User login

Double-dose influenza vaccine effective against type B strains

A double-dose inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine (IIV4) could be administered to all children aged 6-35 months, as it not only offers the best protection against influenza type B, but it also allows for simplifying the current vaccination schedule considerably.

“The introduction of IIV4 provides an opportunity to review long-accepted practices in administration of influenza vaccines,” explained Varsha K. Jain, MD, formerly employed by GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, King of Prussia, Pa., and associates.

Giving a lower dose to young children was planned to reduce reactogenicity and febrile convulsions observed with the whole virus vaccines that were in use in the 1970s. But young children have a variable immune response to lower doses, especially against vaccine B strains, they noted (J Ped Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 6. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw068).

Dr. Jain and coauthors enrolled 2,430 children aged 6-35 months during the 2014-2015 influenza season in the United States and Mexico in this phase III study. Children were randomized into one of two cohorts: one cohort received a standard-doze IIV4 vaccination, while the other received a double-dose. Data on age (6-17 months, 18-35 months), health care center, and influenza primer status also were taken into consideration.

The standard-dose vaccine contained 7.5 mcg of A/California/7/2009 (A/H1N1), A/Texas/50/2012 (A/H3N2), B/Brisbane/60/2008 (B/Victoria), and B/Massachusetts/2/2012 (B/Yamagata), while the double-dose vaccine contained 15 mcg, or twice the amount each, of the same strains. The former was developed by Sanofi Pasteur and the latter by GSK Vaccines.

Primed children who completed the study numbered 1,173; 586 received the standard-dose and 587 received the double-dose. On the unprimed side, 868 completed the study: 442 standard-dose and 426 double-dose. Each dose’s immunogenic noninferiority was quantified by calculating the geometric mean titer (GMT) ratio.

“Immunogenicity was higher in the double-dose group compared with the standard-dose group, particularly against vaccine B strains in children 6-17 months of age and unprimed children,” Dr. Vain and associates said. Both vaccines performed well against the influenza B strain, with the double-dose yielding a GMT of 1.89 against the B/Yamagata strain and 2.13 against the B/Victoria in children aged 6-17 months. Across the entire age spectrum of the study population, unprimed children registered a GMT of 1.85 and 2.04 against the same strains, respectively. For comparison, none of the A strains in any cohort based on age or primed/unprimed registered a GMT above 1.5.

“Increased protection against influenza B [would] be a beneficial clinical outcome [and] use of the same vaccine dose for all eligible ages would also simplify the annual influenza vaccine campaign and reduce cost and logistic complexity,” the authors concluded. “This study provides evidence to support a change in clinical practice to use [double-dose IIV4] in all children 6 months of age and older, once that dosing for a vaccine product has been approved.”

Dr. Jain now is employed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Dr. Jain and several coauthors disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline, which funded the study.

A double-dose inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine (IIV4) could be administered to all children aged 6-35 months, as it not only offers the best protection against influenza type B, but it also allows for simplifying the current vaccination schedule considerably.

“The introduction of IIV4 provides an opportunity to review long-accepted practices in administration of influenza vaccines,” explained Varsha K. Jain, MD, formerly employed by GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, King of Prussia, Pa., and associates.

Giving a lower dose to young children was planned to reduce reactogenicity and febrile convulsions observed with the whole virus vaccines that were in use in the 1970s. But young children have a variable immune response to lower doses, especially against vaccine B strains, they noted (J Ped Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 6. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw068).

Dr. Jain and coauthors enrolled 2,430 children aged 6-35 months during the 2014-2015 influenza season in the United States and Mexico in this phase III study. Children were randomized into one of two cohorts: one cohort received a standard-doze IIV4 vaccination, while the other received a double-dose. Data on age (6-17 months, 18-35 months), health care center, and influenza primer status also were taken into consideration.

The standard-dose vaccine contained 7.5 mcg of A/California/7/2009 (A/H1N1), A/Texas/50/2012 (A/H3N2), B/Brisbane/60/2008 (B/Victoria), and B/Massachusetts/2/2012 (B/Yamagata), while the double-dose vaccine contained 15 mcg, or twice the amount each, of the same strains. The former was developed by Sanofi Pasteur and the latter by GSK Vaccines.

Primed children who completed the study numbered 1,173; 586 received the standard-dose and 587 received the double-dose. On the unprimed side, 868 completed the study: 442 standard-dose and 426 double-dose. Each dose’s immunogenic noninferiority was quantified by calculating the geometric mean titer (GMT) ratio.

“Immunogenicity was higher in the double-dose group compared with the standard-dose group, particularly against vaccine B strains in children 6-17 months of age and unprimed children,” Dr. Vain and associates said. Both vaccines performed well against the influenza B strain, with the double-dose yielding a GMT of 1.89 against the B/Yamagata strain and 2.13 against the B/Victoria in children aged 6-17 months. Across the entire age spectrum of the study population, unprimed children registered a GMT of 1.85 and 2.04 against the same strains, respectively. For comparison, none of the A strains in any cohort based on age or primed/unprimed registered a GMT above 1.5.

“Increased protection against influenza B [would] be a beneficial clinical outcome [and] use of the same vaccine dose for all eligible ages would also simplify the annual influenza vaccine campaign and reduce cost and logistic complexity,” the authors concluded. “This study provides evidence to support a change in clinical practice to use [double-dose IIV4] in all children 6 months of age and older, once that dosing for a vaccine product has been approved.”

Dr. Jain now is employed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Dr. Jain and several coauthors disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline, which funded the study.

A double-dose inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine (IIV4) could be administered to all children aged 6-35 months, as it not only offers the best protection against influenza type B, but it also allows for simplifying the current vaccination schedule considerably.

“The introduction of IIV4 provides an opportunity to review long-accepted practices in administration of influenza vaccines,” explained Varsha K. Jain, MD, formerly employed by GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, King of Prussia, Pa., and associates.

Giving a lower dose to young children was planned to reduce reactogenicity and febrile convulsions observed with the whole virus vaccines that were in use in the 1970s. But young children have a variable immune response to lower doses, especially against vaccine B strains, they noted (J Ped Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 6. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw068).

Dr. Jain and coauthors enrolled 2,430 children aged 6-35 months during the 2014-2015 influenza season in the United States and Mexico in this phase III study. Children were randomized into one of two cohorts: one cohort received a standard-doze IIV4 vaccination, while the other received a double-dose. Data on age (6-17 months, 18-35 months), health care center, and influenza primer status also were taken into consideration.

The standard-dose vaccine contained 7.5 mcg of A/California/7/2009 (A/H1N1), A/Texas/50/2012 (A/H3N2), B/Brisbane/60/2008 (B/Victoria), and B/Massachusetts/2/2012 (B/Yamagata), while the double-dose vaccine contained 15 mcg, or twice the amount each, of the same strains. The former was developed by Sanofi Pasteur and the latter by GSK Vaccines.

Primed children who completed the study numbered 1,173; 586 received the standard-dose and 587 received the double-dose. On the unprimed side, 868 completed the study: 442 standard-dose and 426 double-dose. Each dose’s immunogenic noninferiority was quantified by calculating the geometric mean titer (GMT) ratio.

“Immunogenicity was higher in the double-dose group compared with the standard-dose group, particularly against vaccine B strains in children 6-17 months of age and unprimed children,” Dr. Vain and associates said. Both vaccines performed well against the influenza B strain, with the double-dose yielding a GMT of 1.89 against the B/Yamagata strain and 2.13 against the B/Victoria in children aged 6-17 months. Across the entire age spectrum of the study population, unprimed children registered a GMT of 1.85 and 2.04 against the same strains, respectively. For comparison, none of the A strains in any cohort based on age or primed/unprimed registered a GMT above 1.5.

“Increased protection against influenza B [would] be a beneficial clinical outcome [and] use of the same vaccine dose for all eligible ages would also simplify the annual influenza vaccine campaign and reduce cost and logistic complexity,” the authors concluded. “This study provides evidence to support a change in clinical practice to use [double-dose IIV4] in all children 6 months of age and older, once that dosing for a vaccine product has been approved.”

Dr. Jain now is employed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Dr. Jain and several coauthors disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline, which funded the study.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SOCIETY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Geometric mean titer (GMT) ratios showed that the double-dose IIV4 vaccine was the most effective against influenza type B in children aged 6-17 months (GMT = 1.89) and in unprimed children aged 6-35 months (GMT = 1.85).

Data source: Phase III, randomized trial of 2,041 children aged 6-35 months.

Disclosures: Dr. Jain and several coauthors disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline, which funded the study.

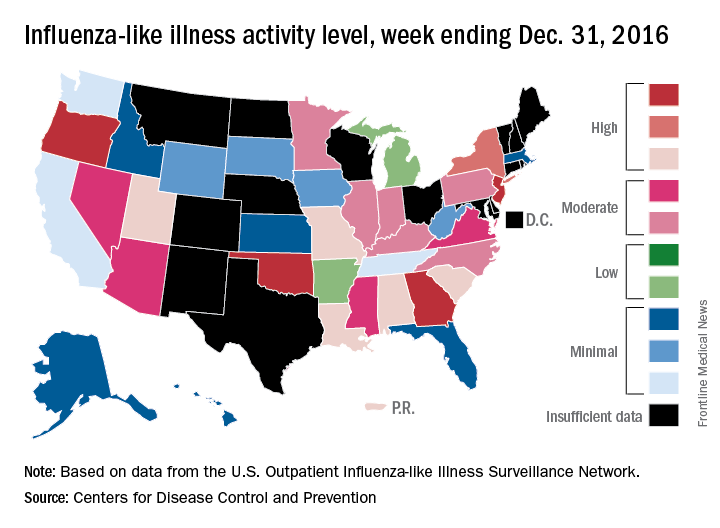

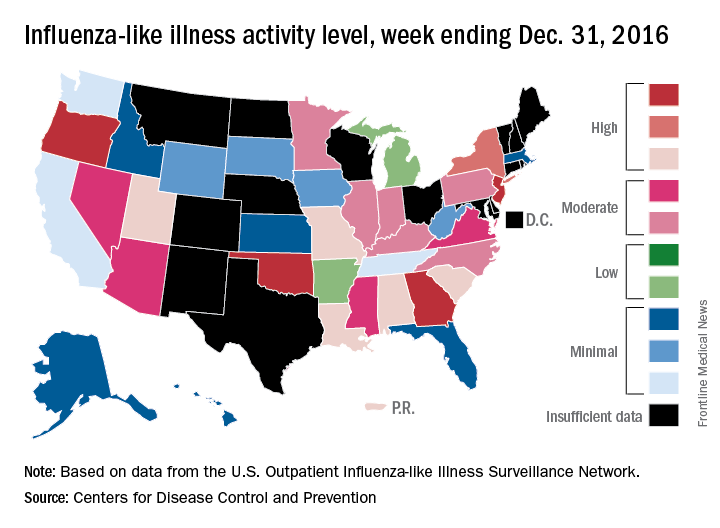

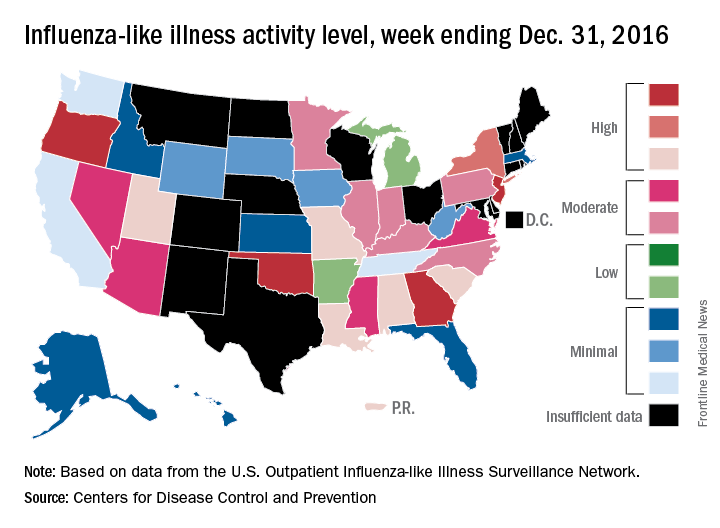

High levels of flu activity in 10 U.S. states

The 2016-2017 flu season shifted into high gear at the end of calendar year 2016, as four states were reported to be at the highest level of flu activity and six others were close behind, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Dec. 31, 2016, Georgia, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Oregon were at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI). Others in the “high” range were New York at level 9 and Alabama, Louisiana, Missouri, South Carolina, and Utah at level 8. Puerto Rico was also at level 8, after being at level 10 for the previous few weeks. An additional 10 states were in the “moderate” range (6-7), the CDC reported.

The CDC has not reported any flu-related pediatric deaths yet this season. Pediatric death totals for each of the last 3 years were 111 for 2013-2014, 148 for 2014-2015, and 89 for 2015-2016, the CDC said.

The 2016-2017 flu season shifted into high gear at the end of calendar year 2016, as four states were reported to be at the highest level of flu activity and six others were close behind, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Dec. 31, 2016, Georgia, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Oregon were at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI). Others in the “high” range were New York at level 9 and Alabama, Louisiana, Missouri, South Carolina, and Utah at level 8. Puerto Rico was also at level 8, after being at level 10 for the previous few weeks. An additional 10 states were in the “moderate” range (6-7), the CDC reported.

The CDC has not reported any flu-related pediatric deaths yet this season. Pediatric death totals for each of the last 3 years were 111 for 2013-2014, 148 for 2014-2015, and 89 for 2015-2016, the CDC said.

The 2016-2017 flu season shifted into high gear at the end of calendar year 2016, as four states were reported to be at the highest level of flu activity and six others were close behind, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Dec. 31, 2016, Georgia, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Oregon were at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI). Others in the “high” range were New York at level 9 and Alabama, Louisiana, Missouri, South Carolina, and Utah at level 8. Puerto Rico was also at level 8, after being at level 10 for the previous few weeks. An additional 10 states were in the “moderate” range (6-7), the CDC reported.

The CDC has not reported any flu-related pediatric deaths yet this season. Pediatric death totals for each of the last 3 years were 111 for 2013-2014, 148 for 2014-2015, and 89 for 2015-2016, the CDC said.

Autism risk not increased by maternal influenza infection during pregnancy

Maternal influenza infection during pregnancy does not increase the risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children, according to Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, and associates.

In a study of 196,929 mother-child pairs (the children were born at Kaiser Permanente Northern California between Jan. 1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2010), 1.6% of the children were diagnosed with ASD. Influenza was diagnosed in 0.7% of mothers during their pregnancy, and 23% received an influenza vaccination during pregnancy.

Overall, maternal influenza vaccination did not effect likelihood of ASD diagnosis, with 1.7% of children in this group receiving an ASD diagnosis. A small association between ASD diagnosis and maternal influenza vaccination, however, was seen in the first trimester of pregnancy, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.2, translating to a potential extra 4 cases of autism per 1,000 births. But further analysis suggested that this could be caused by bias and chance, and “the association was insignificant after statistical correction for multiple comparisons,” the investigators said.

“While we do not advocate changes in vaccine policy or practice, we believe that additional studies are warranted to further evaluate any potential associations between first-trimester maternal influenza vaccination and autism,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3609).

Maternal influenza infection during pregnancy does not increase the risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children, according to Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, and associates.

In a study of 196,929 mother-child pairs (the children were born at Kaiser Permanente Northern California between Jan. 1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2010), 1.6% of the children were diagnosed with ASD. Influenza was diagnosed in 0.7% of mothers during their pregnancy, and 23% received an influenza vaccination during pregnancy.

Overall, maternal influenza vaccination did not effect likelihood of ASD diagnosis, with 1.7% of children in this group receiving an ASD diagnosis. A small association between ASD diagnosis and maternal influenza vaccination, however, was seen in the first trimester of pregnancy, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.2, translating to a potential extra 4 cases of autism per 1,000 births. But further analysis suggested that this could be caused by bias and chance, and “the association was insignificant after statistical correction for multiple comparisons,” the investigators said.

“While we do not advocate changes in vaccine policy or practice, we believe that additional studies are warranted to further evaluate any potential associations between first-trimester maternal influenza vaccination and autism,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3609).

Maternal influenza infection during pregnancy does not increase the risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children, according to Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, and associates.

In a study of 196,929 mother-child pairs (the children were born at Kaiser Permanente Northern California between Jan. 1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2010), 1.6% of the children were diagnosed with ASD. Influenza was diagnosed in 0.7% of mothers during their pregnancy, and 23% received an influenza vaccination during pregnancy.

Overall, maternal influenza vaccination did not effect likelihood of ASD diagnosis, with 1.7% of children in this group receiving an ASD diagnosis. A small association between ASD diagnosis and maternal influenza vaccination, however, was seen in the first trimester of pregnancy, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.2, translating to a potential extra 4 cases of autism per 1,000 births. But further analysis suggested that this could be caused by bias and chance, and “the association was insignificant after statistical correction for multiple comparisons,” the investigators said.

“While we do not advocate changes in vaccine policy or practice, we believe that additional studies are warranted to further evaluate any potential associations between first-trimester maternal influenza vaccination and autism,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in JAMA Pediatrics (doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3609).

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Phase II data suggest IV zanamivir safe for severe flu in kids

NEW ORLEANS – The investigational intravenous formulation of the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir appears to be a safe influenza treatment for hospitalized children and adolescents at high risk of complications who can’t tolerate enteral therapy, according to findings from an open-label, multicenter, phase II study.

In 71 such patients with laboratory-confirmed flu, who presented within 7 days of illness onset and who received intravenous zanamivir (IVZ) for 5-10 days, 72% experienced adverse events (AEs), 21% experienced serious adverse events, and 5 deaths occurred, but none were considered by the investigators to be attributable to IVZ, Jeffrey Blumer, MD, reported at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Rather, the adverse events were “fairly diverse. ... the kinds of things normally seen in critically ill pediatric populations,” he said.

The patients, who had a mean age of 7 years, were treated with IVZ doses selected to provide exposures comparable to 600 mg in adults – a dosage shown in prior studies to be safe and well-tolerated in adults. Patients aged 6 months to under age 6 years received twice-daily doses of 14 mg/kg, and those aged 6 years to less than 18 years received twice-daily doses of 12 mg/kg, not to exceed 600 mg. Doses were adjusted for renal function.

Patients were enrolled from five countries, and most (69%) had received prior treatment with oseltamivir. More than half (56%) had chronic medical conditions.

The median time from symptom onset to IVZ treatment was 4 days, Dr. Blumer of the University of Toledo (Ohio) said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Infiltrate on chest x-ray was seen in 59% of patients, mechanical ventilation was required in 34% of patients, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was required in 6% of patients. Treatment in the intensive care unit was required in 65% of patients, and cumulative mortality was 4% at 14 days, and 7% at 28 days.

“Overall, the [IVZ] exposure and then the elimination profiles were consistent across the entire age cohort – unusual for most drugs, but it seemed to hold true, which makes zanamivir a lot easier for us to work with in pediatrics,” Dr. Blumer said.

While the numbers are small, exposure and response delineation didn’t seem to be impacted by mechanical ventilation, by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or by continuous renal replacement therapy, which is a good sign, he noted.

“So we generally had good, consistent experience here. ... Overall, 64 of the 71 patients survived, got better, left the ICU, and left the hospital,” Dr. Blumer said.

Of note, a treatment-emergent resistance substitution, E119G, was detected in a day 5 H1N1 isolate from an immunocompetent patient who improved clinically while on IVZ, he said, adding that no phenotype data were available as the sample could not be cultured.

The findings are important, because while zanamivir is currently labeled for patients older than 7 years, and the intravenous formulation currently in development has been shown to be safe for adults, there is a critical unmet need for an effective parenteral treatment for severe flu in children at high risk of complications who cannot tolerate enteral therapy.

“We need a drug that is available for the critically ill. We need a drug available for kids who are unable to take oral therapy, and for treatment of oseltamivir-resistant strains,” he said, adding that the current findings suggest that IVZ – with dose selection based on age, weight, and renal function – is a suitable treatment option for such patients.

“In conclusion, what we saw in this open-label trial was that the dose selection that we utilized gave us the kind of exposure we’d expect, and it seems it was an appropriate way to approach pediatric patients,” he said. “There wasn’t any safety signal attributable to the drug, and the overall pattern was more that of serious influenza, rather than of drug exposure.”

Dr. Blumer reported receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, which sponsored the study.

NEW ORLEANS – The investigational intravenous formulation of the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir appears to be a safe influenza treatment for hospitalized children and adolescents at high risk of complications who can’t tolerate enteral therapy, according to findings from an open-label, multicenter, phase II study.

In 71 such patients with laboratory-confirmed flu, who presented within 7 days of illness onset and who received intravenous zanamivir (IVZ) for 5-10 days, 72% experienced adverse events (AEs), 21% experienced serious adverse events, and 5 deaths occurred, but none were considered by the investigators to be attributable to IVZ, Jeffrey Blumer, MD, reported at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Rather, the adverse events were “fairly diverse. ... the kinds of things normally seen in critically ill pediatric populations,” he said.

The patients, who had a mean age of 7 years, were treated with IVZ doses selected to provide exposures comparable to 600 mg in adults – a dosage shown in prior studies to be safe and well-tolerated in adults. Patients aged 6 months to under age 6 years received twice-daily doses of 14 mg/kg, and those aged 6 years to less than 18 years received twice-daily doses of 12 mg/kg, not to exceed 600 mg. Doses were adjusted for renal function.

Patients were enrolled from five countries, and most (69%) had received prior treatment with oseltamivir. More than half (56%) had chronic medical conditions.

The median time from symptom onset to IVZ treatment was 4 days, Dr. Blumer of the University of Toledo (Ohio) said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Infiltrate on chest x-ray was seen in 59% of patients, mechanical ventilation was required in 34% of patients, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was required in 6% of patients. Treatment in the intensive care unit was required in 65% of patients, and cumulative mortality was 4% at 14 days, and 7% at 28 days.

“Overall, the [IVZ] exposure and then the elimination profiles were consistent across the entire age cohort – unusual for most drugs, but it seemed to hold true, which makes zanamivir a lot easier for us to work with in pediatrics,” Dr. Blumer said.

While the numbers are small, exposure and response delineation didn’t seem to be impacted by mechanical ventilation, by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or by continuous renal replacement therapy, which is a good sign, he noted.

“So we generally had good, consistent experience here. ... Overall, 64 of the 71 patients survived, got better, left the ICU, and left the hospital,” Dr. Blumer said.

Of note, a treatment-emergent resistance substitution, E119G, was detected in a day 5 H1N1 isolate from an immunocompetent patient who improved clinically while on IVZ, he said, adding that no phenotype data were available as the sample could not be cultured.

The findings are important, because while zanamivir is currently labeled for patients older than 7 years, and the intravenous formulation currently in development has been shown to be safe for adults, there is a critical unmet need for an effective parenteral treatment for severe flu in children at high risk of complications who cannot tolerate enteral therapy.

“We need a drug that is available for the critically ill. We need a drug available for kids who are unable to take oral therapy, and for treatment of oseltamivir-resistant strains,” he said, adding that the current findings suggest that IVZ – with dose selection based on age, weight, and renal function – is a suitable treatment option for such patients.

“In conclusion, what we saw in this open-label trial was that the dose selection that we utilized gave us the kind of exposure we’d expect, and it seems it was an appropriate way to approach pediatric patients,” he said. “There wasn’t any safety signal attributable to the drug, and the overall pattern was more that of serious influenza, rather than of drug exposure.”

Dr. Blumer reported receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, which sponsored the study.

NEW ORLEANS – The investigational intravenous formulation of the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir appears to be a safe influenza treatment for hospitalized children and adolescents at high risk of complications who can’t tolerate enteral therapy, according to findings from an open-label, multicenter, phase II study.

In 71 such patients with laboratory-confirmed flu, who presented within 7 days of illness onset and who received intravenous zanamivir (IVZ) for 5-10 days, 72% experienced adverse events (AEs), 21% experienced serious adverse events, and 5 deaths occurred, but none were considered by the investigators to be attributable to IVZ, Jeffrey Blumer, MD, reported at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Rather, the adverse events were “fairly diverse. ... the kinds of things normally seen in critically ill pediatric populations,” he said.

The patients, who had a mean age of 7 years, were treated with IVZ doses selected to provide exposures comparable to 600 mg in adults – a dosage shown in prior studies to be safe and well-tolerated in adults. Patients aged 6 months to under age 6 years received twice-daily doses of 14 mg/kg, and those aged 6 years to less than 18 years received twice-daily doses of 12 mg/kg, not to exceed 600 mg. Doses were adjusted for renal function.

Patients were enrolled from five countries, and most (69%) had received prior treatment with oseltamivir. More than half (56%) had chronic medical conditions.

The median time from symptom onset to IVZ treatment was 4 days, Dr. Blumer of the University of Toledo (Ohio) said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Infiltrate on chest x-ray was seen in 59% of patients, mechanical ventilation was required in 34% of patients, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was required in 6% of patients. Treatment in the intensive care unit was required in 65% of patients, and cumulative mortality was 4% at 14 days, and 7% at 28 days.

“Overall, the [IVZ] exposure and then the elimination profiles were consistent across the entire age cohort – unusual for most drugs, but it seemed to hold true, which makes zanamivir a lot easier for us to work with in pediatrics,” Dr. Blumer said.

While the numbers are small, exposure and response delineation didn’t seem to be impacted by mechanical ventilation, by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or by continuous renal replacement therapy, which is a good sign, he noted.

“So we generally had good, consistent experience here. ... Overall, 64 of the 71 patients survived, got better, left the ICU, and left the hospital,” Dr. Blumer said.

Of note, a treatment-emergent resistance substitution, E119G, was detected in a day 5 H1N1 isolate from an immunocompetent patient who improved clinically while on IVZ, he said, adding that no phenotype data were available as the sample could not be cultured.

The findings are important, because while zanamivir is currently labeled for patients older than 7 years, and the intravenous formulation currently in development has been shown to be safe for adults, there is a critical unmet need for an effective parenteral treatment for severe flu in children at high risk of complications who cannot tolerate enteral therapy.

“We need a drug that is available for the critically ill. We need a drug available for kids who are unable to take oral therapy, and for treatment of oseltamivir-resistant strains,” he said, adding that the current findings suggest that IVZ – with dose selection based on age, weight, and renal function – is a suitable treatment option for such patients.

“In conclusion, what we saw in this open-label trial was that the dose selection that we utilized gave us the kind of exposure we’d expect, and it seems it was an appropriate way to approach pediatric patients,” he said. “There wasn’t any safety signal attributable to the drug, and the overall pattern was more that of serious influenza, rather than of drug exposure.”

Dr. Blumer reported receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, which sponsored the study.

AT ID WEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 72% of patients experienced adverse events and 21% experienced serious adverse events, but none were considered by the investigators to be attributable to intravenous zanamivir.

Data source: An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of 71 children with laboratory-confirmed influenza.

Disclosures: Dr. Blumer reported receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, which sponsored the study.

Flu susceptibility driven by birth year

Differences in susceptibility to an influenza A virus (IAV) strain may be traceable to the first lifetime influenza infection, according to a new statistical model, which could have implications for epidemiology and future flu vaccines.

In the Nov. 11 issue of Science, researchers described infection models of the H5N1 and H7N9 strains of influenza A. The former occurs more commonly in younger people, and the latter in older individuals, but the reasons for those associations have puzzled scientists.

The researchers, led by James Lloyd-Smith, PhD, of the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Los Angeles, looked at susceptibility to IAV strains by birth year, and found that this was the best predictor of vulnerability. For example, an analysis of H5N1 cases in Egypt, where had many H5N1 cases spread over the past decade, showed that individuals born in the same year had the same average risk of severe H5N1 infection, even after they had aged by 10 years. That suggests that it is the birth year, not advancing age, which influences susceptibility (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:721-5. doi:10.1126/science.aag1322).

The researchers suggest that the immune system “imprints” on the hemagglutinin (HA) subtype during an individual’s first infection, which confers protection against severe disease caused by other, related viruses, though it may not reduce infection rates overall.

The year 1968 may have marked an important inflection point. That year marked a shift in the identify of circulating viruses, from group 1 HA (which includes H5N1) to group 2 HA (which includes H7N9). Individuals born before 1968 were likely first infected with a group 1 virus, while those born later were most likely initially exposed to a group 2 virus. If the imprint theory is correct, younger people would have imprinted on group 2 viruses similar to H7N9, which would explain their greater vulnerability to group 1 viruses like H5N1.

“Imprinting was the dominant explanatory factor for observed incidence and mortality patterns for both H5N1 and H7N9. It was the only tested factor included in all plausible models for both viruses,” the researchers wrote.

According to the model, imprinting explains 75% of protection against severe infection and 80% of the protection against mortality for H5N1 and H7N9.

That information adds a previously unrecognized layer to influenza epidemiology, which should be accounted for in public health measures. “The methods shown here can provide rolling estimates of which age groups would be at highest risk for severe disease should particular novel HA subtypes emerge,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security. They reported having no financial disclosures.

A growing body of epidemiological evidence points to the prolonged effects of cross-immunity, including competition between strains during seasonal and pandemic outbreaks, reduced risk of pandemic infection in those with previous seasonal exposure, and – as reported by Gostic et al. – lifelong protection against viruses of different subtypes but in the same hemagglutinin (HA) homology group. Basic science efforts are now needed to fully validate the HA imprinting hypothesis. More broadly, further experimental and theoretical work should map the relationship between early childhood exposure to influenza and immune protection and the implications of lifelong immunity for vaccination strategies and pandemic risk.

Cécile Viboud, PhD, is the acting director of the division of international epidemiology and population studies at the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health. Suzanne L. Epstein, PhD, is the associate director for research at the office of tissues and advanced therapies at the Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. They had no relevant financial disclosures and made these remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:706-7. doi:10.1126/science.aak9816).

A growing body of epidemiological evidence points to the prolonged effects of cross-immunity, including competition between strains during seasonal and pandemic outbreaks, reduced risk of pandemic infection in those with previous seasonal exposure, and – as reported by Gostic et al. – lifelong protection against viruses of different subtypes but in the same hemagglutinin (HA) homology group. Basic science efforts are now needed to fully validate the HA imprinting hypothesis. More broadly, further experimental and theoretical work should map the relationship between early childhood exposure to influenza and immune protection and the implications of lifelong immunity for vaccination strategies and pandemic risk.

Cécile Viboud, PhD, is the acting director of the division of international epidemiology and population studies at the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health. Suzanne L. Epstein, PhD, is the associate director for research at the office of tissues and advanced therapies at the Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. They had no relevant financial disclosures and made these remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:706-7. doi:10.1126/science.aak9816).

A growing body of epidemiological evidence points to the prolonged effects of cross-immunity, including competition between strains during seasonal and pandemic outbreaks, reduced risk of pandemic infection in those with previous seasonal exposure, and – as reported by Gostic et al. – lifelong protection against viruses of different subtypes but in the same hemagglutinin (HA) homology group. Basic science efforts are now needed to fully validate the HA imprinting hypothesis. More broadly, further experimental and theoretical work should map the relationship between early childhood exposure to influenza and immune protection and the implications of lifelong immunity for vaccination strategies and pandemic risk.

Cécile Viboud, PhD, is the acting director of the division of international epidemiology and population studies at the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health. Suzanne L. Epstein, PhD, is the associate director for research at the office of tissues and advanced therapies at the Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. They had no relevant financial disclosures and made these remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:706-7. doi:10.1126/science.aak9816).

Differences in susceptibility to an influenza A virus (IAV) strain may be traceable to the first lifetime influenza infection, according to a new statistical model, which could have implications for epidemiology and future flu vaccines.

In the Nov. 11 issue of Science, researchers described infection models of the H5N1 and H7N9 strains of influenza A. The former occurs more commonly in younger people, and the latter in older individuals, but the reasons for those associations have puzzled scientists.

The researchers, led by James Lloyd-Smith, PhD, of the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Los Angeles, looked at susceptibility to IAV strains by birth year, and found that this was the best predictor of vulnerability. For example, an analysis of H5N1 cases in Egypt, where had many H5N1 cases spread over the past decade, showed that individuals born in the same year had the same average risk of severe H5N1 infection, even after they had aged by 10 years. That suggests that it is the birth year, not advancing age, which influences susceptibility (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:721-5. doi:10.1126/science.aag1322).

The researchers suggest that the immune system “imprints” on the hemagglutinin (HA) subtype during an individual’s first infection, which confers protection against severe disease caused by other, related viruses, though it may not reduce infection rates overall.

The year 1968 may have marked an important inflection point. That year marked a shift in the identify of circulating viruses, from group 1 HA (which includes H5N1) to group 2 HA (which includes H7N9). Individuals born before 1968 were likely first infected with a group 1 virus, while those born later were most likely initially exposed to a group 2 virus. If the imprint theory is correct, younger people would have imprinted on group 2 viruses similar to H7N9, which would explain their greater vulnerability to group 1 viruses like H5N1.

“Imprinting was the dominant explanatory factor for observed incidence and mortality patterns for both H5N1 and H7N9. It was the only tested factor included in all plausible models for both viruses,” the researchers wrote.

According to the model, imprinting explains 75% of protection against severe infection and 80% of the protection against mortality for H5N1 and H7N9.

That information adds a previously unrecognized layer to influenza epidemiology, which should be accounted for in public health measures. “The methods shown here can provide rolling estimates of which age groups would be at highest risk for severe disease should particular novel HA subtypes emerge,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security. They reported having no financial disclosures.

Differences in susceptibility to an influenza A virus (IAV) strain may be traceable to the first lifetime influenza infection, according to a new statistical model, which could have implications for epidemiology and future flu vaccines.

In the Nov. 11 issue of Science, researchers described infection models of the H5N1 and H7N9 strains of influenza A. The former occurs more commonly in younger people, and the latter in older individuals, but the reasons for those associations have puzzled scientists.

The researchers, led by James Lloyd-Smith, PhD, of the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Los Angeles, looked at susceptibility to IAV strains by birth year, and found that this was the best predictor of vulnerability. For example, an analysis of H5N1 cases in Egypt, where had many H5N1 cases spread over the past decade, showed that individuals born in the same year had the same average risk of severe H5N1 infection, even after they had aged by 10 years. That suggests that it is the birth year, not advancing age, which influences susceptibility (Science. 2016 Nov 11;354[6313]:721-5. doi:10.1126/science.aag1322).

The researchers suggest that the immune system “imprints” on the hemagglutinin (HA) subtype during an individual’s first infection, which confers protection against severe disease caused by other, related viruses, though it may not reduce infection rates overall.

The year 1968 may have marked an important inflection point. That year marked a shift in the identify of circulating viruses, from group 1 HA (which includes H5N1) to group 2 HA (which includes H7N9). Individuals born before 1968 were likely first infected with a group 1 virus, while those born later were most likely initially exposed to a group 2 virus. If the imprint theory is correct, younger people would have imprinted on group 2 viruses similar to H7N9, which would explain their greater vulnerability to group 1 viruses like H5N1.

“Imprinting was the dominant explanatory factor for observed incidence and mortality patterns for both H5N1 and H7N9. It was the only tested factor included in all plausible models for both viruses,” the researchers wrote.

According to the model, imprinting explains 75% of protection against severe infection and 80% of the protection against mortality for H5N1 and H7N9.

That information adds a previously unrecognized layer to influenza epidemiology, which should be accounted for in public health measures. “The methods shown here can provide rolling estimates of which age groups would be at highest risk for severe disease should particular novel HA subtypes emerge,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security. They reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Early exposure to virus subtype explains 75% of protection against severe disease in later life.

Data source: Statistical model of retrospective data.

Disclosures: The researchers received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security. They reported having no financial disclosures.

Absolute humidity most important environmental factor in global influenza

Absolute humidity and temperature are the most important environmental drivers of global influenza, despite differences in outbreak patterns between tropical and temperate countries, according to a new analysis by U.S.-based researchers.

Using convergent cross-mapping and an empirical dynamic modeling approach on data collected by the World Health Organization, investigators led by George Sugihara, PhD, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, confirmed a hypothetical U-shaped relationship between influenza outbreaks and absolute humidity. At low latitudes in the tropics, absolute humidity has a positive effect, increasing the likelihood of influenza as humidity rises but at higher latitudes in temperate countries, absolute humidity has a negative effect, making influenza more likely when absolute humidity is low.

While absolute humidity was the most important factor in the likelihood of influenza outbreaks, the U-shaped relationship was dictated by average temperature. An average temperature below 70 °F had little effect on the negative relationship between absolute humidity and influenza at that range of temperatures, but if the temperature was between 75 °F and 85 °F, the effect was positive. Above 85 °F, aerosol transmission of influenza is blocked, the investigators noted.

“Augmented with further laboratory testing, these population-level results could help set the stage for public health initiatives such as placing humidifiers in schools and hospitals during cold, dry, temperate winter, and in the tropics, perhaps using dehumidifiers or air conditioners set above 75 °F to dry air in public buildings,” Dr. Sugihara and his colleagues wrote.

Find the full study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607747113).

Absolute humidity and temperature are the most important environmental drivers of global influenza, despite differences in outbreak patterns between tropical and temperate countries, according to a new analysis by U.S.-based researchers.

Using convergent cross-mapping and an empirical dynamic modeling approach on data collected by the World Health Organization, investigators led by George Sugihara, PhD, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, confirmed a hypothetical U-shaped relationship between influenza outbreaks and absolute humidity. At low latitudes in the tropics, absolute humidity has a positive effect, increasing the likelihood of influenza as humidity rises but at higher latitudes in temperate countries, absolute humidity has a negative effect, making influenza more likely when absolute humidity is low.

While absolute humidity was the most important factor in the likelihood of influenza outbreaks, the U-shaped relationship was dictated by average temperature. An average temperature below 70 °F had little effect on the negative relationship between absolute humidity and influenza at that range of temperatures, but if the temperature was between 75 °F and 85 °F, the effect was positive. Above 85 °F, aerosol transmission of influenza is blocked, the investigators noted.

“Augmented with further laboratory testing, these population-level results could help set the stage for public health initiatives such as placing humidifiers in schools and hospitals during cold, dry, temperate winter, and in the tropics, perhaps using dehumidifiers or air conditioners set above 75 °F to dry air in public buildings,” Dr. Sugihara and his colleagues wrote.

Find the full study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607747113).

Absolute humidity and temperature are the most important environmental drivers of global influenza, despite differences in outbreak patterns between tropical and temperate countries, according to a new analysis by U.S.-based researchers.

Using convergent cross-mapping and an empirical dynamic modeling approach on data collected by the World Health Organization, investigators led by George Sugihara, PhD, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, confirmed a hypothetical U-shaped relationship between influenza outbreaks and absolute humidity. At low latitudes in the tropics, absolute humidity has a positive effect, increasing the likelihood of influenza as humidity rises but at higher latitudes in temperate countries, absolute humidity has a negative effect, making influenza more likely when absolute humidity is low.

While absolute humidity was the most important factor in the likelihood of influenza outbreaks, the U-shaped relationship was dictated by average temperature. An average temperature below 70 °F had little effect on the negative relationship between absolute humidity and influenza at that range of temperatures, but if the temperature was between 75 °F and 85 °F, the effect was positive. Above 85 °F, aerosol transmission of influenza is blocked, the investigators noted.

“Augmented with further laboratory testing, these population-level results could help set the stage for public health initiatives such as placing humidifiers in schools and hospitals during cold, dry, temperate winter, and in the tropics, perhaps using dehumidifiers or air conditioners set above 75 °F to dry air in public buildings,” Dr. Sugihara and his colleagues wrote.

Find the full study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607747113).

2014-2015 influenza vaccine ineffective against predominant strain

The 2014-2015 influenza vaccines offered little protection against the predominant influenza A/H3N2 virus, but were effective against influenza B, according to the vaccine effectiveness estimates provided by the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

Preferential use of the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) among young children, a recommendation previously published by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, was not supported.

During the 2014-2015 influenza season, a total of 9,710 patients seeking outpatient medical treatment for acute respiratory infection with cough were enrolled into the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness study, reported Richard Zimmerman, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Oct 4. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw635).

Of these, 9,311 participants had complete data, and 7,078 (76%) tested negative for influenza. A total of 1,840 participants tested positive for influenza A – 99% of these cases were strain A/H3N2 – and 395 participants tested positive for influenza B.

Of the 4,360 vaccinated participants with known vaccine type, 39.7% received standard dose trivalent, 1.6% received high dose trivalent, 46.8% received standard dose quadrivalent, and 11.9% received quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccines.

For influenza A and B combined, the overall adjusted vaccine effectiveness was 19% (95% Confidence Interval, 10-27%) against all medically attended influenza and was statistically significant in all age groups except 18-49 years.

Across all vaccine types, the vaccine effectiveness for the A/H3N2 strain was 6% (95% CI, -5-17%), estimates were similar across all age groups, and all vaccine types were similarly ineffective. These estimates were “consistent with a mismatch between the vaccine and circulating viruses,” the researchers noted.

Overall vaccine effectiveness for influenza B/Yamagata was 55% (95% CI, 43% to 65%) and was similarly significant in all age strata except 50-64 year olds. Trivalent vaccines were more effective at preventing influenza B and, of note, no cases of influenza B occurred among those who received a high dose trivalent flu vaccine.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zimmerman and four other investigators reported receiving research funding from several pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

The 2014-2015 influenza vaccines offered little protection against the predominant influenza A/H3N2 virus, but were effective against influenza B, according to the vaccine effectiveness estimates provided by the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

Preferential use of the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) among young children, a recommendation previously published by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, was not supported.

During the 2014-2015 influenza season, a total of 9,710 patients seeking outpatient medical treatment for acute respiratory infection with cough were enrolled into the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness study, reported Richard Zimmerman, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Oct 4. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw635).

Of these, 9,311 participants had complete data, and 7,078 (76%) tested negative for influenza. A total of 1,840 participants tested positive for influenza A – 99% of these cases were strain A/H3N2 – and 395 participants tested positive for influenza B.

Of the 4,360 vaccinated participants with known vaccine type, 39.7% received standard dose trivalent, 1.6% received high dose trivalent, 46.8% received standard dose quadrivalent, and 11.9% received quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccines.

For influenza A and B combined, the overall adjusted vaccine effectiveness was 19% (95% Confidence Interval, 10-27%) against all medically attended influenza and was statistically significant in all age groups except 18-49 years.

Across all vaccine types, the vaccine effectiveness for the A/H3N2 strain was 6% (95% CI, -5-17%), estimates were similar across all age groups, and all vaccine types were similarly ineffective. These estimates were “consistent with a mismatch between the vaccine and circulating viruses,” the researchers noted.

Overall vaccine effectiveness for influenza B/Yamagata was 55% (95% CI, 43% to 65%) and was similarly significant in all age strata except 50-64 year olds. Trivalent vaccines were more effective at preventing influenza B and, of note, no cases of influenza B occurred among those who received a high dose trivalent flu vaccine.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zimmerman and four other investigators reported receiving research funding from several pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

The 2014-2015 influenza vaccines offered little protection against the predominant influenza A/H3N2 virus, but were effective against influenza B, according to the vaccine effectiveness estimates provided by the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

Preferential use of the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) among young children, a recommendation previously published by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, was not supported.

During the 2014-2015 influenza season, a total of 9,710 patients seeking outpatient medical treatment for acute respiratory infection with cough were enrolled into the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness study, reported Richard Zimmerman, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and his colleagues (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Oct 4. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw635).

Of these, 9,311 participants had complete data, and 7,078 (76%) tested negative for influenza. A total of 1,840 participants tested positive for influenza A – 99% of these cases were strain A/H3N2 – and 395 participants tested positive for influenza B.

Of the 4,360 vaccinated participants with known vaccine type, 39.7% received standard dose trivalent, 1.6% received high dose trivalent, 46.8% received standard dose quadrivalent, and 11.9% received quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccines.

For influenza A and B combined, the overall adjusted vaccine effectiveness was 19% (95% Confidence Interval, 10-27%) against all medically attended influenza and was statistically significant in all age groups except 18-49 years.

Across all vaccine types, the vaccine effectiveness for the A/H3N2 strain was 6% (95% CI, -5-17%), estimates were similar across all age groups, and all vaccine types were similarly ineffective. These estimates were “consistent with a mismatch between the vaccine and circulating viruses,” the researchers noted.

Overall vaccine effectiveness for influenza B/Yamagata was 55% (95% CI, 43% to 65%) and was similarly significant in all age strata except 50-64 year olds. Trivalent vaccines were more effective at preventing influenza B and, of note, no cases of influenza B occurred among those who received a high dose trivalent flu vaccine.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zimmerman and four other investigators reported receiving research funding from several pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Across all vaccine types, the vaccine effectiveness for the A/H3N2 strain was 6%.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 9,710 patients who sought outpatient medical treatment during the 2014-2015 influenza season.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zimmerman and four other investigators reported receiving research funding from several pharmaceutical companies.

Procalcitonin helps ID pneumonia patients needing intubation

Procalcitonin can help predict which patients with community-acquired pneumonia may require intubation for respiratory failure during a hospital admission.

Compared to those with undetectable levels, patients with a procalcitonin of 5 ng/mL were three times more likely to require invasive respiratory support, and those with a 10 ng/mL level were five times more likely, reported Wesley Self, MD, and his colleagues (Chest. 2016;150[4]:819-28. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.04.010).

While predictive accuracy isn’t good enough to merit use of procalcitonin as a stand-alone test, adding it to existing clinical management tools “is likely to improve identification of patients needing intensive care,” wrote Dr. Self of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, and his colleagues. “An elevated procalcitonin level may help identify these patients without overt clinical signs of impending respiratory failure or shock but who would benefit from early [intensive care unit] admission.”

The team examined serum procalcitonin as a biomarker in a subgroup of patients included in the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study of adults hospitalized with community-acquire pneumonia. The primary outcome was the need for invasive respiratory and/or vasopressor support (IRVS) within 72 hours.

Secondarily, they looked at whether adding procalcitonin boosted the performance of accepted pneumonia risk scores, including the American Thoracic Society minor criteria (ATS).

The cohort comprised 1,770 patients with a median age of 57 years. Of these, 115 (6.5%) needed IRVS within 72 hours of admission. Almost 16% were admitted directly into an intensive care unit; almost 7% experienced a delayed transfer from a medical unit into an ICU. The in-hospital mortality was about 2%.

Most (1,642) had an ATS score of less than 3; among these, about 5% needed IRVS. The remainder had a score of 3 or higher; about 30% required IRVS. All had procalcitonin levels pulled at admission. The levels were significantly higher among patients who required IRVS than those who didn’t (1.43 ng/mL vs. 0.14 ng/mL).

A multivariate analysis found that procalcitonin was strongly associated with the risk of IRVS. In patients with undetectable levels, the risk was 4%. At 5-10 ng/mL, the overall risk of IRVS was about 14%. Every 1-ng/mL increase in this range boosted the risk of IRVS by 1%-2%.

Adding the measurement of procalcitonin to traditional pneumonia severity risk scores significantly improved the patients’ performance. When stratified by ATS minor criteria, the risk of IRVS was 4.7% among low-risk patients. That decreased to 2.4% with the addition of undetectable procalcitonin, and increased to 12% with the addition of a 10 ng/mL level.

Conversely, without considering procalcitonin, ATS high-risk patients had almost a 30% risk of IRVS. Among these high-risk patients, IRVS risk dropped to 13% with undetectable procalcitonin and increased to 36% with high procalcitonin.

Adding the biomarker level to the ATS system improved its ability to correctly classify patients, the team said. “Using at least 3 ATS minor criteria alone to indicate high risk, 77 (4.4%) of the 1,770 total patients were misclassified as low-risk and experienced IRVS. Including procalcitonin of at least 0.83 ng/ml in addition … as a high-risk indicator reduced the number of patients with IRVS misclassified as low risk to 44 (2.5%). Adding procalcitonin of at least 0.83 ng/mL as a high-risk indicator resulted in 370 additional patients being classified as high risk, with 33 correctly classified as having IRVS.”

Dr. Self reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

While measuring procalcitonin adds valuable information to pneumonia risk stratification schemes, this process lacks the accuracy needed to enable the diagnosis of pneumonia as a stand-alone test, Daiana Stolz, MD, MPH, FCCP, wrote in an editorial.

“This study further supports the notion that procalcitonin has a limited prognostic accuracy as a stand-alone test. It also does not seem to outperform the risk estimation of a combination of clinical and laboratorial parameters. However, it also emphasizes its potential to capture nuances elusive to the clinical assessment, which do not seem to be consistently reflected even in elaborated severity scores recommended for clinical routine use,” she said (Chest. 2016;150[4]:769-71. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.017).

[Procalcitonin] values vary according to the pneumonia severity and this association is stronger than the one between disease severity and other clinical and laboratory variables,” she said.

Risk scores like the ATS system can be weak, “in particular with regard to positive predictive values,” Dr. Stolz wrote. And this is an important issue. “It is clear that patients fulfilling major criteria (endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation; shock-requiring vasopressors) should be considered for ICU admission; however, there is still controversy about the value of the minor criteria. ICU care is costly and a limited resource worldwide.”

She called for “a randomized study evaluating the outcome and cost-effectiveness of a procalcitonin-refined clinical score in severe [community acquired pneumonia].”

Dr. Stolz is a pulmonologist at the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland. She reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

While measuring procalcitonin adds valuable information to pneumonia risk stratification schemes, this process lacks the accuracy needed to enable the diagnosis of pneumonia as a stand-alone test, Daiana Stolz, MD, MPH, FCCP, wrote in an editorial.

“This study further supports the notion that procalcitonin has a limited prognostic accuracy as a stand-alone test. It also does not seem to outperform the risk estimation of a combination of clinical and laboratorial parameters. However, it also emphasizes its potential to capture nuances elusive to the clinical assessment, which do not seem to be consistently reflected even in elaborated severity scores recommended for clinical routine use,” she said (Chest. 2016;150[4]:769-71. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.017).

[Procalcitonin] values vary according to the pneumonia severity and this association is stronger than the one between disease severity and other clinical and laboratory variables,” she said.

Risk scores like the ATS system can be weak, “in particular with regard to positive predictive values,” Dr. Stolz wrote. And this is an important issue. “It is clear that patients fulfilling major criteria (endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation; shock-requiring vasopressors) should be considered for ICU admission; however, there is still controversy about the value of the minor criteria. ICU care is costly and a limited resource worldwide.”

She called for “a randomized study evaluating the outcome and cost-effectiveness of a procalcitonin-refined clinical score in severe [community acquired pneumonia].”

Dr. Stolz is a pulmonologist at the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland. She reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

While measuring procalcitonin adds valuable information to pneumonia risk stratification schemes, this process lacks the accuracy needed to enable the diagnosis of pneumonia as a stand-alone test, Daiana Stolz, MD, MPH, FCCP, wrote in an editorial.

“This study further supports the notion that procalcitonin has a limited prognostic accuracy as a stand-alone test. It also does not seem to outperform the risk estimation of a combination of clinical and laboratorial parameters. However, it also emphasizes its potential to capture nuances elusive to the clinical assessment, which do not seem to be consistently reflected even in elaborated severity scores recommended for clinical routine use,” she said (Chest. 2016;150[4]:769-71. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.017).

[Procalcitonin] values vary according to the pneumonia severity and this association is stronger than the one between disease severity and other clinical and laboratory variables,” she said.

Risk scores like the ATS system can be weak, “in particular with regard to positive predictive values,” Dr. Stolz wrote. And this is an important issue. “It is clear that patients fulfilling major criteria (endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation; shock-requiring vasopressors) should be considered for ICU admission; however, there is still controversy about the value of the minor criteria. ICU care is costly and a limited resource worldwide.”

She called for “a randomized study evaluating the outcome and cost-effectiveness of a procalcitonin-refined clinical score in severe [community acquired pneumonia].”

Dr. Stolz is a pulmonologist at the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland. She reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

Procalcitonin can help predict which patients with community-acquired pneumonia may require intubation for respiratory failure during a hospital admission.

Compared to those with undetectable levels, patients with a procalcitonin of 5 ng/mL were three times more likely to require invasive respiratory support, and those with a 10 ng/mL level were five times more likely, reported Wesley Self, MD, and his colleagues (Chest. 2016;150[4]:819-28. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.04.010).

While predictive accuracy isn’t good enough to merit use of procalcitonin as a stand-alone test, adding it to existing clinical management tools “is likely to improve identification of patients needing intensive care,” wrote Dr. Self of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, and his colleagues. “An elevated procalcitonin level may help identify these patients without overt clinical signs of impending respiratory failure or shock but who would benefit from early [intensive care unit] admission.”

The team examined serum procalcitonin as a biomarker in a subgroup of patients included in the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study of adults hospitalized with community-acquire pneumonia. The primary outcome was the need for invasive respiratory and/or vasopressor support (IRVS) within 72 hours.

Secondarily, they looked at whether adding procalcitonin boosted the performance of accepted pneumonia risk scores, including the American Thoracic Society minor criteria (ATS).

The cohort comprised 1,770 patients with a median age of 57 years. Of these, 115 (6.5%) needed IRVS within 72 hours of admission. Almost 16% were admitted directly into an intensive care unit; almost 7% experienced a delayed transfer from a medical unit into an ICU. The in-hospital mortality was about 2%.

Most (1,642) had an ATS score of less than 3; among these, about 5% needed IRVS. The remainder had a score of 3 or higher; about 30% required IRVS. All had procalcitonin levels pulled at admission. The levels were significantly higher among patients who required IRVS than those who didn’t (1.43 ng/mL vs. 0.14 ng/mL).

A multivariate analysis found that procalcitonin was strongly associated with the risk of IRVS. In patients with undetectable levels, the risk was 4%. At 5-10 ng/mL, the overall risk of IRVS was about 14%. Every 1-ng/mL increase in this range boosted the risk of IRVS by 1%-2%.

Adding the measurement of procalcitonin to traditional pneumonia severity risk scores significantly improved the patients’ performance. When stratified by ATS minor criteria, the risk of IRVS was 4.7% among low-risk patients. That decreased to 2.4% with the addition of undetectable procalcitonin, and increased to 12% with the addition of a 10 ng/mL level.

Conversely, without considering procalcitonin, ATS high-risk patients had almost a 30% risk of IRVS. Among these high-risk patients, IRVS risk dropped to 13% with undetectable procalcitonin and increased to 36% with high procalcitonin.

Adding the biomarker level to the ATS system improved its ability to correctly classify patients, the team said. “Using at least 3 ATS minor criteria alone to indicate high risk, 77 (4.4%) of the 1,770 total patients were misclassified as low-risk and experienced IRVS. Including procalcitonin of at least 0.83 ng/ml in addition … as a high-risk indicator reduced the number of patients with IRVS misclassified as low risk to 44 (2.5%). Adding procalcitonin of at least 0.83 ng/mL as a high-risk indicator resulted in 370 additional patients being classified as high risk, with 33 correctly classified as having IRVS.”

Dr. Self reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Procalcitonin can help predict which patients with community-acquired pneumonia may require intubation for respiratory failure during a hospital admission.

Compared to those with undetectable levels, patients with a procalcitonin of 5 ng/mL were three times more likely to require invasive respiratory support, and those with a 10 ng/mL level were five times more likely, reported Wesley Self, MD, and his colleagues (Chest. 2016;150[4]:819-28. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.04.010).

While predictive accuracy isn’t good enough to merit use of procalcitonin as a stand-alone test, adding it to existing clinical management tools “is likely to improve identification of patients needing intensive care,” wrote Dr. Self of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, and his colleagues. “An elevated procalcitonin level may help identify these patients without overt clinical signs of impending respiratory failure or shock but who would benefit from early [intensive care unit] admission.”

The team examined serum procalcitonin as a biomarker in a subgroup of patients included in the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study of adults hospitalized with community-acquire pneumonia. The primary outcome was the need for invasive respiratory and/or vasopressor support (IRVS) within 72 hours.

Secondarily, they looked at whether adding procalcitonin boosted the performance of accepted pneumonia risk scores, including the American Thoracic Society minor criteria (ATS).

The cohort comprised 1,770 patients with a median age of 57 years. Of these, 115 (6.5%) needed IRVS within 72 hours of admission. Almost 16% were admitted directly into an intensive care unit; almost 7% experienced a delayed transfer from a medical unit into an ICU. The in-hospital mortality was about 2%.

Most (1,642) had an ATS score of less than 3; among these, about 5% needed IRVS. The remainder had a score of 3 or higher; about 30% required IRVS. All had procalcitonin levels pulled at admission. The levels were significantly higher among patients who required IRVS than those who didn’t (1.43 ng/mL vs. 0.14 ng/mL).

A multivariate analysis found that procalcitonin was strongly associated with the risk of IRVS. In patients with undetectable levels, the risk was 4%. At 5-10 ng/mL, the overall risk of IRVS was about 14%. Every 1-ng/mL increase in this range boosted the risk of IRVS by 1%-2%.

Adding the measurement of procalcitonin to traditional pneumonia severity risk scores significantly improved the patients’ performance. When stratified by ATS minor criteria, the risk of IRVS was 4.7% among low-risk patients. That decreased to 2.4% with the addition of undetectable procalcitonin, and increased to 12% with the addition of a 10 ng/mL level.

Conversely, without considering procalcitonin, ATS high-risk patients had almost a 30% risk of IRVS. Among these high-risk patients, IRVS risk dropped to 13% with undetectable procalcitonin and increased to 36% with high procalcitonin.

Adding the biomarker level to the ATS system improved its ability to correctly classify patients, the team said. “Using at least 3 ATS minor criteria alone to indicate high risk, 77 (4.4%) of the 1,770 total patients were misclassified as low-risk and experienced IRVS. Including procalcitonin of at least 0.83 ng/ml in addition … as a high-risk indicator reduced the number of patients with IRVS misclassified as low risk to 44 (2.5%). Adding procalcitonin of at least 0.83 ng/mL as a high-risk indicator resulted in 370 additional patients being classified as high risk, with 33 correctly classified as having IRVS.”

Dr. Self reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At a procalcitonin level of 5-10 ng/mL, the overall risk of invasive respiratory and/or vasopressor support was about 14%.

Data source: The analysis comprised 1,770 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Self reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

Influenza vaccine highly beneficial for people with type 2 diabetes

Individuals with type 2 diabetes should receive the seasonal influenza vaccines annually, as doing so significantly mitigates their chances of being hospitalized for – or dying from – cardiovascular complications such as stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction.

“Studies assessing influenza vaccine effectiveness in people with diabetes are scarce and have shown inconclusive results,” wrote Eszter P. Vamos, MD, PhD, of Imperial College London and her coauthors in a study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. “None of the previous studies adjusted for residual confounding, and most of them reported composite endpoints such as admission to hospital for any cause.”

Each year included was divided into four seasons: preinfluenza season (Sept. 1 through the date of influenza season starting); influenza season (date of season onset as defined by national surveillance data through 4 weeks after the determined date of season ending); postinfluenza season (from the end of influenza season through April 30); and summer season (May 1 through Aug. 31). The primary outcomes were defined as hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, pneumonia or influenza, and all-cause death, comparing between those who received their seasonal influenza vaccines and those who did not.

Following adjustment to account for any possible residual confounding, individuals who received their influenza vaccines were found to have a 19% reduction in their rate of hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction (incidence rate ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.62-1.04), a 30% reduction in admissions for stroke (IRR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53-0.91), a 22% reduction in admissions for heart failure (IRR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.65-0.92), a 15% reduction in admissions for either pneumonia or influenza (IRR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.74-0.99), and a 24% lower death rate than those who had not been vaccinated (IRR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.65-0.83).

“Our study provides valuable information on the long-term average benefits of influenza vaccine in people with type 2 diabetes,” the authors concluded, adding that “These findings underline the importance of influenza vaccination as part of comprehensive secondary prevention in this high-risk population.”

The study was supported by National Institute of Health Research. Dr. Vamos and her coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Individuals with type 2 diabetes should receive the seasonal influenza vaccines annually, as doing so significantly mitigates their chances of being hospitalized for – or dying from – cardiovascular complications such as stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction.

“Studies assessing influenza vaccine effectiveness in people with diabetes are scarce and have shown inconclusive results,” wrote Eszter P. Vamos, MD, PhD, of Imperial College London and her coauthors in a study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. “None of the previous studies adjusted for residual confounding, and most of them reported composite endpoints such as admission to hospital for any cause.”

Each year included was divided into four seasons: preinfluenza season (Sept. 1 through the date of influenza season starting); influenza season (date of season onset as defined by national surveillance data through 4 weeks after the determined date of season ending); postinfluenza season (from the end of influenza season through April 30); and summer season (May 1 through Aug. 31). The primary outcomes were defined as hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, pneumonia or influenza, and all-cause death, comparing between those who received their seasonal influenza vaccines and those who did not.

Following adjustment to account for any possible residual confounding, individuals who received their influenza vaccines were found to have a 19% reduction in their rate of hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction (incidence rate ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.62-1.04), a 30% reduction in admissions for stroke (IRR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53-0.91), a 22% reduction in admissions for heart failure (IRR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.65-0.92), a 15% reduction in admissions for either pneumonia or influenza (IRR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.74-0.99), and a 24% lower death rate than those who had not been vaccinated (IRR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.65-0.83).