User login

Does BSO status affect health outcomes for women taking estrogen for menopause?

Do health effects of menopausal estrogen therapy differ between women with bilateral oophorectomy versus those with conserved ovaries? To answer this question a group of investigators performed a subanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Estrogen-Alone Trial,1 which included 40 clinical centers across the United States. They examined estrogen therapy outcomes by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) status, with additional stratification by 10-year age groups in 9,939 women aged 50 to 79 years with prior hysterectomy and known oophorectomy status. In the WHI trial, women were randomly assigned to conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) 0.625 mg/d or placebo for a median of 7.2 years. Investigators assessed the incidence of coronary heart disease and invasive breast cancer (the trial’s 2 primary end points), all-cause mortality, and a “global index”—these end points plus stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, and hip fracture—during the intervention phase and 18-year cumulative follow-up.

OBG Management caught up with lead author JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP, to discuss the study’s results.

OBG Management : How many women undergo BSO with their hysterectomy?

Dr. JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP: Of the 425,000 women who undergo hysterectomy in the United States for benign reasons each year,2,3 about 40% of them undergo BSO—so between 150,000 and 200,000 women per year undergo BSO with their hysterectomy.4,5

OBG Management : Although BSO is performed with hysterectomy to minimize patients’ future ovarian cancer risk, does BSO have health risks of its own, and how has estrogen been shown to affect these risks?

Dr. Manson: First, yes, BSO has been associated with health risks, especially when it is performed at a young age, such as before age 45. It has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, osteoporosis, cognitive decline, and all-cause mortality. According to observational studies, estrogen therapy appears to offset many of these risks, particularly those related to heart disease and osteoporosis (the evidence is less clear on cognitive deficits).5

OBG Management : What did you find in your trial when you randomly assigned women in the age groups of 50 to 79 who underwent hysterectomy with and without BSO to estrogen therapy or placebo?

Dr. Manson: The WHI is the first study to be conducted in a randomized trial setting to analyze the health risks and benefits of estrogen therapy according to whether or not women had their ovaries removed. What we found was that the woman’s age had a strong influence on the effects of estrogen therapy among women who had BSO but only a negligible effect among women who had conserved ovaries. Overall, across the full age range, the effects of estrogen therapy did not differ substantially between women who had a BSO and those who had their ovaries conserved.

However, there were major differences by age group among the women who had BSO. A significant 32% reduction in all-cause mortality emerged during the 18-year follow-up period among the younger women (below age 60) who had BSO when they received estrogen therapy as compared with placebo. By contrast, the women who had conserved ovaries did not have this significant reduction in all-cause mortality, or in most of the other outcomes on estrogen compared with placebo. Overall, the effects of estrogen therapy tended to be relatively neutral in the women with conserved ovaries.

Now, the reduction in all-cause mortality with estrogen therapy was particularly pronounced among women who had BSO before age 45. They had a 40% statistically significant reduction in all-cause mortality with estrogen therapy compared with placebo. Also, among the women with BSO, there was a strong association between the timing of estrogen initiation and the magnitude of reduction in mortality. Women who started the estrogen therapy within 10 years of having the BSO had a 34% significant reduction in all-cause mortality, and those who started estrogen more than 20 years after having their ovaries removed had no reduction in mortality.

Continue to:

OBG Management : Do your data give support to the timing hypothesis?

Dr. Manson: Yes, our findings do support a timing hypothesis that was particularly pronounced for women who underwent BSO. It was the women who had early surgical menopause (before age 45) and those who started the estrogen therapy within 10 years of having their ovaries removed who had the greatest reduction in all-cause mortality and the most favorable benefit-risk profile from hormone therapy. So, the results do lend support to the timing hypothesis.

By contrast, women who had BSO at hysterectomy and began hormone therapy at age 70 or older had net adverse effects from hormone therapy. They posted a 40% increase in the global index—which is a summary measure of adverse effects on cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other major health outcomes. So, the women with BSO who were randomized in the trial at age 70 and older, had unfavorable results from estrogen therapy and an increase in the global index, in contrast to the women who were below age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.

OBG Management : Given your study findings, in which women would you recommend estrogen therapy? And are there groups of women in which you would advise avoiding estrogen therapy?

Dr. Manson: Current guidelines6,7 recommend estrogen therapy for women who have early menopause, particularly an early surgical menopause and BSO prior to the average age at natural menopause. Unless the woman has contraindications to estrogen therapy, the recommendations are to treat with estrogen until the average age of menopause—until about age 50 to 51.

Our study findings provide reassurance that, if a woman continues to have indications for estrogen (vasomotor symptoms, or other indications for estrogen therapy), there is relative safety of continuing estrogen-alone therapy through her 50s, until age 60. For example, a woman who, after the average age of menopause continues to have vasomotor symptoms, or if she has bone health problems, our study would suggest that estrogen therapy would continue to have a favorable benefit-risk profile until at least the age of 60. Decisions would have to be individualized, especially after age 60, with shared decision-making particularly important for those decisions. (Some women, depending on their risk profile, may continue to be candidates for estrogen therapy past age 60.)

So, this study provides reassurance regarding use of estrogen therapy for women in their 50s if they have had BSO. Actually, the women who had conserved ovaries also had relative safety with estrogen therapy until age 60. They just didn’t show the significant benefits for all-cause mortality. Overall, their pattern of health-related benefits and risks was neutral. Thus, if vasomotor symptom management, quality of life benefits, or bone health effects are sought, taking hormone therapy is a quite reasonable choice for these women.

By contrast, women who have had a BSO and are age 70 or older should really avoid initiating estrogen therapy because it would follow a prolonged period of estrogen deficiency, or very low estrogen levels, and these women appeared to have a net adverse effect from initiating hormone therapy (with increases in the global index found).

Continue to:

OBG Management : Did taking estrogen therapy prior to trial enrollment make a difference when it came to study outcomes?

Dr. Manson: We found minimal if any effect in our analyses. In fact, even the women who did not have prior (pre-randomization) use of estrogen therapy tended to do well on estrogen-alone therapy if they were younger than age 60. This was particularly true for the women who had BSO. Even if they had not used estrogen previously, and they were many years past the BSO, they still did well on estrogen therapy if they were below age 60.

1. Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Bassuk SS. Menopausal estrogen-alone therapy and health outcomes in women with and without bilateral oophorectomy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 September 10. doi:10.7326/M19-0274.

2. Einarsson J. Are hysterectomy volumes in the US really falling? Contemporary OB/GYN. 1 September 2017. www.contemporaryobgyn.net/gynecology/are-hysterectomy-volumes-us-really-falling. November 4, 2019.

3. Temkin SM, Minasian L, Noone AM. The end of the hysterectomy epidemic and endometrial cancer incidence: what are the unintended consequences of declining hysterectomy rates? Front Oncol. 2016;6:89.

4. Doll KM, Dusetzina SB, Robinson W. Trends in inpatient and outpatient hysterectomy and oophorectomy rates among commercially insured women in the United States, 2000-2014. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:876-877.

5. Adelman MR, Sharp HT. Ovarian conservation vs removal at the time of benign hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:269-279.

6. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms [published corrections appear in: Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):166. and Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):604]. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

7. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

Do health effects of menopausal estrogen therapy differ between women with bilateral oophorectomy versus those with conserved ovaries? To answer this question a group of investigators performed a subanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Estrogen-Alone Trial,1 which included 40 clinical centers across the United States. They examined estrogen therapy outcomes by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) status, with additional stratification by 10-year age groups in 9,939 women aged 50 to 79 years with prior hysterectomy and known oophorectomy status. In the WHI trial, women were randomly assigned to conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) 0.625 mg/d or placebo for a median of 7.2 years. Investigators assessed the incidence of coronary heart disease and invasive breast cancer (the trial’s 2 primary end points), all-cause mortality, and a “global index”—these end points plus stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, and hip fracture—during the intervention phase and 18-year cumulative follow-up.

OBG Management caught up with lead author JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP, to discuss the study’s results.

OBG Management : How many women undergo BSO with their hysterectomy?

Dr. JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP: Of the 425,000 women who undergo hysterectomy in the United States for benign reasons each year,2,3 about 40% of them undergo BSO—so between 150,000 and 200,000 women per year undergo BSO with their hysterectomy.4,5

OBG Management : Although BSO is performed with hysterectomy to minimize patients’ future ovarian cancer risk, does BSO have health risks of its own, and how has estrogen been shown to affect these risks?

Dr. Manson: First, yes, BSO has been associated with health risks, especially when it is performed at a young age, such as before age 45. It has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, osteoporosis, cognitive decline, and all-cause mortality. According to observational studies, estrogen therapy appears to offset many of these risks, particularly those related to heart disease and osteoporosis (the evidence is less clear on cognitive deficits).5

OBG Management : What did you find in your trial when you randomly assigned women in the age groups of 50 to 79 who underwent hysterectomy with and without BSO to estrogen therapy or placebo?

Dr. Manson: The WHI is the first study to be conducted in a randomized trial setting to analyze the health risks and benefits of estrogen therapy according to whether or not women had their ovaries removed. What we found was that the woman’s age had a strong influence on the effects of estrogen therapy among women who had BSO but only a negligible effect among women who had conserved ovaries. Overall, across the full age range, the effects of estrogen therapy did not differ substantially between women who had a BSO and those who had their ovaries conserved.

However, there were major differences by age group among the women who had BSO. A significant 32% reduction in all-cause mortality emerged during the 18-year follow-up period among the younger women (below age 60) who had BSO when they received estrogen therapy as compared with placebo. By contrast, the women who had conserved ovaries did not have this significant reduction in all-cause mortality, or in most of the other outcomes on estrogen compared with placebo. Overall, the effects of estrogen therapy tended to be relatively neutral in the women with conserved ovaries.

Now, the reduction in all-cause mortality with estrogen therapy was particularly pronounced among women who had BSO before age 45. They had a 40% statistically significant reduction in all-cause mortality with estrogen therapy compared with placebo. Also, among the women with BSO, there was a strong association between the timing of estrogen initiation and the magnitude of reduction in mortality. Women who started the estrogen therapy within 10 years of having the BSO had a 34% significant reduction in all-cause mortality, and those who started estrogen more than 20 years after having their ovaries removed had no reduction in mortality.

Continue to:

OBG Management : Do your data give support to the timing hypothesis?

Dr. Manson: Yes, our findings do support a timing hypothesis that was particularly pronounced for women who underwent BSO. It was the women who had early surgical menopause (before age 45) and those who started the estrogen therapy within 10 years of having their ovaries removed who had the greatest reduction in all-cause mortality and the most favorable benefit-risk profile from hormone therapy. So, the results do lend support to the timing hypothesis.

By contrast, women who had BSO at hysterectomy and began hormone therapy at age 70 or older had net adverse effects from hormone therapy. They posted a 40% increase in the global index—which is a summary measure of adverse effects on cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other major health outcomes. So, the women with BSO who were randomized in the trial at age 70 and older, had unfavorable results from estrogen therapy and an increase in the global index, in contrast to the women who were below age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.

OBG Management : Given your study findings, in which women would you recommend estrogen therapy? And are there groups of women in which you would advise avoiding estrogen therapy?

Dr. Manson: Current guidelines6,7 recommend estrogen therapy for women who have early menopause, particularly an early surgical menopause and BSO prior to the average age at natural menopause. Unless the woman has contraindications to estrogen therapy, the recommendations are to treat with estrogen until the average age of menopause—until about age 50 to 51.

Our study findings provide reassurance that, if a woman continues to have indications for estrogen (vasomotor symptoms, or other indications for estrogen therapy), there is relative safety of continuing estrogen-alone therapy through her 50s, until age 60. For example, a woman who, after the average age of menopause continues to have vasomotor symptoms, or if she has bone health problems, our study would suggest that estrogen therapy would continue to have a favorable benefit-risk profile until at least the age of 60. Decisions would have to be individualized, especially after age 60, with shared decision-making particularly important for those decisions. (Some women, depending on their risk profile, may continue to be candidates for estrogen therapy past age 60.)

So, this study provides reassurance regarding use of estrogen therapy for women in their 50s if they have had BSO. Actually, the women who had conserved ovaries also had relative safety with estrogen therapy until age 60. They just didn’t show the significant benefits for all-cause mortality. Overall, their pattern of health-related benefits and risks was neutral. Thus, if vasomotor symptom management, quality of life benefits, or bone health effects are sought, taking hormone therapy is a quite reasonable choice for these women.

By contrast, women who have had a BSO and are age 70 or older should really avoid initiating estrogen therapy because it would follow a prolonged period of estrogen deficiency, or very low estrogen levels, and these women appeared to have a net adverse effect from initiating hormone therapy (with increases in the global index found).

Continue to:

OBG Management : Did taking estrogen therapy prior to trial enrollment make a difference when it came to study outcomes?

Dr. Manson: We found minimal if any effect in our analyses. In fact, even the women who did not have prior (pre-randomization) use of estrogen therapy tended to do well on estrogen-alone therapy if they were younger than age 60. This was particularly true for the women who had BSO. Even if they had not used estrogen previously, and they were many years past the BSO, they still did well on estrogen therapy if they were below age 60.

Do health effects of menopausal estrogen therapy differ between women with bilateral oophorectomy versus those with conserved ovaries? To answer this question a group of investigators performed a subanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Estrogen-Alone Trial,1 which included 40 clinical centers across the United States. They examined estrogen therapy outcomes by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) status, with additional stratification by 10-year age groups in 9,939 women aged 50 to 79 years with prior hysterectomy and known oophorectomy status. In the WHI trial, women were randomly assigned to conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) 0.625 mg/d or placebo for a median of 7.2 years. Investigators assessed the incidence of coronary heart disease and invasive breast cancer (the trial’s 2 primary end points), all-cause mortality, and a “global index”—these end points plus stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, and hip fracture—during the intervention phase and 18-year cumulative follow-up.

OBG Management caught up with lead author JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP, to discuss the study’s results.

OBG Management : How many women undergo BSO with their hysterectomy?

Dr. JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP: Of the 425,000 women who undergo hysterectomy in the United States for benign reasons each year,2,3 about 40% of them undergo BSO—so between 150,000 and 200,000 women per year undergo BSO with their hysterectomy.4,5

OBG Management : Although BSO is performed with hysterectomy to minimize patients’ future ovarian cancer risk, does BSO have health risks of its own, and how has estrogen been shown to affect these risks?

Dr. Manson: First, yes, BSO has been associated with health risks, especially when it is performed at a young age, such as before age 45. It has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, osteoporosis, cognitive decline, and all-cause mortality. According to observational studies, estrogen therapy appears to offset many of these risks, particularly those related to heart disease and osteoporosis (the evidence is less clear on cognitive deficits).5

OBG Management : What did you find in your trial when you randomly assigned women in the age groups of 50 to 79 who underwent hysterectomy with and without BSO to estrogen therapy or placebo?

Dr. Manson: The WHI is the first study to be conducted in a randomized trial setting to analyze the health risks and benefits of estrogen therapy according to whether or not women had their ovaries removed. What we found was that the woman’s age had a strong influence on the effects of estrogen therapy among women who had BSO but only a negligible effect among women who had conserved ovaries. Overall, across the full age range, the effects of estrogen therapy did not differ substantially between women who had a BSO and those who had their ovaries conserved.

However, there were major differences by age group among the women who had BSO. A significant 32% reduction in all-cause mortality emerged during the 18-year follow-up period among the younger women (below age 60) who had BSO when they received estrogen therapy as compared with placebo. By contrast, the women who had conserved ovaries did not have this significant reduction in all-cause mortality, or in most of the other outcomes on estrogen compared with placebo. Overall, the effects of estrogen therapy tended to be relatively neutral in the women with conserved ovaries.

Now, the reduction in all-cause mortality with estrogen therapy was particularly pronounced among women who had BSO before age 45. They had a 40% statistically significant reduction in all-cause mortality with estrogen therapy compared with placebo. Also, among the women with BSO, there was a strong association between the timing of estrogen initiation and the magnitude of reduction in mortality. Women who started the estrogen therapy within 10 years of having the BSO had a 34% significant reduction in all-cause mortality, and those who started estrogen more than 20 years after having their ovaries removed had no reduction in mortality.

Continue to:

OBG Management : Do your data give support to the timing hypothesis?

Dr. Manson: Yes, our findings do support a timing hypothesis that was particularly pronounced for women who underwent BSO. It was the women who had early surgical menopause (before age 45) and those who started the estrogen therapy within 10 years of having their ovaries removed who had the greatest reduction in all-cause mortality and the most favorable benefit-risk profile from hormone therapy. So, the results do lend support to the timing hypothesis.

By contrast, women who had BSO at hysterectomy and began hormone therapy at age 70 or older had net adverse effects from hormone therapy. They posted a 40% increase in the global index—which is a summary measure of adverse effects on cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other major health outcomes. So, the women with BSO who were randomized in the trial at age 70 and older, had unfavorable results from estrogen therapy and an increase in the global index, in contrast to the women who were below age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.

OBG Management : Given your study findings, in which women would you recommend estrogen therapy? And are there groups of women in which you would advise avoiding estrogen therapy?

Dr. Manson: Current guidelines6,7 recommend estrogen therapy for women who have early menopause, particularly an early surgical menopause and BSO prior to the average age at natural menopause. Unless the woman has contraindications to estrogen therapy, the recommendations are to treat with estrogen until the average age of menopause—until about age 50 to 51.

Our study findings provide reassurance that, if a woman continues to have indications for estrogen (vasomotor symptoms, or other indications for estrogen therapy), there is relative safety of continuing estrogen-alone therapy through her 50s, until age 60. For example, a woman who, after the average age of menopause continues to have vasomotor symptoms, or if she has bone health problems, our study would suggest that estrogen therapy would continue to have a favorable benefit-risk profile until at least the age of 60. Decisions would have to be individualized, especially after age 60, with shared decision-making particularly important for those decisions. (Some women, depending on their risk profile, may continue to be candidates for estrogen therapy past age 60.)

So, this study provides reassurance regarding use of estrogen therapy for women in their 50s if they have had BSO. Actually, the women who had conserved ovaries also had relative safety with estrogen therapy until age 60. They just didn’t show the significant benefits for all-cause mortality. Overall, their pattern of health-related benefits and risks was neutral. Thus, if vasomotor symptom management, quality of life benefits, or bone health effects are sought, taking hormone therapy is a quite reasonable choice for these women.

By contrast, women who have had a BSO and are age 70 or older should really avoid initiating estrogen therapy because it would follow a prolonged period of estrogen deficiency, or very low estrogen levels, and these women appeared to have a net adverse effect from initiating hormone therapy (with increases in the global index found).

Continue to:

OBG Management : Did taking estrogen therapy prior to trial enrollment make a difference when it came to study outcomes?

Dr. Manson: We found minimal if any effect in our analyses. In fact, even the women who did not have prior (pre-randomization) use of estrogen therapy tended to do well on estrogen-alone therapy if they were younger than age 60. This was particularly true for the women who had BSO. Even if they had not used estrogen previously, and they were many years past the BSO, they still did well on estrogen therapy if they were below age 60.

1. Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Bassuk SS. Menopausal estrogen-alone therapy and health outcomes in women with and without bilateral oophorectomy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 September 10. doi:10.7326/M19-0274.

2. Einarsson J. Are hysterectomy volumes in the US really falling? Contemporary OB/GYN. 1 September 2017. www.contemporaryobgyn.net/gynecology/are-hysterectomy-volumes-us-really-falling. November 4, 2019.

3. Temkin SM, Minasian L, Noone AM. The end of the hysterectomy epidemic and endometrial cancer incidence: what are the unintended consequences of declining hysterectomy rates? Front Oncol. 2016;6:89.

4. Doll KM, Dusetzina SB, Robinson W. Trends in inpatient and outpatient hysterectomy and oophorectomy rates among commercially insured women in the United States, 2000-2014. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:876-877.

5. Adelman MR, Sharp HT. Ovarian conservation vs removal at the time of benign hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:269-279.

6. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms [published corrections appear in: Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):166. and Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):604]. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

7. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

1. Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Bassuk SS. Menopausal estrogen-alone therapy and health outcomes in women with and without bilateral oophorectomy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 September 10. doi:10.7326/M19-0274.

2. Einarsson J. Are hysterectomy volumes in the US really falling? Contemporary OB/GYN. 1 September 2017. www.contemporaryobgyn.net/gynecology/are-hysterectomy-volumes-us-really-falling. November 4, 2019.

3. Temkin SM, Minasian L, Noone AM. The end of the hysterectomy epidemic and endometrial cancer incidence: what are the unintended consequences of declining hysterectomy rates? Front Oncol. 2016;6:89.

4. Doll KM, Dusetzina SB, Robinson W. Trends in inpatient and outpatient hysterectomy and oophorectomy rates among commercially insured women in the United States, 2000-2014. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:876-877.

5. Adelman MR, Sharp HT. Ovarian conservation vs removal at the time of benign hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:269-279.

6. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms [published corrections appear in: Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):166. and Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):604]. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

7. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

Product Update: Addyi alcohol ban lifted, fezolinetant trial, outcomes tracker, comfort gown

FDA REMOVES ALCOHOL BAN WITH ADDYI

Sprout Pharmaceuticals announced that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed their contraindication on alcohol use with Addyi® (flibanserin). Addyi was approved in 2015 and is an oral nonhormonal pill for acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women. Patients are advised to discontinue drinking alcohol at least 2 hours before taking Addyi at bedtime or skip the Addyi dose that evening.

The FDA also removed the requirement, under its Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, for health care practitioners or pharmacies to be certified to prescribe or dispense Addyi. Sprout says that to make all labeling elements consistent with the FDA’s findings the boxed warning will change and the medication guide will be updated and included under the REMS.

The most commonly reported adverse events among patients taking Addyi are dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth. Addyi is contraindicated in patients taking moderate or strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inhibitors and in those with hepatic impairment.

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND THE FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION AND MEDICATION GUIDE, VISIT: www.addyi.com

FEZOLINETANT FOR VMS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, TRIAL IDENTIFIERS NCT04003155, NCT04003142, AND NCT04003389

SOLUTIONS FOR OUTCOME TRACKING

DrChrono and OutcomeMD announce a partnership to track and analyze patient outcome data and confounding factors. DrChrono is an electronic health record (EHR) system, and OutcomeMD is a software solution that uses literature-validated patient-reported outcome instruments to score and track a patient’s symptom severity and inform treatment decisions for users.

Via a HIPAA compliant process, patients answer a list of questions that are accessed through a web link on their mobile or desktop devices. OutcomeMD summarizes the symptoms into a score that displays to both the physician and patient. Patients’ answers and scores are pushed to the clinician’s DrChrono EHR medical note.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.outcomemd.com

Continue to: NEW MATERNITY GOWN...

NEW MATERNITY GOWN

ImageFIRST launched a new maternity gown for expecting mothers. The Comfort Care® Maternity Gown is a lightweight, premium polyester/nylon fabric that front snaps to allow for skin-to-skin access and optional breastfeeding. The gown also includes shoulder snaps and a full cut for extra coverage and to accommodate a variety of body types, says ImageFIRST.

ImageFIRST is a national linen rental provider. It developed the Comfort Care® Maternity Gown with input from labor and delivery departments to best meet the needs of expecting mothers. It also says that a portion of the proceeds from each gown rental will be donated to the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.imagefirst.com

FDA REMOVES ALCOHOL BAN WITH ADDYI

Sprout Pharmaceuticals announced that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed their contraindication on alcohol use with Addyi® (flibanserin). Addyi was approved in 2015 and is an oral nonhormonal pill for acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women. Patients are advised to discontinue drinking alcohol at least 2 hours before taking Addyi at bedtime or skip the Addyi dose that evening.

The FDA also removed the requirement, under its Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, for health care practitioners or pharmacies to be certified to prescribe or dispense Addyi. Sprout says that to make all labeling elements consistent with the FDA’s findings the boxed warning will change and the medication guide will be updated and included under the REMS.

The most commonly reported adverse events among patients taking Addyi are dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth. Addyi is contraindicated in patients taking moderate or strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inhibitors and in those with hepatic impairment.

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND THE FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION AND MEDICATION GUIDE, VISIT: www.addyi.com

FEZOLINETANT FOR VMS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, TRIAL IDENTIFIERS NCT04003155, NCT04003142, AND NCT04003389

SOLUTIONS FOR OUTCOME TRACKING

DrChrono and OutcomeMD announce a partnership to track and analyze patient outcome data and confounding factors. DrChrono is an electronic health record (EHR) system, and OutcomeMD is a software solution that uses literature-validated patient-reported outcome instruments to score and track a patient’s symptom severity and inform treatment decisions for users.

Via a HIPAA compliant process, patients answer a list of questions that are accessed through a web link on their mobile or desktop devices. OutcomeMD summarizes the symptoms into a score that displays to both the physician and patient. Patients’ answers and scores are pushed to the clinician’s DrChrono EHR medical note.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.outcomemd.com

Continue to: NEW MATERNITY GOWN...

NEW MATERNITY GOWN

ImageFIRST launched a new maternity gown for expecting mothers. The Comfort Care® Maternity Gown is a lightweight, premium polyester/nylon fabric that front snaps to allow for skin-to-skin access and optional breastfeeding. The gown also includes shoulder snaps and a full cut for extra coverage and to accommodate a variety of body types, says ImageFIRST.

ImageFIRST is a national linen rental provider. It developed the Comfort Care® Maternity Gown with input from labor and delivery departments to best meet the needs of expecting mothers. It also says that a portion of the proceeds from each gown rental will be donated to the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.imagefirst.com

FDA REMOVES ALCOHOL BAN WITH ADDYI

Sprout Pharmaceuticals announced that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed their contraindication on alcohol use with Addyi® (flibanserin). Addyi was approved in 2015 and is an oral nonhormonal pill for acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women. Patients are advised to discontinue drinking alcohol at least 2 hours before taking Addyi at bedtime or skip the Addyi dose that evening.

The FDA also removed the requirement, under its Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, for health care practitioners or pharmacies to be certified to prescribe or dispense Addyi. Sprout says that to make all labeling elements consistent with the FDA’s findings the boxed warning will change and the medication guide will be updated and included under the REMS.

The most commonly reported adverse events among patients taking Addyi are dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth. Addyi is contraindicated in patients taking moderate or strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inhibitors and in those with hepatic impairment.

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND THE FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION AND MEDICATION GUIDE, VISIT: www.addyi.com

FEZOLINETANT FOR VMS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, TRIAL IDENTIFIERS NCT04003155, NCT04003142, AND NCT04003389

SOLUTIONS FOR OUTCOME TRACKING

DrChrono and OutcomeMD announce a partnership to track and analyze patient outcome data and confounding factors. DrChrono is an electronic health record (EHR) system, and OutcomeMD is a software solution that uses literature-validated patient-reported outcome instruments to score and track a patient’s symptom severity and inform treatment decisions for users.

Via a HIPAA compliant process, patients answer a list of questions that are accessed through a web link on their mobile or desktop devices. OutcomeMD summarizes the symptoms into a score that displays to both the physician and patient. Patients’ answers and scores are pushed to the clinician’s DrChrono EHR medical note.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.outcomemd.com

Continue to: NEW MATERNITY GOWN...

NEW MATERNITY GOWN

ImageFIRST launched a new maternity gown for expecting mothers. The Comfort Care® Maternity Gown is a lightweight, premium polyester/nylon fabric that front snaps to allow for skin-to-skin access and optional breastfeeding. The gown also includes shoulder snaps and a full cut for extra coverage and to accommodate a variety of body types, says ImageFIRST.

ImageFIRST is a national linen rental provider. It developed the Comfort Care® Maternity Gown with input from labor and delivery departments to best meet the needs of expecting mothers. It also says that a portion of the proceeds from each gown rental will be donated to the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.imagefirst.com

Persistent vulvar itch: What is the diagnosis?

Genital lichen simplex chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is an inflammatory skin condition that develops secondary to persistent rubbing or scratching of skin. Although LSC can occur anywhere on the body, genital LSC develops in association with genital itch, with the itch often described as intense and unrelenting. The itching sensation leads to scratching and rubbing of the area, which can provide temporary symptomatic relief.1,2 However, this action of rubbing and scratching stimulates local cutaneous nerves, inducing an even more intense itch sensation. This process, identified as the ‘itch-scratch cycle,’ plays a prominent role in all cases of LSC.1

On physical examination LSC appears as poorly defined, pink to red plaques with accentuated skin markings on bilateral labia majora. Less commonly, it can present as asymmetrical or unilateral plaques.3 LSC can extend onto labia minora, mons pubis, and medial thighs. However, the vagina is spared.1 Excoriations, marked by their geometric, angular appearance, often can be appreciated overlying plaques of LSC. Additionally, crusting, scale, broken hairs, hyperpigmentation, and scarring may be seen in LSC.2

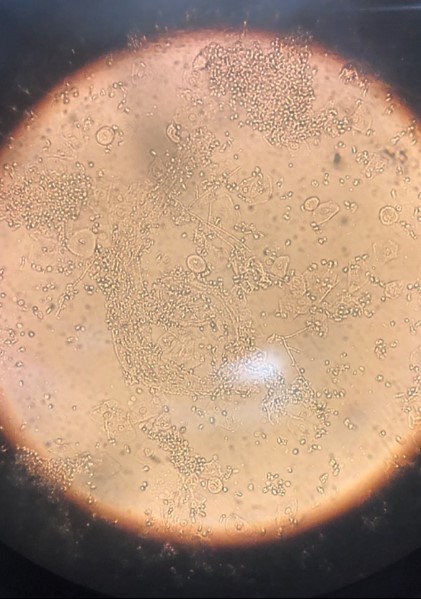

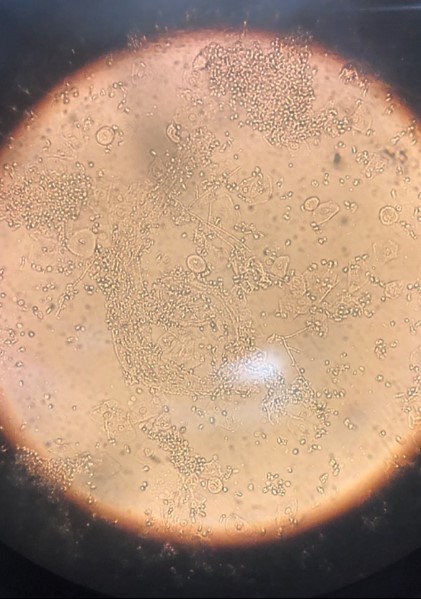

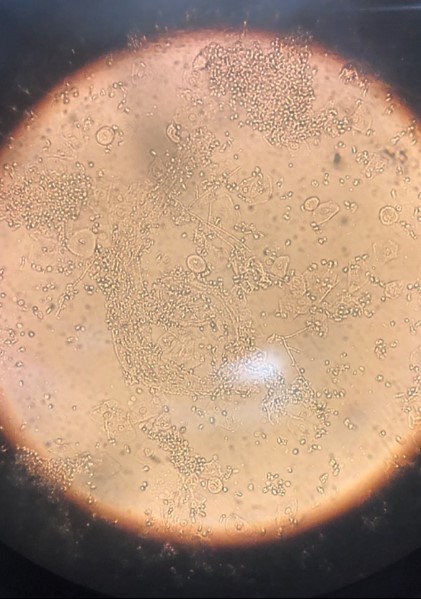

In this case, white discharge was noted on vaginal examination, which was suspicious for vaginal candidiasis. Wet mount examination revealed multiple candida hyphae and spores (FIGURE 2), confirming vaginal candidiasis. This vulvovaginal fungal infection caused persistent vulvar pruritus, with subsequent development of LSC due to prolonged scratching. The patient was treated with both oral fluconazole and topical mometasone ointment, for vaginal candidiasis and vulvar LSC, respectively. Mometasone ointment is categorized as a class II (high potency) topical steroid. However, it is worth noting that mometasone cream is categorized as a class IV (medium potency) topical steroid.

FIGURE 2 Wet mount of vaginal discharge, revealing candida hyphae and spores

Treatment

Successful treatment of LSC requires addressing 4 elements, including recognizing and treating the underlying etiology, restoring barrier function, reducing inflammation, and interrupting the itch-scratch cycle.3

Identifying the underlying etiology. Knowing the etiology of vulvar pruritus is a key step in resolution of the condition because LSC is driven by repetitive rubbing and scratching behaviors in response to the itch. The differential diagnosis for vulvar pruritus is broad. Evaluation and workup should be tailored to suit each unique patient presentation. A review of past medical history and full-body skin examination can identify a contributing inflammatory skin disease, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, or autoimmune vesiculobullous disease (pemphigus).1,2 Careful review of products applied in the genital area can reveal an underlying irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. Scented soap or detergent commonly cause vulvar dermatitis.1 A speculum examination may suggest inflammatory vaginitis or atrophic vaginitis (genitourinary syndrome of menopause); run off of vaginal discharge onto the vulvar skin can result in vulvar pruritus. Vaginal wet mount can diagnose vulvovaginal candidiasis, trichomonas infection, and bacterial vaginitis.1 A skin scraping with mineral oil or potassium hydroxide can suggest scabies infestation or cutaneous dermatophyte infection, respectively.2 Treatment of vulvar pruritus should be initiated based on diagnosis.

Restoring barrier function. The repetitive scratching and rubbing behaviors disrupt the cutaneous barrier layer and lead to stimulation of the local nerves. This creates more itch and further traumatization to the barrier. Barrier function can be restored through soaking the area, with sitz baths or damp towels. Following 20- to 30-minute soaks, a lubricant, such as petroleum jelly, should be applied to the area.3

Reducing inflammation. To reduce inflammation, topical steroids should be applied to areas of LSC.3 In severe cases, high potency topical steroids should be prescribed. Examples of high potency topical steroids include:

- clobetasol propionate 0.05%

- betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%

- halobetasol propionate 0.05%.

Ointment is the choice vehicle because it is both more potent and associated with decreased stinging sensation. High potency steroid ointment should be applied twice daily for at least 2 to 4 weeks. The transition to lower potency topical steroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% ointment, can be made as the LSC improves.2

Interrupting the itch-scratch cycle. As noted above, persistent rubbing and scratching generates increased itch sensation. Thus, breaking the itch-scratch cycle is essential. Nighttime scratching can be improved with hydroxyzine. The effective dosage ranges between 25 and 75 mg and should be titrated up slowly every 5 to 7 days. Sedation is a major adverse effect of hydroxyzine, limiting the treatment of daytime itching. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as citalopram, also have been found to be effective. Over the counter, nonsedation antihistamines have not been found to be useful in breaking the itch-scratch cycle. The clinical course of LSC is chronic (as the name implies), waxing and waning, and sometimes can be challenging to treat—some patients require years-long continued follow-up and treatment.3

- Savas JA, Pichardo RO. Female genital itch. Dermatologic Clin. 2018;36:225-243.

- Chibnall R. Vulvar pruritus and lichen simplex chronicus. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:379-388.

- Lynch PJ. Lichen simplex chronicus (atopic/neurodermatitis) of the anogenital region. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:8-19.

Genital lichen simplex chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is an inflammatory skin condition that develops secondary to persistent rubbing or scratching of skin. Although LSC can occur anywhere on the body, genital LSC develops in association with genital itch, with the itch often described as intense and unrelenting. The itching sensation leads to scratching and rubbing of the area, which can provide temporary symptomatic relief.1,2 However, this action of rubbing and scratching stimulates local cutaneous nerves, inducing an even more intense itch sensation. This process, identified as the ‘itch-scratch cycle,’ plays a prominent role in all cases of LSC.1

On physical examination LSC appears as poorly defined, pink to red plaques with accentuated skin markings on bilateral labia majora. Less commonly, it can present as asymmetrical or unilateral plaques.3 LSC can extend onto labia minora, mons pubis, and medial thighs. However, the vagina is spared.1 Excoriations, marked by their geometric, angular appearance, often can be appreciated overlying plaques of LSC. Additionally, crusting, scale, broken hairs, hyperpigmentation, and scarring may be seen in LSC.2

In this case, white discharge was noted on vaginal examination, which was suspicious for vaginal candidiasis. Wet mount examination revealed multiple candida hyphae and spores (FIGURE 2), confirming vaginal candidiasis. This vulvovaginal fungal infection caused persistent vulvar pruritus, with subsequent development of LSC due to prolonged scratching. The patient was treated with both oral fluconazole and topical mometasone ointment, for vaginal candidiasis and vulvar LSC, respectively. Mometasone ointment is categorized as a class II (high potency) topical steroid. However, it is worth noting that mometasone cream is categorized as a class IV (medium potency) topical steroid.

FIGURE 2 Wet mount of vaginal discharge, revealing candida hyphae and spores

Treatment

Successful treatment of LSC requires addressing 4 elements, including recognizing and treating the underlying etiology, restoring barrier function, reducing inflammation, and interrupting the itch-scratch cycle.3

Identifying the underlying etiology. Knowing the etiology of vulvar pruritus is a key step in resolution of the condition because LSC is driven by repetitive rubbing and scratching behaviors in response to the itch. The differential diagnosis for vulvar pruritus is broad. Evaluation and workup should be tailored to suit each unique patient presentation. A review of past medical history and full-body skin examination can identify a contributing inflammatory skin disease, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, or autoimmune vesiculobullous disease (pemphigus).1,2 Careful review of products applied in the genital area can reveal an underlying irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. Scented soap or detergent commonly cause vulvar dermatitis.1 A speculum examination may suggest inflammatory vaginitis or atrophic vaginitis (genitourinary syndrome of menopause); run off of vaginal discharge onto the vulvar skin can result in vulvar pruritus. Vaginal wet mount can diagnose vulvovaginal candidiasis, trichomonas infection, and bacterial vaginitis.1 A skin scraping with mineral oil or potassium hydroxide can suggest scabies infestation or cutaneous dermatophyte infection, respectively.2 Treatment of vulvar pruritus should be initiated based on diagnosis.

Restoring barrier function. The repetitive scratching and rubbing behaviors disrupt the cutaneous barrier layer and lead to stimulation of the local nerves. This creates more itch and further traumatization to the barrier. Barrier function can be restored through soaking the area, with sitz baths or damp towels. Following 20- to 30-minute soaks, a lubricant, such as petroleum jelly, should be applied to the area.3

Reducing inflammation. To reduce inflammation, topical steroids should be applied to areas of LSC.3 In severe cases, high potency topical steroids should be prescribed. Examples of high potency topical steroids include:

- clobetasol propionate 0.05%

- betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%

- halobetasol propionate 0.05%.

Ointment is the choice vehicle because it is both more potent and associated with decreased stinging sensation. High potency steroid ointment should be applied twice daily for at least 2 to 4 weeks. The transition to lower potency topical steroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% ointment, can be made as the LSC improves.2

Interrupting the itch-scratch cycle. As noted above, persistent rubbing and scratching generates increased itch sensation. Thus, breaking the itch-scratch cycle is essential. Nighttime scratching can be improved with hydroxyzine. The effective dosage ranges between 25 and 75 mg and should be titrated up slowly every 5 to 7 days. Sedation is a major adverse effect of hydroxyzine, limiting the treatment of daytime itching. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as citalopram, also have been found to be effective. Over the counter, nonsedation antihistamines have not been found to be useful in breaking the itch-scratch cycle. The clinical course of LSC is chronic (as the name implies), waxing and waning, and sometimes can be challenging to treat—some patients require years-long continued follow-up and treatment.3

Genital lichen simplex chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is an inflammatory skin condition that develops secondary to persistent rubbing or scratching of skin. Although LSC can occur anywhere on the body, genital LSC develops in association with genital itch, with the itch often described as intense and unrelenting. The itching sensation leads to scratching and rubbing of the area, which can provide temporary symptomatic relief.1,2 However, this action of rubbing and scratching stimulates local cutaneous nerves, inducing an even more intense itch sensation. This process, identified as the ‘itch-scratch cycle,’ plays a prominent role in all cases of LSC.1

On physical examination LSC appears as poorly defined, pink to red plaques with accentuated skin markings on bilateral labia majora. Less commonly, it can present as asymmetrical or unilateral plaques.3 LSC can extend onto labia minora, mons pubis, and medial thighs. However, the vagina is spared.1 Excoriations, marked by their geometric, angular appearance, often can be appreciated overlying plaques of LSC. Additionally, crusting, scale, broken hairs, hyperpigmentation, and scarring may be seen in LSC.2

In this case, white discharge was noted on vaginal examination, which was suspicious for vaginal candidiasis. Wet mount examination revealed multiple candida hyphae and spores (FIGURE 2), confirming vaginal candidiasis. This vulvovaginal fungal infection caused persistent vulvar pruritus, with subsequent development of LSC due to prolonged scratching. The patient was treated with both oral fluconazole and topical mometasone ointment, for vaginal candidiasis and vulvar LSC, respectively. Mometasone ointment is categorized as a class II (high potency) topical steroid. However, it is worth noting that mometasone cream is categorized as a class IV (medium potency) topical steroid.

FIGURE 2 Wet mount of vaginal discharge, revealing candida hyphae and spores

Treatment

Successful treatment of LSC requires addressing 4 elements, including recognizing and treating the underlying etiology, restoring barrier function, reducing inflammation, and interrupting the itch-scratch cycle.3

Identifying the underlying etiology. Knowing the etiology of vulvar pruritus is a key step in resolution of the condition because LSC is driven by repetitive rubbing and scratching behaviors in response to the itch. The differential diagnosis for vulvar pruritus is broad. Evaluation and workup should be tailored to suit each unique patient presentation. A review of past medical history and full-body skin examination can identify a contributing inflammatory skin disease, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, or autoimmune vesiculobullous disease (pemphigus).1,2 Careful review of products applied in the genital area can reveal an underlying irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. Scented soap or detergent commonly cause vulvar dermatitis.1 A speculum examination may suggest inflammatory vaginitis or atrophic vaginitis (genitourinary syndrome of menopause); run off of vaginal discharge onto the vulvar skin can result in vulvar pruritus. Vaginal wet mount can diagnose vulvovaginal candidiasis, trichomonas infection, and bacterial vaginitis.1 A skin scraping with mineral oil or potassium hydroxide can suggest scabies infestation or cutaneous dermatophyte infection, respectively.2 Treatment of vulvar pruritus should be initiated based on diagnosis.

Restoring barrier function. The repetitive scratching and rubbing behaviors disrupt the cutaneous barrier layer and lead to stimulation of the local nerves. This creates more itch and further traumatization to the barrier. Barrier function can be restored through soaking the area, with sitz baths or damp towels. Following 20- to 30-minute soaks, a lubricant, such as petroleum jelly, should be applied to the area.3

Reducing inflammation. To reduce inflammation, topical steroids should be applied to areas of LSC.3 In severe cases, high potency topical steroids should be prescribed. Examples of high potency topical steroids include:

- clobetasol propionate 0.05%

- betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%

- halobetasol propionate 0.05%.

Ointment is the choice vehicle because it is both more potent and associated with decreased stinging sensation. High potency steroid ointment should be applied twice daily for at least 2 to 4 weeks. The transition to lower potency topical steroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% ointment, can be made as the LSC improves.2

Interrupting the itch-scratch cycle. As noted above, persistent rubbing and scratching generates increased itch sensation. Thus, breaking the itch-scratch cycle is essential. Nighttime scratching can be improved with hydroxyzine. The effective dosage ranges between 25 and 75 mg and should be titrated up slowly every 5 to 7 days. Sedation is a major adverse effect of hydroxyzine, limiting the treatment of daytime itching. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as citalopram, also have been found to be effective. Over the counter, nonsedation antihistamines have not been found to be useful in breaking the itch-scratch cycle. The clinical course of LSC is chronic (as the name implies), waxing and waning, and sometimes can be challenging to treat—some patients require years-long continued follow-up and treatment.3

- Savas JA, Pichardo RO. Female genital itch. Dermatologic Clin. 2018;36:225-243.

- Chibnall R. Vulvar pruritus and lichen simplex chronicus. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:379-388.

- Lynch PJ. Lichen simplex chronicus (atopic/neurodermatitis) of the anogenital region. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:8-19.

- Savas JA, Pichardo RO. Female genital itch. Dermatologic Clin. 2018;36:225-243.

- Chibnall R. Vulvar pruritus and lichen simplex chronicus. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:379-388.

- Lynch PJ. Lichen simplex chronicus (atopic/neurodermatitis) of the anogenital region. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:8-19.

CASE Lingering vulvar pruritus developed during traveling

A 48-year-old premenopausal Hispanic woman with past medical history of breast cancer presents to a dermatologist with the chief complaint of persistent vulvar pruritus. The vulvar itching began while traveling and has continued for 6 months. Previous treatments have been trialed, including over-the-counter feminine hygiene products, wipes, and hydrocortisone ointment.

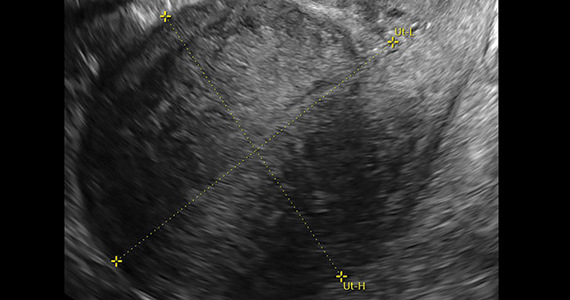

Physical examination reveals pink, symmetric, bilateral lichenified plaques on the labia majora, without evidence of atrophy or scarring ( FIGURE 1 ). Scant white vaginal discharge is also noted.

FIGURE 1 Bilateral labia majora show lichenification

Figure caption: On bilateral labia majora, symmetric, pink plaques with accentuated skin markings (lichenification) noted on physical examination. Scant white vaginal discharge was noted on exam but is inconspicuous in photo.

Hysterectomy in patients with history of prior cesarean delivery: A reverse dissection technique for vesicouterine adhesions

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, which have revolutionized modern-day surgery, are the current standard of care for benign hysterectomies.1-4 Many surgeons use a video-laparoscopic approach, with or without robotic assistance, to perform a hysterectomy. The development of a bladder flap or vesicovaginal surgical space is a critical step for mobilizing the bladder. When properly performed, it allows for appropriate closure of the vaginal cuff while mitigating the risk of urinary bladder damage.

In patients with no prior pelvic surgeries, this vesicovaginal anatomic space is typically developed with ease. However, in patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries (CDs), the presence of vesicouterine adhesions could make this step significantly more challenging. As a result, the risk of bladder injury is higher.5-8

With the current tide of cesarean birth rates approaching 33% on a national scale, the presence of vesicouterine adhesions is commonly encountered.9 These adhesions can distort the anatomy and thereby create more difficult dissections and increase operative time, conversion to laparotomy, and inadvertent cystotomy. Such a challenge also presents an increased risk of injuring adjacent structures.

In this article, we describe an effective method of dissection that is especially useful in the setting of prior CDs. This method involves developing a "new" surgical space lateral and caudal to the vesicocervical space.

Steps in operative planning

Preoperative evaluation. A thorough preoperative evaluation should be performed for patients planning to undergo a laparoscopic hysterectomy. This includes obtaining details of their medical and surgical history. Access to prior surgical records may help to facilitate planning of the surgical approach. Previous pelvic surgery, such as CD, anterior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect repair, endometriosis treatment, or exploratory laparotomy, may predispose these patients to develop adhesions in the anterior cul-de-sac. Our method of reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be particularly efficacious in these settings.

Surgical preparation and laparoscopic port placement. In the operative suite, the patient is placed under general anesthesia and positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position.10 Sterile prep and drapes are used in the standard fashion. A urinary catheter is inserted to maintain a decompressed bladder. A uterine manipulator is inserted with good placement ensured.

Per our practice, we introduce laparoscopic ports in 4 locations. The first incision is made in the umbilicus for the introduction of a 10-mm laparoscope. Three subsequent 5-mm incisions are made in the left and right lower lateral quadrants and medially at the level of the suprapubic region.10 Upon laparoscopic entry, we perform a comprehensive survey of the abdominopelvic cavity. Adequate mobility of the uterus is confirmed.11 Any posterior uterine adhesions or endometriosis are treated appropriately.12

First step in the surgical technique: Lateral dissection

We proceed by first desiccating and cutting the round ligament laterally near the inguinal canal. This technique is carried forward in a caudal direction as the areolar tissue near the obliterated umbilical artery is expanded by the pneumoperitoneum. With a vessel sealing-cutting device, we address the attachments to the adnexa. If the ovaries are to be retained, the utero-ovarian ligament is dessicated and cut. If an oophorectomy is indicated, the infundibulopelvic ligament is dessicated and cut.

Continue to: Using the tip of the vessel sealing...

Using the tip of the vessel sealing-cutting device, the space between the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament is developed and opened. A grasping forceps is then used to elevate the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and maintain medial traction. A space parallel and lateral to the cervix and bladder is then created with blunt dissection.

The inferior and medial direction of this dissection is paramount to avoid injury to nearby structures in the pelvic sidewall. Gradually, this will lead to the identification of the vesciovaginal ligament and then the vesicocervical ligament. The development of these spaces allows for the lateral and inferior displacement of the ureter. These maneuvers can mitigate ureter injury by pushing it away from the planes of dissection during the hysterectomy.

Continued traction is maintained by keeping the medial aspect of the anterior leaf of the broad ligament intact. However, the posterior leaf is dissected next, which further lateralizes the ureter. Now, with the uterine vessels fully exposed, they are thoroughly dessicated and ligated. The same procedure is then performed on the contralateral side.11 (See the box below for links to videos that demonstrate the techniques described here.)

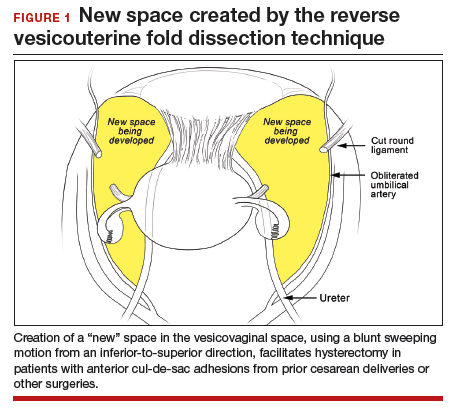

Creating the “new” space

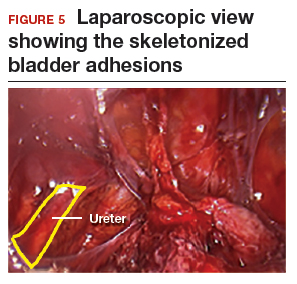

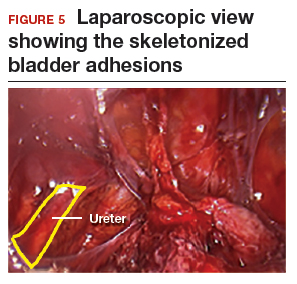

In the “new” space that was partially developed during the lateral dissection, blunt dissection is continued, using a sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, to extend this avascular space. This is performed bilaterally until both sides are connected from the inferior aspect of the vesicouterine adhesions, if present. This thorough dissection creates what we refer to as a “new” space11 (FIGURE 1).

Medially, the new space is bordered by the vesicocervical-vaginal ligament, also known as the bladder pillar. Its distal landmark is the bladder. The remaining intact anterior leaf of the broad ligament lies adjacent to the space anteriorly. The inner aspect of the obliterated umbilical artery neighbors it laterally. Lastly, the vesicovaginal plane’s posterior margin is the parametrium, which is the region where the ureter courses into the bladder. The paravesical space lies lateral to the obliterated umbilical ligament.

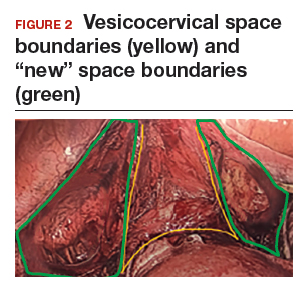

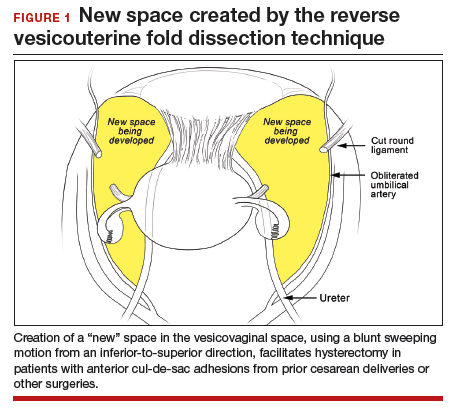

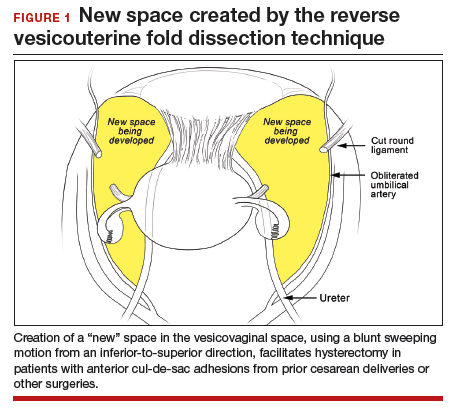

Visualization of this new space is made possible in the laparoscopic setting. The pneumoperitoneum allows for better demarcation of the space. Additionally, laparoscopic views of the anatomic spaces differ from those of the laparotomy view because of the magnification and the insufflation of carbon dioxide gas in the spaces.13,14 In our experience, approaching the surgery from the “new” space could significantly decrease the risk of genitourinary injuries in patients with anterior cul-de-sac adhesions (FIGURE 2).

Using the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique

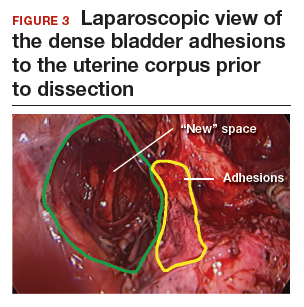

Among patients with prior CDs, adhesions often are at the level of or superior to the prior CD scar. By creating the new space, safe dissection from a previously untouched area can be accomplished and injury to the urinary bladder can be avoided.

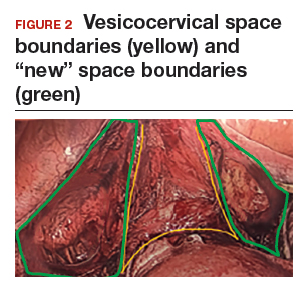

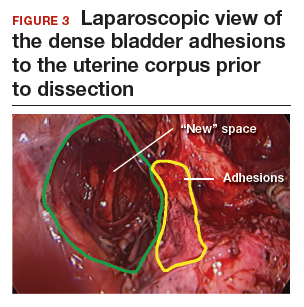

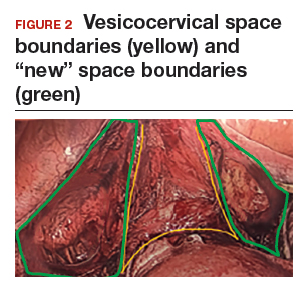

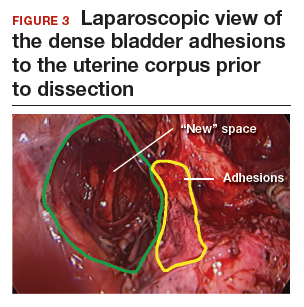

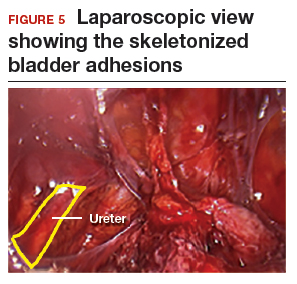

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be performed from this space. Using the previously described blunt sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, the vesicovaginal and vesicocervical space is further developed from an unscarred plane. This will separate the lowest portion of the bladder from the vagina, cervix, and uterus in a safe manner. Similar to the technique performed during a vaginal hysterectomy, this reverse motion of developing the bladder flap avoids erroneous and blind dissection through the vesicouterine adhesions (FIGURES 3–5).

Once the bladder adhesions are well delineated and separated from the uterus by the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique, it is safe to proceed with complete bladder mobilization. Sharp dissection can be used to dissect the remaining scarred bladder at its most superior attachments. Avoid the use of thermal energy to prevent heat injury to the bladder. Carefully dissect the bladder adhesions from the cervicouterine junction. Additional inferior bladder mobilization should be performed up to 3 cm past the leading edge of the cervicovaginal junction to ensure sufficient vaginal tissue for cuff closure. Note that the bladder pillars occasionally may be trapped inside a CD scar. This surgical technique could make it easier to release the pillars from inside the adhesions and penetrating into the scar.15

Continue to: Completing the surgery...

Completing the surgery

Once the bladder is freely mobilized and all adhesions have been dissected, the cervix is circumferentially amputated using monopolar cautery. The vaginal cuff can then be closed from either a laparoscopic or vaginal approach using polyglactin 910 (0-Vicryl) or barbed (V-Loc) suture in a running or interrupted fashion. Our practice uses a 1.5-cm margin depth with each suture. At the end of the surgery, routine cystoscopy is performed to verify distal ureteral patency.16 Postoperatively, we manage these patients using a fast-track, or enhanced recovery, model.17

From the Center for Special Minimally Invasive and Robotic Surgery

https://youtu.be/wgGssnd1JAo

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Case 1: TLH with development of the "new space": The technique with prior C-section

- Case 2: A straightforward case: Dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia

- Case 3: History of multiple C-sections with adhesions and fibroids

https://youtu.be/6vHamfPZhdY

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean delivery

An effective technique in challenging situations

Genitourinary injury is a common complication of hysterectomy.18 The proximity of the bladder and ureters to the field of dissection during a hysterectomy can be especially challenging when the anatomy is distorted by adhesion formation from prior surgeries. One study demonstrated a 1.3% incidence of urinary tract injuries during laparoscopic hysterectomy.6 This included 0.54% ureteral injuries, 0.71% urinary bladder injuries, and 0.06% combined bladder and ureteral injuries.6 Particularly among patients with a prior CD, the risk of bladder injury can be significantly heightened.18

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique that we described offers multiple benefits. By starting the procedure from an untouched and avascular plane, dissection into the plane of the prior adhesions can be circumvented; thus, bleeding is limited and injury to the bladder and ureters is avoided or minimized. By using blunt and sharp dissection, thermal injury and delayed necrosis can be mitigated. Finally, with bladder mobilization well below the colpotomy site, more adequate vaginal tissue is free to be incorporated into the vaginal cuff closure, thereby limiting the risk of cuff dehiscence.16

While we have found this technique effective for patients with prior cesarean deliveries, it also may be applied to any patient who has a scarred anterior cul-de-sac. This could include patients with prior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect, or endometriosis. Despite the technique being a safeguard against bladder injury, surgeons must still use care in developing the spaces to avoid ureteral injury, especially in a setting of distorted anatomy.

- Page B. Nezhat & the advent of advanced operative video-laparoscopy. In: Nezhat C. Nezhat's History of Endoscopy. Tuttlingen, Germany: Endo Press; 2011:159-179. https://laparoscopy.blogs.com/endoscopyhistory/chapter_22. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Podratz KC. Degrees of freedom: advances in gynecological and obstetric surgery. In: American College of Surgeons. Remembering Milestones and Achievements in Surgery: Inspiring Quality for a Hundred Years, 1913-2012. Tampa, FL: Faircount Media Group; 2013:113-119. http://endometriosisspecialists.com/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/Degrees-of-Freedom-Advances-in-Gynecological-and-Obstetrical-Surgery.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

- Kelley WE Jr. The evolution of laparoscopy and the revolution in surgery in the decade of the 1990s. JSLS. 2008;12:351-357.

- Tokunaga T. Video surgery expands its scope. Stanford Med. 1993/1994;11(2)12-16.

- Rooney CM, Crawford AT, Vassallo BJ, et al. Is previous cesarean section a risk for incidental cystotomy at the time of hysterectomy? A case-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2041-2044.

- Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA, Reinsch CS, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy and urinary tract injury: experience in a health maintenance organization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1278-1286.

- Sinha R, Sundaram M, Lakhotia S, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in women with previous cesarean sections. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:513-517.

- O'Hanlan KA. Cystosufflation to prevent bladder injury. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:195-197.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, et al. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1-65.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, eds. Nezhat's Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy with DVD, 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

- Nezhat C, Grace LA, Razavi GM, et al. Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:629-633.

- Nezhat C, Xie J, Aldape D, et al. Use of laparoscopic modified nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for the treatment of extensive endometriosis. Cureus. 2014;6:e159.

- Yabuki Y, Sasaki H, Hatakeyama N, et al. Discrepancies between classic anatomy and modern gynecologic surgery on pelvic connective tissue structure: harmonization of those concepts by collaborative cadaver dissection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:7-15.

- Uhlenhuth E. Problems in the Anatomy of the Pelvis: An Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Co; 1953.

- Nezhat C, Grace, L, Soliemannjad, et al. Cesarean scar defect: what is it and how should it be treated? OBG Manag. 2016;28(4):32,34,36,38-39,53.

- Nezhat C, Kennedy Burns M, Wood M, et al. Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:972-985.

- Nezhat C, Main J, Paka C, et al. Advanced gynecologic laparoscopy in a fast-track ambulatory surgery center. JSLS. 2014;18:pii:e2014.00291.

- Nezhat C, Falik R, McKinney S, et al. Pathophysiology and management of urinary tract endometriosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:359-372.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, which have revolutionized modern-day surgery, are the current standard of care for benign hysterectomies.1-4 Many surgeons use a video-laparoscopic approach, with or without robotic assistance, to perform a hysterectomy. The development of a bladder flap or vesicovaginal surgical space is a critical step for mobilizing the bladder. When properly performed, it allows for appropriate closure of the vaginal cuff while mitigating the risk of urinary bladder damage.

In patients with no prior pelvic surgeries, this vesicovaginal anatomic space is typically developed with ease. However, in patients who have had prior cesarean deliveries (CDs), the presence of vesicouterine adhesions could make this step significantly more challenging. As a result, the risk of bladder injury is higher.5-8

With the current tide of cesarean birth rates approaching 33% on a national scale, the presence of vesicouterine adhesions is commonly encountered.9 These adhesions can distort the anatomy and thereby create more difficult dissections and increase operative time, conversion to laparotomy, and inadvertent cystotomy. Such a challenge also presents an increased risk of injuring adjacent structures.

In this article, we describe an effective method of dissection that is especially useful in the setting of prior CDs. This method involves developing a "new" surgical space lateral and caudal to the vesicocervical space.

Steps in operative planning

Preoperative evaluation. A thorough preoperative evaluation should be performed for patients planning to undergo a laparoscopic hysterectomy. This includes obtaining details of their medical and surgical history. Access to prior surgical records may help to facilitate planning of the surgical approach. Previous pelvic surgery, such as CD, anterior myomectomy, cesarean scar defect repair, endometriosis treatment, or exploratory laparotomy, may predispose these patients to develop adhesions in the anterior cul-de-sac. Our method of reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be particularly efficacious in these settings.

Surgical preparation and laparoscopic port placement. In the operative suite, the patient is placed under general anesthesia and positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position.10 Sterile prep and drapes are used in the standard fashion. A urinary catheter is inserted to maintain a decompressed bladder. A uterine manipulator is inserted with good placement ensured.

Per our practice, we introduce laparoscopic ports in 4 locations. The first incision is made in the umbilicus for the introduction of a 10-mm laparoscope. Three subsequent 5-mm incisions are made in the left and right lower lateral quadrants and medially at the level of the suprapubic region.10 Upon laparoscopic entry, we perform a comprehensive survey of the abdominopelvic cavity. Adequate mobility of the uterus is confirmed.11 Any posterior uterine adhesions or endometriosis are treated appropriately.12

First step in the surgical technique: Lateral dissection

We proceed by first desiccating and cutting the round ligament laterally near the inguinal canal. This technique is carried forward in a caudal direction as the areolar tissue near the obliterated umbilical artery is expanded by the pneumoperitoneum. With a vessel sealing-cutting device, we address the attachments to the adnexa. If the ovaries are to be retained, the utero-ovarian ligament is dessicated and cut. If an oophorectomy is indicated, the infundibulopelvic ligament is dessicated and cut.

Continue to: Using the tip of the vessel sealing...

Using the tip of the vessel sealing-cutting device, the space between the anterior and posterior leaves of the broad ligament is developed and opened. A grasping forceps is then used to elevate the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and maintain medial traction. A space parallel and lateral to the cervix and bladder is then created with blunt dissection.

The inferior and medial direction of this dissection is paramount to avoid injury to nearby structures in the pelvic sidewall. Gradually, this will lead to the identification of the vesciovaginal ligament and then the vesicocervical ligament. The development of these spaces allows for the lateral and inferior displacement of the ureter. These maneuvers can mitigate ureter injury by pushing it away from the planes of dissection during the hysterectomy.

Continued traction is maintained by keeping the medial aspect of the anterior leaf of the broad ligament intact. However, the posterior leaf is dissected next, which further lateralizes the ureter. Now, with the uterine vessels fully exposed, they are thoroughly dessicated and ligated. The same procedure is then performed on the contralateral side.11 (See the box below for links to videos that demonstrate the techniques described here.)

Creating the “new” space

In the “new” space that was partially developed during the lateral dissection, blunt dissection is continued, using a sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, to extend this avascular space. This is performed bilaterally until both sides are connected from the inferior aspect of the vesicouterine adhesions, if present. This thorough dissection creates what we refer to as a “new” space11 (FIGURE 1).

Medially, the new space is bordered by the vesicocervical-vaginal ligament, also known as the bladder pillar. Its distal landmark is the bladder. The remaining intact anterior leaf of the broad ligament lies adjacent to the space anteriorly. The inner aspect of the obliterated umbilical artery neighbors it laterally. Lastly, the vesicovaginal plane’s posterior margin is the parametrium, which is the region where the ureter courses into the bladder. The paravesical space lies lateral to the obliterated umbilical ligament.

Visualization of this new space is made possible in the laparoscopic setting. The pneumoperitoneum allows for better demarcation of the space. Additionally, laparoscopic views of the anatomic spaces differ from those of the laparotomy view because of the magnification and the insufflation of carbon dioxide gas in the spaces.13,14 In our experience, approaching the surgery from the “new” space could significantly decrease the risk of genitourinary injuries in patients with anterior cul-de-sac adhesions (FIGURE 2).

Using the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique

Among patients with prior CDs, adhesions often are at the level of or superior to the prior CD scar. By creating the new space, safe dissection from a previously untouched area can be accomplished and injury to the urinary bladder can be avoided.

The reverse vesicouterine fold dissection can be performed from this space. Using the previously described blunt sweeping motion from an inferior-to-superior direction, the vesicovaginal and vesicocervical space is further developed from an unscarred plane. This will separate the lowest portion of the bladder from the vagina, cervix, and uterus in a safe manner. Similar to the technique performed during a vaginal hysterectomy, this reverse motion of developing the bladder flap avoids erroneous and blind dissection through the vesicouterine adhesions (FIGURES 3–5).

Once the bladder adhesions are well delineated and separated from the uterus by the reverse vesicouterine fold dissection technique, it is safe to proceed with complete bladder mobilization. Sharp dissection can be used to dissect the remaining scarred bladder at its most superior attachments. Avoid the use of thermal energy to prevent heat injury to the bladder. Carefully dissect the bladder adhesions from the cervicouterine junction. Additional inferior bladder mobilization should be performed up to 3 cm past the leading edge of the cervicovaginal junction to ensure sufficient vaginal tissue for cuff closure. Note that the bladder pillars occasionally may be trapped inside a CD scar. This surgical technique could make it easier to release the pillars from inside the adhesions and penetrating into the scar.15

Continue to: Completing the surgery...

Completing the surgery

Once the bladder is freely mobilized and all adhesions have been dissected, the cervix is circumferentially amputated using monopolar cautery. The vaginal cuff can then be closed from either a laparoscopic or vaginal approach using polyglactin 910 (0-Vicryl) or barbed (V-Loc) suture in a running or interrupted fashion. Our practice uses a 1.5-cm margin depth with each suture. At the end of the surgery, routine cystoscopy is performed to verify distal ureteral patency.16 Postoperatively, we manage these patients using a fast-track, or enhanced recovery, model.17

From the Center for Special Minimally Invasive and Robotic Surgery

https://youtu.be/wgGssnd1JAo

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Case 1: TLH with development of the "new space": The technique with prior C-section

- Case 2: A straightforward case: Dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia

- Case 3: History of multiple C-sections with adhesions and fibroids

https://youtu.be/6vHamfPZhdY

Reverse vesicouterine fold dissection for total laparoscopic hysterectomy after prior cesarean delivery

An effective technique in challenging situations