User login

Adding checkpoint inhibitors to radiotherapy requires particular caution in this one scenario

Among scenarios where immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) might be combined, particular caution is needed in the setting of brain metastases, according to authors of a recent clinical review.

While evidence to date is mixed, some studies do suggest that adding ICIs to high-dose stereotactic intracranial radiotherapy for brain metastases might increase the risk of treatment-related brain necrosis, the authors said.

By contrast, the balance of evidence suggests ICIs can be safely combined with palliative radiotherapy without site-specific increases in adverse events, they added.

Likewise, in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, ICIs do not appear to increase incidence of grade 3 or greater pneumonitis when given after definitive chemoradiotherapy, in both retrospective and prospective investigations.

Nevertheless, the addition of ICIs to radiotherapy requires careful further study because of the potential for increased type or severity of toxicities, including the immune-related adverse events associated with ICIs, wrote corresponding author Jay S. Loeffler, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues.

“Caution is warranted when combining radiotherapy and ICI, especially with intracranial radiotherapy,” the researchers wrote. Their report is in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology.

Some studies have indicated a higher rate of treatment-associated brain necrosis when ICIs are combined with intracranial radiotherapy, while others have shown no such trend, the authors said.

In one single-institution experience involving 180 patients with brain metastases undergoing stereotactic radiotherapy, incidence of treatment-associated brain necrosis was significantly higher in patients receiving an ICI, with an odds ratio of 2.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.06-5.44; P = .03).

Similarly, a retrospective single institution 480-patient study showed an incidence of treatment-associated brain necrosis of 20% for ICIs plus stereotactic radiotherapy versus 7% for radiotherapy alone (P less than .001), but substantial differences in baseline characteristics between groups limited the strength of the study’s conclusions, according to the researchers.

Increased risk is primarily in the form of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic episodes in some series, the authors noted. A retrospective, 54-patient report showed a rate of treatment-associated brain necrosis of 30% when ICIs were combined with stereotactic radiotherapy, versus 21% for radiotherapy alone (P = .08), but the incidence of symptomatic cases was 15% in both groups, they noted.

“Intriguingly, the findings of several studies have demonstrated an association between [treatment-associated brain necrosis] and improved survival outcomes in patients with melanoma brain metastases that is similar to the independent observations of an analogous relationship between risk of [immune-related adverse events] in general and responsiveness to ICI,” the researchers wrote.

Most of the Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for ICIs are in the metastatic setting, where palliative radiotherapy is frequently important, the authors noted.

In two retrospective studies of patients with metastatic cancers receiving palliative radiotherapy with ICIs, there was a lack of clear association between the irradiated site and specific immune-related adverse events; that lack of association suggests that any toxicities arising from interactions between palliative radiotherapy and ICIs are mainly systemic, rather than local, the authors wrote.

Several retrospective series in advanced-stage melanoma patients have suggested that palliative radiotherapy plus ICIs is safe and does not significantly increase incidence of immune-related adverse events. However, findings from one series showed a correlation between both the ICI and radiotherapy dose given and the incidence of immune-related adverse events.

Prospective studies will be essential to optimize the balance between disease control and risk of morbidity associated with ICIs and radiotherapy combinations, the authors concluded.

The researchers declared no competing interests related to their review article.

SOURCE: Hwang WL, et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug;15(8):477-494.

Among scenarios where immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) might be combined, particular caution is needed in the setting of brain metastases, according to authors of a recent clinical review.

While evidence to date is mixed, some studies do suggest that adding ICIs to high-dose stereotactic intracranial radiotherapy for brain metastases might increase the risk of treatment-related brain necrosis, the authors said.

By contrast, the balance of evidence suggests ICIs can be safely combined with palliative radiotherapy without site-specific increases in adverse events, they added.

Likewise, in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, ICIs do not appear to increase incidence of grade 3 or greater pneumonitis when given after definitive chemoradiotherapy, in both retrospective and prospective investigations.

Nevertheless, the addition of ICIs to radiotherapy requires careful further study because of the potential for increased type or severity of toxicities, including the immune-related adverse events associated with ICIs, wrote corresponding author Jay S. Loeffler, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues.

“Caution is warranted when combining radiotherapy and ICI, especially with intracranial radiotherapy,” the researchers wrote. Their report is in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology.

Some studies have indicated a higher rate of treatment-associated brain necrosis when ICIs are combined with intracranial radiotherapy, while others have shown no such trend, the authors said.

In one single-institution experience involving 180 patients with brain metastases undergoing stereotactic radiotherapy, incidence of treatment-associated brain necrosis was significantly higher in patients receiving an ICI, with an odds ratio of 2.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.06-5.44; P = .03).

Similarly, a retrospective single institution 480-patient study showed an incidence of treatment-associated brain necrosis of 20% for ICIs plus stereotactic radiotherapy versus 7% for radiotherapy alone (P less than .001), but substantial differences in baseline characteristics between groups limited the strength of the study’s conclusions, according to the researchers.

Increased risk is primarily in the form of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic episodes in some series, the authors noted. A retrospective, 54-patient report showed a rate of treatment-associated brain necrosis of 30% when ICIs were combined with stereotactic radiotherapy, versus 21% for radiotherapy alone (P = .08), but the incidence of symptomatic cases was 15% in both groups, they noted.

“Intriguingly, the findings of several studies have demonstrated an association between [treatment-associated brain necrosis] and improved survival outcomes in patients with melanoma brain metastases that is similar to the independent observations of an analogous relationship between risk of [immune-related adverse events] in general and responsiveness to ICI,” the researchers wrote.

Most of the Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for ICIs are in the metastatic setting, where palliative radiotherapy is frequently important, the authors noted.

In two retrospective studies of patients with metastatic cancers receiving palliative radiotherapy with ICIs, there was a lack of clear association between the irradiated site and specific immune-related adverse events; that lack of association suggests that any toxicities arising from interactions between palliative radiotherapy and ICIs are mainly systemic, rather than local, the authors wrote.

Several retrospective series in advanced-stage melanoma patients have suggested that palliative radiotherapy plus ICIs is safe and does not significantly increase incidence of immune-related adverse events. However, findings from one series showed a correlation between both the ICI and radiotherapy dose given and the incidence of immune-related adverse events.

Prospective studies will be essential to optimize the balance between disease control and risk of morbidity associated with ICIs and radiotherapy combinations, the authors concluded.

The researchers declared no competing interests related to their review article.

SOURCE: Hwang WL, et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug;15(8):477-494.

Among scenarios where immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) might be combined, particular caution is needed in the setting of brain metastases, according to authors of a recent clinical review.

While evidence to date is mixed, some studies do suggest that adding ICIs to high-dose stereotactic intracranial radiotherapy for brain metastases might increase the risk of treatment-related brain necrosis, the authors said.

By contrast, the balance of evidence suggests ICIs can be safely combined with palliative radiotherapy without site-specific increases in adverse events, they added.

Likewise, in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, ICIs do not appear to increase incidence of grade 3 or greater pneumonitis when given after definitive chemoradiotherapy, in both retrospective and prospective investigations.

Nevertheless, the addition of ICIs to radiotherapy requires careful further study because of the potential for increased type or severity of toxicities, including the immune-related adverse events associated with ICIs, wrote corresponding author Jay S. Loeffler, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues.

“Caution is warranted when combining radiotherapy and ICI, especially with intracranial radiotherapy,” the researchers wrote. Their report is in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology.

Some studies have indicated a higher rate of treatment-associated brain necrosis when ICIs are combined with intracranial radiotherapy, while others have shown no such trend, the authors said.

In one single-institution experience involving 180 patients with brain metastases undergoing stereotactic radiotherapy, incidence of treatment-associated brain necrosis was significantly higher in patients receiving an ICI, with an odds ratio of 2.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.06-5.44; P = .03).

Similarly, a retrospective single institution 480-patient study showed an incidence of treatment-associated brain necrosis of 20% for ICIs plus stereotactic radiotherapy versus 7% for radiotherapy alone (P less than .001), but substantial differences in baseline characteristics between groups limited the strength of the study’s conclusions, according to the researchers.

Increased risk is primarily in the form of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic episodes in some series, the authors noted. A retrospective, 54-patient report showed a rate of treatment-associated brain necrosis of 30% when ICIs were combined with stereotactic radiotherapy, versus 21% for radiotherapy alone (P = .08), but the incidence of symptomatic cases was 15% in both groups, they noted.

“Intriguingly, the findings of several studies have demonstrated an association between [treatment-associated brain necrosis] and improved survival outcomes in patients with melanoma brain metastases that is similar to the independent observations of an analogous relationship between risk of [immune-related adverse events] in general and responsiveness to ICI,” the researchers wrote.

Most of the Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for ICIs are in the metastatic setting, where palliative radiotherapy is frequently important, the authors noted.

In two retrospective studies of patients with metastatic cancers receiving palliative radiotherapy with ICIs, there was a lack of clear association between the irradiated site and specific immune-related adverse events; that lack of association suggests that any toxicities arising from interactions between palliative radiotherapy and ICIs are mainly systemic, rather than local, the authors wrote.

Several retrospective series in advanced-stage melanoma patients have suggested that palliative radiotherapy plus ICIs is safe and does not significantly increase incidence of immune-related adverse events. However, findings from one series showed a correlation between both the ICI and radiotherapy dose given and the incidence of immune-related adverse events.

Prospective studies will be essential to optimize the balance between disease control and risk of morbidity associated with ICIs and radiotherapy combinations, the authors concluded.

The researchers declared no competing interests related to their review article.

SOURCE: Hwang WL, et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug;15(8):477-494.

FROM NATURE REVIEWS CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Some studies suggest that adding ICIs to high-dose stereotactic intracranial radiotherapy for brain metastases might increase the risk of treatment-related brain necrosis.

Major finding: The balance of evidence suggests ICIs can be safely combined with palliative radiotherapy.

Study details: A literature review.

Disclosures: The researchers declared no competing interests related to their review article.

Source: Hwang WL et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug;15(8):477-94.

Immunotherapies extend survival for melanoma patients with brain metastases

Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved checkpoint blockade immunotherapy (CBI) and BRAFV600-targeted therapy in 2011, survival times for patients with melanoma brain metastases (MBMs) have significantly improved, with a 91% increase in 4-year overall survival (OS) from 7.4% to 14.1%.

“The management of advanced melanoma has traditionally been tempered by limited responses to conventional therapies, resulting in a median overall survival (OS) of less than 1 year,” wrote J. Bryan Iorgulescu, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues. The report was published in Cancer Immunology Research. “The landscape of advanced melanoma treatment was revolutionized” by the approval of immunotherapy agents, beginning in 2011.

The current, retrospective study involved 2,753 patients with stage IV melanoma. Patient data were drawn from the National Cancer Database, with diagnoses made between 2010 and 2015. Patient management, overall survival, and disease characteristics were evaluated.

During initial review, the researchers found that 35.8% of patients with stage IV melanoma had brain involvement. These patients were further categorized by those with MBM only (39.7%) versus those with extracranial metastatic disease (60.3%), which included involvement of lung (82.9%), liver (8.1%), bone (6.0%), and lymph nodes or distant subcutaneous skin (3%). MBM-only disease was independently predicted by both younger age and geographic location.

Patients receiving first-line CBI therapy demonstrated improved 4-year OS (28.1% vs. 11.1%; P less than.001) and median OS (12.4 months vs. 5.2 months; P less than .001).

Improvements with CBI were most dramatic in patients with MBM-only disease. In these cases, 4-year OS improved from 16.9% to 51.5% (P less than .001), while median OS jumped from 7.7 months to 56.4 months (P less than .001).

Improved OS was also associated with fewer comorbidities, younger age, management at an academic cancer center, single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery, and resection of the MBM.

“Our findings help bridge the gaps in early clinical trials of CBIs that largely excluded stage IV melanoma patients with MBMs, with checkpoint immunotherapy demonstrating a more than doubling of the median and 4-year OS of MBMs,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Iorgulescu et al. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018 July 12 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0067.

Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved checkpoint blockade immunotherapy (CBI) and BRAFV600-targeted therapy in 2011, survival times for patients with melanoma brain metastases (MBMs) have significantly improved, with a 91% increase in 4-year overall survival (OS) from 7.4% to 14.1%.

“The management of advanced melanoma has traditionally been tempered by limited responses to conventional therapies, resulting in a median overall survival (OS) of less than 1 year,” wrote J. Bryan Iorgulescu, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues. The report was published in Cancer Immunology Research. “The landscape of advanced melanoma treatment was revolutionized” by the approval of immunotherapy agents, beginning in 2011.

The current, retrospective study involved 2,753 patients with stage IV melanoma. Patient data were drawn from the National Cancer Database, with diagnoses made between 2010 and 2015. Patient management, overall survival, and disease characteristics were evaluated.

During initial review, the researchers found that 35.8% of patients with stage IV melanoma had brain involvement. These patients were further categorized by those with MBM only (39.7%) versus those with extracranial metastatic disease (60.3%), which included involvement of lung (82.9%), liver (8.1%), bone (6.0%), and lymph nodes or distant subcutaneous skin (3%). MBM-only disease was independently predicted by both younger age and geographic location.

Patients receiving first-line CBI therapy demonstrated improved 4-year OS (28.1% vs. 11.1%; P less than.001) and median OS (12.4 months vs. 5.2 months; P less than .001).

Improvements with CBI were most dramatic in patients with MBM-only disease. In these cases, 4-year OS improved from 16.9% to 51.5% (P less than .001), while median OS jumped from 7.7 months to 56.4 months (P less than .001).

Improved OS was also associated with fewer comorbidities, younger age, management at an academic cancer center, single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery, and resection of the MBM.

“Our findings help bridge the gaps in early clinical trials of CBIs that largely excluded stage IV melanoma patients with MBMs, with checkpoint immunotherapy demonstrating a more than doubling of the median and 4-year OS of MBMs,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Iorgulescu et al. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018 July 12 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0067.

Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved checkpoint blockade immunotherapy (CBI) and BRAFV600-targeted therapy in 2011, survival times for patients with melanoma brain metastases (MBMs) have significantly improved, with a 91% increase in 4-year overall survival (OS) from 7.4% to 14.1%.

“The management of advanced melanoma has traditionally been tempered by limited responses to conventional therapies, resulting in a median overall survival (OS) of less than 1 year,” wrote J. Bryan Iorgulescu, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues. The report was published in Cancer Immunology Research. “The landscape of advanced melanoma treatment was revolutionized” by the approval of immunotherapy agents, beginning in 2011.

The current, retrospective study involved 2,753 patients with stage IV melanoma. Patient data were drawn from the National Cancer Database, with diagnoses made between 2010 and 2015. Patient management, overall survival, and disease characteristics were evaluated.

During initial review, the researchers found that 35.8% of patients with stage IV melanoma had brain involvement. These patients were further categorized by those with MBM only (39.7%) versus those with extracranial metastatic disease (60.3%), which included involvement of lung (82.9%), liver (8.1%), bone (6.0%), and lymph nodes or distant subcutaneous skin (3%). MBM-only disease was independently predicted by both younger age and geographic location.

Patients receiving first-line CBI therapy demonstrated improved 4-year OS (28.1% vs. 11.1%; P less than.001) and median OS (12.4 months vs. 5.2 months; P less than .001).

Improvements with CBI were most dramatic in patients with MBM-only disease. In these cases, 4-year OS improved from 16.9% to 51.5% (P less than .001), while median OS jumped from 7.7 months to 56.4 months (P less than .001).

Improved OS was also associated with fewer comorbidities, younger age, management at an academic cancer center, single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery, and resection of the MBM.

“Our findings help bridge the gaps in early clinical trials of CBIs that largely excluded stage IV melanoma patients with MBMs, with checkpoint immunotherapy demonstrating a more than doubling of the median and 4-year OS of MBMs,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Iorgulescu et al. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018 July 12 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0067.

FROM CANCER IMMUNOLOGY RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Checkpoint blockade immunotherapy and BRAFV600-targeted therapy improve survival for patients with melanoma brain metastases.

Major finding: Patients with melanoma brain metastases receiving first-line checkpoint blockade immunotherapy had an improved 4-year overall survival (28.1% vs. 11.1%; P less than .001) and median overall survival (12.4 months vs. 5.2 months; P less than .001).

Study details: A retrospective study of 2,753 patients with stage IV melanoma and brain metastases, from the National Cancer Database, between 2010 and 2015.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute of Health, Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and others. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Iorgulescu et al. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018 July 12. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0067.

Recombinant poliovirus appears safe, active as recurrent glioblastoma treatment

Treatment with the recombinant poliovirus vaccine PVSRIPO in patients with recurrent glioblastoma can be delivered at a safe dose with efficacy that compares favorably with historical data, recently reported results of a phase 1, nonrandomized study suggest.

The survival rate at 36 months after intratumoral infusion of PVSRIPO was 21%, versus 4% in a control group of patients who would have met the study’s eligibility criteria, investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

There was no evidence of virus shedding or viral neuropathogenicity in the study, which included 61 patients with recurrent World Health Organization grade IV malignant glioma. “Further investigations are warranted,” wrote Annick Desjardins, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and her coauthors.

The prognosis of WHO grade IV malignant glioma remains dismal despite aggressive therapy and decades of research focused on advanced surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted agents, Dr. Desjardins and her colleagues said.

Accordingly, they sought to evaluate the potential of PVSRIPO, a live-attenuated poliovirus type 1 vaccine with its viral internal ribosome entry site replaced by one of human rhinovirus type. The engineered virus gains entry via the CD155 receptor, which is upregulated in solid tumors such as glioblastomas and expressed in antigen-presenting cells.

“Tumor cytotoxic effects, interferon-dominant activation of antigen-presenting cells, and the profound inflammatory response to poliovirus may counter tumor-induced immunosuppression and instigate antitumor immunity,” the investigators wrote.

With a median follow-up of 27.6 months, the median overall survival for PVSRIPO-treated patients was 12.5 months, longer than the 11.3 months seen in the historical control group. It was also longer than the 6.6 months found in a second comparison group of patients who underwent therapy with tumor-treating fields, which involves application of alternating electrical current to the head.

Survival hit a “plateau” in the PVSRIPO-treated patients, investigators said, with an overall survival rate of 21% at both 24 and 36 months. That stood in contrast to a decline in the historical control group from 14% at 24 months to 4% at 36 months, and a decline from 8% to 3% in the tumor-treating-fields group.

The phase 1 study had a dose-escalation phase including 9 patients and a dose-expansion phase with 52 patients. In the dose-expansion phase, 19% of patients had grade 3 or greater adverse events attributable to PVSRIPO, according to the report.

Of all 61 patients, 69% had a vaccine-related grade 1 or 2 event as their most severe adverse event.

One patient death caused by complications from an intracranial hemorrhage was attributed to bevacizumab. As part of a study protocol amendment, bevacizumab at half the standard dose was allowed to control symptoms of locoregional inflammation, investigators said.

In an ongoing, phase 2, randomized trial, PVSRIPO is being evaluated alone or with lomustine in patients with recurrent WHO grade IV malignant glioma. The Food and Drug Administration granted breakthrough therapy designation to PVSRIPO in May 2016.

Seven study authors reported equity in Istari Oncology, a biotechnology company that is developing PVSRIPO. Authors also reported disclosures related to Genentech/Roche, Celgene, Celldex, and Eli Lilly, among other entities. The study was supported by grants from the Brain Tumor Research Charity, the Tisch family through the Jewish Communal Fund, the National Institutes of Health, and others.

SOURCE: Desjardins A et al .N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716435.

The potentially useful anticancer properties of viruses are just starting to be recognized and exploited, Dan L. Longo, MD, and Lindsey R. Baden, MD, both with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an editorial.

One approach is the development of oncolytic viruses that can not only directly kill tumor cells, but can also prompt an immune response against viable tumor cells, they wrote. The study by Dr. Desjardins and her colleagues describes clinical experience with PVSRIPO, a recombinant, nonpathogenic polio-rhinovirus chimera. This engineered virus targets glioblastoma by gaining cell entry through the CD155 receptor, which is expressed on solid tumors.

The survival data showed a plateau, with a 36-month survival rate of 21%, compared with 4% for a historical control cohort of patients, Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden noted.

In this study, PVSRIPO was delivered into intracranial tumors using an indwelling catheter. One of the outstanding questions with viral approaches to cancer treatment, according to the editorialists, is how local administration impacts systemic immunity in terms of recognition and elimination of remote lesions.

“Much more needs to be learned, but the clinical results to date encourage further exploration of this new treatment approach,” Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden wrote.

This summary is based on an editorial written by Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Baden and Longo both reported employment by the New England Journal of Medicine as deputy editor. Dr. Baden reported grant support from the Ragon Institute, the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, and the Gates Foundation outside the submitted work and also reported involvement in HIV vaccine trials done in collaboration with NIH, HIV Vaccine Trials Network, and others.

The potentially useful anticancer properties of viruses are just starting to be recognized and exploited, Dan L. Longo, MD, and Lindsey R. Baden, MD, both with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an editorial.

One approach is the development of oncolytic viruses that can not only directly kill tumor cells, but can also prompt an immune response against viable tumor cells, they wrote. The study by Dr. Desjardins and her colleagues describes clinical experience with PVSRIPO, a recombinant, nonpathogenic polio-rhinovirus chimera. This engineered virus targets glioblastoma by gaining cell entry through the CD155 receptor, which is expressed on solid tumors.

The survival data showed a plateau, with a 36-month survival rate of 21%, compared with 4% for a historical control cohort of patients, Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden noted.

In this study, PVSRIPO was delivered into intracranial tumors using an indwelling catheter. One of the outstanding questions with viral approaches to cancer treatment, according to the editorialists, is how local administration impacts systemic immunity in terms of recognition and elimination of remote lesions.

“Much more needs to be learned, but the clinical results to date encourage further exploration of this new treatment approach,” Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden wrote.

This summary is based on an editorial written by Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Baden and Longo both reported employment by the New England Journal of Medicine as deputy editor. Dr. Baden reported grant support from the Ragon Institute, the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, and the Gates Foundation outside the submitted work and also reported involvement in HIV vaccine trials done in collaboration with NIH, HIV Vaccine Trials Network, and others.

The potentially useful anticancer properties of viruses are just starting to be recognized and exploited, Dan L. Longo, MD, and Lindsey R. Baden, MD, both with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an editorial.

One approach is the development of oncolytic viruses that can not only directly kill tumor cells, but can also prompt an immune response against viable tumor cells, they wrote. The study by Dr. Desjardins and her colleagues describes clinical experience with PVSRIPO, a recombinant, nonpathogenic polio-rhinovirus chimera. This engineered virus targets glioblastoma by gaining cell entry through the CD155 receptor, which is expressed on solid tumors.

The survival data showed a plateau, with a 36-month survival rate of 21%, compared with 4% for a historical control cohort of patients, Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden noted.

In this study, PVSRIPO was delivered into intracranial tumors using an indwelling catheter. One of the outstanding questions with viral approaches to cancer treatment, according to the editorialists, is how local administration impacts systemic immunity in terms of recognition and elimination of remote lesions.

“Much more needs to be learned, but the clinical results to date encourage further exploration of this new treatment approach,” Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden wrote.

This summary is based on an editorial written by Dr. Longo and Dr. Baden that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Baden and Longo both reported employment by the New England Journal of Medicine as deputy editor. Dr. Baden reported grant support from the Ragon Institute, the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, and the Gates Foundation outside the submitted work and also reported involvement in HIV vaccine trials done in collaboration with NIH, HIV Vaccine Trials Network, and others.

Treatment with the recombinant poliovirus vaccine PVSRIPO in patients with recurrent glioblastoma can be delivered at a safe dose with efficacy that compares favorably with historical data, recently reported results of a phase 1, nonrandomized study suggest.

The survival rate at 36 months after intratumoral infusion of PVSRIPO was 21%, versus 4% in a control group of patients who would have met the study’s eligibility criteria, investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

There was no evidence of virus shedding or viral neuropathogenicity in the study, which included 61 patients with recurrent World Health Organization grade IV malignant glioma. “Further investigations are warranted,” wrote Annick Desjardins, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and her coauthors.

The prognosis of WHO grade IV malignant glioma remains dismal despite aggressive therapy and decades of research focused on advanced surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted agents, Dr. Desjardins and her colleagues said.

Accordingly, they sought to evaluate the potential of PVSRIPO, a live-attenuated poliovirus type 1 vaccine with its viral internal ribosome entry site replaced by one of human rhinovirus type. The engineered virus gains entry via the CD155 receptor, which is upregulated in solid tumors such as glioblastomas and expressed in antigen-presenting cells.

“Tumor cytotoxic effects, interferon-dominant activation of antigen-presenting cells, and the profound inflammatory response to poliovirus may counter tumor-induced immunosuppression and instigate antitumor immunity,” the investigators wrote.

With a median follow-up of 27.6 months, the median overall survival for PVSRIPO-treated patients was 12.5 months, longer than the 11.3 months seen in the historical control group. It was also longer than the 6.6 months found in a second comparison group of patients who underwent therapy with tumor-treating fields, which involves application of alternating electrical current to the head.

Survival hit a “plateau” in the PVSRIPO-treated patients, investigators said, with an overall survival rate of 21% at both 24 and 36 months. That stood in contrast to a decline in the historical control group from 14% at 24 months to 4% at 36 months, and a decline from 8% to 3% in the tumor-treating-fields group.

The phase 1 study had a dose-escalation phase including 9 patients and a dose-expansion phase with 52 patients. In the dose-expansion phase, 19% of patients had grade 3 or greater adverse events attributable to PVSRIPO, according to the report.

Of all 61 patients, 69% had a vaccine-related grade 1 or 2 event as their most severe adverse event.

One patient death caused by complications from an intracranial hemorrhage was attributed to bevacizumab. As part of a study protocol amendment, bevacizumab at half the standard dose was allowed to control symptoms of locoregional inflammation, investigators said.

In an ongoing, phase 2, randomized trial, PVSRIPO is being evaluated alone or with lomustine in patients with recurrent WHO grade IV malignant glioma. The Food and Drug Administration granted breakthrough therapy designation to PVSRIPO in May 2016.

Seven study authors reported equity in Istari Oncology, a biotechnology company that is developing PVSRIPO. Authors also reported disclosures related to Genentech/Roche, Celgene, Celldex, and Eli Lilly, among other entities. The study was supported by grants from the Brain Tumor Research Charity, the Tisch family through the Jewish Communal Fund, the National Institutes of Health, and others.

SOURCE: Desjardins A et al .N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716435.

Treatment with the recombinant poliovirus vaccine PVSRIPO in patients with recurrent glioblastoma can be delivered at a safe dose with efficacy that compares favorably with historical data, recently reported results of a phase 1, nonrandomized study suggest.

The survival rate at 36 months after intratumoral infusion of PVSRIPO was 21%, versus 4% in a control group of patients who would have met the study’s eligibility criteria, investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

There was no evidence of virus shedding or viral neuropathogenicity in the study, which included 61 patients with recurrent World Health Organization grade IV malignant glioma. “Further investigations are warranted,” wrote Annick Desjardins, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and her coauthors.

The prognosis of WHO grade IV malignant glioma remains dismal despite aggressive therapy and decades of research focused on advanced surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted agents, Dr. Desjardins and her colleagues said.

Accordingly, they sought to evaluate the potential of PVSRIPO, a live-attenuated poliovirus type 1 vaccine with its viral internal ribosome entry site replaced by one of human rhinovirus type. The engineered virus gains entry via the CD155 receptor, which is upregulated in solid tumors such as glioblastomas and expressed in antigen-presenting cells.

“Tumor cytotoxic effects, interferon-dominant activation of antigen-presenting cells, and the profound inflammatory response to poliovirus may counter tumor-induced immunosuppression and instigate antitumor immunity,” the investigators wrote.

With a median follow-up of 27.6 months, the median overall survival for PVSRIPO-treated patients was 12.5 months, longer than the 11.3 months seen in the historical control group. It was also longer than the 6.6 months found in a second comparison group of patients who underwent therapy with tumor-treating fields, which involves application of alternating electrical current to the head.

Survival hit a “plateau” in the PVSRIPO-treated patients, investigators said, with an overall survival rate of 21% at both 24 and 36 months. That stood in contrast to a decline in the historical control group from 14% at 24 months to 4% at 36 months, and a decline from 8% to 3% in the tumor-treating-fields group.

The phase 1 study had a dose-escalation phase including 9 patients and a dose-expansion phase with 52 patients. In the dose-expansion phase, 19% of patients had grade 3 or greater adverse events attributable to PVSRIPO, according to the report.

Of all 61 patients, 69% had a vaccine-related grade 1 or 2 event as their most severe adverse event.

One patient death caused by complications from an intracranial hemorrhage was attributed to bevacizumab. As part of a study protocol amendment, bevacizumab at half the standard dose was allowed to control symptoms of locoregional inflammation, investigators said.

In an ongoing, phase 2, randomized trial, PVSRIPO is being evaluated alone or with lomustine in patients with recurrent WHO grade IV malignant glioma. The Food and Drug Administration granted breakthrough therapy designation to PVSRIPO in May 2016.

Seven study authors reported equity in Istari Oncology, a biotechnology company that is developing PVSRIPO. Authors also reported disclosures related to Genentech/Roche, Celgene, Celldex, and Eli Lilly, among other entities. The study was supported by grants from the Brain Tumor Research Charity, the Tisch family through the Jewish Communal Fund, the National Institutes of Health, and others.

SOURCE: Desjardins A et al .N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716435.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Delivery of PVSRIPO was safe, with efficacy comparing favorably with historical data.

Major finding: Overall survival reached 21% at 24 months and remained at 21% at 36 months.

Study details: A phase 1 study including 61 patients with recurrent World Health Organization grade IV glioma.

Disclosures: Seven study authors reported equity in Istari Oncology, a biotechnology company that is developing PVSRIPO. Study authors also reported disclosures related to Genentech/Roche, Celgene, Celldex, and Eli Lilly, among other entities. The study was supported by grants from the Brain Tumor Research Charity, the Tisch family through the Jewish Communal Fund, the National Institutes of Health, and others.

Source: Desjardins A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716435.

Screening for brain mets could improve quality of life for some with breast cancer

Despite having more extensive metastases at presentation, breast cancer patients had outcomes after brain-directed therapy similar to those of lung cancer patients, results of a retrospective, single-center study show.

The breast cancer patients had larger and more numerous brain metastases compared with the non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, according to study results published in JAMA Oncology.

However, median survival was not statistically different between groups, at 1.45 years for the breast cancer patients and 1.09 years for NSCLC patients (P = .06), wrote Daniel N. Cagney, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his coauthors.

“This finding suggests that intracranial disease in patients with breast cancer was not more aggressive or resistant to treatment, but rather was diagnosed at a later stage,” noted Dr. Cagney and his colleagues.

They described a retrospective analysis of 349 patients with breast cancer and 659 patients with NSCLC, all treated between 2000 and 2015 at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center.

Median metastasis diameter at presentation was 17 mm for the breast cancer patients, compared with 14 mm for the lung cancer patients (P less than .001). Breast cancer patients were significantly more likely to be symptomatic, have seizures, harbor brainstem involvement, and have leptomeningeal disease at the time of diagnosis, the researchers wrote.

“After initial brain-directed therapy, no significant differences in recurrence or treatment-based intracranial outcomes were found between the two groups,” they noted. However, neurological death was seen in 37.3% of the breast cancer group versus 19.9% of the lung cancer group (P less than .001).

Dr. Cagney and his coauthors said they conducted the study to identify the potential value of brain-directed MRI screening in breast cancer, which they said is “important given the impact of neurological compromise on quality of life.”

Brain metastases are common in some subsets of breast cancer patients, yet National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines do not recommend brain-directed screening in breast cancer, “a recommendation that is based only on expert consensus given the lack of definitive or prospective studies on this issue,” they wrote.

In light of their findings, the investigators suggest that brain-directed MRI screening is important for breast cancer patients who present with potential for intracranial involvement.

“Early identification of intracranial disease facilitates less invasive or less toxic approaches, such as stereotactic radiosurgery or careful use of promising systemic agents, rather than [whole brain radiation therapy] or neurosurgical resection.” they wrote.

In this study, whole brain radiation therapy was more common in the breast cancer group (59.9% versus 42.9% for the lung cancer group; P less than .001), the investigators noted.

Dr. Cagney and colleagues had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Cagney DN et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0813.

Despite having more extensive metastases at presentation, breast cancer patients had outcomes after brain-directed therapy similar to those of lung cancer patients, results of a retrospective, single-center study show.

The breast cancer patients had larger and more numerous brain metastases compared with the non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, according to study results published in JAMA Oncology.

However, median survival was not statistically different between groups, at 1.45 years for the breast cancer patients and 1.09 years for NSCLC patients (P = .06), wrote Daniel N. Cagney, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his coauthors.

“This finding suggests that intracranial disease in patients with breast cancer was not more aggressive or resistant to treatment, but rather was diagnosed at a later stage,” noted Dr. Cagney and his colleagues.

They described a retrospective analysis of 349 patients with breast cancer and 659 patients with NSCLC, all treated between 2000 and 2015 at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center.

Median metastasis diameter at presentation was 17 mm for the breast cancer patients, compared with 14 mm for the lung cancer patients (P less than .001). Breast cancer patients were significantly more likely to be symptomatic, have seizures, harbor brainstem involvement, and have leptomeningeal disease at the time of diagnosis, the researchers wrote.

“After initial brain-directed therapy, no significant differences in recurrence or treatment-based intracranial outcomes were found between the two groups,” they noted. However, neurological death was seen in 37.3% of the breast cancer group versus 19.9% of the lung cancer group (P less than .001).

Dr. Cagney and his coauthors said they conducted the study to identify the potential value of brain-directed MRI screening in breast cancer, which they said is “important given the impact of neurological compromise on quality of life.”

Brain metastases are common in some subsets of breast cancer patients, yet National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines do not recommend brain-directed screening in breast cancer, “a recommendation that is based only on expert consensus given the lack of definitive or prospective studies on this issue,” they wrote.

In light of their findings, the investigators suggest that brain-directed MRI screening is important for breast cancer patients who present with potential for intracranial involvement.

“Early identification of intracranial disease facilitates less invasive or less toxic approaches, such as stereotactic radiosurgery or careful use of promising systemic agents, rather than [whole brain radiation therapy] or neurosurgical resection.” they wrote.

In this study, whole brain radiation therapy was more common in the breast cancer group (59.9% versus 42.9% for the lung cancer group; P less than .001), the investigators noted.

Dr. Cagney and colleagues had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Cagney DN et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0813.

Despite having more extensive metastases at presentation, breast cancer patients had outcomes after brain-directed therapy similar to those of lung cancer patients, results of a retrospective, single-center study show.

The breast cancer patients had larger and more numerous brain metastases compared with the non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, according to study results published in JAMA Oncology.

However, median survival was not statistically different between groups, at 1.45 years for the breast cancer patients and 1.09 years for NSCLC patients (P = .06), wrote Daniel N. Cagney, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his coauthors.

“This finding suggests that intracranial disease in patients with breast cancer was not more aggressive or resistant to treatment, but rather was diagnosed at a later stage,” noted Dr. Cagney and his colleagues.

They described a retrospective analysis of 349 patients with breast cancer and 659 patients with NSCLC, all treated between 2000 and 2015 at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center.

Median metastasis diameter at presentation was 17 mm for the breast cancer patients, compared with 14 mm for the lung cancer patients (P less than .001). Breast cancer patients were significantly more likely to be symptomatic, have seizures, harbor brainstem involvement, and have leptomeningeal disease at the time of diagnosis, the researchers wrote.

“After initial brain-directed therapy, no significant differences in recurrence or treatment-based intracranial outcomes were found between the two groups,” they noted. However, neurological death was seen in 37.3% of the breast cancer group versus 19.9% of the lung cancer group (P less than .001).

Dr. Cagney and his coauthors said they conducted the study to identify the potential value of brain-directed MRI screening in breast cancer, which they said is “important given the impact of neurological compromise on quality of life.”

Brain metastases are common in some subsets of breast cancer patients, yet National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines do not recommend brain-directed screening in breast cancer, “a recommendation that is based only on expert consensus given the lack of definitive or prospective studies on this issue,” they wrote.

In light of their findings, the investigators suggest that brain-directed MRI screening is important for breast cancer patients who present with potential for intracranial involvement.

“Early identification of intracranial disease facilitates less invasive or less toxic approaches, such as stereotactic radiosurgery or careful use of promising systemic agents, rather than [whole brain radiation therapy] or neurosurgical resection.” they wrote.

In this study, whole brain radiation therapy was more common in the breast cancer group (59.9% versus 42.9% for the lung cancer group; P less than .001), the investigators noted.

Dr. Cagney and colleagues had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Cagney DN et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0813.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Breast cancer patients presented with larger and more numerous brain metastases compared with non–small-cell lung cancer patients, but after brain-directed therapy, there were no differences in outcomes between groups.

Major finding: Median survival was 1.45 years for breast cancer patients and 1.09 for NSCLC patients.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 349 patients with breast cancer and 659 patients with NSCLC treated between 2000 and 2015 at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Cagney DN et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0813.

cfDNA reveals targetable mutations in pediatric neuroblastoma, sarcoma

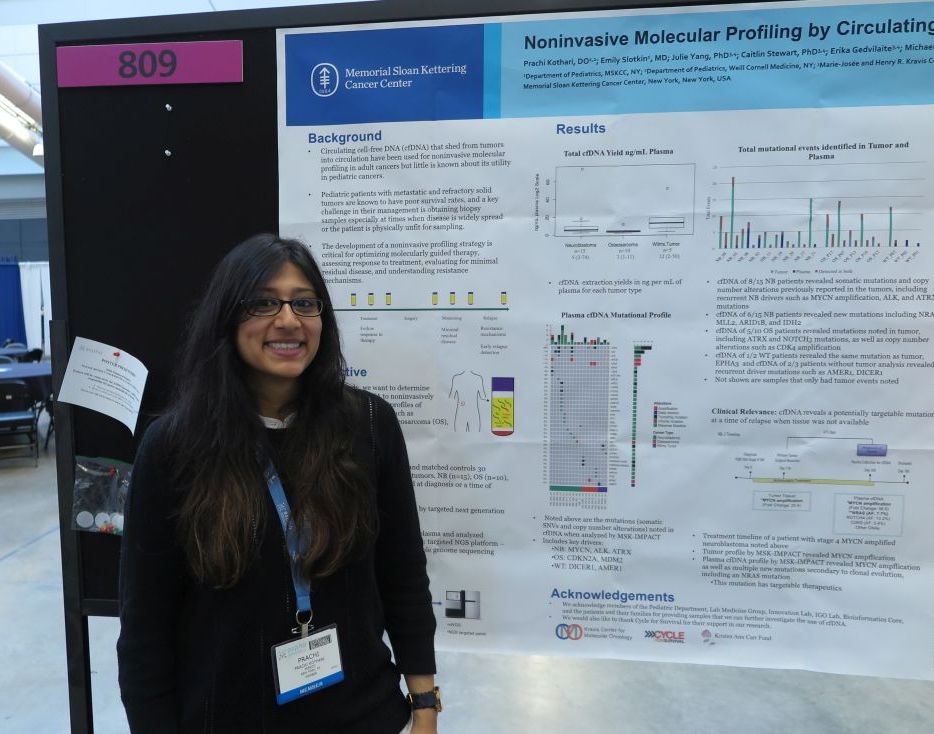

PITTSBURGH – Genetic analysis of circulating free DNA (cfDNA) from pediatric solid tumors can noninvasively identify somatic mutations and copy number alterations that could be used to identify therapeutic targets, investigators reported.

An analysis of tumor specimens and plasma samples from children with neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, and Wilms tumor revealed in cfDNA both somatic mutations and copy number alterations that had already been detected in the solid tumors, and new, potentially targetable mutations, reported Prachi Kothari, DO, and her colleagues from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“Circulating free DNA is much less invasive than a tumor biopsy, and you can do it throughout the patient’s entire timeline of treatment, so you get real-time information or after they relapse to see what’s going on if you’re not able to get a tumor biopsy,” Dr. Kothari said at annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

So-called “liquid biopsy” using cfDNA has been used for molecular profiling of adults malignancies, but there are few data on its use in pediatric tumors, Dr. Kothari said.

To see whether the technique could provide useful clinical information for the management of pediatric tumors, the investigators examined tumor samples taken at diagnosis or at the time of disease progression from 15 patients with neuroblastoma, 10 with osteosarcoma, and 5 with Wilms tumor. They analyzed the tumor samples using targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS), and cfDNA using three different genomic analysis techniques, including NGS, MSK-IMPACT (Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets), and shallow whole genome sequencing.

For each of the tumor types studies, cfDNA analysis with the MSK-IMPACT platform identified key drivers of malignancy, including MYCN, ALK, and ATRX in neuroblastoma; CDKN2A and MDM2 in osteosarcoma; and DICER1 and AMER1 in Wilms tumor.

The cfDNA samples also revealed somatic mutations and copy number alterations previously reported in the tumors of 8 of the 15 patients with neuroblastoma, as well as potentially targetable new mutations in 6 of the 15 patients, including NRAS, MLL2, ARID1B, and IDH2.

For example, in one patient with stage 4 MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, both tumor analysis and cfDNA revealed MYCN amplification, but cfDNA also show multiple new mutations, including a targetable NRAS mutation, secondary to clonal mutation.

In 5 of the 10 patients with osteosarcoma, cfDNA detected mutations that had been seen in the tumor samples, including mutations in ATRX and NOTCH3, and copy number alterations such as CDK4 amplification,

Of the five patients with Wilms tumors, cfDNA analysis was performed on two samples, one of which showed the same mutation as the tumor. Additionally, for the three patients without tumor analysis, cfDNA showed recurrent driver mutations such as AMER1 and DICER1.

The investigators have used the data from this study to create a genome-wide z score derived from shallow whole genome sequencing profiles and cfDNA, and found that a high genomewide z score, compared with a low score was significantly associated a more than four-fold greater risk for worse survival (hazard ratio, 4.42; P = .049).

“Establishing a platform using cfDNA to identify molecular profiles of these tumors can serve as a powerful tool for guiding treatment and monitoring response to treatment,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by Cycle for Survival and the Kristen Ann Carr Fund. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kothari P et al. ASPHO 2018. Abstract #809.

PITTSBURGH – Genetic analysis of circulating free DNA (cfDNA) from pediatric solid tumors can noninvasively identify somatic mutations and copy number alterations that could be used to identify therapeutic targets, investigators reported.

An analysis of tumor specimens and plasma samples from children with neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, and Wilms tumor revealed in cfDNA both somatic mutations and copy number alterations that had already been detected in the solid tumors, and new, potentially targetable mutations, reported Prachi Kothari, DO, and her colleagues from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“Circulating free DNA is much less invasive than a tumor biopsy, and you can do it throughout the patient’s entire timeline of treatment, so you get real-time information or after they relapse to see what’s going on if you’re not able to get a tumor biopsy,” Dr. Kothari said at annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

So-called “liquid biopsy” using cfDNA has been used for molecular profiling of adults malignancies, but there are few data on its use in pediatric tumors, Dr. Kothari said.

To see whether the technique could provide useful clinical information for the management of pediatric tumors, the investigators examined tumor samples taken at diagnosis or at the time of disease progression from 15 patients with neuroblastoma, 10 with osteosarcoma, and 5 with Wilms tumor. They analyzed the tumor samples using targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS), and cfDNA using three different genomic analysis techniques, including NGS, MSK-IMPACT (Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets), and shallow whole genome sequencing.

For each of the tumor types studies, cfDNA analysis with the MSK-IMPACT platform identified key drivers of malignancy, including MYCN, ALK, and ATRX in neuroblastoma; CDKN2A and MDM2 in osteosarcoma; and DICER1 and AMER1 in Wilms tumor.

The cfDNA samples also revealed somatic mutations and copy number alterations previously reported in the tumors of 8 of the 15 patients with neuroblastoma, as well as potentially targetable new mutations in 6 of the 15 patients, including NRAS, MLL2, ARID1B, and IDH2.

For example, in one patient with stage 4 MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, both tumor analysis and cfDNA revealed MYCN amplification, but cfDNA also show multiple new mutations, including a targetable NRAS mutation, secondary to clonal mutation.

In 5 of the 10 patients with osteosarcoma, cfDNA detected mutations that had been seen in the tumor samples, including mutations in ATRX and NOTCH3, and copy number alterations such as CDK4 amplification,

Of the five patients with Wilms tumors, cfDNA analysis was performed on two samples, one of which showed the same mutation as the tumor. Additionally, for the three patients without tumor analysis, cfDNA showed recurrent driver mutations such as AMER1 and DICER1.

The investigators have used the data from this study to create a genome-wide z score derived from shallow whole genome sequencing profiles and cfDNA, and found that a high genomewide z score, compared with a low score was significantly associated a more than four-fold greater risk for worse survival (hazard ratio, 4.42; P = .049).

“Establishing a platform using cfDNA to identify molecular profiles of these tumors can serve as a powerful tool for guiding treatment and monitoring response to treatment,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by Cycle for Survival and the Kristen Ann Carr Fund. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kothari P et al. ASPHO 2018. Abstract #809.

PITTSBURGH – Genetic analysis of circulating free DNA (cfDNA) from pediatric solid tumors can noninvasively identify somatic mutations and copy number alterations that could be used to identify therapeutic targets, investigators reported.

An analysis of tumor specimens and plasma samples from children with neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, and Wilms tumor revealed in cfDNA both somatic mutations and copy number alterations that had already been detected in the solid tumors, and new, potentially targetable mutations, reported Prachi Kothari, DO, and her colleagues from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“Circulating free DNA is much less invasive than a tumor biopsy, and you can do it throughout the patient’s entire timeline of treatment, so you get real-time information or after they relapse to see what’s going on if you’re not able to get a tumor biopsy,” Dr. Kothari said at annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

So-called “liquid biopsy” using cfDNA has been used for molecular profiling of adults malignancies, but there are few data on its use in pediatric tumors, Dr. Kothari said.

To see whether the technique could provide useful clinical information for the management of pediatric tumors, the investigators examined tumor samples taken at diagnosis or at the time of disease progression from 15 patients with neuroblastoma, 10 with osteosarcoma, and 5 with Wilms tumor. They analyzed the tumor samples using targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS), and cfDNA using three different genomic analysis techniques, including NGS, MSK-IMPACT (Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets), and shallow whole genome sequencing.

For each of the tumor types studies, cfDNA analysis with the MSK-IMPACT platform identified key drivers of malignancy, including MYCN, ALK, and ATRX in neuroblastoma; CDKN2A and MDM2 in osteosarcoma; and DICER1 and AMER1 in Wilms tumor.

The cfDNA samples also revealed somatic mutations and copy number alterations previously reported in the tumors of 8 of the 15 patients with neuroblastoma, as well as potentially targetable new mutations in 6 of the 15 patients, including NRAS, MLL2, ARID1B, and IDH2.

For example, in one patient with stage 4 MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma, both tumor analysis and cfDNA revealed MYCN amplification, but cfDNA also show multiple new mutations, including a targetable NRAS mutation, secondary to clonal mutation.

In 5 of the 10 patients with osteosarcoma, cfDNA detected mutations that had been seen in the tumor samples, including mutations in ATRX and NOTCH3, and copy number alterations such as CDK4 amplification,

Of the five patients with Wilms tumors, cfDNA analysis was performed on two samples, one of which showed the same mutation as the tumor. Additionally, for the three patients without tumor analysis, cfDNA showed recurrent driver mutations such as AMER1 and DICER1.

The investigators have used the data from this study to create a genome-wide z score derived from shallow whole genome sequencing profiles and cfDNA, and found that a high genomewide z score, compared with a low score was significantly associated a more than four-fold greater risk for worse survival (hazard ratio, 4.42; P = .049).

“Establishing a platform using cfDNA to identify molecular profiles of these tumors can serve as a powerful tool for guiding treatment and monitoring response to treatment,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by Cycle for Survival and the Kristen Ann Carr Fund. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kothari P et al. ASPHO 2018. Abstract #809.

REPORTING FROM ASPHO 2018

Key clinical point: Circulating free DNA analysis is a noninvasive method for detecting potential therapeutic targets.

Major finding: cfDNA revealed potentially targetable new mutations in 6 of 15 patients with neuroblastoma.

Study details: Retrospective analysis of tumor and plasma samples in 30 patients with neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, or Wilms tumor.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Cycle for Survival and the Kristen Ann Carr Fund. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kothari P et al. ASPHO 2018. Abstract #809.

Surgery indicates higher survival with adrenal cortical carcinoma

CHICAGO –

These findings, uncovered using the largest cancer registry in the United States, will help give physicians insight into what the best course of action is for treating their patients, according to presenters.

“Surgical resection of the primary tumor improved survival in all stages of disease, whereas adjuvant therapy with chemotherapy or radiation improved overall survival only in stage IVpatients,” said Sri Harsha Tella, MD, endocrinologist at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. “These results may help the prognostication of patients in treatment decision making.”

Investigators conducted a retrospective study of 3,185 pathologically confirmed cases of ACC, registered into the National Cancer Database between 2004 and 2015.

Patients were mostly women with an average age of 55 years old and private insurance, with a nearly even split of patients with stage I-III (26%) and stage IV ACC (24%). Nearly three-quarters of those studied chose to have surgery, of which 31% chose open resection.

Patients with stage I-III ACC had a significant median survival rate of 63 months, compared with those who did not have surgery who had an average survival of 8 months.

In patients with stage IV ACC, surgery lengthened overall survival to 19 months, compared with 6 months for those without surgery, according to Dr. Tella and fellow investigators.

While surgery did have a greater positive effect on patients’ live spans across all stages, the impact of chemotherapy and radiation was significant only among stage IV patients who had complete surgery.

Those in the stage IV group who were given post-surgery adjuvant chemotherapy were likely to live an average of nearly 9 more months than did those who did not have chemotherapy after radiation (22 vs. 13), while those given radiation therapy saw an increase in survival by 19 months (29 vs. 10). These increases did not affect stage I-III patients, who had a similar rate of survival regardless of additional therapies after their surgery (24 vs. 25 months).

One possible explanation for why additional therapy made little difference in survival for stage I-III patients is that, given that the tumors did not spread as widely, the surgical procedures were likely to be more effective at removing most of the disease, according to Dr. Tella.

“One of the possibilities is that surgeons were able to get the whole mass out,” Dr. Tella hypothesized in response to a question from attendees. “On the other hand, patients with stage IV ACC may be more likely to have more presence of metastases and so would benefit more greatly from the removal of the primary tumor and then also additional therapy.”

Investigators noted that because of the structure of the registry, they were unable to determine the initiation and duration of chemotherapy, as well as doses of radiation therapy received by the patient.

A more robust database and future stage-specific, prospective clinical trials are needed in order to better understand these findings, Dr. Tella said.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Tella SH et al. Endo 2018.

CHICAGO –

These findings, uncovered using the largest cancer registry in the United States, will help give physicians insight into what the best course of action is for treating their patients, according to presenters.

“Surgical resection of the primary tumor improved survival in all stages of disease, whereas adjuvant therapy with chemotherapy or radiation improved overall survival only in stage IVpatients,” said Sri Harsha Tella, MD, endocrinologist at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. “These results may help the prognostication of patients in treatment decision making.”

Investigators conducted a retrospective study of 3,185 pathologically confirmed cases of ACC, registered into the National Cancer Database between 2004 and 2015.

Patients were mostly women with an average age of 55 years old and private insurance, with a nearly even split of patients with stage I-III (26%) and stage IV ACC (24%). Nearly three-quarters of those studied chose to have surgery, of which 31% chose open resection.

Patients with stage I-III ACC had a significant median survival rate of 63 months, compared with those who did not have surgery who had an average survival of 8 months.

In patients with stage IV ACC, surgery lengthened overall survival to 19 months, compared with 6 months for those without surgery, according to Dr. Tella and fellow investigators.

While surgery did have a greater positive effect on patients’ live spans across all stages, the impact of chemotherapy and radiation was significant only among stage IV patients who had complete surgery.

Those in the stage IV group who were given post-surgery adjuvant chemotherapy were likely to live an average of nearly 9 more months than did those who did not have chemotherapy after radiation (22 vs. 13), while those given radiation therapy saw an increase in survival by 19 months (29 vs. 10). These increases did not affect stage I-III patients, who had a similar rate of survival regardless of additional therapies after their surgery (24 vs. 25 months).

One possible explanation for why additional therapy made little difference in survival for stage I-III patients is that, given that the tumors did not spread as widely, the surgical procedures were likely to be more effective at removing most of the disease, according to Dr. Tella.

“One of the possibilities is that surgeons were able to get the whole mass out,” Dr. Tella hypothesized in response to a question from attendees. “On the other hand, patients with stage IV ACC may be more likely to have more presence of metastases and so would benefit more greatly from the removal of the primary tumor and then also additional therapy.”

Investigators noted that because of the structure of the registry, they were unable to determine the initiation and duration of chemotherapy, as well as doses of radiation therapy received by the patient.

A more robust database and future stage-specific, prospective clinical trials are needed in order to better understand these findings, Dr. Tella said.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Tella SH et al. Endo 2018.

CHICAGO –

These findings, uncovered using the largest cancer registry in the United States, will help give physicians insight into what the best course of action is for treating their patients, according to presenters.

“Surgical resection of the primary tumor improved survival in all stages of disease, whereas adjuvant therapy with chemotherapy or radiation improved overall survival only in stage IVpatients,” said Sri Harsha Tella, MD, endocrinologist at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. “These results may help the prognostication of patients in treatment decision making.”

Investigators conducted a retrospective study of 3,185 pathologically confirmed cases of ACC, registered into the National Cancer Database between 2004 and 2015.

Patients were mostly women with an average age of 55 years old and private insurance, with a nearly even split of patients with stage I-III (26%) and stage IV ACC (24%). Nearly three-quarters of those studied chose to have surgery, of which 31% chose open resection.

Patients with stage I-III ACC had a significant median survival rate of 63 months, compared with those who did not have surgery who had an average survival of 8 months.

In patients with stage IV ACC, surgery lengthened overall survival to 19 months, compared with 6 months for those without surgery, according to Dr. Tella and fellow investigators.

While surgery did have a greater positive effect on patients’ live spans across all stages, the impact of chemotherapy and radiation was significant only among stage IV patients who had complete surgery.

Those in the stage IV group who were given post-surgery adjuvant chemotherapy were likely to live an average of nearly 9 more months than did those who did not have chemotherapy after radiation (22 vs. 13), while those given radiation therapy saw an increase in survival by 19 months (29 vs. 10). These increases did not affect stage I-III patients, who had a similar rate of survival regardless of additional therapies after their surgery (24 vs. 25 months).

One possible explanation for why additional therapy made little difference in survival for stage I-III patients is that, given that the tumors did not spread as widely, the surgical procedures were likely to be more effective at removing most of the disease, according to Dr. Tella.

“One of the possibilities is that surgeons were able to get the whole mass out,” Dr. Tella hypothesized in response to a question from attendees. “On the other hand, patients with stage IV ACC may be more likely to have more presence of metastases and so would benefit more greatly from the removal of the primary tumor and then also additional therapy.”

Investigators noted that because of the structure of the registry, they were unable to determine the initiation and duration of chemotherapy, as well as doses of radiation therapy received by the patient.

A more robust database and future stage-specific, prospective clinical trials are needed in order to better understand these findings, Dr. Tella said.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Tella SH et al. Endo 2018.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2018

Key clinical point: Patients who undergo surgical resection at all stages are more likely to survive.

Major finding: Patients stage I-III who underwent surgery survived over nearly 8 times longer than non-surgery patients (63 vs. 8 months [P less than .001]).

Study details: Retrospective study of 3,185 adrenal cortical carcinoma cases entered into the National Cancer Database between 2004 and 2015.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Tella SH et al. Endo 2018.

Study: Test for PD-L1 amplification in solid tumors

SAN FRANCISCO – Amplification of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), also known as cluster of differentiation 274 (CD274), is rare in most solid tumors, but findings from an analysis in which a majority of patients with the alteration experienced durable responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade suggest that testing for it may be warranted.

Of 117,344 deidentified cancer patient samples from a large database, only 0.7% had PD-L1 amplification, which was defined as 6 or more copy number alterations (CNAs). The CNAs were found across more than 100 tumor histologies, Aaron Goodman, MD, reported at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

Of a subset of 2,039 clinically annotated patients from the database, who were seen at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Center for Personalized Cancer Therapy, 13 (0.6%) had PD-L1 CNAs, and 9 were treated with immune checkpoint blockade, either alone or in combination with another immunotherapeutic or targeted therapy, after a median of four prior systemic therapies.

The PD-1/PD-L1 blockade response rate in those nine patients was 67%, and median progression-free survival was 15.2 months; three objective responses were ongoing for at least 15 months, said Dr. Goodman of UCSD.

The findings are notable, because in unselected patients, the rates of response to immune checkpoint blockade range from 10% to 20%.

Lessons from cHL and solid tumors

“Over the past few years, investigators have identified numerous biomarkers that can select subgroups of patients with increased likelihoods of responding to PD-1 blockade,” he said, adding that biomarkers include PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry, microsatellite instability – with microsatellite instability–high tumors responding extremely well to immunotherapy, tumor mutational burden measured by whole exome sequencing and next generation sequencing, and possibly PD-L1 amplification.

Of note, response rates are high in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). In general, cHL patients respond well to treatment, with the majority being cured by way of multiagent chemotherapy and radiation.

“But for the subpopulation that fails to respond to chemotherapy or relapses, outcomes still remain suboptimal. Remarkably, in the relapsed/refractory population of Hodgkin lymphoma ... response rates to single agent nivolumab and pembrolizumab were 65% to 87% [in recent studies],” he said. “Long-term follow-up demonstrates that the majority of these responses were durable and lasted over a year.”

The question is why relapsed/refractory cHL patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade have such a higher response rate than is typically seen in patients with solid tumors.

One answer might lie in the recent finding that nearly 100% of cHL tumors harbor amplification of 9p24.1; the 9p24.1 amplicon encodes the genes PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2, (and thus is also known as the PDJ amplicon), he explained, adding that “through gene dose-dependent increased expression of PD-L1 ligand on the Hodgkin lymphoma Reed-Sternberg cells, there is also JAK-STAT mediation of further expression of PD-L1 on the Reed-Sternberg cells.

An encounter with a patient with metastatic basal cell carcinoma – a “relatively unusual situation, as the majority of patients are cured with local therapy”– led to interest in looking at 9p24.1 alterations in solid tumors.

The patient had extensive metastatic disease, and had progressed through multiple therapies. Given his limited treatment options, next generation sequencing was performed on a biopsy from his tumor, and it revealed the PTCH1 alteration typical in basal cell carcinoma, as well as amplification of 9p24.1 with PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2 amplification. Nivolumab monotherapy was initiated.

“Within 2 months, he had an excellent partial response to therapy, and I’m pleased to say that he’s in an ongoing complete response 2 years later,” Dr. Goodman said.

It was that case that sparked the idea for the current study.

9p24.1 alterations and checkpoint blockade

“With my interest in hematologic malignancies, I was unaware that [9p24.1] amplification could occur in solid tumors, so the first aim was to determine the prevalence of chromosome 9p24.1 alterations in solid tumors. The next was to determine if patients with solid tumors and chromosome 9p24.1 alterations respond to PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade.

“What is astounding is [that PD-L1 amplification] was found in over 100 unique tumor histologies, although rare in most histologies,” Dr. Goodman said, noting that histologies with a statistically increased prevalence of PD-L1 amplification included breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, and soft tissue sarcoma.

There also were some rare histologies with increased prevalence of PD-L1 amplification, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, renal sarcomatoid carcinoma, bladder squamous cell carcinoma, and liver mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma, he said.

Tumors with a paucity of PD-L1 amplification included colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cutaneous melanoma, although even these still harbored a few patients with amplification, he said.

A closer look at the mutational burden in amplified vs. unamplified tumors showed a median of 7.4 vs. 3.6 mut/mb, but in the PD-L1 amplified group, 85% still had a low-to intermediate mutational burden of 1-20 mut/mb.

“Microsatellite instability and PD-L1 amplification were not mutually exclusive, but a rare event. Five of the 821 cases with PD-L1 amplification were microsatellite high; these included three carcinomas of unknown origin and two cases of gastrointestinal cancer,” he noted.

Treatment outcomes

In the 13 UCSD patients with PD-L1 amplification, nine different malignancies were identified, and all patients had advanced or metastatic disease and were heavily pretreated. Of the nine treated patients, five received anti-PD-1 monotherapy, one received anti-CTLA4/anti-PD-1 combination therapy, and three received a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor plus an investigational agent, which was immunotherapeutic, Dr. Goodman said.

The 67% overall response rate was similar to that seen in Hodgkin lymphoma, and many of the responses were durable; median overall survival was not reached.

Of note, genomic analysis in the 13 UCSD patients found to have PD-L1 amplification showed there were 143 total alterations in 70 different genes. All but one patient had amplification of PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2, and that one had amplification of PD-L1 and PD-L2.

Of six tumors with tissue available to test for PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry, four (67%) tested positive. None were microsatellite high, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were present in five cases.

The tumors that tested negative for PD-L1 expression were from the patient with the rare basal cell cancer, and another with glioblastoma. Both responded to anti-PD1/PD-L1 therapy.