User login

Exploring multidisciplinary treatments in the traumatizing aspects of chronic abdominal pain

Introduction

Abdominal pain is a complex phenomenon that involves unpleasant sensory and emotional experiences caused by actual or potential visceral tissue damage. As pain becomes chronic, there is a functional reorganization of the brain involved in emotional and cognitive processing leading to amplification of pain perception and associated pain suffering.1,2 With the rising recognition of the complexity of pain management in the 1960s, the treatment of pain became a recognized field of study, leading to the formation of interdisciplinary teams to treat pain. However, although efficacious, this model lacked adequate reimbursement structures and eventually subsided as opioids (which at the time were widely believed to be nonaddictive) become more prevalent.3 Not only is there a lack of empirical evidence for opioids in the management of chronic abdominal pain, there is a growing list of adverse consequences of prolonged opioid use for both the brain and gastrointestinal tract.4

Recently, there has been more clinical focus on behavioral interventions that can modulate gut pain signals and associated behaviors by reversing maladaptive emotional and cognitive brain processes.5 One such psychological process that has received little attention is the traumatizing nature of chronic abdominal pain. Chronic pain, particularly when it feels uncontrollable to patients, activates the brain’s fear circuitry and drives hyperarousal, emotional numbing, and consolidation of painful somatic memories, which become habitual and further amplify negative visceral signals.6,7 These processes are identical to the symptom manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as intrusiveness, avoidance, negative mood and cognitions, and hyperarousal from life events. In fact, individuals with a history of other traumatizing exposures have an even higher risk of developing chronic pain disorders.8 This review has two objectives: to provide a theoretical framework for understanding chronic pain as a traumatizing experience with posttraumatic manifestations and to discuss behavioral interventions and adjunctive nonopioid pharmacotherapy embedded in multidisciplinary care models essential to reversing this negative brain-gut cycle and reducing pain-related suffering.

Trauma and chronic abdominal pain

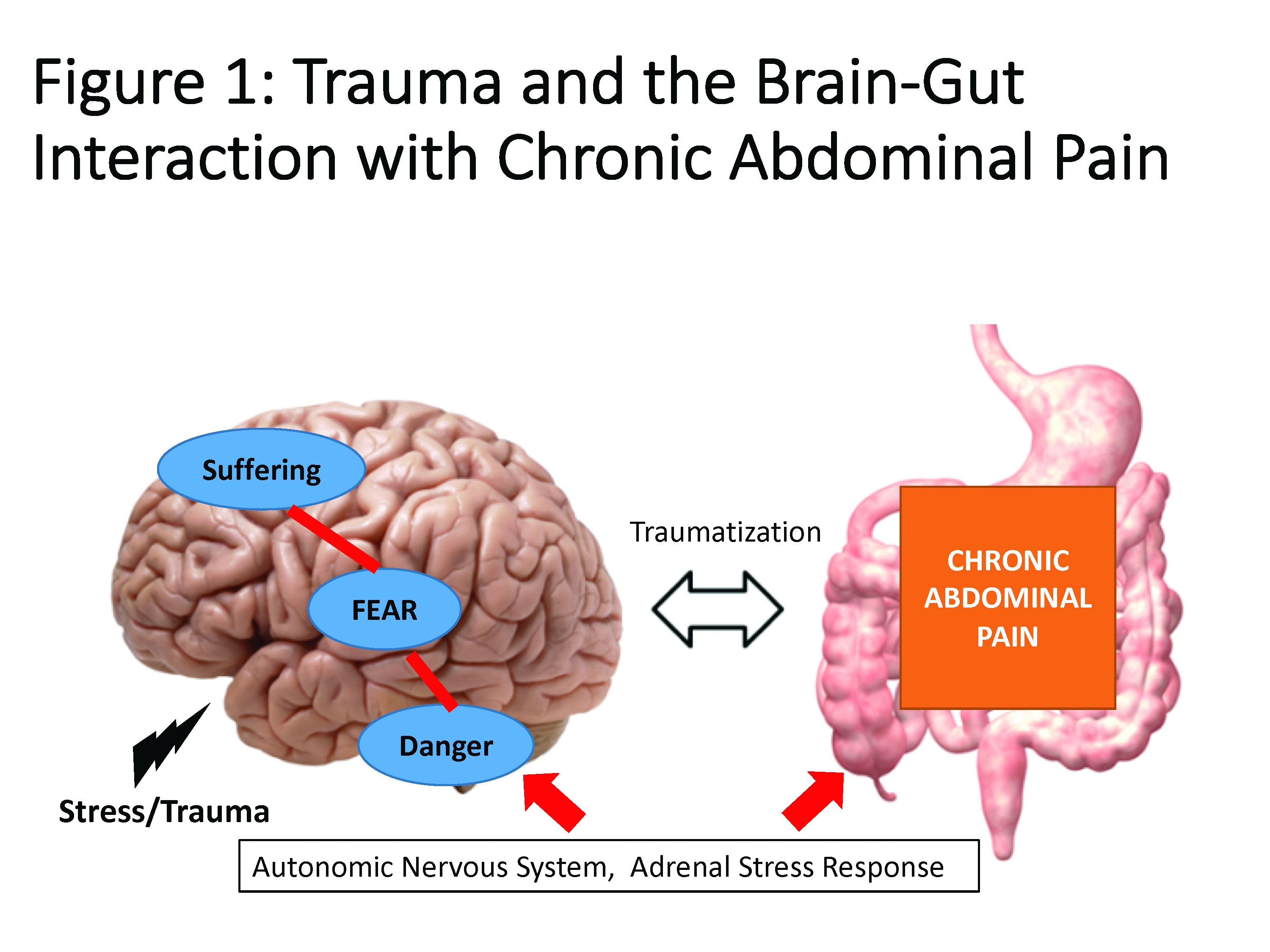

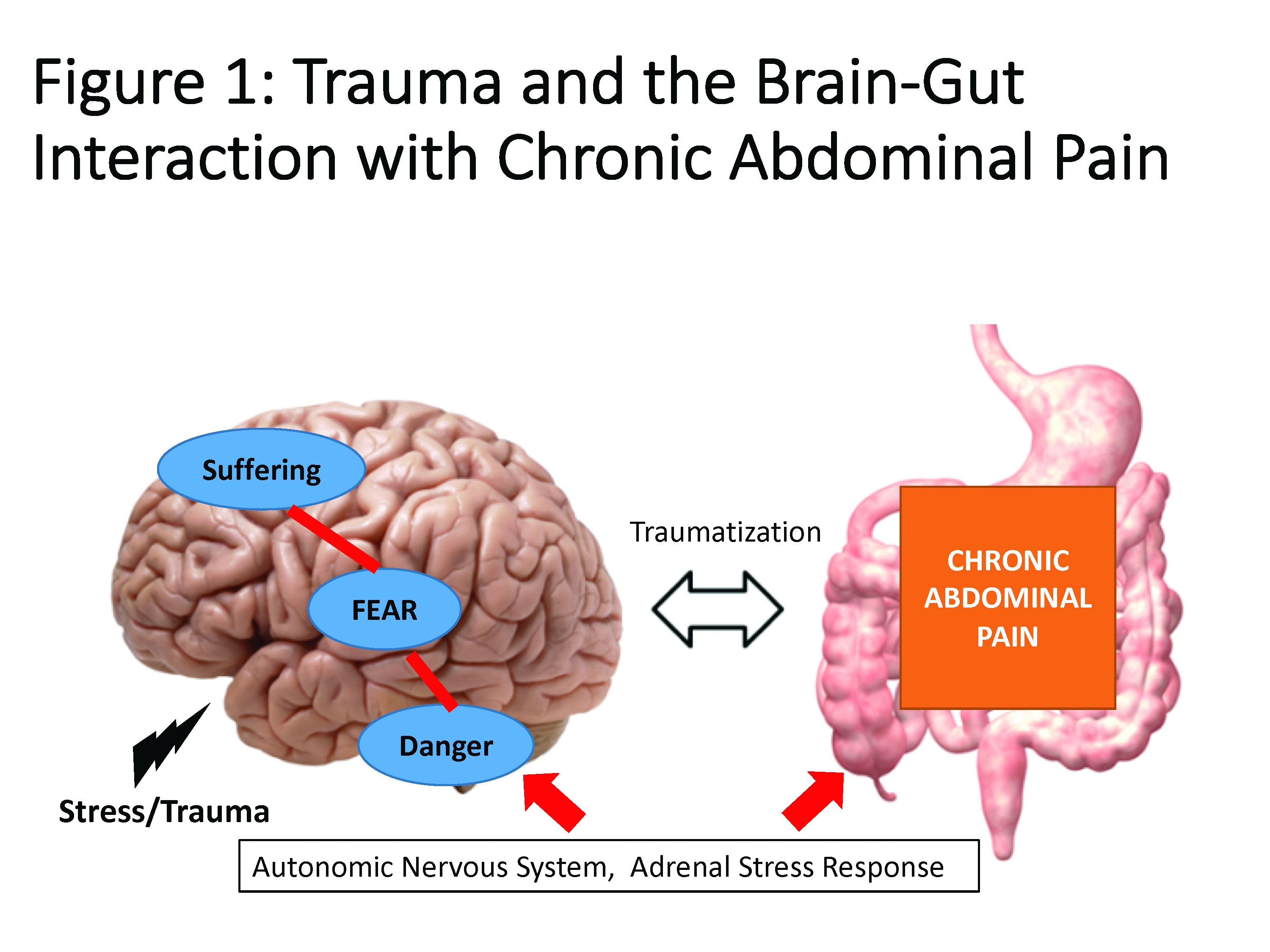

Trauma is defined as an individual’s response to a threat to safety. Traumatized patients or those with PTSD are at higher risk for chronic abdominal pain.9 Given the strong neurobiological connection between the brain and gut that has been phylogenetically preserved, emotional (e.g., fear, terror) or physical (e.g., pain) signals represent danger, and with chronicity, there can be a kindling-related consolidation of these maladaptive neurobiological pathways leading to suffering (e.g., hopelessness, sense of failure) and disability (Figure 1).

The interrelationship between chronic pain and trauma is multifaceted and is further complicated by the traumatizing nature of chronic pain itself, when pain is interpreted as a signal that the body is sick or even dangerously ill. Patients with chronic abdominal pain may seek multiple medical opinions and often undergo extensive, unnecessary, and sometimes harmful interventions to find the cause of their pain, with fear of disability and even death driving this search for answers.

The degree to which an individual with long-lasting pain interprets their discomfort as a risk to their well-being is related to the degree of trauma they experience because of their pain.10 Indeed, many of the negative symptoms associated with posttraumatic stress are also found in those with chronic abdominal pain. Trauma impacts the fear circuitry centers of the brain, leading to altered activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the amygdala, as well as chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and stress-released hormones, all of which are potential pathways that dysregulate the brain-gut relationship.11-13 Worries for safety, which are reactivated by physiological cues (e.g., GI symptoms, pain), as well as avoidance of potential triggers of GI symptoms (e.g., food, exercise, medications, and situations such as travel or scheduled events, and fear of being trapped without bathroom access), are common. Traumatized individuals can experience a foreshortened sense of the future, which may lead to decreased investment in long-term determinants of health (e.g., balanced diet, exercise, social support) and have higher rates of functional impairment and higher health care utilization.14 Negative mood, including irritability, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and impaired concentration are common in those with trauma and chronic pain and can be accompanied by internalized blame (e.g., depression, substance abuse, suicidality) or externalized blame (e.g., negative relationships with health care providers, rejection from their support or faith system). These can be worsened by an impaired sense of trust, which impacts the patient-provider relationship and other sources of social support leading to lack of behavioral activation, anhedonia, and isolation.

Another commonality is hypervigilance, as those with chronic abdominal pain are often hyperaware of physical symptoms and always “on alert” for a signal indicative of a pain flare. Anxiety and depression frequently co-occur in populations with trauma and chronic pain; these diagnoses are associated with higher rates of catastrophizing and learned helplessness, which may be exacerbated by lack of a “cure” for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and chronic pain.15 These factors could potentially lead to lack of engagement with treatment or, alternatively, risky or destructive attempts to cure pain including dangerous complementary alternative treatments or substance abuse to numb sensations. Another feature of trauma in chronic pain is the sense of dissociation from and lack of control over the body, sometimes induced by negative medical experiences (e.g., unwanted physical examinations, medication side effects, traumatic procedures, or hospitalizations).16,17

The importance of treating trauma in the management of chronic pain

Behavioral treatment is increasingly being recognized as an essential component in the management of any chronic pain syndrome.18 The most studied psychosocial interventions for chronic abdominal pain are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and gut-focused hypnosis. CBT is usually a problem-focused, short-term intervention that can be delivered individually in the office, via group therapy, or through virtual platforms. CBT is most effective when cognitive distortions and ineffective behaviors create emotional distress, and the therapy targets patient’s stress reactivity, visceral anxiety, catastrophizing, and inflexible coping styles.5 Gut-focused hypnosis is the second most–studied behavioral treatment for chronic abdominal pain and utilizes the trance state to make positive suggestions leading to broad and lasting physiological and psychological improvement.19 In addition to pain management, both CBT and hypnosis are efficacious treatments for PTSD.20,21

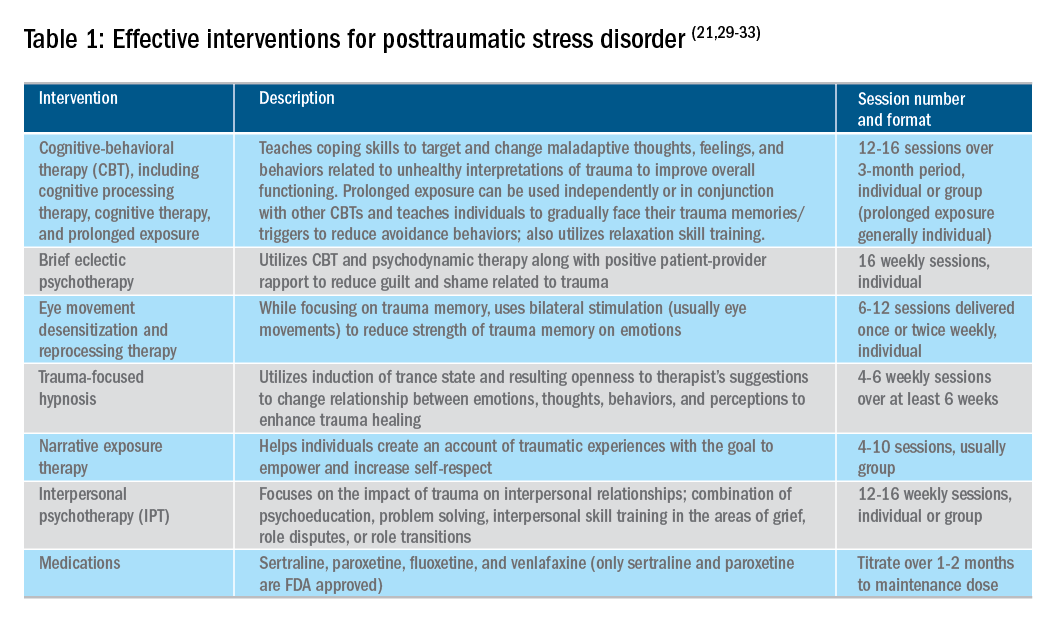

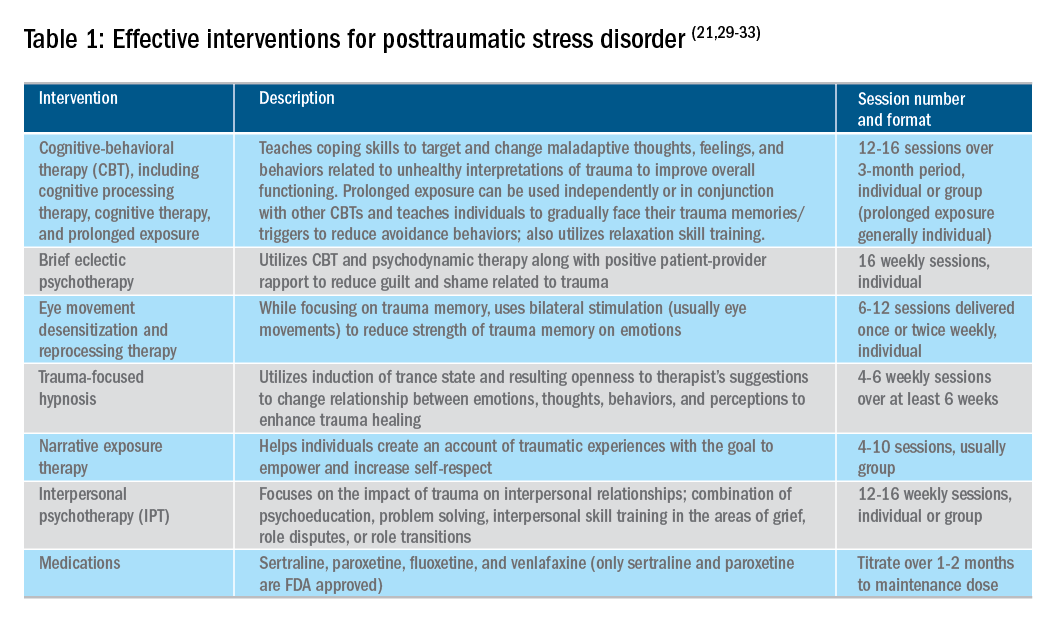

Utilizing a multidisciplinary medical team including integrated behavioral experts, such as in a patient-centered medical home, is considered the standard of care for treatment of chronic pain. The patient-provider relationship is essential, as is consistent follow-up to ensure effective symptom management and improvements in quality of life. Additionally, patient education, including a positive (i.e., clear) diagnosis and information on the brain-gut relationship, is associated with symptom improvement. In our subspecialty medical home for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we found that, in our patients who were on opioids for their chronic pain, engagement with our embedded behavioral and pain specialists resulted in significant reduction in opioid use and depression as well as improved self-reported quality of life.22 Gastroenterologists and advanced-practice providers operating without embedded behavioral therapists can consider referring patients to behavioral treatment (e.g., licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists; the latter often specialize in medication management and may not offer behavioral therapy) for trauma if patients have undergone a traumatic event (e.g., exposure to any potentially life-threatening event, serious injury, or violence) at any point in their lifetime and are experiencing intrusive symptoms (e.g., memories, dreams, or flashbacks to trauma), avoidance of trauma reminders, and negative mood or hyperarousal related to traumatic events (Table 1).23

With the traumatization component of chronic abdominal pain, which can further drive maladaptive coping cycles, incorporation of trauma-informed treatment into gastroenterology clinics is an avenue toward more effective treatment. The core principles of trauma-informed care include safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment,24 and are easily aligned with patient-centered models of care such as the interdisciplinary medical home model. Incorporation of screening techniques, interdisciplinary training of clinicians, and use of behavioral providers with experience in evidenced-based treatments of trauma enhance a clinic’s ability to effectively identify and treat individuals who have trauma because of their abdominal pain.25 Additionally, the most common behavioral interventions for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are also efficacious in the treatment of trauma. CBT is a well-validated treatment for PTSD that utilizes exposure therapy to help individuals restructure negative beliefs shaped by their negative experience and develop relaxation skills. Hypnosis is also validated in the treatment of trauma, with the possible mechanism of action being the replacement of the negative or dissociated traumatic trance with a healthy, adaptive trance facilitated by the hypnotherapist.21

Adjunctive nonopioid medications for chronic abdominal pain

While there are few randomized controlled trials establishing efficacy of pharmacotherapy for sustained improvement of abdominal pain or related suffering, several small trials and consensus clinical expert opinion suggest partial improvement in these domains.26,27 Central neuromodulators that can attenuate chronic visceral pain include antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous system–targeted medications.26 Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine) are often first-line treatment for FGIDs.28 Serotonin noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran) are also effective in pain management. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) can be used, especially when comorbid depression, anxiety, and phobic disorders are present. Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone) are effective treatments for early satiety, nausea/vomiting, insomnia, and low weight. Augmenting agents are utilized when single agents do not provide maximum benefit, including quetiapine (disturbed sleep), bupropion (fatigue), aripiprazole, buspirone, and tandospirone (dyspeptic features and anxiety). Delta ligands including gabapentin and pregabalin are helpful for abdominal wall pain or fibromyalgia. Ketamine is a newer but promising pathway for treatment of pain and depression and is increasingly being utilized in outpatient settings. Additionally, partial opioid-receptor agonists including methadone and suboxone have been reported to decrease pain in addition to their efficacy in addiction recovery. Medical marijuana is another area of growing interest, and while research has yet to show a clear effect in pain management, it does appear helpful in nausea and appetite stimulation. Obtaining a therapeutic response is the first treatment goal, after which a patient should be monitored in at least 6-month intervals to ensure sustained benefits and tolerability, and if these are not met, enhancement of treatment or a slow taper is indicated. As in all treatments, a positive patient-provider relationship predicts improved treatment adherence and outcomes.26 However, while these pharmacological interventions can reduce symptom severity, there is little evidence that they reduce traumatization without adjunctive psychotherapy.29

Summary

Both behavioral and pharmacological treatment options are available for chronic abdominal pain and most useful if traumatic manifestations are assessed and included as treatment targets. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of chronic abdominal pain with increased screening and treatment of trauma is a promising pathway to improved care and management for patients with chronic pain. If trauma is left untreated, the benefits of otherwise effective treatments are likely to be significantly limited.

References

1. Apkarian AV et al. Prog Neurobiol. 2009 Feb;87(2):81-97.

2. Gallagher RM et al. Pain Med. 2011 Jan;12(1):1-2.

3. Collier R et al. CMAJ. 2018 Jan 8;190(1):E26-7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5523.

4. Szigethy E et al. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018;15:168-80.

5. Ballou S et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;8(1):e214.

6. Egloff N et al. J Pain Res. 2013 Nov 5;6:765-70.

7. Fashler S et al. J Pain Res. 2016 Aug 10;9:551-61.

8. McKernan LC et al. Clin J Pain. 2019 May;35(5):385-93.

9. Ju T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001153.

10. Fishbain DA et al. Pain Med. 2017 Apr 1;18(4):711-35.

11. Martin CR et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):133-48.

12. Osadchiy V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;17(2):322-32.

13. Brzozowski B et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016 Nov;14(8):892-900.

14. Outclat SD et al. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1872-9.

15. Asmundson GJ et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;Dec;47(10):930-7.

16. Taft TH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz032.

17. Duckworth MP et al. International Journal of Rehabilitation and Health, 2000 Apr;5(2):129-39.

18. Scascighini L et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 May;47(5):670-8.

19. Palsson O et al. European Gastroenterology & Hepatology Review. 2010;6(1):42-6.

20. Watkins LE et al. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;12:1-9.

21. O’Toole SK et al. J Trauma Stress. 2016 Feb;29(1):97-100.

22. Goldblum Y et al. Digestive Disease Week. San Diego. 2019. Abstract in press.

23. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (of Mental Disorders), Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

24. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2018. Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Retrieved from samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

25. Click BH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(5):681-94.

26. Drossman DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1140-71.

27. Thorkelson G et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jun 1;22(6):1509-22.

28. Törnblom H et al. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2018;20(12):58.

29. Watkins LE et al. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:258.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. 2017.

31. Bisson JI et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Dec 13;(12):CD003388.

32. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. 2017.

33. Karatzias T et al. Psychol Med. 2019 Mar 12:1-15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000436. Advance online publication.

Emily Weaver, LCSW, is a UPMC Total Care–IBD program senior social worker, Eva Szigethy, MD, PhD, is professor of psychiatry and medicine, codirector, IBD Total Care Medical Home, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, departments of medicine and psychiatry.

Introduction

Abdominal pain is a complex phenomenon that involves unpleasant sensory and emotional experiences caused by actual or potential visceral tissue damage. As pain becomes chronic, there is a functional reorganization of the brain involved in emotional and cognitive processing leading to amplification of pain perception and associated pain suffering.1,2 With the rising recognition of the complexity of pain management in the 1960s, the treatment of pain became a recognized field of study, leading to the formation of interdisciplinary teams to treat pain. However, although efficacious, this model lacked adequate reimbursement structures and eventually subsided as opioids (which at the time were widely believed to be nonaddictive) become more prevalent.3 Not only is there a lack of empirical evidence for opioids in the management of chronic abdominal pain, there is a growing list of adverse consequences of prolonged opioid use for both the brain and gastrointestinal tract.4

Recently, there has been more clinical focus on behavioral interventions that can modulate gut pain signals and associated behaviors by reversing maladaptive emotional and cognitive brain processes.5 One such psychological process that has received little attention is the traumatizing nature of chronic abdominal pain. Chronic pain, particularly when it feels uncontrollable to patients, activates the brain’s fear circuitry and drives hyperarousal, emotional numbing, and consolidation of painful somatic memories, which become habitual and further amplify negative visceral signals.6,7 These processes are identical to the symptom manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as intrusiveness, avoidance, negative mood and cognitions, and hyperarousal from life events. In fact, individuals with a history of other traumatizing exposures have an even higher risk of developing chronic pain disorders.8 This review has two objectives: to provide a theoretical framework for understanding chronic pain as a traumatizing experience with posttraumatic manifestations and to discuss behavioral interventions and adjunctive nonopioid pharmacotherapy embedded in multidisciplinary care models essential to reversing this negative brain-gut cycle and reducing pain-related suffering.

Trauma and chronic abdominal pain

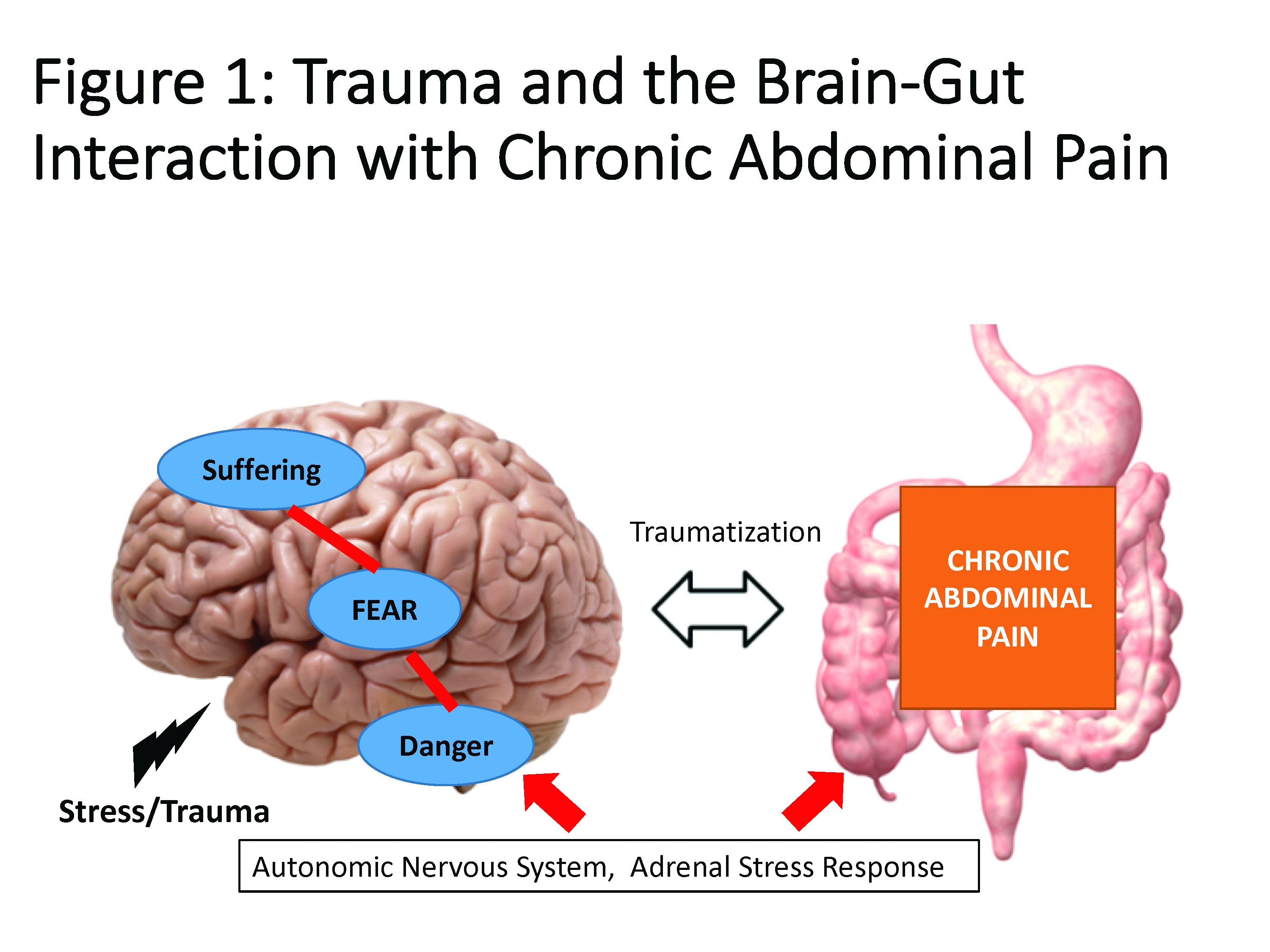

Trauma is defined as an individual’s response to a threat to safety. Traumatized patients or those with PTSD are at higher risk for chronic abdominal pain.9 Given the strong neurobiological connection between the brain and gut that has been phylogenetically preserved, emotional (e.g., fear, terror) or physical (e.g., pain) signals represent danger, and with chronicity, there can be a kindling-related consolidation of these maladaptive neurobiological pathways leading to suffering (e.g., hopelessness, sense of failure) and disability (Figure 1).

The interrelationship between chronic pain and trauma is multifaceted and is further complicated by the traumatizing nature of chronic pain itself, when pain is interpreted as a signal that the body is sick or even dangerously ill. Patients with chronic abdominal pain may seek multiple medical opinions and often undergo extensive, unnecessary, and sometimes harmful interventions to find the cause of their pain, with fear of disability and even death driving this search for answers.

The degree to which an individual with long-lasting pain interprets their discomfort as a risk to their well-being is related to the degree of trauma they experience because of their pain.10 Indeed, many of the negative symptoms associated with posttraumatic stress are also found in those with chronic abdominal pain. Trauma impacts the fear circuitry centers of the brain, leading to altered activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the amygdala, as well as chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and stress-released hormones, all of which are potential pathways that dysregulate the brain-gut relationship.11-13 Worries for safety, which are reactivated by physiological cues (e.g., GI symptoms, pain), as well as avoidance of potential triggers of GI symptoms (e.g., food, exercise, medications, and situations such as travel or scheduled events, and fear of being trapped without bathroom access), are common. Traumatized individuals can experience a foreshortened sense of the future, which may lead to decreased investment in long-term determinants of health (e.g., balanced diet, exercise, social support) and have higher rates of functional impairment and higher health care utilization.14 Negative mood, including irritability, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and impaired concentration are common in those with trauma and chronic pain and can be accompanied by internalized blame (e.g., depression, substance abuse, suicidality) or externalized blame (e.g., negative relationships with health care providers, rejection from their support or faith system). These can be worsened by an impaired sense of trust, which impacts the patient-provider relationship and other sources of social support leading to lack of behavioral activation, anhedonia, and isolation.

Another commonality is hypervigilance, as those with chronic abdominal pain are often hyperaware of physical symptoms and always “on alert” for a signal indicative of a pain flare. Anxiety and depression frequently co-occur in populations with trauma and chronic pain; these diagnoses are associated with higher rates of catastrophizing and learned helplessness, which may be exacerbated by lack of a “cure” for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and chronic pain.15 These factors could potentially lead to lack of engagement with treatment or, alternatively, risky or destructive attempts to cure pain including dangerous complementary alternative treatments or substance abuse to numb sensations. Another feature of trauma in chronic pain is the sense of dissociation from and lack of control over the body, sometimes induced by negative medical experiences (e.g., unwanted physical examinations, medication side effects, traumatic procedures, or hospitalizations).16,17

The importance of treating trauma in the management of chronic pain

Behavioral treatment is increasingly being recognized as an essential component in the management of any chronic pain syndrome.18 The most studied psychosocial interventions for chronic abdominal pain are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and gut-focused hypnosis. CBT is usually a problem-focused, short-term intervention that can be delivered individually in the office, via group therapy, or through virtual platforms. CBT is most effective when cognitive distortions and ineffective behaviors create emotional distress, and the therapy targets patient’s stress reactivity, visceral anxiety, catastrophizing, and inflexible coping styles.5 Gut-focused hypnosis is the second most–studied behavioral treatment for chronic abdominal pain and utilizes the trance state to make positive suggestions leading to broad and lasting physiological and psychological improvement.19 In addition to pain management, both CBT and hypnosis are efficacious treatments for PTSD.20,21

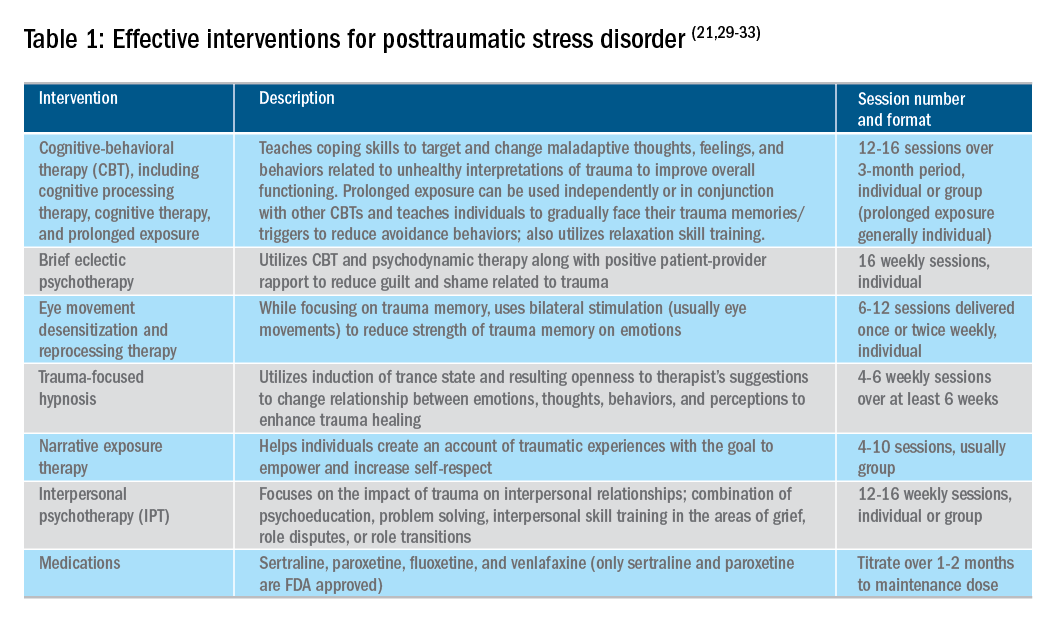

Utilizing a multidisciplinary medical team including integrated behavioral experts, such as in a patient-centered medical home, is considered the standard of care for treatment of chronic pain. The patient-provider relationship is essential, as is consistent follow-up to ensure effective symptom management and improvements in quality of life. Additionally, patient education, including a positive (i.e., clear) diagnosis and information on the brain-gut relationship, is associated with symptom improvement. In our subspecialty medical home for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we found that, in our patients who were on opioids for their chronic pain, engagement with our embedded behavioral and pain specialists resulted in significant reduction in opioid use and depression as well as improved self-reported quality of life.22 Gastroenterologists and advanced-practice providers operating without embedded behavioral therapists can consider referring patients to behavioral treatment (e.g., licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists; the latter often specialize in medication management and may not offer behavioral therapy) for trauma if patients have undergone a traumatic event (e.g., exposure to any potentially life-threatening event, serious injury, or violence) at any point in their lifetime and are experiencing intrusive symptoms (e.g., memories, dreams, or flashbacks to trauma), avoidance of trauma reminders, and negative mood or hyperarousal related to traumatic events (Table 1).23

With the traumatization component of chronic abdominal pain, which can further drive maladaptive coping cycles, incorporation of trauma-informed treatment into gastroenterology clinics is an avenue toward more effective treatment. The core principles of trauma-informed care include safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment,24 and are easily aligned with patient-centered models of care such as the interdisciplinary medical home model. Incorporation of screening techniques, interdisciplinary training of clinicians, and use of behavioral providers with experience in evidenced-based treatments of trauma enhance a clinic’s ability to effectively identify and treat individuals who have trauma because of their abdominal pain.25 Additionally, the most common behavioral interventions for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are also efficacious in the treatment of trauma. CBT is a well-validated treatment for PTSD that utilizes exposure therapy to help individuals restructure negative beliefs shaped by their negative experience and develop relaxation skills. Hypnosis is also validated in the treatment of trauma, with the possible mechanism of action being the replacement of the negative or dissociated traumatic trance with a healthy, adaptive trance facilitated by the hypnotherapist.21

Adjunctive nonopioid medications for chronic abdominal pain

While there are few randomized controlled trials establishing efficacy of pharmacotherapy for sustained improvement of abdominal pain or related suffering, several small trials and consensus clinical expert opinion suggest partial improvement in these domains.26,27 Central neuromodulators that can attenuate chronic visceral pain include antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous system–targeted medications.26 Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine) are often first-line treatment for FGIDs.28 Serotonin noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran) are also effective in pain management. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) can be used, especially when comorbid depression, anxiety, and phobic disorders are present. Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone) are effective treatments for early satiety, nausea/vomiting, insomnia, and low weight. Augmenting agents are utilized when single agents do not provide maximum benefit, including quetiapine (disturbed sleep), bupropion (fatigue), aripiprazole, buspirone, and tandospirone (dyspeptic features and anxiety). Delta ligands including gabapentin and pregabalin are helpful for abdominal wall pain or fibromyalgia. Ketamine is a newer but promising pathway for treatment of pain and depression and is increasingly being utilized in outpatient settings. Additionally, partial opioid-receptor agonists including methadone and suboxone have been reported to decrease pain in addition to their efficacy in addiction recovery. Medical marijuana is another area of growing interest, and while research has yet to show a clear effect in pain management, it does appear helpful in nausea and appetite stimulation. Obtaining a therapeutic response is the first treatment goal, after which a patient should be monitored in at least 6-month intervals to ensure sustained benefits and tolerability, and if these are not met, enhancement of treatment or a slow taper is indicated. As in all treatments, a positive patient-provider relationship predicts improved treatment adherence and outcomes.26 However, while these pharmacological interventions can reduce symptom severity, there is little evidence that they reduce traumatization without adjunctive psychotherapy.29

Summary

Both behavioral and pharmacological treatment options are available for chronic abdominal pain and most useful if traumatic manifestations are assessed and included as treatment targets. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of chronic abdominal pain with increased screening and treatment of trauma is a promising pathway to improved care and management for patients with chronic pain. If trauma is left untreated, the benefits of otherwise effective treatments are likely to be significantly limited.

References

1. Apkarian AV et al. Prog Neurobiol. 2009 Feb;87(2):81-97.

2. Gallagher RM et al. Pain Med. 2011 Jan;12(1):1-2.

3. Collier R et al. CMAJ. 2018 Jan 8;190(1):E26-7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5523.

4. Szigethy E et al. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018;15:168-80.

5. Ballou S et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;8(1):e214.

6. Egloff N et al. J Pain Res. 2013 Nov 5;6:765-70.

7. Fashler S et al. J Pain Res. 2016 Aug 10;9:551-61.

8. McKernan LC et al. Clin J Pain. 2019 May;35(5):385-93.

9. Ju T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001153.

10. Fishbain DA et al. Pain Med. 2017 Apr 1;18(4):711-35.

11. Martin CR et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):133-48.

12. Osadchiy V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;17(2):322-32.

13. Brzozowski B et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016 Nov;14(8):892-900.

14. Outclat SD et al. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1872-9.

15. Asmundson GJ et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;Dec;47(10):930-7.

16. Taft TH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz032.

17. Duckworth MP et al. International Journal of Rehabilitation and Health, 2000 Apr;5(2):129-39.

18. Scascighini L et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 May;47(5):670-8.

19. Palsson O et al. European Gastroenterology & Hepatology Review. 2010;6(1):42-6.

20. Watkins LE et al. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;12:1-9.

21. O’Toole SK et al. J Trauma Stress. 2016 Feb;29(1):97-100.

22. Goldblum Y et al. Digestive Disease Week. San Diego. 2019. Abstract in press.

23. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (of Mental Disorders), Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

24. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2018. Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Retrieved from samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

25. Click BH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(5):681-94.

26. Drossman DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1140-71.

27. Thorkelson G et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jun 1;22(6):1509-22.

28. Törnblom H et al. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2018;20(12):58.

29. Watkins LE et al. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:258.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. 2017.

31. Bisson JI et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Dec 13;(12):CD003388.

32. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. 2017.

33. Karatzias T et al. Psychol Med. 2019 Mar 12:1-15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000436. Advance online publication.

Emily Weaver, LCSW, is a UPMC Total Care–IBD program senior social worker, Eva Szigethy, MD, PhD, is professor of psychiatry and medicine, codirector, IBD Total Care Medical Home, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, departments of medicine and psychiatry.

Introduction

Abdominal pain is a complex phenomenon that involves unpleasant sensory and emotional experiences caused by actual or potential visceral tissue damage. As pain becomes chronic, there is a functional reorganization of the brain involved in emotional and cognitive processing leading to amplification of pain perception and associated pain suffering.1,2 With the rising recognition of the complexity of pain management in the 1960s, the treatment of pain became a recognized field of study, leading to the formation of interdisciplinary teams to treat pain. However, although efficacious, this model lacked adequate reimbursement structures and eventually subsided as opioids (which at the time were widely believed to be nonaddictive) become more prevalent.3 Not only is there a lack of empirical evidence for opioids in the management of chronic abdominal pain, there is a growing list of adverse consequences of prolonged opioid use for both the brain and gastrointestinal tract.4

Recently, there has been more clinical focus on behavioral interventions that can modulate gut pain signals and associated behaviors by reversing maladaptive emotional and cognitive brain processes.5 One such psychological process that has received little attention is the traumatizing nature of chronic abdominal pain. Chronic pain, particularly when it feels uncontrollable to patients, activates the brain’s fear circuitry and drives hyperarousal, emotional numbing, and consolidation of painful somatic memories, which become habitual and further amplify negative visceral signals.6,7 These processes are identical to the symptom manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as intrusiveness, avoidance, negative mood and cognitions, and hyperarousal from life events. In fact, individuals with a history of other traumatizing exposures have an even higher risk of developing chronic pain disorders.8 This review has two objectives: to provide a theoretical framework for understanding chronic pain as a traumatizing experience with posttraumatic manifestations and to discuss behavioral interventions and adjunctive nonopioid pharmacotherapy embedded in multidisciplinary care models essential to reversing this negative brain-gut cycle and reducing pain-related suffering.

Trauma and chronic abdominal pain

Trauma is defined as an individual’s response to a threat to safety. Traumatized patients or those with PTSD are at higher risk for chronic abdominal pain.9 Given the strong neurobiological connection between the brain and gut that has been phylogenetically preserved, emotional (e.g., fear, terror) or physical (e.g., pain) signals represent danger, and with chronicity, there can be a kindling-related consolidation of these maladaptive neurobiological pathways leading to suffering (e.g., hopelessness, sense of failure) and disability (Figure 1).

The interrelationship between chronic pain and trauma is multifaceted and is further complicated by the traumatizing nature of chronic pain itself, when pain is interpreted as a signal that the body is sick or even dangerously ill. Patients with chronic abdominal pain may seek multiple medical opinions and often undergo extensive, unnecessary, and sometimes harmful interventions to find the cause of their pain, with fear of disability and even death driving this search for answers.

The degree to which an individual with long-lasting pain interprets their discomfort as a risk to their well-being is related to the degree of trauma they experience because of their pain.10 Indeed, many of the negative symptoms associated with posttraumatic stress are also found in those with chronic abdominal pain. Trauma impacts the fear circuitry centers of the brain, leading to altered activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the amygdala, as well as chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and stress-released hormones, all of which are potential pathways that dysregulate the brain-gut relationship.11-13 Worries for safety, which are reactivated by physiological cues (e.g., GI symptoms, pain), as well as avoidance of potential triggers of GI symptoms (e.g., food, exercise, medications, and situations such as travel or scheduled events, and fear of being trapped without bathroom access), are common. Traumatized individuals can experience a foreshortened sense of the future, which may lead to decreased investment in long-term determinants of health (e.g., balanced diet, exercise, social support) and have higher rates of functional impairment and higher health care utilization.14 Negative mood, including irritability, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and impaired concentration are common in those with trauma and chronic pain and can be accompanied by internalized blame (e.g., depression, substance abuse, suicidality) or externalized blame (e.g., negative relationships with health care providers, rejection from their support or faith system). These can be worsened by an impaired sense of trust, which impacts the patient-provider relationship and other sources of social support leading to lack of behavioral activation, anhedonia, and isolation.

Another commonality is hypervigilance, as those with chronic abdominal pain are often hyperaware of physical symptoms and always “on alert” for a signal indicative of a pain flare. Anxiety and depression frequently co-occur in populations with trauma and chronic pain; these diagnoses are associated with higher rates of catastrophizing and learned helplessness, which may be exacerbated by lack of a “cure” for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and chronic pain.15 These factors could potentially lead to lack of engagement with treatment or, alternatively, risky or destructive attempts to cure pain including dangerous complementary alternative treatments or substance abuse to numb sensations. Another feature of trauma in chronic pain is the sense of dissociation from and lack of control over the body, sometimes induced by negative medical experiences (e.g., unwanted physical examinations, medication side effects, traumatic procedures, or hospitalizations).16,17

The importance of treating trauma in the management of chronic pain

Behavioral treatment is increasingly being recognized as an essential component in the management of any chronic pain syndrome.18 The most studied psychosocial interventions for chronic abdominal pain are cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and gut-focused hypnosis. CBT is usually a problem-focused, short-term intervention that can be delivered individually in the office, via group therapy, or through virtual platforms. CBT is most effective when cognitive distortions and ineffective behaviors create emotional distress, and the therapy targets patient’s stress reactivity, visceral anxiety, catastrophizing, and inflexible coping styles.5 Gut-focused hypnosis is the second most–studied behavioral treatment for chronic abdominal pain and utilizes the trance state to make positive suggestions leading to broad and lasting physiological and psychological improvement.19 In addition to pain management, both CBT and hypnosis are efficacious treatments for PTSD.20,21

Utilizing a multidisciplinary medical team including integrated behavioral experts, such as in a patient-centered medical home, is considered the standard of care for treatment of chronic pain. The patient-provider relationship is essential, as is consistent follow-up to ensure effective symptom management and improvements in quality of life. Additionally, patient education, including a positive (i.e., clear) diagnosis and information on the brain-gut relationship, is associated with symptom improvement. In our subspecialty medical home for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we found that, in our patients who were on opioids for their chronic pain, engagement with our embedded behavioral and pain specialists resulted in significant reduction in opioid use and depression as well as improved self-reported quality of life.22 Gastroenterologists and advanced-practice providers operating without embedded behavioral therapists can consider referring patients to behavioral treatment (e.g., licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists; the latter often specialize in medication management and may not offer behavioral therapy) for trauma if patients have undergone a traumatic event (e.g., exposure to any potentially life-threatening event, serious injury, or violence) at any point in their lifetime and are experiencing intrusive symptoms (e.g., memories, dreams, or flashbacks to trauma), avoidance of trauma reminders, and negative mood or hyperarousal related to traumatic events (Table 1).23

With the traumatization component of chronic abdominal pain, which can further drive maladaptive coping cycles, incorporation of trauma-informed treatment into gastroenterology clinics is an avenue toward more effective treatment. The core principles of trauma-informed care include safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment,24 and are easily aligned with patient-centered models of care such as the interdisciplinary medical home model. Incorporation of screening techniques, interdisciplinary training of clinicians, and use of behavioral providers with experience in evidenced-based treatments of trauma enhance a clinic’s ability to effectively identify and treat individuals who have trauma because of their abdominal pain.25 Additionally, the most common behavioral interventions for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are also efficacious in the treatment of trauma. CBT is a well-validated treatment for PTSD that utilizes exposure therapy to help individuals restructure negative beliefs shaped by their negative experience and develop relaxation skills. Hypnosis is also validated in the treatment of trauma, with the possible mechanism of action being the replacement of the negative or dissociated traumatic trance with a healthy, adaptive trance facilitated by the hypnotherapist.21

Adjunctive nonopioid medications for chronic abdominal pain

While there are few randomized controlled trials establishing efficacy of pharmacotherapy for sustained improvement of abdominal pain or related suffering, several small trials and consensus clinical expert opinion suggest partial improvement in these domains.26,27 Central neuromodulators that can attenuate chronic visceral pain include antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous system–targeted medications.26 Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine) are often first-line treatment for FGIDs.28 Serotonin noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran) are also effective in pain management. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) can be used, especially when comorbid depression, anxiety, and phobic disorders are present. Tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone) are effective treatments for early satiety, nausea/vomiting, insomnia, and low weight. Augmenting agents are utilized when single agents do not provide maximum benefit, including quetiapine (disturbed sleep), bupropion (fatigue), aripiprazole, buspirone, and tandospirone (dyspeptic features and anxiety). Delta ligands including gabapentin and pregabalin are helpful for abdominal wall pain or fibromyalgia. Ketamine is a newer but promising pathway for treatment of pain and depression and is increasingly being utilized in outpatient settings. Additionally, partial opioid-receptor agonists including methadone and suboxone have been reported to decrease pain in addition to their efficacy in addiction recovery. Medical marijuana is another area of growing interest, and while research has yet to show a clear effect in pain management, it does appear helpful in nausea and appetite stimulation. Obtaining a therapeutic response is the first treatment goal, after which a patient should be monitored in at least 6-month intervals to ensure sustained benefits and tolerability, and if these are not met, enhancement of treatment or a slow taper is indicated. As in all treatments, a positive patient-provider relationship predicts improved treatment adherence and outcomes.26 However, while these pharmacological interventions can reduce symptom severity, there is little evidence that they reduce traumatization without adjunctive psychotherapy.29

Summary

Both behavioral and pharmacological treatment options are available for chronic abdominal pain and most useful if traumatic manifestations are assessed and included as treatment targets. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of chronic abdominal pain with increased screening and treatment of trauma is a promising pathway to improved care and management for patients with chronic pain. If trauma is left untreated, the benefits of otherwise effective treatments are likely to be significantly limited.

References

1. Apkarian AV et al. Prog Neurobiol. 2009 Feb;87(2):81-97.

2. Gallagher RM et al. Pain Med. 2011 Jan;12(1):1-2.

3. Collier R et al. CMAJ. 2018 Jan 8;190(1):E26-7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-5523.

4. Szigethy E et al. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018;15:168-80.

5. Ballou S et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;8(1):e214.

6. Egloff N et al. J Pain Res. 2013 Nov 5;6:765-70.

7. Fashler S et al. J Pain Res. 2016 Aug 10;9:551-61.

8. McKernan LC et al. Clin J Pain. 2019 May;35(5):385-93.

9. Ju T et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 19. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001153.

10. Fishbain DA et al. Pain Med. 2017 Apr 1;18(4):711-35.

11. Martin CR et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):133-48.

12. Osadchiy V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;17(2):322-32.

13. Brzozowski B et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016 Nov;14(8):892-900.

14. Outclat SD et al. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1872-9.

15. Asmundson GJ et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;Dec;47(10):930-7.

16. Taft TH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019 Mar 7. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz032.

17. Duckworth MP et al. International Journal of Rehabilitation and Health, 2000 Apr;5(2):129-39.

18. Scascighini L et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 May;47(5):670-8.

19. Palsson O et al. European Gastroenterology & Hepatology Review. 2010;6(1):42-6.

20. Watkins LE et al. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;12:1-9.

21. O’Toole SK et al. J Trauma Stress. 2016 Feb;29(1):97-100.

22. Goldblum Y et al. Digestive Disease Week. San Diego. 2019. Abstract in press.

23. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (of Mental Disorders), Fifth Edition. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

24. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2018. Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Retrieved from samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

25. Click BH et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(5):681-94.

26. Drossman DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Mar;154(4):1140-71.

27. Thorkelson G et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jun 1;22(6):1509-22.

28. Törnblom H et al. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2018;20(12):58.

29. Watkins LE et al. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:258.

30. American Psychiatric Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. 2017.

31. Bisson JI et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Dec 13;(12):CD003388.

32. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. 2017.

33. Karatzias T et al. Psychol Med. 2019 Mar 12:1-15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000436. Advance online publication.

Emily Weaver, LCSW, is a UPMC Total Care–IBD program senior social worker, Eva Szigethy, MD, PhD, is professor of psychiatry and medicine, codirector, IBD Total Care Medical Home, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, departments of medicine and psychiatry.

Predictive analytics with large data sets are being pursued to individualize IBD therapy

SAN FRANCISCO – Predictive analytics of large quantities of data using machine learning present a powerful tool for improving therapeutic choices, according to a summary of work performed in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and presented at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

This type of work is relevant to many fields of medicine, but studies conducted in IBD have provided particularly compelling evidence that predictive analytics will improve outcomes and lead to more cost effective delivery of care, according to Akbar K. Waljee, MD, MSc, an associate professor in the division of gastroenterology at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a staff physician and researcher at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare system.

“We collect large amounts of clinical data every day in the delivery of health care, but we are now only just beginning to leverage [these] data to guide treatment,” Dr. Waljee said. He has now published several papers on the role of precision analytics of big data to improve treatment choices in IBD, as well as other diseases. These analyses are relevant for determining both who to treat with a certain drug and who to not treat with it.

In one example, data from 1,080 IBD patients taking thiopurines were used to develop a machine learning algorithm that analyzed multiple readily available variables, such as a complete blood count with differential and a chemistry panel, to predict whether someone was or was not in remission. This was then used to compare the mean yearly clinical event rates (new steroids prescriptions, hospitalizations, and abdominal surgeries) between the two groups (1.08 vs. 3.95 events) to show the associated clinical benefit of using this algorithm.

“The heterogeneity of response to therapies for IBD is well established. If machine learning predicts effective choices, there will be an opportunity to accelerate the time to disease control, as well as save costs by avoiding therapies not likely to be effective,” Dr. Waljee explained.

In another example, an algorithm was developed to predict the likelihood of achieving a corticosteroid-free biologic remission at 1 year in Crohn’s disease patients when patients were evaluated 6 weeks after initiating the gut-selective biologic vedolizumab. Again, it was based on an analysis of numerous variables, including laboratory data, sex, and race. Based on the model drawn from the analysis of 472 patients, 35.8% of the patients predicted to be in corticosteroid-free biologic remission at 1 year achieved this endpoint, whereas only 6.7% of the patients predicted to fail achieved the endpoint.

“This suggests that we can use an algorithm relatively early in the course of this biologic to predict who is going to respond,” reported Dr. Waljee. Again, patients with a low likelihood of response at 6 weeks can be started on an alternative treatment, which could potentially accelerate the time to disease control and avoid the costs of an ineffective and expensive treatment.

IBD is a particularly attractive focus of precision analytics with big data. IBD has a relatively unpredictable relapsing/remitting course and a heterogeneous response to available therapies. Algorithms predictive of response circumvent the inherent delays from evaluating disease control over an extended period.

“With ever increasing concern about costs of care and access to care, these treatment algorithms promise to use resources more efficiently,” Dr. Waljee said.

SAN FRANCISCO – Predictive analytics of large quantities of data using machine learning present a powerful tool for improving therapeutic choices, according to a summary of work performed in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and presented at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

This type of work is relevant to many fields of medicine, but studies conducted in IBD have provided particularly compelling evidence that predictive analytics will improve outcomes and lead to more cost effective delivery of care, according to Akbar K. Waljee, MD, MSc, an associate professor in the division of gastroenterology at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a staff physician and researcher at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare system.

“We collect large amounts of clinical data every day in the delivery of health care, but we are now only just beginning to leverage [these] data to guide treatment,” Dr. Waljee said. He has now published several papers on the role of precision analytics of big data to improve treatment choices in IBD, as well as other diseases. These analyses are relevant for determining both who to treat with a certain drug and who to not treat with it.

In one example, data from 1,080 IBD patients taking thiopurines were used to develop a machine learning algorithm that analyzed multiple readily available variables, such as a complete blood count with differential and a chemistry panel, to predict whether someone was or was not in remission. This was then used to compare the mean yearly clinical event rates (new steroids prescriptions, hospitalizations, and abdominal surgeries) between the two groups (1.08 vs. 3.95 events) to show the associated clinical benefit of using this algorithm.

“The heterogeneity of response to therapies for IBD is well established. If machine learning predicts effective choices, there will be an opportunity to accelerate the time to disease control, as well as save costs by avoiding therapies not likely to be effective,” Dr. Waljee explained.

In another example, an algorithm was developed to predict the likelihood of achieving a corticosteroid-free biologic remission at 1 year in Crohn’s disease patients when patients were evaluated 6 weeks after initiating the gut-selective biologic vedolizumab. Again, it was based on an analysis of numerous variables, including laboratory data, sex, and race. Based on the model drawn from the analysis of 472 patients, 35.8% of the patients predicted to be in corticosteroid-free biologic remission at 1 year achieved this endpoint, whereas only 6.7% of the patients predicted to fail achieved the endpoint.

“This suggests that we can use an algorithm relatively early in the course of this biologic to predict who is going to respond,” reported Dr. Waljee. Again, patients with a low likelihood of response at 6 weeks can be started on an alternative treatment, which could potentially accelerate the time to disease control and avoid the costs of an ineffective and expensive treatment.

IBD is a particularly attractive focus of precision analytics with big data. IBD has a relatively unpredictable relapsing/remitting course and a heterogeneous response to available therapies. Algorithms predictive of response circumvent the inherent delays from evaluating disease control over an extended period.

“With ever increasing concern about costs of care and access to care, these treatment algorithms promise to use resources more efficiently,” Dr. Waljee said.

SAN FRANCISCO – Predictive analytics of large quantities of data using machine learning present a powerful tool for improving therapeutic choices, according to a summary of work performed in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and presented at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

This type of work is relevant to many fields of medicine, but studies conducted in IBD have provided particularly compelling evidence that predictive analytics will improve outcomes and lead to more cost effective delivery of care, according to Akbar K. Waljee, MD, MSc, an associate professor in the division of gastroenterology at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a staff physician and researcher at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare system.

“We collect large amounts of clinical data every day in the delivery of health care, but we are now only just beginning to leverage [these] data to guide treatment,” Dr. Waljee said. He has now published several papers on the role of precision analytics of big data to improve treatment choices in IBD, as well as other diseases. These analyses are relevant for determining both who to treat with a certain drug and who to not treat with it.

In one example, data from 1,080 IBD patients taking thiopurines were used to develop a machine learning algorithm that analyzed multiple readily available variables, such as a complete blood count with differential and a chemistry panel, to predict whether someone was or was not in remission. This was then used to compare the mean yearly clinical event rates (new steroids prescriptions, hospitalizations, and abdominal surgeries) between the two groups (1.08 vs. 3.95 events) to show the associated clinical benefit of using this algorithm.

“The heterogeneity of response to therapies for IBD is well established. If machine learning predicts effective choices, there will be an opportunity to accelerate the time to disease control, as well as save costs by avoiding therapies not likely to be effective,” Dr. Waljee explained.

In another example, an algorithm was developed to predict the likelihood of achieving a corticosteroid-free biologic remission at 1 year in Crohn’s disease patients when patients were evaluated 6 weeks after initiating the gut-selective biologic vedolizumab. Again, it was based on an analysis of numerous variables, including laboratory data, sex, and race. Based on the model drawn from the analysis of 472 patients, 35.8% of the patients predicted to be in corticosteroid-free biologic remission at 1 year achieved this endpoint, whereas only 6.7% of the patients predicted to fail achieved the endpoint.

“This suggests that we can use an algorithm relatively early in the course of this biologic to predict who is going to respond,” reported Dr. Waljee. Again, patients with a low likelihood of response at 6 weeks can be started on an alternative treatment, which could potentially accelerate the time to disease control and avoid the costs of an ineffective and expensive treatment.

IBD is a particularly attractive focus of precision analytics with big data. IBD has a relatively unpredictable relapsing/remitting course and a heterogeneous response to available therapies. Algorithms predictive of response circumvent the inherent delays from evaluating disease control over an extended period.

“With ever increasing concern about costs of care and access to care, these treatment algorithms promise to use resources more efficiently,” Dr. Waljee said.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2019 AGA TECH SUMMIT

Five enter the Shark Tank, one emerges

SAN FRANCISCO – All five innovative startups pitched at the Shark Tank at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, are in advanced stages of development, but only one is given the opportunity to be declared the winner of the competition. The ideas ranged from a smart toilet for early disease detection to a unique strategy for obesity phenotyping, but the winner by both official decision and popular vote was a smartphone app to help patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) manage the condition.

“As always, this year’s Shark Tank was a highlight of the AGA Tech Summit and represents the progress our field is making when it comes to innovation. Our panel of sharks was focused on understanding the problem each innovation solved – that’s the key when determining if an idea is novel or innovation for innovation’s sake. We were impressed with all of the technologies presented, but ultimately chose the Oshi Health IBD app as our winner because of the impact it is already having on improving the health and care of IBD patients,” said V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

The winner: Oshi pitches “all-in-one” IBD app

By both popular vote from those attending the AGA Tech Summit as well as the six-member Shark Tank panel, Oshi Health was selected as the 2019 Shark Tank winner for its IBD app. The app was designed to help patients track symptoms, a first step in understanding flare patterns, which differ substantially between patients and emphasize the need for a personalized plan for controlling disease.

“Since we launched last June at DDW® we have had 40,000 downloads. We are the number one IBD management app,” reported Dan Weinstein, MBA, CEO of Oshi Health.

The available app represents the first of three phases as the functionality is expanded. Currently, in addition to using the app as a tracking tool, patients can find resources to learn about their disease and to communicate with other patients about their experiences. In a second phase, information gathered by the app will be made available to physicians to provide accurate current information about disease status to better individualize therapy.

Ultimately, the app is expected to guide treatment based on information it has collected on symptom patterns and other data collected over time, although this application is further down the road and will require regulatory approval if it is designed to provide clinical advice as expected, according to Mr. Weinstein.

However, benefits have already been seen. Mr. Weinstein cited data that associated the app with a 40% improvement in medication adherence and a nearly 60-day reduction in flare duration. Calling the app “the next chapter in treat-to-target” IBD management, he believes that this is an important step forward in digital health that will improve IBD outcomes. The Shark Tank panel agreed.

Runners-up: Other potential innovations to improve GI health

With or without Shark Tank endorsement, the other four startups described in the competition are moving forward. Each is designed to address an important unmet need with the potential to improve patient outcomes, which is a criterion for their inclusion in the competition.

The smart toilet seat

One involves a technologically advanced toilet seat. The new seat is based on the fact that fecal matter provides insight into a broad array of disease states, but specimen collection is a hurdle for a variety of reasons, including patient resistance. A toilet seat developed by Toi Labs, called TrueLoo, is equipped with lighting and cameras that captures images of bowel movements and urination for subsequent analysis.

“The toilet seat sees what the eye cannot,” according to Vikram Kashyap, CEO of Toi Labs. He believes it has major potential for early detection of conditions ranging from dehydration to gastrointestinal cancer.

Others agree. According to Mr. Kashyap, executives of a chain of senior living facilities have already expressed interest in installing this seat to better monitor health among residents. The seat is bolted into position in place of any standard toilet seat. It collects images and data that are transmitted directly to a cellular network.

“Using our technology, the goal is to catch disease states early before they progress,” said Mr. Kashyap, who called the surveillance system a low-cost disease-screening tool. He believes the smart toilet seat could be of the most important disease detection devices developed in recent years.

AI to aid screening endoscopy

A third entrant in this year’s Shark Tank described a strategy to employ artificial intelligence (AI) to aid endoscopists in screening for dysplasia. The tool is called Ultivision and is being developed by a startup called Docbot. The CEO, Andrew Ninh, and a senior executive, Jason B. Samarasena, MD, outlined an idea that could be used in either screening colonoscopy or in surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus).

“Dysplasia is difficult to find. It is subtle and it is often missed. With better detection of dysplasia, artificial intelligence offers an opportunity to reduce risk of cancer,” Dr. Samarasena said.

The tool integrates seamlessly with existing endoscopic tools, according to Mr. Ninh. As tissue is visualized, the AI is programmed to highlight suspected dysplasia with a colored box to alert the endoscopist. The colonoscopy application is a more advanced stage of development and might be submitted for regulatory approval this year, he said. The same technology will be adapted for Barrett’s esophagus.

“It is like facial recognition for dysplasia,” said Dr. Samarasena.

Obesity phenotyping tool

A fourth Shark Tank entrant employs technology to phenotype obese patients to better tailor therapy. The Pheno Test, developed by Phenomix Sciences, applies “multi-omics” to a blood-based test to separate patients with obesity into four phenotypes. When therapy is tailored to the phenotype, weight loss is greater, according to Andres J. Acosta, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine and consultant in gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

In an initial study that compared weight loss in 55 patients treated based on phenotype with 175 patients managed with standard of care, the total body weight loss “more than doubled,” Dr. Acosta reported.

According to Dr. Acosta, obesity is driven by very different mechanisms. He described the four major phenotypes identified with his test as hungry brain (satiation signal is impaired), hungry gut (signals to eat are upregulated), emotional hunger (psychological reasons drive eating behavior), and slow metabolism (failure to burn fat at normal rates).

With the blood test, which utilizes hormones, metabolites, DNA, and other biomarkers to separate these phenotypes, treatment can be tailored appropriately, according to Dr. Acosta. His company is now seeking Food and Drug Administration clearance of the test, which he believes will have a major impact on obesity control.

Capsule diagnostic tool

The final entrant selected to participate in this year’s Shark Tank described an ingestible capsule that diagnoses diseases by detecting gases as it descends the gastrointestinal tract. The Atmo Gas Capsule from Atmo Biosciences measures gases at the source, accelerating the diagnosis of such diseases as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and IBD.

“By measuring gases at their source, the accuracy is far better than a breath test,” said Malcolm Hebblewhite, MBA, CEO of Atmo Biosciences. The capsule is an alternative to more invasive and expensive diagnostic tools and it is highly accurate.

Providing examples, Mr. Hebblewhite said that elevated levels of oxygen suggest a disorder of motility while an elevated level of carbon dioxide and hydrogen suggest IBS. The capsule transmits data to a small receiver and then on to a smartphone.

“The real-time data is displayed for the user with more complex information accessible by the practitioner remotely via the cloud,” Mr. Hebblewhite said. He cited several papers that have already been published documenting the potential of this technology.

“The capsule is a single-use disposable device that is not retrieved,” according to Mr. Hebblewhite. He reported that his company plans to pursue the diagnosis of motility as an initial clinical application. The diagnosis of IBS and other GI conditions will follow. Clinical studies are already planned.

SAN FRANCISCO – All five innovative startups pitched at the Shark Tank at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, are in advanced stages of development, but only one is given the opportunity to be declared the winner of the competition. The ideas ranged from a smart toilet for early disease detection to a unique strategy for obesity phenotyping, but the winner by both official decision and popular vote was a smartphone app to help patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) manage the condition.

“As always, this year’s Shark Tank was a highlight of the AGA Tech Summit and represents the progress our field is making when it comes to innovation. Our panel of sharks was focused on understanding the problem each innovation solved – that’s the key when determining if an idea is novel or innovation for innovation’s sake. We were impressed with all of the technologies presented, but ultimately chose the Oshi Health IBD app as our winner because of the impact it is already having on improving the health and care of IBD patients,” said V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

The winner: Oshi pitches “all-in-one” IBD app

By both popular vote from those attending the AGA Tech Summit as well as the six-member Shark Tank panel, Oshi Health was selected as the 2019 Shark Tank winner for its IBD app. The app was designed to help patients track symptoms, a first step in understanding flare patterns, which differ substantially between patients and emphasize the need for a personalized plan for controlling disease.

“Since we launched last June at DDW® we have had 40,000 downloads. We are the number one IBD management app,” reported Dan Weinstein, MBA, CEO of Oshi Health.

The available app represents the first of three phases as the functionality is expanded. Currently, in addition to using the app as a tracking tool, patients can find resources to learn about their disease and to communicate with other patients about their experiences. In a second phase, information gathered by the app will be made available to physicians to provide accurate current information about disease status to better individualize therapy.

Ultimately, the app is expected to guide treatment based on information it has collected on symptom patterns and other data collected over time, although this application is further down the road and will require regulatory approval if it is designed to provide clinical advice as expected, according to Mr. Weinstein.

However, benefits have already been seen. Mr. Weinstein cited data that associated the app with a 40% improvement in medication adherence and a nearly 60-day reduction in flare duration. Calling the app “the next chapter in treat-to-target” IBD management, he believes that this is an important step forward in digital health that will improve IBD outcomes. The Shark Tank panel agreed.

Runners-up: Other potential innovations to improve GI health

With or without Shark Tank endorsement, the other four startups described in the competition are moving forward. Each is designed to address an important unmet need with the potential to improve patient outcomes, which is a criterion for their inclusion in the competition.

The smart toilet seat

One involves a technologically advanced toilet seat. The new seat is based on the fact that fecal matter provides insight into a broad array of disease states, but specimen collection is a hurdle for a variety of reasons, including patient resistance. A toilet seat developed by Toi Labs, called TrueLoo, is equipped with lighting and cameras that captures images of bowel movements and urination for subsequent analysis.

“The toilet seat sees what the eye cannot,” according to Vikram Kashyap, CEO of Toi Labs. He believes it has major potential for early detection of conditions ranging from dehydration to gastrointestinal cancer.

Others agree. According to Mr. Kashyap, executives of a chain of senior living facilities have already expressed interest in installing this seat to better monitor health among residents. The seat is bolted into position in place of any standard toilet seat. It collects images and data that are transmitted directly to a cellular network.

“Using our technology, the goal is to catch disease states early before they progress,” said Mr. Kashyap, who called the surveillance system a low-cost disease-screening tool. He believes the smart toilet seat could be of the most important disease detection devices developed in recent years.

AI to aid screening endoscopy

A third entrant in this year’s Shark Tank described a strategy to employ artificial intelligence (AI) to aid endoscopists in screening for dysplasia. The tool is called Ultivision and is being developed by a startup called Docbot. The CEO, Andrew Ninh, and a senior executive, Jason B. Samarasena, MD, outlined an idea that could be used in either screening colonoscopy or in surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus).

“Dysplasia is difficult to find. It is subtle and it is often missed. With better detection of dysplasia, artificial intelligence offers an opportunity to reduce risk of cancer,” Dr. Samarasena said.

The tool integrates seamlessly with existing endoscopic tools, according to Mr. Ninh. As tissue is visualized, the AI is programmed to highlight suspected dysplasia with a colored box to alert the endoscopist. The colonoscopy application is a more advanced stage of development and might be submitted for regulatory approval this year, he said. The same technology will be adapted for Barrett’s esophagus.

“It is like facial recognition for dysplasia,” said Dr. Samarasena.

Obesity phenotyping tool

A fourth Shark Tank entrant employs technology to phenotype obese patients to better tailor therapy. The Pheno Test, developed by Phenomix Sciences, applies “multi-omics” to a blood-based test to separate patients with obesity into four phenotypes. When therapy is tailored to the phenotype, weight loss is greater, according to Andres J. Acosta, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine and consultant in gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

In an initial study that compared weight loss in 55 patients treated based on phenotype with 175 patients managed with standard of care, the total body weight loss “more than doubled,” Dr. Acosta reported.

According to Dr. Acosta, obesity is driven by very different mechanisms. He described the four major phenotypes identified with his test as hungry brain (satiation signal is impaired), hungry gut (signals to eat are upregulated), emotional hunger (psychological reasons drive eating behavior), and slow metabolism (failure to burn fat at normal rates).

With the blood test, which utilizes hormones, metabolites, DNA, and other biomarkers to separate these phenotypes, treatment can be tailored appropriately, according to Dr. Acosta. His company is now seeking Food and Drug Administration clearance of the test, which he believes will have a major impact on obesity control.

Capsule diagnostic tool

The final entrant selected to participate in this year’s Shark Tank described an ingestible capsule that diagnoses diseases by detecting gases as it descends the gastrointestinal tract. The Atmo Gas Capsule from Atmo Biosciences measures gases at the source, accelerating the diagnosis of such diseases as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and IBD.

“By measuring gases at their source, the accuracy is far better than a breath test,” said Malcolm Hebblewhite, MBA, CEO of Atmo Biosciences. The capsule is an alternative to more invasive and expensive diagnostic tools and it is highly accurate.

Providing examples, Mr. Hebblewhite said that elevated levels of oxygen suggest a disorder of motility while an elevated level of carbon dioxide and hydrogen suggest IBS. The capsule transmits data to a small receiver and then on to a smartphone.

“The real-time data is displayed for the user with more complex information accessible by the practitioner remotely via the cloud,” Mr. Hebblewhite said. He cited several papers that have already been published documenting the potential of this technology.

“The capsule is a single-use disposable device that is not retrieved,” according to Mr. Hebblewhite. He reported that his company plans to pursue the diagnosis of motility as an initial clinical application. The diagnosis of IBS and other GI conditions will follow. Clinical studies are already planned.

SAN FRANCISCO – All five innovative startups pitched at the Shark Tank at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, are in advanced stages of development, but only one is given the opportunity to be declared the winner of the competition. The ideas ranged from a smart toilet for early disease detection to a unique strategy for obesity phenotyping, but the winner by both official decision and popular vote was a smartphone app to help patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) manage the condition.

“As always, this year’s Shark Tank was a highlight of the AGA Tech Summit and represents the progress our field is making when it comes to innovation. Our panel of sharks was focused on understanding the problem each innovation solved – that’s the key when determining if an idea is novel or innovation for innovation’s sake. We were impressed with all of the technologies presented, but ultimately chose the Oshi Health IBD app as our winner because of the impact it is already having on improving the health and care of IBD patients,” said V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

The winner: Oshi pitches “all-in-one” IBD app

By both popular vote from those attending the AGA Tech Summit as well as the six-member Shark Tank panel, Oshi Health was selected as the 2019 Shark Tank winner for its IBD app. The app was designed to help patients track symptoms, a first step in understanding flare patterns, which differ substantially between patients and emphasize the need for a personalized plan for controlling disease.

“Since we launched last June at DDW® we have had 40,000 downloads. We are the number one IBD management app,” reported Dan Weinstein, MBA, CEO of Oshi Health.

The available app represents the first of three phases as the functionality is expanded. Currently, in addition to using the app as a tracking tool, patients can find resources to learn about their disease and to communicate with other patients about their experiences. In a second phase, information gathered by the app will be made available to physicians to provide accurate current information about disease status to better individualize therapy.