User login

ASNC rejects new chest pain guideline it helped create

It was Oct. 28 when the two big North American cardiology societies issued a joint practice guideline on evaluating and managing chest pain that was endorsed by five other subspecialty groups. The next day, another group that had taken part in the document’s genesis explained why it wasn’t one of those five.

Although the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) was “actively engaged at every stage of the guideline-writing and review process,” the society “could not endorse the guideline,” the society announced in a statement released to clinicians and the media. The most prominent cited reason: It doesn’t adequately “support the principle of Patient First Imaging.”

The guideline was published in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, flagship journals of the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, respectively.

The document notes at least two clinicians represented ASNC as peer reviewers, and another was on the writing committee, but the organization does not appear in the list of societies endorsing the document.

“We believe that the document fails to provide unbiased guidance to health care professionals on the optimal evaluation of patients with chest pain,” contends an editorial ASNC board members have scheduled for the Jan. 10 issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine but is available now on an open-access preprint server.

“Despite the many important and helpful recommendations in the new guideline, there are several recommendations that we could not support,” it states.

“The ASNC board of directors reviewed the document twice during the endorsement process,” and the society “offered substantive comments after the first endorsement review, several of which were addressed,” Randall C. Thompson, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City, said in an interview.

“However, some of the board’s concerns went unresolved. It was after the board’s second review, when the document had been declared finalized, that they voted not to endorse,” said Dr. Thompson, who is ASNC president.

“When we gather multiple organizations together to review and summarize the evidence, we work collaboratively to interpret the extensive catalog of peer-reviewed, published literature and create clinical practice recommendations,” Guideline Writing Committee Chair Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization in a prepared statement.

“The ASNC had a representative on the writing committee who is a coauthor on the paper and actively participated throughout the writing process the past 4 years,” she said. “The final guideline reflects the latest evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain, as agreed by the seven endorsing organizations.”

The document does not clearly note that an ASNC representative was on the writing committee. However, ASNC confirmed that Renee Bullock-Palmer, MD, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, N.J., is a fellow of the ASNC and had represented the group as one of the coauthors. Two “official reviewers” of the document, however, are listed as ASNC representatives.

Points of contention

“The decision about which test to order can be a nuanced one, and cardiac imaging tests tend to be complementary,” elaborates the editorial on the issue of patient-centered management.

Careful patient selection for different tests is important, “and physician and technical local expertise, availability, quality of equipment, and patient preference are extremely important factors to consider. There is not enough emphasis on this important point,” contend the authors. “This is an important limitation of the guideline.”

Other issues of concern include “lack of balance in the document’s presentation of the science on FFR-CT [fractional flow reserve assessment with computed tomography] and its inappropriately prominent endorsement,” the editorial states.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration–recognized “limitations and contraindications” to FFR-CT tend to be glossed over in the document, Dr. Thompson said. And most ASNC board members were “concerned with the prominent location of the recommendations for FFR-CT in various tables – especially since there was minimal-to-no discussion of the fact that it is currently provided by only one company, that it is not widely available nor covered routinely by health insurance carriers, and [that] the accuracy in the most relevant population is disputed.”

In other concerns, the document “inadequately discusses the benefit” of combining coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores with functional testing, which ASNC said it supports. For example, adding CAC scores to myocardial perfusion imaging improves its diagnostic accuracy and prognostic power.

Functional vs. anatomic testing?

Moreover, “it is no longer appropriate to bundle all types of stress testing together. All stress imaging tests have their unique advantages and limitations.” Yet, “the concept of the dichotomy of functional testing versus anatomic testing is a common theme in the guideline in many important patient groups,” the editorial states. That could overemphasize CT angiography and thus “blur distinction between different types of functional tests.”

Such concerns about “imbalance” in the portrayals of the two kinds of tests were “amplified by the problem of health insurance companies and radiologic benefits managers inappropriately substituting a test that was ordered by a physician with a different test,” Dr. Thompson elaborated. “There is the impression that some of them ‘cherry-pick’ certain guidelines and that this practice is harmful to patients.”

The ASNC currently does not plan its own corresponding guideline, he said. But the editorial says that “over the coming weeks and months ASNC will offer a series of webinars and other programs that address specific patient populations and dilemmas.” Also, “we will enhance our focus on programs to address quality and efficiency to support a patient-first approach to imaging.”

The five subspecialty groups that have endorsed the document are the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Chest Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

Dr. Thompson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Statements of disclosure for the other editorial writers are listed in the publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was Oct. 28 when the two big North American cardiology societies issued a joint practice guideline on evaluating and managing chest pain that was endorsed by five other subspecialty groups. The next day, another group that had taken part in the document’s genesis explained why it wasn’t one of those five.

Although the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) was “actively engaged at every stage of the guideline-writing and review process,” the society “could not endorse the guideline,” the society announced in a statement released to clinicians and the media. The most prominent cited reason: It doesn’t adequately “support the principle of Patient First Imaging.”

The guideline was published in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, flagship journals of the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, respectively.

The document notes at least two clinicians represented ASNC as peer reviewers, and another was on the writing committee, but the organization does not appear in the list of societies endorsing the document.

“We believe that the document fails to provide unbiased guidance to health care professionals on the optimal evaluation of patients with chest pain,” contends an editorial ASNC board members have scheduled for the Jan. 10 issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine but is available now on an open-access preprint server.

“Despite the many important and helpful recommendations in the new guideline, there are several recommendations that we could not support,” it states.

“The ASNC board of directors reviewed the document twice during the endorsement process,” and the society “offered substantive comments after the first endorsement review, several of which were addressed,” Randall C. Thompson, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City, said in an interview.

“However, some of the board’s concerns went unresolved. It was after the board’s second review, when the document had been declared finalized, that they voted not to endorse,” said Dr. Thompson, who is ASNC president.

“When we gather multiple organizations together to review and summarize the evidence, we work collaboratively to interpret the extensive catalog of peer-reviewed, published literature and create clinical practice recommendations,” Guideline Writing Committee Chair Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization in a prepared statement.

“The ASNC had a representative on the writing committee who is a coauthor on the paper and actively participated throughout the writing process the past 4 years,” she said. “The final guideline reflects the latest evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain, as agreed by the seven endorsing organizations.”

The document does not clearly note that an ASNC representative was on the writing committee. However, ASNC confirmed that Renee Bullock-Palmer, MD, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, N.J., is a fellow of the ASNC and had represented the group as one of the coauthors. Two “official reviewers” of the document, however, are listed as ASNC representatives.

Points of contention

“The decision about which test to order can be a nuanced one, and cardiac imaging tests tend to be complementary,” elaborates the editorial on the issue of patient-centered management.

Careful patient selection for different tests is important, “and physician and technical local expertise, availability, quality of equipment, and patient preference are extremely important factors to consider. There is not enough emphasis on this important point,” contend the authors. “This is an important limitation of the guideline.”

Other issues of concern include “lack of balance in the document’s presentation of the science on FFR-CT [fractional flow reserve assessment with computed tomography] and its inappropriately prominent endorsement,” the editorial states.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration–recognized “limitations and contraindications” to FFR-CT tend to be glossed over in the document, Dr. Thompson said. And most ASNC board members were “concerned with the prominent location of the recommendations for FFR-CT in various tables – especially since there was minimal-to-no discussion of the fact that it is currently provided by only one company, that it is not widely available nor covered routinely by health insurance carriers, and [that] the accuracy in the most relevant population is disputed.”

In other concerns, the document “inadequately discusses the benefit” of combining coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores with functional testing, which ASNC said it supports. For example, adding CAC scores to myocardial perfusion imaging improves its diagnostic accuracy and prognostic power.

Functional vs. anatomic testing?

Moreover, “it is no longer appropriate to bundle all types of stress testing together. All stress imaging tests have their unique advantages and limitations.” Yet, “the concept of the dichotomy of functional testing versus anatomic testing is a common theme in the guideline in many important patient groups,” the editorial states. That could overemphasize CT angiography and thus “blur distinction between different types of functional tests.”

Such concerns about “imbalance” in the portrayals of the two kinds of tests were “amplified by the problem of health insurance companies and radiologic benefits managers inappropriately substituting a test that was ordered by a physician with a different test,” Dr. Thompson elaborated. “There is the impression that some of them ‘cherry-pick’ certain guidelines and that this practice is harmful to patients.”

The ASNC currently does not plan its own corresponding guideline, he said. But the editorial says that “over the coming weeks and months ASNC will offer a series of webinars and other programs that address specific patient populations and dilemmas.” Also, “we will enhance our focus on programs to address quality and efficiency to support a patient-first approach to imaging.”

The five subspecialty groups that have endorsed the document are the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Chest Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

Dr. Thompson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Statements of disclosure for the other editorial writers are listed in the publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was Oct. 28 when the two big North American cardiology societies issued a joint practice guideline on evaluating and managing chest pain that was endorsed by five other subspecialty groups. The next day, another group that had taken part in the document’s genesis explained why it wasn’t one of those five.

Although the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) was “actively engaged at every stage of the guideline-writing and review process,” the society “could not endorse the guideline,” the society announced in a statement released to clinicians and the media. The most prominent cited reason: It doesn’t adequately “support the principle of Patient First Imaging.”

The guideline was published in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, flagship journals of the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology, respectively.

The document notes at least two clinicians represented ASNC as peer reviewers, and another was on the writing committee, but the organization does not appear in the list of societies endorsing the document.

“We believe that the document fails to provide unbiased guidance to health care professionals on the optimal evaluation of patients with chest pain,” contends an editorial ASNC board members have scheduled for the Jan. 10 issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine but is available now on an open-access preprint server.

“Despite the many important and helpful recommendations in the new guideline, there are several recommendations that we could not support,” it states.

“The ASNC board of directors reviewed the document twice during the endorsement process,” and the society “offered substantive comments after the first endorsement review, several of which were addressed,” Randall C. Thompson, MD, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City, said in an interview.

“However, some of the board’s concerns went unresolved. It was after the board’s second review, when the document had been declared finalized, that they voted not to endorse,” said Dr. Thompson, who is ASNC president.

“When we gather multiple organizations together to review and summarize the evidence, we work collaboratively to interpret the extensive catalog of peer-reviewed, published literature and create clinical practice recommendations,” Guideline Writing Committee Chair Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, told this news organization in a prepared statement.

“The ASNC had a representative on the writing committee who is a coauthor on the paper and actively participated throughout the writing process the past 4 years,” she said. “The final guideline reflects the latest evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain, as agreed by the seven endorsing organizations.”

The document does not clearly note that an ASNC representative was on the writing committee. However, ASNC confirmed that Renee Bullock-Palmer, MD, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, N.J., is a fellow of the ASNC and had represented the group as one of the coauthors. Two “official reviewers” of the document, however, are listed as ASNC representatives.

Points of contention

“The decision about which test to order can be a nuanced one, and cardiac imaging tests tend to be complementary,” elaborates the editorial on the issue of patient-centered management.

Careful patient selection for different tests is important, “and physician and technical local expertise, availability, quality of equipment, and patient preference are extremely important factors to consider. There is not enough emphasis on this important point,” contend the authors. “This is an important limitation of the guideline.”

Other issues of concern include “lack of balance in the document’s presentation of the science on FFR-CT [fractional flow reserve assessment with computed tomography] and its inappropriately prominent endorsement,” the editorial states.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration–recognized “limitations and contraindications” to FFR-CT tend to be glossed over in the document, Dr. Thompson said. And most ASNC board members were “concerned with the prominent location of the recommendations for FFR-CT in various tables – especially since there was minimal-to-no discussion of the fact that it is currently provided by only one company, that it is not widely available nor covered routinely by health insurance carriers, and [that] the accuracy in the most relevant population is disputed.”

In other concerns, the document “inadequately discusses the benefit” of combining coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores with functional testing, which ASNC said it supports. For example, adding CAC scores to myocardial perfusion imaging improves its diagnostic accuracy and prognostic power.

Functional vs. anatomic testing?

Moreover, “it is no longer appropriate to bundle all types of stress testing together. All stress imaging tests have their unique advantages and limitations.” Yet, “the concept of the dichotomy of functional testing versus anatomic testing is a common theme in the guideline in many important patient groups,” the editorial states. That could overemphasize CT angiography and thus “blur distinction between different types of functional tests.”

Such concerns about “imbalance” in the portrayals of the two kinds of tests were “amplified by the problem of health insurance companies and radiologic benefits managers inappropriately substituting a test that was ordered by a physician with a different test,” Dr. Thompson elaborated. “There is the impression that some of them ‘cherry-pick’ certain guidelines and that this practice is harmful to patients.”

The ASNC currently does not plan its own corresponding guideline, he said. But the editorial says that “over the coming weeks and months ASNC will offer a series of webinars and other programs that address specific patient populations and dilemmas.” Also, “we will enhance our focus on programs to address quality and efficiency to support a patient-first approach to imaging.”

The five subspecialty groups that have endorsed the document are the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Chest Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance.

Dr. Thompson has reported no relevant financial relationships. Statements of disclosure for the other editorial writers are listed in the publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Neuroimaging may predict cognitive decline after chemotherapy for breast cancer

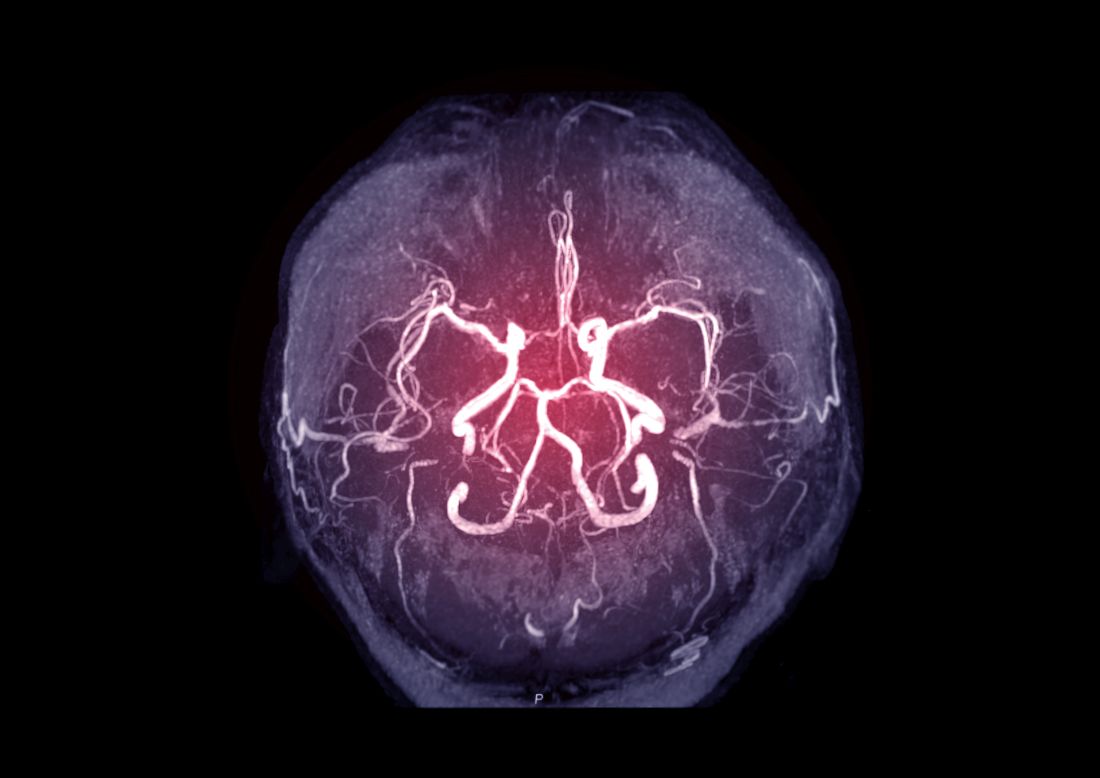

“Cognitive decline is frequently observed after chemotherapy,” according to Michiel B. de Ruiter, PhD, a research scientist with the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam. He specializes in cognitive neuroscience and was the lead author of a study published online Sept. 30, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. Dr. de Ruiter and colleagues found that fractional anisotropy may demonstrate a low brain white-matter reserve which could be a risk factor for cognitive decline after chemotherapy for breast cancer treatment.

Cognitive decline after chemotherapy has been reported in 20%-40% of patients with cancer affecting quality of life and daily living skills. Studies have suggested that genetic makeup, advanced age, fatigue, and premorbid intelligence quotient are risk factors for chemotherapy-associated cognitive decline. Changes in the microstructure of brain white matter, known as brain reserve, have been reported after exposure to chemotherapy, but its link to cognitive decline is understudied. Several studies outside of oncology have used MRI to derive fractional anisotropy as a measure for brain reserve.

In the new JCO study, researchers examined fractional anisotropy, as measured by MRI, before chemotherapy. The analysis included 49 patients who underwent neuropsychological tests before treatment with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, then again at 6 months and 2 years after chemotherapy.

The results were compared with those of patients with breast cancer who did not receive systemic therapy and then with a control group consisting of patients without cancer.

A low fractional anisotropy score suggested cognitive decline more than 3 years after receiving chemotherapy treatment. The finding was independent of age, premorbid intelligence quotient, baseline fatigue and baseline cognitive complaints. And, having low premorbid intelligence quotient was an independent risk factor for chemotherapy-associated cognitive decline, which the authors said is in line with previous findings.

Fractional anisotropy did not predict cognitive decline in patients who did not receive systemic therapy, as well as patients in the control group.

The findings could possibly lead to the development a pretreatment assessment to screen for patients who may at risk for cognitive decline, the authors wrote. “Clinically validated assessments of white-matter reserve as assessed with an MRI scan may be part of a pretreatment screening. This could also aid in early identification of cognitive decline after chemotherapy, allowing targeted and early interventions to improve cognitive problems,” such as psychoeducation and cognitive rehabilitation.

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

“Cognitive decline is frequently observed after chemotherapy,” according to Michiel B. de Ruiter, PhD, a research scientist with the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam. He specializes in cognitive neuroscience and was the lead author of a study published online Sept. 30, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. Dr. de Ruiter and colleagues found that fractional anisotropy may demonstrate a low brain white-matter reserve which could be a risk factor for cognitive decline after chemotherapy for breast cancer treatment.

Cognitive decline after chemotherapy has been reported in 20%-40% of patients with cancer affecting quality of life and daily living skills. Studies have suggested that genetic makeup, advanced age, fatigue, and premorbid intelligence quotient are risk factors for chemotherapy-associated cognitive decline. Changes in the microstructure of brain white matter, known as brain reserve, have been reported after exposure to chemotherapy, but its link to cognitive decline is understudied. Several studies outside of oncology have used MRI to derive fractional anisotropy as a measure for brain reserve.

In the new JCO study, researchers examined fractional anisotropy, as measured by MRI, before chemotherapy. The analysis included 49 patients who underwent neuropsychological tests before treatment with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, then again at 6 months and 2 years after chemotherapy.

The results were compared with those of patients with breast cancer who did not receive systemic therapy and then with a control group consisting of patients without cancer.

A low fractional anisotropy score suggested cognitive decline more than 3 years after receiving chemotherapy treatment. The finding was independent of age, premorbid intelligence quotient, baseline fatigue and baseline cognitive complaints. And, having low premorbid intelligence quotient was an independent risk factor for chemotherapy-associated cognitive decline, which the authors said is in line with previous findings.

Fractional anisotropy did not predict cognitive decline in patients who did not receive systemic therapy, as well as patients in the control group.

The findings could possibly lead to the development a pretreatment assessment to screen for patients who may at risk for cognitive decline, the authors wrote. “Clinically validated assessments of white-matter reserve as assessed with an MRI scan may be part of a pretreatment screening. This could also aid in early identification of cognitive decline after chemotherapy, allowing targeted and early interventions to improve cognitive problems,” such as psychoeducation and cognitive rehabilitation.

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

“Cognitive decline is frequently observed after chemotherapy,” according to Michiel B. de Ruiter, PhD, a research scientist with the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam. He specializes in cognitive neuroscience and was the lead author of a study published online Sept. 30, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. Dr. de Ruiter and colleagues found that fractional anisotropy may demonstrate a low brain white-matter reserve which could be a risk factor for cognitive decline after chemotherapy for breast cancer treatment.

Cognitive decline after chemotherapy has been reported in 20%-40% of patients with cancer affecting quality of life and daily living skills. Studies have suggested that genetic makeup, advanced age, fatigue, and premorbid intelligence quotient are risk factors for chemotherapy-associated cognitive decline. Changes in the microstructure of brain white matter, known as brain reserve, have been reported after exposure to chemotherapy, but its link to cognitive decline is understudied. Several studies outside of oncology have used MRI to derive fractional anisotropy as a measure for brain reserve.

In the new JCO study, researchers examined fractional anisotropy, as measured by MRI, before chemotherapy. The analysis included 49 patients who underwent neuropsychological tests before treatment with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, then again at 6 months and 2 years after chemotherapy.

The results were compared with those of patients with breast cancer who did not receive systemic therapy and then with a control group consisting of patients without cancer.

A low fractional anisotropy score suggested cognitive decline more than 3 years after receiving chemotherapy treatment. The finding was independent of age, premorbid intelligence quotient, baseline fatigue and baseline cognitive complaints. And, having low premorbid intelligence quotient was an independent risk factor for chemotherapy-associated cognitive decline, which the authors said is in line with previous findings.

Fractional anisotropy did not predict cognitive decline in patients who did not receive systemic therapy, as well as patients in the control group.

The findings could possibly lead to the development a pretreatment assessment to screen for patients who may at risk for cognitive decline, the authors wrote. “Clinically validated assessments of white-matter reserve as assessed with an MRI scan may be part of a pretreatment screening. This could also aid in early identification of cognitive decline after chemotherapy, allowing targeted and early interventions to improve cognitive problems,” such as psychoeducation and cognitive rehabilitation.

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Study points to ideal age for CAC testing in young adults

New risk equations can help determine the need for a first coronary artery calcium (CAC) scan in young adults to identify those most at risk for premature atherosclerosis, researchers say.

“To our knowledge this is the first time to derive a clinical risk equation for the initial conversion from CAC 0, which can be used actually to guide the timing of CAC testing in young adults,” Omar Dzaye, MD, MPH, PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said in an interview.

CAC is an independent predictor of adverse atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), but routine screening is not recommended in low-risk groups. U.S. guidelines say CAC testing may be considered (class IIa) for risk stratification in adults 40 to 75 years at intermediate risk (estimated 10-year ASCVD risk 7.5% to 20%) when the decision to start preventive therapies is unclear.

The new sex-specific risk equations were derived from 22,346 adults 30 to 50 years of age who underwent CAC testing between 1991 and 2010 for ASCVD risk prediction at four high-volume centers in the CAC Consortium. The average age was 43.5 years, 25% were women, and 12.3% were non-White.

The participants were free of clinical ASCVD or CV symptoms at the time of scanning but had underlying traditional ASCVD risk factors (dyslipidemia in 49.6%, hypertension in 20.0%, active smokers 11.0%, and diabetes in 4.0%), an intermediate 10-year ASCVD risk (2.6%), and/or a significant family history of CHD (49.3%).

As reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 92.7% of participants had a low 10-year ASCVD risk below 5%, but 34.4% had CAC scores above 0 (median, 20 Agatston units).

Assuming a 25% testing yield (number needed to scan equals four to detect one CAC score above 0), the optimal age for a first scan in young men without risk factors was 42.3 years, and for women it was 57.6 years.

Young adults with one or more risk factors, however, would convert to CAC above 0 at least 3.3 years earlier on average. Diabetes had the strongest influence on the probability of conversion, with men and women predicted to develop incident CAC a respective 5.5 years and 7.3 years earlier on average.

The findings build on previous observations by the team showing that diabetes confers a 40% reduction in the so-called “warranty period” of a CAC score of 0, Dr. Dzaye noted. The National Lipid Association 2020 statement on CAC scoring also suggests it’s reasonable to obtain a CAC scan in people with diabetes aged 30 to 39 years.

“The predicted utility of CAC for ASCVD outcomes is similar in type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, individuals with type 1 diabetes may actually develop CAC as young as 17 years of age,” he said. “Therefore, definitely, CAC studies in this population are required.”

In contrast, hypertension, dyslipidemia, active smoking, and a family history of CHD were individually associated with the development of CAC 3.3 to 4.3 years earlier. In general, the time to premature CAC was longer for women than for men with a given risk-factor profile.

The predicted age for a first CAC was 37.5 years for men and 48.9 years for women with an intermediate risk-factor profile (for example, smoking plus hypertension) and 33.8 years and 44.7 years, respectively, for those with a high-risk profile (for example, diabetes plus dyslipidemia).

Asked whether the risk equations can be used to guide CAC scanning in clinical practice, Dr. Dzaye said, “we very much believe that this can be used because for the process we published the internal validation, and we also did an external validation that is not published at the moment in [the] MESA [trial].”

He pointed out that study participants did not have a second CAC scan for true modeling of longitudinal CAC and do not represent the general population but, rather, a general cardiology referral population enriched with ASCVD risk factors. Future studies are needed that incorporate a more diverse population, multiple CAC scans, and genetic risk factors.

“This is helpful from a descriptive, epidemiologic point of view and helps us understand the approximate prevalence of coronary calcium greater than 0 in younger men and women, but I’m not convinced that it will or should change clinical practice,” cardiologist Philip Greenland, MD, a professor of preventive medicine and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, said in an interview.

Dr. Greenland, who coauthored a review on CAC testing earlier this month, said CAC is the strongest tool we have to improve risk prediction beyond standard risk scores but does involve radiation exposure and some added costs. CAC testing is especially useful as a tiebreaker in older intermediate-risk patients who may be on the fence about starting primary prevention medications but could fall short among “younger, low-risk patients where, as they show here, the proportion of people who have a positive test is well below half.”

“So that means you’re going to have a very large number of people who are CAC 0, which is what we would expect in relatively younger people, but I wouldn’t be happy to try to explain that to a patient: ‘We’re not seeing coronary atherosclerosis right now, but we still want to treat your risk factors.’ That’s kind of a dissonant message,” Dr. Greenland said.

An accompanying editorial suggests “the study has filled an important clinical gap, providing highly actionable data that could help guide clinical decision making for ASCVD prevention.”

Nevertheless, Tasneem Naqvi, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Tamar Polonsky, MD, University of Chicago, question the generalizability of the results and point out that CAC screening at the authors’ recommended ages “could still miss a substantial number of young women with incident MI.”

Exposure to ionizing radiation with CAC is lower than that used in screening mammography for breast cancer but, they agree, should be considered, particularly in young women.

“Alternatively, ultrasonography avoids radiation altogether and can detect plaque earlier than the development of CAC,” write Dr. Naqvi and Dr. Polonsky. Further, the 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for CV risk give ultrasound assessment of carotid artery and femoral plaque a class IIa recommendation and CAC a class IIb recommendation.

Commenting for this news organization, Roger Blumenthal, MD, director of the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, said the class IIb recommendation “never really made any sense because the data with coronary calcium is so much stronger than it is with carotid ultrasound.”

“Sometimes smart scientists and researchers differ, but in my strong opinion, the European Society of Cardiology in 2019 did not give it the right classification, while the group I was part of, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology [2019 guideline], got it right and emphasized that this is the most cost-effective and useful way to improve risk assessment.”

Dr. Blumenthal, who was not part of the study, noted that U.S. guidelines say CAC measurement is not intended as a screening test for everyone but may be used selectively as a decision aid.

“This study adds to the information about how to use that type of testing. So, I personally think it will be a highly referenced article in the next set of guidelines that the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and other organizations have.”

The study was supported in part by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Dzaye, Dr. Blumenthal, Dr. Naqvi, and Dr. Polonsky report having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New risk equations can help determine the need for a first coronary artery calcium (CAC) scan in young adults to identify those most at risk for premature atherosclerosis, researchers say.

“To our knowledge this is the first time to derive a clinical risk equation for the initial conversion from CAC 0, which can be used actually to guide the timing of CAC testing in young adults,” Omar Dzaye, MD, MPH, PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said in an interview.

CAC is an independent predictor of adverse atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), but routine screening is not recommended in low-risk groups. U.S. guidelines say CAC testing may be considered (class IIa) for risk stratification in adults 40 to 75 years at intermediate risk (estimated 10-year ASCVD risk 7.5% to 20%) when the decision to start preventive therapies is unclear.

The new sex-specific risk equations were derived from 22,346 adults 30 to 50 years of age who underwent CAC testing between 1991 and 2010 for ASCVD risk prediction at four high-volume centers in the CAC Consortium. The average age was 43.5 years, 25% were women, and 12.3% were non-White.

The participants were free of clinical ASCVD or CV symptoms at the time of scanning but had underlying traditional ASCVD risk factors (dyslipidemia in 49.6%, hypertension in 20.0%, active smokers 11.0%, and diabetes in 4.0%), an intermediate 10-year ASCVD risk (2.6%), and/or a significant family history of CHD (49.3%).

As reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 92.7% of participants had a low 10-year ASCVD risk below 5%, but 34.4% had CAC scores above 0 (median, 20 Agatston units).

Assuming a 25% testing yield (number needed to scan equals four to detect one CAC score above 0), the optimal age for a first scan in young men without risk factors was 42.3 years, and for women it was 57.6 years.

Young adults with one or more risk factors, however, would convert to CAC above 0 at least 3.3 years earlier on average. Diabetes had the strongest influence on the probability of conversion, with men and women predicted to develop incident CAC a respective 5.5 years and 7.3 years earlier on average.

The findings build on previous observations by the team showing that diabetes confers a 40% reduction in the so-called “warranty period” of a CAC score of 0, Dr. Dzaye noted. The National Lipid Association 2020 statement on CAC scoring also suggests it’s reasonable to obtain a CAC scan in people with diabetes aged 30 to 39 years.

“The predicted utility of CAC for ASCVD outcomes is similar in type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, individuals with type 1 diabetes may actually develop CAC as young as 17 years of age,” he said. “Therefore, definitely, CAC studies in this population are required.”

In contrast, hypertension, dyslipidemia, active smoking, and a family history of CHD were individually associated with the development of CAC 3.3 to 4.3 years earlier. In general, the time to premature CAC was longer for women than for men with a given risk-factor profile.

The predicted age for a first CAC was 37.5 years for men and 48.9 years for women with an intermediate risk-factor profile (for example, smoking plus hypertension) and 33.8 years and 44.7 years, respectively, for those with a high-risk profile (for example, diabetes plus dyslipidemia).

Asked whether the risk equations can be used to guide CAC scanning in clinical practice, Dr. Dzaye said, “we very much believe that this can be used because for the process we published the internal validation, and we also did an external validation that is not published at the moment in [the] MESA [trial].”

He pointed out that study participants did not have a second CAC scan for true modeling of longitudinal CAC and do not represent the general population but, rather, a general cardiology referral population enriched with ASCVD risk factors. Future studies are needed that incorporate a more diverse population, multiple CAC scans, and genetic risk factors.

“This is helpful from a descriptive, epidemiologic point of view and helps us understand the approximate prevalence of coronary calcium greater than 0 in younger men and women, but I’m not convinced that it will or should change clinical practice,” cardiologist Philip Greenland, MD, a professor of preventive medicine and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, said in an interview.

Dr. Greenland, who coauthored a review on CAC testing earlier this month, said CAC is the strongest tool we have to improve risk prediction beyond standard risk scores but does involve radiation exposure and some added costs. CAC testing is especially useful as a tiebreaker in older intermediate-risk patients who may be on the fence about starting primary prevention medications but could fall short among “younger, low-risk patients where, as they show here, the proportion of people who have a positive test is well below half.”

“So that means you’re going to have a very large number of people who are CAC 0, which is what we would expect in relatively younger people, but I wouldn’t be happy to try to explain that to a patient: ‘We’re not seeing coronary atherosclerosis right now, but we still want to treat your risk factors.’ That’s kind of a dissonant message,” Dr. Greenland said.

An accompanying editorial suggests “the study has filled an important clinical gap, providing highly actionable data that could help guide clinical decision making for ASCVD prevention.”

Nevertheless, Tasneem Naqvi, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Tamar Polonsky, MD, University of Chicago, question the generalizability of the results and point out that CAC screening at the authors’ recommended ages “could still miss a substantial number of young women with incident MI.”

Exposure to ionizing radiation with CAC is lower than that used in screening mammography for breast cancer but, they agree, should be considered, particularly in young women.

“Alternatively, ultrasonography avoids radiation altogether and can detect plaque earlier than the development of CAC,” write Dr. Naqvi and Dr. Polonsky. Further, the 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for CV risk give ultrasound assessment of carotid artery and femoral plaque a class IIa recommendation and CAC a class IIb recommendation.

Commenting for this news organization, Roger Blumenthal, MD, director of the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, said the class IIb recommendation “never really made any sense because the data with coronary calcium is so much stronger than it is with carotid ultrasound.”

“Sometimes smart scientists and researchers differ, but in my strong opinion, the European Society of Cardiology in 2019 did not give it the right classification, while the group I was part of, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology [2019 guideline], got it right and emphasized that this is the most cost-effective and useful way to improve risk assessment.”

Dr. Blumenthal, who was not part of the study, noted that U.S. guidelines say CAC measurement is not intended as a screening test for everyone but may be used selectively as a decision aid.

“This study adds to the information about how to use that type of testing. So, I personally think it will be a highly referenced article in the next set of guidelines that the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and other organizations have.”

The study was supported in part by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Dzaye, Dr. Blumenthal, Dr. Naqvi, and Dr. Polonsky report having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New risk equations can help determine the need for a first coronary artery calcium (CAC) scan in young adults to identify those most at risk for premature atherosclerosis, researchers say.

“To our knowledge this is the first time to derive a clinical risk equation for the initial conversion from CAC 0, which can be used actually to guide the timing of CAC testing in young adults,” Omar Dzaye, MD, MPH, PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said in an interview.

CAC is an independent predictor of adverse atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), but routine screening is not recommended in low-risk groups. U.S. guidelines say CAC testing may be considered (class IIa) for risk stratification in adults 40 to 75 years at intermediate risk (estimated 10-year ASCVD risk 7.5% to 20%) when the decision to start preventive therapies is unclear.

The new sex-specific risk equations were derived from 22,346 adults 30 to 50 years of age who underwent CAC testing between 1991 and 2010 for ASCVD risk prediction at four high-volume centers in the CAC Consortium. The average age was 43.5 years, 25% were women, and 12.3% were non-White.

The participants were free of clinical ASCVD or CV symptoms at the time of scanning but had underlying traditional ASCVD risk factors (dyslipidemia in 49.6%, hypertension in 20.0%, active smokers 11.0%, and diabetes in 4.0%), an intermediate 10-year ASCVD risk (2.6%), and/or a significant family history of CHD (49.3%).

As reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 92.7% of participants had a low 10-year ASCVD risk below 5%, but 34.4% had CAC scores above 0 (median, 20 Agatston units).

Assuming a 25% testing yield (number needed to scan equals four to detect one CAC score above 0), the optimal age for a first scan in young men without risk factors was 42.3 years, and for women it was 57.6 years.

Young adults with one or more risk factors, however, would convert to CAC above 0 at least 3.3 years earlier on average. Diabetes had the strongest influence on the probability of conversion, with men and women predicted to develop incident CAC a respective 5.5 years and 7.3 years earlier on average.

The findings build on previous observations by the team showing that diabetes confers a 40% reduction in the so-called “warranty period” of a CAC score of 0, Dr. Dzaye noted. The National Lipid Association 2020 statement on CAC scoring also suggests it’s reasonable to obtain a CAC scan in people with diabetes aged 30 to 39 years.

“The predicted utility of CAC for ASCVD outcomes is similar in type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, individuals with type 1 diabetes may actually develop CAC as young as 17 years of age,” he said. “Therefore, definitely, CAC studies in this population are required.”

In contrast, hypertension, dyslipidemia, active smoking, and a family history of CHD were individually associated with the development of CAC 3.3 to 4.3 years earlier. In general, the time to premature CAC was longer for women than for men with a given risk-factor profile.

The predicted age for a first CAC was 37.5 years for men and 48.9 years for women with an intermediate risk-factor profile (for example, smoking plus hypertension) and 33.8 years and 44.7 years, respectively, for those with a high-risk profile (for example, diabetes plus dyslipidemia).

Asked whether the risk equations can be used to guide CAC scanning in clinical practice, Dr. Dzaye said, “we very much believe that this can be used because for the process we published the internal validation, and we also did an external validation that is not published at the moment in [the] MESA [trial].”

He pointed out that study participants did not have a second CAC scan for true modeling of longitudinal CAC and do not represent the general population but, rather, a general cardiology referral population enriched with ASCVD risk factors. Future studies are needed that incorporate a more diverse population, multiple CAC scans, and genetic risk factors.

“This is helpful from a descriptive, epidemiologic point of view and helps us understand the approximate prevalence of coronary calcium greater than 0 in younger men and women, but I’m not convinced that it will or should change clinical practice,” cardiologist Philip Greenland, MD, a professor of preventive medicine and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, said in an interview.

Dr. Greenland, who coauthored a review on CAC testing earlier this month, said CAC is the strongest tool we have to improve risk prediction beyond standard risk scores but does involve radiation exposure and some added costs. CAC testing is especially useful as a tiebreaker in older intermediate-risk patients who may be on the fence about starting primary prevention medications but could fall short among “younger, low-risk patients where, as they show here, the proportion of people who have a positive test is well below half.”

“So that means you’re going to have a very large number of people who are CAC 0, which is what we would expect in relatively younger people, but I wouldn’t be happy to try to explain that to a patient: ‘We’re not seeing coronary atherosclerosis right now, but we still want to treat your risk factors.’ That’s kind of a dissonant message,” Dr. Greenland said.

An accompanying editorial suggests “the study has filled an important clinical gap, providing highly actionable data that could help guide clinical decision making for ASCVD prevention.”

Nevertheless, Tasneem Naqvi, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Tamar Polonsky, MD, University of Chicago, question the generalizability of the results and point out that CAC screening at the authors’ recommended ages “could still miss a substantial number of young women with incident MI.”

Exposure to ionizing radiation with CAC is lower than that used in screening mammography for breast cancer but, they agree, should be considered, particularly in young women.

“Alternatively, ultrasonography avoids radiation altogether and can detect plaque earlier than the development of CAC,” write Dr. Naqvi and Dr. Polonsky. Further, the 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for CV risk give ultrasound assessment of carotid artery and femoral plaque a class IIa recommendation and CAC a class IIb recommendation.

Commenting for this news organization, Roger Blumenthal, MD, director of the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, said the class IIb recommendation “never really made any sense because the data with coronary calcium is so much stronger than it is with carotid ultrasound.”

“Sometimes smart scientists and researchers differ, but in my strong opinion, the European Society of Cardiology in 2019 did not give it the right classification, while the group I was part of, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology [2019 guideline], got it right and emphasized that this is the most cost-effective and useful way to improve risk assessment.”

Dr. Blumenthal, who was not part of the study, noted that U.S. guidelines say CAC measurement is not intended as a screening test for everyone but may be used selectively as a decision aid.

“This study adds to the information about how to use that type of testing. So, I personally think it will be a highly referenced article in the next set of guidelines that the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and other organizations have.”

The study was supported in part by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Dzaye, Dr. Blumenthal, Dr. Naqvi, and Dr. Polonsky report having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

POCUS in hospital pediatrics

PHM 2021 Session

Safe and (Ultra)sound: Why you should use POCUS in your Pediatric Practice

Presenter

Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FACP

Session summary

Dr. Ria Dancel and her colleagues from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill presented a broad overview of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) applications in the field of pediatric hospital medicine. They discussed its advantages and potential uses, ranging from common scenarios to critical care to procedural guidance. Using illustrative scenarios and interactive cases, she discussed the bedside applications to improve care of hospitalized children. The benefits and risks of radiography and POCUS were reviewed.

The session highlighted the use of POCUS in SSTI (skin and soft tissue infection) to help with differentiating cellulitis from abscesses. Use of POCUS for safer incision and drainages and making day-to-day changes in management was discussed. The ease and benefits of performing real-time lung ultrasound in different pathologies (like pneumonia, effusion, COVID-19) was presented. The speakers discussed the use of POCUS in emergency situations like hypotension and different types of shock. The use of ultrasound in common bedside procedures (bladder catheterization, lumbar ultrasound, peripheral IV placement) were also highlighted. Current literature and evidence were reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Pediatric POCUS is an extremely valuable bedside tool in pediatric hospital medicine.

- It can be used to guide clinical care for many conditions including SSTI, pneumonia, and shock.

- It can be used for procedural guidance for bladder catheterization, lumbar puncture, and intravenous access.

Dr. Patra is a pediatric hospitalist at West Virginia University Children’s Hospital, Morgantown, and associate professor at West Virginia University School of Medicine. He is interested in medical education, quality improvement and clinical research. He is a member of the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

PHM 2021 Session

Safe and (Ultra)sound: Why you should use POCUS in your Pediatric Practice

Presenter

Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FACP

Session summary

Dr. Ria Dancel and her colleagues from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill presented a broad overview of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) applications in the field of pediatric hospital medicine. They discussed its advantages and potential uses, ranging from common scenarios to critical care to procedural guidance. Using illustrative scenarios and interactive cases, she discussed the bedside applications to improve care of hospitalized children. The benefits and risks of radiography and POCUS were reviewed.

The session highlighted the use of POCUS in SSTI (skin and soft tissue infection) to help with differentiating cellulitis from abscesses. Use of POCUS for safer incision and drainages and making day-to-day changes in management was discussed. The ease and benefits of performing real-time lung ultrasound in different pathologies (like pneumonia, effusion, COVID-19) was presented. The speakers discussed the use of POCUS in emergency situations like hypotension and different types of shock. The use of ultrasound in common bedside procedures (bladder catheterization, lumbar ultrasound, peripheral IV placement) were also highlighted. Current literature and evidence were reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Pediatric POCUS is an extremely valuable bedside tool in pediatric hospital medicine.

- It can be used to guide clinical care for many conditions including SSTI, pneumonia, and shock.

- It can be used for procedural guidance for bladder catheterization, lumbar puncture, and intravenous access.

Dr. Patra is a pediatric hospitalist at West Virginia University Children’s Hospital, Morgantown, and associate professor at West Virginia University School of Medicine. He is interested in medical education, quality improvement and clinical research. He is a member of the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

PHM 2021 Session

Safe and (Ultra)sound: Why you should use POCUS in your Pediatric Practice

Presenter

Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FACP

Session summary

Dr. Ria Dancel and her colleagues from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill presented a broad overview of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) applications in the field of pediatric hospital medicine. They discussed its advantages and potential uses, ranging from common scenarios to critical care to procedural guidance. Using illustrative scenarios and interactive cases, she discussed the bedside applications to improve care of hospitalized children. The benefits and risks of radiography and POCUS were reviewed.

The session highlighted the use of POCUS in SSTI (skin and soft tissue infection) to help with differentiating cellulitis from abscesses. Use of POCUS for safer incision and drainages and making day-to-day changes in management was discussed. The ease and benefits of performing real-time lung ultrasound in different pathologies (like pneumonia, effusion, COVID-19) was presented. The speakers discussed the use of POCUS in emergency situations like hypotension and different types of shock. The use of ultrasound in common bedside procedures (bladder catheterization, lumbar ultrasound, peripheral IV placement) were also highlighted. Current literature and evidence were reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Pediatric POCUS is an extremely valuable bedside tool in pediatric hospital medicine.

- It can be used to guide clinical care for many conditions including SSTI, pneumonia, and shock.

- It can be used for procedural guidance for bladder catheterization, lumbar puncture, and intravenous access.

Dr. Patra is a pediatric hospitalist at West Virginia University Children’s Hospital, Morgantown, and associate professor at West Virginia University School of Medicine. He is interested in medical education, quality improvement and clinical research. He is a member of the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

In all-comer approach, FFR adds no value to angiography: RIPCORD 2

Study confirms selective application

In patients with coronary artery disease scheduled for a percutaneous intervention (PCI), fractional flow reserve (FFR) assessment at the time of angiography significantly improves outcome, but it has no apparent value as a routine study in all CAD patients, according to the randomized RIPCORD 2 trial.

When compared to angiography alone in an all comer-strategy, the addition of FFR did not significantly change management or lower costs, but it was associated with a longer time for diagnostic assessment and more complications, Nicholas P. Curzen, BM, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

As a tool for evaluating stenotic lesions in diseased vessels, FFR, also known as pressure wire assessment, allows interventionalists to target those vessels that induce ischemia without unnecessarily treating vessels with lesions that are hemodynamically nonsignificant. It is guideline recommended for patients with scheduled PCI on the basis of several randomized trials, including the landmark FAME trial.

“The results of these trials were spectacular. The clinical outcomes were significantly better in the FFR group despite less stents being placed and fewer vessels being stented. And there was significantly less resource utilization in the FFR group,” said Dr. Curzen, professor of interventional cardiology, University of Southampton, England.

Hypothesis: All-comers benefit from FFR

This prompted the new trial, called RIPCORD 2. The hypothesis was that systematic FFR early in the diagnosis of CAD would reduce resource utilization and improve quality of life relative to angiography alone. Both were addressed as primary endpoints. A reduction in clinical events at 12 months was a secondary endpoint.

The 1,136 participants, all scheduled for angiographic evaluation for stable angina or non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), were randomized at 17 participating centers in the United Kingdom. All underwent angiography, but the experimental arm also underwent FFR for all arteries of a size suitable for revascularization.

Resource utilization evaluated through hospital costs at 12 months was somewhat higher in the FFR group, but the difference was not significant (P =.137). There was also no significant difference (P = 0.88) between the groups in quality of life, which was measured with EQ-5D-5L, an instrument for expressing five dimensions of health on a visual analog scale.

No impact from FFR on clinical events

Furthermore, there was no difference in the rate of clinical events, whether measured by a composite endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (P = .64) or by the components of death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and unplanned revascularization, according to Dr. Curzen.

Finally, FFR did not appear to influence subsequent management. When the intervention and control groups were compared, the proportions triaged to optimal medical therapy, optimal medical therapy plus PCI, or optimal medical therapy plus bypass grafting did not differ significantly.

Given the lack of significant differences for FFR plus angiography relative to angiography alone for any clinically relevant outcome, the addition of FFR provides "no overall advantage" in this all comer study population, Dr. Curzen concluded.

However, FFR was associated with some relative disadvantages. These included significantly longer mean procedure times (69 vs. 42.4 minutes; P < .001), significantly greater mean use of contrast (206 vs. 146.3 mL; P < .001), and a significantly higher mean radiation dose (6608.7 vs. 5029.7 cGY/cm2; P < .001). There were 10 complications (1.8%) associated with FFR.

RIPCORD 1 results provided study rationale

In the previously published nonrandomized RIPCORD 1 study, interventionalists were asked to develop a management plan on the basis of angiography alone in 200 patients with stable chest pain. When these interventionalists were then provided with FFR results, the new information resulted in a change of management plan in 36% of cases.

According to Dr. Curzen, it was this study that raised all-comer FFR as a “logical and clinically plausible question.” RIPCORD 2 provided the answer.

While he is now conducting an evaluation of a subgroup of RIPCORD 2 patients with more severe disease, “it appears that the atheroma burden on angiography is adequate” to make an appropriate management determination in most or all cases.

The invited discussant for this study, Robert Byrne, MD, BCh, PhD, director of cardiology, Mater Private Hospital, Dublin, pointed out that more angiography-alone patients in RIPCORD 2 required additional evaluation to develop a management strategy (14.7% vs. 1.8%), but he agreed that FFR offered “no reasonable benefit” in the relatively low-risk patients who were enrolled.

Results do not alter FFR indications

However, he emphasized that the lack of an advantage in this trial should in no way diminish the evidence of benefit for selective FFR use as currently recommended in guidelines. This was echoed strongly in remarks by two other interventionalists who served on the same panel after the RIPCORD 2 results were presented.

“I want to make sure that our audience does not walk away thinking that FFR is useless. This is not what was shown,” said Roxana Mehran, MD, director of interventional cardiovascular research at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She emphasized that this was a study that found no value in a low-risk, all-comer population and is not relevant to the populations where it now has an indication.

Marco Roffi, MD, director of the interventional cardiology unit, Geneva University Hospitals, made the same point.

“These results do not take away the value of FFR in a more selected population [than that enrolled in RIPCORD 2],” Dr. Roffi said. He did not rule out the potential for benefit from adding FFR to angiography even in early disease assessment if a benefit can be demonstrated in a higher-risk population.

Dr. Curzen reports financial relationships with Abbott, Beckman Coulter, HeartFlow, and Boston Scientific, which provided funding for RIPCORD 2. Dr. Byrne reported financial relationships with the trial sponsor as well as Abbott, Biosensors, and Biotronik. Dr. Mehran reports financial relationships with more than 15 medical product companies including the sponsor of this trial. Dr. Roffi reports no relevant financial disclosures.

Study confirms selective application

Study confirms selective application

In patients with coronary artery disease scheduled for a percutaneous intervention (PCI), fractional flow reserve (FFR) assessment at the time of angiography significantly improves outcome, but it has no apparent value as a routine study in all CAD patients, according to the randomized RIPCORD 2 trial.

When compared to angiography alone in an all comer-strategy, the addition of FFR did not significantly change management or lower costs, but it was associated with a longer time for diagnostic assessment and more complications, Nicholas P. Curzen, BM, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

As a tool for evaluating stenotic lesions in diseased vessels, FFR, also known as pressure wire assessment, allows interventionalists to target those vessels that induce ischemia without unnecessarily treating vessels with lesions that are hemodynamically nonsignificant. It is guideline recommended for patients with scheduled PCI on the basis of several randomized trials, including the landmark FAME trial.

“The results of these trials were spectacular. The clinical outcomes were significantly better in the FFR group despite less stents being placed and fewer vessels being stented. And there was significantly less resource utilization in the FFR group,” said Dr. Curzen, professor of interventional cardiology, University of Southampton, England.

Hypothesis: All-comers benefit from FFR

This prompted the new trial, called RIPCORD 2. The hypothesis was that systematic FFR early in the diagnosis of CAD would reduce resource utilization and improve quality of life relative to angiography alone. Both were addressed as primary endpoints. A reduction in clinical events at 12 months was a secondary endpoint.

The 1,136 participants, all scheduled for angiographic evaluation for stable angina or non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), were randomized at 17 participating centers in the United Kingdom. All underwent angiography, but the experimental arm also underwent FFR for all arteries of a size suitable for revascularization.

Resource utilization evaluated through hospital costs at 12 months was somewhat higher in the FFR group, but the difference was not significant (P =.137). There was also no significant difference (P = 0.88) between the groups in quality of life, which was measured with EQ-5D-5L, an instrument for expressing five dimensions of health on a visual analog scale.

No impact from FFR on clinical events

Furthermore, there was no difference in the rate of clinical events, whether measured by a composite endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (P = .64) or by the components of death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and unplanned revascularization, according to Dr. Curzen.

Finally, FFR did not appear to influence subsequent management. When the intervention and control groups were compared, the proportions triaged to optimal medical therapy, optimal medical therapy plus PCI, or optimal medical therapy plus bypass grafting did not differ significantly.

Given the lack of significant differences for FFR plus angiography relative to angiography alone for any clinically relevant outcome, the addition of FFR provides "no overall advantage" in this all comer study population, Dr. Curzen concluded.

However, FFR was associated with some relative disadvantages. These included significantly longer mean procedure times (69 vs. 42.4 minutes; P < .001), significantly greater mean use of contrast (206 vs. 146.3 mL; P < .001), and a significantly higher mean radiation dose (6608.7 vs. 5029.7 cGY/cm2; P < .001). There were 10 complications (1.8%) associated with FFR.

RIPCORD 1 results provided study rationale

In the previously published nonrandomized RIPCORD 1 study, interventionalists were asked to develop a management plan on the basis of angiography alone in 200 patients with stable chest pain. When these interventionalists were then provided with FFR results, the new information resulted in a change of management plan in 36% of cases.

According to Dr. Curzen, it was this study that raised all-comer FFR as a “logical and clinically plausible question.” RIPCORD 2 provided the answer.

While he is now conducting an evaluation of a subgroup of RIPCORD 2 patients with more severe disease, “it appears that the atheroma burden on angiography is adequate” to make an appropriate management determination in most or all cases.

The invited discussant for this study, Robert Byrne, MD, BCh, PhD, director of cardiology, Mater Private Hospital, Dublin, pointed out that more angiography-alone patients in RIPCORD 2 required additional evaluation to develop a management strategy (14.7% vs. 1.8%), but he agreed that FFR offered “no reasonable benefit” in the relatively low-risk patients who were enrolled.

Results do not alter FFR indications

However, he emphasized that the lack of an advantage in this trial should in no way diminish the evidence of benefit for selective FFR use as currently recommended in guidelines. This was echoed strongly in remarks by two other interventionalists who served on the same panel after the RIPCORD 2 results were presented.

“I want to make sure that our audience does not walk away thinking that FFR is useless. This is not what was shown,” said Roxana Mehran, MD, director of interventional cardiovascular research at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She emphasized that this was a study that found no value in a low-risk, all-comer population and is not relevant to the populations where it now has an indication.

Marco Roffi, MD, director of the interventional cardiology unit, Geneva University Hospitals, made the same point.

“These results do not take away the value of FFR in a more selected population [than that enrolled in RIPCORD 2],” Dr. Roffi said. He did not rule out the potential for benefit from adding FFR to angiography even in early disease assessment if a benefit can be demonstrated in a higher-risk population.

Dr. Curzen reports financial relationships with Abbott, Beckman Coulter, HeartFlow, and Boston Scientific, which provided funding for RIPCORD 2. Dr. Byrne reported financial relationships with the trial sponsor as well as Abbott, Biosensors, and Biotronik. Dr. Mehran reports financial relationships with more than 15 medical product companies including the sponsor of this trial. Dr. Roffi reports no relevant financial disclosures.

In patients with coronary artery disease scheduled for a percutaneous intervention (PCI), fractional flow reserve (FFR) assessment at the time of angiography significantly improves outcome, but it has no apparent value as a routine study in all CAD patients, according to the randomized RIPCORD 2 trial.

When compared to angiography alone in an all comer-strategy, the addition of FFR did not significantly change management or lower costs, but it was associated with a longer time for diagnostic assessment and more complications, Nicholas P. Curzen, BM, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

As a tool for evaluating stenotic lesions in diseased vessels, FFR, also known as pressure wire assessment, allows interventionalists to target those vessels that induce ischemia without unnecessarily treating vessels with lesions that are hemodynamically nonsignificant. It is guideline recommended for patients with scheduled PCI on the basis of several randomized trials, including the landmark FAME trial.

“The results of these trials were spectacular. The clinical outcomes were significantly better in the FFR group despite less stents being placed and fewer vessels being stented. And there was significantly less resource utilization in the FFR group,” said Dr. Curzen, professor of interventional cardiology, University of Southampton, England.

Hypothesis: All-comers benefit from FFR

This prompted the new trial, called RIPCORD 2. The hypothesis was that systematic FFR early in the diagnosis of CAD would reduce resource utilization and improve quality of life relative to angiography alone. Both were addressed as primary endpoints. A reduction in clinical events at 12 months was a secondary endpoint.

The 1,136 participants, all scheduled for angiographic evaluation for stable angina or non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), were randomized at 17 participating centers in the United Kingdom. All underwent angiography, but the experimental arm also underwent FFR for all arteries of a size suitable for revascularization.

Resource utilization evaluated through hospital costs at 12 months was somewhat higher in the FFR group, but the difference was not significant (P =.137). There was also no significant difference (P = 0.88) between the groups in quality of life, which was measured with EQ-5D-5L, an instrument for expressing five dimensions of health on a visual analog scale.

No impact from FFR on clinical events

Furthermore, there was no difference in the rate of clinical events, whether measured by a composite endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (P = .64) or by the components of death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and unplanned revascularization, according to Dr. Curzen.

Finally, FFR did not appear to influence subsequent management. When the intervention and control groups were compared, the proportions triaged to optimal medical therapy, optimal medical therapy plus PCI, or optimal medical therapy plus bypass grafting did not differ significantly.

Given the lack of significant differences for FFR plus angiography relative to angiography alone for any clinically relevant outcome, the addition of FFR provides "no overall advantage" in this all comer study population, Dr. Curzen concluded.

However, FFR was associated with some relative disadvantages. These included significantly longer mean procedure times (69 vs. 42.4 minutes; P < .001), significantly greater mean use of contrast (206 vs. 146.3 mL; P < .001), and a significantly higher mean radiation dose (6608.7 vs. 5029.7 cGY/cm2; P < .001). There were 10 complications (1.8%) associated with FFR.

RIPCORD 1 results provided study rationale

In the previously published nonrandomized RIPCORD 1 study, interventionalists were asked to develop a management plan on the basis of angiography alone in 200 patients with stable chest pain. When these interventionalists were then provided with FFR results, the new information resulted in a change of management plan in 36% of cases.

According to Dr. Curzen, it was this study that raised all-comer FFR as a “logical and clinically plausible question.” RIPCORD 2 provided the answer.

While he is now conducting an evaluation of a subgroup of RIPCORD 2 patients with more severe disease, “it appears that the atheroma burden on angiography is adequate” to make an appropriate management determination in most or all cases.

The invited discussant for this study, Robert Byrne, MD, BCh, PhD, director of cardiology, Mater Private Hospital, Dublin, pointed out that more angiography-alone patients in RIPCORD 2 required additional evaluation to develop a management strategy (14.7% vs. 1.8%), but he agreed that FFR offered “no reasonable benefit” in the relatively low-risk patients who were enrolled.

Results do not alter FFR indications

However, he emphasized that the lack of an advantage in this trial should in no way diminish the evidence of benefit for selective FFR use as currently recommended in guidelines. This was echoed strongly in remarks by two other interventionalists who served on the same panel after the RIPCORD 2 results were presented.

“I want to make sure that our audience does not walk away thinking that FFR is useless. This is not what was shown,” said Roxana Mehran, MD, director of interventional cardiovascular research at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She emphasized that this was a study that found no value in a low-risk, all-comer population and is not relevant to the populations where it now has an indication.

Marco Roffi, MD, director of the interventional cardiology unit, Geneva University Hospitals, made the same point.

“These results do not take away the value of FFR in a more selected population [than that enrolled in RIPCORD 2],” Dr. Roffi said. He did not rule out the potential for benefit from adding FFR to angiography even in early disease assessment if a benefit can be demonstrated in a higher-risk population.

Dr. Curzen reports financial relationships with Abbott, Beckman Coulter, HeartFlow, and Boston Scientific, which provided funding for RIPCORD 2. Dr. Byrne reported financial relationships with the trial sponsor as well as Abbott, Biosensors, and Biotronik. Dr. Mehran reports financial relationships with more than 15 medical product companies including the sponsor of this trial. Dr. Roffi reports no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2021

Use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for heart failure

Case

A 65-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with a chief complaint of shortness of breath for 3 days. Medical history is notable for moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, systolic heart failure with last known ejection fraction (EF) of 35% and type 2 diabetes complicated by hyperglycemia when on steroids. You are talking the case over with colleagues and they suggest point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) would be useful in her case.

Brief overview of the issue

Once mainly used by ED and critical care physicians, POCUS is now a tool that many hospitalists are using at the bedside. POCUS differs from traditional comprehensive ultrasounds in the following ways: POCUS is designed to answer a specific clinical question (as opposed to evaluating all organs in a specific region), POCUS exams are performed by the clinician who is formulating the clinical question (as opposed to by a consultative service such as cardiology and radiology), and POCUS can evaluate multiple organ systems (such as by evaluating a patient’s heart, lungs, and inferior vena cava to determine the etiology of hypoxia).