User login

Novel tool accurately predicts suicide after self-harm

Investigators have developed and validated a new risk calculator to help predict death by suicide in the 6-12 months after an episode of nonfatal self-harm, new research shows.

A study led by Seena Fazel, MBChB, MD, University of Oxford, England, suggests the Oxford Suicide Assessment Tool for Self-harm (OxSATS) may help guide treatment decisions and target resources to those most in need, the researchers note.

“Many tools use only simple high/low categories, whereas OxSATS includes probability scores, which align more closely with risk calculators in cardiovascular medicine, such as the Framingham Risk Score, and prognostic models in cancer medicine, which provide 5-year survival probabilities. This potentially allows OxSATS to inform clinical decision-making more directly,” Dr. Fazel told this news organization.

The findings were published online in BMJ Mental Health.

Targeted tool

Self-harm is associated with a 1-year risk of suicide that is 20 times higher than that of the general population. Given that about 16 million people self-harm annually, the impact at a population level is potentially quite large, the researchers note.

Current structured approaches to gauge suicide risk among those who have engaged in self-harm are based on tools developed for other purposes and symptom checklists. “Their poor to moderate performance is therefore not unexpected,” Dr. Fazel told this news organization.

In contrast, OxSATS was specifically developed to predict suicide mortality after self-harm.

Dr. Fazel’s group evaluated data on 53,172 Swedish individuals aged 10 years and older who sought emergency medical care after episodes of self-harm.

The development cohort included 37,523 individuals. Of these, 391 died by suicide within 12 months. The validation cohort included 15,649 individuals; of these people, 178 died by suicide within 12 months.

The final OxSATS model includes 11 predictors related to age and sex, as well as variables related to substance misuse, mental health, and treatment and history of self-harm.

“The performance of the model in external validation was good, with c-index at 6 and 12 months of 0.77,” the researchers note.

Using a cutoff threshold of 1%, the OxSATS correctly identified 68% of those who died by suicide within 6 months, while 71% of those who didn’t die were correctly classified as being at low risk. The figures for risk prediction at 12 months were 82% and 54%, respectively.

The OxSATS has been made into a simple online tool with probability scores for suicide at 6 and 12 months after an episode of self-harm, but without linkage to interventions. A tool on its own is unlikely to improve outcomes, said Dr. Fazel.

“However,” he added, “it can improve consistency in the assessment process, especially in busy clinical settings where people from different professional backgrounds and experience undertake such assessments. It can also highlight the role of modifiable risk factors and provide an opportunity to transparently discuss risk with patients and their carers.”

Valuable work

Reached for comment, Igor Galynker, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said that this is a “very solid study with a very large sample size and solid statistical analysis.”

Another strength of the research is the outcome of suicide death versus suicide attempt or suicidal ideation. “In that respect, it is a valuable paper,” Dr. Galynker, who directs the Mount Sinai Beth Israel Suicide Research Laboratory, told this news organization.

He noted that there are no new risk factors in the model. Rather, the model contains the typical risk factors for suicide, which include male sex, substance misuse, past suicide attempt, and psychiatric diagnosis.

“The strongest risk factor in the model is self-harm by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation, which has been shown before and is therefore unsurprising,” said Dr. Galynker.

In general, the risk factors included in the model are often part of administrative tools for suicide risk assessment, said Dr. Galynker, but the OxSATS “seems easier to use because it has 11 items only.”

Broadly speaking, individuals with mental illness and past suicide attempt, past self-harm, alcohol use, and other risk factors “should be treated proactively with suicide prevention measures,” he told this news organization.

As previously reported, Dr. Galynker and colleagues have developed the Abbreviated Suicide Crisis Syndrome Checklist (A-SCS-C), a novel tool to help identify which suicidal patients who present to the emergency department should be admitted to hospital and which patients can be safely discharged.

Funding for the study was provided by Wellcome Trust and the Swedish Research Council. Dr. Fazel and Dr. Galynker have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators have developed and validated a new risk calculator to help predict death by suicide in the 6-12 months after an episode of nonfatal self-harm, new research shows.

A study led by Seena Fazel, MBChB, MD, University of Oxford, England, suggests the Oxford Suicide Assessment Tool for Self-harm (OxSATS) may help guide treatment decisions and target resources to those most in need, the researchers note.

“Many tools use only simple high/low categories, whereas OxSATS includes probability scores, which align more closely with risk calculators in cardiovascular medicine, such as the Framingham Risk Score, and prognostic models in cancer medicine, which provide 5-year survival probabilities. This potentially allows OxSATS to inform clinical decision-making more directly,” Dr. Fazel told this news organization.

The findings were published online in BMJ Mental Health.

Targeted tool

Self-harm is associated with a 1-year risk of suicide that is 20 times higher than that of the general population. Given that about 16 million people self-harm annually, the impact at a population level is potentially quite large, the researchers note.

Current structured approaches to gauge suicide risk among those who have engaged in self-harm are based on tools developed for other purposes and symptom checklists. “Their poor to moderate performance is therefore not unexpected,” Dr. Fazel told this news organization.

In contrast, OxSATS was specifically developed to predict suicide mortality after self-harm.

Dr. Fazel’s group evaluated data on 53,172 Swedish individuals aged 10 years and older who sought emergency medical care after episodes of self-harm.

The development cohort included 37,523 individuals. Of these, 391 died by suicide within 12 months. The validation cohort included 15,649 individuals; of these people, 178 died by suicide within 12 months.

The final OxSATS model includes 11 predictors related to age and sex, as well as variables related to substance misuse, mental health, and treatment and history of self-harm.

“The performance of the model in external validation was good, with c-index at 6 and 12 months of 0.77,” the researchers note.

Using a cutoff threshold of 1%, the OxSATS correctly identified 68% of those who died by suicide within 6 months, while 71% of those who didn’t die were correctly classified as being at low risk. The figures for risk prediction at 12 months were 82% and 54%, respectively.

The OxSATS has been made into a simple online tool with probability scores for suicide at 6 and 12 months after an episode of self-harm, but without linkage to interventions. A tool on its own is unlikely to improve outcomes, said Dr. Fazel.

“However,” he added, “it can improve consistency in the assessment process, especially in busy clinical settings where people from different professional backgrounds and experience undertake such assessments. It can also highlight the role of modifiable risk factors and provide an opportunity to transparently discuss risk with patients and their carers.”

Valuable work

Reached for comment, Igor Galynker, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said that this is a “very solid study with a very large sample size and solid statistical analysis.”

Another strength of the research is the outcome of suicide death versus suicide attempt or suicidal ideation. “In that respect, it is a valuable paper,” Dr. Galynker, who directs the Mount Sinai Beth Israel Suicide Research Laboratory, told this news organization.

He noted that there are no new risk factors in the model. Rather, the model contains the typical risk factors for suicide, which include male sex, substance misuse, past suicide attempt, and psychiatric diagnosis.

“The strongest risk factor in the model is self-harm by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation, which has been shown before and is therefore unsurprising,” said Dr. Galynker.

In general, the risk factors included in the model are often part of administrative tools for suicide risk assessment, said Dr. Galynker, but the OxSATS “seems easier to use because it has 11 items only.”

Broadly speaking, individuals with mental illness and past suicide attempt, past self-harm, alcohol use, and other risk factors “should be treated proactively with suicide prevention measures,” he told this news organization.

As previously reported, Dr. Galynker and colleagues have developed the Abbreviated Suicide Crisis Syndrome Checklist (A-SCS-C), a novel tool to help identify which suicidal patients who present to the emergency department should be admitted to hospital and which patients can be safely discharged.

Funding for the study was provided by Wellcome Trust and the Swedish Research Council. Dr. Fazel and Dr. Galynker have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators have developed and validated a new risk calculator to help predict death by suicide in the 6-12 months after an episode of nonfatal self-harm, new research shows.

A study led by Seena Fazel, MBChB, MD, University of Oxford, England, suggests the Oxford Suicide Assessment Tool for Self-harm (OxSATS) may help guide treatment decisions and target resources to those most in need, the researchers note.

“Many tools use only simple high/low categories, whereas OxSATS includes probability scores, which align more closely with risk calculators in cardiovascular medicine, such as the Framingham Risk Score, and prognostic models in cancer medicine, which provide 5-year survival probabilities. This potentially allows OxSATS to inform clinical decision-making more directly,” Dr. Fazel told this news organization.

The findings were published online in BMJ Mental Health.

Targeted tool

Self-harm is associated with a 1-year risk of suicide that is 20 times higher than that of the general population. Given that about 16 million people self-harm annually, the impact at a population level is potentially quite large, the researchers note.

Current structured approaches to gauge suicide risk among those who have engaged in self-harm are based on tools developed for other purposes and symptom checklists. “Their poor to moderate performance is therefore not unexpected,” Dr. Fazel told this news organization.

In contrast, OxSATS was specifically developed to predict suicide mortality after self-harm.

Dr. Fazel’s group evaluated data on 53,172 Swedish individuals aged 10 years and older who sought emergency medical care after episodes of self-harm.

The development cohort included 37,523 individuals. Of these, 391 died by suicide within 12 months. The validation cohort included 15,649 individuals; of these people, 178 died by suicide within 12 months.

The final OxSATS model includes 11 predictors related to age and sex, as well as variables related to substance misuse, mental health, and treatment and history of self-harm.

“The performance of the model in external validation was good, with c-index at 6 and 12 months of 0.77,” the researchers note.

Using a cutoff threshold of 1%, the OxSATS correctly identified 68% of those who died by suicide within 6 months, while 71% of those who didn’t die were correctly classified as being at low risk. The figures for risk prediction at 12 months were 82% and 54%, respectively.

The OxSATS has been made into a simple online tool with probability scores for suicide at 6 and 12 months after an episode of self-harm, but without linkage to interventions. A tool on its own is unlikely to improve outcomes, said Dr. Fazel.

“However,” he added, “it can improve consistency in the assessment process, especially in busy clinical settings where people from different professional backgrounds and experience undertake such assessments. It can also highlight the role of modifiable risk factors and provide an opportunity to transparently discuss risk with patients and their carers.”

Valuable work

Reached for comment, Igor Galynker, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said that this is a “very solid study with a very large sample size and solid statistical analysis.”

Another strength of the research is the outcome of suicide death versus suicide attempt or suicidal ideation. “In that respect, it is a valuable paper,” Dr. Galynker, who directs the Mount Sinai Beth Israel Suicide Research Laboratory, told this news organization.

He noted that there are no new risk factors in the model. Rather, the model contains the typical risk factors for suicide, which include male sex, substance misuse, past suicide attempt, and psychiatric diagnosis.

“The strongest risk factor in the model is self-harm by hanging, strangulation, or suffocation, which has been shown before and is therefore unsurprising,” said Dr. Galynker.

In general, the risk factors included in the model are often part of administrative tools for suicide risk assessment, said Dr. Galynker, but the OxSATS “seems easier to use because it has 11 items only.”

Broadly speaking, individuals with mental illness and past suicide attempt, past self-harm, alcohol use, and other risk factors “should be treated proactively with suicide prevention measures,” he told this news organization.

As previously reported, Dr. Galynker and colleagues have developed the Abbreviated Suicide Crisis Syndrome Checklist (A-SCS-C), a novel tool to help identify which suicidal patients who present to the emergency department should be admitted to hospital and which patients can be safely discharged.

Funding for the study was provided by Wellcome Trust and the Swedish Research Council. Dr. Fazel and Dr. Galynker have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Do oral contraceptives increase depression risk?

In addition, OC use in adolescence has been tied to an increased risk for depression later in life. However, some experts believe the study’s methodology may be flawed.

The investigators tracked more than 250,000 women from birth to menopause, gathering information about their use of combined contraceptive pills (progesterone and estrogen), the timing of the initial depression diagnosis, and the onset of depressive symptoms that were not formally diagnosed.

Women who began using these OCs before or at the age of 20 experienced a 130% higher incidence of depressive symptoms, whereas adult users saw a 92% increase. But the higher occurrence of depression tended to decline after the first 2 years of use, except in teenagers, who maintained an increased incidence of depression even after discontinuation.

This effect remained, even after analysis of potential familial confounding.

“Our findings suggest that the use of OCs, particularly during the first 2 years, increases the risk of depression. Additionally, OC use during adolescence might increase the risk of depression later in life,” Therese Johansson, of the department of immunology, genetics, and pathology, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala (Sweden) University, and colleagues wrote.

The study was published online in Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences.

Inconsistent findings

Previous studies suggest an association between adolescent use of hormonal contraceptives (HCs) and increased depression risk, but it’s “less clear” whether these effects are similar in adults, the authors wrote. Randomized clinical trials have “shown little or no effect” of HCs on mood. However, most of these studies didn’t consider previous use of HC.

The researchers wanted to estimate the incidence rate of depression associated with first initiation of OC use as well as the lifetime risk associated with use.

They studied 264,557 female participants in the UK Biobank (aged 37-71 years), collecting data from questionnaires, interviews, physical health measures, biological samples, imaging, and linked health records.

Most participants taking OCs had initiated use during the 1970s/early 1980s when second-generation OCs were predominantly used, consisting of levonorgestrel and ethinyl estradiol.

The researchers conducted a secondary outcome analysis on women who completed the UK Biobank Mental Health Questionnaire (MHQ) to evaluate depressive symptoms.

They estimated the associated risk for depression within 2 years after starting OCs in all women, as well as in groups stratified by age at initiation: before age 20 (adolescents) and age 20 and older (adults). In addition, the investigators estimated the lifetime risk for depression.

Time-dependent analysis compared the effect of OC use at initiation to the effect during the remaining years of use in recent and previous users.

They analyzed a subcohort of female siblings, utilizing “inference about causation from examination of familial confounding,” defined by the authors as a “regression-based approach for determining causality through the use of paired observational data collected from related individuals.”

Adolescents at highest risk

Of the participants, 80.6% had used OCs at some point.

The first 2 years of use were associated with a higher rate of depression among users, compared with never-users (hazard ration, 1.79; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-1.96). Although the risk became less pronounced after that, ever-use was still associated with increased lifetime risk for depression (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09).

Adolescents and adult OC users both experienced higher rates of depression during the first 2 years, with a more marked effect in adolescents than in adults (HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.64-2.32; and HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.54-1.95, respectively).

Previous users of OCs had a higher lifetime risk for depression, compared with never-users (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09).

Of the subcohort of women who completed the MHQ (n = 82,232), about half reported experiencing at least one of the core depressive symptoms.

OC initiation was associated with an increased risk for depressive symptoms during the first 2 years in ever- versus never-users (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.91-2.10).

Those who began using OCs during adolescence had a dramatically higher rate of depressive symptoms, compared with never-users (HR, 2.30; 95% CI, 2.11-2.51), as did adult initiators (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 2.11-2.51).

In the analysis of 7,354 first-degree sister pairs, 81% had initiated OCs. A sibling’s OC use was positively associated with a depression diagnosis, and the cosibling’s OC use was also associated with the sibling’s depression diagnosis. “These results support the hypothesis of a causal relationship between OC use and depression, such that OC use increases the risk of depression,” the authors wrote.

The main limitation is the potential for recall bias in the self-reported data, and that the UK Biobank sample consists of a healthier population than the overall U.K. population, which “hampers the generalizability” of the findings, the authors stated.

Flawed study

In a comment, Natalie Rasgon, MD, founder and director of the Stanford (Calif.) Center for Neuroscience in Women’s Health, said the study was “well researched” and “well written” but had “methodological issues.”

She questioned the sibling component, “which the researchers regard as confirming causality.” The effect may be “important but not causative.” Causality in people who are recalling retrospectively “is highly questionable by any adept researcher because it’s subject to memory. Different siblings may have different recall.”

The authors also didn’t study the indication for OC use. Several medical conditions are treated with OCs, including premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the “number one mood disorder among women of reproductive age.” Including this “could have made a huge difference in outcome data,” said Dr. Rasgon, who was not involved with the study.

Anne-Marie Amies Oelschlager, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Washington, Seattle, noted participants were asked to recall depressive symptoms and OC use as far back as 20-30 years ago, which lends itself to inaccurate recall.

And the researchers didn’t ascertain whether the contraceptives had been used continuously or had been started, stopped, and restarted. Nor did they look at different formulations and doses. And the observational nature of the study “limits the ability to infer causation,” continued Dr. Oelschlager, chair of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinical Consensus Gynecology Committee. She was not involved with the study.

“This study is too flawed to use meaningfully in clinical practice,” Dr. Oelschlager concluded.

The study was primarily funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Brain Foundation, and the Uppsala University Center for Women ‘s Mental Health during the Reproductive Lifespan. The authors, Dr. Rasgon, and Dr. Oelschlager declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, OC use in adolescence has been tied to an increased risk for depression later in life. However, some experts believe the study’s methodology may be flawed.

The investigators tracked more than 250,000 women from birth to menopause, gathering information about their use of combined contraceptive pills (progesterone and estrogen), the timing of the initial depression diagnosis, and the onset of depressive symptoms that were not formally diagnosed.

Women who began using these OCs before or at the age of 20 experienced a 130% higher incidence of depressive symptoms, whereas adult users saw a 92% increase. But the higher occurrence of depression tended to decline after the first 2 years of use, except in teenagers, who maintained an increased incidence of depression even after discontinuation.

This effect remained, even after analysis of potential familial confounding.

“Our findings suggest that the use of OCs, particularly during the first 2 years, increases the risk of depression. Additionally, OC use during adolescence might increase the risk of depression later in life,” Therese Johansson, of the department of immunology, genetics, and pathology, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala (Sweden) University, and colleagues wrote.

The study was published online in Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences.

Inconsistent findings

Previous studies suggest an association between adolescent use of hormonal contraceptives (HCs) and increased depression risk, but it’s “less clear” whether these effects are similar in adults, the authors wrote. Randomized clinical trials have “shown little or no effect” of HCs on mood. However, most of these studies didn’t consider previous use of HC.

The researchers wanted to estimate the incidence rate of depression associated with first initiation of OC use as well as the lifetime risk associated with use.

They studied 264,557 female participants in the UK Biobank (aged 37-71 years), collecting data from questionnaires, interviews, physical health measures, biological samples, imaging, and linked health records.

Most participants taking OCs had initiated use during the 1970s/early 1980s when second-generation OCs were predominantly used, consisting of levonorgestrel and ethinyl estradiol.

The researchers conducted a secondary outcome analysis on women who completed the UK Biobank Mental Health Questionnaire (MHQ) to evaluate depressive symptoms.

They estimated the associated risk for depression within 2 years after starting OCs in all women, as well as in groups stratified by age at initiation: before age 20 (adolescents) and age 20 and older (adults). In addition, the investigators estimated the lifetime risk for depression.

Time-dependent analysis compared the effect of OC use at initiation to the effect during the remaining years of use in recent and previous users.

They analyzed a subcohort of female siblings, utilizing “inference about causation from examination of familial confounding,” defined by the authors as a “regression-based approach for determining causality through the use of paired observational data collected from related individuals.”

Adolescents at highest risk

Of the participants, 80.6% had used OCs at some point.

The first 2 years of use were associated with a higher rate of depression among users, compared with never-users (hazard ration, 1.79; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-1.96). Although the risk became less pronounced after that, ever-use was still associated with increased lifetime risk for depression (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09).

Adolescents and adult OC users both experienced higher rates of depression during the first 2 years, with a more marked effect in adolescents than in adults (HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.64-2.32; and HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.54-1.95, respectively).

Previous users of OCs had a higher lifetime risk for depression, compared with never-users (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09).

Of the subcohort of women who completed the MHQ (n = 82,232), about half reported experiencing at least one of the core depressive symptoms.

OC initiation was associated with an increased risk for depressive symptoms during the first 2 years in ever- versus never-users (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.91-2.10).

Those who began using OCs during adolescence had a dramatically higher rate of depressive symptoms, compared with never-users (HR, 2.30; 95% CI, 2.11-2.51), as did adult initiators (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 2.11-2.51).

In the analysis of 7,354 first-degree sister pairs, 81% had initiated OCs. A sibling’s OC use was positively associated with a depression diagnosis, and the cosibling’s OC use was also associated with the sibling’s depression diagnosis. “These results support the hypothesis of a causal relationship between OC use and depression, such that OC use increases the risk of depression,” the authors wrote.

The main limitation is the potential for recall bias in the self-reported data, and that the UK Biobank sample consists of a healthier population than the overall U.K. population, which “hampers the generalizability” of the findings, the authors stated.

Flawed study

In a comment, Natalie Rasgon, MD, founder and director of the Stanford (Calif.) Center for Neuroscience in Women’s Health, said the study was “well researched” and “well written” but had “methodological issues.”

She questioned the sibling component, “which the researchers regard as confirming causality.” The effect may be “important but not causative.” Causality in people who are recalling retrospectively “is highly questionable by any adept researcher because it’s subject to memory. Different siblings may have different recall.”

The authors also didn’t study the indication for OC use. Several medical conditions are treated with OCs, including premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the “number one mood disorder among women of reproductive age.” Including this “could have made a huge difference in outcome data,” said Dr. Rasgon, who was not involved with the study.

Anne-Marie Amies Oelschlager, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Washington, Seattle, noted participants were asked to recall depressive symptoms and OC use as far back as 20-30 years ago, which lends itself to inaccurate recall.

And the researchers didn’t ascertain whether the contraceptives had been used continuously or had been started, stopped, and restarted. Nor did they look at different formulations and doses. And the observational nature of the study “limits the ability to infer causation,” continued Dr. Oelschlager, chair of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinical Consensus Gynecology Committee. She was not involved with the study.

“This study is too flawed to use meaningfully in clinical practice,” Dr. Oelschlager concluded.

The study was primarily funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Brain Foundation, and the Uppsala University Center for Women ‘s Mental Health during the Reproductive Lifespan. The authors, Dr. Rasgon, and Dr. Oelschlager declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, OC use in adolescence has been tied to an increased risk for depression later in life. However, some experts believe the study’s methodology may be flawed.

The investigators tracked more than 250,000 women from birth to menopause, gathering information about their use of combined contraceptive pills (progesterone and estrogen), the timing of the initial depression diagnosis, and the onset of depressive symptoms that were not formally diagnosed.

Women who began using these OCs before or at the age of 20 experienced a 130% higher incidence of depressive symptoms, whereas adult users saw a 92% increase. But the higher occurrence of depression tended to decline after the first 2 years of use, except in teenagers, who maintained an increased incidence of depression even after discontinuation.

This effect remained, even after analysis of potential familial confounding.

“Our findings suggest that the use of OCs, particularly during the first 2 years, increases the risk of depression. Additionally, OC use during adolescence might increase the risk of depression later in life,” Therese Johansson, of the department of immunology, genetics, and pathology, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala (Sweden) University, and colleagues wrote.

The study was published online in Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences.

Inconsistent findings

Previous studies suggest an association between adolescent use of hormonal contraceptives (HCs) and increased depression risk, but it’s “less clear” whether these effects are similar in adults, the authors wrote. Randomized clinical trials have “shown little or no effect” of HCs on mood. However, most of these studies didn’t consider previous use of HC.

The researchers wanted to estimate the incidence rate of depression associated with first initiation of OC use as well as the lifetime risk associated with use.

They studied 264,557 female participants in the UK Biobank (aged 37-71 years), collecting data from questionnaires, interviews, physical health measures, biological samples, imaging, and linked health records.

Most participants taking OCs had initiated use during the 1970s/early 1980s when second-generation OCs were predominantly used, consisting of levonorgestrel and ethinyl estradiol.

The researchers conducted a secondary outcome analysis on women who completed the UK Biobank Mental Health Questionnaire (MHQ) to evaluate depressive symptoms.

They estimated the associated risk for depression within 2 years after starting OCs in all women, as well as in groups stratified by age at initiation: before age 20 (adolescents) and age 20 and older (adults). In addition, the investigators estimated the lifetime risk for depression.

Time-dependent analysis compared the effect of OC use at initiation to the effect during the remaining years of use in recent and previous users.

They analyzed a subcohort of female siblings, utilizing “inference about causation from examination of familial confounding,” defined by the authors as a “regression-based approach for determining causality through the use of paired observational data collected from related individuals.”

Adolescents at highest risk

Of the participants, 80.6% had used OCs at some point.

The first 2 years of use were associated with a higher rate of depression among users, compared with never-users (hazard ration, 1.79; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-1.96). Although the risk became less pronounced after that, ever-use was still associated with increased lifetime risk for depression (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09).

Adolescents and adult OC users both experienced higher rates of depression during the first 2 years, with a more marked effect in adolescents than in adults (HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.64-2.32; and HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.54-1.95, respectively).

Previous users of OCs had a higher lifetime risk for depression, compared with never-users (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09).

Of the subcohort of women who completed the MHQ (n = 82,232), about half reported experiencing at least one of the core depressive symptoms.

OC initiation was associated with an increased risk for depressive symptoms during the first 2 years in ever- versus never-users (HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.91-2.10).

Those who began using OCs during adolescence had a dramatically higher rate of depressive symptoms, compared with never-users (HR, 2.30; 95% CI, 2.11-2.51), as did adult initiators (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 2.11-2.51).

In the analysis of 7,354 first-degree sister pairs, 81% had initiated OCs. A sibling’s OC use was positively associated with a depression diagnosis, and the cosibling’s OC use was also associated with the sibling’s depression diagnosis. “These results support the hypothesis of a causal relationship between OC use and depression, such that OC use increases the risk of depression,” the authors wrote.

The main limitation is the potential for recall bias in the self-reported data, and that the UK Biobank sample consists of a healthier population than the overall U.K. population, which “hampers the generalizability” of the findings, the authors stated.

Flawed study

In a comment, Natalie Rasgon, MD, founder and director of the Stanford (Calif.) Center for Neuroscience in Women’s Health, said the study was “well researched” and “well written” but had “methodological issues.”

She questioned the sibling component, “which the researchers regard as confirming causality.” The effect may be “important but not causative.” Causality in people who are recalling retrospectively “is highly questionable by any adept researcher because it’s subject to memory. Different siblings may have different recall.”

The authors also didn’t study the indication for OC use. Several medical conditions are treated with OCs, including premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the “number one mood disorder among women of reproductive age.” Including this “could have made a huge difference in outcome data,” said Dr. Rasgon, who was not involved with the study.

Anne-Marie Amies Oelschlager, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Washington, Seattle, noted participants were asked to recall depressive symptoms and OC use as far back as 20-30 years ago, which lends itself to inaccurate recall.

And the researchers didn’t ascertain whether the contraceptives had been used continuously or had been started, stopped, and restarted. Nor did they look at different formulations and doses. And the observational nature of the study “limits the ability to infer causation,” continued Dr. Oelschlager, chair of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinical Consensus Gynecology Committee. She was not involved with the study.

“This study is too flawed to use meaningfully in clinical practice,” Dr. Oelschlager concluded.

The study was primarily funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Brain Foundation, and the Uppsala University Center for Women ‘s Mental Health during the Reproductive Lifespan. The authors, Dr. Rasgon, and Dr. Oelschlager declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRIC SCIENCES

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy programs: How they can be improved

A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) is a drug safety program the FDA can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks (Box1). The FDA may require medication guides, patient package inserts, communication plans for health care professionals, and/or certain packaging and safe disposal technologies for medications that pose a serious risk of abuse or overdose. The FDA may also require elements to assure safe use and/or an implementation system be included in the REMS. Pharmaceutical manufacturers then develop a proposed REMS for FDA review.2 If the FDA approves the proposed REMS, the manufacturer is responsible for implementing the REMS requirements.

Box

There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding psychiatry, the branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental illness. Some of the most common myths include:

The FDA provides this description of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS):

“A [REMS] is a drug safety program that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks. REMS are designed to reinforce medication use behaviors and actions that support the safe use of that medication. While all medications have labeling that informs health care stakeholders about medication risks, only a few medications require a REMS. REMS are not designed to mitigate all the adverse events of a medication, these are communicated to health care providers in the medication’s prescribing information. Rather, REMS focus on preventing, monitoring and/or managing a specific serious risk by informing, educating and/or reinforcing actions to reduce the frequency and/or severity of the event.”1

The REMS program for clozapine3 has been the subject of much discussion in the psychiatric community. The adverse impact of the 2015 update to the clozapine REMS program was emphasized at meetings of both the American Psychiatric Association and the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. A white paper published by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors shortly after the 2015 update concluded, “clozapine is underused due to a variety of barriers related to the drug and its properties, the health care system, regulatory requirements, and reimbursement issues.”4 After an update to the clozapine REMS program in 2021, the FDA temporarily suspended enforcement of certain requirements due to concerns from health care professionals about patient access to the medication because of problems with implementing the clozapine REMS program.5,6 In November 2022, the FDA issued a second announcement of enforcement discretion related to additional requirements of the REMS program.5 The FDA had previously announced a decision to not take action regarding adherence to REMS requirements for certain laboratory tests in March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic.7

REMS programs for other psychiatric medications may also present challenges. The REMS programs for esketamine8 and olanzapine for extended-release (ER) injectable suspension9 include certain risks that require postadministration monitoring. Some facilities have had to dedicate additional space and clinician time to ensure REMS requirements are met.

To further understand health care professionals’ perspectives regarding the value and burden of these REMS programs, a collaborative effort of the University of Maryland (College Park and Baltimore campuses) Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation with the FDA was undertaken. The REMS for clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine were examined to develop recommendations for improving patient access while ensuring safe medication use and limiting the impact on health care professionals.

Assessing the REMS programs

Focus groups were held with health care professionals nominated by professional organizations to gather their perspectives on the REMS requirements. There was 1 focus group for each of the 3 medications. A facilitator’s guide was developed that contained the details of how to conduct the focus group along with the medication-specific questions. The questions were based on the REMS requirements as of May 2021 and assessed the impact of the REMS on patient safety, patient access, and health care professional workload; effects from the COVID-19 pandemic; and suggestions to improve the REMS programs. The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board reviewed the materials and processes and made the determination of exempt.

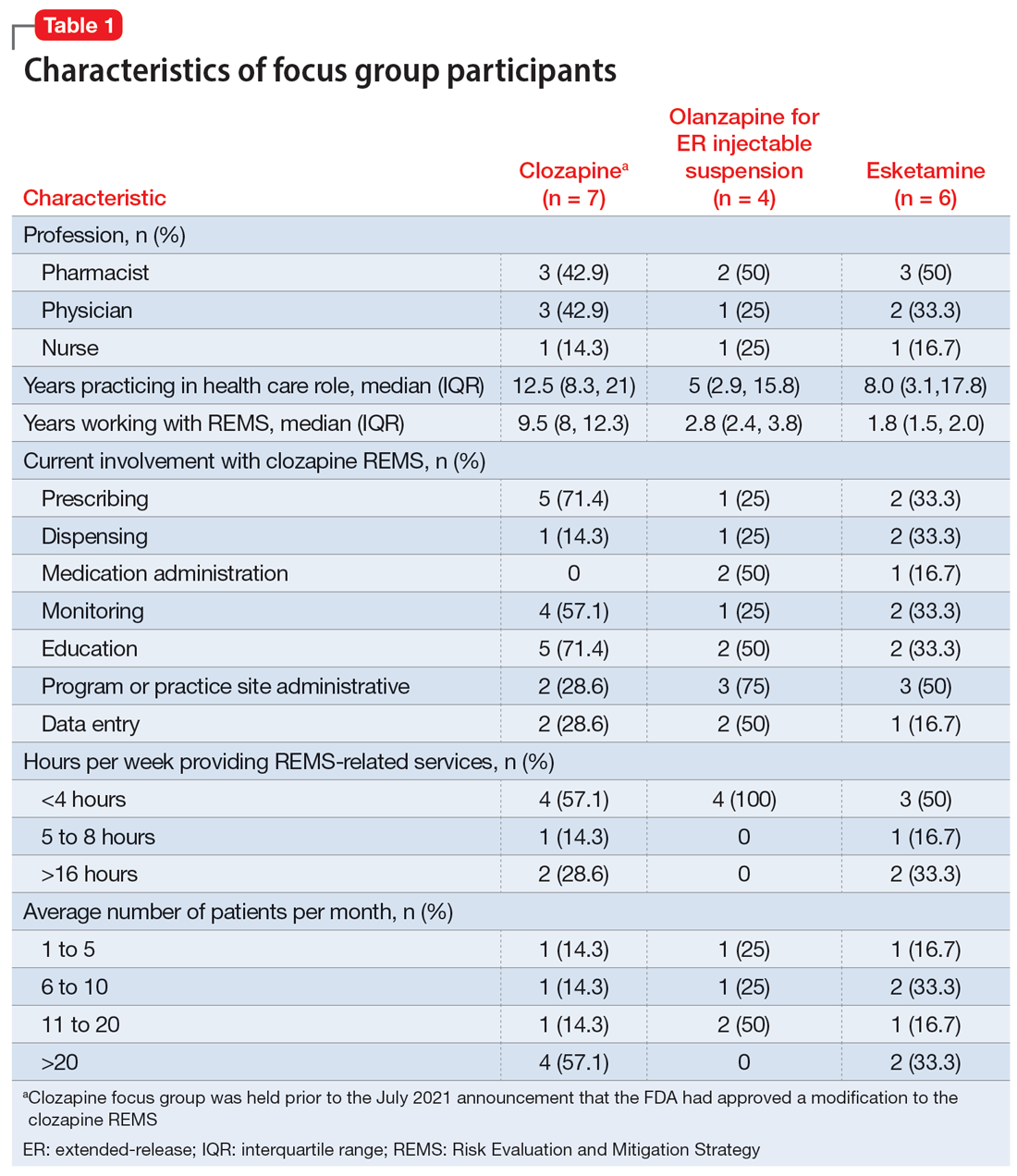

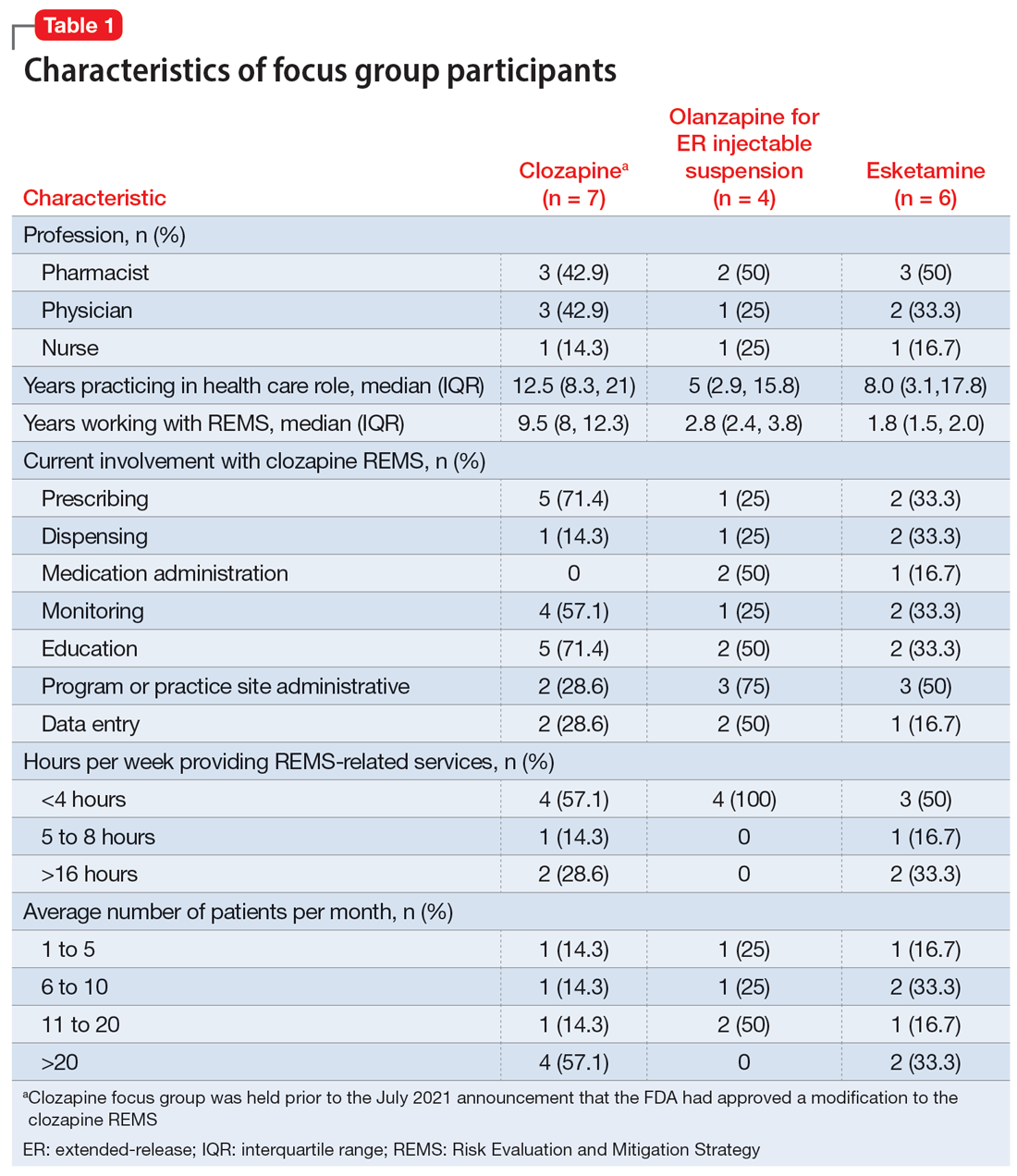

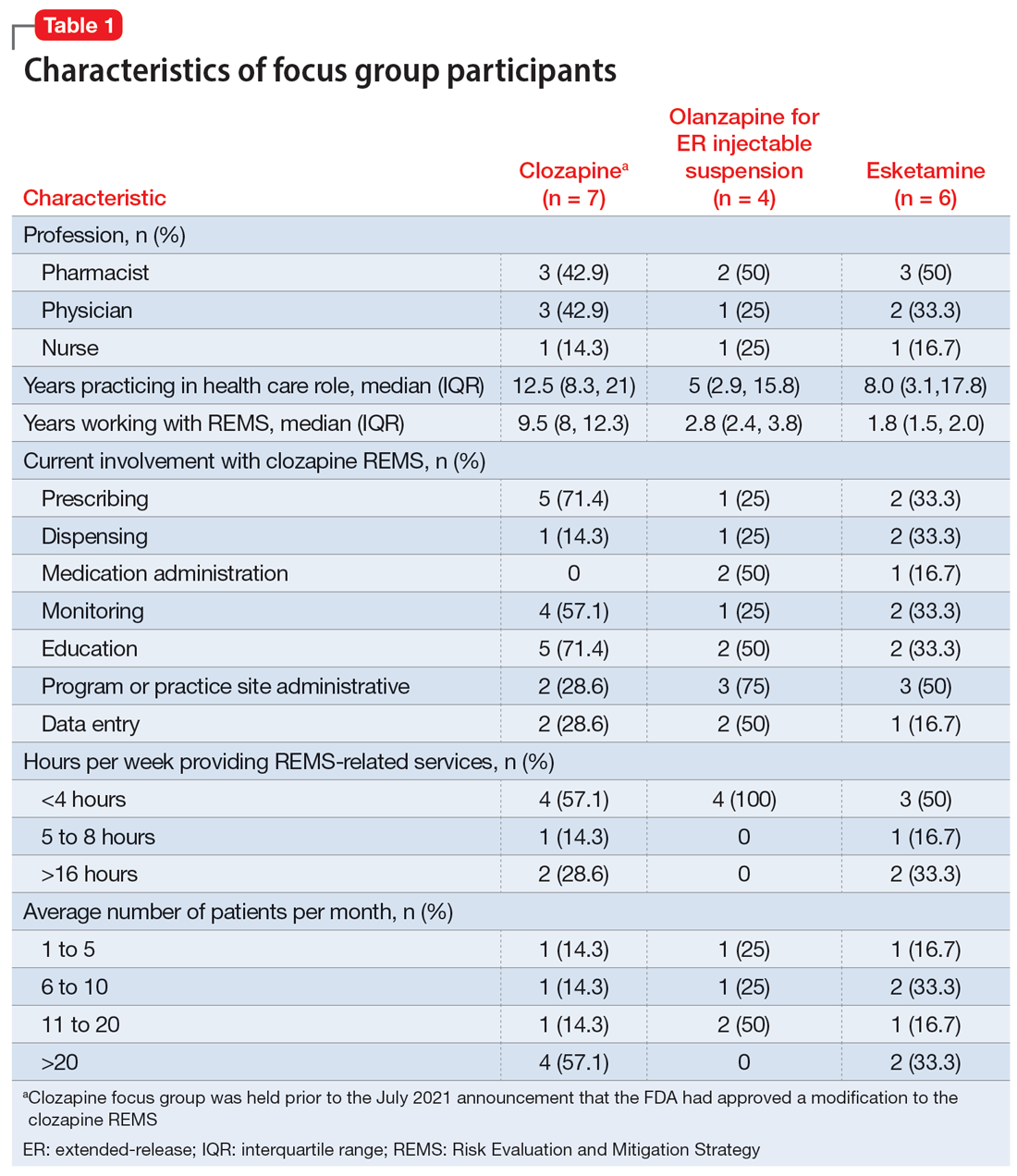

Health care professionals were eligible to participate in a focus group if they had ≥1 year of experience working with patients who use the specific medication and ≥6 months of experience within the past year working with the REMS program for that medication. Participants were excluded if they were employed by a pharmaceutical manufacturer or the FDA. The focus groups were conducted virtually using an online conferencing service during summer 2021 and were scheduled for 90 minutes. Prior to the focus group, participants received information from the “Goals” and “Summary” tabs of the FDA REMS website10 for the specific medication along with patient/caregiver guides, which were available for clozapine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension. For each focus group, there was a target sample size of 6 to 9 participants. However, there were only 4 participants in the olanzapine for ER injectable suspension focus group, which we believed was due to lower national utilization of this medication. Individuals were only able to participate in 1 focus group, so the unique participant count for all 3 focus groups totaled 17 (Table 1).

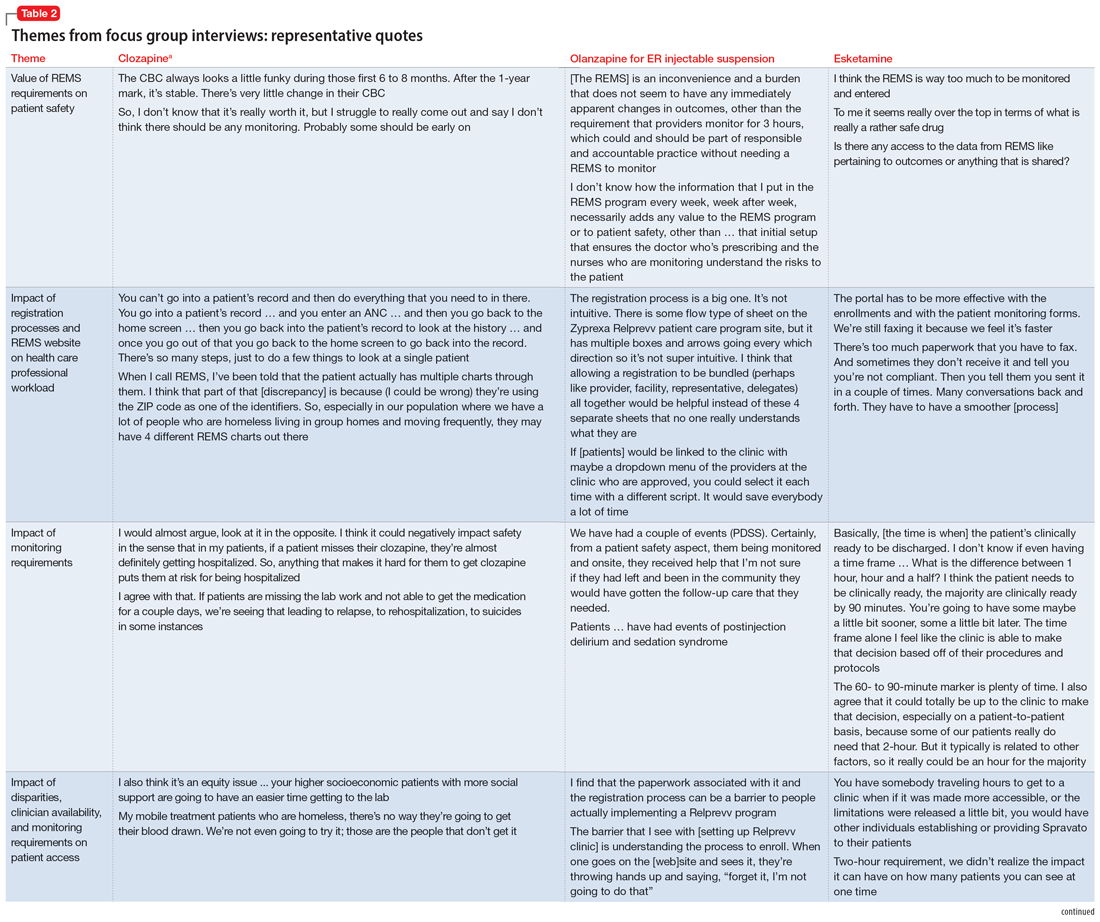

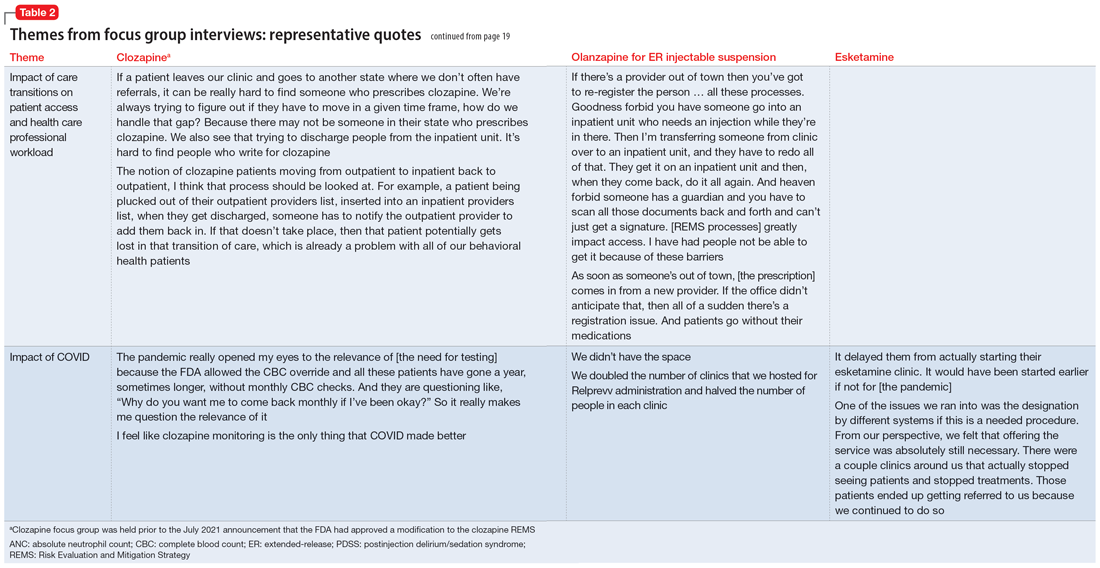

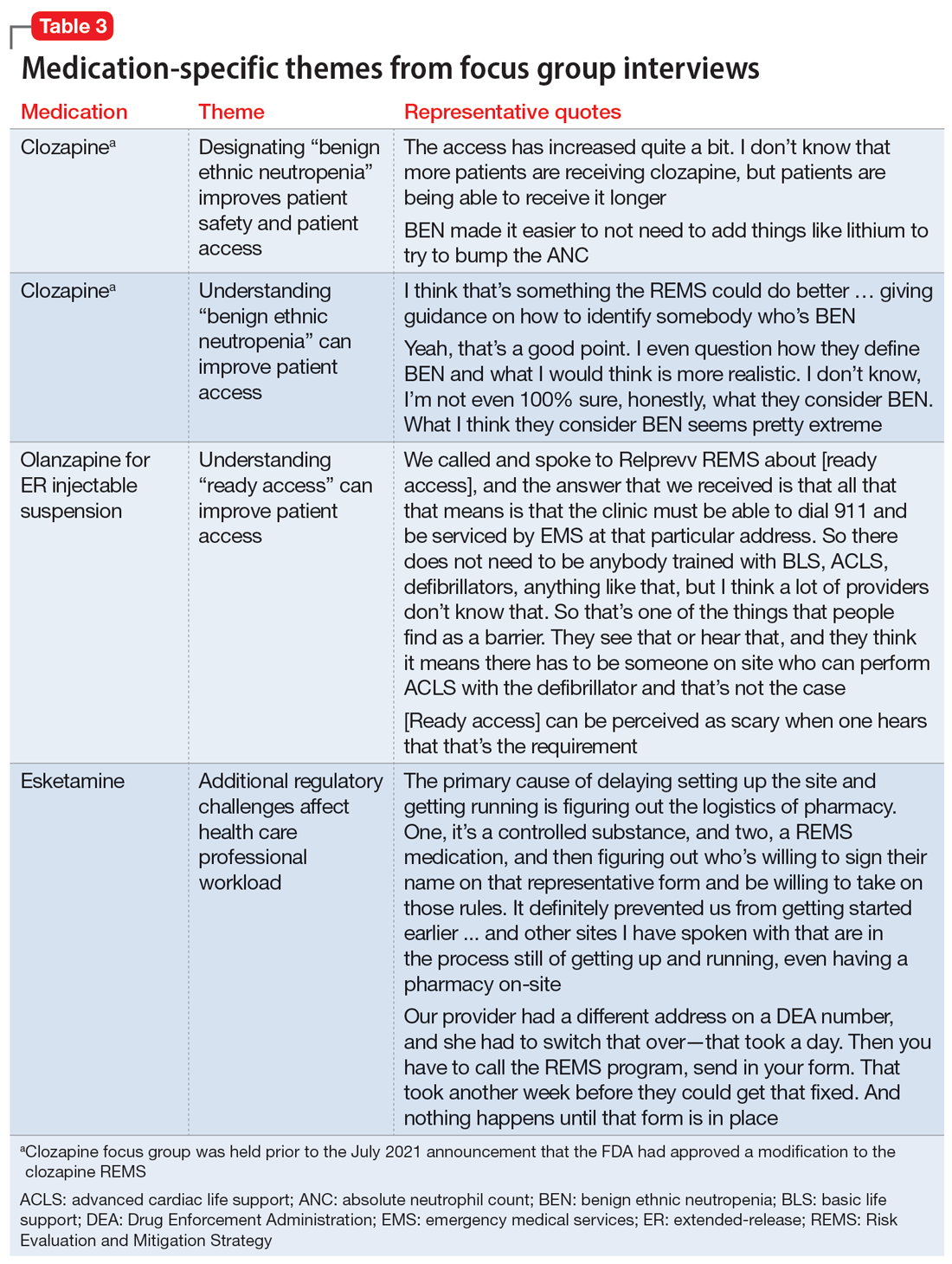

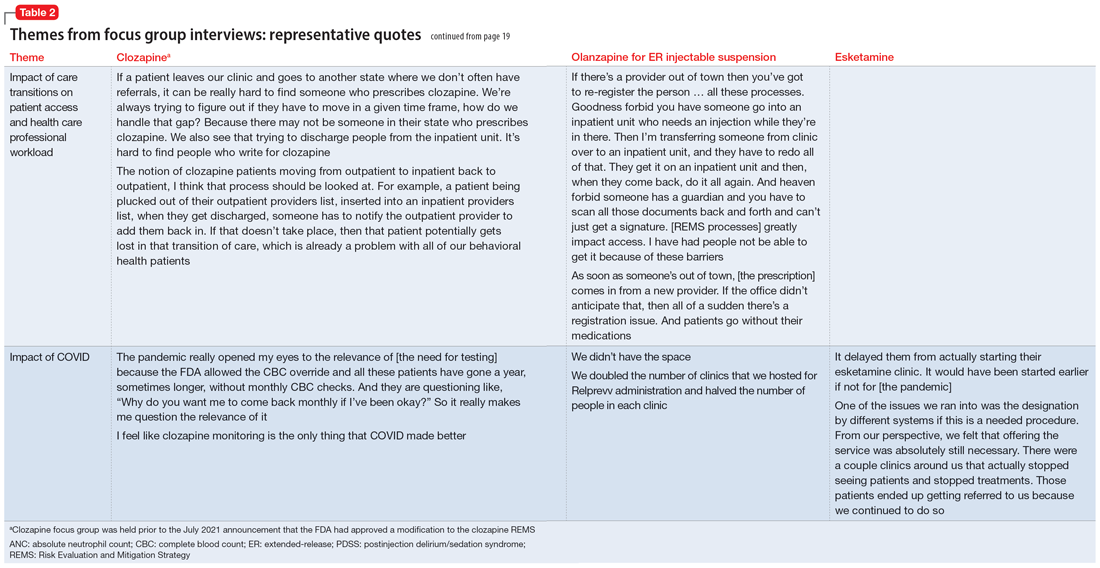

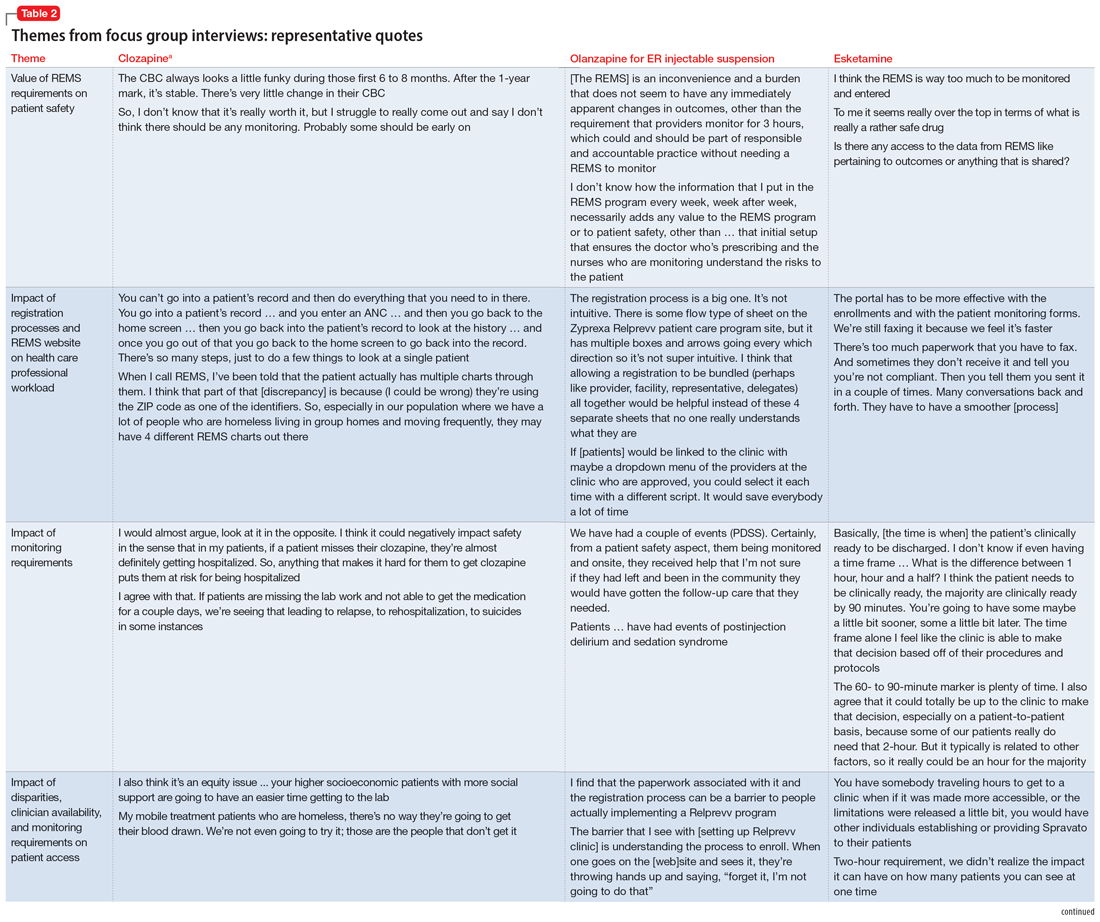

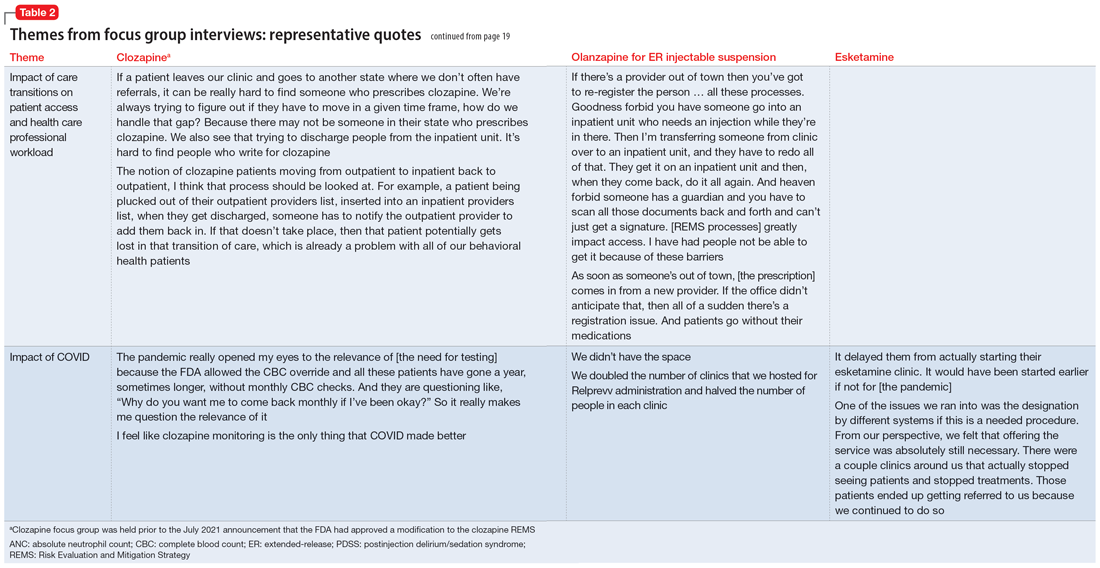

Themes extracted from qualitative analysis of the focus group responses were the value of the REMS programs; registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites; monitoring requirements; care transitions; and COVID considerations (Table 2). While the REMS programs were perceived to increase practitioner and patient awareness of potential harms, discussions centered on the relative cost-to-benefit of the required reporting and other REMS requirements. There were challenges with the registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites that also affected patient care during transitions to different health care settings or clinicians. Patient access was affected by disparities in care related to monitoring requirements and clinician availability.

Continue to: COVID impacted all REMS...

COVID impacted all REMS programs. Physical distancing was an issue for medications that required extensive postadministration monitoring (ie, esketamine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension). Access to laboratory services was an issue for clozapine.

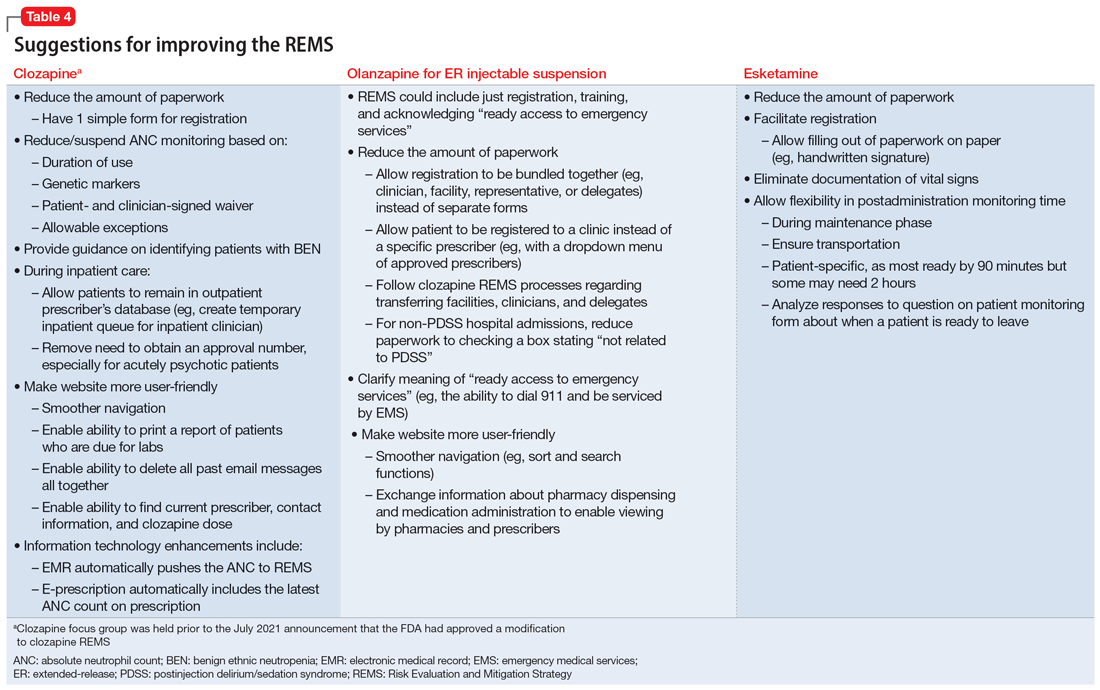

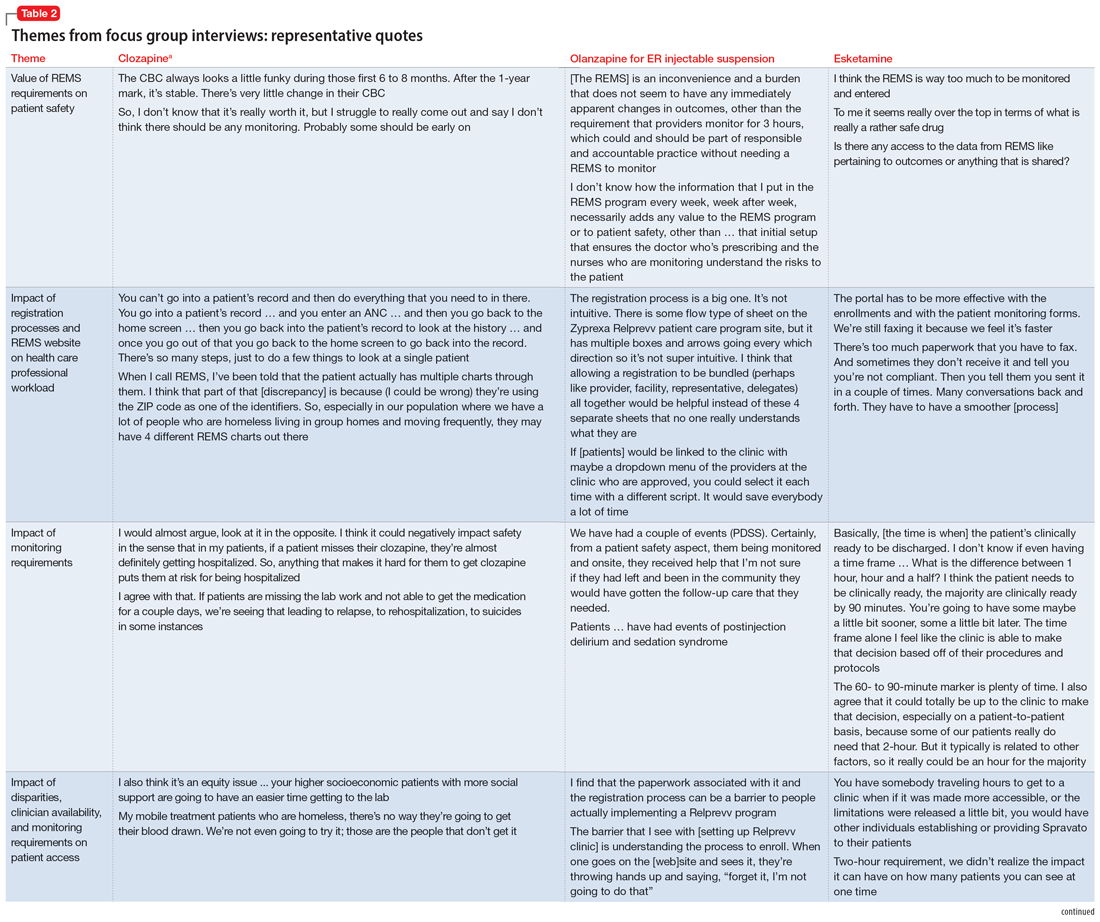

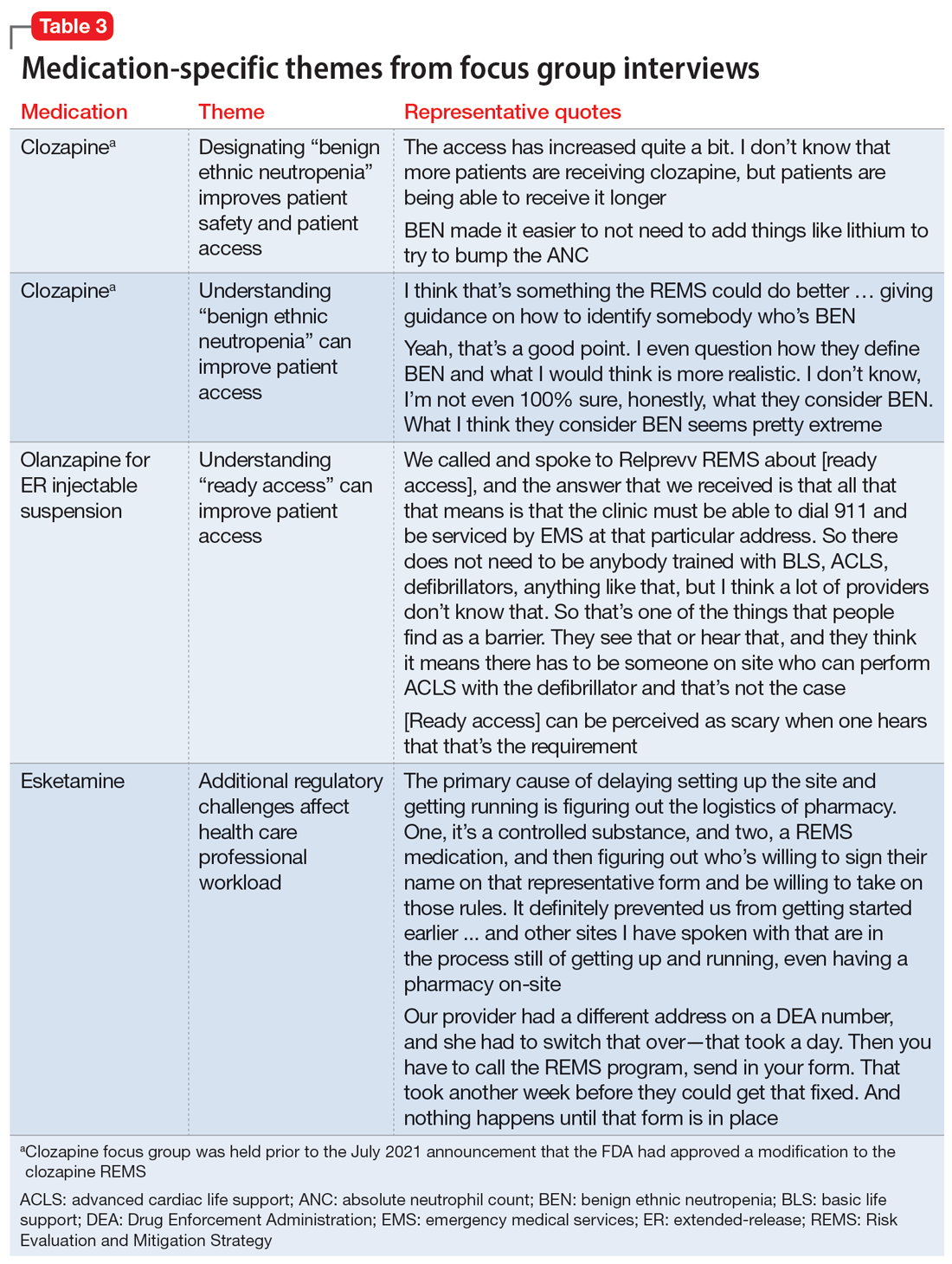

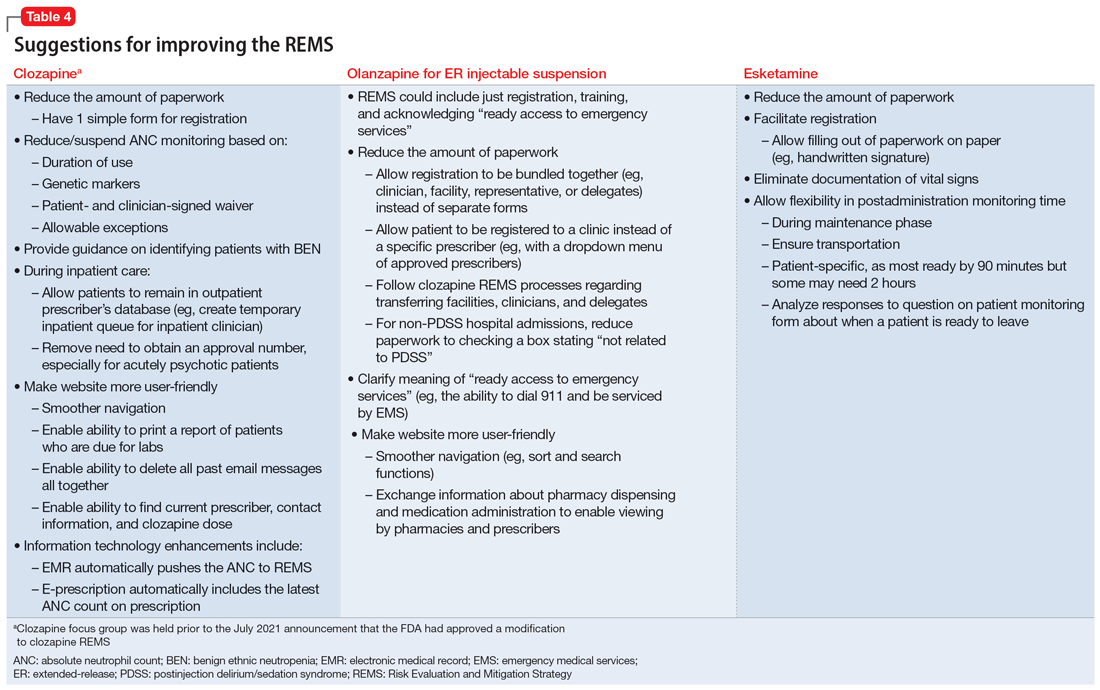

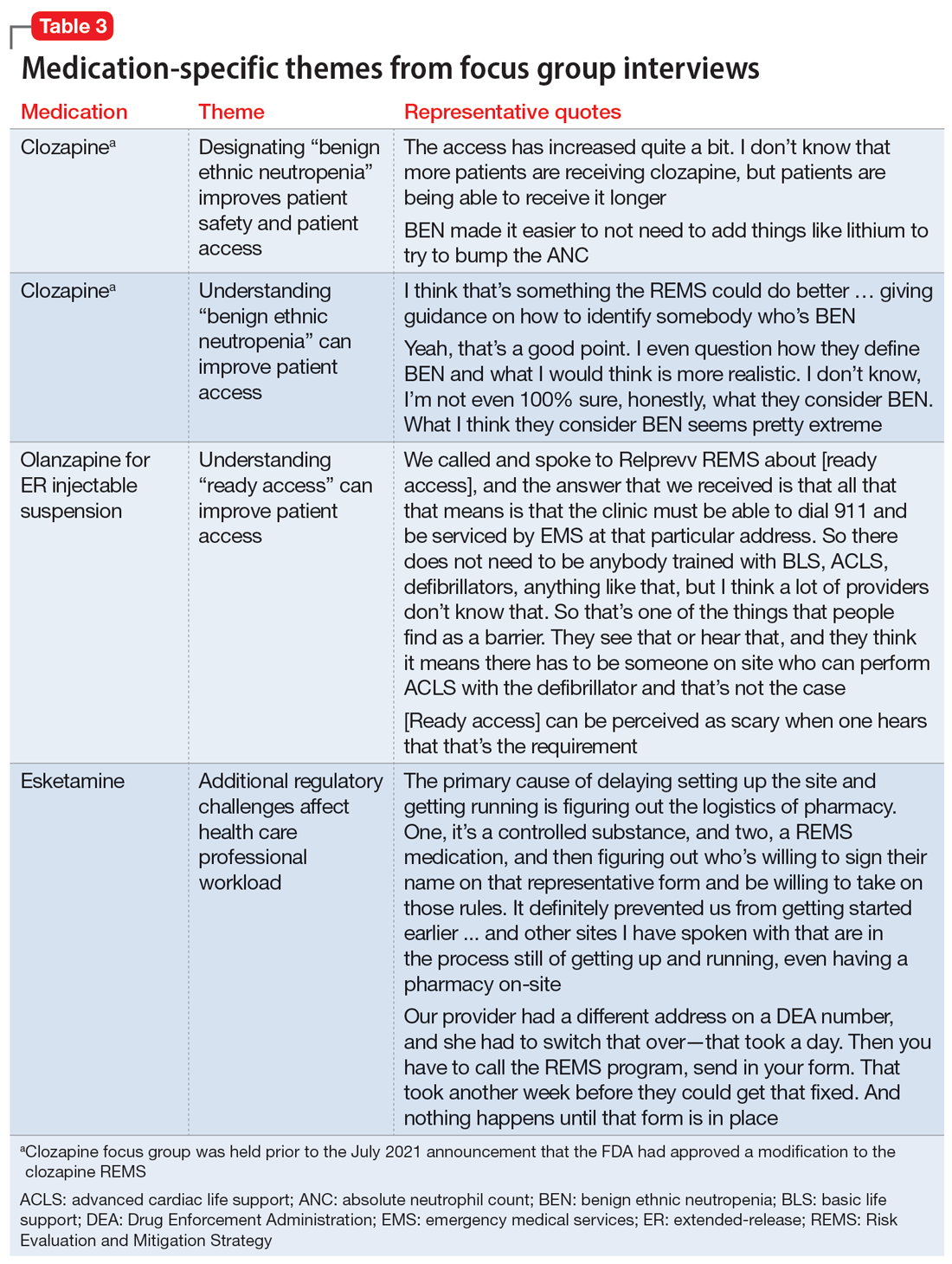

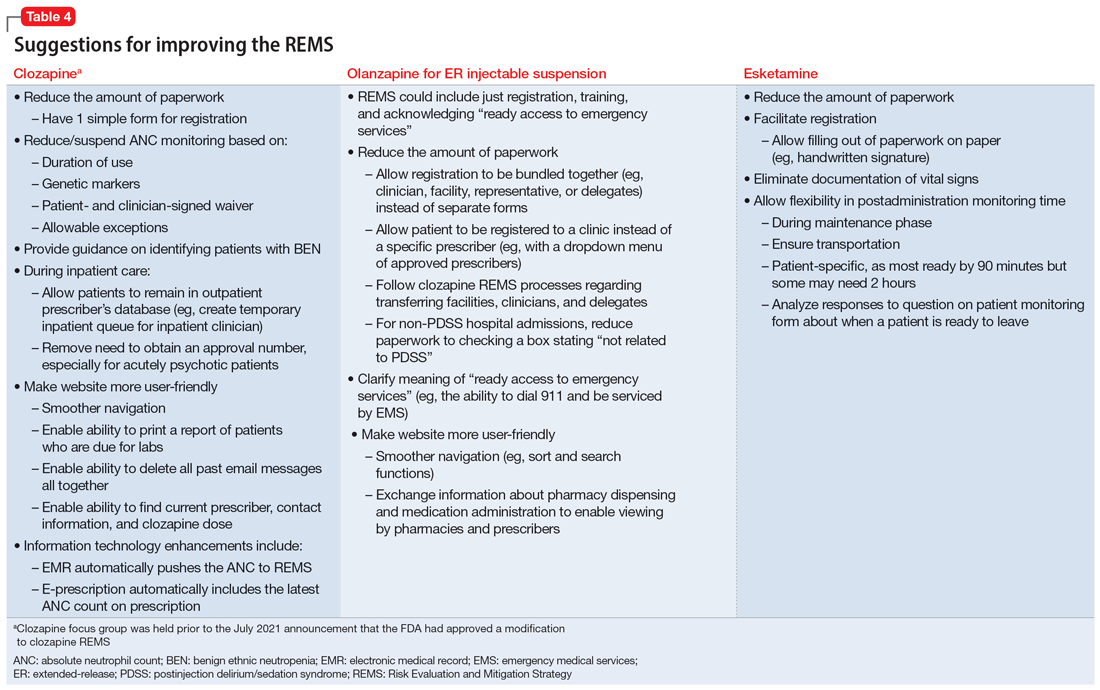

Medication-specific themes are listed in Table 3 and relate to terms and descriptions in the REMS or additional regulatory requirements from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Suggestions for improvement to the REMS are presented in Table 4.

Recommendations for improving REMS

A group consisting of health care professionals, policy experts, and mental health advocates reviewed the information provided by the focus groups and developed the following recommendations.

Overarching recommendations

Each REMS should include a section providing justification for its existence, including a risk analysis of the data regarding the risk the REMS is designed to mitigate. This analysis should be repeated on a regular basis as scientific evidence regarding the risk and its epidemiology evolves. This additional section should also explain how the program requirements of the REMS as implemented (or planned) will achieve the aims of the REMS and weigh the potential benefits of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer vs the potential risks of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer.

Each REMS should have specific quantifiable outcomes. For example, it should specify a reduction in occurrence of the rate of the concerned risk by a specified amount.

Continue to: Ensure adequate...

Ensure adequate stakeholder input during the REMS development and real-world testing in multiple environments before implementing the REMS to identify unanticipated consequences that might impact patient access, patient safety, and health care professional burden. Implementation testing should explore issues such as purchasing and procurement, billing and reimbursement, and relevant factors such as other federal regulations or requirements (eg, the DEA or Medicare).

Ensure harmonization of the REMS forms and processes (eg, initiation and monitoring) for different medications where possible. A prescriber, pharmacist, or system should not face additional barriers to participate in a REMS based on REMS-specific intricacies (ie, prescription systems, data submission systems, or ordering systems). This streamlining will likely decrease clinical inertia to initiate care with the REMS medication, decrease health care professional burden, and improve compliance with REMS requirements.

REMS should anticipate the need for care transitions and employ provisions to ensure seamless care. Considerations should be given to transitions that occur due to:

- Different care settings (eg, inpatient, outpatient, or long-term care)

- Different geographies (eg, patient moves)

- Changes in clinicians, including leaves or absences

- Changes in facilities (eg, pharmacies).

REMS should mirror normal health care professional workflow, including how monitoring data are collected and how and with which frequency pharmacies fill prescriptions.Enhanced information technology to support REMS programs is needed. For example, REMS should be integrated with major electronic patient health record and pharmacy systems to reduce the effort required for clinicians to supply data and automate REMS processes.

For medications that are subject to other agencies and their regulations (eg, the CDC, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or the DEA), REMS should be required to meet all standards of all agencies with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

Continue to: REMS should have a...

REMS should have a standard disclaimer that allows the health care professional to waive certain provisions of the REMS in cases when the specific provisions of the REMS pose a greater risk to the patient than the risk posed by waiving the requirement.

Assure the actions implemented by the industry to meet the requirements for each REMS program are based on peer-reviewed evidence and provide a reasonable expectation to achieve the anticipated benefit.

Ensure that manufacturers make all accumulated REMS data available in a deidentified manner for use by qualified scientific researchers. Additionally, each REMS should have a plan for data access upon initiation and termination of the REMS.

Each REMS should collect data on the performance of the centers and/or personnel who operate the REMS and submit this data for review by qualified outside reviewers. Parameters to assess could include:

- timeliness of response

- timeliness of problem resolution

- data availability and its helpfulness to patient care

- adequacy of resources.

Recommendations for clozapine REMS

These comments relate to the clozapine REMS program prior to the July 2021 announcement that FDA had approved a modification.

Provide a clear definition for “benign ethnic neutropenia.”

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for monitoring. During COVID, the FDA allowed clinicians to “use their best medical judgment in weighing the benefits and risks of continuing treatment in the absence of laboratory testing.”7 This guidance, which allowed flexibility to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring, was perceived as positive and safe. Before the changes in the REMS requirements, patients with benign ethnic neutropenia were restricted from accessing their medication or encountered harm from additional pharmacotherapy to mitigate ANC levels.

Continue to: Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Provide clear explicit instructions on what is required to have “ready access to emergency services.”

Ensure the REMS include patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring (eg, sedation or blood pressure). Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of olanzapine for ER injectable suspension by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness are included in the REMS. How was the 3-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure the REMS requirements allow for seamless care during transitions, particularly when clinicians are on vacation.

Continue to: Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring. Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of esketamine by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness of requirements are included in the REMS. How was the 2-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure that the REMS meet all standards of the DEA, with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

A summary of the findings

Overall, the REMS programs for these 3 medications were positively perceived for raising awareness of safe medication use for clinicians and patients. Monitoring patients for safety concerns is important and REMS requirements provide accountability.

Continue to: The use of a single shared...

The use of a single shared REMS system for documenting requirements for clozapine (compared to separate systems for each manufacturer) was a positive move forward in implementation. The focus group welcomed the increased awareness of benign ethnic neutropenia as a result of this condition being incorporated in the revised monitoring requirements of the clozapine REMS.

Focus group participants raised the issue of the real-world efficiency of the REMS programs (reduced access and increased clinician workload) vs the benefits (patient safety). They noted that excessive workload could lead to clinicians becoming unwilling to use a medication that requires a REMS. Clinician workload may be further compromised when REMS logistics disrupt the normal workflow and transitions of care between clinicians or settings. This latter aspect is of particular concern for clozapine.

The complexities of the registration and reporting system for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension and the lack of clarity about monitoring were noted to have discouraged the opening of treatment sites. This scarcity of sites may make clinicians hesitant to use this medication, and instead opt for alternative treatments in patients who may be appropriate candidates.

There has also been limited growth of esketamine treatment sites, especially in comparison to ketamine treatment sites.11-14 Esketamine is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression in adults and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior. Ketamine is not FDA-approved for treating depression but is being used off-label to treat this disorder.15 The FDA determined that ketamine does not require a REMS to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks for its approved indications as an anesthetic agent, anesthesia-inducing agent, or supplement to anesthesia. Since ketamine has no REMS requirements, there may be a lower burden for its use. Thus, clinicians are treating patients for depression with this medication without needing to comply with a REMS.16

Technology plays a role in workload burden, and integrating health care processes within current workflow systems, such as using electronic patient health records and pharmacy systems, is recommended. The FDA has been exploring technologies to facilitate the completion of REMS requirements, including mandatory education within the prescribers’ and pharmacists’ workflow.17 This is a complex task that requires multiple stakeholders with differing perspectives and incentives to align.

Continue to: The data collected for the REMS...

The data collected for the REMS program belongs to the medication’s manufacturer. Current regulations do not require manufacturers to make this data available to qualified scientific researchers. A regulatory mandate to establish data sharing methods would improve transparency and enhance efforts to better understand the outcomes of the REMS programs.

A few caveats

Both the overarching and medication-specific recommendations were based on a small number of participants’ discussions related to clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine. These recommendations do not include other medications with REMS that are used to treat psychiatric disorders, such as loxapine, buprenorphine ER, and buprenorphine transmucosal products. Larger-scale qualitative and quantitative research is needed to better understand health care professionals’ perspectives. Lastly, some of the recommendations outlined in this article are beyond the current purview or authority of the FDA and may require legislative or regulatory action to implement.

Bottom Line

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs are designed to help reduce the occurrence and/or severity of serious risks or to inform decision-making. However, REMS requirements may adversely impact patient access to certain REMS medications and clinician burden. Health care professionals can provide informed recommendations for improving the REMS programs for clozapine, olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension, and esketamine.

Related Resources

- FDA. Frequently asked questions (FAQs) about REMS. www.fda.gov/drugs/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems/frequently-asked-questions-faqs-about-rems

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine extended-release • Sublocade

Buprenorphine transmucosal • Subutex, Suboxone

Clozapine • Clozaril

Esketamine • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Adasuve

Olanzapine extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Format and Content of a REMS Document. Guidance for Industry. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/77846/download

3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Clozapine. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=RemsDetails.page&REMS=351

4. The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Clozapine underutilization: addressing the barriers. Accessed September 30, 2019. https://nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Assessment%201_Clozapine%20Underutilization.pdf

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA is temporarily exercising enforcement discretion with respect to certain clozapine REMS program requirements to ensure continuity of care for patients taking clozapine. Updated November 22, 2022. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-temporarily-exercising-enforcement-discretion-respect-certain-clozapine-rems-program

6. Tanzi M. REMS issues affect clozapine, isotretinoin. Pharmacy Today. 2022;28(3):49.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA provides update on patient access to certain REMS drugs during COVID-19 public health emergency. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-provides-update-patient-access-certain-rems-drugs-during-covid-19

8. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Spravato (esketamine). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=386

9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), Zyprexa Relprevv (olanzapine). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm?event=IndvRemsDetails.page&REMS=74

10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm

11. Parikh SV, Lopez D, Vande Voort JL, et al. Developing an IV ketamine clinic for treatment-resistant depression: a primer. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2021;51(3):109-124.

12. Dodge D. The ketamine cure. The New York Times. November 4, 2021. Updated November 5, 2021. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/well/ketamine-therapy-depression.html

13. Burton KW. Time for a national ketamine registry, experts say. Medscape. February 15, 2023. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/988310

14. Wilkinson ST, Howard DH, Busch SH. Psychiatric practice patterns and barriers to the adoption of esketamine. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1039-1040. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.10728

15. Wilkinson ST, Toprak M, Turner MS, et al. A survey of the clinical, off-label use of ketamine as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(7):695-696. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17020239

16. Pai SM, Gries JM; ACCP Public Policy Committee. Off-label use of ketamine: a challenging drug treatment delivery model with an inherently unfavorable risk-benefit profile. J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;62(1):10-13. doi:10.1002/jcph.1983

17. Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) Integration. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://confluence.hl7.org/display/COD/Risk+Evaluation+and+Mitigation+Strategies+%28REMS%29+Integration

A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) is a drug safety program the FDA can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks (Box1). The FDA may require medication guides, patient package inserts, communication plans for health care professionals, and/or certain packaging and safe disposal technologies for medications that pose a serious risk of abuse or overdose. The FDA may also require elements to assure safe use and/or an implementation system be included in the REMS. Pharmaceutical manufacturers then develop a proposed REMS for FDA review.2 If the FDA approves the proposed REMS, the manufacturer is responsible for implementing the REMS requirements.

Box

There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding psychiatry, the branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental illness. Some of the most common myths include:

The FDA provides this description of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS):

“A [REMS] is a drug safety program that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can require for certain medications with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh its risks. REMS are designed to reinforce medication use behaviors and actions that support the safe use of that medication. While all medications have labeling that informs health care stakeholders about medication risks, only a few medications require a REMS. REMS are not designed to mitigate all the adverse events of a medication, these are communicated to health care providers in the medication’s prescribing information. Rather, REMS focus on preventing, monitoring and/or managing a specific serious risk by informing, educating and/or reinforcing actions to reduce the frequency and/or severity of the event.”1

The REMS program for clozapine3 has been the subject of much discussion in the psychiatric community. The adverse impact of the 2015 update to the clozapine REMS program was emphasized at meetings of both the American Psychiatric Association and the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. A white paper published by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors shortly after the 2015 update concluded, “clozapine is underused due to a variety of barriers related to the drug and its properties, the health care system, regulatory requirements, and reimbursement issues.”4 After an update to the clozapine REMS program in 2021, the FDA temporarily suspended enforcement of certain requirements due to concerns from health care professionals about patient access to the medication because of problems with implementing the clozapine REMS program.5,6 In November 2022, the FDA issued a second announcement of enforcement discretion related to additional requirements of the REMS program.5 The FDA had previously announced a decision to not take action regarding adherence to REMS requirements for certain laboratory tests in March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic.7

REMS programs for other psychiatric medications may also present challenges. The REMS programs for esketamine8 and olanzapine for extended-release (ER) injectable suspension9 include certain risks that require postadministration monitoring. Some facilities have had to dedicate additional space and clinician time to ensure REMS requirements are met.

To further understand health care professionals’ perspectives regarding the value and burden of these REMS programs, a collaborative effort of the University of Maryland (College Park and Baltimore campuses) Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation with the FDA was undertaken. The REMS for clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine were examined to develop recommendations for improving patient access while ensuring safe medication use and limiting the impact on health care professionals.

Assessing the REMS programs

Focus groups were held with health care professionals nominated by professional organizations to gather their perspectives on the REMS requirements. There was 1 focus group for each of the 3 medications. A facilitator’s guide was developed that contained the details of how to conduct the focus group along with the medication-specific questions. The questions were based on the REMS requirements as of May 2021 and assessed the impact of the REMS on patient safety, patient access, and health care professional workload; effects from the COVID-19 pandemic; and suggestions to improve the REMS programs. The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board reviewed the materials and processes and made the determination of exempt.

Health care professionals were eligible to participate in a focus group if they had ≥1 year of experience working with patients who use the specific medication and ≥6 months of experience within the past year working with the REMS program for that medication. Participants were excluded if they were employed by a pharmaceutical manufacturer or the FDA. The focus groups were conducted virtually using an online conferencing service during summer 2021 and were scheduled for 90 minutes. Prior to the focus group, participants received information from the “Goals” and “Summary” tabs of the FDA REMS website10 for the specific medication along with patient/caregiver guides, which were available for clozapine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension. For each focus group, there was a target sample size of 6 to 9 participants. However, there were only 4 participants in the olanzapine for ER injectable suspension focus group, which we believed was due to lower national utilization of this medication. Individuals were only able to participate in 1 focus group, so the unique participant count for all 3 focus groups totaled 17 (Table 1).

Themes extracted from qualitative analysis of the focus group responses were the value of the REMS programs; registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites; monitoring requirements; care transitions; and COVID considerations (Table 2). While the REMS programs were perceived to increase practitioner and patient awareness of potential harms, discussions centered on the relative cost-to-benefit of the required reporting and other REMS requirements. There were challenges with the registration/enrollment processes and REMS websites that also affected patient care during transitions to different health care settings or clinicians. Patient access was affected by disparities in care related to monitoring requirements and clinician availability.

Continue to: COVID impacted all REMS...

COVID impacted all REMS programs. Physical distancing was an issue for medications that required extensive postadministration monitoring (ie, esketamine and olanzapine for ER injectable suspension). Access to laboratory services was an issue for clozapine.

Medication-specific themes are listed in Table 3 and relate to terms and descriptions in the REMS or additional regulatory requirements from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Suggestions for improvement to the REMS are presented in Table 4.

Recommendations for improving REMS

A group consisting of health care professionals, policy experts, and mental health advocates reviewed the information provided by the focus groups and developed the following recommendations.

Overarching recommendations

Each REMS should include a section providing justification for its existence, including a risk analysis of the data regarding the risk the REMS is designed to mitigate. This analysis should be repeated on a regular basis as scientific evidence regarding the risk and its epidemiology evolves. This additional section should also explain how the program requirements of the REMS as implemented (or planned) will achieve the aims of the REMS and weigh the potential benefits of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer vs the potential risks of the REMS requirements as implemented (or planned) by the manufacturer.

Each REMS should have specific quantifiable outcomes. For example, it should specify a reduction in occurrence of the rate of the concerned risk by a specified amount.

Continue to: Ensure adequate...

Ensure adequate stakeholder input during the REMS development and real-world testing in multiple environments before implementing the REMS to identify unanticipated consequences that might impact patient access, patient safety, and health care professional burden. Implementation testing should explore issues such as purchasing and procurement, billing and reimbursement, and relevant factors such as other federal regulations or requirements (eg, the DEA or Medicare).

Ensure harmonization of the REMS forms and processes (eg, initiation and monitoring) for different medications where possible. A prescriber, pharmacist, or system should not face additional barriers to participate in a REMS based on REMS-specific intricacies (ie, prescription systems, data submission systems, or ordering systems). This streamlining will likely decrease clinical inertia to initiate care with the REMS medication, decrease health care professional burden, and improve compliance with REMS requirements.

REMS should anticipate the need for care transitions and employ provisions to ensure seamless care. Considerations should be given to transitions that occur due to:

- Different care settings (eg, inpatient, outpatient, or long-term care)

- Different geographies (eg, patient moves)

- Changes in clinicians, including leaves or absences

- Changes in facilities (eg, pharmacies).

REMS should mirror normal health care professional workflow, including how monitoring data are collected and how and with which frequency pharmacies fill prescriptions.Enhanced information technology to support REMS programs is needed. For example, REMS should be integrated with major electronic patient health record and pharmacy systems to reduce the effort required for clinicians to supply data and automate REMS processes.

For medications that are subject to other agencies and their regulations (eg, the CDC, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or the DEA), REMS should be required to meet all standards of all agencies with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

Continue to: REMS should have a...

REMS should have a standard disclaimer that allows the health care professional to waive certain provisions of the REMS in cases when the specific provisions of the REMS pose a greater risk to the patient than the risk posed by waiving the requirement.

Assure the actions implemented by the industry to meet the requirements for each REMS program are based on peer-reviewed evidence and provide a reasonable expectation to achieve the anticipated benefit.

Ensure that manufacturers make all accumulated REMS data available in a deidentified manner for use by qualified scientific researchers. Additionally, each REMS should have a plan for data access upon initiation and termination of the REMS.

Each REMS should collect data on the performance of the centers and/or personnel who operate the REMS and submit this data for review by qualified outside reviewers. Parameters to assess could include:

- timeliness of response

- timeliness of problem resolution

- data availability and its helpfulness to patient care

- adequacy of resources.

Recommendations for clozapine REMS

These comments relate to the clozapine REMS program prior to the July 2021 announcement that FDA had approved a modification.

Provide a clear definition for “benign ethnic neutropenia.”

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for monitoring. During COVID, the FDA allowed clinicians to “use their best medical judgment in weighing the benefits and risks of continuing treatment in the absence of laboratory testing.”7 This guidance, which allowed flexibility to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring, was perceived as positive and safe. Before the changes in the REMS requirements, patients with benign ethnic neutropenia were restricted from accessing their medication or encountered harm from additional pharmacotherapy to mitigate ANC levels.

Continue to: Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Recommendations for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension REMS

Provide clear explicit instructions on what is required to have “ready access to emergency services.”

Ensure the REMS include patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring (eg, sedation or blood pressure). Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of olanzapine for ER injectable suspension by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness are included in the REMS. How was the 3-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure the REMS requirements allow for seamless care during transitions, particularly when clinicians are on vacation.

Continue to: Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Recommendations for esketamine REMS

Ensure the REMS includes patient-specific adjustments to allow flexibility for postadministration monitoring. Specific patient groups may have differential access to certain types of facilities, transportation, or other resources. For example, consider the administration of esketamine by a mobile treatment team with an adequate protocol (eg, via videoconferencing or phone calls).

Ensure actions with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating efficacy/effectiveness of requirements are included in the REMS. How was the 2-hour cut-point determined? Has it been reevaluated?

Ensure that the REMS meet all standards of the DEA, with a single system that accommodates normal health care professional workflow.

A summary of the findings

Overall, the REMS programs for these 3 medications were positively perceived for raising awareness of safe medication use for clinicians and patients. Monitoring patients for safety concerns is important and REMS requirements provide accountability.

Continue to: The use of a single shared...

The use of a single shared REMS system for documenting requirements for clozapine (compared to separate systems for each manufacturer) was a positive move forward in implementation. The focus group welcomed the increased awareness of benign ethnic neutropenia as a result of this condition being incorporated in the revised monitoring requirements of the clozapine REMS.

Focus group participants raised the issue of the real-world efficiency of the REMS programs (reduced access and increased clinician workload) vs the benefits (patient safety). They noted that excessive workload could lead to clinicians becoming unwilling to use a medication that requires a REMS. Clinician workload may be further compromised when REMS logistics disrupt the normal workflow and transitions of care between clinicians or settings. This latter aspect is of particular concern for clozapine.

The complexities of the registration and reporting system for olanzapine for ER injectable suspension and the lack of clarity about monitoring were noted to have discouraged the opening of treatment sites. This scarcity of sites may make clinicians hesitant to use this medication, and instead opt for alternative treatments in patients who may be appropriate candidates.

There has also been limited growth of esketamine treatment sites, especially in comparison to ketamine treatment sites.11-14 Esketamine is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression in adults and for depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior. Ketamine is not FDA-approved for treating depression but is being used off-label to treat this disorder.15 The FDA determined that ketamine does not require a REMS to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks for its approved indications as an anesthetic agent, anesthesia-inducing agent, or supplement to anesthesia. Since ketamine has no REMS requirements, there may be a lower burden for its use. Thus, clinicians are treating patients for depression with this medication without needing to comply with a REMS.16

Technology plays a role in workload burden, and integrating health care processes within current workflow systems, such as using electronic patient health records and pharmacy systems, is recommended. The FDA has been exploring technologies to facilitate the completion of REMS requirements, including mandatory education within the prescribers’ and pharmacists’ workflow.17 This is a complex task that requires multiple stakeholders with differing perspectives and incentives to align.

Continue to: The data collected for the REMS...

The data collected for the REMS program belongs to the medication’s manufacturer. Current regulations do not require manufacturers to make this data available to qualified scientific researchers. A regulatory mandate to establish data sharing methods would improve transparency and enhance efforts to better understand the outcomes of the REMS programs.

A few caveats

Both the overarching and medication-specific recommendations were based on a small number of participants’ discussions related to clozapine, olanzapine for ER injectable suspension, and esketamine. These recommendations do not include other medications with REMS that are used to treat psychiatric disorders, such as loxapine, buprenorphine ER, and buprenorphine transmucosal products. Larger-scale qualitative and quantitative research is needed to better understand health care professionals’ perspectives. Lastly, some of the recommendations outlined in this article are beyond the current purview or authority of the FDA and may require legislative or regulatory action to implement.

Bottom Line

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs are designed to help reduce the occurrence and/or severity of serious risks or to inform decision-making. However, REMS requirements may adversely impact patient access to certain REMS medications and clinician burden. Health care professionals can provide informed recommendations for improving the REMS programs for clozapine, olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension, and esketamine.

Related Resources

- FDA. Frequently asked questions (FAQs) about REMS. www.fda.gov/drugs/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems/frequently-asked-questions-faqs-about-rems

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine extended-release • Sublocade

Buprenorphine transmucosal • Subutex, Suboxone

Clozapine • Clozaril

Esketamine • Spravato

Ketamine • Ketalar

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Adasuve

Olanzapine extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv