User login

Inflammatory markers may start in later stages of bipolar disorder

Interleukin-6, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) activity was associated with inflammation and neurodegeneration in patients with chronic bipolar disorder, according to Sercan Karabulut, MD, of Kepez State Hospital in Antalya, Turkey, and associates.

In a study published in the Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, the investigators collected enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays from 30 patients with early-stage bipolar disorder, 77 with chronic disease, and 30 healthy controls. Early-stage disease patients were significantly younger than chronic patients (25.3 years vs. 37.8 years). reported Dr. Karabulut and associates.

Patients with chronic bipolar disorder had significantly increased levels of all measured markers, compared with those with early-stage disease and the healthy controls. IL-6 and IL-1RA levels correlated with neuron-specific enolase and S100B, biomarkers that are associated with glial alterations and neuronal damage. TNF-alpha correlated with scores on the Clinical Global Impressions Scale and other measures.

“The present findings support in part the hypothesis that inflammation starts at later stages of [bipolar disorder], presumably as an associated effect of gliosis and neuronal loss, which appear to be particularly associated with IL-1RA and IL-6 activity,” the investigators wrote. “TNF-alpha ... might be a useful prognostic marker in patients with [bipolar disorder].”

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Karabulut S et al. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2019 Winter;30(2):75-81.

Interleukin-6, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) activity was associated with inflammation and neurodegeneration in patients with chronic bipolar disorder, according to Sercan Karabulut, MD, of Kepez State Hospital in Antalya, Turkey, and associates.

In a study published in the Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, the investigators collected enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays from 30 patients with early-stage bipolar disorder, 77 with chronic disease, and 30 healthy controls. Early-stage disease patients were significantly younger than chronic patients (25.3 years vs. 37.8 years). reported Dr. Karabulut and associates.

Patients with chronic bipolar disorder had significantly increased levels of all measured markers, compared with those with early-stage disease and the healthy controls. IL-6 and IL-1RA levels correlated with neuron-specific enolase and S100B, biomarkers that are associated with glial alterations and neuronal damage. TNF-alpha correlated with scores on the Clinical Global Impressions Scale and other measures.

“The present findings support in part the hypothesis that inflammation starts at later stages of [bipolar disorder], presumably as an associated effect of gliosis and neuronal loss, which appear to be particularly associated with IL-1RA and IL-6 activity,” the investigators wrote. “TNF-alpha ... might be a useful prognostic marker in patients with [bipolar disorder].”

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Karabulut S et al. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2019 Winter;30(2):75-81.

Interleukin-6, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), and tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) activity was associated with inflammation and neurodegeneration in patients with chronic bipolar disorder, according to Sercan Karabulut, MD, of Kepez State Hospital in Antalya, Turkey, and associates.

In a study published in the Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, the investigators collected enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays from 30 patients with early-stage bipolar disorder, 77 with chronic disease, and 30 healthy controls. Early-stage disease patients were significantly younger than chronic patients (25.3 years vs. 37.8 years). reported Dr. Karabulut and associates.

Patients with chronic bipolar disorder had significantly increased levels of all measured markers, compared with those with early-stage disease and the healthy controls. IL-6 and IL-1RA levels correlated with neuron-specific enolase and S100B, biomarkers that are associated with glial alterations and neuronal damage. TNF-alpha correlated with scores on the Clinical Global Impressions Scale and other measures.

“The present findings support in part the hypothesis that inflammation starts at later stages of [bipolar disorder], presumably as an associated effect of gliosis and neuronal loss, which appear to be particularly associated with IL-1RA and IL-6 activity,” the investigators wrote. “TNF-alpha ... might be a useful prognostic marker in patients with [bipolar disorder].”

No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Karabulut S et al. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2019 Winter;30(2):75-81.

FROM THE TURKISH JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

FGF21 could be tied to psychopathology of bipolar mania

Patients’ fibroblast growth factor–21 levels dropped after 4 weeks of taking antipsychotics

Fibroblast growth factor–21 (FGF21), a protein that regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, could be a biomarker in patients with bipolar mania, a new study suggests.

“In addition, our data indicates that FGF21 may monitor and/or prevent metabolic abnormalities induced by psychotropic drugs,” wrote Qing Hu of Xiamen City Xianyue Hospital, in Fujian, China, and associates. The study was published in Psychiatry Research.

To investigate how the expression of FGF21 changes in response to psychotropics taken by patients with bipolar mania, the researchers recruited 99 inpatients with bipolar mania with or without psychosis and 99 healthy controls. Eighty-two of the patients received psychotropics only, and 17 received psychotropics and lipid-lowering or hypotensive agents. Those in the smaller group were later excluded from follow-up.

At baseline, no significant differences were found between the patients and controls on several metabolic measures, such as cholesterol and apolipoprotein. The patients with bipolar mania had higher uric acid and triglyceride levels, although the latter was not statistically significant. However, compared with the FGF21 serum levels of the controls.

After 4 weeks of taking the antipsychotics, the patients experienced increases in several metabolic measures, such as BMI (23.68 kg/m2 vs. 24.02 kg/m2), LDL cholesterol (2.61 mg/dL vs. 2.98 mg/dL), and glucose (4.74 mg/dL vs. 4.88 mg/dL). However, their FGF21 levels declined, from 279.45 pg/mL to 215.12 pg/mL.

“In light of these findings, our future research will focus on investigating whether ... the change in FGF21 expression is a causal factor or a consequence of bipolar disorder,” the investigators wrote.

They cited several limitations. One is that psychotropic dosages were not discussed, and another is that evaluation data from the Young Mania Rating Scale were missing.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hu Q et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:643-8.

Patients’ fibroblast growth factor–21 levels dropped after 4 weeks of taking antipsychotics

Patients’ fibroblast growth factor–21 levels dropped after 4 weeks of taking antipsychotics

Fibroblast growth factor–21 (FGF21), a protein that regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, could be a biomarker in patients with bipolar mania, a new study suggests.

“In addition, our data indicates that FGF21 may monitor and/or prevent metabolic abnormalities induced by psychotropic drugs,” wrote Qing Hu of Xiamen City Xianyue Hospital, in Fujian, China, and associates. The study was published in Psychiatry Research.

To investigate how the expression of FGF21 changes in response to psychotropics taken by patients with bipolar mania, the researchers recruited 99 inpatients with bipolar mania with or without psychosis and 99 healthy controls. Eighty-two of the patients received psychotropics only, and 17 received psychotropics and lipid-lowering or hypotensive agents. Those in the smaller group were later excluded from follow-up.

At baseline, no significant differences were found between the patients and controls on several metabolic measures, such as cholesterol and apolipoprotein. The patients with bipolar mania had higher uric acid and triglyceride levels, although the latter was not statistically significant. However, compared with the FGF21 serum levels of the controls.

After 4 weeks of taking the antipsychotics, the patients experienced increases in several metabolic measures, such as BMI (23.68 kg/m2 vs. 24.02 kg/m2), LDL cholesterol (2.61 mg/dL vs. 2.98 mg/dL), and glucose (4.74 mg/dL vs. 4.88 mg/dL). However, their FGF21 levels declined, from 279.45 pg/mL to 215.12 pg/mL.

“In light of these findings, our future research will focus on investigating whether ... the change in FGF21 expression is a causal factor or a consequence of bipolar disorder,” the investigators wrote.

They cited several limitations. One is that psychotropic dosages were not discussed, and another is that evaluation data from the Young Mania Rating Scale were missing.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hu Q et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:643-8.

Fibroblast growth factor–21 (FGF21), a protein that regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, could be a biomarker in patients with bipolar mania, a new study suggests.

“In addition, our data indicates that FGF21 may monitor and/or prevent metabolic abnormalities induced by psychotropic drugs,” wrote Qing Hu of Xiamen City Xianyue Hospital, in Fujian, China, and associates. The study was published in Psychiatry Research.

To investigate how the expression of FGF21 changes in response to psychotropics taken by patients with bipolar mania, the researchers recruited 99 inpatients with bipolar mania with or without psychosis and 99 healthy controls. Eighty-two of the patients received psychotropics only, and 17 received psychotropics and lipid-lowering or hypotensive agents. Those in the smaller group were later excluded from follow-up.

At baseline, no significant differences were found between the patients and controls on several metabolic measures, such as cholesterol and apolipoprotein. The patients with bipolar mania had higher uric acid and triglyceride levels, although the latter was not statistically significant. However, compared with the FGF21 serum levels of the controls.

After 4 weeks of taking the antipsychotics, the patients experienced increases in several metabolic measures, such as BMI (23.68 kg/m2 vs. 24.02 kg/m2), LDL cholesterol (2.61 mg/dL vs. 2.98 mg/dL), and glucose (4.74 mg/dL vs. 4.88 mg/dL). However, their FGF21 levels declined, from 279.45 pg/mL to 215.12 pg/mL.

“In light of these findings, our future research will focus on investigating whether ... the change in FGF21 expression is a causal factor or a consequence of bipolar disorder,” the investigators wrote.

They cited several limitations. One is that psychotropic dosages were not discussed, and another is that evaluation data from the Young Mania Rating Scale were missing.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hu Q et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:643-8.

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

Smartphone-based system rivals clinical assessments of anxiety in bipolar disorder

In patients with bipolar disorder currently in partial or full remission, self-reporting of anxiety to a smartphone-based system matched clinical evaluations of anxiety, according to Maria Faurholt-Jepsen, MD, and her associates.

A total of 84 patients with bipolar disorder who participated in the randomized, controlled, single-blind, parallel-group MONARCA II trial were included in the study, reported Dr. Faurholt-Jepsen of Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, and her associates. All patients reported their anxiety to the smartphone-based system every day for a 9-month period; all patients underwent clinical evaluations of anxiety, functioning, patient-reported stress, and quality of life at five fixed time points over the study period. The study was published online by the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Self-reported anxiety was mild, with 19.3% of patients reporting anxiety during the study period, and 2.6% reporting severe anxiety. No association was seen between gender and anxiety days, or between bipolar disorder type and anxiety days. Patients reported depressed mood on 43.2% of the days when anxiety was also reported, and reported mania on 48.0% of the days when anxiety was reported.

Self-reported anxiety scores were positively associated with the anxiety subitems on a key rating scale (P = .0001). In addition, self-reported anxiety was associated with perceived stress, quality of life, and functioning (P = .0001 for all three).

“ Frequent fine-grained monitoring in clinical, high-risk and epidemiological populations provides an opportunity to gain a better understanding of the nature, correlates, and clinical implications of [bipolar disorder],” the investigators wrote.

Three coauthors reported consulting with Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Servier, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, Sunovion, and Medilink. Two coauthors are cofounders and shareholders in Monsenso.

SOURCE: Faurholt-Jepsen M et al. J Affect Disord. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.029.

In patients with bipolar disorder currently in partial or full remission, self-reporting of anxiety to a smartphone-based system matched clinical evaluations of anxiety, according to Maria Faurholt-Jepsen, MD, and her associates.

A total of 84 patients with bipolar disorder who participated in the randomized, controlled, single-blind, parallel-group MONARCA II trial were included in the study, reported Dr. Faurholt-Jepsen of Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, and her associates. All patients reported their anxiety to the smartphone-based system every day for a 9-month period; all patients underwent clinical evaluations of anxiety, functioning, patient-reported stress, and quality of life at five fixed time points over the study period. The study was published online by the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Self-reported anxiety was mild, with 19.3% of patients reporting anxiety during the study period, and 2.6% reporting severe anxiety. No association was seen between gender and anxiety days, or between bipolar disorder type and anxiety days. Patients reported depressed mood on 43.2% of the days when anxiety was also reported, and reported mania on 48.0% of the days when anxiety was reported.

Self-reported anxiety scores were positively associated with the anxiety subitems on a key rating scale (P = .0001). In addition, self-reported anxiety was associated with perceived stress, quality of life, and functioning (P = .0001 for all three).

“ Frequent fine-grained monitoring in clinical, high-risk and epidemiological populations provides an opportunity to gain a better understanding of the nature, correlates, and clinical implications of [bipolar disorder],” the investigators wrote.

Three coauthors reported consulting with Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Servier, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, Sunovion, and Medilink. Two coauthors are cofounders and shareholders in Monsenso.

SOURCE: Faurholt-Jepsen M et al. J Affect Disord. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.029.

In patients with bipolar disorder currently in partial or full remission, self-reporting of anxiety to a smartphone-based system matched clinical evaluations of anxiety, according to Maria Faurholt-Jepsen, MD, and her associates.

A total of 84 patients with bipolar disorder who participated in the randomized, controlled, single-blind, parallel-group MONARCA II trial were included in the study, reported Dr. Faurholt-Jepsen of Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, and her associates. All patients reported their anxiety to the smartphone-based system every day for a 9-month period; all patients underwent clinical evaluations of anxiety, functioning, patient-reported stress, and quality of life at five fixed time points over the study period. The study was published online by the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Self-reported anxiety was mild, with 19.3% of patients reporting anxiety during the study period, and 2.6% reporting severe anxiety. No association was seen between gender and anxiety days, or between bipolar disorder type and anxiety days. Patients reported depressed mood on 43.2% of the days when anxiety was also reported, and reported mania on 48.0% of the days when anxiety was reported.

Self-reported anxiety scores were positively associated with the anxiety subitems on a key rating scale (P = .0001). In addition, self-reported anxiety was associated with perceived stress, quality of life, and functioning (P = .0001 for all three).

“ Frequent fine-grained monitoring in clinical, high-risk and epidemiological populations provides an opportunity to gain a better understanding of the nature, correlates, and clinical implications of [bipolar disorder],” the investigators wrote.

Three coauthors reported consulting with Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Servier, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, Sunovion, and Medilink. Two coauthors are cofounders and shareholders in Monsenso.

SOURCE: Faurholt-Jepsen M et al. J Affect Disord. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.029.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

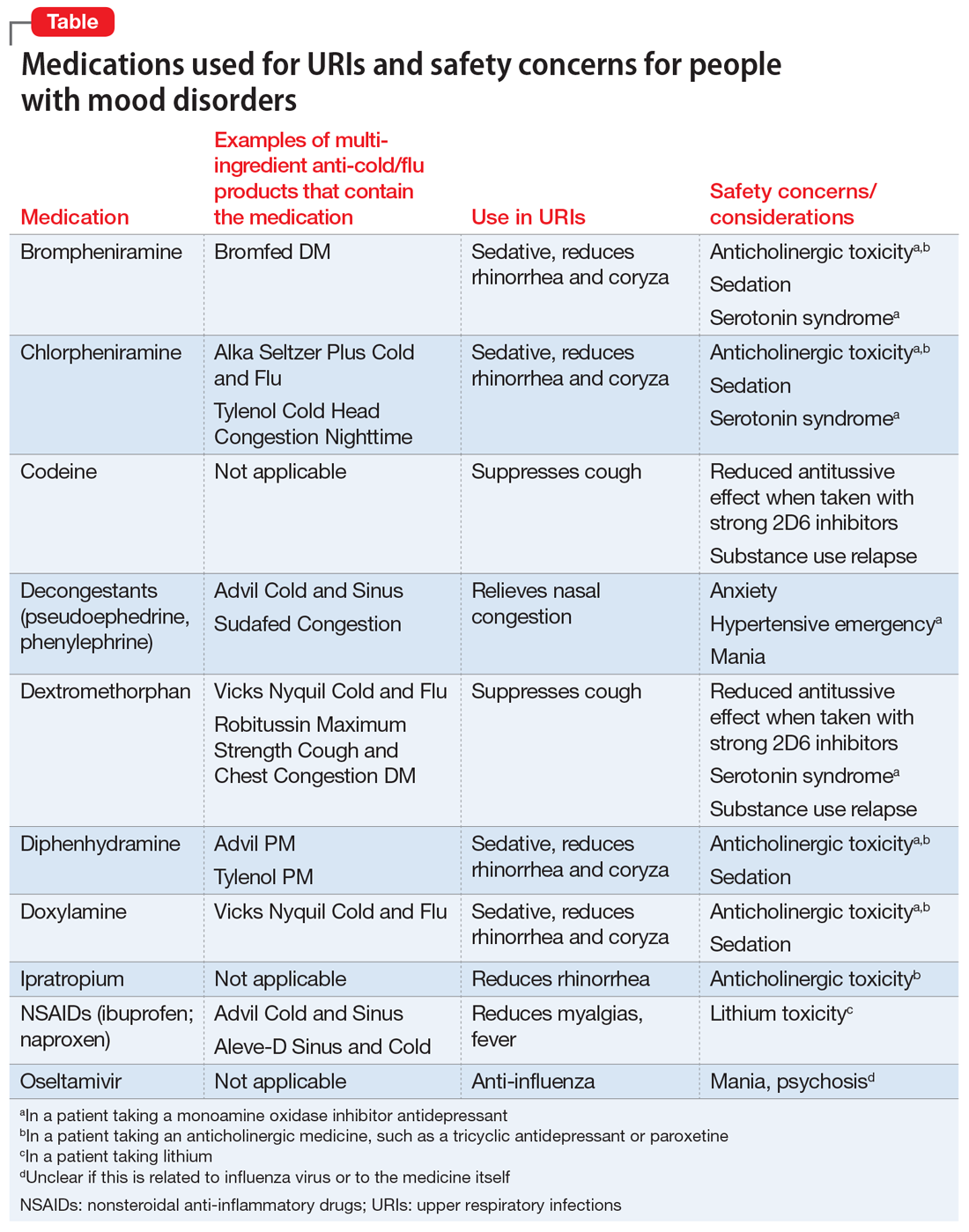

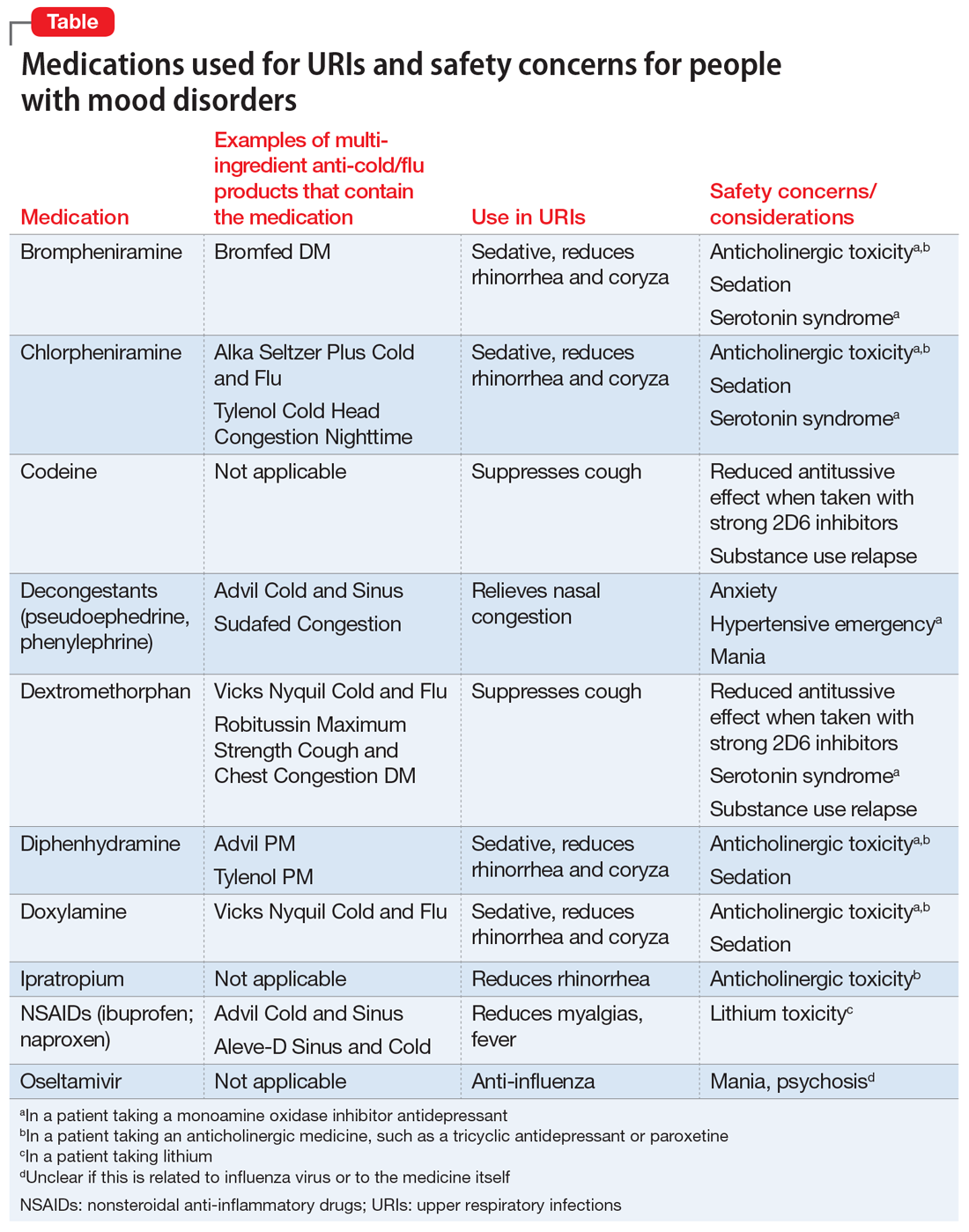

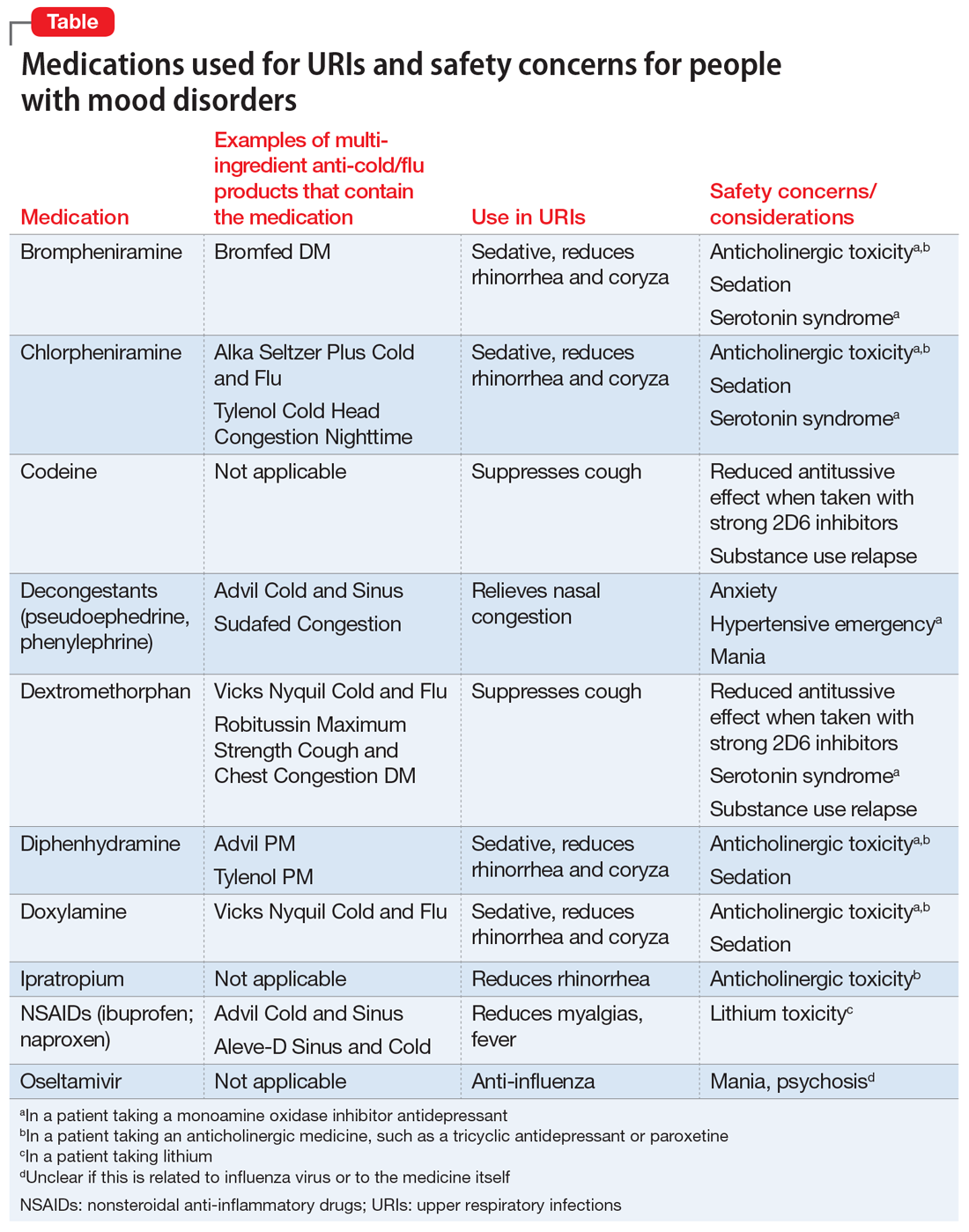

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

Siblings of bipolar disorder patients at higher cardiometabolic disease risk

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia and higher rates of ischemic stroke than do controls, results of a longitudinal cohort study suggest.

, wrote Wen-Yen Tsao, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan, and associates. Previous research has identified several overlapping genes between cardiometabolic diseases and mood disorders. In addition, polymorphisms of several genes tied to obesity have been associated with bipolar disorder.

In the current study, Dr. Tsao and associates analyzed the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes health care data from more than 99% of the Taiwanese population (J Affect Disord. 2019 Jun 15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.094). Adults born before 1990 who had no psychiatric disorders, a sibling with bipolar disorder, and a metabolic disorder were enrolled as the study cohort. A control group was identified randomly. By way of ICD-9-CM codes, people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity were identified in both cohorts. The investigators followed the metabolic status of 7,225 unaffected siblings of bipolar disorder patients and 28,900 controls from 1996 to 2011.

Dr. Tsao and associates found that the family members who had siblings with bipolar disorder had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia (5.4% vs. 4.5%; P = .001), compared with controls. The group with siblings with bipolar disorder also were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at a younger age (34.81 vs. 37.22; P = .024), and had a higher prevalence of any stroke (1.5 vs. 1.1%; P = .007) and ischemic stroke (0.7% vs. 0.4%, P = .001), compared with controls.

A subanalysis showed that the higher risk of any stroke (odds ratio, 1.38; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.85) and ischemic stroke (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.60-3.70) pertained only to male siblings. That gender-specific finding might be attributed to differences in plasma triglyceride clearance between men and women, the researchers wrote.

The findings might not be generalizable to other populations, the investigators noted. In addition, they said, the prevalence of cardiometabolic disease in the groups studied might be underestimated.

“Our results may motivate additional studies to evaluate genetic factors, psychosocial factors, and other pathophysiology of bipolar disorder,” they wrote.

The study was funded by Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology, and Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The researchers cited no conflicts of interest.

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia and higher rates of ischemic stroke than do controls, results of a longitudinal cohort study suggest.

, wrote Wen-Yen Tsao, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan, and associates. Previous research has identified several overlapping genes between cardiometabolic diseases and mood disorders. In addition, polymorphisms of several genes tied to obesity have been associated with bipolar disorder.

In the current study, Dr. Tsao and associates analyzed the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes health care data from more than 99% of the Taiwanese population (J Affect Disord. 2019 Jun 15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.094). Adults born before 1990 who had no psychiatric disorders, a sibling with bipolar disorder, and a metabolic disorder were enrolled as the study cohort. A control group was identified randomly. By way of ICD-9-CM codes, people with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity were identified in both cohorts. The investigators followed the metabolic status of 7,225 unaffected siblings of bipolar disorder patients and 28,900 controls from 1996 to 2011.

Dr. Tsao and associates found that the family members who had siblings with bipolar disorder had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia (5.4% vs. 4.5%; P = .001), compared with controls. The group with siblings with bipolar disorder also were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at a younger age (34.81 vs. 37.22; P = .024), and had a higher prevalence of any stroke (1.5 vs. 1.1%; P = .007) and ischemic stroke (0.7% vs. 0.4%, P = .001), compared with controls.

A subanalysis showed that the higher risk of any stroke (odds ratio, 1.38; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.85) and ischemic stroke (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.60-3.70) pertained only to male siblings. That gender-specific finding might be attributed to differences in plasma triglyceride clearance between men and women, the researchers wrote.

The findings might not be generalizable to other populations, the investigators noted. In addition, they said, the prevalence of cardiometabolic disease in the groups studied might be underestimated.

“Our results may motivate additional studies to evaluate genetic factors, psychosocial factors, and other pathophysiology of bipolar disorder,” they wrote.

The study was funded by Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology, and Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The researchers cited no conflicts of interest.

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia and higher rates of ischemic stroke than do controls, results of a longitudinal cohort study suggest.

, wrote Wen-Yen Tsao, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan, and associates. Previous research has identified several overlapping genes between cardiometabolic diseases and mood disorders. In addition, polymorphisms of several genes tied to obesity have been associated with bipolar disorder.