User login

Beta-thalassemia gene therapy achieves lasting transfusion independence

, an investigator reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Among patients who received betibeglogene autotemcel (beti-cel) in a phase 3 trial and enrolled in a long-term follow-up study, nearly 90% achieved durable transfusion independence, according to Alexis A. Thompson, MD, MPH, of the hematology section at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

The median duration of ongoing transfusion independence was nearly 3 years as of this report, which Dr. Thompson described in a press conference at the meeting.

In a subanalysis of this international study, Dr. Thompson and co-investigators reported that in patients who achieve transfusion independence, chelation reduced iron, and iron markers stabilized even after chelation was stopped.

Beyond 2 years post-infusion, no adverse events related to the drug product were seen. This suggested that the therapy has a favorable long-term safety profile, according to Dr. Thompson.

“At this point, we believe that beti-cel is potentially curative for patients with TDT [transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia],” Dr. Thompson said in the press conference.

This study answers one of the major outstanding questions about beti-cel and iron metabolism, according to Arielle L. Langer, MD, MPH, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and attending physician for adult thalassemia patients at Brigham and Women’s and Dana Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston.

“Seeing the restoration of iron metabolism, it really takes us a step closer to really thinking the term ‘cure’ might truly apply,” Dr. Langer said in an interview.

Dr. Langer said she looks forward to “very long-term outcomes” of beti-cel-treated patients to see whether endocrinopathies and other long-term sequelae of TDT are also abated.

“This [study] is a great intermediate point, but really, when we think about how thalassemia harms and kills our patients, we really sometimes measure that in decades,” she said.

Beta-thalassemia is caused by mutations in the beta-globin gene, resulting in reduced levels of hemoglobin. Patients with TDT, the most serious form of the disease, have severe anemia and are often dependent on red blood cell transfusions from infancy onward, Dr. Thompson said.

With chronic transfusions needed to maintain hemoglobin levels, TDT patients inevitably experience iron overload, which can lead to organ damage and can be fatal. Consequently, patients will require lifelong iron chelation therapy, she added.

Beti-cel, an investigational ex vivo gene addition therapy currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, involves adding functional copies of a modified form of the beta-globin gene into a patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells. Once those cells are reinfused, patients may produce adult hemoglobin at levels that eliminate the need for transfusions, according to Dr. Thompson.

At the meeting, Dr. Thompson reported on patients from two phase 1/2 and two phase 3 beti-cel clinical trials who subsequently enrolled in LTF-303, a 13-year follow-up study of the gene therapy’s safety and efficacy.

A total of 57 patients were included in this report, making it the largest gene therapy program to date in any blood disorder, according to Dr. Thompson. Before receiving beti-cel, the patients, who had a broad range of thalassemia genotypes, were receiving between 10 and almost 40 red blood cell transfusions per year, she reported.

Patients ranged in age from 5 to 35 years. The median age in the phase 1/2 studies was 20 years, while in the phase 3 studies it was 15 years.

“The early experience in the phase 1/2 trials allowed us to be more comfortable with enrolling more children, and that has actually helped us to understand safety and efficacy and children in the phase 3 setting,” Dr. Thompson said.

Fertility preservation measures had been undertaken by about 59% of patients from the phase 1/2 studies and 71% of patients from the phase 3 studies, the data show.

Among patients from the phase 3 beti-cel studies who could be evaluated, 31 out of 35 (or 89%) achieved durable transfusion independence, according to the investigator.

The median duration of ongoing transfusion independence was 32 months, with a range of about 18 to 49 months, she added.

Dr. Thompson also reported a subanalysis intended to assess iron status in 16 patients who restarted and then stopped chelation. That subanalysis demonstrated iron reduction in response to chelation, and then stabilization of iron markers after chelation was stopped. Post-gene therapy chelation led to reductions in liver iron concentration and serum ferritin that remained relatively stable after chelation was stopped, she said.

Serious adverse events occurred in eight patients in the long-term follow-up study. However, adverse events related to beti-cel have been absent beyond 2 years post-infusion, according to Dr. Thompson, who added that there have been no reported cases of replication-competent lentivirus, no clonal expansion, no insertional oncogenesis, and no malignancies observed.

“Very reassuringly, there have been 2 male patients, one of whom underwent fertility preservation, who report having healthy children with their partners,” she added.

Dr. Thompson provided disclosures related to Baxalta, Biomarin, bluebird bio, Inc., Celgene/BMS, CRISPR Therapeutics, Vertex, Editas, Graphite Bio, Novartis, Agios, Beam, and Global Blood Therapeutics.

, an investigator reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Among patients who received betibeglogene autotemcel (beti-cel) in a phase 3 trial and enrolled in a long-term follow-up study, nearly 90% achieved durable transfusion independence, according to Alexis A. Thompson, MD, MPH, of the hematology section at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

The median duration of ongoing transfusion independence was nearly 3 years as of this report, which Dr. Thompson described in a press conference at the meeting.

In a subanalysis of this international study, Dr. Thompson and co-investigators reported that in patients who achieve transfusion independence, chelation reduced iron, and iron markers stabilized even after chelation was stopped.

Beyond 2 years post-infusion, no adverse events related to the drug product were seen. This suggested that the therapy has a favorable long-term safety profile, according to Dr. Thompson.

“At this point, we believe that beti-cel is potentially curative for patients with TDT [transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia],” Dr. Thompson said in the press conference.

This study answers one of the major outstanding questions about beti-cel and iron metabolism, according to Arielle L. Langer, MD, MPH, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and attending physician for adult thalassemia patients at Brigham and Women’s and Dana Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston.

“Seeing the restoration of iron metabolism, it really takes us a step closer to really thinking the term ‘cure’ might truly apply,” Dr. Langer said in an interview.

Dr. Langer said she looks forward to “very long-term outcomes” of beti-cel-treated patients to see whether endocrinopathies and other long-term sequelae of TDT are also abated.

“This [study] is a great intermediate point, but really, when we think about how thalassemia harms and kills our patients, we really sometimes measure that in decades,” she said.

Beta-thalassemia is caused by mutations in the beta-globin gene, resulting in reduced levels of hemoglobin. Patients with TDT, the most serious form of the disease, have severe anemia and are often dependent on red blood cell transfusions from infancy onward, Dr. Thompson said.

With chronic transfusions needed to maintain hemoglobin levels, TDT patients inevitably experience iron overload, which can lead to organ damage and can be fatal. Consequently, patients will require lifelong iron chelation therapy, she added.

Beti-cel, an investigational ex vivo gene addition therapy currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, involves adding functional copies of a modified form of the beta-globin gene into a patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells. Once those cells are reinfused, patients may produce adult hemoglobin at levels that eliminate the need for transfusions, according to Dr. Thompson.

At the meeting, Dr. Thompson reported on patients from two phase 1/2 and two phase 3 beti-cel clinical trials who subsequently enrolled in LTF-303, a 13-year follow-up study of the gene therapy’s safety and efficacy.

A total of 57 patients were included in this report, making it the largest gene therapy program to date in any blood disorder, according to Dr. Thompson. Before receiving beti-cel, the patients, who had a broad range of thalassemia genotypes, were receiving between 10 and almost 40 red blood cell transfusions per year, she reported.

Patients ranged in age from 5 to 35 years. The median age in the phase 1/2 studies was 20 years, while in the phase 3 studies it was 15 years.

“The early experience in the phase 1/2 trials allowed us to be more comfortable with enrolling more children, and that has actually helped us to understand safety and efficacy and children in the phase 3 setting,” Dr. Thompson said.

Fertility preservation measures had been undertaken by about 59% of patients from the phase 1/2 studies and 71% of patients from the phase 3 studies, the data show.

Among patients from the phase 3 beti-cel studies who could be evaluated, 31 out of 35 (or 89%) achieved durable transfusion independence, according to the investigator.

The median duration of ongoing transfusion independence was 32 months, with a range of about 18 to 49 months, she added.

Dr. Thompson also reported a subanalysis intended to assess iron status in 16 patients who restarted and then stopped chelation. That subanalysis demonstrated iron reduction in response to chelation, and then stabilization of iron markers after chelation was stopped. Post-gene therapy chelation led to reductions in liver iron concentration and serum ferritin that remained relatively stable after chelation was stopped, she said.

Serious adverse events occurred in eight patients in the long-term follow-up study. However, adverse events related to beti-cel have been absent beyond 2 years post-infusion, according to Dr. Thompson, who added that there have been no reported cases of replication-competent lentivirus, no clonal expansion, no insertional oncogenesis, and no malignancies observed.

“Very reassuringly, there have been 2 male patients, one of whom underwent fertility preservation, who report having healthy children with their partners,” she added.

Dr. Thompson provided disclosures related to Baxalta, Biomarin, bluebird bio, Inc., Celgene/BMS, CRISPR Therapeutics, Vertex, Editas, Graphite Bio, Novartis, Agios, Beam, and Global Blood Therapeutics.

, an investigator reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Among patients who received betibeglogene autotemcel (beti-cel) in a phase 3 trial and enrolled in a long-term follow-up study, nearly 90% achieved durable transfusion independence, according to Alexis A. Thompson, MD, MPH, of the hematology section at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

The median duration of ongoing transfusion independence was nearly 3 years as of this report, which Dr. Thompson described in a press conference at the meeting.

In a subanalysis of this international study, Dr. Thompson and co-investigators reported that in patients who achieve transfusion independence, chelation reduced iron, and iron markers stabilized even after chelation was stopped.

Beyond 2 years post-infusion, no adverse events related to the drug product were seen. This suggested that the therapy has a favorable long-term safety profile, according to Dr. Thompson.

“At this point, we believe that beti-cel is potentially curative for patients with TDT [transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia],” Dr. Thompson said in the press conference.

This study answers one of the major outstanding questions about beti-cel and iron metabolism, according to Arielle L. Langer, MD, MPH, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and attending physician for adult thalassemia patients at Brigham and Women’s and Dana Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston.

“Seeing the restoration of iron metabolism, it really takes us a step closer to really thinking the term ‘cure’ might truly apply,” Dr. Langer said in an interview.

Dr. Langer said she looks forward to “very long-term outcomes” of beti-cel-treated patients to see whether endocrinopathies and other long-term sequelae of TDT are also abated.

“This [study] is a great intermediate point, but really, when we think about how thalassemia harms and kills our patients, we really sometimes measure that in decades,” she said.

Beta-thalassemia is caused by mutations in the beta-globin gene, resulting in reduced levels of hemoglobin. Patients with TDT, the most serious form of the disease, have severe anemia and are often dependent on red blood cell transfusions from infancy onward, Dr. Thompson said.

With chronic transfusions needed to maintain hemoglobin levels, TDT patients inevitably experience iron overload, which can lead to organ damage and can be fatal. Consequently, patients will require lifelong iron chelation therapy, she added.

Beti-cel, an investigational ex vivo gene addition therapy currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, involves adding functional copies of a modified form of the beta-globin gene into a patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells. Once those cells are reinfused, patients may produce adult hemoglobin at levels that eliminate the need for transfusions, according to Dr. Thompson.

At the meeting, Dr. Thompson reported on patients from two phase 1/2 and two phase 3 beti-cel clinical trials who subsequently enrolled in LTF-303, a 13-year follow-up study of the gene therapy’s safety and efficacy.

A total of 57 patients were included in this report, making it the largest gene therapy program to date in any blood disorder, according to Dr. Thompson. Before receiving beti-cel, the patients, who had a broad range of thalassemia genotypes, were receiving between 10 and almost 40 red blood cell transfusions per year, she reported.

Patients ranged in age from 5 to 35 years. The median age in the phase 1/2 studies was 20 years, while in the phase 3 studies it was 15 years.

“The early experience in the phase 1/2 trials allowed us to be more comfortable with enrolling more children, and that has actually helped us to understand safety and efficacy and children in the phase 3 setting,” Dr. Thompson said.

Fertility preservation measures had been undertaken by about 59% of patients from the phase 1/2 studies and 71% of patients from the phase 3 studies, the data show.

Among patients from the phase 3 beti-cel studies who could be evaluated, 31 out of 35 (or 89%) achieved durable transfusion independence, according to the investigator.

The median duration of ongoing transfusion independence was 32 months, with a range of about 18 to 49 months, she added.

Dr. Thompson also reported a subanalysis intended to assess iron status in 16 patients who restarted and then stopped chelation. That subanalysis demonstrated iron reduction in response to chelation, and then stabilization of iron markers after chelation was stopped. Post-gene therapy chelation led to reductions in liver iron concentration and serum ferritin that remained relatively stable after chelation was stopped, she said.

Serious adverse events occurred in eight patients in the long-term follow-up study. However, adverse events related to beti-cel have been absent beyond 2 years post-infusion, according to Dr. Thompson, who added that there have been no reported cases of replication-competent lentivirus, no clonal expansion, no insertional oncogenesis, and no malignancies observed.

“Very reassuringly, there have been 2 male patients, one of whom underwent fertility preservation, who report having healthy children with their partners,” she added.

Dr. Thompson provided disclosures related to Baxalta, Biomarin, bluebird bio, Inc., Celgene/BMS, CRISPR Therapeutics, Vertex, Editas, Graphite Bio, Novartis, Agios, Beam, and Global Blood Therapeutics.

FROM ASH 2021

FDA approves time-saving combo for r/r multiple myeloma

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration who have had one to three prior lines of therapy.

Using the newly approved combination in this setting is a time-saver for patients and clinics, observed an investigator.

“The approval of subcutaneous daratumumab in combination with Kd will help clinicians address unmet patient needs by reducing the administration time from hours to just minutes and reducing the frequency of infusion-related reactions, as compared to the intravenous daratumumab formulation in combination with Kd,” said Ajai Chari, MD, of Mount Sinai Cancer Clinical Trials Office in New York City in a Janssen press statement.

Efficacy data for the new approval come from a single-arm cohort of PLEIADES, a multicohort, open-label trial. The cohort included 66 patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who had received one or more prior lines of therapy. Patients received daratumumab + hyaluronidase-fihj subcutaneously in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone.

The main efficacy outcome measure was overall response rate, which was 84.8%. At a median follow-up of 9.2 months, the median duration of response had not been reached.

The response rate with the new combination, which features a subcutaneous injection, was akin to those with the older combination, which features the more time-consuming IV administration and was FDA approved, according to the company press release.

The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) occurring in patients treated with Darzalex Faspro, Kyprolis, and dexamethasone were upper respiratory tract infections, fatigue, insomnia, hypertension, diarrhea, cough, dyspnea, headache, pyrexia, nausea, and edema peripheral.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration who have had one to three prior lines of therapy.

Using the newly approved combination in this setting is a time-saver for patients and clinics, observed an investigator.

“The approval of subcutaneous daratumumab in combination with Kd will help clinicians address unmet patient needs by reducing the administration time from hours to just minutes and reducing the frequency of infusion-related reactions, as compared to the intravenous daratumumab formulation in combination with Kd,” said Ajai Chari, MD, of Mount Sinai Cancer Clinical Trials Office in New York City in a Janssen press statement.

Efficacy data for the new approval come from a single-arm cohort of PLEIADES, a multicohort, open-label trial. The cohort included 66 patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who had received one or more prior lines of therapy. Patients received daratumumab + hyaluronidase-fihj subcutaneously in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone.

The main efficacy outcome measure was overall response rate, which was 84.8%. At a median follow-up of 9.2 months, the median duration of response had not been reached.

The response rate with the new combination, which features a subcutaneous injection, was akin to those with the older combination, which features the more time-consuming IV administration and was FDA approved, according to the company press release.

The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) occurring in patients treated with Darzalex Faspro, Kyprolis, and dexamethasone were upper respiratory tract infections, fatigue, insomnia, hypertension, diarrhea, cough, dyspnea, headache, pyrexia, nausea, and edema peripheral.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration who have had one to three prior lines of therapy.

Using the newly approved combination in this setting is a time-saver for patients and clinics, observed an investigator.

“The approval of subcutaneous daratumumab in combination with Kd will help clinicians address unmet patient needs by reducing the administration time from hours to just minutes and reducing the frequency of infusion-related reactions, as compared to the intravenous daratumumab formulation in combination with Kd,” said Ajai Chari, MD, of Mount Sinai Cancer Clinical Trials Office in New York City in a Janssen press statement.

Efficacy data for the new approval come from a single-arm cohort of PLEIADES, a multicohort, open-label trial. The cohort included 66 patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who had received one or more prior lines of therapy. Patients received daratumumab + hyaluronidase-fihj subcutaneously in combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone.

The main efficacy outcome measure was overall response rate, which was 84.8%. At a median follow-up of 9.2 months, the median duration of response had not been reached.

The response rate with the new combination, which features a subcutaneous injection, was akin to those with the older combination, which features the more time-consuming IV administration and was FDA approved, according to the company press release.

The most common adverse reactions (≥20%) occurring in patients treated with Darzalex Faspro, Kyprolis, and dexamethasone were upper respiratory tract infections, fatigue, insomnia, hypertension, diarrhea, cough, dyspnea, headache, pyrexia, nausea, and edema peripheral.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Decades spent searching for genes linked to rare blood cancer

Mary Lou McMaster, MD, has spent her entire career at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) searching for the genetic underpinnings that give rise to Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia (WM).

After searching for decades, she has yet to uncover a "smoking gun," though a few tantalizing clues have emerged along the way.

"Our questions are pretty basic: Why are some people more susceptible to developing WM, and why does WM sometimes cluster in families?" she explained. It turns out that the answers are not at all simple.

Dr. McMaster described some of the clues that her team at the Clinical Genetics Branch of the NCI has unearthed in a presentation at the recent International Waldenstrom's Macroglobulinemia Foundation (IWMF) 2021 Virtual Educational Forum.

Commenting after the presentation, Steven Treon, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who is collaborating with Dr. McMaster on this work, said: "From these familial studies, we can learn how familial genomics may give us insights into disease prevention and treatment."

Identifying affected families

Work began in 2001 to identify families in which two or more family members had been diagnosed with WM or in which there was one patient with WM and at least one other relative with a related B-cell cancer, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

For a frame of reference, they enrolled some families with only one member with WM and in which there was no known family history of the disease.

"Overall, we have learned that familial WM is a rare disease but not nearly as rare as we first thought," Dr. McMaster said.

For example, in a referral hospital setting, 5% of WM patients will report having a family member with the same disorder, and up to 20% of WM patients report having a family member with a related but different B-cell cancer, she noted.

NCI researchers also discovered that environmental factors contribute to the development of WM. Notable chemical or occupational exposures include exposures to pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers. Infections and autoimmune disease are additional factors.

"This was not a surprise," Dr. McMaster commented regarding the role of occupational exposures. The research community has known for decades that a "lymphoma belt" cuts through the Midwest farming states.

Focusing on genetic susceptibility, Dr. McMaster and colleagues first tried to identify a rare germline variant that can be passed down to offspring and that might confer high risk for the disease.

"We used our high-risk families to study these types of changes, although they may be modified by other genes and environmental factors," Dr. McMaster explained.

Much to their collective disappointment, the research team has been unable to identify any rare germline variant that could account for WM in many families. What they did find were many small changes in genes that are known to be important in B-cell development and function, but all of those would lead to only a small increase in WM risk.

"What is holding us back is that, so far, we are not seeing the same gene affected in more than one family, so this suggests to us either that this is not the mechanism behind the development of WM in families, or we have an unfortunate situation where each family is going to have a genetic change that is private to that family and which is not found in other families," Dr. McMaster acknowledged.

Sheer difficulty

Given the difficulty of determining whether these small genetic changes had any detrimental functional effect in each and every family with a member who had WM, Dr. McMaster and colleagues have now turned their attention to genes that exert only a small effect on disease risk.

"Here, we focused on specific genes that we knew were important in the function of the immune system," she explained. "We did find a few genes that may contribute to risk, but those have not yet been confirmed by us or others, and we cannot say they are causative without that confirmation," she said.

The team has gone on to scan the highway of our genetic material so as to isolate genetic "mile markers." They then examine the area around a particular marker that they suspect contains genes that may be involved in WM.

One study they conducted involved a cohort of 217 patients with WM in which numerous family members had WM and so was enriched with susceptibility genes. A second cohort comprised 312 WM patients in which there were few WM cases among family members. Both of these cohorts were compared with a group of healthy control persons.

From these genome studies, "we found there are at least two regions of the genome that can contribute to WM susceptibility, the largest effect being on the short arm of chromosome 6, and the other on the long arm of chromosome 14," Dr. McMaster reported. Dr. McMaster feels that there are probably more regions on the genome that also contribute to WM, although they do not yet understand how these regions contribute to susceptibility.

"It's more evidence that WM likely results from a combination of events rather than one single gene variant," she observed. Dr. McMaster and colleagues are now collaborating with a large consortium of WM researchers to confirm and extend their findings. Plans are underway to analyze data from approximately 1,350 WM patients and more than 20,000 control persons within the next year.

"Our hope is that we will confirm our original findings and, because we now have a much larger sample, we will be able to discover additional regions of the genome that are contributing to susceptibility," Dr. McMaster said.

"A single gene is not likely to account for all WM, as we've looked carefully and others have looked too," she commented.

"So the risk for WM depends on a combination of genes and environmental exposures and possibly lifestyle factors as well, although we still estimate that approximately 25% of the heritability of WM can be attributed to these kinds of genetic changes," Dr. McMaster predicted.

Dr. McMaster has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Treon has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Janssen, Pfizer, PCYC, and BioGene.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

Mary Lou McMaster, MD, has spent her entire career at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) searching for the genetic underpinnings that give rise to Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia (WM).

After searching for decades, she has yet to uncover a "smoking gun," though a few tantalizing clues have emerged along the way.

"Our questions are pretty basic: Why are some people more susceptible to developing WM, and why does WM sometimes cluster in families?" she explained. It turns out that the answers are not at all simple.

Dr. McMaster described some of the clues that her team at the Clinical Genetics Branch of the NCI has unearthed in a presentation at the recent International Waldenstrom's Macroglobulinemia Foundation (IWMF) 2021 Virtual Educational Forum.

Commenting after the presentation, Steven Treon, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who is collaborating with Dr. McMaster on this work, said: "From these familial studies, we can learn how familial genomics may give us insights into disease prevention and treatment."

Identifying affected families

Work began in 2001 to identify families in which two or more family members had been diagnosed with WM or in which there was one patient with WM and at least one other relative with a related B-cell cancer, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

For a frame of reference, they enrolled some families with only one member with WM and in which there was no known family history of the disease.

"Overall, we have learned that familial WM is a rare disease but not nearly as rare as we first thought," Dr. McMaster said.

For example, in a referral hospital setting, 5% of WM patients will report having a family member with the same disorder, and up to 20% of WM patients report having a family member with a related but different B-cell cancer, she noted.

NCI researchers also discovered that environmental factors contribute to the development of WM. Notable chemical or occupational exposures include exposures to pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers. Infections and autoimmune disease are additional factors.

"This was not a surprise," Dr. McMaster commented regarding the role of occupational exposures. The research community has known for decades that a "lymphoma belt" cuts through the Midwest farming states.

Focusing on genetic susceptibility, Dr. McMaster and colleagues first tried to identify a rare germline variant that can be passed down to offspring and that might confer high risk for the disease.

"We used our high-risk families to study these types of changes, although they may be modified by other genes and environmental factors," Dr. McMaster explained.

Much to their collective disappointment, the research team has been unable to identify any rare germline variant that could account for WM in many families. What they did find were many small changes in genes that are known to be important in B-cell development and function, but all of those would lead to only a small increase in WM risk.

"What is holding us back is that, so far, we are not seeing the same gene affected in more than one family, so this suggests to us either that this is not the mechanism behind the development of WM in families, or we have an unfortunate situation where each family is going to have a genetic change that is private to that family and which is not found in other families," Dr. McMaster acknowledged.

Sheer difficulty

Given the difficulty of determining whether these small genetic changes had any detrimental functional effect in each and every family with a member who had WM, Dr. McMaster and colleagues have now turned their attention to genes that exert only a small effect on disease risk.

"Here, we focused on specific genes that we knew were important in the function of the immune system," she explained. "We did find a few genes that may contribute to risk, but those have not yet been confirmed by us or others, and we cannot say they are causative without that confirmation," she said.

The team has gone on to scan the highway of our genetic material so as to isolate genetic "mile markers." They then examine the area around a particular marker that they suspect contains genes that may be involved in WM.

One study they conducted involved a cohort of 217 patients with WM in which numerous family members had WM and so was enriched with susceptibility genes. A second cohort comprised 312 WM patients in which there were few WM cases among family members. Both of these cohorts were compared with a group of healthy control persons.

From these genome studies, "we found there are at least two regions of the genome that can contribute to WM susceptibility, the largest effect being on the short arm of chromosome 6, and the other on the long arm of chromosome 14," Dr. McMaster reported. Dr. McMaster feels that there are probably more regions on the genome that also contribute to WM, although they do not yet understand how these regions contribute to susceptibility.

"It's more evidence that WM likely results from a combination of events rather than one single gene variant," she observed. Dr. McMaster and colleagues are now collaborating with a large consortium of WM researchers to confirm and extend their findings. Plans are underway to analyze data from approximately 1,350 WM patients and more than 20,000 control persons within the next year.

"Our hope is that we will confirm our original findings and, because we now have a much larger sample, we will be able to discover additional regions of the genome that are contributing to susceptibility," Dr. McMaster said.

"A single gene is not likely to account for all WM, as we've looked carefully and others have looked too," she commented.

"So the risk for WM depends on a combination of genes and environmental exposures and possibly lifestyle factors as well, although we still estimate that approximately 25% of the heritability of WM can be attributed to these kinds of genetic changes," Dr. McMaster predicted.

Dr. McMaster has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Treon has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Janssen, Pfizer, PCYC, and BioGene.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

Mary Lou McMaster, MD, has spent her entire career at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) searching for the genetic underpinnings that give rise to Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia (WM).

After searching for decades, she has yet to uncover a "smoking gun," though a few tantalizing clues have emerged along the way.

"Our questions are pretty basic: Why are some people more susceptible to developing WM, and why does WM sometimes cluster in families?" she explained. It turns out that the answers are not at all simple.

Dr. McMaster described some of the clues that her team at the Clinical Genetics Branch of the NCI has unearthed in a presentation at the recent International Waldenstrom's Macroglobulinemia Foundation (IWMF) 2021 Virtual Educational Forum.

Commenting after the presentation, Steven Treon, MD, PhD, professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who is collaborating with Dr. McMaster on this work, said: "From these familial studies, we can learn how familial genomics may give us insights into disease prevention and treatment."

Identifying affected families

Work began in 2001 to identify families in which two or more family members had been diagnosed with WM or in which there was one patient with WM and at least one other relative with a related B-cell cancer, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

For a frame of reference, they enrolled some families with only one member with WM and in which there was no known family history of the disease.

"Overall, we have learned that familial WM is a rare disease but not nearly as rare as we first thought," Dr. McMaster said.

For example, in a referral hospital setting, 5% of WM patients will report having a family member with the same disorder, and up to 20% of WM patients report having a family member with a related but different B-cell cancer, she noted.

NCI researchers also discovered that environmental factors contribute to the development of WM. Notable chemical or occupational exposures include exposures to pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers. Infections and autoimmune disease are additional factors.

"This was not a surprise," Dr. McMaster commented regarding the role of occupational exposures. The research community has known for decades that a "lymphoma belt" cuts through the Midwest farming states.

Focusing on genetic susceptibility, Dr. McMaster and colleagues first tried to identify a rare germline variant that can be passed down to offspring and that might confer high risk for the disease.

"We used our high-risk families to study these types of changes, although they may be modified by other genes and environmental factors," Dr. McMaster explained.

Much to their collective disappointment, the research team has been unable to identify any rare germline variant that could account for WM in many families. What they did find were many small changes in genes that are known to be important in B-cell development and function, but all of those would lead to only a small increase in WM risk.

"What is holding us back is that, so far, we are not seeing the same gene affected in more than one family, so this suggests to us either that this is not the mechanism behind the development of WM in families, or we have an unfortunate situation where each family is going to have a genetic change that is private to that family and which is not found in other families," Dr. McMaster acknowledged.

Sheer difficulty

Given the difficulty of determining whether these small genetic changes had any detrimental functional effect in each and every family with a member who had WM, Dr. McMaster and colleagues have now turned their attention to genes that exert only a small effect on disease risk.

"Here, we focused on specific genes that we knew were important in the function of the immune system," she explained. "We did find a few genes that may contribute to risk, but those have not yet been confirmed by us or others, and we cannot say they are causative without that confirmation," she said.

The team has gone on to scan the highway of our genetic material so as to isolate genetic "mile markers." They then examine the area around a particular marker that they suspect contains genes that may be involved in WM.

One study they conducted involved a cohort of 217 patients with WM in which numerous family members had WM and so was enriched with susceptibility genes. A second cohort comprised 312 WM patients in which there were few WM cases among family members. Both of these cohorts were compared with a group of healthy control persons.

From these genome studies, "we found there are at least two regions of the genome that can contribute to WM susceptibility, the largest effect being on the short arm of chromosome 6, and the other on the long arm of chromosome 14," Dr. McMaster reported. Dr. McMaster feels that there are probably more regions on the genome that also contribute to WM, although they do not yet understand how these regions contribute to susceptibility.

"It's more evidence that WM likely results from a combination of events rather than one single gene variant," she observed. Dr. McMaster and colleagues are now collaborating with a large consortium of WM researchers to confirm and extend their findings. Plans are underway to analyze data from approximately 1,350 WM patients and more than 20,000 control persons within the next year.

"Our hope is that we will confirm our original findings and, because we now have a much larger sample, we will be able to discover additional regions of the genome that are contributing to susceptibility," Dr. McMaster said.

"A single gene is not likely to account for all WM, as we've looked carefully and others have looked too," she commented.

"So the risk for WM depends on a combination of genes and environmental exposures and possibly lifestyle factors as well, although we still estimate that approximately 25% of the heritability of WM can be attributed to these kinds of genetic changes," Dr. McMaster predicted.

Dr. McMaster has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Treon has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Janssen, Pfizer, PCYC, and BioGene.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com

Orbital Varix Masquerading as an Intraorbital Lymphoma

Clinical context was paramount to the diagnosis and management of a patient with periorbital pain and a history of systemic lymphoma.

We present a case of an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. Our case underscores the importance of clinical correlation and thorough study of the ordered films by the ordering health care provider.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old female veteran presented to the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System emergency department. She had a past ocular history of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy in both eyes (OU) and senile cataracts OU. She had a complicated medical history most notable for congestive heart failure and Stage IV B cell follicular lymphoma, having received 6 rounds of chemotherapy, and has since been on rituximab maintenance therapy for the past few years.

The patient reported dyspnea on exertion, 30-pound weight gain, and ocular pain in her right eye (OD), more so than her left eye (OS) that was severe enough to wake her from sleep. She endorsed an associated headache but reported no visual loss or any other ocular symptoms other than conjunctival injection. On examination, the patient demonstrated jugular venous distension. X-ray imaging obtained in the emergency department demonstrated bilateral pleural effusions. Our patient was admitted subsequently for an exacerbation of congestive heart failure. She was monitored for euvolemia and discharged 4 days later.

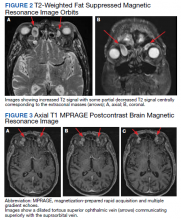

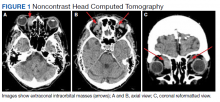

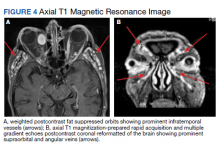

During admission, imaging of the orbits was obtained. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast demonstrated at least 4 intraorbital masses in the right orbit, measuring up to 22 mm in maximum diameter and at least 3 intraorbital masses in the left orbit, measuring up to 16 mm in diameter (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast of the brain and orbits was ordered, which demonstrated multiple bilateral uniformly enhancing, primarily extraconal masses present in both orbits, the largest of which occupied the superomedial aspect of the right orbit and measured 12 x 18 x 20 mm. Further, the ophthalmic veins were noted to be engorged. The cavernous did not demonstrate any thrombosis. No other ocular structures were compromised, although there was compression of the extraocular muscles in both orbits (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). At that time, the reading radiologist suggested the most likely diagnosis was metastatic orbital lymphoma given the clinical history, which became the working diagnosis.

A few days after admission, the patient received an ophthalmic evaluation at the eye clinic. Visual acuity (VA) at this time was 20/200 that pinholed (PH) 20/70 OD and 20/30 without pinhole improvement OS. Refraction was -2.50 + 1.50 × 120 OD and -0.25 + 0.50 × 065 OS, which yielded visual acuities of 20/60 and 20/30, respectively. There was no afferent pupillary defect and pupils were symmetric. Goldmann tonometry demonstrated pressures of 11 mm of mercury OU at 1630. Slit-lamp and dilated fundus examinations were within normal limits except for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts, large cups of 0.6 OD and 0.7 OS, and a mild epiretinal membrane OD. The decision was made to refer the patient to oculoplastic service for biopsy of the lesion to rule out a metastatic lymphoid solid tumor. At this juncture, the working diagnosis continued to be metastatic orbital lymphoma.

The patient underwent right anterior orbitotomy. Intraoperatively, after dissection to the lesion was accomplished, it was noted that the mass displayed a blue to purple hue consistent with a vascular malformation. It was decided to continue careful dissection instead of obtaining a biopsy. Continued dissection further corroborated a vascular lesion. Meticulous hemostasis was maintained during the dissection; however, dissection was halted after about 35-mm depth into the orbit, given concern for damaging the optic nerve. The feeding vessel to the lesion was tied off with two 5-0 vicryl sutures, and the specimen was cut distal to the ligation. During the procedure, pupillary function was continually checked. The rest of the surgery proceeded without any difficulty, and the specimen was sent off to pathology.

Pathology returned as an orbital varix with no thrombosis or malignant tissue. Surgery to remove lesions of the left orbit was deferred given radiologic findings consistent with vascular lesions, similar to the removed lesion from the right orbit. The patient is currently without residual periorbital pain after diuresis, and the patient’s oncological management continues to be maintenance rituximab. The remaining lesions will be monitored with yearly serial imaging.

Discussion

In a study of 242 patients, Bacorn and colleagues found that a clinician’s preoperative assessment correlated with histopathologic diagnosis in 75.7% of cases, whereas the radiology report was correct in only 52.4% of cases.1 Retrospective analysis identified clues that could have been used to more rapidly elucidate the true diagnosis for our patient.

In regard to symptomatology, orbital varices present with intermittent proptosis, vision loss, and rarely, periorbital pain unless thrombosed.2,3 The severity of periorbital pain experienced by our patient is atypical of an orbital varix especially in the absence of a phlebolith. A specific feature of orbital varix is enlargement with the Valsalva maneuver.3 Although the patient did not report the notedsymptoms, more pointed questioning may have helped elucidate our patient’s true diagnosis sooner.

Radiologically, the presence of a partial flow void (decreased signal on T2) is useful for confirming the vascular nature of a lesion as was present in our case. Specific to the radiologic evaluation of orbital varices, it is recommended to obtain imaging with and without the Valsalva maneuver.4 Ultrasound is a superb tool in our armamentarium to image orbital lesions. B-scan ultrasound with and without Valsalva should be able to demonstrate variation in size when standing (minimal distension) vs lying flat with Valsalva (maximal distension).4 Further, Doppler ultrasound would be able to demonstrate changes in flow within the lesion when comparing previously mentioned maneuvers.4 Orbital lymphoma would not demonstrate this variation.

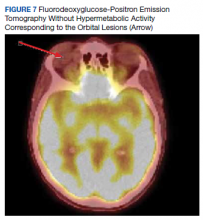

The size change of an orbital varix lesion may be further demonstrated on head CT with contrast. On CT, an orbital varix will demonstrate isodensity to other venous structures, whereas orbital lymphomas will be hyperdense when compared to extraocular muscles.4,5 Further, a head CT without contrast may demonstrate phleboliths within an orbital varix.4 MRI should be performed with the Valsalva maneuver. On T1 and T2 studies, orbital varices demonstrate hypointensity when compared to extraocular muscles (EOMs).4 Lymphomas demonstrate a very specific radiologic pattern on MRI. On T1, they demonstrate isointensity to hypointensity when compared to EOMS, and on T2, they demonstrate iso- to hyperintensity when compared to EOMs.5 With respect to fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), our patient’s orbital lesion did not demonstrate FDG uptake. In patients where lymphoma previously demonstrated FDG PET uptake, the absence of such uptake strongly argues against malignant nature of the lesion (Figure 7).

Prominently enhancing lesions are more likely to represent varices, aneurysms, or other highly or completely vascular lesions. Any intraorbital intervention should be conducted as though a vascular lesion is within the differential, and appropriate care should be taken even if not specifically enunciated in the radiologic report.

Management of orbital varices is not standardized; however, these lesions tend to be observed if no significant proptosis, pain, thrombosis, diplopia, or compression of the optic nerve is present. In such cases, surgical intervention is performed; however, the lesions may recur. Our patient’s presentation coincided with her heart failure exacerbation most likely secondary to flow disruption and fluid overload in the venous system, thereby exacerbating her orbital varices. The resolution of our patient’s orbital pain in the left orbit was likely due to improved distension after achieving euvolemia after diuresis. In cases where varices are secondary to a correctable etiologies, treatment of these etiologies are in order. Chen and colleagues reported a case of pulsatile proptosis associated with fluid overload in a newly diagnosed case of heart failure secondary to mitral regurgitation.6 Thus, orbital pain due to worsened orbital varices may represent a symptom of fluid overload and the provider may look for etiologies of this disease process.

Conclusions

We present a case of an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. While the ruling out of a diagnosis that might portend a poor prognosis is always of paramount importance, proper use of investigative studies and a thorough history could have helped elucidate the true diagnosis sooner: In this case an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. Mainly, the use of the Valsalva maneuver during the physical examination (resulting in proptosis) and during radiologic studies might have obviated the need for formal biopsy. Furthermore, orbital pain may be a presenting symptom of fluid overload in patients with a history of orbital varices.

1. Bacorn C, Gokoffski KK, Lin LK. Clinical correlation recommended: accuracy of clinician versus radiologic interpretation of the imaging of orbital lesions. Orbit. 2021;40(2):133-137. doi:10.1080/01676830.2020.1752742

2. Shams PN, Cugati S, Wells T, Huilgol S, Selva D. Orbital varix thrombosis and review of orbital vascular anomalies in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(4):e82-e86. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000107

3. Islam N, Mireskandari K, Rose GE. Orbital varices and orbital wall defects. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(8):1092-1093.

4. Smoker WR, Gentry LR, Yee NK, Reede DL, Nerad JA. Vascular lesions of the orbit: more than meets the eye. Radiographics. 2008;28(1):185-325. doi:10.1148/rg.281075040

5. Karcioglu ZA, ed. Orbital Tumors. New York; 2005. Chap 13:133-140.

6. Chen Z, Jones H. A case of tricuspid regurgitation and congestive cardiac failure presenting with orbital pulsation. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;1(1):cvd.2012.012005. Published 2012 Apr 5. doi:10.1258/cvd.2012.012005

Clinical context was paramount to the diagnosis and management of a patient with periorbital pain and a history of systemic lymphoma.

Clinical context was paramount to the diagnosis and management of a patient with periorbital pain and a history of systemic lymphoma.

We present a case of an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. Our case underscores the importance of clinical correlation and thorough study of the ordered films by the ordering health care provider.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old female veteran presented to the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System emergency department. She had a past ocular history of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy in both eyes (OU) and senile cataracts OU. She had a complicated medical history most notable for congestive heart failure and Stage IV B cell follicular lymphoma, having received 6 rounds of chemotherapy, and has since been on rituximab maintenance therapy for the past few years.

The patient reported dyspnea on exertion, 30-pound weight gain, and ocular pain in her right eye (OD), more so than her left eye (OS) that was severe enough to wake her from sleep. She endorsed an associated headache but reported no visual loss or any other ocular symptoms other than conjunctival injection. On examination, the patient demonstrated jugular venous distension. X-ray imaging obtained in the emergency department demonstrated bilateral pleural effusions. Our patient was admitted subsequently for an exacerbation of congestive heart failure. She was monitored for euvolemia and discharged 4 days later.

During admission, imaging of the orbits was obtained. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast demonstrated at least 4 intraorbital masses in the right orbit, measuring up to 22 mm in maximum diameter and at least 3 intraorbital masses in the left orbit, measuring up to 16 mm in diameter (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast of the brain and orbits was ordered, which demonstrated multiple bilateral uniformly enhancing, primarily extraconal masses present in both orbits, the largest of which occupied the superomedial aspect of the right orbit and measured 12 x 18 x 20 mm. Further, the ophthalmic veins were noted to be engorged. The cavernous did not demonstrate any thrombosis. No other ocular structures were compromised, although there was compression of the extraocular muscles in both orbits (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). At that time, the reading radiologist suggested the most likely diagnosis was metastatic orbital lymphoma given the clinical history, which became the working diagnosis.

A few days after admission, the patient received an ophthalmic evaluation at the eye clinic. Visual acuity (VA) at this time was 20/200 that pinholed (PH) 20/70 OD and 20/30 without pinhole improvement OS. Refraction was -2.50 + 1.50 × 120 OD and -0.25 + 0.50 × 065 OS, which yielded visual acuities of 20/60 and 20/30, respectively. There was no afferent pupillary defect and pupils were symmetric. Goldmann tonometry demonstrated pressures of 11 mm of mercury OU at 1630. Slit-lamp and dilated fundus examinations were within normal limits except for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts, large cups of 0.6 OD and 0.7 OS, and a mild epiretinal membrane OD. The decision was made to refer the patient to oculoplastic service for biopsy of the lesion to rule out a metastatic lymphoid solid tumor. At this juncture, the working diagnosis continued to be metastatic orbital lymphoma.

The patient underwent right anterior orbitotomy. Intraoperatively, after dissection to the lesion was accomplished, it was noted that the mass displayed a blue to purple hue consistent with a vascular malformation. It was decided to continue careful dissection instead of obtaining a biopsy. Continued dissection further corroborated a vascular lesion. Meticulous hemostasis was maintained during the dissection; however, dissection was halted after about 35-mm depth into the orbit, given concern for damaging the optic nerve. The feeding vessel to the lesion was tied off with two 5-0 vicryl sutures, and the specimen was cut distal to the ligation. During the procedure, pupillary function was continually checked. The rest of the surgery proceeded without any difficulty, and the specimen was sent off to pathology.

Pathology returned as an orbital varix with no thrombosis or malignant tissue. Surgery to remove lesions of the left orbit was deferred given radiologic findings consistent with vascular lesions, similar to the removed lesion from the right orbit. The patient is currently without residual periorbital pain after diuresis, and the patient’s oncological management continues to be maintenance rituximab. The remaining lesions will be monitored with yearly serial imaging.

Discussion

In a study of 242 patients, Bacorn and colleagues found that a clinician’s preoperative assessment correlated with histopathologic diagnosis in 75.7% of cases, whereas the radiology report was correct in only 52.4% of cases.1 Retrospective analysis identified clues that could have been used to more rapidly elucidate the true diagnosis for our patient.

In regard to symptomatology, orbital varices present with intermittent proptosis, vision loss, and rarely, periorbital pain unless thrombosed.2,3 The severity of periorbital pain experienced by our patient is atypical of an orbital varix especially in the absence of a phlebolith. A specific feature of orbital varix is enlargement with the Valsalva maneuver.3 Although the patient did not report the notedsymptoms, more pointed questioning may have helped elucidate our patient’s true diagnosis sooner.

Radiologically, the presence of a partial flow void (decreased signal on T2) is useful for confirming the vascular nature of a lesion as was present in our case. Specific to the radiologic evaluation of orbital varices, it is recommended to obtain imaging with and without the Valsalva maneuver.4 Ultrasound is a superb tool in our armamentarium to image orbital lesions. B-scan ultrasound with and without Valsalva should be able to demonstrate variation in size when standing (minimal distension) vs lying flat with Valsalva (maximal distension).4 Further, Doppler ultrasound would be able to demonstrate changes in flow within the lesion when comparing previously mentioned maneuvers.4 Orbital lymphoma would not demonstrate this variation.

The size change of an orbital varix lesion may be further demonstrated on head CT with contrast. On CT, an orbital varix will demonstrate isodensity to other venous structures, whereas orbital lymphomas will be hyperdense when compared to extraocular muscles.4,5 Further, a head CT without contrast may demonstrate phleboliths within an orbital varix.4 MRI should be performed with the Valsalva maneuver. On T1 and T2 studies, orbital varices demonstrate hypointensity when compared to extraocular muscles (EOMs).4 Lymphomas demonstrate a very specific radiologic pattern on MRI. On T1, they demonstrate isointensity to hypointensity when compared to EOMS, and on T2, they demonstrate iso- to hyperintensity when compared to EOMs.5 With respect to fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), our patient’s orbital lesion did not demonstrate FDG uptake. In patients where lymphoma previously demonstrated FDG PET uptake, the absence of such uptake strongly argues against malignant nature of the lesion (Figure 7).

Prominently enhancing lesions are more likely to represent varices, aneurysms, or other highly or completely vascular lesions. Any intraorbital intervention should be conducted as though a vascular lesion is within the differential, and appropriate care should be taken even if not specifically enunciated in the radiologic report.

Management of orbital varices is not standardized; however, these lesions tend to be observed if no significant proptosis, pain, thrombosis, diplopia, or compression of the optic nerve is present. In such cases, surgical intervention is performed; however, the lesions may recur. Our patient’s presentation coincided with her heart failure exacerbation most likely secondary to flow disruption and fluid overload in the venous system, thereby exacerbating her orbital varices. The resolution of our patient’s orbital pain in the left orbit was likely due to improved distension after achieving euvolemia after diuresis. In cases where varices are secondary to a correctable etiologies, treatment of these etiologies are in order. Chen and colleagues reported a case of pulsatile proptosis associated with fluid overload in a newly diagnosed case of heart failure secondary to mitral regurgitation.6 Thus, orbital pain due to worsened orbital varices may represent a symptom of fluid overload and the provider may look for etiologies of this disease process.

Conclusions

We present a case of an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. While the ruling out of a diagnosis that might portend a poor prognosis is always of paramount importance, proper use of investigative studies and a thorough history could have helped elucidate the true diagnosis sooner: In this case an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. Mainly, the use of the Valsalva maneuver during the physical examination (resulting in proptosis) and during radiologic studies might have obviated the need for formal biopsy. Furthermore, orbital pain may be a presenting symptom of fluid overload in patients with a history of orbital varices.

We present a case of an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. Our case underscores the importance of clinical correlation and thorough study of the ordered films by the ordering health care provider.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old female veteran presented to the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System emergency department. She had a past ocular history of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy in both eyes (OU) and senile cataracts OU. She had a complicated medical history most notable for congestive heart failure and Stage IV B cell follicular lymphoma, having received 6 rounds of chemotherapy, and has since been on rituximab maintenance therapy for the past few years.

The patient reported dyspnea on exertion, 30-pound weight gain, and ocular pain in her right eye (OD), more so than her left eye (OS) that was severe enough to wake her from sleep. She endorsed an associated headache but reported no visual loss or any other ocular symptoms other than conjunctival injection. On examination, the patient demonstrated jugular venous distension. X-ray imaging obtained in the emergency department demonstrated bilateral pleural effusions. Our patient was admitted subsequently for an exacerbation of congestive heart failure. She was monitored for euvolemia and discharged 4 days later.

During admission, imaging of the orbits was obtained. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast demonstrated at least 4 intraorbital masses in the right orbit, measuring up to 22 mm in maximum diameter and at least 3 intraorbital masses in the left orbit, measuring up to 16 mm in diameter (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast of the brain and orbits was ordered, which demonstrated multiple bilateral uniformly enhancing, primarily extraconal masses present in both orbits, the largest of which occupied the superomedial aspect of the right orbit and measured 12 x 18 x 20 mm. Further, the ophthalmic veins were noted to be engorged. The cavernous did not demonstrate any thrombosis. No other ocular structures were compromised, although there was compression of the extraocular muscles in both orbits (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). At that time, the reading radiologist suggested the most likely diagnosis was metastatic orbital lymphoma given the clinical history, which became the working diagnosis.

A few days after admission, the patient received an ophthalmic evaluation at the eye clinic. Visual acuity (VA) at this time was 20/200 that pinholed (PH) 20/70 OD and 20/30 without pinhole improvement OS. Refraction was -2.50 + 1.50 × 120 OD and -0.25 + 0.50 × 065 OS, which yielded visual acuities of 20/60 and 20/30, respectively. There was no afferent pupillary defect and pupils were symmetric. Goldmann tonometry demonstrated pressures of 11 mm of mercury OU at 1630. Slit-lamp and dilated fundus examinations were within normal limits except for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts, large cups of 0.6 OD and 0.7 OS, and a mild epiretinal membrane OD. The decision was made to refer the patient to oculoplastic service for biopsy of the lesion to rule out a metastatic lymphoid solid tumor. At this juncture, the working diagnosis continued to be metastatic orbital lymphoma.

The patient underwent right anterior orbitotomy. Intraoperatively, after dissection to the lesion was accomplished, it was noted that the mass displayed a blue to purple hue consistent with a vascular malformation. It was decided to continue careful dissection instead of obtaining a biopsy. Continued dissection further corroborated a vascular lesion. Meticulous hemostasis was maintained during the dissection; however, dissection was halted after about 35-mm depth into the orbit, given concern for damaging the optic nerve. The feeding vessel to the lesion was tied off with two 5-0 vicryl sutures, and the specimen was cut distal to the ligation. During the procedure, pupillary function was continually checked. The rest of the surgery proceeded without any difficulty, and the specimen was sent off to pathology.

Pathology returned as an orbital varix with no thrombosis or malignant tissue. Surgery to remove lesions of the left orbit was deferred given radiologic findings consistent with vascular lesions, similar to the removed lesion from the right orbit. The patient is currently without residual periorbital pain after diuresis, and the patient’s oncological management continues to be maintenance rituximab. The remaining lesions will be monitored with yearly serial imaging.

Discussion

In a study of 242 patients, Bacorn and colleagues found that a clinician’s preoperative assessment correlated with histopathologic diagnosis in 75.7% of cases, whereas the radiology report was correct in only 52.4% of cases.1 Retrospective analysis identified clues that could have been used to more rapidly elucidate the true diagnosis for our patient.

In regard to symptomatology, orbital varices present with intermittent proptosis, vision loss, and rarely, periorbital pain unless thrombosed.2,3 The severity of periorbital pain experienced by our patient is atypical of an orbital varix especially in the absence of a phlebolith. A specific feature of orbital varix is enlargement with the Valsalva maneuver.3 Although the patient did not report the notedsymptoms, more pointed questioning may have helped elucidate our patient’s true diagnosis sooner.

Radiologically, the presence of a partial flow void (decreased signal on T2) is useful for confirming the vascular nature of a lesion as was present in our case. Specific to the radiologic evaluation of orbital varices, it is recommended to obtain imaging with and without the Valsalva maneuver.4 Ultrasound is a superb tool in our armamentarium to image orbital lesions. B-scan ultrasound with and without Valsalva should be able to demonstrate variation in size when standing (minimal distension) vs lying flat with Valsalva (maximal distension).4 Further, Doppler ultrasound would be able to demonstrate changes in flow within the lesion when comparing previously mentioned maneuvers.4 Orbital lymphoma would not demonstrate this variation.

The size change of an orbital varix lesion may be further demonstrated on head CT with contrast. On CT, an orbital varix will demonstrate isodensity to other venous structures, whereas orbital lymphomas will be hyperdense when compared to extraocular muscles.4,5 Further, a head CT without contrast may demonstrate phleboliths within an orbital varix.4 MRI should be performed with the Valsalva maneuver. On T1 and T2 studies, orbital varices demonstrate hypointensity when compared to extraocular muscles (EOMs).4 Lymphomas demonstrate a very specific radiologic pattern on MRI. On T1, they demonstrate isointensity to hypointensity when compared to EOMS, and on T2, they demonstrate iso- to hyperintensity when compared to EOMs.5 With respect to fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), our patient’s orbital lesion did not demonstrate FDG uptake. In patients where lymphoma previously demonstrated FDG PET uptake, the absence of such uptake strongly argues against malignant nature of the lesion (Figure 7).

Prominently enhancing lesions are more likely to represent varices, aneurysms, or other highly or completely vascular lesions. Any intraorbital intervention should be conducted as though a vascular lesion is within the differential, and appropriate care should be taken even if not specifically enunciated in the radiologic report.

Management of orbital varices is not standardized; however, these lesions tend to be observed if no significant proptosis, pain, thrombosis, diplopia, or compression of the optic nerve is present. In such cases, surgical intervention is performed; however, the lesions may recur. Our patient’s presentation coincided with her heart failure exacerbation most likely secondary to flow disruption and fluid overload in the venous system, thereby exacerbating her orbital varices. The resolution of our patient’s orbital pain in the left orbit was likely due to improved distension after achieving euvolemia after diuresis. In cases where varices are secondary to a correctable etiologies, treatment of these etiologies are in order. Chen and colleagues reported a case of pulsatile proptosis associated with fluid overload in a newly diagnosed case of heart failure secondary to mitral regurgitation.6 Thus, orbital pain due to worsened orbital varices may represent a symptom of fluid overload and the provider may look for etiologies of this disease process.

Conclusions

We present a case of an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. While the ruling out of a diagnosis that might portend a poor prognosis is always of paramount importance, proper use of investigative studies and a thorough history could have helped elucidate the true diagnosis sooner: In this case an orbital varix masquerading as an orbital lymphoma. Mainly, the use of the Valsalva maneuver during the physical examination (resulting in proptosis) and during radiologic studies might have obviated the need for formal biopsy. Furthermore, orbital pain may be a presenting symptom of fluid overload in patients with a history of orbital varices.

1. Bacorn C, Gokoffski KK, Lin LK. Clinical correlation recommended: accuracy of clinician versus radiologic interpretation of the imaging of orbital lesions. Orbit. 2021;40(2):133-137. doi:10.1080/01676830.2020.1752742

2. Shams PN, Cugati S, Wells T, Huilgol S, Selva D. Orbital varix thrombosis and review of orbital vascular anomalies in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(4):e82-e86. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000107

3. Islam N, Mireskandari K, Rose GE. Orbital varices and orbital wall defects. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(8):1092-1093.

4. Smoker WR, Gentry LR, Yee NK, Reede DL, Nerad JA. Vascular lesions of the orbit: more than meets the eye. Radiographics. 2008;28(1):185-325. doi:10.1148/rg.281075040

5. Karcioglu ZA, ed. Orbital Tumors. New York; 2005. Chap 13:133-140.

6. Chen Z, Jones H. A case of tricuspid regurgitation and congestive cardiac failure presenting with orbital pulsation. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;1(1):cvd.2012.012005. Published 2012 Apr 5. doi:10.1258/cvd.2012.012005

1. Bacorn C, Gokoffski KK, Lin LK. Clinical correlation recommended: accuracy of clinician versus radiologic interpretation of the imaging of orbital lesions. Orbit. 2021;40(2):133-137. doi:10.1080/01676830.2020.1752742

2. Shams PN, Cugati S, Wells T, Huilgol S, Selva D. Orbital varix thrombosis and review of orbital vascular anomalies in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(4):e82-e86. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000107

3. Islam N, Mireskandari K, Rose GE. Orbital varices and orbital wall defects. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(8):1092-1093.

4. Smoker WR, Gentry LR, Yee NK, Reede DL, Nerad JA. Vascular lesions of the orbit: more than meets the eye. Radiographics. 2008;28(1):185-325. doi:10.1148/rg.281075040

5. Karcioglu ZA, ed. Orbital Tumors. New York; 2005. Chap 13:133-140.

6. Chen Z, Jones H. A case of tricuspid regurgitation and congestive cardiac failure presenting with orbital pulsation. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;1(1):cvd.2012.012005. Published 2012 Apr 5. doi:10.1258/cvd.2012.012005

Evans’ Syndrome in Undiagnosed Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma: Case Report and Literature Review

Background

Evans’ syndrome is a rare entity characterized by concomitant or sequential multilineage cytopenia particularly autoimmune hemolytic anemia, ITP and very rarely autoimmune neutropenia. Although more common in young adults, it can occur in elderly usually associated with malignancies like CLL.

Case Report

A 74 years old Veteran presented with complaints of fatigue and worsening dyspnea on exertion. His physical exam was unremarkable except jaundice. His labs were significant for macrocytic anemia with Hemoglobin of 7.4g/dl compared to 11.7g/dl 6 months prior, MCV 106.9 fL, LDH 809U/L, indirect bilirubin 4.1mg/dl, absolute reticulocyte 0.16M/uL, Haptoglobin <15mg/dl and Positive DAT. Platelets were mildly decreased at 111K/ul. No lymphocytosis was noted. Initially, the hemolysis was thought to be cephalosporin- related given that the patient had taken cephalexin recently for cellulitis. As part of the workup for anemia, the patient underwent EGD and colonoscopy which was initially unrevealing. However, random biopsies from the descending colon and terminal ileum returned with a small lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with SLL/CLL. Cytogenetics showed trisomy-12 which is associated with intermediate prognosis for CLL. PET scan done subsequently revealed only a reactive marrow and an enlarged 15.8cm non-hypermetabolic spleen. This veteran having anemia, positive DAT, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly got diagnosed with Evans’s syndrome. This syndrome was the initial manifestation of his underlying CLL. We started the patient on a prednisone taper for 4 weeks to which anemia and thrombocytopenia barely responded, ultimately Rituximab 375mg/m2 x4 weekly doses was started which led to complete resolution of anemia and thrombocytopenia. We closely followed the patient and monitored CBC and hemolytic markers. The patient relapsed in two years which was subsequently managed with another course of Rituximab 375mg/m2 x4 weekly doses.

Conclusions

This case report aims to call attention to this relatively rare entity which is difficult to treat and often associated with frequent relapses. Though rare, physicians should maintain high suspicion for this syndrome in patients with multi-lineage cytopenia which are usually not even responding well to the common treatment for cytopenia. Furthermore, there is room for improvement in Evans’ syndrome management since mortality remains higher in these patients than in those with isolated autoimmuce cytopenias.

Background

Evans’ syndrome is a rare entity characterized by concomitant or sequential multilineage cytopenia particularly autoimmune hemolytic anemia, ITP and very rarely autoimmune neutropenia. Although more common in young adults, it can occur in elderly usually associated with malignancies like CLL.

Case Report

A 74 years old Veteran presented with complaints of fatigue and worsening dyspnea on exertion. His physical exam was unremarkable except jaundice. His labs were significant for macrocytic anemia with Hemoglobin of 7.4g/dl compared to 11.7g/dl 6 months prior, MCV 106.9 fL, LDH 809U/L, indirect bilirubin 4.1mg/dl, absolute reticulocyte 0.16M/uL, Haptoglobin <15mg/dl and Positive DAT. Platelets were mildly decreased at 111K/ul. No lymphocytosis was noted. Initially, the hemolysis was thought to be cephalosporin- related given that the patient had taken cephalexin recently for cellulitis. As part of the workup for anemia, the patient underwent EGD and colonoscopy which was initially unrevealing. However, random biopsies from the descending colon and terminal ileum returned with a small lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with SLL/CLL. Cytogenetics showed trisomy-12 which is associated with intermediate prognosis for CLL. PET scan done subsequently revealed only a reactive marrow and an enlarged 15.8cm non-hypermetabolic spleen. This veteran having anemia, positive DAT, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly got diagnosed with Evans’s syndrome. This syndrome was the initial manifestation of his underlying CLL. We started the patient on a prednisone taper for 4 weeks to which anemia and thrombocytopenia barely responded, ultimately Rituximab 375mg/m2 x4 weekly doses was started which led to complete resolution of anemia and thrombocytopenia. We closely followed the patient and monitored CBC and hemolytic markers. The patient relapsed in two years which was subsequently managed with another course of Rituximab 375mg/m2 x4 weekly doses.

Conclusions

This case report aims to call attention to this relatively rare entity which is difficult to treat and often associated with frequent relapses. Though rare, physicians should maintain high suspicion for this syndrome in patients with multi-lineage cytopenia which are usually not even responding well to the common treatment for cytopenia. Furthermore, there is room for improvement in Evans’ syndrome management since mortality remains higher in these patients than in those with isolated autoimmuce cytopenias.

Background

Evans’ syndrome is a rare entity characterized by concomitant or sequential multilineage cytopenia particularly autoimmune hemolytic anemia, ITP and very rarely autoimmune neutropenia. Although more common in young adults, it can occur in elderly usually associated with malignancies like CLL.

Case Report