User login

ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial: Analysis shows improved TWiST with niraparib

HONOLULU – Patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who were treated with niraparib maintenance therapy experienced more time without symptoms or toxicities (TWiST) than did controls, according to an analysis of data from the pivotal phase 3 ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial.

The mean 20-year TWiST benefit – defined in the current analysis as progression-free survival (PFS) without toxicity due to grade 2 or greater nausea, vomiting, or fatigue – was fourfold greater among women who were carriers of the 138 germline BRCA mutation (gBRCAmut) and received treatment with the poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) 1/2 inhibitor than among the 65 similar women who received placebo. The TWiST benefit was about twofold greater among the 234 non-gBRCAmut carriers treated with niraparib than among the 116 who received placebo, Ursula A. Matulonis, MD, reported at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

The 10- and 5-year estimated mean improvement in TWiST in the groups also showed “very proportional effects that are similar to the 20-year data,” said Dr. Matulonis, chief of the division of gynecologic oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

TWiSt is an “established methodology that partitions PFS ... based on time with toxicity and time without progression or toxicity." Mean TWiST is calculated as mean PFS minus mean toxicity, she explained.

In the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA study, women with recurrent ovarian cancer who received niraparib for maintenance after platinum-based therapy had significantly longer PFS, compared with patients who received placebo (21.0 vs. 5.5 months in gBRCAmut patients and 9.3 vs. 3.9 months in the non-gBRCAmut patients, respectively), she said (N Engl J Med 2016;75:2154-2164).

Quality of life (QOL) remained stable throughout niraparib treatment, according to another analysis of data from the trial published in 2018. (Lancet Oncology. Aug 1 2018;19[8]:1117-25).

The current analysis looked more closely at QOL by estimating mean TWiST in the treatment vs. control groups, she explained.

“Survival curves were used to extrapolate PFS ... over 20 years for both the gBRCAmut and non-gBRCAmut cohorts. The 20-year period was based on ovarian cancer clinical expert opinion and the biologic plausibility that patients could be on PARP inhibitors for a long period of time,” she said.

Time of toxicity was estimated based on the number of days patients experienced toxic effects due to grade 2 or higher nausea, vomiting, or fatigue during the NOVA trial.

The PFS benefit in treated vs. control subjects, respectively, was 3.23 years and 1.33 years in the gBRCAmut and non-gBRCAmut cohorts, and the mean toxicity time was 0.28 years and 0.10 years, for a mean TWiST benefit of 2.95 and 1.34 years, respectively.

“This TWiST benefit means that patients treated with niraparib experienced more progression-free time without symptoms or toxicities due to nausea, vomiting, or fatigue, compared with patients receiving placebo,” she concluded.

Dr. Matulonis is a consultant for 2X Oncology, Merck, Mersana, Fujifilm, Immunogen, and Geneos.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Matulonis U et al., SGO 2019: Abstract 1.

HONOLULU – Patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who were treated with niraparib maintenance therapy experienced more time without symptoms or toxicities (TWiST) than did controls, according to an analysis of data from the pivotal phase 3 ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial.

The mean 20-year TWiST benefit – defined in the current analysis as progression-free survival (PFS) without toxicity due to grade 2 or greater nausea, vomiting, or fatigue – was fourfold greater among women who were carriers of the 138 germline BRCA mutation (gBRCAmut) and received treatment with the poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) 1/2 inhibitor than among the 65 similar women who received placebo. The TWiST benefit was about twofold greater among the 234 non-gBRCAmut carriers treated with niraparib than among the 116 who received placebo, Ursula A. Matulonis, MD, reported at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

The 10- and 5-year estimated mean improvement in TWiST in the groups also showed “very proportional effects that are similar to the 20-year data,” said Dr. Matulonis, chief of the division of gynecologic oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

TWiSt is an “established methodology that partitions PFS ... based on time with toxicity and time without progression or toxicity." Mean TWiST is calculated as mean PFS minus mean toxicity, she explained.

In the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA study, women with recurrent ovarian cancer who received niraparib for maintenance after platinum-based therapy had significantly longer PFS, compared with patients who received placebo (21.0 vs. 5.5 months in gBRCAmut patients and 9.3 vs. 3.9 months in the non-gBRCAmut patients, respectively), she said (N Engl J Med 2016;75:2154-2164).

Quality of life (QOL) remained stable throughout niraparib treatment, according to another analysis of data from the trial published in 2018. (Lancet Oncology. Aug 1 2018;19[8]:1117-25).

The current analysis looked more closely at QOL by estimating mean TWiST in the treatment vs. control groups, she explained.

“Survival curves were used to extrapolate PFS ... over 20 years for both the gBRCAmut and non-gBRCAmut cohorts. The 20-year period was based on ovarian cancer clinical expert opinion and the biologic plausibility that patients could be on PARP inhibitors for a long period of time,” she said.

Time of toxicity was estimated based on the number of days patients experienced toxic effects due to grade 2 or higher nausea, vomiting, or fatigue during the NOVA trial.

The PFS benefit in treated vs. control subjects, respectively, was 3.23 years and 1.33 years in the gBRCAmut and non-gBRCAmut cohorts, and the mean toxicity time was 0.28 years and 0.10 years, for a mean TWiST benefit of 2.95 and 1.34 years, respectively.

“This TWiST benefit means that patients treated with niraparib experienced more progression-free time without symptoms or toxicities due to nausea, vomiting, or fatigue, compared with patients receiving placebo,” she concluded.

Dr. Matulonis is a consultant for 2X Oncology, Merck, Mersana, Fujifilm, Immunogen, and Geneos.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Matulonis U et al., SGO 2019: Abstract 1.

HONOLULU – Patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who were treated with niraparib maintenance therapy experienced more time without symptoms or toxicities (TWiST) than did controls, according to an analysis of data from the pivotal phase 3 ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial.

The mean 20-year TWiST benefit – defined in the current analysis as progression-free survival (PFS) without toxicity due to grade 2 or greater nausea, vomiting, or fatigue – was fourfold greater among women who were carriers of the 138 germline BRCA mutation (gBRCAmut) and received treatment with the poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) 1/2 inhibitor than among the 65 similar women who received placebo. The TWiST benefit was about twofold greater among the 234 non-gBRCAmut carriers treated with niraparib than among the 116 who received placebo, Ursula A. Matulonis, MD, reported at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

The 10- and 5-year estimated mean improvement in TWiST in the groups also showed “very proportional effects that are similar to the 20-year data,” said Dr. Matulonis, chief of the division of gynecologic oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

TWiSt is an “established methodology that partitions PFS ... based on time with toxicity and time without progression or toxicity." Mean TWiST is calculated as mean PFS minus mean toxicity, she explained.

In the ENGOT-OV16/NOVA study, women with recurrent ovarian cancer who received niraparib for maintenance after platinum-based therapy had significantly longer PFS, compared with patients who received placebo (21.0 vs. 5.5 months in gBRCAmut patients and 9.3 vs. 3.9 months in the non-gBRCAmut patients, respectively), she said (N Engl J Med 2016;75:2154-2164).

Quality of life (QOL) remained stable throughout niraparib treatment, according to another analysis of data from the trial published in 2018. (Lancet Oncology. Aug 1 2018;19[8]:1117-25).

The current analysis looked more closely at QOL by estimating mean TWiST in the treatment vs. control groups, she explained.

“Survival curves were used to extrapolate PFS ... over 20 years for both the gBRCAmut and non-gBRCAmut cohorts. The 20-year period was based on ovarian cancer clinical expert opinion and the biologic plausibility that patients could be on PARP inhibitors for a long period of time,” she said.

Time of toxicity was estimated based on the number of days patients experienced toxic effects due to grade 2 or higher nausea, vomiting, or fatigue during the NOVA trial.

The PFS benefit in treated vs. control subjects, respectively, was 3.23 years and 1.33 years in the gBRCAmut and non-gBRCAmut cohorts, and the mean toxicity time was 0.28 years and 0.10 years, for a mean TWiST benefit of 2.95 and 1.34 years, respectively.

“This TWiST benefit means that patients treated with niraparib experienced more progression-free time without symptoms or toxicities due to nausea, vomiting, or fatigue, compared with patients receiving placebo,” she concluded.

Dr. Matulonis is a consultant for 2X Oncology, Merck, Mersana, Fujifilm, Immunogen, and Geneos.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Matulonis U et al., SGO 2019: Abstract 1.

REPORTING FROM SGO 2019

Financial assistance programs may speed treatment for cervical cancer

HONOLULU – Financial assistance programs may help lower-income cervical cancer patients complete treatment in a timely manner, according to research presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

In a retrospective study, lower-income patients who used financial assistance programs were able to complete treatment for cervical cancer in a similar timeframe as higher-income patients.

Lower-income patients who registered for disability benefits saw a significant improvement in time to treatment completion.

Additionally, there was a trend toward improved time to treatment completion among lower-income patients who registered for federally funded breast and cervical cancer treatment.

“Identification of patients who qualify for disability and/or breast/cervical cancer Medicaid, and providing assistance for registration in these programs may help them complete therapy in a more appropriate timeframe,” said study investigator Jessica Gillen, MD, of The University of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City.

Dr. Gillen and her colleagues conducted this single-center, retrospective study of patients with squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous cancer of the cervix.

The investigators identified 116 evaluable patients who received chemoradiation from January 1, 2015, to July 31, 2018. Most of these 106 patients completed treatment in 63 days or less.

The patients’ median household income was $45,782 (range, $19,771–$96,222). The investigators defined “high-income” patients as those whose household incomes were at or above the median, and “low-income” patients as those with incomes below the median.

On average, the patients used 1.24 assistance programs, which included financial assistance (primarily help with clinic visit copays), assistance with medication costs, disability benefits, Medicaid, access to emergency funds, low-cost or free lodging, and transportation.

Dr. Gillen noted that 10% of low-income patients did not use any financial assistance programs.

She and her colleagues found that low-income patients who used assistance programs completed treatment in a similar timeframe as the high-income patients. The median time to treatment completion was 56.5 days and 50 days, respectively.

Registering for disability benefits was significantly associated with improved time to treatment completion (P less than .001).

There were no other significant associations between financial assistance programs and time to treatment completion. However, there was a trend toward improved time to treatment completion among patients who registered for federally funded breast and cervical cancer Medicaid (P = .06).

“[I]t was encouraging to see that enrollment in federally and state-funded programs makes a difference in patients’ ability to complete treatment,” Dr. Gillen said.

She and her colleagues said these data suggest financial assistance programs may help cervical cancer patients overcome barriers to care. Dr. Gillen had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillen J et al. SGO 2019. Abstract 9.

HONOLULU – Financial assistance programs may help lower-income cervical cancer patients complete treatment in a timely manner, according to research presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

In a retrospective study, lower-income patients who used financial assistance programs were able to complete treatment for cervical cancer in a similar timeframe as higher-income patients.

Lower-income patients who registered for disability benefits saw a significant improvement in time to treatment completion.

Additionally, there was a trend toward improved time to treatment completion among lower-income patients who registered for federally funded breast and cervical cancer treatment.

“Identification of patients who qualify for disability and/or breast/cervical cancer Medicaid, and providing assistance for registration in these programs may help them complete therapy in a more appropriate timeframe,” said study investigator Jessica Gillen, MD, of The University of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City.

Dr. Gillen and her colleagues conducted this single-center, retrospective study of patients with squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous cancer of the cervix.

The investigators identified 116 evaluable patients who received chemoradiation from January 1, 2015, to July 31, 2018. Most of these 106 patients completed treatment in 63 days or less.

The patients’ median household income was $45,782 (range, $19,771–$96,222). The investigators defined “high-income” patients as those whose household incomes were at or above the median, and “low-income” patients as those with incomes below the median.

On average, the patients used 1.24 assistance programs, which included financial assistance (primarily help with clinic visit copays), assistance with medication costs, disability benefits, Medicaid, access to emergency funds, low-cost or free lodging, and transportation.

Dr. Gillen noted that 10% of low-income patients did not use any financial assistance programs.

She and her colleagues found that low-income patients who used assistance programs completed treatment in a similar timeframe as the high-income patients. The median time to treatment completion was 56.5 days and 50 days, respectively.

Registering for disability benefits was significantly associated with improved time to treatment completion (P less than .001).

There were no other significant associations between financial assistance programs and time to treatment completion. However, there was a trend toward improved time to treatment completion among patients who registered for federally funded breast and cervical cancer Medicaid (P = .06).

“[I]t was encouraging to see that enrollment in federally and state-funded programs makes a difference in patients’ ability to complete treatment,” Dr. Gillen said.

She and her colleagues said these data suggest financial assistance programs may help cervical cancer patients overcome barriers to care. Dr. Gillen had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillen J et al. SGO 2019. Abstract 9.

HONOLULU – Financial assistance programs may help lower-income cervical cancer patients complete treatment in a timely manner, according to research presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

In a retrospective study, lower-income patients who used financial assistance programs were able to complete treatment for cervical cancer in a similar timeframe as higher-income patients.

Lower-income patients who registered for disability benefits saw a significant improvement in time to treatment completion.

Additionally, there was a trend toward improved time to treatment completion among lower-income patients who registered for federally funded breast and cervical cancer treatment.

“Identification of patients who qualify for disability and/or breast/cervical cancer Medicaid, and providing assistance for registration in these programs may help them complete therapy in a more appropriate timeframe,” said study investigator Jessica Gillen, MD, of The University of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City.

Dr. Gillen and her colleagues conducted this single-center, retrospective study of patients with squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous cancer of the cervix.

The investigators identified 116 evaluable patients who received chemoradiation from January 1, 2015, to July 31, 2018. Most of these 106 patients completed treatment in 63 days or less.

The patients’ median household income was $45,782 (range, $19,771–$96,222). The investigators defined “high-income” patients as those whose household incomes were at or above the median, and “low-income” patients as those with incomes below the median.

On average, the patients used 1.24 assistance programs, which included financial assistance (primarily help with clinic visit copays), assistance with medication costs, disability benefits, Medicaid, access to emergency funds, low-cost or free lodging, and transportation.

Dr. Gillen noted that 10% of low-income patients did not use any financial assistance programs.

She and her colleagues found that low-income patients who used assistance programs completed treatment in a similar timeframe as the high-income patients. The median time to treatment completion was 56.5 days and 50 days, respectively.

Registering for disability benefits was significantly associated with improved time to treatment completion (P less than .001).

There were no other significant associations between financial assistance programs and time to treatment completion. However, there was a trend toward improved time to treatment completion among patients who registered for federally funded breast and cervical cancer Medicaid (P = .06).

“[I]t was encouraging to see that enrollment in federally and state-funded programs makes a difference in patients’ ability to complete treatment,” Dr. Gillen said.

She and her colleagues said these data suggest financial assistance programs may help cervical cancer patients overcome barriers to care. Dr. Gillen had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillen J et al. SGO 2019. Abstract 9.

REPORTING FROM SGO 2019

Brachytherapy proves beneficial regardless of treatment duration

, according to a retrospective study.

Researchers found that patients who received brachytherapy in addition to chemotherapy and external beam radiation therapy had better overall survival than patients who received chemoradiation alone.

Although the best overall survival was observed in patients who received brachytherapy within the recommended 8 weeks, patients who received brachytherapy outside that timeframe also had better overall survival than patients treated with chemoradiation alone.

Travis-Riley K. Korenaga, MD, of University of California, San Francisco, presented these findings at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

To examine the use of brachytherapy, Dr. Korenaga and his colleagues analyzed patients from the U.S. National Cancer Database who had stage II-IVA cervical cancer and were diagnosed between 2004 and 2015.

The researchers identified 18,592 patients who received at least 4,500 cGy of external beam radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy as their primary treatment. In this group, there were 17,150 patients who had data on brachytherapy use and time to treatment completion.

A majority of patients (n = 13,642) received brachytherapy, and roughly half of those (n = 6,871) received it within the recommended 8 weeks.

“This is a pretty low rate of adherence to standard of care; 36.9% of women receive brachytherapy and complete it within that 8-week timeframe,” Dr. Korenaga said. “And that 36.9% of women do have a superior overall survival that blows everything else out of the water.”

The median overall survival was:

- 113.7 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 103.3-121.3) in patients who received brachytherapy within 8 weeks

- 75.7 months (95% CI, 69.7-82.4) in those who received brachytherapy for more than 8 weeks

- 58.5 months (95% CI, 48.3-74.2) in patients who received only chemoradiation within 8 weeks

- 46.2 months (95% CI, 39.8-56.4) in those who received only chemoradiation for more than 8 weeks.

“Getting some type of brachytherapy, no matter whether it’s within 8 weeks or beyond 8 weeks, is still associated with an improved overall survival,” Dr. Korenaga noted.

He and his colleagues also identified factors that were significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of receiving brachytherapy within 8 weeks, including:

- Having stage III/IVA disease vs. stage II disease (P less than .0001)

- Being non-Hispanic black vs. non-Hispanic white (P less than .001)

- Having an annual income below $38,000 vs. $63,000 or higher (P less than .0001)

- Having public vs. private insurance (P less than .0001)

- Living 10 to 60 miles (P = .01) or more than 100 miles (P less than .001) from the treatment facility vs. less than 10 miles

- Being treated at a facility with a community cancer program (P = .02) or a comprehensive community cancer program (P less than .0001) vs. an academic research program.

Dr. Korenaga said these results highlight the fact that more work needs to be done to increase the use of brachytherapy in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer.

He and his colleagues have suggested a few measures that might help, including early referrals for brachytherapy, connecting patients with care navigators, and developing centers of excellence for brachytherapy.

Dr. Korenaga had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Korenaga TRK et al. SGO 2019. Abstract 10.

, according to a retrospective study.

Researchers found that patients who received brachytherapy in addition to chemotherapy and external beam radiation therapy had better overall survival than patients who received chemoradiation alone.

Although the best overall survival was observed in patients who received brachytherapy within the recommended 8 weeks, patients who received brachytherapy outside that timeframe also had better overall survival than patients treated with chemoradiation alone.

Travis-Riley K. Korenaga, MD, of University of California, San Francisco, presented these findings at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

To examine the use of brachytherapy, Dr. Korenaga and his colleagues analyzed patients from the U.S. National Cancer Database who had stage II-IVA cervical cancer and were diagnosed between 2004 and 2015.

The researchers identified 18,592 patients who received at least 4,500 cGy of external beam radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy as their primary treatment. In this group, there were 17,150 patients who had data on brachytherapy use and time to treatment completion.

A majority of patients (n = 13,642) received brachytherapy, and roughly half of those (n = 6,871) received it within the recommended 8 weeks.

“This is a pretty low rate of adherence to standard of care; 36.9% of women receive brachytherapy and complete it within that 8-week timeframe,” Dr. Korenaga said. “And that 36.9% of women do have a superior overall survival that blows everything else out of the water.”

The median overall survival was:

- 113.7 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 103.3-121.3) in patients who received brachytherapy within 8 weeks

- 75.7 months (95% CI, 69.7-82.4) in those who received brachytherapy for more than 8 weeks

- 58.5 months (95% CI, 48.3-74.2) in patients who received only chemoradiation within 8 weeks

- 46.2 months (95% CI, 39.8-56.4) in those who received only chemoradiation for more than 8 weeks.

“Getting some type of brachytherapy, no matter whether it’s within 8 weeks or beyond 8 weeks, is still associated with an improved overall survival,” Dr. Korenaga noted.

He and his colleagues also identified factors that were significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of receiving brachytherapy within 8 weeks, including:

- Having stage III/IVA disease vs. stage II disease (P less than .0001)

- Being non-Hispanic black vs. non-Hispanic white (P less than .001)

- Having an annual income below $38,000 vs. $63,000 or higher (P less than .0001)

- Having public vs. private insurance (P less than .0001)

- Living 10 to 60 miles (P = .01) or more than 100 miles (P less than .001) from the treatment facility vs. less than 10 miles

- Being treated at a facility with a community cancer program (P = .02) or a comprehensive community cancer program (P less than .0001) vs. an academic research program.

Dr. Korenaga said these results highlight the fact that more work needs to be done to increase the use of brachytherapy in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer.

He and his colleagues have suggested a few measures that might help, including early referrals for brachytherapy, connecting patients with care navigators, and developing centers of excellence for brachytherapy.

Dr. Korenaga had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Korenaga TRK et al. SGO 2019. Abstract 10.

, according to a retrospective study.

Researchers found that patients who received brachytherapy in addition to chemotherapy and external beam radiation therapy had better overall survival than patients who received chemoradiation alone.

Although the best overall survival was observed in patients who received brachytherapy within the recommended 8 weeks, patients who received brachytherapy outside that timeframe also had better overall survival than patients treated with chemoradiation alone.

Travis-Riley K. Korenaga, MD, of University of California, San Francisco, presented these findings at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

To examine the use of brachytherapy, Dr. Korenaga and his colleagues analyzed patients from the U.S. National Cancer Database who had stage II-IVA cervical cancer and were diagnosed between 2004 and 2015.

The researchers identified 18,592 patients who received at least 4,500 cGy of external beam radiation therapy and concurrent chemotherapy as their primary treatment. In this group, there were 17,150 patients who had data on brachytherapy use and time to treatment completion.

A majority of patients (n = 13,642) received brachytherapy, and roughly half of those (n = 6,871) received it within the recommended 8 weeks.

“This is a pretty low rate of adherence to standard of care; 36.9% of women receive brachytherapy and complete it within that 8-week timeframe,” Dr. Korenaga said. “And that 36.9% of women do have a superior overall survival that blows everything else out of the water.”

The median overall survival was:

- 113.7 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 103.3-121.3) in patients who received brachytherapy within 8 weeks

- 75.7 months (95% CI, 69.7-82.4) in those who received brachytherapy for more than 8 weeks

- 58.5 months (95% CI, 48.3-74.2) in patients who received only chemoradiation within 8 weeks

- 46.2 months (95% CI, 39.8-56.4) in those who received only chemoradiation for more than 8 weeks.

“Getting some type of brachytherapy, no matter whether it’s within 8 weeks or beyond 8 weeks, is still associated with an improved overall survival,” Dr. Korenaga noted.

He and his colleagues also identified factors that were significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of receiving brachytherapy within 8 weeks, including:

- Having stage III/IVA disease vs. stage II disease (P less than .0001)

- Being non-Hispanic black vs. non-Hispanic white (P less than .001)

- Having an annual income below $38,000 vs. $63,000 or higher (P less than .0001)

- Having public vs. private insurance (P less than .0001)

- Living 10 to 60 miles (P = .01) or more than 100 miles (P less than .001) from the treatment facility vs. less than 10 miles

- Being treated at a facility with a community cancer program (P = .02) or a comprehensive community cancer program (P less than .0001) vs. an academic research program.

Dr. Korenaga said these results highlight the fact that more work needs to be done to increase the use of brachytherapy in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer.

He and his colleagues have suggested a few measures that might help, including early referrals for brachytherapy, connecting patients with care navigators, and developing centers of excellence for brachytherapy.

Dr. Korenaga had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Korenaga TRK et al. SGO 2019. Abstract 10.

REPORTING FROM SGO 2019

Ovarian cancer survivors carry burden of severe long-term fatigue

Women who have survived epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) more often report severe long-term fatigue than healthy women, according to a case-control study involving more than 600 individuals.

Ovarian cancer survivors had a higher rate of sleep disturbance, neuropathy, and depression, reported lead author Florence Joly, MD, of Centre François Baclesse in Caen, France, and her colleagues. These factors likely contribute to severe long-term fatigue; a condition that has been minimally researched in EOC survivors.

“Long-term fatigue has been described as one of the most common and distressing adverse effects of cancer and its treatment,” the investigators wrote in Annals of Oncology. However, “Little is known about the prevalence of long-term fatigue in EOC survivors several years after treatment in comparison with age-matched healthy women.”

The study involved 318 EOC survivors who had not relapsed for at least 3 years, and 318 age-matched, healthy women. Survivors were 63 years old, on average, and split almost evenly between cases of early and advanced disease (50% stage I/II vs. 48% stage III/IV). Almost all patients had received platinum/taxane chemotherapy (99%). Average follow-up was 6 years.

Participants self-reported through questionnaires about physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire), sleep disturbance ( Insomnia Severity Index), anxiety/depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), neuropathy (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Taxane Neurotoxicity [FACT-Ntx]), quality of life ( Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General/Ovarian), and fatigue (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F). Severe long-term fatigue was defined as a FACIT-F score of less than 37. Analysis was performed to find rates of severe long-term fatigue and contributing factors.

Although sociodemographic measures and global quality of life were similar between groups, 26% of EOC survivors reported severe long-term fatigue, compared with 13% of healthy women (P = .0004). Multivariable analysis revealed that three main factors contributed to this trend; worse neuropathy scores (FACT-Ntx 35 vs. 39), higher rates of depression (22% vs. 13%), and lower sleep quality (63% vs. 47%).

“These results highlight the need for continuous screening of sleep disturbance and depression as soon as the diagnosis of EOC is made, and for sleep disturbance interventions in EOC survivors,” the investigators wrote. “As pharmacological treatment seems to have limited efficacy, behavioral interventions should be offered to improve sleep quality and/or depressive symptoms.”

“Fewer than 20% of our EOC survivors and controls exercised regularly, a finding consistent with a recent study conducted in long-term EOC survivors,” the investigators noted. “Personalized clinical exercise programs were effective in improving fatigue and depression in a heterogeneous population of cancer survivors, so they should be promoted in EOC survivors [too].”

The study was funded by Fondation de France. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, Sanofi, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Joly F et al. Ann Onc. 2019 Mar 9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz074.

Women who have survived epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) more often report severe long-term fatigue than healthy women, according to a case-control study involving more than 600 individuals.

Ovarian cancer survivors had a higher rate of sleep disturbance, neuropathy, and depression, reported lead author Florence Joly, MD, of Centre François Baclesse in Caen, France, and her colleagues. These factors likely contribute to severe long-term fatigue; a condition that has been minimally researched in EOC survivors.

“Long-term fatigue has been described as one of the most common and distressing adverse effects of cancer and its treatment,” the investigators wrote in Annals of Oncology. However, “Little is known about the prevalence of long-term fatigue in EOC survivors several years after treatment in comparison with age-matched healthy women.”

The study involved 318 EOC survivors who had not relapsed for at least 3 years, and 318 age-matched, healthy women. Survivors were 63 years old, on average, and split almost evenly between cases of early and advanced disease (50% stage I/II vs. 48% stage III/IV). Almost all patients had received platinum/taxane chemotherapy (99%). Average follow-up was 6 years.

Participants self-reported through questionnaires about physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire), sleep disturbance ( Insomnia Severity Index), anxiety/depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), neuropathy (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Taxane Neurotoxicity [FACT-Ntx]), quality of life ( Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General/Ovarian), and fatigue (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F). Severe long-term fatigue was defined as a FACIT-F score of less than 37. Analysis was performed to find rates of severe long-term fatigue and contributing factors.

Although sociodemographic measures and global quality of life were similar between groups, 26% of EOC survivors reported severe long-term fatigue, compared with 13% of healthy women (P = .0004). Multivariable analysis revealed that three main factors contributed to this trend; worse neuropathy scores (FACT-Ntx 35 vs. 39), higher rates of depression (22% vs. 13%), and lower sleep quality (63% vs. 47%).

“These results highlight the need for continuous screening of sleep disturbance and depression as soon as the diagnosis of EOC is made, and for sleep disturbance interventions in EOC survivors,” the investigators wrote. “As pharmacological treatment seems to have limited efficacy, behavioral interventions should be offered to improve sleep quality and/or depressive symptoms.”

“Fewer than 20% of our EOC survivors and controls exercised regularly, a finding consistent with a recent study conducted in long-term EOC survivors,” the investigators noted. “Personalized clinical exercise programs were effective in improving fatigue and depression in a heterogeneous population of cancer survivors, so they should be promoted in EOC survivors [too].”

The study was funded by Fondation de France. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, Sanofi, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Joly F et al. Ann Onc. 2019 Mar 9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz074.

Women who have survived epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) more often report severe long-term fatigue than healthy women, according to a case-control study involving more than 600 individuals.

Ovarian cancer survivors had a higher rate of sleep disturbance, neuropathy, and depression, reported lead author Florence Joly, MD, of Centre François Baclesse in Caen, France, and her colleagues. These factors likely contribute to severe long-term fatigue; a condition that has been minimally researched in EOC survivors.

“Long-term fatigue has been described as one of the most common and distressing adverse effects of cancer and its treatment,” the investigators wrote in Annals of Oncology. However, “Little is known about the prevalence of long-term fatigue in EOC survivors several years after treatment in comparison with age-matched healthy women.”

The study involved 318 EOC survivors who had not relapsed for at least 3 years, and 318 age-matched, healthy women. Survivors were 63 years old, on average, and split almost evenly between cases of early and advanced disease (50% stage I/II vs. 48% stage III/IV). Almost all patients had received platinum/taxane chemotherapy (99%). Average follow-up was 6 years.

Participants self-reported through questionnaires about physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire), sleep disturbance ( Insomnia Severity Index), anxiety/depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), neuropathy (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Taxane Neurotoxicity [FACT-Ntx]), quality of life ( Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General/Ovarian), and fatigue (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F). Severe long-term fatigue was defined as a FACIT-F score of less than 37. Analysis was performed to find rates of severe long-term fatigue and contributing factors.

Although sociodemographic measures and global quality of life were similar between groups, 26% of EOC survivors reported severe long-term fatigue, compared with 13% of healthy women (P = .0004). Multivariable analysis revealed that three main factors contributed to this trend; worse neuropathy scores (FACT-Ntx 35 vs. 39), higher rates of depression (22% vs. 13%), and lower sleep quality (63% vs. 47%).

“These results highlight the need for continuous screening of sleep disturbance and depression as soon as the diagnosis of EOC is made, and for sleep disturbance interventions in EOC survivors,” the investigators wrote. “As pharmacological treatment seems to have limited efficacy, behavioral interventions should be offered to improve sleep quality and/or depressive symptoms.”

“Fewer than 20% of our EOC survivors and controls exercised regularly, a finding consistent with a recent study conducted in long-term EOC survivors,” the investigators noted. “Personalized clinical exercise programs were effective in improving fatigue and depression in a heterogeneous population of cancer survivors, so they should be promoted in EOC survivors [too].”

The study was funded by Fondation de France. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Janssen, Sanofi, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Joly F et al. Ann Onc. 2019 Mar 9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz074.

FROM ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY

2019 Update on gynecologic cancer

Of the major developments in 2018 that changed practice in gynecologic oncology, we highlight 3 here.

First, a trial on the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for patients with ovarian cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated an overall survival benefit of 12 months for patients treated with HIPEC. Second, a trial on polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors as maintenance therapy after adjuvant chemotherapy showed that women with a BRCA mutation had a progression-free survival benefit of nearly 3 years. Third, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial revealed a significant decrease in survival in women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with those who had the traditional open approach. In addition, a retrospective study that analyzed information from large cancer databases showed that national survival rates decreased for patients with cervical cancer as the use of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy rose.

In this Update, we summarize the major findings of these trials, provide background on treatment strategies, and discuss how our practice as cancer specialists has changed in light of these studies' findings.

HIPEC improves overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer—by a lot

Van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230-240.

In the United States, women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer typically are treated with primary cytoreductive (debulking) surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy. The goal of cytoreductive surgery is the resection of all grossly visible tumor. While associated with favorable oncologic outcomes, cytoreductive surgery also is accompanied by significant morbidity, and surgery is not always feasible.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has emerged as an alternative treatment strategy to primary cytoreductive surgery. Women treated with NACT typically undergo 3 to 4 cycles of platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy, receive interval cytoreduction, and then are treated with an additional 3 to 4 cycles of chemotherapy postoperatively. Several large, randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that survival is similar for women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer treated with either primary cytoreduction or NACT.1,2 Importantly, perioperative morbidity is substantially lower with NACT and the rate of complete tumor resection is improved. Use of NACT for ovarian cancer has increased substantially in recent years.3

Rationale for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy has long been utilized in the treatment of ovarian cancer.4 Given that the abdomen is the most common site of metastatic spread for ovarian cancer, there is a strong rationale for direct infusion of chemotherapy into the abdominal cavity. Several early trials showed that adjuvant IP chemotherapy improves survival compared with intravenous chemotherapy alone.5,6 Yet complete adoption of IP chemotherapy has been limited by evidence of moderately increased toxicities, such as pain, infections, and bowel obstructions, as well as IP catheter complications.5,7

Heated IP chemotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer

More recently, interest has focused on HIPEC. In this approach, chemotherapy is heated to 42°C and administered into the abdominal cavity immediately after cytoreductive surgery; a temperature of 40°C to 41°C is maintained for total perfusion over a 90-minute period. The increased temperature induces apoptosis and protein degeneration, leading to greater penetration by the chemotherapy along peritoneal surfaces.8

For ovarian cancer, HIPEC has been explored in a number of small studies, predominately for women with recurrent disease.9 These studies demonstrated that HIPEC increased toxicities with gastrointestinal and renal complications but improved overall and disease-free survival.

HIPEC for primary treatment

Van Driel and colleagues explored the safety and efficacy of HIPEC for the primary treatment of ovarian cancer.10 In their multicenter trial, the authors sought to determine if there was a survival benefit with HIPEC in patients with stage III ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer treated with NACT. Eligible participants initially were treated with 3 cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Two-hundred forty-five patients who had a response or stable disease were then randomly assigned to undergo either interval cytoreductive surgery alone or surgery with HIPEC using cisplatin. Both groups received 3 additional cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel after surgery.

Results. Treatment with HIPEC was associated with a 3.5-month improvement in recurrence-free survival compared with surgery alone (14.2 vs 10.7 months) and a 12-month improvement in overall survival (45.7 vs 33.9 months). After a median follow-up of 4.7 years, 62% of patients in the surgery group and 50% of the patients in the HIPEC group had died.

Adverse events. Rates of grade 3 and 4 adverse events were similar for both treatment arms (25% in the surgery group vs 27% in the HIPEC plus surgery group), and there was no significant difference in hospital length of stay (8 vs 10 days, which included a mandatory 1-night stay in the intensive care unit for HIPEC-treated patients).

For carefully selected women with advanced ovarian cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, HIPEC at the time of interval cytoreductive surgery may improve survival by a year.

Continue to: PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer...

PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer, especially for women with a BRCA mutation

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest malignancy affecting women in the United States. While patients are likely to respond to their initial chemotherapy and surgery, there is a significant risk for cancer recurrence, from which the high mortality rates arise.

Maintenance therapy has considerable potential for preventing recurrences. Based on the results of a large Gynecologic Oncology Group study,11 in 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bevacizumab for use in combination with and following standard carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for women with advanced ovarian cancer. In the trial, maintenance therapy with 10 months of bevacizumab improved progression-free survival by 4 months; however, it did not improve overall survival, and adverse events included bowel perforations and hypertension.11 Alternative targets for maintenance therapy to prevent or minimize the risk of recurrence in women with ovarian cancer have been actively investigated.

PARP inhibitors work by damaging cancer cell DNA

PARP is a key enzyme that repairs DNA damage within cells. Drugs that inhibit PARP trap this enzyme at the site of single-strand breaks, disrupting single-strand repair and inducing double-strand breaks. Since the homologous recombination pathway used to repair double-strand DNA breaks does not function in BRCA-mutated tissues, PARP inhibitors ultimately induce targeted DNA damage and apoptosis in both germline and somatic BRCA mutation carriers.12

In the United States, 3 PARP inhibitors (olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib) are FDA approved as maintenance therapy for use in women with recurrent ovarian cancer that had responded completely or partially to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status. PARP inhibitors also have been approved for treatment of advanced ovarian cancer in BRCA mutation carriers who have received 3 or more lines of platinum-based chemotherapy. Because of their efficacy in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer, there is great interest in using PARP inhibitors earlier in the disease course.

Olaparib is effective in women with BRCA mutations

In an international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial, Moore and colleagues sought to determine the efficacy of the PARP inhibitor olaparib administered as maintenance therapy in women with germline or somatic BRCA mutations.13 Women were eligible if they had BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations with newly diagnosed advanced (stage III or IV) ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer and a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy after cytoreduction.

Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio, with 260 participants receiving twice daily olaparib and 131 receiving placebo.

Results. After 41 months of follow-up, the disease-free survival rate was 60% in the olaparib group, compared with 27% in the placebo arm. Progression-free survival was 36 months longer in the olaparib maintenance group than in the placebo group.

Adverse events. While 21% of women treated with olaparib experienced serious adverse events (compared with 12% in the placebo group), most were related to anemia. Acute myeloid leukemia occurred in 3 (1%) of the 260 patients receiving olaparib.

For women with deleterious BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations, administering PARP inhibitors as a maintenance therapy following primary treatment with the standard platinum-based chemotherapy improves progression-free survival by at least 3 years.

Continue to: Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

For various procedures, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is associated with decreased blood loss, shorter postoperative stay, and decreased postoperative complications and readmission rates. In oncology, MIS has demonstrated equivalent outcomes compared with open procedures for colorectal and endometrial cancers.14,15

Increasing use of MIS in cervical cancer

For patients with cervical cancer, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy has more favorable perioperative outcomes, less morbidity, and decreased costs than open radical hysterectomy.16-20 However, many of the studies used to justify these benefits were small, lacked adequate follow-up, and were not adequately powered to detect a true survival difference. Some trials compared contemporary MIS enrollees to historical open surgery controls, who may have had more advanced-stage disease and may have been treated with different adjuvant chemoradiation.

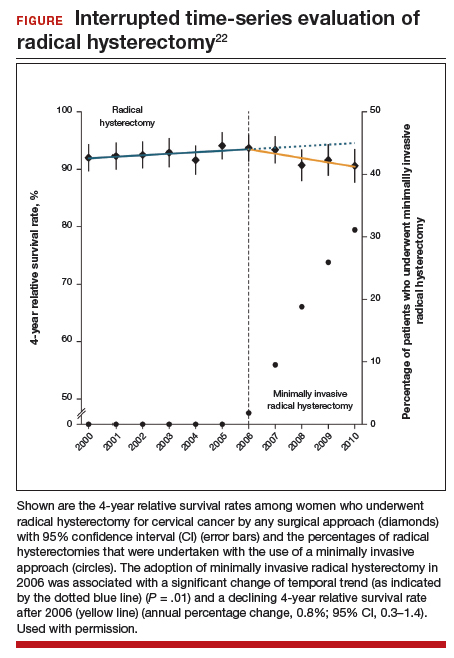

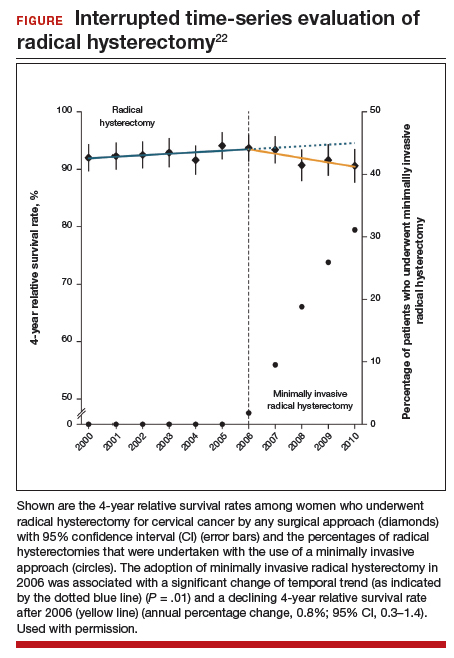

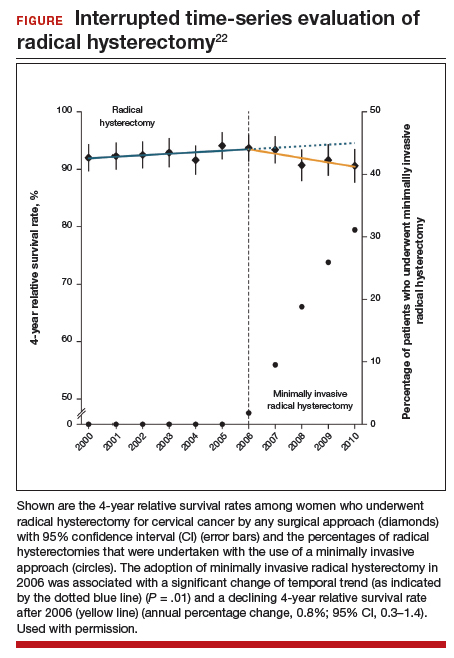

Despite these major limitations, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy became an acceptable—and often preferable—alternative to open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. This acceptance was written into National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines,21 and minimally invasive radical hysterectomy rapidly gained popularity, increasing from 1.8% in 2006 to 31% in 2010.22

Randomized trial revealed surprising findings

Ramirez and colleagues recently published the results of the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial, a randomized controlled trial that compared open with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy in women with stage IA1-IB1 cervical cancer.23 The study was designed as a noninferiority trial in which researchers set a threshold of -7.2% for how much worse the survival of MIS patients could be compared with open surgery before MIS could be declared an inferior treatment. A total of 631 patients were enrolled at 33 centers worldwide. After an interim analysis demonstrated a safety signal in the MIS radical hysterectomy cohort, the study was closed before completion of enrollment.

Overall, 91% of patients randomly assigned to treatment had stage IB1 tumors. At the time of analysis, nearly 60% of enrollees had survival data at 4.5 years to provide adequate power for full analysis.

Results. Disease-free survival (the time from randomization to recurrence or death from cervical cancer) was 86.0% in the MIS group and 96.5% in the open hysterectomy group. At 4.5 years, 27 MIS patients had recurrent disease, compared with 7 patients who underwent abdominal radical hysterectomy. There were 14 cancer-related deaths in the MIS group, compared with 2 in the open group.

Three-year disease-free survival was 91.2% in the MIS group versus 97.1% in the abdominal radical hysterectomy group (hazard ratio, 3.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-8.58) The overall 3-year survival was 93.8% in the MIS group, compared with 99.0% in the open group.23

Retrospective cohort study had similar results

Concurrent with publication of the LACC trial results, Melamed and colleagues published an observational study on the safety of MIS radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer.22 They used data from the National Cancer Database to examine 2,461 women with stage IA2-IB1 cervical cancer who underwent radical hysterectomy from 2010 to 2013. Approximately half of the women (49.8%) underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy.

Results. After a median follow-up of 45 months, the 4-year mortality rate was 9.1% among women who underwent MIS radical hysterectomy, compared with 5.3% for those who had an abdominal radical hysterectomy.

Using the complimentary Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry dataset, the authors examined population-level trends in use of MIS radical hysterectomy and survival. From 2000 to 2006, when MIS radical hysterectomy was rarely utilized, 4-year survival for cervical cancer was relatively stable. After adoption of MIS radical hysterectomy in 2006, 4-year relative survival declined by 0.8% annually for cervical cancer (FIGURE).22

Both a randomized controlled trial and a large observational study demonstrated decreased survival for women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy. Use of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy should be used with caution in women with early-stage cervical cancer.

- Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F, et al; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Gynaecological Cancer Group; NCIC Clinical Trials Group. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943-953.

- Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:249-257.

- Melamed A, Hinchcliff EM, Clemmer JT, et al. Trends in the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer in the United States. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:236-240.

- Markman M. Intraperitoneal antineoplastic drug delivery: rationale and results. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:277-283.

- Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS, et al. Phase III trial of standard-dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: an intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1001-1007.

- Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al; Gynecologic Oncology Group. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34-43.

- Alberts DS, Liu PY, Hannigan EV, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1950-1955.

- van de Vaart PJ, van der Vange N, Zoetmulder FA, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin with regional hyperthermia in advanced ovarian cancer: pharmacokinetics and cisplatin-DNA adduct formation in patients and ovarian cancer cell lines. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:148-154.

- Bakrin N, Cotte E, Golfier F, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for persistent and recurrent advanced ovarian carcinoma: a multicenter, prospective study of 246 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4052-4058.

- van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230-240.

- Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, et al; Gynecologic Oncology Group. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473-2483.

- Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917-921.

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

- Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:695-700.

- Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group, Nelson H, Sargent DJ, et al. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2050-2059.

- Lee EJ, Kang H, Kim DH. A comparative study of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with radical abdominal hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156:83-86.

- Malzoni M, Tinelli R, Cosentino F, et al. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy in patients with early cervical cancer: our experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1316-1323.

- Nam JH, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy in early-stage cervical cancer: long-term survival outcomes in a matched cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:903-911.

- Obermair A, Gebski V, Frumovitz M, et al. A phase III randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic or robotic radical hysterectomy with abdominal radical hysterectomy in patients with early stage cervical cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:584-588.

- Mendivil AA, Rettenmaier MA, Abaid LN, et al. Survival rate comparisons amongst cervical cancer patients treated with an open, robotic-assisted or laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: a five year experience. Surg Oncol. 2016;25:66-71.

- National Comprehensive Care Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: cervical cancer, version 1.2018. http://oncolife.com.ua/doc/nccn/Cervical_Cancer.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Of the major developments in 2018 that changed practice in gynecologic oncology, we highlight 3 here.

First, a trial on the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for patients with ovarian cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated an overall survival benefit of 12 months for patients treated with HIPEC. Second, a trial on polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors as maintenance therapy after adjuvant chemotherapy showed that women with a BRCA mutation had a progression-free survival benefit of nearly 3 years. Third, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial revealed a significant decrease in survival in women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with those who had the traditional open approach. In addition, a retrospective study that analyzed information from large cancer databases showed that national survival rates decreased for patients with cervical cancer as the use of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy rose.

In this Update, we summarize the major findings of these trials, provide background on treatment strategies, and discuss how our practice as cancer specialists has changed in light of these studies' findings.

HIPEC improves overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer—by a lot

Van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230-240.

In the United States, women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer typically are treated with primary cytoreductive (debulking) surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy. The goal of cytoreductive surgery is the resection of all grossly visible tumor. While associated with favorable oncologic outcomes, cytoreductive surgery also is accompanied by significant morbidity, and surgery is not always feasible.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has emerged as an alternative treatment strategy to primary cytoreductive surgery. Women treated with NACT typically undergo 3 to 4 cycles of platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy, receive interval cytoreduction, and then are treated with an additional 3 to 4 cycles of chemotherapy postoperatively. Several large, randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that survival is similar for women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer treated with either primary cytoreduction or NACT.1,2 Importantly, perioperative morbidity is substantially lower with NACT and the rate of complete tumor resection is improved. Use of NACT for ovarian cancer has increased substantially in recent years.3

Rationale for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy has long been utilized in the treatment of ovarian cancer.4 Given that the abdomen is the most common site of metastatic spread for ovarian cancer, there is a strong rationale for direct infusion of chemotherapy into the abdominal cavity. Several early trials showed that adjuvant IP chemotherapy improves survival compared with intravenous chemotherapy alone.5,6 Yet complete adoption of IP chemotherapy has been limited by evidence of moderately increased toxicities, such as pain, infections, and bowel obstructions, as well as IP catheter complications.5,7

Heated IP chemotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer

More recently, interest has focused on HIPEC. In this approach, chemotherapy is heated to 42°C and administered into the abdominal cavity immediately after cytoreductive surgery; a temperature of 40°C to 41°C is maintained for total perfusion over a 90-minute period. The increased temperature induces apoptosis and protein degeneration, leading to greater penetration by the chemotherapy along peritoneal surfaces.8

For ovarian cancer, HIPEC has been explored in a number of small studies, predominately for women with recurrent disease.9 These studies demonstrated that HIPEC increased toxicities with gastrointestinal and renal complications but improved overall and disease-free survival.

HIPEC for primary treatment

Van Driel and colleagues explored the safety and efficacy of HIPEC for the primary treatment of ovarian cancer.10 In their multicenter trial, the authors sought to determine if there was a survival benefit with HIPEC in patients with stage III ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer treated with NACT. Eligible participants initially were treated with 3 cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Two-hundred forty-five patients who had a response or stable disease were then randomly assigned to undergo either interval cytoreductive surgery alone or surgery with HIPEC using cisplatin. Both groups received 3 additional cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel after surgery.

Results. Treatment with HIPEC was associated with a 3.5-month improvement in recurrence-free survival compared with surgery alone (14.2 vs 10.7 months) and a 12-month improvement in overall survival (45.7 vs 33.9 months). After a median follow-up of 4.7 years, 62% of patients in the surgery group and 50% of the patients in the HIPEC group had died.

Adverse events. Rates of grade 3 and 4 adverse events were similar for both treatment arms (25% in the surgery group vs 27% in the HIPEC plus surgery group), and there was no significant difference in hospital length of stay (8 vs 10 days, which included a mandatory 1-night stay in the intensive care unit for HIPEC-treated patients).

For carefully selected women with advanced ovarian cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, HIPEC at the time of interval cytoreductive surgery may improve survival by a year.

Continue to: PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer...

PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer, especially for women with a BRCA mutation

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest malignancy affecting women in the United States. While patients are likely to respond to their initial chemotherapy and surgery, there is a significant risk for cancer recurrence, from which the high mortality rates arise.

Maintenance therapy has considerable potential for preventing recurrences. Based on the results of a large Gynecologic Oncology Group study,11 in 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bevacizumab for use in combination with and following standard carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for women with advanced ovarian cancer. In the trial, maintenance therapy with 10 months of bevacizumab improved progression-free survival by 4 months; however, it did not improve overall survival, and adverse events included bowel perforations and hypertension.11 Alternative targets for maintenance therapy to prevent or minimize the risk of recurrence in women with ovarian cancer have been actively investigated.

PARP inhibitors work by damaging cancer cell DNA

PARP is a key enzyme that repairs DNA damage within cells. Drugs that inhibit PARP trap this enzyme at the site of single-strand breaks, disrupting single-strand repair and inducing double-strand breaks. Since the homologous recombination pathway used to repair double-strand DNA breaks does not function in BRCA-mutated tissues, PARP inhibitors ultimately induce targeted DNA damage and apoptosis in both germline and somatic BRCA mutation carriers.12

In the United States, 3 PARP inhibitors (olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib) are FDA approved as maintenance therapy for use in women with recurrent ovarian cancer that had responded completely or partially to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status. PARP inhibitors also have been approved for treatment of advanced ovarian cancer in BRCA mutation carriers who have received 3 or more lines of platinum-based chemotherapy. Because of their efficacy in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer, there is great interest in using PARP inhibitors earlier in the disease course.

Olaparib is effective in women with BRCA mutations

In an international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial, Moore and colleagues sought to determine the efficacy of the PARP inhibitor olaparib administered as maintenance therapy in women with germline or somatic BRCA mutations.13 Women were eligible if they had BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations with newly diagnosed advanced (stage III or IV) ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer and a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy after cytoreduction.

Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio, with 260 participants receiving twice daily olaparib and 131 receiving placebo.

Results. After 41 months of follow-up, the disease-free survival rate was 60% in the olaparib group, compared with 27% in the placebo arm. Progression-free survival was 36 months longer in the olaparib maintenance group than in the placebo group.

Adverse events. While 21% of women treated with olaparib experienced serious adverse events (compared with 12% in the placebo group), most were related to anemia. Acute myeloid leukemia occurred in 3 (1%) of the 260 patients receiving olaparib.

For women with deleterious BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations, administering PARP inhibitors as a maintenance therapy following primary treatment with the standard platinum-based chemotherapy improves progression-free survival by at least 3 years.

Continue to: Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

For various procedures, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is associated with decreased blood loss, shorter postoperative stay, and decreased postoperative complications and readmission rates. In oncology, MIS has demonstrated equivalent outcomes compared with open procedures for colorectal and endometrial cancers.14,15

Increasing use of MIS in cervical cancer

For patients with cervical cancer, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy has more favorable perioperative outcomes, less morbidity, and decreased costs than open radical hysterectomy.16-20 However, many of the studies used to justify these benefits were small, lacked adequate follow-up, and were not adequately powered to detect a true survival difference. Some trials compared contemporary MIS enrollees to historical open surgery controls, who may have had more advanced-stage disease and may have been treated with different adjuvant chemoradiation.

Despite these major limitations, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy became an acceptable—and often preferable—alternative to open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. This acceptance was written into National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines,21 and minimally invasive radical hysterectomy rapidly gained popularity, increasing from 1.8% in 2006 to 31% in 2010.22

Randomized trial revealed surprising findings

Ramirez and colleagues recently published the results of the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial, a randomized controlled trial that compared open with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy in women with stage IA1-IB1 cervical cancer.23 The study was designed as a noninferiority trial in which researchers set a threshold of -7.2% for how much worse the survival of MIS patients could be compared with open surgery before MIS could be declared an inferior treatment. A total of 631 patients were enrolled at 33 centers worldwide. After an interim analysis demonstrated a safety signal in the MIS radical hysterectomy cohort, the study was closed before completion of enrollment.

Overall, 91% of patients randomly assigned to treatment had stage IB1 tumors. At the time of analysis, nearly 60% of enrollees had survival data at 4.5 years to provide adequate power for full analysis.

Results. Disease-free survival (the time from randomization to recurrence or death from cervical cancer) was 86.0% in the MIS group and 96.5% in the open hysterectomy group. At 4.5 years, 27 MIS patients had recurrent disease, compared with 7 patients who underwent abdominal radical hysterectomy. There were 14 cancer-related deaths in the MIS group, compared with 2 in the open group.

Three-year disease-free survival was 91.2% in the MIS group versus 97.1% in the abdominal radical hysterectomy group (hazard ratio, 3.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-8.58) The overall 3-year survival was 93.8% in the MIS group, compared with 99.0% in the open group.23

Retrospective cohort study had similar results

Concurrent with publication of the LACC trial results, Melamed and colleagues published an observational study on the safety of MIS radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer.22 They used data from the National Cancer Database to examine 2,461 women with stage IA2-IB1 cervical cancer who underwent radical hysterectomy from 2010 to 2013. Approximately half of the women (49.8%) underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy.

Results. After a median follow-up of 45 months, the 4-year mortality rate was 9.1% among women who underwent MIS radical hysterectomy, compared with 5.3% for those who had an abdominal radical hysterectomy.

Using the complimentary Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry dataset, the authors examined population-level trends in use of MIS radical hysterectomy and survival. From 2000 to 2006, when MIS radical hysterectomy was rarely utilized, 4-year survival for cervical cancer was relatively stable. After adoption of MIS radical hysterectomy in 2006, 4-year relative survival declined by 0.8% annually for cervical cancer (FIGURE).22

Both a randomized controlled trial and a large observational study demonstrated decreased survival for women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy. Use of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy should be used with caution in women with early-stage cervical cancer.

Of the major developments in 2018 that changed practice in gynecologic oncology, we highlight 3 here.

First, a trial on the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for patients with ovarian cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated an overall survival benefit of 12 months for patients treated with HIPEC. Second, a trial on polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors as maintenance therapy after adjuvant chemotherapy showed that women with a BRCA mutation had a progression-free survival benefit of nearly 3 years. Third, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial revealed a significant decrease in survival in women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with those who had the traditional open approach. In addition, a retrospective study that analyzed information from large cancer databases showed that national survival rates decreased for patients with cervical cancer as the use of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy rose.

In this Update, we summarize the major findings of these trials, provide background on treatment strategies, and discuss how our practice as cancer specialists has changed in light of these studies' findings.

HIPEC improves overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer—by a lot

Van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230-240.

In the United States, women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer typically are treated with primary cytoreductive (debulking) surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy. The goal of cytoreductive surgery is the resection of all grossly visible tumor. While associated with favorable oncologic outcomes, cytoreductive surgery also is accompanied by significant morbidity, and surgery is not always feasible.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has emerged as an alternative treatment strategy to primary cytoreductive surgery. Women treated with NACT typically undergo 3 to 4 cycles of platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy, receive interval cytoreduction, and then are treated with an additional 3 to 4 cycles of chemotherapy postoperatively. Several large, randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that survival is similar for women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer treated with either primary cytoreduction or NACT.1,2 Importantly, perioperative morbidity is substantially lower with NACT and the rate of complete tumor resection is improved. Use of NACT for ovarian cancer has increased substantially in recent years.3

Rationale for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy has long been utilized in the treatment of ovarian cancer.4 Given that the abdomen is the most common site of metastatic spread for ovarian cancer, there is a strong rationale for direct infusion of chemotherapy into the abdominal cavity. Several early trials showed that adjuvant IP chemotherapy improves survival compared with intravenous chemotherapy alone.5,6 Yet complete adoption of IP chemotherapy has been limited by evidence of moderately increased toxicities, such as pain, infections, and bowel obstructions, as well as IP catheter complications.5,7

Heated IP chemotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer

More recently, interest has focused on HIPEC. In this approach, chemotherapy is heated to 42°C and administered into the abdominal cavity immediately after cytoreductive surgery; a temperature of 40°C to 41°C is maintained for total perfusion over a 90-minute period. The increased temperature induces apoptosis and protein degeneration, leading to greater penetration by the chemotherapy along peritoneal surfaces.8

For ovarian cancer, HIPEC has been explored in a number of small studies, predominately for women with recurrent disease.9 These studies demonstrated that HIPEC increased toxicities with gastrointestinal and renal complications but improved overall and disease-free survival.

HIPEC for primary treatment

Van Driel and colleagues explored the safety and efficacy of HIPEC for the primary treatment of ovarian cancer.10 In their multicenter trial, the authors sought to determine if there was a survival benefit with HIPEC in patients with stage III ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer treated with NACT. Eligible participants initially were treated with 3 cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Two-hundred forty-five patients who had a response or stable disease were then randomly assigned to undergo either interval cytoreductive surgery alone or surgery with HIPEC using cisplatin. Both groups received 3 additional cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel after surgery.

Results. Treatment with HIPEC was associated with a 3.5-month improvement in recurrence-free survival compared with surgery alone (14.2 vs 10.7 months) and a 12-month improvement in overall survival (45.7 vs 33.9 months). After a median follow-up of 4.7 years, 62% of patients in the surgery group and 50% of the patients in the HIPEC group had died.

Adverse events. Rates of grade 3 and 4 adverse events were similar for both treatment arms (25% in the surgery group vs 27% in the HIPEC plus surgery group), and there was no significant difference in hospital length of stay (8 vs 10 days, which included a mandatory 1-night stay in the intensive care unit for HIPEC-treated patients).

For carefully selected women with advanced ovarian cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, HIPEC at the time of interval cytoreductive surgery may improve survival by a year.

Continue to: PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer...