User login

What Makes Squamous Cell Cancers Different? Genomics May Explain

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) associated with smoking and human papillomavirus (HPV) have distinct genomic signatures, say researchers from a National Institutes of Health-supported study. That is one of the findings that may help distinguish SCCs from other cancers and point the way to new research and treatment.

The researchers used new analytic tools and data from the recently completed PanCancer Atlas to investigate similarities and differences among SCCs in the head and neck, lung, esophagus, cervix, and bladder. The PanCancer Atlas is a detailed analysis from a dataset containing molecular and clinical information on more than 10,000 tumors from 33 forms of cancer.

The researchers combined multiple platforms of genomic data from 1,400 SCC samples into integrated analyses, creating visual clusters of tumors based on genomic characteristics.

Squamous cell carcinomas had genomic features that set them apart from other cancers, the researchers found. The most common were gains or losses of the sections of certain chromosomes, making it likely that those regions harbor genes important to the development of SCCs.

The current study expands on research reported in 2014 and 2015, which compared genomic features of SCCs in head and neck cancer associated with smoking (a risk factor for head and neck cancer [HNC]) and HPV (a risk factor for cervical and some HNCs). Certain features were present in tumors associated with both, whereas others were exclusive to only 1 of the 2. The researchers also found similarities in the genomic characteristics of HNCs with lung cancers, some bladder cancers, and cervical cancer.

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) associated with smoking and human papillomavirus (HPV) have distinct genomic signatures, say researchers from a National Institutes of Health-supported study. That is one of the findings that may help distinguish SCCs from other cancers and point the way to new research and treatment.

The researchers used new analytic tools and data from the recently completed PanCancer Atlas to investigate similarities and differences among SCCs in the head and neck, lung, esophagus, cervix, and bladder. The PanCancer Atlas is a detailed analysis from a dataset containing molecular and clinical information on more than 10,000 tumors from 33 forms of cancer.

The researchers combined multiple platforms of genomic data from 1,400 SCC samples into integrated analyses, creating visual clusters of tumors based on genomic characteristics.

Squamous cell carcinomas had genomic features that set them apart from other cancers, the researchers found. The most common were gains or losses of the sections of certain chromosomes, making it likely that those regions harbor genes important to the development of SCCs.

The current study expands on research reported in 2014 and 2015, which compared genomic features of SCCs in head and neck cancer associated with smoking (a risk factor for head and neck cancer [HNC]) and HPV (a risk factor for cervical and some HNCs). Certain features were present in tumors associated with both, whereas others were exclusive to only 1 of the 2. The researchers also found similarities in the genomic characteristics of HNCs with lung cancers, some bladder cancers, and cervical cancer.

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) associated with smoking and human papillomavirus (HPV) have distinct genomic signatures, say researchers from a National Institutes of Health-supported study. That is one of the findings that may help distinguish SCCs from other cancers and point the way to new research and treatment.

The researchers used new analytic tools and data from the recently completed PanCancer Atlas to investigate similarities and differences among SCCs in the head and neck, lung, esophagus, cervix, and bladder. The PanCancer Atlas is a detailed analysis from a dataset containing molecular and clinical information on more than 10,000 tumors from 33 forms of cancer.

The researchers combined multiple platforms of genomic data from 1,400 SCC samples into integrated analyses, creating visual clusters of tumors based on genomic characteristics.

Squamous cell carcinomas had genomic features that set them apart from other cancers, the researchers found. The most common were gains or losses of the sections of certain chromosomes, making it likely that those regions harbor genes important to the development of SCCs.

The current study expands on research reported in 2014 and 2015, which compared genomic features of SCCs in head and neck cancer associated with smoking (a risk factor for head and neck cancer [HNC]) and HPV (a risk factor for cervical and some HNCs). Certain features were present in tumors associated with both, whereas others were exclusive to only 1 of the 2. The researchers also found similarities in the genomic characteristics of HNCs with lung cancers, some bladder cancers, and cervical cancer.

Giving Dexamethasone a New Lease on Life

Dexamethasone (Dex), a synthetic glucocorticoid, for years has been widely used both to treat adverse effects of antitumor agents and in direct chemotherapy regimens for hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia and lymphoma. But might it be modified to work against solid cancers as well? Researchers from Advanced Radiation Technology Institute, Medical Device Development Center, and University of Science and Technology in South Korea, suggest that ionizing radiation could produce new anticancer options from an old drug.

The researchers irradiated Dex with γ- rays to produce ionizing-radiation-irradiated.

Dex (Dex-IR), then investigated its effects on human lung cancer cells (cell lines H1650, A549, and H1299). The researchers used ionizing radiation because introducing energy into materials can produce favorable changes; irradiated materials with sufficiently high energy can decompose to yield very reactive intermediate molecules and form new ones. In this study, γ -irradiation produced “remarkable changes” in the chemical properties of dexamethasone; changes included degradation products, such as methanol vapor and carbon monoxide.

Original Dex inhibits the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells but has minimal cytotoxic effects, the researchers say. However, Dex-IR not only significantly inhibited the proliferation of NSCLC cells, but also induced apoptosis, arrested cell cycles of H1650 lung cancer cells, and significantly reduced cells’ invasiveness.

The researchers say their results “strongly suggest” a direct link between the chemical derivatives of Dex and inhibition of NSCLC cell growth. Their findings are the first evidence that γ -irradiated Dex represents a novel class of anticancer agents for lung cancer.

Lee EH, Park CH, Choi HJ, Kawala RA, Bai HW, Chung BY. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194341.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194341.

Dexamethasone (Dex), a synthetic glucocorticoid, for years has been widely used both to treat adverse effects of antitumor agents and in direct chemotherapy regimens for hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia and lymphoma. But might it be modified to work against solid cancers as well? Researchers from Advanced Radiation Technology Institute, Medical Device Development Center, and University of Science and Technology in South Korea, suggest that ionizing radiation could produce new anticancer options from an old drug.

The researchers irradiated Dex with γ- rays to produce ionizing-radiation-irradiated.

Dex (Dex-IR), then investigated its effects on human lung cancer cells (cell lines H1650, A549, and H1299). The researchers used ionizing radiation because introducing energy into materials can produce favorable changes; irradiated materials with sufficiently high energy can decompose to yield very reactive intermediate molecules and form new ones. In this study, γ -irradiation produced “remarkable changes” in the chemical properties of dexamethasone; changes included degradation products, such as methanol vapor and carbon monoxide.

Original Dex inhibits the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells but has minimal cytotoxic effects, the researchers say. However, Dex-IR not only significantly inhibited the proliferation of NSCLC cells, but also induced apoptosis, arrested cell cycles of H1650 lung cancer cells, and significantly reduced cells’ invasiveness.

The researchers say their results “strongly suggest” a direct link between the chemical derivatives of Dex and inhibition of NSCLC cell growth. Their findings are the first evidence that γ -irradiated Dex represents a novel class of anticancer agents for lung cancer.

Lee EH, Park CH, Choi HJ, Kawala RA, Bai HW, Chung BY. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194341.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194341.

Dexamethasone (Dex), a synthetic glucocorticoid, for years has been widely used both to treat adverse effects of antitumor agents and in direct chemotherapy regimens for hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia and lymphoma. But might it be modified to work against solid cancers as well? Researchers from Advanced Radiation Technology Institute, Medical Device Development Center, and University of Science and Technology in South Korea, suggest that ionizing radiation could produce new anticancer options from an old drug.

The researchers irradiated Dex with γ- rays to produce ionizing-radiation-irradiated.

Dex (Dex-IR), then investigated its effects on human lung cancer cells (cell lines H1650, A549, and H1299). The researchers used ionizing radiation because introducing energy into materials can produce favorable changes; irradiated materials with sufficiently high energy can decompose to yield very reactive intermediate molecules and form new ones. In this study, γ -irradiation produced “remarkable changes” in the chemical properties of dexamethasone; changes included degradation products, such as methanol vapor and carbon monoxide.

Original Dex inhibits the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells but has minimal cytotoxic effects, the researchers say. However, Dex-IR not only significantly inhibited the proliferation of NSCLC cells, but also induced apoptosis, arrested cell cycles of H1650 lung cancer cells, and significantly reduced cells’ invasiveness.

The researchers say their results “strongly suggest” a direct link between the chemical derivatives of Dex and inhibition of NSCLC cell growth. Their findings are the first evidence that γ -irradiated Dex represents a novel class of anticancer agents for lung cancer.

Lee EH, Park CH, Choi HJ, Kawala RA, Bai HW, Chung BY. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194341.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194341.

FDA places partial hold on trials after secondary lymphoma

The drugmaker after a pediatric patient developed a secondary T-cell lymphoma.

The Food and Drug Administration had issued a partial clinical hold in April on new enrollment of any patients with genetically defined solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Patients already enrolled who have not had disease progression can continue to receive tazemetostat.

Tazemetostat is a first-in-class EZH2 inhibitor being studied as monotherapy in phase 1 and 2 trials for certain molecularly defined solid tumors, follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, mesothelioma, and in combination studies of DLBCL and non–small cell lung cancer.

Epizyme is currently working to update informed consent, the investigator’s brochure, and study protocols, the company said in a statement.

The drugmaker after a pediatric patient developed a secondary T-cell lymphoma.

The Food and Drug Administration had issued a partial clinical hold in April on new enrollment of any patients with genetically defined solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Patients already enrolled who have not had disease progression can continue to receive tazemetostat.

Tazemetostat is a first-in-class EZH2 inhibitor being studied as monotherapy in phase 1 and 2 trials for certain molecularly defined solid tumors, follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, mesothelioma, and in combination studies of DLBCL and non–small cell lung cancer.

Epizyme is currently working to update informed consent, the investigator’s brochure, and study protocols, the company said in a statement.

The drugmaker after a pediatric patient developed a secondary T-cell lymphoma.

The Food and Drug Administration had issued a partial clinical hold in April on new enrollment of any patients with genetically defined solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Patients already enrolled who have not had disease progression can continue to receive tazemetostat.

Tazemetostat is a first-in-class EZH2 inhibitor being studied as monotherapy in phase 1 and 2 trials for certain molecularly defined solid tumors, follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, mesothelioma, and in combination studies of DLBCL and non–small cell lung cancer.

Epizyme is currently working to update informed consent, the investigator’s brochure, and study protocols, the company said in a statement.

PDPK1 could be novel target in MCL

Researchers may have found a new therapeutic approach for treating mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) by targeting 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDPK1).

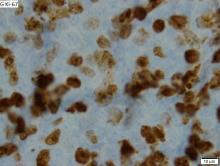

Saori Maegawa and colleagues at Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine in Japan, evaluated PDPK1 activity in patient-derived primary B-cell lymphoma cells by immunohistochemical staining of p-PDPK1Ser241 (p-PDPK1) in tissue specimens from seven patients with MCL, six patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and five patients with follicular lymphoma. All specimens were biopsied at initial diagnosis, before starting treatment.

“Our study showed that PDPK1 inhibition caused inactivation of RSK2-NTKD, as well as the decrease of total RSK2 protein, but not of AKT, in MCL-derived cells,” the researchers wrote in Experimental Hematology. “This implies that RSK2 activity is mainly regulated by PDPK1 at both the transcriptional expression and post-translational levels, but AKT activity is regulated by a signaling pathway that does not interact with a PDPK1-mediated pathway in MCL.”

If a PDPK1 inhibitor is pursued as clinical target, the researchers said careful monitoring for hyperglycemia may be required since impaired glucose metabolism is commonly seen with AKT inhibitors. Future research in MCL could also be directed toward the targeting of RSK2-NTKD, the researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Maegawa S et al. Exp Hematol. 2018 Mar;59:72-81.e2.

Researchers may have found a new therapeutic approach for treating mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) by targeting 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDPK1).

Saori Maegawa and colleagues at Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine in Japan, evaluated PDPK1 activity in patient-derived primary B-cell lymphoma cells by immunohistochemical staining of p-PDPK1Ser241 (p-PDPK1) in tissue specimens from seven patients with MCL, six patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and five patients with follicular lymphoma. All specimens were biopsied at initial diagnosis, before starting treatment.

“Our study showed that PDPK1 inhibition caused inactivation of RSK2-NTKD, as well as the decrease of total RSK2 protein, but not of AKT, in MCL-derived cells,” the researchers wrote in Experimental Hematology. “This implies that RSK2 activity is mainly regulated by PDPK1 at both the transcriptional expression and post-translational levels, but AKT activity is regulated by a signaling pathway that does not interact with a PDPK1-mediated pathway in MCL.”

If a PDPK1 inhibitor is pursued as clinical target, the researchers said careful monitoring for hyperglycemia may be required since impaired glucose metabolism is commonly seen with AKT inhibitors. Future research in MCL could also be directed toward the targeting of RSK2-NTKD, the researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Maegawa S et al. Exp Hematol. 2018 Mar;59:72-81.e2.

Researchers may have found a new therapeutic approach for treating mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) by targeting 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDPK1).

Saori Maegawa and colleagues at Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine in Japan, evaluated PDPK1 activity in patient-derived primary B-cell lymphoma cells by immunohistochemical staining of p-PDPK1Ser241 (p-PDPK1) in tissue specimens from seven patients with MCL, six patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and five patients with follicular lymphoma. All specimens were biopsied at initial diagnosis, before starting treatment.

“Our study showed that PDPK1 inhibition caused inactivation of RSK2-NTKD, as well as the decrease of total RSK2 protein, but not of AKT, in MCL-derived cells,” the researchers wrote in Experimental Hematology. “This implies that RSK2 activity is mainly regulated by PDPK1 at both the transcriptional expression and post-translational levels, but AKT activity is regulated by a signaling pathway that does not interact with a PDPK1-mediated pathway in MCL.”

If a PDPK1 inhibitor is pursued as clinical target, the researchers said careful monitoring for hyperglycemia may be required since impaired glucose metabolism is commonly seen with AKT inhibitors. Future research in MCL could also be directed toward the targeting of RSK2-NTKD, the researchers wrote.

SOURCE: Maegawa S et al. Exp Hematol. 2018 Mar;59:72-81.e2.

FROM EXPERIMENTAL HEMATOLOGY

Updated CLL guidelines incorporate a decade of advances

include new and revised recommendations based on major advances in genomics, targeted therapies, and biomarkers that have occurred since the last iteration in 2008.

The guidelines are an update from a consensus document issued a decade ago by the International Workshop on CLL, focusing on the conduct of clinical trials in patients with CLL. The new guidelines are published in Blood.

Major changes or additions include:

Molecular genetics: The updated guidelines recognize the clinical importance of specific genomic alterations/mutations on response to standard chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, including the 17p deletion and mutations in TP53.

“Therefore, the assessment of both del(17p) and TP53 mutation has prognostic and predictive value and should guide therapeutic decisions in routine practice. For clinical trials, it is recommended that molecular genetics be performed prior to treating a patient on protocol,” the guidelines state.

IGHV mutational status: The mutational status of immunoglobulin variable heavy chain (IGHV) genes has been demonstrated to offer important prognostic information, according to the guidelines authors led by Michael Hallek, MD of the University of Cologne, Germany.

Specifically, leukemia with IGHV genes without somatic mutations are associated with worse clinical outcomes, compared with leukemia with IGHV mutations. Patients with mutated IGHV and other prognostic factors such as favorable cytogenetics or minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity generally have excellent outcomes with a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, the authors noted.

Biomarkers: The guidelines call for standardization and use in prospective clinical trials of assays for serum markers such as soluble CD23, thymidine kinase, and beta-2-microglobulin. These markers have been shown in several studies to be associated with overall survival or progression-free survival, and of these markers, beta-2-microglobulin “has retained independent prognostic value in several multiparameter scores,” the guidelines state.

The authors also tip their hats to recently developed or improved prognostic scores, especially the CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI), which incorporates clinical stage, age, IGHV mutational status, beta-2-microglobulin, and del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations.

Organ function assessment: Not new, but improved in the current version of the guidelines, are recommendations for evaluation of splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and lymphadenopathy in response assessment. These recommendations were harmonized with the relevant sections of the updated lymphoma response guidelines.

Continuous therapy: The guidelines panel recommends assessment of response duration during continuous therapy with oral agents and after the end of therapy, especially after chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.

“Study protocols should provide detailed specifications of the planned time points for the assessment of the treatment response under continuous therapy. Response durations of less than six months are not considered clinically relevant,” the panel cautioned.

Response assessments for treatments with a maintenance phase should be performed at a minimum of 2 months after patients achieve their best responses.

MRD: The guidelines call for minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment in clinical trials aimed at maximizing remission depth, with emphasis on reporting the sensitivity of the MRD evaluation method used, and the type of tissue assessed.

Antiviral prophylaxis: The guidelines caution that because patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies, such as rituximab or obinutuzumab, could have reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, patients should be tested for HBV serological status before starting on an anti-CD20 agent.

“Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been reported in a few CLL patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies; therefore, infections with John Cunningham (JC) virus should be ruled out in situations of unclear neurological symptoms,” the panel recommended.

They note that patients younger than 65 treated with fludarabine-based therapy in the first line do not require routine monitoring or infection prophylaxis, due to the low reported incidence of infections in this group.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures related to the guidelines.

include new and revised recommendations based on major advances in genomics, targeted therapies, and biomarkers that have occurred since the last iteration in 2008.

The guidelines are an update from a consensus document issued a decade ago by the International Workshop on CLL, focusing on the conduct of clinical trials in patients with CLL. The new guidelines are published in Blood.

Major changes or additions include:

Molecular genetics: The updated guidelines recognize the clinical importance of specific genomic alterations/mutations on response to standard chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, including the 17p deletion and mutations in TP53.

“Therefore, the assessment of both del(17p) and TP53 mutation has prognostic and predictive value and should guide therapeutic decisions in routine practice. For clinical trials, it is recommended that molecular genetics be performed prior to treating a patient on protocol,” the guidelines state.

IGHV mutational status: The mutational status of immunoglobulin variable heavy chain (IGHV) genes has been demonstrated to offer important prognostic information, according to the guidelines authors led by Michael Hallek, MD of the University of Cologne, Germany.

Specifically, leukemia with IGHV genes without somatic mutations are associated with worse clinical outcomes, compared with leukemia with IGHV mutations. Patients with mutated IGHV and other prognostic factors such as favorable cytogenetics or minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity generally have excellent outcomes with a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, the authors noted.

Biomarkers: The guidelines call for standardization and use in prospective clinical trials of assays for serum markers such as soluble CD23, thymidine kinase, and beta-2-microglobulin. These markers have been shown in several studies to be associated with overall survival or progression-free survival, and of these markers, beta-2-microglobulin “has retained independent prognostic value in several multiparameter scores,” the guidelines state.

The authors also tip their hats to recently developed or improved prognostic scores, especially the CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI), which incorporates clinical stage, age, IGHV mutational status, beta-2-microglobulin, and del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations.

Organ function assessment: Not new, but improved in the current version of the guidelines, are recommendations for evaluation of splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and lymphadenopathy in response assessment. These recommendations were harmonized with the relevant sections of the updated lymphoma response guidelines.

Continuous therapy: The guidelines panel recommends assessment of response duration during continuous therapy with oral agents and after the end of therapy, especially after chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.

“Study protocols should provide detailed specifications of the planned time points for the assessment of the treatment response under continuous therapy. Response durations of less than six months are not considered clinically relevant,” the panel cautioned.

Response assessments for treatments with a maintenance phase should be performed at a minimum of 2 months after patients achieve their best responses.

MRD: The guidelines call for minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment in clinical trials aimed at maximizing remission depth, with emphasis on reporting the sensitivity of the MRD evaluation method used, and the type of tissue assessed.

Antiviral prophylaxis: The guidelines caution that because patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies, such as rituximab or obinutuzumab, could have reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, patients should be tested for HBV serological status before starting on an anti-CD20 agent.

“Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been reported in a few CLL patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies; therefore, infections with John Cunningham (JC) virus should be ruled out in situations of unclear neurological symptoms,” the panel recommended.

They note that patients younger than 65 treated with fludarabine-based therapy in the first line do not require routine monitoring or infection prophylaxis, due to the low reported incidence of infections in this group.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures related to the guidelines.

include new and revised recommendations based on major advances in genomics, targeted therapies, and biomarkers that have occurred since the last iteration in 2008.

The guidelines are an update from a consensus document issued a decade ago by the International Workshop on CLL, focusing on the conduct of clinical trials in patients with CLL. The new guidelines are published in Blood.

Major changes or additions include:

Molecular genetics: The updated guidelines recognize the clinical importance of specific genomic alterations/mutations on response to standard chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, including the 17p deletion and mutations in TP53.

“Therefore, the assessment of both del(17p) and TP53 mutation has prognostic and predictive value and should guide therapeutic decisions in routine practice. For clinical trials, it is recommended that molecular genetics be performed prior to treating a patient on protocol,” the guidelines state.

IGHV mutational status: The mutational status of immunoglobulin variable heavy chain (IGHV) genes has been demonstrated to offer important prognostic information, according to the guidelines authors led by Michael Hallek, MD of the University of Cologne, Germany.

Specifically, leukemia with IGHV genes without somatic mutations are associated with worse clinical outcomes, compared with leukemia with IGHV mutations. Patients with mutated IGHV and other prognostic factors such as favorable cytogenetics or minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity generally have excellent outcomes with a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, the authors noted.

Biomarkers: The guidelines call for standardization and use in prospective clinical trials of assays for serum markers such as soluble CD23, thymidine kinase, and beta-2-microglobulin. These markers have been shown in several studies to be associated with overall survival or progression-free survival, and of these markers, beta-2-microglobulin “has retained independent prognostic value in several multiparameter scores,” the guidelines state.

The authors also tip their hats to recently developed or improved prognostic scores, especially the CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI), which incorporates clinical stage, age, IGHV mutational status, beta-2-microglobulin, and del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations.

Organ function assessment: Not new, but improved in the current version of the guidelines, are recommendations for evaluation of splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and lymphadenopathy in response assessment. These recommendations were harmonized with the relevant sections of the updated lymphoma response guidelines.

Continuous therapy: The guidelines panel recommends assessment of response duration during continuous therapy with oral agents and after the end of therapy, especially after chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.

“Study protocols should provide detailed specifications of the planned time points for the assessment of the treatment response under continuous therapy. Response durations of less than six months are not considered clinically relevant,” the panel cautioned.

Response assessments for treatments with a maintenance phase should be performed at a minimum of 2 months after patients achieve their best responses.

MRD: The guidelines call for minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment in clinical trials aimed at maximizing remission depth, with emphasis on reporting the sensitivity of the MRD evaluation method used, and the type of tissue assessed.

Antiviral prophylaxis: The guidelines caution that because patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies, such as rituximab or obinutuzumab, could have reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections, patients should be tested for HBV serological status before starting on an anti-CD20 agent.

“Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been reported in a few CLL patients treated with anti-CD20 antibodies; therefore, infections with John Cunningham (JC) virus should be ruled out in situations of unclear neurological symptoms,” the panel recommended.

They note that patients younger than 65 treated with fludarabine-based therapy in the first line do not require routine monitoring or infection prophylaxis, due to the low reported incidence of infections in this group.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures related to the guidelines.

FROM BLOOD

Clinical Puzzle: Lung Cancer or Hodgkin Lymphoma?

Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma have a 15% to 40% likelihood of pulmonary involvement, such as a solitary lung mass or cavitary lung lesion. But clinicians at Bassett Healthcare in Cooperstown, New York, were faced with a rare case of another presentation: an endobronchial obstructing mass.

The patient, a 40-year-old man, reported having had cough, fatigue, and progressive weight loss (despite a good appetite) for 8 months. Because he had a history of smoking, he was treated for bronchitis, but the cough worsened. He had no fever, night sweats, dyspnea, or chest pain (common features of Hodgkin lymphoma).

Auscultation revealed clear lungs, with no crackles or wheeze, and no dullness to percussion. Blood work was negative except for eosinophilia. A subsequent chest radiograph showed an irregular left hilar lung opacity. A computer tomography scan showed a cavitary consolidation of the left upper lobe of the lung. Fiber-optic bronchoscopy with tissue from the endobronchial mass indicated an obstructing lesion in the left upper lobe bronchus. The clinicians suspected lung cancer.

However, they also found inflammatory cells, and immunohistochemistry revealed findings consistent with Hodgkin lymphoma. The clinicians started the patient on chemotherapy. After 6 cycles, his symptoms resolved. Follow-up at 8 months showed no clinical evidence of recurrence.

As the clinicians found out, radiologically, Hodgkin lymphoma can mimic lung cancer. They advise histopathologic diagnosis for a patient presenting with lung mass.

Source:

Abid H, Khan J, Lone N. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. pii: bcr-2017-223809.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223809.

Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma have a 15% to 40% likelihood of pulmonary involvement, such as a solitary lung mass or cavitary lung lesion. But clinicians at Bassett Healthcare in Cooperstown, New York, were faced with a rare case of another presentation: an endobronchial obstructing mass.

The patient, a 40-year-old man, reported having had cough, fatigue, and progressive weight loss (despite a good appetite) for 8 months. Because he had a history of smoking, he was treated for bronchitis, but the cough worsened. He had no fever, night sweats, dyspnea, or chest pain (common features of Hodgkin lymphoma).

Auscultation revealed clear lungs, with no crackles or wheeze, and no dullness to percussion. Blood work was negative except for eosinophilia. A subsequent chest radiograph showed an irregular left hilar lung opacity. A computer tomography scan showed a cavitary consolidation of the left upper lobe of the lung. Fiber-optic bronchoscopy with tissue from the endobronchial mass indicated an obstructing lesion in the left upper lobe bronchus. The clinicians suspected lung cancer.

However, they also found inflammatory cells, and immunohistochemistry revealed findings consistent with Hodgkin lymphoma. The clinicians started the patient on chemotherapy. After 6 cycles, his symptoms resolved. Follow-up at 8 months showed no clinical evidence of recurrence.

As the clinicians found out, radiologically, Hodgkin lymphoma can mimic lung cancer. They advise histopathologic diagnosis for a patient presenting with lung mass.

Source:

Abid H, Khan J, Lone N. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. pii: bcr-2017-223809.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223809.

Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma have a 15% to 40% likelihood of pulmonary involvement, such as a solitary lung mass or cavitary lung lesion. But clinicians at Bassett Healthcare in Cooperstown, New York, were faced with a rare case of another presentation: an endobronchial obstructing mass.

The patient, a 40-year-old man, reported having had cough, fatigue, and progressive weight loss (despite a good appetite) for 8 months. Because he had a history of smoking, he was treated for bronchitis, but the cough worsened. He had no fever, night sweats, dyspnea, or chest pain (common features of Hodgkin lymphoma).

Auscultation revealed clear lungs, with no crackles or wheeze, and no dullness to percussion. Blood work was negative except for eosinophilia. A subsequent chest radiograph showed an irregular left hilar lung opacity. A computer tomography scan showed a cavitary consolidation of the left upper lobe of the lung. Fiber-optic bronchoscopy with tissue from the endobronchial mass indicated an obstructing lesion in the left upper lobe bronchus. The clinicians suspected lung cancer.

However, they also found inflammatory cells, and immunohistochemistry revealed findings consistent with Hodgkin lymphoma. The clinicians started the patient on chemotherapy. After 6 cycles, his symptoms resolved. Follow-up at 8 months showed no clinical evidence of recurrence.

As the clinicians found out, radiologically, Hodgkin lymphoma can mimic lung cancer. They advise histopathologic diagnosis for a patient presenting with lung mass.

Source:

Abid H, Khan J, Lone N. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. pii: bcr-2017-223809.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223809.

FDA approves new option in Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

The Food and Drug Administration has approved brentuximab vedotin, in combination with chemotherapy, for previously untreated adults with stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

The drug, which is marketed by Seattle Genetics as Adcetris, is already approved in classical Hodgkin lymphoma after relapse and after stem cell transplant when the patient is at risk of relapse or progression. The drug is also approved to treat both systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and primary cutaneous ALCL after failure on other treatments.

The modified 2-year progression-free survival in the trial was 82.1% for patients receiving brentuximab plus AVD versus 77.2% for ABVD (P = .03), a 23% relative risk reduction (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:331-44).

Common side effects of brentuximab vedotin include neutropenia, anemia, peripheral neuropathy, nausea, fatigue, constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, and pyrexia. The drug carries a boxed warning highlighting the risk of John Cunningham virus infection resulting in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved brentuximab vedotin, in combination with chemotherapy, for previously untreated adults with stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

The drug, which is marketed by Seattle Genetics as Adcetris, is already approved in classical Hodgkin lymphoma after relapse and after stem cell transplant when the patient is at risk of relapse or progression. The drug is also approved to treat both systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and primary cutaneous ALCL after failure on other treatments.

The modified 2-year progression-free survival in the trial was 82.1% for patients receiving brentuximab plus AVD versus 77.2% for ABVD (P = .03), a 23% relative risk reduction (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:331-44).

Common side effects of brentuximab vedotin include neutropenia, anemia, peripheral neuropathy, nausea, fatigue, constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, and pyrexia. The drug carries a boxed warning highlighting the risk of John Cunningham virus infection resulting in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved brentuximab vedotin, in combination with chemotherapy, for previously untreated adults with stage III or IV classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

The drug, which is marketed by Seattle Genetics as Adcetris, is already approved in classical Hodgkin lymphoma after relapse and after stem cell transplant when the patient is at risk of relapse or progression. The drug is also approved to treat both systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and primary cutaneous ALCL after failure on other treatments.

The modified 2-year progression-free survival in the trial was 82.1% for patients receiving brentuximab plus AVD versus 77.2% for ABVD (P = .03), a 23% relative risk reduction (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:331-44).

Common side effects of brentuximab vedotin include neutropenia, anemia, peripheral neuropathy, nausea, fatigue, constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, and pyrexia. The drug carries a boxed warning highlighting the risk of John Cunningham virus infection resulting in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

More evidence links increased BMI to higher multiple myeloma risk

A high body mass index in both early and later adulthood increases the risk for developing multiple myeloma (MM), according to a prospective analysis.

“This association did not significantly differ by gender but was nonetheless slightly stronger in men,” wrote Catherine R. Marinac, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and her colleagues. “MM risk was significantly positively associated with weight change and suggestive of a positive association for change in BMI since young adulthood. In contrast, we did not observe statistically significant associations of cumulative average physical activity or walking with MM risk.”

Dr. Marinac and her associates analyzed participants from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), and the Women’s Health Study (WHS) with a pooled total of 575 MM cases and more than 5 million person-years of follow-up. From all of those databases, a combined baseline total of 49,374 men and 153,260 women were included in the analyses. Participants in all three of the cohorts were predominately white.

Each participant was required to report height and weight on a baseline questionnaire and updated weights on subsequent questionnaires. Using that height and weight information, the researchers calculated BMI. Physical activity also was reported using questionnaires, beginning in 1986 in the HPFS and NHS groups and at baseline for WHS, with all groups providing updates every 2-4 years. The researchers used the physical activity information to calculate the total metabolic equivalent (MET) hours of all activity and of walking per week.

Dr. Marinac and her team identified a total of 205 men from the HPFS cohort and 370 women (325 NHS, 45 WHS) with confirmed diagnoses of MM. The BMIs of those participants ranged from 23.8-25.8 kg/m2 at baseline and from 21.3-23.0 kg/m2 in young adulthood. Across all cohorts, each 5 kg/m2 increase in cumulative average adult BMI significantly increased the risk of MM by 17% (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.29).

In addition, the MM risk rose almost 30% for every 5 kg/m2 increase in young adult BMI (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.12-1.47). Increased risk was not strictly related to changes in BMI but to incremental weight gain since young adulthood. (pooled HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; P = 0.03).

The study confirmed correlations between weight gain and increased MM risk, however, it also had certain limitations. For example, much of the data concerning weight, height, and physical activity were all self-reported. Another limitation is the sociodemographic heterogeneity of the study population.

Despite those limitations, Dr. Marinac emphasized that the study results add to evidence concerning weight gain and MM risk.

“Our findings support the growing body of literature demonstrating that a high BMI both early and later in adulthood is associated with the risk of MM, and suggest that maintaining a healthy body weight throughout life may be an important component to a much-needed MM prevention strategy,” wrote Dr. Marinac, who also is affiliated with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, also in Boston.

“Further larger-scale studies aimed at clarifying the influence of obesity timing and duration and at directly evaluating the role of weight loss, ideally conducted in diverse prospective study populations and in [monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance] patients, will be important for elaborating the role of weight maintenance in MM prevention and for identifying high risk subgroups of patients that may benefit from weight loss.”

None of the researchers had competing financial interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Marinac CR et al. Br J Cancer. 2018 Mar 12. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0010-4.

A high body mass index in both early and later adulthood increases the risk for developing multiple myeloma (MM), according to a prospective analysis.

“This association did not significantly differ by gender but was nonetheless slightly stronger in men,” wrote Catherine R. Marinac, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and her colleagues. “MM risk was significantly positively associated with weight change and suggestive of a positive association for change in BMI since young adulthood. In contrast, we did not observe statistically significant associations of cumulative average physical activity or walking with MM risk.”

Dr. Marinac and her associates analyzed participants from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), and the Women’s Health Study (WHS) with a pooled total of 575 MM cases and more than 5 million person-years of follow-up. From all of those databases, a combined baseline total of 49,374 men and 153,260 women were included in the analyses. Participants in all three of the cohorts were predominately white.

Each participant was required to report height and weight on a baseline questionnaire and updated weights on subsequent questionnaires. Using that height and weight information, the researchers calculated BMI. Physical activity also was reported using questionnaires, beginning in 1986 in the HPFS and NHS groups and at baseline for WHS, with all groups providing updates every 2-4 years. The researchers used the physical activity information to calculate the total metabolic equivalent (MET) hours of all activity and of walking per week.

Dr. Marinac and her team identified a total of 205 men from the HPFS cohort and 370 women (325 NHS, 45 WHS) with confirmed diagnoses of MM. The BMIs of those participants ranged from 23.8-25.8 kg/m2 at baseline and from 21.3-23.0 kg/m2 in young adulthood. Across all cohorts, each 5 kg/m2 increase in cumulative average adult BMI significantly increased the risk of MM by 17% (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.29).

In addition, the MM risk rose almost 30% for every 5 kg/m2 increase in young adult BMI (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.12-1.47). Increased risk was not strictly related to changes in BMI but to incremental weight gain since young adulthood. (pooled HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; P = 0.03).

The study confirmed correlations between weight gain and increased MM risk, however, it also had certain limitations. For example, much of the data concerning weight, height, and physical activity were all self-reported. Another limitation is the sociodemographic heterogeneity of the study population.

Despite those limitations, Dr. Marinac emphasized that the study results add to evidence concerning weight gain and MM risk.

“Our findings support the growing body of literature demonstrating that a high BMI both early and later in adulthood is associated with the risk of MM, and suggest that maintaining a healthy body weight throughout life may be an important component to a much-needed MM prevention strategy,” wrote Dr. Marinac, who also is affiliated with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, also in Boston.

“Further larger-scale studies aimed at clarifying the influence of obesity timing and duration and at directly evaluating the role of weight loss, ideally conducted in diverse prospective study populations and in [monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance] patients, will be important for elaborating the role of weight maintenance in MM prevention and for identifying high risk subgroups of patients that may benefit from weight loss.”

None of the researchers had competing financial interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Marinac CR et al. Br J Cancer. 2018 Mar 12. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0010-4.

A high body mass index in both early and later adulthood increases the risk for developing multiple myeloma (MM), according to a prospective analysis.

“This association did not significantly differ by gender but was nonetheless slightly stronger in men,” wrote Catherine R. Marinac, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and her colleagues. “MM risk was significantly positively associated with weight change and suggestive of a positive association for change in BMI since young adulthood. In contrast, we did not observe statistically significant associations of cumulative average physical activity or walking with MM risk.”

Dr. Marinac and her associates analyzed participants from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), and the Women’s Health Study (WHS) with a pooled total of 575 MM cases and more than 5 million person-years of follow-up. From all of those databases, a combined baseline total of 49,374 men and 153,260 women were included in the analyses. Participants in all three of the cohorts were predominately white.

Each participant was required to report height and weight on a baseline questionnaire and updated weights on subsequent questionnaires. Using that height and weight information, the researchers calculated BMI. Physical activity also was reported using questionnaires, beginning in 1986 in the HPFS and NHS groups and at baseline for WHS, with all groups providing updates every 2-4 years. The researchers used the physical activity information to calculate the total metabolic equivalent (MET) hours of all activity and of walking per week.

Dr. Marinac and her team identified a total of 205 men from the HPFS cohort and 370 women (325 NHS, 45 WHS) with confirmed diagnoses of MM. The BMIs of those participants ranged from 23.8-25.8 kg/m2 at baseline and from 21.3-23.0 kg/m2 in young adulthood. Across all cohorts, each 5 kg/m2 increase in cumulative average adult BMI significantly increased the risk of MM by 17% (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.29).

In addition, the MM risk rose almost 30% for every 5 kg/m2 increase in young adult BMI (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.12-1.47). Increased risk was not strictly related to changes in BMI but to incremental weight gain since young adulthood. (pooled HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; P = 0.03).

The study confirmed correlations between weight gain and increased MM risk, however, it also had certain limitations. For example, much of the data concerning weight, height, and physical activity were all self-reported. Another limitation is the sociodemographic heterogeneity of the study population.

Despite those limitations, Dr. Marinac emphasized that the study results add to evidence concerning weight gain and MM risk.

“Our findings support the growing body of literature demonstrating that a high BMI both early and later in adulthood is associated with the risk of MM, and suggest that maintaining a healthy body weight throughout life may be an important component to a much-needed MM prevention strategy,” wrote Dr. Marinac, who also is affiliated with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, also in Boston.

“Further larger-scale studies aimed at clarifying the influence of obesity timing and duration and at directly evaluating the role of weight loss, ideally conducted in diverse prospective study populations and in [monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance] patients, will be important for elaborating the role of weight maintenance in MM prevention and for identifying high risk subgroups of patients that may benefit from weight loss.”

None of the researchers had competing financial interests to disclose.

SOURCE: Marinac CR et al. Br J Cancer. 2018 Mar 12. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0010-4.

FROM BRITISH JOURNAL OF CANCER

Key clinical point: Moderate increases in body mass index (BMI) can dramatically increase the risk of developing multiple myeloma (MM).

Major finding: Each 5 kg/m2 increase in cumulative average adult BMI significantly increased the risk of MM by 17%.

Study details: Prospective analysis of 49,374 men and 153,260 women from three databases.

Disclosures: None of the researchers had competing financial interests to disclose.

Source: Marinac CR et al. Br J Cancer. 2018 Mar 12. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0010-4.

In myeloma, third ASCT is a viable option

A third autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is feasible and provides clinical benefit to patients with relapsed multiple myeloma, according to findings from a retrospective study.

The benefits appear to be most pronounced in patients who had a long duration of response to the previous ASCT, the researchers wrote in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“A salvage third ASCT is of value for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma,” Laurent Garderet, MD, of the department of hematology, Hôpital Saint Antoine, Paris, and coauthors wrote in the report.

A third transplantation is most commonly used in patients who relapse following tandem ASCT. Less often, it is done in patients who receive upfront ASCT, relapse, undergo a second ASCT, and relapse again.

“The first scenario gives much better results, due in part to a better remission status at the third ASCT with no signs of increased [second primary malignancy],” the researchers wrote.

In that group, median overall survival was greater than 5 years if the relapse occurred 3 years or more after the initial tandem ASCT, study results show.

The retrospective analysis, based on European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation data, included 570 patients who had undergone a third ASCT between 1997 and 2010. Of that group, 482 patients (81%) received the third transplantation after tandem ASCT and subsequent relapse, and 88 (15%) received it after second relapse.

After third ASCT, overall survival was 33 months in the larger tandem transplant group with 61 months of follow-up, and 15 months in the smaller group of patients who received two salvage ASCTs after 48 months of follow-up.

Median progression-free survival was 13 and 8 months for the tandem ASCT and two-salvage–ASCT groups, respectively, while 100-day nonrelapse mortality was 4% and 7%, respectively.

For both groups, better outcomes were associated with longer duration of remission after the second ASCT, the researchers reported.

Moreover, the time from second ASCT to relapse was the only favorable prognostic factor associated with survival after third ASCT in a multivariate analysis of the patients who relapsed following tandem transplant. The hazard ratio for relapse occurring between 18 and 36 months vs. within 18 months was 0.62 (95% confidence interval, 0.47-0.82; P = .01); for relapse after 36 months, the HR was 0.35 (95% CI, 0.25-0.49; P less than .001).

The researchers acknowledged that, beyond transplant, treatment of myeloma has changed substantially in recent years and could change the clinical picture for patients undergoing a third ASCT.

“The availability of novel agents may further improve the response to a third ASCT, rather than impairing its usefulness in the salvage setting, by enhancing the depth of response before ASCT, which could result in improved durability of the outcome,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures related to this study.

SOURCE: Garderet L et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.035.

A third autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is feasible and provides clinical benefit to patients with relapsed multiple myeloma, according to findings from a retrospective study.

The benefits appear to be most pronounced in patients who had a long duration of response to the previous ASCT, the researchers wrote in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“A salvage third ASCT is of value for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma,” Laurent Garderet, MD, of the department of hematology, Hôpital Saint Antoine, Paris, and coauthors wrote in the report.

A third transplantation is most commonly used in patients who relapse following tandem ASCT. Less often, it is done in patients who receive upfront ASCT, relapse, undergo a second ASCT, and relapse again.

“The first scenario gives much better results, due in part to a better remission status at the third ASCT with no signs of increased [second primary malignancy],” the researchers wrote.

In that group, median overall survival was greater than 5 years if the relapse occurred 3 years or more after the initial tandem ASCT, study results show.

The retrospective analysis, based on European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation data, included 570 patients who had undergone a third ASCT between 1997 and 2010. Of that group, 482 patients (81%) received the third transplantation after tandem ASCT and subsequent relapse, and 88 (15%) received it after second relapse.

After third ASCT, overall survival was 33 months in the larger tandem transplant group with 61 months of follow-up, and 15 months in the smaller group of patients who received two salvage ASCTs after 48 months of follow-up.

Median progression-free survival was 13 and 8 months for the tandem ASCT and two-salvage–ASCT groups, respectively, while 100-day nonrelapse mortality was 4% and 7%, respectively.

For both groups, better outcomes were associated with longer duration of remission after the second ASCT, the researchers reported.

Moreover, the time from second ASCT to relapse was the only favorable prognostic factor associated with survival after third ASCT in a multivariate analysis of the patients who relapsed following tandem transplant. The hazard ratio for relapse occurring between 18 and 36 months vs. within 18 months was 0.62 (95% confidence interval, 0.47-0.82; P = .01); for relapse after 36 months, the HR was 0.35 (95% CI, 0.25-0.49; P less than .001).

The researchers acknowledged that, beyond transplant, treatment of myeloma has changed substantially in recent years and could change the clinical picture for patients undergoing a third ASCT.

“The availability of novel agents may further improve the response to a third ASCT, rather than impairing its usefulness in the salvage setting, by enhancing the depth of response before ASCT, which could result in improved durability of the outcome,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures related to this study.

SOURCE: Garderet L et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.035.

A third autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is feasible and provides clinical benefit to patients with relapsed multiple myeloma, according to findings from a retrospective study.

The benefits appear to be most pronounced in patients who had a long duration of response to the previous ASCT, the researchers wrote in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“A salvage third ASCT is of value for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma,” Laurent Garderet, MD, of the department of hematology, Hôpital Saint Antoine, Paris, and coauthors wrote in the report.

A third transplantation is most commonly used in patients who relapse following tandem ASCT. Less often, it is done in patients who receive upfront ASCT, relapse, undergo a second ASCT, and relapse again.

“The first scenario gives much better results, due in part to a better remission status at the third ASCT with no signs of increased [second primary malignancy],” the researchers wrote.

In that group, median overall survival was greater than 5 years if the relapse occurred 3 years or more after the initial tandem ASCT, study results show.

The retrospective analysis, based on European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation data, included 570 patients who had undergone a third ASCT between 1997 and 2010. Of that group, 482 patients (81%) received the third transplantation after tandem ASCT and subsequent relapse, and 88 (15%) received it after second relapse.

After third ASCT, overall survival was 33 months in the larger tandem transplant group with 61 months of follow-up, and 15 months in the smaller group of patients who received two salvage ASCTs after 48 months of follow-up.

Median progression-free survival was 13 and 8 months for the tandem ASCT and two-salvage–ASCT groups, respectively, while 100-day nonrelapse mortality was 4% and 7%, respectively.

For both groups, better outcomes were associated with longer duration of remission after the second ASCT, the researchers reported.

Moreover, the time from second ASCT to relapse was the only favorable prognostic factor associated with survival after third ASCT in a multivariate analysis of the patients who relapsed following tandem transplant. The hazard ratio for relapse occurring between 18 and 36 months vs. within 18 months was 0.62 (95% confidence interval, 0.47-0.82; P = .01); for relapse after 36 months, the HR was 0.35 (95% CI, 0.25-0.49; P less than .001).

The researchers acknowledged that, beyond transplant, treatment of myeloma has changed substantially in recent years and could change the clinical picture for patients undergoing a third ASCT.

“The availability of novel agents may further improve the response to a third ASCT, rather than impairing its usefulness in the salvage setting, by enhancing the depth of response before ASCT, which could result in improved durability of the outcome,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures related to this study.

SOURCE: Garderet L et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.035.

FROM BIOLOGY OF BLOOD AND MARROW TRANSPLANTATION

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Relapse-free interval was a favorable prognostic factor and significantly correlated with overall survival (P less than .001) in patients who underwent a third ASCT.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation data including 570 patients who had undergone a third ASCT between 1997 and 2010.

Disclosures: The study authors reported having no financial disclosures related to the study.

Source: Garderet L et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.035.

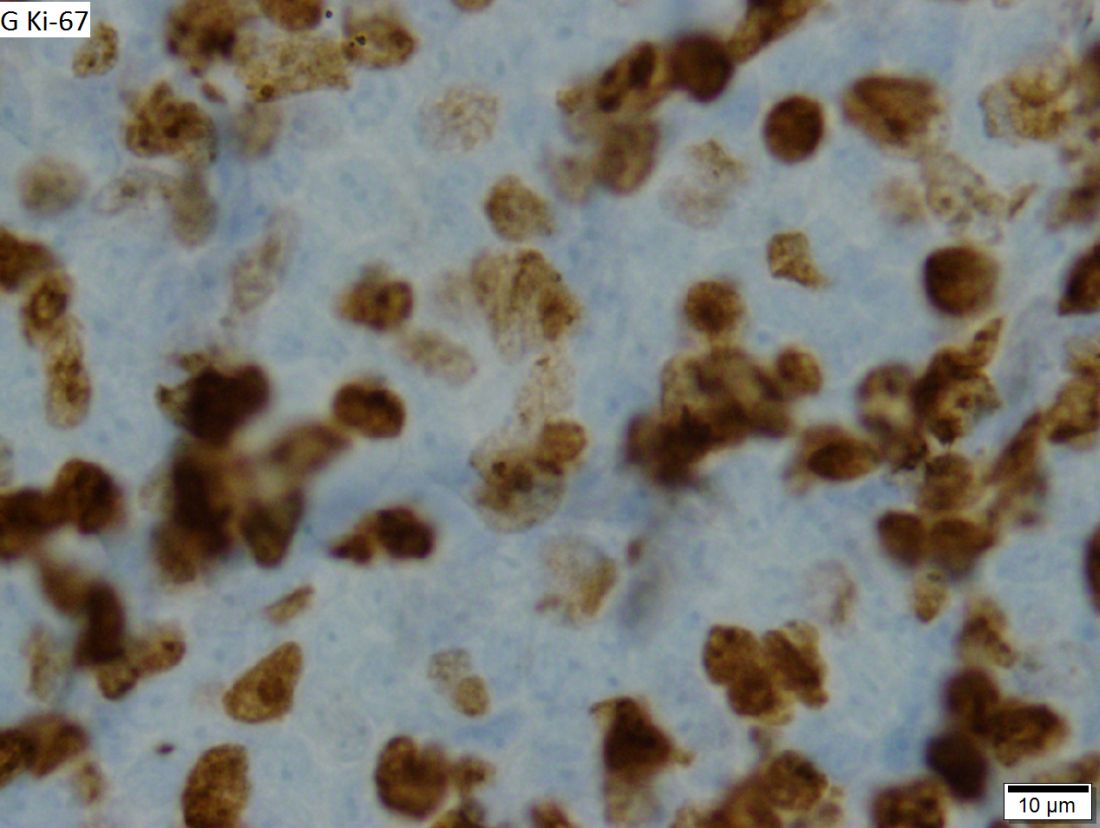

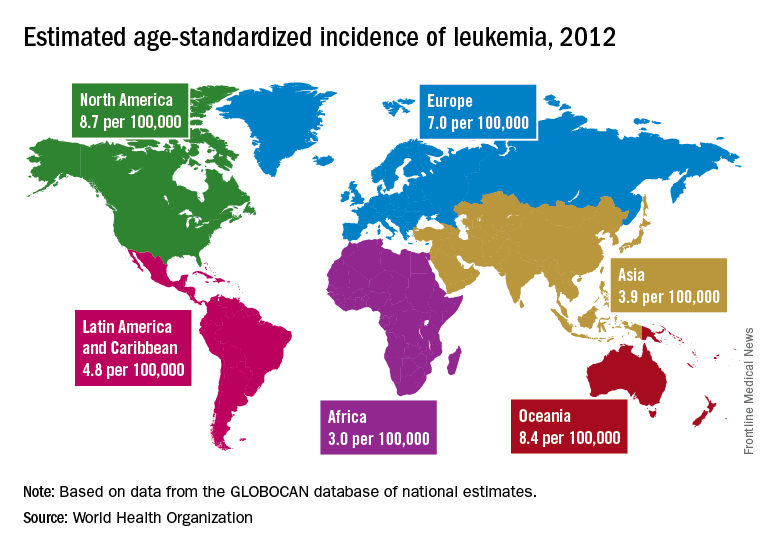

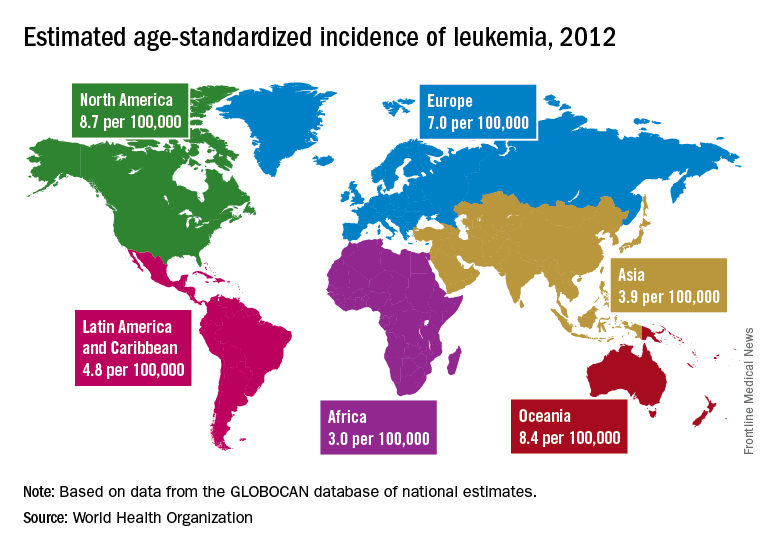

A global snapshot of leukemia incidence

, according to an analysis of World Health Organization cancer databases.

Incidence also is generally higher in males, with a global male to female ratio of 1.4. For men, the highest regional leukemia rate – estimated at 11.3 per 100,000 population for 2012 – was found in Australia and New Zealand, with northern America (the United States and Canada) next at 10.5 per 100,000. Australia/New Zealand and northern America had the highest rate for women at 7.2 per 100,000, followed by western Europe and northern Europe at 6.0 per 100,000, reported Adalberto Miranda-Filho, PhD, of the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and his associates.

The lowest regional rates for women were found in western Africa (1.2 per 100,000), middle Africa (1.8), and Micronesia/Polynesia (2.1). For men, leukemia incidence was lowest in western Africa (1.4 per 100,000), middle Africa (2.6), and south-central Asia (3.4), according to data from the WHO’s GLOBOCAN database. The report was published in The Lancet Haematology.

Estimates for leukemia subtypes in 2003-2007 – calculated for 54 countries, not regions – also showed a great deal of variation. For acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Ecuador had the highest rates for both males (2.8 per 100,000) and females (3.3), with high rates seen in Costa Rica, Columbia, and Cyprus. Rates in the United States were near the top: 2.1 for males and 1.6 for females. Rates were lowest for men in Jamaica (0.4) and Serbia (0.6) and for women in India (0.5) and Serbia and Cuba (0.6), Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

Incidence rates for acute myeloid leukemia were highest in Australia for men (2.8 per 100,000) and Austria for women (2.2), with the United States near the top for both men (2.6) and women (1.9). The lowest rates occurred in Cuba and Egypt for men (0.9 per 100,000) and Cuba for women (0.4), data from the WHO’s Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume X show.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia incidence was highest for men in Canada (4.5 per 100,000), Ireland and Lithuania (4.4), and Slovakia (4.3). The incidence was highest for women in Lithuania (2.5), Canada (2.3), and Slovakia and Denmark (2.1). Incidence in the United States was 3.5 for men and 1.8 for women. At the other end of the scale, the lowest rates for both men and women were in Japan and Malaysia (0.1), the investigators’ analysis showed.

Chronic myeloid leukemia rates were the lowest of the subtypes, and Tunisia was the lowest for men at 0.4 per 100,000 and tied for lowest with Serbia, Slovenia, and Puerto Rico for women at 0.3. Incidence was highest for men in Australia at 1.8 per 100,000 and highest for women in Uruguay at 1.1. Rates in the United States were 1.3 for men and 0.8 for women, Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

“The higher incidence of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in parts of South America, as well as of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in populations across North America and Oceania, alongside a lower incidence in Asia, might be important markers for further epidemiological study, and a means to better understand the underlying factors to support future cancer prevention strategies,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Miranda-Filho A et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e14-24.

, according to an analysis of World Health Organization cancer databases.

Incidence also is generally higher in males, with a global male to female ratio of 1.4. For men, the highest regional leukemia rate – estimated at 11.3 per 100,000 population for 2012 – was found in Australia and New Zealand, with northern America (the United States and Canada) next at 10.5 per 100,000. Australia/New Zealand and northern America had the highest rate for women at 7.2 per 100,000, followed by western Europe and northern Europe at 6.0 per 100,000, reported Adalberto Miranda-Filho, PhD, of the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and his associates.

The lowest regional rates for women were found in western Africa (1.2 per 100,000), middle Africa (1.8), and Micronesia/Polynesia (2.1). For men, leukemia incidence was lowest in western Africa (1.4 per 100,000), middle Africa (2.6), and south-central Asia (3.4), according to data from the WHO’s GLOBOCAN database. The report was published in The Lancet Haematology.

Estimates for leukemia subtypes in 2003-2007 – calculated for 54 countries, not regions – also showed a great deal of variation. For acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Ecuador had the highest rates for both males (2.8 per 100,000) and females (3.3), with high rates seen in Costa Rica, Columbia, and Cyprus. Rates in the United States were near the top: 2.1 for males and 1.6 for females. Rates were lowest for men in Jamaica (0.4) and Serbia (0.6) and for women in India (0.5) and Serbia and Cuba (0.6), Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

Incidence rates for acute myeloid leukemia were highest in Australia for men (2.8 per 100,000) and Austria for women (2.2), with the United States near the top for both men (2.6) and women (1.9). The lowest rates occurred in Cuba and Egypt for men (0.9 per 100,000) and Cuba for women (0.4), data from the WHO’s Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume X show.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia incidence was highest for men in Canada (4.5 per 100,000), Ireland and Lithuania (4.4), and Slovakia (4.3). The incidence was highest for women in Lithuania (2.5), Canada (2.3), and Slovakia and Denmark (2.1). Incidence in the United States was 3.5 for men and 1.8 for women. At the other end of the scale, the lowest rates for both men and women were in Japan and Malaysia (0.1), the investigators’ analysis showed.

Chronic myeloid leukemia rates were the lowest of the subtypes, and Tunisia was the lowest for men at 0.4 per 100,000 and tied for lowest with Serbia, Slovenia, and Puerto Rico for women at 0.3. Incidence was highest for men in Australia at 1.8 per 100,000 and highest for women in Uruguay at 1.1. Rates in the United States were 1.3 for men and 0.8 for women, Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

“The higher incidence of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in parts of South America, as well as of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in populations across North America and Oceania, alongside a lower incidence in Asia, might be important markers for further epidemiological study, and a means to better understand the underlying factors to support future cancer prevention strategies,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Miranda-Filho A et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e14-24.

, according to an analysis of World Health Organization cancer databases.

Incidence also is generally higher in males, with a global male to female ratio of 1.4. For men, the highest regional leukemia rate – estimated at 11.3 per 100,000 population for 2012 – was found in Australia and New Zealand, with northern America (the United States and Canada) next at 10.5 per 100,000. Australia/New Zealand and northern America had the highest rate for women at 7.2 per 100,000, followed by western Europe and northern Europe at 6.0 per 100,000, reported Adalberto Miranda-Filho, PhD, of the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and his associates.

The lowest regional rates for women were found in western Africa (1.2 per 100,000), middle Africa (1.8), and Micronesia/Polynesia (2.1). For men, leukemia incidence was lowest in western Africa (1.4 per 100,000), middle Africa (2.6), and south-central Asia (3.4), according to data from the WHO’s GLOBOCAN database. The report was published in The Lancet Haematology.

Estimates for leukemia subtypes in 2003-2007 – calculated for 54 countries, not regions – also showed a great deal of variation. For acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Ecuador had the highest rates for both males (2.8 per 100,000) and females (3.3), with high rates seen in Costa Rica, Columbia, and Cyprus. Rates in the United States were near the top: 2.1 for males and 1.6 for females. Rates were lowest for men in Jamaica (0.4) and Serbia (0.6) and for women in India (0.5) and Serbia and Cuba (0.6), Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

Incidence rates for acute myeloid leukemia were highest in Australia for men (2.8 per 100,000) and Austria for women (2.2), with the United States near the top for both men (2.6) and women (1.9). The lowest rates occurred in Cuba and Egypt for men (0.9 per 100,000) and Cuba for women (0.4), data from the WHO’s Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume X show.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia incidence was highest for men in Canada (4.5 per 100,000), Ireland and Lithuania (4.4), and Slovakia (4.3). The incidence was highest for women in Lithuania (2.5), Canada (2.3), and Slovakia and Denmark (2.1). Incidence in the United States was 3.5 for men and 1.8 for women. At the other end of the scale, the lowest rates for both men and women were in Japan and Malaysia (0.1), the investigators’ analysis showed.

Chronic myeloid leukemia rates were the lowest of the subtypes, and Tunisia was the lowest for men at 0.4 per 100,000 and tied for lowest with Serbia, Slovenia, and Puerto Rico for women at 0.3. Incidence was highest for men in Australia at 1.8 per 100,000 and highest for women in Uruguay at 1.1. Rates in the United States were 1.3 for men and 0.8 for women, Dr. Miranda-Filho and his associates said.

“The higher incidence of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in parts of South America, as well as of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in populations across North America and Oceania, alongside a lower incidence in Asia, might be important markers for further epidemiological study, and a means to better understand the underlying factors to support future cancer prevention strategies,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Miranda-Filho A et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e14-24.

FROM THE LANCET HAEMATOLOGY