User login

VIDEO: Identifying preexisting conditions crucial before pneumonectomy, even for benign disease

BOSTON – When performing pneumonectomy on patients with benign disease, it is important to be aware of specific preexisting conditions that could complicate surgery before bringing patients into the operating room.

“Sometimes the usual, standard operative procedure is not appropriate, given the circumstances of a particular patient, [and] typically, these pneumonectomies for benign disease are very challenging operations because the inflamed lung is usually quite densely adherent to the inside of the chest cavity,” explained Dr. G. Alex Patterson of Washington University in St. Louis.

In an interview at the Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Technical Challenges and Complications meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgeons, Dr. Patterson talked about the challenges associated with pneumonectomies for benign disease and how surgeons can safely navigate them.

Dr. Patterson had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – When performing pneumonectomy on patients with benign disease, it is important to be aware of specific preexisting conditions that could complicate surgery before bringing patients into the operating room.

“Sometimes the usual, standard operative procedure is not appropriate, given the circumstances of a particular patient, [and] typically, these pneumonectomies for benign disease are very challenging operations because the inflamed lung is usually quite densely adherent to the inside of the chest cavity,” explained Dr. G. Alex Patterson of Washington University in St. Louis.

In an interview at the Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Technical Challenges and Complications meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgeons, Dr. Patterson talked about the challenges associated with pneumonectomies for benign disease and how surgeons can safely navigate them.

Dr. Patterson had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – When performing pneumonectomy on patients with benign disease, it is important to be aware of specific preexisting conditions that could complicate surgery before bringing patients into the operating room.

“Sometimes the usual, standard operative procedure is not appropriate, given the circumstances of a particular patient, [and] typically, these pneumonectomies for benign disease are very challenging operations because the inflamed lung is usually quite densely adherent to the inside of the chest cavity,” explained Dr. G. Alex Patterson of Washington University in St. Louis.

In an interview at the Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Technical Challenges and Complications meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgeons, Dr. Patterson talked about the challenges associated with pneumonectomies for benign disease and how surgeons can safely navigate them.

Dr. Patterson had no relevant disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT AATS FOCUS ON THORACIC SURGERY

VIDEO: Complications during thoracoscopic lobectomy are surmountable

BOSTON – When it comes to intraoperative complications during thoracoscopic lobectomy, the mantra for success is to always have a preoperative plan, but be flexible enough to improvise should anything out of the norm arise.

“Many surgeons, when they ask [me] about this specific topic, ask what specific tricks [I] have, but I don’t like to use the word ‘trick’ [because] it’s not something we can do that other people can’t,” explained Dr. Thomas A. D’Amico, chief of general thoracic surgery at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“It’s really just about strategy – how you start an operation, what the conduct of it should be, and when you see things that are less common or more difficult cases, how you think about those and manage those.”

In an interview at the Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Technical Challenges and Complications meeting held by the American Association for Thoracic Surgeons, Dr. D’Amico talked about why surgeons around the world are apprehensive about thoracoscopic lobectomy and why it’s important to begin training residents on how to properly perform the procedure as soon as possible, as it helps mitigate uncertainty while giving them valuable experience to solve any issues that may come up during an operation.

Dr. D’Amico disclosed that he is a consultant for Scanlan, but that it is not relevant to this discussion.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – When it comes to intraoperative complications during thoracoscopic lobectomy, the mantra for success is to always have a preoperative plan, but be flexible enough to improvise should anything out of the norm arise.

“Many surgeons, when they ask [me] about this specific topic, ask what specific tricks [I] have, but I don’t like to use the word ‘trick’ [because] it’s not something we can do that other people can’t,” explained Dr. Thomas A. D’Amico, chief of general thoracic surgery at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“It’s really just about strategy – how you start an operation, what the conduct of it should be, and when you see things that are less common or more difficult cases, how you think about those and manage those.”

In an interview at the Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Technical Challenges and Complications meeting held by the American Association for Thoracic Surgeons, Dr. D’Amico talked about why surgeons around the world are apprehensive about thoracoscopic lobectomy and why it’s important to begin training residents on how to properly perform the procedure as soon as possible, as it helps mitigate uncertainty while giving them valuable experience to solve any issues that may come up during an operation.

Dr. D’Amico disclosed that he is a consultant for Scanlan, but that it is not relevant to this discussion.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – When it comes to intraoperative complications during thoracoscopic lobectomy, the mantra for success is to always have a preoperative plan, but be flexible enough to improvise should anything out of the norm arise.

“Many surgeons, when they ask [me] about this specific topic, ask what specific tricks [I] have, but I don’t like to use the word ‘trick’ [because] it’s not something we can do that other people can’t,” explained Dr. Thomas A. D’Amico, chief of general thoracic surgery at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

“It’s really just about strategy – how you start an operation, what the conduct of it should be, and when you see things that are less common or more difficult cases, how you think about those and manage those.”

In an interview at the Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Technical Challenges and Complications meeting held by the American Association for Thoracic Surgeons, Dr. D’Amico talked about why surgeons around the world are apprehensive about thoracoscopic lobectomy and why it’s important to begin training residents on how to properly perform the procedure as soon as possible, as it helps mitigate uncertainty while giving them valuable experience to solve any issues that may come up during an operation.

Dr. D’Amico disclosed that he is a consultant for Scanlan, but that it is not relevant to this discussion.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT AATS FOCUS ON THORACIC SURGERY

Is Skip N2 metastasis its own category?

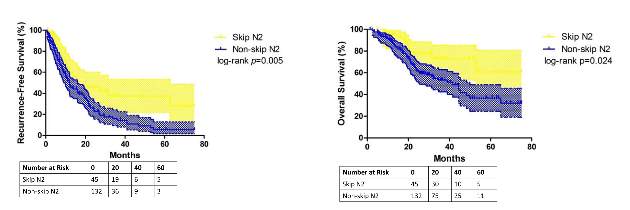

So-called “skip metastasis” of lung cancer to the lymph nodes – when the cancer “skips” over the N1 bronchopulmonary or hilar stage to N2 ipsilateral mediastinal metastasis – may be associated with distinct histological characteristics that can further help understand its association with longer survival and better prognosis in advanced resectable lung adenocarcinoma, according to a small study from China.

Researchers at Fudan (Shanghai ) University Cancer Center published their findings online ahead of print for the October issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015 July 6 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.067]). In all, they enrolled 177 patients with N2 adenocarcinoma, 45 (25.4%) of whom had skip N2 metastasis.

They reported that patients with skip metastasis had considerably better 5-year recurrence-free survival rates of 37.4% vs. 5.7% and better overall survival rates of 60.7% vs. 32.1% when compared with those with non-skip involvement.

“There are distinct differences in clinicopathological features and prognosis in patients with or without skip N2 metastasis,” Dr. Haiquan Chen and his colleagues said. “Considering the results of our study, subclassifications of mediastinal lymph nodes metastases would have potential clinical significance for patients with lung adenocarcinoma.”

Dr. Chen and his colleagues sought to identify specific histological features that characterized the association between skip N2 metastasis and adenocarcinoma subtypes and prognosis. “Skip N2 patients have more cases that are acinar adenocarcinoma subtype, well differentiated and located in the right lung than [do] non-skip patients,” they said.

In fact, they found the predictive value of skip N2 was more significant in patients with right-lung disease, with 5-year recurrence-free survival of 36.6% vs. 0% and overall survival of 57.2% vs. 28% in non–right-lung lesions. They also reported that tumor size of 3 cm or smaller in skip N2 was associated with significantly improved survival rates – 43% vs. 6.7% recurrence-free survival and 74.6% vs. 27.6% for overall survival, compared with patients with larger tumors.

The skip N2 lung adenocarcinoma patients had “remarkably lower incidence” of vascular invasion of the lymph nodes, Dr. Chen and his coauthors wrote. Skip N2 patients also had lower, but not statistically significant, rates of pleural invasion. The Fudan University researchers also reported that the incidence of non-skip N2 metastasis was “significantly high” in patients with papillary-predominant subtype.

“Considering our results, skip N2 should not be recognized as [a] predictor for better survival in all lung adenocarcinoma cases, but in [a] more specific group of patients,” Dr. Chen and his coauthors said.

A multivariate analysis confirmed the predictive significance of skip N2 for recurrence-free survival, but not so much for overall survival. Single N2 metastasis was also an independent predictor for better recurrence-free and overall survival, Dr. Chen and his colleagues said.

The study received funding from the Key Construction Program of the National “985” Project, Ministry of Science and Technology of China; the National Natural Science Foundation of China; the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality; and Shanghai Hospital Development Center.

The authors had no disclosures.

“Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the study by Chen and colleagues is the novel observation that skip metastases seem to correlate with acinar histological subtype of lung adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Valerie Rusch of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015 May 8 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.051]) .

“This nicely performed study adds to the evidence that [non–small cell lung cancer) with skip metastases are a distinct subset of stage IIIa disease,” she said.

Dr. Rusch noted that when the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) revised its lung cancer staging system in 2007 (J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:603-12), a report for which she served as lead author, it considered giving non–small cell lung cancer with skip metastases its own category. However, the authors decided not to do so because of the small numbers of patients who fall into the category.

In the updated histological classification for adenocarcinoma in 2011 from IASLC, along with the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society (J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6[2]:244-85) , papillary and acinar-predominant adenocarcinomas appear to be associated with similar outcomes. However, the Fudan (Shanghai) University researchers suggest “that there may be some important differences between the two subtypes,” Dr. Rusch said.

Because the study population was so small, the results cannot be considered “definitive,” Dr. Rusch said. “In this era of increasingly high throughput molecular medicine, future, much larger-scale analyses are needed to prove or refute these initial results.”

“Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the study by Chen and colleagues is the novel observation that skip metastases seem to correlate with acinar histological subtype of lung adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Valerie Rusch of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015 May 8 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.051]) .

“This nicely performed study adds to the evidence that [non–small cell lung cancer) with skip metastases are a distinct subset of stage IIIa disease,” she said.

Dr. Rusch noted that when the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) revised its lung cancer staging system in 2007 (J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:603-12), a report for which she served as lead author, it considered giving non–small cell lung cancer with skip metastases its own category. However, the authors decided not to do so because of the small numbers of patients who fall into the category.

In the updated histological classification for adenocarcinoma in 2011 from IASLC, along with the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society (J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6[2]:244-85) , papillary and acinar-predominant adenocarcinomas appear to be associated with similar outcomes. However, the Fudan (Shanghai) University researchers suggest “that there may be some important differences between the two subtypes,” Dr. Rusch said.

Because the study population was so small, the results cannot be considered “definitive,” Dr. Rusch said. “In this era of increasingly high throughput molecular medicine, future, much larger-scale analyses are needed to prove or refute these initial results.”

“Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the study by Chen and colleagues is the novel observation that skip metastases seem to correlate with acinar histological subtype of lung adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Valerie Rusch of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015 May 8 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.04.051]) .

“This nicely performed study adds to the evidence that [non–small cell lung cancer) with skip metastases are a distinct subset of stage IIIa disease,” she said.

Dr. Rusch noted that when the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) revised its lung cancer staging system in 2007 (J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:603-12), a report for which she served as lead author, it considered giving non–small cell lung cancer with skip metastases its own category. However, the authors decided not to do so because of the small numbers of patients who fall into the category.

In the updated histological classification for adenocarcinoma in 2011 from IASLC, along with the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society (J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6[2]:244-85) , papillary and acinar-predominant adenocarcinomas appear to be associated with similar outcomes. However, the Fudan (Shanghai) University researchers suggest “that there may be some important differences between the two subtypes,” Dr. Rusch said.

Because the study population was so small, the results cannot be considered “definitive,” Dr. Rusch said. “In this era of increasingly high throughput molecular medicine, future, much larger-scale analyses are needed to prove or refute these initial results.”

So-called “skip metastasis” of lung cancer to the lymph nodes – when the cancer “skips” over the N1 bronchopulmonary or hilar stage to N2 ipsilateral mediastinal metastasis – may be associated with distinct histological characteristics that can further help understand its association with longer survival and better prognosis in advanced resectable lung adenocarcinoma, according to a small study from China.

Researchers at Fudan (Shanghai ) University Cancer Center published their findings online ahead of print for the October issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015 July 6 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.067]). In all, they enrolled 177 patients with N2 adenocarcinoma, 45 (25.4%) of whom had skip N2 metastasis.

They reported that patients with skip metastasis had considerably better 5-year recurrence-free survival rates of 37.4% vs. 5.7% and better overall survival rates of 60.7% vs. 32.1% when compared with those with non-skip involvement.

“There are distinct differences in clinicopathological features and prognosis in patients with or without skip N2 metastasis,” Dr. Haiquan Chen and his colleagues said. “Considering the results of our study, subclassifications of mediastinal lymph nodes metastases would have potential clinical significance for patients with lung adenocarcinoma.”

Dr. Chen and his colleagues sought to identify specific histological features that characterized the association between skip N2 metastasis and adenocarcinoma subtypes and prognosis. “Skip N2 patients have more cases that are acinar adenocarcinoma subtype, well differentiated and located in the right lung than [do] non-skip patients,” they said.

In fact, they found the predictive value of skip N2 was more significant in patients with right-lung disease, with 5-year recurrence-free survival of 36.6% vs. 0% and overall survival of 57.2% vs. 28% in non–right-lung lesions. They also reported that tumor size of 3 cm or smaller in skip N2 was associated with significantly improved survival rates – 43% vs. 6.7% recurrence-free survival and 74.6% vs. 27.6% for overall survival, compared with patients with larger tumors.

The skip N2 lung adenocarcinoma patients had “remarkably lower incidence” of vascular invasion of the lymph nodes, Dr. Chen and his coauthors wrote. Skip N2 patients also had lower, but not statistically significant, rates of pleural invasion. The Fudan University researchers also reported that the incidence of non-skip N2 metastasis was “significantly high” in patients with papillary-predominant subtype.

“Considering our results, skip N2 should not be recognized as [a] predictor for better survival in all lung adenocarcinoma cases, but in [a] more specific group of patients,” Dr. Chen and his coauthors said.

A multivariate analysis confirmed the predictive significance of skip N2 for recurrence-free survival, but not so much for overall survival. Single N2 metastasis was also an independent predictor for better recurrence-free and overall survival, Dr. Chen and his colleagues said.

The study received funding from the Key Construction Program of the National “985” Project, Ministry of Science and Technology of China; the National Natural Science Foundation of China; the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality; and Shanghai Hospital Development Center.

The authors had no disclosures.

So-called “skip metastasis” of lung cancer to the lymph nodes – when the cancer “skips” over the N1 bronchopulmonary or hilar stage to N2 ipsilateral mediastinal metastasis – may be associated with distinct histological characteristics that can further help understand its association with longer survival and better prognosis in advanced resectable lung adenocarcinoma, according to a small study from China.

Researchers at Fudan (Shanghai ) University Cancer Center published their findings online ahead of print for the October issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015 July 6 [doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.03.067]). In all, they enrolled 177 patients with N2 adenocarcinoma, 45 (25.4%) of whom had skip N2 metastasis.

They reported that patients with skip metastasis had considerably better 5-year recurrence-free survival rates of 37.4% vs. 5.7% and better overall survival rates of 60.7% vs. 32.1% when compared with those with non-skip involvement.

“There are distinct differences in clinicopathological features and prognosis in patients with or without skip N2 metastasis,” Dr. Haiquan Chen and his colleagues said. “Considering the results of our study, subclassifications of mediastinal lymph nodes metastases would have potential clinical significance for patients with lung adenocarcinoma.”

Dr. Chen and his colleagues sought to identify specific histological features that characterized the association between skip N2 metastasis and adenocarcinoma subtypes and prognosis. “Skip N2 patients have more cases that are acinar adenocarcinoma subtype, well differentiated and located in the right lung than [do] non-skip patients,” they said.

In fact, they found the predictive value of skip N2 was more significant in patients with right-lung disease, with 5-year recurrence-free survival of 36.6% vs. 0% and overall survival of 57.2% vs. 28% in non–right-lung lesions. They also reported that tumor size of 3 cm or smaller in skip N2 was associated with significantly improved survival rates – 43% vs. 6.7% recurrence-free survival and 74.6% vs. 27.6% for overall survival, compared with patients with larger tumors.

The skip N2 lung adenocarcinoma patients had “remarkably lower incidence” of vascular invasion of the lymph nodes, Dr. Chen and his coauthors wrote. Skip N2 patients also had lower, but not statistically significant, rates of pleural invasion. The Fudan University researchers also reported that the incidence of non-skip N2 metastasis was “significantly high” in patients with papillary-predominant subtype.

“Considering our results, skip N2 should not be recognized as [a] predictor for better survival in all lung adenocarcinoma cases, but in [a] more specific group of patients,” Dr. Chen and his coauthors said.

A multivariate analysis confirmed the predictive significance of skip N2 for recurrence-free survival, but not so much for overall survival. Single N2 metastasis was also an independent predictor for better recurrence-free and overall survival, Dr. Chen and his colleagues said.

The study received funding from the Key Construction Program of the National “985” Project, Ministry of Science and Technology of China; the National Natural Science Foundation of China; the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality; and Shanghai Hospital Development Center.

The authors had no disclosures.

Key clinical point: Skip N2 metastases in resectable lung cancer have distinct histological characteristics from non-skip N2 disease.

Major finding: A subset of patients with skip N2 metastasis had higher rates of acinar adenocarcinoma subtype and right-lung disease.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 177 patients with lung adenocarcinoma and N2 metastasis

Disclosures: The study received funding from the government of China and Shanghai Municipality as well as Shanghai Hospital Development Center. The authors have no relationships to disclose.

Point/Counterpoint: Does surgery play a role in N2 disease treatment following induction therapy?

POINT: Surgery has its uses for some

BY DR. STEPHEN G. SWISHER

When talking about the role of surgery after induction therapy with persistent N2 disease, one must acknowledge that this is such a heterogeneous disease. You can have single-station N2; resectable, bulky multistation N2; and so on. Then there’s unresectable stage IIIA, but let’s focus mainly on resectable stage IIIA disease.

I can’t tell you how many audiences I’ve faced that absolutely believe the myth that surgery plays no role in Stage IIIA non–small cell lung cancer based on data from stage IIIA disease patients randomized to chemoradiation followed by surgery. The problem with these study results is the high mortality in the pneumonectomy subset. There’s no difference in the overall survival of the two groups, but that doesn’t mean that everyone in that group wouldn’t benefit from surgery.

The curve showed that pneumonectomy did not benefit after chemoradiation in a non–high-volume center. You can see a steep drop in the mortality early on, but it catches up again at the end. If you look at the overall 5-year survival rate, even in the pneumonectomy subset, you’re looking at 22% vs. 24%.

But in the lobectomy set, you see something completely different. You’ve got a doubling of survivors and no mortality early on, and a doubling of 5-year survival from 18% to 36%.

And yet, people continue saying that there’s no role for surgery. Well, I think there is a role for surgery, and there are subsets of N2 for which surgery can be particularly beneficial. We have to move more toward what the medical oncologists do, which is personalize therapy and look at subsets of N2 disease so that we know which patients we can benefit and which ones we can’t.

Moving on to the second myth: Surgery plays no role in N2 residual disease after induction therapy. This myth is based on the results of a couple of prospective studies in the 1980s and ’90s that showed residual N2 disease after chemo- and radiotherapy leads to survival of 16-35 months in most cases. I’d say that those results are true, but it’s not to say there aren’t subsets within these populations that benefited. With preoperative chemo and radiation, it’s basically the same thing – poor prognoses in patients with N2 or N3 disease, so the standard becomes never to operate on these individuals.

A European study prospectively took 30 patients and treated them with induction chemotherapy. They saw a 5-year survival rate of 62% if a patient downgrades to lymph node–negative disease and the positron-emission tomographic (PET) findings were good. But they also saw a subset with a small amount of disease within the lymph nodes at the N2 stage and a poor response on PET; Their 5-year survival rate was around 19%. So I’d argue that PET response and the number of lymph nodes involved are the key criteria, and you shouldn’t routinely deny surgery to these patients.

Our experience at MD Anderson Cancer Center over the last 10 years has been to treat N2 and N3 admissions, with surgery, followed by postoperative radiation of 50 Gy. We’re able to achieve very-low morbidity with this regimen, and no mortality after 30 and 90 days. Just to show the heterogeneity: Single-station, microscopic N2 disease should really be resected.

You just can’t lump together everyone with residual N2 after induction therapy, since PET-CTs and most other diagnostic procedures have high false-negative rates. And like I’ve said, it doesn’t matter because N2 disease is really a subset disease. Microscopic N2 disease behaves in a completely different way than does macroscopic, multiple-level N2 disease. And even more important is how the patient’s primary tumor responds to the chemotherapy or chemoradiation; that will tell you how well they’re going to do even if they have a small amount of residual disease in the lymph nodes.

Dr. Swisher is at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. He disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for GlaxoSmithKline.

COUNTERPOINT: Surgery seems to have little value, adds risk.

BY DR. SCOTT J. SWANSON

Dr. Swisher and I probably agree more than we disagree, but I’m going to start by saying that N2 disease is bad, and most of these populations are heterogeneous. But if you feel that a curve toward the bottom of a graph is good, then you should think twice. Anywhere from a 15%-30% survival rate is not great and shows that we have a long way to go. The overall impression among oncologists in several countries is that it’s not really clear whether surgery adds value. Even in very good centers like MD Anderson where there is minimal risk, surgery inherently still involves some risk.

So then, what do we do with persistent N2 disease? I’d say that most of the time, it should be treated with chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiation. In some cases, N2 disease can be treated with a creative, mutation-driven immunotherapy approach. Most of the time though, surgery is just not a good idea.

Interestingly, about one-third of lung cancer patients present with stage IIIA disease, so it’s important that we as a medical community sort out these treatment options. I think we’re all in agreement that single-station, microscopic, PET-negative/CT-negative disease is not the same as extranodal or multistation PET-positive disease, so we’ve got to begin to substratify N2 disease.

In an intergroup trial of about 200 patients per arm published in the Lancet, patients went to surgery if they didn’t regress after evaluation. The progression-free survival rate did seem to favor surgery; and, if you look at the lobectomy subset, the results are certainly strong. But again, we’re dealing with curves that are pretty low. The pneumonectomy subset drops off and then starts to catch up, but clearly pneumonectomy was a problem in this multicenter trial. The most important graph to this debate shows subjects that persistently had nodal disease had very poor survival. It’s hard to argue for surgery when results show that only about 24% of them are going to be alive down the road. If oncologists across most of the United States say they believe that surgery isn’t a good idea, we’re not going to use this graph to change their minds; we need to change our way of thinking.

So the conclusion to take away from that presentation is that N0 status at surgery significantly predicts greater 5-year survival. So, conversely, surgery is not helpful for the patient with node-positive disease. Surgical resection should only be considered if lobectomy is the operation in question. Pneumonectomy carries risk, and surgery has no beneficial value, compared with chemotherapy unless the patient has been downstaged.

Our experience at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston is similar to Dr. Swisher’s at MD Anderson. During the first 8 years of our thoracic division, we looked at 103 patients who had surgery after induction therapy for N2 disease. The induction plan in those patients was chemotherapy only for 75, radiation only for 18, and chemoradiation for 10. Almost 40% of patients had pneumonectomies, and the rest had lobectomies.

Mortality was 3.9%, major morbidity was 7%, and about 30% were downstaged. Those 5-year survival rates were about 36%. Persistent nodal disease, either N1 or N2, was seen in about 75%, and most of them were N2; the 5-year survival rate there was about 9% with a median of about 15.9 months. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so you may look at that and say that 15.9 months isn’t bad, but there’s still a huge subgroup that’s node positive, so here I’d say that pushing surgery is not the best strategy. We also found in this group that adenocarcinomas were much harder to clear.

We’re on very-safe ground to push surgery in the node-negative group, but you’ve got to be careful in the node-positive group.

Survival is relatively limited in N2 disease in general. Surgery may be of value if you downstage the patient, if you’re doing a lobectomy or if you see squamous cell carcinoma. Going forward, we really ought to focus our attention on identifying responders more reliably and improving downstaging – with different or individualized chemotherapy, or perhaps even immunologic therapy.

For the present, we can talk about radiation dosing. High-dose radiation is clearly a viable option for some patients. In addition, we can improve identification of N2 subgroups. Not all N2 disease is the same, so it should not be treated the same across the board.

Dr. Swanson is at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for Covidien and Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

This article grew out of the debate by Dr. Swisher and Dr. Swanson at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

POINT: Surgery has its uses for some

BY DR. STEPHEN G. SWISHER

When talking about the role of surgery after induction therapy with persistent N2 disease, one must acknowledge that this is such a heterogeneous disease. You can have single-station N2; resectable, bulky multistation N2; and so on. Then there’s unresectable stage IIIA, but let’s focus mainly on resectable stage IIIA disease.

I can’t tell you how many audiences I’ve faced that absolutely believe the myth that surgery plays no role in Stage IIIA non–small cell lung cancer based on data from stage IIIA disease patients randomized to chemoradiation followed by surgery. The problem with these study results is the high mortality in the pneumonectomy subset. There’s no difference in the overall survival of the two groups, but that doesn’t mean that everyone in that group wouldn’t benefit from surgery.

The curve showed that pneumonectomy did not benefit after chemoradiation in a non–high-volume center. You can see a steep drop in the mortality early on, but it catches up again at the end. If you look at the overall 5-year survival rate, even in the pneumonectomy subset, you’re looking at 22% vs. 24%.

But in the lobectomy set, you see something completely different. You’ve got a doubling of survivors and no mortality early on, and a doubling of 5-year survival from 18% to 36%.

And yet, people continue saying that there’s no role for surgery. Well, I think there is a role for surgery, and there are subsets of N2 for which surgery can be particularly beneficial. We have to move more toward what the medical oncologists do, which is personalize therapy and look at subsets of N2 disease so that we know which patients we can benefit and which ones we can’t.

Moving on to the second myth: Surgery plays no role in N2 residual disease after induction therapy. This myth is based on the results of a couple of prospective studies in the 1980s and ’90s that showed residual N2 disease after chemo- and radiotherapy leads to survival of 16-35 months in most cases. I’d say that those results are true, but it’s not to say there aren’t subsets within these populations that benefited. With preoperative chemo and radiation, it’s basically the same thing – poor prognoses in patients with N2 or N3 disease, so the standard becomes never to operate on these individuals.

A European study prospectively took 30 patients and treated them with induction chemotherapy. They saw a 5-year survival rate of 62% if a patient downgrades to lymph node–negative disease and the positron-emission tomographic (PET) findings were good. But they also saw a subset with a small amount of disease within the lymph nodes at the N2 stage and a poor response on PET; Their 5-year survival rate was around 19%. So I’d argue that PET response and the number of lymph nodes involved are the key criteria, and you shouldn’t routinely deny surgery to these patients.

Our experience at MD Anderson Cancer Center over the last 10 years has been to treat N2 and N3 admissions, with surgery, followed by postoperative radiation of 50 Gy. We’re able to achieve very-low morbidity with this regimen, and no mortality after 30 and 90 days. Just to show the heterogeneity: Single-station, microscopic N2 disease should really be resected.

You just can’t lump together everyone with residual N2 after induction therapy, since PET-CTs and most other diagnostic procedures have high false-negative rates. And like I’ve said, it doesn’t matter because N2 disease is really a subset disease. Microscopic N2 disease behaves in a completely different way than does macroscopic, multiple-level N2 disease. And even more important is how the patient’s primary tumor responds to the chemotherapy or chemoradiation; that will tell you how well they’re going to do even if they have a small amount of residual disease in the lymph nodes.

Dr. Swisher is at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. He disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for GlaxoSmithKline.

COUNTERPOINT: Surgery seems to have little value, adds risk.

BY DR. SCOTT J. SWANSON

Dr. Swisher and I probably agree more than we disagree, but I’m going to start by saying that N2 disease is bad, and most of these populations are heterogeneous. But if you feel that a curve toward the bottom of a graph is good, then you should think twice. Anywhere from a 15%-30% survival rate is not great and shows that we have a long way to go. The overall impression among oncologists in several countries is that it’s not really clear whether surgery adds value. Even in very good centers like MD Anderson where there is minimal risk, surgery inherently still involves some risk.

So then, what do we do with persistent N2 disease? I’d say that most of the time, it should be treated with chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiation. In some cases, N2 disease can be treated with a creative, mutation-driven immunotherapy approach. Most of the time though, surgery is just not a good idea.

Interestingly, about one-third of lung cancer patients present with stage IIIA disease, so it’s important that we as a medical community sort out these treatment options. I think we’re all in agreement that single-station, microscopic, PET-negative/CT-negative disease is not the same as extranodal or multistation PET-positive disease, so we’ve got to begin to substratify N2 disease.

In an intergroup trial of about 200 patients per arm published in the Lancet, patients went to surgery if they didn’t regress after evaluation. The progression-free survival rate did seem to favor surgery; and, if you look at the lobectomy subset, the results are certainly strong. But again, we’re dealing with curves that are pretty low. The pneumonectomy subset drops off and then starts to catch up, but clearly pneumonectomy was a problem in this multicenter trial. The most important graph to this debate shows subjects that persistently had nodal disease had very poor survival. It’s hard to argue for surgery when results show that only about 24% of them are going to be alive down the road. If oncologists across most of the United States say they believe that surgery isn’t a good idea, we’re not going to use this graph to change their minds; we need to change our way of thinking.

So the conclusion to take away from that presentation is that N0 status at surgery significantly predicts greater 5-year survival. So, conversely, surgery is not helpful for the patient with node-positive disease. Surgical resection should only be considered if lobectomy is the operation in question. Pneumonectomy carries risk, and surgery has no beneficial value, compared with chemotherapy unless the patient has been downstaged.

Our experience at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston is similar to Dr. Swisher’s at MD Anderson. During the first 8 years of our thoracic division, we looked at 103 patients who had surgery after induction therapy for N2 disease. The induction plan in those patients was chemotherapy only for 75, radiation only for 18, and chemoradiation for 10. Almost 40% of patients had pneumonectomies, and the rest had lobectomies.

Mortality was 3.9%, major morbidity was 7%, and about 30% were downstaged. Those 5-year survival rates were about 36%. Persistent nodal disease, either N1 or N2, was seen in about 75%, and most of them were N2; the 5-year survival rate there was about 9% with a median of about 15.9 months. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so you may look at that and say that 15.9 months isn’t bad, but there’s still a huge subgroup that’s node positive, so here I’d say that pushing surgery is not the best strategy. We also found in this group that adenocarcinomas were much harder to clear.

We’re on very-safe ground to push surgery in the node-negative group, but you’ve got to be careful in the node-positive group.

Survival is relatively limited in N2 disease in general. Surgery may be of value if you downstage the patient, if you’re doing a lobectomy or if you see squamous cell carcinoma. Going forward, we really ought to focus our attention on identifying responders more reliably and improving downstaging – with different or individualized chemotherapy, or perhaps even immunologic therapy.

For the present, we can talk about radiation dosing. High-dose radiation is clearly a viable option for some patients. In addition, we can improve identification of N2 subgroups. Not all N2 disease is the same, so it should not be treated the same across the board.

Dr. Swanson is at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for Covidien and Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

This article grew out of the debate by Dr. Swisher and Dr. Swanson at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

POINT: Surgery has its uses for some

BY DR. STEPHEN G. SWISHER

When talking about the role of surgery after induction therapy with persistent N2 disease, one must acknowledge that this is such a heterogeneous disease. You can have single-station N2; resectable, bulky multistation N2; and so on. Then there’s unresectable stage IIIA, but let’s focus mainly on resectable stage IIIA disease.

I can’t tell you how many audiences I’ve faced that absolutely believe the myth that surgery plays no role in Stage IIIA non–small cell lung cancer based on data from stage IIIA disease patients randomized to chemoradiation followed by surgery. The problem with these study results is the high mortality in the pneumonectomy subset. There’s no difference in the overall survival of the two groups, but that doesn’t mean that everyone in that group wouldn’t benefit from surgery.

The curve showed that pneumonectomy did not benefit after chemoradiation in a non–high-volume center. You can see a steep drop in the mortality early on, but it catches up again at the end. If you look at the overall 5-year survival rate, even in the pneumonectomy subset, you’re looking at 22% vs. 24%.

But in the lobectomy set, you see something completely different. You’ve got a doubling of survivors and no mortality early on, and a doubling of 5-year survival from 18% to 36%.

And yet, people continue saying that there’s no role for surgery. Well, I think there is a role for surgery, and there are subsets of N2 for which surgery can be particularly beneficial. We have to move more toward what the medical oncologists do, which is personalize therapy and look at subsets of N2 disease so that we know which patients we can benefit and which ones we can’t.

Moving on to the second myth: Surgery plays no role in N2 residual disease after induction therapy. This myth is based on the results of a couple of prospective studies in the 1980s and ’90s that showed residual N2 disease after chemo- and radiotherapy leads to survival of 16-35 months in most cases. I’d say that those results are true, but it’s not to say there aren’t subsets within these populations that benefited. With preoperative chemo and radiation, it’s basically the same thing – poor prognoses in patients with N2 or N3 disease, so the standard becomes never to operate on these individuals.

A European study prospectively took 30 patients and treated them with induction chemotherapy. They saw a 5-year survival rate of 62% if a patient downgrades to lymph node–negative disease and the positron-emission tomographic (PET) findings were good. But they also saw a subset with a small amount of disease within the lymph nodes at the N2 stage and a poor response on PET; Their 5-year survival rate was around 19%. So I’d argue that PET response and the number of lymph nodes involved are the key criteria, and you shouldn’t routinely deny surgery to these patients.

Our experience at MD Anderson Cancer Center over the last 10 years has been to treat N2 and N3 admissions, with surgery, followed by postoperative radiation of 50 Gy. We’re able to achieve very-low morbidity with this regimen, and no mortality after 30 and 90 days. Just to show the heterogeneity: Single-station, microscopic N2 disease should really be resected.

You just can’t lump together everyone with residual N2 after induction therapy, since PET-CTs and most other diagnostic procedures have high false-negative rates. And like I’ve said, it doesn’t matter because N2 disease is really a subset disease. Microscopic N2 disease behaves in a completely different way than does macroscopic, multiple-level N2 disease. And even more important is how the patient’s primary tumor responds to the chemotherapy or chemoradiation; that will tell you how well they’re going to do even if they have a small amount of residual disease in the lymph nodes.

Dr. Swisher is at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. He disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for GlaxoSmithKline.

COUNTERPOINT: Surgery seems to have little value, adds risk.

BY DR. SCOTT J. SWANSON

Dr. Swisher and I probably agree more than we disagree, but I’m going to start by saying that N2 disease is bad, and most of these populations are heterogeneous. But if you feel that a curve toward the bottom of a graph is good, then you should think twice. Anywhere from a 15%-30% survival rate is not great and shows that we have a long way to go. The overall impression among oncologists in several countries is that it’s not really clear whether surgery adds value. Even in very good centers like MD Anderson where there is minimal risk, surgery inherently still involves some risk.

So then, what do we do with persistent N2 disease? I’d say that most of the time, it should be treated with chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiation. In some cases, N2 disease can be treated with a creative, mutation-driven immunotherapy approach. Most of the time though, surgery is just not a good idea.

Interestingly, about one-third of lung cancer patients present with stage IIIA disease, so it’s important that we as a medical community sort out these treatment options. I think we’re all in agreement that single-station, microscopic, PET-negative/CT-negative disease is not the same as extranodal or multistation PET-positive disease, so we’ve got to begin to substratify N2 disease.

In an intergroup trial of about 200 patients per arm published in the Lancet, patients went to surgery if they didn’t regress after evaluation. The progression-free survival rate did seem to favor surgery; and, if you look at the lobectomy subset, the results are certainly strong. But again, we’re dealing with curves that are pretty low. The pneumonectomy subset drops off and then starts to catch up, but clearly pneumonectomy was a problem in this multicenter trial. The most important graph to this debate shows subjects that persistently had nodal disease had very poor survival. It’s hard to argue for surgery when results show that only about 24% of them are going to be alive down the road. If oncologists across most of the United States say they believe that surgery isn’t a good idea, we’re not going to use this graph to change their minds; we need to change our way of thinking.

So the conclusion to take away from that presentation is that N0 status at surgery significantly predicts greater 5-year survival. So, conversely, surgery is not helpful for the patient with node-positive disease. Surgical resection should only be considered if lobectomy is the operation in question. Pneumonectomy carries risk, and surgery has no beneficial value, compared with chemotherapy unless the patient has been downstaged.

Our experience at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston is similar to Dr. Swisher’s at MD Anderson. During the first 8 years of our thoracic division, we looked at 103 patients who had surgery after induction therapy for N2 disease. The induction plan in those patients was chemotherapy only for 75, radiation only for 18, and chemoradiation for 10. Almost 40% of patients had pneumonectomies, and the rest had lobectomies.

Mortality was 3.9%, major morbidity was 7%, and about 30% were downstaged. Those 5-year survival rates were about 36%. Persistent nodal disease, either N1 or N2, was seen in about 75%, and most of them were N2; the 5-year survival rate there was about 9% with a median of about 15.9 months. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so you may look at that and say that 15.9 months isn’t bad, but there’s still a huge subgroup that’s node positive, so here I’d say that pushing surgery is not the best strategy. We also found in this group that adenocarcinomas were much harder to clear.

We’re on very-safe ground to push surgery in the node-negative group, but you’ve got to be careful in the node-positive group.

Survival is relatively limited in N2 disease in general. Surgery may be of value if you downstage the patient, if you’re doing a lobectomy or if you see squamous cell carcinoma. Going forward, we really ought to focus our attention on identifying responders more reliably and improving downstaging – with different or individualized chemotherapy, or perhaps even immunologic therapy.

For the present, we can talk about radiation dosing. High-dose radiation is clearly a viable option for some patients. In addition, we can improve identification of N2 subgroups. Not all N2 disease is the same, so it should not be treated the same across the board.

Dr. Swanson is at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He disclosed that he is a consultant/advisory board member for Covidien and Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

This article grew out of the debate by Dr. Swisher and Dr. Swanson at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Clinical advances drive lung cancer staging, classification changes

DENVER – The term “precision medicine” can be applied to both clinical care and to pathology, as newly updated staging and classification systems for lung cancer show.

The proposed revised (8th) edition of the TNM staging system for lung cancer gives more weight to tumor size as a prognostic factor, reclassifies some primary tumor (T) descriptors, validates current nodal status (N) descriptors, modifies the definition of some types of metastases (M), and includes additional stages for better prognostic stratification, reported Dr. Ramón Rami-Porta from the Universitari Mútua Terrassa in Barcelona, at a world conference on lung cancer sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Similarly, the updated World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Lung Tumors, described by Dr. William D. Travis from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, incorporates knowledge gained from immunohistochemistry and molecular testing for common genetic mutations into recommendations for treating the specific clinical circumstances of patients with lung cancer.

WHO’s Next

“The 2015 WHO Classification captures a remarkable decade of advances in every lung cancer specialty, from pathology – including histology, cytology, immunohistochemistry, genetics – to oncology, surgery, radiology, and epidemiology. The rapid expansion of immunohistochemical and molecular tools has had a profound impact on how we were able to reclassify a number of tumors, in addition to how we were able to contribute to improvement of subtyping of lung cancers, particularly non–small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Travis said at a media briefing following his discussion of the new classification at a plenary session.

The changes are expected to improve clinical management of patients with advanced lung cancer by clarifying criteria and terminology for small biopsies and cytology, establishing more accurate histologic subtyping, suggesting strategic management of small tissues, and streamlining the work flow for molecular testing. The classification also emphasizes the need for multidisciplinary cooperation among myriad clinicians, he said.

For surgically resected patients, the classification officially recognizes for the first time subsets of non–small cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology with survival rates of 100% (adenocarcinoma in situ), or nearly 100% (minimally invasive adenocarcinoma).

Among the major changes that will affect the diagnosis of surgically resected patients are the adoption of the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS Lung Adenocarcinoma Classification, restriction of a diagnosis of large cell carcinoma to tumors lacking clear differentiation by both immunohistochemistry and morphology, reclassifying of squamous cancers into keratinizing, nonkeratinizing, and basaloid subtypes with elimination of clear cell, small cell, and papillary subtypes. Neuroendocrine subtypes are grouped together, but their classification otherwise remains largely unchanged.

The revised classification is expected to improve prediction of survival and recurrence, predict whether a patient is likely to have a survival benefit with platinum-based chemotherapy, allow radiologic pathologic correlations, and affects TNM staging by emphasizing solid tumor size (vs. whole tumor size), Dr. Travis said.

TNM Changes

The proposed changes to the TNM tumor staging have been submitted for approval to the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the Union for International Cancer Control.

If adopted, they would represent the first significant changes since the 7th edition’s publication in 2009. The changes are based on data on more than 77,000 patients diagnosed with lung cancer from 1999 through 2010.

The proposed changes are not intended, however, to alter clinical practice, and instead “imply a taxonomic refinement rather than new indications of already established treatment protocols,” Dr. Rami-Porta said.

In some cases, the proposed changes would result in an upgrading of the T stage, while others would result in downgrading. For example, tumors that range in size between 1 and 2 cm, designated T1a in the 7th edition, would be T1b in the 8th edition. Similarly, tumors larger than 2 cm and up to 3 cm would be upgraded from T1b to T1c, those larger than 4 up to 5 would go from T2a to T2b, those larger 5 and up to 7 cm would rise from T2b to T3, and those larger than 7 cm would be reclassified from T3 to T4. Tumors invading the diaphragm would also be upgraded from T3 to T4 under the proposed revisions.

In contrast, tumors with limited invasion of the trachea (bronchus less than 2 cm from the carina) would be downgraded from T3 to T2, as would tumors associated with total atelectasis and/or pneumonitis.

The current N descriptors are adequate for predicting prognosis, the investigators determined, prompting the recommendation to retain them in the new edition.

The investigators propose slight changes to the M descriptors of metastases. Although they found no significant differences in survival found among patients with M1a (metastases within the chest cavity) descriptors, when distant metastases outside the chest cavity (M1b) were assessed by to the number of metastases, they found that patients with tumors with one metastasis in one organ had significantly better outcomes than those who had multiple metastases in one or more organs.

The proposed revision would continue to group in the M1a category cases with pleural/pericardial effusions, contralateral/bilateral lung nodules, contralateral/bilateral pleural nodules, or a combination of multiple parameters. However, single metastatic lesions in a single distant organ would be reclassified as M1b, and multiple lesions in a single organ or multiple lesions in multiple organs would be reclassified as M1c.

DENVER – The term “precision medicine” can be applied to both clinical care and to pathology, as newly updated staging and classification systems for lung cancer show.

The proposed revised (8th) edition of the TNM staging system for lung cancer gives more weight to tumor size as a prognostic factor, reclassifies some primary tumor (T) descriptors, validates current nodal status (N) descriptors, modifies the definition of some types of metastases (M), and includes additional stages for better prognostic stratification, reported Dr. Ramón Rami-Porta from the Universitari Mútua Terrassa in Barcelona, at a world conference on lung cancer sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Similarly, the updated World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Lung Tumors, described by Dr. William D. Travis from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, incorporates knowledge gained from immunohistochemistry and molecular testing for common genetic mutations into recommendations for treating the specific clinical circumstances of patients with lung cancer.

WHO’s Next

“The 2015 WHO Classification captures a remarkable decade of advances in every lung cancer specialty, from pathology – including histology, cytology, immunohistochemistry, genetics – to oncology, surgery, radiology, and epidemiology. The rapid expansion of immunohistochemical and molecular tools has had a profound impact on how we were able to reclassify a number of tumors, in addition to how we were able to contribute to improvement of subtyping of lung cancers, particularly non–small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Travis said at a media briefing following his discussion of the new classification at a plenary session.

The changes are expected to improve clinical management of patients with advanced lung cancer by clarifying criteria and terminology for small biopsies and cytology, establishing more accurate histologic subtyping, suggesting strategic management of small tissues, and streamlining the work flow for molecular testing. The classification also emphasizes the need for multidisciplinary cooperation among myriad clinicians, he said.

For surgically resected patients, the classification officially recognizes for the first time subsets of non–small cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology with survival rates of 100% (adenocarcinoma in situ), or nearly 100% (minimally invasive adenocarcinoma).

Among the major changes that will affect the diagnosis of surgically resected patients are the adoption of the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS Lung Adenocarcinoma Classification, restriction of a diagnosis of large cell carcinoma to tumors lacking clear differentiation by both immunohistochemistry and morphology, reclassifying of squamous cancers into keratinizing, nonkeratinizing, and basaloid subtypes with elimination of clear cell, small cell, and papillary subtypes. Neuroendocrine subtypes are grouped together, but their classification otherwise remains largely unchanged.

The revised classification is expected to improve prediction of survival and recurrence, predict whether a patient is likely to have a survival benefit with platinum-based chemotherapy, allow radiologic pathologic correlations, and affects TNM staging by emphasizing solid tumor size (vs. whole tumor size), Dr. Travis said.

TNM Changes

The proposed changes to the TNM tumor staging have been submitted for approval to the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the Union for International Cancer Control.

If adopted, they would represent the first significant changes since the 7th edition’s publication in 2009. The changes are based on data on more than 77,000 patients diagnosed with lung cancer from 1999 through 2010.

The proposed changes are not intended, however, to alter clinical practice, and instead “imply a taxonomic refinement rather than new indications of already established treatment protocols,” Dr. Rami-Porta said.

In some cases, the proposed changes would result in an upgrading of the T stage, while others would result in downgrading. For example, tumors that range in size between 1 and 2 cm, designated T1a in the 7th edition, would be T1b in the 8th edition. Similarly, tumors larger than 2 cm and up to 3 cm would be upgraded from T1b to T1c, those larger than 4 up to 5 would go from T2a to T2b, those larger 5 and up to 7 cm would rise from T2b to T3, and those larger than 7 cm would be reclassified from T3 to T4. Tumors invading the diaphragm would also be upgraded from T3 to T4 under the proposed revisions.

In contrast, tumors with limited invasion of the trachea (bronchus less than 2 cm from the carina) would be downgraded from T3 to T2, as would tumors associated with total atelectasis and/or pneumonitis.

The current N descriptors are adequate for predicting prognosis, the investigators determined, prompting the recommendation to retain them in the new edition.

The investigators propose slight changes to the M descriptors of metastases. Although they found no significant differences in survival found among patients with M1a (metastases within the chest cavity) descriptors, when distant metastases outside the chest cavity (M1b) were assessed by to the number of metastases, they found that patients with tumors with one metastasis in one organ had significantly better outcomes than those who had multiple metastases in one or more organs.

The proposed revision would continue to group in the M1a category cases with pleural/pericardial effusions, contralateral/bilateral lung nodules, contralateral/bilateral pleural nodules, or a combination of multiple parameters. However, single metastatic lesions in a single distant organ would be reclassified as M1b, and multiple lesions in a single organ or multiple lesions in multiple organs would be reclassified as M1c.

DENVER – The term “precision medicine” can be applied to both clinical care and to pathology, as newly updated staging and classification systems for lung cancer show.

The proposed revised (8th) edition of the TNM staging system for lung cancer gives more weight to tumor size as a prognostic factor, reclassifies some primary tumor (T) descriptors, validates current nodal status (N) descriptors, modifies the definition of some types of metastases (M), and includes additional stages for better prognostic stratification, reported Dr. Ramón Rami-Porta from the Universitari Mútua Terrassa in Barcelona, at a world conference on lung cancer sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Similarly, the updated World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Lung Tumors, described by Dr. William D. Travis from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, incorporates knowledge gained from immunohistochemistry and molecular testing for common genetic mutations into recommendations for treating the specific clinical circumstances of patients with lung cancer.

WHO’s Next

“The 2015 WHO Classification captures a remarkable decade of advances in every lung cancer specialty, from pathology – including histology, cytology, immunohistochemistry, genetics – to oncology, surgery, radiology, and epidemiology. The rapid expansion of immunohistochemical and molecular tools has had a profound impact on how we were able to reclassify a number of tumors, in addition to how we were able to contribute to improvement of subtyping of lung cancers, particularly non–small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Travis said at a media briefing following his discussion of the new classification at a plenary session.

The changes are expected to improve clinical management of patients with advanced lung cancer by clarifying criteria and terminology for small biopsies and cytology, establishing more accurate histologic subtyping, suggesting strategic management of small tissues, and streamlining the work flow for molecular testing. The classification also emphasizes the need for multidisciplinary cooperation among myriad clinicians, he said.

For surgically resected patients, the classification officially recognizes for the first time subsets of non–small cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology with survival rates of 100% (adenocarcinoma in situ), or nearly 100% (minimally invasive adenocarcinoma).

Among the major changes that will affect the diagnosis of surgically resected patients are the adoption of the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS Lung Adenocarcinoma Classification, restriction of a diagnosis of large cell carcinoma to tumors lacking clear differentiation by both immunohistochemistry and morphology, reclassifying of squamous cancers into keratinizing, nonkeratinizing, and basaloid subtypes with elimination of clear cell, small cell, and papillary subtypes. Neuroendocrine subtypes are grouped together, but their classification otherwise remains largely unchanged.

The revised classification is expected to improve prediction of survival and recurrence, predict whether a patient is likely to have a survival benefit with platinum-based chemotherapy, allow radiologic pathologic correlations, and affects TNM staging by emphasizing solid tumor size (vs. whole tumor size), Dr. Travis said.

TNM Changes

The proposed changes to the TNM tumor staging have been submitted for approval to the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the Union for International Cancer Control.

If adopted, they would represent the first significant changes since the 7th edition’s publication in 2009. The changes are based on data on more than 77,000 patients diagnosed with lung cancer from 1999 through 2010.

The proposed changes are not intended, however, to alter clinical practice, and instead “imply a taxonomic refinement rather than new indications of already established treatment protocols,” Dr. Rami-Porta said.

In some cases, the proposed changes would result in an upgrading of the T stage, while others would result in downgrading. For example, tumors that range in size between 1 and 2 cm, designated T1a in the 7th edition, would be T1b in the 8th edition. Similarly, tumors larger than 2 cm and up to 3 cm would be upgraded from T1b to T1c, those larger than 4 up to 5 would go from T2a to T2b, those larger 5 and up to 7 cm would rise from T2b to T3, and those larger than 7 cm would be reclassified from T3 to T4. Tumors invading the diaphragm would also be upgraded from T3 to T4 under the proposed revisions.

In contrast, tumors with limited invasion of the trachea (bronchus less than 2 cm from the carina) would be downgraded from T3 to T2, as would tumors associated with total atelectasis and/or pneumonitis.

The current N descriptors are adequate for predicting prognosis, the investigators determined, prompting the recommendation to retain them in the new edition.

The investigators propose slight changes to the M descriptors of metastases. Although they found no significant differences in survival found among patients with M1a (metastases within the chest cavity) descriptors, when distant metastases outside the chest cavity (M1b) were assessed by to the number of metastases, they found that patients with tumors with one metastasis in one organ had significantly better outcomes than those who had multiple metastases in one or more organs.

The proposed revision would continue to group in the M1a category cases with pleural/pericardial effusions, contralateral/bilateral lung nodules, contralateral/bilateral pleural nodules, or a combination of multiple parameters. However, single metastatic lesions in a single distant organ would be reclassified as M1b, and multiple lesions in a single organ or multiple lesions in multiple organs would be reclassified as M1c.

AT THE IASLC WORLD CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Improved understanding of lung cancer over the last decade has prompted updates to international tumor staging and classification systems.

Major finding: The WHO 2015 Classification of Lung Tumors is expected to aid clinical practice.

Data source: Conference presentation of key changes to the WHO Classification and TNM staging system.

Disclosures: Dr. Travis and Dr. Rami-Porta reported having no disclosures relevant to their presentations.

Assessing progression, impact of radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus

Patients with Barrett’s esophagus have about a 0.2% annual chance of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma in the 5 years after initial diagnosis, but the likelihood then rises so that about 9% of all patients will develop cancer by 20 years out, according to a study in the September issue of Gastroenterology.

The modeled rates of progression for the early years after diagnosis are substantially lower than are those reported by prospective studies, which involve more intensive surveillance and therefore suffer from detection bias, said Dr. Sonja Kroep of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her associates. “Clinicians informing their patients about their cancer risk can best use this clinical progression rate, which is not influenced by surveillance-detected cancers,” they wrote.

Past analyses have yielded varying results for the rate at which Barrett’s esophagus with low-grade dysplasia progresses to high-grade dysplasia and esophageal carcinoma. For their study, Dr. Kroep and her associates calibrated a model based on the annual rate of 0.18% reported by population-level studies, and used it to simulate prospective studies and to predict results from both population-based and prospective studies for various follow-up periods (Gastroenterology 2015 Apr 29. pii: S0016-5085(15)00601-0).

For the first 5 years of follow-up, the model predicted a 0.19% annual rate of transformation to esophageal adenocarcinoma for population-based studies and a 0.36% annual rate for prospective studies, the researchers reported. At 20 years, these rates rose to 0.63% and 0.65% annually, for a cumulative incidence rate of 9.1% to 9.5%. Between the 5-year and 20-year thresholds, the gap between rates of progression for the two types of studies narrowed from 91% to 5%. Taken together, the findings suggest that for the first 5 years after a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus, rates of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma reflect those from population-level studies instead of surveillance-based prospective studies, the investigators said. “Clinicians should use this information to explain to patients their short-term and long-term risks if no action is taken, and then discuss the risks and benefits of surveillance,” they added.

In a separate retrospective study, radiofrequency ablation of low-grade esophageal dysplasia was linked to substantially lower rates of progression compared with watchful waiting in the form of endoscopic surveillance, said Dr. Aaron Small of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates. Their study included 125 patients with Barrett’s esophagus and low-grade dysplasia who underwent surveillance only, and 45 patients who underwent radiofrequency ablation at three university medical centers.

Over median follow-up periods of more than 2 years, the risk of progression with radiofrequency ablation was significantly lower than with endoscopic surveillance only, even after the researchers controlled for year of diagnosis (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.06; 95% confidence interval, 0.008-0.48; P = .008). The ablation group also had fewer visible macroscopic lesions, although the difference was not significant. “We estimate that for every three patients treated with radiofrequency ablation, one additional patient with low-grade dysplasia will avoid progression to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma within 3 years,” the researchers wrote. “Although selection bias cannot be excluded, these findings provide additional evidence for the use of endoscopic ablation therapy for low-grade dysplasia” (Gastroenterology 2015 Apr 24. pii: S0016-5085(15)00569-7).

The study by Dr. Kroep and her associates was funded by grant U01 CA152926, and the investigators reported having no conflicts of interest. The study by Dr. Small and his associates was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and by institutional funds. Dr. Small reported no conflicts of interest, but seven coauthors reported ties with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

These two studies highlight two different hot topics in the management of patients with a Barrett’s esophagus. The first is the low rate of neoplastic progression in patients undergoing surveillance for nondysplastic BE. The second relates to the management of patients with low-grade dysplasia (LG

|

| Dr. Jacques Bergman |

Population-based BE surveillance studies have shown lower progression rates than have prospective surveillance studies. The biggest difference between these two is that not all patients in population-based studies actually undergo subsequent surveillance endoscopies and/or surveillance is carried out less rigorously than in prospective surveillance studies. Patients who have undergone a baseline endoscopy showing no neoplasia first need to develop early neoplasia (which is generally asymptomatic) that then needs to progress to a symptomatic stage before they are diagnosed. During this interval they may die from other causes or may be lost to follow-up. Patients in strict surveillance programs will be diagnosed at an earlier stage and at a higher rate. This is especially true in the first years of follow-up, when the initial screening endoscopy has its largest effect. Over time, the difference then fades away as suggested by the 9% progression rate of both types of studies at 20 years of follow-up. Both perspectives are relevant for patients. For elderly patients with significant comorbidity, the 5-year data from population-based studies reassure them not to undergo surveillance endoscopies because even when an early cancer develops it is unlikely to bear any clinical relevance, whereas for patients with a long life expectancy, the 9% cancer risk at 20 years and the dismal prognosis of a symptomatic Barrett’s cancer may be strong arguments for participating in a surveillance program.

For patients with LGD, the situation is different: The rate of progression is much higher than that reported for nondysplastic BE, and with radiofrequency ablation (RFA), an effective and safe tool is at hand to significantly reduce this rate of neoplastic progression. Small et al. reported that only three patients need to be treated with RFA to prevent one patient from progressing to high-grade dysplasia or cancer. These data are in agreement with data from a prospective randomized study on the use of RFA for patients with a confirmed diagnosis of LGD. Most societies therefore consider a confirmed histologic diagnosis of LGD a justified indication for prophylactic ablation with RFA.

However, this does not imply that all patients with LGD should be ablated. First, only patients in whom the histologic diagnosis of LGD is confirmed by an expert BE pathologist should be considered for RFA. In approximately 75% of patients, the LGD diagnosis will be downstaged to nondysplastic BE upon expert review. Second, the lessons learned from the Kroep study also apply here: For an elderly LGD patient with or without significant comorbidity, the decision to proceed to RFA is different from the decision for patients with a longer life expectancy, especially if an intermediate solution – to continue endoscopic surveillance and proceed to endoscopic management in case neoplasia is diagnosed – is also considered.

Jacques Bergman, M.D., Ph.D., is professor of gastrointestinal endoscopy, director of endoscopy, at the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam. He received research support for clinical studies and consulted for Covidien/Medtronic GI solutions.

These two studies highlight two different hot topics in the management of patients with a Barrett’s esophagus. The first is the low rate of neoplastic progression in patients undergoing surveillance for nondysplastic BE. The second relates to the management of patients with low-grade dysplasia (LG

|

| Dr. Jacques Bergman |

Population-based BE surveillance studies have shown lower progression rates than have prospective surveillance studies. The biggest difference between these two is that not all patients in population-based studies actually undergo subsequent surveillance endoscopies and/or surveillance is carried out less rigorously than in prospective surveillance studies. Patients who have undergone a baseline endoscopy showing no neoplasia first need to develop early neoplasia (which is generally asymptomatic) that then needs to progress to a symptomatic stage before they are diagnosed. During this interval they may die from other causes or may be lost to follow-up. Patients in strict surveillance programs will be diagnosed at an earlier stage and at a higher rate. This is especially true in the first years of follow-up, when the initial screening endoscopy has its largest effect. Over time, the difference then fades away as suggested by the 9% progression rate of both types of studies at 20 years of follow-up. Both perspectives are relevant for patients. For elderly patients with significant comorbidity, the 5-year data from population-based studies reassure them not to undergo surveillance endoscopies because even when an early cancer develops it is unlikely to bear any clinical relevance, whereas for patients with a long life expectancy, the 9% cancer risk at 20 years and the dismal prognosis of a symptomatic Barrett’s cancer may be strong arguments for participating in a surveillance program.

For patients with LGD, the situation is different: The rate of progression is much higher than that reported for nondysplastic BE, and with radiofrequency ablation (RFA), an effective and safe tool is at hand to significantly reduce this rate of neoplastic progression. Small et al. reported that only three patients need to be treated with RFA to prevent one patient from progressing to high-grade dysplasia or cancer. These data are in agreement with data from a prospective randomized study on the use of RFA for patients with a confirmed diagnosis of LGD. Most societies therefore consider a confirmed histologic diagnosis of LGD a justified indication for prophylactic ablation with RFA.