User login

The Vampire Study, pathogenic puppies, and carbonated cannabis

What the duck?

Turns out it’s flu shot season for our feathered friends, too. After the bird flu pandemics that began in 2013, Chinese health officials worked hard to vaccinate their chickens and quell the spread of the disease. However, the ducks have outsmarted them: Two new genetic variations of the H7N9 and H7N2 flu subtypes have been found in unvaccinated ducks.

China consumes about 3 billion ducks per year, so officials are working rapidly to eliminate the virus. At press time, there was no word on whether the virus had affected any beloved rubber duckies, but we advise you to use caution when approaching bath time.

Toke-a-Cola

Cannabis is the world’s favorite illicit drug. And Coca-Cola makes the world’s favorite cola. Now there’s news of potential nuptials uniting these two global giants. BNN Bloomberg reports that Coke is talking tie-up with Canada’s Aurora Cannabis in a union that could give birth to cannabis-infused “wellness beverages.”

The fizzy federation would feature products containing cannabidiol, or CBD. Unlike its wilder psychoactive sibling tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the more sober-minded CBD is a nonpsychoactive cannabis compound credited with antidepressant, anxiolytic, and anti-inflammatory powers.

And what of Coca-Cola’s mortal cola enemy, Pepsi? Will the Choice of a New Generation let the Real Thing Bogart all the possible market opportunities? Sure, you could soon have a CBD Coke and a smile. But smiles are free. Frito-Lay’s parent, PepsiCo, could offer consumers a doubly profitable, Jeff Spicoli–approved pairing: carbonated cannabinoids and Cheetos.

I vant to suck MY blood

It’s not Halloween quite yet, but get into the spirit with the recently published and aptly named “Vampire Study.” Performed in Zürich, a team of researchers from the division of gastroenterology at Triemli Hospital convinced participants to ingest their own blood, all in the name of science.

Some lucky vamps drank their blood, while others ingested it via nasogastric tube. This isn’t “Saw 17,” though; there was a method to this madness. Researchers were investigating whether the ingestion of blood (as in gastrointestinal bleeding) can result in an increase in fecal calprotectin. Safe to say, though, the ingestion of blood is rarely a good sign – unless your name happens to be Nosferatu.

And they call it Campylobacter love

As any fan of Charles Schulz’s “Peanuts” comic strip can tell you, happiness is a warm puppy. Know what else warm puppies are? Carriers of Campylobacter jejuni.

Every year in the United States, Campylobacter causes an estimated 1.3 million diarrheal illnesses. A recent multistate investigation revealed that 118 people in 18 states across the nation – including 29 employees of an unnamed national pet store chain based in Ohio – got the puppy-borne bug between early 2016 and early 2018.

And the not-so-cuddly infections were resistant to all the antibiotics commonly used to quell Campylobacter. Why? Turns out, of the 149 puppies investigated by health officials, 55% of them got the drugs prophylactically – an approach that may have fueled the resistance. Stung by the canine controversy, the Daisy Hill Puppy Farm has assured Charlie Brown that it never slipped metronidazole into Snoopy’s water bowl.

What the duck?

Turns out it’s flu shot season for our feathered friends, too. After the bird flu pandemics that began in 2013, Chinese health officials worked hard to vaccinate their chickens and quell the spread of the disease. However, the ducks have outsmarted them: Two new genetic variations of the H7N9 and H7N2 flu subtypes have been found in unvaccinated ducks.

China consumes about 3 billion ducks per year, so officials are working rapidly to eliminate the virus. At press time, there was no word on whether the virus had affected any beloved rubber duckies, but we advise you to use caution when approaching bath time.

Toke-a-Cola

Cannabis is the world’s favorite illicit drug. And Coca-Cola makes the world’s favorite cola. Now there’s news of potential nuptials uniting these two global giants. BNN Bloomberg reports that Coke is talking tie-up with Canada’s Aurora Cannabis in a union that could give birth to cannabis-infused “wellness beverages.”

The fizzy federation would feature products containing cannabidiol, or CBD. Unlike its wilder psychoactive sibling tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the more sober-minded CBD is a nonpsychoactive cannabis compound credited with antidepressant, anxiolytic, and anti-inflammatory powers.

And what of Coca-Cola’s mortal cola enemy, Pepsi? Will the Choice of a New Generation let the Real Thing Bogart all the possible market opportunities? Sure, you could soon have a CBD Coke and a smile. But smiles are free. Frito-Lay’s parent, PepsiCo, could offer consumers a doubly profitable, Jeff Spicoli–approved pairing: carbonated cannabinoids and Cheetos.

I vant to suck MY blood

It’s not Halloween quite yet, but get into the spirit with the recently published and aptly named “Vampire Study.” Performed in Zürich, a team of researchers from the division of gastroenterology at Triemli Hospital convinced participants to ingest their own blood, all in the name of science.

Some lucky vamps drank their blood, while others ingested it via nasogastric tube. This isn’t “Saw 17,” though; there was a method to this madness. Researchers were investigating whether the ingestion of blood (as in gastrointestinal bleeding) can result in an increase in fecal calprotectin. Safe to say, though, the ingestion of blood is rarely a good sign – unless your name happens to be Nosferatu.

And they call it Campylobacter love

As any fan of Charles Schulz’s “Peanuts” comic strip can tell you, happiness is a warm puppy. Know what else warm puppies are? Carriers of Campylobacter jejuni.

Every year in the United States, Campylobacter causes an estimated 1.3 million diarrheal illnesses. A recent multistate investigation revealed that 118 people in 18 states across the nation – including 29 employees of an unnamed national pet store chain based in Ohio – got the puppy-borne bug between early 2016 and early 2018.

And the not-so-cuddly infections were resistant to all the antibiotics commonly used to quell Campylobacter. Why? Turns out, of the 149 puppies investigated by health officials, 55% of them got the drugs prophylactically – an approach that may have fueled the resistance. Stung by the canine controversy, the Daisy Hill Puppy Farm has assured Charlie Brown that it never slipped metronidazole into Snoopy’s water bowl.

What the duck?

Turns out it’s flu shot season for our feathered friends, too. After the bird flu pandemics that began in 2013, Chinese health officials worked hard to vaccinate their chickens and quell the spread of the disease. However, the ducks have outsmarted them: Two new genetic variations of the H7N9 and H7N2 flu subtypes have been found in unvaccinated ducks.

China consumes about 3 billion ducks per year, so officials are working rapidly to eliminate the virus. At press time, there was no word on whether the virus had affected any beloved rubber duckies, but we advise you to use caution when approaching bath time.

Toke-a-Cola

Cannabis is the world’s favorite illicit drug. And Coca-Cola makes the world’s favorite cola. Now there’s news of potential nuptials uniting these two global giants. BNN Bloomberg reports that Coke is talking tie-up with Canada’s Aurora Cannabis in a union that could give birth to cannabis-infused “wellness beverages.”

The fizzy federation would feature products containing cannabidiol, or CBD. Unlike its wilder psychoactive sibling tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the more sober-minded CBD is a nonpsychoactive cannabis compound credited with antidepressant, anxiolytic, and anti-inflammatory powers.

And what of Coca-Cola’s mortal cola enemy, Pepsi? Will the Choice of a New Generation let the Real Thing Bogart all the possible market opportunities? Sure, you could soon have a CBD Coke and a smile. But smiles are free. Frito-Lay’s parent, PepsiCo, could offer consumers a doubly profitable, Jeff Spicoli–approved pairing: carbonated cannabinoids and Cheetos.

I vant to suck MY blood

It’s not Halloween quite yet, but get into the spirit with the recently published and aptly named “Vampire Study.” Performed in Zürich, a team of researchers from the division of gastroenterology at Triemli Hospital convinced participants to ingest their own blood, all in the name of science.

Some lucky vamps drank their blood, while others ingested it via nasogastric tube. This isn’t “Saw 17,” though; there was a method to this madness. Researchers were investigating whether the ingestion of blood (as in gastrointestinal bleeding) can result in an increase in fecal calprotectin. Safe to say, though, the ingestion of blood is rarely a good sign – unless your name happens to be Nosferatu.

And they call it Campylobacter love

As any fan of Charles Schulz’s “Peanuts” comic strip can tell you, happiness is a warm puppy. Know what else warm puppies are? Carriers of Campylobacter jejuni.

Every year in the United States, Campylobacter causes an estimated 1.3 million diarrheal illnesses. A recent multistate investigation revealed that 118 people in 18 states across the nation – including 29 employees of an unnamed national pet store chain based in Ohio – got the puppy-borne bug between early 2016 and early 2018.

And the not-so-cuddly infections were resistant to all the antibiotics commonly used to quell Campylobacter. Why? Turns out, of the 149 puppies investigated by health officials, 55% of them got the drugs prophylactically – an approach that may have fueled the resistance. Stung by the canine controversy, the Daisy Hill Puppy Farm has assured Charlie Brown that it never slipped metronidazole into Snoopy’s water bowl.

The oncologist’s dilemma

The textbook answer would have been straightforward: No additional chemotherapy. Focus on palliative care.

But Max (not his real name) was not a textbook case. He was a person, and he was terrified of dying.

When I met him in clinic, four lines of chemotherapy had not slowed the spread of his rare cancer that was already metastatic at the time of diagnosis. His skin was yellow. His hair had fallen out in clumps. His legs were swollen to the point that he couldn’t walk. He had trouble transferring from his wheelchair on his own.

All this was offset by the college hoodie he wore, a disarming display of his youth. I had to look at the chart to remind myself. He was only 19 years old.

“Will Dr. D give Max chemotherapy?” his mother asked me, referring to the attending oncologist who had been caring for her son since the beginning. “I think he needs it right away,” she said. She was holding back tears.

Protected by the fact that I was a visiting fellow in her clinic for the day, and I was just meeting Max, I deferred the decision to Dr. D.

Dr. D and I reviewed Max’s case outside the room, scrolling through his PET scans showing spread of cancer in his liver, lungs, and bones in only 2 short months. We recounted the multiple lines of chemotherapy and immunotherapy he had tried and that had failed him.

Palliative care? I offered. She agreed.

But as we went back in together, it was harder. Max’s mother began to cry as Dr. D tried to broach the option. To her, palliative care meant death. That was not something she could swallow. Her questions turned back only to the next chemotherapy we would be giving.

I learned that Max’s father worked in a hospital. He knew how serious it was. “He calls me every day, crying,” my attending later told me solemnly. Begging her to do something. Pleading for more chemotherapy.

After some painful back and forth in the room, we didn’t come to a resolution. Dr. D would call them later, she said.

It was a busy clinic day, and we saw the rest of her patients.

“What are we going to do about Max?” I asked at the end of the day. I was writing the note in his chart. We still didn’t have a plan.

More chemotherapy, from any technical and data-based standpoint, was not the right choice. We had no evidence it would improve survival. We did have evidence that it could worsen the quality of life when time was limited. If we gave him more chemotherapy, it would be beyond guidelines, beyond evidence. We would be off the grid.

I thought about the conversations I’d been privy to about giving toxic therapies near the end of life. While a handful felt productive, others were uncomfortably strained. The latter involved a tension that manifests when the goals of the patient and the oncologist are misaligned. The words may be slightly different each time, but the theme is the same.

The oncologist says: “More chemotherapy is not going to work.”

The patient says: “But we don’t know. It’s better than doing nothing. Can’t we try?”

This can be excruciatingly challenging because both sides are correct. Both sides are logical, and yet they are talking past each other.

From the point of view of the person desperate to survive, anything is worth a try. Without trying some form of treatment, there’s a zero percent chance of surviving. Low odds of something working are still better than zero percent odds.

But it’s not an issue of logic. For people like Max’s parents, the questions come from a place of helplessness. The cognitive dissonance sets in because our job is to help and we struggle when we feel we cannot. We want to say yes. I wish we had a treatment to slow Max’s cancer, too. I wish more chemotherapy would help him.

What I’ve learned from these conversations is the importance of defining terms. Specifically, what do we mean when we say a treatment will or will not “work”? What are we trying to achieve? To prolong life by weeks? By months or years? To make your pain go away? To help you feel stronger? To allow you to spend time doing what you love?

The relevant question is not: Will this treatment work? It is: What are your goals, and will this treatment help you achieve them?

Defining terms in that way can mean the difference of a conversation where two sides are talking past one another to one that comes to a mutual understanding – even if the ultimate conclusion is painful for everyone.

Yet sometimes, even for the most skilled communicators, there may be compromise. There may be an agreement to trial Nth-line chemotherapy, even without evidence that it will achieve a person’s goals. It will require nuanced informed consent from both sides. And it will come from a place of compassion.

This is what I thought about as I signed chemotherapy orders for Max that evening. I felt for him, for his parents, and for his oncologist.

Because even though I suspected the treatment wouldn’t work the way they all hoped it would, I also wasn’t the one fielding daily phone calls from a father, begging his oncologist to do something, anything at all, to save his son’s life.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

The textbook answer would have been straightforward: No additional chemotherapy. Focus on palliative care.

But Max (not his real name) was not a textbook case. He was a person, and he was terrified of dying.

When I met him in clinic, four lines of chemotherapy had not slowed the spread of his rare cancer that was already metastatic at the time of diagnosis. His skin was yellow. His hair had fallen out in clumps. His legs were swollen to the point that he couldn’t walk. He had trouble transferring from his wheelchair on his own.

All this was offset by the college hoodie he wore, a disarming display of his youth. I had to look at the chart to remind myself. He was only 19 years old.

“Will Dr. D give Max chemotherapy?” his mother asked me, referring to the attending oncologist who had been caring for her son since the beginning. “I think he needs it right away,” she said. She was holding back tears.

Protected by the fact that I was a visiting fellow in her clinic for the day, and I was just meeting Max, I deferred the decision to Dr. D.

Dr. D and I reviewed Max’s case outside the room, scrolling through his PET scans showing spread of cancer in his liver, lungs, and bones in only 2 short months. We recounted the multiple lines of chemotherapy and immunotherapy he had tried and that had failed him.

Palliative care? I offered. She agreed.

But as we went back in together, it was harder. Max’s mother began to cry as Dr. D tried to broach the option. To her, palliative care meant death. That was not something she could swallow. Her questions turned back only to the next chemotherapy we would be giving.

I learned that Max’s father worked in a hospital. He knew how serious it was. “He calls me every day, crying,” my attending later told me solemnly. Begging her to do something. Pleading for more chemotherapy.

After some painful back and forth in the room, we didn’t come to a resolution. Dr. D would call them later, she said.

It was a busy clinic day, and we saw the rest of her patients.

“What are we going to do about Max?” I asked at the end of the day. I was writing the note in his chart. We still didn’t have a plan.

More chemotherapy, from any technical and data-based standpoint, was not the right choice. We had no evidence it would improve survival. We did have evidence that it could worsen the quality of life when time was limited. If we gave him more chemotherapy, it would be beyond guidelines, beyond evidence. We would be off the grid.

I thought about the conversations I’d been privy to about giving toxic therapies near the end of life. While a handful felt productive, others were uncomfortably strained. The latter involved a tension that manifests when the goals of the patient and the oncologist are misaligned. The words may be slightly different each time, but the theme is the same.

The oncologist says: “More chemotherapy is not going to work.”

The patient says: “But we don’t know. It’s better than doing nothing. Can’t we try?”

This can be excruciatingly challenging because both sides are correct. Both sides are logical, and yet they are talking past each other.

From the point of view of the person desperate to survive, anything is worth a try. Without trying some form of treatment, there’s a zero percent chance of surviving. Low odds of something working are still better than zero percent odds.

But it’s not an issue of logic. For people like Max’s parents, the questions come from a place of helplessness. The cognitive dissonance sets in because our job is to help and we struggle when we feel we cannot. We want to say yes. I wish we had a treatment to slow Max’s cancer, too. I wish more chemotherapy would help him.

What I’ve learned from these conversations is the importance of defining terms. Specifically, what do we mean when we say a treatment will or will not “work”? What are we trying to achieve? To prolong life by weeks? By months or years? To make your pain go away? To help you feel stronger? To allow you to spend time doing what you love?

The relevant question is not: Will this treatment work? It is: What are your goals, and will this treatment help you achieve them?

Defining terms in that way can mean the difference of a conversation where two sides are talking past one another to one that comes to a mutual understanding – even if the ultimate conclusion is painful for everyone.

Yet sometimes, even for the most skilled communicators, there may be compromise. There may be an agreement to trial Nth-line chemotherapy, even without evidence that it will achieve a person’s goals. It will require nuanced informed consent from both sides. And it will come from a place of compassion.

This is what I thought about as I signed chemotherapy orders for Max that evening. I felt for him, for his parents, and for his oncologist.

Because even though I suspected the treatment wouldn’t work the way they all hoped it would, I also wasn’t the one fielding daily phone calls from a father, begging his oncologist to do something, anything at all, to save his son’s life.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

The textbook answer would have been straightforward: No additional chemotherapy. Focus on palliative care.

But Max (not his real name) was not a textbook case. He was a person, and he was terrified of dying.

When I met him in clinic, four lines of chemotherapy had not slowed the spread of his rare cancer that was already metastatic at the time of diagnosis. His skin was yellow. His hair had fallen out in clumps. His legs were swollen to the point that he couldn’t walk. He had trouble transferring from his wheelchair on his own.

All this was offset by the college hoodie he wore, a disarming display of his youth. I had to look at the chart to remind myself. He was only 19 years old.

“Will Dr. D give Max chemotherapy?” his mother asked me, referring to the attending oncologist who had been caring for her son since the beginning. “I think he needs it right away,” she said. She was holding back tears.

Protected by the fact that I was a visiting fellow in her clinic for the day, and I was just meeting Max, I deferred the decision to Dr. D.

Dr. D and I reviewed Max’s case outside the room, scrolling through his PET scans showing spread of cancer in his liver, lungs, and bones in only 2 short months. We recounted the multiple lines of chemotherapy and immunotherapy he had tried and that had failed him.

Palliative care? I offered. She agreed.

But as we went back in together, it was harder. Max’s mother began to cry as Dr. D tried to broach the option. To her, palliative care meant death. That was not something she could swallow. Her questions turned back only to the next chemotherapy we would be giving.

I learned that Max’s father worked in a hospital. He knew how serious it was. “He calls me every day, crying,” my attending later told me solemnly. Begging her to do something. Pleading for more chemotherapy.

After some painful back and forth in the room, we didn’t come to a resolution. Dr. D would call them later, she said.

It was a busy clinic day, and we saw the rest of her patients.

“What are we going to do about Max?” I asked at the end of the day. I was writing the note in his chart. We still didn’t have a plan.

More chemotherapy, from any technical and data-based standpoint, was not the right choice. We had no evidence it would improve survival. We did have evidence that it could worsen the quality of life when time was limited. If we gave him more chemotherapy, it would be beyond guidelines, beyond evidence. We would be off the grid.

I thought about the conversations I’d been privy to about giving toxic therapies near the end of life. While a handful felt productive, others were uncomfortably strained. The latter involved a tension that manifests when the goals of the patient and the oncologist are misaligned. The words may be slightly different each time, but the theme is the same.

The oncologist says: “More chemotherapy is not going to work.”

The patient says: “But we don’t know. It’s better than doing nothing. Can’t we try?”

This can be excruciatingly challenging because both sides are correct. Both sides are logical, and yet they are talking past each other.

From the point of view of the person desperate to survive, anything is worth a try. Without trying some form of treatment, there’s a zero percent chance of surviving. Low odds of something working are still better than zero percent odds.

But it’s not an issue of logic. For people like Max’s parents, the questions come from a place of helplessness. The cognitive dissonance sets in because our job is to help and we struggle when we feel we cannot. We want to say yes. I wish we had a treatment to slow Max’s cancer, too. I wish more chemotherapy would help him.

What I’ve learned from these conversations is the importance of defining terms. Specifically, what do we mean when we say a treatment will or will not “work”? What are we trying to achieve? To prolong life by weeks? By months or years? To make your pain go away? To help you feel stronger? To allow you to spend time doing what you love?

The relevant question is not: Will this treatment work? It is: What are your goals, and will this treatment help you achieve them?

Defining terms in that way can mean the difference of a conversation where two sides are talking past one another to one that comes to a mutual understanding – even if the ultimate conclusion is painful for everyone.

Yet sometimes, even for the most skilled communicators, there may be compromise. There may be an agreement to trial Nth-line chemotherapy, even without evidence that it will achieve a person’s goals. It will require nuanced informed consent from both sides. And it will come from a place of compassion.

This is what I thought about as I signed chemotherapy orders for Max that evening. I felt for him, for his parents, and for his oncologist.

Because even though I suspected the treatment wouldn’t work the way they all hoped it would, I also wasn’t the one fielding daily phone calls from a father, begging his oncologist to do something, anything at all, to save his son’s life.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

TV and mental health story lines; when doctors don’t listen – to women

Turn on the television, and chances are good that popular dramas (especially hospital-oriented shows) will be showing an episode revolving around a mental health issue.

, in time for a commercial. Real life is messier.

“Unfortunately mental health story lines are much more likely to be fear-mongering and wildly wrong. As a psychiatrist, this both piques my interest and upends my work-life balance,” Dr. Gold writes. “Whether I’m watching everyone’s favorite medical drama or ‘reality TV,’ it’s impossible not to switch into physician mode, angry on behalf of all of my patients and the many viewers who are being misled.”

Do physicians hear women?

“Rebecca continues to be paranoid.”

That was a note written by someone involved in the medical care of a 30-something woman diagnosed with stage IIB cervical cancer, according to an article in New York magazine.

“There’s a whiff of old ‘female hysteria’ to [the note], with more than a hint of dismissal,” writes the patient’s sister, Kate Beaton. “Becky was scared, and perhaps that was the main takeaway that day. But she was also right.”

The article tells the story of a vibrant woman who, according to her sister, asked her doctors lots of questions, wrote everything down, and faced years of being dismissed when she explained her symptoms. Becky’s sister says she is telling her sister’s story in an effort to make a difference in the lives of other patients.

“[Becky] did not want anyone to go through what she went through, ever again,” Ms. Beaton writes.

Letting children roam free

Children of the 1950s and 1960s can remember tearing out the door after dinner with the parental order to be home before dark. Where we went and what we did was known only to us. Our parents trusted we knew how to look out after ourselves.

In that tradition, as explained by National Public Radio, some parents are actively turning away from the to-the-second scheduling of their children’s lives and Teflon coating them against the perceived danger of everyday life. Instead, they are letting their children be independent. It can be a powerful life benefit for a child. But it can come at a cost to parents. Parents in several states have been arrested for actions that include letting their children walk to school unattended.

“This very pessimistic, fearful way of looking at childhood isn’t based in reality,” says Leonore Skenazy in a story on NPR. “It is something that we have been taught.” Ms. Skenazy is founder of Free Range Kids, a group that promotes childhood independence.

Boundaries and remote work

More and more Americans are working from home, according to a 2017 Gallup survey. The survey says that 43% of people worked remotely for part of the time in 2016, compared with 39% in 2012.

But for parents who work remotely, separating their business and family lives is especially challenging, Marie Elizabeth Oliver writes in an article published in The Washington Post.

“Being a parent is isolating, but being a parent and working from home is really isolating,” author Karen Alpert says. “Especially as a mom, there’s so much pressure to do your job as fast and efficiently as possible.”

Experts advise setting boundaries by taking steps such as setting timers and checking in every hour, for example. Or using clothes to make the mental shifts between being on the clock, so to speak, and being in leisure mode.

“It’s not that you have to dress up,” author David Heinemeier Hansson says in the article, describing one of his employees who came up with a system that enabled him to set these boundaries using clothes. “It’s just that he knew, ‘I have my home slippers on right now, so I’m not responding to this email.’ “

Neuroscience as a remedy to heartbreak

The end of a romance can be both frustrating and embarrassing. A person may wallow in the emotional muck for a long time.

Such was the case for Dessa, a well-known rapper, singer, and writer from Minneapolis, who carried the emotional baggage of an ex-boyfriend.

“You’re not only suffering,” she comments in an interview on NPR. “You’re just sort of ridiculous. Discipline and dedication are my strong suits – it really bothered me that, no matter how much effort I tried to expend in trying to solve this problem, I was stuck.”

The stalemate ended when she viewed a TED Talk by Helen Fisher, PhD, a biological anthropologist and visiting research associate at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. Dr. Fisher used functional MRI to examine some people in the throes of lost love. The examinations revealed revved-up activity of certain parts of their brains.

This prompted the idea that techniques of neurofeedback could be used to wipe the pangs of love from the brain circuitry. It seems to have worked for Dessa, although a placebo effect cannot be ruled out.

“Before [the feedback], I felt that I was really under the thumb of a fixation and a compulsion,” she says. “And now it feels like those feelings have been scaled down.”

Turn on the television, and chances are good that popular dramas (especially hospital-oriented shows) will be showing an episode revolving around a mental health issue.

, in time for a commercial. Real life is messier.

“Unfortunately mental health story lines are much more likely to be fear-mongering and wildly wrong. As a psychiatrist, this both piques my interest and upends my work-life balance,” Dr. Gold writes. “Whether I’m watching everyone’s favorite medical drama or ‘reality TV,’ it’s impossible not to switch into physician mode, angry on behalf of all of my patients and the many viewers who are being misled.”

Do physicians hear women?

“Rebecca continues to be paranoid.”

That was a note written by someone involved in the medical care of a 30-something woman diagnosed with stage IIB cervical cancer, according to an article in New York magazine.

“There’s a whiff of old ‘female hysteria’ to [the note], with more than a hint of dismissal,” writes the patient’s sister, Kate Beaton. “Becky was scared, and perhaps that was the main takeaway that day. But she was also right.”

The article tells the story of a vibrant woman who, according to her sister, asked her doctors lots of questions, wrote everything down, and faced years of being dismissed when she explained her symptoms. Becky’s sister says she is telling her sister’s story in an effort to make a difference in the lives of other patients.

“[Becky] did not want anyone to go through what she went through, ever again,” Ms. Beaton writes.

Letting children roam free

Children of the 1950s and 1960s can remember tearing out the door after dinner with the parental order to be home before dark. Where we went and what we did was known only to us. Our parents trusted we knew how to look out after ourselves.

In that tradition, as explained by National Public Radio, some parents are actively turning away from the to-the-second scheduling of their children’s lives and Teflon coating them against the perceived danger of everyday life. Instead, they are letting their children be independent. It can be a powerful life benefit for a child. But it can come at a cost to parents. Parents in several states have been arrested for actions that include letting their children walk to school unattended.

“This very pessimistic, fearful way of looking at childhood isn’t based in reality,” says Leonore Skenazy in a story on NPR. “It is something that we have been taught.” Ms. Skenazy is founder of Free Range Kids, a group that promotes childhood independence.

Boundaries and remote work

More and more Americans are working from home, according to a 2017 Gallup survey. The survey says that 43% of people worked remotely for part of the time in 2016, compared with 39% in 2012.

But for parents who work remotely, separating their business and family lives is especially challenging, Marie Elizabeth Oliver writes in an article published in The Washington Post.

“Being a parent is isolating, but being a parent and working from home is really isolating,” author Karen Alpert says. “Especially as a mom, there’s so much pressure to do your job as fast and efficiently as possible.”

Experts advise setting boundaries by taking steps such as setting timers and checking in every hour, for example. Or using clothes to make the mental shifts between being on the clock, so to speak, and being in leisure mode.

“It’s not that you have to dress up,” author David Heinemeier Hansson says in the article, describing one of his employees who came up with a system that enabled him to set these boundaries using clothes. “It’s just that he knew, ‘I have my home slippers on right now, so I’m not responding to this email.’ “

Neuroscience as a remedy to heartbreak

The end of a romance can be both frustrating and embarrassing. A person may wallow in the emotional muck for a long time.

Such was the case for Dessa, a well-known rapper, singer, and writer from Minneapolis, who carried the emotional baggage of an ex-boyfriend.

“You’re not only suffering,” she comments in an interview on NPR. “You’re just sort of ridiculous. Discipline and dedication are my strong suits – it really bothered me that, no matter how much effort I tried to expend in trying to solve this problem, I was stuck.”

The stalemate ended when she viewed a TED Talk by Helen Fisher, PhD, a biological anthropologist and visiting research associate at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. Dr. Fisher used functional MRI to examine some people in the throes of lost love. The examinations revealed revved-up activity of certain parts of their brains.

This prompted the idea that techniques of neurofeedback could be used to wipe the pangs of love from the brain circuitry. It seems to have worked for Dessa, although a placebo effect cannot be ruled out.

“Before [the feedback], I felt that I was really under the thumb of a fixation and a compulsion,” she says. “And now it feels like those feelings have been scaled down.”

Turn on the television, and chances are good that popular dramas (especially hospital-oriented shows) will be showing an episode revolving around a mental health issue.

, in time for a commercial. Real life is messier.

“Unfortunately mental health story lines are much more likely to be fear-mongering and wildly wrong. As a psychiatrist, this both piques my interest and upends my work-life balance,” Dr. Gold writes. “Whether I’m watching everyone’s favorite medical drama or ‘reality TV,’ it’s impossible not to switch into physician mode, angry on behalf of all of my patients and the many viewers who are being misled.”

Do physicians hear women?

“Rebecca continues to be paranoid.”

That was a note written by someone involved in the medical care of a 30-something woman diagnosed with stage IIB cervical cancer, according to an article in New York magazine.

“There’s a whiff of old ‘female hysteria’ to [the note], with more than a hint of dismissal,” writes the patient’s sister, Kate Beaton. “Becky was scared, and perhaps that was the main takeaway that day. But she was also right.”

The article tells the story of a vibrant woman who, according to her sister, asked her doctors lots of questions, wrote everything down, and faced years of being dismissed when she explained her symptoms. Becky’s sister says she is telling her sister’s story in an effort to make a difference in the lives of other patients.

“[Becky] did not want anyone to go through what she went through, ever again,” Ms. Beaton writes.

Letting children roam free

Children of the 1950s and 1960s can remember tearing out the door after dinner with the parental order to be home before dark. Where we went and what we did was known only to us. Our parents trusted we knew how to look out after ourselves.

In that tradition, as explained by National Public Radio, some parents are actively turning away from the to-the-second scheduling of their children’s lives and Teflon coating them against the perceived danger of everyday life. Instead, they are letting their children be independent. It can be a powerful life benefit for a child. But it can come at a cost to parents. Parents in several states have been arrested for actions that include letting their children walk to school unattended.

“This very pessimistic, fearful way of looking at childhood isn’t based in reality,” says Leonore Skenazy in a story on NPR. “It is something that we have been taught.” Ms. Skenazy is founder of Free Range Kids, a group that promotes childhood independence.

Boundaries and remote work

More and more Americans are working from home, according to a 2017 Gallup survey. The survey says that 43% of people worked remotely for part of the time in 2016, compared with 39% in 2012.

But for parents who work remotely, separating their business and family lives is especially challenging, Marie Elizabeth Oliver writes in an article published in The Washington Post.

“Being a parent is isolating, but being a parent and working from home is really isolating,” author Karen Alpert says. “Especially as a mom, there’s so much pressure to do your job as fast and efficiently as possible.”

Experts advise setting boundaries by taking steps such as setting timers and checking in every hour, for example. Or using clothes to make the mental shifts between being on the clock, so to speak, and being in leisure mode.

“It’s not that you have to dress up,” author David Heinemeier Hansson says in the article, describing one of his employees who came up with a system that enabled him to set these boundaries using clothes. “It’s just that he knew, ‘I have my home slippers on right now, so I’m not responding to this email.’ “

Neuroscience as a remedy to heartbreak

The end of a romance can be both frustrating and embarrassing. A person may wallow in the emotional muck for a long time.

Such was the case for Dessa, a well-known rapper, singer, and writer from Minneapolis, who carried the emotional baggage of an ex-boyfriend.

“You’re not only suffering,” she comments in an interview on NPR. “You’re just sort of ridiculous. Discipline and dedication are my strong suits – it really bothered me that, no matter how much effort I tried to expend in trying to solve this problem, I was stuck.”

The stalemate ended when she viewed a TED Talk by Helen Fisher, PhD, a biological anthropologist and visiting research associate at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. Dr. Fisher used functional MRI to examine some people in the throes of lost love. The examinations revealed revved-up activity of certain parts of their brains.

This prompted the idea that techniques of neurofeedback could be used to wipe the pangs of love from the brain circuitry. It seems to have worked for Dessa, although a placebo effect cannot be ruled out.

“Before [the feedback], I felt that I was really under the thumb of a fixation and a compulsion,” she says. “And now it feels like those feelings have been scaled down.”

Slowing down

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Burnout may jeopardize patient care

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Burnout among physicians was associated with lower quality of care because of unprofessionalism, reduced patient satisfaction, and an increased risk of patient safety issues.

Major finding: Physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85).

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 42,473 physicians from 47 different studies.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the United Kingdom National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

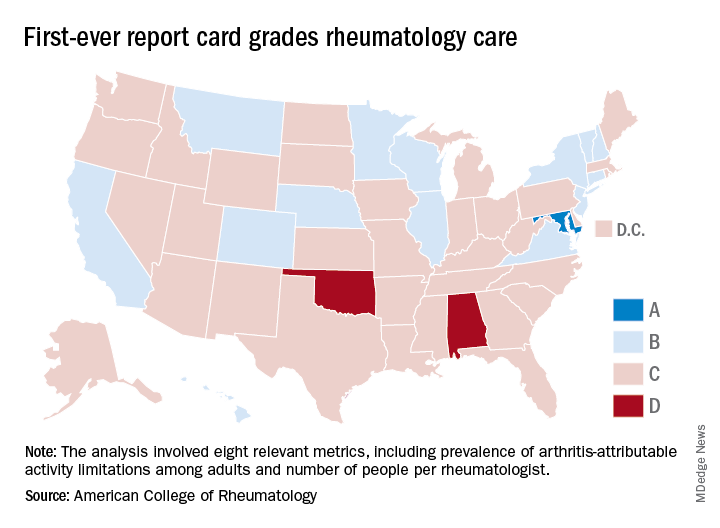

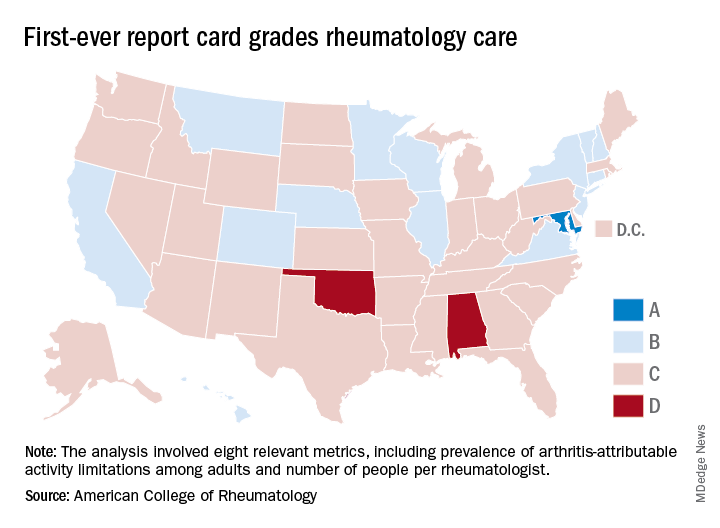

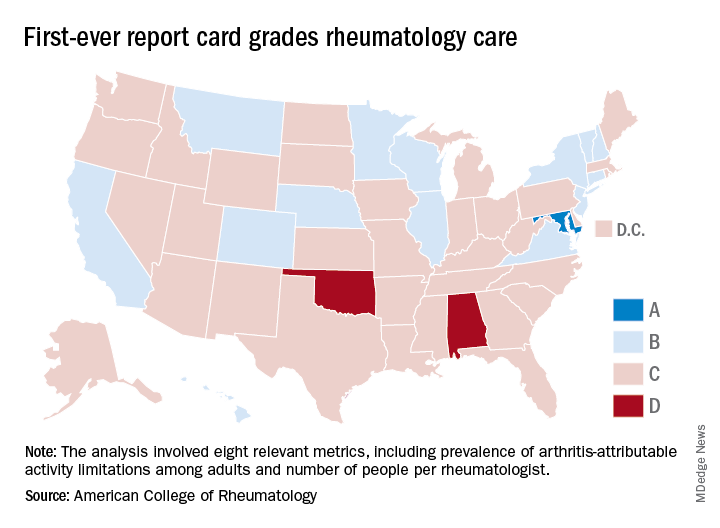

Maryland gets an A on ‘Rheumatic Disease Report Card’

Maryland is alone at the top of the rheumatology care class, but the number of failing states is even smaller, according to the American College of Rheumatology.

Maryland was the only state to earn an A on the “Rheumatic Disease Report Card,” and while no state failed, two – Alabama and Oklahoma – did receive Ds. Among the 47 other states and the District of Columbia, there were 14 Bs and 34 Cs.

Maryland posted strong scores in all three of the report card’s broad categories of care: 38.25 out of 50 points (third among all states) for access, 35 out of 50 (tied for first with New York) for affordability, and 40 out of 50 (tied for ninth) for activity/lifestyle. Arkansas had the highest score (42.25) for access and Nebraska got 50 out of 50 for activity/lifestyle. Inferiority, however, turned out to be a lot more widespread, as eight states were tied for the low of 10 points in the access category, 26 states got a 0 for affordability, and six states earned 15 points for activity/lifestyle, the ACR said.

Arkansas’s high marks for access were based primarily on “state lawmakers’ recent efforts to address [pharmacy benefit manager] transparency by enacting legislation that should serve as a model for future action in other states looking to address this issue,” ACR officials said in a statement. Nebraska did well in both of the measures used in the activity/lifestyle category – age-adjusted prevalence of arthritis attributable activity limitations among adults and percent of adults who are physically inactive; it also did well because it is home to at least one YMCA-sponsored and one National Recreation and Park Association–sponsored arthritis intervention program funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

as demand increases and supply decreases. The college’s projections show that almost 6,800 rheumatologists will be needed by 2020 but less than 4,500 will be available, and by 2030 the demand will rise to need for almost 8,200 rheumatologists, while supply is expected to drop below 3,500, according to the report.

“We are at a critical juncture in rheumatology care. The rheumatology workforce is not growing fast enough to keep up with demand and too many of our patients struggle to access and afford the breakthrough therapies they need to manage pain and avoid long-term disability,” ACR President David Daikh, MD, PhD wrote in the report.

Maryland is alone at the top of the rheumatology care class, but the number of failing states is even smaller, according to the American College of Rheumatology.

Maryland was the only state to earn an A on the “Rheumatic Disease Report Card,” and while no state failed, two – Alabama and Oklahoma – did receive Ds. Among the 47 other states and the District of Columbia, there were 14 Bs and 34 Cs.

Maryland posted strong scores in all three of the report card’s broad categories of care: 38.25 out of 50 points (third among all states) for access, 35 out of 50 (tied for first with New York) for affordability, and 40 out of 50 (tied for ninth) for activity/lifestyle. Arkansas had the highest score (42.25) for access and Nebraska got 50 out of 50 for activity/lifestyle. Inferiority, however, turned out to be a lot more widespread, as eight states were tied for the low of 10 points in the access category, 26 states got a 0 for affordability, and six states earned 15 points for activity/lifestyle, the ACR said.

Arkansas’s high marks for access were based primarily on “state lawmakers’ recent efforts to address [pharmacy benefit manager] transparency by enacting legislation that should serve as a model for future action in other states looking to address this issue,” ACR officials said in a statement. Nebraska did well in both of the measures used in the activity/lifestyle category – age-adjusted prevalence of arthritis attributable activity limitations among adults and percent of adults who are physically inactive; it also did well because it is home to at least one YMCA-sponsored and one National Recreation and Park Association–sponsored arthritis intervention program funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

as demand increases and supply decreases. The college’s projections show that almost 6,800 rheumatologists will be needed by 2020 but less than 4,500 will be available, and by 2030 the demand will rise to need for almost 8,200 rheumatologists, while supply is expected to drop below 3,500, according to the report.

“We are at a critical juncture in rheumatology care. The rheumatology workforce is not growing fast enough to keep up with demand and too many of our patients struggle to access and afford the breakthrough therapies they need to manage pain and avoid long-term disability,” ACR President David Daikh, MD, PhD wrote in the report.

Maryland is alone at the top of the rheumatology care class, but the number of failing states is even smaller, according to the American College of Rheumatology.

Maryland was the only state to earn an A on the “Rheumatic Disease Report Card,” and while no state failed, two – Alabama and Oklahoma – did receive Ds. Among the 47 other states and the District of Columbia, there were 14 Bs and 34 Cs.

Maryland posted strong scores in all three of the report card’s broad categories of care: 38.25 out of 50 points (third among all states) for access, 35 out of 50 (tied for first with New York) for affordability, and 40 out of 50 (tied for ninth) for activity/lifestyle. Arkansas had the highest score (42.25) for access and Nebraska got 50 out of 50 for activity/lifestyle. Inferiority, however, turned out to be a lot more widespread, as eight states were tied for the low of 10 points in the access category, 26 states got a 0 for affordability, and six states earned 15 points for activity/lifestyle, the ACR said.

Arkansas’s high marks for access were based primarily on “state lawmakers’ recent efforts to address [pharmacy benefit manager] transparency by enacting legislation that should serve as a model for future action in other states looking to address this issue,” ACR officials said in a statement. Nebraska did well in both of the measures used in the activity/lifestyle category – age-adjusted prevalence of arthritis attributable activity limitations among adults and percent of adults who are physically inactive; it also did well because it is home to at least one YMCA-sponsored and one National Recreation and Park Association–sponsored arthritis intervention program funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

as demand increases and supply decreases. The college’s projections show that almost 6,800 rheumatologists will be needed by 2020 but less than 4,500 will be available, and by 2030 the demand will rise to need for almost 8,200 rheumatologists, while supply is expected to drop below 3,500, according to the report.

“We are at a critical juncture in rheumatology care. The rheumatology workforce is not growing fast enough to keep up with demand and too many of our patients struggle to access and afford the breakthrough therapies they need to manage pain and avoid long-term disability,” ACR President David Daikh, MD, PhD wrote in the report.

AAP cautions against marijuana use during pregnancy, breastfeeding

, according to a recent clinical report published in the journal Pediatrics.

“The fact that marijuana is legal in many states may give the impression the drug is harmless during pregnancy, especially with stories swirling on social media about using it for nausea with morning sickness,” Sheryl A. Ryan, MD, FAAP, Chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Substance Use and Prevention, stated in a press release. “But in fact, this is still a big question. We do not have good safety data on prenatal exposure to marijuana. Based on the limited data that do exist, as pediatricians, we believe there is cause to be concerned about how the drug will impact the long-term development of children.”

The rate of marijuana use is increasing among pregnant women 18 years to 44 years old is increasing, the committee said, with 3.84% of women in 2014 within that age range using marijuana within the past month compared with 2.37% in 2002. Among women who were between 18 years and 25 years old, the rate of marijuana use within the past month was 7.47% in 2014.

The committee also noted research has shown cannabidiol exposure in the short term may impact placental permeability to “pharmacologic agents and recreational substances, potentially placing the fetus at risk from these agents or drugs.” A more well-known substance in marijuana, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) crosses the placental barrier and can appear in fetal blood. Studies have reported any level of marijuana use among pregnant women put the mothers at risk of anemia, while their newborns had an increased risk of low-birth weight and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) use. Further research has shown impaired mental development, executive function deficits, increased impulsivity and hyperactivity, behavioral problems, depressive symptoms, and greater rates of substance abuse among children exposed to marijuana.

“Many of these effects may not show up right away, but they can impact how well a child can maneuver in the world,” Dr. Ryan stated in the release. “Children’s and teens’ cognitive ability to manage their time and school work might be harmed down the line from marijuana use during their mother’s pregnancy.”