User login

Pharmacogenetic testing: Navigating through the confusion

Mr. J, age 30, a Black man with major depressive disorder (MDD), has been your patient for the past year. At the time of his diagnosis, Mr. J received sertraline, 100 mg/d, but had little to no improvement. During the past year, he received trials of citalopram and paroxetine, but they were not effective for his recurrent depressive symptoms and/or resulted in significant adverse effects.

During a recent visit, Mr. J asks you about “the genetic tests that help determine which medications will work.” He mentions that his brother had this testing done and that it had “worked for him,” but offers no other details. You research the different testing panels to see which test you might use. After a brief online review, you identify at least 4 different products, and are not sure which test—if any—you should consider.

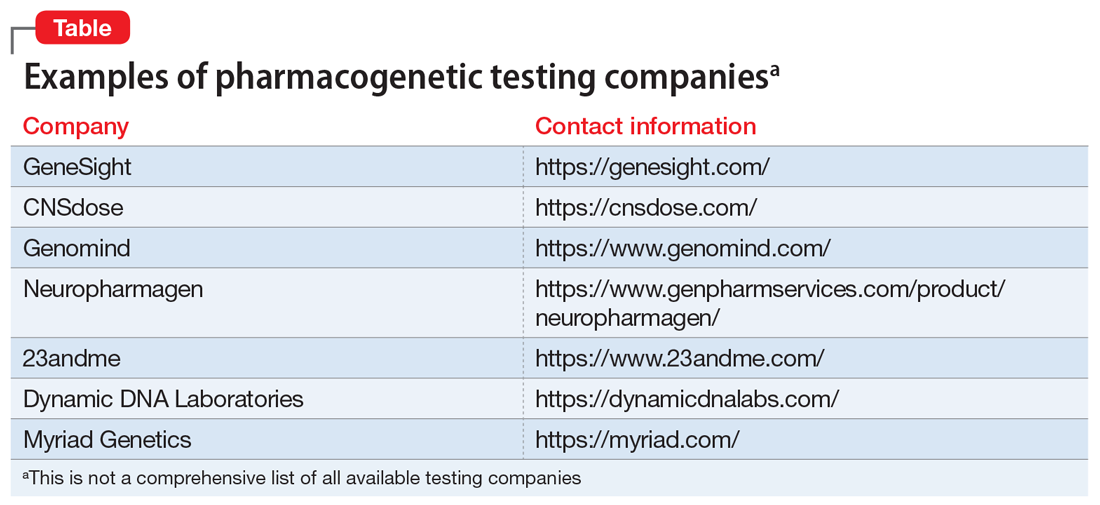

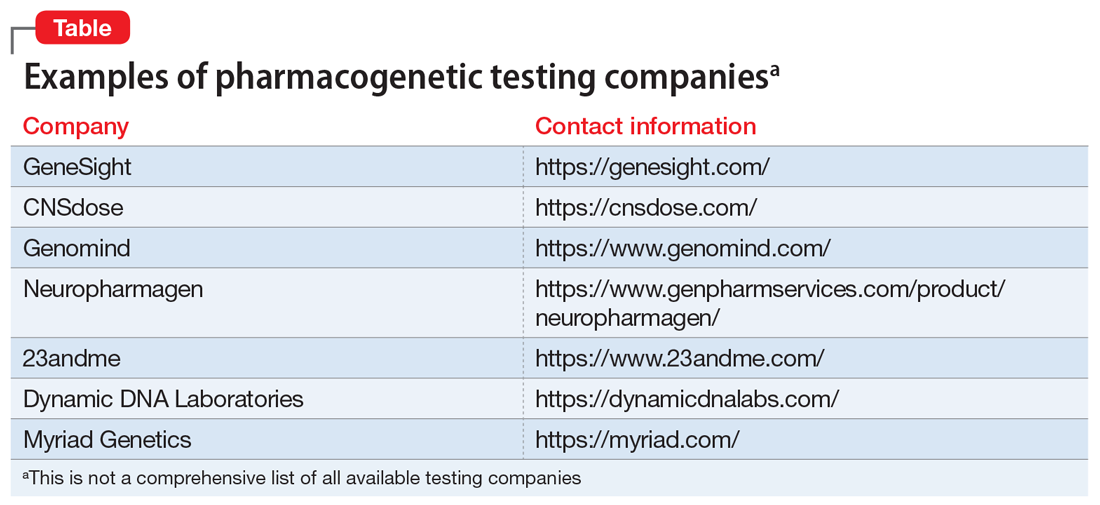

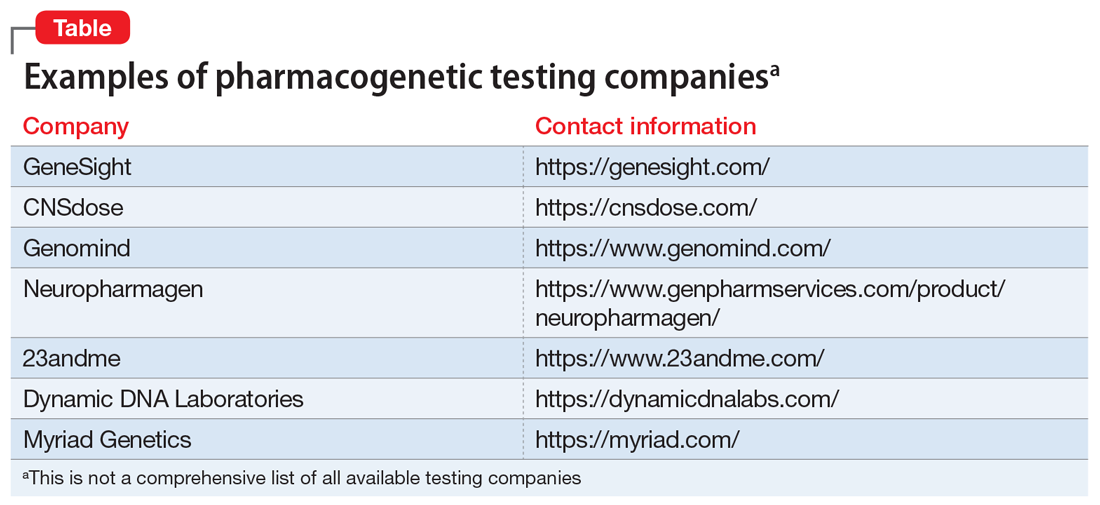

During the last few years, there has been a rise in commercial pharmacogenetic testing options, including tests available to clinicians at academic medical centers as well as direct-to-consumer testing (Table). Clinician and patient interest regarding pharmacogenetic testing in practice is often followed by the question, “Which test is best?” Although this is a logical question, providing an answer is multifactorial.1-3 Because none of the currently available tests have been compared in head-to-head clinical trials, it is nearly impossible to identify the “best” test.

In this article, we focus on the evidence-based principles that clinicians should consider when adopting pharmacogenetic testing in their practice. We discuss which genes are of most interest when prescribing psychotropic medications, the value of decision support tools, cost considerations, and patient education regarding this type of testing.

Which genes and variants should be tested?

The genes relevant to medication treatment outcomes can be broadly classified into those with pharmacokinetic vs pharmacodynamic effects. Pharmacogenes, such as those coding for the drug-metabolizing enzymes cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)2B1, may alter the rate at which medications are metabolized, thus varying the serum drug concentration across patients. Variants that impact the function of these enzymes are considered pharmacokinetic. Up to 40% of the variance in patients’ response to antidepressants may be due to variations in the pharmacokinetic genes.4 Alternatively, pharmacodynamic pharmacogenes impact drug action and therefore may affect the degree of receptor activation at a given drug concentration, overall drug efficacy, and/or the occurrence of medication sensitivity. These pharmacogenes may include:

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

- catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)

- human leukocyte antigens A (HLA-A)

- serotonin receptor subtype 2 (HTR2)

- serotonin receptor subtype 2C (HTR2C)

- opioid receptor mu 1 (OPRM1)

- solute carrier family 6 member 4 (SLC6A4).

In articles previously published in

Currently, there is no standardization among commercial pharmacogenetic tests on:

- which genes to test

- which variants specific to a gene need to be included

- how the genetic data is translated to phenotype

- how the phenotype is translated to a treatment recommendation.

Continue to: Due to these factors...

Due to these factors, the FDA has advised clinicians to consult the dosing recommendations provided in a medication’s package insert for information regarding how genetic information should be used in making treatment decisions.2

The value of decision support tools

Researchers have assessed how various manufacturers’ decision support tools (DSTs) (ie, the reports the commercial testing companies send to the clinician who orders the test) agree on genotypes, predicted phenotypes, and medication recommendations.4 Overall, this research found varying levels of disagreement in the medication recommendations of the testing panels they studied, which indicates that not all tests are equivalent or interchangeable.4 Of the actionable recommendations for antidepressants, 16% were conflicting; the recommendations for fluoxetine and imipramine were most frequently in disagreement.4 Similarly, 20% of the actionable antipsychotic advice was conflicting, with the recommendations for aripiprazole and clozapine most frequently in disagreement.4 Researchers also reported a situation in which 4 testing panels agreed on the patient’s phenotyping status for CYP2C19, but the dosing recommendations provided for the CYP2C19 substrate, amitriptyline, differed.4 Thus, it is understandable why DSTs can result in confusion, and why clinicians should use testing panels with recommendations that best align with their individual practices, their patient’s needs, and FDA information.

Additionally, while the genes included on these panels vary, these testing panels also may not evaluate the same variants within a specific gene. These differences may impact the patient’s reported phenotypes and medication recommendations across DSTs. For example, the FDA has recommended HLA gene testing prior to prescribing carbamazepine. However, few of the available tests may include the HLA-B*15:02 variant, which has been associated with carbamazepine-induced severe cutaneous reactions in patients of Asian descent, and fewer may include the HLA-A*31:01 variant, for which testing is recommended prior to prescribing carbamazepine in patients of Caucasian descent.4 Additionally, some of the CYP enzymes—such as CYP2D6*17 and CYP2C19*3 variants, which may be more common in certain populations of patients who are members of ethnic or racial minority groups—may not be consistently included in the various panels. Thus, before deciding on a specific test, clinicians should understand which gene variants are relevant to their patients with regard to race and ethnicity, and key variants for specific medications. Clinicians should refer to FDA guidance and the Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines to determine the appropriate interpretations of genetic test results.1,2

Despite the disagreement in recommendations from the various testing companies, DSTs are useful and have been shown to facilitate implementation of relevant psychopharmacology dosing guidelines, assist in identifying optimal medication therapy, and improve patient outcomes. A recently published meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacogenetic testing found that DSTs improved symptom remission among individuals with MDD by 70%.5 This suggests that pharmacogenetic-guided DSTs may provide superior treatment compared with treatment for DSTs were not used. However, the RCTs in this meta-analysis only included patients who had previously failed an antidepressant trial.5 Therefore, it is currently unknown at what point in care DSTs should be used, and whether they would be more beneficial if they are used when starting a new therapy, or after several trials have failed.

Consider the cost

The cost and availability of pharmacogenetic testing can be an issue when making treatment decisions, and such testing may not be covered by a patient’s insurance plan. Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that Medicare would cover FDA-approved genomic tests that encompass broad gene panels if the evidence supports their use. Similarly, commercial insurers such as UnitedHealthcare have begun to cover some pharmacogenetic tests.6 Medicare or Medicaid plans cover some testing panels’ costs and patients do not incur any out-of-pocket costs; however, some private insurance companies require patients to pay at least a portion of the cost, and many companies offer financial assistance for patients based on income and other factors. Although financial coverage for testing has improved, patients may still face out-of-pocket costs; therefore, clinicians may need to weigh the benefits of pharmacogenetic testing vs its cost.7 Clinicians should also determine what timeline best suits their patient’s financial and clinical needs, and test accordingly.

Continue to: Patient education is critical

Patient education is critical

Although the benefits of using pharmacogenetic testing information when making certain treatment decisions is promising, it is important for both patients and clinicians to understand that test results do not always change therapy. A study on the impact of pharmacogenetic testing on clinical outcomes of patients with MDD found that 79% of patients were already prescribed medications that aligned with recommendations.8 Therefore, switching medications based on the test results of a patient who is doing well clinically is not recommended. However, DSTs may help with clinical decisions for ambiguous cases. For example, if a patient has a genotype and/or phenotype that aligns with medication recommendations, the DST might not be able to identify a better medication to use, but may be able to recommend dosing guidance to improve the tolerability of the patient’s current therapy.6 It is also important to understand that the results of such testing may have a broader use beyond the initial reason for obtaining testing, such as when prescribing a common blood thinner such as warfarin or clopidogrel. However, for many of the pharmacodynamic genes that are included in these panels, their use beyond the treatment of depression may be limited because outcome studies for pharmacodynamic pharmacogenes may vary based on psychiatric diagnosis. Regardless, it may be beneficial to securely save and store patient test results in a standardized place within the medical record for future use.

CASE CONTINUED

You work with Mr. J to help him understand the benefits and limitations associated with pharmacogenetic testing. Assuming Mr. J is comfortable with the costs of obtaining testing, you contact the testing companies you identified to determine the specific pharmacogene variants included on each of these panels, and which would be the most appropriate given his race. If the decision is made to order the testing, provide Mr. J with a copy of his testing report so that he can use this information should he need any additional pharmacotherapy in the future, and also maintain a copy in his patient records using a standardized location for easy future access. If Mr. J is not comfortable with the costs associated with the testing, find out which medication his brother is currently receiving for treatment; this information may help identify a treatment plan for Mr. J.

Impact on practice

As psychiatry continues to gain experience in using pharmacogenetic testing and DSTs to help guide treatments for depression and other disorders, clinicians need to learn about these tools and how to use an evidence-based approach to best implement them in their practice. Many academic medical centers have developed continuing education programs or consult services to help with this.9,10 Just as the choice of which medication to use may be based partly on clinician experience, so too may be which pharmacogenetic test to use.

Bottom Line

Pharmacogenetic tests have not been examined in head-to-head clinical trials, which makes it nearly impossible to identify which test is best to use. Although the testing companies’ decision support tools (DSTs) often disagree in their recommendations, research has shown that using DSTs can facilitate implementation of relevant psychopharmacology dosing guidelines, assist in identifying optimal medication therapy, and improve patient outcomes. Clinicians should use testing panels with recommendations that best align with their individual practices, their patient’s needs, and FDA information.

Related Resources

- PGx Gene-specific information tables. www.pharmgkb.org/page/pgxGeneRef

- Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Imipramine • Tofranil

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Warfarin • Coumadin, Jantoven

1. Ellingrod, VL. Using pharmacogenetics guidelines when prescribing: what’s available. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):43-46.

2. Ellingrod VL. Pharmacogenomics testing: what the FDA says. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):29-33.

3. Ramsey LB. Pharmacogenetic testing in children: what to test and how to use it. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):30-36.

4. Bousman CA, Dunlop BW. Genotype, phenotype, and medication recommendation agreement among commercial pharmacogenetic-based decision support tools. The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 2018;18(5):613-622. doi:10.1038/s41397-018-0027-3

5. Bousman CA, Arandjelovic K, Mancuso SG, et al. Pharmacogenetic tests and depressive symptom remission: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20(1). doi:10.2217/pgs-2018-0142

6. Nicholson WT, Formea CM, Matey ET, et al. Considerations when applying pharmacogenomics to your practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(1);218-230. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.011

7. Krebs K, Milani L. Translating pharmacogenomics into clinical decisions: do not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Human Genomics. 2019;13(1). doi:10.1186/s40246-019-0229-z

8. Greden JF, Parikh S, Rothschild AJ, et al. Impact of pharmacogenomics on clinical outcomes in major depressive disorder in the GUIDED trial: a large, patient- and rater-blinded, randomized, controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;111;59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.01.003

9. Haga SB. Integrating pharmacogenetic testing into primary care. Expert Review of Precision Medicine and Drug Development. 2017;2(6):327-336. doi:10.1080/23808993.2017.1398046

10. Ward KM, Taubman DS, Pasternak AL, et al. Teaching psychiatric pharmacogenomics effectively: evaluation of a novel interprofessional online course. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2021; 4:176-183.

Mr. J, age 30, a Black man with major depressive disorder (MDD), has been your patient for the past year. At the time of his diagnosis, Mr. J received sertraline, 100 mg/d, but had little to no improvement. During the past year, he received trials of citalopram and paroxetine, but they were not effective for his recurrent depressive symptoms and/or resulted in significant adverse effects.

During a recent visit, Mr. J asks you about “the genetic tests that help determine which medications will work.” He mentions that his brother had this testing done and that it had “worked for him,” but offers no other details. You research the different testing panels to see which test you might use. After a brief online review, you identify at least 4 different products, and are not sure which test—if any—you should consider.

During the last few years, there has been a rise in commercial pharmacogenetic testing options, including tests available to clinicians at academic medical centers as well as direct-to-consumer testing (Table). Clinician and patient interest regarding pharmacogenetic testing in practice is often followed by the question, “Which test is best?” Although this is a logical question, providing an answer is multifactorial.1-3 Because none of the currently available tests have been compared in head-to-head clinical trials, it is nearly impossible to identify the “best” test.

In this article, we focus on the evidence-based principles that clinicians should consider when adopting pharmacogenetic testing in their practice. We discuss which genes are of most interest when prescribing psychotropic medications, the value of decision support tools, cost considerations, and patient education regarding this type of testing.

Which genes and variants should be tested?

The genes relevant to medication treatment outcomes can be broadly classified into those with pharmacokinetic vs pharmacodynamic effects. Pharmacogenes, such as those coding for the drug-metabolizing enzymes cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)2B1, may alter the rate at which medications are metabolized, thus varying the serum drug concentration across patients. Variants that impact the function of these enzymes are considered pharmacokinetic. Up to 40% of the variance in patients’ response to antidepressants may be due to variations in the pharmacokinetic genes.4 Alternatively, pharmacodynamic pharmacogenes impact drug action and therefore may affect the degree of receptor activation at a given drug concentration, overall drug efficacy, and/or the occurrence of medication sensitivity. These pharmacogenes may include:

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

- catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)

- human leukocyte antigens A (HLA-A)

- serotonin receptor subtype 2 (HTR2)

- serotonin receptor subtype 2C (HTR2C)

- opioid receptor mu 1 (OPRM1)

- solute carrier family 6 member 4 (SLC6A4).

In articles previously published in

Currently, there is no standardization among commercial pharmacogenetic tests on:

- which genes to test

- which variants specific to a gene need to be included

- how the genetic data is translated to phenotype

- how the phenotype is translated to a treatment recommendation.

Continue to: Due to these factors...

Due to these factors, the FDA has advised clinicians to consult the dosing recommendations provided in a medication’s package insert for information regarding how genetic information should be used in making treatment decisions.2

The value of decision support tools

Researchers have assessed how various manufacturers’ decision support tools (DSTs) (ie, the reports the commercial testing companies send to the clinician who orders the test) agree on genotypes, predicted phenotypes, and medication recommendations.4 Overall, this research found varying levels of disagreement in the medication recommendations of the testing panels they studied, which indicates that not all tests are equivalent or interchangeable.4 Of the actionable recommendations for antidepressants, 16% were conflicting; the recommendations for fluoxetine and imipramine were most frequently in disagreement.4 Similarly, 20% of the actionable antipsychotic advice was conflicting, with the recommendations for aripiprazole and clozapine most frequently in disagreement.4 Researchers also reported a situation in which 4 testing panels agreed on the patient’s phenotyping status for CYP2C19, but the dosing recommendations provided for the CYP2C19 substrate, amitriptyline, differed.4 Thus, it is understandable why DSTs can result in confusion, and why clinicians should use testing panels with recommendations that best align with their individual practices, their patient’s needs, and FDA information.

Additionally, while the genes included on these panels vary, these testing panels also may not evaluate the same variants within a specific gene. These differences may impact the patient’s reported phenotypes and medication recommendations across DSTs. For example, the FDA has recommended HLA gene testing prior to prescribing carbamazepine. However, few of the available tests may include the HLA-B*15:02 variant, which has been associated with carbamazepine-induced severe cutaneous reactions in patients of Asian descent, and fewer may include the HLA-A*31:01 variant, for which testing is recommended prior to prescribing carbamazepine in patients of Caucasian descent.4 Additionally, some of the CYP enzymes—such as CYP2D6*17 and CYP2C19*3 variants, which may be more common in certain populations of patients who are members of ethnic or racial minority groups—may not be consistently included in the various panels. Thus, before deciding on a specific test, clinicians should understand which gene variants are relevant to their patients with regard to race and ethnicity, and key variants for specific medications. Clinicians should refer to FDA guidance and the Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines to determine the appropriate interpretations of genetic test results.1,2

Despite the disagreement in recommendations from the various testing companies, DSTs are useful and have been shown to facilitate implementation of relevant psychopharmacology dosing guidelines, assist in identifying optimal medication therapy, and improve patient outcomes. A recently published meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacogenetic testing found that DSTs improved symptom remission among individuals with MDD by 70%.5 This suggests that pharmacogenetic-guided DSTs may provide superior treatment compared with treatment for DSTs were not used. However, the RCTs in this meta-analysis only included patients who had previously failed an antidepressant trial.5 Therefore, it is currently unknown at what point in care DSTs should be used, and whether they would be more beneficial if they are used when starting a new therapy, or after several trials have failed.

Consider the cost

The cost and availability of pharmacogenetic testing can be an issue when making treatment decisions, and such testing may not be covered by a patient’s insurance plan. Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that Medicare would cover FDA-approved genomic tests that encompass broad gene panels if the evidence supports their use. Similarly, commercial insurers such as UnitedHealthcare have begun to cover some pharmacogenetic tests.6 Medicare or Medicaid plans cover some testing panels’ costs and patients do not incur any out-of-pocket costs; however, some private insurance companies require patients to pay at least a portion of the cost, and many companies offer financial assistance for patients based on income and other factors. Although financial coverage for testing has improved, patients may still face out-of-pocket costs; therefore, clinicians may need to weigh the benefits of pharmacogenetic testing vs its cost.7 Clinicians should also determine what timeline best suits their patient’s financial and clinical needs, and test accordingly.

Continue to: Patient education is critical

Patient education is critical

Although the benefits of using pharmacogenetic testing information when making certain treatment decisions is promising, it is important for both patients and clinicians to understand that test results do not always change therapy. A study on the impact of pharmacogenetic testing on clinical outcomes of patients with MDD found that 79% of patients were already prescribed medications that aligned with recommendations.8 Therefore, switching medications based on the test results of a patient who is doing well clinically is not recommended. However, DSTs may help with clinical decisions for ambiguous cases. For example, if a patient has a genotype and/or phenotype that aligns with medication recommendations, the DST might not be able to identify a better medication to use, but may be able to recommend dosing guidance to improve the tolerability of the patient’s current therapy.6 It is also important to understand that the results of such testing may have a broader use beyond the initial reason for obtaining testing, such as when prescribing a common blood thinner such as warfarin or clopidogrel. However, for many of the pharmacodynamic genes that are included in these panels, their use beyond the treatment of depression may be limited because outcome studies for pharmacodynamic pharmacogenes may vary based on psychiatric diagnosis. Regardless, it may be beneficial to securely save and store patient test results in a standardized place within the medical record for future use.

CASE CONTINUED

You work with Mr. J to help him understand the benefits and limitations associated with pharmacogenetic testing. Assuming Mr. J is comfortable with the costs of obtaining testing, you contact the testing companies you identified to determine the specific pharmacogene variants included on each of these panels, and which would be the most appropriate given his race. If the decision is made to order the testing, provide Mr. J with a copy of his testing report so that he can use this information should he need any additional pharmacotherapy in the future, and also maintain a copy in his patient records using a standardized location for easy future access. If Mr. J is not comfortable with the costs associated with the testing, find out which medication his brother is currently receiving for treatment; this information may help identify a treatment plan for Mr. J.

Impact on practice

As psychiatry continues to gain experience in using pharmacogenetic testing and DSTs to help guide treatments for depression and other disorders, clinicians need to learn about these tools and how to use an evidence-based approach to best implement them in their practice. Many academic medical centers have developed continuing education programs or consult services to help with this.9,10 Just as the choice of which medication to use may be based partly on clinician experience, so too may be which pharmacogenetic test to use.

Bottom Line

Pharmacogenetic tests have not been examined in head-to-head clinical trials, which makes it nearly impossible to identify which test is best to use. Although the testing companies’ decision support tools (DSTs) often disagree in their recommendations, research has shown that using DSTs can facilitate implementation of relevant psychopharmacology dosing guidelines, assist in identifying optimal medication therapy, and improve patient outcomes. Clinicians should use testing panels with recommendations that best align with their individual practices, their patient’s needs, and FDA information.

Related Resources

- PGx Gene-specific information tables. www.pharmgkb.org/page/pgxGeneRef

- Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Imipramine • Tofranil

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Warfarin • Coumadin, Jantoven

Mr. J, age 30, a Black man with major depressive disorder (MDD), has been your patient for the past year. At the time of his diagnosis, Mr. J received sertraline, 100 mg/d, but had little to no improvement. During the past year, he received trials of citalopram and paroxetine, but they were not effective for his recurrent depressive symptoms and/or resulted in significant adverse effects.

During a recent visit, Mr. J asks you about “the genetic tests that help determine which medications will work.” He mentions that his brother had this testing done and that it had “worked for him,” but offers no other details. You research the different testing panels to see which test you might use. After a brief online review, you identify at least 4 different products, and are not sure which test—if any—you should consider.

During the last few years, there has been a rise in commercial pharmacogenetic testing options, including tests available to clinicians at academic medical centers as well as direct-to-consumer testing (Table). Clinician and patient interest regarding pharmacogenetic testing in practice is often followed by the question, “Which test is best?” Although this is a logical question, providing an answer is multifactorial.1-3 Because none of the currently available tests have been compared in head-to-head clinical trials, it is nearly impossible to identify the “best” test.

In this article, we focus on the evidence-based principles that clinicians should consider when adopting pharmacogenetic testing in their practice. We discuss which genes are of most interest when prescribing psychotropic medications, the value of decision support tools, cost considerations, and patient education regarding this type of testing.

Which genes and variants should be tested?

The genes relevant to medication treatment outcomes can be broadly classified into those with pharmacokinetic vs pharmacodynamic effects. Pharmacogenes, such as those coding for the drug-metabolizing enzymes cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)2B1, may alter the rate at which medications are metabolized, thus varying the serum drug concentration across patients. Variants that impact the function of these enzymes are considered pharmacokinetic. Up to 40% of the variance in patients’ response to antidepressants may be due to variations in the pharmacokinetic genes.4 Alternatively, pharmacodynamic pharmacogenes impact drug action and therefore may affect the degree of receptor activation at a given drug concentration, overall drug efficacy, and/or the occurrence of medication sensitivity. These pharmacogenes may include:

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

- catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)

- human leukocyte antigens A (HLA-A)

- serotonin receptor subtype 2 (HTR2)

- serotonin receptor subtype 2C (HTR2C)

- opioid receptor mu 1 (OPRM1)

- solute carrier family 6 member 4 (SLC6A4).

In articles previously published in

Currently, there is no standardization among commercial pharmacogenetic tests on:

- which genes to test

- which variants specific to a gene need to be included

- how the genetic data is translated to phenotype

- how the phenotype is translated to a treatment recommendation.

Continue to: Due to these factors...

Due to these factors, the FDA has advised clinicians to consult the dosing recommendations provided in a medication’s package insert for information regarding how genetic information should be used in making treatment decisions.2

The value of decision support tools

Researchers have assessed how various manufacturers’ decision support tools (DSTs) (ie, the reports the commercial testing companies send to the clinician who orders the test) agree on genotypes, predicted phenotypes, and medication recommendations.4 Overall, this research found varying levels of disagreement in the medication recommendations of the testing panels they studied, which indicates that not all tests are equivalent or interchangeable.4 Of the actionable recommendations for antidepressants, 16% were conflicting; the recommendations for fluoxetine and imipramine were most frequently in disagreement.4 Similarly, 20% of the actionable antipsychotic advice was conflicting, with the recommendations for aripiprazole and clozapine most frequently in disagreement.4 Researchers also reported a situation in which 4 testing panels agreed on the patient’s phenotyping status for CYP2C19, but the dosing recommendations provided for the CYP2C19 substrate, amitriptyline, differed.4 Thus, it is understandable why DSTs can result in confusion, and why clinicians should use testing panels with recommendations that best align with their individual practices, their patient’s needs, and FDA information.

Additionally, while the genes included on these panels vary, these testing panels also may not evaluate the same variants within a specific gene. These differences may impact the patient’s reported phenotypes and medication recommendations across DSTs. For example, the FDA has recommended HLA gene testing prior to prescribing carbamazepine. However, few of the available tests may include the HLA-B*15:02 variant, which has been associated with carbamazepine-induced severe cutaneous reactions in patients of Asian descent, and fewer may include the HLA-A*31:01 variant, for which testing is recommended prior to prescribing carbamazepine in patients of Caucasian descent.4 Additionally, some of the CYP enzymes—such as CYP2D6*17 and CYP2C19*3 variants, which may be more common in certain populations of patients who are members of ethnic or racial minority groups—may not be consistently included in the various panels. Thus, before deciding on a specific test, clinicians should understand which gene variants are relevant to their patients with regard to race and ethnicity, and key variants for specific medications. Clinicians should refer to FDA guidance and the Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines to determine the appropriate interpretations of genetic test results.1,2

Despite the disagreement in recommendations from the various testing companies, DSTs are useful and have been shown to facilitate implementation of relevant psychopharmacology dosing guidelines, assist in identifying optimal medication therapy, and improve patient outcomes. A recently published meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacogenetic testing found that DSTs improved symptom remission among individuals with MDD by 70%.5 This suggests that pharmacogenetic-guided DSTs may provide superior treatment compared with treatment for DSTs were not used. However, the RCTs in this meta-analysis only included patients who had previously failed an antidepressant trial.5 Therefore, it is currently unknown at what point in care DSTs should be used, and whether they would be more beneficial if they are used when starting a new therapy, or after several trials have failed.

Consider the cost

The cost and availability of pharmacogenetic testing can be an issue when making treatment decisions, and such testing may not be covered by a patient’s insurance plan. Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that Medicare would cover FDA-approved genomic tests that encompass broad gene panels if the evidence supports their use. Similarly, commercial insurers such as UnitedHealthcare have begun to cover some pharmacogenetic tests.6 Medicare or Medicaid plans cover some testing panels’ costs and patients do not incur any out-of-pocket costs; however, some private insurance companies require patients to pay at least a portion of the cost, and many companies offer financial assistance for patients based on income and other factors. Although financial coverage for testing has improved, patients may still face out-of-pocket costs; therefore, clinicians may need to weigh the benefits of pharmacogenetic testing vs its cost.7 Clinicians should also determine what timeline best suits their patient’s financial and clinical needs, and test accordingly.

Continue to: Patient education is critical

Patient education is critical

Although the benefits of using pharmacogenetic testing information when making certain treatment decisions is promising, it is important for both patients and clinicians to understand that test results do not always change therapy. A study on the impact of pharmacogenetic testing on clinical outcomes of patients with MDD found that 79% of patients were already prescribed medications that aligned with recommendations.8 Therefore, switching medications based on the test results of a patient who is doing well clinically is not recommended. However, DSTs may help with clinical decisions for ambiguous cases. For example, if a patient has a genotype and/or phenotype that aligns with medication recommendations, the DST might not be able to identify a better medication to use, but may be able to recommend dosing guidance to improve the tolerability of the patient’s current therapy.6 It is also important to understand that the results of such testing may have a broader use beyond the initial reason for obtaining testing, such as when prescribing a common blood thinner such as warfarin or clopidogrel. However, for many of the pharmacodynamic genes that are included in these panels, their use beyond the treatment of depression may be limited because outcome studies for pharmacodynamic pharmacogenes may vary based on psychiatric diagnosis. Regardless, it may be beneficial to securely save and store patient test results in a standardized place within the medical record for future use.

CASE CONTINUED

You work with Mr. J to help him understand the benefits and limitations associated with pharmacogenetic testing. Assuming Mr. J is comfortable with the costs of obtaining testing, you contact the testing companies you identified to determine the specific pharmacogene variants included on each of these panels, and which would be the most appropriate given his race. If the decision is made to order the testing, provide Mr. J with a copy of his testing report so that he can use this information should he need any additional pharmacotherapy in the future, and also maintain a copy in his patient records using a standardized location for easy future access. If Mr. J is not comfortable with the costs associated with the testing, find out which medication his brother is currently receiving for treatment; this information may help identify a treatment plan for Mr. J.

Impact on practice

As psychiatry continues to gain experience in using pharmacogenetic testing and DSTs to help guide treatments for depression and other disorders, clinicians need to learn about these tools and how to use an evidence-based approach to best implement them in their practice. Many academic medical centers have developed continuing education programs or consult services to help with this.9,10 Just as the choice of which medication to use may be based partly on clinician experience, so too may be which pharmacogenetic test to use.

Bottom Line

Pharmacogenetic tests have not been examined in head-to-head clinical trials, which makes it nearly impossible to identify which test is best to use. Although the testing companies’ decision support tools (DSTs) often disagree in their recommendations, research has shown that using DSTs can facilitate implementation of relevant psychopharmacology dosing guidelines, assist in identifying optimal medication therapy, and improve patient outcomes. Clinicians should use testing panels with recommendations that best align with their individual practices, their patient’s needs, and FDA information.

Related Resources

- PGx Gene-specific information tables. www.pharmgkb.org/page/pgxGeneRef

- Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Imipramine • Tofranil

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Warfarin • Coumadin, Jantoven

1. Ellingrod, VL. Using pharmacogenetics guidelines when prescribing: what’s available. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):43-46.

2. Ellingrod VL. Pharmacogenomics testing: what the FDA says. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):29-33.

3. Ramsey LB. Pharmacogenetic testing in children: what to test and how to use it. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):30-36.

4. Bousman CA, Dunlop BW. Genotype, phenotype, and medication recommendation agreement among commercial pharmacogenetic-based decision support tools. The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 2018;18(5):613-622. doi:10.1038/s41397-018-0027-3

5. Bousman CA, Arandjelovic K, Mancuso SG, et al. Pharmacogenetic tests and depressive symptom remission: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20(1). doi:10.2217/pgs-2018-0142

6. Nicholson WT, Formea CM, Matey ET, et al. Considerations when applying pharmacogenomics to your practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(1);218-230. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.011

7. Krebs K, Milani L. Translating pharmacogenomics into clinical decisions: do not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Human Genomics. 2019;13(1). doi:10.1186/s40246-019-0229-z

8. Greden JF, Parikh S, Rothschild AJ, et al. Impact of pharmacogenomics on clinical outcomes in major depressive disorder in the GUIDED trial: a large, patient- and rater-blinded, randomized, controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;111;59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.01.003

9. Haga SB. Integrating pharmacogenetic testing into primary care. Expert Review of Precision Medicine and Drug Development. 2017;2(6):327-336. doi:10.1080/23808993.2017.1398046

10. Ward KM, Taubman DS, Pasternak AL, et al. Teaching psychiatric pharmacogenomics effectively: evaluation of a novel interprofessional online course. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2021; 4:176-183.

1. Ellingrod, VL. Using pharmacogenetics guidelines when prescribing: what’s available. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):43-46.

2. Ellingrod VL. Pharmacogenomics testing: what the FDA says. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):29-33.

3. Ramsey LB. Pharmacogenetic testing in children: what to test and how to use it. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(9):30-36.

4. Bousman CA, Dunlop BW. Genotype, phenotype, and medication recommendation agreement among commercial pharmacogenetic-based decision support tools. The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 2018;18(5):613-622. doi:10.1038/s41397-018-0027-3

5. Bousman CA, Arandjelovic K, Mancuso SG, et al. Pharmacogenetic tests and depressive symptom remission: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20(1). doi:10.2217/pgs-2018-0142

6. Nicholson WT, Formea CM, Matey ET, et al. Considerations when applying pharmacogenomics to your practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(1);218-230. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.011

7. Krebs K, Milani L. Translating pharmacogenomics into clinical decisions: do not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Human Genomics. 2019;13(1). doi:10.1186/s40246-019-0229-z

8. Greden JF, Parikh S, Rothschild AJ, et al. Impact of pharmacogenomics on clinical outcomes in major depressive disorder in the GUIDED trial: a large, patient- and rater-blinded, randomized, controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;111;59-67. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.01.003

9. Haga SB. Integrating pharmacogenetic testing into primary care. Expert Review of Precision Medicine and Drug Development. 2017;2(6):327-336. doi:10.1080/23808993.2017.1398046

10. Ward KM, Taubman DS, Pasternak AL, et al. Teaching psychiatric pharmacogenomics effectively: evaluation of a novel interprofessional online course. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2021; 4:176-183.

How COVID-19 affects peripartum women’s mental health

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on the mental health of people worldwide, and a disproportionate effect on peripartum women. In this article, we discuss the reasons for this disparity, review the limited literature on this topic, and suggest strategies to safeguard the mental health of peripartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Catastrophic events and women’s mental health

During the peripartum period, women have increased psychosocial and physical health needs.1 In addition, women are disproportionately affected by natural disasters and catastrophic events,2 which are predictors of psychiatric symptoms during the peripartum period.3 Mass tragedies previously associated with maternal stress include wildfires, hurricanes, migrations, earthquakes, and tsunamis.4,5 For example, pregnant women who survived severe exposure during Hurricane Katrina (ie, feeling that one’s life was in danger, experiencing illness or injury to self or a family member, walking through floodwaters) in 2005 had a significantly increased risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression compared with pregnant women who did not have such exposure.6 After the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan, the prevalence of psychological distress in pregnant women increased, especially among those living in the area directly affected by the tsunami.5

Epidemics and pandemics also can adversely affect peripartum women’s mental health. Studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic found that previous infectious disease outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, and Zika had negative emotional impacts on pregnant women.7 Our review of the limited literature published to date suggests that COVID-19 is having similar adverse effects.

COVID-19 poses both medical and psychiatric threats

COVID-19 infection is a physical threat to pregnant women who are already vulnerable due to the hormonal and immunological changes inherent to pregnancy. A meta-analysis of 39 studies with a total of 1,316 pregnant women indicated that the most frequently reported symptoms of COVID-19 infection were cough, fever, and myalgias.8 However, COVID-19 infection during pregnancy is also associated with an increase in pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes.9 According to the CDC, compared with their nonpregnant counterparts, pregnant women are at greater risk for severe COVID-19 infection and adverse birth outcomes such as preterm birth.10 Pregnant women who are infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; the virus responsible for COVID-19) risk ICU admission, caesarean section, and perinatal death.8 A Swedish study of 2,682 pregnant women found an increase in preeclampsia among women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, a finding attributed to COVID-19’s pattern of systemic effects.11 Vertical transmission of the novel coronavirus from mother to fetus appears to be rare but possible.12

In addition to the physical dangers of becoming infected with COVID-19, the perceived threat of infection is an added source of anxiety for some peripartum women. In addition to the concerns involved in any pregnancy, COVID-19–related sources of distress for pregnant women include worrying about harm to the fetus during pregnancy, the possibility of vertical transmission, and exposures during antenatal appointments, during employment, or from a partner.8,13

The death toll from factors associated with COVID-19 adds to the mental health burden. For every person who dies of COVID-19, an estimated 9 others may develop prolonged grief or PTSD due to the loss of someone they loved.14,15 A systematic review found that PTSD in the perinatal period is associated with negative birth and child outcomes, including low birth weight and decreased rates of breastfeeding.16 The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted human interactions, from social distancing rules and lockdowns of businesses and social activities to panic buying of grocery staples and increased economic insecurity.1 These changes have been accompanied by a rise in mental health challenges. For example, according to an August 2020 CDC survey, 40.9% of US adults reported at least 1 adverse mental or behavioral health condition, including symptoms of anxiety or depression (30.9%), symptoms of a trauma- and stressor-related disorder related to the pandemic (26.3%), and having started or increased substance use to cope with stress or emotions related to COVID-19 (13.3%).17

COVID-19–related traumas and stressors appear to affect women more than men. A study from China found that compared with men, women had significantly higher levels of self-reported pandemic-related anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS).18 This trend has been observed in other parts of the world. A study conducted by the UK Office of National Statistics reported anxiety levels were 24% higher in women vs men as reflected by scores on a self-rated anxiety scale.19

Continue to: Many factors influence...

Many factors influence the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on women in general, and peripartum women in particular (Box20-26).

Box

Factors that predispose women to increased stress during COVID-19 include an increase in child care burdens brought about by school closures and subsequent virtual schooling.20 Intimate partner violence has spiked globally during COVID-19 restrictions.24 Women also represent the majority of the health care workforce (76%) and often take on informal caregiving roles; both of these roles have seen increased burdens during the pandemic.25 Already encumbered by prepandemic gender pay inequalities, women are filing unemployment claims at a significantly increased rate compared to men.26

For women of childbearing age, the disruption of routine clinical care during COVID-19 has decreased access to reproductive health care, resulting in increases in unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and deaths.20 Another source of stress for pregnant women during COVID-19 is feeling unprepared for birth because of the pandemic, a phenomenon described as “preparedness stress.”21 Visitor restriction policies and quarantines have also caused women in labor to experience birth without their support partners, which is associated with increased posttraumatic stress symptoms.22 These restrictions also may be associated with an increase in women choosing out-of-hospital births despite the increased risk of adverse outcomes.23

Psychiatric diagnoses in peripartum women

Multiple studies and meta-analyses have begun to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal mental health. One meta-analysis of 8 studies conducted in 5 countries determined that COVID-19 significantly increases the risk of anxiety in women during the peripartum period.27 Results of another meta-analysis of 23 studies with >24,000 participants indicated that the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and insomnia in peripartum women was significantly higher during the pandemic than in pre-pandemic times.28

In an online survey of 4,451 pregnant women in the United States, nearly one-third of respondents reported elevated levels of pandemic-related stress as measured by the newly-developed Pandemic-Related Pregnancy Stress Scale.3 The rates were even higher among women who were already at risk for elevated stress levels, such as those who had survived abuse, those giving birth for the first time, or those experiencing high-risk pregnancies.3 Living in a pandemic “hot spot” also appeared to impact peripartum stress levels.

COVID-19 has adverse effects on women’s mental health specifically during the postpartum period. One study from a center in Italy found a high prevalence of depressive symptoms and PTSS in the postpartum period, with COVID-19–related factors playing an “indirect role” compared with prenatal experiences and other individual factors.2 A British study of mothers of infants age ≤12 months found that traveling for work, the impact of lockdown on food affordability, and having an income of less than £30,000 per year (approximately $41,000) predicted poorer mental health during the pandemic.29 Results of a study from China indicated that more than one-quarter of pregnant and postpartum women experienced depression during the pandemic, and women who worried about infection risk or missing pediatric visits were at increased risk.30

How to mitigate these risks

The increase in pandemic-related mental health concerns in the general population and specifically in peripartum women is a global health care challenge. Investing in mitigation strategies is necessary not only to address the current pandemic, but also to help prepare for the possibility of future traumatic events, such as another global pandemic.

Continue to: For pregnant women...

For pregnant women, ensuring access to outdoor space, increasing participation in healthy activities, and minimizing disruptions to prenatal care can protect against pandemic-related stress.3 Physical activity is an effective treatment for mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Because of the significant decrease in exercise among pregnant women during the pandemic, encouraging safe forms of physical activity such as online fitness classes could improve mental health outcomes for these patients.27 When counseling peripartum women, psychiatrists need to be creative in recommending fitness interventions to target mood symptoms, such as by suggesting virtual or at-home programs.

In an online survey, 118 obstetricians called for increased mental health resources for peripartum women, such as easier access to a helpline, educational videos, and mental health professionals.13 Increased screening for psychiatric disorders throughout the peripartum period can help identify women at greater risk, and advancements in telepsychiatry could help meet the increased need for psychiatric care during COVID-19. Psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians should consider reaching out to their colleagues who specialize in women’s health to establish new partnerships and create teams of multidisciplinary professionals.

Similarly, psychiatrists should familiarize themselves with telehealth services available to peripartum patients who could benefit from such services. Telehealth options can increase women’s access to peripartum care for both medical and psychiatric illnesses. Online options such as women’s support groups, parenting classes, and labor coaching seminars also represent valuable virtual tools to strengthen women’s social supports.

Women who need inpatient treatment for severe peripartum depression or anxiety might be particularly reluctant to receive this care during COVID-19 due to fears of becoming infected and of being separated from their infant and family while hospitalized. Clinicians should remain vigilant in screening peripartum women for mood disorders that might represent a danger to mothers and infants, and not allow concerns about COVID-19 to interfere with recommendations for psychiatric hospitalizations, when necessary. The creation of small, women-only inpatient behavioral units can help address this situation, especially given the possibility of frequent visits with infants and other peripartum support. Investment into such units is critical for supporting peripartum mental health, even in nonpandemic times.

What about vaccination? As of mid-May 2021, no large clinical trials of any COVID-19 vaccine that included pregnant women had been completed. However, 2 small preliminary studies suggested that the mRNA vaccines are safe and effective during pregnancy.31,32 When counseling peripartum patients on the risks and benefits, clinicians need to rely on this evidence, animal trials, and limited data from inadvertent exposures during pregnancy. While every woman will weigh the risks and benefits for her own circumstances, the CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have all stated that the mRNA vaccines should be offered to pregnant and breastfeeding individuals who are eligible for vaccination.33 Rasmussen et al33 have published a useful resource for clinicians regarding COVID-19 vaccination and pregnant women.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

During the COVID-19 pandemic, peripartum women have experienced increased rates of anxiety, depression, and stress. Psychiatric clinicians can help these patients by remaining vigilant in screening for psychiatric disorders, encouraging them to engage in activities to mitigate COVID-19’s adverse psychological effects, and referring them to care via telehealth and other resources as appropriate.

Related Resources

- Hu YJ, Wake M, Saffery R. Clarifying the sweeping consequences of COVID-19 in pregnant women, newborns, and children with existing cohorts. JAMA Pediatr. 2021; 75(2):117-118. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2395

- Tomfohr-Madsen LM, Racine N, Giesbrecht GF, et al. Depression and anxiety in pregnancy during COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021; 300:113912. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113912

1. Chivers BR, Garad RM, Boyle JA, et al. Perinatal distress during COVID-19: thematic analysis of an online parenting forum. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e22002. doi: 10.2196/22002

2. Ostacoli L, Cosma S, Bevilacqua F, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with postpartum psychological distress during the Covid-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):703. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03399-5

3. Preis H, Mahaffey B, Heiselman C, etal. Vulnerability and resilience to pandemic-related stress among U.S. women pregnant at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113348. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113348

4. Olson DM, Brémault-Phillips S, King S, et al. Recent Canadian efforts to develop population-level pregnancy intervention studies to mitigate effects of natural disasters and other tragedies. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2019;10(1):108-114. doi: 10.1017/S2040174418001113

5. Watanabe Z, Iwama N, Nishigori H, et al. Japan Environment & Children’s Study Group. Psychological distress during pregnancy in Miyagi after the Great East Japan Earthquake: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:341-348. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.024

6. Xiong X, Harville EW, Mattison DR, et al. Hurricane Katrina experience and the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among pregnant women. Am J Disaster Med. 2010;5(3):181-187. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2010.0020

7. Brooks SK, Weston D, Greenberg N. Psychological impact of infectious disease outbreaks on pregnant women: rapid evidence review. Public Health. 2020;189:26-36. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.006

8. Diriba K, Awulachew E, Getu E. The effect of coronavirus infection (SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV) during pregnancy and the possibility of vertical maternal-fetal transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2020;25(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s40001-020-00439-w

9. Qi M, Li X, Liu S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on patterns of pregnant women’s perception of threat and its relationship to mental state: a latent class analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0239697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239697

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Investigating the impact of COVID-19 during pregnancy. Updated February 4, 2021. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/special-populations/pregnancy-data-on-covid-19/what-cdc-is-doing.html

11. Ahlberg M, Neovius M, Saltvedt S, et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 test status and pregnancy outcomes. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1782-1785. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19124

12. Ashraf MA, Keshavarz P, Hosseinpour P, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of pregnancy and the possibility of vertical transmission. J Reprod Infertil. 2020;21(3):157-168.

13. Nanjundaswamy MH, Shiva L, Desai G, et al. COVID-19-related anxiety and concerns expressed by pregnant and postpartum women-a survey among obstetricians. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020; 23(6):787-790. doi: 10.1007/s00737-020-01060-w

14. Verdery AM, Smith-Greenaway E, Margolis R, et al. Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(30):17695-17701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007476117

15. Simon NM, Saxe GN, Marmar CR. Mental health disorders related to COVID-19-related deaths. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1493-1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19632

16. Cook N, Ayers S, Horsch A. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder during the perinatal period and child outcomes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:18-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.045

17. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

18. Almeida M, Shrestha AD, Stojanac D, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(6):741-748. doi:10.1007/s00737-020-01092-2

19. Office for National Statistics. Personal and economic well-being in Great Britain: May 2020. Published May 4, 2020. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/personalandeconomicwellbeingintheuk/may2020

20. Kuehn BM. COVID-19 halts reproductive care for millions of women. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1489. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19025

21. Preis H, Mahaffey B, Lobel M. Psychometric properties of the Pandemic-Related Pregnancy Stress Scale (PREPS). J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;41(3):191-197. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2020.1801625

22. Hermann A, Fitelson EM, Bergink V. Meeting maternal mental health needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;78(2):123-124. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1947

23. Arora KS, Mauch JT, Gibson KS. Labor and delivery visitor policies during the COVID-19 pandemic: balancing risks and benefits. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2468-2469. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7563

24. Bradbury-Jones C, Isham L. The pandemic paradox: the consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(13-14):2047-2049. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15296

25. Connor J, Madhavan S, Mokashi M, et al. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the Covid-19 pandemic: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113364. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113364

26. Scharff X, Ryley S. Breaking: some states show alarming spike in women’s share of unemployment claims. The Fuller Project. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://fullerproject.org/story/some-states-shows-alarming-spike-in-womens-share-of-unemployment-claims/

27. Hessami K, Romanelli C, Chiurazzi M, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and maternal mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;1-8. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1843155

28. Yan H, Ding Y, Guo W. Mental health of pregnant and postpartum women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2020;11:617001. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617001

29. Dib S, Rougeaux E, Vázquez-Vázquez A, et al. Maternal mental health and coping during the COVID-19 lockdown in the UK: data from the COVID-19 New Mum Study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;151(3):407-414. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13397

30. Bo HX, Yang Y, Chen J, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese pregnant and postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychosom Med. 2020. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000904

31. Collier AY, McMahan K, Yu J, et al. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in pregnant and lactating women. JAMA. 2021. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7563

32. Shanes ED, Otero S, Mithal LB, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccination in pregnancy: measures of immunity and placental histopathology. Obstet Gynecol. 2021. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004457

33. Rasmussen SA, Kelley CF, Horton JP, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(3):408-414. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004290

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on the mental health of people worldwide, and a disproportionate effect on peripartum women. In this article, we discuss the reasons for this disparity, review the limited literature on this topic, and suggest strategies to safeguard the mental health of peripartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Catastrophic events and women’s mental health

During the peripartum period, women have increased psychosocial and physical health needs.1 In addition, women are disproportionately affected by natural disasters and catastrophic events,2 which are predictors of psychiatric symptoms during the peripartum period.3 Mass tragedies previously associated with maternal stress include wildfires, hurricanes, migrations, earthquakes, and tsunamis.4,5 For example, pregnant women who survived severe exposure during Hurricane Katrina (ie, feeling that one’s life was in danger, experiencing illness or injury to self or a family member, walking through floodwaters) in 2005 had a significantly increased risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression compared with pregnant women who did not have such exposure.6 After the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan, the prevalence of psychological distress in pregnant women increased, especially among those living in the area directly affected by the tsunami.5

Epidemics and pandemics also can adversely affect peripartum women’s mental health. Studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic found that previous infectious disease outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, and Zika had negative emotional impacts on pregnant women.7 Our review of the limited literature published to date suggests that COVID-19 is having similar adverse effects.

COVID-19 poses both medical and psychiatric threats

COVID-19 infection is a physical threat to pregnant women who are already vulnerable due to the hormonal and immunological changes inherent to pregnancy. A meta-analysis of 39 studies with a total of 1,316 pregnant women indicated that the most frequently reported symptoms of COVID-19 infection were cough, fever, and myalgias.8 However, COVID-19 infection during pregnancy is also associated with an increase in pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes.9 According to the CDC, compared with their nonpregnant counterparts, pregnant women are at greater risk for severe COVID-19 infection and adverse birth outcomes such as preterm birth.10 Pregnant women who are infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; the virus responsible for COVID-19) risk ICU admission, caesarean section, and perinatal death.8 A Swedish study of 2,682 pregnant women found an increase in preeclampsia among women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, a finding attributed to COVID-19’s pattern of systemic effects.11 Vertical transmission of the novel coronavirus from mother to fetus appears to be rare but possible.12

In addition to the physical dangers of becoming infected with COVID-19, the perceived threat of infection is an added source of anxiety for some peripartum women. In addition to the concerns involved in any pregnancy, COVID-19–related sources of distress for pregnant women include worrying about harm to the fetus during pregnancy, the possibility of vertical transmission, and exposures during antenatal appointments, during employment, or from a partner.8,13

The death toll from factors associated with COVID-19 adds to the mental health burden. For every person who dies of COVID-19, an estimated 9 others may develop prolonged grief or PTSD due to the loss of someone they loved.14,15 A systematic review found that PTSD in the perinatal period is associated with negative birth and child outcomes, including low birth weight and decreased rates of breastfeeding.16 The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted human interactions, from social distancing rules and lockdowns of businesses and social activities to panic buying of grocery staples and increased economic insecurity.1 These changes have been accompanied by a rise in mental health challenges. For example, according to an August 2020 CDC survey, 40.9% of US adults reported at least 1 adverse mental or behavioral health condition, including symptoms of anxiety or depression (30.9%), symptoms of a trauma- and stressor-related disorder related to the pandemic (26.3%), and having started or increased substance use to cope with stress or emotions related to COVID-19 (13.3%).17

COVID-19–related traumas and stressors appear to affect women more than men. A study from China found that compared with men, women had significantly higher levels of self-reported pandemic-related anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS).18 This trend has been observed in other parts of the world. A study conducted by the UK Office of National Statistics reported anxiety levels were 24% higher in women vs men as reflected by scores on a self-rated anxiety scale.19

Continue to: Many factors influence...

Many factors influence the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on women in general, and peripartum women in particular (Box20-26).

Box

Factors that predispose women to increased stress during COVID-19 include an increase in child care burdens brought about by school closures and subsequent virtual schooling.20 Intimate partner violence has spiked globally during COVID-19 restrictions.24 Women also represent the majority of the health care workforce (76%) and often take on informal caregiving roles; both of these roles have seen increased burdens during the pandemic.25 Already encumbered by prepandemic gender pay inequalities, women are filing unemployment claims at a significantly increased rate compared to men.26

For women of childbearing age, the disruption of routine clinical care during COVID-19 has decreased access to reproductive health care, resulting in increases in unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and deaths.20 Another source of stress for pregnant women during COVID-19 is feeling unprepared for birth because of the pandemic, a phenomenon described as “preparedness stress.”21 Visitor restriction policies and quarantines have also caused women in labor to experience birth without their support partners, which is associated with increased posttraumatic stress symptoms.22 These restrictions also may be associated with an increase in women choosing out-of-hospital births despite the increased risk of adverse outcomes.23

Psychiatric diagnoses in peripartum women

Multiple studies and meta-analyses have begun to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal mental health. One meta-analysis of 8 studies conducted in 5 countries determined that COVID-19 significantly increases the risk of anxiety in women during the peripartum period.27 Results of another meta-analysis of 23 studies with >24,000 participants indicated that the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and insomnia in peripartum women was significantly higher during the pandemic than in pre-pandemic times.28

In an online survey of 4,451 pregnant women in the United States, nearly one-third of respondents reported elevated levels of pandemic-related stress as measured by the newly-developed Pandemic-Related Pregnancy Stress Scale.3 The rates were even higher among women who were already at risk for elevated stress levels, such as those who had survived abuse, those giving birth for the first time, or those experiencing high-risk pregnancies.3 Living in a pandemic “hot spot” also appeared to impact peripartum stress levels.

COVID-19 has adverse effects on women’s mental health specifically during the postpartum period. One study from a center in Italy found a high prevalence of depressive symptoms and PTSS in the postpartum period, with COVID-19–related factors playing an “indirect role” compared with prenatal experiences and other individual factors.2 A British study of mothers of infants age ≤12 months found that traveling for work, the impact of lockdown on food affordability, and having an income of less than £30,000 per year (approximately $41,000) predicted poorer mental health during the pandemic.29 Results of a study from China indicated that more than one-quarter of pregnant and postpartum women experienced depression during the pandemic, and women who worried about infection risk or missing pediatric visits were at increased risk.30

How to mitigate these risks

The increase in pandemic-related mental health concerns in the general population and specifically in peripartum women is a global health care challenge. Investing in mitigation strategies is necessary not only to address the current pandemic, but also to help prepare for the possibility of future traumatic events, such as another global pandemic.

Continue to: For pregnant women...

For pregnant women, ensuring access to outdoor space, increasing participation in healthy activities, and minimizing disruptions to prenatal care can protect against pandemic-related stress.3 Physical activity is an effective treatment for mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Because of the significant decrease in exercise among pregnant women during the pandemic, encouraging safe forms of physical activity such as online fitness classes could improve mental health outcomes for these patients.27 When counseling peripartum women, psychiatrists need to be creative in recommending fitness interventions to target mood symptoms, such as by suggesting virtual or at-home programs.

In an online survey, 118 obstetricians called for increased mental health resources for peripartum women, such as easier access to a helpline, educational videos, and mental health professionals.13 Increased screening for psychiatric disorders throughout the peripartum period can help identify women at greater risk, and advancements in telepsychiatry could help meet the increased need for psychiatric care during COVID-19. Psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians should consider reaching out to their colleagues who specialize in women’s health to establish new partnerships and create teams of multidisciplinary professionals.

Similarly, psychiatrists should familiarize themselves with telehealth services available to peripartum patients who could benefit from such services. Telehealth options can increase women’s access to peripartum care for both medical and psychiatric illnesses. Online options such as women’s support groups, parenting classes, and labor coaching seminars also represent valuable virtual tools to strengthen women’s social supports.

Women who need inpatient treatment for severe peripartum depression or anxiety might be particularly reluctant to receive this care during COVID-19 due to fears of becoming infected and of being separated from their infant and family while hospitalized. Clinicians should remain vigilant in screening peripartum women for mood disorders that might represent a danger to mothers and infants, and not allow concerns about COVID-19 to interfere with recommendations for psychiatric hospitalizations, when necessary. The creation of small, women-only inpatient behavioral units can help address this situation, especially given the possibility of frequent visits with infants and other peripartum support. Investment into such units is critical for supporting peripartum mental health, even in nonpandemic times.

What about vaccination? As of mid-May 2021, no large clinical trials of any COVID-19 vaccine that included pregnant women had been completed. However, 2 small preliminary studies suggested that the mRNA vaccines are safe and effective during pregnancy.31,32 When counseling peripartum patients on the risks and benefits, clinicians need to rely on this evidence, animal trials, and limited data from inadvertent exposures during pregnancy. While every woman will weigh the risks and benefits for her own circumstances, the CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have all stated that the mRNA vaccines should be offered to pregnant and breastfeeding individuals who are eligible for vaccination.33 Rasmussen et al33 have published a useful resource for clinicians regarding COVID-19 vaccination and pregnant women.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

During the COVID-19 pandemic, peripartum women have experienced increased rates of anxiety, depression, and stress. Psychiatric clinicians can help these patients by remaining vigilant in screening for psychiatric disorders, encouraging them to engage in activities to mitigate COVID-19’s adverse psychological effects, and referring them to care via telehealth and other resources as appropriate.

Related Resources

- Hu YJ, Wake M, Saffery R. Clarifying the sweeping consequences of COVID-19 in pregnant women, newborns, and children with existing cohorts. JAMA Pediatr. 2021; 75(2):117-118. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2395

- Tomfohr-Madsen LM, Racine N, Giesbrecht GF, et al. Depression and anxiety in pregnancy during COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021; 300:113912. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113912

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on the mental health of people worldwide, and a disproportionate effect on peripartum women. In this article, we discuss the reasons for this disparity, review the limited literature on this topic, and suggest strategies to safeguard the mental health of peripartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Catastrophic events and women’s mental health

During the peripartum period, women have increased psychosocial and physical health needs.1 In addition, women are disproportionately affected by natural disasters and catastrophic events,2 which are predictors of psychiatric symptoms during the peripartum period.3 Mass tragedies previously associated with maternal stress include wildfires, hurricanes, migrations, earthquakes, and tsunamis.4,5 For example, pregnant women who survived severe exposure during Hurricane Katrina (ie, feeling that one’s life was in danger, experiencing illness or injury to self or a family member, walking through floodwaters) in 2005 had a significantly increased risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression compared with pregnant women who did not have such exposure.6 After the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan, the prevalence of psychological distress in pregnant women increased, especially among those living in the area directly affected by the tsunami.5

Epidemics and pandemics also can adversely affect peripartum women’s mental health. Studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic found that previous infectious disease outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, and Zika had negative emotional impacts on pregnant women.7 Our review of the limited literature published to date suggests that COVID-19 is having similar adverse effects.

COVID-19 poses both medical and psychiatric threats