User login

Two Ebola vaccines effective, safe in phase I trials

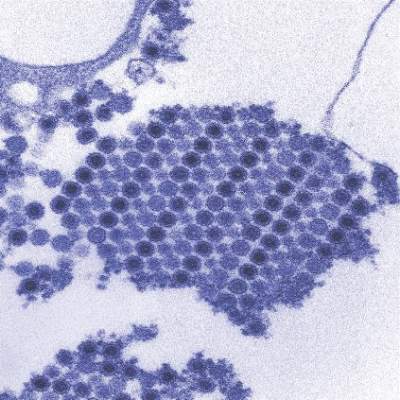

Two Ebola vaccines were found safe and effective in separate international phase I trials involving healthy European and African adults, according to two reports published online April 27 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After further testing and confirmation of these preliminary results, both vaccines should prove useful in both preventing and controlling future outbreaks, both research groups said.

Several vaccines showed promise in previous primate and preliminary human studies, including one expressing the surface glycoprotein of Zaire ebolavirus (ZEBOV). Different versions of this vaccine were assessed in the present phase I studies.

In the first trial, investigators sought to extend the durability of this vaccine by administering a single “priming” dose of the chimpanzee adenovirus 3 (ChAd3) vaccine encoding the ZEBOV surface glycoprotein, then giving a “booster” with a modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) strain either 1 or 2 weeks later. The participants, 60 healthy adults aged 18-50 years, were randomly assigned to receive a low dose (20 subjects), an intermediate dose (20 subjects), or a high dose (20 subjects) of viral particles. Ten participants from each of these dose groups were then offered the booster. Then two additional groups of eight participants each were assessed to see whether giving the booster at 1 week vs. at 2 weeks made a difference in immunogenicity or safety.

All the study groups showed both antibody and T-cell immunogenicity after vaccination, but the groups that received the boosters showed antibody responses four times higher than those who did not. The MVA booster increased virus-specific antibodies by a factor of 12, and significantly increased neutralizing antibodies as well, said Dr. Katie Ewer of the Jenner Institute and Centre for Clinical Vaccinology and Tropical Medicine, University of Oxford (England) and the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and her associates.

The boosters also improved the vaccine’s cell-mediated immunity, increasing glycoprotein-specific CD8+ T cells by a factor of five.

In addition, the MVA booster markedly improved the vaccine’s durability, with 100% of recipients continuing to show seropositivity at 6 months, compared with only 50%-74% of participants who did not receive the booster.

The safety profile of the vaccine and the booster were termed “acceptable” at all dose levels and at all dosing intervals studied. There were no serious adverse events, and most adverse events were self-limited and mild. Moderate systemic adverse events included transient fever, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, fatigue, nausea, and malaise. Regarding laboratory abnormalities, four patients showed prolonged activated partial-thromboplastin time without coagulopathy, all of which resolved within 10 weeks; several patients showed mild or moderate lymphocytopenia and mild or moderate elevations in bilirubin, all of which were transient.

Overall, “We found that boosting can be immunogenic for antibodies and T cells at prime-boost intervals as short as 1 week. Such short-interval regimens may facilitate vaccine deployment in outbreak settings where both rapid onset and durable vaccine efficacy are required,” Dr. Ewer and her associates noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411627).

They added that the ChAd3-plus-MVA viral vectors have other practical advantages. “Large-scale manufacturing processes concordant with Good Manufacturing Practice standards have been established, and both vectors have been assessed in large numbers of vaccines for a range of indications, without reports of any substantial safety concerns to date,” Dr. Ewer and her coauthors said.

The second report concerned four parallel studies: three open-label dose-escalation studies in Gabon, Kenya, and Germany and one randomized, double-blind trial in Geneva assessing the safety and immunogenicity of several doses of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV)-vectored ZEBOV. The 158 participants were followed for at least 6 months, said Dr. Selidji T. Agnandji of the Centre de Recherches Medicales de Lambarene (Gabon), the Institut für Tropenmedizin, Universitätsklinikum Tübingen (Germany), and the German Center for Infection Research, Tübingen, and his associates.

The vaccine was immunogenic in all participants across every dose and every study site, with higher glycoprotein-binding antibody titers at higher doses. These antibodies persisted through 6 months, a “promising” result suggesting that a single dose of this vaccine may be sufficient for early and possibly for long-term protection, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502924).

Although there were no serious adverse events associated with this vaccine, acute vaccine reactions were common: 92% of patients reported an acute reaction, and 10%-22% (depending on the study site) reported grade 3 symptoms. The most bothersome – and unexpected – reactions involved viral seeding of joints and skin.

The joint problems manifested as arthritis, tenosynovitis, or bursitis that appeared at a median of 11 days after injection. The arthritis tended to affect one to four peripheral joints asymmetrically; pain was usually mild and dysfunction was usually moderate. Ten of the 11 affected patients in Geneva and both of the two (out of 60) affected patients at the other sites were symptom-free by 6 months. These findings “suggest a favorable long-term prognosis for these vaccine-induced arthritides,” Dr. Agnandji and his associates said.

Three participants developed maculopapular rashes mainly affecting the limbs, which appeared at 7-9 days following injection and persisted for 1-2 weeks. The rash was accompanied by a few tender vesicles on fingers or toes. Synovial fluid extracted from affected joints and material recovered from skin vesicles showed the presence of rVSV.

Given that most adverse reactions occurred soon after vaccination, were of short duration, and were amenable to treatment, this vaccine demonstrated “a favorable risk-benefit balance,” they added.

Two Ebola vaccines were found safe and effective in separate international phase I trials involving healthy European and African adults, according to two reports published online April 27 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After further testing and confirmation of these preliminary results, both vaccines should prove useful in both preventing and controlling future outbreaks, both research groups said.

Several vaccines showed promise in previous primate and preliminary human studies, including one expressing the surface glycoprotein of Zaire ebolavirus (ZEBOV). Different versions of this vaccine were assessed in the present phase I studies.

In the first trial, investigators sought to extend the durability of this vaccine by administering a single “priming” dose of the chimpanzee adenovirus 3 (ChAd3) vaccine encoding the ZEBOV surface glycoprotein, then giving a “booster” with a modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) strain either 1 or 2 weeks later. The participants, 60 healthy adults aged 18-50 years, were randomly assigned to receive a low dose (20 subjects), an intermediate dose (20 subjects), or a high dose (20 subjects) of viral particles. Ten participants from each of these dose groups were then offered the booster. Then two additional groups of eight participants each were assessed to see whether giving the booster at 1 week vs. at 2 weeks made a difference in immunogenicity or safety.

All the study groups showed both antibody and T-cell immunogenicity after vaccination, but the groups that received the boosters showed antibody responses four times higher than those who did not. The MVA booster increased virus-specific antibodies by a factor of 12, and significantly increased neutralizing antibodies as well, said Dr. Katie Ewer of the Jenner Institute and Centre for Clinical Vaccinology and Tropical Medicine, University of Oxford (England) and the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and her associates.

The boosters also improved the vaccine’s cell-mediated immunity, increasing glycoprotein-specific CD8+ T cells by a factor of five.

In addition, the MVA booster markedly improved the vaccine’s durability, with 100% of recipients continuing to show seropositivity at 6 months, compared with only 50%-74% of participants who did not receive the booster.

The safety profile of the vaccine and the booster were termed “acceptable” at all dose levels and at all dosing intervals studied. There were no serious adverse events, and most adverse events were self-limited and mild. Moderate systemic adverse events included transient fever, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, fatigue, nausea, and malaise. Regarding laboratory abnormalities, four patients showed prolonged activated partial-thromboplastin time without coagulopathy, all of which resolved within 10 weeks; several patients showed mild or moderate lymphocytopenia and mild or moderate elevations in bilirubin, all of which were transient.

Overall, “We found that boosting can be immunogenic for antibodies and T cells at prime-boost intervals as short as 1 week. Such short-interval regimens may facilitate vaccine deployment in outbreak settings where both rapid onset and durable vaccine efficacy are required,” Dr. Ewer and her associates noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411627).

They added that the ChAd3-plus-MVA viral vectors have other practical advantages. “Large-scale manufacturing processes concordant with Good Manufacturing Practice standards have been established, and both vectors have been assessed in large numbers of vaccines for a range of indications, without reports of any substantial safety concerns to date,” Dr. Ewer and her coauthors said.

The second report concerned four parallel studies: three open-label dose-escalation studies in Gabon, Kenya, and Germany and one randomized, double-blind trial in Geneva assessing the safety and immunogenicity of several doses of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV)-vectored ZEBOV. The 158 participants were followed for at least 6 months, said Dr. Selidji T. Agnandji of the Centre de Recherches Medicales de Lambarene (Gabon), the Institut für Tropenmedizin, Universitätsklinikum Tübingen (Germany), and the German Center for Infection Research, Tübingen, and his associates.

The vaccine was immunogenic in all participants across every dose and every study site, with higher glycoprotein-binding antibody titers at higher doses. These antibodies persisted through 6 months, a “promising” result suggesting that a single dose of this vaccine may be sufficient for early and possibly for long-term protection, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502924).

Although there were no serious adverse events associated with this vaccine, acute vaccine reactions were common: 92% of patients reported an acute reaction, and 10%-22% (depending on the study site) reported grade 3 symptoms. The most bothersome – and unexpected – reactions involved viral seeding of joints and skin.

The joint problems manifested as arthritis, tenosynovitis, or bursitis that appeared at a median of 11 days after injection. The arthritis tended to affect one to four peripheral joints asymmetrically; pain was usually mild and dysfunction was usually moderate. Ten of the 11 affected patients in Geneva and both of the two (out of 60) affected patients at the other sites were symptom-free by 6 months. These findings “suggest a favorable long-term prognosis for these vaccine-induced arthritides,” Dr. Agnandji and his associates said.

Three participants developed maculopapular rashes mainly affecting the limbs, which appeared at 7-9 days following injection and persisted for 1-2 weeks. The rash was accompanied by a few tender vesicles on fingers or toes. Synovial fluid extracted from affected joints and material recovered from skin vesicles showed the presence of rVSV.

Given that most adverse reactions occurred soon after vaccination, were of short duration, and were amenable to treatment, this vaccine demonstrated “a favorable risk-benefit balance,” they added.

Two Ebola vaccines were found safe and effective in separate international phase I trials involving healthy European and African adults, according to two reports published online April 27 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After further testing and confirmation of these preliminary results, both vaccines should prove useful in both preventing and controlling future outbreaks, both research groups said.

Several vaccines showed promise in previous primate and preliminary human studies, including one expressing the surface glycoprotein of Zaire ebolavirus (ZEBOV). Different versions of this vaccine were assessed in the present phase I studies.

In the first trial, investigators sought to extend the durability of this vaccine by administering a single “priming” dose of the chimpanzee adenovirus 3 (ChAd3) vaccine encoding the ZEBOV surface glycoprotein, then giving a “booster” with a modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) strain either 1 or 2 weeks later. The participants, 60 healthy adults aged 18-50 years, were randomly assigned to receive a low dose (20 subjects), an intermediate dose (20 subjects), or a high dose (20 subjects) of viral particles. Ten participants from each of these dose groups were then offered the booster. Then two additional groups of eight participants each were assessed to see whether giving the booster at 1 week vs. at 2 weeks made a difference in immunogenicity or safety.

All the study groups showed both antibody and T-cell immunogenicity after vaccination, but the groups that received the boosters showed antibody responses four times higher than those who did not. The MVA booster increased virus-specific antibodies by a factor of 12, and significantly increased neutralizing antibodies as well, said Dr. Katie Ewer of the Jenner Institute and Centre for Clinical Vaccinology and Tropical Medicine, University of Oxford (England) and the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and her associates.

The boosters also improved the vaccine’s cell-mediated immunity, increasing glycoprotein-specific CD8+ T cells by a factor of five.

In addition, the MVA booster markedly improved the vaccine’s durability, with 100% of recipients continuing to show seropositivity at 6 months, compared with only 50%-74% of participants who did not receive the booster.

The safety profile of the vaccine and the booster were termed “acceptable” at all dose levels and at all dosing intervals studied. There were no serious adverse events, and most adverse events were self-limited and mild. Moderate systemic adverse events included transient fever, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, fatigue, nausea, and malaise. Regarding laboratory abnormalities, four patients showed prolonged activated partial-thromboplastin time without coagulopathy, all of which resolved within 10 weeks; several patients showed mild or moderate lymphocytopenia and mild or moderate elevations in bilirubin, all of which were transient.

Overall, “We found that boosting can be immunogenic for antibodies and T cells at prime-boost intervals as short as 1 week. Such short-interval regimens may facilitate vaccine deployment in outbreak settings where both rapid onset and durable vaccine efficacy are required,” Dr. Ewer and her associates noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411627).

They added that the ChAd3-plus-MVA viral vectors have other practical advantages. “Large-scale manufacturing processes concordant with Good Manufacturing Practice standards have been established, and both vectors have been assessed in large numbers of vaccines for a range of indications, without reports of any substantial safety concerns to date,” Dr. Ewer and her coauthors said.

The second report concerned four parallel studies: three open-label dose-escalation studies in Gabon, Kenya, and Germany and one randomized, double-blind trial in Geneva assessing the safety and immunogenicity of several doses of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV)-vectored ZEBOV. The 158 participants were followed for at least 6 months, said Dr. Selidji T. Agnandji of the Centre de Recherches Medicales de Lambarene (Gabon), the Institut für Tropenmedizin, Universitätsklinikum Tübingen (Germany), and the German Center for Infection Research, Tübingen, and his associates.

The vaccine was immunogenic in all participants across every dose and every study site, with higher glycoprotein-binding antibody titers at higher doses. These antibodies persisted through 6 months, a “promising” result suggesting that a single dose of this vaccine may be sufficient for early and possibly for long-term protection, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502924).

Although there were no serious adverse events associated with this vaccine, acute vaccine reactions were common: 92% of patients reported an acute reaction, and 10%-22% (depending on the study site) reported grade 3 symptoms. The most bothersome – and unexpected – reactions involved viral seeding of joints and skin.

The joint problems manifested as arthritis, tenosynovitis, or bursitis that appeared at a median of 11 days after injection. The arthritis tended to affect one to four peripheral joints asymmetrically; pain was usually mild and dysfunction was usually moderate. Ten of the 11 affected patients in Geneva and both of the two (out of 60) affected patients at the other sites were symptom-free by 6 months. These findings “suggest a favorable long-term prognosis for these vaccine-induced arthritides,” Dr. Agnandji and his associates said.

Three participants developed maculopapular rashes mainly affecting the limbs, which appeared at 7-9 days following injection and persisted for 1-2 weeks. The rash was accompanied by a few tender vesicles on fingers or toes. Synovial fluid extracted from affected joints and material recovered from skin vesicles showed the presence of rVSV.

Given that most adverse reactions occurred soon after vaccination, were of short duration, and were amenable to treatment, this vaccine demonstrated “a favorable risk-benefit balance,” they added.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Two Ebola vaccines were found effective and safe in separate international phase I trials.

Major finding: The ChAd3 vaccine boosted with MVA elicited B-cell and T-cell immune responses to ZEBOV that were superior to those induced by the ChAd3 vaccine alone. The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine was reactogenic but immunogenic after a single dose.

Data source: A single dose of the chimpanzee adenovirus 3 (ChAd3) vaccine encoding the surface glycoprotein of Zaire ebolavirus (ZEBOV) was given to 60 healthy adult volunteers in Oxford, England. Three open-label, dose-escalation phase I trials and one randomized, double-blind, controlled phase I trial to assess the safety, side-effect profile, and immunogenicity of rVSV-ZEBOV at various doses in 158 healthy adults in Europe and Africa.

Disclosures: Dr. Ewer’s study was supported by the Wellcome Trust, the U. K. Medical Research Council, the U. K. Department for International Development, the U. K. National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the National Health Service Blood and Transplant, and Public Health England. The ChAd3 vaccine was provided by the U.S. Vaccine Research Center of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and GlaxoSmithKline, and the MVA vaccine booster was provided by the NIAID and Fisher BioServices. Dr. Ewer reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates reported ties to GlaxoSmithKline and patents pending related to these and other vaccines. Dr. Agnandji’s study was supported by the Wellcome Trust, the German Center for Infection Research, the German National Department for Education and Research, the German Ministry of Health, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Universitätsklinikum Tübingen, the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science, Research, and Economy, and the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine used in this study was donated by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the World Health Organization. Dr. Agnandji reported having no relevant financial disclosures; his associates reported ties to Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sanaria, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

CDC issues guidance on worker precautions against Zika virus

As the Zika virus continues to spread, officials at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have created a list of precautions to help outdoor workers, healthcare and laboratory personnel, and mosquito control workers avoid infection.

For outdoor workers, the prevention strategies center around using insect repellents, wearing clothing that provides a barrier against mosquitoes, and removing sources of standing water. For people working in healthcare settings and laboratories, OSHA and the CDC urge following good infection control and biosafety practices, including universal precautions to minimize the transmission of Zika virus, and when appropriate to wear gloves, gowns, masks, and eye protection.

Outdoor workers could be at the highest risk of catching the Zika virus, according to the guidance document.

Taking precautions to avoid mosquito bites is especially important when traveling to a Zika-affected area. OSHA and CDC also advised that workers should consider delaying travel if they may become pregnant, or have sexual partners who may become pregnant. The CDC recommends that pregnant women in any trimester avoid travel to an area with active Zika virus transmission.

“Even if they do not feel sick, travelers returning to the United States from an area with Zika should take steps to prevent mosquito bites for three weeks so they do not pass Zika to mosquitoes that could spread the virus to other people,” according to the guidance.

To find more information, click here.

As the Zika virus continues to spread, officials at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have created a list of precautions to help outdoor workers, healthcare and laboratory personnel, and mosquito control workers avoid infection.

For outdoor workers, the prevention strategies center around using insect repellents, wearing clothing that provides a barrier against mosquitoes, and removing sources of standing water. For people working in healthcare settings and laboratories, OSHA and the CDC urge following good infection control and biosafety practices, including universal precautions to minimize the transmission of Zika virus, and when appropriate to wear gloves, gowns, masks, and eye protection.

Outdoor workers could be at the highest risk of catching the Zika virus, according to the guidance document.

Taking precautions to avoid mosquito bites is especially important when traveling to a Zika-affected area. OSHA and CDC also advised that workers should consider delaying travel if they may become pregnant, or have sexual partners who may become pregnant. The CDC recommends that pregnant women in any trimester avoid travel to an area with active Zika virus transmission.

“Even if they do not feel sick, travelers returning to the United States from an area with Zika should take steps to prevent mosquito bites for three weeks so they do not pass Zika to mosquitoes that could spread the virus to other people,” according to the guidance.

To find more information, click here.

As the Zika virus continues to spread, officials at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have created a list of precautions to help outdoor workers, healthcare and laboratory personnel, and mosquito control workers avoid infection.

For outdoor workers, the prevention strategies center around using insect repellents, wearing clothing that provides a barrier against mosquitoes, and removing sources of standing water. For people working in healthcare settings and laboratories, OSHA and the CDC urge following good infection control and biosafety practices, including universal precautions to minimize the transmission of Zika virus, and when appropriate to wear gloves, gowns, masks, and eye protection.

Outdoor workers could be at the highest risk of catching the Zika virus, according to the guidance document.

Taking precautions to avoid mosquito bites is especially important when traveling to a Zika-affected area. OSHA and CDC also advised that workers should consider delaying travel if they may become pregnant, or have sexual partners who may become pregnant. The CDC recommends that pregnant women in any trimester avoid travel to an area with active Zika virus transmission.

“Even if they do not feel sick, travelers returning to the United States from an area with Zika should take steps to prevent mosquito bites for three weeks so they do not pass Zika to mosquitoes that could spread the virus to other people,” according to the guidance.

To find more information, click here.

CDC: Zika infection unlikely in asymptomatic people, but test pregnant women

Although the likelihood of Zika virus infection is low among asymptomatic patients, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends offering Zika virus testing to asymptomatic pregnant women with potential exposure.

The recommendation is based on Zika virus testing performed in U.S. states and the District of Columbia from Jan. 3 to March 5, 2016. The analysis included specimens that were received for testing at the CDC Arboviral Diseases Branch and confirmed Zika virus infection was defined as detection of Zika virus RNA by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, or anti-Zika immunoglobulin M antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with neutralizing antibody titers against Zika virus, at levels greater than or equal to fourfold higher than those against dengue virus.

A total of 4,534 patients were tested: 3,335 (74%) were pregnant women. Among 1,541 patients with one or more Zika virus–associated symptoms, 182 (12%) had confirmed Zika virus infection. Only seven (0.3%) of 2,425 asymptomatic pregnant women who were tested had confirmed Zika virus infection. Of those patients, five resided in areas with active Zika virus transmission at some time during their pregnancy and two were short-term travelers, according to Dr. Sarah Reagan-Steiner of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases and her coauthors.

“It is reassuring that the proportion of asymptomatic pregnant women with confirmed Zika virus infection in this report was low” and not unexpected in the current U.S. setting, where most exposure to the Zika virus is travel-associated, the investigators wrote.

No conflicts of interested were reported by the authors. Read the full report in MMWR (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Apr 15. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6515e1).

On Twitter @richpizzi

Although the likelihood of Zika virus infection is low among asymptomatic patients, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends offering Zika virus testing to asymptomatic pregnant women with potential exposure.

The recommendation is based on Zika virus testing performed in U.S. states and the District of Columbia from Jan. 3 to March 5, 2016. The analysis included specimens that were received for testing at the CDC Arboviral Diseases Branch and confirmed Zika virus infection was defined as detection of Zika virus RNA by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, or anti-Zika immunoglobulin M antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with neutralizing antibody titers against Zika virus, at levels greater than or equal to fourfold higher than those against dengue virus.

A total of 4,534 patients were tested: 3,335 (74%) were pregnant women. Among 1,541 patients with one or more Zika virus–associated symptoms, 182 (12%) had confirmed Zika virus infection. Only seven (0.3%) of 2,425 asymptomatic pregnant women who were tested had confirmed Zika virus infection. Of those patients, five resided in areas with active Zika virus transmission at some time during their pregnancy and two were short-term travelers, according to Dr. Sarah Reagan-Steiner of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases and her coauthors.

“It is reassuring that the proportion of asymptomatic pregnant women with confirmed Zika virus infection in this report was low” and not unexpected in the current U.S. setting, where most exposure to the Zika virus is travel-associated, the investigators wrote.

No conflicts of interested were reported by the authors. Read the full report in MMWR (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Apr 15. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6515e1).

On Twitter @richpizzi

Although the likelihood of Zika virus infection is low among asymptomatic patients, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends offering Zika virus testing to asymptomatic pregnant women with potential exposure.

The recommendation is based on Zika virus testing performed in U.S. states and the District of Columbia from Jan. 3 to March 5, 2016. The analysis included specimens that were received for testing at the CDC Arboviral Diseases Branch and confirmed Zika virus infection was defined as detection of Zika virus RNA by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, or anti-Zika immunoglobulin M antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with neutralizing antibody titers against Zika virus, at levels greater than or equal to fourfold higher than those against dengue virus.

A total of 4,534 patients were tested: 3,335 (74%) were pregnant women. Among 1,541 patients with one or more Zika virus–associated symptoms, 182 (12%) had confirmed Zika virus infection. Only seven (0.3%) of 2,425 asymptomatic pregnant women who were tested had confirmed Zika virus infection. Of those patients, five resided in areas with active Zika virus transmission at some time during their pregnancy and two were short-term travelers, according to Dr. Sarah Reagan-Steiner of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases and her coauthors.

“It is reassuring that the proportion of asymptomatic pregnant women with confirmed Zika virus infection in this report was low” and not unexpected in the current U.S. setting, where most exposure to the Zika virus is travel-associated, the investigators wrote.

No conflicts of interested were reported by the authors. Read the full report in MMWR (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Apr 15. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6515e1).

On Twitter @richpizzi

FROM MMWR

Rapid diagnostic tests used to detect Ebola

A new rapid diagnostic test for Ebola (RDT-Ebola) has been used to diagnose patients in Forécariah, Guinea. The National Ebola Coordination Cell implemented the test to enhance efforts to detect new Ebola cases and to ensure that such cases are not clinically misdiagnosed as malaria.

Jennifer Y. Huang and her associates found that among 13 sentinel sites during Oct. 1–Nov. 23, 2015, 1,544 (73%) of 2,115 consultations were for evaluation of febrile illness. Of those 1,544 consultations, 1,553 RDT-Malaria tests were reported to have been conducted and 1,000 RDT-Ebola tests were conducted. A total of 1,112 patients tested positive for malaria by RDT (the range of percentage of positive malaria tests among 13 sentinel sites was 52.3%-85.7%); none tested positive for Ebola by RDT-Ebola.

The ratio of RDT-Ebola to RDT-Malaria tests used was 0.64 overall and ranged from 0.27 to 1.00, according to the researchers.

Reported barriers to RDT-Ebola use – inadequate stock of RDT-Ebola kits, lack of understanding of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention RDT-Ebola testing protocol, and patient refusal of RDT-Ebola testing – may have contributed to the differences in the numbers of malaria and Ebola tests conducted, the researchers wrote.

“Ongoing data collection from the sentinel sites can help to monitor the success of RDT-Ebola implementation, inform supply chain management, and identify and address barriers to RDT-Ebola use. RDT-Ebola implementation at the sentinel sites can also aid in screening for undetected Ebola cases to prevent establishment of new transmission chains,” the researchers concluded.

Find the study in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6512a4).

A new rapid diagnostic test for Ebola (RDT-Ebola) has been used to diagnose patients in Forécariah, Guinea. The National Ebola Coordination Cell implemented the test to enhance efforts to detect new Ebola cases and to ensure that such cases are not clinically misdiagnosed as malaria.

Jennifer Y. Huang and her associates found that among 13 sentinel sites during Oct. 1–Nov. 23, 2015, 1,544 (73%) of 2,115 consultations were for evaluation of febrile illness. Of those 1,544 consultations, 1,553 RDT-Malaria tests were reported to have been conducted and 1,000 RDT-Ebola tests were conducted. A total of 1,112 patients tested positive for malaria by RDT (the range of percentage of positive malaria tests among 13 sentinel sites was 52.3%-85.7%); none tested positive for Ebola by RDT-Ebola.

The ratio of RDT-Ebola to RDT-Malaria tests used was 0.64 overall and ranged from 0.27 to 1.00, according to the researchers.

Reported barriers to RDT-Ebola use – inadequate stock of RDT-Ebola kits, lack of understanding of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention RDT-Ebola testing protocol, and patient refusal of RDT-Ebola testing – may have contributed to the differences in the numbers of malaria and Ebola tests conducted, the researchers wrote.

“Ongoing data collection from the sentinel sites can help to monitor the success of RDT-Ebola implementation, inform supply chain management, and identify and address barriers to RDT-Ebola use. RDT-Ebola implementation at the sentinel sites can also aid in screening for undetected Ebola cases to prevent establishment of new transmission chains,” the researchers concluded.

Find the study in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6512a4).

A new rapid diagnostic test for Ebola (RDT-Ebola) has been used to diagnose patients in Forécariah, Guinea. The National Ebola Coordination Cell implemented the test to enhance efforts to detect new Ebola cases and to ensure that such cases are not clinically misdiagnosed as malaria.

Jennifer Y. Huang and her associates found that among 13 sentinel sites during Oct. 1–Nov. 23, 2015, 1,544 (73%) of 2,115 consultations were for evaluation of febrile illness. Of those 1,544 consultations, 1,553 RDT-Malaria tests were reported to have been conducted and 1,000 RDT-Ebola tests were conducted. A total of 1,112 patients tested positive for malaria by RDT (the range of percentage of positive malaria tests among 13 sentinel sites was 52.3%-85.7%); none tested positive for Ebola by RDT-Ebola.

The ratio of RDT-Ebola to RDT-Malaria tests used was 0.64 overall and ranged from 0.27 to 1.00, according to the researchers.

Reported barriers to RDT-Ebola use – inadequate stock of RDT-Ebola kits, lack of understanding of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention RDT-Ebola testing protocol, and patient refusal of RDT-Ebola testing – may have contributed to the differences in the numbers of malaria and Ebola tests conducted, the researchers wrote.

“Ongoing data collection from the sentinel sites can help to monitor the success of RDT-Ebola implementation, inform supply chain management, and identify and address barriers to RDT-Ebola use. RDT-Ebola implementation at the sentinel sites can also aid in screening for undetected Ebola cases to prevent establishment of new transmission chains,” the researchers concluded.

Find the study in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6512a4).

FROM MMWR

CDC confirms Zika virus as a cause of microcephaly

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly in babies born to infected mothers, following a systematic review of the latest research on Zika virus.

The CDC released findings from that review in a peer-reviewed special report published online April 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338). The report, CDC officials said, incorporated evidence from as recently as the past week.

In a press conference in April, CDC director Tom Frieden said there was “no longer any doubt” that Zika virus causes microcephaly. Dr. Frieden’s statements reflect what appears to be a growing scientific consensus. On March 31, the World Health Organization reported that there was a “strong” consensus that Zika virus can cause microcephaly, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and other neurological disorders. New microcephaly cases in Colombia – with 32 reported by the end of March – are among the findings cited by both the WHO and the CDC.

Dr. Frieden stressed that no single piece of evidence was seen to provide conclusive proof of causation, but that the CDC scientists’ conclusions were based on “a thorough review of the best available evidence” subjected to established criteria.

For its review published in the New England Journal of Medicine, CDC scientists led by Dr. Sonja Rasmussen subjected available evidence to two separate criteria to determine the relationship of Zika virus to the spikes in microcephaly cases seen in countries where Zika is spreading. Shepard’s criteria were used to prove teratogenicity, and the Bradford Hill criteria were used to show evidence of causation.

The CDC has not made any changes to its guidance on Zika virus prevention, which includes advising pregnant women to avoid travel to regions where Zika transmission is occurring, take steps to prevent infection if they live in areas where Zika virus is present, and use condoms to prevent sexual transmission of Zika from a partner. On April 13, the CDC added St. Lucia to its growing list of countries to be avoided by pregnant women.

The full spectrum of defects caused by congenital Zika infection is still poorly understood. Additional studies are underway at CDC, Dr. Frieden said, to better understand the severe phenotype of microcephaly seen in babies born to Zika-infected mothers and “to determine whether children who have microcephaly born to mothers infected by the Zika virus is the tip of the iceberg of what we could see in damaging effects on the brain.”

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly in babies born to infected mothers, following a systematic review of the latest research on Zika virus.

The CDC released findings from that review in a peer-reviewed special report published online April 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338). The report, CDC officials said, incorporated evidence from as recently as the past week.

In a press conference in April, CDC director Tom Frieden said there was “no longer any doubt” that Zika virus causes microcephaly. Dr. Frieden’s statements reflect what appears to be a growing scientific consensus. On March 31, the World Health Organization reported that there was a “strong” consensus that Zika virus can cause microcephaly, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and other neurological disorders. New microcephaly cases in Colombia – with 32 reported by the end of March – are among the findings cited by both the WHO and the CDC.

Dr. Frieden stressed that no single piece of evidence was seen to provide conclusive proof of causation, but that the CDC scientists’ conclusions were based on “a thorough review of the best available evidence” subjected to established criteria.

For its review published in the New England Journal of Medicine, CDC scientists led by Dr. Sonja Rasmussen subjected available evidence to two separate criteria to determine the relationship of Zika virus to the spikes in microcephaly cases seen in countries where Zika is spreading. Shepard’s criteria were used to prove teratogenicity, and the Bradford Hill criteria were used to show evidence of causation.

The CDC has not made any changes to its guidance on Zika virus prevention, which includes advising pregnant women to avoid travel to regions where Zika transmission is occurring, take steps to prevent infection if they live in areas where Zika virus is present, and use condoms to prevent sexual transmission of Zika from a partner. On April 13, the CDC added St. Lucia to its growing list of countries to be avoided by pregnant women.

The full spectrum of defects caused by congenital Zika infection is still poorly understood. Additional studies are underway at CDC, Dr. Frieden said, to better understand the severe phenotype of microcephaly seen in babies born to Zika-infected mothers and “to determine whether children who have microcephaly born to mothers infected by the Zika virus is the tip of the iceberg of what we could see in damaging effects on the brain.”

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have determined that Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly in babies born to infected mothers, following a systematic review of the latest research on Zika virus.

The CDC released findings from that review in a peer-reviewed special report published online April 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338). The report, CDC officials said, incorporated evidence from as recently as the past week.

In a press conference in April, CDC director Tom Frieden said there was “no longer any doubt” that Zika virus causes microcephaly. Dr. Frieden’s statements reflect what appears to be a growing scientific consensus. On March 31, the World Health Organization reported that there was a “strong” consensus that Zika virus can cause microcephaly, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and other neurological disorders. New microcephaly cases in Colombia – with 32 reported by the end of March – are among the findings cited by both the WHO and the CDC.

Dr. Frieden stressed that no single piece of evidence was seen to provide conclusive proof of causation, but that the CDC scientists’ conclusions were based on “a thorough review of the best available evidence” subjected to established criteria.

For its review published in the New England Journal of Medicine, CDC scientists led by Dr. Sonja Rasmussen subjected available evidence to two separate criteria to determine the relationship of Zika virus to the spikes in microcephaly cases seen in countries where Zika is spreading. Shepard’s criteria were used to prove teratogenicity, and the Bradford Hill criteria were used to show evidence of causation.

The CDC has not made any changes to its guidance on Zika virus prevention, which includes advising pregnant women to avoid travel to regions where Zika transmission is occurring, take steps to prevent infection if they live in areas where Zika virus is present, and use condoms to prevent sexual transmission of Zika from a partner. On April 13, the CDC added St. Lucia to its growing list of countries to be avoided by pregnant women.

The full spectrum of defects caused by congenital Zika infection is still poorly understood. Additional studies are underway at CDC, Dr. Frieden said, to better understand the severe phenotype of microcephaly seen in babies born to Zika-infected mothers and “to determine whether children who have microcephaly born to mothers infected by the Zika virus is the tip of the iceberg of what we could see in damaging effects on the brain.”

FROM A CDC PRESS CONFERENCE

Severe sepsis and septic shock syndrome linked to chikungunya

Severe sepsis and septic shock syndrome may be rare complications of chikungunya virus infection, according to a recent study in Guadeloupe.

Dr. Bruno Hoen, of the department of infectious diseases, dermatology, and internal medicine at the University Medical Center of Guadeloupe, and his associates studied 110 nonpregnant adults hospitalized at the University Hospital of Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, with chikungunya (CHIKV) after a November 2013 outbreak in Guadeloupe. Of all patients who had a positive CHIKV reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, 34 had a common form, 34 had an atypical form, and 42 had a severe form. Among the 42 patients with severe forms, 25 patients had illness consistent with the case definition for severe sepsis and had no other identified cause for this syndrome, and 12 died.

The 25 patients identified as having severe sepsis had significantly higher occurrences of cardiac, respiratory, and renal manifestations upon admission to hospital. They also had significantly higher leukocyte counts and levels of serum lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, and creatinine – all clinical and laboratory indicators of sepsis – than patients without severe sepsis or septic shock. In addition, the mortality rate for the patients with severe sepsis was significantly higher than that in patients without severe sepsis or septic shock (48% vs. 3%; P less than .001).

As none of the 25 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in the early stages of CHIKV had another organism that could be identified as a potential cause of sepsis, the researchers concluded that this finding strongly suggests that CHIKV can, in rare cases, cause severe sepsis and septic shock syndromes, an observation that had not been reported until very recently.

Dr. Hoen and his colleagues said additional studies are needed to identify any background characteristics that might be associated with the onset of severe sepsis or septic shock. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study in Emerging Infectious Diseases (2016 May. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151449).

Severe sepsis and septic shock syndrome may be rare complications of chikungunya virus infection, according to a recent study in Guadeloupe.

Dr. Bruno Hoen, of the department of infectious diseases, dermatology, and internal medicine at the University Medical Center of Guadeloupe, and his associates studied 110 nonpregnant adults hospitalized at the University Hospital of Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, with chikungunya (CHIKV) after a November 2013 outbreak in Guadeloupe. Of all patients who had a positive CHIKV reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, 34 had a common form, 34 had an atypical form, and 42 had a severe form. Among the 42 patients with severe forms, 25 patients had illness consistent with the case definition for severe sepsis and had no other identified cause for this syndrome, and 12 died.

The 25 patients identified as having severe sepsis had significantly higher occurrences of cardiac, respiratory, and renal manifestations upon admission to hospital. They also had significantly higher leukocyte counts and levels of serum lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, and creatinine – all clinical and laboratory indicators of sepsis – than patients without severe sepsis or septic shock. In addition, the mortality rate for the patients with severe sepsis was significantly higher than that in patients without severe sepsis or septic shock (48% vs. 3%; P less than .001).

As none of the 25 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in the early stages of CHIKV had another organism that could be identified as a potential cause of sepsis, the researchers concluded that this finding strongly suggests that CHIKV can, in rare cases, cause severe sepsis and septic shock syndromes, an observation that had not been reported until very recently.

Dr. Hoen and his colleagues said additional studies are needed to identify any background characteristics that might be associated with the onset of severe sepsis or septic shock. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study in Emerging Infectious Diseases (2016 May. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151449).

Severe sepsis and septic shock syndrome may be rare complications of chikungunya virus infection, according to a recent study in Guadeloupe.

Dr. Bruno Hoen, of the department of infectious diseases, dermatology, and internal medicine at the University Medical Center of Guadeloupe, and his associates studied 110 nonpregnant adults hospitalized at the University Hospital of Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, with chikungunya (CHIKV) after a November 2013 outbreak in Guadeloupe. Of all patients who had a positive CHIKV reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test result, 34 had a common form, 34 had an atypical form, and 42 had a severe form. Among the 42 patients with severe forms, 25 patients had illness consistent with the case definition for severe sepsis and had no other identified cause for this syndrome, and 12 died.

The 25 patients identified as having severe sepsis had significantly higher occurrences of cardiac, respiratory, and renal manifestations upon admission to hospital. They also had significantly higher leukocyte counts and levels of serum lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, and creatinine – all clinical and laboratory indicators of sepsis – than patients without severe sepsis or septic shock. In addition, the mortality rate for the patients with severe sepsis was significantly higher than that in patients without severe sepsis or septic shock (48% vs. 3%; P less than .001).

As none of the 25 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in the early stages of CHIKV had another organism that could be identified as a potential cause of sepsis, the researchers concluded that this finding strongly suggests that CHIKV can, in rare cases, cause severe sepsis and septic shock syndromes, an observation that had not been reported until very recently.

Dr. Hoen and his colleagues said additional studies are needed to identify any background characteristics that might be associated with the onset of severe sepsis or septic shock. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study in Emerging Infectious Diseases (2016 May. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151449).

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Zika caused rash, pruritus more than high fever

Zika virus infection in adults often causes pruritic maculopapular rash, but rarely leads to clinically significant fever, according to two cohort studies in Rio de Janeiro.

The findings raise questions about case definitions of Zika virus disease (ZVD).

“In our opinion, pruritus, the second most common clinical sign presented by the confirmed cases, should be added to the Pan American Health Organization case definition [for Zika virus disease], while fever could be given less emphasis,” Dr. Patricia Brasil of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro and her associates wrote online April 12 in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Watching for a combination of itching and rash also could help distinguish Zika virus disease from infections of Chikungunya and Dengue, co-circulating arboviruses in Brazil that tend to cause nonpruritic rash, the investigators noted. Distinguishing these infections is crucial because Dengue, in particular, can be devastating without appropriate treatment (doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004636).

Brazil confirmed Zika virus disease in the northeastern state of Bahia in May 2015. Cases in Rio de Janeiro soon followed, triggering worries because of its dense population and status as host of the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games. To better characterize Zika virus disease in Rio de Janeiro, Dr. Brasil and her associates studied 364 cases of acute rash, with or without fever, among adults with clinical onset during the first half of 2015. Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction detected Zika viral RNA in blood samples from 119 (45%) of 262 patients tested.

The first 4 days of confirmed ZVD were marked by rash (97%), itching (79%), prostration (73%), headache (66%), arthralgias (63%), and myalgia (61%). Just 36% of patients were febrile, and fevers usually were short-lived and low-grade, in contrast to other arboviral infections. Partial sequencing of the Zika virus gene from 10 randomly selected positive samples showed that it resembled Asian strains of Zika virus, supporting the hypothesis that Pacific Islanders brought Zika to Rio de Janeiro during a canoe championship in 2014, the researchers added.

The researchers also determined that Zika virus was circulating in Rio de Janeiro as early as January 2015 – “at least five months before its detection was announced by the health authorities, which must be taken into consideration for future design and implementation of effective syndromic surveillance systems,” they wrote. Surprisingly, an assay for Dengue was negative in all 250 patients tested, which might indicate “explosive transmission dynamics of Zika virus disease,” the investigators added.

A retrospective cohort study of confirmed Zika virus cases in Rio de Janeiro also reported a much higher prevalence of rash compared with fever (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.3201/eid2207.160375).

This was a retrospective convenience sample of 57 patients, including 98% with rash, 56% with pruritus, and 67% with measured or self-reported fever. Most fevers were low-grade, and the median recorded temperature was 30.0 degrees Celsius (within normal limits). Other common presentations included headache (67%), arthralgias (58%), myalgias (49%), and joint swelling (23%), according to Dr. Jose Cerbino-Neto of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro and his associates. Their findings support emphasizing rash, fever, or both as “primary characteristics” of ZVD, they added. Currently, the interim case definition from the World Health Organization defines a suspected Zika virus disease case as rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of three other symptoms – arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis.

The study by Dr. Brasil and her associates was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico, the Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa no Estado do Rio de Janeiro, and the European Commission. Dr. Brasil and her coinvestigators had no disclosures. Dr. Cerbino-Neto reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Zika virus infection in adults often causes pruritic maculopapular rash, but rarely leads to clinically significant fever, according to two cohort studies in Rio de Janeiro.

The findings raise questions about case definitions of Zika virus disease (ZVD).

“In our opinion, pruritus, the second most common clinical sign presented by the confirmed cases, should be added to the Pan American Health Organization case definition [for Zika virus disease], while fever could be given less emphasis,” Dr. Patricia Brasil of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro and her associates wrote online April 12 in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Watching for a combination of itching and rash also could help distinguish Zika virus disease from infections of Chikungunya and Dengue, co-circulating arboviruses in Brazil that tend to cause nonpruritic rash, the investigators noted. Distinguishing these infections is crucial because Dengue, in particular, can be devastating without appropriate treatment (doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004636).

Brazil confirmed Zika virus disease in the northeastern state of Bahia in May 2015. Cases in Rio de Janeiro soon followed, triggering worries because of its dense population and status as host of the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games. To better characterize Zika virus disease in Rio de Janeiro, Dr. Brasil and her associates studied 364 cases of acute rash, with or without fever, among adults with clinical onset during the first half of 2015. Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction detected Zika viral RNA in blood samples from 119 (45%) of 262 patients tested.

The first 4 days of confirmed ZVD were marked by rash (97%), itching (79%), prostration (73%), headache (66%), arthralgias (63%), and myalgia (61%). Just 36% of patients were febrile, and fevers usually were short-lived and low-grade, in contrast to other arboviral infections. Partial sequencing of the Zika virus gene from 10 randomly selected positive samples showed that it resembled Asian strains of Zika virus, supporting the hypothesis that Pacific Islanders brought Zika to Rio de Janeiro during a canoe championship in 2014, the researchers added.

The researchers also determined that Zika virus was circulating in Rio de Janeiro as early as January 2015 – “at least five months before its detection was announced by the health authorities, which must be taken into consideration for future design and implementation of effective syndromic surveillance systems,” they wrote. Surprisingly, an assay for Dengue was negative in all 250 patients tested, which might indicate “explosive transmission dynamics of Zika virus disease,” the investigators added.

A retrospective cohort study of confirmed Zika virus cases in Rio de Janeiro also reported a much higher prevalence of rash compared with fever (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.3201/eid2207.160375).

This was a retrospective convenience sample of 57 patients, including 98% with rash, 56% with pruritus, and 67% with measured or self-reported fever. Most fevers were low-grade, and the median recorded temperature was 30.0 degrees Celsius (within normal limits). Other common presentations included headache (67%), arthralgias (58%), myalgias (49%), and joint swelling (23%), according to Dr. Jose Cerbino-Neto of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro and his associates. Their findings support emphasizing rash, fever, or both as “primary characteristics” of ZVD, they added. Currently, the interim case definition from the World Health Organization defines a suspected Zika virus disease case as rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of three other symptoms – arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis.

The study by Dr. Brasil and her associates was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico, the Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa no Estado do Rio de Janeiro, and the European Commission. Dr. Brasil and her coinvestigators had no disclosures. Dr. Cerbino-Neto reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Zika virus infection in adults often causes pruritic maculopapular rash, but rarely leads to clinically significant fever, according to two cohort studies in Rio de Janeiro.

The findings raise questions about case definitions of Zika virus disease (ZVD).

“In our opinion, pruritus, the second most common clinical sign presented by the confirmed cases, should be added to the Pan American Health Organization case definition [for Zika virus disease], while fever could be given less emphasis,” Dr. Patricia Brasil of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro and her associates wrote online April 12 in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Watching for a combination of itching and rash also could help distinguish Zika virus disease from infections of Chikungunya and Dengue, co-circulating arboviruses in Brazil that tend to cause nonpruritic rash, the investigators noted. Distinguishing these infections is crucial because Dengue, in particular, can be devastating without appropriate treatment (doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004636).

Brazil confirmed Zika virus disease in the northeastern state of Bahia in May 2015. Cases in Rio de Janeiro soon followed, triggering worries because of its dense population and status as host of the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games. To better characterize Zika virus disease in Rio de Janeiro, Dr. Brasil and her associates studied 364 cases of acute rash, with or without fever, among adults with clinical onset during the first half of 2015. Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction detected Zika viral RNA in blood samples from 119 (45%) of 262 patients tested.

The first 4 days of confirmed ZVD were marked by rash (97%), itching (79%), prostration (73%), headache (66%), arthralgias (63%), and myalgia (61%). Just 36% of patients were febrile, and fevers usually were short-lived and low-grade, in contrast to other arboviral infections. Partial sequencing of the Zika virus gene from 10 randomly selected positive samples showed that it resembled Asian strains of Zika virus, supporting the hypothesis that Pacific Islanders brought Zika to Rio de Janeiro during a canoe championship in 2014, the researchers added.

The researchers also determined that Zika virus was circulating in Rio de Janeiro as early as January 2015 – “at least five months before its detection was announced by the health authorities, which must be taken into consideration for future design and implementation of effective syndromic surveillance systems,” they wrote. Surprisingly, an assay for Dengue was negative in all 250 patients tested, which might indicate “explosive transmission dynamics of Zika virus disease,” the investigators added.

A retrospective cohort study of confirmed Zika virus cases in Rio de Janeiro also reported a much higher prevalence of rash compared with fever (Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jul. doi: 10.3201/eid2207.160375).

This was a retrospective convenience sample of 57 patients, including 98% with rash, 56% with pruritus, and 67% with measured or self-reported fever. Most fevers were low-grade, and the median recorded temperature was 30.0 degrees Celsius (within normal limits). Other common presentations included headache (67%), arthralgias (58%), myalgias (49%), and joint swelling (23%), according to Dr. Jose Cerbino-Neto of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro and his associates. Their findings support emphasizing rash, fever, or both as “primary characteristics” of ZVD, they added. Currently, the interim case definition from the World Health Organization defines a suspected Zika virus disease case as rash, fever, or both, plus at least one of three other symptoms – arthralgia, arthritis, or conjunctivitis.

The study by Dr. Brasil and her associates was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico, the Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa no Estado do Rio de Janeiro, and the European Commission. Dr. Brasil and her coinvestigators had no disclosures. Dr. Cerbino-Neto reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

FROM PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES AND EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Rash was much more common than fever in two separate studies of Zika virus cases among adults in Rio de Janeiro.

Major finding: In the first study, 97% of laboratory-confirmed cases had rash, while only 36% had fever. In the second study, 98% of patients had rash and 67% had fever. In contrast to other arboviral infections, patients often described the rashes as pruritic.

Data source: A prospective study of 119 PCR-confirmed cases and a retrospective study of 57 confirmed cases, all in Rio de Janeiro.

Disclosures: The study by Dr. Brasil and her associates was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico, the Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa no Estado do Rio de Janeiro, and the European Commission. Dr. Brasil and her coinvestigators had no disclosures. Dr. Cerbino-Neto reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Colombia reports first Zika deaths, all in medically compromised patients

AMSTERDAM – Five people with confirmed Zika virus infections have died in Colombia, and all had medical comorbidities, including leukemia, diabetes, sickle cell anemia, and hypertension.

All of the deaths occurred last October in northern and central Colombia, Dr. Alfonso Rodriguez-Morales said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Four of the cases were simultaneously published April 7 in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (2016 Apr 7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30006-8). The fifth case occurred in northern Colombia, and was reported in Emerging Infectious Diseases (2016 May. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151934).

Reports of confirmed Zika-related deaths are rare. Brazil, the only other country to disclose them, has now reported three, said Dr. Rodriguez-Morales of the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira, Colombia.

“Before the current outbreak in Latin America, Zika virus was not linked to deaths,” he noted. But the eight confirmed Zika-related deaths in South America “call attention to the need for evidence-based guidelines for clinical management of Zika, as well as the possible occurrence of atypical and severe cases, including possibly congenitally related microcephaly.”

Because they all occurred in medically compromised patients, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales also urged clinicians to cast a wary eye on such patients who present with arbovirus-type symptoms, including fever and rash.

From September 2015 to March 2016, Colombia had 58,838 reported cases of Zika. Of those, only 2,361 were lab confirmed. The rest were either diagnosed clinically or were suspected cases, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales said. Although Colombia has a much smaller population than Brazil (49 million vs. 210 million), its Zika case rate is much higher, 120 cases per 100,000 people vs. 34 cases per 100,000 people.

The group of four deaths occurred in central Colombia, and included a 2-year-old girl, a 30-year-old woman, a 61-year-old man, and a 72-year-old woman. All presented with 2-6 days of fever. All were initially suspected to have dengue fever or chikungunya. None tested positive for dengue, but the man was coinfected with chikungunya.

All patients presented with anemia. All but the older man also had severe thrombocytopenia.

The toddler presented with hepatomegaly, mucosal hemorrhage, progressive respiratory collapse, progressive thrombocytopenia, and intravascular coagulation. She died 5 days after symptom onset and was found to have had unrecognized lymphoblastic leukemia.

The 30-year-old woman presented with a severe rash on both arms. She also exhibited coagulation dysfunction, including severe thrombocytopenia and leukopenia that progressed to intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. She died 12 days after symptom onset. She was determined to have had unrecognized acute myeloid leukemia.

The elderly man had a history of medically controlled hypertension. He experienced mucosal hemorrhage and respiratory distress. He died 7 days after symptom onset. On autopsy, his liver showed necrotic areas, and his spleen indicated a systemic inflammatory response.

The elderly woman had a history of insulin-controlled type 2 diabetes. Her symptoms included gastrointestinal distress, thrombocytopenia, and acute respiratory failure. She died 48 hours after symptom onset; her brain showed edema and ischemic lesions.

The 15-year-old girl in northern Colombia had a 5-year history of sickle cell disease, which, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales pointed out, is a risk factor for arbovirus diseases. However, the patient had never been hospitalized for a vasoocclusive crisis. She presented with a high fever; joint, muscle, and abdominal pain; and jaundice. She was assumed to have dengue virus. Within another day, she had progressed into respiratory failure and was on a ventilator. She died less than 2 days later.

Her autopsy showed hepatic necrosis and severe decrease of splenic lymphoid tissue with splenic sequestration. Systemic inflammation probably triggered a fatal vasoocclusive crisis and splenic sequestration.

Dr. Rodriguez-Morales had no financial disclosures.

AMSTERDAM – Five people with confirmed Zika virus infections have died in Colombia, and all had medical comorbidities, including leukemia, diabetes, sickle cell anemia, and hypertension.

All of the deaths occurred last October in northern and central Colombia, Dr. Alfonso Rodriguez-Morales said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Four of the cases were simultaneously published April 7 in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (2016 Apr 7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30006-8). The fifth case occurred in northern Colombia, and was reported in Emerging Infectious Diseases (2016 May. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151934).

Reports of confirmed Zika-related deaths are rare. Brazil, the only other country to disclose them, has now reported three, said Dr. Rodriguez-Morales of the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira, Colombia.

“Before the current outbreak in Latin America, Zika virus was not linked to deaths,” he noted. But the eight confirmed Zika-related deaths in South America “call attention to the need for evidence-based guidelines for clinical management of Zika, as well as the possible occurrence of atypical and severe cases, including possibly congenitally related microcephaly.”

Because they all occurred in medically compromised patients, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales also urged clinicians to cast a wary eye on such patients who present with arbovirus-type symptoms, including fever and rash.

From September 2015 to March 2016, Colombia had 58,838 reported cases of Zika. Of those, only 2,361 were lab confirmed. The rest were either diagnosed clinically or were suspected cases, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales said. Although Colombia has a much smaller population than Brazil (49 million vs. 210 million), its Zika case rate is much higher, 120 cases per 100,000 people vs. 34 cases per 100,000 people.

The group of four deaths occurred in central Colombia, and included a 2-year-old girl, a 30-year-old woman, a 61-year-old man, and a 72-year-old woman. All presented with 2-6 days of fever. All were initially suspected to have dengue fever or chikungunya. None tested positive for dengue, but the man was coinfected with chikungunya.

All patients presented with anemia. All but the older man also had severe thrombocytopenia.

The toddler presented with hepatomegaly, mucosal hemorrhage, progressive respiratory collapse, progressive thrombocytopenia, and intravascular coagulation. She died 5 days after symptom onset and was found to have had unrecognized lymphoblastic leukemia.

The 30-year-old woman presented with a severe rash on both arms. She also exhibited coagulation dysfunction, including severe thrombocytopenia and leukopenia that progressed to intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. She died 12 days after symptom onset. She was determined to have had unrecognized acute myeloid leukemia.

The elderly man had a history of medically controlled hypertension. He experienced mucosal hemorrhage and respiratory distress. He died 7 days after symptom onset. On autopsy, his liver showed necrotic areas, and his spleen indicated a systemic inflammatory response.

The elderly woman had a history of insulin-controlled type 2 diabetes. Her symptoms included gastrointestinal distress, thrombocytopenia, and acute respiratory failure. She died 48 hours after symptom onset; her brain showed edema and ischemic lesions.

The 15-year-old girl in northern Colombia had a 5-year history of sickle cell disease, which, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales pointed out, is a risk factor for arbovirus diseases. However, the patient had never been hospitalized for a vasoocclusive crisis. She presented with a high fever; joint, muscle, and abdominal pain; and jaundice. She was assumed to have dengue virus. Within another day, she had progressed into respiratory failure and was on a ventilator. She died less than 2 days later.

Her autopsy showed hepatic necrosis and severe decrease of splenic lymphoid tissue with splenic sequestration. Systemic inflammation probably triggered a fatal vasoocclusive crisis and splenic sequestration.

Dr. Rodriguez-Morales had no financial disclosures.

AMSTERDAM – Five people with confirmed Zika virus infections have died in Colombia, and all had medical comorbidities, including leukemia, diabetes, sickle cell anemia, and hypertension.

All of the deaths occurred last October in northern and central Colombia, Dr. Alfonso Rodriguez-Morales said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Four of the cases were simultaneously published April 7 in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (2016 Apr 7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]30006-8). The fifth case occurred in northern Colombia, and was reported in Emerging Infectious Diseases (2016 May. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151934).

Reports of confirmed Zika-related deaths are rare. Brazil, the only other country to disclose them, has now reported three, said Dr. Rodriguez-Morales of the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira, Colombia.

“Before the current outbreak in Latin America, Zika virus was not linked to deaths,” he noted. But the eight confirmed Zika-related deaths in South America “call attention to the need for evidence-based guidelines for clinical management of Zika, as well as the possible occurrence of atypical and severe cases, including possibly congenitally related microcephaly.”

Because they all occurred in medically compromised patients, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales also urged clinicians to cast a wary eye on such patients who present with arbovirus-type symptoms, including fever and rash.

From September 2015 to March 2016, Colombia had 58,838 reported cases of Zika. Of those, only 2,361 were lab confirmed. The rest were either diagnosed clinically or were suspected cases, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales said. Although Colombia has a much smaller population than Brazil (49 million vs. 210 million), its Zika case rate is much higher, 120 cases per 100,000 people vs. 34 cases per 100,000 people.

The group of four deaths occurred in central Colombia, and included a 2-year-old girl, a 30-year-old woman, a 61-year-old man, and a 72-year-old woman. All presented with 2-6 days of fever. All were initially suspected to have dengue fever or chikungunya. None tested positive for dengue, but the man was coinfected with chikungunya.

All patients presented with anemia. All but the older man also had severe thrombocytopenia.

The toddler presented with hepatomegaly, mucosal hemorrhage, progressive respiratory collapse, progressive thrombocytopenia, and intravascular coagulation. She died 5 days after symptom onset and was found to have had unrecognized lymphoblastic leukemia.

The 30-year-old woman presented with a severe rash on both arms. She also exhibited coagulation dysfunction, including severe thrombocytopenia and leukopenia that progressed to intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. She died 12 days after symptom onset. She was determined to have had unrecognized acute myeloid leukemia.

The elderly man had a history of medically controlled hypertension. He experienced mucosal hemorrhage and respiratory distress. He died 7 days after symptom onset. On autopsy, his liver showed necrotic areas, and his spleen indicated a systemic inflammatory response.

The elderly woman had a history of insulin-controlled type 2 diabetes. Her symptoms included gastrointestinal distress, thrombocytopenia, and acute respiratory failure. She died 48 hours after symptom onset; her brain showed edema and ischemic lesions.

The 15-year-old girl in northern Colombia had a 5-year history of sickle cell disease, which, Dr. Rodriguez-Morales pointed out, is a risk factor for arbovirus diseases. However, the patient had never been hospitalized for a vasoocclusive crisis. She presented with a high fever; joint, muscle, and abdominal pain; and jaundice. She was assumed to have dengue virus. Within another day, she had progressed into respiratory failure and was on a ventilator. She died less than 2 days later.

Her autopsy showed hepatic necrosis and severe decrease of splenic lymphoid tissue with splenic sequestration. Systemic inflammation probably triggered a fatal vasoocclusive crisis and splenic sequestration.

Dr. Rodriguez-Morales had no financial disclosures.

AT ECCMID 2016

Intracranial calcification, hypomyelination seen with Zika virus congenital microcephaly

A CT imaging study in 23 infants with Zika virus–linked congenital microcephaly has revealed severe brain anomalies, in particular intracranial calcifications mainly in the frontal and parietal lobes that were mostly punctate, often with a bandlike distribution.

Head CT images were taken between 3 days and 5 months after birth (mean age, 36 days) revealing ventriculomegaly in all infants, which was severe in more than half, according to a letter published online April 6 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers also observed global hypogyration in the cerebral cortex in all the infants (severe in 78%) and cerebellar hypoplasia in 74%, as well as an abnormally low density of white matter in all cases (N Engl J Med. 2016 April 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1603617).

“The global presence of cortical hypogyration and white-matter hypomyelination or dysmyelination in all the infants, and cerebellar hypoplasia in the majority of them, suggest that ZIKV [Zika virus] is associated with a disruption in brain development rather than a destruction of brain,” wrote Dr. Adriano N. Hazin of the Instituto di Medicina Integral Professor Fernando Figueira, Recife, Brazil, and coauthors who reported the findings for the Microcephaly Epidemic Research Group.

Two authors declared grants from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

A CT imaging study in 23 infants with Zika virus–linked congenital microcephaly has revealed severe brain anomalies, in particular intracranial calcifications mainly in the frontal and parietal lobes that were mostly punctate, often with a bandlike distribution.

Head CT images were taken between 3 days and 5 months after birth (mean age, 36 days) revealing ventriculomegaly in all infants, which was severe in more than half, according to a letter published online April 6 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers also observed global hypogyration in the cerebral cortex in all the infants (severe in 78%) and cerebellar hypoplasia in 74%, as well as an abnormally low density of white matter in all cases (N Engl J Med. 2016 April 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1603617).