User login

Lithium and kidney disease: Understand the risks

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

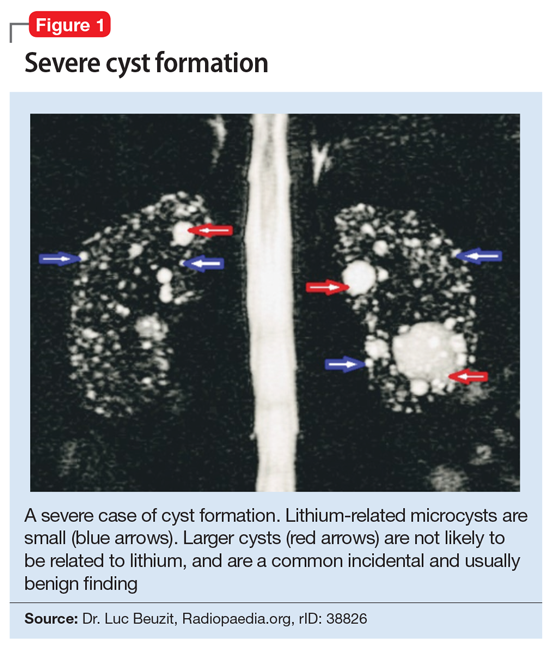

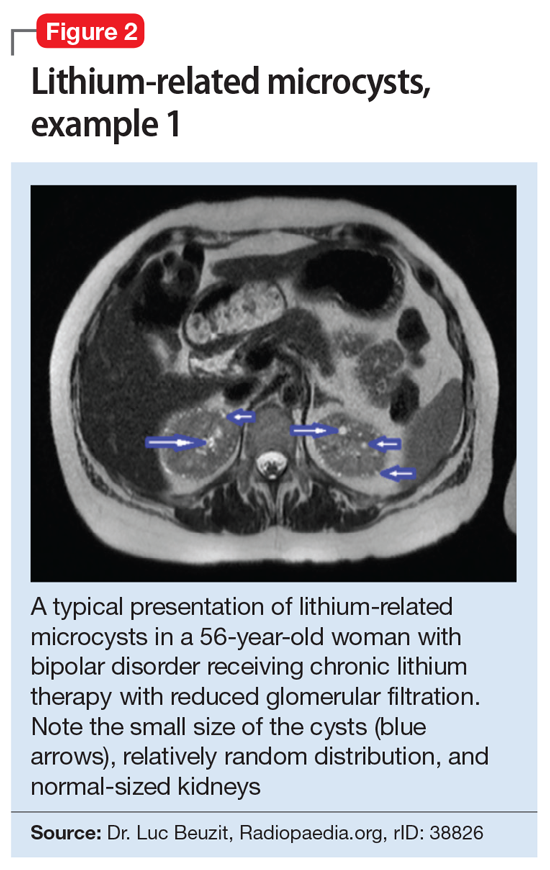

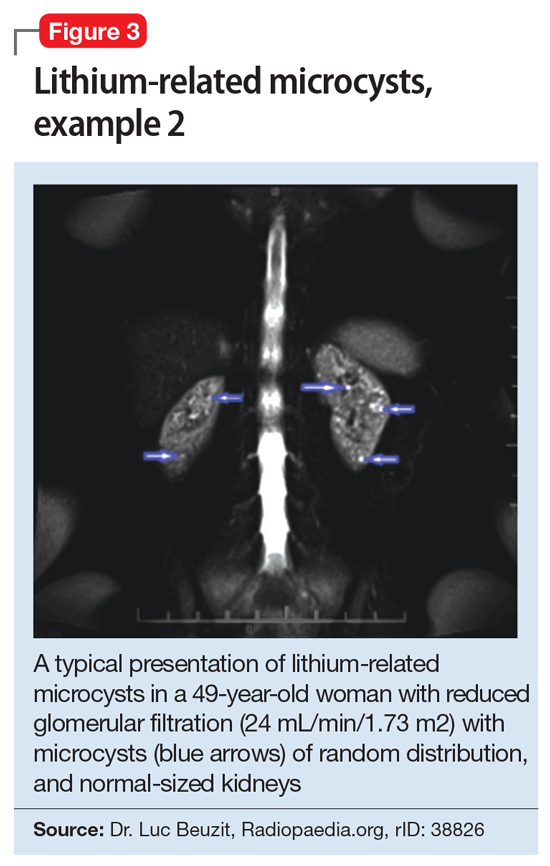

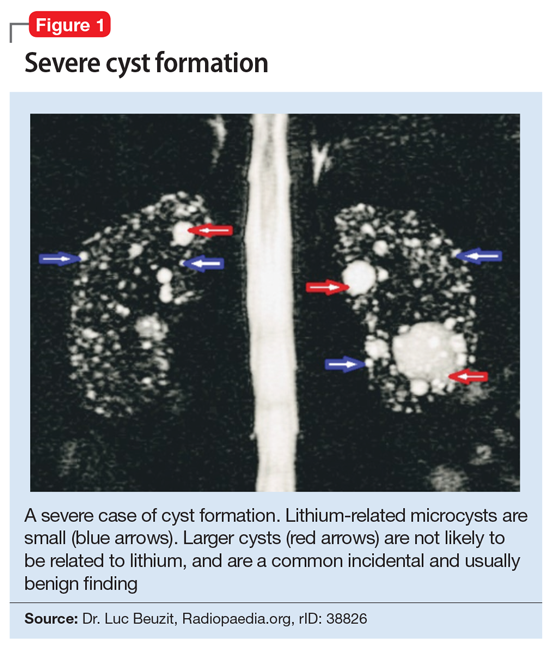

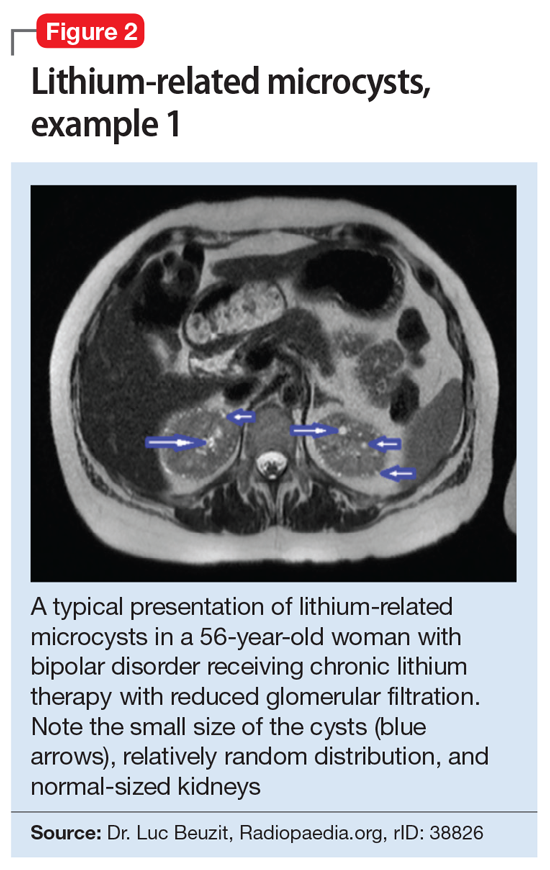

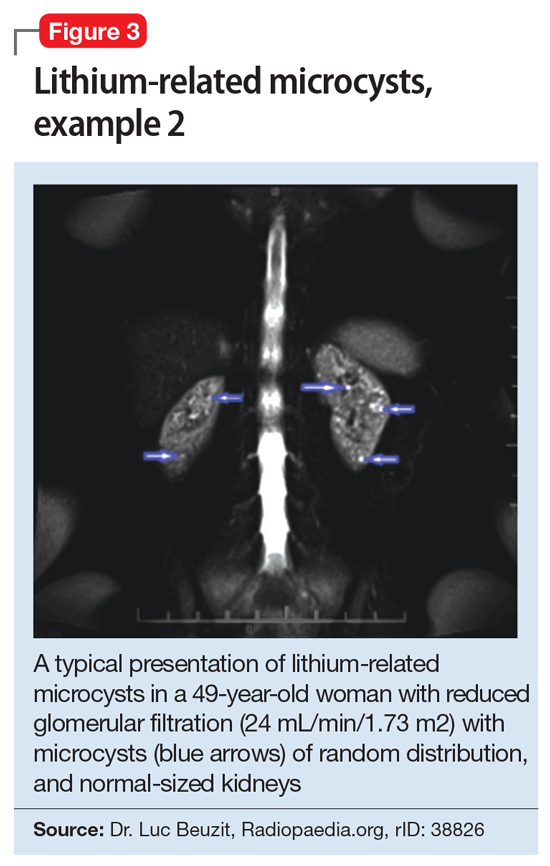

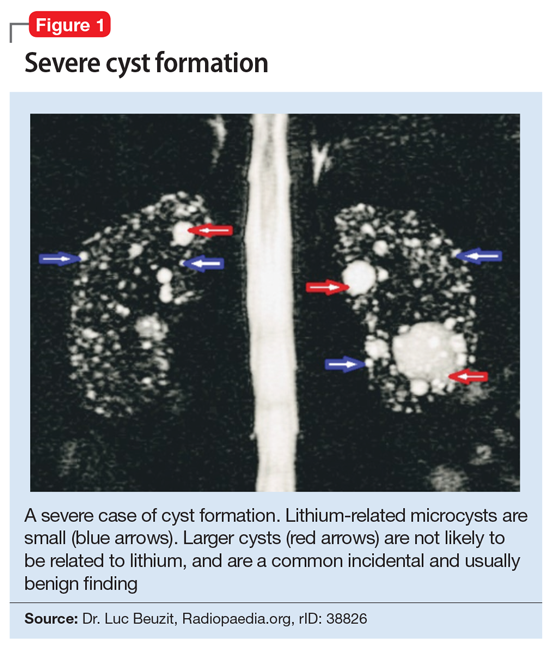

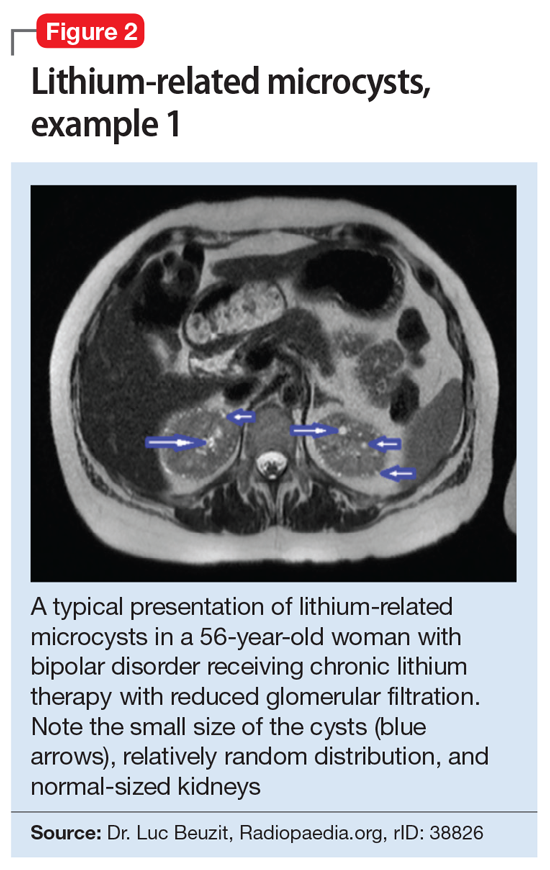

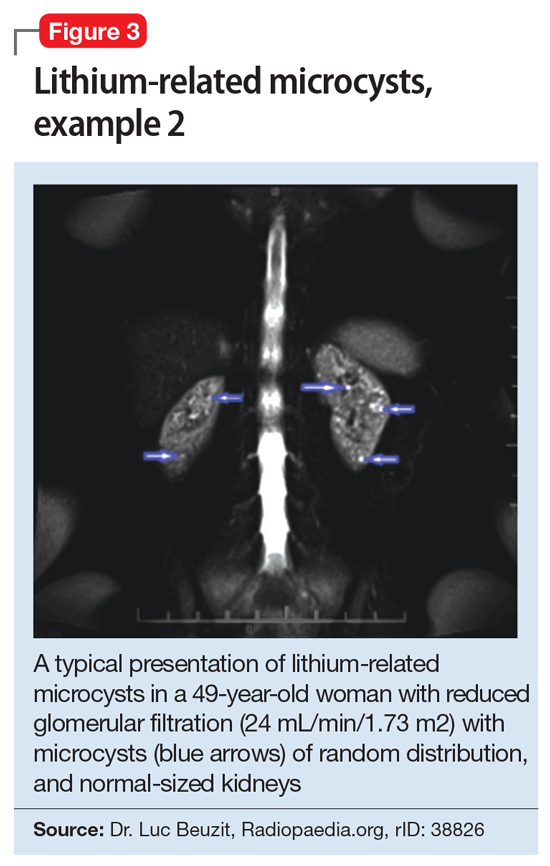

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

1. Severus E, Bauer M, Geddes J. Efficacy and effectiveness of lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: an update 2018. Pharamacopsychiatry. 2018;51(5):173-176.

2. Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575-586.

3. El-Mallakh RS. Lithium: actions and mechanisms. Progress in Psychiatry Series, 50. American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

4. Gitlin M. Why is not lithium prescribed more often? Here are the reasons. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016, 29:293-297.

5. Kessing LV, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Andersen PK, et al. Continuation of lithium after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):615-622.

6. Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1439-1448.

7. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):448-455.

8. Yazici O, Kora K, Polat A, et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long-term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):269-271.

9. Rosso G, Solia F, Albert U, et al. Affective recurrences in bipolar disorder after switching from lithium to valproate or vice versa: a series of 57 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):278-281.

10. Werneke U, Ott M, Renberg ES, et al. A decision analysis of long-term lithium treatment and the risk of renal failure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):186-197.

11. Sani G, Perugi G, Tondo L. Treatment of bipolar disorder in a lifetime perspective: is lithium still the best choice? Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(8):713-727.

12. Vestergaard P, Amdisen A. Lithium treatment and kidney function: a follow-up study of 237 patients in long-term treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63(4):333-345.

13. Walker RG, Bennett WM, Davies BM, et al. Structural and functional effects of long-term lithium therapy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1982;11:S13-S19.

14. Coskunol H, Vahip S, Mees ED, et al. Renal side-effects of long-term lithium treatment. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(1):5-10.

15. Paul R, Minay J, Cardwell C, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of lithium usage on serum creatinine levels. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(10):1425-1431.

16. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

17. Turan T, Esel E, Tokgöz B, et al. Effects of short- and long-term lithium treatment on kidney functioning in patients with bipolar mood disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):561-565.

18. Presne C, Fakhouri F, Noël LH, et al. Lithium-induced nephropathy: rate of progression and prognostic factors. Kidney Int. 2003;64(2):585-592.

19. McCann SM, Daly J, Kelly CB. The impact of long-term lithium treatment on renal function in an outpatient population. Ulster Med J. 2008;77(2):102-105.

20. Kripalani M, Shawcross J, Reilly J, et al. Lithium and chronic kidney disease. BMJ. 2009;339:b2452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2452

21. Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, et al. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):219-224. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.433

22. Aiff H, Attman PO, Aurell M, et al. The impact of modern treatment principles may have eliminated lithium-induced renal failure. J Psychopharmacol. 2014; 28(2):151-154.

23. Boton R, Gaviria M, Batlle DC. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment of renal dysfunction associated with chronic lithium therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10(5):329-345.

24. Bocchetta A, Ardau R, Fanni T, et al. Renal function during long-term lithium treatment: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2015, 21;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0249-4

25. Tredget J, Kirov A, Kirov G. Effects of chronic lithium treatment on renal function. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):436-440.

26. Adam WR, Schweitzer I, Walker BG. Trade-off between the benefits of lithium treatment and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2012,17(8):776-779.

27. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):1-9.

28. Trepiccione F, Christensen BM. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: new clinical and experimental findings. J Nephrol. 2010;23 Suppl 16:S43-S48.

29. Gong R, Wang P, Dworkin L. What we need to know about the effect of lithium on the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(6):F1168-F1171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2016

30. Golshayan D, Nseir G, Venetz JP, et al. MR imaging as a specific diagnostic tool for bilateral microcysts in chronic lithium nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):601. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.449

31. Di Salvo DN, Park J, Laing FC. Lithium nephropathy: Unique sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):637-644.

32. Jon´czyk-Potoczna K, Abramowicz M, Chłopocka-Woz´niak M, et al. Renal sonography in bipolar patients on long-term lithium treatment. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44(6):354-359.

33. Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D, et al. Chronic lithium nephropathy: MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiol. 2003;229(2):570-574.

34. Roque A, Herédia V, Ramalho M, et al. MR findings of lithium-related kidney disease: preliminary observations in four patients. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37(1):140-146.

35. Farshchian N, Farnia V, Aghaiani M, et al. MRI findings and renal function in patients on long-term lithium therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2013; 28(Sl):1. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77306-1

36. Wood CG 3rd, Stromberg LJ 3rd, Harmath CB, et al. CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):125-141.

37. Khan M, El-Mallakh RS. Renal microcysts and lithium. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(3):290-298.

38. Gao Y, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Cai Q, et al. Rapamycin inhibition of mTORC1 reverses lithium-induced proliferation of renal collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(8):1201-1208.

39. Pap M, Cooper GM. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998:273(32):19929-19932.

40. Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6(12):1664-1668.

41. Rao R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulation of urinary concentrating ability. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21(5):541-546.

42. Diniz BS, Machado Vieira R, Forlenza OV. Lithium and neuroprotection: translational evidence and implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:493-500. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S33086

43. Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Marcussen N, et al. Tissue injury after lithium treatment in human and rat postnatal kidney involves glycogen synthase kinase-3β-positive epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(4):455-465.

44. Zhang C, Zhu J, Zhang J, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of valproic acid on adult rat cerebral cortex through ERK and Akt signaling pathway at acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014;1555:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.051

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

1. Severus E, Bauer M, Geddes J. Efficacy and effectiveness of lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: an update 2018. Pharamacopsychiatry. 2018;51(5):173-176.

2. Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575-586.

3. El-Mallakh RS. Lithium: actions and mechanisms. Progress in Psychiatry Series, 50. American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

4. Gitlin M. Why is not lithium prescribed more often? Here are the reasons. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016, 29:293-297.

5. Kessing LV, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Andersen PK, et al. Continuation of lithium after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):615-622.

6. Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1439-1448.

7. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):448-455.

8. Yazici O, Kora K, Polat A, et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long-term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):269-271.

9. Rosso G, Solia F, Albert U, et al. Affective recurrences in bipolar disorder after switching from lithium to valproate or vice versa: a series of 57 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):278-281.

10. Werneke U, Ott M, Renberg ES, et al. A decision analysis of long-term lithium treatment and the risk of renal failure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):186-197.

11. Sani G, Perugi G, Tondo L. Treatment of bipolar disorder in a lifetime perspective: is lithium still the best choice? Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(8):713-727.

12. Vestergaard P, Amdisen A. Lithium treatment and kidney function: a follow-up study of 237 patients in long-term treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63(4):333-345.

13. Walker RG, Bennett WM, Davies BM, et al. Structural and functional effects of long-term lithium therapy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1982;11:S13-S19.

14. Coskunol H, Vahip S, Mees ED, et al. Renal side-effects of long-term lithium treatment. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(1):5-10.

15. Paul R, Minay J, Cardwell C, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of lithium usage on serum creatinine levels. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(10):1425-1431.

16. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

17. Turan T, Esel E, Tokgöz B, et al. Effects of short- and long-term lithium treatment on kidney functioning in patients with bipolar mood disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):561-565.

18. Presne C, Fakhouri F, Noël LH, et al. Lithium-induced nephropathy: rate of progression and prognostic factors. Kidney Int. 2003;64(2):585-592.

19. McCann SM, Daly J, Kelly CB. The impact of long-term lithium treatment on renal function in an outpatient population. Ulster Med J. 2008;77(2):102-105.

20. Kripalani M, Shawcross J, Reilly J, et al. Lithium and chronic kidney disease. BMJ. 2009;339:b2452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2452

21. Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, et al. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):219-224. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.433

22. Aiff H, Attman PO, Aurell M, et al. The impact of modern treatment principles may have eliminated lithium-induced renal failure. J Psychopharmacol. 2014; 28(2):151-154.

23. Boton R, Gaviria M, Batlle DC. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment of renal dysfunction associated with chronic lithium therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10(5):329-345.

24. Bocchetta A, Ardau R, Fanni T, et al. Renal function during long-term lithium treatment: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2015, 21;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0249-4

25. Tredget J, Kirov A, Kirov G. Effects of chronic lithium treatment on renal function. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):436-440.

26. Adam WR, Schweitzer I, Walker BG. Trade-off between the benefits of lithium treatment and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2012,17(8):776-779.

27. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):1-9.

28. Trepiccione F, Christensen BM. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: new clinical and experimental findings. J Nephrol. 2010;23 Suppl 16:S43-S48.

29. Gong R, Wang P, Dworkin L. What we need to know about the effect of lithium on the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(6):F1168-F1171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2016

30. Golshayan D, Nseir G, Venetz JP, et al. MR imaging as a specific diagnostic tool for bilateral microcysts in chronic lithium nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):601. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.449

31. Di Salvo DN, Park J, Laing FC. Lithium nephropathy: Unique sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):637-644.

32. Jon´czyk-Potoczna K, Abramowicz M, Chłopocka-Woz´niak M, et al. Renal sonography in bipolar patients on long-term lithium treatment. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44(6):354-359.

33. Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D, et al. Chronic lithium nephropathy: MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiol. 2003;229(2):570-574.

34. Roque A, Herédia V, Ramalho M, et al. MR findings of lithium-related kidney disease: preliminary observations in four patients. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37(1):140-146.

35. Farshchian N, Farnia V, Aghaiani M, et al. MRI findings and renal function in patients on long-term lithium therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2013; 28(Sl):1. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77306-1

36. Wood CG 3rd, Stromberg LJ 3rd, Harmath CB, et al. CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):125-141.

37. Khan M, El-Mallakh RS. Renal microcysts and lithium. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(3):290-298.

38. Gao Y, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Cai Q, et al. Rapamycin inhibition of mTORC1 reverses lithium-induced proliferation of renal collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(8):1201-1208.

39. Pap M, Cooper GM. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998:273(32):19929-19932.

40. Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6(12):1664-1668.

41. Rao R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulation of urinary concentrating ability. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21(5):541-546.

42. Diniz BS, Machado Vieira R, Forlenza OV. Lithium and neuroprotection: translational evidence and implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:493-500. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S33086

43. Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Marcussen N, et al. Tissue injury after lithium treatment in human and rat postnatal kidney involves glycogen synthase kinase-3β-positive epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(4):455-465.

44. Zhang C, Zhu J, Zhang J, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of valproic acid on adult rat cerebral cortex through ERK and Akt signaling pathway at acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014;1555:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.051

1. Severus E, Bauer M, Geddes J. Efficacy and effectiveness of lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: an update 2018. Pharamacopsychiatry. 2018;51(5):173-176.

2. Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575-586.

3. El-Mallakh RS. Lithium: actions and mechanisms. Progress in Psychiatry Series, 50. American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

4. Gitlin M. Why is not lithium prescribed more often? Here are the reasons. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016, 29:293-297.

5. Kessing LV, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Andersen PK, et al. Continuation of lithium after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):615-622.

6. Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1439-1448.

7. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):448-455.

8. Yazici O, Kora K, Polat A, et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long-term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):269-271.

9. Rosso G, Solia F, Albert U, et al. Affective recurrences in bipolar disorder after switching from lithium to valproate or vice versa: a series of 57 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):278-281.

10. Werneke U, Ott M, Renberg ES, et al. A decision analysis of long-term lithium treatment and the risk of renal failure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):186-197.

11. Sani G, Perugi G, Tondo L. Treatment of bipolar disorder in a lifetime perspective: is lithium still the best choice? Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(8):713-727.

12. Vestergaard P, Amdisen A. Lithium treatment and kidney function: a follow-up study of 237 patients in long-term treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63(4):333-345.

13. Walker RG, Bennett WM, Davies BM, et al. Structural and functional effects of long-term lithium therapy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1982;11:S13-S19.

14. Coskunol H, Vahip S, Mees ED, et al. Renal side-effects of long-term lithium treatment. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(1):5-10.

15. Paul R, Minay J, Cardwell C, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of lithium usage on serum creatinine levels. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(10):1425-1431.

16. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

17. Turan T, Esel E, Tokgöz B, et al. Effects of short- and long-term lithium treatment on kidney functioning in patients with bipolar mood disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):561-565.

18. Presne C, Fakhouri F, Noël LH, et al. Lithium-induced nephropathy: rate of progression and prognostic factors. Kidney Int. 2003;64(2):585-592.

19. McCann SM, Daly J, Kelly CB. The impact of long-term lithium treatment on renal function in an outpatient population. Ulster Med J. 2008;77(2):102-105.

20. Kripalani M, Shawcross J, Reilly J, et al. Lithium and chronic kidney disease. BMJ. 2009;339:b2452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2452

21. Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, et al. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):219-224. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.433

22. Aiff H, Attman PO, Aurell M, et al. The impact of modern treatment principles may have eliminated lithium-induced renal failure. J Psychopharmacol. 2014; 28(2):151-154.

23. Boton R, Gaviria M, Batlle DC. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment of renal dysfunction associated with chronic lithium therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10(5):329-345.

24. Bocchetta A, Ardau R, Fanni T, et al. Renal function during long-term lithium treatment: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2015, 21;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0249-4

25. Tredget J, Kirov A, Kirov G. Effects of chronic lithium treatment on renal function. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):436-440.

26. Adam WR, Schweitzer I, Walker BG. Trade-off between the benefits of lithium treatment and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2012,17(8):776-779.

27. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):1-9.

28. Trepiccione F, Christensen BM. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: new clinical and experimental findings. J Nephrol. 2010;23 Suppl 16:S43-S48.

29. Gong R, Wang P, Dworkin L. What we need to know about the effect of lithium on the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(6):F1168-F1171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2016

30. Golshayan D, Nseir G, Venetz JP, et al. MR imaging as a specific diagnostic tool for bilateral microcysts in chronic lithium nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):601. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.449

31. Di Salvo DN, Park J, Laing FC. Lithium nephropathy: Unique sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):637-644.

32. Jon´czyk-Potoczna K, Abramowicz M, Chłopocka-Woz´niak M, et al. Renal sonography in bipolar patients on long-term lithium treatment. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44(6):354-359.

33. Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D, et al. Chronic lithium nephropathy: MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiol. 2003;229(2):570-574.

34. Roque A, Herédia V, Ramalho M, et al. MR findings of lithium-related kidney disease: preliminary observations in four patients. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37(1):140-146.

35. Farshchian N, Farnia V, Aghaiani M, et al. MRI findings and renal function in patients on long-term lithium therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2013; 28(Sl):1. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77306-1

36. Wood CG 3rd, Stromberg LJ 3rd, Harmath CB, et al. CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):125-141.

37. Khan M, El-Mallakh RS. Renal microcysts and lithium. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(3):290-298.

38. Gao Y, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Cai Q, et al. Rapamycin inhibition of mTORC1 reverses lithium-induced proliferation of renal collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(8):1201-1208.

39. Pap M, Cooper GM. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998:273(32):19929-19932.

40. Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6(12):1664-1668.

41. Rao R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulation of urinary concentrating ability. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21(5):541-546.

42. Diniz BS, Machado Vieira R, Forlenza OV. Lithium and neuroprotection: translational evidence and implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:493-500. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S33086

43. Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Marcussen N, et al. Tissue injury after lithium treatment in human and rat postnatal kidney involves glycogen synthase kinase-3β-positive epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(4):455-465.

44. Zhang C, Zhu J, Zhang J, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of valproic acid on adult rat cerebral cortex through ERK and Akt signaling pathway at acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014;1555:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.051

APA, AMA, others move to stop insurer from overturning mental health claims ruling

The American Psychiatric Association has joined with the American Medical Association and other medical societies to oppose United Behavioral Health’s (UBH) request that a court throw out a ruling that found the insurer unfairly denied tens of thousands of claims for mental health and substance use disorder services.

Wit v. United Behavioral Health, in litigation since 2014, is being closely watched by clinicians, patients, providers, and attorneys.

Reena Kapoor, MD, chair of the APA’s Committee on Judicial Action, said in an interview that the APA is hopeful that “whatever the court says about UBH should be applicable to all insurance companies that are providing employer-sponsored health benefits.”

In a friend of the court (amicus curiae) brief, the APA, AMA, the California Medical Association, Southern California Psychiatric Society, Northern California Psychiatric Society, Orange County Psychiatric Society, Central California Psychiatric Society, and San Diego Psychiatric Society argue that “despite the availability of professionally developed, evidence-based guidelines embodying generally accepted standards of care for mental health and substance use disorders, managed care organizations commonly base coverage decisions on internally developed ‘level of care guidelines’ that are inappropriately restrictive.”

The guidelines “may lead to denial of coverage for treatment that is recommended by a patient’s physician and even cut off coverage when treatment is already being delivered,” said the groups.

The U.S. Department of Labor also filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs who are suing UBH. Those individuals suffered injury when they were denied coverage, said the federal agency, which regulates employer-sponsored insurance plans.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta also made an amicus filing supporting the plaintiffs.

“When insurers limit access to this critical care, they leave Californians who need it feeling as if they have no other option than to try to cope alone,” said Mr. Bonta in a statement.

‘Discrimination must end’

Mr. Bonta said he agreed with a 2019 ruling by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California that UBH had violated its fiduciary duties by wrongfully using its internally developed coverage determination guidelines and level of care guidelines to deny care.

The court also found that UBH’s medically necessary criteria meant that only “acute” episodes would be covered. Instead, said the court last November, chronic and comorbid conditions should always be treated, according to Maureen Gammon and Kathleen Rosenow of Willis Towers Watson, a risk advisor.

In November, the same Northern California District Court ruled on the remedies it would require of United, including that the insurer reprocess more than 67,000 claims. UBH was also barred indefinitely from using any of its guidelines to make coverage determinations. Instead, it was ordered to make determinations “consistent with generally accepted standards of care,” and consistent with state laws.

The District Court denied a request by UBH to put a hold on the claims reprocessing until it appealed the overall case. But the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in February granted that request.

Then, in March, United appealed the District Court’s overall ruling, claiming that the plaintiffs had not proven harm.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed a brief in support of United, agreeing with its arguments.

However, the APA and other clinician groups said there is no question of harm.

“Failure to provide appropriate levels of care for treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders leads to relapse, overdose, transmission of infectious diseases, and death,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, MPA, in a statement.

APA President Vivian Pender, MD, said guidelines that “are overly focused on stabilizing acute symptoms of mental health and substance use disorders” are not treating the underlying disease. “When the injury is physical, insurers treat the underlying disease and not just the symptoms. Discrimination against patients with mental illness must end,” she said.

No court has ever recognized the type of claims reprocessing ordered by the District Court judge, said attorneys Nathaniel Cohen and Joseph Laska of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, in an analysis of the case.

Mr. Cohen and Mr. Laska write. “Practitioners, health plans, and health insurers would be wise to track UBH’s long-awaited appeal to the Ninth Circuit.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Psychiatric Association has joined with the American Medical Association and other medical societies to oppose United Behavioral Health’s (UBH) request that a court throw out a ruling that found the insurer unfairly denied tens of thousands of claims for mental health and substance use disorder services.

Wit v. United Behavioral Health, in litigation since 2014, is being closely watched by clinicians, patients, providers, and attorneys.

Reena Kapoor, MD, chair of the APA’s Committee on Judicial Action, said in an interview that the APA is hopeful that “whatever the court says about UBH should be applicable to all insurance companies that are providing employer-sponsored health benefits.”

In a friend of the court (amicus curiae) brief, the APA, AMA, the California Medical Association, Southern California Psychiatric Society, Northern California Psychiatric Society, Orange County Psychiatric Society, Central California Psychiatric Society, and San Diego Psychiatric Society argue that “despite the availability of professionally developed, evidence-based guidelines embodying generally accepted standards of care for mental health and substance use disorders, managed care organizations commonly base coverage decisions on internally developed ‘level of care guidelines’ that are inappropriately restrictive.”

The guidelines “may lead to denial of coverage for treatment that is recommended by a patient’s physician and even cut off coverage when treatment is already being delivered,” said the groups.

The U.S. Department of Labor also filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs who are suing UBH. Those individuals suffered injury when they were denied coverage, said the federal agency, which regulates employer-sponsored insurance plans.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta also made an amicus filing supporting the plaintiffs.

“When insurers limit access to this critical care, they leave Californians who need it feeling as if they have no other option than to try to cope alone,” said Mr. Bonta in a statement.

‘Discrimination must end’

Mr. Bonta said he agreed with a 2019 ruling by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California that UBH had violated its fiduciary duties by wrongfully using its internally developed coverage determination guidelines and level of care guidelines to deny care.

The court also found that UBH’s medically necessary criteria meant that only “acute” episodes would be covered. Instead, said the court last November, chronic and comorbid conditions should always be treated, according to Maureen Gammon and Kathleen Rosenow of Willis Towers Watson, a risk advisor.

In November, the same Northern California District Court ruled on the remedies it would require of United, including that the insurer reprocess more than 67,000 claims. UBH was also barred indefinitely from using any of its guidelines to make coverage determinations. Instead, it was ordered to make determinations “consistent with generally accepted standards of care,” and consistent with state laws.

The District Court denied a request by UBH to put a hold on the claims reprocessing until it appealed the overall case. But the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in February granted that request.

Then, in March, United appealed the District Court’s overall ruling, claiming that the plaintiffs had not proven harm.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed a brief in support of United, agreeing with its arguments.

However, the APA and other clinician groups said there is no question of harm.

“Failure to provide appropriate levels of care for treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders leads to relapse, overdose, transmission of infectious diseases, and death,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, MPA, in a statement.

APA President Vivian Pender, MD, said guidelines that “are overly focused on stabilizing acute symptoms of mental health and substance use disorders” are not treating the underlying disease. “When the injury is physical, insurers treat the underlying disease and not just the symptoms. Discrimination against patients with mental illness must end,” she said.

No court has ever recognized the type of claims reprocessing ordered by the District Court judge, said attorneys Nathaniel Cohen and Joseph Laska of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, in an analysis of the case.

Mr. Cohen and Mr. Laska write. “Practitioners, health plans, and health insurers would be wise to track UBH’s long-awaited appeal to the Ninth Circuit.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Psychiatric Association has joined with the American Medical Association and other medical societies to oppose United Behavioral Health’s (UBH) request that a court throw out a ruling that found the insurer unfairly denied tens of thousands of claims for mental health and substance use disorder services.

Wit v. United Behavioral Health, in litigation since 2014, is being closely watched by clinicians, patients, providers, and attorneys.

Reena Kapoor, MD, chair of the APA’s Committee on Judicial Action, said in an interview that the APA is hopeful that “whatever the court says about UBH should be applicable to all insurance companies that are providing employer-sponsored health benefits.”

In a friend of the court (amicus curiae) brief, the APA, AMA, the California Medical Association, Southern California Psychiatric Society, Northern California Psychiatric Society, Orange County Psychiatric Society, Central California Psychiatric Society, and San Diego Psychiatric Society argue that “despite the availability of professionally developed, evidence-based guidelines embodying generally accepted standards of care for mental health and substance use disorders, managed care organizations commonly base coverage decisions on internally developed ‘level of care guidelines’ that are inappropriately restrictive.”

The guidelines “may lead to denial of coverage for treatment that is recommended by a patient’s physician and even cut off coverage when treatment is already being delivered,” said the groups.

The U.S. Department of Labor also filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs who are suing UBH. Those individuals suffered injury when they were denied coverage, said the federal agency, which regulates employer-sponsored insurance plans.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta also made an amicus filing supporting the plaintiffs.

“When insurers limit access to this critical care, they leave Californians who need it feeling as if they have no other option than to try to cope alone,” said Mr. Bonta in a statement.

‘Discrimination must end’

Mr. Bonta said he agreed with a 2019 ruling by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California that UBH had violated its fiduciary duties by wrongfully using its internally developed coverage determination guidelines and level of care guidelines to deny care.

The court also found that UBH’s medically necessary criteria meant that only “acute” episodes would be covered. Instead, said the court last November, chronic and comorbid conditions should always be treated, according to Maureen Gammon and Kathleen Rosenow of Willis Towers Watson, a risk advisor.

In November, the same Northern California District Court ruled on the remedies it would require of United, including that the insurer reprocess more than 67,000 claims. UBH was also barred indefinitely from using any of its guidelines to make coverage determinations. Instead, it was ordered to make determinations “consistent with generally accepted standards of care,” and consistent with state laws.

The District Court denied a request by UBH to put a hold on the claims reprocessing until it appealed the overall case. But the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in February granted that request.

Then, in March, United appealed the District Court’s overall ruling, claiming that the plaintiffs had not proven harm.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed a brief in support of United, agreeing with its arguments.

However, the APA and other clinician groups said there is no question of harm.

“Failure to provide appropriate levels of care for treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders leads to relapse, overdose, transmission of infectious diseases, and death,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, MPA, in a statement.

APA President Vivian Pender, MD, said guidelines that “are overly focused on stabilizing acute symptoms of mental health and substance use disorders” are not treating the underlying disease. “When the injury is physical, insurers treat the underlying disease and not just the symptoms. Discrimination against patients with mental illness must end,” she said.

No court has ever recognized the type of claims reprocessing ordered by the District Court judge, said attorneys Nathaniel Cohen and Joseph Laska of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, in an analysis of the case.

Mr. Cohen and Mr. Laska write. “Practitioners, health plans, and health insurers would be wise to track UBH’s long-awaited appeal to the Ninth Circuit.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders higher in adult cerebral palsy patients

Adults with cerebral palsy, especially those with intellectual disabilities, are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, compared with the general population, a review of seven datasets shows.

The body of literature on psychiatric issues in children with cerebral palsy (CP) is increasing, but population-based studies of psychiatric issues in adults with CP have been limited in number and in scope. Most of those studies focus mainly on anxiety and depression, rather than on other issues such as psychosis or schizophrenia, Carly A. McMorris, PhD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues wrote.

In a retrospective, cross-sectional study published in Research in Developmental Disabilities, the researchers reviewed information from five health data sets, one registry, and census data for adults aged 18-64 years with a CP diagnosis living in Ontario, including those with and without diagnosed intellectual disabilities (ID) and a comparison group of individuals in the general population. The researchers examined the proportion of individuals with a psychiatric disorder in each of four groups: total CP, CP without ID, CP with ID, and the general population.

The study participants included 9,388 individuals with CP, 4,767 individuals with CP and ID, and a general population of 2,757,744 individuals. About half of the participants were male, and at least 85% lived in urban areas.

Overall, compared with the general population group, over a 2-year period (33.7 % vs. 24.7%). Also, the CP group was more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorder, or bipolar disorder, compared with the general population. Individuals with CP were significantly more likely to suffer from mood or affective disorders, and depression and anxiety disorders, compared with the general population, but less likely to suffer from substance use disorders.

When the data were assessed by ID status, disorders such as psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia were six times more common among individuals with CP and ID, compared with the general population (adjusted prevalence ratios, 6.26 and 6.46, respectively).