User login

Try to normalize albumin before laparoscopic hysterectomy

LAS VEGAS – Serum albumin is an everyday health marker commonly used for risk assessment in open abdominal procedures, but it’s often not checked before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Low levels mean something is off, be it malnutrition, inflammation, chronic disease, or other problems. If it can be normalized before surgery, it should be; women probably will do better, according to investigators from the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

“In minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, we haven’t come to adopt this marker just quite yet. It could be included in the routine battery of tests” at minimal cost. “I think it’s something we should consider,” said ob.gyn. resident Suzanne Lababidi, MD.

The team was curious why serum albumin generally is not a part of routine testing for laparoscopic hysterectomy. The first step was to see if it made a difference, so they reviewed 43,289 cases in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. The women were “par for the course;” 51 years old, on average; and had a mean body mass index of 31.9 kg/m2. More than one-third were hypertensive. Mean albumin was in the normal range at 4.1 g/dL, Dr. Lababidi said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Her team did not come up with a cut-point to delay surgery – that’s the goal of further research – but they noticed on linear regression that women with lower preop albumin had higher rates of surgical site infections and intraoperative transfusions, plus higher rates of postop pneumonia; renal failure; urinary tract infection; sepsis; and deep vein thrombosis, among other issues – and even after controlling for hypertension, diabetes, and other comorbidities. The findings met statistical significance.

It’s true that patients with low albumin might have gone into the operating room sicker, but no matter; Dr. Lababidi’s point was that preop serum albumin is something to pay attention to and correct whenever possible before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Preop levels are something to consider for “counseling and optimizing patients to improve surgical outcomes,” she said.

The next step toward an albumin cut-point is to weed out confounders by further stratifying patients based on albumin levels, she said.

The work received no industry funding. Dr. Lababidi had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Lababidi S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 199.

LAS VEGAS – Serum albumin is an everyday health marker commonly used for risk assessment in open abdominal procedures, but it’s often not checked before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Low levels mean something is off, be it malnutrition, inflammation, chronic disease, or other problems. If it can be normalized before surgery, it should be; women probably will do better, according to investigators from the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

“In minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, we haven’t come to adopt this marker just quite yet. It could be included in the routine battery of tests” at minimal cost. “I think it’s something we should consider,” said ob.gyn. resident Suzanne Lababidi, MD.

The team was curious why serum albumin generally is not a part of routine testing for laparoscopic hysterectomy. The first step was to see if it made a difference, so they reviewed 43,289 cases in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. The women were “par for the course;” 51 years old, on average; and had a mean body mass index of 31.9 kg/m2. More than one-third were hypertensive. Mean albumin was in the normal range at 4.1 g/dL, Dr. Lababidi said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Her team did not come up with a cut-point to delay surgery – that’s the goal of further research – but they noticed on linear regression that women with lower preop albumin had higher rates of surgical site infections and intraoperative transfusions, plus higher rates of postop pneumonia; renal failure; urinary tract infection; sepsis; and deep vein thrombosis, among other issues – and even after controlling for hypertension, diabetes, and other comorbidities. The findings met statistical significance.

It’s true that patients with low albumin might have gone into the operating room sicker, but no matter; Dr. Lababidi’s point was that preop serum albumin is something to pay attention to and correct whenever possible before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Preop levels are something to consider for “counseling and optimizing patients to improve surgical outcomes,” she said.

The next step toward an albumin cut-point is to weed out confounders by further stratifying patients based on albumin levels, she said.

The work received no industry funding. Dr. Lababidi had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Lababidi S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 199.

LAS VEGAS – Serum albumin is an everyday health marker commonly used for risk assessment in open abdominal procedures, but it’s often not checked before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Low levels mean something is off, be it malnutrition, inflammation, chronic disease, or other problems. If it can be normalized before surgery, it should be; women probably will do better, according to investigators from the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

“In minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, we haven’t come to adopt this marker just quite yet. It could be included in the routine battery of tests” at minimal cost. “I think it’s something we should consider,” said ob.gyn. resident Suzanne Lababidi, MD.

The team was curious why serum albumin generally is not a part of routine testing for laparoscopic hysterectomy. The first step was to see if it made a difference, so they reviewed 43,289 cases in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. The women were “par for the course;” 51 years old, on average; and had a mean body mass index of 31.9 kg/m2. More than one-third were hypertensive. Mean albumin was in the normal range at 4.1 g/dL, Dr. Lababidi said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Her team did not come up with a cut-point to delay surgery – that’s the goal of further research – but they noticed on linear regression that women with lower preop albumin had higher rates of surgical site infections and intraoperative transfusions, plus higher rates of postop pneumonia; renal failure; urinary tract infection; sepsis; and deep vein thrombosis, among other issues – and even after controlling for hypertension, diabetes, and other comorbidities. The findings met statistical significance.

It’s true that patients with low albumin might have gone into the operating room sicker, but no matter; Dr. Lababidi’s point was that preop serum albumin is something to pay attention to and correct whenever possible before laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Preop levels are something to consider for “counseling and optimizing patients to improve surgical outcomes,” she said.

The next step toward an albumin cut-point is to weed out confounders by further stratifying patients based on albumin levels, she said.

The work received no industry funding. Dr. Lababidi had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Lababidi S et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 199.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

VTE risk after gynecologic surgery lower with laparoscopic procedures

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The retrospective cohort study looked at data from 37,485 patients who underwent 43,751 gynecologic surgical procedures, including hysterectomy and myomectomy, at two tertiary care academic hospitals.

Overall, 96 patients (0.2%) were diagnosed with postoperative venous thromboembolism. However patients who underwent laparoscopic or vaginal surgery had a significant 78% and 93% lower risk of venous thromboembolism, respectively, than those who underwent laparotomy, even after adjusting for potential confounders such as age, cancer, race, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, and surgical time.

The incidence of postoperative thromboembolism was significantly higher among patients undergoing gynecologic surgery for cancer (1.1%). The incidence among those undergoing surgery for benign indications was only 0.2%, and the highest incidence was among patients with cancer who underwent laparotomy (2.2%).

“This study adds to data demonstrating that venous thromboembolism is rare in gynecologic surgery, particularly when a patient undergoes a minimally invasive procedure for benign indications,” wrote Dr. Elisa M. Jorgensen of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and her coauthors.

Among the 8,273 patients who underwent a hysterectomy, there were 55 cases of venous thromboembolism – representing an 0.7% incidence. However patients who underwent laparotomy had a 1% incidence of postoperative venous thromboembolism, while those who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy had an 0.3% incidence and those who underwent vaginal hysterectomy had an 0.1% incidence.

Laparotomy was the most common mode of surgery for hysterectomy – accounting for 57% of operations – while 34% were laparoscopic and 9% were vaginal.

However, the authors noted that the use of laparoscopy increased and laparotomy declined over the 9 years of the study. In 2006, 12% of hysterectomies were laparoscopic, compared with 55% in 2015, while over that same period the percentage of laparotomies dropped from 74% to 41%, and the percentage of vaginal procedures declined from 14% to 4%.

“Because current practice guidelines do not account for mode of surgery, we find them to be insufficient for the modern gynecologic surgeon to counsel patients on their individual venous thromboembolism risk or to make ideal decisions regarding selection of thromboprophylaxis,” Dr. Jorgenson and her associates wrote.

Only 5 patients of the 2,851 who underwent myomectomy developed postoperative VTE – an overall incidence of 0.2% – and the authors said numbers were too small to analyze. Vaginal or hysteroscopic myomectomy was the most common surgical method, accounting for 62% of procedures, compared with 23% for laparotomies and 15% for laparoscopies.

More than 90% of patients who experienced postoperative thromboembolism had received some form of thromboprophylaxis before surgery, either mechanical, pharmacologic, or both. In comparison, only 55% of the group who didn’t experience thromboembolism had received thromboprophylaxis.

“The high rate of prophylaxis among patients who developed postoperative venous thromboembolism may reflect surgeons’ abilities to preoperatively identify patients at increased risk, guiding appropriate selection of thromboprophylaxis,” Dr. Jorgenson and her associates wrote.

Addressing the study’s limitations, the authors noted that they were not able to capture data on patients’ body mass index and also were unable to account for patients who might have been diagnosed and treated for postoperative VTE at other hospitals.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Jorgensen EM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132:1275-84.

The aim of this study was to determine the 3-month postoperative incidence of venous thromboembolism among patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. The study also addressed the mode of surgery to allow a comparison between laparotomy and minimally invasive approaches.

Postoperative VTE was defined as deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities, pulmonary embolism, or both that occurred within 90 days of surgery. A key component of the study was that clinically recognized VTEs that required treatment with anticoagulation, vena caval filter, or both were included.

The study evaluated 43,751 gynecological cases among 37,485 patients. As expected, 59% of the cases were classified as vaginal surgery, 24% were laparoscopic cases, and 17% of the cases were laparotomies.

Of the 8,273 hysterectomies, 57% were via an abdominal approach, 34% were laparoscopic, and 9 were vaginal cases.

Overall, 0.2% of patients were diagnosed with a VTE. As expected, the greatest incidence of VTE was in patients with cancer who underwent a laparotomy. Those with a VTE were significantly more likely to have had an inpatient stay (longer than 24 hours), a cancer diagnosis, a longer surgical time, and an American Society of Anesthesiologists score of 3 or more. They also were older (mean age 56 years vs. 44 years). Of note, 20% of the VTE group identified as black.

Among patients who had a hysterectomy, there were VTEs in 0.7%: 1% in the laparotomy group, 0.3% in the laparoscopic group, and only 0.1% in the vaginal hysterectomy group.

It is interesting to note that 91% of the patients diagnosed with a VTE did received preoperative VTE prophylaxis. The authors noted that the high rate of prophylaxis may have reflected the surgeon’s ability to identify patients who are at high risk.

The authors recognized that the current guidelines do not stratify VTE risk based on the mode of surgery. Further, they noted that low-risk patients undergoing low-risk surgery may be receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis, thus placing these patients at risk for complications related to such therapy.

This paper by Jorgensen et al. should remind us that VTE prophylaxis should be individualized. Patients may not fit nicely into boxes on our EMR; each clinical decision should be made for each patient and for each clinical scenario. The surgeon’s responsibility is to adopt the evidence-based guidelines that serve each individual patient’s unique risk/benefit profile.

David M. Jaspan, DO, is director of minimally invasive and pelvic surgery and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia. Dr. Jaspan, who was asked to comment on the Jorgenson et al. article, said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The aim of this study was to determine the 3-month postoperative incidence of venous thromboembolism among patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. The study also addressed the mode of surgery to allow a comparison between laparotomy and minimally invasive approaches.

Postoperative VTE was defined as deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities, pulmonary embolism, or both that occurred within 90 days of surgery. A key component of the study was that clinically recognized VTEs that required treatment with anticoagulation, vena caval filter, or both were included.

The study evaluated 43,751 gynecological cases among 37,485 patients. As expected, 59% of the cases were classified as vaginal surgery, 24% were laparoscopic cases, and 17% of the cases were laparotomies.

Of the 8,273 hysterectomies, 57% were via an abdominal approach, 34% were laparoscopic, and 9 were vaginal cases.

Overall, 0.2% of patients were diagnosed with a VTE. As expected, the greatest incidence of VTE was in patients with cancer who underwent a laparotomy. Those with a VTE were significantly more likely to have had an inpatient stay (longer than 24 hours), a cancer diagnosis, a longer surgical time, and an American Society of Anesthesiologists score of 3 or more. They also were older (mean age 56 years vs. 44 years). Of note, 20% of the VTE group identified as black.

Among patients who had a hysterectomy, there were VTEs in 0.7%: 1% in the laparotomy group, 0.3% in the laparoscopic group, and only 0.1% in the vaginal hysterectomy group.

It is interesting to note that 91% of the patients diagnosed with a VTE did received preoperative VTE prophylaxis. The authors noted that the high rate of prophylaxis may have reflected the surgeon’s ability to identify patients who are at high risk.

The authors recognized that the current guidelines do not stratify VTE risk based on the mode of surgery. Further, they noted that low-risk patients undergoing low-risk surgery may be receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis, thus placing these patients at risk for complications related to such therapy.

This paper by Jorgensen et al. should remind us that VTE prophylaxis should be individualized. Patients may not fit nicely into boxes on our EMR; each clinical decision should be made for each patient and for each clinical scenario. The surgeon’s responsibility is to adopt the evidence-based guidelines that serve each individual patient’s unique risk/benefit profile.

David M. Jaspan, DO, is director of minimally invasive and pelvic surgery and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia. Dr. Jaspan, who was asked to comment on the Jorgenson et al. article, said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The aim of this study was to determine the 3-month postoperative incidence of venous thromboembolism among patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. The study also addressed the mode of surgery to allow a comparison between laparotomy and minimally invasive approaches.

Postoperative VTE was defined as deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities, pulmonary embolism, or both that occurred within 90 days of surgery. A key component of the study was that clinically recognized VTEs that required treatment with anticoagulation, vena caval filter, or both were included.

The study evaluated 43,751 gynecological cases among 37,485 patients. As expected, 59% of the cases were classified as vaginal surgery, 24% were laparoscopic cases, and 17% of the cases were laparotomies.

Of the 8,273 hysterectomies, 57% were via an abdominal approach, 34% were laparoscopic, and 9 were vaginal cases.

Overall, 0.2% of patients were diagnosed with a VTE. As expected, the greatest incidence of VTE was in patients with cancer who underwent a laparotomy. Those with a VTE were significantly more likely to have had an inpatient stay (longer than 24 hours), a cancer diagnosis, a longer surgical time, and an American Society of Anesthesiologists score of 3 or more. They also were older (mean age 56 years vs. 44 years). Of note, 20% of the VTE group identified as black.

Among patients who had a hysterectomy, there were VTEs in 0.7%: 1% in the laparotomy group, 0.3% in the laparoscopic group, and only 0.1% in the vaginal hysterectomy group.

It is interesting to note that 91% of the patients diagnosed with a VTE did received preoperative VTE prophylaxis. The authors noted that the high rate of prophylaxis may have reflected the surgeon’s ability to identify patients who are at high risk.

The authors recognized that the current guidelines do not stratify VTE risk based on the mode of surgery. Further, they noted that low-risk patients undergoing low-risk surgery may be receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis, thus placing these patients at risk for complications related to such therapy.

This paper by Jorgensen et al. should remind us that VTE prophylaxis should be individualized. Patients may not fit nicely into boxes on our EMR; each clinical decision should be made for each patient and for each clinical scenario. The surgeon’s responsibility is to adopt the evidence-based guidelines that serve each individual patient’s unique risk/benefit profile.

David M. Jaspan, DO, is director of minimally invasive and pelvic surgery and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia. Dr. Jaspan, who was asked to comment on the Jorgenson et al. article, said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The retrospective cohort study looked at data from 37,485 patients who underwent 43,751 gynecologic surgical procedures, including hysterectomy and myomectomy, at two tertiary care academic hospitals.

Overall, 96 patients (0.2%) were diagnosed with postoperative venous thromboembolism. However patients who underwent laparoscopic or vaginal surgery had a significant 78% and 93% lower risk of venous thromboembolism, respectively, than those who underwent laparotomy, even after adjusting for potential confounders such as age, cancer, race, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, and surgical time.

The incidence of postoperative thromboembolism was significantly higher among patients undergoing gynecologic surgery for cancer (1.1%). The incidence among those undergoing surgery for benign indications was only 0.2%, and the highest incidence was among patients with cancer who underwent laparotomy (2.2%).

“This study adds to data demonstrating that venous thromboembolism is rare in gynecologic surgery, particularly when a patient undergoes a minimally invasive procedure for benign indications,” wrote Dr. Elisa M. Jorgensen of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and her coauthors.

Among the 8,273 patients who underwent a hysterectomy, there were 55 cases of venous thromboembolism – representing an 0.7% incidence. However patients who underwent laparotomy had a 1% incidence of postoperative venous thromboembolism, while those who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy had an 0.3% incidence and those who underwent vaginal hysterectomy had an 0.1% incidence.

Laparotomy was the most common mode of surgery for hysterectomy – accounting for 57% of operations – while 34% were laparoscopic and 9% were vaginal.

However, the authors noted that the use of laparoscopy increased and laparotomy declined over the 9 years of the study. In 2006, 12% of hysterectomies were laparoscopic, compared with 55% in 2015, while over that same period the percentage of laparotomies dropped from 74% to 41%, and the percentage of vaginal procedures declined from 14% to 4%.

“Because current practice guidelines do not account for mode of surgery, we find them to be insufficient for the modern gynecologic surgeon to counsel patients on their individual venous thromboembolism risk or to make ideal decisions regarding selection of thromboprophylaxis,” Dr. Jorgenson and her associates wrote.

Only 5 patients of the 2,851 who underwent myomectomy developed postoperative VTE – an overall incidence of 0.2% – and the authors said numbers were too small to analyze. Vaginal or hysteroscopic myomectomy was the most common surgical method, accounting for 62% of procedures, compared with 23% for laparotomies and 15% for laparoscopies.

More than 90% of patients who experienced postoperative thromboembolism had received some form of thromboprophylaxis before surgery, either mechanical, pharmacologic, or both. In comparison, only 55% of the group who didn’t experience thromboembolism had received thromboprophylaxis.

“The high rate of prophylaxis among patients who developed postoperative venous thromboembolism may reflect surgeons’ abilities to preoperatively identify patients at increased risk, guiding appropriate selection of thromboprophylaxis,” Dr. Jorgenson and her associates wrote.

Addressing the study’s limitations, the authors noted that they were not able to capture data on patients’ body mass index and also were unable to account for patients who might have been diagnosed and treated for postoperative VTE at other hospitals.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Jorgensen EM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132:1275-84.

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The retrospective cohort study looked at data from 37,485 patients who underwent 43,751 gynecologic surgical procedures, including hysterectomy and myomectomy, at two tertiary care academic hospitals.

Overall, 96 patients (0.2%) were diagnosed with postoperative venous thromboembolism. However patients who underwent laparoscopic or vaginal surgery had a significant 78% and 93% lower risk of venous thromboembolism, respectively, than those who underwent laparotomy, even after adjusting for potential confounders such as age, cancer, race, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, and surgical time.

The incidence of postoperative thromboembolism was significantly higher among patients undergoing gynecologic surgery for cancer (1.1%). The incidence among those undergoing surgery for benign indications was only 0.2%, and the highest incidence was among patients with cancer who underwent laparotomy (2.2%).

“This study adds to data demonstrating that venous thromboembolism is rare in gynecologic surgery, particularly when a patient undergoes a minimally invasive procedure for benign indications,” wrote Dr. Elisa M. Jorgensen of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and her coauthors.

Among the 8,273 patients who underwent a hysterectomy, there were 55 cases of venous thromboembolism – representing an 0.7% incidence. However patients who underwent laparotomy had a 1% incidence of postoperative venous thromboembolism, while those who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy had an 0.3% incidence and those who underwent vaginal hysterectomy had an 0.1% incidence.

Laparotomy was the most common mode of surgery for hysterectomy – accounting for 57% of operations – while 34% were laparoscopic and 9% were vaginal.

However, the authors noted that the use of laparoscopy increased and laparotomy declined over the 9 years of the study. In 2006, 12% of hysterectomies were laparoscopic, compared with 55% in 2015, while over that same period the percentage of laparotomies dropped from 74% to 41%, and the percentage of vaginal procedures declined from 14% to 4%.

“Because current practice guidelines do not account for mode of surgery, we find them to be insufficient for the modern gynecologic surgeon to counsel patients on their individual venous thromboembolism risk or to make ideal decisions regarding selection of thromboprophylaxis,” Dr. Jorgenson and her associates wrote.

Only 5 patients of the 2,851 who underwent myomectomy developed postoperative VTE – an overall incidence of 0.2% – and the authors said numbers were too small to analyze. Vaginal or hysteroscopic myomectomy was the most common surgical method, accounting for 62% of procedures, compared with 23% for laparotomies and 15% for laparoscopies.

More than 90% of patients who experienced postoperative thromboembolism had received some form of thromboprophylaxis before surgery, either mechanical, pharmacologic, or both. In comparison, only 55% of the group who didn’t experience thromboembolism had received thromboprophylaxis.

“The high rate of prophylaxis among patients who developed postoperative venous thromboembolism may reflect surgeons’ abilities to preoperatively identify patients at increased risk, guiding appropriate selection of thromboprophylaxis,” Dr. Jorgenson and her associates wrote.

Addressing the study’s limitations, the authors noted that they were not able to capture data on patients’ body mass index and also were unable to account for patients who might have been diagnosed and treated for postoperative VTE at other hospitals.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Jorgensen EM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132:1275-84.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Laparoscopic gynecologic surgery is associated with a lower risk of postoperative VTE than laparotomy.

Major finding: Laparoscopic hysterectomy was associated with a 78% lower incidence of postoperative VTE than laparotomy.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 37,485 patients who underwent 43,751 gynecologic surgical procedures

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Jorgensen EM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132:1275-84.

Laparoscopic suturing is an option

Laparoscopic suturing is an option

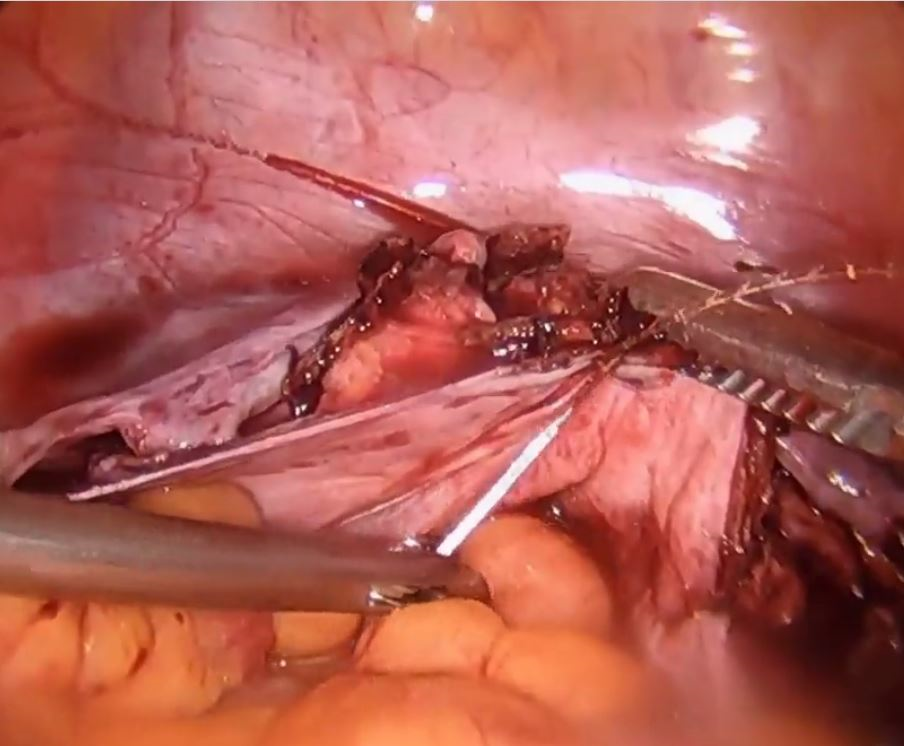

Dr. Lum presented a nicely produced video demonstrating various strategies aimed at facilitating total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus. Her patient’s evaluation included magnetic resonance imaging. In the video, she demonstrates a variety of interventions, including the use of a preoperative gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GNRH) agonist and immediate perioperative radial artery–uterine artery embolization. Intraoperative techniques include use of ureteral stents and securing the uterine arteries at their origins.

Clearly, TLH of a huge uterus is a technical challenge. However, I’d like to suggest that a relatively basic and important skill would greatly assist in such procedures and likely obviate the need for a GNRH agonist and/or uterine artery embolization. The vessel-sealing devices shown in the video are generally not capable of sealing such large vessels adequately, and this is what leads to the massive hemorrhaging that often occurs.

Laparoscopic suturing with extracorporeal knot tying can be used effectively to control the extremely large vessels associated with a huge uterus. The judicious placement of sutures can completely control such vessels and prevent bleeding from both proximal and distal ends when 2 sutures are placed and the vessels are transected between the stitches. Many laparoscopic surgeons have come to rely on bipolar energy or ultrasonic devices to coagulate vessels. But when dealing with huge vessels, a return to basics using laparoscopic suturing will greatly benefit the patient and the surgeon by reducing blood loss and operative time.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Dr. Lum responds

I thank Dr. Zisow for his thoughtful comments. I agree that laparoscopic suturing is an essential skill that can be utilized to suture ligate vessels. If we consider the basics of an open hysterectomy, the uterine artery is clamped first, then suture ligated. When approaching a very large vessel during TLH, I would be concerned that a simple suture around a large vessel might tear through and cause more bleeding. To mitigate this risk, the vessel can be clamped with a grasper first, similar to the approach in an open hysterectomy. However, once a vessel is compressed, a sealing device can usually work just as well as a suture. It becomes a matter of preference and cost.

During hysterectomy of a very large uterus, a big challenge is managing bleeding of the uterus itself during manipulation from above. Bleeding from the vascular sinuses of the myometrium can be brisk and obscure visualization, potentially leading to laparotomy conversion. A common misconception is that uterine artery embolization is equivalent to suturing the uterine arteries. In actuality, the goal of a uterine artery embolization is to embolize the distal branches of the uterine arteries, which can help with any potential bleeding from the uterus itself during hysterectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Laparoscopic suturing is an option

Dr. Lum presented a nicely produced video demonstrating various strategies aimed at facilitating total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus. Her patient’s evaluation included magnetic resonance imaging. In the video, she demonstrates a variety of interventions, including the use of a preoperative gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GNRH) agonist and immediate perioperative radial artery–uterine artery embolization. Intraoperative techniques include use of ureteral stents and securing the uterine arteries at their origins.

Clearly, TLH of a huge uterus is a technical challenge. However, I’d like to suggest that a relatively basic and important skill would greatly assist in such procedures and likely obviate the need for a GNRH agonist and/or uterine artery embolization. The vessel-sealing devices shown in the video are generally not capable of sealing such large vessels adequately, and this is what leads to the massive hemorrhaging that often occurs.

Laparoscopic suturing with extracorporeal knot tying can be used effectively to control the extremely large vessels associated with a huge uterus. The judicious placement of sutures can completely control such vessels and prevent bleeding from both proximal and distal ends when 2 sutures are placed and the vessels are transected between the stitches. Many laparoscopic surgeons have come to rely on bipolar energy or ultrasonic devices to coagulate vessels. But when dealing with huge vessels, a return to basics using laparoscopic suturing will greatly benefit the patient and the surgeon by reducing blood loss and operative time.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Dr. Lum responds

I thank Dr. Zisow for his thoughtful comments. I agree that laparoscopic suturing is an essential skill that can be utilized to suture ligate vessels. If we consider the basics of an open hysterectomy, the uterine artery is clamped first, then suture ligated. When approaching a very large vessel during TLH, I would be concerned that a simple suture around a large vessel might tear through and cause more bleeding. To mitigate this risk, the vessel can be clamped with a grasper first, similar to the approach in an open hysterectomy. However, once a vessel is compressed, a sealing device can usually work just as well as a suture. It becomes a matter of preference and cost.

During hysterectomy of a very large uterus, a big challenge is managing bleeding of the uterus itself during manipulation from above. Bleeding from the vascular sinuses of the myometrium can be brisk and obscure visualization, potentially leading to laparotomy conversion. A common misconception is that uterine artery embolization is equivalent to suturing the uterine arteries. In actuality, the goal of a uterine artery embolization is to embolize the distal branches of the uterine arteries, which can help with any potential bleeding from the uterus itself during hysterectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Laparoscopic suturing is an option

Dr. Lum presented a nicely produced video demonstrating various strategies aimed at facilitating total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus. Her patient’s evaluation included magnetic resonance imaging. In the video, she demonstrates a variety of interventions, including the use of a preoperative gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GNRH) agonist and immediate perioperative radial artery–uterine artery embolization. Intraoperative techniques include use of ureteral stents and securing the uterine arteries at their origins.

Clearly, TLH of a huge uterus is a technical challenge. However, I’d like to suggest that a relatively basic and important skill would greatly assist in such procedures and likely obviate the need for a GNRH agonist and/or uterine artery embolization. The vessel-sealing devices shown in the video are generally not capable of sealing such large vessels adequately, and this is what leads to the massive hemorrhaging that often occurs.

Laparoscopic suturing with extracorporeal knot tying can be used effectively to control the extremely large vessels associated with a huge uterus. The judicious placement of sutures can completely control such vessels and prevent bleeding from both proximal and distal ends when 2 sutures are placed and the vessels are transected between the stitches. Many laparoscopic surgeons have come to rely on bipolar energy or ultrasonic devices to coagulate vessels. But when dealing with huge vessels, a return to basics using laparoscopic suturing will greatly benefit the patient and the surgeon by reducing blood loss and operative time.

David L. Zisow, MD

Baltimore, Maryland

Dr. Lum responds

I thank Dr. Zisow for his thoughtful comments. I agree that laparoscopic suturing is an essential skill that can be utilized to suture ligate vessels. If we consider the basics of an open hysterectomy, the uterine artery is clamped first, then suture ligated. When approaching a very large vessel during TLH, I would be concerned that a simple suture around a large vessel might tear through and cause more bleeding. To mitigate this risk, the vessel can be clamped with a grasper first, similar to the approach in an open hysterectomy. However, once a vessel is compressed, a sealing device can usually work just as well as a suture. It becomes a matter of preference and cost.

During hysterectomy of a very large uterus, a big challenge is managing bleeding of the uterus itself during manipulation from above. Bleeding from the vascular sinuses of the myometrium can be brisk and obscure visualization, potentially leading to laparotomy conversion. A common misconception is that uterine artery embolization is equivalent to suturing the uterine arteries. In actuality, the goal of a uterine artery embolization is to embolize the distal branches of the uterine arteries, which can help with any potential bleeding from the uterus itself during hysterectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Size can matter: Laparoscopic hysterectomy for the very large uterus

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

This video is brought to you by

Basic technique of vaginal hysterectomy

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

This video is brought to you by

What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Due to an increase in minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy, including vaginal and laparoscopic approaches, gynecologic surgeons may need to turn to simulation training to augment practice and hone skills. Simulation is useful for all surgeons, especially for low-volume surgeons, as a warm-up to sharpen technical skills prior to starting the day’s cases. Additionally, educators are uniquely poised to use simulation to teach residents and to evaluate their procedural competency.

In this article, we provide an overview of the 3 approaches to hysterectomy—vaginal, laparoscopic, abdominal—through medical modeling and simulation techniques. We focus on practical issues, including current resources available online, cost, setup time, fidelity, and limitations of some commonly available vaginal, laparoscopic, and open hysterectomy models.

Simulation directly influences patient safety. Thus, the value of simulation cannot be overstated, as it can increase the quality of health care by improving patient outcomes and lowering overall costs. In 2008, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) founded the Simulations Working Group to establish simulation as a pillar in education for women’s health through collaboration, advocacy, research, and the development and implementation of multidisciplinary simulations-based educational resources and opportunities.

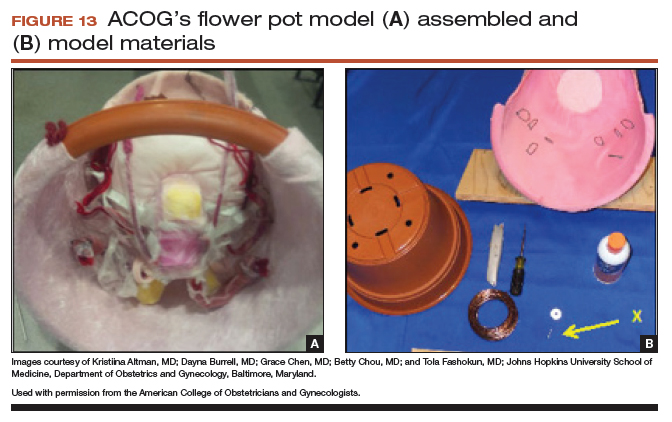

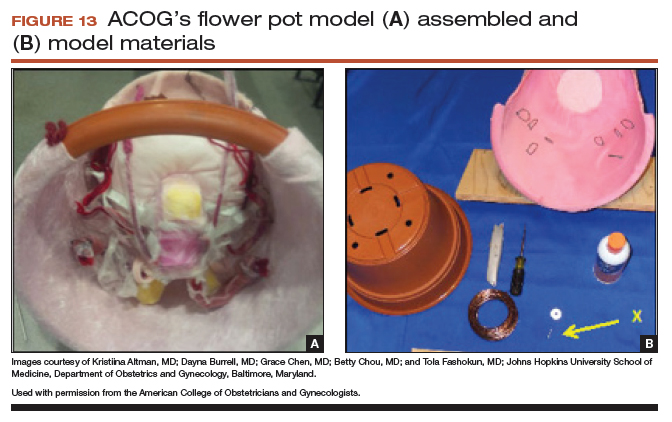

Refer to the ACOG Simulations Working Group Toolkit online to see the objectives, simulation, and videos related to each module. Under the “Hysterectomy” section, you will find how to construct the “flower pot” model for abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy, as well as the AAGL vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy webinars. All content is reaffirmed frequently to keep it up to date. You can access the toolkit, with your ACOG login and passcode, at https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Simulations-Consortium/Simulations-Consortium-Tool-Kit.

For a comprehensive gynecology curriculum to include vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal approaches to hysterectomy, refer to ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology page at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/. This page lists the standardized surgical skills curriculum for use in training residents in obstetrics and gynecology by procedure. It includes:

- the objective, description, and assessment of the module

- a description of the simulation

- a description of the surgical procedure

- a quiz that must be passed to proceed to evaluation by a faculty member

- an evaluation form to be downloaded and printed by the learner.

Takeaway. Value of Simulation = Quality (Improved Patient Outcomes) ÷ Direct and Indirect Costs.

Simulation models for training in vaginal hysterectomy

According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the minimum number of vaginal hysterectomies is 15; this number represents the minimum accepted exposure, however, and does not imply competency. Exposure to vaginal hysterectomy in residency training has significantly declined over the years, with a mean of only 19 vaginal hysterectomies performed by the time of graduation in 2014.1

A wide range of simulation models are available that you either can construct or purchase, based on your budget. We discuss 3 such models below.

The Miya model

The Miya Model Pelvic Surgery Training Model (Miyazaki Enterprises) consists of a bony pelvic frame and multiple replaceable and realistic anatomic structures, including the uterus, cervix, and adnexa (1 structure), vagina, bladder, and a few selected muscles and ligaments for pelvic floor disorders (FIGURE 1). The model incorporates features to simulate actual surgical experiences, such as realistic cutting and puncturing tensions, palpable surgical landmarks, a pressurized vascular system with bleeding for inadequate technique, and an inflatable bladder that can leak water if damaged.

Mounted on a rotating stand with the top of the pelvis open, the Miya model is designed to provide access and visibility, enabling supervising physicians the ability to give immediate guidance and feedback. The interchangeable parts allow the learner to be challenged at the appropriate skill level with the use of a large uterus versus a smaller uterus.

New in 2018 is an “intern” uterus and vagina that have no vascular supply and a single-layer vagina; this model is one-third of the cost of the larger, high-fidelity uterus (which has a vascular supply and additional tissue layers).

The Miya model reusable bony pelvic frame has a one-time cost of a few thousand dollars. Advantages include its high fidelity, low technology, light weight, portability, and quick setup. To view a video of the Miya model, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=49&v=A2RjOgVRclo. To see a simulated vaginal hysterectomy, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=13&v=dwiQz4DTyy8.

The gynecologic surgeon and inventor, Dr. Douglas Miyazaki, has improved the vesicouterine peritoneal fold (usually the most challenging for the surgeon) to have a more realistic, slippery feel when palpated.

This model’s weaknesses are its cost (relative to low-fidelity models) and the inability to use energy devices.

Takeaway. The Miya model is a high-fidelity, portable vaginal hysterectomy model with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts

The Gynesim model

The Gynesim Vaginal Hysterectomy Model, developed by Dr. Malcolm “Kip” Mackenzie (Gynesim), is a high-fidelity surgical simulation model constructed from animal tissue to provide realistic training in pelvic surgery (FIGURE 2).

These “real tissue models” are hand-constructed from animal tissue harvested from US Department of Agriculture inspected meat processing centers. The models mimic normal and abnormal abdominal and pelvic anatomy, providing realistic feel (haptics) and response to all surgical energy modalities. The “cassette” tissues are placed within a vaginal approach platform, which is portable.

Each model (including a 120- to 240-g uterus, bladder, ureter, uterine artery, cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, and rectum) supports critical gaps in surgical techniques such as peritoneal entry and cuff closure. Gynesim staff set up the entire laboratory, including the simulation models, instruments, and/or cameras; however, surgical energy systems are secured from the host institution.

The advantages of this model are its excellent tissue haptics and the minimal preparation time required from the busy gynecologic teaching faculty, as the company performs the setup and breakdown. Disadvantages include the model’s cost (relative to low-fidelity models), that it does not bleed, its one-time use, and the need for technical assistance from the company for setup.

This model can be used for laparoscopic and open hysterectomy approaches, as well as for vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit the Gynesim website at https://www.gynesim.com/vaginal-hysterectomy/.

Takeaway. The high-fidelity Gynesim model can be used to practice vaginal, laparoscopic, or open hysterectomy approaches. It offers excellent tissue haptics, one-time use “cassettes” made from animal tissue, and compatibility with energy devices.

The milk jug model

The milk jug and fabric uterus model, developed by Dr. Dee Fenner, is a low-cost simulation model and an alternative to the flower pot model (described later in this article). The bony pelvis is simulated by a 1-gallon milk carton that is taped to a foam ring. Other materials used to make the uterus are fabric, stuffing, and a needle and thread (or a sewing machine). Each model costs approximately $5 and takes approximately 15 minutes to create. For instructions on how to construct this model, see the Society for Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) award-winning video from 2012 at https://vimeo.com/123804677.

The advantages of this model are that it is inexpensive and is a good tool with which novice gynecologic surgeons can learn the basic steps of the procedure. The disadvantages are that it does not bleed, is not compatible with energy devices, and must be constructed by hand (adding considerable time) or with a sewing machine.

Takeaway. The milk jug model is a low-cost, low-fidelity model for the novice surgeon that can be quickly constructed with the use of a sewing machine.

Read about simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy

While overall hysterectomy numbers have remained relatively stable during the last 10 years, the proportion of laparoscopic hysterectomy procedures is increasing in residency training.1 Many toolkits and models are available for practicing skills, from low-fidelity models on which to rehearse laparoscopic techniques (suturing, instrument handling) to high-fidelity models that provide augmented reality views of the abdominal cavity as well as the operating room itself. We offer a sampling of 4 such models below.

The FLS trainer system

The Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) Trainer Box (Limbs & Things Ltd) provides hands-on manual skills practice and training for laparoscopic surgery (FIGURE 3). The FLS trainer box uses 5 skills to challenge a surgeon’s dexterity and psychomotor skills. The set includes the trainer box with a camera and light source as well as the equipment needed to perform the 5 FLS tasks (peg transfer, pattern cutting, ligating loop, and intracorporeal and extracorporeal knot tying). The kit does not include laparoscopic instruments or a monitor.

The FLS trainer box with camera costs $1,164. The advantages are that it is portable and can be used to warm-up prior to surgery or for practice to improve technical skills. It is a great tool for junior residents who are learning the basics of laparoscopic surgery. This trainer’s disadvantages are that it is a low-fidelity unit that is procedure agnostic. For more information, visit the Limbs & Things website at https://www.fls-products.com.

Notably, ObGyn residents who graduate after May 31, 2020, will be required to successfully complete the FLS program as a prerequisite for specialty board certification.2 The FLS program is endorsed by the American College of Surgeons and is run through the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. The FLS test is proctored and must be taken at a testing center.

Takeaway. The FLS trainer box is readily available, portable, relatively inexpensive, low-tech, and has valid benchmarks for proficiency. The FLS test will be required for ObGyn residents by 2020.

The SimPraxis software trainer

The SimPraxis Laparoscopic Hysterectomy Trainer (Red Llama, Inc) is an interactive simulation software platform that is available in DVD or USB format (FIGURE 4). The software is designed to review anatomy, surgical instrumentation, and specific steps of the procedure. It provides formative assessments and offers summative feedback for users.

The SimPraxis training software would make a useful tool to familiarize medical students and interns with the basics of the procedure before advancing to other simulation trainers. The software costs $100. For more information, visit https://www.3-dmed.com/product/simpraxis%C3%82%C2%AE-laparoscopic-hysterectomy-trainer.

Takeaway. The SimPraxis software is ideal for novice learners and can be used on a home or office computer.

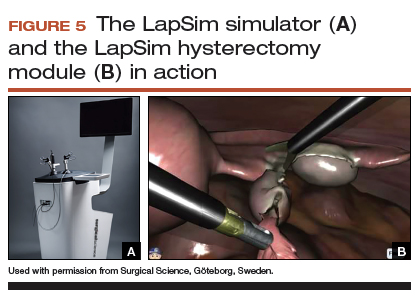

The LapSim virtual reality trainer

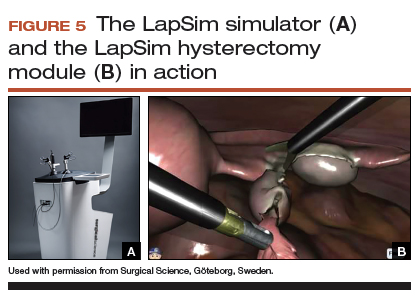

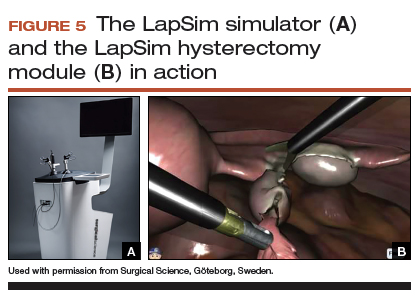

The LapSim Haptic System (Surgical Science) is a virtual reality skills trainer. The hysterectomy module includes right and left uterine artery dissection, vaginal cuff opening, and cuff closure (FIGURE 5). One advantage of this simulator is its haptic feedback system, which enhances the fidelity of the training.

The LapSim simulator includes a training module for students and early learners and modules to improve camera handling. The virtual reality base system costs $70,720, and the hysterectomy software module is an additional $15,600.

For more information, visit the company’s website at https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/. For an informational video, go to https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/video/.

Takeaway. The LapSim is an expensive, high-fidelity, virtual reality simulator with enhanced haptics and software for practicing laparoscopic hysterectomy.

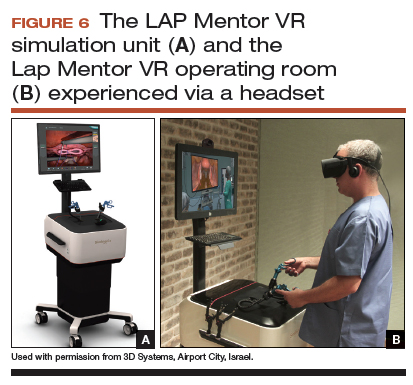

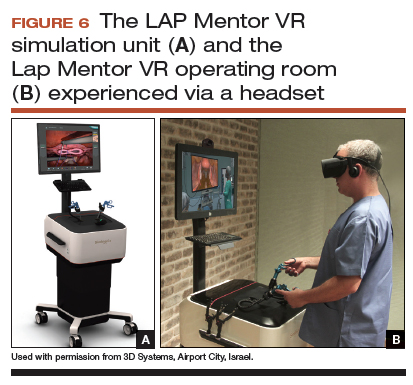

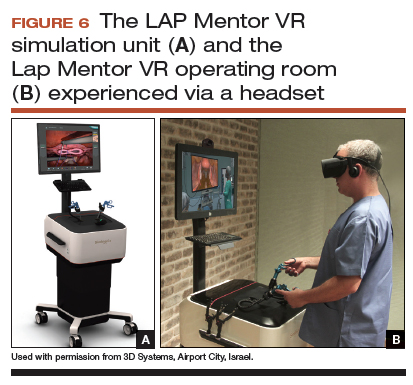

The LAP Mentor virtual reality simulator

The LAP Mentor VR (3D Systems) is another virtual reality simulator that has modules for laparoscopic hysterectomy and cuff closure (FIGURE 6). The trainee uses a virtual reality headset and becomes fully immersed in the operating room environment with audio and visual cues that mimic a real surgical experience.

The hysterectomy module allows the user to manipulate the uterus, identify the ureters, divide the superior pedicles, mobilize the bladder, expose and divide the uterine artery, and perform the colpotomy. The cuff closure module allows the user to suture the vaginal cuff using barbed suture. The module also can expose the learner to complications, such as bladder, ureteral, colon, or vascular injury.

The LAP Mentor VR base system costs $84,000 and the modules cost about $15,000. For additional information, visit the company’s website at http://simbionix.com/simulators/lap-mentor/lap-mentor-vr-or/.

Takeaway. The LAP Mentor is an expensive, high-fidelity simulation platform with a virtual reality headset that simulates a laparoscopic hysterectomy (with complications) in the operating room.

Read about simulations models for robot-assisted lap hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy.

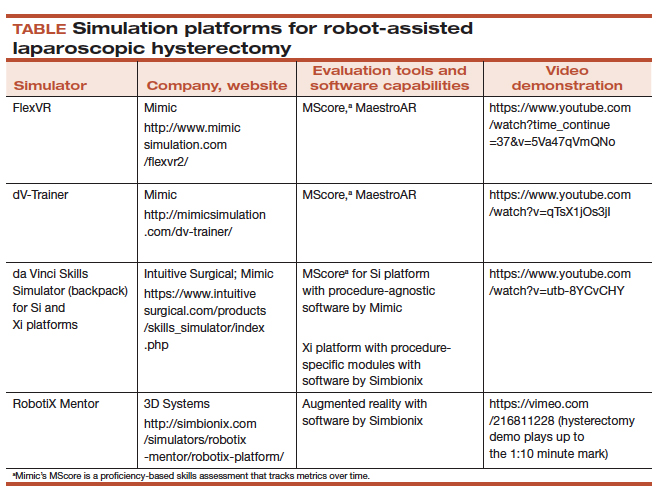

Simulation models for training in robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy

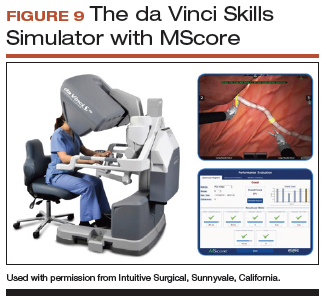

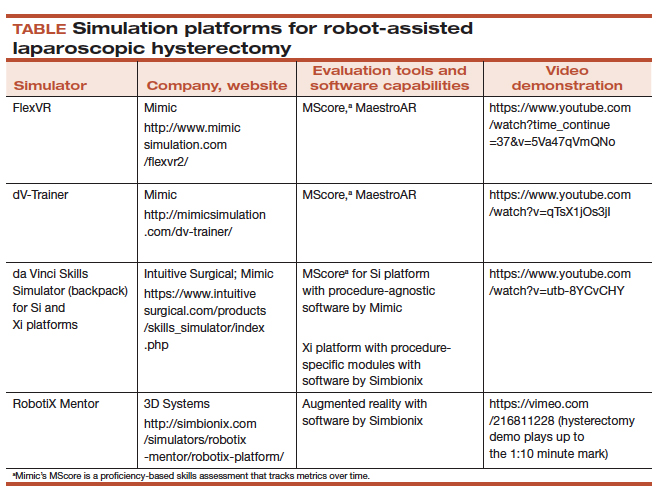

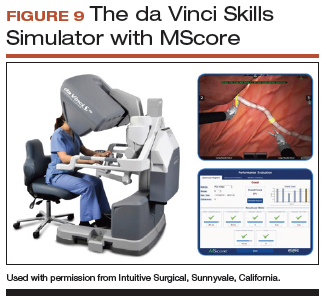

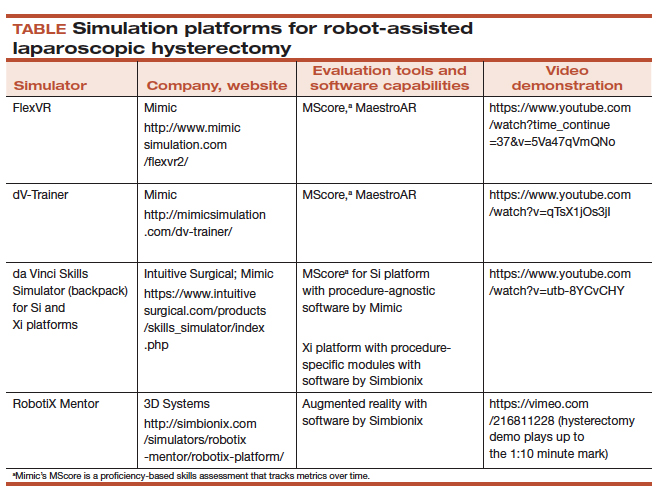

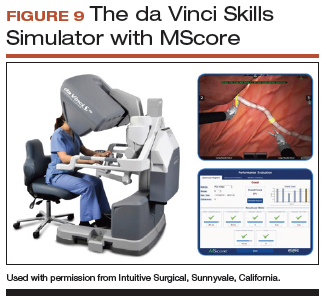

All robot-assisted simulation platforms have highly realistic graphics, and they are expensive (TABLE). However, the da Vinci Skills Simulator (backpack) platform is included with the da Vinci Si and Xi Systems. Note, though, that it can be challenging to access the surgeon console and backpack at institutions with high volumes of robot-assisted surgery.

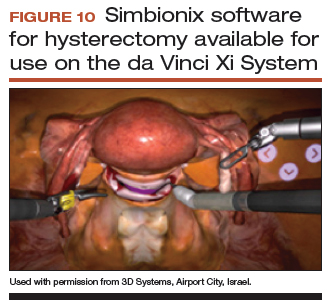

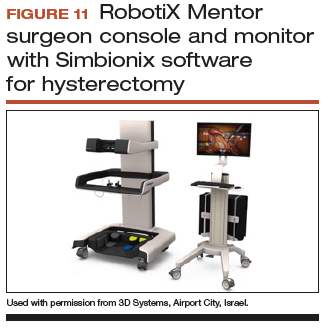

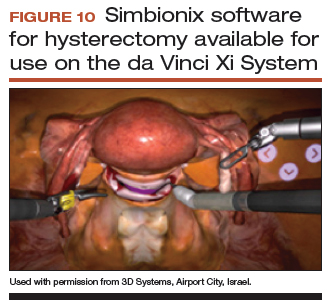

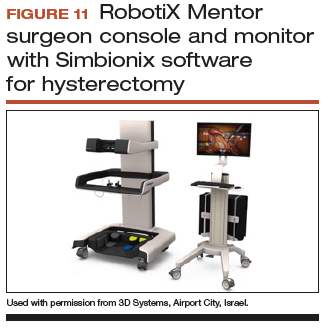

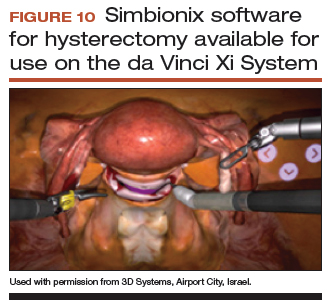

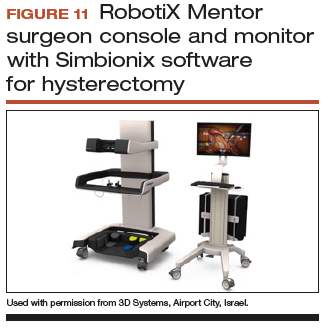

Other options that generally reside outside of the operating room include Mimic’s FlexVR and dV-Trainer and the Robotix Mentor by 3D Systems (FIGURES 7–11). Mimic’s new technology, called MaestroAR (augmented reality), allows trainees to manipulate virtual robotic instruments to interact with anatomic regions within augmented 3D surgical video footage, with narration and instruction by Dr. Arnold Advincula.

Newer software by Simbionix allows augmented reality to assist the simulation of robot-assisted hysterectomy with the da Vinci Xi backpack and RobotiX platforms.

Models for training in abdominal hysterectomy

In the last 10 years, there has been a 30% decrease in the number of abdominal hysterectomies performed by residents.1 Because of this decline in operating room experience, simulation training can be an important tool to bolster residency experience.

There are not many simulation models available for teaching abdominal hysterectomy, but here we discuss 2 that we utilize in our residency program.

Adaptable task trainer

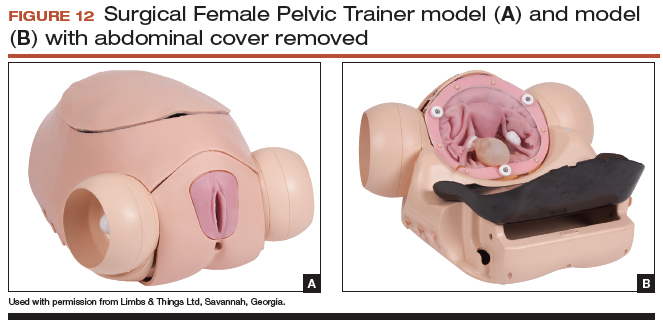

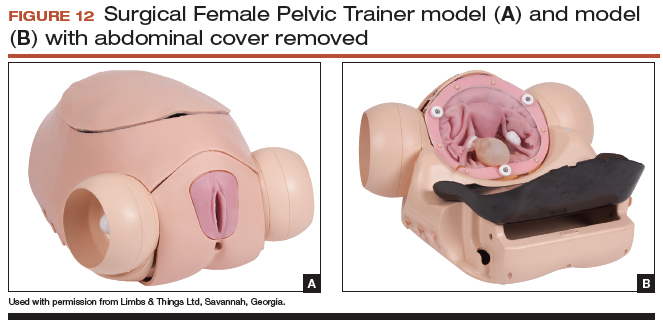

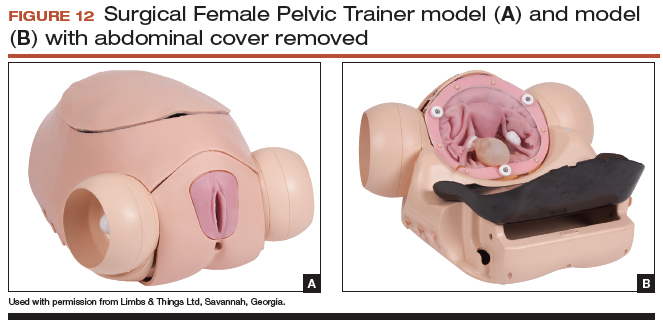

The Surgical Female Pelvic Trainer (SFPT) (Limbs & Things Ltd), a pelvic task trainer primarily used for simulation of laparoscopic hysterectomy, can be adapted for abdominal hysterectomy by removing the abdominal cover (FIGURE 12). This trainer can be used with simulated blood to increase the realism of training. The SFPT trainer costs $2,190. For more information, go to https://www.limbsandthings.com/us/our-products/details/surgical-female-pelvic-trainer-sfpt-mk-2.

Takeaway. The SFPT is a medium-fidelity task trainer with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts.

ACOG’s do-it-yourself flower pot model

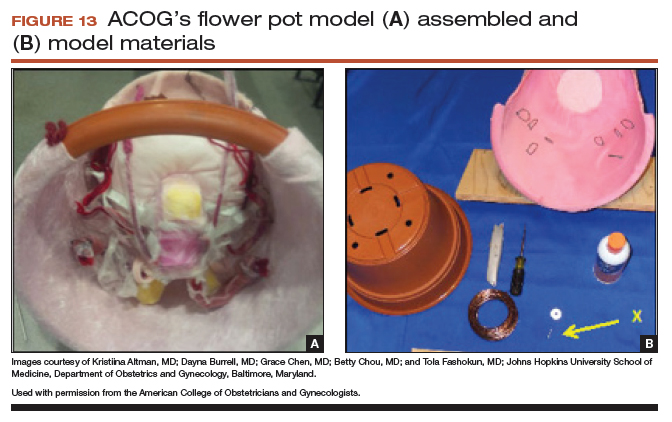

The flower pot model (developed by the ACOG Simulation Working Group, Washington, DC) is a comprehensive educational package that includes learning objectives, simulation construction instructions, content review of the abdominal hysterectomy, quiz, and evaluation form.3 ACOG has endorsed this low-cost model for residency education. Each model costs approximately $20, and the base (flower pot) is reusable (FIGURE 13).Construction time for each model is 30 to 60 minutes, and learners can participate in the construction. This can aid in anatomy review and familiarization with the model prior to training in the surgical procedure.

The learning objectives, content review, quiz, and evaluation form can be used for the flower pot model or for high-fidelity models.

The advantages of this model are the low cost and that it provides enough fidelity to teach each of the critical steps of the procedure. The disadvantages include that it is a lower-fidelity model, requires a considerable amount of time for construction, does not bleed, and is not compatible with energy devices. This model also can be used for training in laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum website at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/.

Takeaway. ACOG’s flower pot model for hysterectomy training is a comprehensive, low-cost, low-fidelity simulation model that requires significant setup time.

Simulation’s offerings

Simulation training is the present and future of medicine that bridges the gap between textbook learning and technical proficiency. Although in this article we describe only a handful of the simulation resources available, we hope that you will incorporate such tools into your practice for continuing education and skill development. Utilize peer-reviewed resources, such as the ACOG curriculum module and evaluation tools for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal hysterectomy, which can be used with any simulation model to provide a comprehensive and complimentary learning experience.

The future of health care depends on the commitment and ingenuity of educators who embrace medical simulation’s purpose: improved patient safety, effectiveness, and efficiency. Join the movement!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Washburn EE, Cohen SL, Manoucheri E, Zurawin RK, Einarsson JI. Trends in reported resident surgical experience in hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(6):1067–1070.

- American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ABOG announces new eligibility requirement for board certification. https://www.abog.org/new/ABOG_FLS.aspx. Published January 22, 2018. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Altman K, Burrell D, Chen G, Chou B, Fashokun T. Surgical curriculum in obstetrics and gynecology: vaginal hysterectomy simulation. https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/scog008/Simulation.cfm. Published December 2014. Accessed April 10, 2018.

Due to an increase in minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy, including vaginal and laparoscopic approaches, gynecologic surgeons may need to turn to simulation training to augment practice and hone skills. Simulation is useful for all surgeons, especially for low-volume surgeons, as a warm-up to sharpen technical skills prior to starting the day’s cases. Additionally, educators are uniquely poised to use simulation to teach residents and to evaluate their procedural competency.

In this article, we provide an overview of the 3 approaches to hysterectomy—vaginal, laparoscopic, abdominal—through medical modeling and simulation techniques. We focus on practical issues, including current resources available online, cost, setup time, fidelity, and limitations of some commonly available vaginal, laparoscopic, and open hysterectomy models.

Simulation directly influences patient safety. Thus, the value of simulation cannot be overstated, as it can increase the quality of health care by improving patient outcomes and lowering overall costs. In 2008, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) founded the Simulations Working Group to establish simulation as a pillar in education for women’s health through collaboration, advocacy, research, and the development and implementation of multidisciplinary simulations-based educational resources and opportunities.

Refer to the ACOG Simulations Working Group Toolkit online to see the objectives, simulation, and videos related to each module. Under the “Hysterectomy” section, you will find how to construct the “flower pot” model for abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy, as well as the AAGL vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy webinars. All content is reaffirmed frequently to keep it up to date. You can access the toolkit, with your ACOG login and passcode, at https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Simulations-Consortium/Simulations-Consortium-Tool-Kit.

For a comprehensive gynecology curriculum to include vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal approaches to hysterectomy, refer to ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology page at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/. This page lists the standardized surgical skills curriculum for use in training residents in obstetrics and gynecology by procedure. It includes:

- the objective, description, and assessment of the module

- a description of the simulation

- a description of the surgical procedure

- a quiz that must be passed to proceed to evaluation by a faculty member

- an evaluation form to be downloaded and printed by the learner.

Takeaway. Value of Simulation = Quality (Improved Patient Outcomes) ÷ Direct and Indirect Costs.

Simulation models for training in vaginal hysterectomy

According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the minimum number of vaginal hysterectomies is 15; this number represents the minimum accepted exposure, however, and does not imply competency. Exposure to vaginal hysterectomy in residency training has significantly declined over the years, with a mean of only 19 vaginal hysterectomies performed by the time of graduation in 2014.1

A wide range of simulation models are available that you either can construct or purchase, based on your budget. We discuss 3 such models below.

The Miya model

The Miya Model Pelvic Surgery Training Model (Miyazaki Enterprises) consists of a bony pelvic frame and multiple replaceable and realistic anatomic structures, including the uterus, cervix, and adnexa (1 structure), vagina, bladder, and a few selected muscles and ligaments for pelvic floor disorders (FIGURE 1). The model incorporates features to simulate actual surgical experiences, such as realistic cutting and puncturing tensions, palpable surgical landmarks, a pressurized vascular system with bleeding for inadequate technique, and an inflatable bladder that can leak water if damaged.

Mounted on a rotating stand with the top of the pelvis open, the Miya model is designed to provide access and visibility, enabling supervising physicians the ability to give immediate guidance and feedback. The interchangeable parts allow the learner to be challenged at the appropriate skill level with the use of a large uterus versus a smaller uterus.

New in 2018 is an “intern” uterus and vagina that have no vascular supply and a single-layer vagina; this model is one-third of the cost of the larger, high-fidelity uterus (which has a vascular supply and additional tissue layers).

The Miya model reusable bony pelvic frame has a one-time cost of a few thousand dollars. Advantages include its high fidelity, low technology, light weight, portability, and quick setup. To view a video of the Miya model, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=49&v=A2RjOgVRclo. To see a simulated vaginal hysterectomy, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=13&v=dwiQz4DTyy8.

The gynecologic surgeon and inventor, Dr. Douglas Miyazaki, has improved the vesicouterine peritoneal fold (usually the most challenging for the surgeon) to have a more realistic, slippery feel when palpated.

This model’s weaknesses are its cost (relative to low-fidelity models) and the inability to use energy devices.

Takeaway. The Miya model is a high-fidelity, portable vaginal hysterectomy model with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts

The Gynesim model

The Gynesim Vaginal Hysterectomy Model, developed by Dr. Malcolm “Kip” Mackenzie (Gynesim), is a high-fidelity surgical simulation model constructed from animal tissue to provide realistic training in pelvic surgery (FIGURE 2).

These “real tissue models” are hand-constructed from animal tissue harvested from US Department of Agriculture inspected meat processing centers. The models mimic normal and abnormal abdominal and pelvic anatomy, providing realistic feel (haptics) and response to all surgical energy modalities. The “cassette” tissues are placed within a vaginal approach platform, which is portable.

Each model (including a 120- to 240-g uterus, bladder, ureter, uterine artery, cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, and rectum) supports critical gaps in surgical techniques such as peritoneal entry and cuff closure. Gynesim staff set up the entire laboratory, including the simulation models, instruments, and/or cameras; however, surgical energy systems are secured from the host institution.

The advantages of this model are its excellent tissue haptics and the minimal preparation time required from the busy gynecologic teaching faculty, as the company performs the setup and breakdown. Disadvantages include the model’s cost (relative to low-fidelity models), that it does not bleed, its one-time use, and the need for technical assistance from the company for setup.

This model can be used for laparoscopic and open hysterectomy approaches, as well as for vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit the Gynesim website at https://www.gynesim.com/vaginal-hysterectomy/.

Takeaway. The high-fidelity Gynesim model can be used to practice vaginal, laparoscopic, or open hysterectomy approaches. It offers excellent tissue haptics, one-time use “cassettes” made from animal tissue, and compatibility with energy devices.

The milk jug model

The milk jug and fabric uterus model, developed by Dr. Dee Fenner, is a low-cost simulation model and an alternative to the flower pot model (described later in this article). The bony pelvis is simulated by a 1-gallon milk carton that is taped to a foam ring. Other materials used to make the uterus are fabric, stuffing, and a needle and thread (or a sewing machine). Each model costs approximately $5 and takes approximately 15 minutes to create. For instructions on how to construct this model, see the Society for Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) award-winning video from 2012 at https://vimeo.com/123804677.

The advantages of this model are that it is inexpensive and is a good tool with which novice gynecologic surgeons can learn the basic steps of the procedure. The disadvantages are that it does not bleed, is not compatible with energy devices, and must be constructed by hand (adding considerable time) or with a sewing machine.

Takeaway. The milk jug model is a low-cost, low-fidelity model for the novice surgeon that can be quickly constructed with the use of a sewing machine.

Read about simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Simulation models for training in laparoscopic hysterectomy

While overall hysterectomy numbers have remained relatively stable during the last 10 years, the proportion of laparoscopic hysterectomy procedures is increasing in residency training.1 Many toolkits and models are available for practicing skills, from low-fidelity models on which to rehearse laparoscopic techniques (suturing, instrument handling) to high-fidelity models that provide augmented reality views of the abdominal cavity as well as the operating room itself. We offer a sampling of 4 such models below.

The FLS trainer system

The Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) Trainer Box (Limbs & Things Ltd) provides hands-on manual skills practice and training for laparoscopic surgery (FIGURE 3). The FLS trainer box uses 5 skills to challenge a surgeon’s dexterity and psychomotor skills. The set includes the trainer box with a camera and light source as well as the equipment needed to perform the 5 FLS tasks (peg transfer, pattern cutting, ligating loop, and intracorporeal and extracorporeal knot tying). The kit does not include laparoscopic instruments or a monitor.

The FLS trainer box with camera costs $1,164. The advantages are that it is portable and can be used to warm-up prior to surgery or for practice to improve technical skills. It is a great tool for junior residents who are learning the basics of laparoscopic surgery. This trainer’s disadvantages are that it is a low-fidelity unit that is procedure agnostic. For more information, visit the Limbs & Things website at https://www.fls-products.com.

Notably, ObGyn residents who graduate after May 31, 2020, will be required to successfully complete the FLS program as a prerequisite for specialty board certification.2 The FLS program is endorsed by the American College of Surgeons and is run through the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. The FLS test is proctored and must be taken at a testing center.

Takeaway. The FLS trainer box is readily available, portable, relatively inexpensive, low-tech, and has valid benchmarks for proficiency. The FLS test will be required for ObGyn residents by 2020.

The SimPraxis software trainer

The SimPraxis Laparoscopic Hysterectomy Trainer (Red Llama, Inc) is an interactive simulation software platform that is available in DVD or USB format (FIGURE 4). The software is designed to review anatomy, surgical instrumentation, and specific steps of the procedure. It provides formative assessments and offers summative feedback for users.

The SimPraxis training software would make a useful tool to familiarize medical students and interns with the basics of the procedure before advancing to other simulation trainers. The software costs $100. For more information, visit https://www.3-dmed.com/product/simpraxis%C3%82%C2%AE-laparoscopic-hysterectomy-trainer.

Takeaway. The SimPraxis software is ideal for novice learners and can be used on a home or office computer.

The LapSim virtual reality trainer

The LapSim Haptic System (Surgical Science) is a virtual reality skills trainer. The hysterectomy module includes right and left uterine artery dissection, vaginal cuff opening, and cuff closure (FIGURE 5). One advantage of this simulator is its haptic feedback system, which enhances the fidelity of the training.

The LapSim simulator includes a training module for students and early learners and modules to improve camera handling. The virtual reality base system costs $70,720, and the hysterectomy software module is an additional $15,600.

For more information, visit the company’s website at https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/. For an informational video, go to https://surgicalscience.com/systems/lapsim/video/.

Takeaway. The LapSim is an expensive, high-fidelity, virtual reality simulator with enhanced haptics and software for practicing laparoscopic hysterectomy.

The LAP Mentor virtual reality simulator

The LAP Mentor VR (3D Systems) is another virtual reality simulator that has modules for laparoscopic hysterectomy and cuff closure (FIGURE 6). The trainee uses a virtual reality headset and becomes fully immersed in the operating room environment with audio and visual cues that mimic a real surgical experience.

The hysterectomy module allows the user to manipulate the uterus, identify the ureters, divide the superior pedicles, mobilize the bladder, expose and divide the uterine artery, and perform the colpotomy. The cuff closure module allows the user to suture the vaginal cuff using barbed suture. The module also can expose the learner to complications, such as bladder, ureteral, colon, or vascular injury.

The LAP Mentor VR base system costs $84,000 and the modules cost about $15,000. For additional information, visit the company’s website at http://simbionix.com/simulators/lap-mentor/lap-mentor-vr-or/.

Takeaway. The LAP Mentor is an expensive, high-fidelity simulation platform with a virtual reality headset that simulates a laparoscopic hysterectomy (with complications) in the operating room.

Read about simulations models for robot-assisted lap hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy.

Simulation models for training in robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy

All robot-assisted simulation platforms have highly realistic graphics, and they are expensive (TABLE). However, the da Vinci Skills Simulator (backpack) platform is included with the da Vinci Si and Xi Systems. Note, though, that it can be challenging to access the surgeon console and backpack at institutions with high volumes of robot-assisted surgery.

Other options that generally reside outside of the operating room include Mimic’s FlexVR and dV-Trainer and the Robotix Mentor by 3D Systems (FIGURES 7–11). Mimic’s new technology, called MaestroAR (augmented reality), allows trainees to manipulate virtual robotic instruments to interact with anatomic regions within augmented 3D surgical video footage, with narration and instruction by Dr. Arnold Advincula.

Newer software by Simbionix allows augmented reality to assist the simulation of robot-assisted hysterectomy with the da Vinci Xi backpack and RobotiX platforms.

Models for training in abdominal hysterectomy

In the last 10 years, there has been a 30% decrease in the number of abdominal hysterectomies performed by residents.1 Because of this decline in operating room experience, simulation training can be an important tool to bolster residency experience.

There are not many simulation models available for teaching abdominal hysterectomy, but here we discuss 2 that we utilize in our residency program.

Adaptable task trainer

The Surgical Female Pelvic Trainer (SFPT) (Limbs & Things Ltd), a pelvic task trainer primarily used for simulation of laparoscopic hysterectomy, can be adapted for abdominal hysterectomy by removing the abdominal cover (FIGURE 12). This trainer can be used with simulated blood to increase the realism of training. The SFPT trainer costs $2,190. For more information, go to https://www.limbsandthings.com/us/our-products/details/surgical-female-pelvic-trainer-sfpt-mk-2.

Takeaway. The SFPT is a medium-fidelity task trainer with a reusable base and consumable replacement parts.

ACOG’s do-it-yourself flower pot model

The flower pot model (developed by the ACOG Simulation Working Group, Washington, DC) is a comprehensive educational package that includes learning objectives, simulation construction instructions, content review of the abdominal hysterectomy, quiz, and evaluation form.3 ACOG has endorsed this low-cost model for residency education. Each model costs approximately $20, and the base (flower pot) is reusable (FIGURE 13).Construction time for each model is 30 to 60 minutes, and learners can participate in the construction. This can aid in anatomy review and familiarization with the model prior to training in the surgical procedure.

The learning objectives, content review, quiz, and evaluation form can be used for the flower pot model or for high-fidelity models.

The advantages of this model are the low cost and that it provides enough fidelity to teach each of the critical steps of the procedure. The disadvantages include that it is a lower-fidelity model, requires a considerable amount of time for construction, does not bleed, and is not compatible with energy devices. This model also can be used for training in laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy. For more information, visit ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum website at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/.

Takeaway. ACOG’s flower pot model for hysterectomy training is a comprehensive, low-cost, low-fidelity simulation model that requires significant setup time.

Simulation’s offerings

Simulation training is the present and future of medicine that bridges the gap between textbook learning and technical proficiency. Although in this article we describe only a handful of the simulation resources available, we hope that you will incorporate such tools into your practice for continuing education and skill development. Utilize peer-reviewed resources, such as the ACOG curriculum module and evaluation tools for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal hysterectomy, which can be used with any simulation model to provide a comprehensive and complimentary learning experience.

The future of health care depends on the commitment and ingenuity of educators who embrace medical simulation’s purpose: improved patient safety, effectiveness, and efficiency. Join the movement!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Due to an increase in minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy, including vaginal and laparoscopic approaches, gynecologic surgeons may need to turn to simulation training to augment practice and hone skills. Simulation is useful for all surgeons, especially for low-volume surgeons, as a warm-up to sharpen technical skills prior to starting the day’s cases. Additionally, educators are uniquely poised to use simulation to teach residents and to evaluate their procedural competency.

In this article, we provide an overview of the 3 approaches to hysterectomy—vaginal, laparoscopic, abdominal—through medical modeling and simulation techniques. We focus on practical issues, including current resources available online, cost, setup time, fidelity, and limitations of some commonly available vaginal, laparoscopic, and open hysterectomy models.

Simulation directly influences patient safety. Thus, the value of simulation cannot be overstated, as it can increase the quality of health care by improving patient outcomes and lowering overall costs. In 2008, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) founded the Simulations Working Group to establish simulation as a pillar in education for women’s health through collaboration, advocacy, research, and the development and implementation of multidisciplinary simulations-based educational resources and opportunities.

Refer to the ACOG Simulations Working Group Toolkit online to see the objectives, simulation, and videos related to each module. Under the “Hysterectomy” section, you will find how to construct the “flower pot” model for abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy, as well as the AAGL vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy webinars. All content is reaffirmed frequently to keep it up to date. You can access the toolkit, with your ACOG login and passcode, at https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Simulations-Consortium/Simulations-Consortium-Tool-Kit.

For a comprehensive gynecology curriculum to include vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal approaches to hysterectomy, refer to ACOG’s Surgical Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology page at https://cfweb.acog.org/scog/. This page lists the standardized surgical skills curriculum for use in training residents in obstetrics and gynecology by procedure. It includes:

- the objective, description, and assessment of the module

- a description of the simulation

- a description of the surgical procedure

- a quiz that must be passed to proceed to evaluation by a faculty member

- an evaluation form to be downloaded and printed by the learner.

Takeaway. Value of Simulation = Quality (Improved Patient Outcomes) ÷ Direct and Indirect Costs.

Simulation models for training in vaginal hysterectomy

According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the minimum number of vaginal hysterectomies is 15; this number represents the minimum accepted exposure, however, and does not imply competency. Exposure to vaginal hysterectomy in residency training has significantly declined over the years, with a mean of only 19 vaginal hysterectomies performed by the time of graduation in 2014.1

A wide range of simulation models are available that you either can construct or purchase, based on your budget. We discuss 3 such models below.

The Miya model