User login

Hematology and Oncology Federal Health Data Trends (FULL)

Cancer research is a high priority for the DoD and especially for the VA. Researchers in both agencies played an important role in the early stages of the Cancer Moonshot. As part of this initiative, the VA, DoD, and National Cancer Institute joined forces in the Applied Proteogenomics Organizational Learning and Outcomes (APOLLO) project to develop a system to quickly identify unique targets and pathways of cancer for better interventions.

The VA also will provide access to the Million Veteran Program database, and > 20 years of electronic health records data for analysis using the U.S. Department of Energy’s advanced computer systems. The enhanced computational infrastructure provided by the departments will facilitate new studies of cancer genomics. The research will begin with prostate cancer, and it is hoped that the project will help researchers distinguish between those prostate cancers that require aggressive management and the more benign cancers that are less likely to progress.

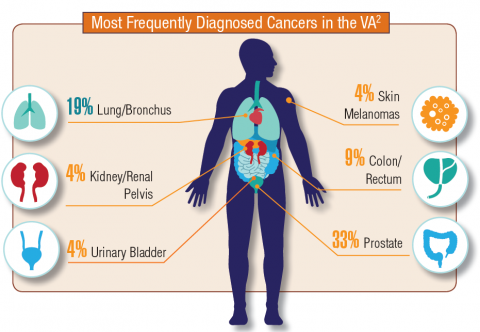

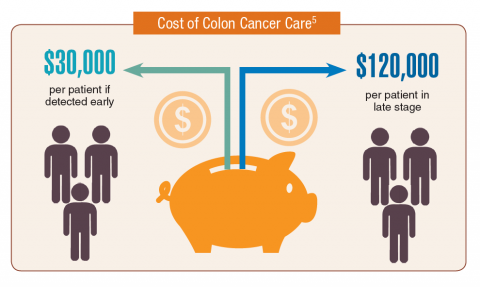

According to the latest VA budget, its researchers are conducting a broad array of research on cancers common in the veteran population, including prostate, lung, colorectal, bladder, kidney, pancreatic, skin, esophageal, and femalespecific cancers (such as breast and cervical cancer), as well as lymphomas and melanomas. For example, one study is focused on improving palliative care for patients with advanced cancer, and another will enroll 50,000 veterans to compare colorectal cancer screening strategies.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Cancer research is a high priority for the DoD and especially for the VA. Researchers in both agencies played an important role in the early stages of the Cancer Moonshot. As part of this initiative, the VA, DoD, and National Cancer Institute joined forces in the Applied Proteogenomics Organizational Learning and Outcomes (APOLLO) project to develop a system to quickly identify unique targets and pathways of cancer for better interventions.

The VA also will provide access to the Million Veteran Program database, and > 20 years of electronic health records data for analysis using the U.S. Department of Energy’s advanced computer systems. The enhanced computational infrastructure provided by the departments will facilitate new studies of cancer genomics. The research will begin with prostate cancer, and it is hoped that the project will help researchers distinguish between those prostate cancers that require aggressive management and the more benign cancers that are less likely to progress.

According to the latest VA budget, its researchers are conducting a broad array of research on cancers common in the veteran population, including prostate, lung, colorectal, bladder, kidney, pancreatic, skin, esophageal, and femalespecific cancers (such as breast and cervical cancer), as well as lymphomas and melanomas. For example, one study is focused on improving palliative care for patients with advanced cancer, and another will enroll 50,000 veterans to compare colorectal cancer screening strategies.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Cancer research is a high priority for the DoD and especially for the VA. Researchers in both agencies played an important role in the early stages of the Cancer Moonshot. As part of this initiative, the VA, DoD, and National Cancer Institute joined forces in the Applied Proteogenomics Organizational Learning and Outcomes (APOLLO) project to develop a system to quickly identify unique targets and pathways of cancer for better interventions.

The VA also will provide access to the Million Veteran Program database, and > 20 years of electronic health records data for analysis using the U.S. Department of Energy’s advanced computer systems. The enhanced computational infrastructure provided by the departments will facilitate new studies of cancer genomics. The research will begin with prostate cancer, and it is hoped that the project will help researchers distinguish between those prostate cancers that require aggressive management and the more benign cancers that are less likely to progress.

According to the latest VA budget, its researchers are conducting a broad array of research on cancers common in the veteran population, including prostate, lung, colorectal, bladder, kidney, pancreatic, skin, esophageal, and femalespecific cancers (such as breast and cervical cancer), as well as lymphomas and melanomas. For example, one study is focused on improving palliative care for patients with advanced cancer, and another will enroll 50,000 veterans to compare colorectal cancer screening strategies.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Lab results may help predict complications in ALL treatment

(ALL) who were treated with four-drug induction therapy.

Kasper Warrick, MD, and his colleagues at Indiana University in Indianapolis reported findings from a retrospective study of 73 ALL patients at their hospital. They performed chart reviews comparing a cohort of 42 patients who were discharged on day 4 of their induction treatment with 31 similar patients who had a longer hospital stay or admission to the intensive care unit. The report was published in Leukemia Research.

Univariate analysis found that patients with a longer length of stay were more likely to have a fever, pretransfusion hemoglobin of less than 8 g/dL, lower serum bicarbonate values, abnormal serum calcium, and abnormal serum phosphate. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression found that low serum bicarbonate and a lower platelet count on day 4 of admission was predictive of a prolonged hospital stay. About a third of patients from each group had an unplanned readmission within 30 days.

The researchers concluded that early discharge is safe in only a subgroup of high-risk ALL patients undergoing induction chemotherapy. “Treating physicians could opt for a discharge only after normalization of electrolyte abnormalities and renal functions, and when no transfusion support is needed (stable hematocrit and platelet count),” they wrote. Even in those cases, they recommended “aggressive and close outpatient follow” since patients are vulnerable to complications and readmissions.

SOURCE: Warrick K et al. Leuk Res. 2018 Jun 30:71:36-42.

(ALL) who were treated with four-drug induction therapy.

Kasper Warrick, MD, and his colleagues at Indiana University in Indianapolis reported findings from a retrospective study of 73 ALL patients at their hospital. They performed chart reviews comparing a cohort of 42 patients who were discharged on day 4 of their induction treatment with 31 similar patients who had a longer hospital stay or admission to the intensive care unit. The report was published in Leukemia Research.

Univariate analysis found that patients with a longer length of stay were more likely to have a fever, pretransfusion hemoglobin of less than 8 g/dL, lower serum bicarbonate values, abnormal serum calcium, and abnormal serum phosphate. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression found that low serum bicarbonate and a lower platelet count on day 4 of admission was predictive of a prolonged hospital stay. About a third of patients from each group had an unplanned readmission within 30 days.

The researchers concluded that early discharge is safe in only a subgroup of high-risk ALL patients undergoing induction chemotherapy. “Treating physicians could opt for a discharge only after normalization of electrolyte abnormalities and renal functions, and when no transfusion support is needed (stable hematocrit and platelet count),” they wrote. Even in those cases, they recommended “aggressive and close outpatient follow” since patients are vulnerable to complications and readmissions.

SOURCE: Warrick K et al. Leuk Res. 2018 Jun 30:71:36-42.

(ALL) who were treated with four-drug induction therapy.

Kasper Warrick, MD, and his colleagues at Indiana University in Indianapolis reported findings from a retrospective study of 73 ALL patients at their hospital. They performed chart reviews comparing a cohort of 42 patients who were discharged on day 4 of their induction treatment with 31 similar patients who had a longer hospital stay or admission to the intensive care unit. The report was published in Leukemia Research.

Univariate analysis found that patients with a longer length of stay were more likely to have a fever, pretransfusion hemoglobin of less than 8 g/dL, lower serum bicarbonate values, abnormal serum calcium, and abnormal serum phosphate. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression found that low serum bicarbonate and a lower platelet count on day 4 of admission was predictive of a prolonged hospital stay. About a third of patients from each group had an unplanned readmission within 30 days.

The researchers concluded that early discharge is safe in only a subgroup of high-risk ALL patients undergoing induction chemotherapy. “Treating physicians could opt for a discharge only after normalization of electrolyte abnormalities and renal functions, and when no transfusion support is needed (stable hematocrit and platelet count),” they wrote. Even in those cases, they recommended “aggressive and close outpatient follow” since patients are vulnerable to complications and readmissions.

SOURCE: Warrick K et al. Leuk Res. 2018 Jun 30:71:36-42.

FROM LEUKEMIA RESEARCH

Promising phase 3 results for ixazomib in multiple myeloma

who had responded to high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.

The drug’s sponsor, Takeda, announced that the oral proteasome inhibitor had met the primary endpoint – progression-free survival versus placebo – in the randomized, phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM3 study. They also reported that adverse events were consistent with previously reported results for single-agent use of ixazomib and that there were no new safety signals.

Full study results will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Company officials plan to submit the trial data to the Food and Drug Administration and regulatory agencies around the world to gain approval of ixazomib as a single-agent maintenance therapy, according to a Takeda announcement.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study is a double-blind study of 656 patients with multiple myeloma who have had complete response, very good partial response, or partial response to induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant. In addition to progression-free survival, the trial assessed overall survival.

who had responded to high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.

The drug’s sponsor, Takeda, announced that the oral proteasome inhibitor had met the primary endpoint – progression-free survival versus placebo – in the randomized, phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM3 study. They also reported that adverse events were consistent with previously reported results for single-agent use of ixazomib and that there were no new safety signals.

Full study results will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Company officials plan to submit the trial data to the Food and Drug Administration and regulatory agencies around the world to gain approval of ixazomib as a single-agent maintenance therapy, according to a Takeda announcement.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study is a double-blind study of 656 patients with multiple myeloma who have had complete response, very good partial response, or partial response to induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant. In addition to progression-free survival, the trial assessed overall survival.

who had responded to high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.

The drug’s sponsor, Takeda, announced that the oral proteasome inhibitor had met the primary endpoint – progression-free survival versus placebo – in the randomized, phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM3 study. They also reported that adverse events were consistent with previously reported results for single-agent use of ixazomib and that there were no new safety signals.

Full study results will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Company officials plan to submit the trial data to the Food and Drug Administration and regulatory agencies around the world to gain approval of ixazomib as a single-agent maintenance therapy, according to a Takeda announcement.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study is a double-blind study of 656 patients with multiple myeloma who have had complete response, very good partial response, or partial response to induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant. In addition to progression-free survival, the trial assessed overall survival.

Mutations may be detectable years before AML diagnosis

Individuals who develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may have somatic mutations detectable years before diagnosis, a newly published analysis shows.

Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, TP53, DNMT3A, TET2, and spliceosome genes at baseline assessment increased the odds of developing AML with a median follow-up of 9.6 years in the study, which was based on blood samples from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).

The findings suggest a “premalignant landscape of mutations” that may precede overt AML by many years, according to Pinkal Desai, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University and oncologist at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

“The ability to detect and identify high-risk mutations suggests that monitoring strategies for patients, as well as clinical trials of potentially preventative or disease-intercepting interventions should be considered,” wrote Dr. Desai and her colleagues. The report was published in Nature Medicine.

Their analysis comprised 212 women who participated in the WHI who were healthy at the baseline evaluation but went on to develop AML during follow-up. They performed deep sequencing on peripheral blood DNA for these cases and for 212 age-matched controls.

Women who developed AML were more likely than were controls to have mutations in baseline assessment (odds ratio, 4.86; 95% confidence interval, 3.07-7.77), and had demonstrated greater clonal complexity versus controls (comutations in 46.8% and 5.5%, respectively; odds ratio, 9.01; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), investigators found.

All 21 patients with TP53 mutations went on to develop AML, as did all 15 with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations and all 3 with RUNX1 mutations. Multivariate analysis showed that TP53, IDH1 and IDH2, TET2, DNMT3A and several spliceosome genes were associated with significantly increased odds of AML versus controls.

Based on these results, Dr. Desai and colleagues proposed that patients at increased AML risk should be followed in long-term monitoring studies that incorporate next-generation sequencing.

“Data from these studies will provide a robust rationale for clinical trials of preventative intervention strategies in populations at high risk of developing AML,” they wrote.

In clinical practice, monitoring individuals for AML-associated mutations will become more feasible as costs decrease and new therapies with favorable toxicity profiles are introduced, they added.

“Molecularly targeted therapy is already available for IDH2 mutations and is under development for mutations in other candidate genes found in this study including IDH1, TP53 and spliceosome genes,” they wrote.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The WHI program is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Desai P et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:1015-23.

Individuals who develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may have somatic mutations detectable years before diagnosis, a newly published analysis shows.

Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, TP53, DNMT3A, TET2, and spliceosome genes at baseline assessment increased the odds of developing AML with a median follow-up of 9.6 years in the study, which was based on blood samples from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).

The findings suggest a “premalignant landscape of mutations” that may precede overt AML by many years, according to Pinkal Desai, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University and oncologist at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

“The ability to detect and identify high-risk mutations suggests that monitoring strategies for patients, as well as clinical trials of potentially preventative or disease-intercepting interventions should be considered,” wrote Dr. Desai and her colleagues. The report was published in Nature Medicine.

Their analysis comprised 212 women who participated in the WHI who were healthy at the baseline evaluation but went on to develop AML during follow-up. They performed deep sequencing on peripheral blood DNA for these cases and for 212 age-matched controls.

Women who developed AML were more likely than were controls to have mutations in baseline assessment (odds ratio, 4.86; 95% confidence interval, 3.07-7.77), and had demonstrated greater clonal complexity versus controls (comutations in 46.8% and 5.5%, respectively; odds ratio, 9.01; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), investigators found.

All 21 patients with TP53 mutations went on to develop AML, as did all 15 with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations and all 3 with RUNX1 mutations. Multivariate analysis showed that TP53, IDH1 and IDH2, TET2, DNMT3A and several spliceosome genes were associated with significantly increased odds of AML versus controls.

Based on these results, Dr. Desai and colleagues proposed that patients at increased AML risk should be followed in long-term monitoring studies that incorporate next-generation sequencing.

“Data from these studies will provide a robust rationale for clinical trials of preventative intervention strategies in populations at high risk of developing AML,” they wrote.

In clinical practice, monitoring individuals for AML-associated mutations will become more feasible as costs decrease and new therapies with favorable toxicity profiles are introduced, they added.

“Molecularly targeted therapy is already available for IDH2 mutations and is under development for mutations in other candidate genes found in this study including IDH1, TP53 and spliceosome genes,” they wrote.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The WHI program is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Desai P et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:1015-23.

Individuals who develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may have somatic mutations detectable years before diagnosis, a newly published analysis shows.

Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, TP53, DNMT3A, TET2, and spliceosome genes at baseline assessment increased the odds of developing AML with a median follow-up of 9.6 years in the study, which was based on blood samples from participants in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).

The findings suggest a “premalignant landscape of mutations” that may precede overt AML by many years, according to Pinkal Desai, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University and oncologist at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, and her coauthors.

“The ability to detect and identify high-risk mutations suggests that monitoring strategies for patients, as well as clinical trials of potentially preventative or disease-intercepting interventions should be considered,” wrote Dr. Desai and her colleagues. The report was published in Nature Medicine.

Their analysis comprised 212 women who participated in the WHI who were healthy at the baseline evaluation but went on to develop AML during follow-up. They performed deep sequencing on peripheral blood DNA for these cases and for 212 age-matched controls.

Women who developed AML were more likely than were controls to have mutations in baseline assessment (odds ratio, 4.86; 95% confidence interval, 3.07-7.77), and had demonstrated greater clonal complexity versus controls (comutations in 46.8% and 5.5%, respectively; odds ratio, 9.01; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), investigators found.

All 21 patients with TP53 mutations went on to develop AML, as did all 15 with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations and all 3 with RUNX1 mutations. Multivariate analysis showed that TP53, IDH1 and IDH2, TET2, DNMT3A and several spliceosome genes were associated with significantly increased odds of AML versus controls.

Based on these results, Dr. Desai and colleagues proposed that patients at increased AML risk should be followed in long-term monitoring studies that incorporate next-generation sequencing.

“Data from these studies will provide a robust rationale for clinical trials of preventative intervention strategies in populations at high risk of developing AML,” they wrote.

In clinical practice, monitoring individuals for AML-associated mutations will become more feasible as costs decrease and new therapies with favorable toxicity profiles are introduced, they added.

“Molecularly targeted therapy is already available for IDH2 mutations and is under development for mutations in other candidate genes found in this study including IDH1, TP53 and spliceosome genes,” they wrote.

The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The WHI program is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Desai P et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:1015-23.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with controls, those who eventually developed AML were more likely to have mutations (odds ratio, 4.86; 95% CI, 3.07-7.77) in baseline assessment at a median of 9.6 years before diagnosis.

Study details: Analysis of blood samples from 212 women who developed AML and 212 age-matched controls in the Women’s Health Initiative.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures. The WHI program is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Desai P et al. Nat Med. 2018;24:1015-23.

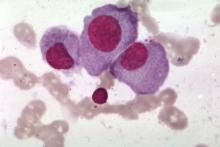

Rare Cancer Misdiagnosed As Orchitis

A 70-year-old man underwent salvage therapy for multiple myeloma (MM). While on maintenance immunotherapy he developed a sternal plasmacytoma. After the fifth cycle of treatment, he developed swelling, erythema, and pain in his right testis.

The main differential diagnoses for those symptoms are infections and tumors; infection is more common, so his clinicians at Indiana University School of Medicine presumed orchitis and started him on IV antibiotics. The pain resolved, but the swelling persisted after the antibiotic course. The clinicians turned to biochemical marker screening for germ cell tumors, but those were negative. Serial ultrasound imaging, which they had begun during his admission, remained unchanged.

Meanwhile, the patient’s chemotherapy was being held back, and he developed another sternal mass, prompting a fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT) scan to evaluate for relapse of myeloma. The scan revealed an enlarged, diffusely hypermetabolic right testicle. Believing the symptoms were related to the myeloma and not orchitis, the clinicians advised a radical orchiectomy.

A biopsy after the surgery showed tumor cells consistent with testicular plasmacytoma.

While rare, testicular plasmacytoma is commonly associated with MM, especially in the later stages, when cancer cells are more aggressive and not relying on bone marrow for survival, the clinicians say. Unlike myeloma, which typically spreads via blood to bone sites, testicular plasmacytoma may spread via lymphatic channels to the regional lymph nodes and subsequently to distant sites, the clinicians add, similarly to lymphoma or germ cell tumor.

It is hard to diagnose, though. The clinicians say the patient’s case illustrates the challenges. Imaging studies such as ultrasound and CT scans are not specific. And although FDG-PET/CT imaging is a standard staging tool for myeloma and helpful in identifying plasmacytoma when evidenced as intramedullary or extramedullary hypermetabolic lesions, hypermetabolic lesions are not always malignant, they note. FDG-PET/CT can’t differentiate between orchitis and testicular plasmacytoma. Biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard.

Source:

Schiavo C, Mann SA, Mer J, Suvannasankha A. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;pii:bcr-2017-222046.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222046.

A 70-year-old man underwent salvage therapy for multiple myeloma (MM). While on maintenance immunotherapy he developed a sternal plasmacytoma. After the fifth cycle of treatment, he developed swelling, erythema, and pain in his right testis.

The main differential diagnoses for those symptoms are infections and tumors; infection is more common, so his clinicians at Indiana University School of Medicine presumed orchitis and started him on IV antibiotics. The pain resolved, but the swelling persisted after the antibiotic course. The clinicians turned to biochemical marker screening for germ cell tumors, but those were negative. Serial ultrasound imaging, which they had begun during his admission, remained unchanged.

Meanwhile, the patient’s chemotherapy was being held back, and he developed another sternal mass, prompting a fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT) scan to evaluate for relapse of myeloma. The scan revealed an enlarged, diffusely hypermetabolic right testicle. Believing the symptoms were related to the myeloma and not orchitis, the clinicians advised a radical orchiectomy.

A biopsy after the surgery showed tumor cells consistent with testicular plasmacytoma.

While rare, testicular plasmacytoma is commonly associated with MM, especially in the later stages, when cancer cells are more aggressive and not relying on bone marrow for survival, the clinicians say. Unlike myeloma, which typically spreads via blood to bone sites, testicular plasmacytoma may spread via lymphatic channels to the regional lymph nodes and subsequently to distant sites, the clinicians add, similarly to lymphoma or germ cell tumor.

It is hard to diagnose, though. The clinicians say the patient’s case illustrates the challenges. Imaging studies such as ultrasound and CT scans are not specific. And although FDG-PET/CT imaging is a standard staging tool for myeloma and helpful in identifying plasmacytoma when evidenced as intramedullary or extramedullary hypermetabolic lesions, hypermetabolic lesions are not always malignant, they note. FDG-PET/CT can’t differentiate between orchitis and testicular plasmacytoma. Biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard.

Source:

Schiavo C, Mann SA, Mer J, Suvannasankha A. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;pii:bcr-2017-222046.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222046.

A 70-year-old man underwent salvage therapy for multiple myeloma (MM). While on maintenance immunotherapy he developed a sternal plasmacytoma. After the fifth cycle of treatment, he developed swelling, erythema, and pain in his right testis.

The main differential diagnoses for those symptoms are infections and tumors; infection is more common, so his clinicians at Indiana University School of Medicine presumed orchitis and started him on IV antibiotics. The pain resolved, but the swelling persisted after the antibiotic course. The clinicians turned to biochemical marker screening for germ cell tumors, but those were negative. Serial ultrasound imaging, which they had begun during his admission, remained unchanged.

Meanwhile, the patient’s chemotherapy was being held back, and he developed another sternal mass, prompting a fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT) scan to evaluate for relapse of myeloma. The scan revealed an enlarged, diffusely hypermetabolic right testicle. Believing the symptoms were related to the myeloma and not orchitis, the clinicians advised a radical orchiectomy.

A biopsy after the surgery showed tumor cells consistent with testicular plasmacytoma.

While rare, testicular plasmacytoma is commonly associated with MM, especially in the later stages, when cancer cells are more aggressive and not relying on bone marrow for survival, the clinicians say. Unlike myeloma, which typically spreads via blood to bone sites, testicular plasmacytoma may spread via lymphatic channels to the regional lymph nodes and subsequently to distant sites, the clinicians add, similarly to lymphoma or germ cell tumor.

It is hard to diagnose, though. The clinicians say the patient’s case illustrates the challenges. Imaging studies such as ultrasound and CT scans are not specific. And although FDG-PET/CT imaging is a standard staging tool for myeloma and helpful in identifying plasmacytoma when evidenced as intramedullary or extramedullary hypermetabolic lesions, hypermetabolic lesions are not always malignant, they note. FDG-PET/CT can’t differentiate between orchitis and testicular plasmacytoma. Biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard.

Source:

Schiavo C, Mann SA, Mer J, Suvannasankha A. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;pii:bcr-2017-222046.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222046.

Is CLL chemoimmunotherapy dead? Not yet

CHICAGO – Chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia is on the way out, but there’s one scenario where it still plays a key role, according to one leukemia expert.

That scenario is not in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), where the use of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) may be hard to justify today. Data supporting use of FCR in relapsed CLL show a median progression-free survival (PFS) of about 21 months, Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. There is also data for bendamustine-rituximab retreatment showing a median event-free survival of about 15 months, she added.

By contrast, the 5-year follow-up data for the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib in the relapsed/refractory setting shows a median PFS of 52 months, which is “extraordinary,” given that the patients had a median of four prior regimens, Dr. O’Brien said.

Similarly, recently published results from the randomized, phase 3 MURANO study of venetoclax plus rituximab in relapsed/refractory CLL showed that median PFS was not reached at a median follow-up of 23.8 months, versus a median of 17 months for the bendamustine-rituximab comparison arm (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[12]:1107-20).

“Thanks to the MURANO study, we likely will have an expanded label for venetoclax that includes the combination of venetoclax and rituximab,” Dr. O’Brien said. “I think it’s quite clear that either of these is dramatically better than what you get with retreatment with chemotherapy, so I personally don’t think there is a role for chemoimmunotherapy in the relapsed patient.”

On June 8, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration granted regular approval for venetoclax for patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma, with or without 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy. The FDA also approved its use in combination with rituximab.*

But frontline CLL treatment is currently a little bit more complicated, Dr. O’Brien said.

Recent studies show favorable long-term outcomes with FCR frontline therapy in the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene (IgHV) –mutated subgroup of patients, she noted.

The longest follow-up comes from a study from investigators at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, published in 2016. In that study, the 12.8-year PFS was 53.9% for IgHV-mutated patients, versus just 8.7% for patients with unmutated IgHV. Of the IgHV-mutated group, more than half achieved minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity after treatment (Blood. 2016 Jan 21; 127[3]: 303-9).

“I’m going to go out on a limb and I’m going to suggest that I think there is a cure fraction here,” Dr. O’Brien said. “On the other hand, if there’s not a cure fraction and they’re going to relapse after 17 years, that’s a pretty attractive endpoint, even if it’s not a cure fraction.”

Clinical practice guidelines now recognize IgHV mutation status as an important marker that should be obtained when deciding on treatment, Dr. O’Brien noted.

For unmutated patients, the RESONATE-2 trial showed that ibrutinib was superior to chlorambucil in older patients, many of whom had comorbid conditions. In the 3-year update, median PFS was approximately 15 months for chlorambucil, while for ibrutinib the median PFS was “nowhere near” being reached, Dr. O’Brien said.

Those data may not be so relevant for fit, unmutated patients, and two randomized trials comparing FCR with bendamustine and rituximab have yet to report data. However, one recent cross-trial comparison found fairly overlapping survival curves for the two chemoimmunotherapy approaches.

Dr. O’Brien said she would put older patients with comorbidities on ibrutinib if a clinical trial was not available, and for fit, unmutated patients, while more data are needed, she would also use ibrutinib. However, patient preference sometimes tips the scale in favor of FCR.

“The discussions sometimes are quite long about whether the patient should opt to take ibrutinib or FCR,” Dr. O’Brien said. “The last patient I had that discussion with elected to take FCR. When I asked him why, he said because he liked the idea of being finished in six cycles, off all therapy, and hopefully in remission.”

While Dr. O’Brien said she views chemoimmunotherapy as still relevant in IgHV-mutated patients, eventually it will go away, she concluded. Toward that end, there is considerable interest in venetoclax plus ibrutinib, a combination that, in early reports, has yielded very encouraging MRD results in first-line CLL.

“We have no long-term data, but very, very exciting MRD negativity data,” Dr. O’Brien said.

Dr. O’Brien reported relationships with Abbvie, Amgen, Celgene, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, and others.

*This story was updated 6/25/2018.

CHICAGO – Chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia is on the way out, but there’s one scenario where it still plays a key role, according to one leukemia expert.

That scenario is not in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), where the use of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) may be hard to justify today. Data supporting use of FCR in relapsed CLL show a median progression-free survival (PFS) of about 21 months, Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. There is also data for bendamustine-rituximab retreatment showing a median event-free survival of about 15 months, she added.

By contrast, the 5-year follow-up data for the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib in the relapsed/refractory setting shows a median PFS of 52 months, which is “extraordinary,” given that the patients had a median of four prior regimens, Dr. O’Brien said.

Similarly, recently published results from the randomized, phase 3 MURANO study of venetoclax plus rituximab in relapsed/refractory CLL showed that median PFS was not reached at a median follow-up of 23.8 months, versus a median of 17 months for the bendamustine-rituximab comparison arm (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[12]:1107-20).

“Thanks to the MURANO study, we likely will have an expanded label for venetoclax that includes the combination of venetoclax and rituximab,” Dr. O’Brien said. “I think it’s quite clear that either of these is dramatically better than what you get with retreatment with chemotherapy, so I personally don’t think there is a role for chemoimmunotherapy in the relapsed patient.”

On June 8, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration granted regular approval for venetoclax for patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma, with or without 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy. The FDA also approved its use in combination with rituximab.*

But frontline CLL treatment is currently a little bit more complicated, Dr. O’Brien said.

Recent studies show favorable long-term outcomes with FCR frontline therapy in the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene (IgHV) –mutated subgroup of patients, she noted.

The longest follow-up comes from a study from investigators at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, published in 2016. In that study, the 12.8-year PFS was 53.9% for IgHV-mutated patients, versus just 8.7% for patients with unmutated IgHV. Of the IgHV-mutated group, more than half achieved minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity after treatment (Blood. 2016 Jan 21; 127[3]: 303-9).

“I’m going to go out on a limb and I’m going to suggest that I think there is a cure fraction here,” Dr. O’Brien said. “On the other hand, if there’s not a cure fraction and they’re going to relapse after 17 years, that’s a pretty attractive endpoint, even if it’s not a cure fraction.”

Clinical practice guidelines now recognize IgHV mutation status as an important marker that should be obtained when deciding on treatment, Dr. O’Brien noted.

For unmutated patients, the RESONATE-2 trial showed that ibrutinib was superior to chlorambucil in older patients, many of whom had comorbid conditions. In the 3-year update, median PFS was approximately 15 months for chlorambucil, while for ibrutinib the median PFS was “nowhere near” being reached, Dr. O’Brien said.

Those data may not be so relevant for fit, unmutated patients, and two randomized trials comparing FCR with bendamustine and rituximab have yet to report data. However, one recent cross-trial comparison found fairly overlapping survival curves for the two chemoimmunotherapy approaches.

Dr. O’Brien said she would put older patients with comorbidities on ibrutinib if a clinical trial was not available, and for fit, unmutated patients, while more data are needed, she would also use ibrutinib. However, patient preference sometimes tips the scale in favor of FCR.

“The discussions sometimes are quite long about whether the patient should opt to take ibrutinib or FCR,” Dr. O’Brien said. “The last patient I had that discussion with elected to take FCR. When I asked him why, he said because he liked the idea of being finished in six cycles, off all therapy, and hopefully in remission.”

While Dr. O’Brien said she views chemoimmunotherapy as still relevant in IgHV-mutated patients, eventually it will go away, she concluded. Toward that end, there is considerable interest in venetoclax plus ibrutinib, a combination that, in early reports, has yielded very encouraging MRD results in first-line CLL.

“We have no long-term data, but very, very exciting MRD negativity data,” Dr. O’Brien said.

Dr. O’Brien reported relationships with Abbvie, Amgen, Celgene, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, and others.

*This story was updated 6/25/2018.

CHICAGO – Chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia is on the way out, but there’s one scenario where it still plays a key role, according to one leukemia expert.

That scenario is not in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), where the use of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) may be hard to justify today. Data supporting use of FCR in relapsed CLL show a median progression-free survival (PFS) of about 21 months, Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. There is also data for bendamustine-rituximab retreatment showing a median event-free survival of about 15 months, she added.

By contrast, the 5-year follow-up data for the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib in the relapsed/refractory setting shows a median PFS of 52 months, which is “extraordinary,” given that the patients had a median of four prior regimens, Dr. O’Brien said.

Similarly, recently published results from the randomized, phase 3 MURANO study of venetoclax plus rituximab in relapsed/refractory CLL showed that median PFS was not reached at a median follow-up of 23.8 months, versus a median of 17 months for the bendamustine-rituximab comparison arm (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[12]:1107-20).

“Thanks to the MURANO study, we likely will have an expanded label for venetoclax that includes the combination of venetoclax and rituximab,” Dr. O’Brien said. “I think it’s quite clear that either of these is dramatically better than what you get with retreatment with chemotherapy, so I personally don’t think there is a role for chemoimmunotherapy in the relapsed patient.”

On June 8, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration granted regular approval for venetoclax for patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma, with or without 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy. The FDA also approved its use in combination with rituximab.*

But frontline CLL treatment is currently a little bit more complicated, Dr. O’Brien said.

Recent studies show favorable long-term outcomes with FCR frontline therapy in the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene (IgHV) –mutated subgroup of patients, she noted.

The longest follow-up comes from a study from investigators at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, published in 2016. In that study, the 12.8-year PFS was 53.9% for IgHV-mutated patients, versus just 8.7% for patients with unmutated IgHV. Of the IgHV-mutated group, more than half achieved minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity after treatment (Blood. 2016 Jan 21; 127[3]: 303-9).

“I’m going to go out on a limb and I’m going to suggest that I think there is a cure fraction here,” Dr. O’Brien said. “On the other hand, if there’s not a cure fraction and they’re going to relapse after 17 years, that’s a pretty attractive endpoint, even if it’s not a cure fraction.”

Clinical practice guidelines now recognize IgHV mutation status as an important marker that should be obtained when deciding on treatment, Dr. O’Brien noted.

For unmutated patients, the RESONATE-2 trial showed that ibrutinib was superior to chlorambucil in older patients, many of whom had comorbid conditions. In the 3-year update, median PFS was approximately 15 months for chlorambucil, while for ibrutinib the median PFS was “nowhere near” being reached, Dr. O’Brien said.

Those data may not be so relevant for fit, unmutated patients, and two randomized trials comparing FCR with bendamustine and rituximab have yet to report data. However, one recent cross-trial comparison found fairly overlapping survival curves for the two chemoimmunotherapy approaches.

Dr. O’Brien said she would put older patients with comorbidities on ibrutinib if a clinical trial was not available, and for fit, unmutated patients, while more data are needed, she would also use ibrutinib. However, patient preference sometimes tips the scale in favor of FCR.

“The discussions sometimes are quite long about whether the patient should opt to take ibrutinib or FCR,” Dr. O’Brien said. “The last patient I had that discussion with elected to take FCR. When I asked him why, he said because he liked the idea of being finished in six cycles, off all therapy, and hopefully in remission.”

While Dr. O’Brien said she views chemoimmunotherapy as still relevant in IgHV-mutated patients, eventually it will go away, she concluded. Toward that end, there is considerable interest in venetoclax plus ibrutinib, a combination that, in early reports, has yielded very encouraging MRD results in first-line CLL.

“We have no long-term data, but very, very exciting MRD negativity data,” Dr. O’Brien said.

Dr. O’Brien reported relationships with Abbvie, Amgen, Celgene, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, and others.

*This story was updated 6/25/2018.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASCO 2018

Study pinpoints skin cancer risk factors after hematopoietic cell transplant

CHICAGO – The 10-year incidence rates for both squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising after hematopoietic cell transplantation are impressively high at 17%-plus for each, but the malignancies occur on two very different timelines, according to Jeffrey F. Scott, MD, a fellow in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

Most of the squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in a large multicenter retrospective study developed within the first 5 years following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), while the majority of the basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) occurred after that point, Dr. Scott reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

He presented the results of the study, which included 876 HCT recipients followed for a mean of 6.1 years. The study objective was to pin down the risk factors for skin cancer after HCT, especially the patient-specific ones. This has become a pressing issue because the use of HCT is steadily growing, and the 5-year survival rate now exceeds 50%.

The transplant-specific risk factors have previously been fairly well described by others. They include the donor source, type of disease, the conditioning regimen, whether whole body irradiation was used, immunosuppression, graft versus host disease (GVHD), and others.

The patient-centric risk factors, in contrast, have not been well characterized. And it’s critical to thoroughly understand these risk factors in order to develop targeted prevention and surveillance strategies, Dr. Scott said.

“There remains a significant knowledge gap within our field. I would venture that the majority of this audience has treated a patient with skin cancer who has had a transplant,” he said. “Yet when a patient asks us, ‘Doc, what is my risk for skin cancer after my HCT?’ we’re really unable to give them an accurate and complete assessment of that risk. That’s because we’re missing the second major category of risk factors: the patient-specific risk factors.”

The reason for that, he added, is that the major population-based studies and national HCT registries are run by hematologists and oncologists, and they haven’t adequately captured the patient-specific skin cancer risk factors. But these are variables very familiar to dermatologists. They include skin phenotype, history of UV radiation exposure, and history of pre-HCT skin cancer.

Dr. Scott said the multicenter study he presented has two major advantages over prior studies: its large size and thorough followup. Nearly all 876 patients were followed by both an oncologist and a dermatologist at the same institution.

During followup, the HCT recipients collectively developed 63 SCCs, 55 BCCs, and 16 malignant melanomas. The 5- and 10-year incidence rates for SCC were 10.6% and 17.2%. For BCC, the 5- and 10-year rates were 5.7% and 17.6%. All 16 cases of melanoma occurred within 5 years after HCT.

In multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses, photodamage documented on examination was independently associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk of post-HCT SCC and a 3.5-fold increased risk of BCC.

A pre-transplant history of BCC was associated with a 3.9-fold increased likelihood of developing a BCC afterwards. Similarly, a pre-HCT history of SCC conferred a 4.2-fold increased risk of post-transplant SCC and was also independently associated with a 6.6-fold increased risk of developing melanoma post-HCT.

Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were respectively associated with 9.3- and 7.2-fold increased risks of post-HCT nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with skin types III-VI.

Acute GVHD wasn’t associated with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer after HCT. However, in an observation that hasn’t previously been reported by others, chronic GVHD with skin involvement was associated with a 2.7-fold increased likelihood of SCC post-HCT, Dr. Scott noted.

What’s next for Dr. Scott and his coinvestigators? “Our ultimate goal with this project is to develop an interactive risk assessment tool like the National Cancer Institute’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool that can be online and used by patients and providers to estimate their individualized risk of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma after HCT,” he said.

Dr. Scott reported having no financial conflicts related to the study.

CHICAGO – The 10-year incidence rates for both squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising after hematopoietic cell transplantation are impressively high at 17%-plus for each, but the malignancies occur on two very different timelines, according to Jeffrey F. Scott, MD, a fellow in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

Most of the squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in a large multicenter retrospective study developed within the first 5 years following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), while the majority of the basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) occurred after that point, Dr. Scott reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

He presented the results of the study, which included 876 HCT recipients followed for a mean of 6.1 years. The study objective was to pin down the risk factors for skin cancer after HCT, especially the patient-specific ones. This has become a pressing issue because the use of HCT is steadily growing, and the 5-year survival rate now exceeds 50%.

The transplant-specific risk factors have previously been fairly well described by others. They include the donor source, type of disease, the conditioning regimen, whether whole body irradiation was used, immunosuppression, graft versus host disease (GVHD), and others.

The patient-centric risk factors, in contrast, have not been well characterized. And it’s critical to thoroughly understand these risk factors in order to develop targeted prevention and surveillance strategies, Dr. Scott said.

“There remains a significant knowledge gap within our field. I would venture that the majority of this audience has treated a patient with skin cancer who has had a transplant,” he said. “Yet when a patient asks us, ‘Doc, what is my risk for skin cancer after my HCT?’ we’re really unable to give them an accurate and complete assessment of that risk. That’s because we’re missing the second major category of risk factors: the patient-specific risk factors.”

The reason for that, he added, is that the major population-based studies and national HCT registries are run by hematologists and oncologists, and they haven’t adequately captured the patient-specific skin cancer risk factors. But these are variables very familiar to dermatologists. They include skin phenotype, history of UV radiation exposure, and history of pre-HCT skin cancer.

Dr. Scott said the multicenter study he presented has two major advantages over prior studies: its large size and thorough followup. Nearly all 876 patients were followed by both an oncologist and a dermatologist at the same institution.

During followup, the HCT recipients collectively developed 63 SCCs, 55 BCCs, and 16 malignant melanomas. The 5- and 10-year incidence rates for SCC were 10.6% and 17.2%. For BCC, the 5- and 10-year rates were 5.7% and 17.6%. All 16 cases of melanoma occurred within 5 years after HCT.

In multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses, photodamage documented on examination was independently associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk of post-HCT SCC and a 3.5-fold increased risk of BCC.

A pre-transplant history of BCC was associated with a 3.9-fold increased likelihood of developing a BCC afterwards. Similarly, a pre-HCT history of SCC conferred a 4.2-fold increased risk of post-transplant SCC and was also independently associated with a 6.6-fold increased risk of developing melanoma post-HCT.

Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were respectively associated with 9.3- and 7.2-fold increased risks of post-HCT nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with skin types III-VI.

Acute GVHD wasn’t associated with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer after HCT. However, in an observation that hasn’t previously been reported by others, chronic GVHD with skin involvement was associated with a 2.7-fold increased likelihood of SCC post-HCT, Dr. Scott noted.

What’s next for Dr. Scott and his coinvestigators? “Our ultimate goal with this project is to develop an interactive risk assessment tool like the National Cancer Institute’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool that can be online and used by patients and providers to estimate their individualized risk of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma after HCT,” he said.

Dr. Scott reported having no financial conflicts related to the study.

CHICAGO – The 10-year incidence rates for both squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising after hematopoietic cell transplantation are impressively high at 17%-plus for each, but the malignancies occur on two very different timelines, according to Jeffrey F. Scott, MD, a fellow in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

Most of the squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in a large multicenter retrospective study developed within the first 5 years following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), while the majority of the basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) occurred after that point, Dr. Scott reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

He presented the results of the study, which included 876 HCT recipients followed for a mean of 6.1 years. The study objective was to pin down the risk factors for skin cancer after HCT, especially the patient-specific ones. This has become a pressing issue because the use of HCT is steadily growing, and the 5-year survival rate now exceeds 50%.

The transplant-specific risk factors have previously been fairly well described by others. They include the donor source, type of disease, the conditioning regimen, whether whole body irradiation was used, immunosuppression, graft versus host disease (GVHD), and others.

The patient-centric risk factors, in contrast, have not been well characterized. And it’s critical to thoroughly understand these risk factors in order to develop targeted prevention and surveillance strategies, Dr. Scott said.

“There remains a significant knowledge gap within our field. I would venture that the majority of this audience has treated a patient with skin cancer who has had a transplant,” he said. “Yet when a patient asks us, ‘Doc, what is my risk for skin cancer after my HCT?’ we’re really unable to give them an accurate and complete assessment of that risk. That’s because we’re missing the second major category of risk factors: the patient-specific risk factors.”

The reason for that, he added, is that the major population-based studies and national HCT registries are run by hematologists and oncologists, and they haven’t adequately captured the patient-specific skin cancer risk factors. But these are variables very familiar to dermatologists. They include skin phenotype, history of UV radiation exposure, and history of pre-HCT skin cancer.

Dr. Scott said the multicenter study he presented has two major advantages over prior studies: its large size and thorough followup. Nearly all 876 patients were followed by both an oncologist and a dermatologist at the same institution.

During followup, the HCT recipients collectively developed 63 SCCs, 55 BCCs, and 16 malignant melanomas. The 5- and 10-year incidence rates for SCC were 10.6% and 17.2%. For BCC, the 5- and 10-year rates were 5.7% and 17.6%. All 16 cases of melanoma occurred within 5 years after HCT.

In multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses, photodamage documented on examination was independently associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk of post-HCT SCC and a 3.5-fold increased risk of BCC.

A pre-transplant history of BCC was associated with a 3.9-fold increased likelihood of developing a BCC afterwards. Similarly, a pre-HCT history of SCC conferred a 4.2-fold increased risk of post-transplant SCC and was also independently associated with a 6.6-fold increased risk of developing melanoma post-HCT.

Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were respectively associated with 9.3- and 7.2-fold increased risks of post-HCT nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with skin types III-VI.

Acute GVHD wasn’t associated with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer after HCT. However, in an observation that hasn’t previously been reported by others, chronic GVHD with skin involvement was associated with a 2.7-fold increased likelihood of SCC post-HCT, Dr. Scott noted.

What’s next for Dr. Scott and his coinvestigators? “Our ultimate goal with this project is to develop an interactive risk assessment tool like the National Cancer Institute’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool that can be online and used by patients and providers to estimate their individualized risk of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma after HCT,” he said.

Dr. Scott reported having no financial conflicts related to the study.

REPORTING FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Photodamage documented on examination more than triples the risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer after hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Study details: A multicenter retrospective study of 876 hematopoietic cell recipients followed for a mean of 6.1 years.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts related to the study, which was conducted without commercial support.

Ruxolitinib overcame lenalidomide resistance in myeloma

based on phase I trial results presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The clinical trial is the first to demonstrate the activity of a JAK inhibitor in the treatment of myeloma patients, according to investigator James R. Berenson, MD, medical and scientific director for the Institute for Myeloma & Bone Cancer Research (IMBCR), West Hollywood, Calif.

“These promising results have led to the expansion of the current clinical trial and provide the basis for exploration of this and other JAK inhibitor-containing combinations for treating patients with myeloma and other malignant diseases,” he added.

The dose-escalation study enrolled 28 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who had previous treatment with lenalidomide/steroids and a proteasome inhibitor. Subjects received ruxolitinib twice daily continuously, lenalidomide daily on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle, and methylprednisolone orally every other day. A traditional 3+3 dose escalation design was used to enroll subjects in four cohorts. In DL0, patients received ruxolitinib 5 mg, lenalidomide 5 mg, and methylprednisolone 40 mg. In DL+1 and +2, both doses of lenalidomide and methylprednisolone remained unchanged, and ruxolitinib was escalated to 10 and 15 mg, respectively. In DL+3, lenalidomide was escalated to 10 mg with methylprednisolone unchanged and ruxolitinib at 15 mg. A total of 19 patients were treated at the highest dose level, which was ruxolitinib 15 mg twice daily on days 1-28, lenalidomide 10 mg daily on days 1-21, and methylprednisolone 40 mg every other day.

The overall response rate was 39% (10 of 26 evaluable patients), Dr. Berenson reported. The clinical benefit rate was 50% (13 of 26 patients), with a median duration of response of 5.6 months in that group.

There were no dose-limiting toxicities. Grade 3 toxicities reported included thrombocytopenia in 11% (3 patients, gastrointestinal bleeding in 11% (3 patients), and anemia in 7% (2 patients).

These results are encouraging, though challenges remain, said Craig Hofmeister, MD, MPH, of Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University, Atlanta.

“Clearly in these patients who are 100% lenalidomide refractory, the overall response rate of anything greater than or close to 20, 30, 40% is very appealing,” Dr. Hofmeister said in an ASCO presentation discussing the results of this trial.

The usual rationale for JAK inhibition is targeting of the bone microenvironment, but the microenvironment is a formidable opponent, Dr. Hofmeister said in his presentation.

“That’s an uphill battle,” he said. “There is an upcoming carfilzomib and ruxolitinib trial in multiple myeloma moving forward, and I’d be excited to see” the results.

The study (NCT03110822) was sponsored by Oncotherapeutics in collaboration with Incyte, the maker of ruxolitinib (Jakafi). Dr. Berenson, the presenting author, had disclosures related to Incyte, as well as Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, and OncoTracker.

SOURCE: Berenson JR, et al. J Clin Oncol 36, 2018 (suppl; abstr 8005).

based on phase I trial results presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The clinical trial is the first to demonstrate the activity of a JAK inhibitor in the treatment of myeloma patients, according to investigator James R. Berenson, MD, medical and scientific director for the Institute for Myeloma & Bone Cancer Research (IMBCR), West Hollywood, Calif.

“These promising results have led to the expansion of the current clinical trial and provide the basis for exploration of this and other JAK inhibitor-containing combinations for treating patients with myeloma and other malignant diseases,” he added.

The dose-escalation study enrolled 28 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who had previous treatment with lenalidomide/steroids and a proteasome inhibitor. Subjects received ruxolitinib twice daily continuously, lenalidomide daily on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle, and methylprednisolone orally every other day. A traditional 3+3 dose escalation design was used to enroll subjects in four cohorts. In DL0, patients received ruxolitinib 5 mg, lenalidomide 5 mg, and methylprednisolone 40 mg. In DL+1 and +2, both doses of lenalidomide and methylprednisolone remained unchanged, and ruxolitinib was escalated to 10 and 15 mg, respectively. In DL+3, lenalidomide was escalated to 10 mg with methylprednisolone unchanged and ruxolitinib at 15 mg. A total of 19 patients were treated at the highest dose level, which was ruxolitinib 15 mg twice daily on days 1-28, lenalidomide 10 mg daily on days 1-21, and methylprednisolone 40 mg every other day.

The overall response rate was 39% (10 of 26 evaluable patients), Dr. Berenson reported. The clinical benefit rate was 50% (13 of 26 patients), with a median duration of response of 5.6 months in that group.

There were no dose-limiting toxicities. Grade 3 toxicities reported included thrombocytopenia in 11% (3 patients, gastrointestinal bleeding in 11% (3 patients), and anemia in 7% (2 patients).

These results are encouraging, though challenges remain, said Craig Hofmeister, MD, MPH, of Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University, Atlanta.

“Clearly in these patients who are 100% lenalidomide refractory, the overall response rate of anything greater than or close to 20, 30, 40% is very appealing,” Dr. Hofmeister said in an ASCO presentation discussing the results of this trial.

The usual rationale for JAK inhibition is targeting of the bone microenvironment, but the microenvironment is a formidable opponent, Dr. Hofmeister said in his presentation.

“That’s an uphill battle,” he said. “There is an upcoming carfilzomib and ruxolitinib trial in multiple myeloma moving forward, and I’d be excited to see” the results.

The study (NCT03110822) was sponsored by Oncotherapeutics in collaboration with Incyte, the maker of ruxolitinib (Jakafi). Dr. Berenson, the presenting author, had disclosures related to Incyte, as well as Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, and OncoTracker.

SOURCE: Berenson JR, et al. J Clin Oncol 36, 2018 (suppl; abstr 8005).

based on phase I trial results presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The clinical trial is the first to demonstrate the activity of a JAK inhibitor in the treatment of myeloma patients, according to investigator James R. Berenson, MD, medical and scientific director for the Institute for Myeloma & Bone Cancer Research (IMBCR), West Hollywood, Calif.

“These promising results have led to the expansion of the current clinical trial and provide the basis for exploration of this and other JAK inhibitor-containing combinations for treating patients with myeloma and other malignant diseases,” he added.

The dose-escalation study enrolled 28 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who had previous treatment with lenalidomide/steroids and a proteasome inhibitor. Subjects received ruxolitinib twice daily continuously, lenalidomide daily on days 1-21 of a 28-day cycle, and methylprednisolone orally every other day. A traditional 3+3 dose escalation design was used to enroll subjects in four cohorts. In DL0, patients received ruxolitinib 5 mg, lenalidomide 5 mg, and methylprednisolone 40 mg. In DL+1 and +2, both doses of lenalidomide and methylprednisolone remained unchanged, and ruxolitinib was escalated to 10 and 15 mg, respectively. In DL+3, lenalidomide was escalated to 10 mg with methylprednisolone unchanged and ruxolitinib at 15 mg. A total of 19 patients were treated at the highest dose level, which was ruxolitinib 15 mg twice daily on days 1-28, lenalidomide 10 mg daily on days 1-21, and methylprednisolone 40 mg every other day.

The overall response rate was 39% (10 of 26 evaluable patients), Dr. Berenson reported. The clinical benefit rate was 50% (13 of 26 patients), with a median duration of response of 5.6 months in that group.

There were no dose-limiting toxicities. Grade 3 toxicities reported included thrombocytopenia in 11% (3 patients, gastrointestinal bleeding in 11% (3 patients), and anemia in 7% (2 patients).

These results are encouraging, though challenges remain, said Craig Hofmeister, MD, MPH, of Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University, Atlanta.

“Clearly in these patients who are 100% lenalidomide refractory, the overall response rate of anything greater than or close to 20, 30, 40% is very appealing,” Dr. Hofmeister said in an ASCO presentation discussing the results of this trial.

The usual rationale for JAK inhibition is targeting of the bone microenvironment, but the microenvironment is a formidable opponent, Dr. Hofmeister said in his presentation.

“That’s an uphill battle,” he said. “There is an upcoming carfilzomib and ruxolitinib trial in multiple myeloma moving forward, and I’d be excited to see” the results.

The study (NCT03110822) was sponsored by Oncotherapeutics in collaboration with Incyte, the maker of ruxolitinib (Jakafi). Dr. Berenson, the presenting author, had disclosures related to Incyte, as well as Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, and OncoTracker.

SOURCE: Berenson JR, et al. J Clin Oncol 36, 2018 (suppl; abstr 8005).

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2018

Key clinical point: The JAK 1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, in combination with lenalidomide and methylprednisolone, overcame resistance to lenalidomide in about half of heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma in a phase I trial.

Major finding: The overall response rate was 39%, and the clinical benefit rate was 50% (13 of 26 patients).

Study details: A phase 1 study including 28 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who had previous treatment with lenalidomide/steroids and a proteasome inhibitor.

Disclosures: Dr. Berenson, the presenting author, had disclosures related to Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Incyte, Janssen, Takeda, and OncoTracker.

Source: Berenson JR, et al. J Clin Oncol 36, 2018 (suppl; abstr 8005).

CAR T therapy to enter early testing in multiple myeloma

Janssen Biotech is launching a phase 1b/2 trial of an .

The trial, which was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration to begin in the second half of 2018, will evaluate the safety and efficacy of LCAR-B38M (JNJ-68284528). The CAR T therapy targets B-cell Maturation Antigen and expresses a CAR protein that is identical to a product that was developed by Legend Biotech and evaluated in a first-in-human clinical study in China.

The drug is being developed as part of a collaboration between Legend Biotech and Janssen Biotech.

Janssen Biotech is launching a phase 1b/2 trial of an .

The trial, which was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration to begin in the second half of 2018, will evaluate the safety and efficacy of LCAR-B38M (JNJ-68284528). The CAR T therapy targets B-cell Maturation Antigen and expresses a CAR protein that is identical to a product that was developed by Legend Biotech and evaluated in a first-in-human clinical study in China.

The drug is being developed as part of a collaboration between Legend Biotech and Janssen Biotech.

Janssen Biotech is launching a phase 1b/2 trial of an .

The trial, which was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration to begin in the second half of 2018, will evaluate the safety and efficacy of LCAR-B38M (JNJ-68284528). The CAR T therapy targets B-cell Maturation Antigen and expresses a CAR protein that is identical to a product that was developed by Legend Biotech and evaluated in a first-in-human clinical study in China.

The drug is being developed as part of a collaboration between Legend Biotech and Janssen Biotech.

Novel Neuroendocrine Tumor in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (FULL)

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are uncommon and can occur in the context of genetic conditions. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is an autosomal dominant disorder of the tumor suppressor gene of the same name—MEN1, which encodes for the protein menin. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 is characterized clinically by the presence of 2 or more of the following NETs: parathyroid, pituitary, and pancreaticoduodenal.1 Pancreaticoduodenal NETs occur in 30% to 80% of patients with MEN1 and have malignant potential. Although the majority of pancreaticoduodenal NETs are nonfunctioning, patients may present with symptoms secondary to mass effect.

Genetic testing exists for MEN1, but not all genetic mutations that cause MEN1 have been discovered. Therefore, because negative genetic testing does not rule out MEN1, a diagnosis is based on tumor type and location. Neuroendocrine tumors of the biliary tree are rare, and there

are no well-accepted guidelines on how to stage them.2-4 The following case demonstrates an unusual initial presentation of a NET in the context of MEN1.

Case Report

A 29-year-old, active-duty African-American man deployed in Kuwait presented with icterus, flank pain, and hematuria. His past medical history was significant for nephrolithiasis, and his family history was notable for hyperparathyroidism. Laboratory results showed primary hyperparathyroidism and evidence of biliary obstruction.

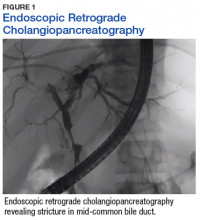

A sestamibi scan demonstrated uptake in a location corresponding with the right inferior parathyroid gland. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed nephrolithiasis and hepatic biliary ductal dilatation. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed both intra- and extrahepatic ductal dilatation, focal narrowing of the proximal common bile duct, and possible adenopathy that was concerning for cholangiocarcinoma. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated a 1 cm to 2 cm focal stricture within the mid-common bile duct with intra- and extrahepatic ductal dilatation (Figure 1). An endoscopy showed no masses in the duodenum, and anendoscopic ultrasound showed no masses in the pancreas. Endoscopic brushings and endoscopic, ultrasound-guided, fine-needle aspiration

cytology were nondiagnostic. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a dilated hepatic bile duct, an inflamed porta hepatis, and a mass involving the distal hepatic bile duct.

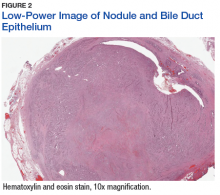

The patient underwent cholecystectomy, radical extra hepatic bile duct resection to the level of the hepatic bifurcation, and hepaticojejunostomy. Gross examination of the specimen showed a nodule centered in the distal common hepatic duct with an adjacent, 2-cm lymph node. The histologic examination revealed a neoplastic proliferation consisting of epithelioid cells with round nuclei and granular chromatin with amphophilic cytoplasm in a trabecular and nested architecture.

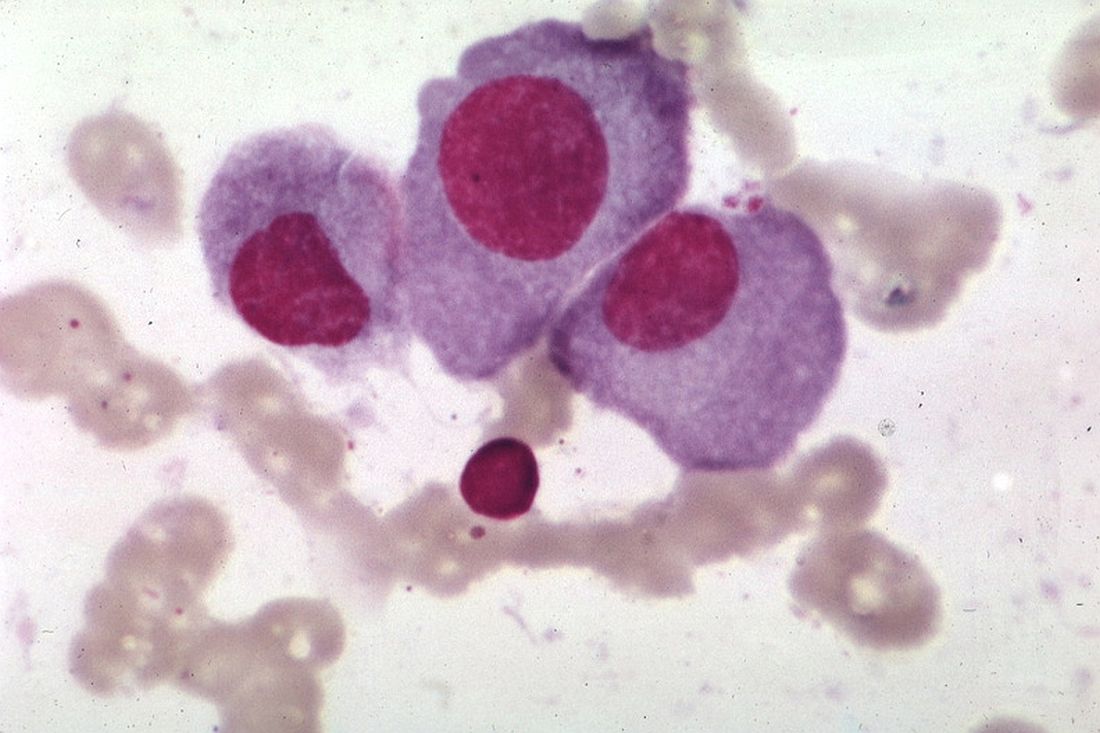

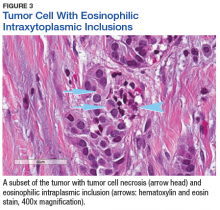

The tumor was centered in the submucosa, which is typical of gastrointestinal NETs (Figure 2). There was no evidence of direct tumor extension elsewhere. About 40% of the tumor cells contained eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusions (Figure 3). The tumor did not involve the margins or lymph node.

Positive staining with the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin and chromagranin A confirmed a well-differentiated NET. The intracytoplasmic inclusions stained strongly positive for cytokeratin CAM 5.2. The tumor had higher-grade features, including tumor cell necrosis, a Ki-67 labeling index of 3%, and perineural invasion. The 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for NET of the digestive system classified this tumor as a grade 2, well-differentiated NET and as stage 1a (limited to the bile duct).4

Postoperatively, octreotide scan with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)-CT did not show additional masses or lesions. Serum pancreatic polypeptide was elevated, with the remaining serum and plasma NET markers—including gastrin, glucagon, insulin, chromogranin A, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)—being within reference ranges. Genetic testing (GeneDx, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) showed an E563X nonsense mutation in the MEN1 gene, confirming a MEN1 disorder. The patient then underwent a 4-gland parathyroidectomy with reimplantation; the parathyroid glands demonstrated hyperplasia in all 4 glands.

Biochemical follow-up at 14 months showed that the serum pancreatic polypeptide had normalized. There was no evidence of pituitary orpancreatic hypersecretion. The patient developed hypoparathyroidism, requiring calcium and calcitriol supplementation. Radiographic follow-up using abdominal magnetic resonance imaging at 16 months showed no evidence of disease.

Discussion

This case illustrates a genetic disease with an unusual initial presentation. Primary extrahepatic bile duct NETs are rare and have been reported previously in patients without MEN1.5-9 Neuroendocrine tumors in the hepatic bile duct in patients with MEN1 also have been reported but only after these tumors first appeared in the pancreas or duodenum.10 An extensive literature search revealed no prior reports extrahepatic bile duct NETs with MEN1 as the primary site or with biliary obstruction, which is why this patient’s presentation is particularly interesting.5,6,10-13 The table summarizes select reports of NETs.

Tumor location in this patient was atypical, and genetic testing guided the management. Serum MEN1 genetic testing is indicated in patients with ≥ 2 tumors that are atypical but possibly associated with MEN1 (such as adrenal tumors, gastrinomas, and carcinoids) and in patients aged < 45 years with primary hyperparathyroidism.14,15 The patient in this study was aged 29 years and had hyperparathyroidism and an NET of the hepatic bile duct. This condition was sufficient to warrant genetic testing, the results of which affected the patient’s subsequent parathyroid surgery.15 Despite the suggestion of unifocal localization on the sestamibi scan, the patient underwent the more appropriate subtotal parathyroidectomy.14 The patient’s tumor most likely originated from a germline mutation of the MEN1 gene.

As a result of the patient’s genetic test results, his daughter also was tested. She was found to have the same mutation as her father and will undergo proper tumor surveillance for MEN1. There was no personal or family history of hemangioblastomas, renal cell carcinomas, or cystadenomas, which would have prompted testing for von Hippel-Lindau disease. Likewise, there was no personal or family history of café-au-lait macules and neurofibromas, which would have prompted testing for neurofibromatosis type 1.

Due to the paucity of cases, there are currently no well-accepted guidelines on how to stage extrahepatic biliary NETs.3-5,16 The WHO recommends staging according to adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder and bile duct.3 As such, the pathologic stage of this tumor would be stage 1a.

The significance of the intracytoplasmic inclusion in this case is unknown. Pancreatic NETs and neuroendocrine carcinomas have demonstrated intracytoplasmic inclusions that stain positively for keratin and may indicate more aggressive tumor behavior.17-19 In 1 report, electron microscopic examination demonstrated intermediate filaments with entrapped neurosecretory granules.18 In a series of 84 cases of pancreatic endocrine tumors, 14 had intracytoplasmic inclusions; of these, 5 had MEN1.17 In the present case, the patient continues to show no evidence of tumor recurrence at 16 months after resection.

Conclusion

Extrahepatic biliary neuroendocrine tumors are rare. Further investigation into biliary tree NET staging and future studies to determine the significance of intracytoplasmic inclusions may be beneficial. This case highlights the appropriate use of genetic testing and supports expanding the clinical diagnosis of MEN1 to include NETs of the extrahepatic bile duct.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011.

2. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Neuroendocrine Tumors. In: Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010:227-236.

3. Komminoth P, Arnold R, Capella C, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:274-276.

4. Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010:13.