear that the stress of the pandemic is undeniable for patients both with and without psychiatric or mental health issues. We have also seen clinical roughening in women who have been well for a long period of time. In particular, we have noticed that postpartum women are struggling with the stressors of the postpartum period, such as figuring out the logistics of support with respect to childcare, managing maternity leave, and adapting to shifting of anticipated support systems.

Hundreds of women with bipolar disorder come to see us each year about the reproductive safety of the medicines on which they are maintained. Those patients are typically well, and we collaborate with them and their doctors about the safest treatment recommendations. With that said, women with bipolar disorder are at particular risk for postpartum worsening of their mood. The management of their medications during pregnancy requires extremely careful attention because relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of postpartum worsening of underlying psychiatric illness.

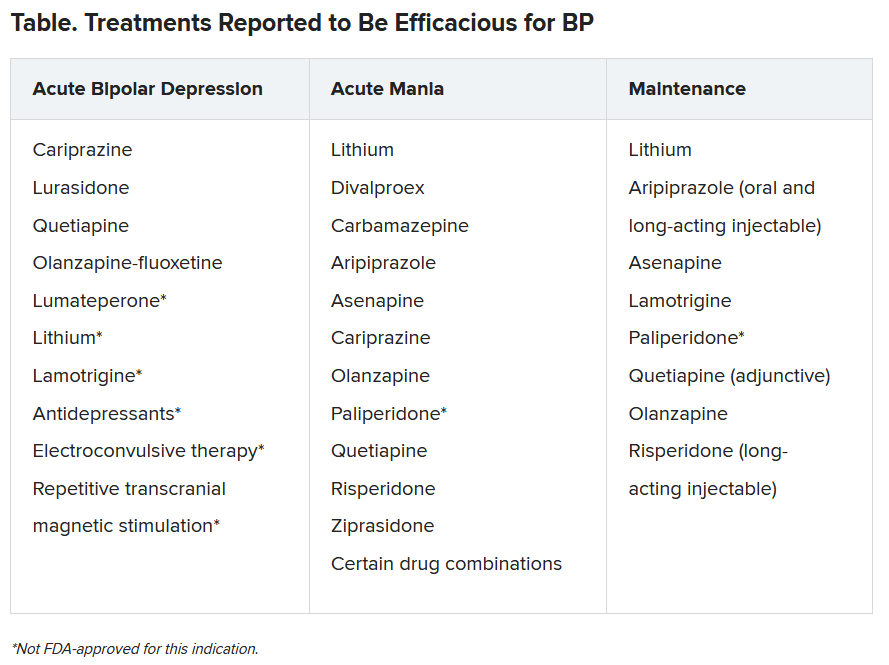

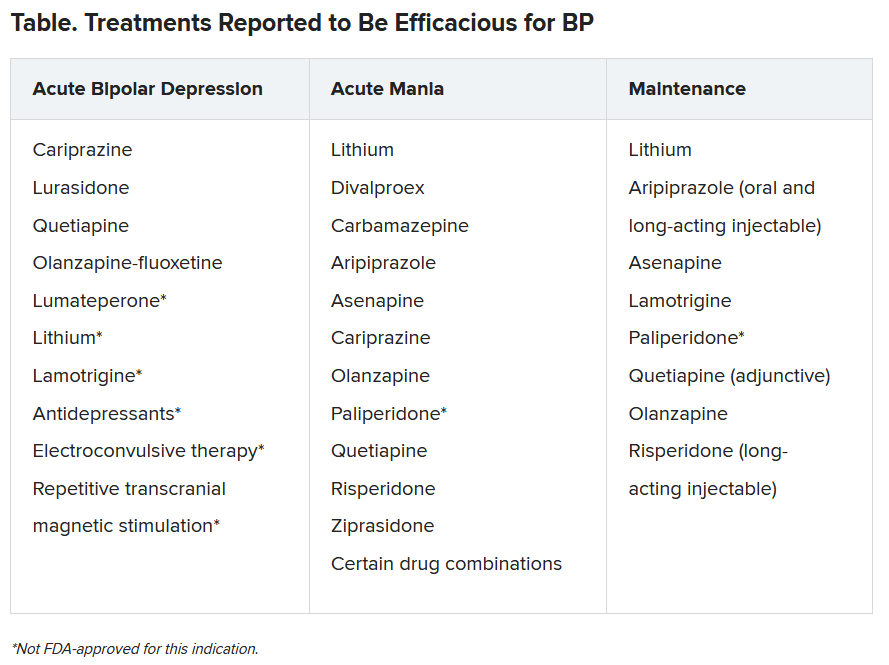

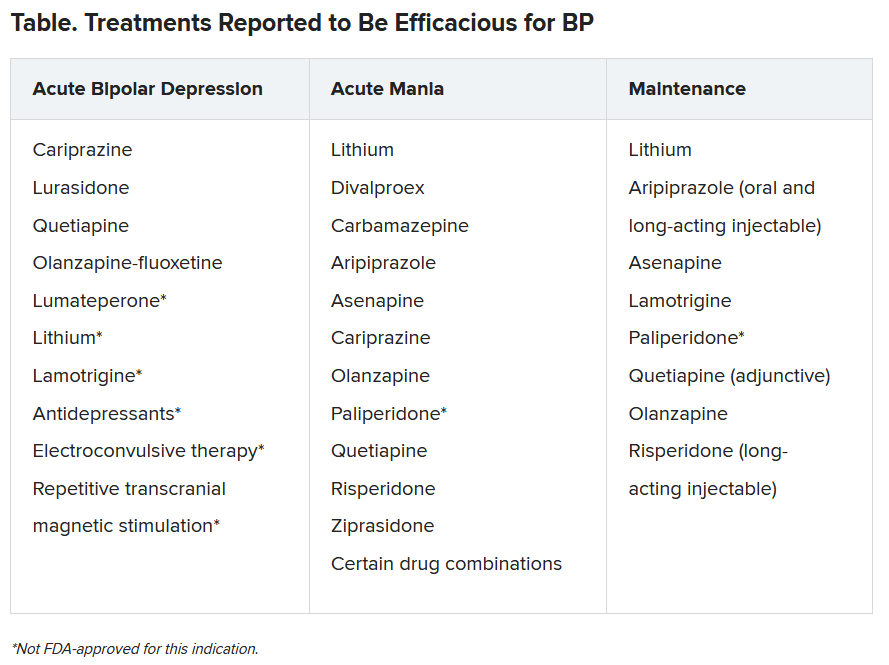

This is an opportunity to briefly review the reproductive safety of treatments for these women. We know through initiatives such as the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Psychiatric Medications that the most widely used medicines for bipolar women during pregnancy include lamotrigine, atypical antipsychotics, and lithium carbonate.

Lamotrigine

The last 15 years have generated the most consistent data on the reproductive safety of lamotrigine. One of the issues, however, with respect to lamotrigine is that its use requires very careful and slow titration and it is also more effective in patients who are well and in the maintenance phase of the illness versus those who are more acutely manic or who are suffering from frank bipolar depression.

Critically, the literature does not support the use of lamotrigine for patients with bipolar I or with more manic symptoms. That being said, it remains a mainstay of treatment for many patients with bipolar disorder, is easy to use across pregnancy, and has an attractive side-effect profile and a very strong reproductive safety profile, suggesting the absence of an increased risk for major malformations.

Atypical antipsychotics

We have less information but have a growing body of evidence about atypical antipsychotics. Both data from administrative databases as well a growing literature from pregnancy registries, such as the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics, fail to show a signal for teratogenicity with respect to use of the medicines as a class, and also with specific reference to some of the most widely used atypical antipsychotics, particularly quetiapine and aripiprazole. Our comfort level, compared with a decade ago, with using the second-generation antipsychotics is much greater. That’s a good thing considering the extent to which patients presenting on a combination of, for example, lamotrigine and atypical antipsychotics.

Lithium carbonate

Another mainstay of treatment for women with bipolar I disorder and prominent symptoms of mania is lithium carbonate. The data for efficacy of lithium carbonate used both acutely and for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder has been unequivocal. Concerns about the teratogenicity of lithium go back to the 1970s and indicate a small increased absolute and relative risk for cardiovascular malformations. More recently, a meta-analysis of lithium exposure during pregnancy and the postpartum period supports this older data, which suggests this increased risk, and examines other outcomes concerning to women with bipolar disorder who use lithium, such as preterm labor, low birth weight, miscarriage, and other adverse neonatal outcomes.

In 2021, with the backdrop of the pandemic, what we actually see is that, for our pregnant and postpartum patients with bipolar disorder, the imperative to keep them well, keep them out of the hospital, and keep them safe has often required careful coadministration of drugs like lamotrigine, lithium, and atypical antipsychotics (and even benzodiazepines). Keeping this population well during the perinatal period is so critical. We were all trained to use the least number of medications when possible across psychiatric illnesses. But the years, data, and clinical experience have shown that polypharmacy may be required to sustain euthymia in many patients with bipolar disorder. The reflex historically has been to stop medications during pregnancy. We take pause, particularly during the pandemic, before reverting back to the practice of 25 years ago of abruptly stopping medicines such as lithium or atypical antipsychotics in patients with bipolar disorder because we know that the risk for relapse is very high following a shift from the regimen that got the patient well.

The COVID-19 pandemic in many respects has highlighted a need to clinically thread the needle with respect to developing a regimen that minimizes risk of reproductive safety concerns but maximizes the likelihood that we can sustain the emotional well-being of these women across pregnancy and into the postpartum period.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Since March 2020, my colleagues and I have conducted Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital. It has been an opportunity to review the basic tenets of care for reproductive age women before, during, and after pregnancy, and also to learn of extraordinary cases being managed both in the outpatient setting and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As I’ve noted in previous columns, we have seen a heightening of symptoms of anxiety and insomnia during the pandemic in women who visit our center, and at the centers of the more than 100 clinicians who join Virtual Rounds each week. These colleagues represent people in rural areas, urban environments, and underserved communities across America that have been severely affected by the pandemic. It is clear that the stress of the pandemic is undeniable for patients both with and without psychiatric or mental health issues. We have also seen clinical roughening in women who have been well for a long period of time. In particular, we have noticed that postpartum women are struggling with the stressors of the postpartum period, such as figuring out the logistics of support with respect to childcare, managing maternity leave, and adapting to shifting of anticipated support systems.

Hundreds of women with bipolar disorder come to see us each year about the reproductive safety of the medicines on which they are maintained. Those patients are typically well, and we collaborate with them and their doctors about the safest treatment recommendations. With that said, women with bipolar disorder are at particular risk for postpartum worsening of their mood. The management of their medications during pregnancy requires extremely careful attention because relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of postpartum worsening of underlying psychiatric illness.

This is an opportunity to briefly review the reproductive safety of treatments for these women. We know through initiatives such as the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Psychiatric Medications that the most widely used medicines for bipolar women during pregnancy include lamotrigine, atypical antipsychotics, and lithium carbonate.

Lamotrigine

The last 15 years have generated the most consistent data on the reproductive safety of lamotrigine. One of the issues, however, with respect to lamotrigine is that its use requires very careful and slow titration and it is also more effective in patients who are well and in the maintenance phase of the illness versus those who are more acutely manic or who are suffering from frank bipolar depression.

Critically, the literature does not support the use of lamotrigine for patients with bipolar I or with more manic symptoms. That being said, it remains a mainstay of treatment for many patients with bipolar disorder, is easy to use across pregnancy, and has an attractive side-effect profile and a very strong reproductive safety profile, suggesting the absence of an increased risk for major malformations.

Atypical antipsychotics

We have less information but have a growing body of evidence about atypical antipsychotics. Both data from administrative databases as well a growing literature from pregnancy registries, such as the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics, fail to show a signal for teratogenicity with respect to use of the medicines as a class, and also with specific reference to some of the most widely used atypical antipsychotics, particularly quetiapine and aripiprazole. Our comfort level, compared with a decade ago, with using the second-generation antipsychotics is much greater. That’s a good thing considering the extent to which patients presenting on a combination of, for example, lamotrigine and atypical antipsychotics.

Lithium carbonate

Another mainstay of treatment for women with bipolar I disorder and prominent symptoms of mania is lithium carbonate. The data for efficacy of lithium carbonate used both acutely and for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder has been unequivocal. Concerns about the teratogenicity of lithium go back to the 1970s and indicate a small increased absolute and relative risk for cardiovascular malformations. More recently, a meta-analysis of lithium exposure during pregnancy and the postpartum period supports this older data, which suggests this increased risk, and examines other outcomes concerning to women with bipolar disorder who use lithium, such as preterm labor, low birth weight, miscarriage, and other adverse neonatal outcomes.

In 2021, with the backdrop of the pandemic, what we actually see is that, for our pregnant and postpartum patients with bipolar disorder, the imperative to keep them well, keep them out of the hospital, and keep them safe has often required careful coadministration of drugs like lamotrigine, lithium, and atypical antipsychotics (and even benzodiazepines). Keeping this population well during the perinatal period is so critical. We were all trained to use the least number of medications when possible across psychiatric illnesses. But the years, data, and clinical experience have shown that polypharmacy may be required to sustain euthymia in many patients with bipolar disorder. The reflex historically has been to stop medications during pregnancy. We take pause, particularly during the pandemic, before reverting back to the practice of 25 years ago of abruptly stopping medicines such as lithium or atypical antipsychotics in patients with bipolar disorder because we know that the risk for relapse is very high following a shift from the regimen that got the patient well.

The COVID-19 pandemic in many respects has highlighted a need to clinically thread the needle with respect to developing a regimen that minimizes risk of reproductive safety concerns but maximizes the likelihood that we can sustain the emotional well-being of these women across pregnancy and into the postpartum period.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Since March 2020, my colleagues and I have conducted Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital. It has been an opportunity to review the basic tenets of care for reproductive age women before, during, and after pregnancy, and also to learn of extraordinary cases being managed both in the outpatient setting and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As I’ve noted in previous columns, we have seen a heightening of symptoms of anxiety and insomnia during the pandemic in women who visit our center, and at the centers of the more than 100 clinicians who join Virtual Rounds each week. These colleagues represent people in rural areas, urban environments, and underserved communities across America that have been severely affected by the pandemic. It is clear that the stress of the pandemic is undeniable for patients both with and without psychiatric or mental health issues. We have also seen clinical roughening in women who have been well for a long period of time. In particular, we have noticed that postpartum women are struggling with the stressors of the postpartum period, such as figuring out the logistics of support with respect to childcare, managing maternity leave, and adapting to shifting of anticipated support systems.

Hundreds of women with bipolar disorder come to see us each year about the reproductive safety of the medicines on which they are maintained. Those patients are typically well, and we collaborate with them and their doctors about the safest treatment recommendations. With that said, women with bipolar disorder are at particular risk for postpartum worsening of their mood. The management of their medications during pregnancy requires extremely careful attention because relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy is the strongest predictor of postpartum worsening of underlying psychiatric illness.

This is an opportunity to briefly review the reproductive safety of treatments for these women. We know through initiatives such as the Massachusetts General Hospital National Pregnancy Registry for Psychiatric Medications that the most widely used medicines for bipolar women during pregnancy include lamotrigine, atypical antipsychotics, and lithium carbonate.

Lamotrigine

The last 15 years have generated the most consistent data on the reproductive safety of lamotrigine. One of the issues, however, with respect to lamotrigine is that its use requires very careful and slow titration and it is also more effective in patients who are well and in the maintenance phase of the illness versus those who are more acutely manic or who are suffering from frank bipolar depression.

Critically, the literature does not support the use of lamotrigine for patients with bipolar I or with more manic symptoms. That being said, it remains a mainstay of treatment for many patients with bipolar disorder, is easy to use across pregnancy, and has an attractive side-effect profile and a very strong reproductive safety profile, suggesting the absence of an increased risk for major malformations.

Atypical antipsychotics

We have less information but have a growing body of evidence about atypical antipsychotics. Both data from administrative databases as well a growing literature from pregnancy registries, such as the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics, fail to show a signal for teratogenicity with respect to use of the medicines as a class, and also with specific reference to some of the most widely used atypical antipsychotics, particularly quetiapine and aripiprazole. Our comfort level, compared with a decade ago, with using the second-generation antipsychotics is much greater. That’s a good thing considering the extent to which patients presenting on a combination of, for example, lamotrigine and atypical antipsychotics.

Lithium carbonate

Another mainstay of treatment for women with bipolar I disorder and prominent symptoms of mania is lithium carbonate. The data for efficacy of lithium carbonate used both acutely and for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder has been unequivocal. Concerns about the teratogenicity of lithium go back to the 1970s and indicate a small increased absolute and relative risk for cardiovascular malformations. More recently, a meta-analysis of lithium exposure during pregnancy and the postpartum period supports this older data, which suggests this increased risk, and examines other outcomes concerning to women with bipolar disorder who use lithium, such as preterm labor, low birth weight, miscarriage, and other adverse neonatal outcomes.

In 2021, with the backdrop of the pandemic, what we actually see is that, for our pregnant and postpartum patients with bipolar disorder, the imperative to keep them well, keep them out of the hospital, and keep them safe has often required careful coadministration of drugs like lamotrigine, lithium, and atypical antipsychotics (and even benzodiazepines). Keeping this population well during the perinatal period is so critical. We were all trained to use the least number of medications when possible across psychiatric illnesses. But the years, data, and clinical experience have shown that polypharmacy may be required to sustain euthymia in many patients with bipolar disorder. The reflex historically has been to stop medications during pregnancy. We take pause, particularly during the pandemic, before reverting back to the practice of 25 years ago of abruptly stopping medicines such as lithium or atypical antipsychotics in patients with bipolar disorder because we know that the risk for relapse is very high following a shift from the regimen that got the patient well.

The COVID-19 pandemic in many respects has highlighted a need to clinically thread the needle with respect to developing a regimen that minimizes risk of reproductive safety concerns but maximizes the likelihood that we can sustain the emotional well-being of these women across pregnancy and into the postpartum period.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Blood pressure meds tied to increased schizophrenia risk

ACE inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk for schizophrenia and may affect psychiatric symptoms, new research suggests.

Investigators found individuals who carry a genetic variant associated with lower levels of the ACE gene and protein have increased liability to schizophrenia, suggesting that drugs that lower ACE levels or activity may do the same.

“Our findings warrant further investigation into the role of ACE in schizophrenia and closer monitoring by clinicians of individuals, especially those with schizophrenia, who may be on medication that lower ACE activity, such as ACE inhibitors,” Sonia Shah, PhD, Institute for Biomedical Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, said in an interview.

The study was published online March 10, 2021, in JAMA Psychiatry.

Antihypertensives and mental illness

Hypertension is common in patients with psychiatric disorders and observational studies have reported associations between antihypertensive medication and these disorders, although the findings have been mixed.

Dr. Shah and colleagues estimated the potential of different antihypertensive drug classes on schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.

In a two-sample Mendelian randomization study, they evaluated ties between a single-nucleotide variant and drug-target gene expression derived from expression quantitative trait loci data in blood (sample 1) and the SNV disease association from published case-control, genomewide association studies (sample 2).

The analyses included 40,675 patients with schizophrenia and 64,643 controls; 20,352 with bipolar disorder and 31,358 controls; and 135,458 with major depressive disorder and 344,901 controls.

The major finding was that a one standard deviation–lower expression of the ACE gene in blood was associated with lower systolic blood pressure of 4.0 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, 2.7-5.3), but also an increased risk of schizophrenia (odds ratio, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.28-2.38).

Could ACE inhibitors worsen symptoms or trigger episodes?

In their article, the researchers noted that, in most patients, onset of schizophrenia occurs in late adolescence or early adult life, ruling out ACE inhibitor treatment as a potential causal factor for most cases.

“However, if lower ACE levels play a causal role for schizophrenia risk, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that further lowering of ACE activity in existing patients could worsen symptoms or trigger a new episode,” they wrote.

Dr. Shah emphasized that evidence from genetic analyses alone is “not sufficient to justify changes in prescription guidelines.”

“Patients should not stop taking these medications if they are effective at controlling their blood pressure and they don’t suffer any adverse effects. But it would be reasonable to encourage greater pharmacovigilance,” she said in an interview.

“One way in which we are hoping to follow up these findings,” said Dr. Shah, “is to access electronic health record data for millions of individuals to investigate if there is evidence of increased rates of psychotic episodes in individuals who use ACE inhibitors, compared to other classes of blood pressure–lowering medication.”

Caution warranted

Reached for comment, Timothy Sullivan, MD, chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Staten Island University Hospital in New York, noted that this is an “extremely complicated” study and urged caution in interpreting the results.

“Since most people develop schizophrenia earlier in life, before they usually develop problems with blood pressure, it’s not so much that these drugs might cause schizophrenia,” Dr. Sullivan said.

“But because of their effects on this particular gene, there’s a possibility that they might worsen symptoms or in somebody with borderline risk might cause them to develop symptoms later in life. This may apply to a relatively small number of people who develop symptoms of schizophrenia in their 40s and beyond,” he added.

That’s where “pharmacovigilance” comes into play, Dr. Sullivan said. “In other words, that they otherwise wouldn’t experience?”

Support for the study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and U.S. National Institute for Mental Health. Dr. Shah and Dr. Sullivan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ACE inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk for schizophrenia and may affect psychiatric symptoms, new research suggests.

Investigators found individuals who carry a genetic variant associated with lower levels of the ACE gene and protein have increased liability to schizophrenia, suggesting that drugs that lower ACE levels or activity may do the same.

“Our findings warrant further investigation into the role of ACE in schizophrenia and closer monitoring by clinicians of individuals, especially those with schizophrenia, who may be on medication that lower ACE activity, such as ACE inhibitors,” Sonia Shah, PhD, Institute for Biomedical Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, said in an interview.

The study was published online March 10, 2021, in JAMA Psychiatry.

Antihypertensives and mental illness

Hypertension is common in patients with psychiatric disorders and observational studies have reported associations between antihypertensive medication and these disorders, although the findings have been mixed.

Dr. Shah and colleagues estimated the potential of different antihypertensive drug classes on schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.

In a two-sample Mendelian randomization study, they evaluated ties between a single-nucleotide variant and drug-target gene expression derived from expression quantitative trait loci data in blood (sample 1) and the SNV disease association from published case-control, genomewide association studies (sample 2).

The analyses included 40,675 patients with schizophrenia and 64,643 controls; 20,352 with bipolar disorder and 31,358 controls; and 135,458 with major depressive disorder and 344,901 controls.

The major finding was that a one standard deviation–lower expression of the ACE gene in blood was associated with lower systolic blood pressure of 4.0 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, 2.7-5.3), but also an increased risk of schizophrenia (odds ratio, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.28-2.38).

Could ACE inhibitors worsen symptoms or trigger episodes?

In their article, the researchers noted that, in most patients, onset of schizophrenia occurs in late adolescence or early adult life, ruling out ACE inhibitor treatment as a potential causal factor for most cases.

“However, if lower ACE levels play a causal role for schizophrenia risk, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that further lowering of ACE activity in existing patients could worsen symptoms or trigger a new episode,” they wrote.

Dr. Shah emphasized that evidence from genetic analyses alone is “not sufficient to justify changes in prescription guidelines.”

“Patients should not stop taking these medications if they are effective at controlling their blood pressure and they don’t suffer any adverse effects. But it would be reasonable to encourage greater pharmacovigilance,” she said in an interview.

“One way in which we are hoping to follow up these findings,” said Dr. Shah, “is to access electronic health record data for millions of individuals to investigate if there is evidence of increased rates of psychotic episodes in individuals who use ACE inhibitors, compared to other classes of blood pressure–lowering medication.”

Caution warranted

Reached for comment, Timothy Sullivan, MD, chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Staten Island University Hospital in New York, noted that this is an “extremely complicated” study and urged caution in interpreting the results.

“Since most people develop schizophrenia earlier in life, before they usually develop problems with blood pressure, it’s not so much that these drugs might cause schizophrenia,” Dr. Sullivan said.

“But because of their effects on this particular gene, there’s a possibility that they might worsen symptoms or in somebody with borderline risk might cause them to develop symptoms later in life. This may apply to a relatively small number of people who develop symptoms of schizophrenia in their 40s and beyond,” he added.

That’s where “pharmacovigilance” comes into play, Dr. Sullivan said. “In other words, that they otherwise wouldn’t experience?”

Support for the study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and U.S. National Institute for Mental Health. Dr. Shah and Dr. Sullivan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ACE inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk for schizophrenia and may affect psychiatric symptoms, new research suggests.

Investigators found individuals who carry a genetic variant associated with lower levels of the ACE gene and protein have increased liability to schizophrenia, suggesting that drugs that lower ACE levels or activity may do the same.

“Our findings warrant further investigation into the role of ACE in schizophrenia and closer monitoring by clinicians of individuals, especially those with schizophrenia, who may be on medication that lower ACE activity, such as ACE inhibitors,” Sonia Shah, PhD, Institute for Biomedical Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, said in an interview.

The study was published online March 10, 2021, in JAMA Psychiatry.

Antihypertensives and mental illness

Hypertension is common in patients with psychiatric disorders and observational studies have reported associations between antihypertensive medication and these disorders, although the findings have been mixed.

Dr. Shah and colleagues estimated the potential of different antihypertensive drug classes on schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.

In a two-sample Mendelian randomization study, they evaluated ties between a single-nucleotide variant and drug-target gene expression derived from expression quantitative trait loci data in blood (sample 1) and the SNV disease association from published case-control, genomewide association studies (sample 2).

The analyses included 40,675 patients with schizophrenia and 64,643 controls; 20,352 with bipolar disorder and 31,358 controls; and 135,458 with major depressive disorder and 344,901 controls.

The major finding was that a one standard deviation–lower expression of the ACE gene in blood was associated with lower systolic blood pressure of 4.0 mm Hg (95% confidence interval, 2.7-5.3), but also an increased risk of schizophrenia (odds ratio, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.28-2.38).

Could ACE inhibitors worsen symptoms or trigger episodes?

In their article, the researchers noted that, in most patients, onset of schizophrenia occurs in late adolescence or early adult life, ruling out ACE inhibitor treatment as a potential causal factor for most cases.

“However, if lower ACE levels play a causal role for schizophrenia risk, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that further lowering of ACE activity in existing patients could worsen symptoms or trigger a new episode,” they wrote.

Dr. Shah emphasized that evidence from genetic analyses alone is “not sufficient to justify changes in prescription guidelines.”

“Patients should not stop taking these medications if they are effective at controlling their blood pressure and they don’t suffer any adverse effects. But it would be reasonable to encourage greater pharmacovigilance,” she said in an interview.

“One way in which we are hoping to follow up these findings,” said Dr. Shah, “is to access electronic health record data for millions of individuals to investigate if there is evidence of increased rates of psychotic episodes in individuals who use ACE inhibitors, compared to other classes of blood pressure–lowering medication.”

Caution warranted

Reached for comment, Timothy Sullivan, MD, chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Staten Island University Hospital in New York, noted that this is an “extremely complicated” study and urged caution in interpreting the results.

“Since most people develop schizophrenia earlier in life, before they usually develop problems with blood pressure, it’s not so much that these drugs might cause schizophrenia,” Dr. Sullivan said.

“But because of their effects on this particular gene, there’s a possibility that they might worsen symptoms or in somebody with borderline risk might cause them to develop symptoms later in life. This may apply to a relatively small number of people who develop symptoms of schizophrenia in their 40s and beyond,” he added.

That’s where “pharmacovigilance” comes into play, Dr. Sullivan said. “In other words, that they otherwise wouldn’t experience?”

Support for the study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and U.S. National Institute for Mental Health. Dr. Shah and Dr. Sullivan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Inflammatory immune findings likely in acute schizophrenia, MDD, bipolar

Researchers have come a long way in understanding the link between acute inflammation and treatment-resistant depression, but more work needs to be done, according to Mark Hyman Rapaport, MD.

“Inflammation has been a hot topic in the past decade, both because of its impact in medical disorders and in psychiatric disorders,” Dr. Rapaport, CEO of the Huntsman Mental Health Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, said during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “We run into difficulty with chronic inflammation, which we see with rheumatic disorders, and when we think of metabolic syndrome and obesity.”

The immune system helps to control energy regulation and neuroendocrine function in acute inflammation and chronic inflammatory diseases. “We see a variety of effects on the central nervous system or liver function or on homeostasis of the body,” said Dr. Rapaport, who also chairs the department of psychiatry at the University of Utah, also in Salt Lake City. “These are all normal and necessary to channel energy to the immune system in order to fight what’s necessary in acute inflammatory response.”

A chronic state of inflammation can result in prolonged allocation of fuels to the immune system, tissue inflammation, and a chronically aberrant immune reaction, he continued. This can cause depressive symptoms/fatigue, anorexia, malnutrition, muscle wasting, cachectic obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, increased adipose tissue in the proximity of inflammatory lesion, alterations of steroid hormone axes, elevated sympathetic tone, hypertension, decreased parasympathetic tone, inflammation-related anemia, and osteopenia. “So, chronic inflammation has a lot of long-term sequelae that are detrimental,” he said.

Both physical stress and psychological stress also cause an inflammatory state. After looking at the medical literature, Dr. Rapaport and colleagues began to wonder whether inflammation and immune activation associated with psychiatric disorders are attributable to the stress of acute illness. To find out, they performed a meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients and evaluated comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. A total of three meta-analyses were performed: one of acute/inpatient studies, one on the impact of acute treatment, and one of outpatient studies. The researchers hypothesized that inflammatory and immune findings in psychiatric illnesses were tied to two distinct etiologies: the acute stress of illness and intrinsic immune dysfunction.

The meta-analyses included 68 studies: 40 involving patients with schizophrenia, 18 involving those with major depressive disorder (MDD) and 10 involving those with bipolar disorder. The researchers found that levels of four cytokines were significantly increased in acutely ill patients with schizophrenia, bipolar mania, and MDD, compared with controls: interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha), soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R), and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA). “There has not been a consistent blood panel used across studies, be it within a disorder itself like depression, or across disorders,” Dr. Rapaport noted. “This is a challenge that we face in looking at these data.”

Following treatment of acute illness, IL-6 levels significantly decreased in schizophrenia and MDD, but no significant changes in TNF-alpha levels were observed in patients with schizophrenia or MDD. In addition, sIL-2R levels increase in schizophrenia but remained unchanged in bipolar and MDD, while IL-1RA levels in bipolar mania decreased but remained unchanged in MDD. Meanwhile, assessment of the study’s 24 outpatient studies revealed that levels of IL-6 were significantly increased in outpatients with schizophrenia, euthymic bipolar disorder, and MDD, compared with controls (P < .01 for each). In addition, levels of IL-1 beta and sIL-2R were significantly increased in outpatients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

According to Dr. Rapaport, these meta-analyses suggest that there are likely inflammatory immune findings present in acutely ill patients with MDD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

“Some of this activation decreases with effective acute treatment of the disorder,” he said. “The data suggest that immune changes are present in a subset of patients with all three disorders.”

“We also need to understand the regulatory role that microglia and astroglia play within the brain,” he said. “We need to identify changes in brain circuitry and function associated with inflammation and other immune changes. We also need to carefully scrutinize publications, understand the assumptions behind the statistics, and carry out more research beyond the protein level.”

He concluded his presentation by calling for research to help clinicians differentiate acute from chronic inflammation. “The study of both is important,” he said. “We need to understand the pathophysiology of immune changes in psychiatric disorders. We need to study both the triggers and pathways to resolution.”

Dr. Rapaport disclosed that he has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Researchers have come a long way in understanding the link between acute inflammation and treatment-resistant depression, but more work needs to be done, according to Mark Hyman Rapaport, MD.

“Inflammation has been a hot topic in the past decade, both because of its impact in medical disorders and in psychiatric disorders,” Dr. Rapaport, CEO of the Huntsman Mental Health Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, said during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “We run into difficulty with chronic inflammation, which we see with rheumatic disorders, and when we think of metabolic syndrome and obesity.”

The immune system helps to control energy regulation and neuroendocrine function in acute inflammation and chronic inflammatory diseases. “We see a variety of effects on the central nervous system or liver function or on homeostasis of the body,” said Dr. Rapaport, who also chairs the department of psychiatry at the University of Utah, also in Salt Lake City. “These are all normal and necessary to channel energy to the immune system in order to fight what’s necessary in acute inflammatory response.”

A chronic state of inflammation can result in prolonged allocation of fuels to the immune system, tissue inflammation, and a chronically aberrant immune reaction, he continued. This can cause depressive symptoms/fatigue, anorexia, malnutrition, muscle wasting, cachectic obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, increased adipose tissue in the proximity of inflammatory lesion, alterations of steroid hormone axes, elevated sympathetic tone, hypertension, decreased parasympathetic tone, inflammation-related anemia, and osteopenia. “So, chronic inflammation has a lot of long-term sequelae that are detrimental,” he said.

Both physical stress and psychological stress also cause an inflammatory state. After looking at the medical literature, Dr. Rapaport and colleagues began to wonder whether inflammation and immune activation associated with psychiatric disorders are attributable to the stress of acute illness. To find out, they performed a meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients and evaluated comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. A total of three meta-analyses were performed: one of acute/inpatient studies, one on the impact of acute treatment, and one of outpatient studies. The researchers hypothesized that inflammatory and immune findings in psychiatric illnesses were tied to two distinct etiologies: the acute stress of illness and intrinsic immune dysfunction.

The meta-analyses included 68 studies: 40 involving patients with schizophrenia, 18 involving those with major depressive disorder (MDD) and 10 involving those with bipolar disorder. The researchers found that levels of four cytokines were significantly increased in acutely ill patients with schizophrenia, bipolar mania, and MDD, compared with controls: interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha), soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R), and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA). “There has not been a consistent blood panel used across studies, be it within a disorder itself like depression, or across disorders,” Dr. Rapaport noted. “This is a challenge that we face in looking at these data.”

Following treatment of acute illness, IL-6 levels significantly decreased in schizophrenia and MDD, but no significant changes in TNF-alpha levels were observed in patients with schizophrenia or MDD. In addition, sIL-2R levels increase in schizophrenia but remained unchanged in bipolar and MDD, while IL-1RA levels in bipolar mania decreased but remained unchanged in MDD. Meanwhile, assessment of the study’s 24 outpatient studies revealed that levels of IL-6 were significantly increased in outpatients with schizophrenia, euthymic bipolar disorder, and MDD, compared with controls (P < .01 for each). In addition, levels of IL-1 beta and sIL-2R were significantly increased in outpatients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

According to Dr. Rapaport, these meta-analyses suggest that there are likely inflammatory immune findings present in acutely ill patients with MDD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

“Some of this activation decreases with effective acute treatment of the disorder,” he said. “The data suggest that immune changes are present in a subset of patients with all three disorders.”

“We also need to understand the regulatory role that microglia and astroglia play within the brain,” he said. “We need to identify changes in brain circuitry and function associated with inflammation and other immune changes. We also need to carefully scrutinize publications, understand the assumptions behind the statistics, and carry out more research beyond the protein level.”

He concluded his presentation by calling for research to help clinicians differentiate acute from chronic inflammation. “The study of both is important,” he said. “We need to understand the pathophysiology of immune changes in psychiatric disorders. We need to study both the triggers and pathways to resolution.”

Dr. Rapaport disclosed that he has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Researchers have come a long way in understanding the link between acute inflammation and treatment-resistant depression, but more work needs to be done, according to Mark Hyman Rapaport, MD.

“Inflammation has been a hot topic in the past decade, both because of its impact in medical disorders and in psychiatric disorders,” Dr. Rapaport, CEO of the Huntsman Mental Health Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, said during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “We run into difficulty with chronic inflammation, which we see with rheumatic disorders, and when we think of metabolic syndrome and obesity.”

The immune system helps to control energy regulation and neuroendocrine function in acute inflammation and chronic inflammatory diseases. “We see a variety of effects on the central nervous system or liver function or on homeostasis of the body,” said Dr. Rapaport, who also chairs the department of psychiatry at the University of Utah, also in Salt Lake City. “These are all normal and necessary to channel energy to the immune system in order to fight what’s necessary in acute inflammatory response.”

A chronic state of inflammation can result in prolonged allocation of fuels to the immune system, tissue inflammation, and a chronically aberrant immune reaction, he continued. This can cause depressive symptoms/fatigue, anorexia, malnutrition, muscle wasting, cachectic obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, increased adipose tissue in the proximity of inflammatory lesion, alterations of steroid hormone axes, elevated sympathetic tone, hypertension, decreased parasympathetic tone, inflammation-related anemia, and osteopenia. “So, chronic inflammation has a lot of long-term sequelae that are detrimental,” he said.

Both physical stress and psychological stress also cause an inflammatory state. After looking at the medical literature, Dr. Rapaport and colleagues began to wonder whether inflammation and immune activation associated with psychiatric disorders are attributable to the stress of acute illness. To find out, they performed a meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients and evaluated comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. A total of three meta-analyses were performed: one of acute/inpatient studies, one on the impact of acute treatment, and one of outpatient studies. The researchers hypothesized that inflammatory and immune findings in psychiatric illnesses were tied to two distinct etiologies: the acute stress of illness and intrinsic immune dysfunction.

The meta-analyses included 68 studies: 40 involving patients with schizophrenia, 18 involving those with major depressive disorder (MDD) and 10 involving those with bipolar disorder. The researchers found that levels of four cytokines were significantly increased in acutely ill patients with schizophrenia, bipolar mania, and MDD, compared with controls: interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha), soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R), and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA). “There has not been a consistent blood panel used across studies, be it within a disorder itself like depression, or across disorders,” Dr. Rapaport noted. “This is a challenge that we face in looking at these data.”

Following treatment of acute illness, IL-6 levels significantly decreased in schizophrenia and MDD, but no significant changes in TNF-alpha levels were observed in patients with schizophrenia or MDD. In addition, sIL-2R levels increase in schizophrenia but remained unchanged in bipolar and MDD, while IL-1RA levels in bipolar mania decreased but remained unchanged in MDD. Meanwhile, assessment of the study’s 24 outpatient studies revealed that levels of IL-6 were significantly increased in outpatients with schizophrenia, euthymic bipolar disorder, and MDD, compared with controls (P < .01 for each). In addition, levels of IL-1 beta and sIL-2R were significantly increased in outpatients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

According to Dr. Rapaport, these meta-analyses suggest that there are likely inflammatory immune findings present in acutely ill patients with MDD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

“Some of this activation decreases with effective acute treatment of the disorder,” he said. “The data suggest that immune changes are present in a subset of patients with all three disorders.”

“We also need to understand the regulatory role that microglia and astroglia play within the brain,” he said. “We need to identify changes in brain circuitry and function associated with inflammation and other immune changes. We also need to carefully scrutinize publications, understand the assumptions behind the statistics, and carry out more research beyond the protein level.”

He concluded his presentation by calling for research to help clinicians differentiate acute from chronic inflammation. “The study of both is important,” he said. “We need to understand the pathophysiology of immune changes in psychiatric disorders. We need to study both the triggers and pathways to resolution.”

Dr. Rapaport disclosed that he has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

FROM NPA 2021

Cannabis tied to self-harm, death in youth with mood disorders

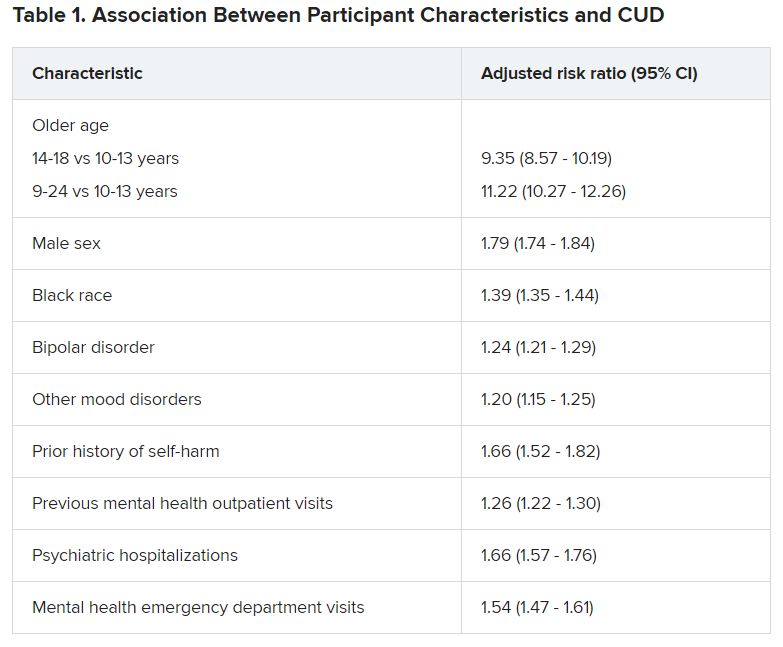

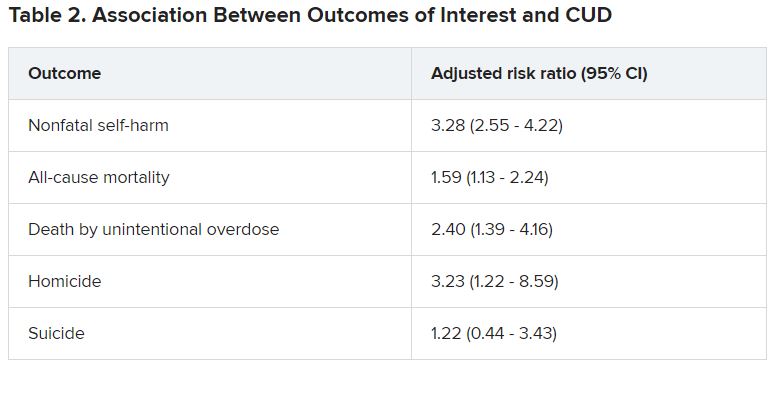

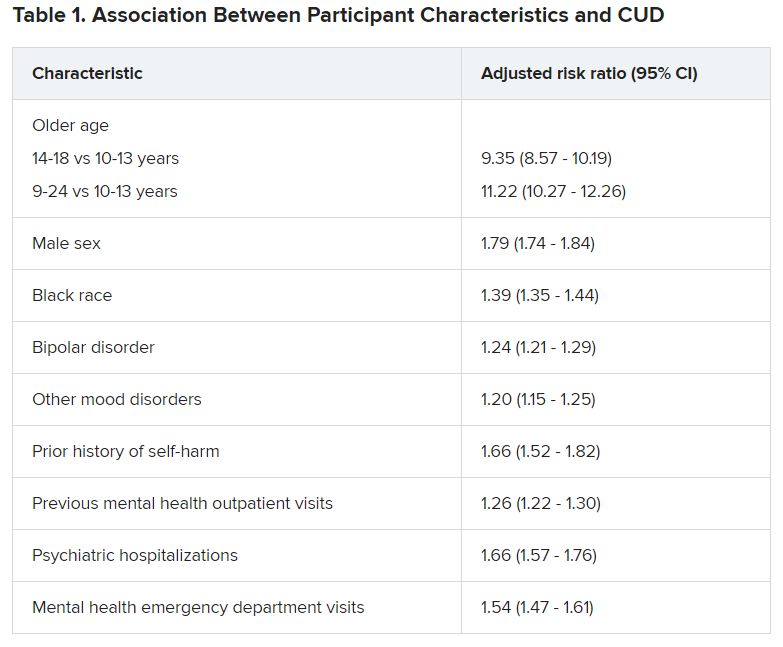

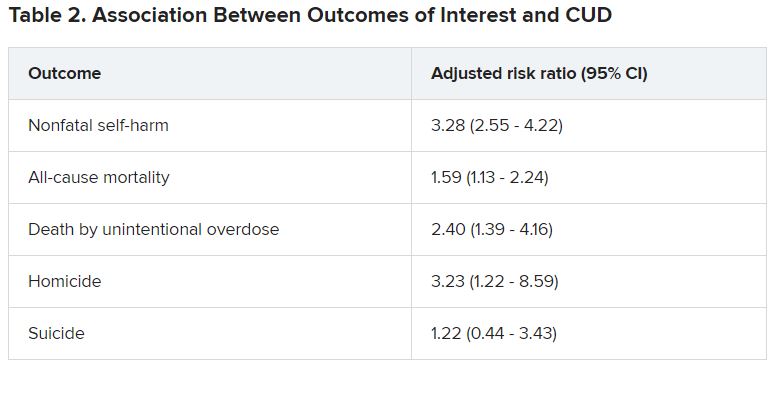

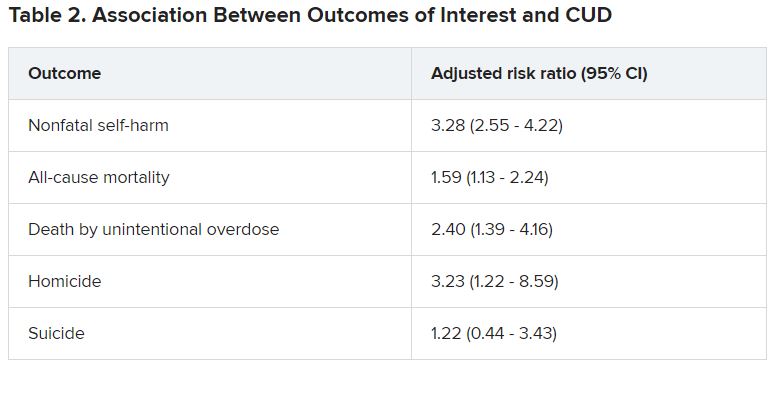

Adolescents and young adults with mood disorders and cannabis use disorder (CUD) are at significantly increased risk for self-harm, all-cause mortality, homicide, and death by unintentional overdose, new research suggests.

Investigators found the risk for self-harm was three times higher, all-cause mortality was 59% higher, unintentional overdose was 2.5 times higher, and homicide was more than three times higher in those with versus without CUD.

“The take-home message of these findings is that we need to be aware of the perception that cannabis use is harmless, when it’s actually not,” lead author Cynthia Fontanella, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in an interview.

“We need to educate parents and clinicians that there are risks associated with cannabis, including increased risk for self-harm and death, and we need to effectively treat both cannabis use disorder and mood disorders,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 19, 2021, in JAMA Pediatrics.

Little research in youth

“There has been very little research conducted on CUD in the adolescent population, and most studies have been conducted with adults,” Dr. Fontanella said.

Research on adults has shown that, even in people without mood disorders, cannabis use is associated with the early onset of mood disorders, psychosis, and anxiety disorders and has also been linked with suicidal behavior and increased risk for motor vehicle accidents, Dr. Fontanella said.

“We were motivated to conduct this study because we treat kids with depression and bipolar disorder and we noticed a high prevalence of CUD in this population, so we were curious about what its negative effects might be,” Dr. Fontanella recounted.

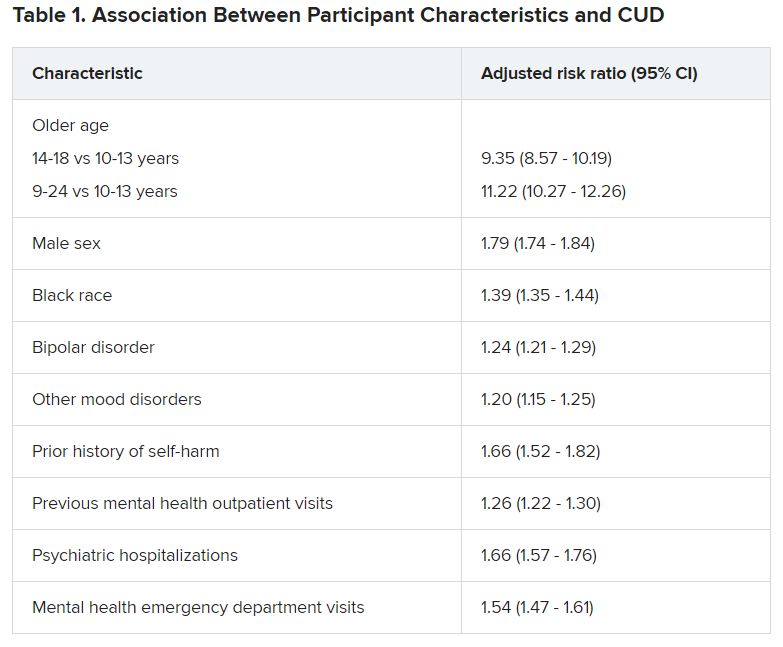

The researchers analyzed 7-year data drawn from Ohio Medicaid claims and linked to data from death certificates in 204,780 youths between the ages of 10 and 24 years (mean age was 17.2 years at the time of mood disorder diagnosis). Most were female, non-Hispanic White, enrolled in Medicaid because of poverty, and living in a metropolitan area (65.0%, 66.9%, 87.6%, and 77.1%, respectively).

Participants were followed up to 1 year from diagnosis until the end of enrollment, a self-harm event, or death.

Researchers included demographic, clinical, and treatment factors as covariates.

Close to three-quarters (72.7%) of the cohort had a depressive disorder, followed by unspecified/persistent mood disorder and bipolar disorder (14.9% and 12.4%, respectively). Comorbidities included ADHD (12.4%), anxiety disorder (12.3%), and other mental disorders (13.1%).

One -tenth of the cohort (10.3%) were diagnosed with CUD.

CUD treatment referrals

“Although CUD was associated with suicide in the unadjusted model, it was not significantly associated in adjusted models,” the authors reported.

Dr. Fontanella noted that the risk for these adverse outcomes is greater among those who engage in heavy, frequent use or who use cannabis that has higher-potency tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content.

Reasons why CUD might be associated with these adverse outcomes are that it can increase impulsivity, poor judgment, and clouded thinking, which may in turn increase the risk for self-harm behaviors, she said.

She recommended that clinicians refer youth with CUD for “effective treatments,” including family-based models and individual approaches, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational enhancement therapy.

Open dialogue

In a comment, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, adjunct clinical professor, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, noted that psychosis can occur in patients with CUD and mood disorders – especially bipolar disorder – but was not included as a study outcome. “I would have liked to see more data about that,” he said.

However, “The trend is that cannabis use is starting at younger and younger ages, which has all kinds of ramifications in terms of cerebral development.”

Christopher Hammond, MD, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said: “Three major strengths of the study are the size of the sample, its longitudinal analysis, and that the authors controlled for a number of potential confounding variables.”

In light of the findings, Dr. Hammond recommended clinicians and other health professionals who work with young people “should screen for cannabis-related problems in youth with mood disorders.”

Dr. Hammond, who is the director of the Co-occurring Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults Clinical and Research Program, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, and was not involved with the study, recommended counseling youth with mood disorders and their parents and families “regarding the potential adverse health effects related to cannabis use.”

He also recommended “open dialogue with youth with and without mental health conditions about misleading reports in the national media and advertising about cannabis’ health benefits.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Fontanella reported receiving grants from the National Institute of Mental Health during the conduct of the study. Dr. Raby reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Hammond reported receiving research grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, the National Network of Depression Centers, and the Armstrong Institute at Johns Hopkins Bayview and serves as a scientific adviser for the National Courts and Science Institute and as a subject matter expert for SAMHSA related to co-occurring substance use disorders and severe emotional disturbance in youth.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescents and young adults with mood disorders and cannabis use disorder (CUD) are at significantly increased risk for self-harm, all-cause mortality, homicide, and death by unintentional overdose, new research suggests.

Investigators found the risk for self-harm was three times higher, all-cause mortality was 59% higher, unintentional overdose was 2.5 times higher, and homicide was more than three times higher in those with versus without CUD.

“The take-home message of these findings is that we need to be aware of the perception that cannabis use is harmless, when it’s actually not,” lead author Cynthia Fontanella, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in an interview.

“We need to educate parents and clinicians that there are risks associated with cannabis, including increased risk for self-harm and death, and we need to effectively treat both cannabis use disorder and mood disorders,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 19, 2021, in JAMA Pediatrics.

Little research in youth

“There has been very little research conducted on CUD in the adolescent population, and most studies have been conducted with adults,” Dr. Fontanella said.

Research on adults has shown that, even in people without mood disorders, cannabis use is associated with the early onset of mood disorders, psychosis, and anxiety disorders and has also been linked with suicidal behavior and increased risk for motor vehicle accidents, Dr. Fontanella said.

“We were motivated to conduct this study because we treat kids with depression and bipolar disorder and we noticed a high prevalence of CUD in this population, so we were curious about what its negative effects might be,” Dr. Fontanella recounted.

The researchers analyzed 7-year data drawn from Ohio Medicaid claims and linked to data from death certificates in 204,780 youths between the ages of 10 and 24 years (mean age was 17.2 years at the time of mood disorder diagnosis). Most were female, non-Hispanic White, enrolled in Medicaid because of poverty, and living in a metropolitan area (65.0%, 66.9%, 87.6%, and 77.1%, respectively).

Participants were followed up to 1 year from diagnosis until the end of enrollment, a self-harm event, or death.

Researchers included demographic, clinical, and treatment factors as covariates.

Close to three-quarters (72.7%) of the cohort had a depressive disorder, followed by unspecified/persistent mood disorder and bipolar disorder (14.9% and 12.4%, respectively). Comorbidities included ADHD (12.4%), anxiety disorder (12.3%), and other mental disorders (13.1%).

One -tenth of the cohort (10.3%) were diagnosed with CUD.

CUD treatment referrals

“Although CUD was associated with suicide in the unadjusted model, it was not significantly associated in adjusted models,” the authors reported.

Dr. Fontanella noted that the risk for these adverse outcomes is greater among those who engage in heavy, frequent use or who use cannabis that has higher-potency tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content.

Reasons why CUD might be associated with these adverse outcomes are that it can increase impulsivity, poor judgment, and clouded thinking, which may in turn increase the risk for self-harm behaviors, she said.

She recommended that clinicians refer youth with CUD for “effective treatments,” including family-based models and individual approaches, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational enhancement therapy.

Open dialogue

In a comment, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, adjunct clinical professor, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, noted that psychosis can occur in patients with CUD and mood disorders – especially bipolar disorder – but was not included as a study outcome. “I would have liked to see more data about that,” he said.

However, “The trend is that cannabis use is starting at younger and younger ages, which has all kinds of ramifications in terms of cerebral development.”

Christopher Hammond, MD, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said: “Three major strengths of the study are the size of the sample, its longitudinal analysis, and that the authors controlled for a number of potential confounding variables.”

In light of the findings, Dr. Hammond recommended clinicians and other health professionals who work with young people “should screen for cannabis-related problems in youth with mood disorders.”

Dr. Hammond, who is the director of the Co-occurring Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults Clinical and Research Program, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, and was not involved with the study, recommended counseling youth with mood disorders and their parents and families “regarding the potential adverse health effects related to cannabis use.”

He also recommended “open dialogue with youth with and without mental health conditions about misleading reports in the national media and advertising about cannabis’ health benefits.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Fontanella reported receiving grants from the National Institute of Mental Health during the conduct of the study. Dr. Raby reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Hammond reported receiving research grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, the National Network of Depression Centers, and the Armstrong Institute at Johns Hopkins Bayview and serves as a scientific adviser for the National Courts and Science Institute and as a subject matter expert for SAMHSA related to co-occurring substance use disorders and severe emotional disturbance in youth.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescents and young adults with mood disorders and cannabis use disorder (CUD) are at significantly increased risk for self-harm, all-cause mortality, homicide, and death by unintentional overdose, new research suggests.

Investigators found the risk for self-harm was three times higher, all-cause mortality was 59% higher, unintentional overdose was 2.5 times higher, and homicide was more than three times higher in those with versus without CUD.

“The take-home message of these findings is that we need to be aware of the perception that cannabis use is harmless, when it’s actually not,” lead author Cynthia Fontanella, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in an interview.

“We need to educate parents and clinicians that there are risks associated with cannabis, including increased risk for self-harm and death, and we need to effectively treat both cannabis use disorder and mood disorders,” she said.

The study was published online Jan. 19, 2021, in JAMA Pediatrics.

Little research in youth

“There has been very little research conducted on CUD in the adolescent population, and most studies have been conducted with adults,” Dr. Fontanella said.

Research on adults has shown that, even in people without mood disorders, cannabis use is associated with the early onset of mood disorders, psychosis, and anxiety disorders and has also been linked with suicidal behavior and increased risk for motor vehicle accidents, Dr. Fontanella said.

“We were motivated to conduct this study because we treat kids with depression and bipolar disorder and we noticed a high prevalence of CUD in this population, so we were curious about what its negative effects might be,” Dr. Fontanella recounted.

The researchers analyzed 7-year data drawn from Ohio Medicaid claims and linked to data from death certificates in 204,780 youths between the ages of 10 and 24 years (mean age was 17.2 years at the time of mood disorder diagnosis). Most were female, non-Hispanic White, enrolled in Medicaid because of poverty, and living in a metropolitan area (65.0%, 66.9%, 87.6%, and 77.1%, respectively).

Participants were followed up to 1 year from diagnosis until the end of enrollment, a self-harm event, or death.

Researchers included demographic, clinical, and treatment factors as covariates.

Close to three-quarters (72.7%) of the cohort had a depressive disorder, followed by unspecified/persistent mood disorder and bipolar disorder (14.9% and 12.4%, respectively). Comorbidities included ADHD (12.4%), anxiety disorder (12.3%), and other mental disorders (13.1%).

One -tenth of the cohort (10.3%) were diagnosed with CUD.

CUD treatment referrals

“Although CUD was associated with suicide in the unadjusted model, it was not significantly associated in adjusted models,” the authors reported.

Dr. Fontanella noted that the risk for these adverse outcomes is greater among those who engage in heavy, frequent use or who use cannabis that has higher-potency tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content.

Reasons why CUD might be associated with these adverse outcomes are that it can increase impulsivity, poor judgment, and clouded thinking, which may in turn increase the risk for self-harm behaviors, she said.

She recommended that clinicians refer youth with CUD for “effective treatments,” including family-based models and individual approaches, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational enhancement therapy.

Open dialogue

In a comment, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, adjunct clinical professor, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, noted that psychosis can occur in patients with CUD and mood disorders – especially bipolar disorder – but was not included as a study outcome. “I would have liked to see more data about that,” he said.

However, “The trend is that cannabis use is starting at younger and younger ages, which has all kinds of ramifications in terms of cerebral development.”

Christopher Hammond, MD, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said: “Three major strengths of the study are the size of the sample, its longitudinal analysis, and that the authors controlled for a number of potential confounding variables.”

In light of the findings, Dr. Hammond recommended clinicians and other health professionals who work with young people “should screen for cannabis-related problems in youth with mood disorders.”

Dr. Hammond, who is the director of the Co-occurring Disorders in Adolescents and Young Adults Clinical and Research Program, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, and was not involved with the study, recommended counseling youth with mood disorders and their parents and families “regarding the potential adverse health effects related to cannabis use.”

He also recommended “open dialogue with youth with and without mental health conditions about misleading reports in the national media and advertising about cannabis’ health benefits.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Fontanella reported receiving grants from the National Institute of Mental Health during the conduct of the study. Dr. Raby reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Hammond reported receiving research grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, the National Network of Depression Centers, and the Armstrong Institute at Johns Hopkins Bayview and serves as a scientific adviser for the National Courts and Science Institute and as a subject matter expert for SAMHSA related to co-occurring substance use disorders and severe emotional disturbance in youth.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Give women's mental health a seat at the health care table

Why it’s time for women’s mental health to be recognized as the subspecialty it already is

It wasn’t until I (Dr. Leistikow) finished my psychiatry residency that I realized the training I had received in women’s mental health was unusual. It was simply a required experience for PGY-3 residents at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

All of us, regardless of interest, spent 1 afternoon a week over 6 months caring for patients in a specialty psychiatric clinic for women (run by Dr. Payne and Dr. Osborne). We discussed cases and received didactics on such topics as risk factors for postpartum depression; the risks of untreated mental illness in pregnancy, compared with the risks of various psychiatric medications; how to choose and dose medications for bipolar disorder as blood levels change across pregnancy; which resources to consult to determine the amounts and risks of various medications passed on in breast milk; and how to diagnose and treat premenstrual dysphoric disorder, to name a few lecture subjects.

By the time we were done, all residents had received more than 20 hours of teaching about how to treat mental illness in women across the reproductive life cycle. This was 20 hours more than is currently required by the American College of Graduate Medical Education, the accrediting body for all residencies, including psychiatry.1 It is time for that to change.

Women’s need for psychiatric treatment that addresses reproductive transitions is not new; it is as old as time. Not only do women who previously needed psychiatric treatment continue to need treatment when they get pregnant or are breastfeeding, but it is now well recognized that times of reproductive transition or flux – whether premenstrual, post partum, or perimenopausal – confer increased risk for both new-onset and exacerbations of prior mental illnesses.

What has changed is psychiatry’s ability to finally meet that need. Previously, despite the fact that women make up the majority of patients presenting for treatment, that nearly all women will menstruate and go through menopause, and that more than 80% of American women will have at least one pregnancy during their lifetime,psychiatrists practice as if these reproductive transitions were unfortunate blips getting in the doctor’s way.2 We mostly threw up our hands when our patients became pregnant, reflexively stopped all medications, and expected women to suffer for the sake of their babies.

with a large and growing research base, with both agreed-upon best practices and evolving standards of care informed by and responsive to the scientific literature. We now know that untreated maternal psychiatric illness carries its own risks for infants both before and after delivery; that many maternal pharmacologic treatments are lower risk for infants than previously thought; that protecting and treating women’s mental health in pregnancy has benefits for women, their babies, and the families that depend on them; and that there is now a growing evidence base informing both new and older treatments and enabling women and their doctors to make complex decisions balancing risk and benefit across the life cycle.

Many psychiatrists-in-training are hungry for this knowledge. At last count, in the United States alone, there were 16 women’s mental health fellowships available, up from just 3 in 2008.3 The problem is that none of them are accredited or funded by the ACGME, because reproductive psychiatry (here used interchangeably with the term women’s mental health) has not been officially recognized as a subspecialty. This means that current funding frequently rests on philanthropy, which often cannot be sustained, and clinical billing, which gives fellows in some programs such heavy clinical responsibilities that little time is left for scholarly work. Lack of subspecialty status also blocks numerous important downstream effects that would flow from this recognition.

Reproductive psychiatry clearly already meets criteria laid out by the American Board of Medical Specialties for defining a subspecialty field. As argued elsewhere, it has a distinct patient population with definable care needs and a standalone body of scientific medical knowledge as well as a national (and international) community of experts that has already done much to improve women’s access to care they desperately need.4 It also meets the ACGME’s criteria for a new subspecialty except for approval by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology.5 Finally, it also meets the requirements of the ABPN except for having 25 fellowship programs with 50 fellowship positions and 50 trainees per year completing fellowships, a challenging Catch-22 without the necessary funding that would accrue from accreditation.6

Despite growing awareness and demand, there remains a shortage of psychiatrists trained to treat women during times of reproductive transition and to pass their recommendations and knowledge on to their primary care and ob.gyn. colleagues. What official recognition would bring, in addition to funding for fellowships post residency, is a guaranteed seat at the table in psychiatry residencies, in terms of a required number of hours devoted to these topics for trainees, ensuring that all graduating psychiatrists have at least some exposure to the knowledge and practices so material to their patients.

It isn’t enough to wait for residencies to see the writing on the wall and voluntarily carve out a slice of pie devoted to women’s mental health from the limited time and resources available to train residents. A 2017 survey of psychiatry residency program training directors found that 23%, or almost a quarter of programs that responded, offered no reproductive psychiatry training at all, that 49% required 5 hours or less across all 4 years of training, and that 75% of programs had no required clinical exposure to reproductive psychiatry patients.7 Despite the fact that 87% of training directors surveyed agreed either that reproductive psychiatry was “an important area of education” or a subject general residents should be competent in, ACGME-recognized specialties take precedence.

A system so patchy and insufficient won’t do. It’s not good enough for the trainees who frequently have to look outside of their own institutions for the training they know they need. It’s not good enough for the pregnant or postpartum patient looking for evidence-based advice, who is currently left on her own to determine, prior to booking an appointment, whether a specific psychiatrist has received any training relevant to treating her. Adding reproductive psychiatry to the topics a graduating psychiatrist must have some proficiency in also signals to recent graduates and experienced attendings, as well as the relevant examining boards and producers of continuing medical education content, that women’s mental health is no longer a fringe topic but rather foundational to all practicing psychiatrists.

The oil needed to prime this pump is official recognition of the subspecialty that reproductive psychiatry already is. The women’s mental health community is ready. The research base is well established and growing exponentially. The number of women’s mental health fellowships is healthy and would increase significantly with ACGME funding. Psychiatry residency training programs can turn to recent graduates of these fellowships as well as their own faculty with reproductive psychiatry experience to teach trainees. In addition, the National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry, over the last 4 years, has created a repository of free online modules dedicated to facilitating this type of training, with case discussions across numerous topics for use by both educators and trainees. The American Psychiatric Association recently formed the Committee on Women’s Mental Health in 2020 and will be publishing a textbook based on work done by the NCRP within the coming year.

Imagine the changed world that would open to all psychiatrists if reproductive psychiatry were given the credentials it deserves. When writing prescriptions, we would view pregnancy as the potential outcome it is in any woman of reproductive age, given that 50% of pregnancies are unplanned, and let women know ahead of time how to think about possible fetal effects rather than waiting for their panicked phone messages or hearing that they have stopped their medications abruptly. We would work to identify our patient’s individual risk factors for postpartum depression predelivery to reduce that risk and prevent or limit illness. We would plan ahead for close follow-up post partum during the window of greatest risk, rather than expecting women to drop out of care while taking care of their infants or languish on scheduling waiting lists. We would feel confident in giving evidence-based advice to our patients around times of reproductive transition across the life cycle, but especially in pregnancy and lactation, empowering women to make healthy decisions for themselves and their families, no longer abandoning them just when they need us most.

References

1. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Psychiatry. Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education. 2020 Jul 1.

2. Livingston G. “They’re waiting longer, but U.S. women today more likely to have children than a decade ago.” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. pewsocialtrends.org. 2018 Jan 18.

3. Nagle-Yang S et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2018 Apr;42(2):202-6.

4. Payne JL. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019 May;31(3):207-9.

5. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Policies and Procedures. 2020 Sep 26.

6. American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Requirements for Subspecialty Recognition, Attachment A. 2008.

7. Osborne LM et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2018 Apr;42(2):197-201.

Dr. Leistikow is a reproductive psychiatrist and clinical assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, where she sees patients and helps train residents and fellows. She is on the education committee of the National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry (NCRPtraining.org) and has written about women’s mental health for textbooks, scientific journals and on her private practice blog at www.womenspsychiatrybaltimore.com. Dr. Leistikow has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Payne is associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and director of the Women’s Mood Disorders Center at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. In addition to providing outstanding clinical care for women with mood disorders, she conducts research into the genetic, biological, and environmental factors involved in postpartum depression. She and her colleagues have recently identified two epigenetic biomarkers of postpartum depression and are working hard to replicate this work with National Institutes of Health funding. Most recently, she was appointed to the American Psychiatric Association’s committee on women’s mental health and is serving as president-elect for both the Marcé of North America and the International Marcé Perinatal Mental Health Societies. She disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Sage Therapeutics and Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Osborne is associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University, where she directs a postdoctoral fellowship program in reproductive psychiatry. She is an expert on the diagnosis and treatment of mood and anxiety disorders during pregnancy, the post partum, the premenstrual period, and perimenopause. Her work is supported by the Brain and Behavior Foundation, the Doris Duke Foundation, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, and the National Institute of Mental Health. She has no conflicts of interest.

Why it’s time for women’s mental health to be recognized as the subspecialty it already is

Why it’s time for women’s mental health to be recognized as the subspecialty it already is

It wasn’t until I (Dr. Leistikow) finished my psychiatry residency that I realized the training I had received in women’s mental health was unusual. It was simply a required experience for PGY-3 residents at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.