User login

Neurodegeneration complicates psychiatric care for Parkinson’s patients

Managing depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s disease should start with a review of medications and involve multidisciplinary care, according to a recent summary of evidence.

“Depression and anxiety have a complex relationship with the disease and while the exact mechanism for this association is unknown, both disturbances occur with increased prevalence across the disease course and when present earlier in life, increase the risk of PD by about twofold,” wrote Gregory M. Pontone, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

Randomized trials to guide treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) are limited, the researchers noted. However, data from a longitudinal study showed that PD patients whose depression remitted spontaneously or responded to treatment were able to attain a level of function similar to that of never-depressed PD patients, Dr. Pontone and colleagues said.

The researchers offered a pair of treatment algorithms to help guide clinicians in managing depression and anxiety in PD. However, a caveat to keep in mind is that “the benefit of antidepressant medications, used for depression or anxiety, can be confounded when motor symptoms are not optimally treated,” the researchers emphasized.

For depression, the researchers advised starting with some lab work; “at a minimum we suggest checking a complete blood count, metabolic panel, TSH, B12, and folate,” they noted. They recommended an antidepressant, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or both, as a first-line treatment, such as monotherapy with selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. They advised titrating the chosen monotherapy to a minimum effective dose over a 2- to 3-week period to assess response.

“We recommend continuing antidepressant therapy for at least 1 year based on literature in non-PD populations and anecdotal clinical experience. At 1 year, if not in remission, consider continuing treatment or augmenting to improve response,” the researchers said.

, and they recommended using anxiety rating scales to diagnose anxiety in PD. “Given the high prevalence of atypical anxiety syndromes in PD and their potential association with both motor and nonmotor symptoms of the disease, working with the neurologist to achieve optimal control of PD is an essential first step to alleviating anxiety,” they emphasized.

The researchers also advised addressing comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, diabetes, gastrointestinal issues, hyperthyroidism, and lung disease, all of which can be associated with anxiety. Once comorbidities are addressed, they advised caution given the lack of evidence for efficacy of both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic anxiety treatments for PD patients. However, first-tier treatment for anxiety could include monotherapy with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, they said.

PD patients with depression and anxiety also may benefit from nonpharmacologic interventions, including exercise, mindfulness, relaxation therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy the researchers said.

Although the algorithm may not differ significantly from current treatment protocols, it highlights aspects unique to PD patients, the researchers said. In particular, the algorithm shows “that interventions used for motor symptoms, for example, dopamine agonists, may be especially potent for mood in the PD population and that augmentation strategies, such as antipsychotics and lithium, may not be well tolerated given their outsized risk of adverse events in PD,” they said.

“While an article of this kind cannot hope to address the gap in knowledge on comparative efficacy between interventions, it can guide readers on the best strategies for implementation and risk mitigation in PD – essentially focusing more on effectiveness,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Pontone disclosed serving as a consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Concert Pharmaceuticals.

Managing depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s disease should start with a review of medications and involve multidisciplinary care, according to a recent summary of evidence.

“Depression and anxiety have a complex relationship with the disease and while the exact mechanism for this association is unknown, both disturbances occur with increased prevalence across the disease course and when present earlier in life, increase the risk of PD by about twofold,” wrote Gregory M. Pontone, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

Randomized trials to guide treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) are limited, the researchers noted. However, data from a longitudinal study showed that PD patients whose depression remitted spontaneously or responded to treatment were able to attain a level of function similar to that of never-depressed PD patients, Dr. Pontone and colleagues said.

The researchers offered a pair of treatment algorithms to help guide clinicians in managing depression and anxiety in PD. However, a caveat to keep in mind is that “the benefit of antidepressant medications, used for depression or anxiety, can be confounded when motor symptoms are not optimally treated,” the researchers emphasized.

For depression, the researchers advised starting with some lab work; “at a minimum we suggest checking a complete blood count, metabolic panel, TSH, B12, and folate,” they noted. They recommended an antidepressant, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or both, as a first-line treatment, such as monotherapy with selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. They advised titrating the chosen monotherapy to a minimum effective dose over a 2- to 3-week period to assess response.

“We recommend continuing antidepressant therapy for at least 1 year based on literature in non-PD populations and anecdotal clinical experience. At 1 year, if not in remission, consider continuing treatment or augmenting to improve response,” the researchers said.

, and they recommended using anxiety rating scales to diagnose anxiety in PD. “Given the high prevalence of atypical anxiety syndromes in PD and their potential association with both motor and nonmotor symptoms of the disease, working with the neurologist to achieve optimal control of PD is an essential first step to alleviating anxiety,” they emphasized.

The researchers also advised addressing comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, diabetes, gastrointestinal issues, hyperthyroidism, and lung disease, all of which can be associated with anxiety. Once comorbidities are addressed, they advised caution given the lack of evidence for efficacy of both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic anxiety treatments for PD patients. However, first-tier treatment for anxiety could include monotherapy with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, they said.

PD patients with depression and anxiety also may benefit from nonpharmacologic interventions, including exercise, mindfulness, relaxation therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy the researchers said.

Although the algorithm may not differ significantly from current treatment protocols, it highlights aspects unique to PD patients, the researchers said. In particular, the algorithm shows “that interventions used for motor symptoms, for example, dopamine agonists, may be especially potent for mood in the PD population and that augmentation strategies, such as antipsychotics and lithium, may not be well tolerated given their outsized risk of adverse events in PD,” they said.

“While an article of this kind cannot hope to address the gap in knowledge on comparative efficacy between interventions, it can guide readers on the best strategies for implementation and risk mitigation in PD – essentially focusing more on effectiveness,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Pontone disclosed serving as a consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Concert Pharmaceuticals.

Managing depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s disease should start with a review of medications and involve multidisciplinary care, according to a recent summary of evidence.

“Depression and anxiety have a complex relationship with the disease and while the exact mechanism for this association is unknown, both disturbances occur with increased prevalence across the disease course and when present earlier in life, increase the risk of PD by about twofold,” wrote Gregory M. Pontone, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

Randomized trials to guide treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) are limited, the researchers noted. However, data from a longitudinal study showed that PD patients whose depression remitted spontaneously or responded to treatment were able to attain a level of function similar to that of never-depressed PD patients, Dr. Pontone and colleagues said.

The researchers offered a pair of treatment algorithms to help guide clinicians in managing depression and anxiety in PD. However, a caveat to keep in mind is that “the benefit of antidepressant medications, used for depression or anxiety, can be confounded when motor symptoms are not optimally treated,” the researchers emphasized.

For depression, the researchers advised starting with some lab work; “at a minimum we suggest checking a complete blood count, metabolic panel, TSH, B12, and folate,” they noted. They recommended an antidepressant, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or both, as a first-line treatment, such as monotherapy with selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. They advised titrating the chosen monotherapy to a minimum effective dose over a 2- to 3-week period to assess response.

“We recommend continuing antidepressant therapy for at least 1 year based on literature in non-PD populations and anecdotal clinical experience. At 1 year, if not in remission, consider continuing treatment or augmenting to improve response,” the researchers said.

, and they recommended using anxiety rating scales to diagnose anxiety in PD. “Given the high prevalence of atypical anxiety syndromes in PD and their potential association with both motor and nonmotor symptoms of the disease, working with the neurologist to achieve optimal control of PD is an essential first step to alleviating anxiety,” they emphasized.

The researchers also advised addressing comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, diabetes, gastrointestinal issues, hyperthyroidism, and lung disease, all of which can be associated with anxiety. Once comorbidities are addressed, they advised caution given the lack of evidence for efficacy of both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic anxiety treatments for PD patients. However, first-tier treatment for anxiety could include monotherapy with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, they said.

PD patients with depression and anxiety also may benefit from nonpharmacologic interventions, including exercise, mindfulness, relaxation therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy the researchers said.

Although the algorithm may not differ significantly from current treatment protocols, it highlights aspects unique to PD patients, the researchers said. In particular, the algorithm shows “that interventions used for motor symptoms, for example, dopamine agonists, may be especially potent for mood in the PD population and that augmentation strategies, such as antipsychotics and lithium, may not be well tolerated given their outsized risk of adverse events in PD,” they said.

“While an article of this kind cannot hope to address the gap in knowledge on comparative efficacy between interventions, it can guide readers on the best strategies for implementation and risk mitigation in PD – essentially focusing more on effectiveness,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Pontone disclosed serving as a consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Concert Pharmaceuticals.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GERIATRIC PSYCHIATRY

Low-dose nitrous oxide shows benefit for resistant depression

A 1-hour treatment with a low concentration of nitrous oxide, commonly known as “laughing gas,” appears to relieve symptoms of treatment-resistant major depression (TRMD), with effects lasting as long as several weeks, new research suggests.

In a trial with a crossover design, investigators randomly assigned 28 patients with severe TRMD to receive a single 1-hour inhalation of placebo or nitrous oxide once a month over a 3-month period. Participants received an inhalation of placebo; a 25% concentration of nitrous oxide; and a 50% concentration of nitrous oxide. Sessions were conducted 4 weeks apart.

Both doses of nitrous oxide were associated with substantial improvement in depressive symptoms for roughly 85% of participants. However, the 25% concentration had a lower risk for adverse effects, which included sedation, nausea, and mild dissociation, compared to the 50% concentration.

“Twenty-five percent nitrous oxide has similar efficacy, compared to 50% nitrous oxide, and reduced side effects fourfold,” lead author Peter Nagele, MD, MSc, chair and professor of anesthesia and critical care, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“We also observed that many patients had a 2-week improvement of depressive symptoms after a nitrous oxide treatment,” said Dr. Nagele, who also is professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience.

The study was published online June 9 in Science Translational Medicine.

Further refinement

A previous proof-of-principle study conducted by the same researchers demonstrated that a 1-hour inhalation of 50% nitrous oxide had rapid antidepressant effects for patients with TRMD.

The current phase 2 trial “is a follow-up study to our earlier 2015 pilot trial and was designed to further refine the dose of nitrous oxide needed for antidepressant efficacy,” Dr. Nagele said.

“An important secondary aim [of the current study] was to determine whether a lower dose – 25% – would reduce side effects, and a third aim was to determine how long the antidepressants effects last,” he explained.

To investigate, the researchers enrolled 28 patients (median [interquartile range (IQR)] age 39 years [26-68 years]; 71% women; 96% White) to have three inhalation sessions (placebo, 25%, and 50% nitrous oxide) at 4-week intervals. Twenty patients completed all three inhalation sessions, and four completed ≥1 treatment.

Participants had “sustained and refractory depressive illness,” with a mean illness lifetime duration of 17.5 years and an extensive history of antidepressant drug failure (median, 4.5 [2-10] adequate-dose/duration antidepressants).

Some patients had undergone vagus nerve stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or had received ketamine (4%, 8%, 13%, and 8%, respectively).

The primary outcome was improvement on the 21-item Hamilton Depression rating Scale (HDRS-21) score over a 2-week observation period.

‘Stronger evidence’

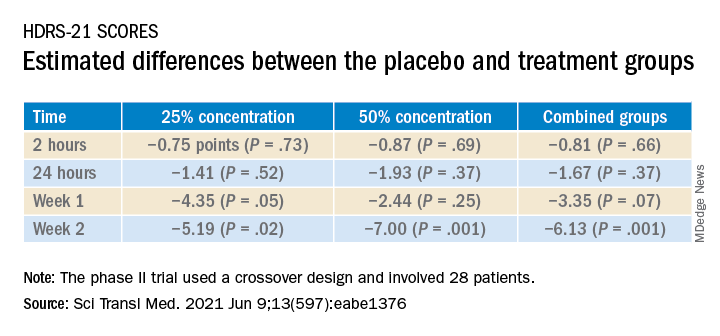

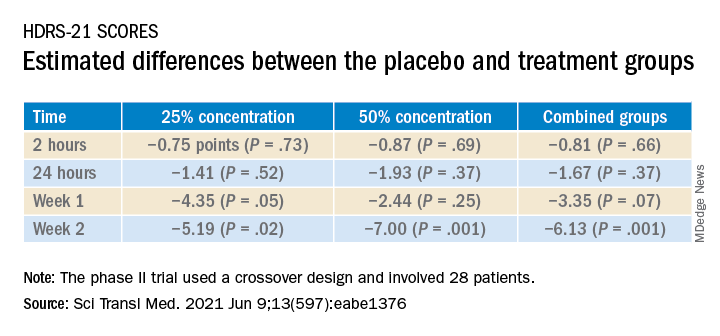

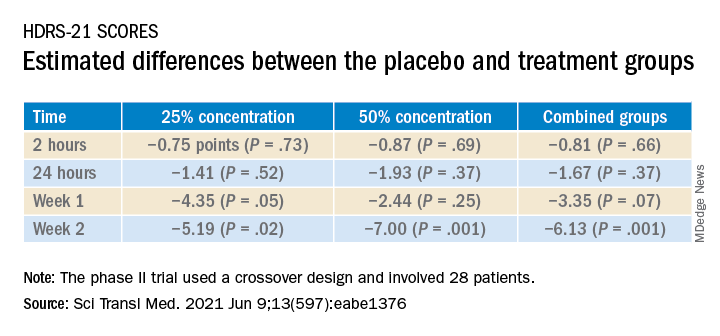

Compared to placebo, nitrous oxide significantly improved depressive symptoms (P = .01). There was no significant difference between the 25% and the 50% concentrations (P = .58).

The estimated difference in HDRS-21 scores between the placebo and various treatment groups are shown in the following table.

To ensure there where were carryover effects between the two doses, the researchers performed an analysis to ascertain whether order of receipt of the higher dose was related to the 2-week HDRS-21 score; they found no significant effect of trial order (P = .22).

The 20 patients who completed the entire course of treatment “experienced a clinically significant improvement in depressive symptoms from a median baseline HDRS-21 score of 20.5 (IQR, 19.0 to 25.5) to 8.5 (IQR, 2.0 to 16.0) at study completion, corresponding to a median change of −11.0 points (IQR, −3.3 to −14.0 points; P < .0001) after the 3-month study period,” the investigators noted.

The types of treatment response and improvement in depressive symptoms from baseline to study completion are listed in the table below.

There were statistically significant differences in adverse events between the two treatment doses; 47 events occurred following inhalation of the 50% concentration, compared to 11 after inhalation of the 25% concentration. There were six adverse events after inhalation of placebo (P < .0001).

“None of the adverse events were serious, and nearly all occurred either during or immediately after the treatment session and resolved within several hours,” the authors reported.

“We need to be remindful that – despite the exciting results of the study – the study was small and cannot be considered definitive evidence; as such, it is too early to advocate for the use of nitrous oxide in everyday clinical practice,” Dr. Nagele said.

Nevertheless, on the basis of the current findings, he stated.

Rapid-acting antidepressants

Commenting on the study in an interview, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at Toronto Western Hospital, noted that the research into nitrous oxide is “part of an interest in rapid-acting antidepressants.”

Dr. McIntyre, also the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, found it “interesting” that “almost 20% of the sample had previously had suboptimal outcomes to ketamine and/or neurostimulation, meaning these patients had serious refractory illness, but the benefit [of nitrous oxide] was sustained at 2 weeks.”

Studies of the use of nitrous oxide for patients with bipolar depression “would be warranted, since it appears generally safe and well tolerated,” said Dr. McIntyre, director of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance.

The study was sponsored by an award to Dr. Nagele from the NARSAD Independent Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and an award to Dr. Nagele and other coauthors from the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Nagele receives funding from the National Institute of Mental Health the American Foundation for Prevention of Suicide, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; has received research funding and honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics; and has previously filed for intellectual property protection related to the use of nitrous oxide in major depression. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and Abbvie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 1-hour treatment with a low concentration of nitrous oxide, commonly known as “laughing gas,” appears to relieve symptoms of treatment-resistant major depression (TRMD), with effects lasting as long as several weeks, new research suggests.

In a trial with a crossover design, investigators randomly assigned 28 patients with severe TRMD to receive a single 1-hour inhalation of placebo or nitrous oxide once a month over a 3-month period. Participants received an inhalation of placebo; a 25% concentration of nitrous oxide; and a 50% concentration of nitrous oxide. Sessions were conducted 4 weeks apart.

Both doses of nitrous oxide were associated with substantial improvement in depressive symptoms for roughly 85% of participants. However, the 25% concentration had a lower risk for adverse effects, which included sedation, nausea, and mild dissociation, compared to the 50% concentration.

“Twenty-five percent nitrous oxide has similar efficacy, compared to 50% nitrous oxide, and reduced side effects fourfold,” lead author Peter Nagele, MD, MSc, chair and professor of anesthesia and critical care, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“We also observed that many patients had a 2-week improvement of depressive symptoms after a nitrous oxide treatment,” said Dr. Nagele, who also is professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience.

The study was published online June 9 in Science Translational Medicine.

Further refinement

A previous proof-of-principle study conducted by the same researchers demonstrated that a 1-hour inhalation of 50% nitrous oxide had rapid antidepressant effects for patients with TRMD.

The current phase 2 trial “is a follow-up study to our earlier 2015 pilot trial and was designed to further refine the dose of nitrous oxide needed for antidepressant efficacy,” Dr. Nagele said.

“An important secondary aim [of the current study] was to determine whether a lower dose – 25% – would reduce side effects, and a third aim was to determine how long the antidepressants effects last,” he explained.

To investigate, the researchers enrolled 28 patients (median [interquartile range (IQR)] age 39 years [26-68 years]; 71% women; 96% White) to have three inhalation sessions (placebo, 25%, and 50% nitrous oxide) at 4-week intervals. Twenty patients completed all three inhalation sessions, and four completed ≥1 treatment.

Participants had “sustained and refractory depressive illness,” with a mean illness lifetime duration of 17.5 years and an extensive history of antidepressant drug failure (median, 4.5 [2-10] adequate-dose/duration antidepressants).

Some patients had undergone vagus nerve stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or had received ketamine (4%, 8%, 13%, and 8%, respectively).

The primary outcome was improvement on the 21-item Hamilton Depression rating Scale (HDRS-21) score over a 2-week observation period.

‘Stronger evidence’

Compared to placebo, nitrous oxide significantly improved depressive symptoms (P = .01). There was no significant difference between the 25% and the 50% concentrations (P = .58).

The estimated difference in HDRS-21 scores between the placebo and various treatment groups are shown in the following table.

To ensure there where were carryover effects between the two doses, the researchers performed an analysis to ascertain whether order of receipt of the higher dose was related to the 2-week HDRS-21 score; they found no significant effect of trial order (P = .22).

The 20 patients who completed the entire course of treatment “experienced a clinically significant improvement in depressive symptoms from a median baseline HDRS-21 score of 20.5 (IQR, 19.0 to 25.5) to 8.5 (IQR, 2.0 to 16.0) at study completion, corresponding to a median change of −11.0 points (IQR, −3.3 to −14.0 points; P < .0001) after the 3-month study period,” the investigators noted.

The types of treatment response and improvement in depressive symptoms from baseline to study completion are listed in the table below.

There were statistically significant differences in adverse events between the two treatment doses; 47 events occurred following inhalation of the 50% concentration, compared to 11 after inhalation of the 25% concentration. There were six adverse events after inhalation of placebo (P < .0001).

“None of the adverse events were serious, and nearly all occurred either during or immediately after the treatment session and resolved within several hours,” the authors reported.

“We need to be remindful that – despite the exciting results of the study – the study was small and cannot be considered definitive evidence; as such, it is too early to advocate for the use of nitrous oxide in everyday clinical practice,” Dr. Nagele said.

Nevertheless, on the basis of the current findings, he stated.

Rapid-acting antidepressants

Commenting on the study in an interview, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at Toronto Western Hospital, noted that the research into nitrous oxide is “part of an interest in rapid-acting antidepressants.”

Dr. McIntyre, also the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, found it “interesting” that “almost 20% of the sample had previously had suboptimal outcomes to ketamine and/or neurostimulation, meaning these patients had serious refractory illness, but the benefit [of nitrous oxide] was sustained at 2 weeks.”

Studies of the use of nitrous oxide for patients with bipolar depression “would be warranted, since it appears generally safe and well tolerated,” said Dr. McIntyre, director of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance.

The study was sponsored by an award to Dr. Nagele from the NARSAD Independent Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and an award to Dr. Nagele and other coauthors from the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Nagele receives funding from the National Institute of Mental Health the American Foundation for Prevention of Suicide, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; has received research funding and honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics; and has previously filed for intellectual property protection related to the use of nitrous oxide in major depression. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and Abbvie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 1-hour treatment with a low concentration of nitrous oxide, commonly known as “laughing gas,” appears to relieve symptoms of treatment-resistant major depression (TRMD), with effects lasting as long as several weeks, new research suggests.

In a trial with a crossover design, investigators randomly assigned 28 patients with severe TRMD to receive a single 1-hour inhalation of placebo or nitrous oxide once a month over a 3-month period. Participants received an inhalation of placebo; a 25% concentration of nitrous oxide; and a 50% concentration of nitrous oxide. Sessions were conducted 4 weeks apart.

Both doses of nitrous oxide were associated with substantial improvement in depressive symptoms for roughly 85% of participants. However, the 25% concentration had a lower risk for adverse effects, which included sedation, nausea, and mild dissociation, compared to the 50% concentration.

“Twenty-five percent nitrous oxide has similar efficacy, compared to 50% nitrous oxide, and reduced side effects fourfold,” lead author Peter Nagele, MD, MSc, chair and professor of anesthesia and critical care, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“We also observed that many patients had a 2-week improvement of depressive symptoms after a nitrous oxide treatment,” said Dr. Nagele, who also is professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience.

The study was published online June 9 in Science Translational Medicine.

Further refinement

A previous proof-of-principle study conducted by the same researchers demonstrated that a 1-hour inhalation of 50% nitrous oxide had rapid antidepressant effects for patients with TRMD.

The current phase 2 trial “is a follow-up study to our earlier 2015 pilot trial and was designed to further refine the dose of nitrous oxide needed for antidepressant efficacy,” Dr. Nagele said.

“An important secondary aim [of the current study] was to determine whether a lower dose – 25% – would reduce side effects, and a third aim was to determine how long the antidepressants effects last,” he explained.

To investigate, the researchers enrolled 28 patients (median [interquartile range (IQR)] age 39 years [26-68 years]; 71% women; 96% White) to have three inhalation sessions (placebo, 25%, and 50% nitrous oxide) at 4-week intervals. Twenty patients completed all three inhalation sessions, and four completed ≥1 treatment.

Participants had “sustained and refractory depressive illness,” with a mean illness lifetime duration of 17.5 years and an extensive history of antidepressant drug failure (median, 4.5 [2-10] adequate-dose/duration antidepressants).

Some patients had undergone vagus nerve stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or had received ketamine (4%, 8%, 13%, and 8%, respectively).

The primary outcome was improvement on the 21-item Hamilton Depression rating Scale (HDRS-21) score over a 2-week observation period.

‘Stronger evidence’

Compared to placebo, nitrous oxide significantly improved depressive symptoms (P = .01). There was no significant difference between the 25% and the 50% concentrations (P = .58).

The estimated difference in HDRS-21 scores between the placebo and various treatment groups are shown in the following table.

To ensure there where were carryover effects between the two doses, the researchers performed an analysis to ascertain whether order of receipt of the higher dose was related to the 2-week HDRS-21 score; they found no significant effect of trial order (P = .22).

The 20 patients who completed the entire course of treatment “experienced a clinically significant improvement in depressive symptoms from a median baseline HDRS-21 score of 20.5 (IQR, 19.0 to 25.5) to 8.5 (IQR, 2.0 to 16.0) at study completion, corresponding to a median change of −11.0 points (IQR, −3.3 to −14.0 points; P < .0001) after the 3-month study period,” the investigators noted.

The types of treatment response and improvement in depressive symptoms from baseline to study completion are listed in the table below.

There were statistically significant differences in adverse events between the two treatment doses; 47 events occurred following inhalation of the 50% concentration, compared to 11 after inhalation of the 25% concentration. There were six adverse events after inhalation of placebo (P < .0001).

“None of the adverse events were serious, and nearly all occurred either during or immediately after the treatment session and resolved within several hours,” the authors reported.

“We need to be remindful that – despite the exciting results of the study – the study was small and cannot be considered definitive evidence; as such, it is too early to advocate for the use of nitrous oxide in everyday clinical practice,” Dr. Nagele said.

Nevertheless, on the basis of the current findings, he stated.

Rapid-acting antidepressants

Commenting on the study in an interview, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at Toronto Western Hospital, noted that the research into nitrous oxide is “part of an interest in rapid-acting antidepressants.”

Dr. McIntyre, also the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, found it “interesting” that “almost 20% of the sample had previously had suboptimal outcomes to ketamine and/or neurostimulation, meaning these patients had serious refractory illness, but the benefit [of nitrous oxide] was sustained at 2 weeks.”

Studies of the use of nitrous oxide for patients with bipolar depression “would be warranted, since it appears generally safe and well tolerated,” said Dr. McIntyre, director of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance.

The study was sponsored by an award to Dr. Nagele from the NARSAD Independent Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and an award to Dr. Nagele and other coauthors from the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Nagele receives funding from the National Institute of Mental Health the American Foundation for Prevention of Suicide, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; has received research funding and honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics; and has previously filed for intellectual property protection related to the use of nitrous oxide in major depression. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and Abbvie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How a community-based program for SMI pivoted during the pandemic

For more than 70 years, Fountain House has offered a lifeline for people living with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, and other serious mental illnesses through a community-based model of care. When he took the helm less than 2 years ago, CEO and President Ashwin Vasan, ScM, MD, PhD, wanted a greater focus on crisis-based solutions and a wider, public health approach.

That goal was put to the test in 2020, when SARS-CoV-2 shuttered all in-person activities. The nonprofit quickly rebounded, creating a digital platform, engaging with its members through online courses, face-to-face check-ins, and delivery services, and expanding partnerships to connect with individuals facing homelessness and involved in the criminal justice system. Those activities not only brought the community together – it expanded Fountain House’s footprint.

Among its membership of more than 2,000 people in New York City, about 70% connected to the digital platform. “We also enrolled more than 200 brand new members during the pandemic who had never set foot in the physical mental health “clubhouse.” They derived value as well,” Dr. Vasan said in an interview. Nationally, the program is replicated at more than 200 locations and serves about 60,000 people in almost 40 states. During the pandemic, Fountain House began formalizing affiliation opportunities with this network.

Now that the pandemic is showing signs of receding, Fountain House faces new challenges operating as a possible hybrid model. “More than three-quarters of our members say they want to continue to engage virtually as well as in person,” Dr. Vasan said. As of this writing, Fountain House is enjoying a soft reopening, slowly welcoming in-person activities. What this will look like in the coming weeks and months is a work in progress, he added. “We don’t know yet how people are going to prefer to engage.”

A role in the public policy conversation

Founded by a small group of former psychiatric patients in the late 1940s, Fountain House has since expanded from a single building in New York City to more than 300 replications in the United States and around the world. It originated the “clubhouse” model of mental health support: a community-based approach that helps members improve health, and break social and economic isolation by reclaiming social, educational, and work skills, and connecting with core services, including supportive housing and community-based primary and behavioral health care (Arts Psychother. 2012 Feb 39[1]:25-30).

Serious mental illness (SMI) is growing more pronounced as a crisis, not just in the people it affects, “but in all of the attendant and preventable social and economic crises that intersect with it, whether it’s increasing health care costs, homelessness, or criminalization,” Dr. Vasan said.

After 73 years, Fountain House is just beginning to gain relevance as a tool to help solve these intersecting public policy crises, he added.

“We’ve demonstrated through evaluation data that it reduces hospitalization rates, health care costs, reliance on emergency departments, homelessness, and recidivism to the criminal justice system,” he said. Health care costs for members are more than 20% lower than for others with mental illness, and recidivism rates among those with a criminal history are less than 5%.

Others familiar with Fountain House say the model delivers on its charge to improve quality of life for people with SMI.

It’s a great referral source for people who are under good mental health control, whether it’s therapy or a combination of therapy and medications, Robert T. London, MD, a practicing psychiatrist in New York who is not affiliated with Fountain House but has referred patients to the organization over the years, said in an interview.

“They can work with staff, learn skills regarding potential work, housekeeping, [and] social skills,” he said. One of the biggest problems facing people with SMI is they’re very isolated, Dr. London continued. “When you’re in a facility like Fountain House, you’re not isolated. You’re with fellow members, a very helpful educated staff, and you’re going to do well.” If a member is having some issues and losing touch with reality and needs to find treatment, Fountain House will provide that support.

“If you don’t have a treating person, they’re going to find you one. They’re not against traditional medical/psychiatric care,” he said.

Among those with unstable or no housing, 99% find housing within a year of joining Fountain House. While it does provide people with SMI with support to find a roof over their heads, Fountain House doesn’t necessarily fit a model of “housing first,” Stephanie Le Melle, MD, MS, director of public psychiatry education at department of psychiatry at Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute, said in an interview.

“The housing first evidence-based model, as designed and implemented by Pathways to Housing program in New York in the early 90s, accepted people who were street homeless or in shelters, not involved in mental health treatment, and actively using substances into scatter-site apartments and wrapped services around them,” she said.

Dr. Le Melle, who is not affiliated with Fountain House, views it more as a supportive employment program that uses a recovery-oriented, community-based, jointly peer-run approach to engage members in vocational/educational programming. It also happens to have some supportive housing for its members, she added.

Dr. Vasan believes Fountain House could expand beyond a community model. The organization has been moving out from its history, evolving into a model that could be integrated as standard of care and standard of practice for community health, he said. Fountain House is part of Clubhouse International, an umbrella organization that received the American Psychiatric Association’s 2021 special presidential commendation award during its virtual annual meeting for the group’s use of “the evidence-based, cost-effective clubhouse model of psychosocial rehabilitation as a leading recovery resource for people living with mental illness around the world.”

How medication issues are handled

Fountain House doesn’t directly provide medication to its members. According to Dr. Vasan, psychiatric care is just one component of recovery for serious mental illness.

“We talk about Fountain House as a main vortex in a triangle of recovery. You need health care, housing, and community. The part that’s been neglected the most is community intervention, the social infrastructure for people who are deeply isolated and marginalized,” he said. “We know that people who have that infrastructure, and are stably housed, are then more likely to engage in community-based psychiatry and primary care. And in turn, people who are in stable clinical care can more durably engage in the community programming Fountain House offers.”

Health care and clinical care are changing. It’s becoming more person-centered and community based. “We need to move with the times and we have, in the last 2 decades,” he said.

Historically, Fountain House has owned and operated its own clinic in New York City. More recently, it partnered with Sun River Health and Ryan Health, two large federally qualified health center networks in New York, so that members receive access to psychiatric and medical care. It has also expanded similar partnerships with Columbia University, New York University, and other health care systems to ensure its members have access to sustainable clinical care as a part of the community conditions and resources needed to recover and thrive.

Those familiar with the organization don’t see the absence of a medication program as a negative factor. If Fountain House doesn’t provide psychiatric medications, “that tells me the patients are under control and able to function in a community setting” that focuses on rehabilitation, Dr. London said.

It’s true that psychiatric medication treatment is an essential part of a patient’s recovery journey, Dr. Le Melle said. “Treatment with medications can be done in a recovery-oriented way. However, the Fountain House model has been designed to keep these separate, and this model works well for most” of the members.

As long as members and staff are willing to collaborate with treatment providers outside of the clubhouse, when necessary, this model of separation between work and treatment can work really well, she added.

“There are some people who need a more integrated system of care. There is no ‘one size fits all’ program that can meet everyone’s needs,” said Dr. Le Melle. The absence of onsite treatment at Fountain House, to some extent “adds to the milieu and allows people to focus on other aspects of their lives besides their illness.”

This hasn’t always been the case in traditionally funded behavioral health programs, she continued. Most mental health clinics, because of fiscal structures, reimbursement, and staffing costs, focus more on psychotherapy and medication management than on other aspects of peoples’ lives, such as their recovery goals.

The bottom line is rehabilitation in medicine works – whether it’s for a mental health disorder, broken leg, arm, or stroke, Dr. London said. “Fountain House’s focus is integrating a person into society by helping them to think differently and interact socially in groups and learn some skills.”

Through cognitive-behavioral therapies, a person with mental illness can learn how to act differently. “The brain is always in a growing process where you learn and develop new ideas, make connections,” Dr. London said. “New protein molecules get created and stored; changes occur with the neurotransmitters.”

Overall, the Fountain House model is great for supporting and engaging people with serious mental illness, Dr. Le Melle said. “It provides a literal place, a community, and a safe environment that helps people to embrace their recovery journey. It is also great at supporting people in their engagement with vocational training and employment.”

Ideally, she would like Fountain House to grow and become more inclusive by engaging people who live with both mental illness and substance use.

COVID-19 changes the rules

The most difficult challenge for health care and other institutions is to keep individuals with SMI engaged and visible so that they can find access to health care and benefits – and avoid acute hospitalization or medical care. “That’s our goal, to prevent the worst effects and respond accordingly,” Dr. Vasan said.

SARS-CoV-2 forced the program to reevaluate its daily operations so that it could maintain crucial connections with its members.

Dr. Vasan and his staff immediately closed the clubhouse when COVID-19 first hit, transitioning to direct community-based services that provided one-on-one outreach, and meal, medication, and clothing delivery. “Even if people couldn’t visit our clubhouse, we wanted them to feel that sense of community connection, even if it was to drop off meals at their doorstep,” he said.

Donning personal protective equipment, his staff and interested program participants went out into the communities to do this personal outreach. At the height of pandemic in New York City, “we weren’t sure what to do,” as far as keeping safe, he admitted. Nevertheless, he believes this outreach work was lifesaving in that it kept people connected to the clubhouse.

As Fountain House worked to maintain in-person contact, it also built a digital community to keep the live community together. This wasn’t just about posting on a Facebook page – it was interactive, Dr. Vasan noted. An online group made masks for the community and sold them for people outside of Fountain House. Capacity building courses instructed members on writing resumes, looking for jobs, or filling out applications.

There’s an assumption that people with SMI lack the skills to navigate technology. Some of the hallmarks of SMI are demotivation and lack of confidence, and logging onto platforms and email can be challenging for some people, he acknowledged. Over the last 18 months, Fountain House’s virtual clubhouse proved this theory wrong, Dr. Vasan said. “There are a great number of people with serious mental illness who have basic digital skills and are already using technology, or are very eager to learn,” he said.

For the subset of members who did get discouraged by the virtual platform, Fountain House responded by giving them one-on-one home support and digital literacy training to help them stay motivated and engaged.

Fountain House also expanded partnerships during the pandemic, working with programs such as the Fortune Society to bring people with SMI from the criminal justice system into Fountain House. “We’re doing this either virtually or through outdoor, public park programs with groups such as the Times Square Alliance and Fort Greene Park Conservancy to ensure we’re meeting people where they are, at a time of a rising health crisis,” Dr. Vasan said.

Moving on to a hybrid model

At the height of the pandemic, it was easy to engage members through creative programming. People were craving socialization. Now that people are getting vaccinated and interacting inside and outside, some understandable apathy is forming toward digital platforms, Dr. Vasan said.

“The onus is on us now to look at that data and to design something new that can keep people engaged in a hybrid model,” he added.

June 14, 2021, marked Fountain House’s soft opening. “This was a big day for us, to work through the kinks,” he said. At press time, the plan was to fully reopen the clubhouse in a few weeks – if transmission and case rates stay low.

It’s unclear at this point how many people will engage with Fountain House on a daily, in-person basis. Some people might want to come to the clubhouse just a few days a week and use the online platform on other days.

“We’re doing a series of experiments to really understand what different offerings we need to make. For example, perhaps we need to have 24-7 programming on the digital platform. That way, you could access it on demand,” said Dr. Vasan. The goal is to create a menu of choices for members so that it becomes flexible and meets their needs.

Long term, Dr. Vasan hopes the digital platform will become a scalable technology. “We want this to be used not just by Fountain House, but for programs and in markets that don’t have clubhouses.” Health systems or insurance companies would benefit from software like this because it addresses one of the most difficult aspects for this population: keeping them engaged and visible to their systems, Dr. Vasan added.

“I think the most important lesson here is we’re designing for a group of people that no one designs for. No one’s paying attention to people with serious mental illness. Nor have they ever, really. Fountain House has always been their advocate and partner. It’s great that we can do this with them, and for them.”

Dr. Vasan, also an epidemiologist, serves as assistant professor of clinical population, and family health and medicine, at Columbia University. Dr. London and Dr. Le Melle have no conflicts of interest.

Two steps back, three steps forward

For some of its members, Fountain House provides more than just a sense of place. In an interview, longtime member and New York City native Rich Courage, 61, discussed his mental illness challenges and the role the organization played in reclaiming his life, leading to a new career as a counselor.

Question: What made you seek out Fountain House? Are you still a member?

Rich Courage: I’ve been a member since 2001. I was in a day program at Postgraduate, on West 36th Street. They had this huge theater program, and I was a part of that. But the program fell apart and I didn’t know what to do with myself. A friend of mine told me about Fountain House. I asked what it did, and the friend said that it puts people with mental health challenges back to life, to work, to school. I was making some art, some collages, and I heard they had an art gallery.

Seeing Fountain House, I was amazed. It was this very friendly, warm, cozy place. The staff was nice; the members were welcoming. The next thing you know it’s 2021, and here I am, a peer counselor at Fountain House. I work on “the warm line,” doing the evening shift. People call in who have crises, but a lot of them call in because they’re lonely and want someone to talk to. As a peer counselor, I don’t tell people what to do, but I do offer support. I encourage. I ask questions that enable them to figure out their own problems. And I tell stories anecdotally of people that I’ve known and about recovery.

I struggled with bad depression when I was in my 20s. My mother died, and I lost everything. Coming to Fountain House and being part of this community is unlike anything I’d ever experienced. People weren’t just sitting around and talking about their problems; they were doing something about it. They were going back to school, to work, to social engagements, and the world at large. And it wasn’t perfect or linear. It was two steps back, three steps forward.

That’s exactly what I was doing. I had a lot of self-esteem and confidence issues, and behavioral stuff. My mind was wired a certain way. I had hospitalizations; I was in psychiatric wards. I had a suicide attempt in 2006, which was nearly successful. I was feeling social, mental, and emotional pain for so long. The community has been invaluable for me. Hearing other people’s stories, being accepted, has been wonderful.

I’ve been down and now I’m up, on an upward trajectory.

Question: How else has Fountain House made a difference in your life?

RC: I’m in a Fountain House residence in a one-bedroom, and it’s the most stable housing I’ve ever had in 61 years. So I’ve gotten housing and I’ve gotten a job, which is all great, because it’s aided me in becoming a full human being. But it’s really eased my suffering and enabled me to feel some joy and have some life instead of this shadow existence that I had been living for 30 years.

Fountain House has different units, and I’ve been in the communications unit – we put out the weekly paper and handle all the mail. The unit has computers, and I was able to work on my writing. I wrote a play called "The Very Last Dance of Homeless Joe." We’ve had staged readings at Fountain House, and 200 people have seen it over 2 years. We Zoomed it through the virtual community. It was very successful. A recording of the staged reading won third place at a festival in Florida.

In September, it will be an off-Broadway show. It’s a play about the homeless, but it’s not depressing; it’s very uplifting.

Question: Did you stay connected to Fountain House during the pandemic, either through the digital community or through services they provided? What was this experience like for you?

RC: Ashwin [Vasan] had been here 6 months, and he saw the pandemic coming. During a programming meeting he said, “We need a virtual community, and we need it now.” None of us knew what Zoom was, how the mute button worked. But it’s been wonderful for me. I’m a performer, so I was able to get on to Facebook every day and post a song. Some of it was spoofs about COVID; some were dedications to members. I ended up connecting with a member in Minnesota who used to be a neighbor of mine. We had lost contact, and we reconnected through Fountain House.

Question: What would you tell someone who might need this service?

RC: We’ve partially reopened the clubhouse. In July we’ll be doing tours again. I’d say, come take a tour and see the different social, economic, housing, and educational opportunities. We have a home and garden unit that decorates the place. We have a gym, a wellness unit. But these are just things. The real heart is the people.

As a unit leader recently told me, “We’re not a clinic. We’re not a revolving door. We forge relationships with members that last in our hearts and minds for a lifetime. Even if it’s not in my job description, if there’s anything in my power that I could do to help a member ease their suffering, I will do it.”

For more than 70 years, Fountain House has offered a lifeline for people living with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, and other serious mental illnesses through a community-based model of care. When he took the helm less than 2 years ago, CEO and President Ashwin Vasan, ScM, MD, PhD, wanted a greater focus on crisis-based solutions and a wider, public health approach.

That goal was put to the test in 2020, when SARS-CoV-2 shuttered all in-person activities. The nonprofit quickly rebounded, creating a digital platform, engaging with its members through online courses, face-to-face check-ins, and delivery services, and expanding partnerships to connect with individuals facing homelessness and involved in the criminal justice system. Those activities not only brought the community together – it expanded Fountain House’s footprint.

Among its membership of more than 2,000 people in New York City, about 70% connected to the digital platform. “We also enrolled more than 200 brand new members during the pandemic who had never set foot in the physical mental health “clubhouse.” They derived value as well,” Dr. Vasan said in an interview. Nationally, the program is replicated at more than 200 locations and serves about 60,000 people in almost 40 states. During the pandemic, Fountain House began formalizing affiliation opportunities with this network.

Now that the pandemic is showing signs of receding, Fountain House faces new challenges operating as a possible hybrid model. “More than three-quarters of our members say they want to continue to engage virtually as well as in person,” Dr. Vasan said. As of this writing, Fountain House is enjoying a soft reopening, slowly welcoming in-person activities. What this will look like in the coming weeks and months is a work in progress, he added. “We don’t know yet how people are going to prefer to engage.”

A role in the public policy conversation

Founded by a small group of former psychiatric patients in the late 1940s, Fountain House has since expanded from a single building in New York City to more than 300 replications in the United States and around the world. It originated the “clubhouse” model of mental health support: a community-based approach that helps members improve health, and break social and economic isolation by reclaiming social, educational, and work skills, and connecting with core services, including supportive housing and community-based primary and behavioral health care (Arts Psychother. 2012 Feb 39[1]:25-30).

Serious mental illness (SMI) is growing more pronounced as a crisis, not just in the people it affects, “but in all of the attendant and preventable social and economic crises that intersect with it, whether it’s increasing health care costs, homelessness, or criminalization,” Dr. Vasan said.

After 73 years, Fountain House is just beginning to gain relevance as a tool to help solve these intersecting public policy crises, he added.

“We’ve demonstrated through evaluation data that it reduces hospitalization rates, health care costs, reliance on emergency departments, homelessness, and recidivism to the criminal justice system,” he said. Health care costs for members are more than 20% lower than for others with mental illness, and recidivism rates among those with a criminal history are less than 5%.

Others familiar with Fountain House say the model delivers on its charge to improve quality of life for people with SMI.

It’s a great referral source for people who are under good mental health control, whether it’s therapy or a combination of therapy and medications, Robert T. London, MD, a practicing psychiatrist in New York who is not affiliated with Fountain House but has referred patients to the organization over the years, said in an interview.

“They can work with staff, learn skills regarding potential work, housekeeping, [and] social skills,” he said. One of the biggest problems facing people with SMI is they’re very isolated, Dr. London continued. “When you’re in a facility like Fountain House, you’re not isolated. You’re with fellow members, a very helpful educated staff, and you’re going to do well.” If a member is having some issues and losing touch with reality and needs to find treatment, Fountain House will provide that support.

“If you don’t have a treating person, they’re going to find you one. They’re not against traditional medical/psychiatric care,” he said.

Among those with unstable or no housing, 99% find housing within a year of joining Fountain House. While it does provide people with SMI with support to find a roof over their heads, Fountain House doesn’t necessarily fit a model of “housing first,” Stephanie Le Melle, MD, MS, director of public psychiatry education at department of psychiatry at Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute, said in an interview.

“The housing first evidence-based model, as designed and implemented by Pathways to Housing program in New York in the early 90s, accepted people who were street homeless or in shelters, not involved in mental health treatment, and actively using substances into scatter-site apartments and wrapped services around them,” she said.

Dr. Le Melle, who is not affiliated with Fountain House, views it more as a supportive employment program that uses a recovery-oriented, community-based, jointly peer-run approach to engage members in vocational/educational programming. It also happens to have some supportive housing for its members, she added.

Dr. Vasan believes Fountain House could expand beyond a community model. The organization has been moving out from its history, evolving into a model that could be integrated as standard of care and standard of practice for community health, he said. Fountain House is part of Clubhouse International, an umbrella organization that received the American Psychiatric Association’s 2021 special presidential commendation award during its virtual annual meeting for the group’s use of “the evidence-based, cost-effective clubhouse model of psychosocial rehabilitation as a leading recovery resource for people living with mental illness around the world.”

How medication issues are handled

Fountain House doesn’t directly provide medication to its members. According to Dr. Vasan, psychiatric care is just one component of recovery for serious mental illness.

“We talk about Fountain House as a main vortex in a triangle of recovery. You need health care, housing, and community. The part that’s been neglected the most is community intervention, the social infrastructure for people who are deeply isolated and marginalized,” he said. “We know that people who have that infrastructure, and are stably housed, are then more likely to engage in community-based psychiatry and primary care. And in turn, people who are in stable clinical care can more durably engage in the community programming Fountain House offers.”

Health care and clinical care are changing. It’s becoming more person-centered and community based. “We need to move with the times and we have, in the last 2 decades,” he said.

Historically, Fountain House has owned and operated its own clinic in New York City. More recently, it partnered with Sun River Health and Ryan Health, two large federally qualified health center networks in New York, so that members receive access to psychiatric and medical care. It has also expanded similar partnerships with Columbia University, New York University, and other health care systems to ensure its members have access to sustainable clinical care as a part of the community conditions and resources needed to recover and thrive.

Those familiar with the organization don’t see the absence of a medication program as a negative factor. If Fountain House doesn’t provide psychiatric medications, “that tells me the patients are under control and able to function in a community setting” that focuses on rehabilitation, Dr. London said.

It’s true that psychiatric medication treatment is an essential part of a patient’s recovery journey, Dr. Le Melle said. “Treatment with medications can be done in a recovery-oriented way. However, the Fountain House model has been designed to keep these separate, and this model works well for most” of the members.

As long as members and staff are willing to collaborate with treatment providers outside of the clubhouse, when necessary, this model of separation between work and treatment can work really well, she added.

“There are some people who need a more integrated system of care. There is no ‘one size fits all’ program that can meet everyone’s needs,” said Dr. Le Melle. The absence of onsite treatment at Fountain House, to some extent “adds to the milieu and allows people to focus on other aspects of their lives besides their illness.”

This hasn’t always been the case in traditionally funded behavioral health programs, she continued. Most mental health clinics, because of fiscal structures, reimbursement, and staffing costs, focus more on psychotherapy and medication management than on other aspects of peoples’ lives, such as their recovery goals.

The bottom line is rehabilitation in medicine works – whether it’s for a mental health disorder, broken leg, arm, or stroke, Dr. London said. “Fountain House’s focus is integrating a person into society by helping them to think differently and interact socially in groups and learn some skills.”

Through cognitive-behavioral therapies, a person with mental illness can learn how to act differently. “The brain is always in a growing process where you learn and develop new ideas, make connections,” Dr. London said. “New protein molecules get created and stored; changes occur with the neurotransmitters.”

Overall, the Fountain House model is great for supporting and engaging people with serious mental illness, Dr. Le Melle said. “It provides a literal place, a community, and a safe environment that helps people to embrace their recovery journey. It is also great at supporting people in their engagement with vocational training and employment.”

Ideally, she would like Fountain House to grow and become more inclusive by engaging people who live with both mental illness and substance use.

COVID-19 changes the rules

The most difficult challenge for health care and other institutions is to keep individuals with SMI engaged and visible so that they can find access to health care and benefits – and avoid acute hospitalization or medical care. “That’s our goal, to prevent the worst effects and respond accordingly,” Dr. Vasan said.

SARS-CoV-2 forced the program to reevaluate its daily operations so that it could maintain crucial connections with its members.

Dr. Vasan and his staff immediately closed the clubhouse when COVID-19 first hit, transitioning to direct community-based services that provided one-on-one outreach, and meal, medication, and clothing delivery. “Even if people couldn’t visit our clubhouse, we wanted them to feel that sense of community connection, even if it was to drop off meals at their doorstep,” he said.

Donning personal protective equipment, his staff and interested program participants went out into the communities to do this personal outreach. At the height of pandemic in New York City, “we weren’t sure what to do,” as far as keeping safe, he admitted. Nevertheless, he believes this outreach work was lifesaving in that it kept people connected to the clubhouse.

As Fountain House worked to maintain in-person contact, it also built a digital community to keep the live community together. This wasn’t just about posting on a Facebook page – it was interactive, Dr. Vasan noted. An online group made masks for the community and sold them for people outside of Fountain House. Capacity building courses instructed members on writing resumes, looking for jobs, or filling out applications.

There’s an assumption that people with SMI lack the skills to navigate technology. Some of the hallmarks of SMI are demotivation and lack of confidence, and logging onto platforms and email can be challenging for some people, he acknowledged. Over the last 18 months, Fountain House’s virtual clubhouse proved this theory wrong, Dr. Vasan said. “There are a great number of people with serious mental illness who have basic digital skills and are already using technology, or are very eager to learn,” he said.

For the subset of members who did get discouraged by the virtual platform, Fountain House responded by giving them one-on-one home support and digital literacy training to help them stay motivated and engaged.

Fountain House also expanded partnerships during the pandemic, working with programs such as the Fortune Society to bring people with SMI from the criminal justice system into Fountain House. “We’re doing this either virtually or through outdoor, public park programs with groups such as the Times Square Alliance and Fort Greene Park Conservancy to ensure we’re meeting people where they are, at a time of a rising health crisis,” Dr. Vasan said.

Moving on to a hybrid model

At the height of the pandemic, it was easy to engage members through creative programming. People were craving socialization. Now that people are getting vaccinated and interacting inside and outside, some understandable apathy is forming toward digital platforms, Dr. Vasan said.

“The onus is on us now to look at that data and to design something new that can keep people engaged in a hybrid model,” he added.

June 14, 2021, marked Fountain House’s soft opening. “This was a big day for us, to work through the kinks,” he said. At press time, the plan was to fully reopen the clubhouse in a few weeks – if transmission and case rates stay low.

It’s unclear at this point how many people will engage with Fountain House on a daily, in-person basis. Some people might want to come to the clubhouse just a few days a week and use the online platform on other days.

“We’re doing a series of experiments to really understand what different offerings we need to make. For example, perhaps we need to have 24-7 programming on the digital platform. That way, you could access it on demand,” said Dr. Vasan. The goal is to create a menu of choices for members so that it becomes flexible and meets their needs.

Long term, Dr. Vasan hopes the digital platform will become a scalable technology. “We want this to be used not just by Fountain House, but for programs and in markets that don’t have clubhouses.” Health systems or insurance companies would benefit from software like this because it addresses one of the most difficult aspects for this population: keeping them engaged and visible to their systems, Dr. Vasan added.

“I think the most important lesson here is we’re designing for a group of people that no one designs for. No one’s paying attention to people with serious mental illness. Nor have they ever, really. Fountain House has always been their advocate and partner. It’s great that we can do this with them, and for them.”

Dr. Vasan, also an epidemiologist, serves as assistant professor of clinical population, and family health and medicine, at Columbia University. Dr. London and Dr. Le Melle have no conflicts of interest.

Two steps back, three steps forward

For some of its members, Fountain House provides more than just a sense of place. In an interview, longtime member and New York City native Rich Courage, 61, discussed his mental illness challenges and the role the organization played in reclaiming his life, leading to a new career as a counselor.

Question: What made you seek out Fountain House? Are you still a member?

Rich Courage: I’ve been a member since 2001. I was in a day program at Postgraduate, on West 36th Street. They had this huge theater program, and I was a part of that. But the program fell apart and I didn’t know what to do with myself. A friend of mine told me about Fountain House. I asked what it did, and the friend said that it puts people with mental health challenges back to life, to work, to school. I was making some art, some collages, and I heard they had an art gallery.

Seeing Fountain House, I was amazed. It was this very friendly, warm, cozy place. The staff was nice; the members were welcoming. The next thing you know it’s 2021, and here I am, a peer counselor at Fountain House. I work on “the warm line,” doing the evening shift. People call in who have crises, but a lot of them call in because they’re lonely and want someone to talk to. As a peer counselor, I don’t tell people what to do, but I do offer support. I encourage. I ask questions that enable them to figure out their own problems. And I tell stories anecdotally of people that I’ve known and about recovery.

I struggled with bad depression when I was in my 20s. My mother died, and I lost everything. Coming to Fountain House and being part of this community is unlike anything I’d ever experienced. People weren’t just sitting around and talking about their problems; they were doing something about it. They were going back to school, to work, to social engagements, and the world at large. And it wasn’t perfect or linear. It was two steps back, three steps forward.

That’s exactly what I was doing. I had a lot of self-esteem and confidence issues, and behavioral stuff. My mind was wired a certain way. I had hospitalizations; I was in psychiatric wards. I had a suicide attempt in 2006, which was nearly successful. I was feeling social, mental, and emotional pain for so long. The community has been invaluable for me. Hearing other people’s stories, being accepted, has been wonderful.

I’ve been down and now I’m up, on an upward trajectory.

Question: How else has Fountain House made a difference in your life?

RC: I’m in a Fountain House residence in a one-bedroom, and it’s the most stable housing I’ve ever had in 61 years. So I’ve gotten housing and I’ve gotten a job, which is all great, because it’s aided me in becoming a full human being. But it’s really eased my suffering and enabled me to feel some joy and have some life instead of this shadow existence that I had been living for 30 years.

Fountain House has different units, and I’ve been in the communications unit – we put out the weekly paper and handle all the mail. The unit has computers, and I was able to work on my writing. I wrote a play called "The Very Last Dance of Homeless Joe." We’ve had staged readings at Fountain House, and 200 people have seen it over 2 years. We Zoomed it through the virtual community. It was very successful. A recording of the staged reading won third place at a festival in Florida.

In September, it will be an off-Broadway show. It’s a play about the homeless, but it’s not depressing; it’s very uplifting.

Question: Did you stay connected to Fountain House during the pandemic, either through the digital community or through services they provided? What was this experience like for you?

RC: Ashwin [Vasan] had been here 6 months, and he saw the pandemic coming. During a programming meeting he said, “We need a virtual community, and we need it now.” None of us knew what Zoom was, how the mute button worked. But it’s been wonderful for me. I’m a performer, so I was able to get on to Facebook every day and post a song. Some of it was spoofs about COVID; some were dedications to members. I ended up connecting with a member in Minnesota who used to be a neighbor of mine. We had lost contact, and we reconnected through Fountain House.

Question: What would you tell someone who might need this service?

RC: We’ve partially reopened the clubhouse. In July we’ll be doing tours again. I’d say, come take a tour and see the different social, economic, housing, and educational opportunities. We have a home and garden unit that decorates the place. We have a gym, a wellness unit. But these are just things. The real heart is the people.

As a unit leader recently told me, “We’re not a clinic. We’re not a revolving door. We forge relationships with members that last in our hearts and minds for a lifetime. Even if it’s not in my job description, if there’s anything in my power that I could do to help a member ease their suffering, I will do it.”

For more than 70 years, Fountain House has offered a lifeline for people living with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, and other serious mental illnesses through a community-based model of care. When he took the helm less than 2 years ago, CEO and President Ashwin Vasan, ScM, MD, PhD, wanted a greater focus on crisis-based solutions and a wider, public health approach.

That goal was put to the test in 2020, when SARS-CoV-2 shuttered all in-person activities. The nonprofit quickly rebounded, creating a digital platform, engaging with its members through online courses, face-to-face check-ins, and delivery services, and expanding partnerships to connect with individuals facing homelessness and involved in the criminal justice system. Those activities not only brought the community together – it expanded Fountain House’s footprint.

Among its membership of more than 2,000 people in New York City, about 70% connected to the digital platform. “We also enrolled more than 200 brand new members during the pandemic who had never set foot in the physical mental health “clubhouse.” They derived value as well,” Dr. Vasan said in an interview. Nationally, the program is replicated at more than 200 locations and serves about 60,000 people in almost 40 states. During the pandemic, Fountain House began formalizing affiliation opportunities with this network.

Now that the pandemic is showing signs of receding, Fountain House faces new challenges operating as a possible hybrid model. “More than three-quarters of our members say they want to continue to engage virtually as well as in person,” Dr. Vasan said. As of this writing, Fountain House is enjoying a soft reopening, slowly welcoming in-person activities. What this will look like in the coming weeks and months is a work in progress, he added. “We don’t know yet how people are going to prefer to engage.”

A role in the public policy conversation

Founded by a small group of former psychiatric patients in the late 1940s, Fountain House has since expanded from a single building in New York City to more than 300 replications in the United States and around the world. It originated the “clubhouse” model of mental health support: a community-based approach that helps members improve health, and break social and economic isolation by reclaiming social, educational, and work skills, and connecting with core services, including supportive housing and community-based primary and behavioral health care (Arts Psychother. 2012 Feb 39[1]:25-30).

Serious mental illness (SMI) is growing more pronounced as a crisis, not just in the people it affects, “but in all of the attendant and preventable social and economic crises that intersect with it, whether it’s increasing health care costs, homelessness, or criminalization,” Dr. Vasan said.

After 73 years, Fountain House is just beginning to gain relevance as a tool to help solve these intersecting public policy crises, he added.

“We’ve demonstrated through evaluation data that it reduces hospitalization rates, health care costs, reliance on emergency departments, homelessness, and recidivism to the criminal justice system,” he said. Health care costs for members are more than 20% lower than for others with mental illness, and recidivism rates among those with a criminal history are less than 5%.

Others familiar with Fountain House say the model delivers on its charge to improve quality of life for people with SMI.

It’s a great referral source for people who are under good mental health control, whether it’s therapy or a combination of therapy and medications, Robert T. London, MD, a practicing psychiatrist in New York who is not affiliated with Fountain House but has referred patients to the organization over the years, said in an interview.

“They can work with staff, learn skills regarding potential work, housekeeping, [and] social skills,” he said. One of the biggest problems facing people with SMI is they’re very isolated, Dr. London continued. “When you’re in a facility like Fountain House, you’re not isolated. You’re with fellow members, a very helpful educated staff, and you’re going to do well.” If a member is having some issues and losing touch with reality and needs to find treatment, Fountain House will provide that support.

“If you don’t have a treating person, they’re going to find you one. They’re not against traditional medical/psychiatric care,” he said.

Among those with unstable or no housing, 99% find housing within a year of joining Fountain House. While it does provide people with SMI with support to find a roof over their heads, Fountain House doesn’t necessarily fit a model of “housing first,” Stephanie Le Melle, MD, MS, director of public psychiatry education at department of psychiatry at Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute, said in an interview.