User login

FDA expands use of Vraylar to treatment of bipolar-associated depressive episodes

The Food and Drug Administration on May 28 approved a supplemental New Drug Application for cariprazine (Vraylar) for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Approval for the expanded label was based on results of the RGH-MD-53, RGH-MD-54, and RGH-MD-56 clinical trials, in which cariprazine was compared with placebo over a 6-week period in patients with bipolar I disorder. In all three trials, patients receiving 1.5 mg cariprazine had significantly greater improvement in their Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating scale after 6 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo.

Cariprazine previously was indicated for the treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults. The most common adverse reactions reported in the clinical trials were nausea, akathisia, restlessness, and extrapyramidal symptoms; these symptoms are similar to those on the Vraylar label.

“Treating bipolar disorder can be very difficult, because people living with the illness experience a range of depressive and manic symptoms, sometimes both at the same time, and , specifically manic, mixed, and depressive episodes, with just one medication,” Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Allergan website.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 28 approved a supplemental New Drug Application for cariprazine (Vraylar) for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Approval for the expanded label was based on results of the RGH-MD-53, RGH-MD-54, and RGH-MD-56 clinical trials, in which cariprazine was compared with placebo over a 6-week period in patients with bipolar I disorder. In all three trials, patients receiving 1.5 mg cariprazine had significantly greater improvement in their Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating scale after 6 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo.

Cariprazine previously was indicated for the treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults. The most common adverse reactions reported in the clinical trials were nausea, akathisia, restlessness, and extrapyramidal symptoms; these symptoms are similar to those on the Vraylar label.

“Treating bipolar disorder can be very difficult, because people living with the illness experience a range of depressive and manic symptoms, sometimes both at the same time, and , specifically manic, mixed, and depressive episodes, with just one medication,” Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Allergan website.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 28 approved a supplemental New Drug Application for cariprazine (Vraylar) for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Approval for the expanded label was based on results of the RGH-MD-53, RGH-MD-54, and RGH-MD-56 clinical trials, in which cariprazine was compared with placebo over a 6-week period in patients with bipolar I disorder. In all three trials, patients receiving 1.5 mg cariprazine had significantly greater improvement in their Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating scale after 6 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo.

Cariprazine previously was indicated for the treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults. The most common adverse reactions reported in the clinical trials were nausea, akathisia, restlessness, and extrapyramidal symptoms; these symptoms are similar to those on the Vraylar label.

“Treating bipolar disorder can be very difficult, because people living with the illness experience a range of depressive and manic symptoms, sometimes both at the same time, and , specifically manic, mixed, and depressive episodes, with just one medication,” Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Allergan website.

Bipolar disorder during pregnancy: Lessons learned

Careful management of bipolar disorder during pregnancy is critical because for so many patients with this illness, the road to emotional well-being has been a long one, requiring a combination of careful pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies.

Half of referrals to our Center for Women’s Mental Health – where we evaluate and treat women before, during, and after pregnancy – are for women who have histories of bipolar disorder. My colleagues and I are asked at continuing medical education programs what we “always do” and “never do” with respect to the treatment of these patients.

What about discontinuation of mood stabilizers during pregnancy and risk of relapse?

We never abruptly stop mood stabilizers if a patient has an unplanned pregnancy – a common scenario, with 50% of pregnancies across the country being unplanned across sociodemographic lines – save for sodium valproate, which is a clearly a documented teratogen; it increases risk for organ malformation and behavioral difficulties in exposed offspring. In our center, we typically view the use of sodium valproate in reproductive age women as contraindicated.

One may then question the circumstances under which lithium might be used during pregnancy, because many clinicians are faced with patients who have been exquisite responders to lithium. Such a patient may present with a history of mania, but there are obvious concerns given the historical literature, and even some more recent reports, that describe an increased risk of teratogenicity with fetal exposure to lithium.

not only to decrease the risk of relapse following discontinuation of mood stabilizers, but because recurrence of illness during pregnancy for these patients is a very strong predictor of risk for postpartum depression. Women with bipolar disorder already are at a fivefold increased risk for postpartum depression, so discussion of sustaining euthymia during pregnancy for bipolar women is particularly timely given the focus nationally on treatment and prevention of postpartum depression.

In patients with history of mania, what about stopping treatment with lithium and other effective treatments during pregnancy?

Historically, we sometimes divided patients with bipolar disorder into those with “more severe recurrent disease” compared with those with more distant, circumscribed disease. In patients with more remote histories of mood dysregulation, we tended to discontinue treatment with mood stabilizers such as lithium or even newer second-generation atypical antipsychotics to see if patients could at least get through earlier stages of pregnancy before going back on anti-manic treatment.

Our experience now over several decades has revealed that this can be a risky clinical move. What we see is that even in patients with histories of mania years in the past (i.e., a circumscribed episode of mania during college in a woman now 35 years old with intervening sustained well-being), discontinuation of treatment that got patients well can lead to recurrence. Hence, we should not confuse an exquisite response to treatment with long periods of well-being as suggesting that the patient has a less severe form of bipolar disorder and hence the capacity to sustain that well-being when treatment is removed.

What about increasing/decreasing lithium dose during pregnancy and around time of delivery?

Select patients may be sensitive to changes in plasma levels of lithium, but the literature suggests that the clinical utility of arbitrarily sustaining plasma levels at the upper limit of the accepted range may be of only modest advantage, if any. With this as a backdrop and even while knowing that increased plasma volume of pregnancy is associated with a fall in plasma level of most medications, we do not arbitrarily increase the dose of lithium across pregnancy merely to sustain a level in the absence of a change in clinical symptoms. Indeed, to my knowledge, currently available data supporting a clear correlation of decline in plasma levels and frank change in symptoms during pregnancy are very sparse, if existent.

Earlier work had suggested that lithium dosage should be reduced proximate to delivery, a period characterized by rapid shifts in plasma volume during the acute peripartum period. Because physicians in our center do not alter lithium dose across pregnancy, we never reduce the dose of lithium proximate to delivery because of a theoretical concern for increased risk of either neonatal toxicity or maternal lithium toxicity, which is essentially nonexistent in terms of systematic reports in the literature.

Obvious concerns about lithium during pregnancy have focused on increased risk of teratogenesis, with the earliest reports supporting an increased risk of Epstein’s anomaly (0.05%-0.1%). More recent reports suggest an increased risk of cardiovascular malformations, which according to some investigators may be dose dependent.

For those patients who are exquisitely responsive to lithium, we typically leave them on the medicine and avail ourselves of current fetal echocardiographic evaluation at 16 weeks to 18 weeks to document the integrity of the fetal cardiac anatomy. Although the risk for cardiac malformations associated with lithium exposure during the first trimester is still exceedingly small, it is still extremely reassuring to patients to know that they are safely on the other side of a teratogenic window.

What about lamotrigine levels across pregnancy?

The last decade has seen a dramatic decrease in the administration of lithium to women with bipolar disorder, and growing use of both lamotrigine and second-generation atypical antipsychotics (frequently in combination) as an alternative. The changes in plasma level of lamotrigine across pregnancy are being increasingly well documented based on rigorous studies (Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018 Sep;45[3]:403-17).

These are welcome data, but the correlation between plasma concentration of lamotrigine and clinical response is a poor one. To date, there are sparse data to suggest that maintaining plasma levels of lithium or lamotrigine at a certain level during pregnancy changes clinical outcome. Following lamotrigine plasma levels during pregnancy seems more like an academic exercise than a procedure associated with particular clinical value.

As in the case of lithium, we never change lamotrigine doses proximate to pregnancy because of the absence of reports of neonatal toxicity associated with using lamotrigine during the peripartum period. The rationale for removing or minimizing the use of an effective medicine proximate to delivery, a period of risk for bipolar women, is lacking.

In 2019, we clearly are seeing a growing use of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar disorder during pregnancy frequently coadministered with medicines such as lamotrigine as opposed to lithium. The accumulated data to date on second-generation atypical antipsychotics are not definitive, but increasingly are reassuring in terms of absence of a clear signal for teratogenicity; hence, our comfort in using this class of medicines is only growing, which is important given the prevalence of use of these agents in reproductive-age women.

If there is a single critical guiding principle for the clinician when it comes to managing bipolar women during pregnancy and the postpartum period, it is sustaining euthymia. With the recent focus of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force on prevention of postpartum depression, nothing is more helpful perhaps than keeping women with bipolar disorder well, both proximate to pregnancy and during an actual pregnancy. Keeping those patients well maximizes the likelihood that they will proceed across the peripartum and into the postpartum period with a level of emotional well-being that optimizes and maximizes positive long-term outcomes for both patients and families.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Careful management of bipolar disorder during pregnancy is critical because for so many patients with this illness, the road to emotional well-being has been a long one, requiring a combination of careful pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies.

Half of referrals to our Center for Women’s Mental Health – where we evaluate and treat women before, during, and after pregnancy – are for women who have histories of bipolar disorder. My colleagues and I are asked at continuing medical education programs what we “always do” and “never do” with respect to the treatment of these patients.

What about discontinuation of mood stabilizers during pregnancy and risk of relapse?

We never abruptly stop mood stabilizers if a patient has an unplanned pregnancy – a common scenario, with 50% of pregnancies across the country being unplanned across sociodemographic lines – save for sodium valproate, which is a clearly a documented teratogen; it increases risk for organ malformation and behavioral difficulties in exposed offspring. In our center, we typically view the use of sodium valproate in reproductive age women as contraindicated.

One may then question the circumstances under which lithium might be used during pregnancy, because many clinicians are faced with patients who have been exquisite responders to lithium. Such a patient may present with a history of mania, but there are obvious concerns given the historical literature, and even some more recent reports, that describe an increased risk of teratogenicity with fetal exposure to lithium.

not only to decrease the risk of relapse following discontinuation of mood stabilizers, but because recurrence of illness during pregnancy for these patients is a very strong predictor of risk for postpartum depression. Women with bipolar disorder already are at a fivefold increased risk for postpartum depression, so discussion of sustaining euthymia during pregnancy for bipolar women is particularly timely given the focus nationally on treatment and prevention of postpartum depression.

In patients with history of mania, what about stopping treatment with lithium and other effective treatments during pregnancy?

Historically, we sometimes divided patients with bipolar disorder into those with “more severe recurrent disease” compared with those with more distant, circumscribed disease. In patients with more remote histories of mood dysregulation, we tended to discontinue treatment with mood stabilizers such as lithium or even newer second-generation atypical antipsychotics to see if patients could at least get through earlier stages of pregnancy before going back on anti-manic treatment.

Our experience now over several decades has revealed that this can be a risky clinical move. What we see is that even in patients with histories of mania years in the past (i.e., a circumscribed episode of mania during college in a woman now 35 years old with intervening sustained well-being), discontinuation of treatment that got patients well can lead to recurrence. Hence, we should not confuse an exquisite response to treatment with long periods of well-being as suggesting that the patient has a less severe form of bipolar disorder and hence the capacity to sustain that well-being when treatment is removed.

What about increasing/decreasing lithium dose during pregnancy and around time of delivery?

Select patients may be sensitive to changes in plasma levels of lithium, but the literature suggests that the clinical utility of arbitrarily sustaining plasma levels at the upper limit of the accepted range may be of only modest advantage, if any. With this as a backdrop and even while knowing that increased plasma volume of pregnancy is associated with a fall in plasma level of most medications, we do not arbitrarily increase the dose of lithium across pregnancy merely to sustain a level in the absence of a change in clinical symptoms. Indeed, to my knowledge, currently available data supporting a clear correlation of decline in plasma levels and frank change in symptoms during pregnancy are very sparse, if existent.

Earlier work had suggested that lithium dosage should be reduced proximate to delivery, a period characterized by rapid shifts in plasma volume during the acute peripartum period. Because physicians in our center do not alter lithium dose across pregnancy, we never reduce the dose of lithium proximate to delivery because of a theoretical concern for increased risk of either neonatal toxicity or maternal lithium toxicity, which is essentially nonexistent in terms of systematic reports in the literature.

Obvious concerns about lithium during pregnancy have focused on increased risk of teratogenesis, with the earliest reports supporting an increased risk of Epstein’s anomaly (0.05%-0.1%). More recent reports suggest an increased risk of cardiovascular malformations, which according to some investigators may be dose dependent.

For those patients who are exquisitely responsive to lithium, we typically leave them on the medicine and avail ourselves of current fetal echocardiographic evaluation at 16 weeks to 18 weeks to document the integrity of the fetal cardiac anatomy. Although the risk for cardiac malformations associated with lithium exposure during the first trimester is still exceedingly small, it is still extremely reassuring to patients to know that they are safely on the other side of a teratogenic window.

What about lamotrigine levels across pregnancy?

The last decade has seen a dramatic decrease in the administration of lithium to women with bipolar disorder, and growing use of both lamotrigine and second-generation atypical antipsychotics (frequently in combination) as an alternative. The changes in plasma level of lamotrigine across pregnancy are being increasingly well documented based on rigorous studies (Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018 Sep;45[3]:403-17).

These are welcome data, but the correlation between plasma concentration of lamotrigine and clinical response is a poor one. To date, there are sparse data to suggest that maintaining plasma levels of lithium or lamotrigine at a certain level during pregnancy changes clinical outcome. Following lamotrigine plasma levels during pregnancy seems more like an academic exercise than a procedure associated with particular clinical value.

As in the case of lithium, we never change lamotrigine doses proximate to pregnancy because of the absence of reports of neonatal toxicity associated with using lamotrigine during the peripartum period. The rationale for removing or minimizing the use of an effective medicine proximate to delivery, a period of risk for bipolar women, is lacking.

In 2019, we clearly are seeing a growing use of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar disorder during pregnancy frequently coadministered with medicines such as lamotrigine as opposed to lithium. The accumulated data to date on second-generation atypical antipsychotics are not definitive, but increasingly are reassuring in terms of absence of a clear signal for teratogenicity; hence, our comfort in using this class of medicines is only growing, which is important given the prevalence of use of these agents in reproductive-age women.

If there is a single critical guiding principle for the clinician when it comes to managing bipolar women during pregnancy and the postpartum period, it is sustaining euthymia. With the recent focus of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force on prevention of postpartum depression, nothing is more helpful perhaps than keeping women with bipolar disorder well, both proximate to pregnancy and during an actual pregnancy. Keeping those patients well maximizes the likelihood that they will proceed across the peripartum and into the postpartum period with a level of emotional well-being that optimizes and maximizes positive long-term outcomes for both patients and families.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Careful management of bipolar disorder during pregnancy is critical because for so many patients with this illness, the road to emotional well-being has been a long one, requiring a combination of careful pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies.

Half of referrals to our Center for Women’s Mental Health – where we evaluate and treat women before, during, and after pregnancy – are for women who have histories of bipolar disorder. My colleagues and I are asked at continuing medical education programs what we “always do” and “never do” with respect to the treatment of these patients.

What about discontinuation of mood stabilizers during pregnancy and risk of relapse?

We never abruptly stop mood stabilizers if a patient has an unplanned pregnancy – a common scenario, with 50% of pregnancies across the country being unplanned across sociodemographic lines – save for sodium valproate, which is a clearly a documented teratogen; it increases risk for organ malformation and behavioral difficulties in exposed offspring. In our center, we typically view the use of sodium valproate in reproductive age women as contraindicated.

One may then question the circumstances under which lithium might be used during pregnancy, because many clinicians are faced with patients who have been exquisite responders to lithium. Such a patient may present with a history of mania, but there are obvious concerns given the historical literature, and even some more recent reports, that describe an increased risk of teratogenicity with fetal exposure to lithium.

not only to decrease the risk of relapse following discontinuation of mood stabilizers, but because recurrence of illness during pregnancy for these patients is a very strong predictor of risk for postpartum depression. Women with bipolar disorder already are at a fivefold increased risk for postpartum depression, so discussion of sustaining euthymia during pregnancy for bipolar women is particularly timely given the focus nationally on treatment and prevention of postpartum depression.

In patients with history of mania, what about stopping treatment with lithium and other effective treatments during pregnancy?

Historically, we sometimes divided patients with bipolar disorder into those with “more severe recurrent disease” compared with those with more distant, circumscribed disease. In patients with more remote histories of mood dysregulation, we tended to discontinue treatment with mood stabilizers such as lithium or even newer second-generation atypical antipsychotics to see if patients could at least get through earlier stages of pregnancy before going back on anti-manic treatment.

Our experience now over several decades has revealed that this can be a risky clinical move. What we see is that even in patients with histories of mania years in the past (i.e., a circumscribed episode of mania during college in a woman now 35 years old with intervening sustained well-being), discontinuation of treatment that got patients well can lead to recurrence. Hence, we should not confuse an exquisite response to treatment with long periods of well-being as suggesting that the patient has a less severe form of bipolar disorder and hence the capacity to sustain that well-being when treatment is removed.

What about increasing/decreasing lithium dose during pregnancy and around time of delivery?

Select patients may be sensitive to changes in plasma levels of lithium, but the literature suggests that the clinical utility of arbitrarily sustaining plasma levels at the upper limit of the accepted range may be of only modest advantage, if any. With this as a backdrop and even while knowing that increased plasma volume of pregnancy is associated with a fall in plasma level of most medications, we do not arbitrarily increase the dose of lithium across pregnancy merely to sustain a level in the absence of a change in clinical symptoms. Indeed, to my knowledge, currently available data supporting a clear correlation of decline in plasma levels and frank change in symptoms during pregnancy are very sparse, if existent.

Earlier work had suggested that lithium dosage should be reduced proximate to delivery, a period characterized by rapid shifts in plasma volume during the acute peripartum period. Because physicians in our center do not alter lithium dose across pregnancy, we never reduce the dose of lithium proximate to delivery because of a theoretical concern for increased risk of either neonatal toxicity or maternal lithium toxicity, which is essentially nonexistent in terms of systematic reports in the literature.

Obvious concerns about lithium during pregnancy have focused on increased risk of teratogenesis, with the earliest reports supporting an increased risk of Epstein’s anomaly (0.05%-0.1%). More recent reports suggest an increased risk of cardiovascular malformations, which according to some investigators may be dose dependent.

For those patients who are exquisitely responsive to lithium, we typically leave them on the medicine and avail ourselves of current fetal echocardiographic evaluation at 16 weeks to 18 weeks to document the integrity of the fetal cardiac anatomy. Although the risk for cardiac malformations associated with lithium exposure during the first trimester is still exceedingly small, it is still extremely reassuring to patients to know that they are safely on the other side of a teratogenic window.

What about lamotrigine levels across pregnancy?

The last decade has seen a dramatic decrease in the administration of lithium to women with bipolar disorder, and growing use of both lamotrigine and second-generation atypical antipsychotics (frequently in combination) as an alternative. The changes in plasma level of lamotrigine across pregnancy are being increasingly well documented based on rigorous studies (Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018 Sep;45[3]:403-17).

These are welcome data, but the correlation between plasma concentration of lamotrigine and clinical response is a poor one. To date, there are sparse data to suggest that maintaining plasma levels of lithium or lamotrigine at a certain level during pregnancy changes clinical outcome. Following lamotrigine plasma levels during pregnancy seems more like an academic exercise than a procedure associated with particular clinical value.

As in the case of lithium, we never change lamotrigine doses proximate to pregnancy because of the absence of reports of neonatal toxicity associated with using lamotrigine during the peripartum period. The rationale for removing or minimizing the use of an effective medicine proximate to delivery, a period of risk for bipolar women, is lacking.

In 2019, we clearly are seeing a growing use of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar disorder during pregnancy frequently coadministered with medicines such as lamotrigine as opposed to lithium. The accumulated data to date on second-generation atypical antipsychotics are not definitive, but increasingly are reassuring in terms of absence of a clear signal for teratogenicity; hence, our comfort in using this class of medicines is only growing, which is important given the prevalence of use of these agents in reproductive-age women.

If there is a single critical guiding principle for the clinician when it comes to managing bipolar women during pregnancy and the postpartum period, it is sustaining euthymia. With the recent focus of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force on prevention of postpartum depression, nothing is more helpful perhaps than keeping women with bipolar disorder well, both proximate to pregnancy and during an actual pregnancy. Keeping those patients well maximizes the likelihood that they will proceed across the peripartum and into the postpartum period with a level of emotional well-being that optimizes and maximizes positive long-term outcomes for both patients and families.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Racing thoughts: What to consider

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

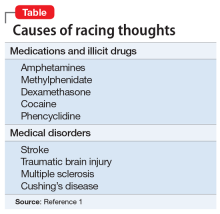

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

Young, angry, and in need of a liver transplant

CASE Rash, fever, extreme lethargy; multiple hospital visits

Ms. L, age 21, a single woman with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), is directly admitted from an outside community hospital to our tertiary care academic hospital with acute liver failure.

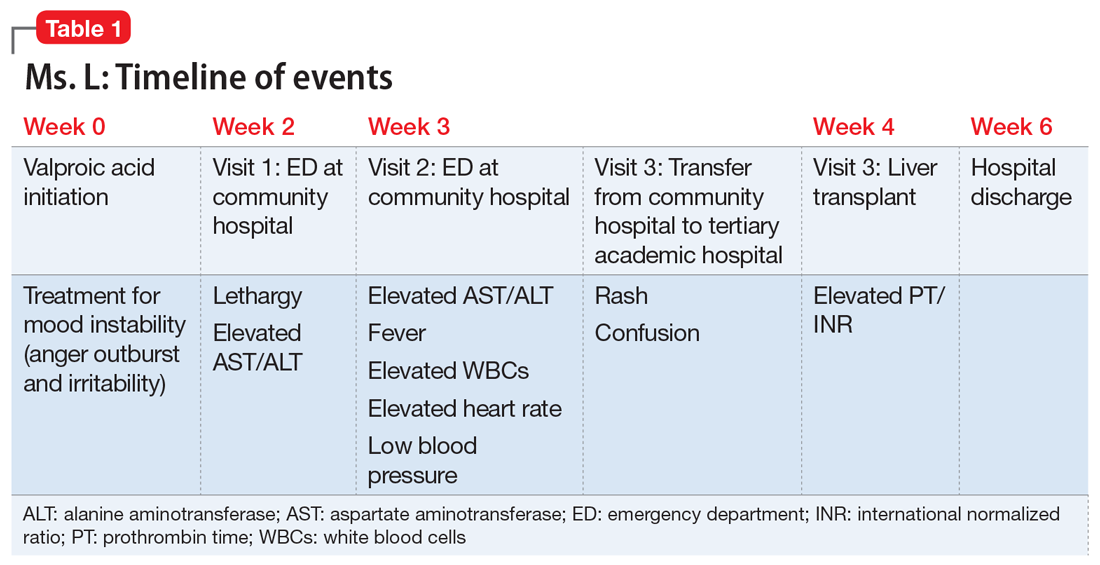

One month earlier, Ms. L had an argument with her family and punched a wall, fracturing her hand. Following the episode, Ms. L’s primary care physician (PCP) prescribed valproic acid, 500 mg/d, to address “mood swings,” which included angry outbursts and irritability. According to her PCP, no baseline laboratory tests were ordered for Ms. L when she started valproic acid because she was young and otherwise healthy.

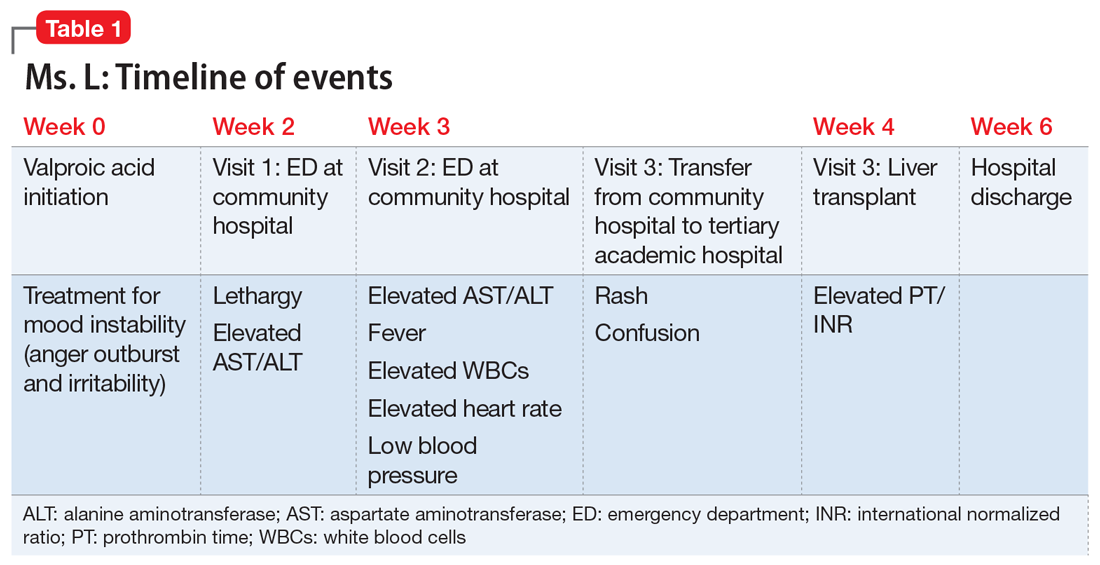

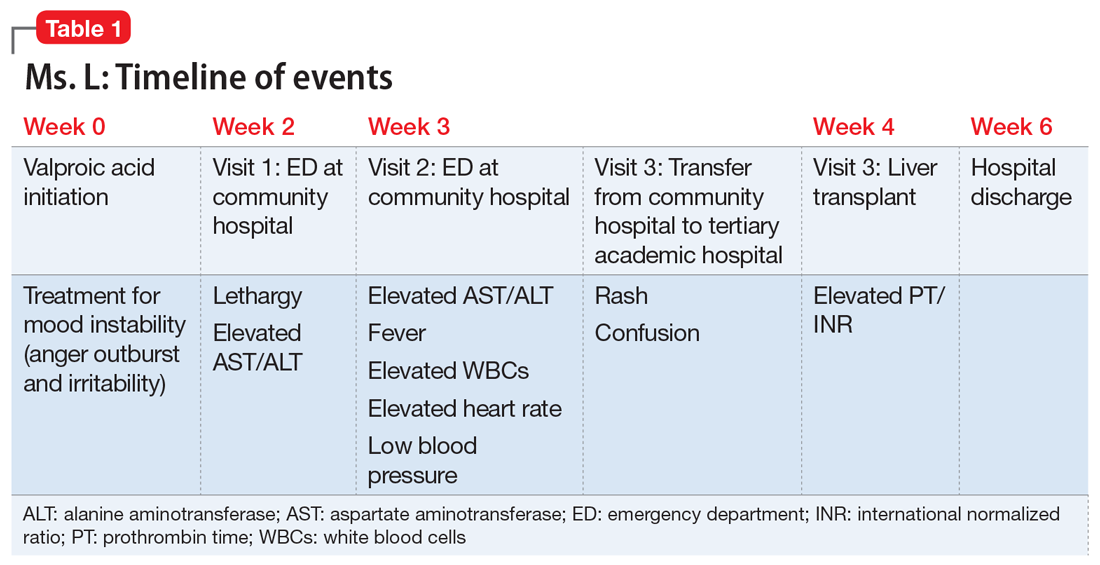

After Ms. L had been taking valproic acid for approximately 2 weeks, her mother noticed she became extremely lethargic and took her to the emergency department (ED) of a community hospital (Visit 1) (Table 1). At this time, her laboratory results were notable for an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 303 IU/L (reference range: 8 to 40 IU/L) and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 241 IU/L (reference range: 20 to 60 IU/L). She also underwent a liver ultrasound, urine toxicology screen, blood alcohol level, and acetaminophen level; the results of all of these tests were unremarkable. Her valproic acid level was within therapeutic limits, consistent with patient adherence; her ammonia level was within normal limits. At Visit 1, Ms. L’s transaminitis was presumed to be secondary to valproic acid. The ED clinicians told her to stop taking valproic acid and discharged her. Her PCP did not give her any follow-up instructions for further laboratory tests or any other recommendations.

During the next week, even though she stopped taking the valproic acid as instructed, Ms. L developed a rash and fever, and continued to have lethargy and general malaise. When she returned to the ED (Visit 2) (Table 1), she was febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive, with an elevated white blood cell count, eosinophilia, low platelets, and elevated liver function tests. At Visit 2, she was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Ms. L insisted that she had not overdosed on any medications, or used illicit drugs or alcohol. A test for hepatitis C was negative. Her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L (reference range: 11 to 32 µmol/L). Ms. L received N-acetylcysteine (NAC), prednisone, diphenhydramine, famotidine, and ibuprofen before she was transferred to our tertiary care hospital.

When she arrives at our facility (Visit 3) (Table 1), Ms. L is admitted with acute liver failure. She has an ALT level of 4,091 IU/L, and an AST level of 2,049 IU/L. Ms. L’s mother says that her daughter had been taking sertraline for depression for “some time” with no adverse effects, although she is not clear on the dose or frequency. Her mother says that Ms. L generally likes to spend most of her time at home, and does not believe her daughter is a danger to herself or others. Ms. L’s mother could not describe any episodes of mania or recurrent, dangerous anger episodes. Ms. L has no other medical history and has otherwise been healthy.

On hospital Day 2, Ms. L’s ammonia level is 72 µmol/L, which is slightly elevated. The hepatology team confirms that Ms. L may require a liver transplantation. The primary team consults the inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison (C-L) team for a pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation.

[polldaddy:10307646]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for Ms. L was broad and included both accidental and intentional medication overdose. The primary team consulted the inpatient psychiatry C-L team not only for a pre-transplant evaluation, but also to assess for possible overdose.

Continue to: A review of the records...

A review of the records from Visit 1 and Visit 2 at the outside hospital found no acetaminophen in Ms. L’s system and verified that there was no evidence of a current valproic acid overdose. Ms. L had stated that she had not overdosed on any other medications or used any illicit drugs or alcohol. Ms. L’s complex symptoms—namely fever, acute liver failure, and rash—were more consistent with an adverse effect of valproic acid or possibly an inherent autoimmune process.

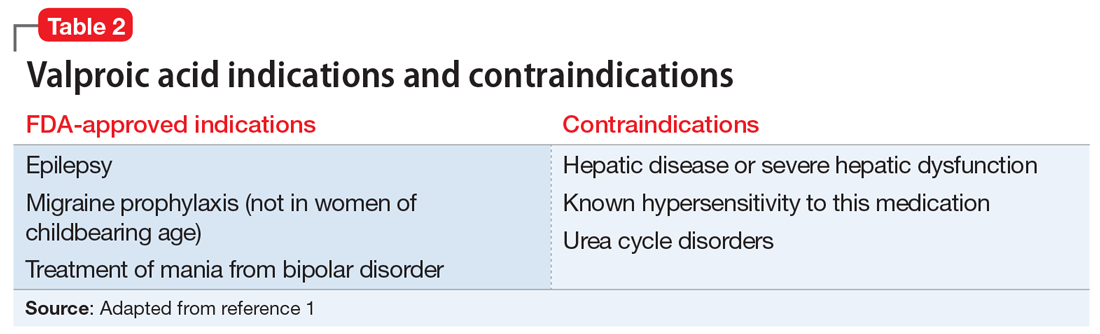

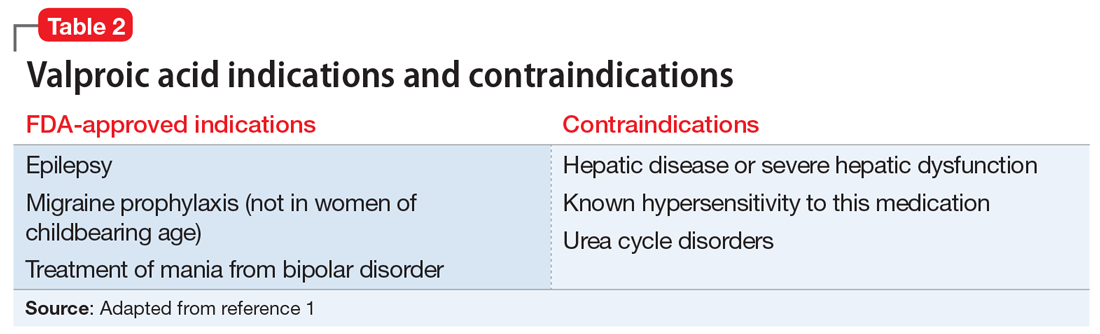

Liver damage from valproic acid

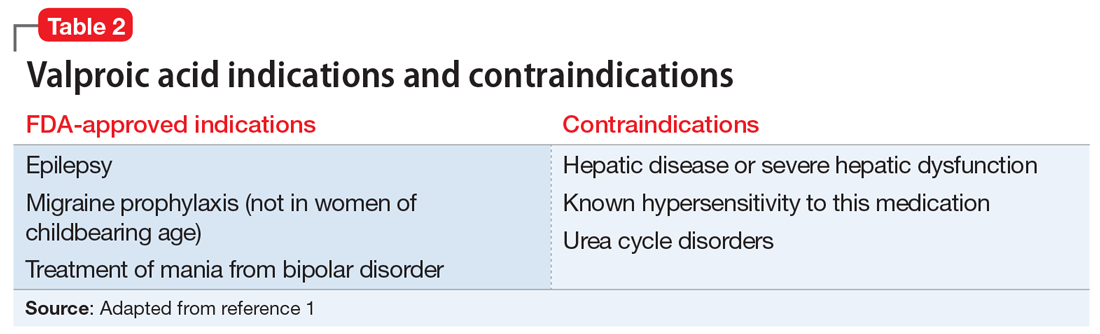

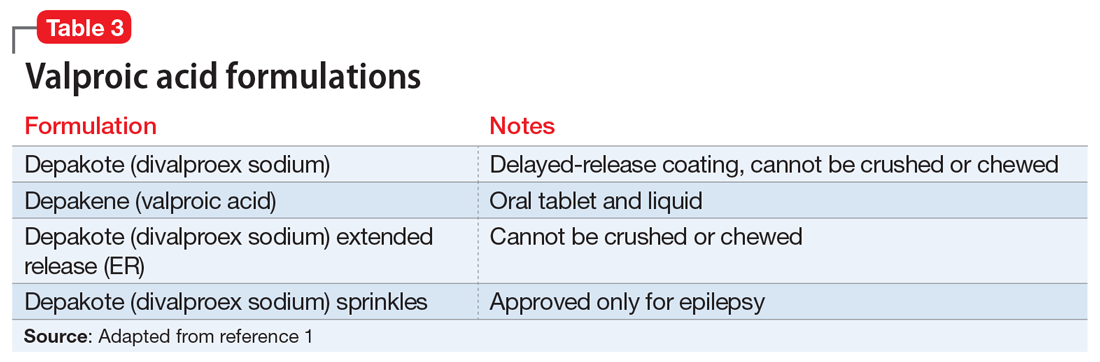

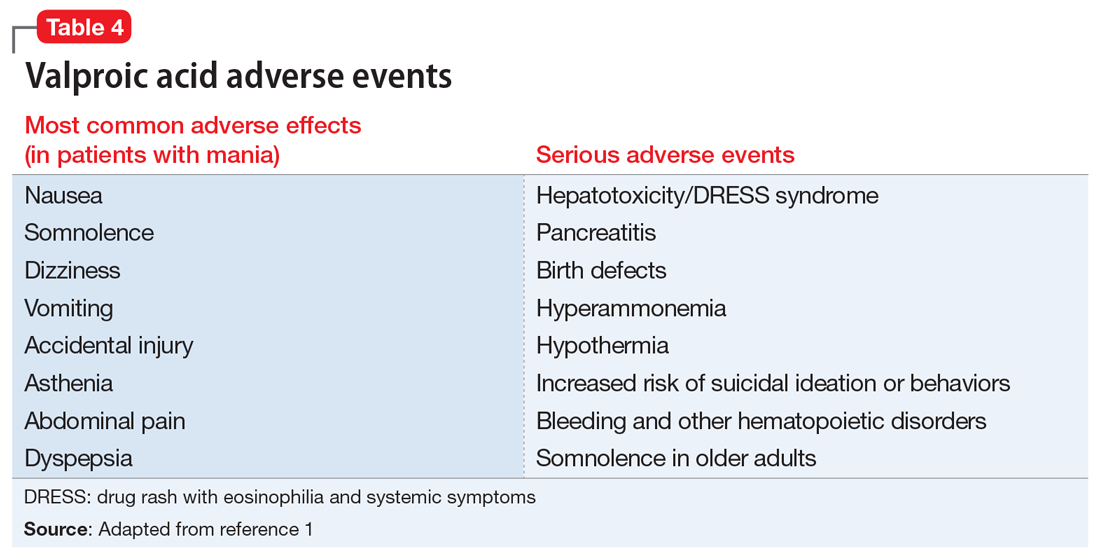

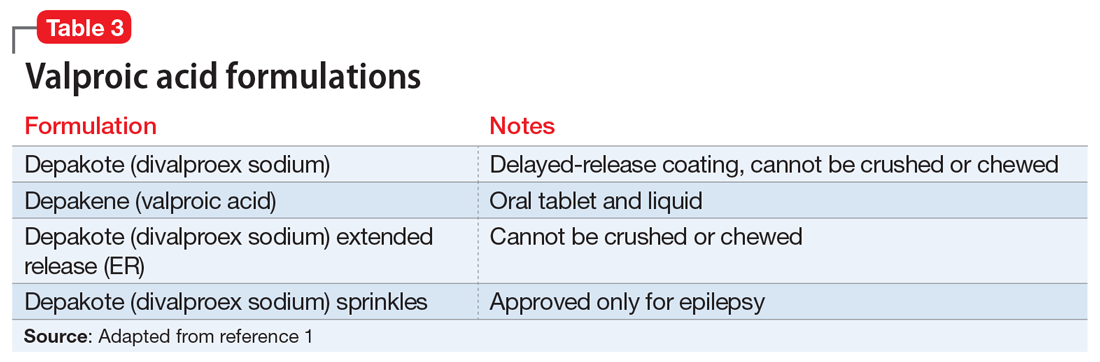

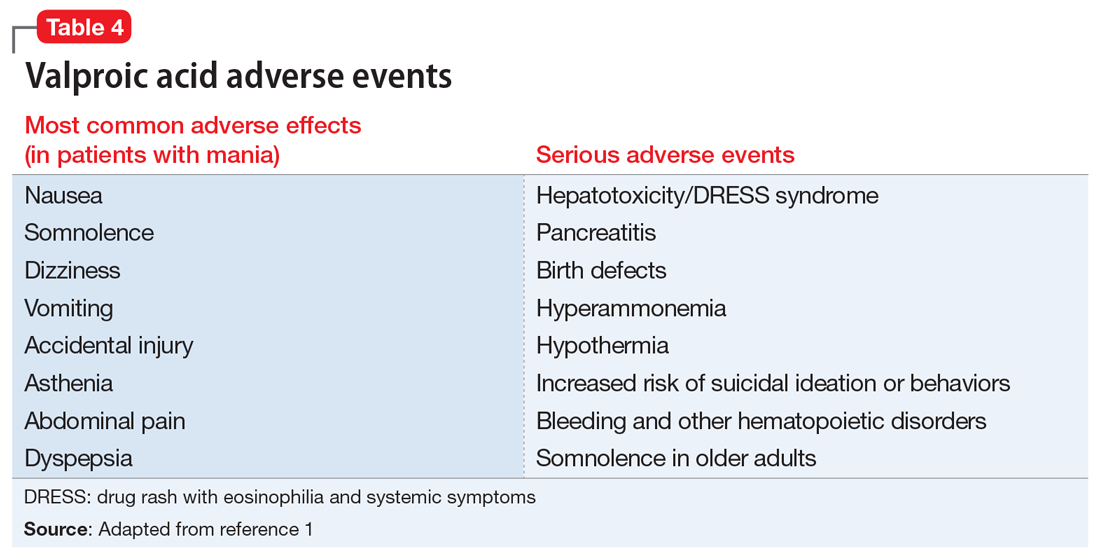

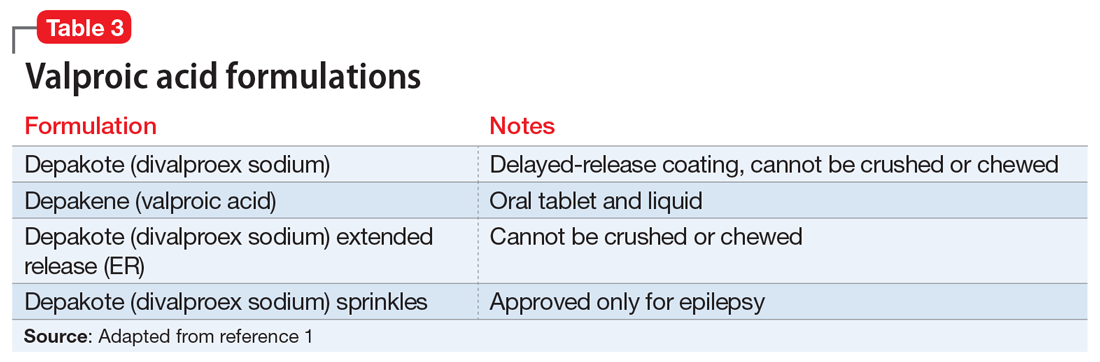

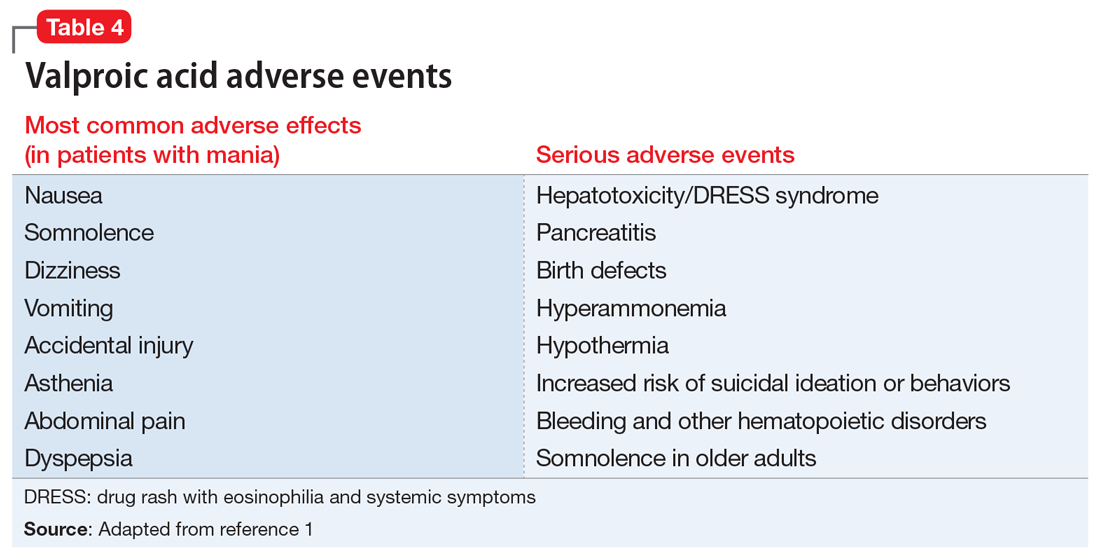

Valproic acid is FDA-approved for treating bipolar disorder, epilepsy, and migraine headaches1 (Table 21). Common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, and dry mouth. Rarely, valproic acid can impair liver function. While receiving valproic acid, 5% to 10% of patients develop elevated ALT levels, but most are asymptomatic and resolve with time, even if the patient continues taking valproic acid.2 Valproic acid hepatotoxicity resulting in liver transplantation for a healthy patient is extremely rare (Table 31). Liver failure, both fatal and non-fatal, is more prevalent in patients concurrently taking other medications, such as antiepileptics, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics, as compared with patients receiving only valproic acid.3

There are 3 clinically distinguishable forms of hepatotoxicity due to valproic acid2:

- hyperammonemia

- acute liver failure and jaundice

- Myriad ProReye-like syndrome, which is generally seen in children.

In case reports of hyperammonemia due to valproic acid, previously healthy patients experience confusion, lethargy, and eventual coma in the context of elevated serum ammonia levels; these symptoms resolved upon discontinuing valproic acid.4,5 Liver function remained normal, with normal to near-normal liver enzymes and bilirubin.3 Hyperammonemia and resulting encephalopathy generally occurred within 1 to 3 weeks after initiation of valproate therapy, with resolution of hyperammonemia and resulting symptoms within a few days after stopping valproic acid.2-4

At Visit 2, Ms. L’s presentation was not initially consistent with hepatic encephalopathy. She was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Additionally, Ms. L’s presenting problem was elevated liver function tests, not elevated ammonia levels. At Visit 2, her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L; on Day 2 (Visit 3) of her hospital stay, her ammonia level was 72 µmol/L (slightly elevated).

Continue to: At Visit 2 in the ED...

At Visit 2 in the ED, Ms. L was started on NAC because the team suspected she was experiencing drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by extensive rash, fever, and involvement of at least 1 internal organ. It is a variation of a drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Ms. L’s unremarkable valproic acid levels combined with the psychiatry assessment ruled out valproic hepatotoxicity due to overdose, either intentional or accidental.

In case reports, patients who developed acute liver failure due to valproic acid typically had a hepatitis-like syndrome consisting of moderate elevation in liver enzymes, jaundice, and liver failure necessitating transplantation after at least 1 month of treatment with valproic acid.2 In addition to the typical hepatitis-like syndrome resulting from valproic acid, case reports have also linked treatment with valproic acid to DRESS syndrome.2 This syndrome is known to occur with anticonvulsants such as phenobarbital, lamotrigine, and phenytoin, but there are only a few reported cases of DRESS syndrome due to valproic acid therapy alone.6 Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome differs from other acute liver failure cases in that patients also develop lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.2,6,7 Patients with DRESS syndrome typically respond to corticosteroid therapy and discontinuation of valproic acid, and the liver damage resolves after several weeks, without a need for transplantation.2,6,7

Ms. L seemed to have similarities to DRESS syndrome. However, the severity of her liver damage, which might require transplantation even after only 2 weeks of valproic acid therapy, initially led the hepatology and C-L teams to consider her presentation similar to severe hepatitis-like cases.

EVALUATION Consent for transplantation

As an inpatient, Ms. L undergoes further laboratory testing. Her hepatic function panel demonstrates a total protein level of 4.8 g/dL, an albumin level of 2.0 g/dL, total bilirubin level of 12.2 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase of 166 IU/L. Her laboratory results indicate a prothrombin time (PT) of 77.4 seconds, partial thromboplastin time of 61.5 seconds, and PT international normalized ratio (INR) of 9.6. Ms. L’s basic metabolic panel is within normal limits except for a blood urea nitrogen level of 6 mg/dL, glucose level of 136 mg/dL, and calcium level of 7.0 mg/dL. Her complete blood count indicates a white blood cell count of 12.1, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, hematocrit of 30.4%, mean corpuscular volume of 85.9 fL, and platelet count of 84. Her lipase level is normal at 49 U/L. Her serum acetaminophen concentration is <3.0 mcg/mL, valproic acid level was <2 µg/mL, and she is negative for hepatitis A, B, and C. A urine toxicology screen and testing for herpes simplex, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus are all negative. Results from several auto-antibodies tests are negative and within normal limits, except filamentous actin (F-actin) antibody, which is slightly higher than normal at 21.4 ELISA units. Based on these results, Ms. L’s liver failure seemed most likely secondary to a reaction to valproic acid.

During her pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation, Ms. L is found to be a poor historian with minimal speech production, flat affect, and clouded sensorium. She denies overdosing on her prescribed valproic acid or sertraline, reports no current suicidal ideation, and does not want to die. She accurately recalls her correct daily dosing of each medication, and verifies that she stopped taking valproic acid 2 weeks ago after being advised to do so by the ED clinicians at Visit 2. She continued to take sertraline until Visit 2. She denied any past or present episodes consistent with mania, which was consistent with her mother’s report.

Continue to: Ms. L becomes agitated...

Ms. L becomes agitated upon further questioning, and requests immediate discharge so that she can return to her family. The evaluation is postponed briefly.

When they reconvene, the C-L team performs a decision-making capacity evaluation, which reveals that Ms. L’s mood and affect are consistent with fear of her impending liver transplant and being alone and approximately 2 hours from her family. This is likely complicated by delirium due to hepatotoxicity. Further discussion between Ms. L and the multidisciplinary team focuses on the risks, benefits, adverse effects of, and alternatives to her current treatment; the possibility of needing a liver transplantation; and how to help her family with transportation to the hospital. Following the discussion, Ms. L is fully cooperative with further treatment, and the pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation is completed.

On physical examination, Ms. L is noted to have a widespread morbilliform rash covering 50% to 60% of her body.

[polldaddy:10307651]

The authors’ observations

L-carnitine supplementation

Multiple studies have shown that supplementation with L-carnitine may increase survival from severe hepatotoxicity due to valproic acid.8,9 Valproic acid may contribute to carnitine deficiency due to its inhibition of carnitine biosynthesis via a decrease in alpha-ketoglutarate concentration.8 Hepatotoxicity or hyperammonemia due to valproic acid may be potentiated by a carnitine deficiency, either pre-existing or resulting from valproic acid.8 L-carnitine supplementation has hastened the decrease of valproic acid–induced ammonemia in a dose-dependent manner,10 and it is currently recommended in cases of valproic acid toxicity, especially in children.8 Children at high risk for developing carnitine deficiency who need to receive valproic acid can be given carnitine supplementation.11 It is not known whether L-carnitine is clinically effective in protecting the liver or hastening liver recovery,8 but it is believed that it might prevent adverse effects of hepatotoxicity and hyperammonemia, especially in patients who receive long-term valproic acid therapy.12

TREATMENT Decompensation and transplantation

Ms. L’s treatment regimen includes NAC, lactulose, and L-carnitine supplementation. During the course of Ms. L’s hospital stay, her liver enzymes begin to trend downward, but her INR and PT remain elevated.

Continue to: On hospital Day 6...

On hospital Day 6, she develops more severe symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, with significant altered mental status and inattention. Ms. L is transferred to the ICU, intubated, and placed on the liver transplant list.

On hospital Day 9, she undergoes a liver transplantation.

[polldaddy:10307652]

The authors’ observations

Baseline laboratory testing should have been conducted prior to initiating valproic acid. As Ms. L’s symptoms worsened, better communication with her PCP and closer monitoring after starting valproic acid might have resulted in more immediate care. Early recognition of her symptoms and decompensation may have triggered earlier inpatient admission and/or transfer to a tertiary care facility for observation and treatment. Additionally, repeat laboratory testing and instructions on when to return to the ED should have been provided at Visit 1.

This case demonstrates the need for all clinicians who prescribe valproic acid to remain diligent about the accurate diagnosis of mood and behavioral symptoms, knowing when psychotropic medications are indicated, and carefully considering and discussing even rare, potentially life-threatening adverse effects of all medications with patients.

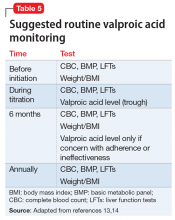

Although rare, after starting valproic acid, a patient may experience a rapid decompensation and life-threatening illness. Ideally, clinicians should closely monitor patients after initiating valproic acid (Table 41). Clinicians must have a clear knowledge of the recommended monitoring and indications for hospitalization and treatment when they note adverse effects such as elevated liver enzymes or transaminitis (Table 513,14). Even after stopping valproic acid, patients who have experienced adverse events should be closely monitored to ensure complete resolution.

Continue to: Consider patient-specific factors

Consider patient-specific factors

Consider the mental state, intellectual capacity, and social support of each patient before initiating valproic acid. Its use as a mood stabilizer for “mood swings” outside of the context of bipolar disorder is questionable. Valproic acid is FDA-approved for treating bipolar disorder and seizures, but not for anger outbursts/irritability. Prior to starting valproic acid, Ms. L may have benefited from alternative nonpharmacologic treatments, such as psychotherapy, for her anger outbursts and poor coping skills. Therapeutic techniques that focused on helping her acquire better coping mechanisms may have been useful, especially because her mood symptoms did not meet criteria for bipolar disorder, and her depression had long been controlled with sertraline monotherapy.

OUTCOME Discharged after 20 days

Ms. L stays in the hospital for 10 days after receiving her liver transplant. She has low appetite and some difficulty with sleep after the transplant; therefore, the C-L team recommends mirtazapine, 15 mg/d. She has no behavioral problems during her stay, and is set up with home health, case management, and psychiatry follow-up. On hospital Day 20, she is discharged.

Bottom Line

Use caution when prescribing valproic acid, even in young, otherwise healthy patients. Although rare, some patients may experience a rapid decompensation and life-threatening illness after starting valproic acid. When prescribing valproic acid, ensure close follow-up after initiation, including mental status examinations, physical examinations, and laboratory testing.

Related Resource

- Doroudgar S, Chou TI. How to modify psychotropic therapy for patients who have liver dysfunction. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(12):46-49.

Drug Brand Names

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

Famotidine • Fluxid, Pepcid

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Mirtazapine • Remeron

N-acetylcysteine • Mucomyst

Phenobarbital • Luminal

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Prednisone • Cortan, Deltasone

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

1. Depakote [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie, Inc.; 2019.

2. National Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug Record: Valproate. https://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Valproate.htm. Updated October 30, 2018. Accessed March 21, 2019.

3. Schmid MM, Freudenmann RW, Keller F, et al. Non-fatal and fatal liver failure associated with valproic acid. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46(2):63-68.

4. Patel N, Landry KB, Fargason RE, et al. Reversible encephalopathy due to valproic acid induced hyperammonemia in a patient with Bipolar I disorder: a cautionary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(1):40-44.

5. Eze E, Workman M, Donley B. Hyperammonemia and coma developed by a woman treated with valproic acid for affective disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(10):1358-1359.

6. Darban M and Bagheri B. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms induced by valproic acid: a case report. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(9): e35825.

7. van Zoelen MA, de Graaf M, van Dijk MR, et al. Valproic acid-induced DRESS syndrome with acute liver failure. Neth J Med. 2012;70(3):155.

8. Lheureux PE, Hantson P. Carnitine in the treatment of valproic acid-induced toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009;47(2):101-111.

9. Bohan TP, Helton E, McDonald I, et al. Effect of L-carnitine treatment for valproate-induced hepatotoxicity. Neurology. 2001;56(10):1405-1409.

10. Böhles H, Sewell AC, Wenzel D. The effect of carnitine supplementation in valproate-induced hyperammonaemia. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85(4):446-449.

11. Raskind JY, El-Chaar GM. The role of carnitine supplementation during valproic acid therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(5):630-638.

12. Romero-Falcón A, de la Santa-Belda E, García-Contreras R, et al. A case of valproate-associated hepatotoxicity treated with L-carnitine. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14(5):338-340.

13. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder: the management of bipolar disorder in adults, children, and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185. Updated April 2018. Accessed March 21, 2019.

14 . Hirschfeld RMA, Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with biopolar disorder: second edition. American Psychiatric Association. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.pdf. Published 2002. Accessed March 21, 2019.

CASE Rash, fever, extreme lethargy; multiple hospital visits

Ms. L, age 21, a single woman with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), is directly admitted from an outside community hospital to our tertiary care academic hospital with acute liver failure.

One month earlier, Ms. L had an argument with her family and punched a wall, fracturing her hand. Following the episode, Ms. L’s primary care physician (PCP) prescribed valproic acid, 500 mg/d, to address “mood swings,” which included angry outbursts and irritability. According to her PCP, no baseline laboratory tests were ordered for Ms. L when she started valproic acid because she was young and otherwise healthy.

After Ms. L had been taking valproic acid for approximately 2 weeks, her mother noticed she became extremely lethargic and took her to the emergency department (ED) of a community hospital (Visit 1) (Table 1). At this time, her laboratory results were notable for an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 303 IU/L (reference range: 8 to 40 IU/L) and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 241 IU/L (reference range: 20 to 60 IU/L). She also underwent a liver ultrasound, urine toxicology screen, blood alcohol level, and acetaminophen level; the results of all of these tests were unremarkable. Her valproic acid level was within therapeutic limits, consistent with patient adherence; her ammonia level was within normal limits. At Visit 1, Ms. L’s transaminitis was presumed to be secondary to valproic acid. The ED clinicians told her to stop taking valproic acid and discharged her. Her PCP did not give her any follow-up instructions for further laboratory tests or any other recommendations.

During the next week, even though she stopped taking the valproic acid as instructed, Ms. L developed a rash and fever, and continued to have lethargy and general malaise. When she returned to the ED (Visit 2) (Table 1), she was febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive, with an elevated white blood cell count, eosinophilia, low platelets, and elevated liver function tests. At Visit 2, she was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Ms. L insisted that she had not overdosed on any medications, or used illicit drugs or alcohol. A test for hepatitis C was negative. Her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L (reference range: 11 to 32 µmol/L). Ms. L received N-acetylcysteine (NAC), prednisone, diphenhydramine, famotidine, and ibuprofen before she was transferred to our tertiary care hospital.

When she arrives at our facility (Visit 3) (Table 1), Ms. L is admitted with acute liver failure. She has an ALT level of 4,091 IU/L, and an AST level of 2,049 IU/L. Ms. L’s mother says that her daughter had been taking sertraline for depression for “some time” with no adverse effects, although she is not clear on the dose or frequency. Her mother says that Ms. L generally likes to spend most of her time at home, and does not believe her daughter is a danger to herself or others. Ms. L’s mother could not describe any episodes of mania or recurrent, dangerous anger episodes. Ms. L has no other medical history and has otherwise been healthy.

On hospital Day 2, Ms. L’s ammonia level is 72 µmol/L, which is slightly elevated. The hepatology team confirms that Ms. L may require a liver transplantation. The primary team consults the inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison (C-L) team for a pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation.

[polldaddy:10307646]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for Ms. L was broad and included both accidental and intentional medication overdose. The primary team consulted the inpatient psychiatry C-L team not only for a pre-transplant evaluation, but also to assess for possible overdose.

Continue to: A review of the records...

A review of the records from Visit 1 and Visit 2 at the outside hospital found no acetaminophen in Ms. L’s system and verified that there was no evidence of a current valproic acid overdose. Ms. L had stated that she had not overdosed on any other medications or used any illicit drugs or alcohol. Ms. L’s complex symptoms—namely fever, acute liver failure, and rash—were more consistent with an adverse effect of valproic acid or possibly an inherent autoimmune process.

Liver damage from valproic acid

Valproic acid is FDA-approved for treating bipolar disorder, epilepsy, and migraine headaches1 (Table 21). Common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, and dry mouth. Rarely, valproic acid can impair liver function. While receiving valproic acid, 5% to 10% of patients develop elevated ALT levels, but most are asymptomatic and resolve with time, even if the patient continues taking valproic acid.2 Valproic acid hepatotoxicity resulting in liver transplantation for a healthy patient is extremely rare (Table 31). Liver failure, both fatal and non-fatal, is more prevalent in patients concurrently taking other medications, such as antiepileptics, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics, as compared with patients receiving only valproic acid.3

There are 3 clinically distinguishable forms of hepatotoxicity due to valproic acid2:

- hyperammonemia

- acute liver failure and jaundice

- Myriad ProReye-like syndrome, which is generally seen in children.

In case reports of hyperammonemia due to valproic acid, previously healthy patients experience confusion, lethargy, and eventual coma in the context of elevated serum ammonia levels; these symptoms resolved upon discontinuing valproic acid.4,5 Liver function remained normal, with normal to near-normal liver enzymes and bilirubin.3 Hyperammonemia and resulting encephalopathy generally occurred within 1 to 3 weeks after initiation of valproate therapy, with resolution of hyperammonemia and resulting symptoms within a few days after stopping valproic acid.2-4

At Visit 2, Ms. L’s presentation was not initially consistent with hepatic encephalopathy. She was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Additionally, Ms. L’s presenting problem was elevated liver function tests, not elevated ammonia levels. At Visit 2, her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L; on Day 2 (Visit 3) of her hospital stay, her ammonia level was 72 µmol/L (slightly elevated).

Continue to: At Visit 2 in the ED...

At Visit 2 in the ED, Ms. L was started on NAC because the team suspected she was experiencing drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by extensive rash, fever, and involvement of at least 1 internal organ. It is a variation of a drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Ms. L’s unremarkable valproic acid levels combined with the psychiatry assessment ruled out valproic hepatotoxicity due to overdose, either intentional or accidental.

In case reports, patients who developed acute liver failure due to valproic acid typically had a hepatitis-like syndrome consisting of moderate elevation in liver enzymes, jaundice, and liver failure necessitating transplantation after at least 1 month of treatment with valproic acid.2 In addition to the typical hepatitis-like syndrome resulting from valproic acid, case reports have also linked treatment with valproic acid to DRESS syndrome.2 This syndrome is known to occur with anticonvulsants such as phenobarbital, lamotrigine, and phenytoin, but there are only a few reported cases of DRESS syndrome due to valproic acid therapy alone.6 Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome differs from other acute liver failure cases in that patients also develop lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.2,6,7 Patients with DRESS syndrome typically respond to corticosteroid therapy and discontinuation of valproic acid, and the liver damage resolves after several weeks, without a need for transplantation.2,6,7

Ms. L seemed to have similarities to DRESS syndrome. However, the severity of her liver damage, which might require transplantation even after only 2 weeks of valproic acid therapy, initially led the hepatology and C-L teams to consider her presentation similar to severe hepatitis-like cases.

EVALUATION Consent for transplantation

As an inpatient, Ms. L undergoes further laboratory testing. Her hepatic function panel demonstrates a total protein level of 4.8 g/dL, an albumin level of 2.0 g/dL, total bilirubin level of 12.2 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase of 166 IU/L. Her laboratory results indicate a prothrombin time (PT) of 77.4 seconds, partial thromboplastin time of 61.5 seconds, and PT international normalized ratio (INR) of 9.6. Ms. L’s basic metabolic panel is within normal limits except for a blood urea nitrogen level of 6 mg/dL, glucose level of 136 mg/dL, and calcium level of 7.0 mg/dL. Her complete blood count indicates a white blood cell count of 12.1, hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL, hematocrit of 30.4%, mean corpuscular volume of 85.9 fL, and platelet count of 84. Her lipase level is normal at 49 U/L. Her serum acetaminophen concentration is <3.0 mcg/mL, valproic acid level was <2 µg/mL, and she is negative for hepatitis A, B, and C. A urine toxicology screen and testing for herpes simplex, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus are all negative. Results from several auto-antibodies tests are negative and within normal limits, except filamentous actin (F-actin) antibody, which is slightly higher than normal at 21.4 ELISA units. Based on these results, Ms. L’s liver failure seemed most likely secondary to a reaction to valproic acid.

During her pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation, Ms. L is found to be a poor historian with minimal speech production, flat affect, and clouded sensorium. She denies overdosing on her prescribed valproic acid or sertraline, reports no current suicidal ideation, and does not want to die. She accurately recalls her correct daily dosing of each medication, and verifies that she stopped taking valproic acid 2 weeks ago after being advised to do so by the ED clinicians at Visit 2. She continued to take sertraline until Visit 2. She denied any past or present episodes consistent with mania, which was consistent with her mother’s report.

Continue to: Ms. L becomes agitated...

Ms. L becomes agitated upon further questioning, and requests immediate discharge so that she can return to her family. The evaluation is postponed briefly.

When they reconvene, the C-L team performs a decision-making capacity evaluation, which reveals that Ms. L’s mood and affect are consistent with fear of her impending liver transplant and being alone and approximately 2 hours from her family. This is likely complicated by delirium due to hepatotoxicity. Further discussion between Ms. L and the multidisciplinary team focuses on the risks, benefits, adverse effects of, and alternatives to her current treatment; the possibility of needing a liver transplantation; and how to help her family with transportation to the hospital. Following the discussion, Ms. L is fully cooperative with further treatment, and the pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation is completed.

On physical examination, Ms. L is noted to have a widespread morbilliform rash covering 50% to 60% of her body.

[polldaddy:10307651]

The authors’ observations

L-carnitine supplementation

Multiple studies have shown that supplementation with L-carnitine may increase survival from severe hepatotoxicity due to valproic acid.8,9 Valproic acid may contribute to carnitine deficiency due to its inhibition of carnitine biosynthesis via a decrease in alpha-ketoglutarate concentration.8 Hepatotoxicity or hyperammonemia due to valproic acid may be potentiated by a carnitine deficiency, either pre-existing or resulting from valproic acid.8 L-carnitine supplementation has hastened the decrease of valproic acid–induced ammonemia in a dose-dependent manner,10 and it is currently recommended in cases of valproic acid toxicity, especially in children.8 Children at high risk for developing carnitine deficiency who need to receive valproic acid can be given carnitine supplementation.11 It is not known whether L-carnitine is clinically effective in protecting the liver or hastening liver recovery,8 but it is believed that it might prevent adverse effects of hepatotoxicity and hyperammonemia, especially in patients who receive long-term valproic acid therapy.12

TREATMENT Decompensation and transplantation

Ms. L’s treatment regimen includes NAC, lactulose, and L-carnitine supplementation. During the course of Ms. L’s hospital stay, her liver enzymes begin to trend downward, but her INR and PT remain elevated.

Continue to: On hospital Day 6...

On hospital Day 6, she develops more severe symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, with significant altered mental status and inattention. Ms. L is transferred to the ICU, intubated, and placed on the liver transplant list.

On hospital Day 9, she undergoes a liver transplantation.

[polldaddy:10307652]

The authors’ observations

Baseline laboratory testing should have been conducted prior to initiating valproic acid. As Ms. L’s symptoms worsened, better communication with her PCP and closer monitoring after starting valproic acid might have resulted in more immediate care. Early recognition of her symptoms and decompensation may have triggered earlier inpatient admission and/or transfer to a tertiary care facility for observation and treatment. Additionally, repeat laboratory testing and instructions on when to return to the ED should have been provided at Visit 1.

This case demonstrates the need for all clinicians who prescribe valproic acid to remain diligent about the accurate diagnosis of mood and behavioral symptoms, knowing when psychotropic medications are indicated, and carefully considering and discussing even rare, potentially life-threatening adverse effects of all medications with patients.

Although rare, after starting valproic acid, a patient may experience a rapid decompensation and life-threatening illness. Ideally, clinicians should closely monitor patients after initiating valproic acid (Table 41). Clinicians must have a clear knowledge of the recommended monitoring and indications for hospitalization and treatment when they note adverse effects such as elevated liver enzymes or transaminitis (Table 513,14). Even after stopping valproic acid, patients who have experienced adverse events should be closely monitored to ensure complete resolution.

Continue to: Consider patient-specific factors

Consider patient-specific factors

Consider the mental state, intellectual capacity, and social support of each patient before initiating valproic acid. Its use as a mood stabilizer for “mood swings” outside of the context of bipolar disorder is questionable. Valproic acid is FDA-approved for treating bipolar disorder and seizures, but not for anger outbursts/irritability. Prior to starting valproic acid, Ms. L may have benefited from alternative nonpharmacologic treatments, such as psychotherapy, for her anger outbursts and poor coping skills. Therapeutic techniques that focused on helping her acquire better coping mechanisms may have been useful, especially because her mood symptoms did not meet criteria for bipolar disorder, and her depression had long been controlled with sertraline monotherapy.

OUTCOME Discharged after 20 days

Ms. L stays in the hospital for 10 days after receiving her liver transplant. She has low appetite and some difficulty with sleep after the transplant; therefore, the C-L team recommends mirtazapine, 15 mg/d. She has no behavioral problems during her stay, and is set up with home health, case management, and psychiatry follow-up. On hospital Day 20, she is discharged.

Bottom Line

Use caution when prescribing valproic acid, even in young, otherwise healthy patients. Although rare, some patients may experience a rapid decompensation and life-threatening illness after starting valproic acid. When prescribing valproic acid, ensure close follow-up after initiation, including mental status examinations, physical examinations, and laboratory testing.

Related Resource

- Doroudgar S, Chou TI. How to modify psychotropic therapy for patients who have liver dysfunction. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(12):46-49.

Drug Brand Names

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl

Famotidine • Fluxid, Pepcid

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Mirtazapine • Remeron

N-acetylcysteine • Mucomyst

Phenobarbital • Luminal

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Prednisone • Cortan, Deltasone

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

CASE Rash, fever, extreme lethargy; multiple hospital visits

Ms. L, age 21, a single woman with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), is directly admitted from an outside community hospital to our tertiary care academic hospital with acute liver failure.

One month earlier, Ms. L had an argument with her family and punched a wall, fracturing her hand. Following the episode, Ms. L’s primary care physician (PCP) prescribed valproic acid, 500 mg/d, to address “mood swings,” which included angry outbursts and irritability. According to her PCP, no baseline laboratory tests were ordered for Ms. L when she started valproic acid because she was young and otherwise healthy.

After Ms. L had been taking valproic acid for approximately 2 weeks, her mother noticed she became extremely lethargic and took her to the emergency department (ED) of a community hospital (Visit 1) (Table 1). At this time, her laboratory results were notable for an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 303 IU/L (reference range: 8 to 40 IU/L) and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 241 IU/L (reference range: 20 to 60 IU/L). She also underwent a liver ultrasound, urine toxicology screen, blood alcohol level, and acetaminophen level; the results of all of these tests were unremarkable. Her valproic acid level was within therapeutic limits, consistent with patient adherence; her ammonia level was within normal limits. At Visit 1, Ms. L’s transaminitis was presumed to be secondary to valproic acid. The ED clinicians told her to stop taking valproic acid and discharged her. Her PCP did not give her any follow-up instructions for further laboratory tests or any other recommendations.

During the next week, even though she stopped taking the valproic acid as instructed, Ms. L developed a rash and fever, and continued to have lethargy and general malaise. When she returned to the ED (Visit 2) (Table 1), she was febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive, with an elevated white blood cell count, eosinophilia, low platelets, and elevated liver function tests. At Visit 2, she was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation. Ms. L insisted that she had not overdosed on any medications, or used illicit drugs or alcohol. A test for hepatitis C was negative. Her ammonia level was 58 µmol/L (reference range: 11 to 32 µmol/L). Ms. L received N-acetylcysteine (NAC), prednisone, diphenhydramine, famotidine, and ibuprofen before she was transferred to our tertiary care hospital.

When she arrives at our facility (Visit 3) (Table 1), Ms. L is admitted with acute liver failure. She has an ALT level of 4,091 IU/L, and an AST level of 2,049 IU/L. Ms. L’s mother says that her daughter had been taking sertraline for depression for “some time” with no adverse effects, although she is not clear on the dose or frequency. Her mother says that Ms. L generally likes to spend most of her time at home, and does not believe her daughter is a danger to herself or others. Ms. L’s mother could not describe any episodes of mania or recurrent, dangerous anger episodes. Ms. L has no other medical history and has otherwise been healthy.

On hospital Day 2, Ms. L’s ammonia level is 72 µmol/L, which is slightly elevated. The hepatology team confirms that Ms. L may require a liver transplantation. The primary team consults the inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison (C-L) team for a pre-transplant psychiatric evaluation.

[polldaddy:10307646]

The authors’ observations

The differential diagnosis for Ms. L was broad and included both accidental and intentional medication overdose. The primary team consulted the inpatient psychiatry C-L team not only for a pre-transplant evaluation, but also to assess for possible overdose.

Continue to: A review of the records...

A review of the records from Visit 1 and Visit 2 at the outside hospital found no acetaminophen in Ms. L’s system and verified that there was no evidence of a current valproic acid overdose. Ms. L had stated that she had not overdosed on any other medications or used any illicit drugs or alcohol. Ms. L’s complex symptoms—namely fever, acute liver failure, and rash—were more consistent with an adverse effect of valproic acid or possibly an inherent autoimmune process.

Liver damage from valproic acid